Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

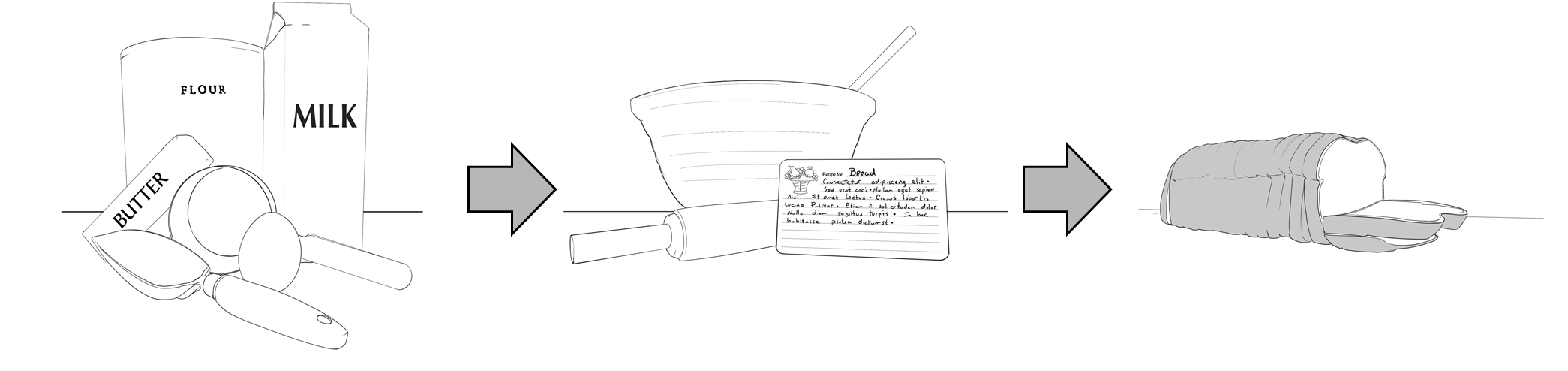

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

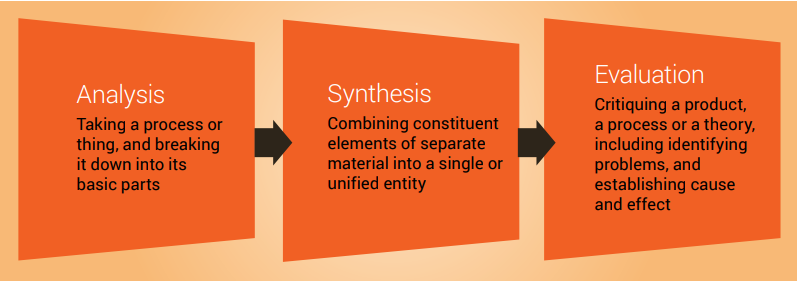

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

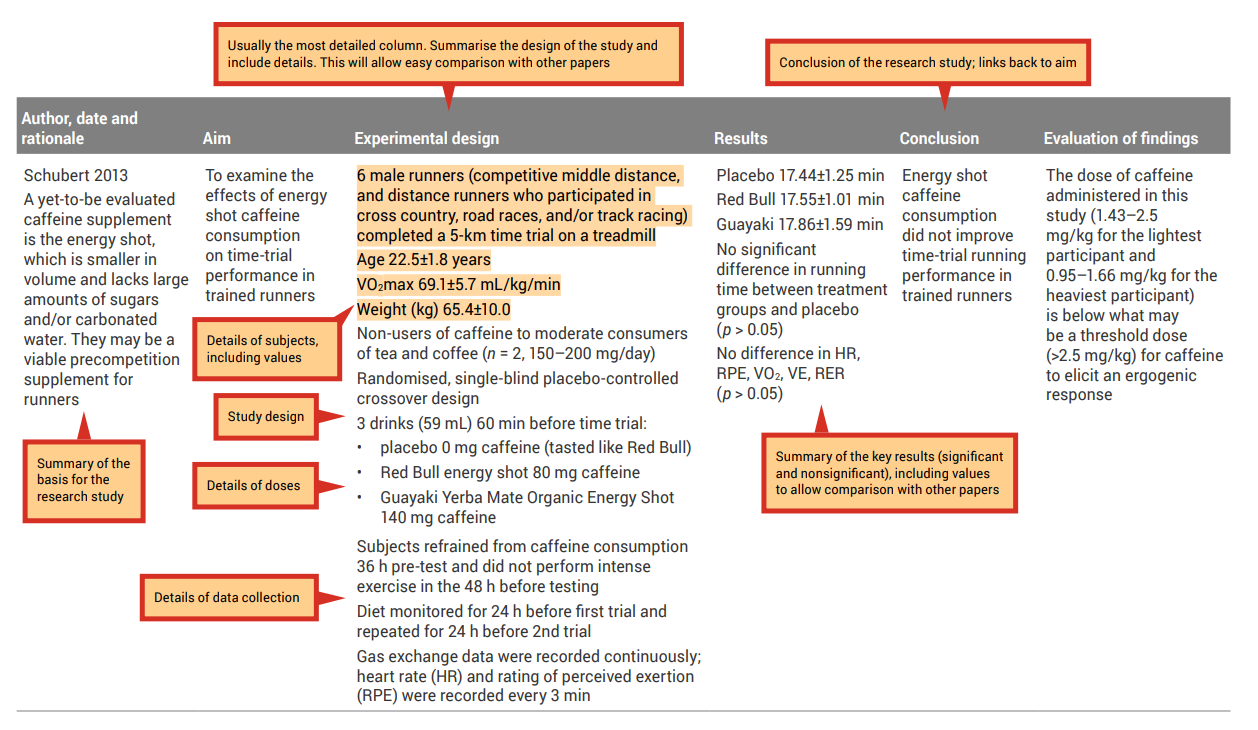

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

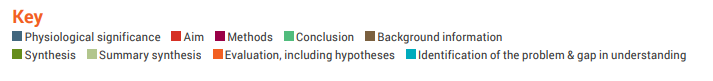

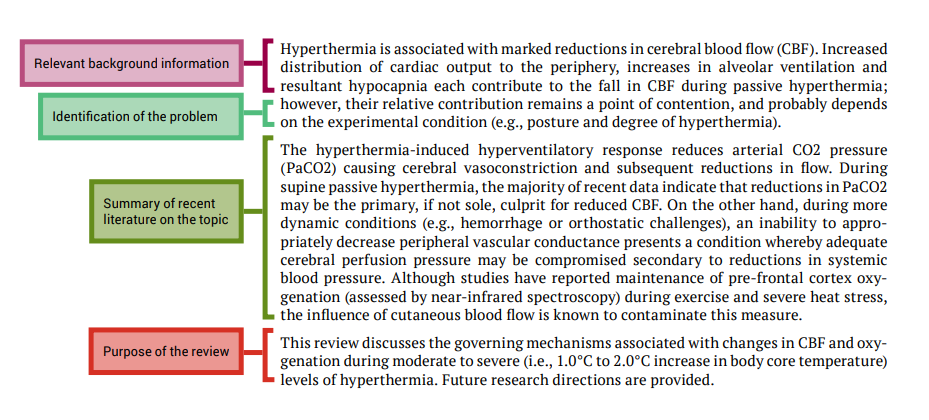

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

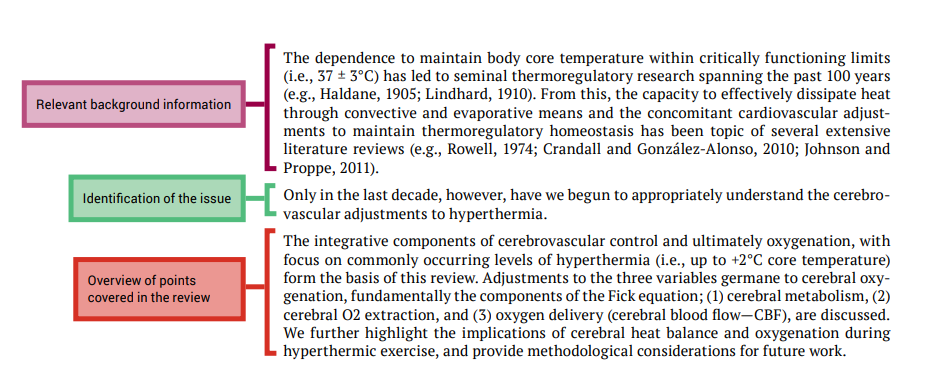

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved March 20, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Literature review outline [Write a literature review with these structures]

Welcome to our comprehensive blog on crafting a perfect literature review for your research paper or dissertation.

The ability to write a literature review with a concise and structured outline is pivotal in academic writing.

You’ll get an overview of how to structure your review effectively, address your research question, and demonstrate your understanding of existing knowledge.

We’ll delve into different approaches to literature reviews, discuss the importance of a theoretical approach, and show you how to handle turning points in your narrative.

You’ll learn how to integrate key concepts from your research field and weave them into your paragraphs to highlight their importance.

Moreover, we’ll guide you through the nuances of APA citation style and how to compile a comprehensive bibliography. Lastly, we’ll walk you through the proofreading process to ensure your work is error-free.

As a bonus, this blog will provide useful tips for both seasoned researchers and first-time writers to produce a literature review that’s clear, informative, and engaging. Enjoy the writing process with us!

Structure of a Literature Review – Outline

When you write a literature review outline, you are laying the foundations of great work. Many people rush this part and struggle later on. Take your time and slowly draft the outline for a literature review.

