Tax Advisor

Istilah Pajak

Beberapa hari yang lalu saya mendapatkan file pdf dengan nama file 101TaxGlossary. Karena saya tahu penulisnya, saya meminta ijin untuk share ulang. Di sini saya ubah judulnya dengan Istilah Pajak.

101 Tax Glossary ditulis oleh Erikson Wijaya dan Noris Andika Pane.

Tax Accountant Profesi akuntan yang mengkhususkan pada analisis aspek perpajakan di setiap pencatatan akuntansi entitas/unit/individu Wajib Pajak yang ditanganinya. Profesi ini memungkinkan Wajib Pajak dapat memenuhi setiap hak dan kewajiban perpajakannya, antara lain: pelaporan SPT Tahunan/ Masa, pengurusan restitusi pajak, penyelesaian banding dan keberatan, atau pengajuan permohonan administrasi rutin lainnya

Tax Administration Segala sesuatu yang berkaitan dengan pelaksanaan/ operasionalisasi pemenuhan hak dan kewajiban perpajakan Wajib Pajak baik dari sisi Wajib Pajak maupun dari sisi petugas pajak. Rujukan pelaksanaan yang diambil sebagai pedoman dalam pelaksanaan tersebut adalah ketentuan perpajakan (Undang-Undang dan aturan pelaksanaan turunannya) yang disusun dan dilaksanakan oleh otoritas pajak di setiap negara masing-masing (Indonesia: Direktorat Jenderal Pajak- Kementerian Keuangan)

Tax Advantage Nilai ekonomi atau setara nilai uang yang dapat diperoleh atau berpotensi dapat diperoleh ketika Wajib Pajak menerapkan suatu ketentuan perpajakan tertentu secara sah dan tidak menyalahi aturan. Tax Advantage hanya dapat diperoleh jika Wajib Pajak memahami detil di setiap aspek transaksi. Setiap aspek tersebut mengandung ruang yang dapat dimanfaatkan untuk menghemat beban pajak. Ruang tersebut memang secara sah terbentuk akibat ketentuan perpajakan yang berlaku

Tax Advisor Suatu profesi yang memberikan layanan berupa bantuan pemenuhan kewajiban perpajakan sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku dengan mengedepankan upaya penghematan beban pajak tanpa menyalahi aturan perpajakan yang dijalankan. Tax Advisor memiliki batasan dalam menjalankan profesinya yakni hanya terbatas memberikan nasihat profesional dan menjelaskan skema strategis yang dapat dijalankan Wajib Pajak. Tax Advisor tidak diperkenankan menjalankan tugas pemenuhan kewajiban perpajakan sebagai perwakilan Wajib Pajak

Tax Allowance Sejumlah nilai uang yang dapat dikurangkan oleh Wajib Pajak dari penghasilan kotor untuk menghitung jumlah yang dapat dikenai pajak. Bagi pemberi kerja/ pemotong pajak, Tax Allowance berguna untuk menentukan dasar pengenaan pajak yang hendak dipotong/ dipungut. Dengan menerapkan Tax Allowance, Wajib Pajak atau Pemotong Pajak dapat menentukan dasar pengenaan pajak yang tepat.

Tax Amnesty Program pengampunan pajak yang diirilis penguasa/ pemerintah secara resmi dan terbatas waktu tertentu untuk memberikan kesempatan kepada Wajib Pajak agar mengakui ketidakpatuhan pemenuhan kewajiban perpajakan di masa-masa yang telah lewat dengan cara diberikan penghapusan/pengurangan beban pajak yang seharusnya terutang baik pokok dan atau sanksi yang menyertainya dengan maksud untuk memperoleh tambahan penerimaan pajak, meningkatkan kualitas basis pajak, dan sebagai bagian dari agenda reformasi sistem perpajakan

Tax Arbitrage Tax Arbitrage adalah upaya/praktik untuk memaksimalkan laba atau keuntungan dengan cara mengidentifikasi dan mengeksploitasi kompleksitas ketentuan perpajakan. Tax Arbitrage dilakukan dengan cara menata kembali pola atau model transaksi yang dilakukan Wajib Pajak menjadi suatu bentuk yang lebih memberikan penghematan atau penghilangan beban pajak yang dapat dikandung suatu transaksi bisnis. Frase arbitrage dalam konteks Tax Arbitrage dapat diartikan sebagai jalan tengah yang legal untuk menghadapi berbagai ketentuan perpajakan yang dikenakan terhadap Wajib Pajak.

Tax Arrears Tax Arrears adalah jumlah utang pajak yang dimiliki Wajib Pajak yang masih harus dibayar kepada negara/pemerintah namun oleh Wajib Pajak belum dilakukan pembayaran

Tax Aspect Tax Aspect adalah sebuah kondisi transaksi ekonomi/ keuangan yang dapat mengandung kewajiban/ konsekuensi perpajakan sehingga menjadi salah satu pertimbangan bagi pelaku untuk menerapkan pola transaksi tersebut. Semakin besar konsekuensi pajak yang harus ditanggung akibat Tax Aspect memuat kewajiban pajak dengan tarif yang lebih tinggi, maka makin besar kemungkinan transaksi trersebut dihindari.

Tax Assessment Tax Assessment merupakan sebuah praktik untuk menganalisis beragam aspek perpajakan dalam sebuah transaksi ekonomi/ non ekonomi. Tax Assessment biasa dilakukan oleh Wajib Pajak untuk mengukur seberapa besar konsekuensi beban pajak yang berpotensi ditanggung Wajib Pajak dalam melaksanakan sebuah rencana bisnis atau pribadi. Kemampuan mengurai konsekuensi perpajakan merupakan sebuah kemampuan dasar bagi siapapun yang bekerja di dunia Finance, Accountancy, dan Tax (biasa disingkat FAT).

Tax Auditing Tax Auditing merupakan salah satu cabang konsentrasi dalam administrasi atau pelaksanaan pekerjaan berkaitan dengan perpajakan dengan fokus berkaitan dengan pengujian kembali kualitas pemenuhan ketentuan perpajakan di dalam riwayat pelaporan dan pembayaran pajak yang telah dilakukan Wajib Pajak dalam suatu kurun waktu tertentu

Tax Authorities Tax Authorities merujuk pada sebuah entitas (kantor/unit/lembaga/badan) kelengkapan negara yang bekerja berdasarkan ketentuan undang-undang yang sah secara hukum negara tersebut dalam rangka menyelenggarakan operasional dan atau perumusan peratuan di bidang perpajakan.

Tax Autonomy Tax Autonomy adalah sebuah kebijakan administratif suatu negara untuk memberikan kebebasan secara otonom terhadap otoritas perpajakan di dalam aspek tertentu untuk menciptakan pola kerja yang lebih efisien, efektif, dan tepat sasaran. Penerapan Tax Autonomy dapat berupa pemisahan struktural otoritas pajak menjadi tidak lagi di bawah kendali Kementerian Keuangan melainkan langsung di bawah Presiden. Atau di beberapa negara, otoritas pajak tetap berada di bawah Kementerian Keuangan namun kuasa secara otonom diberikan untuk aspek tertentu seperti Sumber Daya Manusia, Keuangan, atau Penegakan Hukum

Tax Avoidance Tax Avoidance adalah istilah umum untuk menggambarkan praktik penghindaran pajak dengan menerapkan teknik-teknik yang legal dan tidak menyalahi ketentuan yang berlaku. Hal ini dimungkinkan bilamana Wajib Pajak memahami seluk beluk aturan perpajakan dan celah-celah yang dapat dimanfaatkan dengan maksud meminimalisir beban pajak yang harus dibayar.

Tax Barriers Tax Barriers adalah pajak yang dibebankan kepada produk-produk tertentu, biasanya produk impor sebelum masuk ke pasar dalam negeri sehingga harga produk tersebut menjadi lebih tinggi dengan maksud untuk melindungi kepentingan dalam negeri seperti produk industri lokal sejenis agar lebih bersaing.

Tax Base Tax Base adalah kumpulan objek pajak baik secara fisik atau melekat bersama subjek pajak dan atau wajib pajak yang memuat potensi pajak yang dapat dikenai pajak sesuai dengan ketentuan yang berlaku. Dapat pula Tax Base didefinisikan sebagai jumlah keseluruhan penghasilan, kekayaan, aset, konsumsi, transaksi, atau aktifitas ekonomi yang dapat dikenai pajak oleh negara.

Tax Benefit Tax Benefit secara umum merujuk pada istilah untuk menjelaskan nilai pajak yang dapat dihemat oleh Wajib Pajak. Adanya Tax Benefit dapat mengurangi beban pajak yang harus dibayar. Hal ini dapat terjadi karena Tax Benefit kerap kali berupa insentif berupa pengurangan atau keringanan yang diberikan kepada Wajib Pajak sebagai bentuk apresiasi untuk telah mematuhi ketentuan perpajakan yang berlaku atau mendorong tumbuhnya perekonomian di sektor tertentu

Tax Bracket Tax Bracket merujuk pada rentang penghasilan yang dikenai pajak dengan besaran tertentu tergantung pada besaran nilai di dalam rentang penghasilan dimaksud. Istilah Tax Bracket biasanya mengaju pada penerapan pajak dengan sifat yang progresif sebab semakin tinggi penghasilan maka semakin besar beban pajak yang dikenakan.

