- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write the Results/Findings Section in Research

What is the research paper Results section and what does it do?

The Results section of a scientific research paper represents the core findings of a study derived from the methods applied to gather and analyze information. It presents these findings in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation from the author, setting up the reader for later interpretation and evaluation in the Discussion section. A major purpose of the Results section is to break down the data into sentences that show its significance to the research question(s).

The Results section appears third in the section sequence in most scientific papers. It follows the presentation of the Methods and Materials and is presented before the Discussion section —although the Results and Discussion are presented together in many journals. This section answers the basic question “What did you find in your research?”

What is included in the Results section?

The Results section should include the findings of your study and ONLY the findings of your study. The findings include:

- Data presented in tables, charts, graphs, and other figures (may be placed into the text or on separate pages at the end of the manuscript)

- A contextual analysis of this data explaining its meaning in sentence form

- All data that corresponds to the central research question(s)

- All secondary findings (secondary outcomes, subgroup analyses, etc.)

If the scope of the study is broad, or if you studied a variety of variables, or if the methodology used yields a wide range of different results, the author should present only those results that are most relevant to the research question stated in the Introduction section .

As a general rule, any information that does not present the direct findings or outcome of the study should be left out of this section. Unless the journal requests that authors combine the Results and Discussion sections, explanations and interpretations should be omitted from the Results.

How are the results organized?

The best way to organize your Results section is “logically.” One logical and clear method of organizing research results is to provide them alongside the research questions—within each research question, present the type of data that addresses that research question.

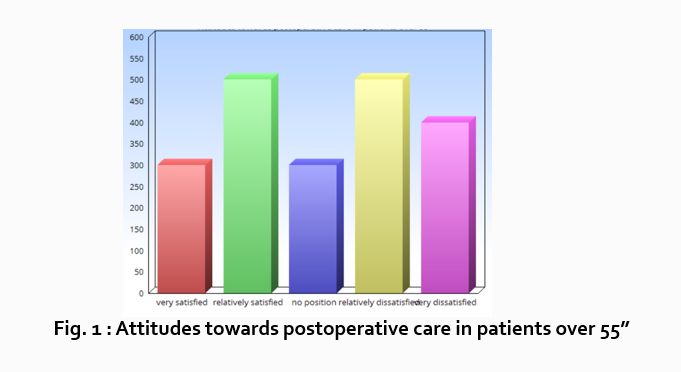

Let’s look at an example. Your research question is based on a survey among patients who were treated at a hospital and received postoperative care. Let’s say your first research question is:

“What do hospital patients over age 55 think about postoperative care?”

This can actually be represented as a heading within your Results section, though it might be presented as a statement rather than a question:

Attitudes towards postoperative care in patients over the age of 55

Now present the results that address this specific research question first. In this case, perhaps a table illustrating data from a survey. Likert items can be included in this example. Tables can also present standard deviations, probabilities, correlation matrices, etc.

Following this, present a content analysis, in words, of one end of the spectrum of the survey or data table. In our example case, start with the POSITIVE survey responses regarding postoperative care, using descriptive phrases. For example:

“Sixty-five percent of patients over 55 responded positively to the question “ Are you satisfied with your hospital’s postoperative care ?” (Fig. 2)

Include other results such as subcategory analyses. The amount of textual description used will depend on how much interpretation of tables and figures is necessary and how many examples the reader needs in order to understand the significance of your research findings.

Next, present a content analysis of another part of the spectrum of the same research question, perhaps the NEGATIVE or NEUTRAL responses to the survey. For instance:

“As Figure 1 shows, 15 out of 60 patients in Group A responded negatively to Question 2.”

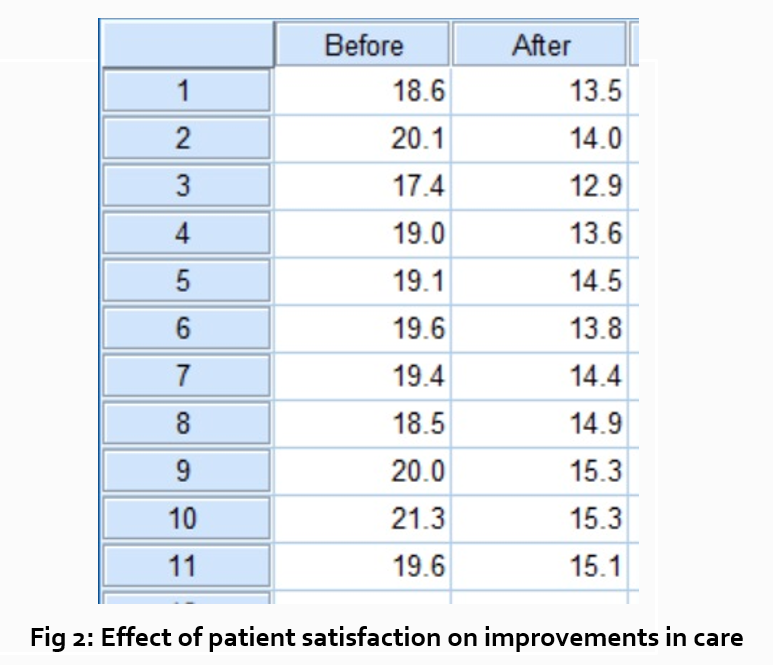

After you have assessed the data in one figure and explained it sufficiently, move on to your next research question. For example:

“How does patient satisfaction correspond to in-hospital improvements made to postoperative care?”

This kind of data may be presented through a figure or set of figures (for instance, a paired T-test table).

Explain the data you present, here in a table, with a concise content analysis:

“The p-value for the comparison between the before and after groups of patients was .03% (Fig. 2), indicating that the greater the dissatisfaction among patients, the more frequent the improvements that were made to postoperative care.”

