Gender Identity Essay

Gender Identity

Review of Literature Sex and gender seems to be the primary focus in trying to determine the identity of transgender. Before any form of cohesion can take place to discuss transgender, the biological aspect must first be noted. Origin identification for each individual is biologically identified as male or female, and at times intersex. "Our gender includes a complex mix of beliefs, behaviors, and characteristics. How do you act, talk, and behave like a woman or man? Are you feminine or masculine

Gender And Gender Identity Disorder

we 're born, our gender identity is no secret. We 're either a boy or a girl. Gender organizes our world into pink or blue. As we grow up, most of us naturally fit into our gender roles. Girls wear dresses and play with dolls. For boys, it 's pants and trucks.” (Goldburg, A.2007) However, for some, this is not the case. Imagine for a moment that you are a two year old boy drawn to the color pink, make up, and skirts. If this is the case than most likely, you are experiencing Gender Dysphoria, otherwise

Gender Dysphoria And Gender Identity

more common to think outside of traditional gender roles and the Western gender binary, more individuals discover that they do not psychologically conform to the genders they are assigned at birth and instead seek to make social and physical transitions that better align with their chosen gender identity. For many, the decision to transition is partly due to gender dysphoria, a feeling of unease in one’s body because it does not match their gender identity. This discomfort can be severe enough to cause

Gender And Identity: What Is Gender Identity?

IS GENDER IDENTITY? Gender identity is ones sense of being a man or a woman. Gender identity is how you feel about and express your gender. Culture determines gender roles and what is masculine and feminine. Gender identity is defined as a personal conception of oneself as male or female (or rarely, both or neither). This concept is intimately related to the concept of gender role, which is defined as the outward manifestations of personality that reflect the gender identity. Gender identity, in

Gender And : Gender Identity Disorder

Gender Dysphoria, formerly known as Gender Identity Disorder, is described by the DSM-IV as a persistent and strong cross-gender identification and a persistent unease with ones sex. However, gender identity is not diagnosed as such if it is comorbid with a physical intersex condition. Gender dysphoria is not to be confused with sexual orientation, as people with gender dysphoria could be attracted to men, women, or both. According to an article written by, Australasian Sciences there are four

The Concept of Gender and Gender Identity

- 10 Works Cited

I am interested in the concept of gender and the deeper meaning of being considered a transgendered person. I feel that a lot of people do not know or care to know about these topics on a more in depth level. People who close their eyes to the idea that a person could be born with the physical aspects of a male yet have the psychological aspects of a female and vice versa, tend to be the ones who say that those people are going against nature or god. Discriminating against people on the principles

Gender And Gender Identity

Social forces that culture poses on gender identity The construction of a self-identity can be a very complex process that every individual is identity is developed through the lenses of cultural influences and how it is expected to given at birth. Through this given identity we are expected to think, speak, and behave in a certain way that fits the mold of societal norms. This paper aims to explain how gender perform gender roles according these cultural values. I intend to analyze the process in

In the 21st century, social formalities in America have been increasingly questioned especially the construct of gender and gender identity. Millennials are pioneering to change gender stigmas and the traditional beliefs of the role of man and woman. This upsurge in breaking gender roles has allowed for a new wave of identity where people aren't satisfied with being boiled down to one textbook definition of masculine or feminine. Across social media platforms such as Instagram where individuals can

Essay Gender Identity

- 6 Works Cited

Gender Identity Gender identity is an extremely relevant topic today. Many people have their own ideas on what is right and what is wrong for each gender to act, and these people are very vocal and opinionated about their ideas. One recent controversial story about gender identity was when a couple refused to tell anybody whether their child named Storm was a boy or a girl. Their oldest child, Jazz, who was originally born male, “always gravitated to dresses, the colour pink and opted for long hair

Gender Identity Society should be more open minded with the topic of gender identity. Our society does not like rapid changes when they are publicly made; there is always a dispute or an opposition against those unexpected changes. The LGBTQIA+ (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex, and asexual) community is the “rapid change” that society finds difficult to deal with. Although, this community has always existed, but it has never been publicly recognized like it is today. Gender Identity

Popular Topics

- Gender Inequalities Essay

- Gender Inequality Essay

- Gender Media Essay

- Gender Roles Essay

- Gender Socialization Essay

- Gender Stereotypes Essay

- Gene Technology Essay

- General Electric Essay

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder Essay

- Generation Essay

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Analysis Author Guidelines

- Analysis Reviews Author Guidelines

- Submission site

- Why Publish with Analysis?

- About Analysis

- About The Analysis Trust

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. introduction, 2. gender identity first, 3. the no connection view, 4. contextualism, 5. pluralism, 6. further and future work.

- < Previous

Recent Work on Gender Identity and Gender

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Rach Cosker-Rowland, Recent Work on Gender Identity and Gender, Analysis , Volume 83, Issue 4, October 2023, Pages 801–820, https://doi.org/10.1093/analys/anad027

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Our gender identity is our sense of ourselves as a woman, a man, as genderqueer or as another gender. Trans people have a gender identity that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth. Some recent work has discussed what it is to have a sense of ourselves as a particular gender, what it is to have a gender identity ( Andler 2017 , Bettcher 2009 , 2017 , Jenkins 2016 , 2018 , McKitrick 2015 ). But beyond the question of how we should understand gender identity is the question of how gender identities relate to genders.

Our gender is the property we have of being a woman, being a man, being non-binary or being another gender. What is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender? According to many people’s conceptions and the standards operative in trans communities, our gender identity always determines our gender. Other people and communities have different views and standards: some hold that our gender is determined by the gender we are socially positioned or classed as, others hold that our gender is determined by whether we have particular biological features, such as the chromosomes we have. If our gender is determined by our gendered social position or whether we have certain biological features, then our gender identity will not determine our gender.

There are several different ways of approaching the question what is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender? We can approach this question as a descriptive or hermeneutical question about our current concepts of gender identity and gender: what is the relationship between our concept of gender identity and our concept of gender? ( Bettcher 2013 , Diaz-Leon 2016 , Laskowski 2020 , McGrath 2021 , Cosker-Rowland forthcoming , Saul 2012 ) Rather than focusing on descriptive questions about our gender concepts, many feminists, such as Sally Haslanger (2000) and Katharine Jenkins (2016) , have proposed ameliorative accounts of the concepts of gender which we should accept; these are gender concepts which they argue that we can use to further the feminist purposes of fights against gender injustice and campaigns for trans rights. We might then ask the ameliorative question, what is the relationship between our gender identity and our gender according to the concepts of gender and gender identity that we should accept? However, some of the most interesting recent work on the relationship between gender identity and gender has focussed on the metaphysical issue of the relationship between being a member of a particular gender kind G (e.g. being a woman) and having gender identity G (e.g. having a female gender identity). As we’ll see, we can answer these different questions in different ways: for instance, we can hold that we should adopt concepts such that someone is a woman iff they have a female gender identity but hold that metaphysically someone is a woman iff they are treated as a woman by their society, that is, iff they are socially positioned as a woman.

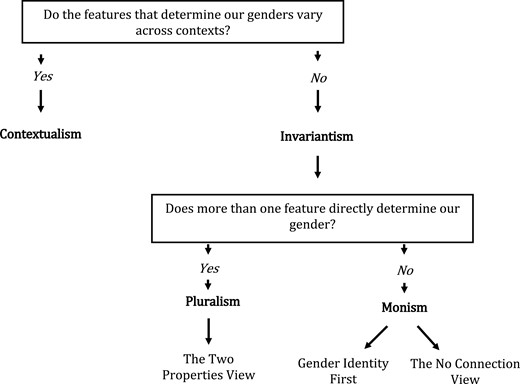

Four positions about the relationship between gender identity and gender that give answers to these ameliorative and metaphysical questions have emerged. This article will explain and evaluate these four positions. In order to understand these different views about the relationship between gender identity and gender it will help to have a little understanding of recent work on gender identity. The two most well-known and popular accounts of gender identity in the analytical philosophy literature are the self-identification account and the norm-relevancy account. On the self-identification account, to have a female gender identity is to self-identify as a woman. One way of explaining what it means to self-identify as a woman is to hold that such self-identification consists in a disposition to assert that one is a woman when asked what gender one is. 1 On the norm-relevancy account, to have a female gender identity is to experience the norms associated with women in your social context (e.g. the norm, women should shave their legs) as relevant to you ( Jenkins 2016 , 2018 ).