Tax Breaks Tax Break merupakan sebuah kebijakan yang diberikan pemerintah untuk mengurangi beban pajak yang harus dibayar Wajib Pajak dengan cara memberikan fasilitas pembebanan biaya/ perluasan pengurangan penghasilan bruto atau pengecualian pengenaan pajak atas penghasilan yang dilaporkan. Tax Break biasanya berlaku sementara dengan maksud sebagai bagian dari kebijakan pemerintah untuk mendorong iklim usaha di sektor tertentu.

Tax Buoyancy Tax Buoyancy adalah sebuah ukuran untuk menggambar tingkat perubahan atas pertumbuhan penerimaan pajak terhadap perubahan jumlah produk domestik bruto (pertumbuhan ekonomi). Dalam penerapannya, Tax Buoyancy dapat dihitung dengan cara membagi pertumbuhan penerimaan perpajakan (secara riil) dengan pertumbuhan ekonomi

Tax Burden Tax Burden adalah jumlah semua beban pajak atau dampak pajak terhadap total penghasilan yang diperoleh Wajib Pajak. Tax Burden merupakan sebuah konsep umum untuk menggambarkan adanya akumulasi beban akibat pajak yang dianggap dapat mengurangi kuantitas kekayaan Wajib Pajak.

Tax Capacity Tax Capacity adalah kemampuan yang dimiliki pemerintah suatu negara untuk mengumpulkan penerimaan pajak dari total seluruh potensi pajak yang dimiliki/ berhasil diidentifikasi. Ada sejumlah faktor yang mempengaruhi Tax Capacity sebuah negara yaitu: pertumbuhan ekonomi, kualitas infrastruktur, tingkat pendidikan warga negara, atau kondisi sektor penopang perekonomian negara tersebut.

Tax Capitalization Tax Capitalization adalah sebuah metode untuk menambahkan nilai suatu aset (atau penghasilan yang dapat dihasilkan sebuah aset) sejumlah selisih yang muncul akibat penurunan tarif pajak. Hal ini dapat dimungkinkan karena penurunan tarif pajak dapat meningkatkan penghasilan di masa mendatang. Akumulasi kenaikan tersebut dikapitalisasikan (ditambahkan sebagai nilai) ke dalam nilai aset

Tax Characteristics Tax Characteristics adalah sifat dasar pajak yang melekat secara umum. Konsep ini merujuk pada keberadaan aspek perpajakan dalam berbagai sudut pandang, terutama hukum dan bisnis

Tax Clearance Tax Clearance merupakan sebuah status yang menerangkan kualitas pemenuhan kewajiban perpajakan Wajib Pajak. Lazimnya, status tersebut dilegalkan dalam bentuk dokumen sertifikat fisik yang diterbitkan oleh otoritas pajak sebuah negara. Di Indonesia, dokumen tersebut adalah Surat Keterangan Fiskal.

Tax Code Tax Code adalah kumpulan ketentuan hukum perpajakan suatu negara sebagai satu kesatuan yang wajib dipatuhi Wajib Pajak dalam memenuhi hak dan kewajiban perpajakannya. Tax Code disusun menurut topik-topik pembahasan yang dapat diacu Wajib Pajak sebagai dasar legal dalam memahami administrasi dan prosedur perpajakan yang berlaku

Tax Coefficient Tax Coefficient memiliki arti yang tidak berbeda jauh dengan tax rate. Cofficient atau koefisien dalam bahasa indonesia adalah suatu konstanta yang bernilai mutlak dan tetap dapat mempengaruhi nilai suatu variabel dalam menghitung total keseluruhan nilai dalam sebuah persamaan. Berkaitan dengan pajak, maka tax coefficient dapat bermakna konstanta tertentu yang dimasukkan sebagai unsur dalam menghitung besaran suatu variabel untuk menentukan nilai akhir pajak yang terutang, biasanya penggunaan koefisien dalam menghitung pajak terjadi pada pajak daerah.

Tax Collections Tax Collections berkaitan dengan kegiatan pengumpulan pajak melalui mekanisme penagihan utang pajak kepada Wajib Pajak oleh petugas pajak (biasanya memiliki jabatan Jurusita Pajak Negara). Tax collections adalah salah satu unsur penunjang capaian target penerimaan pajak

Tax Competitions Tax Competitions adalah suatu kondisi persaingan antara negara/ yurisdiksi untuk memperebutkan investasi atau perusahaan multinasional dengan menawarkan tarif pajak yang lebih rendah atau administrasi perpajakan yang lebih sederhana dan mudah. Lazimnya, Tax Competitions berkenaan dengan Pajak Penghasilan badan dan Pajak Penghasilan atas karyawan/ tenaga kerja

Tax Compliance Tax Compliance adalah kondisi kualitas kepatuhan Wajib Pajak dalam memenuhi hak dan kewajiban perpajakan sesuai dengan ketentuan perpajakan yang berlaku. Berdasarkan mekanisme pemenuhannya, ada dua jenis kepatuhan pajak atau Tax Compliance, yakni kepatuhan yang dipaksakan (enforced compliance) dan kepatuhan sukarela (volutarily compliance). Sementara, menurut substansinya, ada dua jenis kepatuhan yaitu kepatuhan formal dan kepatuhan material.

Tax Composition Tax Composition berkenaan dengan kontribusi masing-masing jenis pajak dalam menyusun jumlah penerimaan pajak suatu negara/ yurisdiksi dalam rentang waktu tertentu. Konsep Tax Composition bermanfaat untuk mendapatkan gambaran mengenai peran berbagai jenis pajak yang ada dalam menyumbang capaian penerimaan pajak.

Tax Computation Tax Computation adalah suatu mekanisme dalam menyajikan/ menunjukkan proses penyesuaian penghasilan menurut akuntansi untuk kepentingan perpajakan agar dapat memperoleh nilai penghasilan yang dapat dikenai pajak. Penyesuaian untuk kepentingan perpajakan tersebut mencakup penghitungan biaya-biaya yang tidak dapat dikurangkan, penghasilan yang tidak dikenai pajak, pengurangan-pengurangan lainnya, dan tunjangan yang berkaitan dengan modal.

Tax Concesssions Tax Concession berkenaan dengan pengurangan atau pengecualian beban pajak yang harus dibayar sebagai bagian dari kebijakan pemerintah yang diberikan kepada wajib pajak baik badan maupun orang pribadi. Fasilitas pengurangan dalam Tax Concession diberikan pemerintah bagi Wajib Pajak yang memenuhi syarat yang ditetapkan, misalnya batas nilai peredaran usaha/ omset tidak melebihi nilai tertentu atau kelengkapan administrasi pembebanan biaya yang dapat dikurangkan.

Tax Consequences Tax Consequences merupakan sebuah konsep yang menjabarkan bagaimana proses munculnya kewajiban perpajakan yang harus dibayar akibat penerapan suatu mekanisme atau pola transaksi bisnis yang dijalankan Wajib Pajak dalam menjalankan kegiatan bisnisnya atau pribadinya.

Tax Cooperation Tax Cooperation merupakan sebuah praktik untuk menjalin kerjasama antara dua atau lebih otoritas perpajakan antar negara atau yurisdiksi dengan maksud untuk menyediakan kondisi/ iklim perpajakan yang efektif, akuntabel, dan transparan bagi Wajib Pajak suatu negara yang sedang menjalankan atau hendak menjalankan kegiatan bisnis atau investasi di satu atau lebih negara lainnya. Tax Cooperation juga dijalin dengan maksud untuk mengamankan potensi penerimaan pajak oleh negaranegara yang terlibat oleh Wajib Pajak dimaksud.

Tax Costs Tax Costs dapat juga disebut beban pajak. Di dalam laporan keuangan, beban pajak dibebankan sebagai biaya untuk menghitung penghasilan bersih suatu entitas. Beban pajak ini dihitung dengan mengalikan penghasilan bersih yang dikenai pajak dengan tarif pajak yang berlaku atas penghasilan tersebut.

Tax Court Tax Court atau Pengadilan Pajak merupakan suatu lembaga resmi yang dibentuk oleh negara dengan maksud untuk menyelenggarakan forum yudisial dimana Wajib Pajak dapat mengajukan permohonan banding terhadap keputusan utang pajak yang harus dibayar yang telah ditetapkan oleh otoritas perpajakan suatu negara/ yurisdiksi. Di Amerika Serikat, Tax Court dibentuk di setiap jenjang administratif pemerintahan mulai dari tingkat lokal, negara bagian, sampai dengan tingkat supreme (utama).

Tax Crime Tax Crime adalah istilah untuk menyebut suatu tindak pidana di bidang perpajakan yang dilakukan dengan sengaja sehingga menyebabkan kerugian pada pendapatan negara. Ada banyak bentuk tax crime dan setiap negara atau yurisdiksi memiliki definisi yang berbeda-beda. OECD sendiri bahkan memberikan cakupan tax crime juga meliputi tindakan untuk menghindari pajak dengan skema tertentu yang diatur dengan sengaja mencakup penyampaian data dan informasi yang tidak benar.

Tax Culture Tax Culture merupakan sebuah kondisi yang menggambarkan kualitas kesadaran pajak masyarakat dalam skala luas di suatu wilayah negara atau yurisdiksi. Budaya perpajakan, dalam pengertian umumnya, menunjukkan perilaku perpajakan dan norma perpajakan yang berlaku di negara tertentu. Sikap dan perilaku baik wajib pajak maupun pemungut pajak menjadi dasar yang mendasari budaya perpajakan.