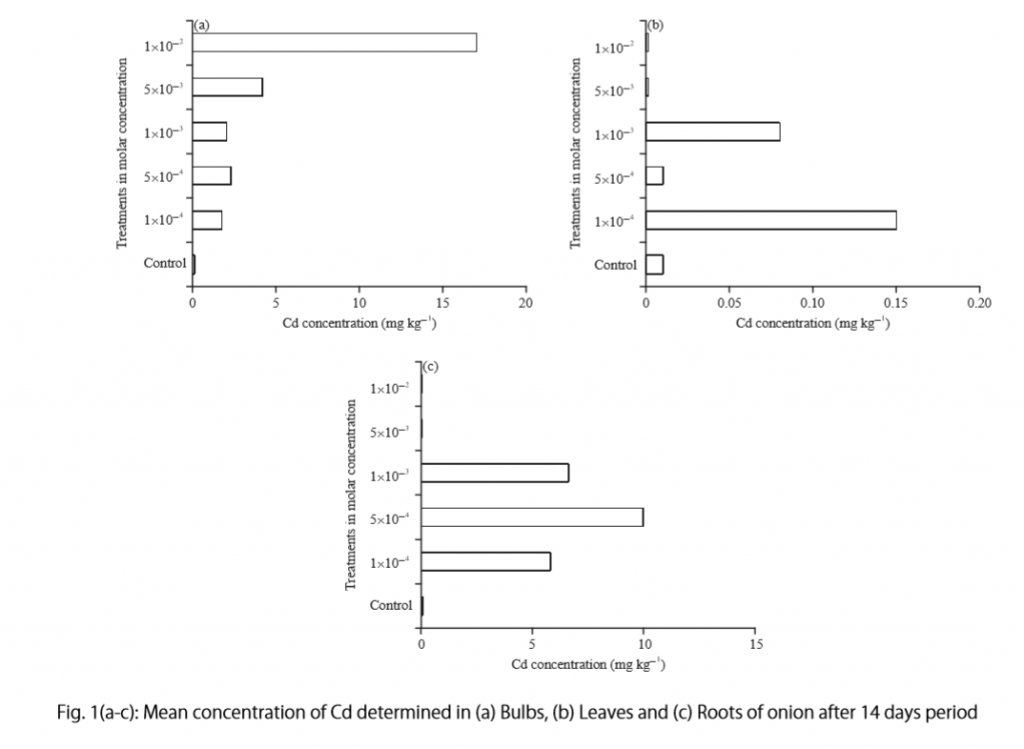

Let’s examine another example of a Results section from a study on plant tolerance to heavy metal stress . In the Introduction section, the aims of the study are presented as “determining the physiological and morphological responses of Allium cepa L. towards increased cadmium toxicity” and “evaluating its potential to accumulate the metal and its associated environmental consequences.” The Results section presents data showing how these aims are achieved in tables alongside a content analysis, beginning with an overview of the findings:

“Cadmium caused inhibition of root and leave elongation, with increasing effects at higher exposure doses (Fig. 1a-c).”

The figure containing this data is cited in parentheses. Note that this author has combined three graphs into one single figure. Separating the data into separate graphs focusing on specific aspects makes it easier for the reader to assess the findings, and consolidating this information into one figure saves space and makes it easy to locate the most relevant results.

Following this overall summary, the relevant data in the tables is broken down into greater detail in text form in the Results section.

- “Results on the bio-accumulation of cadmium were found to be the highest (17.5 mg kgG1) in the bulb, when the concentration of cadmium in the solution was 1×10G2 M and lowest (0.11 mg kgG1) in the leaves when the concentration was 1×10G3 M.”

Captioning and Referencing Tables and Figures

Tables and figures are central components of your Results section and you need to carefully think about the most effective way to use graphs and tables to present your findings . Therefore, it is crucial to know how to write strong figure captions and to refer to them within the text of the Results section.

The most important advice one can give here as well as throughout the paper is to check the requirements and standards of the journal to which you are submitting your work. Every journal has its own design and layout standards, which you can find in the author instructions on the target journal’s website. Perusing a journal’s published articles will also give you an idea of the proper number, size, and complexity of your figures.

Regardless of which format you use, the figures should be placed in the order they are referenced in the Results section and be as clear and easy to understand as possible. If there are multiple variables being considered (within one or more research questions), it can be a good idea to split these up into separate figures. Subsequently, these can be referenced and analyzed under separate headings and paragraphs in the text.

To create a caption, consider the research question being asked and change it into a phrase. For instance, if one question is “Which color did participants choose?”, the caption might be “Color choice by participant group.” Or in our last research paper example, where the question was “What is the concentration of cadmium in different parts of the onion after 14 days?” the caption reads:

“Fig. 1(a-c): Mean concentration of Cd determined in (a) bulbs, (b) leaves, and (c) roots of onions after a 14-day period.”

Steps for Composing the Results Section

Because each study is unique, there is no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to designing a strategy for structuring and writing the section of a research paper where findings are presented. The content and layout of this section will be determined by the specific area of research, the design of the study and its particular methodologies, and the guidelines of the target journal and its editors. However, the following steps can be used to compose the results of most scientific research studies and are essential for researchers who are new to preparing a manuscript for publication or who need a reminder of how to construct the Results section.

Step 1 : Consult the guidelines or instructions that the target journal or publisher provides authors and read research papers it has published, especially those with similar topics, methods, or results to your study.

- The guidelines will generally outline specific requirements for the results or findings section, and the published articles will provide sound examples of successful approaches.

- Note length limitations on restrictions on content. For instance, while many journals require the Results and Discussion sections to be separate, others do not—qualitative research papers often include results and interpretations in the same section (“Results and Discussion”).

- Reading the aims and scope in the journal’s “ guide for authors ” section and understanding the interests of its readers will be invaluable in preparing to write the Results section.

Step 2 : Consider your research results in relation to the journal’s requirements and catalogue your results.

- Focus on experimental results and other findings that are especially relevant to your research questions and objectives and include them even if they are unexpected or do not support your ideas and hypotheses.

- Catalogue your findings—use subheadings to streamline and clarify your report. This will help you avoid excessive and peripheral details as you write and also help your reader understand and remember your findings. Create appendices that might interest specialists but prove too long or distracting for other readers.

- Decide how you will structure of your results. You might match the order of the research questions and hypotheses to your results, or you could arrange them according to the order presented in the Methods section. A chronological order or even a hierarchy of importance or meaningful grouping of main themes or categories might prove effective. Consider your audience, evidence, and most importantly, the objectives of your research when choosing a structure for presenting your findings.

Step 3 : Design figures and tables to present and illustrate your data.

- Tables and figures should be numbered according to the order in which they are mentioned in the main text of the paper.

- Information in figures should be relatively self-explanatory (with the aid of captions), and their design should include all definitions and other information necessary for readers to understand the findings without reading all of the text.

- Use tables and figures as a focal point to tell a clear and informative story about your research and avoid repeating information. But remember that while figures clarify and enhance the text, they cannot replace it.

Step 4 : Draft your Results section using the findings and figures you have organized.

- The goal is to communicate this complex information as clearly and precisely as possible; precise and compact phrases and sentences are most effective.

- In the opening paragraph of this section, restate your research questions or aims to focus the reader’s attention to what the results are trying to show. It is also a good idea to summarize key findings at the end of this section to create a logical transition to the interpretation and discussion that follows.

- Try to write in the past tense and the active voice to relay the findings since the research has already been done and the agent is usually clear. This will ensure that your explanations are also clear and logical.

- Make sure that any specialized terminology or abbreviation you have used here has been defined and clarified in the Introduction section .

Step 5 : Review your draft; edit and revise until it reports results exactly as you would like to have them reported to your readers.

- Double-check the accuracy and consistency of all the data, as well as all of the visual elements included.

- Read your draft aloud to catch language errors (grammar, spelling, and mechanics), awkward phrases, and missing transitions.

- Ensure that your results are presented in the best order to focus on objectives and prepare readers for interpretations, valuations, and recommendations in the Discussion section . Look back over the paper’s Introduction and background while anticipating the Discussion and Conclusion sections to ensure that the presentation of your results is consistent and effective.

- Consider seeking additional guidance on your paper. Find additional readers to look over your Results section and see if it can be improved in any way. Peers, professors, or qualified experts can provide valuable insights.

One excellent option is to use a professional English proofreading and editing service such as Wordvice, including our paper editing service . With hundreds of qualified editors from dozens of scientific fields, Wordvice has helped thousands of authors revise their manuscripts and get accepted into their target journals. Read more about the proofreading and editing process before proceeding with getting academic editing services and manuscript editing services for your manuscript.

As the representation of your study’s data output, the Results section presents the core information in your research paper. By writing with clarity and conciseness and by highlighting and explaining the crucial findings of their study, authors increase the impact and effectiveness of their research manuscripts.

