How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography: The Annotated Bibliography

- The Annotated Bibliography

- Fair Use of this Guide

Explanation, Process, Directions, and Examples

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents. Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes. Annotations are descriptive and critical; they may describe the author's point of view, authority, or clarity and appropriateness of expression.

The Process

Creating an annotated bibliography calls for the application of a variety of intellectual skills: concise exposition, succinct analysis, and informed library research.

First, locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

Critically Appraising the Book, Article, or Document

For guidance in critically appraising and analyzing the sources for your bibliography, see How to Critically Analyze Information Sources . For information on the author's background and views, ask at the reference desk for help finding appropriate biographical reference materials and book review sources.

Choosing the Correct Citation Style

Check with your instructor to find out which style is preferred for your class. Online citation guides for both the Modern Language Association (MLA) and the American Psychological Association (APA) styles are linked from the Library's Citation Management page .

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th edition, 2019) for the journal citation:

Waite, L., Goldschneider, F., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 (4), 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

This example uses MLA style ( MLA Handbook , 9th edition, 2021) for the journal citation. For additional annotation guidance from MLA, see 5.132: Annotated Bibliographies .

Waite, Linda J., et al. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554. The authors, researchers at the Rand Corporation and Brown University, use data from the National Longitudinal Surveys of Young Women and Young Men to test their hypothesis that nonfamily living by young adults alters their attitudes, values, plans, and expectations, moving them away from their belief in traditional sex roles. They find their hypothesis strongly supported in young females, while the effects were fewer in studies of young males. Increasing the time away from parents before marrying increased individualism, self-sufficiency, and changes in attitudes about families. In contrast, an earlier study by Williams cited below shows no significant gender differences in sex role attitudes as a result of nonfamily living.

Versión española

Tambíen disponible en español: Cómo Preparar una Bibliografía Anotada

Content Permissions

If you wish to use any or all of the content of this Guide please visit our Research Guides Use Conditions page for details on our Terms of Use and our Creative Commons license.

Reference Help

- Next: Fair Use of this Guide >>

- Last Updated: Sep 29, 2022 11:09 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

Annotated Bibliographies

What Is An Annotated Bibliography?

What is an annotated bibliography.

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations (references) to books, articles, and documents followed by a brief summary, analysis or evaluation, usually between 100-300 words, of the sources that are cited in the paper. This summary provides a description of the contents of the source and may also include evaluative comments, such as the relevance, accuracy and quality of the source. These summaries are known as annotations.

- Annotated bibliographies are completed before a paper is written

- They can be stand-along assignments

- They can be used as a reference tool as a person works on their paper

Annotations vs. Abstracts

Abstracts are the descriptive summaries of article contents found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles that are written by the article author(s) or editor. Their purpose is to inform a reader about the topic, methodology, results and conclusion of the research of the article's author(s). The summaries are provided so that a researcher can determine whether or not the article may have information of interest to them. Abstracts do not serve an evaluative purpose.

Annotations found in bibliographies are evaluations of sources cited in a paper. They describe a work, but also critique the source by examining the author’s point of view, the strengths and weakness of the research or article hypothesis or how well the author presented their research or findings.

How to write an annotated bibliography

The creation of an annotated bibliography is a three-step process. It starts with finding and evaluating sources for your paper. Next is choosing the type or category of annotation, then writing the annotation for each different source. The final step is to choose a citation style for the bibliography.

Types of Annotated Bibliographies

Types of Annotations

Annotations come in different types, the one to use depends on the instructor’s assignment. Annotations can be descriptive, a summary, or an evaluation or a combination of descriptive and evaluation.

Descriptive/Summarizing Annotations

There are two kinds of descriptive or summarizing annotations, informative or indicative, depending on what is most important for a reader to learn about a source. Descriptive/summarizing annotations provide a brief overview or summary of the source. This can include a description of the contents and a statement of the main argument or position of the article as well as a summary of the main points. It may also describe why the source would be useful for the paper’s topic or question.

Indicative annotations provide a quick overview of the source, the kinds of questions/topics/issues or main points that are addressed by the source, but do not include information from the argument or position itself.

Informative annotations, like indicative annotations, provide a brief summary of the source. In addition, an informative annotation identifies the hypothesis, results, and conclusions presented by the source. When appropriate, they describe the author’s methodology or approach to the topic under discussion. However, they do not provide information about the sources usefulness to the paper or contains analytical or critical information about the source’s quality.

Evaluative Annotations (also known as critical or analytical)

Evaluative annotations go beyond just summarizing the source and listing out it’s key points, but also analyzes the content. It looks at the strengths and weaknesses of the article’s argument, the reliability of the presented information as well as any biases of the author. It talks about how the source may be useful to a particular field of study or the person’s research project.

Combination Annotations

Combination annotations “combine” aspects from indicative/informative and evaluative annotations and are the most common category of annotated bibliography. Combination annotations include one to two sentences summarizing or describing content, in addition to one or more sentences providing an critical evaluation.

Writing Style for Annotations

Annotations typically follow three specific formats depending on how long they are.

- Phrases – Short phrases providing the information in a quick, concise manner.

- Sentences – Complete sentences with proper punctuation and grammar, but are short and concise.

- Paragraphs – Longer annotations break the information out into different paragraphs. This format is very effective for combination annotations.

To sum it up:

An annotation may include the following information:

- A brief summary or overview of the source content

- The source’s strengths and weaknesses in presenting the argument or position

- Its conclusions

- Why the source is relevant in to field of study of the paper

- Its relationships to other studies in the field

- An evaluation of the research methodology (if applicable)

- Information about the author’s background and potential biases

- Conclusions about the usefulness of the source for the paper

Critically Analyzing Articles

In order to write an annotation for a paper source, you need to first read and then critically analyze it:

- Try to identify the topic of the source -- what is it about and is it clearly stated.

- See if you can identify the purpose of the author(s) in doing the research or writing about the topic. Is it to survey and summarize research on a topic? Is the author(s) presenting an argument based on previous research, or refuting previously published research?

- Identify the research methods used and try to identify whether they appear to be suitable or not for the stated purpose of the research.

- Was the research reported in a consistent or clear manner? Or, was the author's argument/position presented in a consistent or convincing manner? Did the author(s) fail to acknowledge and explain any limitations?

- Was the logic of the research/argument claims properly supported with convincing evidence/analysis/data? Did you spot any fallacies?

- Check whether the author(s) refers to other research and if similar studies have been done.

- If illustrations or charts are used, are they effective in presenting information?

- Analyze the sources that were used by the author(s). Did the author(s) miss any important studies they should have considered?