The structure of a literature review consists of five main components:

- Introduction: Provide a brief overview of the chapter, along with the topic and research aims to set the context for the reader.

- Foundation of Theory or Theoretical Framework: Present and discuss the key theories, concepts, and models related to your research topic. Explain how they apply to your study and their significance.

- Empirical Research: Review and analyze relevant empirical related to your research question. Highlight their findings, methodologies, and any limitations they possess.

- Research Gap: Identify any gaps, inconsistencies, or ambiguities in the existing literature. This will help establish the need for your research and justify its relevance.

- Conclusion: Summarize the main findings from the literature review, emphasizing the importance of your research question and the identified research gap. Suggest potential avenues for future research in the field.

Sentence starters for each section of your literature review:

Literature review examples and types.

Based on the typology of literature reviews from Paré et al. (2015), the following list outlines various types of literature reviews and examples of when you’d use each type:

1. Conceptual Review: Analyzes and synthesizes the theoretical and conceptual aspects of a topic. It focuses on understanding key concepts, models, and theories.

Example use: When aiming to clarify the conceptual foundations and explore existing theories in a field, such as investigating the dimensions of job satisfaction.

2. Methodological Review: Evaluates and synthesizes the research approaches, methods, and techniques used in existing literature. It aims to identify methodological strengths and weaknesses in a research area.

Example use: When assessing data collection methods for researching user experiences with a new software application.