For more articles and videos on writing your research manuscript, visit Wordvice’s Resources page.

Wordvice Resources

- How to Write a Research Paper Introduction

- Which Verb Tenses to Use in a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Title

- Useful Phrases for Academic Writing

- Common Transition Terms in Academic Papers

- Active and Passive Voice in Research Papers

- 100+ Verbs That Will Make Your Research Writing Amazing

- Tips for Paraphrasing in Research Papers

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The results section is where you report the findings of your study based upon the methodology [or methodologies] you applied to gather information. The results section should state the findings of the research arranged in a logical sequence without bias or interpretation. A section describing results should be particularly detailed if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Findings can only confirm or reject the hypothesis underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise. Use non-textual elements appropriately, such as figures and tables, to present findings more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish information that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other content that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data that has not been summarized should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good strategy is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper that follows].

Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Brett, Paul. "A Genre Analysis of the Results Section of Sociology Articles." English for Specific Speakers 13 (1994): 47-59; Go to English for Specific Purposes on ScienceDirect;Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit; "Reporting Findings." In Making Sense of Social Research Malcolm Williams, editor. (London;: SAGE Publications, 2003) pp. 188-207.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Organization and Approach

For most research papers in the social and behavioral sciences, there are two possible ways of organizing the results . Both approaches are appropriate in how you report your findings, but use only one approach.

- Present a synopsis of the results followed by an explanation of key findings . This approach can be used to highlight important findings. For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is appropriate to highlight this finding in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening belongs in the discussion section of your paper.

- Present a result and then explain it, before presenting the next result then explaining it, and so on, then end with an overall synopsis . This is the preferred approach if you have multiple results of equal significance. It is more common in longer papers because it helps the reader to better understand each finding. In this model, it is helpful to provide a brief conclusion that ties each of the findings together and provides a narrative bridge to the discussion section of the your paper.

NOTE : Just as the literature review should be arranged under conceptual categories rather than systematically describing each source, you should also organize your findings under key themes related to addressing the research problem. This can be done under either format noted above [i.e., a thorough explanation of the key results or a sequential, thematic description and explanation of each finding].

II. Content

In general, the content of your results section should include the following:

- Introductory context for understanding the results by restating the research problem underpinning your study . This is useful in re-orientating the reader's focus back to the research problem after having read a review of the literature and your explanation of the methods used for gathering and analyzing information.

- Inclusion of non-textual elements, such as, figures, charts, photos, maps, tables, etc. to further illustrate key findings, if appropriate . Rather than relying entirely on descriptive text, consider how your findings can be presented visually. This is a helpful way of condensing a lot of data into one place that can then be referred to in the text. Consider referring to appendices if there is a lot of non-textual elements.

- A systematic description of your results, highlighting for the reader observations that are most relevant to the topic under investigation . Not all results that emerge from the methodology used to gather information may be related to answering the " So What? " question. Do not confuse observations with interpretations; observations in this context refers to highlighting important findings you discovered through a process of reviewing prior literature and gathering data.

- The page length of your results section is guided by the amount and types of data to be reported . However, focus on findings that are important and related to addressing the research problem. It is not uncommon to have unanticipated results that are not relevant to answering the research question. This is not to say that you don't acknowledge tangential findings and, in fact, can be referred to as areas for further research in the conclusion of your paper. However, spending time in the results section describing tangential findings clutters your overall results section and distracts the reader.

- A short paragraph that concludes the results section by synthesizing the key findings of the study . Highlight the most important findings you want readers to remember as they transition into the discussion section. This is particularly important if, for example, there are many results to report, the findings are complicated or unanticipated, or they are impactful or actionable in some way [i.e., able to be pursued in a feasible way applied to practice].

NOTE: Always use the past tense when referring to your study's findings. Reference to findings should always be described as having already happened because the method used to gather the information has been completed.

III. Problems to Avoid

When writing the results section, avoid doing the following :

- Discussing or interpreting your results . Save this for the discussion section of your paper, although where appropriate, you should compare or contrast specific results to those found in other studies [e.g., "Similar to the work of Smith [1990], one of the findings of this study is the strong correlation between motivation and academic achievement...."].

- Reporting background information or attempting to explain your findings. This should have been done in your introduction section, but don't panic! Often the results of a study point to the need for additional background information or to explain the topic further, so don't think you did something wrong. Writing up research is rarely a linear process. Always revise your introduction as needed.

- Ignoring negative results . A negative result generally refers to a finding that does not support the underlying assumptions of your study. Do not ignore them. Document these findings and then state in your discussion section why you believe a negative result emerged from your study. Note that negative results, and how you handle them, can give you an opportunity to write a more engaging discussion section, therefore, don't be hesitant to highlight them.

- Including raw data or intermediate calculations . Ask your professor if you need to include any raw data generated by your study, such as transcripts from interviews or data files. If raw data is to be included, place it in an appendix or set of appendices that are referred to in the text.

- Be as factual and concise as possible in reporting your findings . Do not use phrases that are vague or non-specific, such as, "appeared to be greater than other variables..." or "demonstrates promising trends that...." Subjective modifiers should be explained in the discussion section of the paper [i.e., why did one variable appear greater? Or, how does the finding demonstrate a promising trend?].

- Presenting the same data or repeating the same information more than once . If you want to highlight a particular finding, it is appropriate to do so in the results section. However, you should emphasize its significance in relation to addressing the research problem in the discussion section. Do not repeat it in your results section because you can do that in the conclusion of your paper.

- Confusing figures with tables . Be sure to properly label any non-textual elements in your paper. Don't call a chart an illustration or a figure a table. If you are not sure, go here .

Annesley, Thomas M. "Show Your Cards: The Results Section and the Poker Game." Clinical Chemistry 56 (July 2010): 1066-1070; Bavdekar, Sandeep B. and Sneha Chandak. "Results: Unraveling the Findings." Journal of the Association of Physicians of India 63 (September 2015): 44-46; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Caprette, David R. Writing Research Papers. Experimental Biosciences Resources. Rice University; Hancock, Dawson R. and Bob Algozzine. Doing Case Study Research: A Practical Guide for Beginning Researchers . 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press, 2011; Introduction to Nursing Research: Reporting Research Findings. Nursing Research: Open Access Nursing Research and Review Articles. (January 4, 2012); Kretchmer, Paul. Twelve Steps to Writing an Effective Results Section. San Francisco Edit ; Ng, K. H. and W. C. Peh. "Writing the Results." Singapore Medical Journal 49 (2008): 967-968; Reporting Research Findings. Wilder Research, in partnership with the Minnesota Department of Human Services. (February 2009); Results. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Schafer, Mickey S. Writing the Results. Thesis Writing in the Sciences. Course Syllabus. University of Florida.

Writing Tip

Why Don't I Just Combine the Results Section with the Discussion Section?

It's not unusual to find articles in scholarly social science journals where the author(s) have combined a description of the findings with a discussion about their significance and implications. You could do this. However, if you are inexperienced writing research papers, consider creating two distinct sections for each section in your paper as a way to better organize your thoughts and, by extension, your paper. Think of the results section as the place where you report what your study found; think of the discussion section as the place where you interpret the information and answer the "So What?" question. As you become more skilled writing research papers, you can consider melding the results of your study with a discussion of its implications.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn and Aleksandra Kasztalska. Writing the Experimental Report: Methods, Results, and Discussion. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University.

