Academic Writing for Academic Persian: A Synthesis of Recent Research

- First Online: 18 September 2021

Cite this chapter

- Chiew Hong Ng 10 &

- Yin Ling Cheung 10

Part of the book series: Language Policy ((LAPO,volume 25))

234 Accesses

Besides enhancing Persian academic reading, in an English only research world, Persian academic stakeholders have to master English and/or Persian academic writing to disseminate findings globally to members of different disciplinary communities through Persian and English language as a lingua franca. This chapter uses the method of qualitative meta-synthesis of 40 empirical studies specifically on academic writing in Persian in refereed journals, book chapters, and conference proceedings published during the period of 2005–2020. An inductive approach to thematic analysis synthesizes (a) the theoretical models for researching Academic Persian in academic writing and (b) the similarities and differences between academic writers from Persian and English for different disciplines. Theoretically and pedagogically, the findings from the comparisons and the systematic content analysis following Sandelowski et al. (Res Nurs Health 20:365–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199708)20:4<365::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-E , 1997) contribute to our understanding of styles and genres specific to academic writing for Academic Persian, in terms of theoretical models for research as well as conventions or expectations of different disciplines in academic writing for Academic Persian.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Abdi, R. (2009). Projecting cultural identity through metadiscourse marking: A comparison of Persian and English research articles. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning Year, 52 (212), 1–15.

Google Scholar

Adel, S. M. R., & Moghadam, R. G. (2015). A comparison of moves in conclusion sections of research articles in psychology, Persian Literature and applied linguistics. Teaching English Language, 9 (2), 167–191. https://doi.org/10.22132/TEL.2015.53729

Article Google Scholar

Aghdassi, A. (2018). Persian academic reading . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Allami, A., & Naeimi, A. (2010). A cross-linguistic study of refusal: An analysis of pragmatic competence development in Iranian EFL learners. Journal of Pragmatics, 43 (1), 385–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2010.07.010

Ansarifar, A., Shahriari, H., & Pishghadam, R. (2018). Phrasal complexity in academic writing: A comparison of abstracts written by graduate students and expert writers in applied linguistics. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 31 , 58–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2017.12.008

Ansarin, A. A., & Tarlani-Aliabdi, H. (2011). Reader engagement in English and Persian applied linguistics articles. English Language Teaching, 4 (4), 154–164. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n4p154

Attarn, A. (2014). Study of metadiscourse in ESP articles: A comparison of English articles written by Iranian and English native speakers. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 5 (1), 63–71.

Belcher, D. D. (2007). Seeking acceptance in an English-only research world. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16 (1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2006.12.001

Bennet, K., & Muresan, L.-H. (2016). Rhetorical incompatibilities in academic writing: English versus the romance cultures. SYNERGY, 12 (1), 95–119.

Bhatia, V. K. (1997). Introduction: Genre analysis and world Englishes. World Englishes, 16 (3), 313–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-971X.00066

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Cortes, V. (2004). “Take a look at…”: Lexical bundles in university teaching and textbooks. Applied Linguistics, 25 , 401–435. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.v8i1.30051

Biber, D., Gray, B., & Poonpon, K. (2011). Should we use characteristics of conversation to measure grammatical complexity in L2 writing development? TESOL Quarterly, 45 (1), 5–35. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.244483

Coffin, C. (2009). Incorporating and evaluating voices in a film studies thesis. Writing and Pedagogy, 1 , 163–193. https://doi.org/10.1558/wap.v1i2.163

Ebadi, S., Salman, A. R., & Ebrahimi, B. (2015). A comparative study of the use of metadiscourse markers in Persian and English academic papers. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Research, 2 (4), 28–41.

Ershadi, S., & Farnia, M. (2015). Comparative generic analysis of discussions of English and Persian computer research articles. Culture and Communication Online, 6 (6), 15–31.

Esfandiari, R., & Barbary, F. (2017). A contrastive corpus-driven study of lexical bundles between English writers and Persian writers in psychology research articles. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 29 , 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1046/J.JEAP.2017.09.002

Faghih, E., & Rahimpour, S. (2009). Contrastive rhetoric of English and Persian written texts: Metadiscourse in applied linguistics research articles. Rice Working Papers in Linguistics, 1 , 92–107.

Farahani, M. V. (2017). Investigating the application and distribution of metadiscourse features in research articles in Applied linguistics between English native writers and Iranian writers: A comparative corpus-based inquiry. Journal of Advances in Linguistics, 8 (1), 1268–1285. https://doi.org/10.24297/jal.v8i1.6441

Farzannia, S., & Farnia, M. (2017). Genre-based analysis of English and Persian research article abstracts in mining engineering journals. Beyond Words, 5 (1), 1–13.

Francis, G., Huston, S., Manning, E., & Patterns, C. C. G. (1996). Collins COBUILD grammar patterns 1; verbs . Harper Collins.

Ghasempour, B., & Farnia, M. (2017). Contrastive move analysis: Persian and English research articles abstracts in law. The Journal of Teaching English for Specific and Academic Purposes, 5 (4), 739–753. https://doi.org/10.22190/JTESAP1704739G

Ghazanfari, F., & Abassi, B. (2012). Functions of hedging: The case of Academic Persian prose in one of Iranian universities. Studies in Literature and Language, 4 (1), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.3968/j.sll.1923156320120401.1400

Gholami, J., & Ilghami, R. (2016). Metadiscourse markers in biological research articles and journal impact factor: Non-native writers vs. native writers. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education, 44 (4), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20961

Gholami, M., Tajalli, G., & Shokrpour, N. (2014). Metadiscourse markers in English medical texts and their Persian translation based on Hyland’s model. European Journal of English Language and Literature Studies, 2 (2), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.20961

Gillet, A. (2020). Academic writing: Genres in academic writing . http://www.uefap.com/writing/genre/genrefram.htm

Hasrati, M., Gheitury, A., & Hooti, N. (2010). A genre analysis of Persian research article abstracts: Communicative moves and author identity. Iranian Journal of Applied Language Studies, 2 (2), 47–74. https://doi.org/10.22111/IJALS.2012.70

Hunston, S. (1993). Professional conflict: Disagreement in academic discourse. In M. Baker, G. Francis, & E. Tognini-Bonelli (Eds.), Text & technology: In honor of John Sinclair (pp. 115–133). John Benjamins.

Chapter Google Scholar

Hyland, K. (1996). Nurturing hedges in the ESP curriculum. System, 24 (4), 477–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0346-251X(96)00043-7

Hyland, K. (1999). Academic attribution: Citation and the construction of disciplinary knowledge. Applied Linguistics, 20 , 341–367. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/20.3.341

Hyland, K. (2000). Disciplinary discourse: Social interactions in academic writing . Longman.

Hyland, K. (2004). Disciplinary interactions: Metadiscourse in L2 postgraduate writing. Journal of Second Language Writing, 13 , 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2004.02.001

Hyland, K. (2005). Metadiscourse . Continuum.

Hyland, K. (2008). As can be seen: Lexical bundles and disciplinary variation. English for Specific Purposes, 27 (1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2007.06.001

Hyland, K., & Tse, P. (2004). Metadiscourse in academic writing: A reappraisal. Applied Linguistics, 25 (2), 156–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/25.2.156

Khajavy, G. H., Asadpour, S. F., & Yousef, A. (2012). A comparative analysis of interactive metadiscourse features in discussion section of research articles written in English and Persian. International Journal of Linguistics, 4 (2), 147–159. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijl.v4i2.1767

Keshavarz, M. H., & Kheirieh, Z. (2011). Metadiscourse elements in English research articles written by native English and non-native Iranian writers in applied linguistics and civil engineering. Journal of English Studies, 1 (3), 3–15.

Koutsantoni, D. (2005). Greek cultural characteristics and academic writing. Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 23 (1), 97–138. https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.2005.0007

Lores, R. (2004). On RA abstracts: From rhetorical structure to thematic organization. English for Specific Purposes, 23 , 280–302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2003.06.001

Marefat, H., & Mohammadzadeh, S. (2013). Genre analysis of literature research article abstracts: A cross-linguistic, cross-cultural study. Applied Research on English Language, 2 (2), 37–50.

Mauranen, A. (1993). Contrastive ESP rhetoric: metatext in Finnish-English economics texts. English for Specific Purposes, 12 (1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/0889-4906(93)90024-I

Mohammadi, M. J. (2013). Do Persian and English dissertation acknowledgments accommodate Hyland’s model: A cross-linguistic study. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences, 3 (5), 534–547.

Mozayan, M. R., Allami, H., & Fazilatfar, A. M. (2017). Metadiscourse features in medical research articles: Subdisciplinary and paradigmatic influences in English and Persian. RALs, 9 (1), 83–104.

