24/7 writing help on your phone

To install StudyMoose App tap and then “Add to Home Screen”

What life will be in 2050?

Save to my list

Remove from my list

Example 2. E ssay about life in 2050

What life will be in 2050?. (2016, May 31). Retrieved from https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay

"What life will be in 2050?." StudyMoose , 31 May 2016, https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay

StudyMoose. (2016). What life will be in 2050? . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay [Accessed: 6 Sep. 2024]

"What life will be in 2050?." StudyMoose, May 31, 2016. Accessed September 6, 2024. https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay

"What life will be in 2050?," StudyMoose , 31-May-2016. [Online]. Available: https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay. [Accessed: 6-Sep-2024]

StudyMoose. (2016). What life will be in 2050? . [Online]. Available at: https://studymoose.com/what-life-will-be-in-2050-essay [Accessed: 6-Sep-2024]

- IntroductionLooking towards the future 2050 According to Pages: 3 (617 words)

- City Life Vs Country Life Pages: 6 (1613 words)

- Country Life Is Better Than City Life Pages: 7 (1984 words)

- A Life Lesson in Keller’s The Story of My Life: Empowering Self-Efficacy Pages: 6 (1531 words)

- Debating the Relationship Between Art and Life: Does Art Imitate Life? Pages: 5 (1426 words)

- My Life Experience How It Changed My Life Pages: 6 (1611 words)

- Brecht’s Life of Galileo as an Examination of Key Life Events of a Great Physicist Pages: 7 (1823 words)

- Single Life vs. Married Life: Lifestyle Analysis Pages: 3 (609 words)

- How The University Life in NSU Changed My Life? Pages: 2 (466 words)

- Education Is Not a Preparation for Life; Education Is Life Itself Pages: 2 (504 words)

👋 Hi! I’m your smart assistant Amy!

Don’t know where to start? Type your requirements and I’ll connect you to an academic expert within 3 minutes.

- The Big Think Interview

- Your Brain on Money

- Explore the Library

- The Universe. A History.

- The Progress Issue

- A Brief History Of Quantum Mechanics

- 6 Flaws In Our Understanding Of The Universe

- Michio Kaku

- Neil deGrasse Tyson

- Michelle Thaller

- Steven Pinker

- Ray Kurzweil

- Cornel West

- Helen Fisher

- Smart Skills

- High Culture

- The Present

- Hard Science

- Special Issues

- Starts With A Bang

- Everyday Philosophy

- The Learning Curve

- The Long Game

- Perception Box

- Strange Maps

- Free Newsletters

- Memberships

What Will Life Be Like in 2050?

