- Internet ›

Cyber Crime & Security

Cybersecurity and cybercrime in the Philippines - statistics & facts

Heightened cyber incidents triggered by the pandemic, can cyber-attacks be prevented, key insights.

Detailed statistics

Online data breach density APAC 2021-2022, by country

National cyber security index ranking APAC 2023, by country

Revenue of the cybersecurity industry in the Philippines 2019-2028

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Current statistics on this topic.

Cyber Security

Number of data breaches Philippines 2020-2022

Income & Expenditure

Most frequent consumer fraud schemes Philippines Q4 2023

Related topics

Recommended.

- Crime in the Philippines

- Internet usage in the Philippines

- E-commerce in the Philippines

- Banking in the Philippines

- Digital payments in the Philippines

Recommended statistics

- Premium Statistic Share of cyberattacks in worldwide regions 2022, by category

- Basic Statistic Number of breached accounts APAC 2021-2022, by country

- Basic Statistic Online data breach density APAC 2021-2022, by country

- Premium Statistic National cyber security index ranking APAC 2023, by country

- Premium Statistic Largest cybersecurity markets APAC 2022, by revenue

Share of cyberattacks in worldwide regions 2022, by category

Distribution of cyberattacks in selected global regions in 2022, by category

Number of breached accounts APAC 2021-2022, by country

Number of accounts exposed in online data breaches in the Asia-Pacific region in 2021 and 2022, by country or territory

Online account breach density in the Asia-Pacific region in 2021 and 2022, by country or territory (per 1,000 population)

National cyber security index ranking in the Asia-Pacific region as of July 2023

Largest cybersecurity markets APAC 2022, by revenue

Largest cybersecurity markets in the Asia-Pacific region in 2022, by revenue (in million U.S. dollars)

Cybersecurity market

- Premium Statistic Revenue of the cybersecurity industry in the Philippines 2019-2028

- Premium Statistic Cybersecurity market revenue in the Philippines 2022, by segment

- Premium Statistic Cyber solutions market revenue Philippines 2016-2028

- Premium Statistic Cyber solutions market revenue Philippines 2022, by segment

- Premium Statistic Digital security services market revenue Philippines 2016-2028

- Premium Statistic Online security services market revenue Philippines 2022, by segment

Revenue of the cybersecurity market in the Philippines from 2019 to 2028 (in million U.S. dollars)

Cybersecurity market revenue in the Philippines 2022, by segment

Revenue of the cybersecurity market in the Philippines from 2022, by segment (in million U.S. dollars)

Cyber solutions market revenue Philippines 2016-2028

Revenue of the cyber solutions market in the Philippines from 2016 to 2028 (in million U.S. dollars)

Cyber solutions market revenue Philippines 2022, by segment

Revenue of the cyber solutions market in the Philippines in 2022, by segment (in million U.S. dollars)

Digital security services market revenue Philippines 2016-2028

Revenue of the online security services market in the Philippines from 2016 to 2028 (in million U.S. dollars)

Online security services market revenue Philippines 2022, by segment

Revenue of the digital security services market in the Philippines in 2022, by segment (in million U.S. dollars)

Cyberthreats

- Basic Statistic Number of data breaches Philippines 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of phishing attacks Philippines 2021-H1 2022

- Basic Statistic Number of crypto phishing attacks Philippines 2021-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of detected mobile malware attacks Philippines 2019-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of web threats via browsers detected and blocked Philippines 2017-2022

- Basic Statistic Most frequent consumer fraud schemes Philippines Q4 2023

Number of incidents of data breaches in the Philippines from 2020 to 2022 (in millions)

Number of phishing attacks Philippines 2021-H1 2022

Number of phishing attacks in the Philippines in 2021 to 1st half of 2022 (in millions)

Number of crypto phishing attacks Philippines 2021-2022

Number of crypto phishing attacks in the Philippines in 2021 and 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of detected mobile malware attacks Philippines 2019-2022

Number of mobile malware attacks detected in the Philippines from 2019 to 2022 (in 1,000s)

Number of web threats via browsers detected and blocked Philippines 2017-2022

Number of web threats via browsers detected and foiled in the Philippines from 2017 to 2022 (in millions)

Most frequent fraud schemes targeting consumers in the Philippines as of 4th quarter 2023

Cyber incidents at companies

- Premium Statistic Number of web threats against businesses Philippines 2020-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of remote desktop protocol (RDP) attacks Philippines 2021-2022

- Premium Statistic Average ransom paid by companies hit by ransomware Philippines 2020-2021

- Premium Statistic Main cyber security concerns among surveyed companies Philippines 2022

- Premium Statistic Top impacts of cyber incidents at companies Philippines 2022

Number of web threats against businesses Philippines 2020-2022

Number of online attacks targeting businesses in the Philippines from 2020 to 2022 (in millions)

Number of remote desktop protocol (RDP) attacks Philippines 2021-2022

Number of bruteforce attacks against remote desktop protocol (RDP) users in the Philippines in 2021 and 2022 (in millions)

Average ransom paid by companies hit by ransomware Philippines 2020-2021

Average cost to organizations hit with ransomware in the Philippines in 2020 and 2021 (in million U.S. dollars)

Main cyber security concerns among surveyed companies Philippines 2022

Leading concerns on cyber security among surveyed companies in the Philippines in 2022

Top impacts of cyber incidents at companies Philippines 2022

Leading impacts of cyber incidents reported at companies in the Philippines in 2022

Cyber security preparedness of companies

- Premium Statistic Cybersecurity readiness of surveyed companies Philippines 2022, by stage

- Premium Statistic Readiness to protect devices among surveyed companies Philippines 2022, by stage

- Premium Statistic Readiness to protect application workloads among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

- Premium Statistic Readiness to protect networks among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

- Premium Statistic Readiness to protect data among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Cybersecurity readiness of surveyed companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Overall cybersecurity readiness of surveyed companies in the Philippines as of September 2022, by stage

Readiness to protect devices among surveyed companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Readiness of surveyed companies to protect devices in the Philippines as of September 2022, by stage

Readiness to protect application workloads among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Readiness of surveyed companies to protect application workloads in the Philippines as of September 2022, by stage

Readiness to protect networks among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Readiness of surveyed companies to protect networks in the Philippines as of September 2022, by stage

Readiness to protect data among companies Philippines 2022, by stage

Readiness of surveyed companies to protect data in the Philippines as of September 2022, by stage

User behavior on internet security

- Premium Statistic Opinion on sharing personal information Philippines Q4 2022

- Premium Statistic Factors against sharing personal information in the Philippines Q4 2023

- Premium Statistic Installed smartphone apps in the Philippines 2021

- Premium Statistic Attitudes on data privacy Philippines 2021

Opinion on sharing personal information Philippines Q4 2022

Share of individuals concerned about sharing personal information in the Philippines as of 4th quarter 2022

Factors against sharing personal information in the Philippines Q4 2023

Main reasons for not sharing personal information in the Philippines as of 4th quarter 2023

Installed smartphone apps in the Philippines 2021

Types of applications installed on smartphones in the Philippines in 2021

Attitudes on data privacy Philippines 2021

Attitudes on data privacy among adults in the Philippines in 2021

Further reports Get the best reports to understand your industry

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

- The e-commerce aftermath: increased cyber threats on online shoppers in the Philippines

- Cyber security in South Korea

- Cybersecurity and cybercrime in the Asia-Pacific region

- Cybersecurity and cybercrime in Singapore

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

The trans-national cybercrime court: towards a new harmonisation of cyber law regime in ASEAN

Der transnationale Gerichtshof für Cyberkriminalität – auf dem Weg zu einer neuen Harmonisierung des Cyberrechts im Verband Südostasiatischer Nationen (ASEAN)

- Published: 06 December 2023

- Volume 5 , pages 121–141, ( 2024 )

Cite this article

- Kwan Yuen Iu 1 &

- Vanessa Man-Yi Wong ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-4409-3216 2

176 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Legal harmonisation of cyber laws in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) is necessary to combat the transnational nature of cybercrimes. However, this is a difficult task in ASEAN as it requires all ASEAN member states to agree on a uniform cybercrime regulatory framework. The rapid evolution of cybercrime also undermines the strength of a static convention. This leads to the following question: How can a harmonized regulatory framework that would efficiently tackle the rapid evolution of cybercrime be designed? Regrettably, the Budapest Convention failed to facilitate the legal harmonisation in ASEAN with its inability to reach universal consensus. This paper argues that a regional cybercrime court, namely the ASEAN Cybercrime Court, can be an alternative approach to achieving legal harmonisation with the prevalence of cybercrimes. The theoretical framework of this paper is based on the concept of international common law articulated by Andrew Guzman and Timothy Meyer, in which certain members unable to agree on a broad agreement can instead agree to shallow rules to create an institution with authority to promulgate rules. In effect, it reduces the transaction costs for reaching a consensus. This paper also analyses the feasibility and merit of the creation of the ASEAN Cybercrime Court from three aspects: the jurisdiction, the existence of an independent prosecutorʼs office and the legal interpretation. Although the solution is not a perfect answer to legal harmonisation, it serves as a starting point on a path to progress ultimately leading to the conclusion of a binding multilateral treaty.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

An overview of cybercrime law in South Africa

Sizwe Snail ka Mtuze & Melody Musoni

Cybercrime in Australia

The Rule of Law as a Well-Established and Well-Defined Principle of EU Law

Laurent Pech

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), ‘Darknet Cybercrime Threats to Southeast Asia 2020’ (2021) < https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/darknet/index.html > accessed 1 October 2022, 5.