- << Previous: Insiderness

- Next: Using Non-Textual Elements >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 1:02 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

- How to Write Discussions and Conclusions

The discussion section contains the results and outcomes of a study. An effective discussion informs readers what can be learned from your experiment and provides context for the results.

What makes an effective discussion?

When you’re ready to write your discussion, you’ve already introduced the purpose of your study and provided an in-depth description of the methodology. The discussion informs readers about the larger implications of your study based on the results. Highlighting these implications while not overstating the findings can be challenging, especially when you’re submitting to a journal that selects articles based on novelty or potential impact. Regardless of what journal you are submitting to, the discussion section always serves the same purpose: concluding what your study results actually mean.

A successful discussion section puts your findings in context. It should include:

- the results of your research,

- a discussion of related research, and

- a comparison between your results and initial hypothesis.

Tip: Not all journals share the same naming conventions.

You can apply the advice in this article to the conclusion, results or discussion sections of your manuscript.

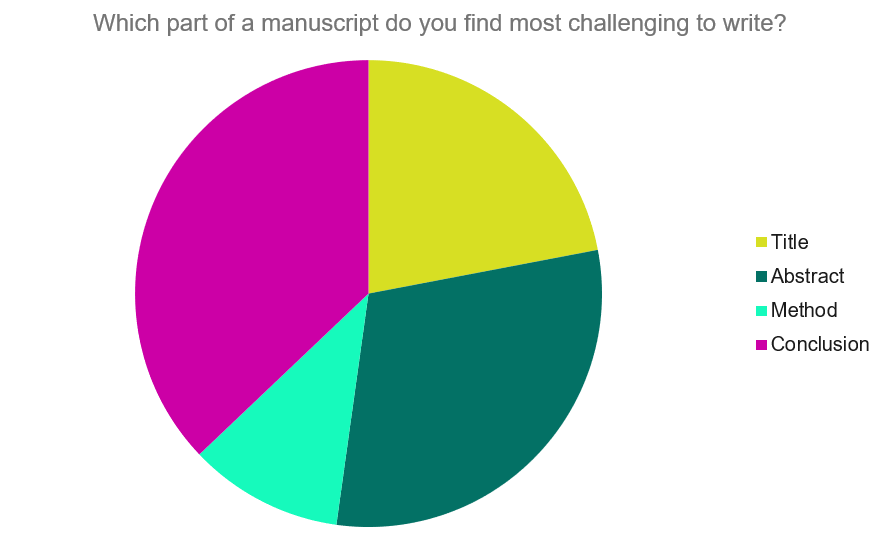

Our Early Career Researcher community tells us that the conclusion is often considered the most difficult aspect of a manuscript to write. To help, this guide provides questions to ask yourself, a basic structure to model your discussion off of and examples from published manuscripts.

Questions to ask yourself:

- Was my hypothesis correct?

- If my hypothesis is partially correct or entirely different, what can be learned from the results?

- How do the conclusions reshape or add onto the existing knowledge in the field? What does previous research say about the topic?

- Why are the results important or relevant to your audience? Do they add further evidence to a scientific consensus or disprove prior studies?

- How can future research build on these observations? What are the key experiments that must be done?

- What is the “take-home” message you want your reader to leave with?

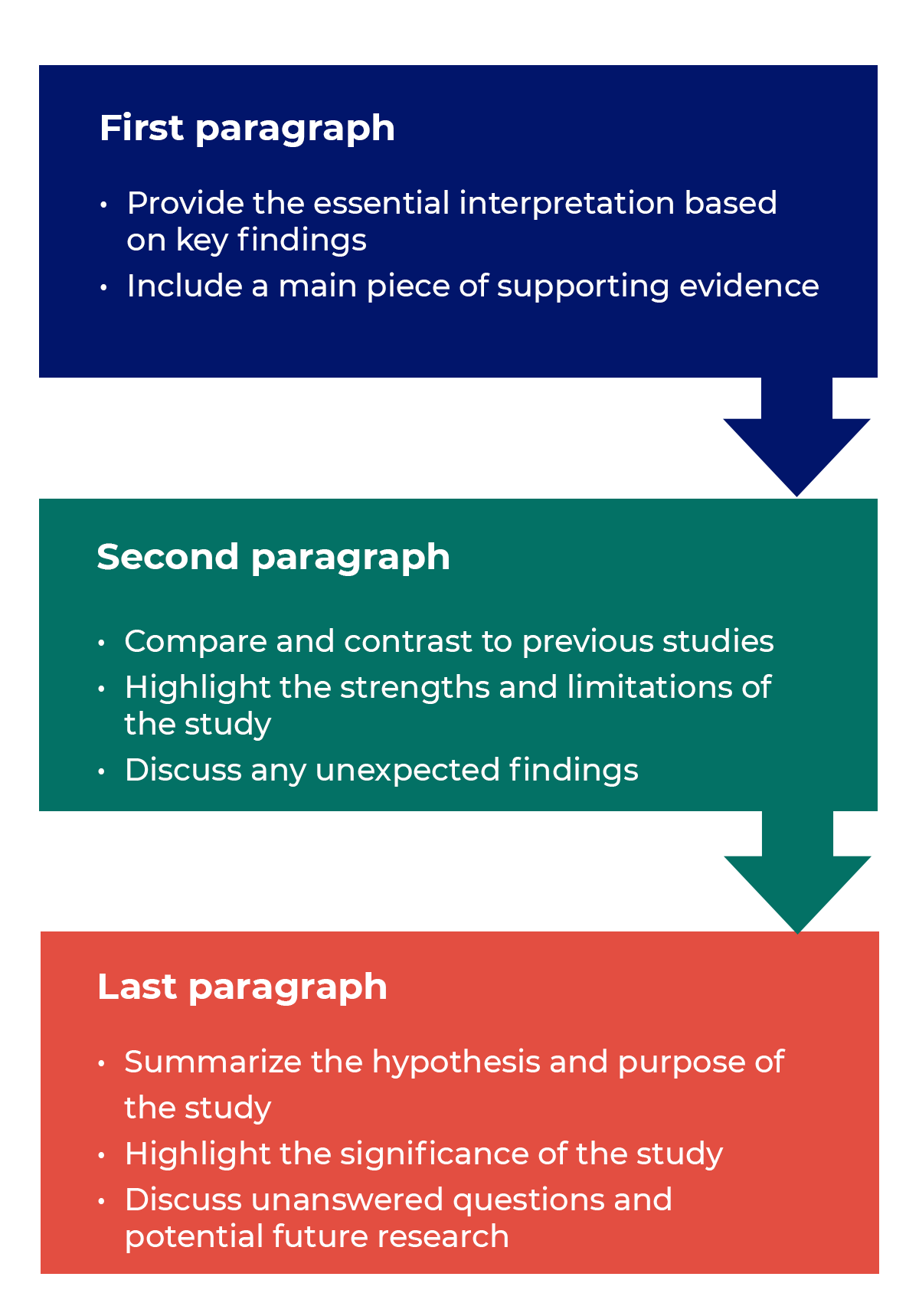

How to structure a discussion

Trying to fit a complete discussion into a single paragraph can add unnecessary stress to the writing process. If possible, you’ll want to give yourself two or three paragraphs to give the reader a comprehensive understanding of your study as a whole. Here’s one way to structure an effective discussion:

Writing Tips

While the above sections can help you brainstorm and structure your discussion, there are many common mistakes that writers revert to when having difficulties with their paper. Writing a discussion can be a delicate balance between summarizing your results, providing proper context for your research and avoiding introducing new information. Remember that your paper should be both confident and honest about the results!