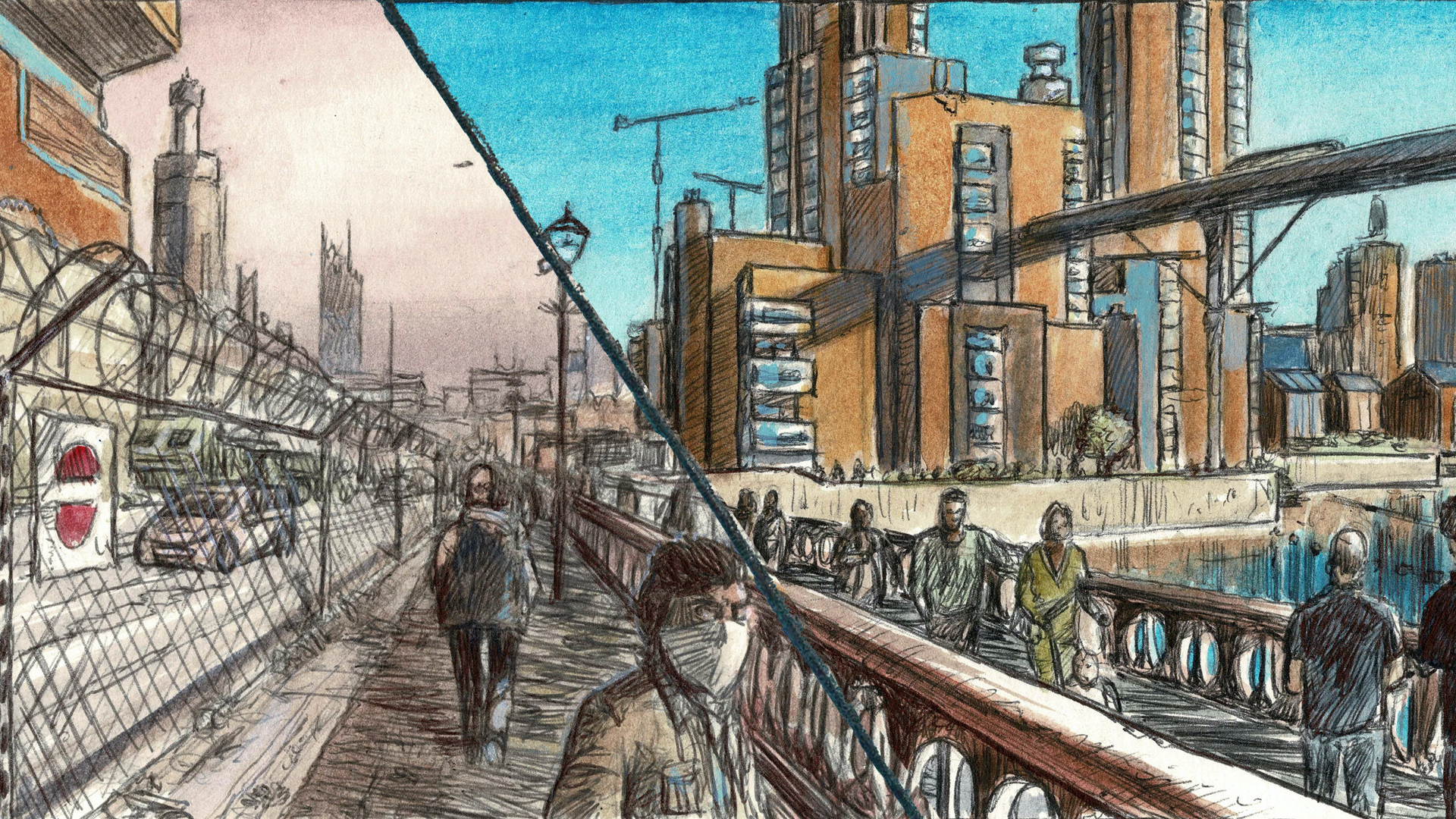

By mid-century there will likely be 9 billion people on the planet, consuming ever more resources and leading ever more technologically complex lives. What will our cities be like? How much will artificial intelligence advance? Will global warming trigger catastrophic changes, or will we be able to engineer our way out of the climate change crisis?

Making predictions is, by nature, a dicey business, but to celebrate the 40th anniversary of Smithsonian magazine Big Think asked top minds from a variety of fields to weigh in on what the future holds 40 years from now. The result is our latest special series, Life in 2050 . Demographic changes in world population and population growth will certainly be dramatic. Rockefeller University mathematical biologist Joel Cohen says it’s likely that by 2050 the majority of the people in the world will live in urban areas, and will have a significantly higher average age than people today . Cities theorist Richard Florida thinks urbanization trends will reinvent the education system of the United States, making our economy less real estate driven and erasing the divisions between home and work.

Large migrations from developing countries like Indonesia, Malaysia, Bangladesh, Mexico, and countries in the Middle East could disrupt western governments and harm the unity of France, Germany, Spain, the Netherlands, Poland, and the United Kingdom under the umbrella of the European Union .

And rapidly advancing technology will continue ever more rapidly. According to Bill Mitchell, the late director of MIT’s Smart Cities research group, cities of the future won’t look like “some sort of science-fiction fantasy” or “Star Trek” but it’s likely that “discreet, unobtrusive” technological advances and information overlays, i.e. virtual reality and augmented reality, will change how we live in significant ways. Self-driving cars will make the roads safer, driving more efficient, and provide faster transports. A larger version of driverless cars—driverless trucks—may make long haul drivers obsolete.

Charles Ebinger, Director of the Energy Security Initiative at the Brookings Institution also thinks that by 2050 we will also have a so-called “smart grid” where all of our appliances are linked directly to energy distribution systems , allowing for real-time pricing based on supply and demand. Such a technology would greatly benefit energy hungry nations like China and India, while potentially harming fossil fuel energy producers like Canada and .