Interpol, ‘ASEAN Cyberthreat Assessment 2021’ (22 January 2021) < https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2021/INTERPOL-report-charts-top-cyberthreats-in-Southeast-Asia > accessed 18 September 2022 (hereinafter “Interpol’s Report”) 13.

Simon Kemp, ‘Digital 2020: Global Digital Overview’ ( DataReportal , 30 January 2020) < https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview > accessed 27 September 2022; Interpol’s Report (n 4) 8.

Enno Hinz, ‘Cambodia: Human trafficking crisis driven by cyberscams’ ( Deutsche Welle , 12 September 2022) < https://www.dw.com/en/cambodia-human-trafficking-crisis-driven-by-cyberscams/a-63092938 > accessed 29 September 2022.

The Associated Press, ‘24 more Malaysians rescued from Cambodia human traffickers’ ( ABC News , 9 September 2022) < https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/24-malaysians-rescued-cambodia-human-traffickers-89589335 > accessed 29 September 2022.

ASEAN, ‘ASEAN Protocol on Enhanced Dispute Settlement Mechanism’ (2012) < https://asean.org/asean-protocol-on-enhanced-dispute-settlement-mechanism/ > accessed 30 September 2022.

Nicohlas W. Cade, ‘An Adaptive Approach for an Evolving Crime: The Case for an International Cyber Court and Penal Code’ (2012) 37(3) Brooklyn J Int’l L 1139, 1147-1148.

Filippo Spiezia, ‘International cooperation and protection of victims in cyberspace: welcoming Protocol II to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime’ (2022) 23(1) ERA Forum 101, 102.

Alexandra Perloff-Giles, ‘Transnational Cyber Offenses: Overcoming Jurisdictional Challenges’ (2018) 43 Yale J Int’l L 191, 204.

Spiezia (n 16) 103.

Jonathan Clough, ‘A World of Difference: The Budapest Convention on Cybercrime and the Challenges of Harmonisation’ (2nd International Serious and Organised Crime Conference, Brisbane, July 2013) 698, 701.

ASEAN, ASEAN Documents Series on Transnational Crime: Terrorism and Violent Extremism; Drugs; Cybercrime; and Trafficking in Persons (Jakarta: ASEAN Secretariat 2017).

Hitoshi Nasu and others, The Legal Authority of ASEAN as a Security Institution (CUP 2019) 143.

Iqbal Ramadhan, ‘ASEAN Consensus and Forming Cybersecurity Regulation in Southeast Asia’ (the 1st International Conference on Contemporary Risk Studies, Jakarta, March-April 2022) 2.

ASEAN Declaration to Prevent and Combat Cybercrime (adopted 13 November 2017).

ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Person, Especially Women and Children (adopted 23 November 2015).

Andrew T. Guzman, ‘Against Consent’ (2012) 52 Virginal J Int’l L 747, 764.

Cade (n 15) 1139.

Europol and Eurojust Public Information, ‘Common challenges in combating cybercrime’ (2019) < https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/common_challenges_in_combating_cybercrime_2018.pdf > accessed 10 September 2022, 12.

ASEAN-Australia Counter Trafficking, ‘The use and abuse of technology in human trafficking in Southeast Asia’ (30 July 2022) < https://www.aseanact.org/story/use-and-abuse-of-technology-in-human-trafficking-southeast-asia/ > accessed 1 October 2022.

Ralf Emmers, ‘ASEAN minus X: Should This Formula Be Extended?’ (2017) RSIS Commentary Nanyang Technology University < https://hdl.handle.net/10356/86219 > accessed 10 October 2022.

Clough (n 20) 700.

The Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (signed 23 November 2001) TIAS 131, ETS 185.

ibid Preamble.

Council of Europe Cybercrime Division DGI, ‘Joining the Convention on Cybercrime: Benefits’ (16 June 2022) < https://rm.coe.int/cyber-buda-benefits-june2022-en-final/1680a6f93b > accessed 9 September 2022.

Eugenio Benincasa, ‘The role of regional organizations in building cyber resilience: ASEAN and the EU’ Pacific Forum Issues & Insights Vol. 20, WP 3 6/2020, 1 < https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/issuesinsights_Vol20WP3-1.pdf > accessed 9 September 2022.

Hanan Mohamed Ali, ‘“Norm Subsidiarity” or “Norm Diffusion”? A Cross-Regional Examination of Norms in ASEAN-GCC Cybersecurity Governance’ (2021) 4(1) The Journal of Intelligence, Conflict, and Warfare 123, 127.

Gabey Goh, ‘Cybercrime: Malaysia not lagging but needs to level up’ ( Digital News Asia , 24 September 2014) < https://www.digitalnewsasia.com/security/cybercrime-malaysia-not-lagging-but-needs-to-level-up > accessed 11 September 2022.

Guzman (n 26) 756–757.

Russia & FSU, ‘Russia prepares new UN anti-cybercrime convention-report’ ( RT , 14 April 2017) < https://www.rt.com/russia/384728-russia-has-prepared-new-international/ > accessed 5 October 2022.

UNGA ‘Letter dated 11 October 2017 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General’ (16 October 2017) UN Doc (A/C.3/72/12).

Guzman (n 26) 759.

Benincasa (n 36) 1.

Goh (n 38).

Marco Gercke, ‘10 years Convention on Cybercrime: Achievements and Failures of the Council of Europe’s Instrument in the Fight against Internet-related Crimes’ (2011) 12(5) Computer Law Review International 142; Stein Schjolberg, ‘The History of Cybercrime’ (2020) 13 Schriftenreihe des Cybercrime Research Institute 96.

Cade (n 15) 1155.

Andrew T. Guzman & Timothy L. Meyer, ‘International Soft Law’ (2010) 2(1) Journal of Legal Analysis 171, 182.

Andrew T. Guzman & Timothy L. Meyer, ‘Explaining Soft Law’ (Latin American and Caribbean Law and Economics Association (ALACDE) Annual Papers, UC Berkeley, 2010).

Judge Stein Schjolberg, ‘Peace and Justice in Cyberspace: Potential new global legal mechanisms against global cyberattacks and other global cybercrimes’ (EWI Worldwide Cybersecurity Summit Special Interest Seminar, New Delhi, October 2012) 6.

Guzman & Meyer (n 51) 171.

The ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) (signed 8 August 1967).

Guzman (n 26) 761–762.

Guzman & Meyer (n 51) 202.

Alan Boyle, ‘Soft Law in International Law-Making’ in Malcolm D. Evans (ed) International Law (OUP 2018) 119.

Nicaragua v United States of America (Merits) ICJ Rep 1986.

Guzman & Meyer (n 51) 202–203.

Nasu (n 22) 151.

Clough (n 20) 701.

Visoot Tuvayanond, ‘The Role of the Rule of Law, the Legal Approximation and the National Judiciary in ASEAN Integration’ (2001) 6(1) Thammasat Review 74, 82.

Boyle (n 63) 123.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted on 10 December 1948).

Guzman (n 26) 781.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, ‘Overview of Capacity Building Activities’ < https://www.icty.org/en/outreach/capacity-building/overview-activities > accessed 26 September 2022.

