5 Current Issues in the Field of Early Childhood Education

Learning Objectives

Objective 1: Identify current issues that impact stakeholders in early childhood care and education.

Objective 2: Describe strategies for understanding current issues as a professional in early childhood care and education.

Objective 3: Create an informed response to a current issue as a professional in early childhood care and education.

Current Issues in the Field—Part 1

There’s one thing you can be sure of in the field of early childhood: the fact that the field is always changing. We make plans for our classrooms based on the reality we and the children in our care are living in, and then, something happens in that external world, the place where “life happens,” and our reality changes. Or sometimes it’s a slow shift: you go to a training and hear about new research, you think it over, read a few articles, and over time you realize the activities you carefully planned are no longer truly relevant to the lives children are living today, or that you know new things that make you rethink whether your practice is really meeting the needs of every child.

This is guaranteed to happen at some point. Natural events might occur that affect your community, like forest fires or tornadoes, or like COVID-19, which closed far too many child care programs and left many other early educators struggling to figure out how to work with children online. Cultural and political changes happen, which affect your children’s lives, or perhaps your understanding of their lives, like the Black Lives Matter demonstrations that brought to light how much disparity and tension exist and persist in the United States. New information may come to light through research that allows us to understand human development very differently, like the advancements in neuroscience that help us understand how trauma affects children’s brains, and how we as early educators can counteract those affects and build resilience.

And guess what—all this change is a good thing! Read this paragraph slowly—it’s important! Change is good because we as providers of early childhood care and education are working with much more than a set of academic skills that need to be imparted to children; we are working with the whole child, and preparing the child to live successfully in the world. So when history sticks its foot into our nice calm stream of practice, the waters get muddied. But the good news is that mud acts as a fertilizer so that we as educators and leaders in the field have the chance to learn and grow, to bloom into better educators for every child, and, let’s face it, to become better human beings!

The work of early childhood care and education is so full, so complex, so packed with details to track and respond to, from where Caiden left his socks, to whether Amelia’s parents are going to be receptive to considering evaluation for speech supports, and how to adapt the curriculum for the child who has never yet come to circle time. It might make you feel a little uneasy—or, let’s face it, even overwhelmed—to also consider how the course of history may cause you to deeply rethink what you do over time.

That’s normal. Thinking about the complexity of human history while pushing Keisha on the swings makes you completely normal! As leaders in the field, we must learn to expect that we will be called upon to change, maybe even dramatically, over time.

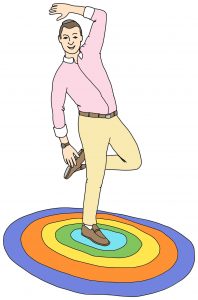

Let me share a personal story with you: I had just become director of an established small center, and was working to sort out all the details that directing encompassed: scheduling, billing policies, and most of all, staffing frustrations about who got planning time, etc. But I was also called upon to substitute teach on an almost daily basis, so there was a lot of disruption to my carefully made daily plans to address the business end, or to work with teachers to seek collaborative solutions to long-standing conflict. I was frustrated by not having time to do the work I felt I needed to do, and felt there were new small crises each day. I couldn’t get comfortable with my new position, nor with the way my days were constantly shifting away from my plans. It was then that a co-worker shared a quote with me from Thomas F. Crum, who writes about how to thrive in difficult working conditions: “Instead of seeing the rug being pulled from under us, we can learn to dance on a shifting carpet”.

Wow! That gave me a new vision, one where I wasn’t failing and flailing, but could become graceful in learning to be responsive to change big and small. I felt relieved to have a different way of looking at my progress through my days: I wasn’t flailing at all—I was dancing! Okay, it might be a clumsy dance, and I might bruise my knees, but that idea helped me respond to each day’s needs with courage and hope.

I especially like this image for those of us who work with young children. I imagine a child hopping around in the middle of a parachute, while the other children joyfully whip their corners up and down. The child in the center feels disoriented, exhilarated, surrounded by shifting color, sensation, and laughter. When I feel like there’s too much change happening, I try to see the world through that child’s eyes. It’s possible to find joy and possibility in the disorientation, and the swirl of thoughts and feelings, and new ways of seeing and being that come from change.

Key Takeaways

Our practices in the classroom and as leaders must constantly adapt to changes in our communities and our understanding of the world around us, which gives us the opportunity to continue to grow and develop.

You are a leader, and change is happening, and you are making decisions about how to move forward, and how to adapt thoughtfully. The good news is that when this change happens, our field has really amazing tools for adapting. We can develop a toolkit of trusted sources that we can turn to to provide us with information and strategies for ethical decision making.

If You’re Afraid of Falling…

One of the most important of these is the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, which expresses a commitment to core values for the field, and a set of principles for determining ethical behavior and decision-making. As we commit to the code, we commit to:

- Appreciate childhood as a unique and valuable stage of the human life cycle

- Base our work on knowledge of how children develop and learn

- Appreciate and support the bond between the child and family

- Recognize that children are best understood and supported in the context of family, culture,* community, and society

- Respect the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of each individual (child, family member, and colleague)

- Respect diversity in children, families, and colleagues

- Recognize that children and adults achieve their full potential in the context of relationships that are based on trust and respect.

If someone asked us to make a list of beliefs we have about children and families, we might not have been able to come up with a list that looked just like this, but, most of us in the field are here because we share these values and show up every day with them in our hearts.

The Code of Ethical Conduct can help bring what’s in your heart into your head. It’s a complete tool to help you think carefully about a dilemma, a decision, or a plan, based on these values. Sometimes we don’t make the “right” decision and need to change our minds, but as long as we make a decision based on values about the importance of the well-being of all children and families, we won’t be making a decision that we will regret.

An Awfully Big Current Issue—Let’s Not Dance Around It

In the field of early childhood, issues of prejudice have long been important to research, and in this country, Head Start was developed more than 50 years ago with an eye toward dismantling disparity based on ethnicity or skin color (among other things). However, research shows that this gap has not closed. Particularly striking, in recent years, is research addressing perceptions of the behavior of children of color and the numbers of children who are asked to leave programs.

In fact, studies of expulsion from preschool showed that black children were twice as likely to be expelled as white preschoolers, and 3.6 times as likely to receive one or more suspensions. This is deeply concerning in and of itself, but the fact that preschool expulsion is predictive of later difficulties is even more so:

Starting as young as infancy and toddlerhood, children of color are at highest risk for being expelled from early childhood care and education programs. Early expulsions and suspensions lead to greater gaps in access to resources for young children and thus create increasing gaps in later achievement and well-being… Research indicates that early expulsions and suspensions predict later expulsions and suspensions, academic failure, school dropout, and an increased likelihood of later incarceration.

Why does this happen? It’s complicated. Studies on the K-12 system show that some of the reasons include:

- uneven or biased implementation of disciplinary policies

- discriminatory discipline practices

- school racial climate

- under resourced programs

- inadequate education and training for teachers on bias

In other words, educators need more support and help in reflecting on their own practices, but there are also policies and systems in place that contribute to unfair treatment of some groups of children.

