Problem-Based Learning

Problem-Based Learning (PBL) uses clinical cases to stimulate inquiry, critical thinking and knowledge application and integration related to biological, behavioral and social sciences. Through this active, collaborative, case-based learning process, students acquire a deeper understanding of the principles of medicine and, more importantly, acquire the skills necessary for lifelong learning.

The goal is for students to:

- Acquire, synthesize and apply basic science knowledge in a clinical context

- Engage in critical thinking and problem-solving

- Develop the ability to evaluate their own learning and collaborate with peers

- Effectively use information technology and identify the most appropriate resources for knowledge acquisition and hypothesis testing

- Contextualize and communicate their knowledge to others

- Ask for, provide and incorporate feedback in order to improve performance

Each PBL group has six to nine students and a faculty facilitator. Case information is disclosed progressively across two or more sessions for each case. This process mimics the manner in which a practicing physician obtains data from a patient. PBL allows students to develop hypotheses and identify learning issues as the additional pieces of information about a patient are disclosed to the student.

The students identify learning issues and information needs and assign learning tasks among the group. The students discuss their findings at the next session and review the case in light of their learning. At the conclusion of a case, the students create a concept map synthesizing the knowledge garnered over the course of their discussions to demonstrate their understanding of how the elements of the case integrate with and relate to one another.

Faculty Development Modules

Faculty interested in learning more about PBL should review these online learning modules.

Welcome to PBL: A Guide for Tutors

This module is required for new tutors and optional for experienced tutors who are interested in a refresher course. It is intended to serve as an introduction to facilitating small-group sessions in the PBL course. This video will show you what a PBL session looks like and demonstrates some tutor behaviors. Open the module and use password fsmpbl for access.

PBL Tutor Feedback Module

All tutors (new and experienced) must go through this brief training module to help you provide students with feedback in the context of the PBL course. Open the module (Safari or Firefox recommended) and sign in when prompted with your NetID and password. Completing the module will count toward CME credit.

Kristin Van Genderen, MD

Co-Director

View Faculty Profile

Nahzinine Shakeri, MD

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

Problem based learning

- Related content

- Peer review

- Diana F Wood

Problem based learning is used in many medical schools in the United Kingdom and worldwide. This article describes this method of learning and teaching in small groups and explains why it has had an important impact on medical education.

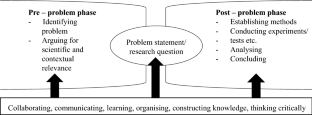

The group learning process: acquiring desirable learning skills

What is problem based learning?

In problem based learning (PBL) students use “triggers” from the problem case or scenario to define their own learning objectives. Subsequently they do independent, self directed study before returning to the group to discuss and refine their acquired knowledge. Thus, PBL is not about problem solving per se, but rather it uses appropriate problems to increase knowledge and understanding. The process is clearly defined, and the several variations that exist all follow a similar series of steps.

Generic skills and attitudes

Chairing a group

Cooperation

Respect for colleagues' views

Critical evaluation of literature

Self directed learning and use of resources

Presentation skills

Group learning facilitates not only the acquisition of knowledge but also several other desirable attributes, such as communication skills, teamwork, problem solving, independent responsibility for learning, sharing information, and respect for others. PBL can therefore be thought of as a small group teaching method that combines the acquisition of knowledge with the development of generic skills and attitudes. Presentation of clinical material as the stimulus for learning enables students to understand the relevance of underlying scientific knowledge and principles in clinical practice.

However, when PBL is introduced into a curriculum, several other issues for curriculum design and implementation need to be tackled. PBL is generally introduced in the context of a defined core curriculum and integration of basic and clinical sciences. It has implications for staffing and learning resources and demands a different approach to timetabling, workload, and assessment. PBL is often used to deliver core material in non-clinical parts of the curriculum. Paper based PBL scenarios form the basis of the core curriculum and ensure that all students are exposed to the same problems. Recently, modified PBL techniques have been introduced into clinical education, with “real” patients being used as the stimulus for learning. Despite the essential ad hoc nature of learning clinical medicine, a “key cases” approach can enable PBL to be used to deliver the core clinical curriculum.

Roles of participants in a PBL tutorial

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

What happens in a PBL tutorial?

PBL tutorials are conducted in several ways. In this article, the examples are modelled on the Maastricht “seven jump” process, but its format of seven steps may be shortened.

A typical PBL tutorial consists of a group of students (usually eight to 10) and a tutor, who facilitates the session. The length of time (number of sessions) that a group stays together with each other and with individual tutors varies between institutions. A group needs to be together long enough to allow good group dynamics to develop but may need to be changed occasionally if personality clashes or other dysfunctional behaviour emerges.

Students elect a chair for each PBL scenario and a “scribe” to record the discussion. The roles are rotated for each scenario. Suitable flip charts or a whiteboard should be used for recording the proceedings. At the start of the session, depending on the trigger material, either the student chair reads out the scenario or all students study the material. If the trigger is a real patient in a ward, clinic, or surgery then a student may be asked to take a clinical history or identify an abnormal physical sign before the group moves to a tutorial room. For each module, students may be given a handbook containing the problem scenarios, and suggested learning resources or learning materials may be handed out at appropriate times as the tutorials progress.

Examples of trigger material for PBL scenarios

Paper based clinical scenarios

Experimental or clinical laboratory data

Photographs

Video clips

Newspaper articles

All or part of an article from a scientific journal

A real or simulated patient

A family tree showing an inherited disorder

PBL tutorial process

Step 1 —Identify and clarify unfamiliar terms presented in the scenario; scribe lists those that remain unexplained after discussion

Step 2 —Define the problem or problems to be discussed; students may have different views on the issues, but all should be considered; scribe records a list of agreed problems

Step 3 —“Brainstorming” session to discuss the problem(s), suggesting possible explanations on basis of prior knowledge; students draw on each other's knowledge and identify areas of incomplete knowledge; scribe records all discussion

Step 4 —Review steps 2 and 3 and arrange explanations into tentative solutions; scribe organises the explanations and restructures if necessary

Step 5 —Formulate learning objectives; group reaches consensus on the learning objectives; tutor ensures learning objectives are focused, achievable, comprehensive, and appropriate

Step 6 —Private study (all students gather information related to each learning objective)

Step 7 —Group shares results of private study (students identify their learning resources and share their results); tutor checks learning and may assess the group

The role of the tutor is to facilitate the proceedings (helping the chair to maintain group dynamics and moving the group through the task) and to ensure that the group achieves appropriate learning objectives in line with those set by the curriculum design team. The tutor may need to take a more active role in step 7 of the process to ensure that all the students have done the appropriate work and to help the chair to suggest a suitable format for group members to use to present the results of their private study. The tutor should encourage students to check their understanding of the material. He or she can do this by encouraging the students to ask open questions and ask each other to explain topics in their own words or by the use of drawings and diagrams.