Judge Stein Schjolberg, ‘Recommendations for potential new global legal mechanisms against global cyberattacks and other global cybercrimes’ EWI Cybercrime Legal Working Group 3/2012, 17.

Benincasa (n 36) 2.

ASEAN Declaration to Prevent and Combat Cybercrime (n 22).

Usanee Aimsiranun, ‘Comparative Study on the Legal Framework on General Differentiated Integration Mechanisms in the European Union, APEC, and ASEAN’ (2020) ADBI Working Paper 1107 (Tokyo: Asian Development Bank Institute) 5.

Ramadhan (n 23).

Nasu (n 22) 158.

Robert Cryer and others, An Introduction to International Criminal Law and Procedure (4th edn, CUP 2019) 57.

Kuala Lumpur Declaration Combating Transitional Crime, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (signed on 30 September 2015).

Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Cooperation in the Field of Non-Traditional Security Issues, Manila, Philippines (signed on 21 September 2017).

Joint Statement of the Fourth ASEAN Plus China Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime Consultation (30 September 2015).

Cade (n 15) 20.

Daniel, T. Ntanda Nsereko, ‘The International Criminal Court: Jurisdictional and Related Issues’ (1999) 10 Criminal Law Forum 87, 120.

A. Hays Butler, ‘The Doctrine of Universal Jurisdiction: A Review of the Literature’ (2000) 11(3) Criminal Law Forum 353, 354.

Geneva Convention I (12 August 1949) art 49.

George Fletcher, ‘Against Universal Jurisdiction’ (2003) 1 JICJ 580.

Perloff-Giles (n 17) 224.

Benincasa (n 36) 9.

Schjolberg (n 55) 20.

International Criminal Court, ‘Office of the Prosecutor’ < https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp > accessed 1 October 2022.

Guzman & Meyer (n 51) 204.

Cade (n 15) 1170.

Cryer (n 87) 483.

International Criminal Court, ‘Asia-Pacific States | International Criminal Court’ < https://asp.icc-cpi.int/states-parties/asian-states > accessed 24 October 2023.

Boyle (n 63) 118.

Guzman & Meyer (n 51) 205.

Boyle A (2018) Soft law in international law-making. In: Evans MD (ed) International law. OUP,

Google Scholar

Nasu H et al (2019) The legal authority of ASEAN as a security institution. CUP

Book Google Scholar

Cryer R et al (2019) An introduction to international criminal law and procedure, 4th edn. CUP

Journal Articles

Butler AH (2000) The doctrine of universal jurisdiction: a review of the literature. Crim Law Forum 11(3):353

Article Google Scholar

Perloff-Giles A (2018) Transnational cyber offenses: overcoming jurisdictional challenges. Yale J Int Law 43:191

Guzman AT (2012) Against consent. Virgina J Int Law 52:747

Guzman AT, Meyer TL (2010) International soft law. J Leg Anal 2(1):171

Nsereko DDN (1999) The international criminal court: jurisdictional and related issues. Crim Law Forum 10:87

Spiezia F (2022) International cooperation and protection of victims in cyberspace: welcoming protocol II to the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime. ERAForum 23(1):101

Fletcher G (2003) Against universal jurisdictio. JICJ 1:580

Ali HM (2021) “Norm subsidiarity” or “norm diffusion”? A cross-regional examination of norms in ASEAN-GCC cybersecurity governance. J Intell Confl Warf 4(1):123

Gercke M (2011) 10 years convention on cybercrime: achievements and failures of the council of Europe’s instrument in the fight against Internet-related crimes. Comput Law Rev Int 12(5):142

Schjolberg JS (2012) Peace and Justice in Cyberspace: Potential new global legal mechanisms against global cyberattacks and other global cybercrimes. In: EWI Worldwide Cybersecurity Summit Special Interest Seminar, New Delhi, October 2012

Cade NW (2012) An adaptive approach for an evolving crime: the case for an international cyber court and penal code. Brooklyn J Int Law 37(3):1139

Schjolberg S (2020) The history of Cybercrime. Schriftenreihe des Cybercrime Research Institute, vol 13, p 9

Tuvayanond V (2001) The role of the rule of law, the legal approximation and the national judiciary in ASEAN integration. Thammasat Rev 6(1):74

Conference and Working Papers

Guzman AT, Meyer TL (2010) Explaining soft law. Latin American and Caribbean Law and Economics Association (ALACDE) Annual Papers, UC Berkeley

Benincasa E The role of regional organisations in building cyber resilience: ASEAN and the EU. Pacific Forum issues & insights Vol. 20, WP 3 6/2020, 1. https://pacforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/issuesinsights_Vol20WP3-1.pdf . Accessed 9 Sept 2022

Clough J (2013) A world of difference: the Budapest convention on cybercrime and the challenges of harmonisation. In: 2nd International Serious and Organised Crime Conference, Brisbane, July 2013

Schjolberg JS (2012) Recommendations for potential new global legal mechanisms against global cyberattacks and other global cybercrimes. EWI cybercrime legal working group, vol 3

Ramadhan I (2022) ASEAN consensus and forming cybersecurity regulation in southeast asia. In: The 1st International Conference on Contemporary Risk Studies, Jakarta, March-April 2022

Emmers R (2017) ASEAN minus X: Should this formula be extended? https://hdl.handle.net/10356/86219 . Accessed 10 Oct 2022 (RSIS Commentary Nanyang Technology University)

Aimsiranun U (2020) Comparative study on the legal framework on general differentiated integration mechanisms in the European Union, APEC, and ASEAN. ADBI working paper, vol 1107. Asian Development Bank Institute, Tokyo

Nicaragua v United States of America (Merits) ICJ Rep 1986

Treaties, UN General Assembly Resolutions and Declaration

ASEAN Convention Against Trafficking in Person, Especially Women and Children (adopted 23 November 2015)

ASEAN Declaration to Prevent and Combat Cybercrime (adopted 13 November 2017)

ASEAN (2012) ASEAN protocol on enhanced dispute settlement mechanism. https://asean.org/asean-protocol-on-enhanced-dispute-settlement-mechanism/ . Accessed 30 Sept 2022

ASEAN (2017) ASEAN documents series on transnational crime: terrorism and violent extremism; drugs; cybercrime; and trafficking in persons. ASEAN Secretariat, Jakarta

Geneva Convention I (12 August 1949) art 49

Joint Statement of the Fourth ASEAN Plus China Ministerial Meeting on Transnational Crime Consultation (30 September 2015)

Kuala Lumpur Declaration Combating Transitional Crime, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia (signed on 30 September 2015)

Memorandum of Understanding between ASEAN and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on Cooperation in the Field of Non-Traditional Security Issues, Manila, Philippines (signed on 21 September 2017)

The ASEAN Declaration (Bangkok Declaration) (signed 8 August 1967)

The Budapest Convention on Cybercrime (signed 23 November 2001) TIAS 131, ETS 185

UNGA ‘Letter dated 11 October 2017 from the Permanent Representative of the Russian Federation to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General’ (16 October 2017) UN Doc (A/C.3/72/12)

Universal Declaration of Human Rights (adopted on 10 December 1948)

Other Sources

ASEAN-Australia Counter Trafficking The use and abuse of technology in human trafficking in Southeast Asia. https://www.aseanact.org/story/use-and-abuse-of-technology-in-human-trafficking-southeast-asia/ . Accessed 1 Oct 2022 (30 July 2022)

Council of Europe Cybercrime Division DGI Joining the convention on cybercrime: benefits. https://rm.coe.int/cyber-buda-benefits-june2022-en-final/1680a6f93b . Accessed 9 Sept 2022 (16 June 2022)

Hinz E Cambodia: Human trafficking crisis driven by cyberscams. https://www.dw.com/en/cambodia-human-trafficking-crisis-driven-by-cyberscams/a-63092938 . Accessed 29 Sept 2022 (Deutsche Welle, 12 September 2022)

Europol and Eurojust Public Information (2019) Common challenges in combating cybercrime. https://www.europol.europa.eu/cms/sites/default/files/documents/common_challenges_in_combating_cybercrime_2018.pdf . Accessed 10 Sept 2022

Goh G Cybercrime: Malaysia not lagging but needs to level up. https://www.digitalnewsasia.com/security/cybercrime-malaysia-not-lagging-but-needs-to-level-up . Accessed 11 Sept 2022 (Digital News Asia, 24 September 2014)