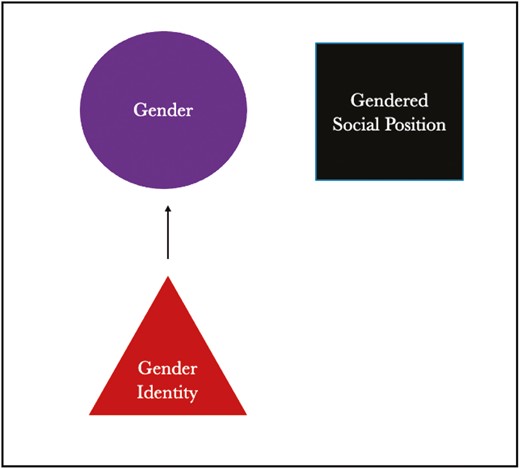

A first view of the relationship between gender and gender identity is what we can call gender identity first . According to a metaphysical version of gender identity first , what it is to be gender G (e.g. a woman) is to have a G gender identity (e.g. to have a female gender identity). Talia Bettcher (2009 : 112), B.R. George and R.A. Briggs (m.s.: §1.3–4), Iskra Fileva (2020 : esp. 193), and Susan Stryker (2006 : 10) argue for gender identity first or views similar to it. And the view that our gender is always determined by our gender identity is, as Briggs and George discuss, part of the standard view in many trans communities and among activists for trans rights. One key virtue of gender identity first is that it ensures that gender is always consensual: on this view, we can be correctly gendered as gender G (e.g. as a woman) only if we identify as a G , and so we can be correctly gendered as a G only if we consent to be gendered as a G by others ( George and Briggs m.s. : §1.3) ( Figure 1 ). 2

Gender identity first

Elizabeth Barnes (2022 : 2) argues that we should reject gender identity first as both a metaphysical and as an ameliorative view. She argues that

(i) Some severely cognitively disabled people do not have gender identities, but

(ii) These severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders and should be categorized as having genders.

And in this case, although having gender identity G is sufficient for being gender G , it is not necessary for being gender G nor necessary for being categorized as a G according to the concepts of gender that we should accept. So, we should reject gender identity first as both a metaphysical view and as an ameliorative view.

Regarding (i), Barnes argues that gender identity

requires awareness of various social norms and roles (and, moreover an awareness of them as gendered), the ability to articulate one’s own relationship to those norms and roles, and so on. But many cognitively disabled people have little or no access to language. Many tend not to understand social norms, much less to identify those norms as specifically gendered. (6)

The norm-relevancy account of gender identity implies that this is true, since on this view having a gender identity involves taking certain gendered social norms to be relevant to you. And the self-identification account also seems to imply that having a gender identity involves having capacities that many severely cognitively disabled people do not have, since self-identification as a particular gender involves a linguistic capacity to say or be disposed to say that one is, or think of oneself as, a particular gender, and many severely cognitively disabled people do not have these capacities.

Barnes has two arguments for

(ii) Severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders.

First, Barnes argues that severely cognitively disabled people who do not have gender identities nonetheless have genders because they suffer gender-based oppression ( 2022 : 11–12). For instance, severely cognitively disabled women are subject to gendered violence and forced sterilization to a greater degree than severely cognitively disabled men. This argument may seem strongest as an argument for (ii) as a metaphysical claim: the view that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders is the best explanation of what we find happening in the world.

Second, Barnes argues that holding that some severely cognitively disabled people do not have genders because they do not have gender identities would involve othering, alienating or dehumanizing these severely cognitively disabled people. Gender identity first implies that agender people do not have genders because their gender identity is that they have no gender. But Barnes argues that gender identity first’s implication that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities lack a gender is more pernicious. Agender people have the capacity to form a gender identity but they opt-out of gender. Gender identity first implies that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities fail to have genders because they do not have the capacity to form a gender identity. So, it implies that they fail to have a gender in the way that tables and animals fail to have a gender – by failing to have the right capacities to have a gender – rather than in the way that agender people do so; for agender people have these capacities. Therefore, Barnes argues, gender identity first others and alienates severely cognitively disabled people from other humans, since all other humans have the capacity to have a gender and having a gender (or opting out of it) is a central part of human (social life). 3 This second argument seems best understood as an argument that we shouldn’t adopt concepts of gender that imply that one is gender G iff one has gender identity G because there are moral and political costs to adopting such concepts.

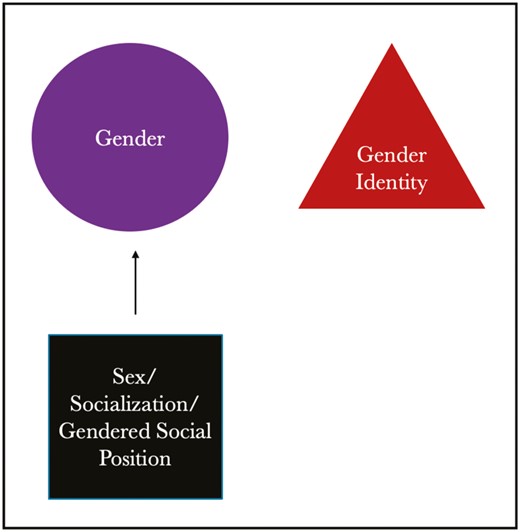

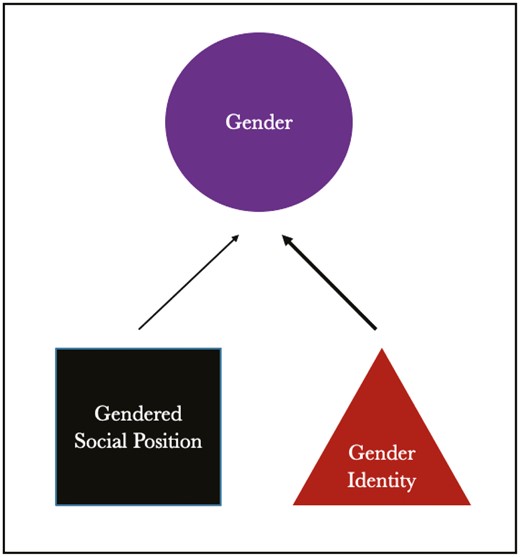

A second account of the relationship between gender identity and gender is the opposite view; this view understands gender identity and gender as entirely disconnected. On this no connection view, the fact that a woman has a sense of herself as a woman is never what makes her a woman; other features of her, such as the way that she is socially positioned, the way she was socialized, or her biological features, make her a woman.

Several accounts of gender imply the no connection view, including Haslanger’s (2000) influential account of gender. Haslanger’s account was originally proposed as an ameliorative account of the concepts of gender that we should adopt rather than as a metaphysical account of gender properties. But in later work Haslanger also endorsed her account of gender as a metaphysical account of gender properties ( 2012 : e.g. 133–134). On Haslanger’s account, to be a woman is to be systematically subordinated because one is observed or imagined to have bodily features that are presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction; on Haslanger’s view, women are sexually marked subordinates. This view of what it is to be a woman implies that one’s being a woman is never determined by one’s female gender identity. Since, whether one has a sense of oneself as a woman, is disposed to assert that one is a woman or takes norms associated with women to be relevant to one, is neither necessary nor sufficient for one to be a sexually marked subordinate.