PBL in curriculum design

PBL may be used either as the mainstay of an entire curriculum or for the delivery of individual courses. In practice, PBL is usually part of an integrated curriculum using a systems based approach, with non-clinical material delivered in the context of clinical practice. A module or short course can be designed to include mixed teaching methods (including PBL) to achieve the learning outcomes in knowledge, skills, and attitudes. A small number of lectures may be desirable to introduce topics or provide an overview of difficult subject material in conjunction with the PBL scenarios. Sufficient time should be allowed each week for students to do the self directed learning required for PBL.

Designing and implementing a curriculum module using PBL supported by other teaching methods

Writing PBL scenarios

PBL is successful only if the scenarios are of high quality. In most undergraduate PBL curriculums the faculty identifies learning objectives in advance. The scenario should lead students to a particular area of study to achieve those learning objectives.

How to create effective PBL scenarios*

Learning objectives likely to be defined by the students after studying the scenario should be consistent with the faculty learning objectives

Problems should be appropriate to the stage of the curriculum and the level of the students' understanding

Scenarios should have sufficient intrinsic interest for the students or relevance to future practice

Basic science should be presented in the context of a clinical scenario to encourage integration of knowledge

Scenarios should contain cues to stimulate discussion and encourage students to seek explanations for the issues presented

The problem should be sufficiently open, so that discussion is not curtailed too early in the process

Scenarios should promote participation by the students in seeking information from various learning resources

*Adapted from Dolmans et al. Med Teacher 1997;19:185-9

Staff development

Introducing PBL into a course makes new demands on tutors, requiring them to function as facilitators for small group learning rather than acting as providers of information. Staff development is essential and should focus on enabling the PBL tutors to acquire skills in facilitation and in management of group dynamics (including dysfunctional groups).

A dysfunctional group: a dominant character may make it difficult for other students to be heard

Tutors should be also given information about the institution's educational strategy and curriculum programme so that they can help students to understand the learning objectives of individual modules in the context of the curriculum as a whole. Methods of assessment and evaluation should be described, and time should be available to discuss anxieties.

Advantages and disadvantages of PBL

- View inline

Staff may feel uncertain about facilitating a PBL tutorial for a subject in which they do not themselves specialise. Subject specialists may, however, be poor PBL facilitators as they are more likely to interrupt the process and revert to lecturing. None the less, students value expertise, and the best tutors are subject specialists who understand the curriculum and have excellent facilitation skills. However, enthusiastic non-specialist tutors who are trained in facilitation, know the curriculum, and have adequate tutor notes, are good PBL tutors.

Assessment of PBL

Student learning is influenced greatly by the assessment methods used. If assessment methods rely solely on factual recall then PBL is unlikely to succeed in the curriculum. All assessment schedules should follow the basic principles of testing the student in relation to the curriculum outcomes and should use an appropriate range of assessment methods.

Further reading

- Norman GR ,

Assessment of students' activities in their PBL groups is advisable. Tutors should give feedback or use formative or summative assessment procedures as dictated by the faculty assessment schedule. It is also helpful to consider assessment of the group as a whole. The group should be encouraged to reflect on its PBL performance including its adherence to the process, communication skills, respect for others, and individual contributions. Peer pressure in the group reduces the likelihood of students failing to keep up with workload, and the award of a group mark—added to each individual's assessment schedule— encourages students to achieve the generic goals associated with PBL.

PBL is an effective way of delivering medical education in a coherent, integrated programme and offers several advantages over traditional teaching methods. It is based on principles of adult learning theory, including motivating the students, encouraging them to set their own learning goals, and giving them a role in decisions that affect their own learning.

Predictably, however, PBL does not offer a universal panacea for teaching and learning in medicine, and it has several well recognised disadvantages. Traditional knowledge based assessments of curriculum outcomes have shown little or no difference in students graduating from PBL or traditional curriculums. Importantly, though, students from PBL curriculums seem to have better knowledge retention. PBL also generates a more stimulating and challenging educational environment, and the beneficial effects from the generic attributes acquired through PBL should not be underestimated.

Acknowledgments

Christ and St John with Angels by Peter Paul Rubens is from the collection of the Earl of Pembroke/BAL. The Mad Hatter's Tea Party is by John Tenniel.

The ABC of learning and teaching in medicine is edited by Peter Cantillon, senior lecturer in medical informatics and medical education, National University of Ireland, Galway, Republic of Ireland; Linda Hutchinson, director of education and workforce development and consultant paediatrician, University Hospital Lewisham; and Diana F Wood, deputy dean for education and consultant endocrinologist, Barts and the London, Queen Mary's School of Medicine and Dentistry, Queen Mary, University of London. The series will be published as a book in late spring.

Advertisement

Problem-based projects in medical education: extending PBL practices and broadening learning perspectives

- Published: 22 October 2019

- Volume 24 , pages 959–969, ( 2019 )

Cite this article

- Diana Stentoft ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6753-9110 1

2461 Accesses

22 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Medical education strives to foster effective education of medical students despite an ever-changing landscape in medicine. This article explores the utility of projects in problem-based learning— project - PBL —as a way to supplement traditional case-PBL. First, project-PBL may enhance student engagement and motivation by allowing them to direct their own learning. Second, project-PBL may help students develop metacognitive competencies by forcing them to collaborate and regulate learning in settings without a facilitator. Finally, project-PBL may foster skills and competencies related to medical research. As illustrated through a brief example from Aalborg University, Denmark, students learn differently from project-PBL and case-PBL, and so one implementation cannot simply replace the other. I conclude by suggesting future directions for research on project-PBL to explore its benefits in medical education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

AAU. (2017). Curriculum for B.sc. in medicine faculty of medicine . Aalborg University. https://studieordninger.aau.dk/2019/14/780 .

AAU. (2018). Curriculum for M.sc. in medicine: faculty of medicine . Aalborg University. https://studieordninger.aau.dk/2019/17/901 .

Amgad, M., Tsui, M. M. K., Liptrott, S. J., & Shash, E. (2015). Medical student research: An integrated mixed-methods systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 10 (6), e0127470.

Google Scholar

Askehave, I., Prehn, H., Pedersen, J., & Pedersen, M. T. (2015). PBL—Problem-based learning Aalborg . Denmark: Aalborg University.

Barrett, T., Cashman, D., & Moore, S. (2011). Designing problems and triggers in different media. In T. Barrett & S. Moore (Eds.), New approaches to problem-based learning revitalising your practice in higher education (pp. 18–35). New York: Routledge.

Barrett, T., & Moore, S. (2011). An introduction to problem-based learning. In T. Barrett & S. Moore (Eds.), New approaches to problem-based learning revitalising your practice in higher education (pp. 3–17). New York: Routledge.

Barrows, H. S. (1986). A taxonomy of problem-based learning methods. Medical Education, 20 (6), 481–486.

Barrows, H. S. (1996). Problem-based learning in medicine and beyond: a brief overview. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 68, 3–12.

Berkhout, J., Helmich, E., Teunissen, P., van der Vleuten, C. P. M., & Jaarsma, A. D. C. (2018). Context matters when striving to promote active and lifelong learning in medical education. Medical Education, 52, 34–44.

Biggs, J., & Tang, C. (2009). Teaching for quality learning at university (3rd ed.). Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Charlin, B., Mann, K., & Hansen, P. (1998). The many faces of problem-based learning: A framework for understanding and comparison. Medical Teacher, 20 (4), 323–330.