International Criminal Court Asia-Pacific States | International Criminal Court. https://asp.icc-cpi.int/states-parties/asian-states . Accessed 24 Oct 2023

International Criminal Cour Office of the prosecutor. https://www.icc-cpi.int/about/otp . Accessed 1 Oct 2022

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia Overview of capacity building activities. https://www.icty.org/en/outreach/capacity-building/overview-activities . Accessed 26 Sept 2022

Interpol ASEAN Cyberthreat Assessment 2021. https://www.interpol.int/en/News-and-Events/News/2021/INTERPOL-report-charts-top-cyberthreats-in-Southeast-Asia . Accessed 18 Sept 2022 (22 January 2021)

Russia, FSU Russia prepares new UN anti-cybercrime convention-report. https://www.rt.com/russia/384728-russia-has-prepared-new-international/ . Accessed 5 Oct 2022 (RT, 14 April 2017)

Kemp S Digital 2020: Global digital overview. https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2020-global-digital-overview . Accessed 27 Sept 2022 (DataReportal, 30 January 2020)

The Associated Press 24 more Malaysians rescued from Cambodia human traffickers. https://abcnews.go.com/International/wireStory/24-malaysians-rescued-cambodia-human-traffickers-89589335 . Accessed 29 Sept 2022 (ABC News, 9 September 2022)

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) (2021) Darknet cybercrime threats to southeast asia 2020. https://www.unodc.org/documents/southeastasiaandpacific/darknet/index.html . Accessed 1 Oct 2022

Download references

Acknowledgements

This paper was presented at the “Legal Co-operation, Harmonisation and Unification: An ASEAN Perspective” Conference. For their discussions, comments and suggestions, the authors thank the participants of the ‘Legal Cooperation, Harmonization and Unification: An ASEAN Perspective’ Conference organised by the Asian Law Centre, Melbourne Law School, The University of Melbourne; Faculty of Law, Surabaya University; School of Law, Vietnam National University Hanoi; and the International Organization of Educators and Researchers Inc. (IOER).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Albert Luk’s Chambers, Hong Kong, China

Kwan Yuen Iu

Faculteit der Rechtsgeleerdheid, Universiteit van Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Vanessa Man-Yi Wong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kwan Yuen Iu .

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This paper follows the English spelling system except for quotations of texts published that use the American spelling system in the original.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Iu, K.Y., Wong, V.MY. The trans-national cybercrime court: towards a new harmonisation of cyber law regime in ASEAN. Int. Cybersecur. Law Rev. 5 , 121–141 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1365/s43439-023-00105-x

Download citation

Received : 02 September 2023

Accepted : 26 October 2023

Published : 06 December 2023

Issue Date : March 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1365/s43439-023-00105-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Legal Harmonisation

- International Common Law

- International Law

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

By providing an email address. I agree to the Terms of Use and acknowledge that I have read the Privacy Policy .

Philippine Cybersecurity: How the country beats digital threats

The Philippines has been improving its cybersecurity measures as its digitalization efforts grow. Its Cybercrime Investigation Coordinating Center (CICC) has been spreading awareness regarding online scams so the public can defend themselves. The CICC has been deploying the latest tools, and the country has accepted more cybersecurity investments overseas.

The Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department (CPBRD) says digitalization could help the Philippine economy grow by ₱5 trillion or $97 billion by 2030. However, the CICC warns that online fraud in Metro Manila rose from 1,551 in 2022 to 4,446 in 2023, up to 186%. In response, the Philippines must bolster its cyber defenses.

This article will share some of the Pearl of the Orient’s latest cybersecurity measures. These include the CICC’s latest awareness drive, artificial intelligence tools, and the most recent company to bring cybersecurity investments.

The 3 most recent Philippine cybersecurity projects

- CitizenWatch Philippines

- Consumer Application Monitoring Systems (CAMS)

- NCC Group trains future cybersecurity pros

1. CitizenWatch Philippines

On July 28, 2023, CICC Executive Director Alexander K. Ramos and CitizenWatch Philippines Lead Convenor Orlando Oxales led the signing of a Memorandum of Agreement.

Ramos said the MOA will help CICC reach vulnerable consumers and empower them with cybersecurity training campaigns. “We would like to show to them that partnership with the government is the solution to resolving cybercrimes.”

Retired Supreme Court Justice Andres Reyes, a CICC highly technical consultant, said that consumer fraud would be one of the four major areas to be included in the proposed National Cyber Security Plan.

“It will be one of the first four policies at the top of the agenda of the cyber security plan of the Philippines because it affects not only the consumer but the poor consumer,” he said.

Oxales said internet access has become an indispensable utility for daily transactions and interactions with the digital transformation of the government and private sectors.

“CitizenWatch Philippines is one with the Cybercrime Investigation Coordinating Center’s (CICC) campaign to safeguard our digital environment. It is with honor and great enthusiasm that CitizenWatch Philippines is partnering with the CICC to fight the rising cybercrime incidents victimizing the country’s consumers,” he said.

2. Consumer Application Monitoring Systems (CAMS)

The CICC also deployed a new tool to ensure government service apps are safe against cyber threats. The agency calls it the Consumer Application Monitoring Systems or CAMS.

The institution based it on the Zero Defects principle American author and philosopher Philip Crosby introduced in his bestselling book, “Quality of Free.” ZD is the 9th principle, “Zero Defects Day,” which ensures companies leave an impact and everyone “gets the same message in the same way.”

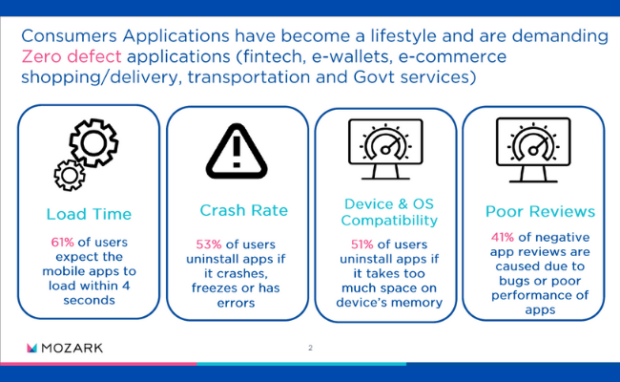

The CPBRD says the Philippines is the fastest-growing digital economy among ASEAN member-states, with an extraordinary 93% year-on-year expansion from 2020 to 2021. However, the CICC says we must address the following Philippine cybersecurity issues:

- Load time: 61% of users expect the mobile apps to load within four seconds.

- Poor reviews: 41% of negative app reviews are due to bugs or poor performance of apps.

- Crash rate: 53% of users uninstall apps if they crash, freeze, or encounter errors.

- Device & OS compatibility: 51% of users uninstall apps if they occupy too much space on their device storage.

You may also like: PH cybercriminals are using popular chat apps

That is why the Department of Information and Communications Technology Secretary Ivan John Uy deployed the CAMS platform. Here are its features:

- AI-powered vision enables CAMS to “see” errors and automate event detection.

- Also, it uses robots for multi-stage user journey automation. It could follow the steps to accessing apps by tapping the correct sequence of buttons without human intervention.

- CAMS autonomous kits allow the platform to gather location-based data. As a result, it could highlight areas that may require further assistance.

“This will be a useful tool to identify the performance and the problem with government applications,” he said.

3. NCC Group trains future cybersecurity pros

We need local professionals who would continue improving Philippine cybersecurity. Fortunately, the global cybersecurity firm NCC Group inaugurated its first Manila office on January 17, 2024.

It is also the tech firm’s second Southeast Asian office. “Our people are the ones who make our purpose possible: a global community of talented individuals working together to create a more secure digital future,” stated CEO Mike Maddison.

“We are delighted to be expanding our global footprint with our new office in Manila. The city provides an impressive balance of highly educated tech and cyber capability, and we are excited to welcome our new colleagues over the coming months.”

“Our new office in Manila gives people a great opportunity to be part of something new from the beginning, but with the added benefit of being part of an established, global company,” Country Director Saira Acuna added.

You may also like: CICC protects the Philippines from cyber threats

“I hope that Filipinos will recognize this opportunity to be part of a burgeoning industry and see NCC Group as the place where they can start or develop their cybersecurity career.”