Although our gender is not directly determined by our gender identity on Haslanger’s account, one’s female gender identity can indirectly lead one to be a woman on Haslanger’s account. For instance, a trans woman’s female gender identity may lead her to take estradiol which will make her have female sex characteristics, which may lead to her being assumed to play a female biological role in reproduction, to be oppressed accordingly, and so to be a woman on Haslanger’s account. In this case, on Haslanger’s account, someone’s female gender identity can indirectly lead to their becoming a woman ( Figure 2 ).

The n o connection view

Other accounts of gender similarly imply the no connection view of the relationship between gender identity and gender. According to Bach’s (2012) account of gender, to be a woman one has to have been socialized as a woman. But one can have a sense of oneself as a woman without having been socialized as a woman and one can be socialized as a woman without forming a sense of oneself as a woman. So, having a female gender identity is neither necessary nor sufficient to be a woman on Bach’s account (although it may be more likely that A will have a sense of themself as a woman if A was socialized as a woman). Biological or sex-based accounts of gender on which our genders are determined by our biological features, such as our chromosomes, also imply the no connection view, since to have a female gender identity is neither necessary nor sufficient for having XX chromosomes. 4

The no connection view implies that many trans women are not women. For instance, Haslanger’s version of this view implies that trans women who are not presumed to have female sex characteristics by those in their society are not women; so trans women who are not recognised as women, or who ‘do not pass’, 5 are not women. This is because such trans women are not observed or imagined to have features that are presumed to be evidence of a female’s biological role in reproduction. There are many such trans women. So, no connection views such as Haslanger’s imply that many trans women are not women ( Jenkins 2016 : 398–402). Some have argued that this is an unacceptable result for a metaphysical view about the relationship between gender identity and gender, either because all trans women are women or because this view would marginalize trans women within contemporary feminism ( Mikkola 2016 : 100–102). These implications are even more problematic for ameliorative no connection views, that is, for views of how gender identity and gender are related according to the concepts that we ought to accept. For we should not adopt gender concepts that imply that we should not classify many trans women as women ( Jenkins 2016 ).

Furthermore, trans communities and trans-inclusive communities ascribe gender entirely on the basis of the gender identities people express or which people are presumed to have. Another problem with the no connection view is that it may seem to imply that there are no genders being tracked or ascribed in these communities ( Jenkins 2016 : 400–401; Ásta 2018 : 73–74).

These problems do not establish that Haslanger’s account of gender should be abandoned entirely. Elizabeth Barnes (2020) has recently argued that we can rescue Haslanger’s account of gender from the problem that it excludes trans women by understanding it as an account of what explains our experiences of gender. According to Barnes’ version of Haslanger’s account, our practices of gendering people, and our gender identities, are the product of Haslangerian social practices of subordinating and privileging people on the basis of perceived sex characteristics. Barnes’ version of Haslanger’s account does not imply that one is a woman iff one is systematically subordinated because one is observed or imagined to have bodily features that are presumed to be evidence of one’s playing a female’s biological role in reproduction. This is because Barnes’ account is only an account of what gives rise to our experiences of gender rather than an account of who has what gender properties or of the gender concepts that we should accept. Barnes might rescue a version of Haslanger’s account from the problem that it excludes trans women. But if she does, she does this by revising Haslanger’s account so that it drops the no connection view of the relationship between gender identities and gender; Barnes’ revised version of Haslanger’s account of gender is instead silent on the issue of the relationship between having gender identity G and being a member of gender G . So, Barnes’ rescue of Haslanger’s account of gender does not rescue the no connection view of the relationship between gender identity and gender.

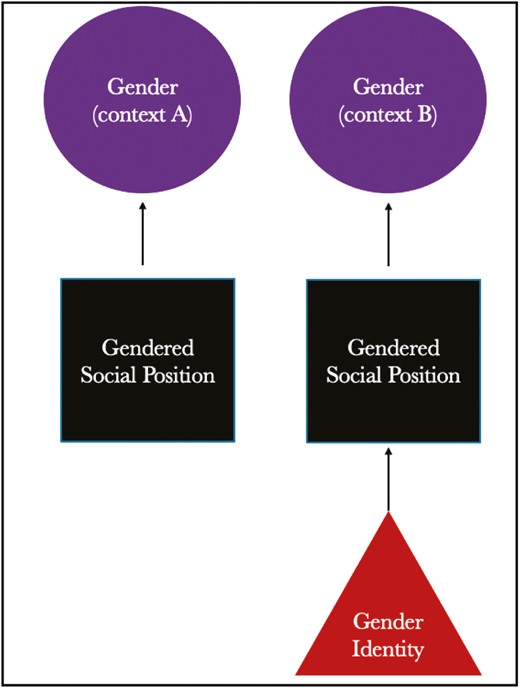

Gender identity first and no connection views such as Haslanger’s are invariantist views of the relationship between gender identity and gender: they hold that the relationship between gender identity and gender does not vary across different contexts. A third account of the relationship between gender identity and gender is the opposite of invariantism, contextualism. According to this view, the features that determine our gender, and so the relationship between gender identity and gender, is different from context to context.

Ásta (2018) and Robin Dembroff (2018) have proposed and/or defended forms of (metaphysical) contextualism. On their views, the gender properties that we have, or the gender kinds that we are members of, are determined by the way that we are treated in particular contexts. We are a member of gender G in virtue of our gender identity G in certain contexts, namely trans-inclusive contexts where people are treated as genders based on their (avowed) gender identities. But in other contexts, we are never a member of gender G in virtue of our gender identity G : in contexts in which people are treated as a gender based on features other than their gender identities – such as traditional or conservative societies – we are not members of genders based on our gender identities. For instance, trans woman Amy is a woman in the context of the support group Trans Leeds – she is a woman (Trans Leeds) – but she is not a women in the context of her conservative parents in Henley who don’t recognize her as a woman and who treat people as women based on the chromosomes that they believe them to have – she is not a woman (family-in-Henley) . And Alex is non-binary in the context of the support group Non-Binary Leeds, where one is conferred a particular gender status based on one’s avowed self-identification – they are non-binary (Non-Binary Leeds) – but Alex is perceived as male in most contexts and is treated as male regardless of their self-identification at school, work and in public, and so Alex is not non-binary in most contexts – e.g. they are not non-binary (Alex’s school) . Importantly, on this view, there is no such thing as being gender G simpliciter , that is, beyond whether one is a G -relative-to-a-certain-context – and the way one is treated or the standards that are operative in that context. So, it is not the case that Alex is non-binary simpliciter or genuinely non-binary; they are merely non-binary relative to one standard or context and not non-binary relative to another.

Contextualism can explain why the way that some people are gendered varies from context to context: in explaining her contextualist view, Ásta (2018 : 73–74) gives an example of a coder who is one of the guys at work, neither a guy nor a girl at the bars they go to after work, and one of the women – and expected to help out like all the other women – at their grandmother’s house (85–86). Contextualism also allows us to explain how sometimes people are gendered on the basis of their perceived biological features and sometimes gendered based on their avowed (or assumed) gender identities. Dembroff argues that a contextualist view is particularly useful in explaining how, in many societies and contexts, trans people are unjustly constrained, or as they put it ‘ontologically oppressed’, by being constructed and categorized as a member of a category with which they do not identify; identifying such ontological oppression is essential to explaining the oppression that trans people face ( Dembroff 2018 : 24–26, Jenkins 2020 ) ( Figure 3 ).