Key Takeaway

So…we have a lot of research that continues to be eye opening and cause us to rethink our practices over time, plus a cultural event—in the form of the Black Lives Matter movement—that push the issue of disparity based on skin color directly in front of us. We are called to respond. You are called to respond.

How Will I Ever Learn the Steps?

Woah—how do I respond to something so big and so complex and so sensitive to so many different groups of people?

As someone drawn to early childhood care and education, you probably bring certain gifts and abilities to this work.

- You probably already feel compassion for every child and want every child to have opportunities to grow into happy, responsible adults who achieve their goals. Remember the statement above about respecting the dignity and worth of every individual? That in itself is a huge start to becoming a leader working as an advocate for social justice.

- You may have been to trainings that focus on anti-bias and being culturally responsive.

- You may have some great activities to promote respect for diversity, and be actively looking for more.

- You may be very intentional about including materials that reflect people with different racial identities, genders, family structures.

- You may make sure that each family is supported in their home language and that multilingualism is valued in your program.

- You may even have spent some time diving into your own internalized biases.

This list could become very long! These are extremely important aspects of addressing injustice in early education which you can do to alter your individual practice with children.

As a leader in the field, you are called to think beyond your own practice. As a leader you have the opportunity—the responsibility!—to look beyond your own practices and become an advocate for change. Two important recommendations (of many) from the NAEYC Advancing Equity in Early Childhood Education Position Statement, another important tool:

Speak out against unfair policies or practices and challenge biased perspectives. Work to embed fair and equitable approaches in all aspects of early childhood program delivery, including standards, assessments, curriculum, and personnel practices.

Look for ways to work collectively with others who are committed to equity. Consider it a professional responsibility to help challenge and change policies, laws, systems, and institutional practices that keep social inequities in place.

One take away I want you to grab from those last sentences: You are not alone. This work can be, and must be, collective.

As a leader, your sphere of influence is bigger than just you. You can influence the practices of others in your program and outside of it. You can influence policies, rules, choices about the tools you use, and ultimately, you can even challenge laws that are not fair to every child.

Who’s on your team? I want you to think for a moment about the people who help you in times where you are facing change. These are the people you can turn to for an honest conversation, where you can show your confusion and fear, and they will be supportive and think alongside you. This might include your friends, your partner, some or all of your coworkers, a former teacher of your own, a counselor, a pastor. Make a quick list of people you can turn to when you need to do some deep digging and ground yourself in your values.

And now, your workplace team: who are your fellow advocates in your workplace? Who can you reach out to when you realize something might need to change within your program?

Wonderful. You’ve got other people to lean on in times of change. More can be accomplished together than alone. Let’s consider what you can do:

What is your sphere of influence? What are some small ways you can create room for growth within your sphere of influence? What about that workplace team? Do their spheres of influence add to your own?

Try drawing your sphere of influence: Draw yourself in the middle of the page, and put another circle around yourself, another circle around that, and another around that. Fill your circles in:

- Consider the first circle your personal sphere. Brainstorm family and friends who you can talk to about issues that are part of your professional life. You can put down their names, draw them, or otherwise indicate who they might be!

- Next, those you influence in your daily work, such as the children in your care, their families, maybe your co-workers land here.

- Next, those who make decisions about the system you are in—maybe this is your director or board, or even a PTA.

- Next, think about the early childhood care and education community you work within. What kind of influence could you have on this community? Do you have friends who work at other programs you can have important conversations with to spread ideas? Are you part of a local Association for the Education of Young Children (AEYC)? Could you speak to the organizers of a local conference about including certain topics for sessions?

- And finally, how about state (and even national) policies? Check out The Children’s Institute to learn about state bills that impact childcare. Do you know your local representatives? Could you write a letter to your senator? Maybe you have been frustrated with the slow reimbursement and low rates for Employment Related Day Care subsidies and can find a place to share your story. You can call your local Child Care Resource and Referral, your local or state AEYC chapter, or visit childinst.org to find out how you can increase your reach! It’s probably a lot farther than you think!

Break It Down: Systemic Racism

When you think about injustice and the kind of change you want to make, there’s an important distinction to understand in the ways injustice happens in education (or anywhere else). First, there’s personal bias and racism, and of course it’s crucial as an educator to examine ourselves and our practices and responses. We all have bias and addressing it is an act of courage that you can model for your colleagues.

In addition, there’s another kind of bias and racism, and it doesn’t live inside of individual people, but inside of the systems we have built. Systemic racism exists in the structures and processes that have come into place over time, which allow one group of people a greater chance of succeeding than other specific groups of people.

Key Takeaways (Sidebar)

Systemic racism is also called institutional racism, because it exists – sometimes unquestioned – within institutions themselves.

In early childhood care and education, there are many elements that were built with middle class white children in mind. Many of our standardized tests were made with middle class white children in mind. The curriculum we use, the assessments we use, the standards of behavior we have been taught; they may have all been developed with middle class white children in mind.

Therefore it is important to consider whether they adequately and fairly work for all of the children in your program community. Do they have relevance to all children’s lived experience, development, and abilities? Who is being left out?

Imagine a vocabulary assessment in which children are shown common household items including a lawn mower…common if you live in a house; they might well be unfamiliar to a three-year-old who lives in an apartment building, however. The child may end up receiving a lower score, though their vocabulary could be rich, full of words that do reflect the objects in their lived experience.

The test is at fault, not the child’s experience. Yet the results of that test can impact the way educators, parents, and the child see their ability and likelihood to succeed.

You Don’t Have to Invent the Steps: Using an Equity Lens

In addition to the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct and Equity Statement, another tool for addressing decision-making is an equity lens. To explain what an equity lens is, we first need to talk about equity. It’s a term you may have heard before, but sometimes people confuse it with equality. It’s a little different – equity is having the resources needed to be successful.

There’s a wonderful graphic of children looking over a fence at a baseball game. In one frame, each child stands at the fence; one is tall enough to see over the top; another stands tip-toe, straining to see; and another is simply too short. This is equality—everyone has the same chance, but not everyone is equally prepared. In the frame titled equity, each child stands on a stool just high enough so that they may all see over the fence. The stools are the supports they need to have an equitable outcome—being able to experience the same thing as their friend.

Seeking equity means considering who might not be able to see over the fence and figuring out how to build them a stool so that they have the same opportunity.

An equity lens, then, is a tool to help you look at decisions through a framework of equity. It’s a series of questions to ask yourself when making decisions. An equity lens is a process of asking a series of questions to better help you understand if something (a project, a curriculum, a parent meeting, a set of behavioral guidelines) is unfair to specific individuals or groups whose needs have been overlooked in the past. This lens might help you to identify the impact of your decisions on students of color, and you can also use the lens to consider the impact on students experiencing poverty, students in nontraditional families, students with differing abilities, students who are geographically isolated, students whose home language is other than English, etc.) The lens then helps you determine how to move past this unfairness by overcoming barriers and providing equitable opportunities to all children.