3. Descriptive Review: Provides a broad overview of studies in a research area. It aims to describe the existing literature on a topic and document its evolution over time.

Example use: When investigating the history of research on employee motivation and documenting its progress over the years.

4. Integrative Review: Combines and synthesizes findings from different studies to produce a comprehensive understanding of a research topic. It may identify trends, patterns, or common themes among various studies.

Example use: When exploring the links between work-life balance and job satisfaction, aggregating evidence from multiple studies to develop a comprehensive understanding.

5. Theory-driven Review: Examines a research topic through the lens of a specific theoretical framework. It focuses on understanding how the chosen theory explains or predicts phenomena in the literature.

Example use: When studying the impact of leadership styles on team performance, specifically using the transformational leadership theory as a basis for the analysis.

6. Evidence-driven Review: Aims to determine the effectiveness of interventions or practices based on the available research evidence. It can inform the decision-making process in practice or policy by providing evidence-based recommendations.

Example use: When assessing the effectiveness of telemedicine interventions for managing chronic disease outcomes, providing recommendations for healthcare providers and policymakers.

By understanding these types of literature reviews and their appropriate usage, researchers can choose the most suitable approach for their research question and contribute valuable insights to their field.

How to Write a Good Literature Review

To write a good literature review, follow these six steps to help you create relevant and actionable content for a young researcher.

1. Define the review’s purpose: Before starting, establish a clear understanding of your research question or hypothesis. This helps focus the review and prevents unnecessary information from being included.

2. Set inclusion and exclusion criteria: Use predefined criteria for including or excluding sources in your review. Establish these criteria based on aspects such as publication date, language, type of study, and subject relevance. This ensures your review remains focused and meets your objectives.

3. Search for relevant literature: Conduct a comprehensive search for literature relevant to your research question. Use databases, online catalogs, and search engines that focus on academic literature, such as Google Scholar, Scopus, or Web of Science. Consider using multiple search terms and synonyms to cover all related topics.

4. Organize and analyze information: Develop a system for organizing and analyzing the information you find. You can use spreadsheets, note-taking applications, or reference management tools like Mendeley, Zotero, or EndNote. Categorize your sources based on themes, author’s conclusions, methodology, or other relevant criteria.

5. Write a critique of the literature: Evaluate and synthesize the information from your sources. Discuss their strengths, weaknesses, and gaps in knowledge or understanding. Point out any inconsistencies in the findings and explain any varying theories or viewpoints. Provide a balanced critique that highlights the most significant contributions, trends, or patterns.

6. Structure the review: Organize your literature review into sections that present the main themes or findings. Start with an introduction that outlines your research question, the scope of the review, and any limitations you may have encountered. Write clear, concise, and coherent summaries of your literature for each section, and end with a conclusion that synthesizes the main findings, suggests areas for further research, and reinforces your research question or hypothesis.

Incorporating these steps will assist you in crafting a well-structured, focused, and informative literature review for your research project.

Here are some examples of each step in the process.

Top Tips on How to Write Your Literature Review

Here are the top tips on how to write your literature review, based on the Grad Coach TV video and advice from trusted coach Amy:

1. Develop a rough outline or framework before you start writing your literature review. This helps you avoid creating a jumbled mess and allows you to organize your thoughts coherently and effectively.

2. Use previous literature reviews as a guide to understand the norms and expectations in your field. Look for recently published literature reviews in academic journals or online databases, such as Google Scholar, EBSCO, or ProQuest.

3. Write first and edit later. Avoid perfectionism and don’t be afraid to create messy drafts. This helps you overcome writer’s block and ensures progress in your work.

4. Insert citations as you write to avoid losing track of references. Make sure to follow the appropriate formatting style (e.g. APA or MLA) and use reference management tools like Mendeley to easily keep track of your sources.

5. Organize your literature review logically, whether it’s chronologically, thematically, or methodologically. Identify gaps in the literature and explain how your study addresses them. Keep in mind that the structure isn’t set in stone and can change as you read and write.

Remember that writing your literature review is an iterative process, so give yourself room to improve and make changes as needed. Keep these actionable tips in mind, and you’ll be well on your way to creating a compelling and well-organized literature review.

Wrapping up – Your literature review outline

As we conclude this extensive guide, we hope that you now feel equipped to craft a stellar literature review.

We’ve navigated the intricacies of an effective literature review outline, given you examples of each section, provided sentence starters to ignite your writing process, and explored the diverse types of literature reviews.

This guide has also illustrated how to structure a literature review and organize the research process, which should help you tackle any topic over time.

Emphasizing key themes, we’ve shown you how to identify gaps in existing research and underscore the relevance of your work.

Remember, writing a literature review isn’t just about summarizing existing studies; it’s about adding your own interpretations, arguing for the relevance of specific theoretical concepts, and demonstrating your grasp of the academic field.

Keep the key debates that have shaped your research area in mind, and use the strategies we’ve outlined to add depth to your paper.

So, start writing, and remember, the journey of writing is iterative and a pivotal part of your larger research process.

Dr Andrew Stapleton has a Masters and PhD in Chemistry from the UK and Australia. He has many years of research experience and has worked as a Postdoctoral Fellow and Associate at a number of Universities. Although having secured funding for his own research, he left academia to help others with his YouTube channel all about the inner workings of academia and how to make it work for you.

Thank you for visiting Academia Insider.

We are here to help you navigate Academia as painlessly as possible. We are supported by our readers and by visiting you are helping us earn a small amount through ads and affiliate revenue - Thank you!