Meanwhile, the Internet will continue to radically transform media , destroying the traditional model of what a news organization is, says author and former New York Times Public Editor Daniel Okrent, who believes the most common kinds of news organizations in the future will be “individuals and small alliances of individuals” reporting and publishing on niche topics.

But what will all this new technology mean? Viktor Mayer-Schönberger, the director of the Information & Innovation Policy Research Center at the National University of Singapore, hopes that advances in technology will make us more empowered, motivated and active , rather than mindless consumers of information and entertainment. And NYU interactive telecommunications professor Clay Shirky worries that technological threats could endanger much of the openness that we now enjoy online , perhaps turning otherwise free-information countries into mirrors of closed states like China and Turkey.

Some long view predictions are downright dire. Environmentalist Bill McKibben says that if we don’t make major strides in combating global warming, it’s likely we could see out-of-control rises in sea levels — particularly dangerous in island nations like the Philippines — enormous crop shortfalls, and wars over increasingly scarce freshwater resource s. But information technology may yield some optimism for our planet, says oceanographer Sylvia Earle, who thinks that services like Google Earth have the potential to turn everyday people into ocean conservationists .

In the financial world, things will be very different indeed, according to MIT professor Simon Johnson, who thinks many of the financial products being sold today, like over-the-counter derivatives, will be illegal —judged, accurately, by regulators to not be in the best interests of consumers and failing to meet their basic needs. If economic growth rates remain steady, however, it may present a challenge to regulators.

We will live longer and remain healthier. Patricia Bloom, an associate professor in the geriatrics department of Mt. Sinai Hospital, says we may not routinely live to be 120, but it’s possible that we will be able to extend wellness and shorten decline and disability for people as they age . AIDS research pioneer David Ho says the HIV/AIDS epidemic will still be with us , but we will know a lot more about the virus than we do today—and therapies will be much more effective. Meanwhile, Jay Parkinson, the co-founder of Hello Health, says the health care industry has a “huge opportunity” to change the way it communicates with patients by conceiving of individual health in relation to happiness.

In terms of how we will eat, green markets founder and “real food” proponent Nina Planck is optimistic that there will be more small slaughterhouses, more small creameries, and more regional food operations—and we’ll be healthier as a result . New York Times cooking columnist Mark Bittman, similarly, thinks that people will eat fewer processed foods , and eat foods grown closer to where they live. And Anson Mills farmer Glenn Roberts thinks that more people will clue into the “ethical responsibility” to grow and preserve land-raised farm systems . And what will our culture be like? We may not get rid of racism in America entirely in the next 40 years, but NAACP President Benjamin Jealous predicts that in the coming decades the issue of race will become “much less significant,” even as the issue of class may rise in importance. Father James Martin, a Jesuit priest, says it’s even likely that we’ll see a black pope , reversing centuries of Euro-centrism in favor of Catholics in Africa. Nigeria is one such country with a large Catholic population. Meanwhile, prisons expert Robert Perkinson says he thinks there will be fewer Americans in prison in 2050 , because we will realize that the current high levels of incarceration are out of sync with our history and values. Historian and social scientist Joan Wallach Scott worries, however, that unless the countries of Europe figure out how to accommodate Muslim immigrant populations, t here will be more riots, and increasing divisions along economic, religious and ethnic lines , such instability could have knock on effects in countries ranging from Egypt and Iran to Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. —

We want to hear from you! Let us know what you think about our website.

interstitialRedirectModalTitle

interstitialRedirectModalMessage

- Show search

Magazine Articles

A More Sustainable Path to 2050

Science shows us a clear path to 2050 in which both nature and 10 billion people can thrive together.

August 30, 2019

Written for The Nature Conservancy Magazine Fall 2019 issue by Heather Tallis, former lead scientist for TNC.

A few years ago The Nature Conservancy began a process of reassessing its vision and goals for prioritizing its work around the globe. The resulting statement called for a world where “nature and people thrive, and people act to conserve nature for its own sake and its ability to fulfill and enrich our lives.”

That sounds like a sweet future, but if you’re a scientist, like I am, you immediately start to wonder what that statement means in a practical sense. Could we actually get there? Is it even possible for people and nature to thrive together?

Our leaders had the same question. In fact, when the vision statement was first presented at a board meeting, our president leaned over and asked me if we had the science to support it.

“No,” I said. “But we can try to figure it out.”

There is a way to sustain nature and 10 billion people.

Explore the path to a better world. Just 3 changes yield an entirely different future.

Ultimately, I assembled a collaborative team of researchers to take a hard look at whether it really is possible to do better for both people and nature: Can we have a future where people get the food, energy and economic growth they need without sacrificing more nature?

Modeling the Status Quo: What the World Will Look Like in 2050

Working with peers at the University of Minnesota and 11 other universities, think tanks and nonprofits, we started by looking into what experts predict the world will look like in 2050 in terms of population growth and economic expansion. The most credible projections estimate that human population will increase from about 7 billion people today to 9.7 billion by 2050, and the global economy will be three times as large as it is today.

Our next step was to create a set of mathematical models analyzing how that growth will influence demand for food, energy and water.

We first asked how nature will be doing in 2050 if we just keep doing things the way we’ve been doing them. To answer this, we assumed that expanding croplands and pastures would be carved out of natural lands, the way they are today. And we didn’t put any new restrictions on the burning of fossil fuels. We called this the “business as usual” scenario. It’s the path we’re on today. On this current path, most of the world’s energy—about 76%—will come from burning fossil fuels. This will push the Earth’s average temperature up by about 5.8 degrees Fahrenheit, driving more severe weather, droughts, fires and other destructive patterns. That dirty energy also will expose half of the global population to dangerous levels of air pollution.

Dig into the Research

Explore the models behind the two paths to 2050 and download the published findings.

We first asked how nature will be doing in 2050 if we just keep doing things the way we’ve been doing them.

Meanwhile, the total amount of cropland will increase by about the size of the state of Colorado. Farms will also suffer from increasing water stress—meaning, simply, there won’t be enough water to easily supply agricultural needs and meet the water requirements of nearby cities, towns and wildlife.

In this business-as-usual scenario, fishing worldwide is left to its own devices and there are no additional measures in place to protect nature beyond what we have today. As a result, annual fish catches decline by 11% as fisheries are pushed to the brink by unsustainable practices. On land, we end up losing 257 million more hectares (about 10 Colorados) of our native forests and grasslands. Freshwater systems suffer, too, as droughts and water consumption, especially for agriculture, increase.

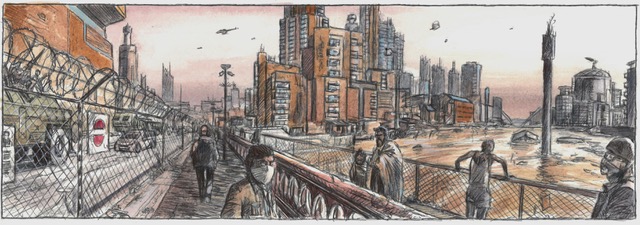

Overall, the 2050 predicted by this business-as-usual model is a world of scarcity, where neither nature nor people are thriving. The future is pretty grim under this scenario—it’s certainly not a world that any of us would want to live in.

We wanted to know, “does it really have to be this way?”

Modeling a More Sustainable 2050

Next, we used our model to test whether predicted growth by 2050 really requires such an outcome. In this version of the future, we allowed the global economy and the population to grow in exactly the same manner, but we adjusted variables to include more sustainability measures.

The 2050 predicted by the business-as-usual model is a world of scarcity, where neither nature nor people are thriving. The future is pretty grim under this scenario—it’s certainly not a world that any of us would want to live in.

We didn’t go crazy with the sustainability scenario. We didn’t assume that everyone was going to become a vegan or start driving hydrogen cell cars tomorrow. Instead, the model allowed people to continue doing the basic things we’re doing today, but to do them a little differently and to adopt some green technologies that already exist a little bit faster.

In this sustainable future, we limited global warming to 2.9 degrees Fahrenheit, which would force societies to reduce fossil fuel consumption to just 13% of total energy production. That means quickly adopting clean energy, which will increase the amount of land needed for wind, solar and other renewable energy development. But many of the new wind and solar plants can be built on land that has already been developed or degraded, such as rooftops and abandoned farm fields. This will help reduce the pressure to develop new energy sources in natural areas.

We also plotted out some changes in how food is produced. We assumed each country would still grow the same basic suite of crops, but to conserve water, fertilizer and land, we assumed that those crops would be planted in the growing regions where they are most suited. For example, in the United States we wouldn’t grow as much cotton in Arizona’s deserts or plant thirsty alfalfa in the driest parts of California’s San Joaquin Valley. We also assumed that successful fishery policies in use in some places today could be implemented all over the world.

Under this sustainability scenario, we required that countries meet the target of protecting 17% of each ecoregion, as set by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Only about half that much is likely to be protected under the business-as-usual scenario, so this is a direct win for nature.

What 2050 Could Look Like

The difference in this path to 2050 was striking. The number of additional people who will be exposed to dangerous levels of air pollution declines to just 7% of the planet’s population, or 656 million, compared with half the global population, or 4.85 billion people, in our business-as-usual scenario. Air pollution is already one of the top killers globally, so reducing this health risk is a big deal. Limiting climate change also reduces water scarcity and the frequency of destructive storms and wildfires, while staving off the projected widespread loss of plant and animal species (including my son’s favorite animal, the pika, that’s already losing its mountain habitat because of climate change).

In the sustainability scenario we still produce enough food for humanity, but we need less land and water to do it. So the total amount of land under agricultural production actually decreases by seven times the area of Colorado, and the number of cropland acres located in water-stressed basins declines by 30% compared with business as usual. Finally, we see a 26% increase in fish landings compared to 2010, once all fisheries are properly managed.

Although the land needed for wind and solar installations does grow substantially, we still keep over half of nearly all the world’s habitat types intact, and despite growth in cities, food production and energy needs, we end up with much more of the Earth’s surface left for nature than we would under the business-as-usual scenario.

Our modeling research let us answer our question. Yes, a world where people and nature thrive is entirely possible. But it’s not inevitable. Reaching this sustainable future will take hard work—and we need to get started immediately.

3 Sustainable Changes To Make Now

That’s where organizations like TNC come in. The Conservancy is working on strategies with governments and businesses to adopt sustainable measures, providing near- and long-term benefits to society as a whole. Our research shows there’s at least one path to a more sustainable world in 2050, and that major advances can be made if all parts of society focus their efforts on three changes.

First, we need to ramp up clean energy and site it on lands that have already been developed or degraded. In the Mojave Desert, for instance, TNC has identified some 1.4 million acres of former ranchlands, mines and other degraded areas that would be ideal for solar development. We need to do much more to remove the policy and economic barriers that still make a transition to clean energy hard. Technology is no longer the major limiting factor. We are.

The most critical action each of us can take is to support global leaders who have a plan for stopping climate change in our lifetimes.

Second, we need to grow more food using less land and water. One way to do that is by raising crops in places that are best suited for them. The Conservancy has been piloting this, too. In Arizona, TNC partnered with local farmers in the Verde River Valley to help them switch from growing thirsty crops like alfalfa and corn in the heat of the summer to growing malt barley, which can be harvested earlier in the season with less draw on precious water supplies. This is not a revolutionary change—the same farmers are still growing crops on the same land—but it can have a revolutionary impact.

Finally, we need to end overfishing. The policy tools to do so have been available for many years. What we must do now is get creative about how we get those policies adopted and enforced. One example I have been impressed by is our work in Mexico, where TNC is involved in looking at the root causes of what’s limiting good fishing behavior. The answer is unexpected: social security debt that many fishers have accrued by being off the books for many years. The Conservancy is exploring an ambitious partnership and a novel financial mechanism that could forgive this debt and persuade more fishers to report their catch and adopt sustainability measures.

The Most Important Change Now: Clean Energy

These are just a few examples from North America. There are many more from around the world. To achieve a more sustainable future, governments, industry and civic institutions everywhere will have to make substantial changes—and the most important one right now is to make a big investment in clean energy over the next 10 years. That’s a short timeline, but not an impossible one. I don’t like what I’m seeing yet, but I’m hopeful. It took the United States just a decade to reach the moon, once the country put its mind to the goal. And solar energy is already cheaper (nearly half the price per megawatt) than coal, and outpacing it for new capacity creation—something no one predicted would happen this fast.