Czabanowska, K., Moust, J. H. C., Meijer, A. W. M., Schröder-Bäck, P., & Roebertsen, H. (2012). Problem-based learning revisited, introduction of active and self-directed learning to reduce fatigue among students. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 9 (1), 1–13.

David, T., Patel, L., Burdett, K., & Rangachari, P. (1999). Problem-based learning in medicine . London: The Royal Society of Medicine Press Limited.

Davis, M. H., & Harden, A. (1999). AMEE Medical education guide no 15: Problem-based learning—A practical guide. Medical Teacher, 21 (2), 130–140.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research . Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

de Graff, E., & Kolmos, A. (2003). Characteristics of problem-based learning. International Journal of Engineering Education, 5 (19), 657–662.

Dolmans, D., & Schmidt, H. (2010). The problem-based learning process. In H. van Berkel, A. Scherpbier, H. Hillen, & C. van der Vleuten (Eds.), Lessons from problem-based learning (pp. 13–18). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elliot, M., Howard, P., Nouwens, F., Stojcevski, A., Mann, L., Prpic, J. K., et al. (2012). Developing a conceptual model for the effective assessment of individual student learning in team-based subjects. Australasian Journal of Engineering Education, 18 (1), 105–112.

English, M. C., & Kitsantas, A. (2013). Supporting student sefl-regulated learning in problem- and project-based learning. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 7 (2), 128–150.

Frank, J. R., Snell, L., & Scherbino, J. (Eds.). (2015). CanMEDS 2015: Physician competency framework . Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada.

Galand, B., Frenay, M., & Raucent, B. (2012). Effectiveness of problem-based learning in engineering education: A comparative study on three levels of knowledge structure. Internatioal Journal of Engineering Education, 28 (4), 939–947.

Gijselaers, W. H. (1996). Connecting problem-based practices with educational theory. In L. Wilkerson & W. H. Gijselaers (Eds.), Bringing problem-based learning to higher education: Theory and practice . San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

Helle, L., Tynjälä, P., & Olkinuora, E. (2006). Project-based learning in post-secondary education: Theory practice and rubber sling shots. Higher Education, 51 (2), 287–314.

Hmelo, C. E. (2004). Problem-based learning: What and how do students learn? Educational Psychology Review, 16 (3), 235–266.

Holgaard, J. E., Rybert, T., Stegeager, N., Stentoft, D., & Thomassen, A. O. (2014). PBL: Problembaseret læring og projektarbejde ved de videregående uddannelser . Copenhagen: Samfundslitteratur.

Illeris, K. (1974). Problemorientering og deltagerstyring: oplæg til en alternativ didaktik . Odense: Fyens Stiftsbogtrykkeri.

Kolmos, A. (2009). Problem-based and project-based learning. In O. Skovsmose, P. Valero, & O. Ravn Christensen (Eds.), University science and mathematics education in transition (1st edn ed., pp. 261–280). New York: Springer.

Kolmos, A., Du, X., Holgaard, J. E., & Jensen, L. P. (2008). Facilitation in a PBL environment . Aalborg: Publication for Centre for Engineering Education Research and Development.

Kolmos, A., Fink, F. K., & Krogh, L. (2004). The Aalborg model: Problem-based and project-organized learning. In A. Kolmos, F. K. Fink, & L. Krogh (Eds.), The Aalborg PBL model (1st ed., pp. 9–18). Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

Kolmos, A., & Holgaard, J. E. (2007). Alignment of PBL and assessment. Journal of Engineering Education, 96 (4), 1–9.

Lähteenmäki, M., & Uhlin, L. (2011). Developing reflective practitioners through pbl in academic and practice environments. In T. Barrett & S. Moore (Eds.), New approaches to problem-based learning revitalising your practice in higher education (pp. 144–157). New York: Routledge.

Laidlaw, A., Aiton, J., Struthers, J., & Guild, S. (2012). Developing research skills in medical students: AMEE Guide no. 69. Medical Teacher, 34 (9), 754–771.

Laursen, E. (2013). PPBL: A flexible model addressing the problems of transfer. In L. Krogh & A. A. Jensen (Eds.), Visions challenges and strategies: PBL principles and methodologies in a Danish and global perspective (pp. 29–46). Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

Lyon, M. L. (2009). Epistemology, medical science and problem-based learning: intruducing an epistemological dimension into the medical-school curriculum. In C. Brosnan & B. S. Turner (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of medical education (pp. 207–224). Oxon: Routledge.

MacDonald, P. J. (1997). Selection of health problems for a problem-based curriculum. In D. Boud & G. Feletti (Eds.), The challenge of problem-based learning (2nd ed., pp. 93–102). New York: Routledge.

Moust, J., & Roebertsen, H. (2010). Alternative instructional problem-based learning formats. In H. van Berkel, A. Scherpbier, H. Hillen, & C. van der Vleuten (Eds.), Lessons from problem-based learning (pp. 129–140). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Moust, J., Van Berkel, H. J. M., & Schmidt, H. G. (2005). Signs of erosion: Reflections on three decades of problem-based learning at Maastricht University. Higher Education, 50, 665–683.

Savery, J. R. (2006). Overview of problem-based learning: Definitions and distinctions. The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 1 (1), 9–20.

Savin-Baden, M. (2014). Using problem-based learning: New constellations for the 21st century. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 25 (3&4), 1–24.

Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2004). Foundations of problem based learning (p. 2004). Buckingham: Society for Research into Higher Education & Open University Press.

Schmidt, H. G. (1983). Problem-based learning: Rationale and description. Medical Education, 17 (1), 11–16.

Schreiner, M. P., Bruun, S. R., Liljenberg, C. K., & Svendsen, J. L. (2018). The effect of run on pain perception—B.sc. medicine 6th semester . Aalborg: Aalborg University.

Servant, V. F. C. (2016). Revolutions and re-iterations . Riddekerk: Ridderprint BV.

Stefanou, C., Stolk, J. D., Prince, M., Chen, J. C., & Lord, S. M. (2013). Self-regulation and autonomy in problem- and project-based learning environments. Active Learning in Higher Education, 14 (2), 109–122.

Stentoft, D. (2017). From saying to doing interdisciplinary learning—Is PBL the answer? Active Learning in Higher Education, 18 (1), 51–61.

Stentoft, D., Duroux, M., Fink, T., & Emmersen, J. (2014). From cases to projects in problem-based medical education. Journal of Problem Based Learning in Higher Education, 2 (1), 45–62.

Sundhedsstyrelsen. (2013). De 7 Lægeroller . www.sst.dk Sundhedsstyrelsen.

Thorndahl, K., Velmurugan, G. & Stentoft, D. (2018) The significance of problem analysis for critical thinking in problem-based project work. In Sunyu, W., Kolmos, A., Guerra, A., & Weifeng, Q. (Eds.). 7th International research symposium on PBL: innovation, PBL and competences in engineering education . Aalborg: Aalborg Universitetsforlag.