- Your opinion of the source -- do you agree with or are convinced of the findings?

- Your estimation of the source’s contribution to knowledge and its implications or applications to the field of study.

Worksheet for Taking Notes for Critical Analysis of Sources/Articles

Additional Resources:

Hofmann, B., Magelssen, M. In pursuit of goodness in bioethics: analysis of an exemplary article. BMC Med Ethics 19, 60 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-018-0299-9

Jansen, M., & Ellerton, P. (2018). How to read an ethics paper. Journal of Medical Ethics, 44(12), 810-813. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/medethics-2018-104997

Research & Learning Services, Olin Library, Cornell University Library Critically Analyzing Information Sources: Critical Appraisal and Analysis

Formatting An Annotated Bibliography

How do I format my annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography entry consists of two components: the Citation and the Annotation.

The citation should be formatted in the bibliographic style that your instructor has requested for the paper. Some common citation styles include APA, MLA, and Chicago. For more information on citation styles, see Writing Guides, Style Manuals and the Publication Process in the Biological & Health Sciences .

Many databases (e.g., PubMed, Academic Search Premier, Library Search on library homepage, and Google Scholar) offer the option of creating your references in various citation styles.

Look for the "cite" link -- see examples for the following resources:

University of Minnesota Library Search

Google Scholar

Sample Annotated Bibliography Entries

An example of an Evaluative Annotation , APA style (7th ed). (sample from University Libraries, University of Nevada ).

APA does not have specific formatting rules for annotations, just for the citation and bibliography.

Maak, T. (2007). Responsible leadership, stakeholder engagement, and the emergence of social capital. Journal of Business Ethics, 74, 329-343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-007-9510-5

This article focuses on the role of social capital in responsible leadership. It looks at both the social networks that a leader builds within an organization, and the links that a leader creates with external stakeholders. Maak’s main aim with this article seems to be to persuade people of the importance of continued research into the abilities that a leader requires and how they can be acquired. The focus on the world of multinational business means that for readers outside this world many of the conclusions seem rather obvious (be part of the solution not part of the problem). In spite of this, the article provides useful background information on the topic of responsible leadership and definitions of social capital which are relevant to an analysis of a public servant.

An example of an Evaluative Annotation , MLA Style (10th ed), (sample from Columbia College, Vancouver, Canada )

MLA style requires double-spacing (not shown here) and paragraph indentations.

London, Herbert. “Five Myths of the Television Age.” Television Quarterly, vol. 10, no. 1, Mar. 1982, pp. 81-69.

Herbert London, the Dean of Journalism at New York University and author of several books and articles, explains how television contradicts five commonly believed ideas. He uses specific examples of events seen on television, such as the assassination of John Kennedy, to illustrate his points. His examples have been selected to contradict such truisms as: “seeing is believing”; “a picture is worth a thousand words”; and “satisfaction is its own reward.” London uses logical arguments to support his ideas which are his personal opinion. He does not refer to any previous works on the topic. London’s style and vocabulary would make the article of interest to any reader. The article clearly illustrates London’s points, but does not explore their implications leaving the reader with many unanswered questions.

Additional Resources

University Libraries Tutorial -- Tutorial: What are citations? Completing this tutorial you will:

- Understand what citations are

- Recognize why they are important

- Create and use citations in your papers and other scholarly work

University of Minnesota Resources

Beatty, L., & Cochran, C. (2020). Writing the annotated bibliography : A guide for students & researchers . New York, NY: Routledge. [ebook]

Efron, S., Ravid, R., & ProQuest. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . New York: The Guilford Press. [ebook -- see Chapter 6 on Evaluating Research Articles]

Center for Writing: Student Writing Support

- Critical reading strategies

- Common Writing Projects (includes resources for literature reviews & analyzing research articles)

Resources from Other Libraries

Annotated Bibliographies (The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Writing An Annotated Bibliography (University of Toronto)

Annotated Bibliographies (Purdue Writing Lab, Purdue University)

Annotated Bibliography (UNSW Sydney)

What is an annotated bibliography? (Santiago Canyon College Library): Oct 17, 2017. 3:47 min.

Writing an annotated bibliography (EasyBib.com) Oct 22, 2020. 4:53 min.

Creating an annotated bibliography (Laurier University Library, Waterloo, Ontario)/ Apr 3, 2019, 3:32 min.

How to create an annotated bibliography: MLA (JamesTheDLC) Oct 23, 2019. 3:03 min.

Citing Sources

Introduction

Citations are brief notations in the body of a research paper that point to a source in the bibliography or references cited section.

If your paper quotes, paraphrases, summarizes the work of someone else, you need to use citations.

Citation style guides such as APA, Chicago and MLA provide detailed instructions on how citations and bibliographies should be formatted.

Health Sciences Research Toolkit

Resources, tips, and guidelines to help you through the research process., finding information.

Library Research Checklist Helpful hints for starting a library research project.

Search Strategy Checklist and Tips Helpful tips on how to develop a literature search strategy.

Boolean Operators: A Cheat Sheet Boolean logic (named after mathematician George Boole) is a system of logic to designed to yield optimal search results. The Boolean operators, AND, OR, and NOT, help you construct a logical search. Boolean operators act on sets -- groups of records containing a particular word or concept.

Literature Searching Overview and tips on how to conduct a literature search.

Health Statistics and Data Sources Health related statistics and data sources are increasingly available on the Internet. They can be found already neatly packaged, or as raw data sets. The most reliable data comes from governmental sources or health-care professional organizations.

Evaluating Information

Primary, Secondary and Tertiary Sources in the Health Sciences Understand what are considered primary, secondary and tertiary sources.

Scholarly vs Popular Journals/Magazines How to determine what are scholarly journals vs trade or popular magazines.

Identifying Peer-Reviewed Journals A “peer-reviewed” or “refereed” journal is one in which the articles it contains have been examined by people with credentials in the article’s field of study before it is published.

Evaluating Web Resources When searching for information on the Internet, it is important to be aware of the quality of the information being presented to you. Keep in mind that anyone can host a web site. To be sure that the information you are looking at is credible and of value.

Conducting Research Through An Anti-Racism Lens This guide is for students, staff, and faculty who are incorporating an anti-racist lens at all stages of the research life cycle.

Understanding Research Study Designs Covers case studies, randomized control trials, systematic reviews and meta-analysis.

Qualitative Studies Overview of what is a qualitative study and how to recognize, find and critically appraise.

Writing and Publishing

Citing Sources Citations are brief notations in the body of a research paper that point to a source in the bibliography or references cited section.