2024 © Academia Insider

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

Want to Get your Dissertation Accepted?

Discover how we've helped doctoral students complete their dissertations and advance their academic careers!

Join 200+ Graduated Students

Get Your Dissertation Accepted On Your Next Submission

Get customized coaching for:.

- Crafting your proposal,

- Collecting and analyzing your data, or

- Preparing your defense.

Trapped in dissertation revisions?

How to write a literature review for a dissertation, published by steve tippins on july 5, 2019 july 5, 2019.

Last Updated on: 2nd February 2024, 04:45 am

Chapter 2 of your dissertation, your literature review, may be the longest chapter. It is not uncommon to see lit reviews in the 40- to 60-page range. That may seem daunting, but I contend that the literature review could be the easiest part of your dissertation.

It is also foundational. To be able to select an appropriate research topic and craft expert research questions, you’ll need to know what has already been discovered and what mysteries remain.

Remember, your degree is meant to indicate your achieving the highest level of expertise in your area of study. The lit review for your dissertation could very well form the foundation for your entire career.

In this article, I’ll give you detailed instructions for how to write the literature review of your dissertation without stress. I’ll also provide a sample outline.

When to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

Though technically Chapter 2 of your dissertation, many students write their literature review first. Why? Because having a solid foundation in the research informs the way you write Chapter 1.

Also, when writing Chapter 1, you’ll need to become familiar with the literature anyway. It only makes sense to write down what you learn to form the start of your lit review.

Some institutions even encourage students to write Chapter 2 first. But it’s important to talk with your Chair to see what he or she recommends.

How Long Should a Literature Review Be?

There is no set length for a literature review. The length largely depends on your area of study. However, I have found that most literature reviews are between 40-60 pages.

If your literature review is significantly shorter than that, ask yourself (a) if there is other relevant research that you have not explored, or (b) if you have provided enough of a discussion about the information you did explore.

Preparing to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

1. Search Using Key Terms

Most people start their lit review searching appropriate databases using key terms. For example, if you’re researching the impact of social media on adult learning, some key terms you would use at the start of your search would be adult learning, androgogy, social media, and “learning and social media” together.

If your topic was the impact of natural disasters on stock prices, then you would need to explore all types of natural disasters, other market factors that impact stock prices, and the methodologies used.

You can save time by skimming the abstracts first; if the article is not what you thought it might be you can move on quickly.

Once you start finding articles using key terms, two different things will usually happen: you will find new key terms to search, and the articles will lead you directly to other articles related to what you are studying. It becomes like a snowball rolling downhill.

Note that the vast majority of your sources should be articles from peer-reviewed journals.

2. Immerse Yourself in the Literature

When people ask what they should do first for their dissertation the most common answer is “immerse yourself in the literature.” What exactly does this mean?

Think of this stage as a trip into the quiet heart of the forest. Your questions are at the center of this journey, and you’ll need to help your reader understand which trees — which particular theories, studies, and lines of reasoning — got you there.

There are lots of trees in this particular forest, but there are particular trees that mark your path. What makes them unique? What about J’s methodology made you choose that study over Y’s? How did B’s argument triumph over A’s, thus leading you to C’s theory?

You are showing your reader that you’ve fully explored the forest of your topic and chosen this particular path, leading to these particular questions (your research questions), for these particular reasons.

3. Consider Gaps in the Research

The gaps in the research are where current knowledge ends and your study begins. In order to build a case for doing your study, you must demonstrate that it:

- Is worthy of doctoral-level research, and

- Has not already been studied

Defining the gaps in the literature should help accomplish both aims. Identifying studies on related topics helps make the case that your study is relevant, since other researchers have conducted related studies.

And showing where they fall short will help make the case that your study is the appropriate next step. Pay special attention to the recommendations for further research that the authors of studies make.

4. Organize What You Find

As you find articles, you will have to come up with methods to organize what you find.

Whether you find a computer-based system (three popular systems are Zotero, endNote, and Mendeley) or some sort of manual system such as index cards, you need to devise a method where you can easily group your references by subject and methodology and find what you are looking for when you need it. It is very frustrating to know you have found an article that supports a point that you are trying to make, but you can’t find the article!

One way to save time and keep things organized is to cut and paste relevant quotations (and their references) under topic headings. You’ll be able to rearrange and do some paraphrasing later, but if you’ve got the quotations and the citations that are important to you already embedded in your text, you’ll have an easier time of it.

If you choose this method, be sure to list the whole reference on the reference/bibliography page so you don’t have to do this page separately later. Some students use Scrivener for this purpose, as it offers a clear way to view and easily navigate to all sections of a written document.

Need help with your literature review? Take a look at my dissertation coaching and dissertation editing services.

How to Write the Literature Review for your Dissertation

Once you have gathered a sufficient number of pertinent references, you’ll need to string them together in a way that tells your story. Explain what previous researchers have done by telling the story of how knowledge on this topic has evolved. Here, you are laying the support for your topic and showing that your research questions need to be answered. Let’s dive into how to actually write your dissertation’s literature review.

1. Create an Outline

If you’ve created a system for keeping track of the sources you’ve found, you likely already have the bones of an outline. Even if not, it may be relatively easy to see how to organize it all. The main thing to remember is, keep it simple and don’t overthink it. There are several ways to organize your dissertation’s literature review, and I’ll discuss some of the most common below:

- By topic. This is by far the most common approach, and it’s the one I recommend unless there’s a clear reason to do otherwise. Topics are things like servant leadership, transformational leadership, employee retention, organizational knowledge, etc. Organizing by topic is fairly simple and it makes sense to the reader.