Wood, D. F. (2003). ABC of learning and teaching in medicine—Problem based learning. British Medical Journal, 326, 328–330.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Health Science Education and Problem-Based Learning, Aalborg University, Fredrik Bajers Vej 7D, 9220, Aalborg Ø, Denmark

Diana Stentoft

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Diana Stentoft .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Stentoft, D. Problem-based projects in medical education: extending PBL practices and broadening learning perspectives. Adv in Health Sci Educ 24 , 959–969 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09917-1

Download citation

Received : 09 April 2019

Accepted : 31 August 2019

Published : 22 October 2019

Issue Date : December 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-019-09917-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Active learning

- Problem-based learning

- Project-PBL

- Student-centred learning

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

What, how and why is problem-based learning in medical education?

Problem-based learning, or PBL, is a pedagogical practice employed in many medical schools. While there are numerous variants of the technique, the approach includes the presentation of an applied problem to a small group of students who engage in discussion over several sessions. A facilitator, sometimes called a tutor, provides supportive guidance for the students. The discussions of the problem are structured to enable students to create conceptual models to explain the problem presented in the case. As the students discover the limits of their knowledge, they identify learning issues – essentially questions they cannot answer from their fund of knowledge. Between meetings of the group, learners research their learning issues and share results at the next meeting of the group.

.jpg)

How do faculty members participate in this process?

Why are medical schools incorporating pbl, can you give me an example of how the process works, what student skills should we encourage for pbl-focused medical education, enjoy reading asbmb today.

Become a member to receive the print edition monthly and the digital edition weekly.

Jose Barral is the associate dean for academic affairs at the UTMB Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences.

Era Buck is a senior medical educator in the Office of Educational Development and an assistant professor in the department of family medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston, Texas.

Related articles

Featured jobs.

from the ASBMB career center

Get the latest from ASBMB Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Careers

Careers highlights or most popular articles.

Strong bonds and a startup

Kevin Lewis’ career path shows that networking is not just about meeting new people to find job leads. Keeping in touch with people from your past can net you opportunities too.

A career challenge

Susan Marqusee balances running a lab at UC Berkeley with leading one of the largest initiatives at the NSF.

Calendar of events, awards and opportunities

This week: Vote in the JBC Methods Madness semifinals!

Getting the most from conferences as an introvert

There are several ways to make good use of conferences even if milling around and chatting to random strangers isn’t your cup of tea.

Meet Parmvir Bahia

The neuroscientist is a science communicator and leads an outreach nonprofit.

This week: Vote in the JBC Methods Madness quarterfinals! PROLAB deadline extended. Just added: Fresh industry partnership opportunities from HALO.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Bull Med Libr Assoc

- v.81(3); 1993 Jul

Problem-based learning in American medical education: an overview.

The recent trend toward problem-based learning (PBL) in American medical education amounts to one of the most significant changes since the Flexner report motivated global university affiliation. In PBL, fundamental knowledge is mastered by the solving of problems, so basic information is learned in the same context in which it will be used. Also, the PBL curriculum employs student initiative as a driving force and supports a system of student-faculty interaction in which the student assumes primary responsibility for the process. The first PBL medical curriculum in North America was established at McMaster University in Toronto in 1969. The University of New Mexico was the first to adopt a medical PBL curriculum in the United States, and Mercer University School of Medicine in Georgia was the first U.S. medical school to employ PBL as its only curricular offering. Many interpretations of the basic PBL plan are in use in North American medical schools. Common features include small-group discussions of biomedical problems, a faculty role as facilitator, and the student's relative independence from scheduled lectures. The advantages of PBL are perceived as far outweighing its disadvantages, and the authors conclude that eventually it will see wider use at all levels of education.

Full text is available as a scanned copy of the original print version. Get a printable copy (PDF file) of the complete article (789K), or click on a page image below to browse page by page. Links to PubMed are also available for Selected References .

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Neufeld VR, Woodward CA, MacLeod SM. The McMaster M.D. program: a case study of renewal in medical education. Acad Med. 1989 Aug; 64 (8):423–432. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jonas HS, Etzel SI, Barzansky B. Educational programs in US medical schools. JAMA. 1991 Aug 21; 266 (7):913–920. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kaufman A, Mennin S, Waterman R, Duban S, Hansbarger C, Silverblatt H, Obenshain SS, Kantrowitz M, Becker T, Samet J, et al. The New Mexico experiment: educational innovation and institutional change. Acad Med. 1989 Jun; 64 (6):285–294. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Colvin RB, Wetzel MS. Pathology in the new pathway of medical education at Harvard Medical School. Am J Clin Pathol. 1989 Oct; 92 (4 Suppl 1):S23–S30. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Donner RS, Bickley H. Problem-based learning: an assessment of its feasibility and cost. Hum Pathol. 1990 Sep; 21 (9):881–885. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 08 March 2024

Professional values at the beginning of medical school: a quasi-experimental study

- Sandra Vilagra 1 ,

- Marlon Vilagra 1 ,

- Renata Giaxa 2 ,

- Alice Miguel 3 ,

- Lahis W. Vilagra 1 ,

- Mariana Kehl 2 ,

- Milton A. Martins 2 &

- Patricia Tempski 2

BMC Medical Education volume 24 , Article number: 259 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

202 Accesses

Metrics details

Teaching professionalism in medical schools is central to medical education and society. We evaluated how medical students view the values of the medical profession on their first day of medical school and the influence of a conference about the competences of this profession on these students’ levels of reflection.

We studied two groups of medical students who wrote narratives about the values of the medical profession and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on these values. The first group wrote the narratives after a conference about the competences of the medical profession (intervention group), and the second group wrote the same narratives after a biochemistry conference (control group). We also compared the levels of reflection of these two groups of students.

Among the 175 medical students entering in the 2022 academic year, 159 agreed to participate in the study (response rate = 90.8%). There were more references to positive than negative models of doctor‒patient relationships experienced by the students (58.5% and 41.5% of responses, respectively). The intervention group referred to a more significant number of values than the control group did. The most cited values were empathy, humility, and ethics; the main competences were technical competence, communication/active listening, and resilience. The students’ perspectives of the values of their future profession were strongly and positively influenced by the pandemic experience. The students realized the need for constant updating, basing medical practice on scientific evidence, and employing skills/attitudes such as resilience, flexibility, and collaboration for teamwork. Analysis of the levels of reflection in the narratives showed a predominance of reflections with a higher level in the intervention group and of those with a lower level in the control group.

Conclusions

Our study showed that medical students, upon entering medical school, already have a view of medical professionalism, although they still need to present a deeper level of self-reflection. A single, planned intervention in medical professionalism can promote self-reflection. The vision of medical professional identity was strongly influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, positively impacting the formation of a professional identity among the students who decided to enter medical school.

Peer Review reports

Professionalism is essential to society’s trust in the medical profession and is central to the doctor‒patient relationship [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Professionalism includes placing the interests of patients above those of physicians and acting according to high standards of competence and integrity [ 3 ]. In line with the American College of Physicians and other internal medicine societies, professionalism includes many professional responsibilities, such as commitment to professional competence, honesty with patients, patient confidentiality, maintaining appropriate relations with patients, improving quality and access to care, just distribution of finite resources, scientific knowledge, managing conflicts of interest and professional responsibilities [ 3 , 4 ].