Some states have adopted a version of the equity lens for use in their early learning systems. Questions that are part of an equity lens might include:

- What decision is being made, and what kind of values or assumptions are affecting how we make the decision?

- Who is helping make the decision? Are there representatives of the affected group who get to have a voice in the process?

- Does the new activity, rule, etc. have the potential to make disparities worse? For instance, could it mean that families who don’t have a car miss out on a family night? Or will it make those disparities better?

- Who might be left out? How can we make sure they are included?

- Are there any potential unforeseen consequences of the decision that will impact specific groups? How can we try to make sure the impact will be positive?

You can use this lens for all kinds of decisions, in formal settings, like staff meetings, and you can also work to make them part of your everyday thinking. I have a sticky note on my desk that asks “Who am I leaving out”? This is an especially important question if the answer points to children who are people of color, or another group that is historically disadvantaged. If that’s the answer, you don’t have to scrap your idea entirely. Celebrate your awareness, and brainstorm about how you can do better for everyone—and then do it!

Embracing our Bruised Knees: Accepting Discomfort as We Grow

Inspirational author Brene Brown, who writes books, among other things, about being an ethical leader, said something that really walloped me: if we avoid the hard work of addressing unfairness (like talking about skin color at a time when our country is divided over it) we are prioritizing our discomfort over the pain of others.

Imagine a parent who doesn’t think it’s appropriate to talk about skin color with young children, who tells you so with some anger in their voice. That’s uncomfortable, maybe even a little scary. But as you prioritize upholding the dignity, worth, and uniqueness of every individual, you can see that this is more important than trying to avoid discomfort. Changing your practice to avoid conflict with this parent means prioritizing your own momentary discomfort over the pain children of color in your program may experience over time.

We might feel vulnerable when we think about skin color, and we don’t want to have to have the difficult conversation. But if keeping ourselves safe from discomfort means that we might not be keeping children safe from very real and life-impacting racial disparity, we’re not making a choice that is based in our values.

Change is uncomfortable. It leaves us feeling vulnerable as we reexamine the ideas, strategies, even the deeply held beliefs that have served us so far. But as a leader, and with the call to support every child as they deserve, we can develop a sort of super power vision, where we can look unflinchingly around us and understand the hidden impacts of the structures we work within.

A Few Recent Dance Steps of My Own

You’re definitely not alone—researchers and thinkers in the field are doing this work alongside you, examining even our most cherished and important ideas about childhood and early education. For instance, a key phrase that we often use to underpin our decisions is developmentally appropriate practice, which NAEYC defines as “methods that promote each child’s optimal development and learning through a strengths-based, play-based approach to joyful, engaged learning.” The phrase is sometimes used to contrast against practices that might not be developmentally appropriate, like expecting three-year-olds to write their names or sit quietly in a 30 minute story time.

Let me tell you a story about how professional development is still causing me to stare change in the face! At the NAEYC conference in 2020, during a session in which Dr. Jie-Qi Chen presented on different perspectives on developmentally appropriate practice among early educators in China and the United States. She showed a video from a classroom in China to educators in both the US and in China. The video was of a circle time in which a child was retelling a story that the class knew well, and then the children were encouraged to offer feedback and rate how well the child had done. The children listened attentively, and then told the storytelling child how they had felt about his retelling, including identifying parts that had been left out, inaccuracies in the telling, and advice for speaking more clearly and loudly.

The educators were asked what the impact of the activity would be on the children and whether it was developmentally appropriate. The educators in the United States had deep concerns that the activity would be damaging to a child’s self esteem, and was therefore not developmentally appropriate. They also expressed concerns about the children being asked to sit for this amount of time. The educators in the classroom in China felt that it was developmentally appropriate and the children were learning not only storytelling skills but how to give and receive constructive criticism.

As I watched the video, I had the same thoughts as the educators from the US—I’m not used to children being encouraged to offer criticism rather than praise. But I also saw that the child in question had self-confidence and received the feedback positively. The children were very engaged and seemed to feel their feedback mattered.

What was most interesting to me here was the idea of self-esteem, and how important it is to us here in the United States, or rather, how much protecting we feel it needs. I realized that what educators were responding to weren’t questions of whether retelling a story was developmentally appropriate, or whether the critical thinking skills the children were being asked to display were developmentally appropriate, but rather whether the social scenario in which one child receives potentially negative feedback in front of their peers was developmentally appropriate, and that the responses were based in the different cultural ideas of self-esteem and individual vision versus collective success.

My point here is that even our big ideas, like developmentally appropriate practice, have an element of vulnerability to them. As courageous leaders, we need to turn our eyes even there to make sure that our cultural assumptions and biases aren’t affecting our ability to see clearly, that the reality of every child is honored within them, and that no one is being left out. And that’s okay. It doesn’t mean we should scrap them. It’s not wrong to advocate for and use developmentally appropriate practice as a framework for our work—not at all! It just means we need to remember that it’s built from values that may be specific to our culture—and not everyone may have equal access to that culture. It means we should return to our big ideas with respect and bravery and sit with them and make sure they are still the ones that serve us best in the world we are living in right now, with the best knowledge we have right now.

You, Dancing With Courage

So…As a leader is early childhood, you will be called upon to be nimble, to make new decisions and reframe your practice when current events or new understanding disrupt your plans. When this happens, professional tools are available to you to help you make choices based on your ethical commitment to children.

Change makes us feel uncomfortable but we can embrace it to do the best by the children and families we work with. We can learn to develop our critical thinking skills so that we can examine our own beliefs and assumptions, both as individuals and as a leader.

Remember that person dancing on the shifting carpet? That child in the middle of the parachute? They might be a little dizzy, but with possibility. They might lose their footing, but in that uncertainty, in the middle of the billowing parachute, there is the sensation that the very instability provides the possibility of rising up like the fabric. And besides—there are hands to hold if they lose their balance—or if you do! And so can you rise when you allow yourself to accept change and adapt to all the new possibility of growth that it opens up!

Current Issues in the Field Part 2—Dance Lessons

Okay, sure—things are gonna change, and this change is going to affect the lives of the children and families you work with, and affect you, professionally and personally. So—you’re sold, in theory, that to do the best by each one of those children, you’re just going to have to do some fancy footwork, embrace the change, and think through how to best adapt to it.

But…how? Before we talk about the kind of change that’s about rethinking your program on a broad level, let’s talk about those times we face when change happens in the spur of the moment, and impacts the lives of the children in your program—those times when your job becomes helping children process their feelings and adapt to change. Sometimes this is a really big deal, like a natural disaster. Sometimes it’s something smaller like the personal story I share below…something small, cuddly, and very important to the children.

Learning the Steps: How do I help children respond to change?