Omidi, L., & Farnia, M. (2016). Comparative generic analysis of introductions of English and Persian physical education research articles. International Journal of Language and Applied Linguistics, 2 (2), 1–18.

O’Sullivan, Í. (2010). Using corpora to enhance learners’ academic writing skills in French. Revue française de linguistique appliquée, XV , 21–35.

Peacock, M. (2011). The structure of the methods section in research articles across eight disciplines. Asian ESP Journal, 7 (2), 97–124.

Pho Phuong, D. (2010). Linguistic realizations of rhetorical structure: A corpus-based study of research article abstracts and introductions in applied linguistics and educational technology. Language and Computers, 71 , 135–152. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789042028012010

Pooresfahani, A. F., Khajavy, G. H., & Vahidnia, F. (2012). A contrastive study of metadiscourse elements in research articles written by Iranian applied linguistics and engineering writers in English. English Linguistics Research, 1 (1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.5430/elr.v1n1p88

Rahimi, S., & Farnia, M. (2017). Comparative generic analysis of introductions of English and Persian dentistry research articles. Iranian Journal of Research in English Language Teaching (RELP), 5 (1), 27–40.

Reza, P., & Atena, A. (2012). Rhetorical patterns of argumentation in EFL journals of Persian and English. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning , 1–10. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.132

Reza, G., & Mansoori, S. (2011). Metadiscursive distinction between Persian and English: An analysis of computer engineering research articles. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 2 (5), 1037–1042. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.2.5.1037-1042

Sadeghi, K., & Alinasab, M. (2020). Academic conflict in applied linguistics research article discussions: The case of native and non-native writers. English for Specific Purposes, 59 , 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2020.03.001

Samaie, M., Khosravian, F., & Boghayeri, M. (2014). The frequency and types of hedges in research article introductions by Persian and English native authors. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98 , 1678–1685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.593

Sandelowski, M., Docherty, S., & Emden, C. (1997). Qualitative metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Research in Nursing and Health, 20 , 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199708)20:4<365::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-E

Shokouhi, H., & Baghsiahi, A. T. (2009). Metadiscourse functions in English and Persian sociology articles: A study in contrastive rhetoric. Poznan Studies in Contemporary Linguistics, 45 (4), 549–568. https://doi.org/10.2478/v10010-009-0026-2

Shooshtari, Z. G., Alilifar, A., & Shahri, S. (2017). Ethnolinguistic influence on citation in English and Persian hard and soft science research articles. The Southeast Asian Journal of English Language Studies, 23 (2), 58–74. https://doi.org/10.17576/3L-2017-2302-05

Siami, T., & Abdi, R. (2012). Metadiscourse strategies in Persian research articles: Implications for teaching writing English articles. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning, 9 , 165–176.

Sorahi, M., & Shabani, M. (2016). Metadiscourse in Persian and English research article introductions. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 6 (6), 1175–1182. https://doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0606.06

Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings . Cambridge University Press.

Swales, J. M. (2004). Research genres: Explorations and applications . Cambridge University Press.

Taki, S., & Jafarpour, F. (2012). Engagement and stance in academic writing: A study of English and Persian research articles. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 3 (1), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2012.03.01.157

Toulmin, S. (2003). The uses of argument (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Valero-Garces, C. (1996). Contrastive ESP rhetoric: Metatext in Spanish-English economics texts. English for Specific Purposes, 15 (2), 279–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(96)00013-0

Vande Kopple, W. J. (1985). Some exploratory discourse on metadiscourse. College Composition and Communication, 36 (1), 82–93.

Varastehnezhad, M., & Gorjian, B. (2018). A comparative study on the uses of metadiscourse markers (MMs) in research articles (RAs): Applied linguistics versus politics. Journal of Applied Linguistics and Language Learning, 4 (2), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.5923/j.jalll.20180402.02

Yang, R., & Allison, D. (2003). Research articles in applied linguistics: Moving from results to conclusions. English for Specific Purposes, 22 , 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(02)00026-1

Yazdanmehr, E., & Samar, R. G. (2013). Comparing interpersonal metadiscourse in English and Persian abstracts of Iranian applied linguistics journals. The Experiment, 16 (1), 1090–1101.

Yeganeh, M. T., & Boghayeri, M. (2015). The frequency and function of reporting verbs in research articles written by native Persian and English speakers. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 192 , 582–586.

Yeganeh, M. T., & Ghoreyshi, S. M. (2014). Exploring gender differences in the use of discourse markers in Iranian academic research articles. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 192 , 684–689.

Zamani, G., & Ebadi, S. (2016). Move analysis of the conclusion sections of research papers in Persian and English. Cypriot Journal of Educational Science, 11 (1), 9–20.

Zand-Vakili, E., & Kashani, A. F. (2012). The contrastive move analysis: An investigation of Persian and English research articles’ abstract and introduction parts. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 3 (2), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.5901/mjss.2012.v3n2.129

Zarei, G. R., & Mansoori, S. (2007). Metadiscourse in academic prose: A contrastive analysis of English and Persian research articles. The Asian ESP Journal, 3 (2), 24–40.

Zarei, G. Z., & Mansoori, S. (2010). Are English and Persian distinct in their discursive elements: An analysis of applied linguistics texts. English for Specific Purposes World, 31 (10), 1–8.

Zarei, G. R., & Mansoori, S. (2011). A contrastive study on metadiscourse elements used in humanities vs. non humanities across Persian and English. English Language Teaching, 4 (1), 42–50. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v4n1p42

Zhang, W. Y., & Cheung, Y. L. (2017). Understanding engagement resources in constructing voice in research articles in the fields of computer networks and communications and second language writing. The Asian ESP Journal, 13 (3), 72–99.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Chiew Hong Ng & Yin Ling Cheung

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Chiew Hong Ng .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Ferdowsi University of Mashhad, Mashhad, Iran

Abbas Aghdassi

Appendix: List of selected studies

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ng, C.H., Cheung, Y.L. (2021). Academic Writing for Academic Persian: A Synthesis of Recent Research. In: Aghdassi, A. (eds) Perspectives on Academic Persian. Language Policy, vol 25. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75610-9_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75610-9_10

Published : 18 September 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75609-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75610-9

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Hayyim Steingass FarsiDictionary Glosbe Tatoeba

Google Bing

Langenscheidt

Wiktionary pronunciation

Wikipedia Google search Google books

• Dehkhoda Lexicon Institute : لغتنامهٔ دهخدا ( Loghat Nāmeh Dehkhodā , Dekhoda Dictionary) Persian dictionary in 15 volumes, by Ali-Akbar Dehkhoda علیاکبر دهخدا

• Aryanpour : Persian-English dictionary & French, German, Italian, Spanish, Swedish, Arabic

• FarsiDic : Persian Dictionary & Persian-English, Arabic, German, Italian

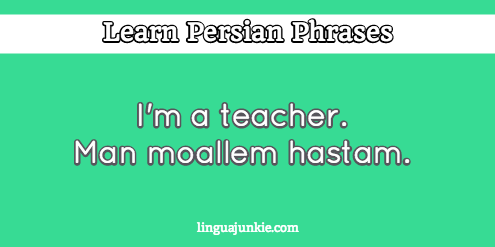

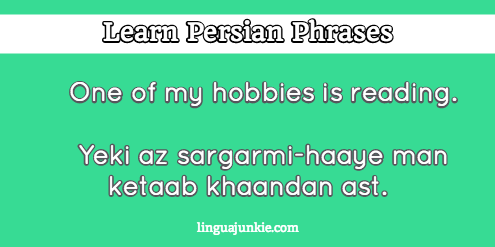

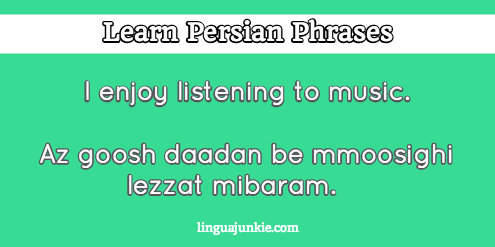

• translation of phrases Persian-English

• FarsiDicts : Persian-English dictionary

• Langenscheidt : Persian-German dictionary

• Free-dict : Persian-German dictionary

• Persian academy : Persian dictionary, words approved by the Persian language and literature Academy فرهنگستان زبان و ادب فارسی

→ online translation : Persian-English & other languages & web page

• Etymological dictionary of Persian , English & other Indo-European languages , by Ali Nourai

• An etymological dictionary of astronomy and astrophysics English-French-Persian, by Mohammad Heydari-Malayeri, Observatoire de Paris