Tax Cut Pemotongan pajak atau Tac Cut adalah pengurangan tarif pajak yang diberikan oleh pemerintah. Dampak langsung dari pemotongan pajak adalah penurunan pendapatan riil pemerintah dari penerimaan pajak dan peningkatan pendapatan riil bagi masyarakat atau pelaku bisnis/ usaha yang tarif pajaknya telah diturunkan.

Tax Debt Tax debt atau hutang pajak adalah pajak yang harus dibayar oleh Wajib Pajak kepada otoritas perpajakan negara tempat Wajib Pajak tinggal sebagai warga negara atau berdomisili setelah batas waktu pengajuan. Tidak masalah jika Wajib Pajak mengajukan pengembalian pajak sebelum batas waktu pengajuan dan membayar sebagian tagihan pajak. Sisa saldo masih akan dianggap sebagai hutang pajak.

Tax Declaration Pernyataan pendapatan, penjualan dan rincian lainnya dibuat oleh atau atas nama wajib pajak. Formulir sering kali disediakan oleh otoritas pajak untuk tujuan ini. Tax Declaration biasanya disampaikan dengan bentuk formulir Surat Pemberitahuan atau SPT

Tax Deductible Tax Deductible merupakan salah satu kelompok jenis biaya yang dapat menjadi pengurang penghasilan kotor/ laba kotor/ peredaran usaha dalam menghitung penghasilan bersih yang menjadi dasar pengenaan pajak.

Tax Delinquent Istilah Tax Delinquent digunakan untuk menyebut Penunggak Pajak. Suatu utang pajak menjadi tunggakan jika telah terlampaui batas waktu pelunasan namun oleh Wajib Pajak belum dilakukan pelunasan.

Tax Default Tax Default merupakan istilah untuk menyebut pajak yang gagal dibayar oleh Wajib Pajak baik dalam skema cicilan atau pelunasan. Dengan kata lain, setelah terlampaui batas waktu, tidak ada aktifitas pembayaran yang dilakukan Wajib Pajak atas tunggakan pajak tersebut. Sehingga penggunaan istilah Tax Default tepat digunakan untuk menyebut pajak yang gagal dibayar penunggak pajak.

Tax Discrimination Tax Discrimination mengacu pada praktik penerapan pembedaan pengenaan pajak yang dianggap tidak adil oleh sebagian orang, karena tidak mempengaruhi semua orang secara setara. Ketidakadilan ini dipicu oleh munculnya platform baru dalam bisnis yang tidak mengikuti kebijakan perpajakan pada waktunya.

Tax Disincentives Tax Disincentives adalah pengaruh yang disebabkan oleh pengenaan pajak yang mengakibatkan melemahnya atau berkurangnya kapasitas bisnis, nominal laba bersih, atau skala kegiatan usaha yang dijalankan Wajib Pajak. Tax Disincentives dapat berupa pengenaan pajak dengan tarif yang tinggi, pengenaan pajak berganda, atau administrasi pemenuhan hak dan kewajiban pajak yang dianggap tidak sederhana dan memakan waktu serta biaya.

Tax Dispute Tax Dispute atau Sengketa Pajak berarti setiap perselisihan oleh otoritas Pajak dengan Wajib Pajak atau sebaliknya (termasuk melalui penerbitan penilaian atau substansi dalam surat menyurat yang resmi diterbitkan otoritas pajak) yang menyatakan bahwa kewajiban Pajak dapat timbul atau bahwa Keringanan Pajak mungkin tidak tersedia lagi untuk dibahas antara kedua belah pihak.

Tax Dodge Tax Dodge adalah suatu praktik ilegal atau bertentangan dengan hukum perpajakan yang berlaku untuk mengurangi jumlah beban pajak yang harus dibayar oleh Wajib Pajak dalam suatu kurun waktu tertentu.

Tax Effect Tax Effect merupakan istilah untuk menggambarkan konsekuensi berupa pajak yang harus dibayar akibat penerapan skenario atau metode tertentu untuk kepentingan menghitung utang pajak atau beban pajak yang harus dibayar. Tax Effect juga kerap digunakan untuk menggambarkan beban pajak yang muncul akibat pengenaan pajak atas seluruh penghasilan yang baru terdeteksi oleh otoritas dikurangi pajak atas penghasilan yang telah dilaporkan di dalam Surat Pemberitahuan pajak.

Tax Effort Tax Effort merupakan suatu angka untuk menunjukkan perbandingan antara nilai penerimaan pajak secara riil terhadap total potensi penerimaan pajak dalam satu periode yang sama di suatu negara atau yurisdiksi. Penggunaan angka dalam Tax Effort memungkinkan pengelompokkan negara menjadi berbagai kategori berikut: low tax collection, low tax effort; high tax collection, high tax effort; low tax collection, high tax effort; and high tax collection, low tax effort.

Tax Enforcement Tax Enforcement adalah tindakan untuk menerapkan hukum perpajakan yang diamanatkan di dalam ketentuan perpajakan suatu otoritas pajak sebuah negara atau yurisdiksi. Tujuan tax enforcement adalah untuk meningkatkan kepatuhan Wajib Pajak dalam memenuhi hak dan kewajiban perpajakannya, meningkatkan penerimaan pajak, dan menciptakan budaya patuh pajak di masyarakat. Tax Enforcement dilakukan dengan penerapan pengenaan sanksi administrasi dan pidana secara tegas dan adil kepada Wajib Pajak yang melanggar ketentuan perpajakan.

Tax Environment Tax Environment merupakan kebijakan untuk mengenakan pajak atas aktifitas bisnis dan atau aktifitas keseharian masyarakat yang berpotensi mencemari lingkungan dengan berbagai bentuk.

Tax Equity Tax Equity adalah prinsipi keadilan dalam pengenaan pajak. Dengan maksud agar pembebanan pajak kepada Wajib Pajak/ masyarakat harus mengedepankan semangat persamaan beban dan pertimbangan kemampuan.

Tax Evasion Tax Evasion adalah suatu upaya untuk dengan sengaja melanggar ketentuan perpajakan yang berlaku dengan maksud untuk tidak membayar pajak atau membayar dengan jumlah yang lebih rendah daripada yang seharusnya dibayar. Tax Evasion dipandang mengandung aspek tindak pidana di bidang perpajakan.

Tax Exemption Tax Exemption atau Pembebasan pajak adalah pengurangan atau penghapusan kewajiban untuk melakukan pembayaran wajib yang semula dikenakan oleh otoritas pajak kepada Wajib Pajak atas perolehan penghasilan oleh melalui orang, properti, pendapatan, atau transaksi.

Tax Exhaustion Tax Exhaustion merujuk pada batas maksimal kemampuan Wajib Pajak atau Orang Pribadi dalam memenuhi kemampuan membayar pajak. Batas maksimal sebagaimana dimaksud mencakup jumlah nominal uang yang paling banyak dibayarkan oleh Wajib Pajak.

Tax Exile Tax Exile merujuk pada status orang pribadi atau badan hukum yang memutuskan semua ikatan yang membuatnya menjadi penduduk fiskal di negara tertentu dan pindah ke yurisdiksi lain karena alasan pajak.

Tax Expenditure Tax Expenditure atau Belanja Pajak adalah ketentuan khusus dari peraturan pajak yang mengatur beberapa ketentuan seperti pengecualian, pemotongan, penangguhan, kredit, dan tarif pajak yang menguntungkan kegiatan atau kelompok pembayar pajak tertentu. Dengan demikian, pengeluaran pajak seringkali merupakan alternatif dari program atau peraturan pengeluaran langsung untuk mencapai tujuan yang sama

Tax Expense Tax Expense atau belanja untuk membayar pajak adalah akun tertentu di dalam laporan keuangan Wajib Pajak yang menunjukkan jumlah pajak yang dibayar oleh Wajib Pajak dalam suatu periode tertentu. Dengan kata lain, Tax Expense didefinisikan dari sudut pandang Wajib Pajak.

Tax Firm Tax Firm merupakan sebuah bentuk usaha profesional di bidang perpajakan yang dijalankan oleh para profesional yang memiliki keahlian dan pengalaman di bidang perpajakan untuk memberikan bantuan profesional kepada Wajib Pajak dan masyarakat dalam memenuhi hak dan kewajiban perpajakannya. Keberadaan Tax Firm menjadi jembatan antara Wajib Pajak dengan otoritas pajak sehingga ketika berjalan dengan baik, Tax Firm dapat membantu terwujudnya komunikasi yang baik antara otoritas pajak dengan Wajib Pajak.

Tax Free Tax Free adalah sebuah kondisi dimana sebuah transaksi bisnis yang dijalankan Wajib Pajak tidak dikenai pajak sama sekali dikarenakan transaksi bisnis tersebut menggunakan skema yang memang secara legal tidak dikenai pajak atau dapat pula karena penghasilan yang diperoleh memang tidak termasuk objek pajak yang dikenai pajak.

Tax Gap Tax Gap merupakan istilah untuk menggambarkan jumlah selisih pajak yang terkumpul tepat waktu sebagai penerimaan negara dengan jumlah pajak terutang. Tax Gap muncul sebagai istilah untuk menjelaskan jumlah persentase utang pajak yang belum kadaluarsa namun belum tertagih.

Tax Home Tax Home adalah sebuah istilah untuk menjelaskan kondisi tempat kerja atau jabatan rutin wajib pajak, di mana pun wajib pajak memiliki rumah keluarga.