I have a sad story to share. For many years, I was the lead teacher in a classroom in which we had a pet rabbit named Flopsy. Flopsy was litter-trained and so our licensing specialist allowed us to let him hop freely around the classroom. Flopsy was very social, and liked to interact with children. He liked to be held and petted and was also playful, suddenly zooming around the classroom, hopping over toys and nudging children. Flopsy was a big part of our community and of children’s experience in our classroom.

One day, I arrived at school to be told by my distraught director that Flopsy had died in the night and she had removed his body. I had about 15 minutes before children would be arriving, and I had to figure out how to address Flopsy’s loss.

I took a few minutes to collect myself, and considered the following questions:

Yes, absolutely. The children would notice immediately that Flopsy was missing and would comment on it. It was important that I not evade their questions.

Flopsy had died. His body had stopped working. His brain had stopped working. He would not ever come back to life. We would never see Flopsy again. I wrote these sentences on a sticky note. They were short but utterly important.

I would give children the opportunity to share their feelings, and talk about my own feelings. I would read children’s books that would express feelings they might not have words for yet. I would pay extra attention to children reaching out to me and offer opportunities to affirm children’s responses by writing them down.

Human beings encounter death. Children lose pets, grandparents, and sometimes parents or siblings. I wanted these children to experience death in a way that would give them a template when they experienced more intense loss. I wanted them to know it’s okay to be sad, and that the sadness grows less acute over time. That it’s okay to feel angry or scared, and that these feelings, too, though they might be really big, will become less immediate. And that it’s okay to feel happy as you remember the one you lost.

I knew it was important not to give children mistaken impressions about death. I was careful not to compare it to sleep, because I didn’t want them to think that maybe Flopsy would wake up again. I also didn’t want them to fear that when mama fell asleep it was the same thing as death. I also wanted to be factual but leave room for families to share their religious beliefs with their children.

I didn’t have time to do research. But I mentally gathered up some wisdom from a training I’d been to, where the trainer talked about how important it is that we don’t shy away from addressing death with children. Her words gave me courage. I also gathered up some children’s books about pet death from our library.

The first thing I did was text my husband. I was really sad. I had cared for this bunny for years and I loved him too. I didn’t have time for a phone call, but that text was an important way for me to acknowledge my own feelings of grief.

Then I talked to the other teachers. I asked for their quick advice, and shared my plan, since the news would travel to other classrooms as well.

During my prep time that day, I wrote a letter to families, letting them know Flopsy had died and some basic information about how we had spoken to children about it, some resources about talking to children about death, and some titles of books about the death of pets. I knew that news of Flopsy’s death would be carried home to many families, and that parents might want to share their own belief systems about death. I also knew many parents were uncomfortable discussing death with young children and that it might be helpful to see the way we had done so.

I had curriculum planned for that day which I partially scrapped. At our first gathering time I shared the news with the whole group: I shared my sticky note of information about death. I told the children I was sad. I asked if they had questions and I answered them honestly. I listened when they shared their own feelings. I also told them I had happy memories of FLopsy and we talked about our memories.

During the course of the day, and the next few days, I gave the children invitations (but not assignments) to reflect on Flopsy and their feelings. I sat on the floor with a notebook and the invitation for children to write a “story” about Flopsy. Almost every child wanted their words recorded. Responses ranged from “Goodbye bunny” to imagined stories about Flopsy’s adventures, to a description of feelings of sadness and loss. Writing down these words helped acknowledge the children’s feelings. Some of them hung their stories on the wall, and some asked them to be read aloud, or shared them themselves, at circle time.

I also made sure there were plenty of other opportunities in the classroom for children who didn’t want to engage in these ways, or who didn’t need to.

We read “Saying Goodbye to Lulu” and “The Tenth Good Thing About Barney” in small groups; and while these books were a little bit above the developmental level of some children in the class, many children wanted to hear and discuss the books. When I became teary reading them, I didn’t try to hide it, but just said “I’m feeling sad, and it makes me cry a little bit. Everyone cries sometimes.”

This would be a good set of steps to address an event like a hurricane, wildfires, or an earthquake as well. First and foremost of course, make sure your children are safe and have their physical needs met! Remember your role as educator and caretaker; address their emotional needs, consider what you hope they will learn, gather the resources and your team, and make decisions that affirm the dignity of each child in your care.

- Does the issue affect children’s lived experiences?

- How much and what kind of information is appropriate for their age?

- How can I best affirm their emotions?

- What do I hope they will learn?

- Could I accidentally be doing harm through my response?

- Which resources do I need and can I gather in a timely manner?

- How do I gather my team?

- How can I involve families?

- Now, I create and enact my plan…

Did your plan look any different for having used these questions? And did the process of making decisions as a leader look or feel different? How so?

You might not always walk yourself through a set of questions–but using an intentional tool is like counting out dance steps—there’s a lot of thinking it through at first, and maybe forgetting a step, and stumbling, and so forth. And then…somehow, you just know how to dance. And then you can learn to improvise. In other words, it is through practice that you will become adept at and confident in responding to change, and learn to move with grace on the shifting carpet of life.

Feeling the Rhythm: How do I help myself respond to change

—and grow through it.

Now, let’s address what it might look like to respond to a different kind of change, the kind in which you learn something new and realize you need to make some changes in who you are as an educator. This is hard, but there are steps you can take to make sure you keep moving forward:

- Work to understand your own feelings. Write about them. Talk them through with your teams—personal and/or professional.

- Take a look in the mirror, strive to see where you are at, and then be kind to yourself!

- Gather your tools! Get out that dog eared copy of the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, and look for other tools that are relevant to your situation. Root yourself in the values of early childhood care and education.

- Examine your own practices in light of this change.

- Examine the policies, structures, or systems that affect your program in light of this change.

- Ask yourself, where could change happen? Remember your spheres of influence.

- Who can you collaborate with? Who is on your team?

- How can you make sure the people being affected by this change help inform your response? Sometimes people use the phrase “Nothing for us without us” to help remember that we don’t want to make decisions that affect a group of people (even if we think we’re helping) without learning more from individuals in that group about what real support looks like).

- Make a plan, including a big vision and small steps, and start taking those small steps. Remember that when you are ready to bring others in, they will need to go through some of this process too, and you may need to be on their team as they look for a safe sounding board to explore their discomfort or fear.

- Realize that you are a courageous advocate for children. Give yourself a hug!

- Work to understand your own feelings. Write about them. Talk them through with your teams—personal and/or professional.

This might be a good time to freewrite about your feelings—just put your pencil to paper and start writing. Maybe you feel guilty because you’re afraid that too many children of color have been asked to leave your program. Maybe you feel angry about the injustice. Maybe you feel scared that this topic is politicized and people aren’t going to want to hear about it. Maybe you feel scared to even face the idea that bias could have affected children while in your care. All these feelings are okay! Maybe you talk to your partner or your friends about your fears before you’re ready to get started even thinking about taking action.

- Take a look in the mirror, strive to see where you are at, and then be kind to yourself! Tell that person looking back at you: “I did then what I knew how to do. Now that I know better, I do better.”