Structure of a Research Paper Reports of research studies usually follow the IMRAD format. IMRAD (Introduction, Methods, Results, [and] Discussion) is a mnemonic for the major components of a scientific paper. These elements are included in the overall structure of a research paper.

Top Reasons for Non-Acceptance of Scientific Articles Avoid these mistakes when preparing an article for publication.

Annotated Bibliographies Guide on how to create an annotated bibliography.

Writing guides, Style Manuals and the Publication Process in the Biological and Health Sciences Style manuals, citation guides as well as information on public access policies, copyright and plagiarism.

Research Process :: Step by Step

- Introduction

- Select Topic

- Identify Keywords

- Background Information

- Develop Research Questions

- Refine Topic

- Search Strategy

- Popular Databases

- Evaluate Sources

- Types of Periodicals

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Primary & Secondary Sources

- Organize / Take Notes

- Writing & Grammar Resources

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review

- Citation Styles

- Paraphrasing

- Privacy / Confidentiality

- Research Process

- Selecting Your Topic

- Identifying Keywords

- Gathering Background Info

- Evaluating Sources

The quality and usefulness of your bibliography will depend on your selection of sources. Define the scope of your research carefully to make sound judgments about what you include and exclude.

What is an annotated bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents that follows the appropriate style format for the discipline (MLA, APA, Chicago, etc). Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 word) descriptive and evaluative paragraph -- the annotation. Unlike abstracts, which are purely descriptive summaries often found at the beginning of scholarly journal articles or in periodical indexes, annotations are descriptive and critical.

The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited . The annotation exposes the author's point of view, clarity and appropriateness of expression, and authority.

How do I create an annotated bibliography?

- Locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that contain useful information and ideas on your topic.

- Review the items. Choose those sources that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

- Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style.

- Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope o f the item.

Include one or more sentences that:

o evaluate the authority or background of the author,

o comment on the intended audience,

o compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or

o explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

The annotation should include most, if not all, of the following elements:

- Explanation of the main purpose and scope of t he cited work;

- Brief description of the work's format and content;

- Theoretical basis and currency of the author's argument;

- Author's intellectual / academic credentials;

- Work's intended audience;

- Value and significance of the work as a contribution to the subject under consideration;

- Possible shortcomings or bias in the work;

- Any significant special features of the work (e.g., glossary, appendices, particularly good index);

- Your own brief impression of the work.

An annotated bibliography is an original work created by you for a wider audience, usually faculty and colleagues. Copying any of the above elements from the source and including it in your annotated bibliography is plagiarism and intellectual dishonesty.

SAMPLE ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY ENTRY FOR A JOURNAL ARTICLE

The following example uses APA style ( Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 6th edition, 2010) for the journal citation.

Waite, L. J., Goldschneider, F. K., & Witsberger, C. (1986). Nonfamily living and the erosion of traditional family orientations among young adults. American Sociological Review, 51 , 541-554.

This example uses MLA style ( MLA Handbook , 8th edition, 2016) for the journal citation.

Waite, Linda J., et al. "Nonfamily Living and the Erosion of Traditional Family Orientations Among Young Adults." American Sociological Review, vol. 51, no. 4, 1986, pp. 541-554.

- << Previous: Writing & Grammar Resources

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jun 13, 2024 4:27 PM

- URL: https://libguides.uta.edu/researchprocess

University of Texas Arlington Libraries 702 Planetarium Place · Arlington, TX 76019 · 817-272-3000

- Internet Privacy

- Accessibility

- Problems with a guide? Contact Us.

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

Creating an Annotated Bibliography: Home

- Citation Tools

What Is An Annotated Bibliography?

-An annotated bibliography is a list of citations to books, articles, and documents.

-Each citation is followed by a brief (usually about 150 words) descriptive and evaluative paragraph, the annotation.

-The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited.

Why Should I Write One?

1. To learn about your research topic- they help you think critically instead of just collect sources, and see how your research might fit into the overall scholarship.

2. To help other researchers- published annotated bibliographies provide a comprehensive overview of everything important that has been and is being said about that topic

What Do They Do?

Depending on your project or the assignment, your annotations may do one or more of the following.

- Summarize : Some annotations merely summarize the source. What are the main arguments? What is the point of this book or article? What topics are covered? If someone asked what this article/book is about, what would you say? The length of your annotations will determine how detailed your summary is.

- Assess : After summarizing a source, it may be helpful to evaluate it. Is it a useful source? How does it compare with other sources in your bibliography? Is the information reliable? Is this source biased or objective? What is the goal of this source?

- Reflect : Once you've summarized and assessed a source, you need to ask how it fits into your research. Was this source helpful to you? How does it help you shape your argument? How can you use this source in your research project? Has it changed how you think about your topic?

The Process

1. Locate and record citations to books, periodicals, and documents that may contain useful information and ideas on your topic.

2. Briefly examine and review the actual items. Then choose those works that provide a variety of perspectives on your topic.

3. Cite the book, article, or document using the appropriate style. Check out our pages for both AMA and APA styles.

4. Write a concise annotation that summarizes the central theme and scope of the book or article. Include one or more sentences that (a) evaluate the authority or background of the author, (b) comment on the intended audience, (c) compare or contrast this work with another you have cited, or (d) explain how this work illuminates your bibliography topic.

Blumenthal, A., Cosgrave, T., & Engle, M. (2012). How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography .

Stacks, G., Karper, E., Bisignani, D., Bisignani, D., Brizee, A. (2017). Annotated Bibliographies. Retrieved from https://www.nobts.edu/_resources/pdf/cme/student%20resources/turabian-8-resources/The%20Purdue%20OWL_Annotated%20Bibliographies.pdf

Subject Guide

- Next: Citation Tools >>

- Last Updated: May 8, 2023 4:25 PM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/annotatedbibliography

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Generate accurate MLA citations for free

- Knowledge Base

- How to create an MLA style annotated bibliography

MLA Style Annotated Bibliography | Format & Examples

Published on July 13, 2021 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on March 5, 2024.

An annotated bibliography is a special assignment that lists sources in a way similar to the MLA Works Cited list, but providing an annotation for each source giving extra information.

You might be assigned an annotated bibliography as part of the research process for a paper , or as an individual assignment.

MLA provides guidelines for writing and formatting your annotated bibliography. An example of a typical annotation is shown below.

Kenny, Anthony. A New History of Western Philosophy: In Four Parts . Oxford UP, 2010.

You can create and manage your annotated bibliography with Scribbr’s free MLA Citation Generator . Choose your source type, retrieve the details, and click “Add annotation.”

Generate accurate MLA citations with Scribbr

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text.