Tax Haven Tax Haven atau Surga pajak dalam pengertian “klasik” mengacu pada negara yang mengenakan pajak rendah atau tidak ada pajak, dan digunakan oleh perusahaan untuk menghindari pajak yang jika tidak, akan dibayarkan di negara asal dengan pajak tinggi. Menurut laporan OECD, tax havens memiliki karakteristik utama sebagai berikut; Tidak ada atau hanya pajak nominal; Kurangnya pertukaran informasi yang efektif; Kurangnya transparansi dalam pelaksanaan ketentuan legislatif, hukum atau administratif.

Tax Holiday Tax holiday adalah kebijakan hukum yang secara resmi dikeluarkan oleh otoritas pajak suatu negara/yurisdiksi yang menawarkan periode pembebasan pajak penghasilan untuk jenis usaha baru atau usaha tertentu guna mengembangkan atau mendiversifikasi industri dalam negeri.

Tax Hell Tax Hell atau Neraka Pajak merujuk pada negara/yurisdiksi dengan tarif pajak yang sangat tinggi. Dalam beberapa definisi, neraka pajak juga berarti birokrasi pajak yang menindas atau memberatkan. Di Amerika Serikat, negara bagian dengan tarif pajak yang sangat tinggi adalah Wisconsin, yang secara geografis berdekatan dengan Minnesota dan North Dakota.

Tax Incentives Tax Incentives atau Insentif Pajak adalah kebijakan yang secara resmi dirilis oleh otoritas pajak suatu negara/ yurisdiksi dalam bentuk pembebasan pajak, pengurangan tarif pajak, atau pajak ditanggung negara dengan maksud untuk membantu perkembangan bisnis, kelancaran likuiditas, atau meningkatkan kepatuhan pajak. Tax Incentives diberikan dalam jangka waktu tertentu, dengan kata lain, bukan merupakan sebuah kebijakan yang tetap

Tax Incidences Tax Incidences atau insiden pajak adalah istilah ekonomi untuk memahami pembagian beban pajak antara pemangku kepentingan, seperti pembeli dan penjual atau produsen dan konsumen. Insiden pajak juga dapat dikaitkan dengan elastisitas harga penawaran dan permintaan.

Tax Inclusives Tax Inclusives berarti pajak sudah menjadi bagian dari harga eceran produk, jadi tidak ada lagi pajak yang ditambahkan ke subtotal dari transaksi penjualan. Sedangkan Tax Exclusive artinya pajak diterapkan di atas harga satuan.

Tax Increment Tax Increment adalah istilah dalam keuangan publik. Tax Increment adalah sebuah metode untuk menjadikan pajak sebagai salah satu alat untuk mendukung proyek pengembangan kembali kegiatan perekonomian di suatu wilayah dengan menggunakan dana pajak yang diperkirakan dapat dikumpulkan dari properti atau objek pajak di wilayah tersebut sepanjang kurun waktu tertentu. Pembiayaan melalui kenaikan pajak/ Tax Increment dapat pula dimaknai sebagai metode pembiayaan publik yang dapat digunakan sebagai subsidi untuk pembangunan kembali, infrastruktur, dan proyek peningkatan masyarakat lainnya di banyak negara, termasuk Amerika Serikat.

Tax Intelligence Tax Intelligence adalah sebuah istilah untuk mengoptimalkan semua sumber daya berupa informasi, teknologi, jejaring relasi, dan sumber daya manusia dalam melakukan pendalaman untuk kepentingan penelurusan kondisi subjektif dan objektif Wajib Pajak, pengujian kepatuhan pajak, penegakan hukum perpajakan, dan penyusunan profil Wajib Pajak. Di banyak otoritas pajak di berbagai negara/yurisdiksi, Tax Intelligence telah dilembagakan menjadi unit yang secara resmi menjalankan fungsi-fungsi intelijen.

Tax Investigations Tax Investigations adalah suatu mekanisme penegakan hukum pajak yang dilakukan oleh petugas pajak dengan jabatan tertentu dengan maksud untuk membuktikan unsur pidana dari tindak pidana perpajakan yang disangkakan kepada Wajib Pajak.

Tax Invoices Tax Invoices atau Faktur Pajak adalah dokumen tertulis yang diterbitkan dan dibuat oleh Wajib Pajak penjual kepada Wajib Pajak pembeli yang menunjukkan deskripsi, jumlah, nilai barang dan jasa serta pajak yang dibebankan. Faktur Pajak diterbitkan, lazimnya, jika barang dijual dengan maksud untuk dijual kembali oleh pembeli.

Tax Laws Tax Laws atau hukum pajak adalah seperangkat aturan dan ketentuan yang mengatur dan menetapkan perihal bagaimana, kapan, dan berapa banyak pajak yang harus dibayar ke otoritas pajak di setiap jenjang dan ketentuan yang berlaku.

Tax Loopholes Tax Loopholes adalah celah-celah yang dapat dimanfaatkan dalam undang-undang, pengaruh tax avoidance (penghindaran pajak) untuk meminimalkan beban pajak.

Tax Lien Tax Lien adalah notifikasi berupa klaim resmi yang disampaikan oleh pemerintah atas aset berupa properti yang dimiliki Wajib Pajak yang belum membayar Pajak Penghasilan setelah lampau jatuh tempo yang ditetapkan. Ketika notifikasi atau Tax Lien telah disampaikan atau ditetapkan pemerintah, maka Tax Lien dapat dihapus dengan cara Wajib Pajak membayar tagihan pajak yang terutang yang mana jika tidak dilakukan pembayaran maka atas aset yang telah diberi notifikasi Tax Lien dapat dilakukan penyitaan.

Tax Liability Tax Liability adalah jumlah uang yang menjadi utang pajak yang harus dibayar ke otoritas pajak/ pemerintah, Tax Liability mencerminkan jumlah pajak secara keseluruhan yang harus dilakukan pelunasan ke pemerintah oleh Wajib Pajak

Tax Liability Tax Litigation berarti setiap klaim, tindakan hukum, persidangan, gugatan, litigasi, penuntutan, penyelidikan, arbitrase atau proses penyelesaian sengketa lainnya, atau proses administratif atau pidana, atau tindakan otoritas pajak (atau penilaian, keputusan, perintah, perintah atau keputusan yang berkaitan dengan salah satu dari hal tersebut di atas) yang berkaitan dengan pajak.

Tax Multiplier Tax Multiplier menunjukkan ukuran sebuah perubahan Pendapatan Domestik Bruto (PDB) yang dapat terjadi ketika pemerintah melakukan penyesuaian melalui kebijakan pajak. Kompleksitas Tax Multiplier ditentukan oleh lingkup perubahan yang dilakukan, apakah hanya berkaitan dengan konsumsi atau seluruh komponen PDB.

Tax Morale Tax Morale adalah ukuran yang menunjukkan persepsi dan sikap Wajib Pajak terhadap kewajiban membayar pajak dan kecenderungan untuk menghindari pajak. Ada sejumlah faktor yang mempengaruhi Tax Morale antara lain usia, tingkat pendidikan, jenis kelamin, dan tingkat kepercayaan terhadap pemerintah.

Tax Neutrality Tax Neutrality merujuk pada sebuah konsep/ sistem yang membuat pajak tidak menjadi unsur yang mempengaruhi keputusan individu atau korporasi dalam mengambil keputusan berkenaan dengan bisnis, investasi, atau hal lainnya. Ide dasar dari konsep Tax Neutrality adalah sikap pemerintah untuk mendorong berjalannya kegiatan ekonomi oleh pelaku bisnis tanpa dibebani oleh sistem perpajakan yang dianggap dapat memberatkan.

Tax Nexus Istilah “nexus” dalam Tax Nexus digunakan dalam undang-undang perpajakan untuk menggambarkan situasi di mana bisnis dapat terdampak oleh pajak di negara atau yurisdiksi tertentu. Nexsus pada dasarnya adalah hubungan antara otoritas perpajakan dan entitas yang harus memungut atau membayar pajak.

Tax Ombudsman Tax Ombudsman merujuk pada lembaga khusus yang dibentuk otoritas pajak dengan maksud untuk menerima keluhan, kritik, dan saran, serta pengaduan dari Wajib Pajak terkait kualitas pelayanan dan pelaksanaan administrasi hak dan kewajiban perpajakan. Tax Ombudsman mengeluarkan rekomendasi yang bersifat tidak mengikat untuk dilaksanakan otoritas perpajakan.

Tax Penalty Tax Penalty atau denda pajak yang diberlakukan pada Wajib Pajak individu atau korporasi karena tidak membayar cukup atau tidak membayar secara keseluruhan dari perkiraan total pajak terutang atau pajak yang telah dilakukan pemotongan. Jika Wajib Pajak mengalami hal tersebut sehingga menimbulkan kurang bayar atau tidak membayar sama sekali dari total taksiran pajak, mereka mungkin diharuskan membayar denda.

Tax Potential Tax Potential atau potensi pajak adalah jumlah maksimum penerimaan pajak yang mungkin dapat diupayakan dan ditingkatkan pemerintah dalam satu rentang waktu sesuai dengan karakteristik-karakteristik yang dapat diidentifikasi.

Tax Planning Tax Planning adalah proses menganalisis rencana keuangan atau situasi dari sudut pandang pajak dengan maksud untuk memastikan dapat dicapainya efisiensi beban pajak yang harus dibayar tanpa melanggar ketentuan perpajakan yang berlaku.