Yep. You love children and you did what you believed was best for the children in your program. Maybe now you can do even better by them! You are being really really brave by investigating!

- Gather your tools! Get out that dog-eared copy of the NAEYC Code of Ethical Conduct, and look for other tools that are relevant to your situation.

Okay! This would be an excellent time to bring out the equity lens and your other tools. Read them over. Use them.

Do your practices affirm the dignity of every child and family? Ask yourself these hard questions while focusing on, in this case, how you look at behavior of children of color. Do the choices you make affirm the dignity of each unique child? Use your tools—you can pull out the equity lens here! Are you acknowledging the home realities of each child when you are having conversations that are meant to build social-emotional skills? Are you considering the needs of each child during difficult transitions? Do you provide alternative ways for children to engage if they have difficulty sitting in circle times?

And…Do your policies and structures affirm the dignity of every child and family? Use those tools! Look at your behavioral guidance policies—are you expecting children to come into your program with certain skills that may not be valued by certain cultures? What about your policies on sending children home or asking a family to leave your program? Could these policies be unfair to certain groups? In fact—given that you now know how extremely impactful expulsion is for preschoolers, could you take it off the table entirely?

Let’s say you’re a teacher, and you can look back and see that over the years you’ve been at your center, a disproportionately high number of children of color have been excluded from the program. Your director makes policy decisions—can you bring this information to him or her? Could you talk to your coworkers about how to bring it up? Maybe your sphere of influence could get even wider—could you share this information with other early educators in your community? Maybe even write a letter to your local representatives!

- Who can you collaborate with? Who is on your team?

Maybe other educators? Maybe parents? Maybe your director? Maybe an old teacher of your own? Can you bring this up at a staff meeting? Or in informal conversations?

- How can you make sure the people being affected by this change help inform your response?

Let’s say your director is convinced that your policies need to change in light of this new information. You want to make sure that parent voice—and especially that of parents of color—is heard! You could suggest a parent meeting on the topic; or maybe do “listening sessions” with parents of color, where you ask them open-ended questions and listen and record their responses—without adding much of your own response; maybe you could invite parents to be part of a group who looks over and works on the policies. This can feel a little scary to people in charge (see decentered leadership?)

Maybe this plan is made along with your director and includes those parent meetings, and a timeline for having revised policies, and some training for the staff. Or—let’s back it up—maybe you’re not quite to that point yet, and your plan is how you are going to approach your director, especially since they might feel criticized. Then your plan might be sharing information, communicating enthusiasm about moving forward and making positive change, and clearly stating your thoughts on where change is needed! (Also some chocolate to reward yourself for being a courageous advocate for every child.)

And, as I may have mentioned, some chocolate. You are a leader and an advocate, and a person whose action mirrors their values. You are worth admiring!

Maybe you haven’t had your mind blown with new information lately, but I’ll bet there’s something you’ve thought about that you haven’t quite acted on yet…maybe it’s about individualizing lesson plans for children with differing abilities. Maybe it’s about addressing diversity of gender in the classroom. Maybe it’s about celebrating linguistic diversity, inviting children and parents to share their home languages in the classroom, and finding authentic ways to include print in these languages.

Whatever it is—we all have room to grow.

Make a Plan!

Dancing Your Dance: Rocking Leadership in Times of Change

There will never be a time when we as educators are not having to examine and respond to “Current Issues in the Field.” Working with children means working with children in a dynamic and ever-evolving landscape of community, knowledge, and personal experience. It’s really cool that we get to do this, walk beside small human beings as they learn to traverse the big wacky world with all its potholes…and it means we get to keep getting better and better at circling around, leaping over, and, yep, dancing around or even through those very potholes.

In conclusion, all dancers feel unsteady sometimes. All dancers bruise their knees along the way. All educators make mistakes and experience discomfort. All dancers wonder if this dance just isn’t for them. All dancers think that maybe this one is just too hard and want to quit sometimes. All educators second guess their career choices. But all dancers also discover their own innate grace and their inborn ability to both learn and to change; our very muscles are made to stretch, our cells replace themselves, and we quite simply cannot stand still. All educators have the capacity to grow into compassionate, courageous leaders!

Your heart, your brain, and your antsy feet have led you to become a professional in early childhood care and education, and they will all demand that you jump into the uncertainty of leadership in times of change, and learn to dance for the sake of the children in your care. This, truly, is your call to action, and your pressing invitation to join the dance!

Brown, B. (2018). Dare to lead . Vermilion.

Broughton, A., Castro, D. and Chen, J. (2020). Three International Perspectives on Culturally Embraced Pedagogical Approaches to Early Teaching and Learning. [Conference presentation]. NAEYC Annual Conference.

Crum, T. (1987). The Magic of Conflict: Turning a Life of Work into a Work of Art. Touchstone.

Meek, S. and Gilliam, W. (2016). Expulsion and Suspension in Early Education as Matters of Social Justice and Health Equity. Perspectives: Expert Voices in Health & Health Care.

Scott, K., Looby, A., Hipp, J. and Frost, N. (2017). “Applying an Equity Lens to the Child Care Setting.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 45 (S1), 77-81.

Online Resources for Current Issues in the Field

Resources for opening yourself to personal growth, change, and courageous leadership:

- Brown, Brenee. Daring Classrooms. https://brenebrown.com/daringclassrooms

- Chang, R. (March 25, 2019). What Growth Mindset Means for Kids [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66yaYmUNOx4

Resources for Thinking About Responding to Current Issues in Education

- Flanagan, N. (July 31, 2020). How School Should Respond to Covid-19 [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cSkUHHH4nb8

- Harris, N.B.. (February 217, 015). How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime [Video] . TED Conferences. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=95ovIJ3dsNk

- Simmons, D. (August 28, 2020). 6 Ways to be an Anti Racist Educator [Video] . Edutopia. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UM3Lfk751cg&t=3s

Leadership in Early Care and Education Copyright © 2022 by Dr. Tammy Marino; Dr. Maidie Rosengarden; Dr. Sally Gunyon; and Taya Noland is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- 15 December 2015

- Commentaries

Critical Issues in Early Childhood Development and Early Learning

Latest Posts

Getting ai right in education, food security issues in asia, transformational leadership, by dr. sheldon shaeffer.

The world seems to understand ever more clearly the importance of early childhood development in influencing the later success of children in school and more general well-bring later in life. First, the science of how young children develop, starting from conception to the age of three – which before was largely limited to issues of health and nutrition – has now begun to show the essential role in this development of cognitive and linguistic stimulation, stable and continuous care, and freedom from stress and conflict. With 80% of a child’s brain developing in the first three years of life, what parents and other caregivers do to promote the holistic development of their children during this period is critical to their future. Equally important, however, is a gradual and developmentally-appropriate process of mastering literacy and numeracy so that children, after the early years of school, are ready for later educational success rather than failure.