CEO Mike Maddison, COO Kevin Brown, and Country Director Saira Acuna hosted a press briefing after the inauguration. They explained their “people-centric” approach to addressing the cybersecurity needs of their clients and “demystifying” it to promote public awareness.

The NCC Group is also working with top PH universities to improve their curricula to create job-ready cybersecurity leaders.

The Philippines is facing more cybersecurity challenges as it boosts digitalization. Fortunately, the government is doing its best to fight online threats with the best tools and training programs.

The Congressional Policy and Budget Research Department said adopting the latest technologies is the “key to boosting the competitiveness and resilience of businesses in adapting to the evolving business environment.”

Realizing this potential will help the Pearl of the Orient shine brighter with its vision of a “matatag, maginhawa, at panatag na buhay para sa lahat” (a secure, comfortable, and peaceful life for all).

Learn more about Philippine cybersecurity

What is cybersecurity.

IBM defines cybersecurity as anything that “refers to any technology, measure, or practice for preventing cyberattacks or mitigating their impact. Cybersecurity protects individuals’ and organizations’ systems, applications, computing devices, sensitive data, and financial assets against simple and sophisticated computer viruses and similar risks.

What are the latest Philippine cybersecurity threats?

The most common online scams involve business or investment opportunities. They usually promise you’ll earn huge sums of money from interest. However, your “account” may not be accessible unless you allocate more funding. Other notorious examples include social media emails, fake websites, and bogus mobile apps.

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

How should we respond to cyber threats?

You may report suspected cybercrimes through the CICC main hotline at 1326. Also, you may reach the Inter-Agency Response Center (I-ARC) at 0966 9765971 (Globe), 09477147105 (Smart), and 09914814225 (DITO). You may send concerns to the CICC Facebook page, powered by its new CYRI chatbot.

Subscribe to our technology news

Disclaimer: Comments do not represent the views of INQUIRER.net. We reserve the right to exclude comments which are inconsistent with our editorial standards. FULL DISCLAIMER

© copyright 1997-2024 inquirer.net | all rights reserved.

We use cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. By continuing, you are agreeing to our use of cookies. To find out more, please click this link.

- Expert Opinion

Using Data to Protect Data: Addressing Gaps in Cyber Threat Reporting in the Philippines

By Keith Detros, Programme Manager, Tech for Good Institute

The Philippines is the fastest growing digital economy in Southeast Asia (SEA), valued at US$ 17 billion in 2021. This growth is spurred by various factors, including a young population with a median age of 25.7 years old, an internet penetration rate of 67% , and a mobile phone penetration of 138% . Filipino internet users spend the most time online globally. COVID-19 accelerated this trend even further, as Filipinos relied on technology to continue availing of goods and services in the face of strict lockdown measures and limited movement of people.

While the rapid adoption of digital services is a welcome development, the rise in cyber-attacks and data breaches have risen in step. Private firms saw a 30% increase in ransomware attacks and 49% in web threats . The Philippine National Police (PNP) also reported a 37% increase in online scam cases , while the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) recorded a 200% increase in phishing cases . This trend has led the government to ramp up awareness campaigns on attack vectors frequently used by cyber criminals. However, there remain areas of improvement for the Philippines to handle the ever-changing cyber threat landscape.

Philippine Cybersecurity Capacity

Despite having the fastest growing digital economy, the Philippines cyber security capacity is still maturing. Based on ITU’s Global Cybersecurity Index , It scores high on the legal and cooperative measures, while coordination of institutions, policies, and strategies can be improved. An upcoming Tech for Good Institute study also sees an opportunity for the Philippines to improve its capacity to adapt in order to improve resilience.

Brain drain and lack of competitive rates have also resulted in lack of cybersecurity professionals in the country. Based on the data of International Information System Security Certification Consortium (ISC2) , a global cybersecurity professional organisation which grants the Certified Information Systems Security Professional (CISSP) – one of the most coveted certifications of cybersecurity experts – the Philippines ranked 4th in SEA with 183 CISSPs in the country as of July 2021. This translates to a ratio of 2 cybersecurity experts to every 1 million internet users in the Philippines. To put this into perspective, Singapore leads the region with 2,683 CISSPs, with a much smaller population.

In addition, the Philippines also suffers from the lack of reliable data in cybersecurity incidents due to the government not having a centralised and localised view of the kind of cyber threats that Filipinos are facing.

Improving cybersecurity manpower and data collection frameworks are therefore vital to the Philippine’s ability to maximise the benefits of the digital economy.

A Web of Issues: Policy Landscape and Unstructured Reporting Data

Over the last decade, the Philippines has been laying down the foundations to protect the data of its citizens. There are two landmark laws that govern the Philippine cybersecurity policy. First is the Data Privacy Act of 2012 , which created the National Privacy Commission (NPC) and serves as the national watchdog and main policymaking body in all matters related to privacy. Second is the Cyber crime Prevention Act of 2012 , providing the legal framework against crimes committed through digital means. The latter law created several offices including the Office of Cybercrime in the Department of Justice (DOJ), and the anti-cybercrime divisions within the NBI and the PNP. In addition, the Department of Information and Communications Technology (DICT) is also a key player in cybersecurity policymaking.

The policy landscape has created several agencies in government that respond to cyberthreats but there are overlapping duties and responsibilities that can be streamlined moving forward. For example, on the law enforcement side, PNP and the NBI have their own cybercrime divisions, but the delineation is not clear – especially among end-uses – on what cases each group covers.

On the other hand, data on cyber incidents is crucial to develop corresponding policy and incident response mechanisms. The Philippine government gathers cyber incident data through three streams:

- the National Cyber Threat Intelligence Platform which is a national platform where intelligence is shared across limited government agencies;

- the Threat Intelligence Feed where the DICT subscribes to private vendors that gives them an intelligence information on major threat activities in the world; and

- Actual Incidents Reported where the government tracks actual incidents reported by end users.

The main issue for cyber threat reporting is that there is no integrated database across government agencies, especially for the Actual Incidents Reported. End-users can choose any of the agencies they can report to, with each of the agencies having their own reporting and response mechanisms. This results in databases that are siloed and not connected to each other. There is also no uniform format for reporting cyber incidents. Since agencies keep their own records, the categories and data entry strategies are vastly different.

The Way Forward: An Integrated Cyber Threat Database

A coordinated response is key towards combating cyber threats and protecting data of governments, businesses, and individuals. A step forward is to have an integrated reporting system that would capture, aggregate and analyse local challenges end-users are facing. This integrated local threat database would complement data gathered from international partners and organisations, and would serve as the basis for a more holistic and responsive cybersecurity strategy. For the Philippines, there are several recommendations towards this goal.

- Streamline and consolidate the data gathered across several agencies. There are several policy options to enable this. One is to empower the Cybercrime Investigation and Coordinating Centre (CICC) as the main repository and data governance body when it comes to cyber vulnerabilities and incidents. A consideration here however is that CICC needs sufficient manpower to do this mandate. Another is to create a National Cybersecurity Agency (NCA) that will serve as the main policymaking body for cybersecurity, maintain an integrated database of cyber threats, and designate policy responses to the appropriate government agencies. This is akin to Singapore where the Cyber Security Agency is the focal body for cyber policy making. To have a strong mandate, this new agency can be attached to the Office of the President. This option will necessitate a reorganisation of several existing bodies and their bureaucratic relationships with a new agency. Regardless, there is a need to streamline the current process of collecting data for cyber threat reporting.

- Make reporting easy for end-users with standardised reporting and escalation procedures. It would be ideal to have a unified portal where government agencies, businesses and individuals can submit their complaints. The data format should be uniform with clear categories for reporting. With a repository of data available, data analytics can be employed to have a holistic view of cyber threats.

- Build trust and inspire confidence in the country’s cyber incident and response mechanisms. The main challenge remains encouraging the private sector and individuals to report whenever they are breached or hacked. There should be a continuous campaign highlighting the fact that not sharing information could create blindspots. And given the fact that cyber threats can rapidly spread across domains, sectors, and industries, it is important to advocate for a whole-of-society approach throughout the entire ecosystem. The government should continue to encourage information sharing to improve its capacity to handle cybercrime and data breaches.

Overall, an integrated cyber threat database would serve as a foundation for evidence-based cyber policymaking. The data gathered from the integrated data system can be used to address other weaknesses in Philippine cybersecurity. Only when the stakeholders know what it is up against can responsive capacity building measures be designed, budgets to retain talent be justified, and timely advisories against emerging cyber threats be issued.