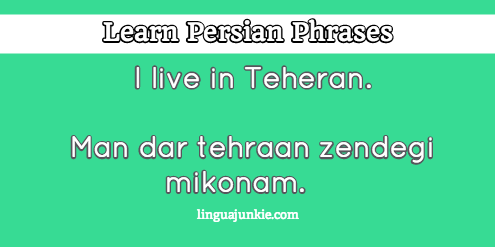

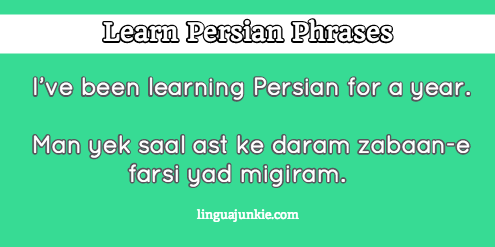

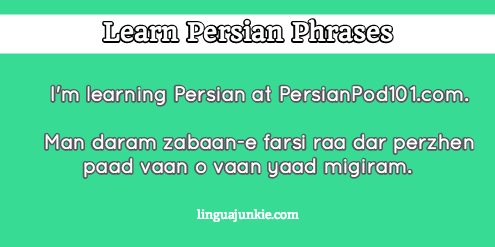

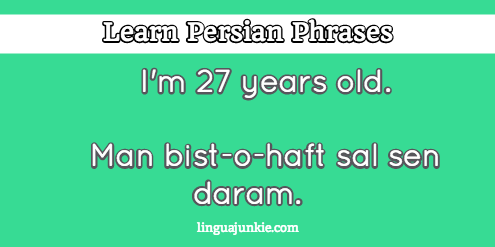

• Loecsen : Persian-English common phrases (+ audio)

• Goethe-Verlag : Persian-English common phrases & illustrated vocabulary (+ audio)

• LingoHut : Persian-English vocabulary by topics (+ audio)

• Defense language institute : basic vocabulary (+ audio) - civil affairs - medical

• Persian-English dictionary by Sulayman Hayyim (1934)

• Comprehensive Persian-English dictionary by Francis Steingass (1892)

• Colloquial English-Persian dictionary in the Roman character , by Douglas Craven Phillott (1914)

• Persian for travellers by Alexander Finn (1884) (Arabic & Latin characters)

• English and Persian dictionary by Sorabshaw Byramji (1882)

• Concise dictionary of the Persian language by Edward Henry Palmer (1891) (Arabic & Latin characters)

• Dictionary, Persian, Arabic, and English by Francis Johnson (1852)

• Pocket Dictionary of English and Persian by William Thornhill Tucker (1850) (Arabic & Latin characters)

• Dictionary in Persian and English by Ramdhun Sen (1841) (Arabic & Latin characters)

• Vocabulary of the Persian language by Samuel Rousseau (1805)

• Grundriss der neupersischen Etymologie : elements of Persian etymology, by Paul Horn (1893)

• Persische Studien : etymological studies, by Heinrich Hübschmann (1895)

• L'influence de la langue française sur le vocabulaire politique persan by Mahnaz Rezaï (2010)

• Les emprunts lexicaux du persan au français : inventaires et analyses , by Maryam Khalilpour, dissertation (2013)

→ Persian keyboard to type a text with the Arabic script

• Iran Heritage : Persian course (+ audio)

• EasyPersian : Persian course

• Persian alphabet

• University of Texas, Austin : Persian grammar (+ audio)

• Jahanshiri : Persian basic grammar & vocabulary

• verbs conjugation

• Dastur : Persian grammar, by Navid Fazel (in English, German, Persian)

• Anamnese : Persian grammar [PDF] (in French)

• Wikimedia : linguistic map, Persian language is spoken in Iran and in a part of Afghanistan

• The Persian system of politeness and concept of face in Iranian culture by Sofia Koutlaki (2014)

• Note sur le progressif en persan : Persian/English comparative study, by Monir Yazdi, in Cahiers de linguistique hispanique médiévale (1988)

• Higher Persian grammar by Douglas Craven Phillott (1919)

• Persian self-taught in Roman characters with English phonetic pronunciation , by Shayk Hasan (1909)

• Modern Persian conversation-grammar by William St. Clair Tisdall (1902)

• Modern Persian colloquial grammar & dialogues, vocabulary, by Fritz Rosen (1898)

• The Persian manual , grammar & vocabulary, by Henry Wilberforce Clarke (1878)

• Concise grammar of the Persian language , & Dialogues, reading lessons, vocabulary, by Arthur Henry Bleeck (1857)

• Grammar of the Persian language by Duncan Forbes (1844)

• Grammar of the Persian language by Mohammed Ibrahim (1841)

• Grammar of the Persian language by William Jones & additions by Samuel Lee (1828)

• Manuale della lingua persiana , grammatica, antologia, vocabolario , by Italo Pizzi (1883)

• Some remarks on Italo Pizzi's Manuale della lingua persiana by Riccardo Zipoli (2013)

• Principia grammatices neo-persicæ : Persian grammar, by Gabriel Geitlin (1845)

• Early new Persian langage : the Persian language after the Islamic conquest (8 th -12 th centuries) by Ludwig Paul, in Encyclopædia Iranica

• books & papers about the Persian language: Google books | Internet archive | Academia | Wikipedia

• Ham-mihan هممیهن - Mardom salari مردم سالاری

• Radio Zamaneh رادیو زمانه

• Radio Farda رادیو فردا

• BBC - RFI - DW

• LyrikLine : Persian poems, with translation (+ audio)

• Petite anthologie bilingue de littérature irano-persane (Medieval texts, with transcription & translation) by Denis Matringe (2021)

• Persian literature , an introduction , by Reuben Levy (1923)

• Persian literature by Claude Field (1912)

• Persian literature , ancient and modern , by Elizabeth Reed (1893)

• La Perse littéraire by Georges Frilley (1900)

• Les origines de la poésie persane by James Darmesteter (1887)

• Yek ruz dar Rostamabad-e Shemiran يک روز در رستم آبادِ شميران by Mohammad-Ali Jamalzade محمدعلی جمالزاده

• The Little Prince شازده کوچولو by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, translated into Persian by Ahmad Shamlou

• Primer of Persian , containing selections for reading and composition with the elements of syntax , by George Ranking (1907)

• The flowers of Persian literature , Extracts from the most celebrated authors in prose and verse, with a translation into English , by Samuel Rousseau, William Jones (1805)

• Chrestomathia Persica : Persian texts, by Friedrich Spiegel (1846)

• glossary Persian-Latin

• The Quran translated into Persian

• Farsinet : translation of the Bible into Persian

• The New Testament translated into Persian (1901)

• The Bible translated into Persian (1920)

• Universal Declaration of Human Rights اعلامیه جهانی حقوق بشر translation into Persian (+ audio)

→ First article in different languages

→ Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Persian, English & other languages

→ Iran : maps, heritage & documents

→ Old Persian language

→ Arabic language

Translation of "essay" into Persian

مقاله, انشا, جستار are the top translations of "essay" into Persian. Sample translated sentence: It's that little girl from Springfield who wrote the essay. ↔ همون دختر کوچولوئه از اسپرینگفیلد هست که اون مقاله رو نوشته.

A written composition of moderate length exploring a particular issue or subject. [..]

English-Persian dictionary

It's that little girl from Springfield who wrote the essay .

همون دختر کوچولوئه از اسپرینگفیلد هست که اون مقاله رو نوشته.

piece of writing often written from an author's personal point of view

We had to write an essay about our hero at school

یه بار که توی مدرسه باید دربارهی یه قهرمان انشا مینوشتیم

Less frequent translations

- (طرح پیشنهادی برای تمبر یا اسکناس جدید) الگو

- (ماهیت یا مرغوبیت و غیره) آزمودن

- اقدام کردن به

- امتحان کردن

- امتحاناانجام دادن

- انشا (نوشته ی کوتاه که بیانگر اندیشه و سلیقه ی نویسنده است)

- عیارگیری کردن

- مقاله نویسی

- پردازش (به کاری)

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " essay " into Persian

Translations with alternative spelling

"Essay" in English - Persian dictionary

Currently we have no translations for Essay in the dictionary, maybe you can add one? Make sure to check automatic translation, translation memory or indirect translations.

Phrases similar to "essay" with translations into Persian

- free form essay توصیف انشایی از خصوصیت ارزیابی شونده، روش تشریحی

Translations of "essay" into Persian in sentences, translation memory

The Fundamentals of Reading and Writing in Persian (Farsi)- It's Easier Than You Think!