Second, research has also shown the cost-efficiency of investments in early childhood development, especially for children from the most marginalised social groups; relatively small investments at an early age yield large savings later in terms of not only future educational achievement and health status but also social welfare and criminal justice system costs.

Yet despite such evidence, many governments, especially ministries of education, continue to pay scant attention to young child development. The common position is that before children enter school, they are the concern of somebody else: ministries of health for very young children; ministries of social welfare or women’s affairs for children of daycare age; even, in many countries, the private sector or the community for the pre-school/kindergarten year(s) immediately before entry to primary school. This perception is changing, however, with more ministries taking responsibility for one-two years of pre-school education, but even then the human and financial resources provided to such education is usually much less than those provided to what is really considered the beginning of “formal” education – Grade 1.

But then the story becomes more complicated. Early childhood is now generally defined as covering the age range of 0-8 (and even starting at -9 months), therefore including the period of transition from the home to daycare centre and/or some other kind of pre-school and then to the early years of primary school when children are not only meant to gain the fundamentals of literacy and numeracy but also continue their socio-emotional development so important later in their work and in their life. But in most education systems of the world, relatively little attention is paid to the smoothness of this transition and ultimately to the quality of the early grades; thus:

- Primary school principals (and perhaps the community as a whole) pay more attention to the last grade in their school that to Grade 1, especially where to former ends in a high-stakes school-leaving examination.

- Pupil:teacher ratios are much higher in Grade 1 than in the upper grades when, in fact, the opposite should be true.

- Teachers in the early grades are often the least experienced, the least qualified, and the most contractually unstable – or sometimes the most senior teacher because older, more “matronly” teachers are considered more patient with a large class of young, active children. In both situations, however, these early grade teachers have seldom received any specialised training in the systematic teaching of literacy and numeracy – even more seldom training in the use of the children’s mother tongue which should be the language of first literacy.

And a final complication: most programmes in place that somehow “cover” children aged (say) 3-8 (e.g., daycare, kindergarten, primary school) have a set of desired child outcomes, recommended approaches to early care and later teaching, and more or less structured curriculum, syllabi, and lessons plans – the problem being that these seldom intersect.

To be continued….

Sheldon Shaeffer, the former Chief of Education in UNICEF and former Director of UNESCO’s Asia and Pacific Regional Bureau for Education, has a range of research interests including early childhood development, language use in education, inclusive education (broadly defined), and teacher development.

The HEAD Foundation Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views expressed by the authors are solely their own and do not reflect opinions of The HEAD Foundation .

Join our mailing list

Stay updated on all the latest news and events.

20 Upper Circular Road The Riverwalk, #02-21 Singapore 058416 +65 6672 6160 [email protected]

Let’s connect.

Do you have any questions about our projects or our site in general? Do you have any comments or ideas you would like to share with us?

Please feel free to call us, email us or simply send us a message from here.

Copyright © 2023 The HEAD Foundation. All Rights Reserved.

- Terms Of Use

- Privacy Policy

6 Challenges for Early Educators as Preschool Growth Halts

- Share article

School enrollment for the nation’s youngest learners nosedived during the pandemic—and has yet to fully recover.

Instability in early childhood education could cause long-term problems, not only for public school enrollment more generally, but for schools’ ability to recover academically from the years of pandemic disruption.

The number of students attending preschool and early childhood education had risen steadily in the decade before the pandemic. But according to U.S. Census data, during the pandemic, enrollment for 3- and 4-year-olds crashed to its lowest point in 25 years.

The National Institute for Early Education Research reports that only 17 percent of 3-year-olds and 41 percent of 4-year-olds participated in any early education in 2022. That figure includes all major public preschool programs—state-funded, early special education, and Head Start.

While a majority of states did increase enrollment in state-funded preschool 6 percent of 3-year-olds and 32 percent of 4-year-olds attended state-funded preschool in the 2021-22 school year in the 44 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam that provided public programs. That’s up 13 percent from 2020-21, but still 8 percent below pre-pandemic enrollment.

Policymakers at both the federal and state levels have been trying to reestablish momentum for early childhood education, with growing support from both states and the Biden administration for universal preschool for children ages 3 and up.

But staffing problems could hamstring efforts to boost early childhood enrollment. NIEER’s State of Preschool 2022 report found the majority of 62 state-funded preschool programs it studied in 44 states, the District of Columbia, and Guam in 2022 did not have enough qualified lead teachers.

“We found unprecedented teacher shortages as well as waivers to education and specialized training requirements resulting in fewer qualified teachers in preschool classrooms,” NIEER researchers concluded.

Although teacher shortages have risen across K-12, experts say preschool and early childhood programs face particular challenges.

Nearly half of all preschool teachers admitted to experiencing high levels of stress and burnout over the past few years, according to a nationwide poll of 2,500 teachers in 2022 by Teaching Strategies, an early childhood training group.

Research suggests early childhood educators need more support, via mentoring, training, and professional learning groups, to build their confidence in teaching and handle the psychological and emotional burdens of stress in early childhood classrooms, particularly with children who may arrive with fewer social and coping skills.

2. Mental health

Teaching was already a high-stress job before COVID-19, but since the start of the pandemic, depression among preschool teachers has risen. Research finds the COVID-19 pandemic has led to higher physical, emotional, and financial stress for early childhood educators.

Teachers with poor mental health are associated with more social-emotional and behavior challenges among students, creating a cycle of worsening class climate .

“Factors—particularly a secure attachment between child and caregiver and the emotional and mental well-being of the caregiver—[are] important components of beneficial care,” a National Research Council report finds.

3. Lack of resources

Per-pupil spending on early education has barely budged in the past two decades, after adjusting for inflation. States spent about $6,500 on average for each preschool student in 2022, according to the most recent U.S. Census data. That’s roughly the same per-pupil spending for early childhood education as 20 years ago, and less than half the $14,400 spent per public school student in K-12 overall, Census data show. Spending for preschool has increased about $400 per student since 2019-20, but NIEER found most of this increase comes from pandemic recovery funds, which are scheduled to expire.

4. Low compensation

The demand for early childhood educators is growing three times as fast as the average growth for all U.S. occupations, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, with 15 percent more teachers predicted for these grades through 2031.

But the BLS also finds early childhood educators earn an average annual wage of $30,210 in the United States—less than half that for all K-12 public teachers.

Seventeen of the 62 state-funded early childhood programs NIEER studied in its State of Preschool report have begun offering recruiting and retention incentive pay.

5. Professional development

Professional development can be a key way to retain early childhood teachers, but studies find they are less likely than teachers of higher grades to get that support.

Only five states—Alabama, Hawaii, Michigan, Mississippi, and Rhode Island—meet all 10 national benchmarks for program quality, including implementing standards for child development and providing teacher professional development, the NIEER report finds.

Of 62 state-funded preschool programs NIEER studied in 44 states and the District of Columbia, 50 require their lead teachers to have specialized training in early childhood education and only 18 provide individual professional development plans with at least 15 hours per year of training and coaching for teachers and assistants.