The development of medical professionalism in undergraduate medical education is a complex enterprise that involves substantial compromise with society in general and with a person individually [ 5 , 6 ]. Developing and teaching professionalism in medical schools has been considered central to medical education and has been the subject of many previous studies [ 7 , 8 ]. However, to better teach professional values, it is imperative to know what students think and know about the values of the medical profession when starting medical school.

The years of the COVID-19 pandemic had a significant influence on how society views the medical profession and its values, and medical students who started medical school in 2022 or 2023 were strongly influenced by the changes imposed on society and schools, at least in countries that had a substantial impact of COVID-19 [ 9 , 10 ].

In the present study, we evaluated how medical students view the values of the medical profession on their first day of medical school. We studied two groups of medical students who wrote narratives about the values of the medical profession and the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on their perceptions of these values on the first day of medical school. The first group wrote the narratives after a conference about the competences of the medical profession, and the second group wrote the same narratives after a biochemistry conference. Our goal was to evaluate the values of professionalism that medical students consider important before starting medical school and the impact of one intervention on medical professionalism on these responses.

We performed a quasi-experimental study involving 175 first-year medical students in the School of Medicine of the University of Sao Paulo (USP), Brazil.

The research ethics committee of the School of Medicine of the University of Sao Paulo approved this study (Protocol 56043522.9.0000.0068). Participation was voluntary, without compensation or incentives. We guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Data collection was performed in March 2022, on the first day of the medical program, after the participating students completed a written consent form. The study was performed in the classroom using notebooks and/or cell phones to access the electronic forms during regular academic activity.

Study design

We divided the students into two groups. The control group (CG) attended a biochemistry class before study participation, and the intervention group (IG) attended a lecture about “The competences of a physician in the 21st century” and then was asked to participate in the study.

At the conference, the competency framework of the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (CanMeds) was presented [ 11 ]. This framework includes medical expert, communicator, collaborator, leader, health advocate, scholar, and professional general competences. In this conference, general competences of the 21st century, including critical thinking, collaboration, communication, creativity, connectivity, and respect for diversity, were also discussed.

Both groups had two hours to complete four narratives:

“Tell us something that happened to you in your life that influenced your view of the medical profession.”

“What are, in your opinion, the main medical profession values?”

“How do you imagine yourself working as a medical doctor ten years after graduation?”

“How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your view of the medical profession and your future practice?”

At the end of the study, the control group attended the medical education class, and the intervention group attended the biochemistry class.

Critical incident reports and self-reflection

The first narrative (“Tell us something that happened to you in your life that influenced your view of the medical profession”) was a critical incident report. Critical incident reports are short personal narratives about the experiences of medical students, residents, and other learners that can be used to address values and attitudes and discuss professionalism [ 12 , 13 ]. These narratives focus on the meaning of these experiences for developing professional identity and personal growth [ 14 ]. The use of critical incidents is a reflective method that can potentially enhance critical thinking [ 12 ].

We used critical incident reports and the other narratives to analyze the impacts of life events and their meaning, the role of the COVID-19 pandemic in the students’ decisions to be physicians, and their expectations and vision of the values of the medical profession and health care.

Data analysis

We used the COREQ model to assess the quality of the research process and data analysis [ 15 ]. The qualitative analysis was based on the students’ narratives. These narratives were prepared for analysis and categorized according to traditional content analysis methods [ 16 , 17 , 18 ]. Three independent researchers started with a free reading of the transcribed text without trying to categorize it. During the second reading, the researchers categorized themes and derived issues separately. Finally, each researcher’s products were paired by similarities in meaning and were discussed with the research group. The results were divided into analytical categories, items, and examples. The same group performed the reflection analysis, which started with individual classification, followed by group discussion.

In our study, we chose to analyze the medical students’ reflections using the framework of Nieme [ 19 ], which includes four levels of reflection: (1) committed reflection, in which one discusses meanings and learnings from experience and how they have affected his or her professional identity or practice and provides some evidence; (2) emotional exploration, which is characterized by emotional expressions and self-awareness, showing some signs of reflection; (3) objective reporting, in which one presents facts that he or she acted as a participant or observer, without or with few expressions of their reactions and the elaboration of the experiences; and (4) scant and avoidant reporting, which consists of short or superficial reporting.

We used the chi-square test to compare the levels of self-reflection between the two groups (questions 1, 3 and 4) and answers to question 2. The significance level was established at 0.05.

Among the 175 medical students entering in the 2022 academic year, 159 agreed to participate in the study (response rate = 90.8%). Sixteen students were not included because they were absent at both collection moments. No student who was present refused to participate in the survey. The age of the participants ranged from 17 to 39 years (average = 20.3 ± 3.6 years); 90 were males (56.6%), and 69 were females. The percentage of male students was similar in both groups, with 57.3% and 55.1% in the intervention group and the control group, respectively.

The analysis of the answers to the question “Tell us something that happened to you in your life that influenced your view of the medical profession” generated three categories: “Process of illness and care”, “Role models”, and “Previous correlated experiences” (Table 1 ). In the category of “Process of illness and care”, emphasis was placed on the positive and negative models of the doctor‒patient relationship that were experienced, with the positive models being sources of inspiration and the negative models being catalysts for entering the profession and changing the current scenario. We observed that positive models were more frequent than negative models (58.5% and 41.5% of responses, respectively). Medical performance in the COVID-19 pandemic was included as a specific item, given the frequency with which the participants highlighted it. Interprofessional care and the idea that doctors do not work in isolation were highlighted, as shown in the following statement:

“The pandemic has further highlighted medical dedication and the importance of interprofessional service collaboration…” (S44, female, 20 years old, IG)

The second category, “Role models”, included inspiring encounters with teachers/professors, managers, and professionals, as well as the inspiring potential of films and books with medical protagonists in the construction of the students’ imaginaries about the future profession.

The third category, “Previous correlated experiences”, shows the influence of diverse events and contexts, as determinants in the choice of the medical profession. Notably, the students appreciated the possibilities they had to approach medical practice and subjects of this scenario, in guided tours or volunteering, as well as the importance of the health system and universities in bringing the population closer to medical professionals, as shown in the following quote:

“Because of my admiration for primary care and my taste for science, I decided to choose a medical career ”. (S90, male, 20 years old, CG)

Through analysis of the answers to the question “What are, in your opinion, the main medical profession values?“, seven values and four competences that were relatively more cited could be identified, which showed that the participants had overlapped the two concepts. It was also possible to verify that the intervention group, which had attended a class on the general competences of doctors, referred more frequently to the competences and cited a more significant number of values than the control group, which had attended a biochemistry class. The most cited values were empathy, humility, and ethics; the main competences were technical competence, communication/active listening, and resilience (Table 2 ).