- Read the journal’s guidelines on the discussion and conclusion sections. If possible, learn about the guidelines before writing the discussion to ensure you’re writing to meet their expectations.

- Begin with a clear statement of the principal findings. This will reinforce the main take-away for the reader and set up the rest of the discussion.

- Explain why the outcomes of your study are important to the reader. Discuss the implications of your findings realistically based on previous literature, highlighting both the strengths and limitations of the research.

- State whether the results prove or disprove your hypothesis. If your hypothesis was disproved, what might be the reasons?

- Introduce new or expanded ways to think about the research question. Indicate what next steps can be taken to further pursue any unresolved questions.

- If dealing with a contemporary or ongoing problem, such as climate change, discuss possible consequences if the problem is avoided.

- Be concise. Adding unnecessary detail can distract from the main findings.

Don’t

- Rewrite your abstract. Statements with “we investigated” or “we studied” generally do not belong in the discussion.

- Include new arguments or evidence not previously discussed. Necessary information and evidence should be introduced in the main body of the paper.

- Apologize. Even if your research contains significant limitations, don’t undermine your authority by including statements that doubt your methodology or execution.

- Shy away from speaking on limitations or negative results. Including limitations and negative results will give readers a complete understanding of the presented research. Potential limitations include sources of potential bias, threats to internal or external validity, barriers to implementing an intervention and other issues inherent to the study design.

- Overstate the importance of your findings. Making grand statements about how a study will fully resolve large questions can lead readers to doubt the success of the research.

Snippets of Effective Discussions:

Consumer-based actions to reduce plastic pollution in rivers: A multi-criteria decision analysis approach

Identifying reliable indicators of fitness in polar bears

- How to Write a Great Title

- How to Write an Abstract

- How to Write Your Methods

- How to Report Statistics

- How to Edit Your Work

The contents of the Peer Review Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

The contents of the Writing Center are also available as a live, interactive training session, complete with slides, talking points, and activities. …

There’s a lot to consider when deciding where to submit your work. Learn how to choose a journal that will help your study reach its audience, while reflecting your values as a researcher…

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Writing a scientific paper.

- Writing a lab report

- INTRODUCTION

Writing a "good" results section

Figures and Captions in Lab Reports

"Results Checklist" from: How to Write a Good Scientific Paper. Chris A. Mack. SPIE. 2018.

Additional tips for results sections.

- LITERATURE CITED

- Bibliography of guides to scientific writing and presenting

- Peer Review

- Presentations

- Lab Report Writing Guides on the Web

This is the core of the paper. Don't start the results sections with methods you left out of the Materials and Methods section. You need to give an overall description of the experiments and present the data you found.

- Factual statements supported by evidence. Short and sweet without excess words

- Present representative data rather than endlessly repetitive data

- Discuss variables only if they had an effect (positive or negative)

- Use meaningful statistics

- Avoid redundancy. If it is in the tables or captions you may not need to repeat it

A short article by Dr. Brett Couch and Dr. Deena Wassenberg, Biology Program, University of Minnesota

- Present the results of the paper, in logical order, using tables and graphs as necessary.

- Explain the results and show how they help to answer the research questions posed in the Introduction. Evidence does not explain itself; the results must be presented and then explained.

- Avoid: presenting results that are never discussed; presenting results in chronological order rather than logical order; ignoring results that do not support the conclusions;

- Number tables and figures separately beginning with 1 (i.e. Table 1, Table 2, Figure 1, etc.).

- Do not attempt to evaluate the results in this section. Report only what you found; hold all discussion of the significance of the results for the Discussion section.

- It is not necessary to describe every step of your statistical analyses. Scientists understand all about null hypotheses, rejection rules, and so forth and do not need to be reminded of them. Just say something like, "Honeybees did not use the flowers in proportion to their availability (X2 = 7.9, p<0.05, d.f.= 4, chi-square test)." Likewise, cite tables and figures without describing in detail how the data were manipulated. Explanations of this sort should appear in a legend or caption written on the same page as the figure or table.

- You must refer in the text to each figure or table you include in your paper.

- Tables generally should report summary-level data, such as means ± standard deviations, rather than all your raw data. A long list of all your individual observations will mean much less than a few concise, easy-to-read tables or figures that bring out the main findings of your study.

- Only use a figure (graph) when the data lend themselves to a good visual representation. Avoid using figures that show too many variables or trends at once, because they can be hard to understand.

From: https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/guides/imrad-results-discussion

- << Previous: METHODS

- Next: DISCUSSION >>

- Last Updated: Aug 4, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/scientificwriting

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing pp 717–731 Cite as

How to Present Results in a Research Paper

- Aparna Mukherjee 4 ,

- Gunjan Kumar 4 &

- Rakesh Lodha 5

- First Online: 01 October 2023

558 Accesses

The results section is the core of a research manuscript where the study data and analyses are presented in an organized, uncluttered manner such that the reader can easily understand and interpret the findings. This section is completely factual; there is no place for opinions or explanations from the authors. The results should correspond to the objectives of the study in an orderly manner. Self-explanatory tables and figures add value to this section and make data presentation more convenient and appealing. The results presented in this section should have a link with both the preceding methods section and the following discussion section. A well-written, articulate results section lends clarity and credibility to the research paper and the study as a whole. This chapter provides an overview and important pointers to effective drafting of the results section in a research manuscript and also in theses.

- Statistical analyses

- Qualitative study

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Kallestinova ED (2011) How to write your first research paper. Yale J Biol Med 84(3):181–190

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

STROBE. STROBE. [cited 2022 Nov 10]. https://www.strobe-statement.org/

Consort—Welcome to the CONSORT Website. http://www.consort-statement.org/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Korevaar DA, Cohen JF, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP et al (2016) Updating standards for reporting diagnostic accuracy: the development of STARD 2015. Res Integr Peer Rev 1(1):7

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n71

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD et al (2021) PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 372:n160

Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups | EQUATOR Network. https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/coreq/ . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Aggarwal R, Sahni P (2015) The results section. In: Aggarwal R, Sahni P (eds) Reporting and publishing research in the biomedical sciences, 1st edn. National Medical Journal of India, Delhi, pp 24–44

Google Scholar

Mukherjee A, Lodha R (2016) Writing the results. Indian Pediatr 53(5):409–415

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Lodha R, Randev S, Kabra SK (2016) Oral antibiotics for community acquired pneumonia with chest indrawing in children aged below five years: a systematic review. Indian Pediatr 53(6):489–495

Anderson C (2010) Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ 74(8):141

Roberts C, Kumar K, Finn G (2020) Navigating the qualitative manuscript writing process: some tips for authors and reviewers. BMC Med Educ 20:439

Bigby C (2015) Preparing manuscripts that report qualitative research: avoiding common pitfalls and illegitimate questions. Aust Soc Work 68(3):384–391