Tax Policy Tax Policy merupakan suatu pilihan (kebijakan) yang diambil pemerintah berkaitan dengan jenis pajak yang dikenakan, besaran tarif dan jumlah yang ditagihkan, dan subjek pajak yang dibebani kewajiban pajak dimaksud.

Tax Practice Tax Practice merupakan istilah untuk menyebutkan kegiatan yang berkenaan dengan administrasi perpajakan, lazimnya istilah ini merujuk pada kegiatan penyediaan jasa praktik pemenuhan hak dan kewajiban perpajakan oleh profesional di bidang perpajakan, khususnya konsultan pajak

Tax Preparer Tax Preparer adalah profesional yang berkualifikasi untuk menghitung, menyampaikan/ melaporkan, dan menandatangani Surat Pemberitahuan (SPT) atas nama Wajib Pajak individu/ orang pribadi atau korporasi/ bisnis.

Tax Provision Tax Provision adalah proses menyusun estimasi jumlah yang pajak yang harus dibayar oleh Wajib Pajak pada tahun pajak yang bersangkutan. Proses tersebut mencakup penghitungan nilai pajak yang harus dibayar dan yang ditangguhkan (aset dan kewajiban pajak tangguhan).

Tax Principles Tax Principles merupakan panduan yang menjadi petunjuk otoritas pajak dalam merumuskan kebijakan perpajakan. Tax Principles tersebut dirumuskan oleh pakar di bidang perpajakan yang biasanya masih dianggap relevan sampai dengan kurun waktu tertentu.

Tax Progressivity Tax Progressivity adalah sebuah mekanisme penerapan tarif pajak yang meningkat seiring dengan kenaikan penghasilan Wajib Pajak. Lawan dari mekanisme ini adalah Tax Regressivity dimana pajak dikenakan dengan tarif yang sama meskipun penghasilan Wajib Pajak bertambah.

Tax Proposal Tax Proposal merupakan bagian yang tidak terpisahkan dari Tax Reform, dimana otoritas pajak, setelah menimbang berbagai rekomendasi dan evaluasi, mengajukan suatu proposal kebijakan perpajakan yang dianggap mampu memberikan solusi atas sejumlah permasalahan yang dialami pada periode sebelumnya.

Tax Ratio Tax Ratio atau tax-to-GDP ratio adalah sebuah ukuran yang menunjukkan dalam perbandingan antara jumlah total penerimaan pajak suatu negara yang dapat dikumpulkan dalam satu tahun pajak terhadap ukuran total kegiatan perekonomiannya yang dinyatakan dalam Produk Domestik Bruto atau PDB

Tax Rebellion Tax Rebellion merupakan tindakan untuk secara terbuka menentang kebijakan perpajakan dengan menunjukkan perlawanan dengan tidak memenuhi kewajiban untuk mematuhi ketentuan perpajakan baik formal maupun material. Di Amerika Serikat, Tax Rebellion secara simbolik ditandai dengan peristiwa Boston Tea Party, yakni sebuah peristiwa yang terjadi tanggal 16 Desember 1773, di mana kolonialis Amerika yang melakukan protes karena mereka harus membeli teh dari Britania Raya dan harus membayar pajak. Mereka lalu membuang teh-teh itu ke Pelabuhan Boston di Boston Harbor, Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

Tax Reform Tax Reform adalah proses untuk mengubah kebijakan berkenaan dengan mekanisme pengenaan dan pemungutan pajak oleh pemerintah dan lazimnya dilaksanakan dengan maksud untuk meningkatkan kualitas administrasi perpajakan atau untuk mendorong aktifitas sosial dan ekonomi menjadi lebih baik.

Tax Regimes Tax Regimes merujuk pada sebuah corak, ciri khas, atau karakteristik kebijakan perpajakan suatu negara/ yursdiksi ketika di bawah rezim pemerintah/ penguasa dalam rentang waktu tertentu. Setiap masa pemerintahan dapat menjalankan kebijakan perpajakan yang berbeda-beda, tergentung keputusan yang ditetapkan pemerintah yang berkuasa saat itu.

Tax Research Tax Research, dalam dunia profesional para konsultan pajak, digunakan untuk menunjukkan aktivitas menemukan dasar hukum dalam membangun sikap untuk menanggapi suatu kebijakan perpajakan. Dalam dunia ilmiah, Tax Research merupakan aktifitas untuk melakukan penelitan isu tertentu dengan metode yang baku dengan maksud untuk membuktikan hipotesis yang dibangun dengan dugaan atau asumsi.

Tax Resistence Tax Resistence merujuk pada sikap yang mencirikan keengganan dalam mematuhi kewajiban perpajakan, sikap tersebut tercermin dalam bentuk perlawanan baik pasif maupun aktif. Tax Rebellion adalah salah satu bentuk Tax Resistence berupa perlawanan aktif.

Erikson Wijaya Telah berkarir sebagai pegawai Ditjen Pajak Kemenkeu sejak tahun 2006, dan saat ini tengah berstatus sebagai Pegawai Tugas Belajar di University of Minnesota, USA untuk program Master of Business Taxation (MBT)

Noris Andika Pane Telah berkarir sebagai pegawai Ditjen Pajak Kemenkeu selama 15 tahun, dan saat ini tengah berstatus sebagai Account Representative (AR) di KPP Pratama Kisaran yang merupakan KPP di lingkungan Kanwil DJP Sumatera Utara II

Istilah Pajak Dalam Bahas Inggris

Seringkali kita mencari padanan istilah pajak dalam bahasa Inggris. Ya, karena kita belajarnya di Indonesia sehingga saat mau diterjemahkan ke dalam bahasa Inggris, kita mencari istilah baku.

Menteri Keuangan telah menetapkan istilah-istilah baku dalam bahasa Indonesia dan bahasa Inggris. Istilah-istilah dimaksud ada dalam lampiran Keputusan Menteri Keuangan nomor nomor 914/KMK.01/2016 tentang Standar Terminologi/Istilah dalam Bahasa Inggris di Lingkungan Kementerian Keuangan.

Dalam beleid ini terdapat 1295 istilah yang biasa digunakan di lingkungan Kementerian Keuangan. Termasuk istilah-istilah baku perpajakan.

Berikut lampiran dimaksud :

Bantu Share di

- Klik untuk berbagi pada Twitter(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk membagikan di Facebook(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi di Linkedln(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi pada Pinterest(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi di Telegram(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi di WhatsApp(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi pada Tumblr(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk berbagi via Pocket(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

- Klik untuk mengirimkan email tautan ke teman(Membuka di jendela yang baru)

Menyukai ini:

Author: Raden Agus Suparman

Pegawai DJP sejak 1993 sampai Maret 2022. Konsultan Pajak sejak April 2022. Alumni magister administrasi dan kebijakan perpajakan angkatan VI FISIP Universitas Indonesia. Perlu konsultasi? Sila kirim email ke [email protected] atau 08888110017 Terima kasih sudah membaca tulisan saya di aguspajak.com Semoga aguspajak menjadi rujukan pengetahuan perpajakan. View all posts by Raden Agus Suparman

Eksplorasi konten lain dari Tax Advisor

Langganan sekarang agar bisa terus membaca dan mendapatkan akses ke semua arsip.

Type your email…

Lanjutkan membaca

Definisi Manajemen Perpajakan (Tax Management)

Oleh Rachel Yolanda Pratiwi S 27/01/2023, 10:00 1.8k Views 1 Vote 0 Comments

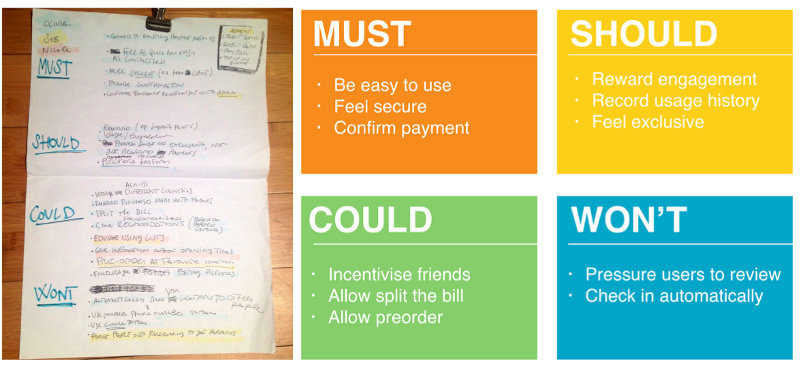

Definisi manajemen perpajakan ( tax management ) adalah usaha menyeluruh yang dilakukan manajer pajak ( tax manager ) dalam suatu perusahaan atau organisasi. Sehingga, hal-hal yang bersangkutan dengan perpajakan dari perusahaan atau organisasi tersebut dapat dikelola dengan baik, efisien dan ekonomis dan memberi kontribusi maksimal bagi perusahaan. Tujuan manajemen pajak dapat dicapai melalui fungsi-fungsi manajemen pajak yang terdiri dari:

- Perencanaan Pajak ( tax planning );

- Pelaksanaan kewajiban perpajakan ( tax implementation )

- Pengendalian Pajak ( tax control ).

Seperti yang sudah dibahas sebelumnya, perencanaan pajak ( tax planning ) adalah suatu alat dan suatu tahap awal dalam manajemen pajak ( tax management ), yang berfungsi untuk menampung aspirasi yang berkembang dari sifat dasar manusia. Secara definitive, manajemen pajak memiliki ruang lingkup yang lebih luas dari sekedar tax planning. Sebagai manajemen pajak, pastilah hal tersebut tidak terlepas dari konsep manajemen secara umum yang merupakan upaya-upaya sistematis yang meliputi:

- Perencanaan ( planning )

- Pengorganisasian ( organizing )

- Pelaksanaan ( actuating ) dan

- pengendalian ( controlling ).