That’s a problem, because the Teaching Strategies survey found 7 out of 10 early childhood educators reported more job satisfaction when they had access to high-quality, ongoing training, and 65 percent of preschool educators who plan to leave teaching said they didn’t have access to such professional development.

6. Technology

Educators of early learning have had to keep up with ever-changing technologies from year to year and decide how to best integrate technology into the classroom.

A 2019 research analysis found early childhood teachers are more likely to believe technology can be damaging for young children and less likely to know how to integrate it effectively in the classroom.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Issues in Early Childhood Education in 2022

- December 20, 2022

Since the beginning of organized childcare, providers have faced a number of issues in early childhood education. Not to mention the onslaught of additional challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic.

At ChildCare Education Institute, we’ve spent the last 15+ years helping teachers navigate life in and out of the classroom. As a result, we’ve seen first-hand the problems facing early childhood education — and we’ve learned that the first step to addressing these problems is a better awareness of them.

That’s why we’re breaking down the most prominent issues in early childhood education and how you can best tackle them.

Workplace burnout.

One of the leading problems facing early childhood education is an escalating rate of teacher burnout. According to a 2022 poll, nearly half of all preschool teachers admitted to experiencing high levels of stress and burnout over the past few years.

While some of that stress is inherent to the job, most of the additional burnout has come from a severe staffing shortage affecting centers and programs across the country. Since early 2020, 8.4% of the childcare workforce has left for other professions — which is especially worrying considering many centers were experiencing staffing problems before the pandemic.

As a result, the teachers that stayed are dealing with longer hours, larger classrooms, and in some cases, new, mixed-age teaching environments.

For those educators lucky enough to find themselves at fully staffed centers, there are still a number of new stressors brought about by COVID-19, including new safety measures, check-in protocols, and more.

What can you do?: If you’re an educator experiencing workplace burnout, our course Stress Management for Child Care Providers is a great first step toward learning how to cope with your professional stress. We also recommend scheduling a regular time to reflect on the positives of each day and remember what drew you to early childhood education in the first place.

Mental health concerns.

Though mental health has always been one of the prominent issues in early childhood education, COVID-19 has truly brought it to the forefront. In Virginia alone, depression among preschool teachers has risen by 15% since the start of the pandemic. While this would be troubling for any profession, it’s especially hard for teachers as their mood can directly impact their student’s ability to learn and comprehend the material. Funding issues in early childhood education can also lead to a lack of resources for teachers who want to seek help.

What can you do?: If you’re experiencing any symptoms of declining mental health, the most important thing to do is seek help. We recommend starting with this list of 50 resources from Teach.com.

Lack of resources.

Funding issues in early childhood education are another hurdle many teachers face. According to a recent study conducted by The Century Fund, the United States is underfunding public schools by nearly $150 billion annually. As a result, many childcare providers have to dip into their own pockets to make up for the small classroom budgets they’re given — something that’s especially challenging given most teachers are already underpaid.

What can you do?: While there’s nothing you can do to solve funding issues in early childhood education overnight, there are a number of scholarship and grant programs available to help teachers with classroom and professional development expenses. For more information on the latter, click here.

Low levels of compensation.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, early childhood educators earn an average annual wage of $30,210 in the United States (with the lowest 10% making just $21,900 per year). When compared to the average public school teacher’s salary of $65,090, it’s no surprise that compensation is among the top problems facing early childhood education.

Because the average salary for the profession is so low, most educators are forced to take on a second job or rely on public income support programs to make ends meet. These can significantly add to a teacher’s burnout and can cause stress that spills over into their personal life.

What can you do?: If you’re looking to advocate for higher wages and other funding issues in early childhood education, there are a number of groups you can join, including NAEYC. You can also help set yourself apart — and potentially raise your earning potential — by earning a well-respected certification, such as your Child Development Associate (CDA) Credential.

Heightened safety concerns.

Another one of the top issues in early childhood education is safety. Since the start of 2022, there have been more than 300 mass shootings — equating to roughly four per week. While not all of these shootings have taken place at schools, enough have left teachers worried about their workplace safety.

In addition to worrying about their own safety while at work, early childhood educators also often have to worry about the safety of their students. Because children attending childcare programs can range anywhere from just a few months to six years of age, there are a number of physical and environmental dangers present at any given time. Therefore, teachers have to constantly be on guard, something that can lead to increased levels of stress and fatigue.

What can you do?: One of the best ways to address safety concerns in the workplace is to feel confident in your abilities to avoid and — in the worst case — deal with any issues that may arise. Some of our top-rated safety courses include:

- Emergency Preparedness and Response Planning for Natural and Man-Made Events

- Fire Safety in the Early Care and Education Environment

- Indoor Safety in the Early Childhood Setting

- Outdoor Safety in the Early Childhood Setting

Ever-evolving technologies.

When COVID-19 hit, schools across the country raced to adopt virtual learning environments that allowed their students to connect and engage without having to attend in-person sessions. While it proved to be an effective way to limit the spread of coronavirus, it didn’t come without its own share of challenges.

For some families, a lack of access to technology meant they were no longer able to receive the instruction they needed. For others, not being able to have one-on-one time with educators led to a decline in learning. Finally, despite the best attempts from schools and video conferencing providers, teachers and students still fell victim to technology issues, including lack of connectivity, dropped calls, and more.

As the pandemic waned and in-person learning resumed, many schools opted to keep hybrid learning as an option for their students. Despite the added convenience this affords some families, it has also greatly contributed to one of the top issues in early childhood education: technology.

As technology changes in the classroom, teachers must race to keep up with it.

The same goes for the technology students interact with.

Teachers today have to decide how to incorporate technology into their classrooms, what screen time limits to set for their students and how to navigate a digital landscape that’s different every year.

What can you do?: The best way to combat the ever-changing technology landscape in early childhood education is to make sure you’re staying up-to-date on industry recommendations and research. Our The Child’s Digital Universe: Technology and Digital Media in Early Childhood course is the perfect place to start.

Lack of parent engagement and communication.

As any teacher can attest to, trying to build an engaged and communicative parent base is another one of the prominent issues in early childhood education. Unlike other professions, teachers have to deal with the 20+ personalities in their classroom, as well as the 40+ personalities of those students’ guardians. Not to mention the frustration that can result from parents who are never present — or those who are overly present.

Plus, funding issues in early childhood education can often hamper parent-teacher communication. For example, some programs might not have the funds available to provide teachers with software that allows them to quickly send email blasts to all families. As a result, educators may find themselves having to send important updates via email one family at a time.

What can you do?: While parent-teacher communication will likely always be one of the problems facing early childhood education, there are things you can do as a teacher to lessen the effect it has on you and your classroom. One of those resources is our course Parent Communication: Building Partners in the Educational Process.

Want to learn more about the top issues in early childhood education and how to combat them? Our online courses can help!

Click here to explore our 150+ topics covering everything from child development to classroom management to addressing the problems facing early childhood education.