- Chronologically. In some cases, it makes sense to tell the story of how knowledge and thought on a given subject have evolved. In this case, sub-sections may indicate important advances or contributions.

- By methodology. Some students organize their literature review by the methodology of the studies. This makes sense when conducting a mixed-methods study, and in cases where methodology is at the forefront.

2. Write the Paragraphs

I said earlier that I thought the lit review was the easiest part to write, and here is why. When you write about the findings of others, you can do it in small, discrete time periods. You go down the path awhile, then you rest.

Once you have many small pieces written, you can then piece them together. You can write each piece without worrying about the flow of the chapter; that can all be done at the end when you put the jigsaw puzzle of references together.

The literature review is a demonstration of your ability to think critically about existing research and build meaningfully on it in your study. Avoid simply stating what other researchers said. Find the relationships between studies, note where researchers agree and disagree, and– especiallyy–relate it to your own study.

Pay special attention to controversial issues, and don’t be afraid to give space to researchers who you disagree with. Including differing opinions will only strengthen the credibility of your study, as it demonstrates that you’re willing to consider all sides.

4. Justify the Methodology

In addition to discussing studies related to your topic, include some background on the methodology you will be using. This is especially important if you are using a new or little-used methodology, as it may help get committee members onboard.

I have seen several students get slowed down in the process trying to get committees to buy into the planned methodology. Providing references and samples of where the planned methodology has been used makes the job of the committee easier, and it will also help your reader trust the outcomes.

Advice for Writing Your Dissertation’s Literature Review

- Remember to relate each section back to your study (your Problem and Purpose statements).

- Discuss conflicting findings or theoretical positions. Avoid the temptation to only include research that you agree with.

- Sections should flow together, the way sections of a chapter in a nonfiction book do. They should relate to each other and relate back to the purpose of your study. Avoid making each section an island.

- Discuss how each study or theory relates to the others in that section.

- Avoid relying on direct quotes–you should demonstrate that you understand the study and can describe it accurately.

Sample Outline of a Literature Review (Dissertation Chapter 2)

Here is a sample outline, with some brief instructions. Note that your institution probably has specific requirements for the structure of your dissertation’s literature review. But to give you a general idea, I’ve provided a sample outline of a dissertation ’s literature review here.

- Introduction

- State the problem and the purpose of the study

- Give a brief synopsis of literature that establishes the relevance of the problem

- Very briefly summarize the major sections of your chapter

Documentation of Literature Search Strategy

- Include the library databases and search engines you used

- List the key terms you used

- Describe the scope (qualitative) or iterative process (quantitative). Explain why and based on what criteria you selected the articles you did.

Literature Review (this is the meat of the chapter)

- Sub-topic a

- Sub-topic b

- Sub-topic c

See below for an example of what this outline might look like.

How to Write a Literature Review for a Dissertation: An Example

Let’s take an example that will make the organization, and the outline, a little bit more clear. Below, I’ll fill out the example outline based on the topics discussed.

If your questions have to do with the impact of the servant leadership style of management on employee retention, you may want to saunter down the path of servant leadership first, learning of its origins , its principles , its values , and its methods .

You’ll note the different ways the style is employed based on different practitioners’ perspectives or circumstances and how studies have evaluated these differences. Researchers will draw conclusions that you’ll want to note, and these conclusions will lead you to your next questions.

Next, you’ll want to wander into the territory of management styles to discover their impact on employee retention in general. Does management style really make a difference in employee retention, and if so, what factors, exactly, make this impact?

Employee retention is its own path, and you’ll discover factors, internal and external, that encourage people to stick with their jobs.

You’ll likely find paradoxes and contradictions in here that just bring up more questions. How do internal and external factors mix and match? How can employers influence both psychology and context ? Is it of benefit to try and do so?

At first, these three paths seem somewhat remote from one another, but your interest is where the three converge. Taking the lit review section by section like this before tying it all together will not only make it more manageable to write but will help you lead your reader down the same path you traveled, thereby increasing clarity.

Example Outline

So the main sections of your literature review might look something like this:

- Literature Search Strategy

- Conceptual Framework or Theoretical Foundation

- Literature that supports your methodology

- Origins, principles, values

- Seminal research

- Current research

- Management Styles’ Impact on employee retention

- Internal Factors

- External Factors

- Influencing psychology and context

- Summary and Conclusion

Final Thoughts on Writing Your Dissertation’s Chapter 2

The lit review provides the foundation for your study and perhaps for your career. Spend time reading and getting lost in the literature. The “aha” moments will come where you see how everything fits together.

At that point, it will just be a matter of clearly recording and tracing your path, keeping your references organized, and conveying clearly how your research questions are a natural evolution of previous work that has been done.

PS. If you’re struggling with your literature review, I can help. I offer dissertation coaching and editing services.

Steve Tippins

Steve Tippins, PhD, has thrived in academia for over thirty years. He continues to love teaching in addition to coaching recent PhD graduates as well as students writing their dissertations. Learn more about his dissertation coaching and career coaching services. Book a Free Consultation with Steve Tippins

Related Posts

Dissertation

What makes a good research question.