Article Google Scholar

Vincent BP, Kumar G, Parameswaran S, Kar SS (2019) Barriers and suggestions towards deceased organ donation in a government tertiary care teaching hospital: qualitative study using socio-ecological model framework. Indian J Transplant 13(3):194

McCormick JB, Hopkins MA (2021) Exploring public concerns for sharing and governance of personal health information: a focus group study. JAMIA Open 4(4):ooab098

Groenland -emeritus professor E. Employing the matrix method as a tool for the analysis of qualitative research data in the business domain. Rochester, NY; 2014. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2495330 . Accessed 10 Nov 2022

Download references

Acknowledgments

The book chapter is derived in part from our article “Mukherjee A, Lodha R. Writing the Results. Indian Pediatr. 2016 May 8;53(5):409-15.” We thank the Editor-in-Chief of the journal “Indian Pediatrics” for the permission for the same.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Clinical Studies, Trials and Projection Unit, Indian Council of Medical Research, New Delhi, India

Aparna Mukherjee & Gunjan Kumar

Department of Pediatrics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Rakesh Lodha

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rakesh Lodha .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Retired Senior Expert Pharmacologist at the Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology, and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Gowraganahalli Jagadeesh

Professor & Director, Research Training and Publications, The Office of Research and Development, Periyar Maniammai Institute of Science & Technology (Deemed to be University), Vallam, Tamil Nadu, India

Pitchai Balakumar

Division Cardiology & Nephrology, Office of Cardiology, Hematology, Endocrinology and Nephrology, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, US Food and Drug Administration, Silver Spring, MD, USA

Fortunato Senatore

Ethics declarations

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Mukherjee, A., Kumar, G., Lodha, R. (2023). How to Present Results in a Research Paper. In: Jagadeesh, G., Balakumar, P., Senatore, F. (eds) The Quintessence of Basic and Clinical Research and Scientific Publishing. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_44

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-99-1284-1_44

Published : 01 October 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-99-1283-4

Online ISBN : 978-981-99-1284-1

eBook Packages : Biomedical and Life Sciences Biomedical and Life Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Manuscript Preparation

How to write the results section of a research paper

- 3 minute read

- 51.5K views

Table of Contents

At its core, a research paper aims to fill a gap in the research on a given topic. As a result, the results section of the paper, which describes the key findings of the study, is often considered the core of the paper. This is the section that gets the most attention from reviewers, peers, students, and any news organization reporting on your findings. Writing a clear, concise, and logical results section is, therefore, one of the most important parts of preparing your manuscript.

Difference between results and discussion

Before delving into how to write the results section, it is important to first understand the difference between the results and discussion sections. The results section needs to detail the findings of the study. The aim of this section is not to draw connections between the different findings or to compare it to previous findings in literature—that is the purview of the discussion section. Unlike the discussion section, which can touch upon the hypothetical, the results section needs to focus on the purely factual. In some cases, it may even be preferable to club these two sections together into a single section. For example, while writing a review article, it can be worthwhile to club these two sections together, as the main results in this case are the conclusions that can be drawn from the literature.

Structure of the results section

Although the main purpose of the results section in a research paper is to report the findings, it is necessary to present an introduction and repeat the research question. This establishes a connection to the previous section of the paper and creates a smooth flow of information.

Next, the results section needs to communicate the findings of your research in a systematic manner. The section needs to be organized such that the primary research question is addressed first, then the secondary research questions. If the research addresses multiple questions, the results section must individually connect with each of the questions. This ensures clarity and minimizes confusion while reading.

Consider representing your results visually. For example, graphs, tables, and other figures can help illustrate the findings of your paper, especially if there is a large amount of data in the results.

Remember, an appealing results section can help peer reviewers better understand the merits of your research, thereby increasing your chances of publication.

Practical guidance for writing an effective results section for a research paper

- Always use simple and clear language. Avoid the use of uncertain or out-of-focus expressions.

- The findings of the study must be expressed in an objective and unbiased manner. While it is acceptable to correlate certain findings in the discussion section, it is best to avoid overinterpreting the results.

- If the research addresses more than one hypothesis, use sub-sections to describe the results. This prevents confusion and promotes understanding.

- Ensure that negative results are included in this section, even if they do not support the research hypothesis.

- Wherever possible, use illustrations like tables, figures, charts, or other visual representations to showcase the results of your research paper. Mention these illustrations in the text, but do not repeat the information that they convey.

- For statistical data, it is adequate to highlight the tests and explain their results. The initial or raw data should not be mentioned in the results section of a research paper.

The results section of a research paper is usually the most impactful section because it draws the greatest attention. Regardless of the subject of your research paper, a well-written results section is capable of generating interest in your research.

For detailed information and assistance on writing the results of a research paper, refer to Elsevier Author Services.

- Research Process

Writing a good review article

Why is data validation important in research?

You may also like.

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Path to An Impactful Paper: Common Manuscript Writing Patterns and Structure

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

How to Write an Effective Results Section

Affiliation.

- 1 Rothman Orthopaedics Institute, Philadelphia, PA.

- PMID: 31145152

- DOI: 10.1097/BSD.0000000000000845

Developing a well-written research paper is an important step in completing a scientific study. This paper is where the principle investigator and co-authors report the purpose, methods, findings, and conclusions of the study. A key element of writing a research paper is to clearly and objectively report the study's findings in the Results section. The Results section is where the authors inform the readers about the findings from the statistical analysis of the data collected to operationalize the study hypothesis, optimally adding novel information to the collective knowledge on the subject matter. By utilizing clear, concise, and well-organized writing techniques and visual aids in the reporting of the data, the author is able to construct a case for the research question at hand even without interpreting the data.

- Data Analysis

- Peer Review, Research*

- Publishing*

- Sample Size

- Privacy Policy

Buy Me a Coffee

Home » Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Research Findings – Types Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Findings

Definition:

Research findings refer to the results obtained from a study or investigation conducted through a systematic and scientific approach. These findings are the outcomes of the data analysis, interpretation, and evaluation carried out during the research process.

Types of Research Findings

There are two main types of research findings:

Qualitative Findings

Qualitative research is an exploratory research method used to understand the complexities of human behavior and experiences. Qualitative findings are non-numerical and descriptive data that describe the meaning and interpretation of the data collected. Examples of qualitative findings include quotes from participants, themes that emerge from the data, and descriptions of experiences and phenomena.

Quantitative Findings

Quantitative research is a research method that uses numerical data and statistical analysis to measure and quantify a phenomenon or behavior. Quantitative findings include numerical data such as mean, median, and mode, as well as statistical analyses such as t-tests, ANOVA, and regression analysis. These findings are often presented in tables, graphs, or charts.

Both qualitative and quantitative findings are important in research and can provide different insights into a research question or problem. Combining both types of findings can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon and improve the validity and reliability of research results.

Parts of Research Findings

Research findings typically consist of several parts, including:

- Introduction: This section provides an overview of the research topic and the purpose of the study.

- Literature Review: This section summarizes previous research studies and findings that are relevant to the current study.

- Methodology : This section describes the research design, methods, and procedures used in the study, including details on the sample, data collection, and data analysis.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including statistical analyses and data visualizations.

- Discussion : This section interprets the results and explains what they mean in relation to the research question(s) and hypotheses. It may also compare and contrast the current findings with previous research studies and explore any implications or limitations of the study.