Download Agenda

Download report, latest updates.

Shifting the Mindset from Cybersecurity to Cyber Resilience

- Posted January 22, 2024

- TFGI Reports

Sandbox to Society: Fostering Innovation in Southeast Asia

- Posted February 16, 2024

Spotlight on Southeast Asia: Evolution of Tech Regulation in the Digital Economy

- Posted January 29, 2024

Envisioning a Confident and Sustainable Digital Society in Southeast Asia

- Posted January 15, 2024

In Focus: Utilising ASEAN Free Trade Agreements with the new ASEAN Tariff Finder

Cybersecurity and cyber resilience , philippines, follow us on linkedln.

Interested in learning more about our work? Get the latest.

All rights reserved. © 2021 Tech For Good Institute

Connect with us, keep pace with the digital pulse of southeast asia.

Never miss an update or event!

Mouna Aouri

Programme Fellow

Mouna Aouri is an Institute Fellow at the Tech For Good Institute. As a social entrepreneur, impact investor, and engineer, her experience spans over two decades in the MENA region, South East Asia, and Japan. She is founder of Woomentum, a Singapore-based platform dedicated to supporting women entrepreneurs in APAC through skill development and access to growth capital through strategic collaborations with corporate entities, investors and government partners.

In this handout photo provided by the Philippine National Police Anti-Cybercrime Group, police walks inside one of the offices they raided in Las Pinas, Philippines on Tuesday June 27, 2023. Philippine police backed by commandos staged a massive raid on Tuesday and said they rescued more than 2,700 workers from China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and more than a dozen other countries who were allegedly swindled into working for fraudulent online gaming sites and other cybercrime groups. (Philippine National Police Anti-Cybercrime Group via AP)

- Copy Link copied

MANILA, Philippines (AP) — Philippine police backed by commandos staged a massive raid on Tuesday and said they rescued more than 2,700 workers from China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Indonesia and more than a dozen other countries who were allegedly swindled into working for fraudulent online gaming sites and other cybercrime groups.

The number of human trafficking victims rescued from seven buildings in Las Pinas city in metropolitan Manila and the scale of the nighttime police raid were the largest so far this year and indicated how the Philippines has become a key base of operations for cybercrime syndicates.

Cybercrime scams have become a major issue in Asia with reports of people from the region and beyond being lured into taking jobs in countries like strife-torn Myanmar and Cambodia . However, many of these workers find themselves trapped in virtual slavery and forced to participate in scams targeting people over the internet.

In May, leaders from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations agreed in a summit in Indonesia to tighten border controls and law enforcement and broaden public education to fight criminal syndicates that traffic workers to other nations, where they are made to participate in online fraud.

Brig. Gen. Sydney Hernia, who heads the national Philippine police’s anti-cybercrime unit, said police armed with warrants raided and searched the buildings around midnight in Las Pinas and rescued 1,534 Filipinos and 1,190 foreigners from at least 17 countries, including 604 Chinese, 183 Vietnamese, 137 Indonesians, 134 Malaysians and 81 Thais. There were also a few people from Myanmar, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia, Sudan, Nigeria and Taiwan.

It was not immediately clear how many suspected leaders of the syndicate were arrested.

Police raided another suspected cybercrime base at the Clark freeport in Mabalacat city in Pampanga province north of Manila in May where they took custody of nearly 1,400 Filipino and foreign workers who were allegedly forced to carry out cryptocurrency scams, police said.

Some of the workers told investigators that when they tried to quit they were forced to pay a hefty amount for unclear reasons or they feared they would be sold to other syndicates, police said, adding that workers were also forced to pay fines for perceived infractions at work.

Workers were lured with high salary offers and ideal working conditions in Facebook advertisements but later found out the promises were a ruse, officials said.

Indonesian Minister Muhammad Mahfud, who deals with political, legal and security issues, told reporters in May that Indonesia and other countries in the region have found it difficult to work with Myanmar on cybercrime and its victims.

He said ASEAN needs to make progress on a long-proposed regional extradition treaty that would help authorities prosecute offenders more rapidly and prevent a further escalation in cybercrime.

- COVID-19 Full Coverage

- Cover Stories

- Ulat Filipino

- Special Reports

- Personal Finance

- Other sports

- Pinoy Achievers

- Immigration Guide

- Science and Research

- Technology, Gadgets and Gaming

- Chika Minute

- Showbiz Abroad

- Family and Relationships

- Art and Culture

- Health and Wellness

- Shopping and Fashion

- Hobbies and Activities

- News Hardcore

- Walang Pasok

- Transportation

- Missing Persons

- Community Bulletin Board

- GMA Public Affairs

- State of the Nation

- Unang Balita

- Balitanghali

- News TV Live

PNP: Over 16K cybercrime cases probed from January to August 2023

The Philippine National Police-Anti-Cybercrime Group (PNP-ACG) said it handled a total of 16,297 cybercrime cases from January to August 2023.

This has resulted in the rescue of 4,092 victims of drug operations and human trafficking and the arrest of 397 individuals.

In a statement, the PNP-ACG said the cases this year have evolved to include the "exploitation" of new technologies such as Non-Fungible Tokens (NFTs), cryptocurrencies, and online casinos to defraud unsuspecting victims in addition to the usual cases of cybercrime.

It was able to secure 19 Warrants to Search, Seize, and Examine Computer Data; serve 214 arrest warrants; and conduct 140 entrapment operations. At least 24 cases are ongoing investigations with other units and agencies.

PNP chief Police General Benjamin Acorda Jr. said the operations against cybercrime groups are results of the police "focused agenda in advancing our information and communication technology for the conduct of honest and aggressive law enforcement operations."

The PNP reported in July a 152% increase in cybercrimes in the National Capital Region from January to June 2023 —6,250 cases compared to the 2,477 cases in the same period in 2022.

The Presidential Anti-Organized Crime Commission also conducted a conference to address the text scams which continued to proliferate despite the passage of the SIM Registration law. —LDF, GMA Integrated News

Preparing for a China war, the Marines are retooling how they’ll fight

U.s. troops are preparing for conflict on an island-hopping battlefield across asia, against an enemy force that has home-field advantage.

POHAKULOA TRAINING RANGE, Hawaii — The Marine gunner knelt on the rocky red soil of a 6,000-foot-high volcanic plain. He positioned the rocket launcher on his shoulder, focused the sights on his target, a rusted armored vehicle 400 yards away, and fired.

Two seconds later, a BANG.

“Perfect hit,” said his platoon commander.

The gunner, 23-year-old Lance Cpl. Caden Ehrhardt, is a member of the 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment, a new formation that reflects the military’s latest concept for fighting adversaries like China from remote, strategic islands in the western Pacific. These units are designed to be smaller, lighter, more mobile — and, their leaders argue, more lethal. Coming out of 20 years of land combat in the Middle East, the Marines are striving to adapt to a maritime fight that could play out across thousands of miles of islands and coastline in Asia.

Instead of launching traditional amphibious assaults, these nimbler groups are intended as an enabler for a larger joint force. Their role is to gather intelligence and target data and share it quickly — as well as occasionally sink ships with medium-range missiles — to help the Pacific Fleet and Air Force repel aggression against the United States and allies and partners like Taiwan, Japan and the Philippines.

These new regiments are envisioned as one piece of a broader strategy to synchronize the operations of U.S. soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen, and in turn with the militaries of allies and partners in the Pacific. Their focus is a crucial stretch of territory sweeping from Japan to Indonesia and known as the First Island Chain. China sees this region, which encompasses an area about half the size of the contiguous United States, as within its sphere of influence.

The overall strategy holds promise, analysts say. But it faces significant hurdles, especially if war were to break out: logistical challenges in a vast maritime region, timely delivery of equipment and new technologies complicated by budget battles in Congress, an overstressed defense industry, and uncertainty over whether regional partners like Japan would allow U.S. forces to fight from their islands. That last piece is key. Beijing sees the U.S. strategy of deepening security alliances in the Pacific as escalatory — which unnerves some officials in partner nations who fear that they could get drawn into a conflict between the two powers.

The stakes have never been higher.

Beijing’s aggressive military modernization and investment over the past two decades have challenged U.S. ability to control the seas and skies in any conflict in the western Pacific. China has vastly expanded its reach in the Pacific, building artificial islands for military outposts in the South China Sea and seeking to expand bases in the Indian and Pacific oceans — including a naval facility in Cambodia that U.S. intelligence says is for exclusive use by the People’s Liberation Army.