To celebrate the launch of our long long awaited Persian (Farsi) Reading and Writing Course here at Learn Persian with Chai and Conversation, we thought it would be nice to provide a little introduction to the fundamentals of reading and writing in the Persian language. In this article, we hope to

- Introduce you to the Persian alphabet

- Provide an overview of the letters of the alphabet

- Show the differences between the Persian and English Alphabet

But first,-

Why learn how to read and write in the Persian language?

In Chai and Conversation, we’ve always emphasized conversational Persian, and aim to get students verbally communicating effectively as quickly as possible. Learning a whole new alphabet and new system for reading may seem intimidating for people learning a new language, and for this reason, all of our Conversational Persian lessons feature the words we’re learning in phonetic English spelling. This eliminates one of the largest hurdles many people have to diving into the Persian language in the first place.

However, in truth, you will not be able to understand a language fully until you can read and write it in its original form. If you want to truly understand the Persian language, it’s important to be able to read and write as well. Although it may seem difficult at first, once you understand a few basic principles, it’s quite easy to get the hang of it.

An Overview of the Persian Alphabet

The Persian alphabet consists of 32 letters . Although it is based on the Arabic alphabet, there are four letters in the Persian alphabet that do not appear in Arabic- these are پ , چ , ز , and گ ( pé , ché , zé and gé ).

There are several letters in the Persian alphabet that look different but make the same sound . For example, there are four letters that represent the sound ‘z’- ذ، ز، ض and ظ . Although they all look different, they all sound the same. Knowing which letter to use is a matter of memorization. This is actually a holdover from converting the alphabet from Arabic to Persian- in Arabic, the different versions DO make different sounds, but not when reading and writing in Persian. The sound 's' and 't' also have several different versions that look the same, but sound different. You can see them all in the alphabet reference guide below.

Most letters of the Persian alphabet have two different versions - what we call a bozorg (big) version and a koocheek (small) version , similar to capital versus lowercase versions in the English language. Depending on where the letter occurs in the word, they take on different versions. It's fairly intuitive to know which version to use based on placement in a given word- this simply comes with practice, and isn't something you need to worry about in the beginning of learning to read and write.

Also, many letters in the Persian alphabet are distinguished by the number and the positions of dots they have. So, many letters have the same base structure, but depending on the placement and number of dots, they are completely different sounds. For example- ت، ب and ث have similar 'bases,' and what differentiates them is the placement and numbers of dots they have.

Another slightly more complicated aspect of Persian writing is that many of the vowels are in the form of an 'accent' - and although they are provided when you're first learning to read and write, eventually, they are presumed to be understood and are not written at all. So for example, the word bad in Persian is written like this: بَد . The accent above the first letter is actually the vowel sound a. In most written Persian, the word will simply appear as بد as the writer will assume that you know based on the context of the word which accent it would have. Again, this sounds very complicated, but becomes intuitive fairly easily once you begin practicing reading and writing.

Alphabet Reference Guide

A note on the names of the letters in the Persian alphabet: Each letter of the alphabet has a formal name, and a sound that it makes. This is the same as in English- the letter ‘W’ for instance has a formal name (double you) and a sound (wa). Please see the end of the article for our pronunciation guide.

Differences Between the English and Persian Alphabets

One of the biggest differences between Persian and English is that Persian is written from right to left . So not only are words and sentences written from right to left, but books also open in the opposite direction from English books.

Another difference between Persian and English is that Persian letters are connected whether in print or in handwriting. For instance, in English, letters are connected only when writing in cursive. In Persian, however, they are always connected, even in print writing.

Persian writing is also more phonetic than English writing. For instance- in the word Pacific Ocean, the letter 'c' sounds different in every single instance of its use. Persian writing is not like this. When you see the letter س it always sounds like 's', no matter what.

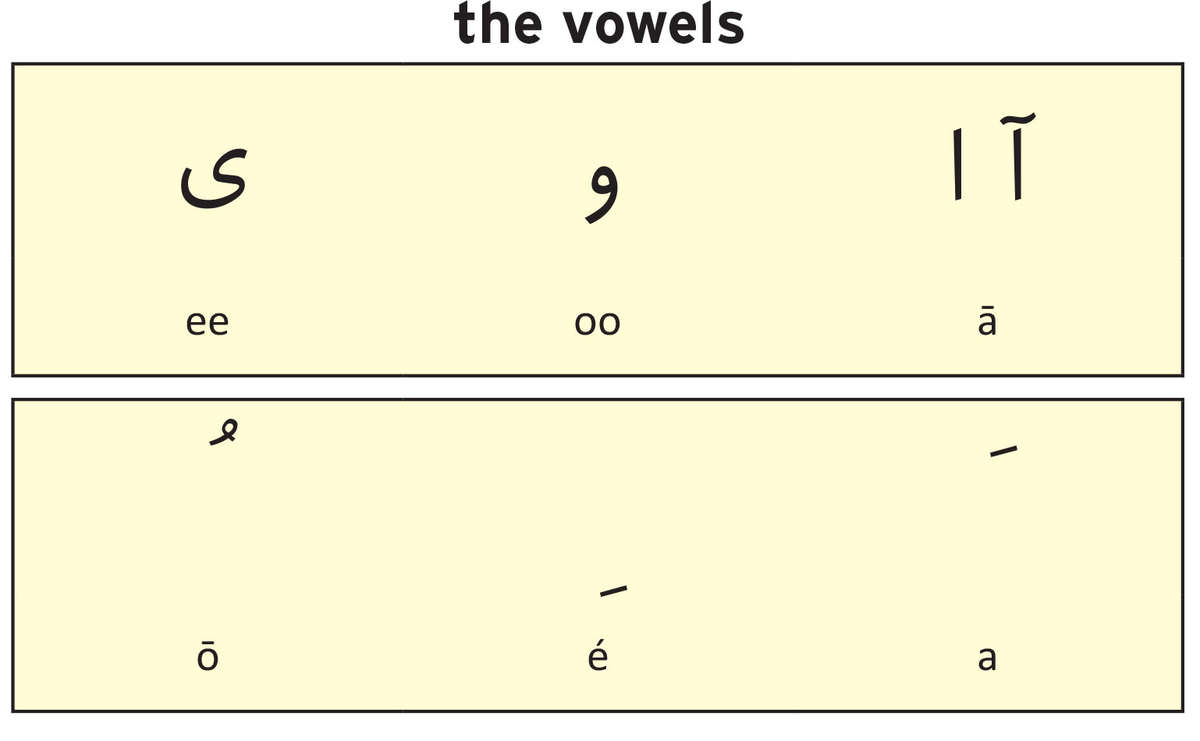

Vowels in Persian Writing

The Persian language has 6 vowel sounds total . This is in contrast to English which, although there are only 5 letters representing vowels, there are a total of 15 vowel sounds, created by combining those vowels in different ways.

There are only three letters of the Persian alphabet that are purely vowels. These are و، آ and ی ( ā , oo , and ee ). The other three vowel sounds are in the form of accents. They are َ، ِ، and ُ. As said above these accents are provided in the beginning when you are learning to read and write, but later, they are assumed to be understood. So you must make an educated guess about which vowel a word has based on its context.

Ready to Learn More About Reading and Writing in Persian?

Not to worry- our highly anticipated Reading and Writing in Persian (Farsi) series is now available! The series features easy to understand videos, as well as comprehensive PDF Guides that will have you reading and writing in no time. If you're not a member of Chai and Conversation already, you can sign up for a free 30 day trial of the program, and begin learning!

PRONUNCIATION GUIDE:

a short a like in hat ā long a like in autumn é ending ‘e’ like in elf ō ending o sharp o. listen to podcast for exact sound

Related Posts

Lesson 1: How to Greet People and Ask How They're Doing

11 Persian Sayings That Make No Sense in English

Azizam and Joonam- What do they Mean?

How this works.

- Our Learning System

- Speak Persian

- Read/Write Persian

- Persian Poetry

Join the Conversation.

Sign up, and you’ll receive weekly emails that will motivate, inspire, and encourage you on your Persian language learning journey.

- ECD6213C-7271-49BD-A14A-0C30F2587162

- C0456269-033A-4B14-BD1B-687A71625A95

- DA1343C7-7F80-409A-848A-6EB3FF04661B

- 270A108A-2127-4AEB-8EED-EC4F1F38AB91

Voice speed

Text translation, source text, translation results, document translation, drag and drop.

Website translation

Enter a URL

Image translation

How to Learn Farsi as a Complete Beginner: Alphabet, Grammar, Resources & Tips

Are you curious about understanding how to learn Farsi? This guide will offer you the main key points and resources to start your learning process . Studying Farsi can open up a world of opportunities, both personally and professionally. In this article, we'll show you how to learn Farsi step by step and demystify that it's a difficult language to master.