Semua fungsi manajemen tersebut tercakup dalam manajemen pajak. Dengan kata lain, manajemen perpajakan merupakan segenap upaya untuk mengimplementasikan fungsi-fungsi manajemen agar pelaksanaan hak dan kewajiban perpajakan berjalan efisien dan efektif. Dalam melaksanakan fungsi manajemen pajak, perencanaan pajak merupakan tahap pertama dalam urutan hierarki. Dalam praktik bisnis, istilah tax planning lebih popular dari pada tax management itu sendiri.

Praktik pendekatan yang dilakukan dalam implementasi tax planning ini bersifat multidisipliner, sehingga wajar bila seorang perencana pajak yang baik ( tax planner ) harus memiliki wawasan dan pengetahuan yang luas dan selalu memperbarui setiap ketentuan, termasuk perubahannya dari waktu ke waktu.

Tax Planning adalah suatu proses mengorganisasi usaha wajib pajak sedemikian rupa, agar utang pajaknya berada dalam jumlah minimal, selama hal tersebut tidak melanggar undang-undang. Kemudian, perencanaan pajak dimulai dengan menyiapkan semua data yang diperlukan dan format penyajiannya, memerhatikan setiap pembayaran dan pelaporan pajak setiap masa pajak dan setiap akhir tahun pajak, dan mengawasi rekonsiliasi laporan keuangan komersial dan fiskal.

Setelah semua ini dilakukan dengan baik berdasarkan peraturan perpajakan dan memiliki pemahaman yang baik tentang keadaan perusahaan, dapat diterapkan suatu strategi manajemen perpajakan seefisien mungkin. Hal ini yang perlu diperhatikan adalah mengatur cash flow perusahaan seefektif mungkin dengan tetap memerhatikan ketentuan perpajakan.

Ada beberapa manfaat yang bisa diperoleh dalam perencanaan pajak yang dilakukan secara cermat, yaitu:

- penghematan kas keluar, sebab beban pajak yang merupakan unsur biaya dapat dikurangi;

- pengatur aliran kas masuk dan keluar ( cash flow ), sebab perencanaan pajak yang matang bisa memperkirakan kebutuhan kas untuk pajak dan menentukan saat pembayaran. Sehingga, perusahaan dapat menyusun anggaran kas secara lebih akurat.

Secara umum tujuan pokok yang ingin dicapai dari manajemen pajak atau perencanaan pajak yang baik adalah:

- Meminimalkan beban pajak yang terutang;

Tindakan yang harus diambil dalam rangka perencanaan pajak tersebut adalah usaha untuk melakukan efisiensi beban pajak yang masih dalam ruang lingkup pemajakan, yang tidak melanggar peraturan perpajakan.

- Memaksimalkan laba setelah pajak;

- meminimalkan terjadinya kejutan pajak ( tax surprise ) jika terjadi pemeriksaan pajak oleh fiskus;

- memenuhi kewajiban perpajakan secara benar, efisien dan efektif sesuai dengan ketentuan perpajakan.

Ditulis oleh

Rachel Yolanda Pratiwi S

Read Later Add to Favourites Add to Collection

BAGAIMANA MENURUT ANDA ?

Tinggalkan balasan batalkan balasan.

Alamat email Anda tidak akan dipublikasikan. Ruas yang wajib ditandai *

Simpan nama, email, dan situs web saya pada peramban ini untuk komentar saya berikutnya.

By using this form you agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. *

Kirim Komentar

www.pajak.com © 2024

With social network:

Privacy policy.

To use social login you have to agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website.

Cancel Accept

Forgot password?

Enter your account data and we will send you a link to reset your password.

Nama Pengguna atau Alamat Email

Your password reset link appears to be invalid or expired.

To use social login you have to agree with the storage and handling of your data by this website. %privacy_policy%

Add to Collection

Public collection title

Private collection title

No Collections

Here you'll find all collections you've created before.

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

A key issue in the literature on fiscal federalism is the question of how subnational authorities might best be financed. This complex issue has no easy solutions, given the wide variety of systems actually applied in different countries and at different times in specific countries. Although there is no ideal system of financing state or regional and local governments, because every country faces different problems and different perspectives, some basic objectives may provide broad guidelines on how tax assignment can best be carried out. Tax assignment can hardly be looked at in isolation. It is an issue intimately related to the question of expenditure assignments across different levels of government, which was discussed in detail in Chapter 2. Even a carefully designed system of intergovernmental expenditure allocation will not work satisfactorily unless it is supported by an equally well-thought-out financing system, and vice versa.

A key issue in the literature on fiscal federalism is the question of how subnational authorities might best be financed. This complex issue has no easy solutions, given the wide variety of systems actually applied in different countries and at different times in specific countries. Although there is no ideal system of financing state or regional and local governments, because every country faces different problems and different perspectives, some basic objectives may provide broad guidelines on how tax assignment can best be carried out. Tax assignment can hardly be looked at in isolation. It is an issue intimately related to the question of expenditure assignments across different levels of government, which was discussed in detail in Chapter 2 . Even a carefully designed system of intergovernmental expenditure allocation will not work satisfactorily unless it is supported by an equally well-thought-out financing system, and vice versa.

This chapter focuses on the questions to be addressed when decisions are being made on tax assignment among different levels of government. The term “tax assignment” here describes the level of government responsible for determining the level and rate structure of various taxes, whether their revenue is to be collected or received by that level, or shared with others.

- Tax Assignment and Tax Sharing

The general principles of decentralization must guide the assignment of taxes to different levels of government. According to these principles, as laid out in the traditional local finance literature, regional and local governments should ideally fulfill mainly allocational functions by providing services that accrue primarily to the local population, services whose costs the local constituency bears as far as possible. In the same vein, because of the degree of openness of local economies, the literature on fiscal federalism argues in favor of limiting regional and local government roles in economic stabilization, as well as in distributional policies.

In very broad terms, the assignment of funds to local jurisdictions may in principle follow one of three options. The first, and probably least attractive, option assigns all tax bases to local jurisdictions and then requires them to transfer upward part of the revenue to allow the national government to meet its spending responsibilities. As this option may hinder effective income redistribution across the national territory, as well as the effectiveness of fiscal stabilization, it may not represent the most efficient way of raising public resources and may provide inadequate incentives for the local jurisdictions to participate in the financing of the national economy. This system resembles that previously in force in the former Yugoslavia and is somewhat similar to the system of negotiated tax-sharing previously practiced in Russia. The system previously in force in China, generally recognized to have inhibited the government’s ability to pursue stabilization policies, had analogous features to this extreme model.

A second option, on the other extreme, is to assign all taxing powers to the center, and then finance subcentral governments by grants or other transfers, either by sharing total revenue or by sharing specific taxes. The main disadvantage of this option is that it completely breaks the nexus between the level of tax revenue collected and the decisions to spend that revenue, which constitute the basic prerequisite for a multilevel governmental system that enhances efficiency. Without this connection, the risk is that fiscal illusion will lead to overprovision of local government services. Also, because of the risk of frequent, discretionary cuts in transfers to local levels of governments, this system could also make it difficult to establish a stable system of service provision at the local level. This kind of system bears some resemblance to that once applied in the former Soviet Union and in Hungary. Substantial grant financing of local governments is still practiced in a number of industrial countries, such as France, Italy, and the Netherlands.

The third broad option is the more normal one of assigning some taxing power to the local jurisdictions, if necessary (that is, if vertical imbalances persist) complementing the revenue raised locally with tax-sharing arrangements or other transfers from the central government. This option leads directly to the question of which taxes should be assigned to local jurisdictions and which taxes should remain the responsibility of the national government (the tax assignment problem). By assigning taxes and thus letting the local jurisdictions bear the tax burden at the margin associated with expenditure decisions, the budgetary actions of local governments will be guided by tax-benefit considerations and will in this way improve economic efficiency. 1

The tax assignment problem is typically not an either/or problem with a specific tax placed clearly and solely under the responsibility of either the local, the state, or the central government: rather, in reality (for most taxes) a spectrum of different designs exists ranging from full and complete local autonomy to systems with some local discretion and to others with no local autonomy whatsoever. In other words, even if a specific tax, such as an income tax, has been assigned to the local level because it is found to satisfy the criteria for a “good local tax” (see below), it is possible to design the income tax with varying levels of local revenue autonomy. Table 1 illustrates this important point in a very general way by providing a ranking of different tax designs with respect to the degree of autonomy that they leave with the local governments. For the sake of illustration, the table also includes the main nontax sources of revenues for local governments, although obviously a ranking of this nature can only be broadly indicative.

Fiscal Autonomy in Subcentral Governments

Complete local fiscal autonomy over revenues requires in principle that local governments can change tax rates and set the tax bases. In many countries, however, the central government either defines local tax bases or sets relatively narrow limits to the capacity of local governments to influence the tax base. In some countries (for example, Norway), the central government also sets out limits to the possible variation of local government tax rates.