Contextualism

However, there are several problems with contextualism. One problem is that it implies that gender critical feminists are, in a sense, right when they claim that trans women are not women and trans men are not men because trans women are not women according to the standards of many people and of many places: in many places trans women, for instance, are not treated as women, and in many places trans women are not women relative to the dominant standard for who is a woman, which is sex-based or biology-based. So, for instance, when in 2021 the then Tory UK Health Secretary Sajid Javid said that ‘only women have cervixes’, according to contextualism, what he said was true in a sense: only women (dominant UK-standards) have cervixes; and only women (Tory party conference) have cervixes. Even though it is false that only women (Trans Leeds) have cervixes because trans men have cervixes. This conclusion may seem problematic and paralyzing because it implies that Javid’s claim is true in a sense in certain contexts, and we cannot truthfully claim that it is just plain false ( Saul 2012 : 209–210, Diaz-Leon 2016 : 247–248). 6

Ásta (2018 : e.g. 87–88) and Dembroff (2018) argue that we can solve this problem by holding that, although it is true that trans men are not men relative to most dominant UK contexts, we should still treat and classify trans men as men. We should classify trans men as men because facts about how we should classify someone – the gender properties that we should treat them as having – are established by moral and political considerations. But although we should classify trans men as men, they are not – as a matter of social metaphysical fact – men (dominant UK contexts) . So, we should accept contextualism as a metaphysical view about the relationship between gender identity and gender but not as an ameliorative view about the gender concepts we should accept; we can call this combination of views purely metaphysical contextualism.

Dembroff (2018 : 38–48) recognizes that purely metaphysical contextualism may seem to have problematic implications. It may seem to imply that many trans women (for instance) are mistaken when they say that they are women in many contexts, such as dominant UK and US contexts, where there are chromosomes-based or assigned-sex-at-birth-based gender standards. Yet Dembroff argues that purely metaphysical contextualism does not have this problematic implication because trans women are women relative to the gender kinds operative in trans-inclusive contexts.

However, this will not always be a helpful form of correctness. Suppose that Alicia is a trans woman in London in 1840. There are no trans-inclusive societies, communities or contexts that she knows of. But she takes herself to be a woman, and suppose that according to both of the accounts of gender identity that we discussed in §1, Alicia has a female gender identity. We can say that Alicia’s judgement that she is a woman is correct in the sense that it is correct-relative to the gender kinds operative in future contexts and fictional contexts. But any judgment that we might make is true relative to the standards in some future or merely possible context. And we might wonder why it matters that someone’s judgment about their own gender is true relative to the standards operative in some future context that they could not possibly be aware of. This form of truth is not what they want and it’s hard to see why it should be relevant in this context. Furthermore, trans people are widely held to be misguided, mentally unstable, suffering from a delusion or making believe ( Bettcher 2007 , Serano 2016 : ch. 2, Lopez 2018 , Rajunov and Duane 2019 : xxiv). If the only interesting way in which Alicia is correct about her gender is that she is that gender according to standards far in the future that she is not aware of, then it would seem that Alicia is misguided about her gender – given that she could not know about these standards – and that she is in a sense making believe. This seems like an undesirable consequence, especially if we think that Alicia is really a woman, that is, that she is not misguided.

There are two further, more general, problems for contextualism. 7 First, contextualism seems to clash with how many of us think about our own and others’ genders. For instance, many trans men think that they should be classified as men because they are men, and not just because they are men-relative to the standards of trans-inclusive communities and societies ( Saul 2012 : 209–210). 8 Gender critical feminists think that trans women are not women, that standards which align with this view track the standard-independent truth, and standards which don’t align with this view do not.

Second, contextualism seems to be in tension with the idea that many of our disagreements about gender are genuine disagreements. Suppose that contextualism is true and that we (and everyone else) accept it. In this case, it is hard for us to sincerely genuinely disagree with Javid about whether only women have cervixes. Since, when he says that only women have cervixes we know that he means that only those who count as women, relative to the dominant UK standards or relative to the standards operative amongst Tory MPs and members, have cervixes. And we agree with him about this, since we know that according to these standards trans men are women. So, if contextualism is true and we accept it, it is hard for us to genuinely disagree with Javid. Contextualism could be true without our knowing or believing it. In this case, we could genuinely disagree with Javid. But our disagreement here would only be possible because we are significantly mistaken about what kinds of things gender kinds are; we think gender kinds are not all context- or standard-relative but in fact they are. And attributing such a significant mistake to all of us is a significant cost of a metaphysical theory, for other things equal we should accept more charitable theories that do not imply that we are significantly mistaken rather than theories that do imply this ( Olson 2011 : 73–77, McGrath 2021 : 35, 46–48).

These problems with contextualism about the relationship between gender identity and gender are analogues of problems that contextualist views face in other domains such as in metaethics. According to metaethical contextualism, moral claims, their meanings and their truth are always standard-relative. There is no such thing as an act being morally wrong, only its being morally-wrong-relative-to-utilitarianism or morally-wrong-relative-to-the-standards-of-Victorian-England. But metaethical contextualism faces a problem explaining fundamental moral disagreement. Act-utilitarians and Kantians agree that pushing the heavy man off of the bridge in the footbridge trolley case is wrong (Kantianism) and right (act-utilitarianism) but they still disagree and they take themselves to be disagreeing about which of their moral standards is correct, and which standard tracks the truth about which actions are right and wrong simpliciter ( Olson 2011 : 73–77, Cosker-Rowland 2022 : 57–59). If there are no non-context- or standard-relative properties of right and wrong, then although Kantians and Utilitarians do disagree – they think there are such properties – there is in fact nothing for them to disagree about. So, metaethical contextualism seems to be committed to a kind of error theory about morality that, other things equal, we should avoid: Kantians and Utilitarians think that they are talking about which of their moral standards is independently correct, but there is no such standard-independent moral correctness. Contextualists in metaethics have developed several types of resources to mitigate this kind of problem or to enable contextualism to explain what’s happening in these disagreements better. Perhaps these proposals could be used to mitigate the analogous problems with contextualism about the relationship between gender identity and gender. McGrath (2021 : esp. 42–49) considers this possibility and argues that these responses are not plausible, and that they face similar problems to the problems faced by the analogous responses proposed by contextualists in metaethics. 9 More broadly, whether contextualists’ proposals to mitigate these problems for metaethical contextualism do, or could, succeed is contested ( Cosker-Rowland 2022 : 59–64). 10

Contextualism holds that the features that determine our gender vary from context to context and so whether our gender identity determines our gender varies from context to context. Invariantist views such as gender identity first and the no connection view hold that one feature (e.g. gender identity or whether one is a sexually marked subordinate) determines our gender in every context. But we need not adopt such a monist invariantist view; we can instead adopt a pluralist invariantist view that holds that multiple features are relevant to, or determine, our genders across different contexts ( Figure 4 ). A version of pluralism that has been proposed is what we can call the two properties view. According to the two properties view, two and only two properties determine our gender in all contexts: our gender identity and our gendered social position or class. Gender identity first and Haslanger’s no connection view hold that one of these two properties determines our gender in every context; the two properties view holds that both of these properties can make us a particular gender in every context. 11

Views of the relationship between gender identity and gender

Katharine Jenkins (2016) proposes an ameliorative version of the two properties view. She proposes that we accept gender concepts according to which there are two senses of woman . In one sense of woman , to be a woman is to have a female gender identity; in another second sense, to be a woman is to be socially classed as a woman, which we can understand in terms of Haslanger’s account: to be a woman in this second sense is to be a sexually marked subordinate. Jenkins argues that if we accept gender concepts according to which there are two senses of ‘woman’, we do not objectionably exclude trans women, since trans women who are not socially classed as women do have female gender identities and so are still women on this view. So, Jenkins argues that we should accept gender concepts such that A is a woman iff A is socially classed as a woman or has a female gender identity. She then argues that, although we should accept gender concepts on which there are two senses of gender, we should, at least primarily, use ‘woman’ to refer to people with a female gender identity rather than those who are classed as women.