When you learn Farsi, you're not only gaining a valuable skill but also tapping into a vibrant culture. It can boost your career prospects, increase your cognitive abilities, and open doors to new friendships. Learning Farsi can be a rewarding experience that enriches your life in countless ways.

Farsi is not confined to its homeland; its influence extends globally. It's one of the most widely spoken languages in the Middle East and Central Asia . Moreover, Iran's growing presence in various fields, including politics, economics, and culture, makes Farsi an increasingly important language on the world stage. Learning Farsi can provide you with unique insights into this influential and diverse region. Let’s start!

Getting Started with Farsi Language

The Farsi Alphabet

Farsi alphabet, also known as the Persian script, is a beautiful and distinctive writing system that consists of 32 letters. Each letter has its unique form and pronunciation. Farsi is written from right to left , making it a right-to-left script. While it may appear challenging to those unfamiliar with it, the Farsi alphabet has an elegant simplicity that becomes more accessible with practice. Mastery of the alphabet is fundamental to unlocking the rich world of the Farsi language, and with dedication, you can swiftly become adept at reading and writing in this script. Here's the Farsi alphabet along with pronunciation:

The most effective method to learn the Farsi alphabet is through consistent practice and the use of mnemonic devices. Begin by familiarizing yourself with the individual letters and their corresponding sounds. Flashcards or mobile apps dedicated to Farsi alphabet learning can be invaluable tools. Create associations or visual aids to remember each letter more easily. Practice writing the letters by hand to reinforce your muscle memory . As you progress, try reading simple Farsi texts or labeling everyday objects in your environment with their Farsi names to apply your newfound knowledge.

Basic Farsi Grammar

Farsi grammar may appear complex, but let's simplify with three essential grammatical rules to keep in mind. Firstly, word order in Farsi typically follows a Subject-Object-Verb (SOV) structure , where the subject comes first, followed by the object, and finally the verb. Secondly, Farsi nouns have gender (masculine or feminine) , and it's crucial to learn the gender of nouns along with their corresponding definite articles ('-e' for masculine and '-ye' for feminine ) to form proper noun phrases. Lastly, Farsi verbs are conjugated differently based on tense, mood, and subject. Understanding the conjugation patterns, especially for present and past tenses, is vital for constructing accurate sentences. Regular practice and exposure to these fundamental rules will help beginners build a solid foundation in Farsi grammar.

To avoid common grammatical errors, remember these tips:

- Learn Grammar in Context: Instead of just memorizing rules in isolation, try to learn grammar within the context of real sentences and conversations. This will help you understand how grammar is used naturally and make it easier to apply in your own speech and writing.

- Keep a Grammar Journal: Create a journal dedicated to tracking your grammar progress. Whenever you encounter a new grammar rule or make a mistake, write it down along with examples. Review your journal regularly to reinforce what you've learned and track your improvement over time.

- Practice with Farsi Media: Watch Farsi-language movies, TV shows, or read books and articles in Farsi. This exposure to authentic language use will help you internalize grammar rules and see how they are applied in real-life situations.

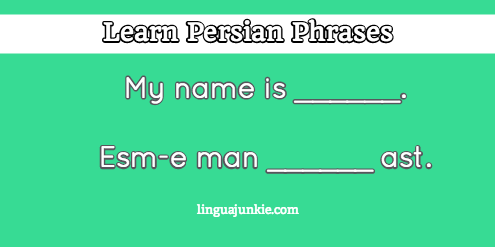

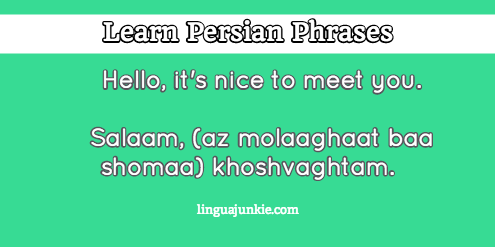

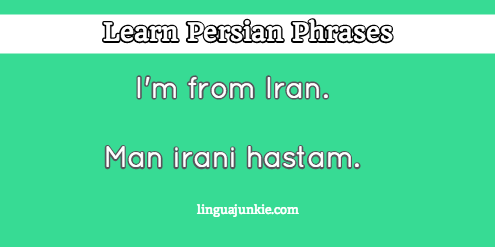

Farsi Common Phrases

Here are 20 common Farsi phrases to kickstart your conversations:

- Salam (سلام) - Hello

- Khodahafez (خداحافظ) - Goodbye

- Mamnoon (ممنون) - Thank you

- Lotfan (لطفاً) - Please

- Na (نه) - No

- Bale (بله) - Yes

- Chetor hasti? (چطور هستی؟) - How are you?

- Khaili khobi (خیلی خوبی) - I'm fine

- Be khodet komak kon (به خودت کمک کن) - Help yourself

- Man Farsi balad nistam (من فارسی بلد نیستم) - I don't speak Farsi

- Ba'alejeh (بعله) - Excuse me

- Cheghadr mishe? (چقدر میشه؟) - How much does it cost?

- Bekhod khodet (بخود خودت) - Do it yourself

- Khoda negahdar (خدا نگهدار) - God bless you

- Chetori? (چطوری؟) - How's it going?

- Bebinamet (ببینمت) - See you

- Man angrez hastam (من انگلیسی هستم) - I'm English

- Man dooset daram (من دوست دارم) - I love you

- Dorood (درود) - Greetings

- Kheili mamnoonam (خیلی ممنونم) - Thank you very much

A valuable exercise to enhance pronunciation of basic Farsi phrases involves the use of a native speaker's audio recordings or language learning apps with pronunciation features.

Select a set of common Farsi phrases and play the audio. Listen carefully to the native speaker's pronunciation and try to mimic their intonation, rhythm, and stress patterns. Pause and repeat each phrase multiple times, focusing on accurately reproducing the sounds. Pay attention to the nuances of Farsi sounds, such as the guttural "kh" sound and the various vowel sounds.

Recording yourself while practicing can also be helpful for self-assessment and improvement.

Tips and Tricks on Learning Farsi

Studying Farsi at home can be both effective and enjoyable with these three tricks. First, establish a consistent routine by dedicating a specific time each day for language practice. Consistency is key to making steady progress. Second, create an immersive environment by changing your phone or computer settings to Farsi , labeling objects around your home with their Farsi names, and consuming Farsi media such as movies, music, and news. This helps reinforce vocabulary and cultural understanding. Lastly, connect with online language communities or find a language exchange partner who speaks Farsi. Engaging in conversations, even virtually, provides practical experience and encourages regular practice, making your Farsi learning journey not only educational but also interactive and fun.

Also, integrating Farsi language learning into your daily life activities is an effective way to make consistent progress while also making the learning process more engaging. Here's how you can connect your daily life activities to studying Farsi:

- Cooking and Recipes: Explore Farsi cuisine by following Farsi recipes. This not only helps you learn the names of ingredients and cooking techniques in Farsi but also immerses you in the culinary culture of Iran. You can find Farsi recipes online or in Farsi cookbooks.

- Exercise and Physical Activities: If you enjoy physical activities, consider watching Farsi-language workout videos or practicing yoga with Farsi instructions. This combines your interests with language learning and keeps you engaged.

- Gardening: If you have a garden or indoor plants, learn the Farsi names for different plants and gardening terms. This allows you to apply your language skills while tending to your garden.

- Shopping: When shopping for groceries or other items, practice naming products and reading labels in Farsi. You can also use Farsi phrases for greetings and polite interactions with shopkeepers.

Advanced Farsi Learning Tips

To elevate your Farsi skills beyond the basics, immerse yourself in advanced grammar resources and textbooks, while reading Farsi literature and media to expand your vocabulary. Watch Farsi films and engage with native speakers for colloquial fluency. Additionally, explore specialized resources and maintain consistent practice to deepen your language proficiency and achieve advanced levels of competence.

We recommend you to practice the language by enjoying the Farsi culture. How? Listening to songs by iconic Iranian artists like Googoosh, Mohammad Reza Shajarian, and Dariush , as their music offers a rich blend of cultural and linguistic elements. For movies, classics like "A Separation" (Jodaeiye Nader az Simin) and "Children of Heaven" (Bacheha-Ye Aseman) provide captivating storytelling and authentic dialogues. In the realm of literature, start with Persian poets like Rumi and Hafez, whose works are celebrated for their profound wisdom and lyrical beauty, or explore contemporary authors like Khaled Hosseini, known for "The Kite Runner" (Charkheh Baz) and "A Thousand Splendid Suns" (Hazar Afsanah Isy) . These recommendations will not only enhance your language skills but also provide a deeper understanding of Persian culture and history.