Taxes assigned to lower levels of government may take the form of own taxes (sometimes referred to as tax separation systems), defined as taxes accruing solely to lower levels of governments, which can determine the rate and, in some cases, also have some autonomy to influence the tax base. An alternative system is represented by overlapping taxes (sometimes called piggybacking systems of local taxation) with the same (or almost the same) tax base for the different levels of government, but with the right of each level of government to set its own tax rate on that common base. This is the system of personal income taxes applied in, for example, the Nordic countries. In Canada, the income tax system used by the provinces involves levying the tax as a percentage of the federal tax revenue accruing within each province. As opposed to tax separation systems, a system of overlapping taxes may involve administrative advantages with regard to assessing the base and to tax collection. This, however, may be at a potential cost of reduced transparency as the tax levied at each level of government may be less easily identifiable for the taxpayers.

Some, in particular federal, countries prescribe in their constitution the system of tax assignment to be applied. Thus, in India, the Constitution prevents overlapping tax powers so that one type of tax can be levied by only one level of government. Likewise, the modalities of local government taxing powers are specified in the Constitutions of Nigeria and Brazil. In Switzerland, the federal government is prohibited by law from imposing indirect taxes, whereas in Australia a similar rule applies for the states.

The question of local fiscal autonomy may be considered almost completely independent from the question of who actually administers and collects the tax. The allocation of these tasks should be determined on the basis of where they can be carried out most efficiently, although one consideration may be that local accountability may be encouraged if the tax is assessed and collected locally.

Probably the single most critical issue in the discussion of subcentral fiscal autonomy, when looked at from the tax side, is whether the authorities concerned can determine their own tax rates. It could be argued that the case for local discretion, as far as the tax base is concerned, should be limited, because changing tax base definitions (for example, by allowing local governments to set individually the amount of a basic allowance, to introduce special tax reliefs, or to exempt specific sources of income or groups of taxpayers) could lead to distortions in the allocation of resources across localities, and also could have important redistributional consequences—an area in which local autonomy is generally believed to be unwarranted. If local governments cannot alter their tax rates, they cannot alter the level of their services in accordance with local preferences. In some countries, subcentral authorities rely mainly on taxes whose rates are fixed by the central government (for example, the countries with extensive tax-sharing arrangements, such as Portugal and Germany) or whose rate is subject to a ceiling. (Norway is a special case in this regard in that all local governments apply the ceiling rate of the local income tax.)

The importance attached to a lack of discretion in local tax policy depends mainly on the role subcentral authorities are supposed to play. To the extent that they are seen mainly as agents, implementing the policies laid down by other tiers of government, their limited autonomy with respect to tax policy would not appear to be serious. In contrast, if they are meant to implement their own expenditure programs and independently set their service levels in accordance with local preferences, their inability to determine tax rates and thus the level of their own revenues is a serious problem owing to the potential conflict between expectations, needs, and wishes of the local population, and the actual revenue potential available to local governments.

The main arguments against providing subcentral authorities with extensive fiscal autonomy center on the risk of increasing economic disparities between areas or localities and alleged restraints on central government macroeconomic control. Administrative simplicity or administrative economies of scale are also used as arguments for centralized taxes with a specific proportion of tax revenues being allocated to subordinate levels of government.

In what follows, the more specific aspects of tax assignment are dealt with by addressing the basic question of which taxes can be considered good candidates for state and local tax sources and which cannot. What characterizes a good local tax?

A Good Local Tax

A good local tax adequately supports a decentralized public expenditure system. The literature on fiscal federalism and local government finance 2 generally suggests that the following criteria and considerations should form the basis for decisions on which taxes can adequately be assigned to the subcentral level and which should remain at the national level.

To the extent that the tax in question is aimed at, and is suitable for, economic stabilization or income redistribution objectives, it should be left to the responsibility of the central government.

The base for taxes assigned to the local level should not be very mobile, otherwise taxpayers will relocate from high to low tax areas, and the freedom of local authorities to vary rates will be constrained. For this reason, general consumption taxes are found at subordinate levels of government only where geographical areas are very large (for example, Canada and the United States). Thus, the more mobile a tax base, the greater the presumption to keep it at the national level.

Tax bases that are very unevenly distributed among jurisdictions should be left to the central government.

Local taxes should be visible, in the sense that it should be clear to local taxpayers what the tax liability is, thereby encouraging local government accountability.

It should not be possible to “export” the tax to nonresidents, thereby weakening the link between payment of the tax and services received.

Local taxes should be able to raise sufficient revenue to avoid large vertical fiscal imbalances. The yield should ideally be buoyant over time and should not be subject to large fluctuations.

Taxes assigned to the local level should be fairly easy to administer or, in other words, the more important economies of scale in tax administration are for a given tax, the stronger the argument for leaving the tax base for that tax to the national level. Economies of scale may depend on data requirements, such as a national taxpayer identification number and computerization.

Taxes and user charges based on the benefit principle can be adequately used at all levels of governments, but are particularly suitable for assignment to the local level, inasmuch as the benefits are “internalized” to the local taxpayers.

This set of broad criteria translates into more specific recommendations regarding which taxes should be assigned to different levels of government, that is, which taxes may be considered good local taxes and which should be left in the domain of the central government. It is generally acknowledged in the literature 3 that the most obvious candidates as good local taxes are land or property taxes and, to some extent, personal income taxes. With some exceptions, turnover or consumption taxes, as well as taxes on capital income, in particular corporate income taxes, are generally considered less appropriate at the local level and in some cases also at the state level 4 because of the mobility of the corresponding tax bases. This broad conclusion derived from principles of local finance seems in very general terms to conform to the financing system actually found in most countries.

The following discussion addresses these questions on a tax-by-tax basis and is intended to cover all the main taxes to which tax assignment is applied in practice (disregarding whether these taxes according to the general principles are considered appropriate at subordinate levels of government or not). The treatment of the different taxes is also intended to be in descending order of importance for subordinate level of governments, although this ordering must necessarily be somewhat subjective (see Tables 2 and 3 ). 5

Distribution of Tax Revenue Among Different Levels of Government

1 Includes supernational authorities’ share of general government total tax revenue for Belgium (1.5 percent), France (0.7 percent), Germany (0.9 percent), the Netherlands (1.4 percent), and the United Kingdom (1.2 percent).

2 Data for general government do not include local government.

Distribution of Different Taxes Within Different Levels of Government

(In percent)

2 There are no state governments in unitary countries.

3 No data on local governments are available.

- Property Taxes

Property taxes, including in particular land taxes, have historically been widely used as subcentral taxes without any special regard to their alleged incidence. This is the outcome of the perceived advantages of the property tax as a local tax. With a property tax it is always clear which authority is entitled to the revenue it yields, which is not always so for income taxes and other taxes. Administration costs are generally found to be lower for a property tax (provided that there is a registry of properties with updated values) than for an income tax, which requires complex tax returns. The yield of a property tax can be predicted more accurately than for an income tax or a profits tax. Finally, some of the tax will be levied on businesses, which seems reasonable to the extent that businesses derive benefits from subcentral services, such as roads and other infrastructure services.

An additional argument for the use of property taxes is that, while almost all residents pay directly or indirectly (through rents) the property tax, thus avoiding free-rider problems in local service provision, this is not always the case for local income taxes. It has also been argued that property taxes are guided by the benefit principle of taxation to the extent that the corresponding spending by local governments benefits local properties by increasing their value. Against this view, it could be held that, although land and existing structures and thus the tax base cannot move in a physical sense, the tax base can do so in a fiscal sense via the capitalization of property taxes to the extent that property taxes are not used for purposes viewed as beneficial to property owners.

The main disadvantage of property taxes lies in the fact that they almost universally realize lower amounts than needed. There are many reasons for this, including the fact that it is a very visible tax (and thus politically unpopular), that it is perceived to have unwanted distributional consequences to the extent that the tax is borne by renters and not by owners of property, and that there are problems associated with the measurement of the tax base, including in particular the “correct” valuation of property, and its updating.

Some countries prefer to distinguish between residential property and commercial and industrial property, with the former being assigned to local taxation, and the latter either to local taxation with a uniform rate or to national taxation only (as is the case in some Nordic countries). In this regard, a particularly contentious issue in many countries (whether industrial, developing, or in transition) has been the taxation of agricultural land. In countries with a general income tax (including income from agriculture), a tax on land could be seen as a discriminatory surcharge on a basic factor input in one sector of the economy, rather than a local benefit tax. In countries without an income tax on agriculture, it has been argued that a land tax on agriculture impedes the development of this important foreign exchange earning sector. Whatever the merits of these arguments may be, the relatively modest tax burden on agriculture found in most countries (which is generally independent of the level of development of the countries in question) seems to reflect the political influence of this sector rather than economic principles or sound fiscal policies.

Other countries apply alternative criteria for the assignment of property taxes to different levels of government. In Brazil, for example, urban property is taxed at the municipal level, while the federal government levies and administers the tax on rural property.

More specifically, at least four important issues relate to the definition and measurement of the base upon which property taxes are levied: the coverage of the base, the use of capital or rental values, the number and nature of exemptions, and the frequency and methods of updating property values. The main issue regarding coverage has been whether land, improvements to land, and buildings should all be subject to tax. The systems applied vary substantially between countries, although most of the countries for which information is available include the unimproved value of land, the value of land improvements, and usually also the value of buildings. The efficiency and equity implications of property taxes have been intensively debated in the literature and will not be pursued further here (see McLure (1977) for an overview of the issues).

In principle, the impact of using rental values or capital values should be the same, assuming well-functioning property and capital markets. It has been argued, however, that there may be major differences in the actual outcome to the extent that rental values reflect mainly the current use of the property, while capital values are said to reflect the value of the property in the best alternative use. Also in this regard, actual methods vary between countries. Capital values are generally based upon market values, although some countries apply corrections to these market values (for example, use a specific proportion of the market value).