The answers to the question “How do you imagine yourself working as a medical doctor ten years after graduation?” informed the generation of three categories: “Academic activity”, “Assistance activity”, and “Personal-Professional Life Balance” (Table 3 ). In the category “Academic activity”, it was observed that the newcomers perceived and valued academic activity as a way to positively impact society. The idea that knowledge should be shared was also frequently mentioned, as shown by this participant:

“I will seek to become a university professor and be able to positively impact the education of younger people”. (S94, male, 33 2 years old , CG)

The category “Assistance activity” shows that the entrant to medical school has a multifaceted vision of his future, which includes both activities to improve the public health system and highly specialized well-paid work. The items “Recognition” and “Success” complement each other and reinforce the idea of measuring success in terms of serving those in need and being well paid. The item “Professionalism” brings the desire to practice medicine based on the values and skills mentioned above, as shown in the following quote:

“I envision myself providing ethical, benevolent, and empathetic care to all types of patients in need of a doctor”. (S30, male, 18 years old , IG)

The third category, “Personal-Professional Life Balance”, includes statements about self-care practices, the development of hobbies, and reduced working time. However, few students’ responses were classified in this category (11 students).

The analysis of the answers to the question “How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your view of the medical profession and your future practice?” informed the generation of three categories: “Professional training”, “Resignification of the profession”,, and “Purpose” (Table 4 ).

In the “Professional training” category, it was possible to verify that facing the challenge of a pandemic made students realize the need for constant updating and basing medical practice on scientific evidence. This category also includes statements focusing on skills/attitudes such as resilience, flexibility, and collaboration for teamwork, as illustrated by one participant’s statement:

“It reinforced my desire to work in medicine, highlighting the importance of the health professional.” (S4, female, 18 years old , IG).

In the category “Resignification of the profession”, the item “Values” highlights the students’ narratives in the previous questions, emphasizing courage and altruism as values demonstrated by health professionals during the pandemic. There were surprising statements about the reconstruction of the “superhero” professional model, which was replaced by a more humane and realistic view of the general limits of medical practice and medicine. One student made the following remark:

“ It has influenced my view of doctors by destroying the superhero doctor image I once had; it has become clear that the most that can be done are what is humanly possible, which often may not be enough”. (S128, female, 17 years old , CG).

Additionally, in this category, the item “Health system” brings the recognition that medical practice is done in the system and for the health system, which in Brazil is represented by the public and universal Unified Health System (SUS), which did organize and guarantee access to free care during the pandemic.

The category “Purpose” included statements that highlighted the pandemic events as the main catalysts for students to understand the role of medicine in their lives and the meaning that care would give them.

“ I realized the role of health professionals goes beyond the profession; it is a purpose you have for other people”. (S111, female, 18 years old , CG)

An analysis of the levels of reflection, which included diffuse description, objective description, emotional exploration, and reflection with commitment, was carried out in both groups. For comparison between the two groups of students, we clustered the categories of lower levels of reflection (diffuse description and objective description) and the categories corresponding to higher levels of reflection (emotional exploration and reflection with commitment) (Table 5 ). There was a predominance of reflections with a higher level in the intervention group. In contrast, in the control group, descriptions with a lower level of reflection predominated in the three questions analyzed.

Several authors in the field of adult education, such as Malcolm Knowles, Lev Vygotsky, and Paulo Freire, consider it fundamental for meaningful and effective learning to know what the learner already knows or has experienced [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. This view of education was the framework for our study. Considering the formation of an ethical professional identity, with the values of the profession being fundamental for medical training and society, we studied the vision of the medical profession that medical students bring when they enter medical school.

We invited students who had just entered medical school to describe their views on questions related to critical incidents, values of the medical profession, expectations of the future professional, and influences of the COVID-19 pandemic on their choice to practice medicine. The questions were designed neutrally, without the intention to induce either positive or negative responses. It should be noted that the timing of data collection, still during the COVID-19 pandemic, must have influenced the observed results. We analyzed how the experiences lived until their entry into university transformed their vision of the medical professional they would like to build, as well as the impact observed in an isolated pedagogical intervention in proposing reflection and changes in developing their professional identity.

According to Charon, we can understand the meaning of narratives through cognitive, symbolic, and affective means [ 23 ]. When the students were encouraged to narrate a significant event (critical incident) that motivated them to choose the medical profession (question one), a particular emphasis was given to the category “Process of illness and care”, with recollections of illness experiences in their personal lives and family spheres that influenced their choice of the medical profession. Notably, illness experiences were presented as critical or memorable incidents, which are defined by Mezirow [ 24 ] as transformative events capable of promoting critical and profound reflections, leading to paradigm shifts in the construction of professional identity.

According to Flanagan [ 25 ], an incident is any observable human activity that is sufficiently complete, in itself, to allow inferences about the person performing the action. To be critical, an incident must occur in a situation in which its influence is apparent to the observer, leaving no doubt about its effects.

Branch [ 12 ] describes that critical incident reports are ideal for assessing values and attitudes and teaching professional development, endorsing the tool as effective for describing one’s professional experiences.

Additionally, on question one, it is worth mentioning that the professional models that existed before entering medical school strongly influence the design of the construction of being a doctor, as they act as guides of professional transformation, as proposed by Gardeshi et al. [ 26 ] and Brennan et al. [ 1 ]. According to Cruess et al. [ 27 ], role models are mirrors of technical values and ethical and humanistic principles for a future doctor, allowing him or her to create a critical basis necessary for decision-making in his or her professional life.

Regarding the fundamental values of the medical profession (question two), we observed that students already bring values with them, even those who recently started school, as Reimer et al. [ 28 ] proposed. However, the intervention group referred more to values and competences than the control group, denoting that the intervention had a positive impact in stimulating a deeper reflection about their professional identity. Students in the intervention group cited empathy, humility, ethics, humanism, respect, and solidarity as medical professional values more than students in the control group.

A pedagogical intervention is an interference in the teaching-learning process that is applied by an educator with the goal of overcoming obstacles and optimizing the construction of knowledge, in addition to producing impact and promoting changes in directions for the future [ 29 ]. In the present study, we analyzed and compared the impact of students’ exposure to medical professionalism content in the intervention group to a control group. For Holden et al. [ 7 ], multiple interventions during their training, even if punctual, will contribute to the dynamic process of professional identity formation.

When we asked the students how they imagine practicing medicine ten years after graduation (question three), some could not envision the future scenario, perhaps because they were just starting medical school. However, many cited academic life as a way to impact the training of new young people. Another possible path expressed in the category “assistance” was based on humanistic professional values, simultaneous involvement with the private and public health system, and the construction of professional and financial recognition. Quality of life and balance between professional and personal life were addressed as a theme in only a few narratives.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on Brazil, which was the second country in the world in terms of the number of deaths [ 30 ]. All the students who answered the questions spent approximately two years living with health restrictions and taking classes almost exclusively remotely [ 31 ]. It is essential to assess the impact of this whole experience on the vision of the medical professional identity of these students.

To evaluate the answers to question four, “How did the COVID-19 pandemic influence your view of the medical profession and your future practice?”, we must consider that the occurrence of a significant event, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, strongly influenced the statements about finding a true purpose for future professional life and the discovery of a medicine based on ethical values. It should be highlighted in the quotes how much the pandemic catalyzed the need to reflect on scientific and technical qualifications, teamwork, and multiple fronts. From the students’ perspective, the impact of the pandemic was positive in terms of the values of the profession as a service to society and teamwork and even in terms of the decision to pursue a career as a doctor.