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Mla format for annotated bibliographies, length and content of annotations, frequently asked questions about annotated bibliographies.

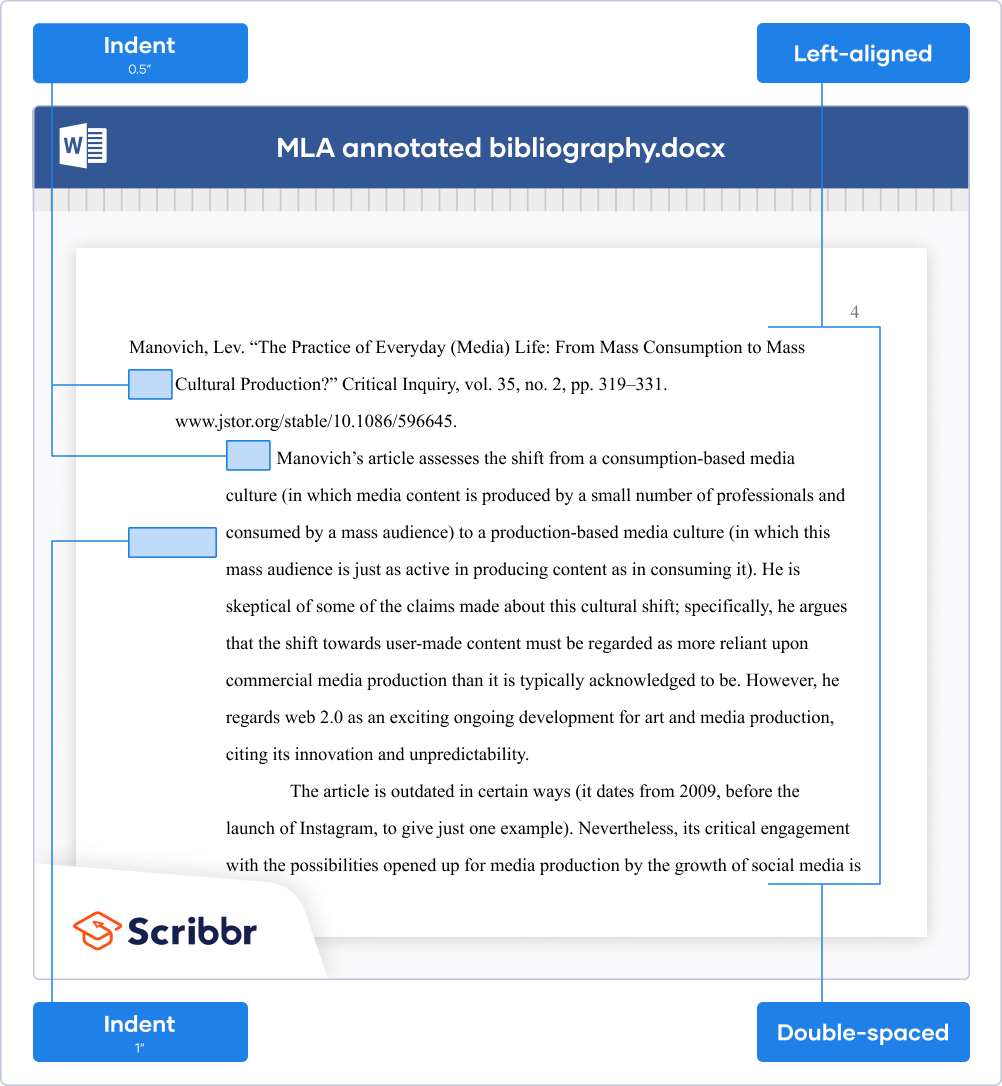

The list should be titled either “Annotated Bibliography” or “Annotated List of Works Cited.” You may be told which title to use; “bibliography” is normally used for a list that also includes sources you didn’t cite in your paper or that isn’t connected to a paper at all.

Sources are usually organized alphabetically , like in a normal Works Cited list, but can instead be organized chronologically or by subject depending on the purpose of the assignment.

The source information is presented and formatted in the same way as in a normal Works Cited entry:

- Double-spaced

- Left-aligned

- 0.5 inch hanging indent

The annotation follows on the next line, also double-spaced and left-aligned. The whole annotation is indented 1 inch from the left margin to distinguish it from the 0.5 inch hanging indent of the source entry.

- If the annotation is only one paragraph long, there’s no additional indent for the start of the paragraph.

- If there are two or more paragraphs, indent the first line of each paragraph , including the first, an additional half-inch (so those lines are indented 1.5 inches in total).

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

MLA gives some guidelines for writing the annotations themselves. They cover how concise you need to be and what exactly you should write about your sources.

Phrases or full sentences?

MLA states that it’s acceptable to use concise phrases rather than grammatically complete sentences in your annotations.

While you shouldn’t write this way in your main text, it’s acceptable in annotations because the subject of the phrase is clear from the context. It’s also fine to use full sentences instead, if you prefer.

- Broad history of Western philosophy from the ancient Greeks to the present day.

- Kenny presents a broad history of Western philosophy from the ancient Greeks to the present day.

Always use full sentences if your instructor requires you to do so, though.

How many paragraphs?

MLA states that annotations usually aim to be concise and thus are only one paragraph long. However, it’s acceptable to write multiple-paragraph annotations if you need to.

If in doubt, aim to keep your annotations short, but use multiple paragraphs if longer annotations are required for your assignment.

Descriptive, evaluative, or reflective annotations?

MLA states that annotations can describe or evaluate sources, or do both. They shouldn’t go into too much depth quoting or discussing minor details from the source, but aim to write about it in broad terms.

You’ll usually write either descriptive , evaluative , or reflective annotations . If you’re not sure what kind of annotations you need, consult your assignment guidelines or ask your instructor.

An annotated bibliography is an assignment where you collect sources on a specific topic and write an annotation for each source. An annotation is a short text that describes and sometimes evaluates the source.

Any credible sources on your topic can be included in an annotated bibliography . The exact sources you cover will vary depending on the assignment, but you should usually focus on collecting journal articles and scholarly books . When in doubt, utilize the CRAAP test !

Each annotation in an annotated bibliography is usually between 50 and 200 words long. Longer annotations may be divided into paragraphs .

The content of the annotation varies according to your assignment. An annotation can be descriptive, meaning it just describes the source objectively; evaluative, meaning it assesses its usefulness; or reflective, meaning it explains how the source will be used in your own research .

No, in an MLA annotated bibliography , you can write short phrases instead of full sentences to keep your annotations concise. You can still choose to use full sentences instead, though.