- Conclusion : This section provides a summary of the key findings and the main conclusions of the study.

- Recommendations: This section suggests areas for further research and potential applications or implications of the study’s findings.

How to Write Research Findings

Writing research findings requires careful planning and attention to detail. Here are some general steps to follow when writing research findings:

- Organize your findings: Before you begin writing, it’s essential to organize your findings logically. Consider creating an outline or a flowchart that outlines the main points you want to make and how they relate to one another.

- Use clear and concise language : When presenting your findings, be sure to use clear and concise language that is easy to understand. Avoid using jargon or technical terms unless they are necessary to convey your meaning.

- Use visual aids : Visual aids such as tables, charts, and graphs can be helpful in presenting your findings. Be sure to label and title your visual aids clearly, and make sure they are easy to read.

- Use headings and subheadings: Using headings and subheadings can help organize your findings and make them easier to read. Make sure your headings and subheadings are clear and descriptive.

- Interpret your findings : When presenting your findings, it’s important to provide some interpretation of what the results mean. This can include discussing how your findings relate to the existing literature, identifying any limitations of your study, and suggesting areas for future research.

- Be precise and accurate : When presenting your findings, be sure to use precise and accurate language. Avoid making generalizations or overstatements and be careful not to misrepresent your data.

- Edit and revise: Once you have written your research findings, be sure to edit and revise them carefully. Check for grammar and spelling errors, make sure your formatting is consistent, and ensure that your writing is clear and concise.

Research Findings Example

Following is a Research Findings Example sample for students:

Title: The Effects of Exercise on Mental Health

Sample : 500 participants, both men and women, between the ages of 18-45.

Methodology : Participants were divided into two groups. The first group engaged in 30 minutes of moderate intensity exercise five times a week for eight weeks. The second group did not exercise during the study period. Participants in both groups completed a questionnaire that assessed their mental health before and after the study period.

Findings : The group that engaged in regular exercise reported a significant improvement in mental health compared to the control group. Specifically, they reported lower levels of anxiety and depression, improved mood, and increased self-esteem.

Conclusion : Regular exercise can have a positive impact on mental health and may be an effective intervention for individuals experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Applications of Research Findings

Research findings can be applied in various fields to improve processes, products, services, and outcomes. Here are some examples:

- Healthcare : Research findings in medicine and healthcare can be applied to improve patient outcomes, reduce morbidity and mortality rates, and develop new treatments for various diseases.

- Education : Research findings in education can be used to develop effective teaching methods, improve learning outcomes, and design new educational programs.

- Technology : Research findings in technology can be applied to develop new products, improve existing products, and enhance user experiences.

- Business : Research findings in business can be applied to develop new strategies, improve operations, and increase profitability.

- Public Policy: Research findings can be used to inform public policy decisions on issues such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development.

- Social Sciences: Research findings in social sciences can be used to improve understanding of human behavior and social phenomena, inform public policy decisions, and develop interventions to address social issues.

- Agriculture: Research findings in agriculture can be applied to improve crop yields, develop new farming techniques, and enhance food security.

- Sports : Research findings in sports can be applied to improve athlete performance, reduce injuries, and develop new training programs.

When to use Research Findings

Research findings can be used in a variety of situations, depending on the context and the purpose. Here are some examples of when research findings may be useful:

- Decision-making : Research findings can be used to inform decisions in various fields, such as business, education, healthcare, and public policy. For example, a business may use market research findings to make decisions about new product development or marketing strategies.

- Problem-solving : Research findings can be used to solve problems or challenges in various fields, such as healthcare, engineering, and social sciences. For example, medical researchers may use findings from clinical trials to develop new treatments for diseases.

- Policy development : Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. For example, policymakers may use research findings to develop policies aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

- Program evaluation: Research findings can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions in various fields, such as education, healthcare, and social services. For example, educational researchers may use findings from evaluations of educational programs to improve teaching and learning outcomes.

- Innovation: Research findings can be used to inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. For example, engineers may use research findings on materials science to develop new and innovative products.

Purpose of Research Findings

The purpose of research findings is to contribute to the knowledge and understanding of a particular topic or issue. Research findings are the result of a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques.

The main purposes of research findings are:

- To generate new knowledge : Research findings contribute to the body of knowledge on a particular topic, by adding new information, insights, and understanding to the existing knowledge base.

- To test hypotheses or theories : Research findings can be used to test hypotheses or theories that have been proposed in a particular field or discipline. This helps to determine the validity and reliability of the hypotheses or theories, and to refine or develop new ones.

- To inform practice: Research findings can be used to inform practice in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- To identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research.

- To contribute to policy development: Research findings can be used to inform policy development in various fields, such as environmental protection, social welfare, and economic development. By providing evidence-based recommendations, research findings can help policymakers to develop effective policies that address societal challenges.

Characteristics of Research Findings

Research findings have several key characteristics that distinguish them from other types of information or knowledge. Here are some of the main characteristics of research findings:

- Objective : Research findings are based on a systematic and rigorous investigation of a research question or hypothesis, using appropriate research methods and techniques. As such, they are generally considered to be more objective and reliable than other types of information.

- Empirical : Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are derived from observations or measurements of the real world. This gives them a high degree of credibility and validity.

- Generalizable : Research findings are often intended to be generalizable to a larger population or context beyond the specific study. This means that the findings can be applied to other situations or populations with similar characteristics.

- Transparent : Research findings are typically reported in a transparent manner, with a clear description of the research methods and data analysis techniques used. This allows others to assess the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Peer-reviewed: Research findings are often subject to a rigorous peer-review process, in which experts in the field review the research methods, data analysis, and conclusions of the study. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Reproducible : Research findings are often designed to be reproducible, meaning that other researchers can replicate the study using the same methods and obtain similar results. This helps to ensure the validity and reliability of the findings.

Advantages of Research Findings

Research findings have many advantages, which make them valuable sources of knowledge and information. Here are some of the main advantages of research findings:

- Evidence-based: Research findings are based on empirical evidence, which means that they are grounded in data and observations from the real world. This makes them a reliable and credible source of information.

- Inform decision-making: Research findings can be used to inform decision-making in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and business. By identifying best practices and evidence-based interventions, research findings can help practitioners and policymakers to make informed decisions and improve outcomes.

- Identify gaps in knowledge: Research findings can help to identify gaps in knowledge and understanding of a particular topic, which can then be addressed by further research. This contributes to the ongoing development of knowledge in various fields.

- Improve outcomes : Research findings can be used to develop and implement evidence-based practices and interventions, which have been shown to improve outcomes in various fields, such as healthcare, education, and social services.

- Foster innovation: Research findings can inspire or guide innovation in various fields, such as technology and engineering. By providing new information and understanding of a particular topic, research findings can stimulate new ideas and approaches to problem-solving.

- Enhance credibility: Research findings are generally considered to be more credible and reliable than other types of information, as they are based on rigorous research methods and are subject to peer-review processes.

Limitations of Research Findings

While research findings have many advantages, they also have some limitations. Here are some of the main limitations of research findings:

- Limited scope: Research findings are typically based on a particular study or set of studies, which may have a limited scope or focus. This means that they may not be applicable to other contexts or populations.

- Potential for bias : Research findings can be influenced by various sources of bias, such as researcher bias, selection bias, or measurement bias. This can affect the validity and reliability of the findings.