Creating a good research question is vital to successfully completing your dissertation. Here are some tips that will help you formulate a good research question. What Makes a Good Research Question? These are the three Read more…

Dissertation Structure

When it comes to writing a dissertation, one of the most fraught questions asked by graduate students is about dissertation structure. A dissertation is the lengthiest writing project that many graduate students ever undertake, and Read more…

Choosing a Dissertation Chair

Choosing your dissertation chair is one of the most important decisions that you’ll make in graduate school. Your dissertation chair will in many ways shape your experience as you undergo the most rigorous intellectual challenge Read more…

Make This Your Last Round of Dissertation Revision.

Learn How to Get Your Dissertation Accepted .

Discover the 5-Step Process in this Free Webinar .

Almost there!

Please verify your email address by clicking the link in the email message we just sent to your address.

If you don't see the message within the next five minutes, be sure to check your spam folder :).

Hack Your Dissertation

5-Day Mini Course: How to Finish Faster With Less Stress

Interested in more helpful tips about improving your dissertation experience? Join our 5-day mini course by email!

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples

Published on 22 February 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 7 June 2022.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research.

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarise sources – it analyses, synthesises, and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

Why write a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1: search for relevant literature, step 2: evaluate and select sources, step 3: identify themes, debates and gaps, step 4: outline your literature review’s structure, step 5: write your literature review, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a dissertation or thesis, you will have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position yourself in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your dissertation addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

You might also have to write a literature review as a stand-alone assignment. In this case, the purpose is to evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of scholarly debates around a topic.

The content will look slightly different in each case, but the process of conducting a literature review follows the same steps. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research objectives and questions .

If you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, you will have to choose a focus and develop a central question to direct your search. Unlike a dissertation research question, this question has to be answerable without collecting original data. You should be able to answer it based only on a review of existing publications.

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research topic. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list if you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can use boolean operators to help narrow down your search:

Read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

To identify the most important publications on your topic, take note of recurring citations. If the same authors, books or articles keep appearing in your reading, make sure to seek them out.

You probably won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on the topic – you’ll have to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your questions.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models and methods? Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- How does the publication contribute to your understanding of the topic? What are its key insights and arguments?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible, and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can find out how many times an article has been cited on Google Scholar – a high citation count means the article has been influential in the field, and should certainly be included in your literature review.

The scope of your review will depend on your topic and discipline: in the sciences you usually only review recent literature, but in the humanities you might take a long historical perspective (for example, to trace how a concept has changed in meaning over time).

Remember that you can use our template to summarise and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using!

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It’s important to keep track of your sources with references to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography, where you compile full reference information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

You can use our free APA Reference Generator for quick, correct, consistent citations.

To begin organising your literature review’s argument and structure, you need to understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly-visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat – this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organising the body of a literature review. You should have a rough idea of your strategy before you start writing.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarising sources in order.

Try to analyse patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organise your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text, your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

If you are writing the literature review as part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate your central problem or research question and give a brief summary of the scholarly context. You can emphasise the timeliness of the topic (“many recent studies have focused on the problem of x”) or highlight a gap in the literature (“while there has been much research on x, few researchers have taken y into consideration”).

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, make sure to follow these tips:

- Summarise and synthesise: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole.

- Analyse and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole.

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources.

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transitions and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts.

In the conclusion, you should summarise the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasise their significance.

If the literature review is part of your dissertation or thesis, reiterate how your research addresses gaps and contributes new knowledge, or discuss how you have drawn on existing theories and methods to build a framework for your research. This can lead directly into your methodology section.

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a dissertation , thesis, research paper , or proposal .

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarise yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, June 07). What is a Literature Review? | Guide, Template, & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 20 March 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, how to write a dissertation proposal | a step-by-step guide, what is a theoretical framework | a step-by-step guide, what is a research methodology | steps & tips.

Literature Review: Outline, Strategies, and Examples [2024]

![literature review chapter outline Literature Review: Outline, Strategies, and Examples [2024]](https://studycorgi.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/book-bible-close-up-beautiful-terrace-morning-time-space-text-1143x528.jpg)

Writing a literature review might be easier than you think. You should understand its basic rules, and that’s it! This article is just about that.

Why is the literature review important? What are its types? We will uncover these and other possible questions.

Whether you are an experienced researcher or a student, this article will come in handy. Keep reading!

What Is a Literature Review?

- Step-by-Step Strategy

Let’s start with the literature review definition.

Literature review outlooks the existing sources on a given topic. Its primary goal is to provide an overall picture of the study object. It clears up the context and showcases the analysis of the paper’s theoretical methodology.

In case you want to see the examples of this type of work, check out our collection of free student essays .

Importance of Literature Review

In most cases, you need to write a literature review as a part of an academic project. Those can be dissertations , theses, or research papers.

Why is it important?

Imagine your final research as a 100% bar. Let’s recall Pareto law: 20% of efforts make 80% of the result. In our case, 20% is preparing a literature review. Writing itself is less important than an in-depth analysis of current literature. Do you want to avoid possible frustration in academic writing? Make a confident start with a literature review.

Sure, it’s impossible to find a topic that hasn’t been discussed or cited. That is why we cannot but use the works of other authors. You don’t have to agree with them. Discuss, criticize, analyze, and debate.

So, the purpose of the literature review is to give the knowledge foundation for the topic and establish its understanding. Abstracting from personal opinions and judgments is a crucial attribute.

