Recent developments in stress and anxiety research

- Published: 01 September 2021

- Volume 128 , pages 1265–1267, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

- Urs M. Nater 1 , 2

4893 Accesses

2 Citations

Explore all metrics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Stress and anxiety are virtually omnipresent in today´s society, pervading almost all aspects of our daily lives. While each and every one of us experiences “stress” and/or “anxiety” at least to some extent at times, the phenomena themselves are far from being completely understood. In stress research, scientists are particularly grappling with the conceptual issue of how to define stress, also with regard to delimiting stress from anxiety or negative affectivity in general. Interestingly, there is no unified theory of stress, despite many attempts at defining stress and its characteristics. Consequently, the available literature relies on a variety of different theoretical approaches, though the theories of Lazarus and Folkman ( 1984 ) or McEwen ( 1998 ) are relatively pervasive in the literature. One key issue in conceptualizing stress is that research has not always differentiated between the perception of a stimulus or a situation as a stressor and the subsequent biobehavioral response (often called the “stress response”). This is important, since, for example, psychological factors such as uncontrollability and social evaluation, i.e. factors that may influence how an individual perceives a potentially stressful stimulus or situation, have been identified as characteristics that elicit particularly powerful physiological stressful responses (Dickerson and Kemeny 2004 ). At the core of the physiological stress response is a complex physiological system, which is located in both the central nervous system (CNS) and the body´s periphery. The complexity of this system necessitates a multi-dimensional assessment approach involving variables that adequately reflect all relevant components. It is also important to consider that the experience of stress and its psychobiological correlates do not occur in a vacuum, but are being shaped by numerous contextual factors (e.g. societal and cultural context, work and leisure time, family and dyadic systems, environmental variables, physical fitness, nutritional status, etc.) and dispositional factors (e.g. genetics, personality, resilience, regulatory capacities, self-efficacy, etc.). Thus, a theoretical framework needs to incorporate these factors. In sum, as stress is considered a multi-faceted and inherently multi-dimensional construct, its conceptualization and operationalization needs to reflect this (Nater 2018 ).

The goal of the World Association for Stress Related and Anxiety Disorders (WASAD) is to promote and make available basic and clinical research on stress-related and anxiety disorders. Coinciding with WASAD’s 3rd International Congress held in September 2021 in Vienna, Austria, this journal publishes a Special Issue encompassing state-of-the art research in the field of stress and anxiety. This special issue collects answers to a number of important questions that need to be addressed in current and future research. Among the most relevant issues are (1) the multi-dimensional assessment that arises as a consequence of a multi-faceted consideration of stress and anxiety, with a particular focus on doing so under ecologically valid conditions. Skoluda et al. 2021 (in this issue) argue that hair as an important source of the stress hormone cortisol should not only be taken as a complementary stress biomarker by research staff, but that lay persons could be also trained to collect hair at the study participants’ homes, thus increasing the ecological validity of studies incorporating this important measure; (2) the incongruence between psychological and biological facets of stress and anxiety that has been observed both in laboratory and field research (Campbell and Ehlert 2012 ). Interestingly, there are behavioral constructs that do show relatively high congruence. As shown in the paper of Vatheuer et al. ( 2021 ), gaze behavior while exposed to an acute social stressor correlates with salivary cortisol, thus indicating common underlying mechanisms; (3) the complex dynamics of stress-related measures that may extend over shorter (seconds to minutes), medium (hours and diurnal/circadian fluctuations), and longer (months, seasonal) time periods. In particular, momentary assessment studies are highly qualified to examine short to medium term fluctuations and interactions. In their study employing such a design, Stoffel and colleagues (Stoffel et al. 2021 ) show ecologically valid evidence for direct attenuating effects of social interactions on psychobiological stress. Using an experimental approach, on the other hand, Denk et al. ( 2021 ) examined the phenomenon of physiological synchrony between study participants; they found both cortisol and alpha-amylase physiological synchrony in participants who were in the same group while being exposed to a stressor. Importantly, these processes also unfold over time in relation to other biological systems; al’Absi and colleagues showed in their study (al’Absi et al. 2021 ) the critical role of the endogenous opioid system and its relation to stress-related analgesia; (4) the influence of contextual and dispositional factors on the biological stress response in various target samples (e.g., humans, animals, minorities, children, employees, etc.) both under controlled laboratory conditions and in everyday life environments. In this issue, Sattler and colleagues show evidence that contextual information may only matter to a certain extent, as in their study (Sattler et al. 2021 ), the biological response to a gay-specific social stressor was equally pronounced as the one to a general social stressor in gay men. Genetic information is probably the most widely researched dispositional factor; Kuhn et al. show in their paper (Kuhn et al. 2021 ) that the low expression variant of the serotonin transporter gene serves as a risk factor for increased stress reactivity, thus clearly indicating the important role of dispositional factors in stress processing. An interesting factor combining both aspects of dispositional and contextual information is maternal care; Bentele et al. ( 2021 ) in their study are able to show that there was an effect of maternal care on the amylase stress response, while no such effect was observed for cortisol. In a similar vein, Keijser et al. ( 2021 ) showed in their gene-environment interaction study that the effects of FKBP5, a gene very closely related to HPA axis regulation, and early life stress on depressive symptoms among young adults was moderated by a positive parenting style; and (5) the role of stress and anxiety as transdiagnostic factors in mental disorders, be it as an etiological factor, a variable contributing to symptom maintenance, or as a consequence of the condition itself. Stress, e.g., as a common denominator for a broad variety of psychiatric diagnoses has been extensively discussed, and stress as an etiological factor holds specific significance in the context of transdiagnostic approaches to the conceptualization and treatment of mental disorders (Wilamowska et al. 2010 ). The HPA axis, specifically, is widely known to be dysregulated in various conditions. Fischer et al. ( 2021 ) discuss in their comprehensive review the role of this important stress system in the context of patients with post-traumatic disorder. Specifically focusing on the cortisol awakening response, Rausch and colleagues provide evidence for HPA axis dysregulation in patients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder (Rausch et al. 2021 ). As part of a longitudinal project on ADHD, Szep et al. ( 2021 ) investigated the possible impact of child and maternal ADHD symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol concentration; although there was no direct association, the findings underline the importance of taking stress-related assessments into consideration in ADHD studies. As the HPA axis is closely interacting with the immune system, Rhein et al. ( 2021 ) examined in their study the predicting role of the cytokine IL-6 on psychotherapy outcome in patients with PTSD, indicating that high reactivity of IL-6 to a stressor at the beginning of the therapy was associated with a negative therapy outcome. The review of Kyunghee Kim et al. ( 2021 ) also demonstrated the critical role of immune pathways in the molecular changes due to antidepressant treatment. As for the therapy, the important role of cognitive-behavioral therapy with its key elements to address both stress and anxiety reduction have been shown in two studies in this special issue, evidencing its successful application in obsessive–compulsive disorder (Ivarsson et al. 2021 ; Hollmann et al. 2021 ). Thus, both stress and anxiety are crucial transdiagnostic factors in various mental disorders, and future research needs elaborate further on their role in etiology, maintenance, and treatment.