Jenkins’ two properties view avoids the problems with the ameliorative gender identity first and no connection views. It does not imply that severely cognitively disabled women are not women and it does not imply that trans women are not women. Yet if we adopt a concept of ‘woman’ with two senses but use ‘woman’ to refer to people with female gender identities, it still seems that we adopt concepts according to which trans women who are not socially classed as women are not women in an important sense. We may want to avoid this consequence with our ameliorative proposals, since trans women want to be thought of as women, and many trans women want to be thought of as in no way men, rather than merely being referred to as women rather than men (see e.g. Wynn 2018 ). We might also worry that adoption of Jenkins’ view would create a hierarchy of women on which someone who is a woman in both senses is more of a woman than someone who is a woman in only one sense: we might worry that if such concepts of gender were adopted, a trans woman who does not have her womanhood socially recognized would be seen as less of a woman than a trans woman who is socially positioned as a woman. 12

Elizabeth Barnes (2022 : 24–25) briefly articulates a similar metaphysical two properties view. On this view, there are two different properties that one can have that can make it the case that one is gender G : the property of being socially classed as a G and the property of having gender identity G . And the relevant gender identity property takes priority when A is socially classed as a G1 (e.g. as a man) but has gender identity G2 (e.g. a female gender identity): in such a case A is a G2 (a woman) rather than a G1 (a man) ( Figure 5 ).

The two properties view

However, the two properties view needs to explain why our gender identities take precedence over our gendered social position in determining our gender when the two conflict. Without further supplementation the metaphysical two property view does not do this; it does not explain why A is a man when A has a male gender identity but is socially positioned as a woman. If the two properties view does not explain this, it has an explanatory deficiency, and this deficiency gives us reason to accept competing views that do not face this explanatory problem over the two properties view.

One natural way to supplement the two properties view to try to solve this explanatory problem is to hold that moral and political considerations determine that gender identity takes priority over gender class when they conflict. 13 . First, it is controverisal that there is moral encroachment on gender metaphysics, that what's morally best makes a difference to what gender we metaphysically are. For instance, Ásta (2018) , Dembroff (2018) and Jenkins (2020) argue that morality does not encroach on gender metaphysics in this way.

Second, we can think of this as the moral encroachment explanation. However, moral encroachment does not look like a plausible explanation of how, metaphysically, gender identity takes priority over gendered social position in determining our genders. To see this, suppose that Alexa understands herself to be a woman and is treated by those around her as a woman. An evil demon will kill 2000 members of Alexa’s community unless we hold that Alexa is a man, treat Alexa as, think of Alexa as, and assert that Alexa is a man for the next hour. In this case, moral and political considerations establish that we morally ought to treat Alexa as a man for the next hour, but this doesn’t mean that Alexa is in fact a man. 14

It might seem that a nearby view on which moral and political considerations play a smaller role is more plausible. On this view, moral and political considerations only come in to determine whether, metaphysically, A is a member of gender G1 or of gender G2 when A is socially classed as a G1 but has identity G2 . But this view would also generate counterintuitive results. To see this, suppose that Beth has a female gender identity and she was assigned female at birth, but she is socially classed as a man – she doesn’t resist this because of the strong economic advantages she receives, which outweigh the discomfort she feels by being constantly misgendered. Now suppose that an eccentric, very powerful and malevolent millionaire brings these facts to light but will torture everyone in our society unless we continue to classify, think of and refer to Beth as a man. In this case, plausibly, moral and political considerations establish that we should classify Beth as a man, but these facts do not seem to bear on whether Beth is a man or a woman; intuitively Beth is a woman, and intuitively the fact that morally we should think of, treat, and classify Beth as a man does not make it the case that Beth is a man – and really has nothing to do with Beth’s gender in this case. So, if moral and political considerations play this more limited role in determining our genders, they still sometimes generate the wrong result because there are cases in which the social and political considerations side with someone’s gendered social position rather than their gender identity, but in which this does not seem to be relevant to, or establish that, their gender lines up with their gendered social position. So, the moral encroachment explanation does not seem to solve the explanatory problem for the two properties view. 15

These evil millionaire cases may be too fantastical for some. But the same point can be made with real world examples too. Norah Vincent (2006) disguised herself as a man for 18 months so that she could investigate men and their experiences. She became socially positioned as, and treated by others as, a man. While she was effectively disguised as a man, moral and political considerations seem to have established that everyone should treat her as a man: those who didn’t know her real gender had an obligation to take her assertions that she was a man as genuine and those who did know her real gender had an obligation not to blow her cover. But although everyone ought to have treated Vincent as a man, she was not a man: she did not identify as a man at the time, nor prior or subsequent to her journalistic project. Moral and political considerations favoured treating Vincent in line with her social position as a man rather than in line with her female gender identity. But these factors do not establish that she was a man rather than a woman. So, the moral encroachment explanation generates the wrong results in this case too.

One way to respond to this problem for the two properties view is to drop the view that gender identity takes priority. But this would be problematic for then trans women who are socially positioned as men would be both men and women on this view – and not just people with female gender identities who are socially positioned as men. This is implausible. This view is also different from contextualism since contextualism holds that such trans women are women-relative-to-the-standards-of-trans-inclusive-contexts and men-relative-to-other-contexts; a version of the two properties view that drops the priority of gender identity holds that such trans women are both men and women tout court .

In this paper I’ve discussed metaphysical and ameliorative inquiries into the relationship between gender identity and gender. I’ve discussed four different views about this relationship. All four views face problematic objections. Gender identity first seems to objectionably exclude some severely cognitively disabled people from having genders. No connection views seem to be objectionably trans exclusionary. Contextualism seems to be in tension with how we think about gender and implies that trans people are not the genders that line up with their gender identities in many contexts; despite contextualists’ best efforts, these implications still seem problematic. Pluralist views struggle to plausibly explain how their plurality of features interact when they conflict to determine our genders.

One avenue of future research involves examining the extent to which these objections really undermine these different views. For instance, we might question whether Barnes really shows that we should reject gender identity first. Barnes has two arguments for the view that, contra gender identity first, severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities have genders.

The first argument was that, if we reject this view, we cannot explain the gendered oppression that severely cognitively disabled women face. But we might wonder whether this is really true. All we need in order to explain the oppression that severely cognitively disabled women face is the claim that they are socially treated or understood to be women. But we can be socially treated or understood to be a gender other than the gender we are: e.g. many non-binary people who were assigned female at birth (AFAB) are discriminated against because they are understood to be women even though they are not women. We might think that we should explain the gendered oppression that AFAB severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities face and the gendered discrimination that AFAB non-binary people face in the same way: we should say that although they are not women, they are assumed to be women and are treated as women and this is why they face this gendered oppression. Barnes’ second argument was that the view that severely cognitively disabled people without gender identities do not have genders others and alienates these severely cognitively disabled people. However, we might wonder whether this is necessarily true. Perhaps we should think of the capacity to have a gender as inessential to human personhood just as we think of the capacity for membership in other categories as something that is not required for personhood: perhaps we should think that just as some severely cognitively disabled people lack the cognitive capacities to identify as a Christian or as a punk, and so are not Christians or punks, they similarly lack the capacities to identify as a woman and so are not women. If gender need not be central to human life, as religion (or music) need not be, perhaps we might reasonably claim to not other anyone by holding that they could not have a gender.