China not only has the region’s largest army, navy and air force, but also home-field advantage. It has about 1 million troops, more than 3,000 aircraft, and upward of 300 vessels in proximity to any potential battle. Meanwhile, U.S. ships and planes must travel thousands of miles, or rely on the goodwill of allies to station troops and weapons. The PLA also has orders of magnitude more ground-based, long-range missiles than the U.S. military.

Taiwan, a close U.S. partner, is most directly in the crosshairs. President Xi Jinping has promised to reunite, by force if necessary, the self-governing island with mainland China. A successful invasion would not only result in widespread death and destruction in Taiwan, but also have catastrophic economic consequences due to disruption of the world’s most advanced semiconductor industry and of maritime traffic in some of the world’s busiest sea lanes — the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea. That would create enormous uncertainty for businesses and consumers around the world.

“We’ve spent most of the last 20 years looking at a terrorist adversary that wasn’t exquisitely armed, that didn’t have access to the full breadth of national power,” said Col. John Lehane, the 3rd Marine Littoral Regiment’s commander. “And now we’ve got to reorient our formations onto someone that might have that capability.”

The vision and the challenge

The U.S. Marine Corps has a blueprint to fight back: a vision called Force Design that stresses the forward deployment of Marines — placing units on the front line — while making them as invisible as possible to radar and other electronic detection. The idea is to use these “stand-in” forces, up to thousands in theater at any one time, to enable the larger joint force to deploy its collective might against a major foe.

The aspiration is for the new formation to be first on the ground in a conflict, where it can gather information to send coordinates to an Air Force B-1 bomber so it can fire a missile at a Chinese frigate hundreds of miles away or send target data to a Philippine counterpart that can aim a cruise missile at a destroyer in the contested South China Sea.

The reality of the mission is daunting, experts say.

Even if you get Marines into these remote locations, “resupplying them over time is something that needs to be rehearsed and practiced repeatedly in simulated combat conditions,” said Colin Smith, a Rand Corp. researcher formerly with I Marine Expeditionary Force, whose area of responsibility includes the Pacific. “Just because you can move it in peacetime doesn’t mean you’ll be able to in warfare — especially over long periods of time.”

Though the Marines are no longer weighed down by tanks, the new unit’s Littoral Combat Team, an infantry battalion, will be operating advanced weapons that can fire missiles at enemy ships up to 100 nautical miles away to help deny an enemy access to key maritime chokepoints, such as the Taiwan and Luzon straits. By October, each Marine Littoral Regiment will have 18 Rogue NMESIS unmanned truck-based launchers capable of firing two naval strike missiles at a time.

But a single naval strike missile weighs 2,200 pounds, and resupplying these weapons in austere islands without runways requires watercraft, which move slowly, or helicopters, which can carry only a limited quantity at a time.

“You’re not very lethal with just two missiles, so you’ve got to have a whole bunch at the ready and that’s a lot more stuff to hide, which means your ability to move unpredictably goes down,’’ said Ivan Kanapathy, a Marine Corps veteran with three deployments in the western Pacific. “There’s a trade-off between lethality and mobility — mobility being a huge part of survivability in this environment.”

Though NMESIS vehicles radiate heat, and radar emits signals that can be detected, the Marines try to lower their profile by spacing out the vehicles, camouflaging them and moving them frequently, as well as communicating only intermittently. Similar tactics are being tested by Ukrainian troops on the battlefield, where despite the number of Russian sensors and drones, “if you disperse and conceal yourself, it’s possible to survive,” said Stacie Pettyjohn, director of the defense program at the Center for a New American Security.

But on smaller islands, there are fewer areas to hide, fewer road networks to move around on, “so it’s easier for China to search and eventually find what they’re looking for,” she said.

Lehane, the unit’s commander, says that the unit’s most valuable role isn’t conducting lethal strikes; it is the ability to “see things in the battlespace, get targeting data, make sense out of what is going on when maybe other people can’t.” That’s because the Pentagon expects, in a potential war with China, that U.S. satellites will be jammed or destroyed and ships’ computer networks disrupted.

China now has many more sensors — radar, sonar, satellites, electronic signals collection — in the South China Sea than the United States. That gives Beijing a formidable targeting advantage, said Gregory Poling, an expert on Southeast Asia security at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “The United States would have to expend an unacceptable amount of ordnance to degrade those capabilities to blind China,” he said.

The unit has been practicing techniques to communicate quietly. In a bare room of a cinder block building at its home base in Kaneohe, Hawaii, Marines in the regiment’s command operations center tapped on laptops on portable tables, with plastic sheets taped over the windows. In the field, the gear could be set up in a tent, packed up and moved at a moment’s notice. Intelligence analysts, some of whom speak Mandarin, were feeding information to commanders on the range at Pohakuloa, practicing connections between the command on Oahu and the infantry battalion on the Big Island.

But exercises are not real life. Indo-Pacific Command is striving to build a Joint Fires Network that will reliably connect sensors, shooters and decision-makers in the Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force. But chronic budget shortfalls, and long-standing friction between the combatant commands and the services — each of which decides independently of the commands what hardware and software to buy — have slowed development.

Even when it is fully fielded, Pettyjohn said, “the question is, is this network going to be survivable in a contested electromagnetic space? You’re going to have a lot of jamming going on.”

Shoulder-to-shoulder in the Philippines

Last April, the Marines and the rest of the Joint Force tested the new warfighting concept with their Philippine partner in a sprawling, weeks-long exercise — Balikatan — which in Tagalog means “shoulder-to-shoulder.”

With a command post on the northwestern Philippine island of Luzon, the regiment’s infantry battalion and Philippine Marine Corps’ Coastal Defense Regiment rehearsed air assaults and airfield seizures to gain island footholds, which would then be used as bases from which to gather intelligence and call in strikes.

During one live-fire exercise, the 3rd MLR helped the larger U.S. 3rd Marine Division glean location data on a target vessel — a decommissioned World War II-era Philippine ship — which U.S. and Philippine joint forces promptly sunk. Soon, the Philippine Coastal Defense Regiment expects to be able to fire its own missiles, said Col. Gieram Aragones, the regiment’s commander, in an interview from his headquarters in Manila.

“Our U.S. Marine brothers have been very helpful to us,” Aragones said. “They’ve guided us during our crawl phase. We’re trying to walk now.”

The training goes both ways. The Philippine Marines taught their American counterparts survival skills, like finding and purifying water from bamboo, and cooking pigs and goats in the jungle.

China in recent years has intensified its harassment of Philippine fishing and Coast Guard vessels. As recently as Saturday, Chinese Coast Guard ships fired water cannons at a Philippine boat conducting a lawful resupply mission to a Philippine military outpost at a contested shoal in the South China Sea. Amid such provocations, Manila has stepped up its defense partnership with the United States. A year ago, Manila announced it was granting its longtime ally access to four new military bases.

Although the two countries are treaty allies, bound to come to each other’s defense in an armed attack in the Pacific, how far Manila will go to support U.S. operations in a Taiwan conflict is an open question, said CSIS’s Poling. “Part of the reason for all the military training, the tabletop exercises, and all these new dialogues taking place is feeling out the answer,” he said.

Aragones said it’s important for the United States and the Philippines to jointly strengthen deterrence. “This is not only an issue for the Philippines,” he said. “It’s an issue for all countries whose vessels pass through this body of water [the Chinese are] trying to claim.”

Evolution in Okinawa

Some 800 miles to the north, the Marines’ newest unit, the 12th Marine Littoral Regiment, was created in November. It was formed by repurposing the 12th Marine Regiment based in Okinawa, already home to a large concentration of U.S. military personnel in Japan — a source of tension with local communities dating back decades.

This unit is intended to operate out of the islands southwest of Okinawa, the closest of which are less than 100 miles from Taiwan. Over the years, Tokyo has shifted its military focus away from northern Japan, where the Cold War threat was a Soviet land invasion, to its southwest islands.

Recent events have vindicated that shift in Tokyo’s eyes. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s bellicose response to then-House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in August 2022 — in which the PLA fired five ballistic missiles into waters near Okinawa — rattled Japan. The number of days that Chinese Coast Guard vessels sailed near the Senkaku Islands, which are administered by Japan but claimed by China, reached a record high last year.