In conclusion, a number of important questions are being asked in stress and anxiety research, as has become evident above. The Special Issue on “Recent developments in stress and anxiety research” attempts to answer at least some of the raised questions, and I want to invite you to inspect the individual papers briefly introduced above in more detail.

al’Absi M, Nakajima M, Bruehl S (2021) Stress and pain: modality-specific opioid mediation of stress-induced analgesia. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02401-4

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bentele UU, Meier M, Benz ABE, Denk BF, Dimitroff SJ, Pruessner JC, Unternaehrer E (2021) The impact of maternal care and blood glucose availability on the cortisol stress response in fasted women. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02350-y

Article Google Scholar

Campbell J, Ehlert U (2012) Acute psychosocial stress: does the emotional stress response correspond with physiological responses? Psychoneuroendocrinology 37(8):1111–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.010

Denk B, Dimitroff SJ, Meier M, Benz ABE, Bentele UU, Unternaehrer E, Popovic NF, Gaissmaier W, Pruessner JC (2021) Influence of stress on physiological synchrony in a stressful versus non-stressful group setting. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02384-2

Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME (2004) Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull 130(3):355–391

Fischer S, Schumacher T, Knaevelsrud C, Ehlert U, Schumacher S (2021) Genes and hormones of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in post-traumatic stress disorder. What is their role in symptom expression and treatment response? J Neural Transm (vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02330-2

Hollmann K, Allgaier K, Hohnecker CS, Lautenbacher H, Bizu V, Nickola M, Wewetzer G, Wewetzer C, Ivarsson T, Skokauskas N, Wolters LH, Skarphedinsson G, Weidle B, de Haan E, Torp NC, Compton SN, Calvo R, Lera-Miguel S, Haigis A, Renner TJ, Conzelmann A (2021) Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy in children and adolescents with obsessive compulsive disorder: a feasibility study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02409-w

Ivarsson T, Melin K, Carlsson A, Ljungberg M, Forssell-Aronsson E, Starck G, Skarphedinsson G (2021) Neurochemical properties measured by 1 H magnetic resonance spectroscopy may predict cognitive behaviour therapy outcome in paediatric OCD: a pilot study. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02407-y

Keijser R, Olofsdotter S, Nilsson WK, Åslund C (2021) Three-way interaction effects of early life stress, positive parenting and FKBP5 in the development of depressive symptoms in a general population. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02405-0

Kuhn L, Noack H, Skoluda N, Wagels L, Rohr AK, Schulte C, Eisenkolb S, Nieratschker V, Derntl B, Habel U (2021) The association of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism and the response to different stressors in healthy males. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02390-4

Kyunghee Kim H, Zai G, Hennings J, Müller DJ, Kloiber S (2021) Changes in RNA expression levels during antidepressant treatment: a systematic review. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02394-0

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publisher Company Inc, New York

Google Scholar

McEwen BS (1998) Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. N Engl J Med 338(3):171–179

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nater UM (2018) The multidimensionality of stress and its assessment. Brain Behav Immun 73:159–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2018.07.018

Rausch J, Flach E, Panizza A, Brunner R, Herpertz SC, Kaess M, Bertsch K (2021) Associations between age and cortisol awakening response in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Neural Transm. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02402-3

Rhein C, Hepp T, Kraus O, von Majewski K, Lieb M, Rohleder N, Erim Y (2021) Interleukin-6 secretion upon acute psychosocial stress as a potential predictor of psychotherapy outcome in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02346-8

Sattler FA, Nater UM, Mewes R (2021) Gay men’s stress response to a general and a specific social stressor. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02380-6

Skoluda N, Piroth I, Gao W, Nater UM (2021) HOME vs. LAB hair samples for the determination of long-term steroid concentrations: a comparison between hair samples collected by laypersons and trained research staff. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02367-3

Stoffel M, Abbruzzese E, Rahn S, Bossmann U, Moessner M, Ditzen B (2021) Covariation of psychobiological stress regulation with valence and quantity of social interactions in everyday life: disentangling intra- and interindividual sources of variation. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02359-3

Szep A, Skoluda N, Schloss S, Becker K, Pauli-Pott U, Nater UM (2021) The impact of preschool child and maternal attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms on mothers’ perceived chronic stress and hair cortisol. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02377-1

Vatheuer CC, Vehlen A, von Dawans B, Domes G (2021) Gaze behavior is associated with the cortisol response to acute psychosocial stress in the virtual TSST. J Neural Transm (Vienna). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02344-w

Wilamowska ZA, Thompson-Hollands J, Fairholme CP, Ellard KK, Farchione TJ, Barlow DH (2010) Conceptual background, development, and preliminary data from the unified protocol for transdiagnostic treatment of emotional disorders. Depress Anxiety 27(10):882–890. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20735

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Clinical and Health Psychology, Faculty of Psychology, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

Urs M. Nater

University Research Platform ‘The Stress of Life – Processes and Mechanisms Underlying Everyday Life Stress’, University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Urs M. Nater .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Nater, U.M. Recent developments in stress and anxiety research. J Neural Transm 128 , 1265–1267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Download citation

Accepted : 13 August 2021

Published : 01 September 2021

Issue Date : September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-021-02410-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Stress and Health: A Review of Psychobiological Processes

Affiliations.

- 1 School of Psychology, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- 2 Department of Psychological Science, School of Social Ecology, University of California, Irvine, California 92697, USA; email: [email protected].

- 3 Division of Primary Care, School of Medicine, University of Nottingham, Nottingham NG7 2UH, United Kingdom; email: [email protected].

- PMID: 32886587

- DOI: 10.1146/annurev-psych-062520-122331

The cumulative science linking stress to negative health outcomes is vast. Stress can affect health directly, through autonomic and neuroendocrine responses, but also indirectly, through changes in health behaviors. In this review, we present a brief overview of ( a ) why we should be interested in stress in the context of health; ( b ) the stress response and allostatic load; ( c ) some of the key biological mechanisms through which stress impacts health, such as by influencing hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis regulation and cortisol dynamics, the autonomic nervous system, and gene expression; and ( d ) evidence of the clinical relevance of stress, exemplified through the risk of infectious diseases. The studies reviewed in this article confirm that stress has an impact on multiple biological systems. Future work ought to consider further the importance of early-life adversity and continue to explore how different biological systems interact in the context of stress and health processes.

Keywords: HPA axis; allostatic load; autonomic nervous system; cortisol; genomics.

Publication types

- Autonomic Nervous System / metabolism

- Hydrocortisone / metabolism

- Hypothalamo-Hypophyseal System / metabolism

- Pituitary-Adrenal System / metabolism

- Stress, Psychological / metabolism*

- Hydrocortisone

- Research Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 April 2021

Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19

- Szabolcs Garbóczy 1 , 2 ,

- Anita Szemán-Nagy 3 ,

- Mohamed S. Ahmad 4 ,

- Szilvia Harsányi 1 ,

- Dorottya Ocsenás 5 , 6 ,

- Viktor Rekenyi 4 ,

- Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi 1 , 7 &

- László Róbert Kolozsvári ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9426-0898 1 , 7

BMC Psychology volume 9 , Article number: 53 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

15k Accesses

41 Citations

Metrics details

In the case of people who carry an increased number of anxiety traits and maladaptive coping strategies, psychosocial stressors may further increase the level of perceived stress they experience. In our research study, we aimed to examine the levels of perceived stress and health anxiety as well as coping styles among university students amid the COVID-19 pandemic.

A cross-sectional study was conducted using an online-based survey at the University of Debrecen during the official lockdown in Hungary when dormitories were closed, and teaching was conducted remotely. Our questionnaire solicited data using three assessment tools, namely, the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), the Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ), and the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI).

A total of 1320 students have participated in our study and 31 non-eligible responses were excluded. Among the remaining 1289 participants, 948 (73.5%) and 341 (26.5%) were Hungarian and international students, respectively. Female students predominated the overall sample with 920 participants (71.4%). In general, there was a statistically significant positive relationship between perceived stress and health anxiety. Health anxiety and perceived stress levels were significantly higher among international students compared to domestic ones. Regarding coping, wishful thinking was associated with higher levels of stress and anxiety among international students, while being a goal-oriented person acted the opposite way. Among the domestic students, cognitive restructuring as a coping strategy was associated with lower levels of stress and anxiety. Concerning health anxiety, female students (domestic and international) had significantly higher levels of health anxiety compared to males. Moreover, female students had significantly higher levels of perceived stress compared to males in the international group, however, there was no significant difference in perceived stress between males and females in the domestic group.