Online Courses for Learning Farsi

Online courses offer a host of benefits for Farsi language learners, particularly in the convenience and flexibility they provide. Learners can access high-quality Farsi courses from anywhere in the world, allowing for personalized, self-paced learning that suits individual schedules. Furthermore, online courses frequently offer opportunities for peer interaction and feedback through discussion forums or live sessions, fostering a sense of community and collaboration among learners.

- University of Tehran - Farsi Online: This course is designed for both beginners and intermediate learners and covers a wide range of language skills, including reading, writing, listening, and speaking . It includes video lessons, interactive exercises, and cultural insights, making it a well-rounded learning experience. Learners can choose from various modules based on their proficiency level and specific language goals.

- University of Maryland - Persian Language and Culture: This course emphasizes practical language skills and cultural understanding. It includes lessons on Farsi grammar, vocabulary, and pronunciation, as well as insights into Persian traditions, literature, and history. It's suitable for beginners and intermediate learners seeking a well-structured and informative course.

- Farsi Language Academy - Farsi Course : This online academy provides structured lessons on Farsi grammar, conversation, and writing skills. What sets it apart is its emphasis on conversational fluency, with practical exercises and opportunities to engage in live conversations with native Farsi speakers, fostering a dynamic learning environment. The course also includes cultural insights, helping learners understand the broader context of the language they are acquiring.

Farsi Tutoring

Having a Farsi tutor is essential for a truly immersive language learning experience. Tutors provide personalized guidance, immediate feedback, and tailor-made lessons that cater to individual learning needs, ensuring effective progress. Moreover, regular interaction with a tutor improves speaking and listening skills, boosting confidence in real-life conversations and fostering a genuine connection to the language and its culture. Explore these platforms to find a Farsi tutor:

- Italki: This app presents several advantages for learning Farsi, including access to native speakers who offer authentic language instruction, personalized lessons tailored to individual learning goals and schedules, cost-effective language instruction, trial lessons for tutor compatibility testing , cultural insights, various lesson formats, and the convenience of an online learning platform, making it an excellent resource for Farsi learners seeking a comprehensive and flexible language learning experience.

- Preply: The platform allows learners to choose tutors who align with their specific learning needs, whether focused on conversational practice, grammar, or exam preparation. Flexible scheduling options accommodate varying time zones and busy lifestyles, making it convenient for learners to access quality Farsi lessons. Preply also offers trial lessons for learners to evaluate tutor compatibility, and the online learning environment provides a comfortable and accessible space for Farsi language acquisition.

- Verbling: The platform enables learners to choose tutors who align with their specific language objectives, whether they focus on conversational fluency, grammar mastery, or cultural understanding. Verbling's user-friendly interface simplifies scheduling, and learners can easily book lessons that fit their availability, even across different time zones . With a focus on immersive language learning, Verbling provides a practical and interactive environment for learners to advance their Farsi proficiency, making it a valuable resource for those seeking comprehensive language instruction.

Farsi Learning Apps

Farsi language learning apps often provide interactive lessons, quizzes, and exercises that cater to various proficiency levels, allowing learners to progress at their own pace. Many apps also incorporate features like speech recognition and pronunciation practice, providing immediate feedback for improved language skills. Check out these options:

- Memrise: The app provides a wide range of Farsi courses created by both experts and native speakers, covering diverse topics and proficiency levels. Memrise's spaced repetition system and interactive lessons help learners memorize and retain vocabulary effectively . It also includes multimedia content, such as videos of native speakers, to improve listening and pronunciation skills. The community aspect allows learners to engage with fellow learners, fostering a sense of motivation and accountability

- HelloTalk: It connects learners with native Farsi speakers for language exchange, providing an immersive and practical learning experience. Users can engage in text, voice, or video conversations with native speakers, improving their speaking and listening skills in real-life contexts. The app includes correction and translation features, allowing learners to receive feedback on their Farsi writing and better understand unfamiliar words or phrases.

- Pimsleur: The program emphasizes spoken language skills, allowing learners to concentrate on pronunciation, intonation, and real-world conversations. Pimsleur's audio-based lessons promote active participation, enabling learners to respond and engage in Farsi dialogues from the very beginning . The structured curriculum progressively builds on previously learned material, enhancing retention and recall.

Books to Learn Farsi

Using teaching books for learning Farsi is crucial because they offer structured, comprehensive lessons that cover all language aspects, from grammar to vocabulary. Consider these options:

- "Complete Farsi" by Narguess Farzad: It is a comprehensive Farsi language resource known for its clear and accessible approach to learning. It covers all aspects of the language, including grammar, vocabulary, pronunciation, and cultural insights. The book's well-structured lessons are designed for both beginners and intermediate learners , offering a systematic progression to build language skills effectively.

- "Colloquial Persian" by Abdi Rafiee: It is a renowned language resource focusing on spoken Persian and everyday conversational skills. It emphasizes practical language use, providing learners with the tools to engage in real-life conversations. The book covers essential grammar and vocabulary while offering insights into colloquial language, idiomatic expressions, and cultural nuances.

- "Farsi Grammar in Use" by A. Aryanpour : Comprehensive guide to Persian grammar, known for its clear explanations and practical approach. It covers a wide range of grammar topics, from basic to advanced, and includes exercises to reinforce learning. The book is particularly helpful for learners seeking an in-depth understanding of Persian grammar rules, sentence structure, and verb conjugations.

Videos and Podcasts in Farsi

Videos and podcasts are invaluable resources for learning Farsi as they offer immersive and dynamic learning experiences. Videos provide visual context, allowing learners to see and hear native speakers, observe facial expressions, gestures, and body language, enhancing comprehension and cultural understanding. Podcasts, on the other hand, are convenient for improving listening skills and can be consumed on the go , turning commute or downtime into productive language learning opportunities. Explore these video channels and podcasts:

- Chai and Conversation : A podcast that offers engaging audio lessons that focus on practical, day-to-day language use, making it an excellent choice for learners seeking to develop their conversational skills. The lessons cover a wide range of topics, cultural insights, and essential vocabulary, and they are presented in an accessible and enjoyable format, often centered around the theme of enjoying tea ('chai') while learning the language.

- Learn Persian with Chai Khana: A YouTube channel that features a series of entertaining videos, often centered around everyday situations and narratives, designed to help learners improve their language skills. The platform aims to make Farsi learning enjoyable and relatable by combining language lessons with cultural insights, thus providing a holistic understanding of the language and its cultural context.

- Easy Persian : A website and YouTube channel dedicated to simplifying the process of learning the Persian (Farsi) language. It offers a wealth of free resources, including lessons, vocabulary, and cultural insights. The website is particularly known for its user-friendly approach, breaking down complex language concepts into easily understandable segments. 'Easy Persian' aims to provide learners, especially beginners, with accessible tools to develop their reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills in Farsi.

How to learn Farsi: Conclusion

Congratulations! You now have a comprehensive guide on how to learn Farsi. By following these steps and utilizing the resources mentioned, you'll be well on your way to becoming fluent in this beautiful language. Remember, the key to success is consistency and enthusiasm. So, dive in, explore, and enjoy your Farsi language learning journey!

How long does it take to learn Farsi?

The time it takes to learn Farsi varies from person to person. With consistent effort, basic conversational proficiency can be achieved in several months to a year. Full fluency may take several years of dedicated study.

How hard is it to learn Farsi?

Farsi can be challenging for English speakers due to its unique script and grammar. However, with the right resources and dedication, it's certainly attainable for anyone.

How can I learn Farsi quickly?

To accelerate your learning, immerse yourself in the language, practice daily, and seek help from native speakers or tutors. Utilize online courses and apps to structure your learning.

How can I learn Farsi at home on my own?

Online courses, language apps, books, and language exchange platforms are great tools for self-study. Create a study routine and stay consistent.

How can I become fluent in Farsi?

Becoming fluent in Farsi requires continuous practice, exposure to native speakers, and deepening your understanding of the language through advanced resources. Consistency is key to fluency.

Related articles

- Most Spoken Languages in Asia

- How To Learn ASL

- Most Spoken Languages in Africa

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The achaemenid persian empire (550–330 b.c.).