How medical students reflect on the critical incidents that occur during their academic training has great value in the formation of their medical identity. The greater their ability to reflect deeply and critically on events is, the more transformative their learning will be, which is why many educational institutions have incorporated training in their curricula to increase the reflective practice of future professionals [ 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 ].

In addition to the analysis of the categories, the answers to questions one, three, and four were also analyzed regarding the level of reflection developed by each student. The scale of reflective complexity proposed by Niemi [ 19 ] was used as a tool for analyzing reflections.

In the analysis of the totality of the reflections of the three questions, we noticed a predominance of reflections of the objective description (OD) and diffuse description (DD) type, that is, descriptions with less reflection and critical capacity among the students who did not attend the conference on professionalism and who constitute the group that did not have any contact with the discussion of the values of the profession within the medical course. This fact is in line with the results of Montgomery [ 36 ], who observed a design with a preponderance of low levels of reflection in students in the preclinical phase, as only 45.7% of the students were able to issue reflective reports when describing the proposed questions. For Niemi [ 19 ], the scarcity of critical reflections found among groups of students in the preclinical phase of the medical course is justified by the absence of memorable critical experiences or incidents, which prevents them from envisioning their “professional self” at a future point in time [ 37 ]..

When we evaluated the three questions in terms of differences between the intervention and control groups, we observed that reflections of the objective description (OD) and diffuse description (DD) type predominated in the control group; the opposite occurred in the intervention group, in which there was a predominance of more elaborate, reflective, and committed descriptions (RC) or emotional exploration (EE). This finding reflects the influence of the sensitization content on the intervention group, suggesting that the process of reflecting is a skill to be developed [ 13 ].

Each medical student newcomer to school brings with him or her a preconceived notion of expectations about the medical profession. However, his or her ability to reflect on professionalism changes according to the phase of his or her training cycle [ 28 ]. In the present study, we were able to measure that an isolated and well-structured pedagogical intervention was a tool that was capable of promoting an impact on the students’ view of professionalism. Nevertheless, we cannot assess the intensity and duration of this effect since multiple interventions are necessary to build the professional identity of future doctors.

In a systematic review on strategies for developing medical professionalism among future doctors, Passi et al. [ 8 ] noted that there are no clear guidelines on the most effective strategies to help medical students develop high levels of medical professionalism. The studies they selected identified five critical areas for this process: curriculum design, student selection, teaching/learning methods, mentoring (role modeling), and assessment methods. There is evidence that mentors and the hidden curriculum are more important for professional identity formation than formal activities such as conferences [ 4 ]. However, in our study, we demonstrated the impact of a single, formal activity on students’ values of the profession and capacity for self-reflection.

In conclusion, our study showed that medical students, upon entering medical school, already have an adequate view of medical professionalism, although they still need to present a deeper level of self-reflection. A program intervention in medical professionalism can promote self-reflection. The vision of medical professional identity was strongly influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, positively impacting the formation of a professional identity among the students who decided to enter medical school.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Cohen JJ. Professionalism in medical education, an American perspective: from evidence to accountability. Med Educ. 2006;40:607–17.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Johnson SE. Professionalism and medicine’s social contract. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:1189–94.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Brennan T, Blank L, Cohen J, Kimball H, Smeler N, Copeland R. Project of the ABIM Foundation, ACP–ASIM Foundation, and European Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:243–6.

Article Google Scholar

Lehmann LS, Sulmasy LS, Desai S, ACP Ethics, Professionalism and Human Rights Committee. Hidden curricula, ethics, and professionalism: optimizing clinical learning environments in becoming and being a physician: a position paper of the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168:506–8.

Cruess SR, Cruess RL. Understanding medical professionalism: a plea for an inclusive and integrated approach. Med Educ. 2008;42:755–7.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Steinert Y. Amending Miller’s pyramid to include professional identity formation. Acad Med. 2016;91:180–5.

Holden MD, Buck E, Luk J, Ambriz F, Boisaubin E, Clark M, et al. Professional identity formation: creating a longitudinal framework through TIME (transformation in medical education). Acad Med. 2015;90:761–7.

Passi V, Doug M, Peile E, Thistlethwaite J, Johnson N. Developing medical professionalism in future doctors: a systematic review. Int J Med Educ. 2010;1:19–29.

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Siqueira MAM, Torsani MB, Gameiro GR, Chinelatto LA, Mikahil BC, Tempski PZ, et al. Medical students’ participation in the Volunteering Program during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study about motivation and the development of new competencies. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:111.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tempski P, Arantes-Costa FM, Kobayasi R, Siqueira MAM, Torsani MB, Amaro BQRC et al. Medical students’ perceptions and motivations during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE. 2021: e0248627.

Frank JR, Snell L, Sherbino J, Boucher A. CanMEDS 2015. Physician competency framework series I. 2015.

Branch WT Jr. Use of critical incident reports in medical education, a perspective. J Gen Inter Med. 2005;20:1063–7.

Sandars J. The use of reflection in medical education: AMEE Guide 44. Med Teach. 2009;31:685–95.

Branch WT Jr., Pels RJ, Lawrence RS, Arky RA. Becoming a doctor: ‘‘critical-incident’’ reports from third-year medical students. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1330–2.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57.

Denzin NK. The research act: a theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1978.

Google Scholar

Denzin N, Lincoln YS. The landscape of qualitative research: theories and issues. 2ed ed. USA: Sage Publications Inc; 2003.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation and research methods. 2ed. London: SAGE Publications Inc; 1990.

Niemi PM. Medical student’ professional identity: self-reflection during the preclinical years. Med Educ. 1997;31:408–15.

Freire P. Pedagogy of hope: reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Bloomsbury Academic; 2012.

Knowles MS, Holton EF III, Swanson RA, Swanson S, Robinson PA. The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Taylor & Francis. London. 9th Edition. 2020.

Newman S, Vygotsky. Wittgenstein, and sociocultural theory. J Theory Soc Behav. 2018;48:350–68.

Charon R. Narrative Medicine: a model for empathy, reflection, profession and trust. JAMA. 2001;286:1897–908.

Mezirow J. Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco. Jossey-Bass,; 1991.

Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychol Bull. 1954;51:327.

Gardeshi Z, Amini M, Nabeiei P. The perception of hidden curriculum among undergraduate medical students: a qualitative study. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:271.

Cruess SR, Cruess RL, Steinert Y. Role modelling - making the most of a powerful teaching strategy. BMJ. 2008;336:718–21.

Reimer D, Russell R, Khallouq BB, Kauffman C, Hernandez C, Cendán J, et al. Pre-clerkship medical students’ perceptions of medical professionalism. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19:1–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cianciolo AT, Regehr G. Learning theory and educational intervention: producing meaningful evidence of impact through layered analysis. Acad Med. 2019;94:789–94.

World Health Organization Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. 2023. https://covid19.who.int/ . Acessed June 27, 2023.

Chinelatto LA, Costa TR, Medeiros VMB, Boog GHP, Hojaij FC, Tempski PZ, et al. What you gain and what you lose in COVID-19: perception of medical students on their education. Clinics. 2020;75:e2133.