Use full sentences in your annotations if your instructor requires you to, and always use full sentences in the main text of your paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2024, March 05). MLA Style Annotated Bibliography | Format & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved July 17, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/mla/mla-annotated-bibliography/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, what is an annotated bibliography | examples & format, how to format your mla works cited page, mla format for academic papers and essays, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

How to Write an Annotated Bibliography - APA Style (7th Edition)

What is an annotation, how is an annotation different from an abstract, what is an annotated bibliography, types of annotated bibliographies, descriptive or informative, analytical or critical, to get started.

An annotation is more than just a brief summary of an article, book, website, or other type of publication. An annotation should give enough information to make a reader decide whether to read the complete work. In other words, if the reader were exploring the same topic as you, is this material useful and if so, why?

While an abstract also summarizes an article, book, website, or other type of publication, it is purely descriptive. Although annotations can be descriptive, they also include distinctive features about an item. Annotations can be evaluative and critical as we will see when we look at the two major types of annotations.

An annotated bibliography is an organized list of sources (like a reference list). It differs from a straightforward bibliography in that each reference is followed by a paragraph length annotation, usually 100–200 words in length.

Depending on the assignment, an annotated bibliography might have different purposes:

- Provide a literature review on a particular subject

- Help to formulate a thesis on a subject

- Demonstrate the research you have performed on a particular subject

- Provide examples of major sources of information available on a topic

- Describe items that other researchers may find of interest on a topic

There are two major types of annotated bibliographies:

A descriptive or informative annotated bibliography describes or summarizes a source as does an abstract; it describes why the source is useful for researching a particular topic or question and its distinctive features. In addition, it describes the author's main arguments and conclusions without evaluating what the author says or concludes.

For example:

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulties many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a legal nurse consulting business. Pointing out issues of work-life balance, as well as the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, the author offers their personal experience as a learning tool. The process of becoming an entrepreneur is not often discussed in relation to nursing, and rarely delves into only the first year of starting a new business. Time management, maintaining an existing job, decision-making, and knowing yourself in order to market yourself are discussed with some detail. The author goes on to describe how important both the nursing professional community will be to a new business, and the importance of mentorship as both the mentee and mentor in individual success that can be found through professional connections. The article’s focus on practical advice for nurses seeking to start their own business does not detract from the advice about universal struggles of entrepreneurship makes this an article of interest to a wide-ranging audience.

An analytical or critical annotation not only summarizes the material, it analyzes what is being said. It examines the strengths and weaknesses of what is presented as well as describing the applicability of the author's conclusions to the research being conducted.

Analytical or critical annotations will most likely be required when writing for a college-level course.

McKinnon, A. (2019). Lessons learned in year one of business. Journal of Legal Nurse Consulting , 30 (4), 26–28. This article describes some of the difficulty many nurses experience when transitioning from nursing to a nurse consulting business. While the article focuses on issues of work-life balance, the differences of working for someone else versus working for yourself, marketing, and other business issues the author’s offer of only their personal experience is brief with few or no alternative solutions provided. There is no mention throughout the article of making use of other research about starting a new business and being successful. While relying on the anecdotal advice for their list of issues, the author does reference other business resources such as the Small Business Administration to help with business planning and professional organizations that can help with mentorships. The article is a good resource for those wanting to start their own legal nurse consulting business, a good first advice article even. However, entrepreneurs should also use more business research studies focused on starting a new business, with strategies against known or expected pitfalls and issues new businesses face, and for help on topics the author did not touch in this abbreviated list of lessons learned.

Now you are ready to begin writing your own annotated bibliography.

- Choose your sources - Before writing your annotated bibliography, you must choose your sources. This involves doing research much like for any other project. Locate records to materials that may apply to your topic.

- Review the items - Then review the actual items and choose those that provide a wide variety of perspectives on your topic. Article abstracts are helpful in this process.

- The purpose of the work

- A summary of its content

- Information about the author(s)

- For what type of audience the work is written

- Its relevance to the topic

- Any special or unique features about the material

- Research methodology

- The strengths, weaknesses or biases in the material

Annotated bibliographies may be arranged alphabetically or chronologically, check with your instructor to see what he or she prefers.

Please see the APA Examples page for more information on citing in APA style.

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2023 11:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.umgc.edu/annotated-bibliography-apa

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

Research Methods at SCS

- Basic Strategies

Literature Reviews

Annotated bibliographies, writing the literature review, matrix for organizing sources for literature reviews / annotated bibliographies, sample literature reviews.

- Qualitative & Quantitative Methods

- Case Studies, Interviews & Focus Groups

- White Papers

A literature review is a synthesis of published information on a particular research topics. The purpose is to map out what is already known about a certain subject, outline methods previously used, prevent duplication of research, and, along these lines, reveal gaps in existing literature to justify the research project.

Unlike an annotated bibliography, a literature review is thus organized around ideas/concepts, not the individual sources themselves. Each of its paragraphs stakes out a position identifying related themes/issues, research design, and conclusions in existing literature.

An annotated bibliography is a bibliography that gives a summary of each article or book. The purpose of annotations is to provide the reader with a summary and an evaluation of the source. Each summary should be a concise exposition of the source's central idea(s) and give the reader a general idea of the source's content.

The purpose of an annotated bibliography is to:

- review the literature of a particular subject;

- demonstrate the quality and depth of reading that you have done;

- exemplify the scope of sources available—such as journals, books, websites and magazine articles;

- highlight sources that may be of interest to other readers and researchers;

- explore and organize sources for further research.

Further Reading:

- Annotated Bibliographies (Purdue OWL)

- How to Prepare an Annotated Bibliography (Cornell University)

" Literature Reviews: An Overview for Graduate Students " 2009. NC State University Libraries

Review the following websites for tips on writing a literature review:

Literature Reviews. The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Write a Literature Review: Virginia Commonwealth University.

- Matrix for Organizing Sources

Levac, J., Toal-Sullivan, D., & O`Sullivan, T. (2012). Household Emergency Preparedness: A Literature Review. Journal Of Community Health , 37 (3), 725-733. doi:10.1007/s10900-011-9488-x

Geale, S. K. (2012). The ethics of disaster management. Disaster Prevention and Management, 21 (4), 445-462. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09653561211256152

- << Previous: Basic Strategies

- Next: Qualitative & Quantitative Methods >>

- Last Updated: Jan 26, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.georgetown.edu/research

Subject Guides

Literature Review and Evidence Synthesis

- A guide to review types This link opens in a new window

- Reviews as Assignments

What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- Narrative Literature Review

- Integrative Review

- Scoping Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Review This link opens in a new window

- Other Review Types

- Subject Librarian Assistance with Reviews

- Grey Literature This link opens in a new window

- Tools for Reviews

Subject Librarians

Find your Subject Librarian Here

Description :

An annotated bibliography is a list of citations such as books, articles, and documents (a bibliography) with a brief summary and/or evaluation (annotation) for each citation. The purpose of the annotation is to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited. Unlike other types of reviews, annotated bibliographies do not have established standards. Your bibliography will be guided primarily by its purpose and instructor guidelines (for class assignments).