Fluted bowl

Vessel terminating in the forepart of a fantastic leonine creature

Relief: two servants bearing food and drink

Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2004

The Achaemenid Persian empire was the largest that the ancient world had seen, extending from Anatolia and Egypt across western Asia to northern India and Central Asia. Its formation began in 550 B.C., when King Astyages of Media, who dominated much of Iran and eastern Anatolia (Turkey), was defeated by his southern neighbor Cyrus II (“the Great”), king of Persia (r. 559–530 B.C.). This upset the balance of power in the Near East. The Lydians of western Anatolia under King Croesus took advantage of the fall of Media to push east and clashed with Persian forces. The Lydian army withdrew for the winter but the Persians advanced to the Lydian capital at Sardis , which fell after a two-week siege. The Lydians had been allied with the Babylonians and Egyptians and Cyrus now had to confront these major powers. The Babylonian empire controlled Mesopotamia and the eastern Mediterranean. In 539 B.C., Persian forces defeated the Babylonian army at the site of Opis, east of the Tigris. Cyrus entered Babylon and presented himself as a traditional Mesopotamian monarch, restoring temples and releasing political prisoners. The one western power that remained unconquered in Cyrus’ lightning campaigns was Egypt. It was left to his son Cambyses to rout the Egyptian forces in the eastern Nile Delta in 525 B.C. After a ten-day siege, Egypt’s ancient capital Memphis fell to the Persians.

A crisis at court forced Cambyses to return to Persia but he died en route and Darius I (“the Great”) emerged as king (r. 522–486 B.C.), claiming in his inscriptions that a certain “Achaemenes” was his ancestor. Under Darius the empire was stabilized, with roads for communication and a system of governors (satraps) established. He added northwestern India to the Achaemenid realm and initiated two major building projects: the construction of royal buildings at Susa and the creation of the new dynastic center of Persepolis , the buildings of which were decorated by Darius and his successors with stone reliefs and carvings. These show tributaries from different parts of the empire processing toward the enthroned king or conveying the king’s throne. The impression is of a harmonious empire supported by its numerous peoples. Darius also consolidated Persia’s western conquests in the Aegean. However, in 498 B.C., the eastern Greek Ionian cities, supported in part by Athens, revolted. It took the Persians four years to crush the rebellion, although an attack against mainland Greece was repulsed at Marathon in 490 B.C.

Darius’ son Xerxes (r. 486–465 B.C.) attempted to force the mainland Greeks to acknowledge Persian power, but Sparta and Athens refused to give way. Xerxes led his sea and land forces against Greece in 480 B.C., defeating the Spartans at the battle of Thermopylae and sacking Athens. However, the Greeks won a victory against the Persian navy in the straits of Salamis in 479 B.C. It is possible that at this point a serious revolt broke out in the strategically crucial province of Babylonia. Xerxes quickly left Greece and successfully crushed the Babylonian rebellion. However, the Persian army he left behind was defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Plataea in 479 B.C.

Much of our evidence for Persian history is dependent on contemporary Greek sources and later classical writers, whose main focus is the relations between Persia and the Greek states, as well as tales of Persian court intrigues, moral decadence, and unrestrained luxury. From these we learn that Xerxes was assassinated and was succeeded by one of his sons, who took the name Artaxerxes I (r. 465–424 B.C). During his reign, revolts in Egypt were crushed and garrisons established in the Levant. The empire remained largely intact under Darius II (r. 423–405 B.C), but Egypt claimed independence during the reign of Artaxerxes II (r. 405–359 B.C). Although Artaxerxes II had the longest reign of all the Persian kings, we know very little about him. Writing in the early second century A.D., Plutarch describes him as a sympathetic ruler and courageous warrior. With his successor, Artaxerxes III (r. 358–338 B.C), Egypt was reconquered, but the king was assassinated and his son was crowned as Artaxerxes IV (r. 338–336 B.C.). He, too, was murdered and replaced by Darius III (r. 336–330 B.C.), a second cousin, who faced the armies of Alexander III of Macedon (“the Great”) . Ultimately Darius III was murdered by one of his own generals, and Alexander claimed the Persian empire. However, the fact that Alexander had to fight every inch of the way, taking every province by force, demonstrates the extraordinary solidarity of the Persian empire and that, despite the repeated court intrigues, it was certainly not in a state of decay.

Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “The Achaemenid Persian Empire (550–330 B.C.).” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/acha/hd_acha.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Briant, Pierre. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns, 2002.

Wiesehöfer, Josef. Ancient Persia: From 550 BC to 650 AD . London: I.B. Tauris, 1996.

Additional Essays by Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Hittites .” (October 2002)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Halaf Period (6500–5500 B.C.) .” (October 2003)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Ubaid Period (5500–4000 B.C.) .” (October 2003)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Ur: The Royal Graves .” (October 2003)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Ur: The Ziggurat .” (October 2002)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Uruk: The First City .” (October 2003)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Ebla in the Third Millennium B.C. .” (October 2002)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Ugarit .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Animals in Ancient Near Eastern Art .” (February 2014)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Urartu .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Trade between the Romans and the Empires of Asia .” (October 2000)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Parthian Empire (247 B.C.–224 A.D.) .” (originally published October 2000, last updated November 2016)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Nabataean Kingdom and Petra .” (October 2000)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Palmyra .” (October 2000)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Art of the First Cities in the Third Millennium B.C. .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Sasanian Empire (224–651 A.D.) .” (originally published October 2003, last updated April 2016)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Colossal Temples of the Roman Near East .” (October 2003)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Assyria, 1365–609 B.C. .” (originally published October 2004, last revised April 2010)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Lydia and Phrygia .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Akkadian Period (ca. 2350–2150 B.C.) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Year One .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Early Dynastic Sculpture, 2900–2350 B.C. .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Early Excavations in Assyria .” (October 2004; updated August 2021)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Trade Routes between Europe and Asia during Antiquity .” (October 2000)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Phrygia, Gordion, and King Midas in the Late Eighth Century B.C. .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ Trade between Arabia and the Empires of Rome and Asia .” (October 2000)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Nahal Mishmar Treasure .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Phoenicians (1500–300 B.C.) .” (October 2004)

- Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art. “ The Seleucid Empire (323–64 B.C.) .” (October 2004)

Related Essays

- Egypt in the Late Period (ca. 664–332 B.C.)

- Ernst Emil Herzfeld (1879–1948) in Persepolis

- Lydia and Phrygia

- The Rise of Macedon and the Conquests of Alexander the Great

- Tiraz : Inscribed Textiles from the Early Islamic Period

- Art and Craft in Archaic Sparta

- Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition

- Artists of the Saqqakhana Movement

- Assyria, 1365–609 B.C.

- Classical Cyprus (ca. 480–ca. 310 B.C.)

- Egypt in the Ptolemaic Period

- Geometric and Archaic Cyprus

- Greek Art in the Archaic Period

- Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

- Hellenistic Jewelry

- The Middle Babylonian / Kassite Period (ca. 1595–1155 B.C.) in Mesopotamia

- Nineteenth-Century Iran: Continuity and Revivalism

- The Parthian Empire (247 B.C.–224 A.D.)

- Phrygia, Gordion, and King Midas in the Late Eighth Century B.C.

- Theseus, Hero of Athens

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Mesopotamia

- List of Rulers of Ancient Egypt and Nubia

- List of Rulers of the Ancient Greek World

- Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Central and North Asia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- The Eastern Mediterranean and Syria, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Egypt, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Iran, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Mesopotamia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- South Asia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- 4th Century B.C.

- 5th Century B.C.

- 6th Century B.C.

- Achaemenid Empire

- Anatolia and the Caucasus

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Ancient Near Eastern Art

- Architectural Element

- Architecture

- Babylonian Art

- Balkan Peninsula

- Central and North Asia

- Eastern Mediterranean

- Greek Literature / Poetry

- Hellenistic Period

- Late Period of Egypt

- North Africa

- Relief Sculpture

bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250]

Farsi Language Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Farsi language in iranian classroom, iranian pronunciation in the english language, challenges of efl learning in iran, influences of english speaking on efl learners.

The purpose of writing this essay will be to examine the various varieties of English that exist in Farsi language classrooms and also to determine the type of English language pronunciation that Iranian learners are aiming for and the interference of Farsi language in attaining the desired pronunciation levels. The focus or context of the study will be on Iranian children between the ages of 16 and 18 years who are in high school and are learning English as a foreign language (EFL).

The reason for selecting high school students is that the teaching of English as a foreign language has been on the increase in most high schools in Iran for the past two decades. Despite this increasing interest in learning English within educational institutions, little knowledge exists on what actually happens within Iranian EFL classrooms in most high schools in the country (Rezvani and Rasekh 2011).

This study will seek to address this gap by determining the varieties of English that exist in Farsi language classrooms as well the type of pronunciation that most Iranian students seek to attain. The use of metaphors during English learning lessons within Iranian schools will also be explored as metaphorical expressions have contributed significantly to the pronunciation of Farsi speakers undertaking English language lessons.