The elevated perceived stress levels during major life events can be further deepened by disengagement from home (being away/abroad from country or family) and by using inadequate coping strategies. By following and adhering to the international recommendations, adopting proper coping methods, and equipping oneself with the required coping and stress management skills, the associated high levels of perceived stress and anxiety could be mitigated.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

On March 4, 2020, the first cases of coronavirus disease were declared in Hungary. One week later, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 as a global pandemic [ 1 ]. The Hungarian government ordered a ban on outdoor public events with more than 500 people and indoor events with more than 100 participants to reduce contact between people [ 2 ]. On March 27, the government imposed a nationwide lockdown for two weeks effective from March 28, to mitigate the spread of the pandemic. Except for food stores, drug stores, pharmacies, and petrol stations, all other shops and educational institutions remained closed. On April 16, a week-long extension was further announced [ 3 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic with its high morbidity and mortality has already afflicted the psychological and physical wellbeing of humans worldwide [ 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. During major life events, people may have to deal with more stress. Stress can negatively affect the population’s well-being or function when they construe the situation as stressful and they cannot handle the environmental stimuli [ 10 ]. Various inter-related and inter-linked concepts are present in such situations including stress, anxiety, and coping. According to the literature, perceived stress can lead to higher levels of anxiety and lower levels of health-related quality of life [ 11 ]. Another study found significant and consistent associations between coping strategies and the dimensions of health anxiety [ 12 ].

Health anxiety is one of the most common types of anxiety and it describes how people think and behave toward their health and how they perceive any health-related concerns or threats. Health anxiety is increasingly conceptualized as existing on a spectrum [ 13 , 14 ], and as an adaptive signal that helps to develop survival-oriented behaviors. It also occurs in almost everyone’s life to a certain degree and can be rather deleterious when it is excessive [ 13 , 14 ]. Illness anxiety or hypochondriasis is on the high end of the spectrum and it affects someone’s life when it interferes with daily life by making people misinterpret the somatic sensations, leading them to think that they have an underlying condition [ 14 ].

According to the American Psychiatric Association—Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fifth edition), Illness anxiety disorder is described as a preoccupation with acquiring or having a serious illness, and it reflects the high spectrum of health anxiety [ 15 ]. Somatic symptoms are not present or if they are, then only mild in intensity. The preoccupation is disproportionate or excessive if there is a high risk of developing a medical condition (e.g., family history) or the patient has another medical condition. Excessive health-related behaviors can be observed (e.g., checking body for signs of illness) and individuals can show maladaptive avoidance as well by avoiding hospitals and doctor appointments [ 15 ].

Health anxiety is indeed an important topic as both its increase and decrease can progress to problems [ 14 ]. Looking at health anxiety as a wide spectrum, it can be high or low [ 16 ]. While people with a higher degree of worry and checking behaviors may cause some burden on healthcare facilities by visiting them too many times (e.g., frequent unnecessary visits), other individuals may not seek medical help at healthcare units to avoid catching up infections for instance. A lower degree of health anxiety can lead to low compliance with imposed regulations made to control a pandemic [ 17 ].

The COVID-19 pandemic as a major event in almost everyone’s life has posed a great impact on the population’s perceived stress level. Several studies about the relation between coping and response to epidemics in recent and previous outbreaks found higher perceived stress levels among people [ 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 ]. Being a woman, low income, and living with other people all were associated with higher stress levels [ 18 ]. Protective factors like being emotionally more stable, having self-control, adaptive coping strategies, and internal locus of control were also addressed [ 19 , 20 ]. The findings indicated that the COVID-19 crisis is perceived as a stressful event. The perceived stress was higher amongst people than it was in situations with no emergency. Nervousness, stress, and loss of control of one’s life are the factors that are most connected to perceived stress levels which leads to the suggestion that unpredictability and uncontrollability take an important part in perceived stress during a crisis [ 19 , 20 ].

Moreover, certain coping styles (e.g., having a positive attitude) were associated with less psychological distress experiences but avoidance strategies were more likely to cause higher levels of stress [ 21 ]. According to Lazarus (1999), individuals differ in their perception of stress if the stress response is viewed as the interaction between the environment and humans [ 22 ]. An Individual can experience two kinds of evaluation processes, one to appraise the external stressors and personal stake, and the other one to appraise personal resources that can be used to cope with stressors [ 22 , 23 ]. If there is an imbalance between these two evaluation processes, then stress occurs, because the personal resources are not enough to cope with the stressor’s demands [ 23 ].

During stressful life events, it is important to pay attention to the increasing levels of health anxiety and to the kind of coping mechanisms that are potential factors to mitigate the effects of high anxiety. The transactional model of stress by Lazarus and Folkman (1987) provides an insight into these kinds of factors [ 24 ]. Lazarus and Folkman theorized two types of coping responses: emotion-focused coping, and problem-focused coping. Emotion-focused coping strategies (e.g., distancing, acceptance of responsibility, positive reappraisal) might be used when the source of stress is not embedded in the person’s control and these strategies aim to manage the individual’s emotional response to a threat. Also, emotion-focused coping strategies are directed at managing emotional distress [ 24 ]. On the other hand, problem-focused coping strategies (e.g., confrontive coping, seeking social support, planful problem-solving) help an individual to be able to endure and/or minimize the threat, targeting the causes of stress in practical ways [ 24 ]. It was also addressed that emotion-focused coping mechanisms were used more in situations appraised as requiring acceptance, whereas problem-focused forms of coping were used more in encounters assessed as changeable [ 24 ].

A recent study in Hunan province in China found that the most effective factor in coping with stress among medical staff was the knowledge of their family’s well-being [ 25 ]. Although there have been several studies about the mental health of hospital workers during the COVID-19 pandemic or other epidemics (e.g., SARS, MERS) [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ], only a few studies from recent literature assessed the general population’s coping strategies. According to Gerhold (2020) [ 30 ], older people perceived a lower risk of COVID-19 than younger people. Also, women have expressed more worries about the disease than men did. Coping strategies were highly problem-focused and most of the participants reported that they listen to professionals’ advice and tried to remain calm [ 30 ]. In the same study, most responders perceived the COVID-19 pandemic as a global catastrophe that will severely affect a lot of people. On the other hand, they perceived the pandemic as a controllable risk that can be reduced. Dealing with macrosocial stressors takes faith in politics and in those people, who work with COVID-19 on the frontline.

Mental disorders are found prevalent among college students and their onset occurs mostly before entry to college [ 31 ]. The diagnosis and timely interventions at an early stage of illness are essential to improve psychosocial functioning and treatment outcomes [ 31 ]. According to research that was conducted at the University of Debrecen in Hungary a few years ago, the students were found to have high levels of stress and the rate of the participants with impacted mental health was alarming [ 32 ]. With an unprecedented stressful event like the COVID-19 crisis, changes to the mental health status of people, including students, are expected.

Aims of the study

In our present study, we aimed at assessing the levels of health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles among university students amidst the COVID-19 lockdown in Hungary, using three validated assessment tools for each domain.

Methods and materials

Study design and setting.

This study utilized a cross-sectional design, using online self-administered questionnaires that were created and designed in Google Forms® (A web-based survey tool). Data collection was carried out in the period April 30, 2020, and May 15, 2020, which represents one of the most stressful periods during the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic in Hungary when the official curfew/lockdown was declared along with the closure of dormitories and shifting to online remote teaching. The first cases of COVID-19 were declared in Hungary on March 4, 2020. On April 30, 2020, there were 2775 confirmed cases, 312 deaths, and 581 recoveries. As of May 15, 2020, the number of confirmed cases, deaths, and recovered persons was 3417, 442, and 1287, respectively.

Our study was conducted at the University of Debrecen, which is one of the largest higher education institutions in Hungary. The University is located in the city of Debrecen, the second-largest city in Hungary. Debrecen city is considered the educational and cultural hub of Eastern Hungary. As of October 2019, around 28,593 students were enrolled in various study programs at the University of Debrecen, of whom, 6,297 were international students [ 33 ]. The university offers various degree courses in Hungarian and English languages.