A second avenue of further work concerns genders beyond the gender category woman . Most of the work on the relationship between gender identity and gender has concerned the relationship between being a woman and having a female gender identity. But views about this may not straightforwardly generalize to provide plausible accounts of other genders such as genderqueer and other non-binary genders. 16 In one of the few published articles in analytic philosophy discussing genders beyond the gender binary, Dembroff (2020) argues that non-binary and genderqueer are critical gender kinds, which should be understood as kinds, membership in which constitutively involves engagement in the collective destabilization of dominant gender ideology. One way to destablize dominant gender ideology is to destabilize the idea that there are two mutually exclusive genders. Such destabilization of the binary gender axis can involve using gender neutral pronouns, cultivating gender non-conforming aesthetics, asserting one’s non-binary gender categorization, queering personal relationships, eschewing sexual binaries and/or switching between male and female coded spaces. Dembroff argues that to be genderqueer is ‘to have a felt or desired gender categorization that conflicts with the binary [gender] axis, and on that basis collectively destabilize this axis’ ( 2020 : 16). This understanding of the category genderqueer does not quite fit into the typology that I’ve explained in this article. For, on this account, a particular kind of non-binary gender identity is necessary but not sufficient for membership in the kind genderqueer .

There are issues with this account. For instance, Matthew Cull (2020 : 162) argues that this account misgenders agender people because many agender people have a felt or desired gender categorization that conflicts with the binary gender axis and are engaged in the collective destabilization of the gender binary but are not genderqueer; they are agender. 17 However, in general, more work is needed on gender kinds beyond the gender binary. This work may also provide new avenues for conceptualizing and/or complicating the relationship between gender identity and gender more generally. 18

See Bettcher (2009) ( 2017 : 396) and Jenkins (2018 : 727). cf. Barnes (2020 : 709).

See also Bornstein (1994 : 111, 123–124).

On the centrality of gender for social life see Witt 2011 .

See Bryne (2020) and Stock (2021 : ch. 2, ch. 6).

There are problems with using this terminology of passing. For instance, we typically think of A as passing as an F only if they are not an F . But if all trans women are women, then there are no ‘non-passing’ trans women. For discussion of issues with the concept of passing see e.g. Serano 2016 : 176–180.

Many gender critical feminists will want to reject contextualism for a similar but opposite reason: they believe that there is no sense in which Javid is mistaken, but contextualism implies that there is a sense in which he is mistaken.

For problems along these lines see McGrath 2021 : esp. 42–49.

Cf. Bettcher 2013 : esp. 242–243.

Cf. Dembroff 2018 : 44–45.

According to Jenkins’ (2023) ontological pluralism, there are a plurality of gender properties. For instance, there is the property of being a woman in the sense of having a female gender identity, and the property of being socially positioned as a woman in a particular context, but there is no further property of being a woman. Ontological pluralism about gender properties is a slightly different view about gender properties from the social position account of gender properties that Ásta and Dembroff propose; see Bettcher 2013 and Jenkins 2023. But ontological pluralism similarly implies that being a woman (social position) is not determined by one’s gender identity but being a woman (gender identity) is; and that there is no such thing as being a woman tout court beyond such a plurality of more specific gender properties. Since it has similar implications about the relationship between gender identity and gender to Ásta and Dembroff's views, it faces similar problems.

Other work on the metaphysics of gender, such as Stoljar’s (1995) nominalism or a view similar to it, could also be understood as a form of pluralist invariantism; although cf. Stoljar 1995 : 283 and Mikkola 2016 : 70.

Cf. Mikkola 2019 : §3.1.2 and Jenkins 2016 : 418–419.

Cf. Jenkins 2016 : 417–418 and Diaz-Leon 2016 .

Cases like this may also cause problems for Ásta’s and Dembroff’s social position accounts of gender.

Heather Logue suggested to me that a more specific form of moral encroachment might solve this problem: our autonomy might establish that our gender identities trump our gendered social positions when they conflict, without establishing that Beth is a man. However, we can imagine a version of this case in which Beth autonomously chooses to waive her right to be treated in line with her gender identity. In such a case Beth is still not a man.

We may also wonder whether this work will generalize to the category man given that human beings are still by default understood to be men in many contexts.

Another worry is that analogous accounts of the kind non-binary will either: (a) make the conditions for engagement in collective resistance too onerous and thereby exclude non-binary people who are not able to engage in this resistance due to oppressive circumstances; or (b) make these conditions too easy to satisfy, in which case it is unclear what work engagement in collective resistance is doing in this account; that is, it is unclear why we should prefer an account of the kind non-binary like this to a gender identity first account of the category non-binary . For work relevant to (a), arguing that trans people in the past who could not express their gender identities or resist the binary gender axis due to hostile circumstances may still be correctly considered to be trans, see Heyam 2022 : ch. 1.

I am grateful to a reviewer, who revealed themself to be Ray Briggs, for wonderful extremely thorough comments on a previous draft of this paper. I would also like to thank an audience of my colleagues at the University of Leeds for comments, thoughts and objections that shaped the final version of this paper.

Andler , M.S. 2017 . Gender identity and exclusion: a reply to Jenkins . Ethics 127 : 883 – 95 .

Google Scholar

Ásta . 2018 . The Categories We Live By . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Google Preview

Bach , T. 2012 . Gender is a natural kind with a historical essence . Ethics 122 : 231 – 72 .

Barnes , E. 2020 . Gender and gender terms . Noûs 54 : 704 – 30 .

Barnes , E. 2022 . Gender without gender identity: the case of cognitive disability . Mind Online First: 1 – 28 .

Bettcher , T.M. 2007 . Evil deceivers and make-believers: on transphobic violence and the politics of illusion . Hypatia 22 : 43 – 65 .

Bettcher , T.M. 2009 . Trans identities and first-person authority . In You’ve Changed: Sex Reassignment and Personal Identity , ed. L. Shrage . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Bettcher , T.M. 2013 . Trans women and the meaning of ‘women’ . In Philosophy of Sex: Contemporary Readings , 6th edn., eds. A. Soble , N. Power , and R. Halwani . London : Rowman and Littlefield .

Bettcher , T.M. 2017 . Through the looking glass: trans theory meets feminist philosophy . In The Routledge Companion to Feminist Philosophy , eds. A. Garry , S. Khader , and A. Stone . London : Routledge .

Bornstein , K. 1994 . Gender Outlaw. New York, NY : Routledge .

Byrne , A. 2020 . Are women adult human females ? Philosophical Studies 177 : 3783 – 803 .

Cosker-Rowland , R. 2022 . Moral Disagreement . London : Routledge .

Cosker-Rowland , R. forthcoming . The normativity of gender . Noûs .

Cull , M. 2020 . Engineering Genders: Pluralism, Trans Identities, and Feminist Philosophy . PhD thesis, University of Sheffield .

Dembroff , R. 2018 . Real talk on the metaphysics of gender . Philosophical Topics 46 : 21 – 50 .

Dembroff , R. 2020 . Beyond binary: genderqueer as critical gender kind . Philosophers’ Imprint 20 : 1 – 23 .

Diaz-Leon , E. 2016 . Woman as a politically significant term: a solution to the puzzle . Hypatia 31 : 245 – 58 .

Fileva , I. 2020 . The gender puzzles . European Journal of Philosophy 29 : 182 – 98 .

George , B.R. and R.A. Briggs . m.s. Science fiction double feature: trans liberation on twin Earth . Unpublished manuscript. https://philpapers.org/archive/GEOSFD.pdf .

Haslanger , S. 2000 . Gender and race: (what) are they? (What) do we want them to be ? Noûs 34 : 31 – 55 .

Haslanger , S. 2012 . Resisting Reality . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Heyam , K. 2022 . Before We Were Trans . London : Basic Books .

Jenkins , K. 2016 . Amelioration and inclusion: gender identity and the concept of woman . Ethics 126 : 394 – 421 .

Jenkins , K. 2018 . Toward an account of gender identity . Ergo 5 : 713 – 44 .

Jenkins , K. 2020 . Ontic injustice . Journal of the American Philosophical Association 6 : 188 – 205 .

Jenkins , K. 2023 . Ontology and Oppression . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Laskowski , N.G. 2020 . Moral constraints on gender concepts . Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 23 : 39 – 51 .

Lopez , G. 2018 . Transgender people: 10 common myths . Vox.com . < https://www.vox.com/identities/2016/5/13/17938120/transgender-people-mental-illness-health-care >, last accessed 14 November 2018 .

McGrath , S. 2021 . The metaethics of gender . In Oxford Studies in Metaethics , vol. 16 , ed. R. Shafer-Landau . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

McKitrick , J. 2015 . A dispositional account of gender . Philosophical Studies 172 : 2575 – 89 .

Mikkola , M. 2016 . The Wrong of Injustice: Dehumanization and its Role in Feminist Philosophy . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Mikkola , M. 2019 . Feminist perspectives on sex and gender . In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy , ed. E.N. Zalta . Fall 2019 edition. < https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2019/entries/feminism-gender/ >.

Olson , J. 2011 . In defense of moral error theory . In New Waves in Metaethics , ed. M. Brady . Basingstoke : Palgrave .

Rajunov , M. and S. Duane . 2019 . Introduction . In Nonbinary: Memoirs of Gender Identity , eds. M. Rajunov and S. Duane . New York, NY : Columbia University Press .

Saul , J. 2012 . Politically significant terms and philosophy of language: methodological issues . In Out from the Shadows: Analytical Feminist Contributions to Traditional Philosophy , eds. S. Crasnow and A. Superson . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Serano , J. 2016 . Whipping Girl: A Transsexual Woman on Sexism and the Scapegoating of Femininity , 2nd ed. Berkeley, CA : Seal Press .

Stock , K. 2021 . Material Girls . London : Fleet .

Stoljar , N. 1995 . Essence, identity, and the concept of woman . Philosophical Topics 23 : 261 – 93 .

Stryker , S. 2006 . ( De)subjugated knowledges: an introduction to transgender studies . In The Transgender Studies Reader , eds. S. Stryker and S. Whittle . New York, NY : Routledge .

Vincent , N. 2006 . Self-Made Man . New York, NY : Viking .

Witt , C. 2011 . The Metaphysics of Gender . Oxford : Oxford University Press .

Wynn , N. 2018 . Pronouns . Contrapoints 31 : 55 . < https://youtu.be/9bbINLWtMKI >.

Email alerts

Companion article, citing articles via.

- Author Guidelines

- Contact Analysis Trust

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1467-8284

- Print ISSN 0003-2638

- Copyright © 2024 The Analysis Trust

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Understanding Gender, Sex, and Gender Identity

It's more important than ever to use this terminology correctly..

Posted February 27, 2021 | Reviewed by Kaja Perina

- The Fundamentals of Sex

- Find a sex therapist near me

Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene hung a sign outside her Capitol office door that said “There are TWO genders: MALE & FEMALE. ‘Trust the Science!’” There are many reasons to question hanging such a sign, but given that Rep. Taylor Greene invoked science in making her assertion, I thought it might be helpful to clarify by citing some actual science. Put simply, from a scientific standpoint, Rep. Taylor Greene’s statement is patently wrong. It perpetuates a common error by conflating gender with sex . Allow me to explain how psychologists scientifically operationalize these terms.

According to the American Psychological Association (APA, 2012), sex is rooted in biology. A person’s sex is determined using observable biological criteria such as sex chromosomes, gonads, internal reproductive organs, and external genitalia (APA, 2012). Most people are classified as being either biologically male or female, although the term intersex is reserved for those with atypical combinations of biological features (APA, 2012).

Gender is related to but distinctly different from sex; it is rooted in culture, not biology. The APA (2012) defines gender as “the attitudes, feelings, and behaviors that a given culture associates with a person’s biological sex” (p. 11). Gender conformity occurs when people abide by culturally-derived gender roles (APA, 2012). Resisting gender roles (i.e., gender nonconformity ) can have significant social consequences—pro and con, depending on circumstances.

Gender identity refers to how one understands and experiences one’s own gender. It involves a person’s psychological sense of being male, female, or neither (APA, 2012). Those who identify as transgender feel that their gender identity doesn’t match their biological sex or the gender they were assigned at birth; in some cases they don’t feel they fit into into either the male or female gender categories (APA, 2012; Moleiro & Pinto, 2015). How people live out their gender identities in everyday life (in terms of how they dress, behave, and express themselves) constitutes their gender expression (APA, 2012; Drescher, 2014).

“Male” and “female” are the most common gender identities in Western culture; they form a dualistic way of thinking about gender that often informs the identity options that people feel are available to them (Prentice & Carranza, 2002). Anyone, regardless of biological sex, can closely adhere to culturally-constructed notions of “maleness” or “femaleness” by dressing, talking, and taking interest in activities stereotypically associated with traditional male or female gender identities. However, many people think “outside the box” when it comes to gender, constructing identities for themselves that move beyond the male-female binary. For examples, explore lists of famous “gender benders” from Oxygen , Vogue , More , and The Cut (not to mention Mr. and Mrs. Potato Head , whose evolving gender identities made headlines this week).

Whether society approves of these identities or not, the science on whether there are more than two genders is clear; there are as many possible gender identities as there are people psychologically forming identities. Rep. Taylor Greene’s insistence that there are just two genders merely reflects Western culture’s longstanding tradition of only recognizing “male” and “female” gender identities as “normal.” However, if we are to “trust the science” (as Rep. Taylor Greene’s recommends), then the first thing we need to do is stop mixing up biological sex and gender identity. The former may be constrained by biology, but the latter is only constrained by our imaginations.

American Psychological Association. (2012). Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. American Psychologist , 67 (1), 10-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024659

Drescher, J. (2014). Treatment of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patients. In R. E. Hales, S. C. Yudofsky, & L. W. Roberts (Eds.), The American Psychiatric Publishing textbook of psychiatry (6th ed., pp. 1293-1318). American Psychiatric Publishing.

Moleiro, C., & Pinto, N. (2015). Sexual orientation and gender identity: Review of concepts, controversies and their relation to psychopathology classification systems. Frontiers in Psychology , 6 .

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don't have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 26 (4), 269-281. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066

Jonathan D. Raskin, Ph.D. , is a professor of psychology and counselor education at the State University of New York at New Paltz.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Pride Month

A guide to gender identity terms.

Laurel Wamsley

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity." Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara, a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

Issues of equality and acceptance of transgender and nonbinary people — along with challenges to their rights — have become a major topic in the headlines. These issues can involve words and ideas and identities that are new to some.

That's why we've put together a glossary of terms relating to gender identity. Our goal is to help people communicate accurately and respectfully with one another.

Proper use of gender identity terms, including pronouns, is a crucial way to signal courtesy and acceptance. Alex Schmider , associate director of transgender representation at GLAAD, compares using someone's correct pronouns to pronouncing their name correctly – "a way of respecting them and referring to them in a way that's consistent and true to who they are."

Glossary of gender identity terms

This guide was created with help from GLAAD . We also referenced resources from the National Center for Transgender Equality , the Trans Journalists Association , NLGJA: The Association of LGBTQ Journalists , Human Rights Campaign , InterAct and the American Psychological Association . This guide is not exhaustive, and is Western and U.S.-centric. Other cultures may use different labels and have other conceptions of gender.

One thing to note: Language changes. Some of the terms now in common usage are different from those used in the past to describe similar ideas, identities and experiences. Some people may continue to use terms that are less commonly used now to describe themselves, and some people may use different terms entirely. What's important is recognizing and respecting people as individuals.

Jump to a term: Sex, gender , gender identity , gender expression , cisgender , transgender , nonbinary , agender , gender-expansive , gender transition , gender dysphoria , sexual orientation , intersex

Jump to Pronouns : questions and answers

Sex refers to a person's biological status and is typically assigned at birth, usually on the basis of external anatomy. Sex is typically categorized as male, female or intersex.

Gender is often defined as a social construct of norms, behaviors and roles that varies between societies and over time. Gender is often categorized as male, female or nonbinary.

Gender identity is one's own internal sense of self and their gender, whether that is man, woman, neither or both. Unlike gender expression, gender identity is not outwardly visible to others.

For most people, gender identity aligns with the sex assigned at birth, the American Psychological Association notes. For transgender people, gender identity differs in varying degrees from the sex assigned at birth.

Gender expression is how a person presents gender outwardly, through behavior, clothing, voice or other perceived characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine or feminine, although what is considered masculine or feminine changes over time and varies by culture.

Cisgender, or simply cis , is an adjective that describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Transgender, or simply trans, is an adjective used to describe someone whose gender identity differs from the sex assigned at birth. A transgender man, for example, is someone who was listed as female at birth but whose gender identity is male.

Cisgender and transgender have their origins in Latin-derived prefixes of "cis" and "trans" — cis, meaning "on this side of" and trans, meaning "across from" or "on the other side of." Both adjectives are used to describe experiences of someone's gender identity.

Nonbinary is a term that can be used by people who do not describe themselves or their genders as fitting into the categories of man or woman. A range of terms are used to refer to these experiences; nonbinary and genderqueer are among the terms that are sometimes used.

Agender is an adjective that can describe a person who does not identify as any gender.

Gender-expansive is an adjective that can describe someone with a more flexible gender identity than might be associated with a typical gender binary.

Gender transition is a process a person may take to bring themselves and/or their bodies into alignment with their gender identity. It's not just one step. Transitioning can include any, none or all of the following: telling one's friends, family and co-workers; changing one's name and pronouns; updating legal documents; medical interventions such as hormone therapy; or surgical intervention, often called gender confirmation surgery.

Gender dysphoria refers to psychological distress that results from an incongruence between one's sex assigned at birth and one's gender identity. Not all trans people experience dysphoria, and those who do may experience it at varying levels of intensity.

Gender dysphoria is a diagnosis listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Some argue that such a diagnosis inappropriately pathologizes gender incongruence, while others contend that a diagnosis makes it easier for transgender people to access necessary medical treatment.

Sexual orientation refers to the enduring physical, romantic and/or emotional attraction to members of the same and/or other genders, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and straight orientations.

People don't need to have had specific sexual experiences to know their own sexual orientation. They need not have had any sexual experience at all. They need not be in a relationship, dating or partnered with anyone for their sexual orientation to be validated. For example, if a bisexual woman is partnered with a man, that does not mean she is not still bisexual.

Sexual orientation is separate from gender identity. As GLAAD notes , "Transgender people may be straight, lesbian, gay, bisexual or queer. For example, a person who transitions from male to female and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a straight woman. A person who transitions from female to male and is attracted solely to men would typically identify as a gay man."

Intersex is an umbrella term used to describe people with differences in reproductive anatomy, chromosomes or hormones that don't fit typical definitions of male and female.

Intersex can refer to a number of natural variations, some of them laid out by InterAct . Being intersex is not the same as being nonbinary or transgender, which are terms typically related to gender identity.

The Picture Show

Nonbinary photographer documents gender dysphoria through a queer lens, pronouns: questions and answers.

What is the role of pronouns in acknowledging someone's gender identity?

Everyone has pronouns that are used when referring to them – and getting those pronouns right is not exclusively a transgender issue.

"Pronouns are basically how we identify ourselves apart from our name. It's how someone refers to you in conversation," says Mary Emily O'Hara , a communications officer at GLAAD. "And when you're speaking to people, it's a really simple way to affirm their identity."

"So, for example, using the correct pronouns for trans and nonbinary youth is a way to let them know that you see them, you affirm them, you accept them and to let them know that they're loved during a time when they're really being targeted by so many discriminatory anti-trans state laws and policies," O'Hara says.

"It's really just about letting someone know that you accept their identity. And it's as simple as that."

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality. Kaz Fantone for NPR hide caption

Getting the words right is about respect and accuracy, says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen, deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

What's the right way to find out a person's pronouns?

Start by giving your own – for example, "My pronouns are she/her."

"If I was introducing myself to someone, I would say, 'I'm Rodrigo. I use him pronouns. What about you?' " says Rodrigo Heng-Lehtinen , deputy executive director of the National Center for Transgender Equality.

O'Hara says, "It may feel awkward at first, but eventually it just becomes another one of those get-to-know-you questions."

Should people be asking everyone their pronouns? Or does it depend on the setting?

Knowing each other's pronouns helps you be sure you have accurate information about another person.

How a person appears in terms of gender expression "doesn't indicate anything about what their gender identity is," GLAAD's Schmider says. By sharing pronouns, "you're going to get to know someone a little better."

And while it can be awkward at first, it can quickly become routine.

Heng-Lehtinen notes that the practice of stating one's pronouns at the bottom of an email or during introductions at a meeting can also relieve some headaches for people whose first names are less common or gender ambiguous.

"Sometimes Americans look at a name and are like, 'I have no idea if I'm supposed to say he or she for this name' — not because the person's trans, but just because the name is of a culture that you don't recognize and you genuinely do not know. So having the pronouns listed saves everyone the headache," Heng-Lehtinen says. "It can be really, really quick once you make a habit of it. And I think it saves a lot of embarrassment for everybody."

Might some people be uncomfortable sharing their pronouns in a public setting?

Schmider says for cisgender people, sharing their pronouns is generally pretty easy – so long as they recognize that they have pronouns and know what they are. For others, it could be more difficult to share their pronouns in places where they don't know people.

But there are still benefits in sharing pronouns, he says. "It's an indication that they understand that gender expression does not equal gender identity, that you're not judging people just based on the way they look and making assumptions about their gender beyond what you actually know about them."

How is "they" used as a singular pronoun?

"They" is already commonly used as a singular pronoun when we are talking about someone, and we don't know who they are, O'Hara notes. Using they/them pronouns for someone you do know simply represents "just a little bit of a switch."

"You're just asking someone to not act as if they don't know you, but to remove gendered language from their vocabulary when they're talking about you," O'Hara says.

"I identify as nonbinary myself and I appear feminine. People often assume that my pronouns are she/her. So they will use those. And I'll just gently correct them and say, hey, you know what, my pronouns are they/them just FYI, for future reference or something like that," they say.

O'Hara says their family and friends still struggle with getting the pronouns right — and sometimes O'Hara struggles to remember others' pronouns, too.

"In my community, in the queer community, with a lot of trans and nonbinary people, we all frequently remind each other or remind ourselves. It's a sort of constant mindfulness where you are always catching up a little bit," they say.

"You might know someone for 10 years, and then they let you know their pronouns have changed. It's going to take you a little while to adjust, and that's fine. It's OK to make those mistakes and correct yourself, and it's OK to gently correct someone else."

What if I make a mistake and misgender someone, or use the wrong words?

Simply apologize and move on.

"I think it's perfectly natural to not know the right words to use at first. We're only human. It takes any of us some time to get to know a new concept," Heng-Lehtinen says. "The important thing is to just be interested in continuing to learn. So if you mess up some language, you just say, 'Oh, I'm so sorry,' correct yourself and move forward. No need to make it any more complicated than that. Doing that really simple gesture of apologizing quickly and moving on shows the other person that you care. And that makes a really big difference."

Why are pronouns typically given in the format "she/her" or "they/them" rather than just "she" or "they"?

The different iterations reflect that pronouns change based on how they're used in a sentence. And the "he/him" format is actually shorter than the previously common "he/him/his" format.

"People used to say all three and then it got down to two," Heng-Lehtinen laughs. He says staff at his organization was recently wondering if the custom will eventually shorten to just one pronoun. "There's no real rule about it. It's absolutely just been habit," he says.

Amid Wave Of Anti-Trans Bills, Trans Reporters Say 'Telling Our Own Stories' Is Vital

But he notes a benefit of using he/him and she/her: He and she rhyme. "If somebody just says he or she, I could very easily mishear that and then still get it wrong."