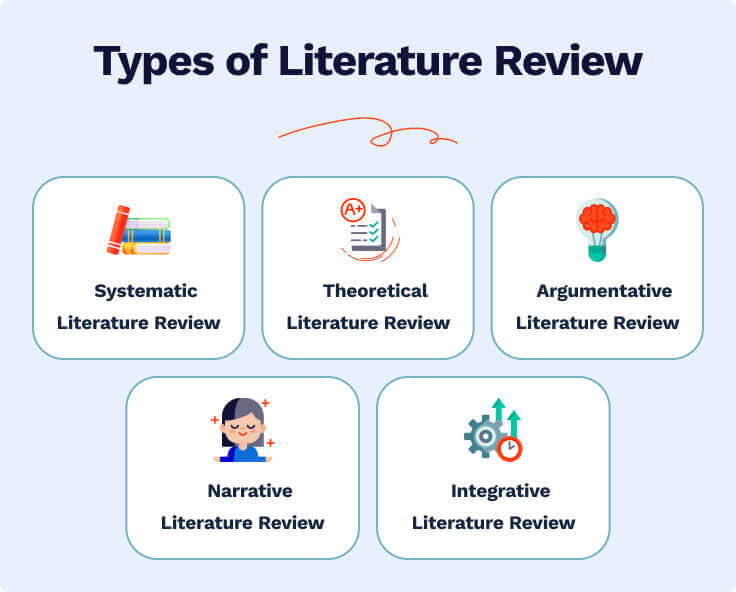

Types of Literature Review

You can reach the purpose we have discussed above in several ways, which means there are several types of literature review.

What sets them apart?

In short, it’s their research methods and structure. Let’s break down each type:

- Meta-analysis implies the deductive approach. At first, you gather several related research papers. Then, you carry out its statistical analysis. As a result, you answer a formulated question.

- Meta-synthesis goes along with the inductive approach. It bases qualitative data assessment.

- Theoretical literature review implies gathering theories. Those theories apply to studied ideas or concepts. Links between theories become more explicit and clear. Why is it useful? It confirms that the theoretical framework is valid. On top of that, it assists in new hypothesis-making.

- Argumentative literature review starts with a problem statement. Then, you select and study the topic-related literature to confirm or deny the stated question. There is one sufficient problem in this type, by the way. The author may write the text with a grain of bias.

- Narrative literature review focuses on literature mismatches. It indicates possible gaps and concludes the body of literature. The primary step here is stating a focused research question. Another name for this type — a traditional literature review.

- Integrative literature review drives scientific novelty. It generates new statements around the existing research. The primary tool for that is secondary data . The thing you need is to review and criticize it. When is the best option to write an integrative literature review? It’s when you lack primary data analysis.

Remember: before writing a literature review, specify its type . Another step you should take is to argue your choice. Make sure it fits the research framework. It will save your time as you won’t need to figure out fitting strategies and methods.

Annotated Bibliography vs. Literature Review

Some would ask: isn’t what you are writing about is just an annotated bibliography ? Sure, both annotated bibliography and literature review list the research topic-related sources. But no more than that. Such contextual attributes as goal, structure, and components differ a lot.

For a more visual illustration of its difference, we made a table:

To sum up: an annotated bibliography is more referral. It does not require reading all the sources in the list. On the contrary, you won’t reach the literature review purpose without examining all the sources cited.

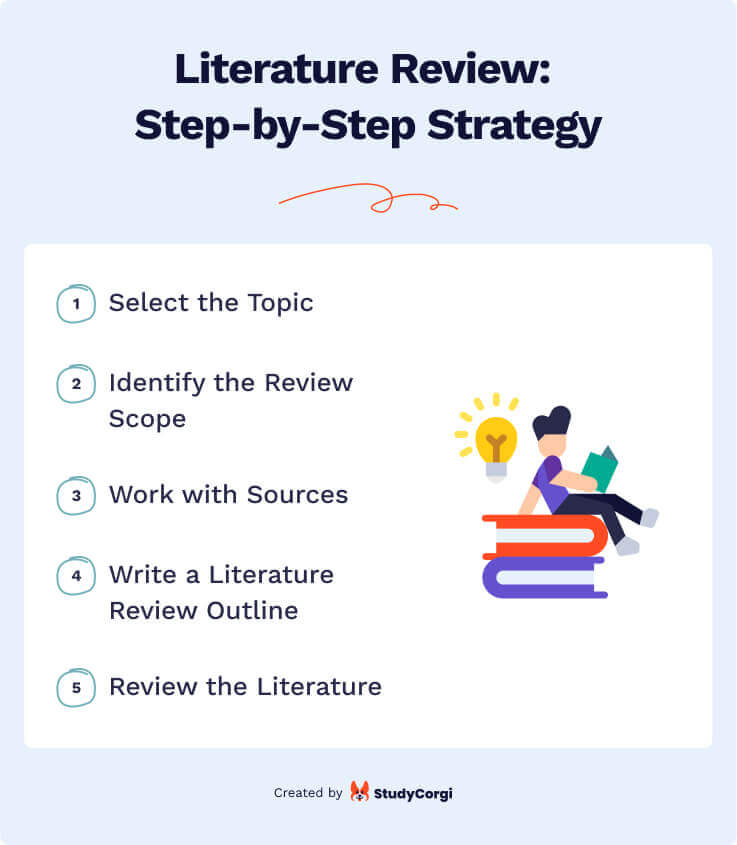

Literature Review: Step-by-Step Strategy

Now it’s time for a step-by-step guide. We are getting closer to a perfect literature review!

✔️ Step 1. Select the Topic

Selecting a topic requires looking from two perspectives. They are the following:

- Stand-alone paper . Choose an engaging topic and state a central problem. Then, investigate the trusted literature sources in scholarly databases.