ChildCare Education Institute (CCEI) is the industry leader for online professional development .

Professional Development Courses

Certificate Programs

Staff Training

Head Start Training

Director Training

Custom Course Hosting

Trial Course

Trending Topics

Terms of Use | Privacy Policy | Site Map | Code of Conduct | Student Handbook English | Student Handbook Spanish © 2024 ChildCare Education Institute 1155 Perimeter Center West, Atlanta, GA 30338 Phone: 1.800.499.9907

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Critical issues in early childhood education

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

35 Previews

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station20.cebu on July 21, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- NAEYC Login

- Member Profile

- Hello Community

- Accreditation Portal

- Online Learning

- Online Store

Popular Searches: DAP ; Coping with COVID-19 ; E-books ; Anti-Bias Education ; Online Store

You are here

NAEYC provides the highest-quality resources on a broad range of important topics in early childhood. We’ve selected a few of our most popular topics and resources in the list below.

Still can’t find the topic you need? Check out our site search .

- Anti-Bias Education

- Back to School

- Common Core

- Coping with COVID-19

- Coping With Stress and Violence

- Developmentally Appropriate Practice (DAP)

- Dual Language Learners

- Family Engagement

- Guidance and Challenging Behaviors

- Recursos en Español

- Social and Emotional Development

- Summer Learning

- Technology and Media

- الموارد باللغة العربية

- منابع فارسی

Looking for a specific topic? Try using our search page! The new search allows you to filter by audience, age group of children, or topic.

Education Policy

Making the early grades matter, a conversation about teaching and learning in kindergarten through grade 2, article/op-ed.

Shutterstock

Laura bornfreund, feb. 26, 2024.

With the exception of reading, there has long been limited attention to strengthening kindergarten and the early grades of elementary school and K-2 teachers' vital role in laying the foundation for children’s future learning and development. The tide, however, may be shifting. Under U.S. Secretary of Education Cardona, the Department of Education has an initiative to help states think about how to make kindergarten a more “sturdy bridge” between pre-K and the early grades. In recent years, state legislatures have introduced or passed laws to require kindergarten, fund kindergarten as a full day, and promote play-based learning in kindergarten and the early grades. Other states are piloting efforts to ensure children’s kindergarten experiences align with how they learn best. To learn more about efforts to transform kindergarten, visit New America’s Transforming Kindergarten page . You can also check out some of our ideas for strengthening K-2 here .

Last year, in 2023, I had the opportunity to work with School Readiness Consulting on a landscape project of what assessment and curricula look like in kindergarten through second grade. For this blog post, I asked SRC team members Soumya Bhat, Mimi Howard, Kate McKenney, Eugenia McRae, and Nicole Sharpe, and authors of the brief “ Making the Early Years Matter ,” what they learned about the K-2 years.

In the brief, "Making the Early Grades Matter: Seven Ways to Improve Kindergarten Through Grade 2," you write about the importance and opportunity of children’s K-2 years. You say that their importance is not fully realized. How do we know this is the case, and why do you think it’s happening?

While such clear benefits are linked to the K–2 years, particularly the importance of kindergarten, the policies and practices in use for this critical time have yet to catch up to the research. We know that children who start behind will stay behind, underscoring that grade 3 is too late to start focusing on student proficiency. Unfortunately, K-2 continues to be systemically undervalued and under-resourced in many districts. This undervaluing is happening for several reasons – one is that school improvement efforts primarily focus on third grade and above, partly due to accountability pressures and accompanying testing requirements. This focus on standardized assessments later in elementary school has increased academic demands in the K-2 space. That pushdown of academic expectations is not aligned with developmentally appropriate teaching and learning practices, leading to challenges for K–2 teachers charged with providing that continuous and robust educational experience for their students.

Tell us what you learned from your research and interviews about leveraging and improving K-2 policy and practice. What do you think is most important?

We certainly need to make changes that immediately impact the system - like expanding the supply of high-quality materials available for use by the K-2 community. And at the same time, those actions should also be coupled with more ongoing and long-term solutions, such as increasing focus and awareness around the uniqueness and value of K-2 as part of the more extensive education system. There is a strong sense of urgency about the challenges facing K–2, but at the same time, it is challenging to shift K–2 policies and practices in sustainable ways unless there is first a fundamental, core mindset shift—that K–2 should be a priority. This will require changing people’s minds about why the early grades are important and motivating people to invest in how young children learn in K–2. Only after these more significant mindset shifts occur will the education field be able to generate solutions that will lead to long-term systems change.

The Making the Early Grades Matter brief resulted from several interviews with district officials, stakeholders, and educators about instruction, curriculum, and assessment in K-2. Was there a story or comment that sticks out to you?

There is a clear desire and need to shift leaders' thinking toward investing in high-quality K–2 education that is well-aligned to prepare children to succeed in the third grade. One of the interviewees we spoke to said it best, “It’s not just one fix. So, it’s not just professional learning, it's not just curriculum, it’s not just assessment. You have to figure out how that all works together as a system.” As a field, we should know what a comprehensive and aligned K-2 system looks like and what it takes to get there. We need to ensure that K-2 educators have sufficient time, training, and resources to implement these practices with fidelity and with the support of district leadership. When these elements are in place, young students will be able to experience high-quality learning and instruction throughout the K-2 grades.

While federal, state, and local policymakers have a role in transforming what happens in K-2nd grade, philanthropies can be key partners. What can local and national foundations do?

Our scan revealed that philanthropic work focused on early childhood—even when funders include K–2 as part of a prenatal-to-third-grade emphasis—is often geared toward the beginning part of this spectrum with greater support for birth-to-five efforts. Similarly, philanthropic work focused on K -12 may usually trend toward grade 3 and higher grades. So, local and national philanthropy is well positioned to help fill the gaps in K-2, not only through strategic investments that advance the field but also by enlisting new partners in the work and ultimately elevating the value of the early grades.

Is there anything I haven’t asked that you think is important to highlight?

We must also consider who will bear the brunt of failure if we don’t address these systemic K-2 issues. The impacts of inaction will be most significantly felt by Black and Latine children, children experiencing poverty, multilingual learners, and children with learning disabilities. Multiple factors contribute to these students' inadequate early elementary experiences, including a lack of culturally relevant materials, potential bias in assessment design or implementation, mismatched demographic characteristics with teachers, less effective kindergarten transition activities, and overemphasis on didactic academic instruction. Until the systemic issues are further examined and addressed, these barriers will continue to keep many K-2 learners from receiving the support they need and deserve and from being prepared for success in third grade and beyond.

For more information, read School Readiness Consulting’s brief “ Making the Early Grades Matter: Seven Ways to Improve Kindergarten through Grade 2 .”

Related Topics

Department of Education Victoria: We're making Victoria the Education State

The Department of Education offers learning and development support and services for all Victorians.

Website navigation

Our website uses a free tool to translate into other languages. This tool is a guide and may not be accurate. For more, see: Information in your language

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS