- < Previous

Home > ACADEMIC_COMMUNITIES > Dissertations & Theses > 701

Antioch University Full-Text Dissertations & Theses

The inclusion of autism spectrum disorder in mainstream classrooms: teachers’ perspectives.

Alyssa Maiuri , Antioch New England Graduate School Follow

Alyssa Maiuri, Psy.D., is a 2021 graduate of the Psy.D. Program in Clinical Psychology at Antioch University, New England

Dissertation Committee:

- Kathi A. Borden, PhD, Committee Chair

- Deidre Brogan, PhD, Committee Member

- JMina Panayoutou-Burbridge, PsyD, Committee Member

autism spectrum disorder, inclusion, general education teachers, IPA

Document Type

Dissertation

Publication Date

This dissertation explored the unique experiences of general education teachers teaching in an inclusive classroom (which will also be referred to as a “mainstream classroom”) with a combination of students with and without autism (which will also be referred to as “autism spectrum disorder” and “ASD”). This was a qualitative research study that applied the Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) research method, as presented by Smith, Flowers, and Larkin (2009). The participants in this study were seven general education teachers, each of whom taught kindergarten or fourth grade. Purposive sampling was used to gain a better understanding of the teachers’ experiences across the elementary school careers of students with autism. Four teachers taught in Massachusetts, two in New Jersey, and one in New York City. Out of the seven participants, three were kindergarten teachers and the remaining four were fourth-grade teachers. Through semi-structured interviews, participants’ experiences were shared. The data analysis involved generating emergent and superordinate themes of teacher perceptions to aid in the understanding of the teachers’ experiences. This study explored whether these experiences differed across grade levels and geographic locations, and how they compared across the full data set. Finally, the findings were discussed in the context of previous literature, what the limitations were to this study, what future directions there were for research on this topic, and my personal reflection.

Alyssa Maiuri

ORCID Scholar ID# 0000-0003-4620-735X

Recommended Citation

Maiuri, A. (2021). The Inclusion of Autism Spectrum Disorder in Mainstream Classrooms: Teachers’ Perspectives. https://aura.antioch.edu/etds/701

Since April 19, 2021

Included in

Clinical Psychology Commons

Antioch University Repository & Archive

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

AURA provided by Antioch University Libraries

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Promoting the Social Inclusion of Children with ASD: A Family-Centred Intervention

Roy mcconkey.

1 Institute of Nursing and Health Research, Ulster University, Newtownabbey BT37 0QB, UK

Marie-Therese Cassin

2 Cedar Foundation, Belfast BT6 8RB, UK; [email protected] (M.-T.C.); [email protected] (R.M.)

Rosie McNaughton

The social isolation of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is well documented. Their dearth of friends outside of the family and their lack of engagement in community activities places extra strains on the family. A project in Northern Ireland provided post-diagnostic support to nearly 100 families and children aged from 3 to 11 years. An experienced ASD practitioner visited the child and family at home fortnightly in the late afternoon into the evening over a 12-month period. Most children had difficulty in relating to other children, coping with change, awareness of dangers, and joining in community activities. Likewise, up to two-thirds of parents identified managing the child’s behaviour, having time to spend with other children, and taking the child out of the house as further issues of concern to them. The project worker implemented a family-centred plan that introduced the child to various community activities in line with their learning targets and wishes. Quantitative and qualitative data showed improvements in the children’s social and communication skills, their personal safety, and participation in community activities. Likewise, the practical and emotional support provided to parents boosted their confidence and reduced stress within the family. The opportunities for parents and siblings to join in fun activities with the child with ASD strengthened their relationships. This project underscores the need for, and the success of family-based, post-diagnostic support to address the social isolation of children with ASD and their families.

1. Introduction

Internationally, there has been a marked rise in the number of children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [ 1 ]. Early intervention is an agreed priority to ameliorate the main symptoms as soon as the condition is identified, especially in early childhood [ 2 ]. Even so, a national UK survey of more than 1000 parents found that nearly half (46%) received no follow-up appointment after the diagnosis was made and only 21% of parents received a direct offer of help/assistance. Additionally, more than 60% of parents expressed dissatisfaction with post-diagnostic support and only 5% were very satisfied with it [ 3 ].

A particular concern of parents is the lack of social and communication skills experienced by children with autism [ 4 ]. This often results in difficulties in interacting with their peers and isolation from community activities. Interventions aimed at promoting community participation have proved effective and a systematic review identified the factors that contributed to their success. This included facilitating “friendships alongside recreational participation, include typically developing peers, consider the activity preferences of children and adolescents in developing programmes, and accommodate individual impairments and needs through grading and adaptive leisure activities” [ 5 ] (p. 825).

Families are the primary caregivers of children with ASD. Tint & Weiss [ 6 ] in their scoping review noted that considerable research had detailed the correlates of the chronic physical, emotional, social, and financial stressors these families experience. They concluded that “a better understanding of family well-being of individuals with ASD is essential for effective policy and practice” (p. 262). A review of international research to date has identified promising strategies for supporting families [ 7 ] as well as targeting parental challenges such as stress, depression, and self-efficacy. “It may be especially constructive to provide wraparound services for families, in which resources and supports are provided (i.e., parent training, therapeutic services, respite care, social services, family counselling) in addition to developmental and behavioural services for the child” (p. 72).

Moreover, the impact on non-disabled siblings is worthy of attention given the increasing evidence that they fared worse in terms of psychological functioning, internalized behaviour problems, social functioning, and sibling relationships while also showing increased anxiety and depression [ 8 ].

A Canadian study into family quality of life (FQOL) who have a child with ASD found that opportunities to engage in leisure and recreation activities for the family as a whole was associated with an increased FQOL [ 9 ]. However, many families are not engaging in these activities on a regular basis. These researchers recommended that: “service providers could offer leisure and therapeutic recreation options to families, while they wait for other therapeutic services in order to provide additional options to families with a child with ASD.” (p. 340).

Tint & Weiss [ 6 ] also identified the value of parents meeting other parents. Research studies indicate that socially isolated mothers may experience greater stress and have fewer socially satisfying interactions with their children. “Participating in group interventions may be beneficial for parents of children with ASD because it provides them with an opportunity to connect with other parents who are having similar experiences” (p. 94).

To date, most research studies have been undertaken with better educated, more affluent parents and little attention has been paid as to how ‘under-resourced’ families (those with low incomes and limited education) can be better supported when a child has ASD. A small-scale study in the USA found that “specific strategies to increase participant retention and decrease attrition included providing sessions in home, reducing travel requirements... and providing community resource support. One of the strengths was the presence of a strong referral system... and a team committed to helping patients access ASD-specific services” [ 10 ] (p. 94). More generally, a systematic review of home visiting programs for disadvantaged families concluded that: “home visitation by paraprofessionals is an intervention that holds promise for socially high-risk families with young children” [ 11 ] (p. 1).

The foregoing review provided the rationale for the family-centred, post-diagnostic support service to families and children aged 4 to 11 years with ASD in rural counties of Northern Ireland. The main focus was on promoting the social inclusion of the child and family within their local communities.

2. Materials and Methods

The project was conceived and delivered by the Cedar Foundation, which is a voluntary, non-profit organisation with a long history of delivering services to people with disabilities and their families. Charitable funding was obtained from the UK Big Lottery Fund for a five-year period.

A logic model was developed to guide the design and implementation of the service as well as its evaluation (see Figure 1 ). The model summarises the theory of change as to how the intervention would produce the intended outcomes in the short term and the possible longer-term consequences for the child and family [ 12 ].

The logic model for the family-centred intervention.

2.1. Description of Inputs and Activities

Five project workers including one full-time and two part-time job shares each covered one of three counties in the western part of Northern Ireland, which is largely rural with a higher proportion of under-resourced families. All staff had a bachelor’s degree in psychology plus a minimum of one year of paid experience. In addition to their qualifications and experience in autism, they received further training in ASD during the course of the project. Fortuitously, the appointed workers lived in the county in which they worked and were familiar with the community resources available there.

The project workers were line managed through Cedar’s Community Services Manager who also managed Cedar’s other projects in the western area. Links with these projects provided project workers with further support and training.

Each family received fortnightly visits for a 12-month period. However, all families were given opportunities to maintain contact with the project and to participate in all future group activities.

Quarterly meetings were held in each county between Cedar staff and the social workers from the children’s ASD multi-disciplinary team of the statutory Health and Social Care Trust who undertake assessment and diagnosis of ASD. Potential referrals of families to the project were discussed with the social workers and the ongoing case load of families and children reviewed. An extension of time on the project was agreed for those families who had continuing needs. Similarly, families deemed to have higher needs were given priority when a place became available on the project.

A project worker visited the child and family at home in the late afternoon into the evening once every two weeks on average. The first visits were used to assess the child and family needs and agree on an individual plan for meeting those needs. The project worker devised and implemented learning activities to address the children’s needs. These occurred within the family home or on outings to community locations and activities. The aim was to embed the learning in real-life settings, which schools are often unable to do.

Project staff made learning aids, such as visual schedules or story books. These resources were left for the families to use.

The visits also provided opportunities to advise and guide the families on managing the child’s behaviour as well as furthering their learning. As the relationship with the project worker developed, families became more open about further issues and worries they had. As well as providing emotional support, the workers signposted families to other services in their locality.

The home visits were at a time when the project workers met other family members such as siblings and fathers. If appropriate, siblings were also invited to join in the activities the project worker undertook with the child, with the goal of enhancing the child’s inclusion in family activities.

The project worker introduced the child to community activities in line with their learning targets and wishes. These provided opportunities to teach road safety or social interactions with other children as well as introducing the child to leisure activities such as swimming, horse-riding, football, and youth clubs.

Project workers also made contact with schools if required but especially for children with ASD who were soon to transfer from primary to secondary school. This gave opportunities for devising common approaches across home and school settings. These visits have led to increased contact between the schools and families.

Family Fun days were organized in each county four times a year and families were invited to attend. Siblings were especially welcome along with the fathers and mothers. They were held in community locations such as leisure centres or soft-play facilities with a range of activities organized to provide social interactions among the children and among the parents. The intention was also to introduce families to locations to which they could take their children in the future.

Parent Networking meetings were organized in two counties since there was less interest in a third county where parents already had access to other parent groups. An invited speaker talked on a topic of interest or else ‘pampering sessions’ for mothers took place.

Sibling groups were also provided in one county as a trial that brought together the brothers and sisters for play activities, but they also provided opportunities for them to learn more about autism and how they could respond to their sibling’s behaviours.

2.2. The Characteristics of Families and Children Involved with the Project

In all, 92 families with 96 children with ASD were involved with the project over a four-year period.

One quarter of families (25%) had a lone parent, which is higher than the Northern Ireland average of 18%. More than two-thirds had a wage earner in the family but more than one-quarter were dependent on social security benefits. This is also higher than the average for Northern Ireland, which is 16.1%. Around half of the families (51%) lived in the top 30% of socially deprived areas in Northern Ireland with very few families coming from more affluent areas. Thus, the project had recruited and retained under-resourced families, which was its intention.

Of the 96 children, 76 (79.2%) were male and 20 (20.8%) were female. The median age when they joined the project was 7.7 years (range of 3.4 to 11.8 years).

A small proportion of the children were enrolled in a special school or special unit attached to a mainstream school (14.5%) but most attended their local primary school (85.5%). However, 79 children (82.3%) had a statement of special educational needs and others were in the process of being assessed for such. Seven children (7.3%) had an additional learning difficulty. This group were enrolled at the start of the project but, in later years, children with a learning disability and autism were not referred to the project.

More than one-third of the children (35.5%) were an only child. Three families had two children with ASD who also participated in the project.

Further details of the difficulties experienced by the children with ASD are given below.

2.3. Evaluation of Project Outcomes

The first author was the external evaluator and a mix of qualitative and quantitative descriptive data was collected. The qualitative data was obtained through face-to-face interviews conducted with all the project staff and their managers (seven in all) and the three social workers who referred families to the project. Seven parents were interviewed at one of two family events. In addition, telephone interviews were conducted with 10 parents chosen by project staff to represent the range of children and families involved in the project across the three counties. Self-completion questionnaires requesting their views on the project and perceived outcomes were completed by a further 15 families who responded to an invitation sent to all parents by project staff as a text message.

The quantitative data was obtained through two rating scales that were developed in association with the project staff with one relating to the child and another relating to the family (see Table 1 and Table 2 in the results section). They provided a means for assessing each child’s difficulties at the start of their involvement and the outcomes achieved as a result of their involvement. Similarly, family needs could be identified and outcomes could be assessed. The project staff completed both rating scales based on their records for all the families with whom they had been involved and the reviews they had undertaken with them during and at the end of the home visits.

The number and percentage of children rated by staff on outcomes achieved.

The number and percentage of families rated by staff on outcomes achieved.

Formal ethical approval was not required since this study was deemed an evaluation of an ongoing service and not a research project according to Guidance from the UK Health Research Authority. Families gave consent for the information they provided directly or indirectly to be used anonymously in any reports on the project internally and externally, such as to project funders.

The evaluation was completed at the end of December 2019.

Due to time and resource constraints, information was not obtained from the children about the project nor were any external assessments available of their developmental progress. Moreover, there was no comparable group of children and families who did not receive the service since this was not ethically feasible for Cedar Foundation to undertake.

3.1. Children’s Difficulties and Outcomes

The project staff who had been involved with the children and families helped to devise a summary tool for assessing each child’s difficulties at the start of their involvement and the outcome achieved in relation to them. Table 1 lists the items and the ratings provided by the project worker across the 96 children, but some items were omitted for some individuals due to uncertainty or irrelevance for the child or family. Hence, the totals do not add to 96. The percentages are calculated on the number of ratings made.

The first column of Table 1 describes the issues that were of concern to families about their child with ASD at the start of their involvement with the project. The lower the percentage, the more children for whom the difficulty was identified. In all, eight of the sixteen listed difficulties were ones affecting the majority of families.

Difficulties in relating to other children affected all of the children in the project. The next most common cluster of difficulties related to awareness of dangers, difficulty with change, and joining in community activities with over seven in eight children affected by them. A cluster of emotional reactions was the next most common and this included anxiety, extreme fear and nervousness, anger, and meltdowns. In addition, more than 50% of children had problems with following instructions.

By contrast, some difficulties were identified by fewer than one in five children even though they include behaviours commonly associated with ASD such as an unusual response to something new, unusual interest in toys or objects, problems with play, and keeping themselves occupied.

Overall, the median number of issues identified as being a difficulty for the child was eight (range of 3 to 14).

3.2. Changes in the Children

Columns 2 and 3 in Table 1 indicate the outcomes from the help provided by the project. On all items, the difference in the ratings was significantly different from what would be expected by chance (Chi Square tests p < 0.001). Column 2 indicates difficulties that had improved since participating in the project and which were now considered less of a problem. The majority of children had improved on the six most commonly mentioned difficulties including relating to other children, awareness of dangers, coping with change, joining in community activities, and managing anxieties and fears. In all the median number of difficulties on which children were deemed to have improved was seven (range 1 to 13).

Column 3 indicates the difficulties that remained a problem even though project staff had addressed it and, as such, they represent a continuing need for children and families. The most common – albeit for only one in five children or less - were the top three items listed in Table 1 , which include notable difficulty in relating to other children, in awareness of danger, and in managing change. Overall, most children had no difficulties that were a continuing problem, but others had up to 10 difficulties that continued.

3.3. Issues for Families and Outcomes

The issues that commonly face families who have a child with ASD were listed in a similar rating scale to that used for the child’s difficulties. Table 2 lists the items and the ratings provided by the project worker.

The first column of Table 2 indicates the issues that were of concern to families at the start of their involvement with the project. The lower the percentage, the more families for whom the issue was identified. In all, nine of the 14 were issues that affected the majority of families. Having knowledge about the services and supports available was the most common and identified in 96% of families. Up to two-thirds of families identified managing the child’s behaviour, having time to spend with other children, and taking the child out of the house as the main issues.

By contrast, three issues affected 20% of parents or less including family quality of life, main caregiver being anxious or depressed, and having people to turn to if a problem arose. Overall, families were presented with a median of seven different issues (range from 0 to 11 issues identified).

3.4. Outcomes for Families

Columns 2 and 3 of Table 2 indicate the outcomes from the help provided by the project. On all items, the difference in the ratings was significantly different from what would be expected by chance (Chi Square tests, p < 0.001). The second column indicates issues that were deemed to be no longer an issue for families. The two issues that a majority of families (50% and over) benefited from were: knowing the supports and services available and having time to spend with other children. In addition, more than two in five families also gained from communication with schools, the child going out of the house, meeting other parents, and finding activities that the whole family can join in. In all, families had a median of five issues resolved (range from 0 to 11).

3.5. Perceptions of Project Outcomes and Impact

The perceptions of three groups of stakeholders were sought regarding the outcomes of the project for the children and for the families as a whole: namely parents ( n = 16), project staff ( n = 7), and social workers who had referred children to the project ( n = 4). This information was obtained mostly through one-to-one interviews, which were audio-recorded and transcribed and were supplemented by self-completed questionnaires. A thematic content analysis using the framework proposed by Braun & Clarke [ 13 ] was undertaken. The initial codes derived from the responses were grouped under two core themes: the impact on the child and the impact on families. Table 3 summarises the subthemes along with supporting quotations from parents that the other respondents confirmed. The person quoted is noted in brackets.

The themes and subthemes reported as outcomes of the project by parents.

All the stakeholders recounted various impacts that the project had on the children, which elaborated the changes noted in Table 1 . Enhanced social interactions were a common outcome since the children learned to overcome their difficulties in interacting with their siblings and other children. Improvements in the children’s behaviours were also noted with fewer meltdowns and less anger. The acquisition of new skills was confirmed especially those needed when accessing community facilities.

The stake-holders also confirmed the impact of the project on families. Parents had learned new ways of interacting with their child from the project workers. The changes they saw in their child boosted their confidence and this, coupled with the opportunity to have some free time to spend with their other children, resulted in them feeling less stressed. They also appreciated the opportunity to meet with other parents.

3.5.1. The Most Successful Aspects of the Project

Not surprisingly, the stake-holders identified different aspects of the project that they considered to be particularly successful. To some extent, this reflects the diversity of needs that families and children present and the flexibility of the project in meeting their needs. For most though, the one-to-one work with the children were the most frequently cited.

She had a great rapport with him, you know, she really met him at his level and he never said I don’t want her coming, never, never did. She has a fantastic rapport with him. (Mother JU)

Listening to families and addressing their concerns was seen as vital.

They were very good at consulting with the parents in what we wanted and what we needed and then they would have done their plans around that. (Mother T)

The social aspects were also valued for both the child and the family.

They got a wee buddy system as well where he was going out with his friend, he met a wee friend a couple of days and the two of them went out together. (Mother T.)

The most successful aspect of the project is seeing families come together and be able to participate in family activities which all family members can be included in. (Project staff)

The trusted relationship between the project and the social workers who had referred families brought benefits to both.

There’s brilliant relationships with us and Cedar... there’s a two-way flow of communication. When a family is known to Cedar... that family does not need to contact us. They do not seem to need us. Their issues have been dealt with it. That really allows our social workers to deal with families with even more complex needs. It’s been a real resource to us in that way: to staff as well as to the families. (Trust staff 4)

3.5.2. Improvements for the Project

Parents would have liked the project to have continued for longer and for more family days to be provided. Reduced waiting times for a place on the project was also noted. Project staff would welcome more contact with schools so that the strategies used in school and at home could be shared and closer links nurtured between schools and parents.

4. Discussion

This project is unique in a number of respects and the lessons from it can inform the provision of post-diagnostic support services for families whose children have ASD.

The project focused on promoting the social inclusion of children within their families and the local community. These two settings —the family and the community—provided the context in which children’s skills could be enhanced and practical support could be provided to families. Yet this approach stands in contrast with the focus on therapeutic approaches often used with children who have ASD [ 2 ]. Nevertheless, the focus on social inclusion brought about other specific gains to the child and to families as shown by the issues that were resolved during the project. Moreover, equipping children and families with the skills needed to function socially has potentially longer-term gains for the child as the Logic Model for the project identified (see Figure 1 ).

The project aimed to support families as well as the child especially ‘low-resource’ parents that the project had targeted. The most commonly expressed need was for information about available services and supports. This needs to be provided on an ongoing basis as parents’ needs will change over time. Regular home-based contact with parents created a trusted and more intimate relationship between staff and parents, which clinic visits or occasional parent-teacher meetings would find hard to replicate. Two outcomes are worth underlining. Parents’ self-confidence was boosted, which is a necessary prelude for them to instigate new ways of interacting with their child and trying new approaches. Additionally, many parents reported a reduction in stress within the family as they became more adept at managing the child’s behaviour and meltdowns. Hence, interventions solely focused on the child will not necessarily bring about the practical and emotional supports that parents need [ 7 ].

The choice of home-based supports was not just for practical reasons. Although, in rural areas, it overcame the lack of transport options available to low resourced families in particular. Rather, having project staff coming to the child’s home ensured that all the project work was personalised to the individual needs of the child and family [ 14 ]. Although children with ASD may share some common features, there were marked differences in how ASD was manifested in even this relatively homogenous sample of children. When the diversity found among families is added in, then the need for individualised interventions become ever more apparent. Admittedly, home visits are a more costly option than group-based parent training sessions. Yet, this is the only alternative presently offered to most parents in Northern Ireland and likely elsewhere. However, the uptake of group-based training is low especially for low resourced families and, to date, there is limited evidence as to the effectiveness of such training [ 15 ].

The project aimed to address the needs of siblings of the child with ASD who are often overlooked in ASD interventions. By contrast, parents are very aware of the impact the child with ASD has on their other children. Going to the family home meant that the staff could include the siblings in activities designed to help the child. The organisation of family days was another means of involving siblings in play and recreational activities. Both of the foregoing were arguably more successful that organising sessions for groups of unrelated siblings, which had been tried even though other studies have shown sibling support groups to be effective [ 16 ]. These may work better for teenage siblings whereas the siblings of the children in the project were mostly under 12 years of age. Nonetheless, the main message is that family interventions have to extend beyond parents to embrace siblings as well.

As with any innovative project, there are inevitably improvements that could be made to the service. Currently, the demand for it exceeds the places that can be available at any one time and, with increasing numbers of children being identified, this situation will worsen [ 17 ]. One option would be to reduce the length of time families are visited by the project or to increase the time between visits. Both options would allow more families to be accommodated for the same cost. Future research and evaluation could test out these options even though the solution is more likely for projects to become adept at adjusting their service to family needs and outcomes rather than having equivalent service inputs across all families.

The longer-term impact of the service also bears further study. There is evidence that early preschool intervention for children with developmental delays does result in longer term legacies [ 18 ], but this has yet to be determined for older children with ASD as well as for their families.

Evaluation methods could also be improved if the necessary resources were made available by the commissioners of new services. Pre-test and post-test measures of the children and parents would provide more robust evidence of change, as would the recruitment of a ‘waiting list’ control group to identify the improvements that might occur over a period of time even without any intervention.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, post-diagnostic support for children with ASD and their families is vital. Providing cost-effective ways is a priority as is gathering evidence to show its impact. Staff trained in ASD but from non-clinical backgrounds, such as in this project, are an effective means of providing home-based community support to children and families.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to the project staff, parents, and colleagues in the Western Health and Social Care Trust for their active participation.

Author Contributions

M.-T.C. and R.M. (Rosie McNaughton) designed the service, obtained funding for it, and provided managerial support and leadership throughout. R.M. (Roy McConkey) was commissioned by the Cedar Foundation to evaluate the project and he undertook the data analysis and initial drafts of the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

The UK Big Lottery and the evaluation by the Cedar Foundation funded the project.

Conflicts of Interest

R.M. (Roy McConkey) received a fee from the Cedar Foundation and M.-T.C. and R.M. (Rosie McNaughton) are employed by the Cedar Foundation. However, neither the project funders or the Cedar Foundation had any influence on the evaluation of the project and the reporting of the findings.

Advertisement

Educator Attitudes Towards the Inclusion of Students with Autism Spectrum Disorders in Mainstream Education: a Systematic Review

- Review Paper

- Open access

- Published: 19 January 2022

- Volume 10 , pages 477–491, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Amy Russell 1 ,

- Aideen Scriney 1 &

- Sinéad Smyth 1

18k Accesses

8 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Educator attitudes towards inclusive education impact its success. Attitudes differ depending on the SEN cohort, and so the current systematic review is the first to focus solely on students with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Seven databases searched yielded 13 relevant articles. The majority reported positive educator attitudes towards ASD inclusion but with considerable variety in the measures used. There were mixed findings regarding the impact of training and experience on attitudes but, where measured, higher self-efficacy was related to positive attitudes. In summary, educator ASD inclusion attitudes are generally positive but we highlight the need to move towards more homogeneous attitudinal measures. Further research is needed to aggregate data on attitudes towards SEN cohorts other than those with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evidence-Based Practices for Children, Youth, and Young Adults with Autism: Third Generation Review

The justification for inclusive education in Australia

Is Empathy the Key to Effective Teaching? A Systematic Review of Its Association with Teacher-Student Interactions and Student Outcomes

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Until relatively recently, students were frequently separated based on their perceived education needs. Students with special educational needs (SEN) were often educated in special education settings while their remaining peers were educated in what are often termed mainstream settings (Armstrong et al., 2011 ). Interest in wider issues of social inclusion, however, has led to consideration of how education may play a role in promoting social cohesion. As such, educational inclusion has become a central focus in many countries during the last decade (Qvortrup & Qvortrup, 2018 ). In educational contexts, inclusion is a teaching philosophy in which students with special educational needs (SEN) are actively engaged with their typically developing peers (Voltz et al., 2001 ). In practice, inclusion is considered ‘the continuing process of increasing the presence, participation and achievements of all children and young people’ (Ainscow, 2005 ). It is important to note that such definitions go beyond the simple placement of students with SEN in mainstream classrooms, as opposed to in specific specialised settings. Such a conceptualisation would reduce ‘inclusion’ to an issue of admission or placement and ignores the more complex dynamic side of inclusion as an effort to promote participation rather than simple placement with no reference to support and practices.

Under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ( 1989 ), every child has a right to education free from discrimination. Therefore, inclusive education is considered an important human rights issue (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009 ). The United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2017 ) guidelines state that inclusion and equity should be acknowledged as principles for guiding educational policies and practices. UNESCO ( 2009 ) argues that inclusion benefits all learners as it focuses on responding to diverse needs and promotes a fairer society. Despite this, the practicality of ‘inclusive education’ still appears to be problematic in the eyes of some educators (Ainscow & Sandill, 2010 ; Allan, 2014 ). Although there has been a push by policymakers for individuals with SEN to be included in mainstream classrooms, there has been a lack of appropriate support for staff and students (Costello & Boyle, 2013 ). According to Mitchell ( 2014 ), ‘good teaching’ is systematic, explicit and intensive applications of effective teacher strategies. Such strategies should be appropriate to all learners even if they have to be adapted towards their specific educational needs (Norwich, 2003 ; Norwich & Lewis, 2001 ). Empirical studies show that pupils with SEN benefit from ‘good teaching’, even if it is not in a dedicated environment (Mitchell, 2014 ). A good quality education is paramount but a good quality inclusive education is optimal. If inclusion is being implemented internationally, it is important to determine if it works for all cohorts, and if it does not, we need to determine why not.

Educators’ beliefs are used as personal guidelines for defining and understanding educational contexts and roles (Zheng, 2009 ). These beliefs are resilient to rational arguments and scientific proofs which contradict them (UNESCO, 2002 ). Educators play a crucial role in the implementation of inclusive education (Ainscow, 2007 ; Rose & Howley, 2007 ) and their attitudes towards inclusion are vital for success (Loreman et al., 2011 ). However, inclusive education is suggested to be one of the most challenging issues for educators (Atta et al., 2009 ). The American Psychological Association ( 2021 ) defines an attitude as ‘a relatively enduring and general evaluation of an object, person, group, issue or concept on a dimension ranging from negative to positive’. For the purpose of this review, attitude refers to how the educator evaluates the inclusion of the student or SEN in question. Positive attitudes of educators have been related to successful inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream educational institutions (Roberts et al., 2008 ). Educators’ attitudes influence their willingness to accommodate and persist with difficult students and their beliefs about students’ abilities to learn (Stauble, 2009 ). A seminal research study on the impact of teacher expectation on student achievement was conducted by Rosenthal and Jacobson ( 1968 ). They found when teachers were told that some students (picked at random) did poorly on intelligence tests, when these students were revisited, their progress was significantly lower than their peers. This is called the ‘Pygmalion Effect’. It is the idea that the expectations of leaders (in this case, teachers) can influence the progress of the subordinate (the student). This is mainly because teachers put more effort into the students they expect to do well. Therefore, if educators do not believe that students with SEN will do well, they will not put effort into teaching them, and thus, these students will perform poorly.

Research has suggested that educators’ attitudes towards inclusion differ according to disability type. Specifically, educators have more positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with physical or mild learning disabilities compared to those with emotional disorders, cognitive impairments or behavioural issues (Cumming, 2011 ; De Boer et al., 2011 ; Rae et al., 2010 ). It, therefore, appears to be crucial to look at educator attitudes towards different SEN cohorts separately. However, to date, no researchers have attempted to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators on the inclusion of subsets of students with SEN. By assessing attitudes towards SEN in general, we may miss out on nuanced data about attitudes towards the inclusion of specific student groups.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) comprises a range of neurodevelopmental disorders which are characterised by social impairments, communication difficulties and repetitive and restrictive patterns of behaviours (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). As the ‘spectrum’ title suggests, individuals with ASD range in their social, communicative and intellectual abilities (Campisi et al., 2018 ). ASD affects about 1–2% of children worldwide (Elsabbagh et al., 2012 ) and the rate of diagnoses has increased dramatically over the last thirty years (Blaxill, 2004 ; Newschaffer et al., 2007 ). Individuals with ASD are also prone to having comorbid mental health disorders (van Steensel et al., 2011 ; Williams & Roberts, 2018 ). Many experience hyperactivity, attention deficits, executive function, social and communication deficits as well as self-injurious and stereotypic behaviours and emotional instability (Cappadocia et al., 2012 ). It is common for students with ASD to underachieve relative to their cognitive ability (Ashburner et al., 2010 ). The difficulties associated with ASD may lead to challenges in mainstream environments for these students (van Roekel et al., 2010 ), which may impact educators’ attitudes about the appropriateness of this environment for them. Although many individuals with ASD have significant deficits in functioning, many children diagnosed with ASD are highly functioning. Students with ASD are more likely to be excluded from school than most other groups of learners (Barnard, 2000 ; Department for Education & Skills, 2006 ; National Autistic Society, 2003 ). This may be because teaching students with ASD presents significant instructional challenges for educators which may lower their self-efficacy for working with these students (Anglim et al., 2018 ; Klassen et al., 2011 ; Rodden et al., 2018; Ruble et al., 2013 ). Two-thirds of teachers reported lacking confidence and being apprehensive about teaching a student with ASD (Anglim et al., 2018 ). Pupils with ASD are sometimes viewed as more difficult to include than other learners with SEN (House of Commons Education & Skills Committee, 2006 ). Teachers report experiencing tension when dealing with the difficulties these students have in social and emotional understanding (Emam & Farrell, 2009 ) and regard teaching students with ASD as particularly challenging (Simpson et al., 2003 ). As prevalence rates of ASD are so high in school settings and the impairments experienced can impact the classroom in different ways depending on the severity of behaviours displayed (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ), it is important to assess the attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD specifically.

Educators engaging successfully with students with ASD must have an understanding of the social, cognitive and behavioural characteristics of the population (Simpson, 2004 ). Every student with ASD has unique strengths and weaknesses, and therefore, teaching strategies may be successful for some and not for others (Morrier et al., 2011 ). Educators often do not possess relevant knowledge to implement student-focused evidence-based practice (Freeman et al., 2014 ; Morrier et al., 2011 ; Paynter et al., 2017 ). Mainstream teachers report inadequate preparation and lack of ASD-specific training (Busby et al., 2012 ) as a reason for their poor attitudes towards inclusion of these students. Training can improve the self-efficacy of educators (Benoit, 2013 ) and relationships with students with ASD (Blatchford et al., 2009 ), reducing levels of occupational stress (Baghdadli et al., 2010 ). Leach and Duffy ( 2009 ) suggest that teaching pupils with ASD requires specific approaches that mainstream teachers may not be familiar with. Thus, training in the area might remedy this.

There are other perceived needs for successful inclusion. Both new and experienced teachers indicate that their greatest concern regarding inclusive education is inadequate resources and lack of staff (Forlin & Chambers, 2011 ; Round et al., 2016 ). As every child with ASD has unique needs, lack of resources is often cited by teachers to explain their reservations about inclusion of these learners (Busby et al., 2012 ; Ruel et al., 2015 ). Assessing the attitudes of educators and the factors influencing these will allow for the specific needs identified to be addressed and improve attitudes, thus enhancing inclusive education.

Review Purpose

Inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream education is recognised as a human right (Ruijs & Peetsma, 2009 ) and is thought to have benefits for all students (UNESCO, 2009 ). It has been found that positive attitudes of educators facilitate successful inclusion (Roberts et al., 2008 ), and importantly, that these attitudes seem to be dependent on disability type, with those with behavioural, social and emotional difficulties usually being least accepted (Khochen & Radford, 2012 ). ASD proves particularly difficult for inclusion because each student has unique abilities and deficits in these domains (Anglim et al., 2018 ). To date, systematic reviews have focused on SEN in general, rather than on attitudes towards specific SEN cohorts. Therefore, results may be overgeneralized. Aggregating data on educators’ attitudes towards ASD inclusion specifically could greatly assist in understanding the implementation of inclusive educational practices for children with ASD. The aim of the current review was to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream educational settings and to examine the factors which influence these attitudes. A review of this nature can help to draw attention to the importance of seeking out nuanced attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of different subsets of SEN to gain a deeper understanding of inclusive education practices.

Search Strategy

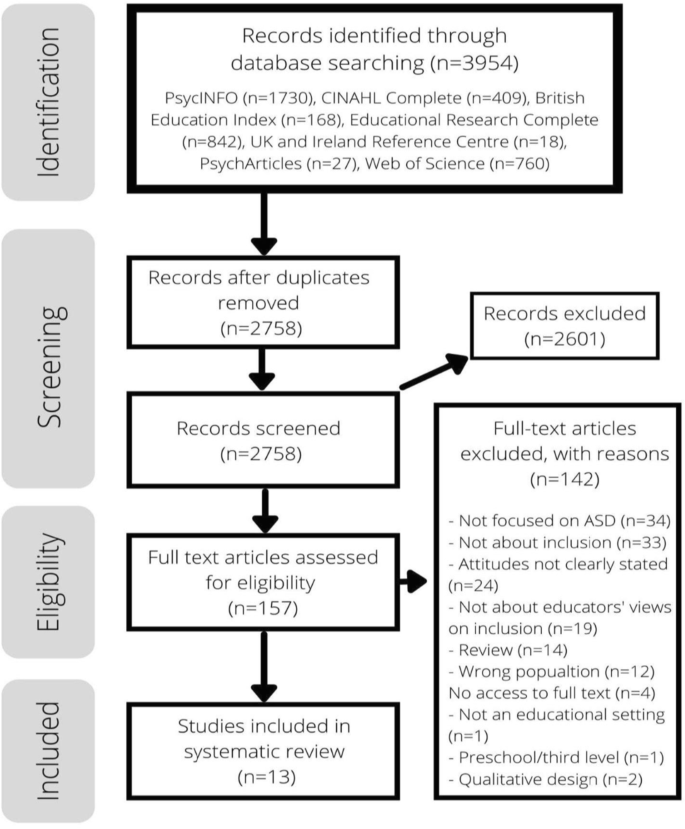

A systematic search of the literature was conducted across seven databases: PsycINFO, CINAHL Complete, British Education Index, Education Research Complete, UK and Ireland Reference Centre, PsycArticles and Web of Science. The searches were conducted on the 5th of March 2021 (Web of Science search run and added 19th of March, 2021). The key search terms were as follows: ((Inclu* OR integrat* OR ‘inclusive education’) AND (Attitude* OR opinion* OR perspective* OR perception*) AND (Education OR mainstream OR school*) AND (ASD or autism spectrum disorder OR autism spectrum OR autism OR autistic OR Asperger*)).

Eligibility Criteria

To design the inclusion criteria for this review, the PICOSS (participants, intervention, comparison, outcomes, study design and setting) was used. It has been adopted by Cochrane and other systematic review organisations (Schardt et al., 2007 ). The inclusion criteria have been summarised in Table 1 . Studies were included in the final analysis if they (1) investigated educator attitudes regarding the educational inclusion of school aged children and adolescents diagnosed with ASD and (2) the participants were current educators. Studies were not included if (1) they were a review of previous studies, (2) they referred to students in settings other than primary or secondary education (e.g. preschool or third level education), (3) participants were not educators or were not currently working (including retired educators or pre-service educators), (4) attitudes were not clearly stated, (5) qualitative only studies and (6) any studies that only focused on attitudes towards inclusion of students with SEN but which did not allow for extraction of attitudes towards students with ASD specifically. The majority of the included studies refer to ‘autism’ or ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder’ but one study refers to ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ (Agyapong et al., 2010 ). In 2013, Asperger’s syndrome became recognised under the umbrella of ‘Autism Spectrum Disorders’ under the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ).

Details of Methods

In order to minimise bias, the review was conducted with a team of two reviewers and a supervisor. Results from each database were exported to ‘Zotero’ reference manager (Corporation for Digital Scholarship, 2021 ), where duplicates were removed before uploading to Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, 2021 ). Covidence, a web-based software, was used throughout the remainder of the review. Each reviewer had access and independently screened the title and abstracts of the retrieved studies. The two reviewers then met to discuss the conflicts which arose during title and abstract screening and a consensus was reached. At the full-text screening phase, if the full text of a study was not available, the author was contacted and asked to provide it. The reviewers again independently screened the texts at this stage and met to discuss conflicts. The first reviewer conducted data extraction on all papers and the second reviewer conducted data extraction on 30% of the included studies. There was full agreement between the reviewers on the data extraction. Quality assessment was conducted by both reviewers and they again met to reach a consensus on the scores for each study.

Data Extraction

The first reviewer extracted data into a pre-prepared excel sheet for the papers chosen at full-text screening. The components extracted from each study were as follows: (1) name of study; (2) authors; (3) year of publication; (4) brief note on the study design; (5) sample size; (6) participant details (gender, mean age, occupation); (7) measures, means and standard deviations of outcome measures; (8) factors mentioned which influence educator attitudes.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the studies included in the review was assessed using the Quantitative Quality Appraisal Tool (adapted from Dunne et al., 2017 and Jefferies et al., 2012 ). The Quantitative Quality Appraisal tool asks 12 questions of the paper being assessed, with four possible answers: yes (score of 2 points), partial (score of 1 point), no (score of 0) and do not know (score of 0). Studies scoring 17–24 were considered good quality, 9–16 acceptable quality and 0–8 low quality. A summary of the quality appraisal ratings is included in the table of study characteristics (Table 2 ).

Synthesis of Results

A narrative synthesis was chosen to analyse the data, due to the heterogeneity of the measures. This type of synthesis is useful for explaining the ‘why’ behind phenomena. The data extracted from the studies was organised into themes. These themes are discussed later in the ‘ Results ’ section.

Following database searches, 3954 articles were identified for possible inclusion, as outlined in Fig. 1 . Of these, 1196 articles were duplicates and were subsequently excluded. Upon initial screening of the abstracts of the remaining 2758 articles, it was determined that 2601 did not meet inclusion/exclusion criteria and 157 articles did. Following full-text review, of the 157 articles, 13 fulfilled the necessary inclusion/exclusion criteria and were included in the review. Summary characteristics of these studies are provided in Table 2 .

PRISMA diagram for studies considered for the systematic review

Study Characteristics

A total of 3247 educators participated across the 13 identified studies. The sample sizes ranged from 72 to 863 and included general education (both primary and post primary), special education and physical education teachers, principals and instructors. Five studies did not present data on gender (Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Horrocks et al., 2008 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Salceanu, 2020 ; Su et al., 2020 ), but of the remaining studies, 1756 participants were female, and 326 were male. Two studies reported mean ages of 46 and 38.8 (Beamer & Yun, 2014 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Six studies reported their ages in categories, all participants were adults, with the youngest category being reported as ‘20–30’ and the oldest being ‘50 + ’ (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; Garrad et al., 2019 ; Lu et al., 2020 ; Salceau, 2020). The other studies did not report ages of their participants. Study locations varied from the USA ( n = 3) to Ireland ( n = 2), Romania ( n = 1), Jordan ( n = 1), Iceland ( n = 1), Greece ( n = 1), Australia ( n = 1), China ( n = 2) and Scotland ( n = 1). All studies were cross-sectional in nature.

Attitude Measures

There was considerable diversity in the scales used to measure the attitudes of participants, with six established scales in total and only one scale (the Autism Attitude Scale for Teachers; Olley et al., 1981 ) used more than once. Other studies used the Teacher’s Beliefs and Intentions towards Teaching Students with Disabilities (Jeong & Block, 2011 ), Principal’s Perspective Questionnaire (Horrocks, 2005 ), Impact of Inclusion Questionnaire (Hastings & Oakford, 2003 ), Inclusion of Children with Special Needs in Public Schools Questionnaire (Chitu et al., 2016) and Placement and Services Survey (Segall & Campbell, 2007 ). An additional six studies created their own surveys rather than using an existing measure (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Bjornsson et al., 2014; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Su et al., 2020 ). These surveys addressed the opinions of educators about the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education.

Attitudes of Educators: Educational Placement

Not surprisingly, given the heterogeneity of measures, the attitudes of educators were presented in a number of different ways. This made synthesis of results particularly difficult. Eight studies equated the opinions of their participants on the educational placement of students with ASD as representing their attitudes towards the inclusion of these students. However, the phrasing of the reported attitudes showed considerable variation. Abu-Hamour and Muhaidat ( 2013 ) asked participants if students with ASD should have the right to attend mainstream. Agyapong and colleagues (2010) asked if these students should be taught in mainstream classrooms. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) inquired whether their participants would accept these students in their classroom. Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) asked which cohort of SEN is most appropriate for mainstream education. Salceanu ( 2020 ) asked participants what they thought the best solution was for the educational placement of these students. Su and colleagues (2020) presented the opinions of their participants on whether or not these students could be taught in mainstream classrooms. The final two studies (Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ) showed some uniformity by asking participants where they thought was most appropriate for these students to be taught. These measures all purport to determine the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream so, therefore, they have been synthesised as such, but there are subtle differences between them.

In four of the eight studies which equated attitudes towards inclusion with beliefs about appropriate educational placement of autistic students, a large majority of participants showed positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 , 79.3%; Agyapong et al., 2010 , 71.1%; Segall & Campbell, 2001, 66.7%; Su et al., 2020 , 60.9%). Two studies found only a moderately positive attitude towards the inclusion of these students (Cassimos et al., 2015 , 56.1%, Salceanu, 2020 , 56.7%). The final two studies found their participants to have negative attitudes (Bjornsson et al., 2019 , 50.1%, McGregor & Campbell, 2001 , 68.7%).

Attitudes of Educators: Attitude Scales

The alternative approach to measuring attitudes towards inclusion was to use attitude scales and presenting the mean results of these. Five studies followed this model. These attitude scales represent a more affective measure of attitudes, gauging beliefs about inclusion and the perceived impacts of the inclusion of these students. Two of these studies found their participants to have a significantly positive attitude towards inclusion (Beamer & Yun, 2014 , 6.65 out of 7; Garrad et al., 2019 , 4.11 out of 5). Two other studies found moderately positive attitudes of their participants (Horrocks et al., 2008 , 3.76 out of 5; Lu et al., 2020 . 3.20 out of 5). One study found largely negative or neutral attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ; 54% with negative attitude, 36% neutral). Therefore, most studies who measured using attitude scales reported positive mean attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education. The majority of the included studies found positive attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education (c.f. Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). There were no consistent differences in attitudes across educator type, country of publication or sample size. It is important to note, however, that the measures of attitudes were heterogeneous, making synthesis difficult and perhaps masking differences across studies.

Factors Influencing Attitudes

There were a number of factors examined within the studies which influenced the attitudes of participants. The common themes that emerged were experience and training, personal factors, perceived needs and student skills.

Experience and Training

The impact of experience on the attitudes of educators was measured in seven of the 15 studies. Three studies found that teaching experience did not influence attitudes (Garrad et al., 2019 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Three studies found that more experience led to more positive attitudes towards integration into mainstream education (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). Another two studies found the opposite that experience led to more negative attitudes (Horrocks et al., 2008 ; Su et al., 2020 ). Therefore, considerable variation exists surrounding whether or not experience has an impact on the attitudes of educators’ and the direction of this impact.

Training in SEN and ASD was another factor which was assessed for its relationship to inclusion attitudes. Participants in five studies stated that they lacked specific training on ASD (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Salceanu, 2020 ). Two studies found training in SEN in general or ASD in particular did not influence the inclusion attitudes of their participants (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). Two studies found that the inclusion of ASD was more likely to be supported by educators who had training in the area (Agyapong et al., 2010 ; Cassimos et al., 2015 ). Garrad and colleagues (2019) found that there was a small positive relationship between attitudes and ASD-specific training but that it did not predict attitudes. Again, there was mixed evidence on the impact of training on educators’ attitudes with two studies stating there is no impact and three finding a positive relationship between the two.

There was also variability in the types of educators included in the studies. Five studies included ‘special needs educators’. In these studies, special needs educators were classified as those who were working in specialised placements with students with SEN. For example, Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) included ‘special education teachers who worked in special education centres that provided focused teaching for low-functioning students’ (p.34). Three of these studies found positive attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Salceanu, 2020 ; Su et al., 2020 ) and the other two found negative attitudes (Bjornsson et al., 2019 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ) highlighted the difference between special educators and mainstream educators with experience working with students with SEN and those without. Forty-seven percent of specialist staff strongly agreed or agreed that full integration should be aimed for where possible, 47% of experienced mainstream staff agreed but only 27% of inexperienced mainstream staff thought full inclusion should happen where possible. Four percent of specialised staff strongly disagree or disagreed with full integration where possible, compared with 20% of experienced mainstream staff and 31% of inexperienced mainstream staff. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) also found that individuals with previous training or experience of working with students with ASD were more willing to include these learners in their classroom (73.5% of those with training and 81.3% of those with experience, compared to 46.2% and 46.3% of those with no training or experience, respectively).

Personal Factors

Of the personal factors investigated, the most common was the impact of self-efficacy on the attitude of educators which was examined in three studies. Beamer and Yun ( 2014 ) and Lu and colleagues (2020) found a significant, positive correlation between self-efficacy and inclusion attitudes of their participants (0.59 and 0.34, respectively). Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found that self-efficacy was a predictor of placement decisions. Beamer and Yun ( 2014 ) found very small correlations between undergraduate training in adapted physical education (0.05) and graduate training in adapted physical education (0.06) and self-efficacy. However, Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found a moderate correlation between self-efficacy and training (0.5). Another personal factor which was examined in the included studies was knowledge of ASD. Two studies investigated the effect of knowledge on attitudes, with mixed findings. One study found a significant positive relationship between knowledge and attitudes (Lu et al., 2020 ). However, another found that knowledge of ASD did not predict placement decisions (Segall & Campbell, 2014 ).

In addition to self-efficacy and knowledge, researchers also examined the relationship between factors such as gender, subject taught, subjective norms and type of educational institution. The two studies which assessed gender found no significant relationship with inclusion attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ). However, these studies did not have even spreads of gender, with female participants far out-weighing males. Those from ages 20 to 30 were found to be more accepting of the inclusion of students with ASD (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ). It was also found that educators who focused on teaching academic subjects had significantly lower inclusion attitude scores (Su et al., 2020 ). Subjective norms of teachers (i.e., taking into account what their colleagues think) were found to be significant predictors of placement opinions (Segall & Campbell, 2014 ). Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) found that the educators’ perception of the disruptive behaviours did not influence their placement decisions. The influence of the type of institution the educator currently works in was found to have an influence on attitudes with educators in private schools and centres being found to have more positive attitudes (Abu-Hamour & Muhaidat, 2013 ).

Perceived Needs

There were a number of perceived needs for successful inclusion cited by participants in the included studies. Some educators felt that they lacked the capability and understanding to deal with these students’ needs (Cassimos et al., 2015 ; Salceanu, 2020 ). McGregor and Campbell’s ( 2001 ) participants believed that integration was dependent on educators’ attitude while participants in Salceanu’s ( 2020 ) study felt that differential assessment strategies and curriculum adaptation were necessary for inclusion. The need for closer collaboration between schools and psychiatric services was also mentioned in one study (Agyapong et al., 2010 ). Beyond these staff related factors, resources and funding were the main needs cited in four studies (Agyapong et al., 2010 , 77.3% of participants; Cassimos et al., 2015 , 70.2%; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 , 66%; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ). Three of these four studies reported that participants felt that they did not have the necessary resources and funding to accommodate a student with ASD (Agyapong et al., 2010 , 77.3% of participants; Cassimos et al., 2015 , 70.2%; Leonard & Smyth, 2020 , 66%). Human resources featured frequently with educational psychologists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists, special needs assistants (Agyapong et al., 2010 ), human resources (Leonard & Smyth, 2020 ) and adequate auxiliary help (McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ) considered to be required for inclusion. Leonard and Smyth ( 2020 ) also mentioned the need for classroom materials. All studies examining resources asked questions in different ways, making a clearer synthesis of the findings difficult.

Student Skills

Two studies reported on participant opinions of student skills which impact on successful inclusion in mainstream school. Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) reported participants’ perception that for inclusion to be successful, students with ASD needed to have certain skills. Cassimos and colleagues (2015), by contrast, reported on their participants’ views of student related factors that were barriers to inclusion. Cross over between the perceived barriers and facilitators between these two studies was in the area of communication and social skills. The specific skills noted by participants in Abu-Harmour and Muhaidat (2013) were ranked in order of importance as independence, imitation, behavioural, play, social, routine, language, pre-academic and academic. Their participants reported these as being necessary in order for students to navigate the social environment, communicate their needs, understand communication from other people and acquire strategies to help them learn with and through their peers. Cassimos and colleagues’ (2015) barriers were once again listed in order of perceived importance and comprised introvertedness, communication problems, obsessive, stereotypical and self-stimulatory behaviour and incomprehensible language of these students. These participants also voiced that vocational training was a better option for learners with ASD (69.7%). It is important to note that these were participant opinions and not evidence-based however, and additional three of the included studies (Horrocks et al., 2008 ; McGregor & Campbell, 2001 ; Segall & Campbell, 2014 ) investigated how the abilities of students with ASD impacted the educator’s attitude about their placement. Horrocks and colleagues (2008) measured the placement decisions of principals based on the description of five different pupils. All of the pupils described presented with a diagnosis of ASD. They found that those students who were described as having good academic performance were more often recommended to have high levels of inclusion by the principals. The participants were also found to be less likely to recommend high levels of inclusion in the students who showed social detachment. Segall and Campbell ( 2014 ) provided their participants with descriptions of a student, Robby. There were six variations of Robby provided—moderate intellectual disability with no label, with label of autism, and with just label of an intellectual disability and average cognitive ability with no label, with label of autism, and with label of Asperger’s syndrome. The study found that the cognitive ability of Robby affected the teachers’ opinions regarding his placement. Participants reported that their own classroom was a less appropriate placement for students with a label of autism versus no label. However, the label of Asperger’s syndrome did not affect placement decisions when compared to the label of autism or no label at all. McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ) asked participants what factors influence successful inclusion. Eighteen percent of specialist staff, 20% of experienced mainstream staff and 16% of inexperienced mainstream staff agreed or strongly agreed that successful inclusion depended on the academic ability of the student. A larger majority of the participants strongly agreed that the student’s degree of autism was a factor influencing successful inclusion. Participants were also asked if ‘able’ children were better educated in mainstream school. The responses were close on this item with 39% of specialist staff, 34% of experienced mainstream staff and 21% of inexperienced mainstream staff agreeing or strongly agreeing. It would appear that the cognitive abilities of the student impacts educators’ attitudes regarding their educational placement.

Potential Bias

All included studies were considered to be of good or acceptable quality according to the quality appraisal tools employed. The key areas in which the studies were downgraded were lack of control groups and not describing their non-responders. However, the use of a control group in studies such as this may not have been appropriate to answer the research questions. The overall risk of bias across the studies was considered to be low. All studies clearly stated their aims and objectives and adhered to them. There was no evidence of selective reporting and sampling bias across the studies.

While previous systematic reviews have explored the literature on educator attitudes towards the inclusion of students with SEN in mainstream education, no known published reviews have examined the inclusion of a specific cohort of students with SEN, those with a diagnosis of ASD. Given the diverse profiles of students with SEN, examining attitudes towards inclusion of students with SEN as a whole group may result in over generalisation and omitting specific attitudinal trends with regard to the inclusion of students with ASD. The aim of the current review was therefore to conduct the first systematic review to aggregate data on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD in mainstream education and the factors which influence these. A search of the literature yielded 13 eligible studies with a total of 3247 participants. These included participants in a number of different education roles and settings. Furthermore, these studies reported huge diversity in the attitudinal measures employed, making a narrative synthesis of the data the most appropriate approach.

Overall, the majority of the included studies reported that educators were in favour of the inclusion of students with ASD. It is interesting to note that attitudes towards inclusion did not vary across educator types. Hernandez et al. ( 2016 ), when examining attitudes towards general SEN inclusion, rather than ASD specifically, found that special education teachers had significantly more positive inclusion attitudes than their general education counterparts. They also found teacher type was a predictor of inclusion attitudes. From the findings of McGregor and Campbell ( 2001 ), it appears that attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD differ depending on the extent of experience with this group of learners. Cassimos and colleagues (2015) similarly reported that previous experience with students with ASD made educators more willing to accept them in their classroom. Perhaps giving experience and training in working with individuals with ASD to mainstream educators will make them more willing to accept these learners in their classroom.

Heterogeneity of Measures

Caution should be taken when considering these findings given that there was a considerable amount of heterogeneity of measures used in the included studies, which made synthesis difficult. Many studies created their own scales and presented their findings in different manners, making comparison challenging. It was not only the variety of measures which made synthesis difficult, but also the way in which attitudes were measured. As previously mentioned, attitudes were gauged using either affective measures or binary (yes/no) questions regarding where these students should be taught. Previous reviews which aimed to synthesise data on the attitudes of educators towards students with SEN also had similar issues. Lautenbach and Heyder’s ( 2019 ) systematic review for example saw a number of distinct measures used, the majority of which were self-constructed. Attitudes towards individuals with SEN, including ASD, are multi-faceted and include the domains of cognition, affect and behaviour (Nowicki & Sandieson, 2002 ). Therefore, comparing data from measures which may not be assessing the same domain may be futile. Antonak and Larrivee ( 1995 ) advised that the use of existing scales which are refined, revised and updated as necessary is preferable to creating new measures. Particular attention should be paid to choosing if attitudes are best estimated using affective measures or using binary placement questions. By reaching a consensus on which attitude scales to use in future research of this nature, more valuable information will be obtained. However, as this is the first review of its type, it would not be expected that an agreed upon measure would be used throughout studies.

The findings of predominantly positive attitudes towards the inclusion of students with ASD is despite known educational challenges for this cohort. Students with ASD are the most likely cohort of learners to be excluded from school (Barnard, 2000 ; Department for Education & Skills, 2006 ; National Autisitic Society, 2003). It has been found that students with ASD present significant instructional challenges for educators (Anglim et al., 2018 ; Klassen et al., 2011 ; Rodden et al., 2019 ; Ruble et al., 2013 ) and are often viewed as difficult to include (House of Commons Education & Skills Committee, 2006 ). Therefore, exploring the factors influencing these attitudes is important. Training in ASD and SEN and educator experience were the factors most assessed in the included studies. The results of the current synthesis found mixed evidence on the impact of training and experience on the attitudes of educators towards the inclusion of students with ASD. Mainstream teachers often report a lack of specific ASD training as a reason for their apprehension to include these pupils (Busby et al., 2012 ).

Training did not clearly relate to more positive educator attitudes; however, self-efficacy of educators was found to have a positive relationship with inclusion attitudes, in the three studies where it was assessed. According to Bandura’s ( 1997 ) social cognitive theory, educator efficacy is concerned with educators’ appraisals of their capabilities to influence student outcomes (Wheatley, 2002 ). If educators believe that they are able to teach students with ASD and produce positive outcomes, they will be more willing to include them. Previously, increased self-efficacy has been linked with training (Benoit, 2013 ). However, two of the included studies which examined self-efficacy found mixed results on the correlations between training and self-efficacy. Interestingly, while a large majority of participants in Segall and Campbell’s ( 2014 ) study were confident in their ability to teach students with ASD (87%), only about one-third of them had ASD-specific training. Further research is needed to assess the impact of training on self-efficacy as self-efficacy can appear to have an impact on educators’ inclusion attitudes.