What to cover in an annotation:

- Main focus, purpose, or claim of the work

- The usefulness of the citation to your research topic or goal

- The reliability, trustworthiness and quality of the source

- * Always refer to the requirements of the assignment

The Process:

- Creating an annotated bibliography involves a concise background explanation, succinct analysis and informed research.

- Search and collect relevant citations

- Examine and review the articles

- These articles should include a variety of viewpoints, address disagreements and controversies around a research topic

- Cite the works using an appropriate citation style

- Write a brief annotation for each citation

Guidance for Annotated Bibliographies :

- Purdue OWL: Annotated Bibliographies

- << Previous: Reviews as Assignments

- Next: Narrative Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 12, 2024 12:34 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.binghamton.edu/literaturereview

- share facebook

- share twitter

- share pinterest

- share linkedin

- share email

Research Writing and Analysis

- NVivo Group and Study Sessions

- SPSS This link opens in a new window

- Statistical Analysis Group sessions

- Using Qualtrics

- Dissertation and Data Analysis Group Sessions

- Defense Schedule - Commons Calendar This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Flow Chart

- Research Alignment Chapter 1 This link opens in a new window

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- Annotated Bibliography

- Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Systematic Reviews & Meta-Analyses

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Problem Statement

- Purpose Statement

- Conceptual Framework

- Theoretical Framework

- Locating Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks This link opens in a new window

- Quantitative Research Questions

- Qualitative Research Questions

- Trustworthiness of Qualitative Data

- Analysis and Coding Example- Qualitative Data

- Thematic Data Analysis in Qualitative Design

- Dissertation to Journal Article This link opens in a new window

- International Journal of Online Graduate Education (IJOGE) This link opens in a new window

- Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning (JRIT&L) This link opens in a new window

What is an Annotated Bibliography?

An annotated bibliography is a summary and evaluation of a resource. According to Merriam-Webster, a bibliography is “the works or a list of the works referred to in a text or consulted by the author in its production.” Your references (APA) or Works Cited (MLA) can be considered a bibliography. A bibliography follows a documentation style and usually includes bibliographic information (i.e., the author(s), title, publication date, place of publication, publisher, etc.). An annotation refers to explanatory notes or comments on a source.

An annotated bibliography, therefore, typically consists of:

Documentation for each source you have used, following the required documentation style.

For each entry, one to three paragraphs that:

Begins with a summary ,

Evaluates the reliability of the information,

Demonstrates how the information relates to previous and future research.

Entries in an annotated bibliography should be in alphabetical order.

** Please note: This may vary depending on your professor’s requirements.

Why Write an Annotated Bibliography?

Why Write an Annotated Bibliography

Writing an annotated bibliography will help you understand your topics in-depth.

An annotated bibliography is useful for organizing and cataloging resources when developing an argument.

Formatting an Annotated Bibliography

Formatting Annotated Bibliographies

- Use 1-inch margins all around

- Indent annotations ½ inch from the left margin.

- Use double spacing.

- Entries should be in alphabetical order.

Structure of an Annotated Bibliography

This table provides a high-level outline of the structure of a research article and how each section relates to important information for developing an annotated bibliography.

| Abstract: Reviewing this section allows the reader to develop a quick understanding of the "why" the study was conducted, the methodology that was used, the most important findings, and why the findings are important. | |

| Article Section | Questions for Developing the Annotated Bibliography |

| Introduction (Provides the background and sets the stage for the study) | |

| Methodology (The how-to manual of the study) | |

| Findings/Results: This section will include the results of the data analysis. This section often provides graphs, tables, and figures that correspond with the type of analysis conducted. | |

| Discussion and Summary (The researcher provides context and relates the findings to the research questions.) | |

Annotated Bibliography Sample Outline

Author, S. A. (date of publication). Title of the article. Title of Periodical, vol. (issue), page-page. https://doi.org/XXXXXX

Write one or two paragraphs that focus on the study and its findings.

- Two or more sentences that outline the thesis, hypothesis, and population of the study.

- Two or more sentences that discuss the methodology.

- Two or more sentences that discuss the study findings.

- One or more sentences evaluating the study and its relationship to other studies.

Sample Annotated Bibliographies

Student Experience Feedback Buttons

Was this resource helpful.

- << Previous: Step 5: Illustrate

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 9, 2024 3:24 PM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/researchtools

MLA Citation Guide

- Paper Format

- Books/eBooks

- Annotated Bibliography

Annotated Bibliographies

An annotated bibliography includes a summary and/or evaluation of each source, which is called an annotation. Depending on your assignment, your annotations may include one or more of the following:

Summarize : Some annotations merely summarize the source.

- What are the main arguments?

- What is the point of this book or article?

- What topics are covered?

Assess : After you summarize a source, it may be helpful to evaluate it.

- Is it a useful source?

- How does it compare with other sources in your bibliography?

- Is the information reliable?

- Is it this source biased or objective?

- What is the goal of this source?

Reflect : Next, determine how the source fits into your research.

- Was this source helpful to you?

- How does it help you shape your argument?

- How can you use this source in your research project?

- Has it changed how you think about your topic?

Use the links below to access more information and samples.

- << Previous: More

- Next: Ask Us >>

- Report an Online Accessibility Issue

- Report a Problem

- URL: https://libguides.dcccd.edu/MLACitation

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 10:15 AM

- Login to LibApps

- Search this Guide Search

| --> | |||||

- Sojourner Truth Library

Annotated Bibliographies in the Social Sciences

- Planning Your Annotated Bibliography

- Finding Articles and Taking Notes

What is synthesis?

From the University of Arizona :

What is synthesis? At the very basic level, synthesis refers to combining multiple sources and ideas. As a writer, you will use information from several sources to create new ideas based on your analysis of what you have read.

How is synthesis different from summarizing? When asked to synthesize sources and research, many writers start to summarize individual sources. However, this is not the same as synthesis. In a summary, you share the key points from an individual source and then move on and summarize another source. In synthesis, you need to combine the information from those multiple sources and add your own analysis of the literature. This means that each of your paragraphs will include multiple sources and citations, as well as your own ideas and voice.