- Ethical considerations: Research findings can raise ethical considerations, particularly in studies involving human subjects. Researchers must ensure that their studies are conducted in an ethical and responsible manner, with appropriate measures to protect the welfare and privacy of participants.

- Time and resource constraints : Research studies can be time-consuming and require significant resources, which can limit the number and scope of studies that are conducted. This can lead to gaps in knowledge or a lack of research on certain topics.

- Complexity: Some research findings can be complex and difficult to interpret, particularly in fields such as science or medicine. This can make it challenging for practitioners and policymakers to apply the findings to their work.

- Lack of generalizability : While research findings are intended to be generalizable to larger populations or contexts, there may be factors that limit their generalizability. For example, cultural or environmental factors may influence how a particular intervention or treatment works in different populations or contexts.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Appendices – Writing Guide, Types and Examples

Research Report – Example, Writing Guide and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Scope of the Research – Writing Guide and...

Research Contribution – Thesis Guide

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Drawing Conclusions and Reporting the Results

Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton

Learning Objectives

- Identify the conclusions researchers can make based on the outcome of their studies.

- Describe why scientists avoid the term “scientific proof.”

- Explain the different ways that scientists share their findings.

Drawing Conclusions

Since statistics are probabilistic in nature and findings can reflect type I or type II errors, we cannot use the results of a single study to conclude with certainty that a theory is true. Rather theories are supported, refuted, or modified based on the results of research.

If the results are statistically significant and consistent with the hypothesis and the theory that was used to generate the hypothesis, then researchers can conclude that the theory is supported. Not only did the theory make an accurate prediction, but there is now a new phenomenon that the theory accounts for. If a hypothesis is disconfirmed in a systematic empirical study, then the theory has been weakened. It made an inaccurate prediction, and there is now a new phenomenon that it does not account for.

Although this seems straightforward, there are some complications. First, confirming a hypothesis can strengthen a theory but it can never prove a theory. In fact, scientists tend to avoid the word “prove” when talking and writing about theories. One reason for this avoidance is that the result may reflect a type I error. Another reason for this avoidance is that there may be other plausible theories that imply the same hypothesis, which means that confirming the hypothesis strengthens all those theories equally. A third reason is that it is always possible that another test of the hypothesis or a test of a new hypothesis derived from the theory will be disconfirmed. This difficulty is a version of the famous philosophical “problem of induction.” One cannot definitively prove a general principle (e.g., “All swans are white.”) just by observing confirming cases (e.g., white swans)—no matter how many. It is always possible that a disconfirming case (e.g., a black swan) will eventually come along. For these reasons, scientists tend to think of theories—even highly successful ones—as subject to revision based on new and unexpected observations.

A second complication has to do with what it means when a hypothesis is disconfirmed. According to the strictest version of the hypothetico-deductive method, disconfirming a hypothesis disproves the theory it was derived from. In formal logic, the premises “if A then B ” and “not B ” necessarily lead to the conclusion “not A .” If A is the theory and B is the hypothesis (“if A then B ”), then disconfirming the hypothesis (“not B ”) must mean that the theory is incorrect (“not A ”). In practice, however, scientists do not give up on their theories so easily. One reason is that one disconfirmed hypothesis could be a missed opportunity (the result of a type II error) or it could be the result of a faulty research design. Perhaps the researcher did not successfully manipulate the independent variable or measure the dependent variable.

A disconfirmed hypothesis could also mean that some unstated but relatively minor assumption of the theory was not met. For example, if Zajonc had failed to find social facilitation in cockroaches, he could have concluded that drive theory is still correct but it applies only to animals with sufficiently complex nervous systems. That is, the evidence from a study can be used to modify a theory. This practice does not mean that researchers are free to ignore disconfirmations of their theories. If they cannot improve their research designs or modify their theories to account for repeated disconfirmations, then they eventually must abandon their theories and replace them with ones that are more successful.

The bottom line here is that because statistics are probabilistic in nature and because all research studies have flaws there is no such thing as scientific proof, there is only scientific evidence.

Reporting the Results

The final step in the research process involves reporting the results. As described in the section on Reviewing the Research Literature in this chapter, results are typically reported in peer-reviewed journal articles and at conferences.

The most prestigious way to report one’s findings is by writing a manuscript and having it published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal. Manuscripts published in psychology journals typically must adhere to the writing style of the American Psychological Association (APA style). You will likely be learning the major elements of this writing style in this course.

Another way to report findings is by writing a book chapter that is published in an edited book. Preferably the editor of the book puts the chapter through peer review but this is not always the case and some scientists are invited by editors to write book chapters.

A fun way to disseminate findings is to give a presentation at a conference. This can either be done as an oral presentation or a poster presentation. Oral presentations involve getting up in front of an audience of fellow scientists and giving a talk that might last anywhere from 10 minutes to 1 hour (depending on the conference) and then fielding questions from the audience. Alternatively, poster presentations involve summarizing the study on a large poster that provides a brief overview of the purpose, methods, results, and discussion. The presenter stands by their poster for an hour or two and discusses it with people who pass by. Presenting one’s work at a conference is a great way to get feedback from one’s peers before attempting to undergo the more rigorous peer-review process involved in publishing a journal article.

Drawing Conclusions and Reporting the Results Copyright © 2022 by Rajiv S. Jhangiani; I-Chant A. Chiang; Carrie Cuttler; and Dana C. Leighton is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Organizing Academic Research Papers: 7. The Results

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Executive Summary

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tertiary Sources

- What Is Scholarly vs. Popular?

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Annotated Bibliography

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- How to Manage Group Projects

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Essays

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Acknowledgements

The results section of the research paper is where you report the findings of your study based upon the information gathered as a result of the methodology [or methodologies] you applied. The results section should simply state the findings, without bias or interpretation, and arranged in a logical sequence. The results section should always be written in the past tense. A section describing results [a.k.a., "findings"] is particularly necessary if your paper includes data generated from your own research.

Importance of a Good Results Section

When formulating the results section, it's important to remember that the results of a study do not prove anything . Research results can only confirm or reject the research problem underpinning your study. However, the act of articulating the results helps you to understand the problem from within, to break it into pieces, and to view the research problem from various perspectives.

The page length of this section is set by the amount and types of data to be reported . Be concise, using non-textual elements, such as figures and tables, if appropriate, to present results more effectively. In deciding what data to describe in your results section, you must clearly distinguish material that would normally be included in a research paper from any raw data or other material that could be included as an appendix. In general, raw data should not be included in the main text of your paper unless requested to do so by your professor.

Avoid providing data that is not critical to answering the research question . The background information you described in the introduction section should provide the reader with any additional context or explanation needed to understand the results. A good rule is to always re-read the background section of your paper after you have written up your results to ensure that the reader has enough context to understand the results [and, later, how you interpreted the results in the discussion section of your paper].

Bates College; Burton, Neil et al. Doing Your Education Research Project . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2008; Results . The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

For most research paper formats, there are two ways of presenting and organizing the results .

- Present the results followed by a short explanation of the findings . For example, you may have noticed an unusual correlation between two variables during the analysis of your findings. It is correct to point this out in the results section. However, speculating as to why this correlation exists, and offering a hypothesis about what may be happening, belongs in the discussion section of your paper.