Most countries apply a large number of different reliefs under the property tax, for example, in the form of exemption of government property, highways, railways, and other transport or communication facilities, and mining, agriculture, and forestry industries. The subsidies implicit in this kind of treatment, not least with respect to agricultural land, have been increasingly criticized in a number of countries. As indicated above, many countries apply different tax treatment to residential and business property, with residential property usually subject to a more favorable treatment.

A particularly contentious problem in a number of countries has been the frequency and method used to update property values. Thus, in most developing countries, assessment of property values and updating seem to be the major issues. The unpopularity of this type of tax may in some countries be associated with infrequent updates of values, leading to large and abrupt increases in tax liabilities when updating actually takes place. Although property valuations are generally based on market prices, problems are also encountered during certain periods and in areas with modest turnover of property. State and central governments usually perform the valuation of property in order to achieve the necessary coordination between different areas, but the way in which and frequency with which it is done vary substantially across countries.

Although most of the revenue from property taxes generally accrues to subcentral levels of government, state or local governments do not always have complete discretion over the base or the rate. Central governments typically set the rules governing valuations and their frequency and determine exemptions and other reliefs. Also, the central government may impose restrictions on the variations in property tax rates. In practice, local government discretion may be limited in other ways, for example, in the form of earmarking of property revenues, or if higher rates adversely affect grants (as in the United Kingdom before 1989). In Italy, the central government sets a minimum rate for the property tax. If a municipality does not apply the floor rate, transfers to it from the central government are supposed to be reduced correspondingly. Thus, although most of the revenue from property taxes primarily accrues to subcentral authorities in most countries, the respective central governments are generally heavily involved in formulating and administering the provisions of the taxes.

- Personal Income Taxes

Most countries assign all or a large proportion of personal income taxes to the central government. Exceptions include the Scandinavian countries, Switzerland, the Baltic countries, Russia, and the other countries of the former Soviet Union. Generally, there are advantages as well as disadvantages of using personal income taxes at the subcentral level. Among the advantages is the fact that personal income taxes generally are buoyant and thus capable of raising the necessary revenue, and in addition they are believed not to fall on businesses, thereby avoiding the risk of subcentral authorities, anxious to attract new industry, indulging in tax-cutting competitions with adverse effects on services provided.

One of the main disadvantages of a local income tax as the main revenue raiser is the fact that, depending on the level of the tax threshold, many people may not pay the tax, although they receive local services. 6 This could have an adverse impact on the way a decentralized system works and has been used as an argument for supplementing an income tax with other tax sources, thereby including the majority of the local constituency in the local tax net. In this regard, two schools of thought may be distinguished. First, many countries (including, for example, most Mediterranean countries and Austria) seem to place considerable weight on income redistribution and on making income tax systems easy to administer by setting a high tax threshold, thereby excluding a large proportion of the population from the tax net. In contrast, other countries (such as New Zealand, Switzerland, and the Scandinavian countries) generally put more emphasis on the inclusion of most of the population in the tax net by setting relatively low tax thresholds, so that more people share the cost of public services.

In the context of financing local governments, there seems to be a case for making a distinction between schedular and global income taxes, since schedular income taxes can in some cases be used by local jurisdictions without great difficulties, in particular if the taxes on, for example, interest income, dividend income, and wages and salaries are withheld at source and constitute the final tax paid. However, the more developed is a country, the higher is the likelihood that individuals receive income from different sources, and furthermore that these incomes are derived from different jurisdictions. This may move countries to prefer a global income tax system in which the different income sources are added together for each individual and the tax liability is adjusted according to individual circumstances. 7 For such a system to work well at the local level, it requires flows of information on personal income received from other jurisdictions and thus poses the risk of tax evasion. Against this background, it may be better to leave a global income tax base with the national government, which is in a better position to acquire the necessary information.

However, such a system can be combined with revenue sharing, such as is the case in India, where the states receive about 85 percent of total income tax revenue, allocated on the basis of population, tax effort, and a measure of backwardness. In Brazil, 44 percent of the income tax revenue is transferred to lower level governments under a tax-sharing arrangement, and in Poland, in 1992, 15 percent of the personal income tax revenue was shared with local governments. As part of a recent reform of intergovernmental fiscal relations, shared personal income taxes have also been introduced in Hungary (in 1991, 50 percent of the revenue accrued to local governments). Similar tax-sharing arrangements were also important elements in the financing reform in China in 1980 (under the present financing arrangements, local governments receive all of the yields from personal income taxes).

Notwithstanding these considerations, and to the extent that the administrative capabilities are present at the national level, there is a fairly easy and cost-effective way of taxing a global income tax base in local jurisdictions, namely for the local jurisdictions to use the same statutory tax base as for the national income tax (that is, overlapping taxes or piggybacking). This solution, which reduces administrative as well as compliance cost, is actually used in a number of countries (such as, for example, the Nordic countries and Canada, where the provincial tax is levied as a percentage of the federal tax). 8 However, although it introduces an additional complexity to the tax and thus offsets at least in part some of the administrative savings, some of the countries applying this system (for example, the United States) also use specific tax reliefs in their state and local tax systems. Thus, the extent to which countries using overlapping income taxes coordinate the taxes levied at different levels varies considerably. In the Scandinavian countries and Canada, for example, there is a high degree of coordination, while coordination is lacking in Switzerland and the United States.

Generally, because the system requires a fairly advanced administrative system with up-to-date recording of taxpayers’ residence, overlapping personal income taxes are generally seen only in developed countries. Combined with an efficient equalization system, such a system is seen, in the countries that apply it, to ensure that variations in tax rates across jurisdictions reflect similar differences in locally determined service levels. Even in industrial countries, however, the administrative recording requirements have been used as an argument against the workability of local income taxes (which, for example, is the case in the United Kingdom).

A special case of overlapping personal income taxes (or partly overlapping income taxes, if some differences in tax bases are allowed) arises when local income taxes, as in the United States, are deductible from federal income tax liability (deductibility is not applied in the majority of countries using overlapping personal income tax systems). The rationale of such a system is the protection it provides for the taxpayer against excessive aggregate marginal tax rates as a result of high local income taxes. An unwarranted side effect may, however, be the incentive for local governments to expand their expenditures, partly financed—at the margin—by nonresidents. It may also reduce the overall level of progressivity of the tax system.

Taxes on income deriving from the activities of small business establishments or from agriculture may often be imposed as efficiently by local governments as national governments, and in some cases local governments may even possess more information than national governments. However, since record keeping by small establishments is often modest or even absent, taxation of such business income has in many cases to rely on presumptive income, based for example on gross sales, on the floor space in which the activity takes place, or on other criteria (for example, in Hungary, the local business tax is levied on the gross turnover of businesses at a maximum rate of 0.3 percent). Taxes on income from small businesses, from self-employed, and from agriculture, with the revenues accruing mostly or solely to local governments, are well known in a number of Central and Eastern European economies in transition, including Poland and Romania, as well as in a number of developing countries, such as India.

Notwithstanding which level of government actually receives the revenue of personal income taxes, practice differs substantially across countries with regard to which level is responsible for the assessment and for the collection of the income taxes at the subordinate level. National or central government responsibility, or—at the most—state responsibility, seems, however, to be the main rule owing principally to the economies of scale involved in the administration of these taxes.

- Sales Taxes

The popularity of assigning property taxes—and to some degree also income taxes—to subordinate levels of government is attributable in part to the fact that, with these taxes, differences in tax rates between areas are unlikely to cause serious problems owing to the relative immobility of the tax bases. In contrast, different sales tax rates between different jurisdictions can drive consumers (or rather their purchases) away from high tax areas, as is perhaps best reflected in the serious cross-border trade problems between countries with different tax systems and tax levels (such as between Canada and the United States, and between Ireland and the United Kingdom). A distinction must be made, however, between single-stage sales taxes, such as excises and retail taxes, and multistage sales taxes, such as turnover taxes and value-added taxes (VATs).

Retail sales taxes and excises levied on the final sale to the consumer can be given to local jurisdictions as a revenue source, provided that they do not levy these taxes with highly different tax rates. If they do, citizens will be encouraged to shop in other jurisdictions. The main factors determining the extent to which this will take place are the vicinity of other jurisdictions, the cost of travel, and the value of the goods purchased. 9 Another constraining factor for the use of such taxes at the local level with anything but a modest level of tax rates is the risk of tax evasion, which may be relatively more serious for these (single-stage) sales taxes, especially under high tax rates. However, the existence of, for example, both state and municipal sales taxes in many countries must reflect the fact that these caveats are not universally perceived as serious. Thus, in India, the main revenue source of the states is the sales tax. Turnover taxes and some excises are also important provincial revenue sources in Argentina.

A case can be made for distinguishing between excises on goods, which generally should be assigned to the central level to minimize tax exporting, and excises on selected services, consumed locally, and thus much less prone to tax exporting. Some countries, such as India, assign selected excises to the central government (combined with a tax-sharing scheme), and other excises to state and local governments. A number of countries use local excises or special taxes on automobiles or on fuels, which could be regarded as benefit taxes associated with the costs to local governments of maintaining roads. Municipalities in Brazil are allowed to levy a 3 percent tax on retail sales of fuels and gas. In Poland, own sources of revenue for local governments include a tax on automobiles.