- Part of a dissertation or thesis . In this case, you should dig around the thesis topic, research objectives, and purpose.

Regardless of the situation, you should not just list several literature items. On the contrary, build a decent logical connection and analysis. Only that way, you’ll answer the research question .

✔️ Step 2. Identify the Review Scope

One more essential thing to do is to define the research boundaries: don’t make them too broad or too narrow.

Push back on the chosen topic and define the number and level of comprehensiveness of your paper. Define the historical period as well. After that, select a pool of credible sources for further synthesis and analysis.

✔️ Step 3. Work with Sources

Investigate each chosen source. Note each important insight you come across. Learn how to cite a literature review to avoid plagiarism.

✔️ Step 4. Write a Literature Review Outline

No matter what the writing purpose is: research, informative, promotional, etc. The power of your future text is in the proper planning. If you start with a well-defined structure, there’s a much higher chance that you’ll reach exceptional results.

✔️ Step 5. Review the Literature

Once you’ve outlined your literature review, you’re ready for a writing part. While writing, try to be selective, thinking critically, and don’t forget to stay to the point. In the end, make a compelling literature review conclusion.

On top of the above five steps, explore some other working tips to make your literature review as informative as possible.

Literature Review Outline

We’ve already discussed the importance of a literature review outline. Now, it’s time to understand how to create it.

An outline for literature review has a bit different structure comparing with other types of paper works. It includes:

- Selected topic

- Research question

- Related research question trends and prospects

- Research methods

- Expected research results

- Overview of literature core areas

- Research problem consideration through the prism of this piece of literature

- Methods, controversial points, gaps

- Cumulative list of arguments around the research question

- Links to existing literature and a place of your paper in the existing system of knowledge.

It can be a plus if you clarify the applicability of your literature review in further research.

Once you outline your literature review, you can slightly shorten your writing path. Let’s move on to actual samples of literature review.

Literature Review Examples

How does a well-prepared literature review look like? Check these three StudyCorgi samples to understand. Follow the table:

Take your time and read literature review examples to solidify knowledge and sharpen your skills. You’ll get a more definite picture of the literature review length, methods, and topics.

Do you still have any questions? Don’t hesitate to contact us! Our writing experts are ready to help you with your paper on time.

❓ What Is the Purpose of a Literature Review?

Literature review solves several problems at once. Its purpose is to identify and gather the top insights, gaps, and answers to research questions. Those help to get a general idea of the degree of topic exploration. As a result, it forms a basis for further research. Or vice versa: it reveals a lack of need for additional studies.

❓ How Do You Structure a Literature Review?

Like any other academic paper, a literature review consists of three parts: introduction, main body, and the conclusion. Each of them needs full disclosure and logical interconnection

The introduction contains the topic overview, its problematics, research methods, and other general attributes of academic papers.

The body reveals how each of the selected literature sources answers the formulated questions from the introduction.

The conclusion summarizes the key findings from the body, connects the research to existing studies, and outlines the need for further investigation.

To ensure the success of your analysis, you should equally uphold all of these parts.

❓ What Must a Literature Review Include?

A basic literature review includes the introduction with the research topic definition, its arguments, and problems. Then, it has a synthesis of the picked pieces of literature. It may describe the possible gaps and contradictions in existing research. The practical relevance and contribution to new studies are also welcome.

❓ What Are the 5 C’s of Writing a Literature Review?

Don’t forget about these five C’s to make things easier in writing a literature review:

Cite . Make a list of references for research you’ve used and apply proper citation rules. Use Google Scholar for this.

Compare . Make a comparison of such literature attributes as theories, insights, trends, arguments, etc. It’s better to use tables or diagrams to make your content visual.

Contrast . Use listings to categorize particular approaches, themes, and so on.

Critique . Critical thinking is a must in any scientific research. Don’t take individual formulations as truth. Explore controversial points of view.

Connect . Find a place of your research between existing studies. Propose new possible areas to dig further.

❓ How Long Should a Literature Review Be?

In most cases, professors or educational establishment guidelines determine the length of a literature review. Study them and stick to their requirements, so you don’t get it wrong.

If there are no specific rules, make sure it is no more than 30% of the whole research paper.

If your literature review is not a part of the thesis and goes as a stand-alone paper — be concise but explore the research area in-depth.

- Literature Reviews – The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- What is a literature review? – The Royal Literary Fund

- Literature Review: Purpose of a Literature Review – University of South Carolina

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It – University of Toronto

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review – Florida A&M University Libraries

- Types of Literature Review – Business Research Methodology

- How to Conduct a Literature Review: Types of Literature Reviews – University Libraries

- Annotated bibliography VS. Literature Review – UNT Dallas Learning Commons

- Literature Review: Conducting & Writing – University of West Florida

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter X

- Share to LinkedIn

You might also like

105 literature review topics + how-to guide [2024], study guide on the epic of gilgamesh, essay topics & sample, the necklace: summary, themes, and a short story analysis.

- Library Accounts

Writing a Literature Review

- Getting Started

- Planning a review

- Exploring the Literature

- Managing the Review

Organizing and Writing the Review

Organizing the review, writing the review, online resources.

After selecting the citations for inclusion into the review, it is time to outline and organize the literature review. There are three basic components of a literature review: Introduction, Body, and Conclusion. Once the details of the outline are complete: it is time to write the literature review chapter of the research paper.

Introduction to the review. It should be brief, describing the body of the literature review in terms of format and logical structure. This covers areas such as the research problem, methodology, and the literature that addresses the context of the research study.