The study will also address the influences of English which have mostly been attributed to the globalization process around the world and the growing need to communicate in English (Davis 2006). English as an international language (EIL) refers to how it is viewed as a global means of communicating within very many dialects and how the English language is viewed as an international language.

As a world-renown language, English mostly places importance on learning the diverse parlances and other forms of speaking, writing and reading English and it aims to provide individuals with the necessary linguistic tools which will allow them to communicate in a more global or international context.

English as an international language is also used to develop and nurture the communication skills of various people who exist in diverse cultures around the world because it is a common language (Acar 2006). There are very many varieties of English with some of the most common being American English and British English.

The British English dialect differs from American English in terms of accent, pronunciation, vocabulary and grammar. The British dialect mostly accentuates the English grammar and pronunciation and their dialect differs from that of American English in terms of accent.

The pronunciation of English words varies significantly amongst British speakers when compared to American speakers of the language. American English, which is mostly used in many Iranian schools, incorporates differences in pronunciation and vocabulary and also the dialect.

The other dialects of English, which are used in the various countries around the world include Burmese English, which is spoken by people from Burma in the Asian continent, Portuguese English, Australian English, European English, Caribbean English and other forms of English (Wakelin 2008).

While American English is used in most English learning classes in Iran, the pronunciation of the language is basic or general English meaning that English learners in the country do not have any American or British accents when speaking the language.

In their analysis of how Farsi or Persian language is used in the classroom setting, Tucker and Corson (1997) noted that the type of tasks students were involved in during class time varied significantly in Farsi speakers that were studying English as a foreign language.

Varieties in English grammar, pronunciation and vocabulary were mostly notable in direct translations, visual descriptions and grammatical explanations. This demonstrated that an accurate measurement of inter-language competency was needed to take into account different conditions and stages of English speaking and learning within Farsi language classrooms (Majd 2008).

The strategic competence of Iranian students when it came to inter-language use was explored by Yarmohamadi and Seif in their 1992 study where they set out to determine the communicative ability of these students in handling problematic English concepts.

Iranian students that were studying English at the various levels and stages of high school were assessed based on their placement of primary stress and emphasis on English words and the use of morphological, syntactic and phonological hierarchies to determine the complexity of English words.

The results of their assessment demonstrated that the use of such measures was able to determine the communication proficiency of many of the students as well as their pronunciation of the varieties of English that were used during classroom instruction (Yarmohamadi and Seif 1992).

With regards to the varieties of English within Iranian classrooms, Taki (2010) conducted an assessment where two groups of Persian and English language teachers were selected to provide some correspondence for metaphorical equivalents based on their use of both Farsi and English languages during the instruction of students.

The criteria used by Taki was whether they taught the high school students with their native language, their familiarity with metaphorical languages, expressions and the basic knowledge that they had of concepts or figures of speech. A total of 40 animal terms were selected for comparison between English and Persian languages to determine the metaphorical variety that existed between the two languages.

The purpose of conducting this study was to determine whether the use of metaphorical expressions aided Iranian students in their English learning activities (Taki 2010).

The results of Taki’s study revealed that the metaphorical expressions used in both languages were 20% similar for animal terms that were presented to the respondents. This corroborated the idea many linguists have developed on the partial mappings or metaphorical expressions that exist between the same source of information and the target domains of both the Farsi and English languages.

The results also revealed that 50% of the metaphorical expressions used to describe animal images were similar for both the English and Farsi languages and they also differed in separate ways. This meant that the metaphors worked in different ways for both languages when they were used in different contexts as they elicited different meanings from both languages (Taki 2010).

The results of the study pointed to the various similarities and differences that existed between both languages, especially when used within the school context. Metaphors played a great role in enabling the Iranian students to better understand what was being communicated to them in the English lessons.

They heightened the comprehension abilities of the students while at the same time enhancing their understanding of the English language.

Rezvani and Rasekh (2011) conducted a study to determine the teaching patterns of four Iranian EFL teachers when it came to language alternation and Farsi speaking language within the classroom setting.

The results of their study demonstrated that the four EFL teachers used code-switching tendencies during classroom interaction sections and also in the discipline of students, which was otherwise known as classroom management.

The authors viewed code-switching to be an important activity for many Iranian teachers as it enabled them to successfully interact with their students who were mostly Iranian native speakers (Rezvani and Rasekh 2011).

Most of the teaching language used by these Iranian teachers was Farsi or Persian language and therefore teaching students without any code-switching strategies proved to be difficult in relaying the proper pronunciation, grammatical representation and vocabulary of certain words (Nilep 2006: Myers-Scotton 1997).

Another study conducted by Gholamain and Geva (1999) examined the extent to which basic reading skills in both the Farsi language and American English could be understood by students after considering their underlying cognitive processes and by understanding the unique characteristics of the alphabets between the two language systems.

Farsi or the Persian language makes extensive use of sound-symbol correspondences during the pronunciation of Persian words when compared to the English language which makes limited use of sound-symbols.

Gholamain and Geva (1999) examined Persian students who were enrolled in school systems where the language of instruction was English. The researchers noted that the students performed better in measures of English reading and cognitive capabilities when compared to Farsi reading and understanding of the Persian language.

Farsi or the Persian language has been the main tool that is used for literacy and scientific contributions in the eastern part of the Islamic and Muslim world. The language is similar to that of many contemporary European languages and it has considerable influence on various languages such as Turkic languages which are used in Central Asia, Caucasus and Anatolia.

Farsi language is classified to belong to the western group of the Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family and it is termed to originate from three periods of Iranian history which include the Old period where the Achaemenid language was introduced, the Middle period which was also known as the Sassanid era and the Modern or post-Sassanid period.

The Persian language has been termed as the only Iranian language that has a close genetic relationship will all the three historic periods (Katzner 2002).

Farsi language can be spoken in three dialects which include Iranian Persian or Farsi which is mostly spoken by many people in Iran, Afghan Persian otherwise known as Dari which is used by many people in Afghanistan and Tajik Persian or Tajiki which is a common Persian language spoken in countries such as Russia, Uzbekistan and Cyria (Henderson 1994).

All these three dialects are based on classical Persian literature, which was a period in Persian history that was marked with some of the world’s best Persian language poets and linguists from the eastern parts of the world such as Rudaki, Omar Khayyam and Varand (Clawson 2004).

The heavy influence of the Persian language from the classical period has mostly been witnessed in many parts of the Islamic world especially since it is viewed as an important piece of literary work as well as a prestigious language that is used amongst the educated elite in the fields of Persian art and literature as well as in Qawwali music (Perry 2005).

Educated people from most of the Middle Eastern countries are able to comprehend each other with an elevated level of clearness, but the differences are only noticeable in their vocabulary, grammar and pronunciation. This has been termed by many linguistic scholars to be similar to the same differences in vocabulary or pronunciation that exist between British English and American English.

In terms of Farsi language morphology, Persian grammar is mostly made up of suffixes and a limited number of prefixes where there is no grammatical gender in Farsi language and there are no pronouns that can be used to denote natural gender.

The syntax that is used for the language involves declarative sentences that are structured as (S) (PP) (O) V which means that sentences can be made up of optional subjects, objects and phrases (Megerdoomian 2000).

The vocabulary that is used in Farsi languages involves the use of word-building affixes as well as nouns and adjectives. The language mostly makes the use of adding derived affixes to the base of a word so as to create a new word, noun or adjective (Perry 2005).

Since the Farsi language is part of the Indo-European languages, most of the words between English and Persian are similar like for example the English name of daughter in Persian is pronounced dokhtar, mother in English is pronounced as madar in Persian while the English name of brother is pronounced as baradar in Persian.

This demonstrates that many words that are of Persian origin have been incorporated into the English language. Most of the English vocabulary has been influenced by the Persian language and the Persian language has also had most of its grammar and pronunciation influenced by the English (Majd 2008).

This essay seeks to determine the varieties of English that are used within many high school classrooms in Iran as well as the other Middle Eastern countries that use Persian in speaking and learning activities.

In addressing the question of English pronunciation amongst Iranian high school students, Hayati (2010) notes that the pronunciation of Iranian high school students should be based on their ability to accurately and correctly pronounce different words of the English language correctly as well as hold proper dialogues with their peers.

Hayati (2010) notes that while the pronunciation of most Iranian high school students is poor, it can be improved further by sensitizing students in the conversational tactics that they use when they converse in their native language.

Most Iranian students as well as Iranian EFL learners aim to have “proper” English pronunciation, grammar and vocabulary, which have been evidenced by the growing number of EFL learners within the country.

Hayati (2010) in his case study of how Iranian EFL high school students were taught on English pronunciation focused on various factors that influenced the pronunciation of most of the EFL learners within the Iranian classroom context.