Study participants and sampling

The target population of our study was students at the University of Debrecen. Students were approached through social media platforms (e.g., Facebook®) and the official student administration system at the University of Debrecen (Neptun). The invitation link to our survey was sent to students on the web-based platforms described earlier. By using the Neptun system, we theoretically assumed that our survey questionnaire has reached all students at the University. The students who were interested and willing to participate in the study could fill out our questionnaire anonymously during the determined study period; thus, employing a convenience sampling approach. All students at the University of Debrecen whose age was 18 years or older and who were in Hungary during the outbreak had the eligibility to participate in our study whether undergraduates or postgraduates.

Study instruments

In our present study, the survey has solicited information about the sociodemographic profile of participants including age (in years), gender (female vs male), study program (health-related vs non-health related), and whether the student stayed in Hungary or traveled abroad during the period of conducting our survey in the outbreak. Our survey has also adopted three international scales to collect data about health anxiety, coping styles, and perceived stress during the pandemic crisis. As the language of instruction for international students at the University of Debrecen is English, and English fluency is one of the criteria for international students’ admission at the University of Debrecen, the international students were asked to fill out the English version of the survey and the scales. On the other hand, the Hungarian students were asked to fill out the Hungarian version of the survey and the validated Hungarian scales. Also, we provided contact information for psychological support when needed. Students who felt that they needed some help and psychological counseling could use the contact information of our peer supporters. Four International students have used this opportunity and were referred to a higher level of care. The original scales and their validated Hungarian versions are described in the following sections.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS)

The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) measures the level of stress in the general population who have at least completed a junior high school [ 34 ]. In the PSS, the respondents had to report how often certain things occurred like nervousness; loss of control; feeling of upset; piling up difficulties that cannot be handled; or on the contrary how often the students felt they were able to handle situations; and were on top of things. For the International students, we used the 10-item PSS (English version). The statements’ responses were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 = never to 4 = very often) as per the scale’s guide. Also, in the 10-item PSS, four positive items were reversely scored (e.g. felt confident about someone’s ability to handle personal problems) [ 34 ]. The PSS has satisfactory psychometric properties with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.78, and this English version was used for international students in our study.

For the Hungarian students, we used the Hungarian version of the PSS, which has 14 statements that cover the same aspects of stress described earlier. In this version of the PSS, the responses were evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale (0–4) to mark how typical a particular behavior was for a respondent in the last month [ 35 ]. The Hungarian version of the PSS was psychometrically validated in 2006. In the validation study, the Hungarian 14-item PSS has shown satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88 [ 35 ].

Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ)

The second scale we used was the 26-Item Ways of Coping Questionnaire (WCQ) which was developed by Sørlie and Sexton [ 36 ]. For the international students, we used the validated English version of the 26-Item WCQ that distinguished five different factors, including Wishful thinking (hoped for a miracle, day-dreamed for a better time), Goal-oriented (tried to analyze the problem, concentrated on what to do), Seeking support (talked to someone, got professional help), Thinking it over (drew on past experiences, realized other solutions), and Avoidance (refused to think about it, minimized seriousness of it). The WCQ examined how often the respondents used certain coping mechanisms, eg: hoped for a miracle, fantasized, prepared for the worst, analyzed the problem, talked to someone, or on the opposite did not talk to anyone, drew conclusions from past things, came up with several solutions for a problem or contained their feelings. As per the 26-item WCQ, responses were scored on a 4-point Likert scale (from 0 = “does not apply and/or not used” to 3 = “used a great deal”). This scale has satisfactory psychometric properties with Cronbach's alpha for the factors ranged from 0.74 to 0.81[ 36 ].

For the Hungarian students, we used the Hungarian 16-Item WCQ, which was validated in 2008 [ 37 ]. In the Hungarian WCQ, four dimensions were identified, which were cognitive restructuring/adaptation (every cloud has a silver lining), Stress reduction (by eating; drinking; smoking), Problem analysis (I tried to analyze the problem), and Helplessness/Passive coping (I prayed; used drugs) [ 37 ]. The Cronbach’s alpha values for the Hungarian WCQ’s dimensions were in the range of 0.30–0.74 [ 37 ].

Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI)

The third scale adopted was the 18-Items Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI). Overall, the SHAI has two subscales. The first subscale comprised of 14 items that examined to what degree the respondents were worried about their health in the past six months; how often they noticed physical pain/ache or sensations; how worried they were about a serious illness; how much they felt at risk for a serious illness; how much attention was drawn to bodily sensations; what their environment said, how much they deal with their health. The second subscale of SHAI comprised of 4 items (negative consequences if the illness occurs) that enquired how the respondents would feel if they were diagnosed with a serious illness, whether they would be able to enjoy things; would they trust modern medicine to heal them; how many aspects of their life it would affect; how much they could preserve their dignity despite the illness [ 38 ]. One of four possible statements (scored from 0 to 3) must be chosen. Alberts et al. (2013) [ 39 ] found the mean SHAI value to be 12.41 (± 6.81) in a non-clinical sample. The original 18-item SHAI has Cronbach’s alpha values in the range of 0.74–0.96 [ 39 ]. For the Hungarian students, the Hungarian version of the SHAI was used. The Hungarian version of SHAI was validated in 2011 [ 40 ]. The scoring differs from the English version in that the four statements were scored from 1 to 4, but the statements themselves were the same. In the Hungarian validation study, it was found that the SHAI mean score in a non-clinical sample (university students) was 33.02 points (± 6.28) and the Cronbach's alpha of the test was 0.83 [ 40 ].

Data analyses

Data were extracted from Google Forms® as an Excel sheet for quality check and coding then we used SPSS® (v.25) and RStudio statistical software packages to analyze the data. Descriptive and summary statistics were presented as appropriate. To assess the difference between groups/categories of anxiety, stress, and coping styles, we used the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, since the variables did not have a normal distribution and for post hoc tests, we used the Mann–Whitney test. Also, we used Spearman’s rank correlation to assess the relationship between health anxiety and perceived stress within the international group and the Hungarian group. Comparison between international and domestic groups and different genders in terms of health anxiety and perceived stress levels were also conducted using the Mann–Whitney test. Binary logistic regression analysis was also employed to examine the associations between different coping styles/ strategies (treated as independent variables) and both, health anxiety level and perceived stress level (treated as outcome variables) using median splits. A p-value less than 5% was implemented for statistical significance.

Ethical considerations

Ethical permission was obtained from the Hungarian Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology (Reference number: 2020-45). All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines and conforming to the ethical standards of the declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed about the study and written informed consent was obtained before completing the survey. There were no rewards/incentives for completing the survey.

Sociodemographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 1320 students have responded to our survey. Six responses were eliminated due to incompleteness and an additional 25 responses were also excluded as the students filled out the survey from abroad (International students who were outside Hungary during the period of conducting our study). After exclusion of the described non-eligible responses (a total of 31 responses), the remaining 1289 valid responses were included in our analysis. Out of 1289 participants (100%), 73.5% were Hungarian students and around 26.5% were international students. Overall, female students have predominated the sample (n = 920, 71.4%). The median age (Interquartile range) among Hungarian students was 22 years (5) and for the international students was 22 years (4). Out of the total sample, most of the Hungarian students were enrolled in non-health-related programs (n = 690, 53.5%), while most of the international students were enrolled in health-related programs (n = 213, 16.5%). Table 1 demonstrates the sociodemographic profile of participants (Hungarian vs International).