What steps do I need to take to reach synthesis? To effectively synthesize the literature, you must first critically read the research on your topic. Then, you need to think about how all of the ideas and findings are connected. One great way to think about synthesis is to think about the authors of the research discussing the topic at a research conference. They would not individually share summaries of their research; rather, the conversation would be dynamic as they shared similarities and differences in their findings. As you write your paragraphs, focus on a back and forth conversation between the researchers.

In addition to a matrix, as you critically read your sources, take note of the following:

- Do any authors disagree with another author?

- Does one author extend the research of another author?

- Are the authors all in agreement?

- Does any author raise new questions or ideas about the topic?

More information on the process of synthesizing information.

- Video on synthesizing academic articles. (RECOMMENDED!)

- Create a Synthesis Matrix As you do a quick-read of the articles you've gathered, start to keep a list of the themes/subtopics that appear in each article. Notice when a theme shows up in multiple articles.

- << Previous: Finding Articles and Taking Notes

- Last Updated: Sep 6, 2023 2:21 PM

- URL: https://newpaltz.libguides.com/annotatedbibliography

14.1 Compiling Sources for an Annotated Bibliography

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Integrate your ideas with ideas from related sources.

- Locate, compile, and evaluate primary, secondary, and tertiary research materials related to your topic.

A bibliography is a list of the sources you use when doing research for a project or composition. Named for the Greek terms biblion , meaning “book,” and graphos , meaning “something written,” bibliographies today compile more than just books. Often they include academic journal articles, periodicals, websites, and multimedia texts such as videos. A bibliography alone, at the end of a research work, also may be labeled “References” or “Works Cited,” depending on the citation style you are using. The bibliography lists information about each source, including author, title, publisher, and publication date. Each set of source information, or each individual entry, listed in the bibliography or noted within the body of the composition is called a citation .

Bibliographies include formal documentation entries that serve several purposes:

- They help you organize your own research on a topic and narrow your topic, thesis, or argument.

- They help you build knowledge.

- They strengthen your arguments by offering proof that your research comes from trustworthy sources.

- They enable readers to do more research on the topic.

- They create a community of researchers, thus adding to the ongoing conversation on the research topic.

- They give credit to authors and sources from which you draw and support your ideas.

Annotated bibliography expand on typical bibliographies by including information beyond the basic citation information and commentary on the source. Although they present each formal documentation entry as it would appear in a source list such as a works cited page, an annotated bibliography includes two types of additional information. First, following the documentation entry is a short description of the work, including information about its authors and how it was or can be used in a research project. Second is an evaluation of the work’s validity, reliability, and/or bias. The purpose of the annotation is to summarize, assess, and reflect on the source. Annotations can be both explanatory and analytical, helping readers understand the research you used to formulate your argument. An annotated bibliography can also help you demonstrate that you have read the sources you will potentially cite in your work. It is a tool to assist in the gathering of these sources and serves as a repository. You won’t necessarily use all the sources cited in your annotated bibliography in your final work, but gathering, evaluating, and documenting these sources is an integral part of the research process.

Compiling Sources

Research projects and compositions, particularly argumentative or position texts, require you to collect sources, devise a thesis, and then support that thesis through analysis of the evidence, including sources, you have compiled. With access to the Internet and an academic library, you will rarely encounter a shortage of sources for any given topic or argument. The real challenge may be sorting through all the available sources and determining which will be useful.

The first step in completing an annotated bibliography is to locate and compile sources to use in your research project. At the beginning, you do not need to be highly selective in this process, as you may not ultimately use every source. Therefore, gather any materials—including books, websites, professional journals, periodicals, and documents—that you think may contain valuable ideas about your topic. But where do you find sources that relate to your argument? And how do you choose which sources to use? This section will help you answer those questions and choose sources that will both enhance and challenge your claim, allowing you to confront contradictory evidence and synthesize ideas, or combine ideas from various sources, to produce a well-constructed original argument. See Research Process: Accessing and Recording Information for more information about sources and synthesizing information.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

In your research, you likely will use three types of sources: primary, secondary, and tertiary. During any research project, your use of these sources will depend on your topic, your thesis, and, ultimately, how you intend to use them. In all likelihood, you will need to seek out all three.

Primary Sources

Primary sources allow you to create your own analysis with the appropriate rhetorical approach. In the humanities disciplines, primary sources include original documents, data, images, and other compositions that provide a firsthand account of an event or a time in history. Typically, primary sources are created close in time to the event or period they represent and may include journal or diary entries, newspaper articles, government records, photographs, artworks, maps, speeches, films, and interviews. In scientific disciplines, primary sources provide information such as scientific discoveries, raw data, experimental and research results, and clinical trial findings. They may include published studies, scientific journal articles, and proceedings of meeting or conferences.

Primary sources also can include student-conducted interviews and surveys. Other primary sources may be found on websites such as the Library of Congress , the Historical Text Archive , government websites, and article databases. In all academic areas, primary sources are fact based, not interpretive. That is, they may be commenting on or interpreting something else, but they themselves are the source. For example, an article written during the 1840s condemning the practice of enslavement may interpret events occurring then, but it is a primary source document of its time.

Secondary Sources

Secondary sources , unlike primary sources, are interpretive. They often provide a secondhand account of an event or research results, analyze or clarify primary sources and scientific discoveries, or interpret a creative work. These sources are important for supporting or challenging your argument, addressing counterarguments, and synthesizing ideas. Secondary sources in the humanities disciplines include biographies, literary criticism, and reviews of the fine arts, among other sources. In the scientific disciplines, secondary sources encompass analyses of scientific studies or clinical trials, reviews of experimental results, and publications about the significance of studies or experiments. In some instances, the same item can serve as both a primary and a secondary source, depending on how it is used. For example, a journal article in which the author analyzes the impact of a clinical trial would serve as a secondary source. But if you instead count the number of journal articles that feature reports on a particular clinical trial, you might use them as primary sources because they would then serve as data points.