As a result, in the last year and a half, Tokyo has announced a dramatic hike in defense spending and deepened its security partnership with the United States, the Philippines and Australia. Washington hailed Japan’s endorsement of the new U.S. Marine Corps unit’s positioning in the Southwest Islands last year as a significant advance in allied force posture.

But resentment toward U.S. troops lingers in Okinawa, rooted primarily in the disproportionate burden of hosting a major U.S. military presence. The prefecture is home to half of U.S. military personnel in Japan, while making up less than 1 percent of Japan’s land mass.

“We are concerned about rising tensions with China and the concentration of U.S. military” on Okinawa and the Japanese military buildup in the area, said Kazuyuki Nakazato, director of the Okinawa Prefecture Office in Washington. “Many Okinawan people fear that if a conflict happens, Okinawa will easily become a target.”

He argued the best way to defuse the tension is for Tokyo to deepen diplomacy and dialogue with China, not military deterrence alone.

Other local officials are more receptive to a U.S. presence, arguing that Japan alone cannot deter China. “We have no choice but to strengthen our alliance with the U.S. military,” said Itokazu Kenichi, mayor of Yonaguni town on the island of the same name, the westernmost inhabited Japanese island — just 68 miles from Taiwan .

Japan’s Self-Defense Forces has begun to establish a presence on the islands, including a surveillance station on Yonaguni, where they conducted joint exercises with other U.S. Marines last month — an interaction that has begun to accustom residents to the Marines, Kenichi said.

Ultimately, how much latitude to allow the Marines will be a political decision by the prime minister and the Diet, Japan’s parliament.

On the range at Pohakuloa, Hawaii, the littoral combat team trained for a month. They flew Skydio surveillance drones over a distant hill. They practiced machine-gun and sniper skills.

As the wind howled on a lava rock bluff one morning, Lt. Col. Mark Lenzi surveyed his gunners firing wire-guided missiles at targets 1,200 yards away. Lenzi, who served in Iraq and Afghanistan, said what’s different in the Pacific is that Marines won’t be fighting insurgents directly, but will be assigned to enable others to beat back the enemy.

“It takes the whole joint force” to deter in the Pacific, he said. “We train joint. We fight joint.”

These new forces will be at the heart of the “kill web,” he said, referring to the mix of air, sea, land, space and cyber capabilities whose efficient syncing is crucial if it comes to a battle over Taiwan.

“This one unit alone is not going to save the world,” said Col. Carrie Batson, chief of strategic communications for the Pacific Marines. “But it’s going to be vital in this fight, if it ever comes.”

Regine Cabato in Manila and Julia Mio Inuma in Tokyo contributed to this report.

What we know about the container ship that crashed into the Baltimore bridge

- The ship that crashed into the Francis Scott Key Bridge on Tuesday was the Singapore-flagged Dali.

- The container ship had been chartered by Maersk, the Danish shipping company.

- Two people were recovered from the water but six remain missing, authorities said.

A container ship crashed into a major bridge in Baltimore early Tuesday, causing its collapse into the Patapsco River.

A livestream showed vehicles traveling on the Francis Scott Key Bridge just moments before the impact at 1:28 a.m. ET.

Baltimore first responders called the situation a "developing mass casualty event" and a "dire emergency," per The Associated Press.

James Wallace, chief of the Baltimore Fire Department, said in a press conference that two people had been recovered from the water.

One was uninjured, but the other was transported to a local trauma center in a "very serious condition."

Wallace said up to 20 people were thought to have fallen into the river and some six people were still missing.

Richard Worley, Baltimore's police chief, said there was "no indication" the collision was purposeful or an act of terrorism.

Wes Moore, the governor of Maryland, declared a state of emergency around 6 a.m. ET. He said his office was in close communication with Pete Buttigieg, the transportation secretary.

"We are working with an interagency team to quickly deploy federal resources from the Biden Administration," Moore added.

Understanding why the bridge collapsed could have implications for safety, in both the shipping and civil engineering sectors.

The container ship is the Singapore-flagged Dali, which is about 984 feet long, and 157 feet wide, per a listing on VesselFinder.

An unclassified Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency report said that the ship "lost propulsion" as it was leaving port, ABC News reported.

The crew notified officials that they had lost control and warned of a possible collision, the report said, per the outlet.

The Dali's owner is listed as Grace Ocean, a Singapore-based firm, and its manager is listed as Synergy Marine, which is also headquartered in Singapore.

Shipping news outlet TradeWinds reported that Grace Ocean confirmed the Dali was involved in the collapse, but is still determining what caused the crash.

Related stories

Staff for Grace Ocean declined to comment on the collision when contacted by Business Insider.

"All crew members, including the two pilots have been accounted for and there are no reports of any injuries. There has also been no pollution," Synergy Marine said in a statement.

The company did not respond to a request for further comment from BI.

'Horrified'

Maersk chartered the Dali, with a schedule for the ship on its website.

"We are horrified by what has happened in Baltimore, and our thoughts are with all of those affected," the Danish shipping company said in a statement.

Maersk added: "We are closely following the investigations conducted by authorities and Synergy, and we will do our utmost to keep our customers informed."

Per ship tracking data, the Dali left Baltimore on its way to Colombo, the capital of Sri Lanka, at around 1 a.m., about half an hour before the crash.

The Port of Baltimore is thought to be the largest in the US for roll-on/roll-off ships carrying trucks and trailers.

Barbara Rossi, associate professor of engineering science at the University of Oxford, told BI the force of the impact on one of the bridge's supporting structures "must have been immense" to lead to the collapse.

Dr Salvatore Mercogliano, a shipping analyst and maritime historian at Campbell University, told BI: "It appears Dali left the channel while outbound. She would have been under the control of the ship's master with a Chesapeake Bay pilot onboard to advise the master.

"The deviation out of the channel is probably due to a mechanical issue as the ship had just departed the port, but you cannot rule out human error as that was the cause of the Ever Forward in 2022 just outside of Baltimore."

He was referring to the incident two years ago when the container ship became grounded for a month in Chesapeake Bay after loading up cargo at the Port of Baltimore.

The US Coast Guard found the incident was caused by pilot error, cellphone use, and "inadequate bridge resource management."

Claudia Norrgren, from the maritime research firm Veson Nautical, told BI: "The industry bodies who are here to protect against incidents like this, such as the vessel's flag state, classification society, and regulatory bodies, will step in and conduct a formal investigation into the incident. Until then, it'll be very hard for anyone to truly know what happened on board."

This may not have been the first time the Dali hit a structure.

In 2016, maritime blogs such as Shipwreck Log and ship-tracking site VesselFinder posted videos of what appears to be the stern of the same, blue-hulled container vessel scraping against a quay in Antwerp.

A representative for the Port of Antwerp told BI the Dali did collide with a quay there eight years ago but couldn't "give any information about the cause of the accident."

The Dali is listed as being built in 2015 by Hyundai Heavy Industries in South Korea.

Watch: The shipwreck at the center of a battle between China and the Philippines

- Main content

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The menace of the proliferation of cyber crime activities hampers the reach of e-government and compromises the achievement of its national goals in creating enhanced socio-economic environment for its citizens. In essence, it is tantamount to becoming a grave threat to national security. This paper sought to present how cyber crime has ...

that the implications of cybercrime in the Philippines are of an impending grave nature which threatens that national security of its people, its private sector and its government. Keywords: cybercrime, national security Introduction Cybercrime is any crime committed with the use of a computer system, or instances in which a computer

In essence, it is tantamount to becoming a grave threat to national security. This paper sought to present how cyber crime has impacted areas of both the public and private sector here in the Philippines that threaten national security of its citizens. It presented among others, a profile of cyber criminals including their tools and motives ...

Cybercrime In The Philippines: A Case Study Of National Security. Li, Jia. Preview author details. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education. Preview publication details.

However, with increasing connectivity comes increasing cyber threats. Individually, Filipinos are susceptible to data breaches and privacy violations online. On a societal level, cyberattacks by state or nonstate actors on critical infrastructure can undermine national security and impact economic activity.

The Philippines' Cybersecurity Posture (2016-2021) The Philippines' National Cybersecurity Plan 2022 defines cybersecurity as "the collection of tools, policies, risk management approaches, actions, training, best practices, assurance, and technologies that can be used to protect the cyber environment and organization and user's assets.".