Andersen RS, Hansen RP, Søndergaard J, Bro F. Learning based on patient case reviews: an interview study. BMC Med Educ. 2008;8:1–8.

Boenink AD, Oderwald AK, De Jonge P, Van Tilburg W, Smal JA. Assessing student reflection in medical practice. The development of an observer-rated instrument: reliability, validity and initial experiences. Med Educ. 2004;38:368–77.

Man K, Gordon J, MacLeod A. (2009). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: A systematic review. Adv Health Sci Educ. 2009; 14:595–621.

Plack MM, Driscoll M, Marquez M, Greenberg L. Peer-facilitated virtual action learning: reflecting on critical incidents during a pediatric clerkship. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10:146–52.

Montgomery A, Doulougeri K, Panagopoulou E. Do critical incidents lead to critical reflection among medical students? Health Psychol Behav. 2021;9:206–19.

Brady DW, Corbie-Smith G, Branch J, William T. What’s important to you? The use of narratives to promote self-reflection and to understand the experiences of medical residents. Ann Inter Med. 2002;137:220–3.

Download references

This study was supported by São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPQ), Brazil.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculdade de Medicina de Vassouras, Vassouras, Brazil

Sandra Vilagra, Marlon Vilagra & Lahis W. Vilagra

Centro de Desenvolvimento de Educação Médica, Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil

Renata Giaxa, Mariana Kehl, Milton A. Martins & Patricia Tempski

Universidade Federal de São Carlos, São Carlos, Brazil

Alice Miguel

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Study design: SV, MV, RG, AM, LWV, MAM, PT. Data collection: SV, MV. Data analysis: SV, MV, RG, AM, LWV, MK, MAM, PT. Writing of manuscript: SV, MV, MK, MAM, PT. Review and approval of manuscript: SV, MV, RG, AM, LWV, MK, MAM, PT.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Milton A. Martins .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The research ethics committee of the School of Medicine of the University of Sao Paulo approved this study (Protocol 56043522.9.0000.0068). Participation was voluntary, without compensation or incentives. We guaranteed confidentiality and anonymity. Data collection was performed in March 2022, on the first day of the medical program. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Vilagra, S., Vilagra, M., Giaxa, R. et al. Professional values at the beginning of medical school: a quasi-experimental study. BMC Med Educ 24 , 259 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05186-8

Download citation

Received : 16 August 2023

Accepted : 15 February 2024

Published : 08 March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-024-05186-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Critical incident

- Professionalism

- Professional identity

- Self-reflection

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Problem-based learning in American medical education: an overview

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Pathology, Mercer University School of Medicine, Macon, Georgia 31207.

- PMID: 8374585

- PMCID: PMC225793

The recent trend toward problem-based learning (PBL) in American medical education amounts to one of the most significant changes since the Flexner report motivated global university affiliation. In PBL, fundamental knowledge is mastered by the solving of problems, so basic information is learned in the same context in which it will be used. Also, the PBL curriculum employs student initiative as a driving force and supports a system of student-faculty interaction in which the student assumes primary responsibility for the process. The first PBL medical curriculum in North America was established at McMaster University in Toronto in 1969. The University of New Mexico was the first to adopt a medical PBL curriculum in the United States, and Mercer University School of Medicine in Georgia was the first U.S. medical school to employ PBL as its only curricular offering. Many interpretations of the basic PBL plan are in use in North American medical schools. Common features include small-group discussions of biomedical problems, a faculty role as facilitator, and the student's relative independence from scheduled lectures. The advantages of PBL are perceived as far outweighing its disadvantages, and the authors conclude that eventually it will see wider use at all levels of education.

Publication types

- Curriculum / trends

- Education, Medical / trends*

- Family Practice / education

- Forecasting

- Interprofessional Relations

- Preceptorship / trends

- Problem Solving*

- Programmed Instructions as Topic / trends*

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Learn more about the concept of Problem-Based Learning and how we incorporate the learning strategy into our medical school curriculum.

Background Problem-based learning (PBL) constructs a curriculum that merges theory and practice by employing clinical scenarios or real-world problems. Originally designed for the pre-clinical phase of undergraduate medicine, PBL has since been integrated into diverse aspects of medical education. Therefore, this study aims to map the global scientific landscape related to PBL in medical ...

Problem-based learning (PBL) emphasizes learning behavior that leads to critical thinking, problem-solving, communication, and collaborative skills in preparing students for a professional medical career. However, learning behavior that develops these skills has not been systematically described.

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a pedagogical approach that shifts the role of the teacher to the student (student-centered) and is based on self-directed learning. Although PBL has been adopted in undergraduate and postgraduate medical education, the effectiveness of the method is still under discussion.

Problem-based learning (PBL) has been a concept in existence for decades yet its implementation in medical student education is limited. Considering the nature of a physician's work, PBL is a logical step towards developing students' abilities to synthesize and integrate foundational concepts into clinical medicine.

The introduction of problem-based learning (PBL) in 1969 is considered the greatest innovation in medical education of the past 50 years. Since then, PBL has been implemented in different educational settings across virtually all health professions.

Problem based learning is used in many medical schools in the United Kingdom and worldwide. This article describes this method of learning and teaching in small groups and explains why it has had an important impact on medical education. The group learning process: acquiring desirable learning skills What is problem based learning?

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a widely used instructional method in medical education. It helps students integrate clinical and basic science knowledge as they address a patient's problem, facilitated by a faculty tutor in a small group setting. Barrows and Tamblyn ( 1980, p.

The medical school at the University of Manchester used PBL to improve undergraduate medical education and focused on community-based medical education 11. PBL was adopted after a rigorous and extensive assessment of the existing pedagogies at a new institution at the Mona campus to blend theory with practice and develop humanistic, community ...

1 Altmetric Explore all metrics Abstract Medical education strives to foster effective education of medical students despite an ever-changing landscape in medicine. This article explores the utility of projects in problem-based learning— project - PBL —as a way to supplement traditional case-PBL.

Problem-based learning (PBL) has been widely adopted in diverse fields and educational contexts to promote critical thinking and problem-solving in authentic learning situations. Its close affiliation with workplace collaboration and interdisciplinary learning contributed to its spread beyond the traditional realm of clinical education 1 to ...

Dean of Postgraduate Medical Education. Health Education North Central and East London, London, UK. ... Problem-based learning (PBL) can be characterized as an instructional method that uses patient problems as a context for students to acquire knowledge about the basic and clinical sciences. The basic outline of the PBL process is ...

Problem-based learning is an innovative and challenging approach to medical education--innovative because it is a new way of using clinical material to help students learn, and challenging because it requires the medical teacher to use facilitating and supporting skills rather than didactic, directi …

Problem based learning is used in many medical schools in the United Kingdom and worldwide. This article describes this method of learning and teaching in small groups and explains why it has had an important impact on medical education. Go to: What is problem based learning?

Problem-based learning (PBL) is an approach to education focused on skills development (Savery, 2006). In an effort to understand PBL's potential as a pedagogy, the first part of this article briefly reviews its use in medical schools, the arena of professional education in which PBL has its longest and most widespread use.