Perceived stress, anxiety, and coping styles

For greater clarity of statistical analysis and interpretation, we created preferences regarding coping mechanisms. That is, we made the categories based on which coping factor (in the international sample) or dimension (in the Hungarian sample) the given person reached the highest scores, so it can be said that it is the person's preferred coping strategy. The four coping strategies among international students were goal-oriented, thinking it over, wishful thinking, and avoidance, while among the Hungarian students were cognitive restructuring, problem analysis, stress reduction, and passive coping.

The 26-item WCQ [ 31 ] contains a seeking support subscale which is missing from the Hungarian 16-item WCQ [ 32 ]; therefore, the seeking support subscale was excluded from our analysis. Moreover, because the PSS contained a different number of items in English and Hungarian versions (10 items vs 14 items), we looked at the average score of the answers so that we could compare international and domestic students.

In the evaluation of SHAI, the scoring of the two questionnaires are different. For the sake of comparability between the two samples, the international points were corrected to the Hungarian, adding plus one to the value of each answer. This may be the reason why we obtained higher results compared to international standards.

Among the international students, the mean score (± standard deviation) of perceived stress among male students was 2.11(± 0.86) compared to female students 2.51 (± 0.78), while the mean score (± standard deviation) of health anxiety was 34.12 (± 7.88) and 36.31 (± 7.75) among males and females, respectively. Table 2 shows more details regarding the perceived stress scores and health anxiety scores stratified by coping strategies among international students.

In the Hungarian sample, the mean score (± standard deviation) of perceived stress among male students was 2.06 (± 0.84) compared to female students 2.18 (± 0.83), while the mean score (± standard deviation) of health anxiety was 33.40 (± 7.63) and 35.05 (± 7.39) among males and females, respectively. Table 3 shows more details regarding the perceived stress scores and health anxiety scores stratified by coping strategies among Hungarian students.

Concerning coping styles among international students, the statements with the highest-ranked responses were “wished the situation would go away or somehow be finished” and “Had fantasies or wishes about how things might turn out” and both fall into the wishful thinking coping. Among the Hungarian students, the statements with the highest-ranked responses were “I tried to analyze the problem to understand better” (falls into problem analysis coping) and “I thought every cloud has a silver lining, I tried to perceive things cheerfully” (falls into cognitive restructuring coping).

On the other hand, the statements with the least-ranked responses among the international students belonged to the Avoidance coping. Among the Hungarians, it was Passive coping “I tried to take sedatives or medications” and Stress reduction “I staked everything upon a single cast, I started to do something risky” to have the lowest-ranked responses. Table 4 shows a comparison of different coping strategies among international and Hungarian students.

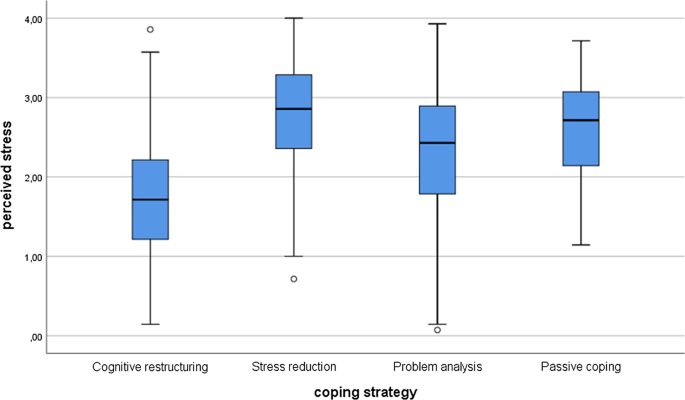

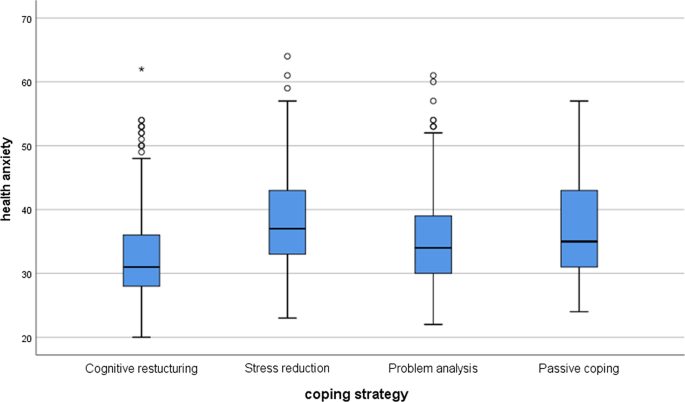

To test the difference between coping strategies, we used the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis test, since the variables did not have a normal distribution. For post hoc tests, we used Mann–Whitney tests with lowered significance levels ( p = 0.0083). Among Hungarian students, there were significant differences between the groups in stress ( χ 2 (3) = 212.01; p < 0.001) and health anxiety ( χ 2 (3) = 80.32; p < 0.001). In the post hoc tests, there were significant differences everywhere ( p < 0.001) except between stress reduction and passive coping ( p = 0.089) and between problem analysis and passive coping ( p = 0.034). Considering the health anxiety, the results were very similar. There were significant differences between all groups ( p < 0.001), except between stress reduction and passive coping ( p = 0.347) and between problem analysis and passive coping ( p = 0.205). See Figs. 1 and 2 for the Hungarian students.

Perceived stress differences between coping strategies among the Hungarian students

Health anxiety differences between coping strategies among the Hungarian students

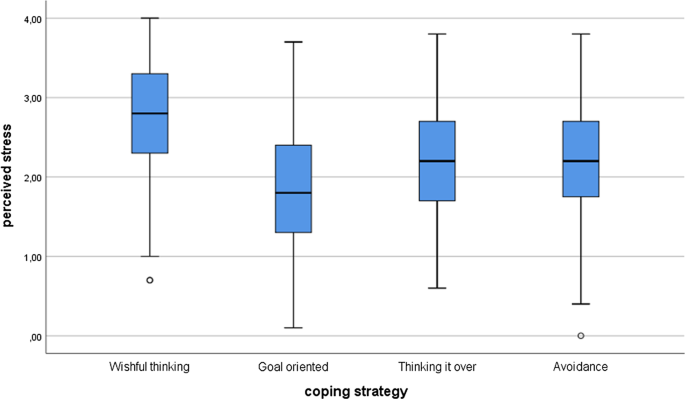

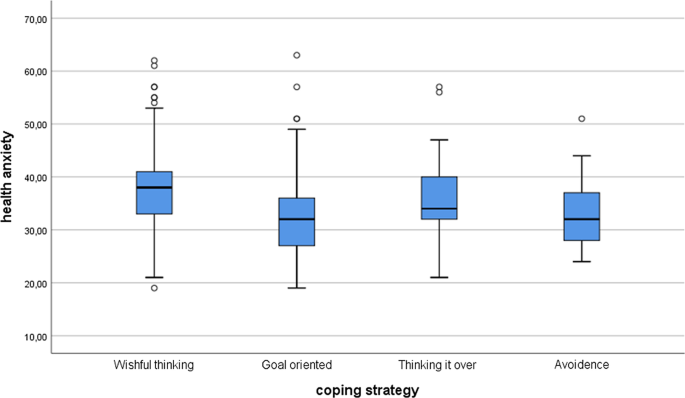

Among the international students, the results were similar. According to the Kruskal–Wallis test, there were significant differences in stress ( χ 2 (3) = 73.26; p < 0.001) and health anxiety ( χ 2 (3) = 42.60; p < 0.001) between various coping strategies. The post hoc tests showed that there were differences between the perceived stress level and coping strategies everywhere ( p < 0.005) except and between avoidance and thinking it over ( p = 0.640). Concerning health anxiety, there were significant differences between wishful thinking and goal-oriented ( p < 0.001), between wishful thinking and avoidance ( p = 0.001), and between goal-oriented and avoidance ( p = 0.285). There were no significant differences between wishful thinking and thinking it over ( p = 0.069), between goal-oriented and thinking it over ( p = 0.069), and between avoidance and thinking it over ( p = 0.131). See Figs. 3 and 4 .

Perceived stress differences between coping strategies among the international students

Health anxiety differences between coping strategies among the international students

The relationship between coping strategies with health anxiety and perceived stress levels among the international students

We applied logistic regression analyses for the variables to see which of the coping strategies has a significant effect on SHAI and PSS results. In the first model (model a), with the health anxiety as an outcome dummy variable (with median split; median: 35), only two coping strategies had a statistically significant relationship with health anxiety level, including wishful thinking (as a risk factor) and goal-oriented (as a protective factor).

In the second model (model b), with the perceived stress as an outcome dummy variable (with median split; median: 2.40), three coping strategies were found to have a statistically significant association with the level of perceived stress, including wishful thinking (as a risk factor), while goal-oriented and thinking it over as protective factors. See Table 5 .

The relationship between coping strategies with health anxiety and perceived stress levels among domestic students

By employing logistic regression analysis, with the health anxiety as an outcome dummy variable (with median split; median: 33.5) (model a), three coping strategies had a statistically significant relationship with health anxiety level among domestic students, including stress reduction and problem analysis (as risk factors), while cognitive restructuring (as a protective factor).

Similarly, with the perceived stress as an outcome dummy variable (with median split; median: 2.1429) (model b), three coping strategies had a statistically significant relationship with perceived stress level, including stress reduction and problem analysis (as risk factors), while cognitive restructuring (as a protective factor). See Table 6 .

Comparisons between domestic and international students

We compared health anxiety and perceived stress levels of the Hungarian and international students’ groups using the Mann–Whitney test. In the case of health anxiety, the results showed that there were significant differences between the two groups ( W = 149,431; p = 0.038) and international students’ levels were higher. Also, there was a significant difference in the perceived stress level between the two groups ( W = 141,024; p < 0.001), and the international students have increased stress levels compared to the Hungarian ones.

Comparisons between genders within students’ groups (International vs Hungarian)

Firstly, we compared the international men’s and women’s health anxiety and stress levels using the Mann–Whitney test. The results showed that the international women’s health anxiety ( W = 11,810; p = 0.012) and perceived stress ( W = 10,371; p < 0.001) levels were both significantly higher than international men’s values. However, in the Hungarian sample, women’s health anxiety was significantly higher than men’s ( W = 69,643; p < 0.001), but there was no significant difference in perceived stress levels among between Hungarian women and men ( W = 75,644.5; p = 0.064).

Relationship between health anxiety and perceived stress

We correlated the general health anxiety and perceived stress using Spearman’s rank correlation. There was a significant moderate positive relationship between the two variables ( p < 0.001; ρ = 0.446). Within the Hungarian students, there was a significant correlation between health anxiety and perceived stress ( p < 0.001; ρ = 0.433), similarly among international students as well ( p < 0.001; ρ = 0.465).

In our study, we found that individuals who were characterized by a preference for certain coping strategies reported significantly higher perceived stress and/or health anxiety than those who used other coping methods. These correlations can be found in both the Hungarian and international students. In the light of our results, we can say that 48.4% of the international students used wishful thinking as their preferred coping method while around 43% of the Hungarian students used primarily cognitive restructuring to overcome their problems.

Regulation of emotion refers to “the processes whereby individuals monitor, evaluate, and modify their emotions in an effort to control which emotions they have, when they have them, and how they experience and express those emotions” [ 41 ]. There is an overlap between emotion-focused coping and emotion regulation strategies, but there are also differences. The overlap between the two concepts can be noticed in the fact that emotion-focused coping strategies have an emotional regulatory role, and emotion regulation strategies may “tax the individual’s resources” as the emotion-focused coping strategies do [ 23 , 42 ]. However, in emotion-focused coping strategies, non-emotional tools can also be used to achieve non-emotional goals, while emotion regulation strategies may be used for maintaining or reinforcing positive emotions [ 42 ].

Based on the cognitive-behavioral model of health anxiety, emotion-regulating strategies can regulate the physiological, cognitive, and behavioral consequences of a fear response to some degree, even when the person encounters the conditioned stimulus again [ 12 , 43 ]. In the long run, regular use of these dysfunctional emotion control strategies may manifest as functional impairment, which may be associated with anxiety disorders. A detailed study that examined health anxiety in the view of the cognitive-behavioral model found that, regardless of the effect of depression, there are significant and consistent correlations between certain dimensions of health anxiety and dysfunctional coping and emotional regulation strategies [ 12 ].

Similar to our current study, other studies have found that health anxiety was positively correlated with maladaptive emotion regulation and negatively with adaptive emotion regulation [ 44 ], and in the case of state anxiety that emotion-focused coping strategies proved to be less effective in reducing stress, while active coping leads to a sense of subjective well-being [ 17 , 27 , 45 , 46 , 47 ]

SHAI values were found to be high in other studies during the pandemic, and the SHAI results of the international students in our study were found to be even slightly higher compared to those studies [ 44 , 48 ]. Besides, anxiety values for women were found to be higher than for men in several studies [ 44 , 48 , 49 , 50 ]. This was similar to what we found among the international students but not among the Hungarian ones. We can speculate that the ability to contact someone, the closeness of family and beloved ones, familiarity with the living environment, and maybe less online search about the coronavirus news could be factors counting towards that finding among Hungarian students. Also, most international students were enrolled in health-related study programs and his might have affected how they perceived stress/anxiety and their preferred coping strategies as well. Literature found that students of medical disciplines could have obstacles in achieving a healthy coping strategy to deal with stress and anxiety despite their profound medical knowledge compared to non-health-related students [ 51 , 52 ]. Literature also stressed the immense need for training programs to help students of medical disciplines in adopting coping skills and stress-reducing strategies [ 51 ].

The findings of our study may be a starting point for the exploration of the linkage between perceived stress, health anxiety, and coping strategies when people are not in their domestic context. People who are away from their home and friends in a relatively alien environment may tend to use coping mechanisms other than the adequate ones, which in turn can lead to increased levels of perceived stress.

Furthermore, our results seem to support the knowledge that deep-rooted health anxiety is difficult to change because it is closely related to certain coping mechanisms. It was also addressed in the literature that personality traits may have a significant influence on the coping strategy used by a person [ 53 ], revealing sophisticated and challenging links to be considered especially during training programs on effective coping and management skills. On the other hand, perceived stress which has risen significantly above the average level in the current pandemic, can be most effectively targeted by the well-formulated recommendations and advice of major international health organizations if people successfully adhere to them (e.g. physical activity; proper and adequate sleep; healthy eating; avoiding alcohol; meditation; caring for others; relationships maintenance, and using credible information resources about the pandemic, etc.) [ 1 , 54 ]. Furthermore, there may be additional positive effects of these recommendations when published in different languages or languages that are spoken by a wide range of nationalities. Besides, cognitive behavioral therapy techniques, some of which are available online during the current pandemic crisis, can further reduce anxiety. Also, if someone does not feel safe or fear prevails, there are helplines to get in touch with professionals, and this applies to the University of Debrecen in Hungary, and to a certain extent internationally.

Naturally, our study had certain limitations that should be acknowledged and considered. The temporality of events could not be assessed as we employed a cross-sectional study design, that is, we did not have information on the previous conditions of the participants which means that it is possible that some of these conditions existed in the past, while others de facto occurred with COVID-19 crisis. The survey questionnaires were completed by those who felt interested and involved, i.e., a convenience sampling technique was used, this impairs the representativeness of the sample (in terms of sociodemographic variables) and the generalizability of our results. Also, the type of recruitment (including social media) as well as the online nature of the study, probably appealed more to people with an affinity with this kind of instrument. Besides, each questionnaire represented self-reported states; thus, over-reporting or under-reporting could be present. It is also important to note that international students were answering the survey questionnaire in a language that might not have been their mother language. Nevertheless, English fluency is a prerequisite to enroll in a study program at the University of Debrecen for international students. As the options for gender were only male/female in our survey questionnaire, we might have missed the views of students who do not identify themselves according to these gender categories. Also, no data on medical history/current medical status were collected. Lastly, we had to make minor changes to the used scales in the different languages for comparability.

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis has imposed a significant burden on the physical and psychological wellbeing of humans. Crises like the current pandemic can trigger unprecedented emotional and behavioral responses among individuals to adapt or cope with the situation. The elevated perceived stress levels during major life events can be further deepened by disengagement from home and by using inadequate coping strategies. By following and adhering to the international recommendations, adopting proper coping strategies, and equipping oneself with the required coping and stress management skills, the associated high levels of perceived stress and anxiety might be mitigated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compliance with institutional guidelines but they are available from the corresponding author (LRK) on a reasonable request.

Abbreviations

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Coronavirus Disease 2019

Perceived Stress Scale

Short Health Anxiety Inventory

Middle East Respiratory Syndrome

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome

Ways of Coping Questionnaire

World Health Organization

World Health Organization. Advice for the public on COVID-19. [Online]. 2020. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public . Accessed 9 Sep 2020.

National Center for Public Health. Opportunities to reduce contact numbers—Community events in relation to COVID-19 virus infection. [Online]. 2020. https://www.nnk.gov.hu/index.php/koronavirus-tajekoztato/549-opportunities-to-reduce-contact-numbers-community-events-in-relation-to-covid-19-virus-infection . Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

GardaWorld. Crisis24 News Alert. [Online]. 2020. https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts?search_api_fulltext=&na_countries%5B%5D=1431&field_news_alert_categories=All&field_news_alert_crit=All&items_per_page=20 . Accessed 20 Sep 2020.

Tanne JH, Hayasaki E, Zastrow M, Pulla P, Smith P, Rada AG. Covid-19: how doctors and healthcare systems are tackling coronavirus worldwide. Br Med J. 2020;368:m1090.

Article Google Scholar

Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, Khan M, Kerwan A, Al-Jabir A, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–6.

Rosenbaum L. Facing Covid-19 in Italy—ethics, logistics, and therapeutics on the epidemic’s front line. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1873–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2005492 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1729.

Akour A, Al-Tammemi AB, Barakat M, Kanj R, Fakhouri HN, Malkawi A, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and emergency distance teaching on the psychological status of university teachers: a cross-sectional study in Jordan. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:2391–9.

Al-Tammemi AB, Akour A, Alfalah L. Is it just about physical health? An online cross-sectional study exploring the psychological distress among university students in Jordan in the Midst of COVID-19 Pandemic. Front Psychol. 2020;11:562213.

Roddenberry A, Renk K. Locus of control and self-efficacy: potential mediators of stress, illness, and utilization of health services in college students. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2010;41:353–70.

Racic M, Todorovic R, Ivkovic N, Masic S, Joksimovic B, Kulic M. Self- perceived stress in relation to anxiety, depression and health-related quality of life among health professions students: a cross-sectional study from Bosnia and Herzegovina. Slov J Public Heal. 2017;56:251–9.

Görgen SM, Hiller W, Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cognitive coping, and emotion regulation: a latent variable approach. Int J Behav Med. 2014;21:364–74.

Abramowitz JS, Braddock A. Psychological treatment of health anxiety and hypochondriasis: a biopsychosocial approach. Boston: Hogrefe Publishing; 2008.

Google Scholar

Taylor S, Asmundson GJG. Treating health anxiety: a cognitive-behavioral approach. 1st ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2004.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,(DSM-5). 5th edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Wheaton MG, Abramowitz JS, Berman NC, Fabricant LE, Olatunji BO. Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cognit Ther Res. 2012;36:210–8.

Asmundson GJG, Taylor S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J Anxiety Disord. 2020;71:102211.

Taha SA, Matheson K, Anisman H. The 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic: the role of threat, coping, and media trust on vaccination intentions in Canada. J Health Commun. 2013;18:278–90.

Phua DH, Tang HK, Tham KY. Coping responses of emergency physicians and nurses to the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak. Acad Emerg. 2005;12:322–8.

Teasdale E, Yardley L, Schlotz W, Michie S. The importance of coping appraisal in behavioural responses to pandemic flu. Br J Health Psychol. 2012;17:44–59.

Sim K, Huak Chan Y, Chong PN, Chua HC, Wen SS. Psychosocial and coping responses within the community health care setting towards a national outbreak of an infectious disease. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:195–202.

Lazarus RS. Stress and emotion: a new synthesis. London: Free Association Books; 1999.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984.

Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Pers. 1987;1:141–69.

Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in hunan between January and March 2020 during the Outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei. China Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924171.

PubMed Google Scholar

Chua SE, Cheung V, Cheung C, McAlonan GM, Wong JWS, Cheung EPT, et al. Psychological effects of the SARS outbreak in Hong Kong on high-risk health care workers. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:391–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370404900609 .

Flesia L, Monaro M, Mazza C, Fietta V, Colicino E, Segatto B, et al. Predicting perceived stress related to the Covid-19 outbreak through stable psychological traits and machine learning models. J Clin Med. 2020;9:3350.

Khalid I, Khalid TJ, Qabajah MR, Barnard AG, Qushmaq IA. Healthcare workers emotions, perceived stressors and coping strategies during a MERS-CoV outbreak. Clin Med Res. 2016;14:7–14.

Gee S, Skovdal M. The role of risk perception in willingness to respond to the 2014–2016 West African Ebola outbreak: a qualitative study of international health care workers. Glob Heal Res Policy. 2017;2:21.

Gerhold L. COVID-19: Risk perception and Coping strategies. Results from a survey in Germany. PsyArXiv Prepr. 2020.

Auerbach RP, Alonso J, Axinn WG, Cuijpers P, Ebert DD, Green JG, et al. Mental disorders among college students in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol Med. 2016;46:2955–70.

Bíró É. Studies on the mental health of students in higher education. University of Debrecen; 2014. https://dea.lib.unideb.hu/dea/handle/2437/195979 . Accessed 15 Feb 2021.

The University of Debrecen. Facts and Figures. [Online]. 2020. https://www.edu.unideb.hu/page.php?id=28 . Accessed 25 Dec 2020.

Cohen S. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: The social psychology of health. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc; 1988. p. 31–67.

Strauder A, Thege BK. Az Észlelt Stressz Kérdőív (PSS) Magyar Verziójának Jellemzői. Mentálhigiéné És Pszichoszomatika. 2006;7:203–16.

Sørlie T, Sexton HC. The factor structure of “The Ways of Coping Questionnaire” and the process of coping in surgical patients. Pers Individ Dif. 2001;30:961–75.

Rózsa S, Purebl G, Susánszky É, Kő N, Szádóczky E, Réthelyi J, et al. Dimensions of coping: Hungarian adaptation of the Ways of Coping Questionnaire. Mentálhigiéné És Pszichoszomatika. 2008; 217–241.

Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick HMC. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843.

Alberts NM, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Jones SL, Sharpe D. The Short Health Anxiety Inventory: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord. 2013;27:68–78.

Köteles F, Simor P, Bárdos G. Validation and psychometric evaluation of the Hungarian version of the Short Health Anxiety Inventory (SHAI). Mentálhigiéné és Pszichoszomatika. 2011;12:191–213.

Artino AR. Regulation of Emotion. In: Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Boston, MA: Springer US; 2011. p. 1236–8.

Gross JJ. The emerging field of emotion regulation: an integrative review. Rev Gen Psychol. 1998;2:271–99.

Kaczkurkin AN, Foa EB. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anxiety disorders: an update on the empirical evidence. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17:337–46.

Jungmann SM, Witthöft M. Health anxiety, cyberchondria, and coping in the current COVID-19 pandemic: Which factors are related to coronavirus anxiety? J Anxiety Disord. 2020;73:102239.

Taha S, Matheson K, Cronin T, Anisman H. Intolerance of uncertainty, appraisals, coping, and anxiety: the case of the 2009 H1N1 pandemic. Br J Health Psychol. 2014;19:592–605.

Umucu E, Lee B. Examining the impact of COVID-19 on stress and coping strategies in individuals with disabilities and chronic conditions. Rehabil Psychol. 2020;65:193–8.

Main A, Zhou Q, Ma Y, Luecken LJ, Liu X. Relations of SARS-related stressors and coping to Chinese college students’ psychological adjustment during the 2003 Beijing SARS epidemic. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58:410–23.

Özdin S, Bayrak ÖŞ. Levels and predictors of anxiety, depression and health anxiety during COVID-19 pandemic in Turkish society: the importance of gender. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66:504–11.

Taylor S, Landry CA, Paluszek MM, Fergus TA, McKay D, Asmundson GJG. COVID stress syndrome: concept, structure, and correlates. Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:706–14.

Gamonal Limcaoco RS, Mateos EM, Fernández JM, Roncero C. Anxiety, worry and perceived stress in the world due to the COVID-19 pandemic, March 2020. Preliminary results. MedRxiv Prepr. 2020.

Abouammoh N, Irfan F, AlFaris E. Stress coping strategies among medical students and trainees in Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2020;20:124.

Gade S, Chari S, Gupta M. Perceived stress among medical students: to identify its sources and coping strategies. Arch Med Health Sci. 2014;2:80–6.

Leszko M, Iwański R, Jarzębińska A. The relationship between personality traits and coping styles among first-time and recurrent prisoners in Poland. Front Psychol. 2020;10:2969.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Mental Health and Coping During COVID-19 Pandemic. [Online]. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/managing-stress-anxiety.html . Accessed 9 Sep 2020.

Download references

Acknowledgments

We would like to provide our extreme thanks and appreciation to all students who participated in our study. ABA is currently supported by the Tempus Public Foundation’s scholarship at the University of Debrecen.

This research project did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Doctoral School of Health Sciences, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Szabolcs Garbóczy, Szilvia Harsányi, Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi & László Róbert Kolozsvári

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Szabolcs Garbóczy

Department of Personality and Clinical Psychology, Institute of Psychology, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Anita Szemán-Nagy

Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Mohamed S. Ahmad & Viktor Rekenyi

Department of Social and Work Psychology, Institute of Psychology, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Dorottya Ocsenás

Doctoral School of Human Sciences, University of Debrecen, Debrecen, Hungary

Department of Family and Occupational Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Debrecen, Móricz Zs. krt. 22, Debrecen, 4032, Hungary

Ala’a B. Al-Tammemi & László Róbert Kolozsvári

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors SG, ASN, MSA, SH, DO, VR, ABA, and LRK have worked on the study design, text writing, revising, and editing of the manuscript. DO, SG, and VR have done data management and extraction, data analysis. Drafting and interpretation of the manuscript were made in close collaboration by all authors SG, ASN, MSA, SH, DO, VR, ABA, and LRK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to László Róbert Kolozsvári .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical permission was obtained from the Hungarian Ethical Review Committee for Research in Psychology (Reference number: 2020-45). All methods were carried out following the institutional guidelines and conforming to the ethical standards of the declaration of Helsinki. All participants were informed about the study and written informed consent was obtained before completing the survey.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Garbóczy, S., Szemán-Nagy, A., Ahmad, M.S. et al. Health anxiety, perceived stress, and coping styles in the shadow of the COVID-19. BMC Psychol 9 , 53 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00560-3

Download citation

Received : 07 January 2021

Accepted : 26 March 2021

Published : 06 April 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00560-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Health anxiety

- Perceived stress

- Coping styles

- University students

BMC Psychology

ISSN: 2050-7283

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 27 November 2021

Psychological and biological resilience modulates the effects of stress on epigenetic aging

- Zachary M. Harvanek ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3702-1051 1 ,

- Nia Fogelman 2 ,

- Ke Xu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-6472-7052 1 , 3 &

- Rajita Sinha ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3012-4349 1 , 2 , 4 , 5

Translational Psychiatry volume 11 , Article number: 601 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

39 Citations

417 Altmetric

Metrics details

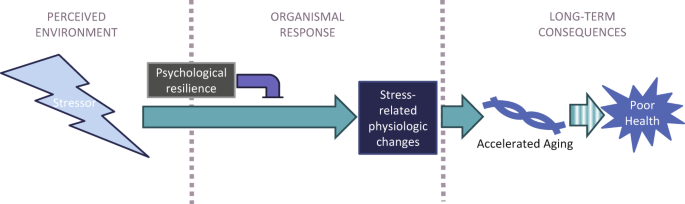

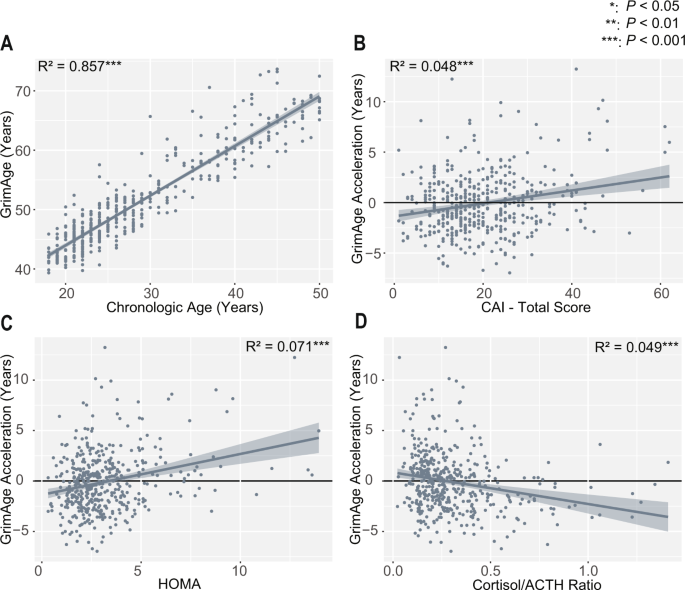

Our society is experiencing more stress than ever before, leading to both negative psychiatric and physical outcomes. Chronic stress is linked to negative long-term health consequences, raising the possibility that stress is related to accelerated aging. In this study, we examine whether resilience factors affect stress-associated biological age acceleration. Recently developed “epigenetic clocks” such as GrimAge have shown utility in predicting biological age and mortality. Here, we assessed the impact of cumulative stress, stress physiology, and resilience on accelerated aging in a community sample ( N = 444). Cumulative stress was associated with accelerated GrimAge ( P = 0.0388) and stress-related physiologic measures of adrenal sensitivity (Cortisol/ACTH ratio) and insulin resistance (HOMA). After controlling for demographic and behavioral factors, HOMA correlated with accelerated GrimAge ( P = 0.0186). Remarkably, psychological resilience factors of emotion regulation and self-control moderated these relationships. Emotion regulation moderated the association between stress and aging ( P = 8.82e−4) such that with worse emotion regulation, there was greater stress-related age acceleration, while stronger emotion regulation prevented any significant effect of stress on GrimAge. Self-control moderated the relationship between stress and insulin resistance ( P = 0.00732), with high self-control blunting this relationship. In the final model, in those with poor emotion regulation, cumulative stress continued to predict additional GrimAge Acceleration even while accounting for demographic, physiologic, and behavioral covariates. These results demonstrate that cumulative stress is associated with epigenetic aging in a healthy population, and these associations are modified by biobehavioral resilience factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Federico Cavanna, Stephanie Muller, … Enzo Tagliazucchi

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Joseph M. Rootman, Maggie Kiraga, … Zach Walsh

Overnight neuronal plasticity and adaptation to emotional distress

Yesenia Cabrera, Karin J. Koymans, … Rick Wassing

Introduction