Table 14.1 provides examples of how primary and secondary sources often relate to one another.

| Wilfred Owen’s poem “Dulce et Decorum est” | Essay analyzing World War I poetry | |

| Raw data from a study testing the effects of a medication on bipolar disorder | Book evaluating different approaches to treating bipolar disorder in patients | |

| Transcript of John F. Kennedy’s inauguration speech | Website analyzing the themes present in John F. Kennedy’s inauguration speech | |

| Diary of a soldier who fought in the Civil War | Textbook entry about the battles of the Civil War | |

| Native American pottery | Newspaper article about the importance of honoring Native American art | |

| Recording of a live concert | Critical review of a concert published in a magazine |

Tertiary Sources

In addition to primary and secondary sources, you can use a tertiary source to summarize or digest information from primary and/or secondary sources. Because tertiary sources often condense information, they usually do not provide enough information on their own to support claims. However, they often contain a variety of citations that can help you identify and locate valuable primary and secondary sources. Researchers often use tertiary sources to find general, historical, or background information as well as a broad overview of a topic. Tertiary sources frequently placed in the secondary-source category include reference materials such as encyclopedias, textbooks, manuals, digests, and bibliographies. For more discussion on sources, see The Research Process: Where to Look for Existing Sources .

Authoritative Sources

Not all sources are created equally. You likely know already that you must vet sources—especially those you find on the Internet—for legitimacy, validity, and the presence of bias. For example, you probably know that the website Wikipedia is not considered a trustworthy source because it is open to user editing. This accessibility means the site’s authority cannot be established and, therefore, the source cannot effectively support or refute a claim you are attempting to make, though you can use it at times to point you to reliable sources. While so-called bad sources may be easy to spot, researchers may have more difficulty discriminating between sources that are authoritative and those that pose concerns. In fact, you may encounter a general hierarchy of sources in your compilation. Understanding this hierarchy can help you identify which sources to use and how to use them in your research.

Peer-Reviewed Academic Publications

This first tier of sources—the gold standard of research—includes academic literature, which consists of textbooks, essays, journals, articles, reports, and scholarly books. As scholarly works, these sources usually provide strong evidence for an author’s claims by reflecting rigorous research and scrutiny by experts in the field. These types of sources are most often published, sponsored, or supported by academic institutions, often a university or an academic association such as the Modern Language Association (MLA) . Such associations exist to encourage research and collaboration within their discipline, mostly through publications and conferences. To be published, academic works must pass through a rigorous process called peer review , in which scholars in the field evaluate it anonymously. You can find peer-reviewed academic sources in library catalogs, in article databases, and through Google Scholar online. Sometimes these sources require a subscription to access, but students often receive access through their school.

Academic articles, particularly in the social and other sciences, generally have most or all of the following sections, a structure you might recognize if you have written lab reports in science classes:

- Abstract . This short summary covers the purpose, methods, and findings of the paper. It may discuss briefly the implications or significance of the research.

- Introduction . The main part of the paper begins with an introduction that presents the issue or main idea addressed by the research, establishes its importance, and poses the author’s thesis.

- Review . Next comes an overview of previous academic research related to the topic, including a synthesis that makes a case for why the research is important and necessary.

- Data and Methods . The main part of the original research begins with a description of the data and methods used, including what data or information the author collected and how the author used it.

- Results . Data and methods are followed by results, detailing the significant findings from the experiment or research.

- Conclusion . In the conclusion, the author discusses the results in the context of the bigger picture, explaining the author’s position on how these results relate to the earlier review of literature and their significance in the broad scope of the topic. The author also may propose future research needs or point out unanswered questions.

- Works Cited or References . The paper ends with a list of all sources the author used in the research, including the review of literature. This often-overlooked portion of the composition is critical in evaluating the credibility of any paper that involves research.

Credible Nonacademic Sources

These sources, including articles, books, and reports, are second in authority only to peer-reviewed academic publications. Credible nonacademic sources are often about current events or discoveries not yet reviewed in academic circles and often provide a wider-ranging outlook on your topic. Peer-reviewed texts tend to be narrow and specific, whereas nonacademic texts from well-researched sources are often more accessible and can offer a broader perspective. These three major categories generally provide quality sources:

- Information, white papers, and reports from government and international agencies such as the United Nations , the World Health Organization , and the United States government

- Longer articles and reports from major newspapers, broadcast media, and magazines that are well regarded in academic circles, including the New York Times , the Wall Street Journal , the BBC, and the Economist

- Nonacademic books written by authors with expertise and credentials, who support their ideas with well-sourced information

To find nonacademic sources, search for .gov or .org sites related to your topic. A word of caution, however: know that sources ending in .org are often advocacy sites and, consequently, inherently biased toward whatever cause they are advocating. You also can look at academic article databases and search articles from major newspapers and magazines, both of which can be found online.

Short Informational Texts from Credible Websites and Periodicals

The next most authoritative sources are shorter newspaper articles or other pieces on credible websites. These articles tend to be limited in scope, as their authors report on a single issue or event. Although they do not often provide in-depth analysis, they can be a source of credible facts to support your argument. Alternatively, they can point you in the direction of more detailed or rigorous sources that will enhance your research by tracing the original texts or sources on which the articles are based. Usually, you can find these sources through Internet searches, but sometimes you may have difficulty determining their credibility.

Judging Credibility

To judge credibility, begin by looking for the author or organization publishing the information. Most periodical compositions contain a short “About the Author” blurb at the beginning or end of the article and often include a link to the author’s credentials or to more information about them. Using this information, you can begin to determine their expertise and, potentially, any agenda the author or organization may have. For example, expect a piece discussing side effects of medical marijuana written by a doctor to present more expertise than the same piece written by a political lobbyist. You also can determine whether bias is present; for example, the organization may promote a particular way of thinking or have an agenda that will influence the content and language of the composition. In general, look for articles written with neutral expertise.

The CRAAP Test

You may find the CRAAP test a helpful and easy-to-remember tool for testing credibility. This checklist provides you with a method for evaluating any source for both reliability and credibility. CRAAP stands for Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose. The CRAAP test, as shown in Table 14.2 , includes questions that can be asked of any source.

| Currency | When was the information published, revised, or updated? Does your topic require current information? Are links within the source current? |

| Relevance | Does the information relate to your topic or support your thesis? Who is the intended audience of the source? What is the purpose of the source? |

| Authority | Who is the publisher, sponsor, or source? What are the author’s credentials and/or qualifications? Does the URL reveal anything about the source? |

| Accuracy | Where does the information come from? What evidence is used to support the information, and can it be verified? Are there elements of bias? Has the information been reviewed? |

| Purpose | What is the author’s purpose for creating the source? Is the information based on facts, opinion, or propaganda? What biases are present? Are biases recognized? |

Sources with Clear Bias or Unclear Authority

The final type of source encompasses nearly everything else. Although they cannot be considered credible or valid to support your argument or claims, these sources are not necessarily useless. Especially when you are compiling sources at the beginning of a project, those with clear bias or unclear authority can be useful as you explore all facets of a topic, including positions within an argument. These sources also can help you identify topics on which to base your search terms and can even point you toward more credible sources.

Locating Sources