We need to do much more to remove the policy and economic barriers that still make a transition to clean energy hard. Technology is no longer the major limiting factor. We are.

How will we get there? By far the most critical action each of us can take is to support global leaders who have a plan for stopping climate change in our lifetimes. Climate may not feel like the most pressing issue at times—what with the economy, health care, education and other issues taking up headlines. But the science is clear: We’ve got 10 years to get our emissions under control. That’s it.

We’ve already begun to see the impacts of climate change as more communities face a big uptick in the severity and frequency of droughts, floods, wildfires, hurricanes and other disasters. Much worse is on the way if we don’t make the needed changes. It’s been easy for most of us to sit back and expect that climate change will only affect someone else, far away. But that’s what the people in Arkansas, California, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, New York, Oklahoma, Oregon, Texas, Washington, the Dominican Republic, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Mexico, the United Kingdom, the Philippines, India and Mozambique thought. Every one of these places—and many more—have seen one of the worst disasters on its historic record in the past 10 years.

There are so many paths we could take to 2050. Clearly, some are better than others. We get to choose. Which one do you want to take?

Stand up for a More Sustainable Future

Join The Nature Conservancy as we call on leaders to support science-backed solutions.

Getting to Sustainability

Carbon Capture

The most powerful carbon capture technology is cheap, readily available and growing all around us: Trees and plants.

Energy Sprawl Solutions

We can ramp up clean energy worldwide and site it wisely to limit the effect on wildlife.

Fishing for Better Data

Electronic monitoring can make fisheries more sustainable.

What Will Your Life Be Like in 2050?

Will it be just like today, but electric? Or will it be very different?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Lloyd-Alter-bw-883700895c6844cf9127ab9289968e93.jpg)

- University of Toronto

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/HaleyMast-2035b42e12d14d4abd433e014e63276c.jpg)

- Harvard University Extension School

Hulton Archives/ Getty Images

- Environment

- Business & Policy

- Home & Design

- Current Events

- Treehugger Voices

- News Archive

New Scientist magazine's chief reporter Adam Vaughan recently published "Net-zero living: how your day will look in a carbon-neutral world ." Here, he imagines what a typical day would be like in the future—through the lens of Isla, "a child today, in 2050"—after we've cut carbon emissions. Vaughan says “most of us are lacking a visualization of what life will be like at net zero” and acknowledges the writing is fiction: "By its nature, it is speculative – but it is informed by research, expert opinion, and trials happening right now.”

Isla lives in the south of the United Kingdom—will it still be a united kingdom in 2050?—and her life looks pretty much like life does today: She has a house, a car, a job, and a cup of tea in the morning. There are wind turbines, great forests, and giant machines sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. It all sounds like a green and pleasant land, but it didn’t sound like the future to me.

It’s an interesting exercise, imagining what it will be like in 30 years. I thought I would give it a try: Here is some speculative fiction about Edie, living in Toronto, Canada in 2050.

Edie’s alarm goes off at 4:00 a.m. She gets up, folds up the bed in the converted garage in an old house in Toronto that is her apartment and workshop, and makes herself a cup of caffeine-infused chicory; only the very rich can afford real coffee 1 .

She considers herself to be very lucky to have this garage in what was her grandparents’ house. The only people who live in houses these days either inherited them or are multi-millionaires from all over the world, but especially from Arizona and other Southern states 2 , desperate to move Canada with its cooler climate and plentiful water and can afford the million-dollar immigrant visa fee.

She hurries to prepare her pushcart, actually a big electric cargo bike, filling it with the tomatoes, and preserves and pickles she prepared with fruits and vegetables she bought from backyard gardeners. Edie then rides it downtown where all the big office buildings have been converted into tiny apartments for climate refugees. The streets downtown look very much like Delancey Street in New York looked like in 1905, with e-pushcarts lining the roads where cars used to park.

Edie is lucky to be working. There are no office or industrial jobs anymore: Artificial Intelligence and robots took care of that 3 . The few jobs left are in service, culture, craft, health care, or real estate. In fact, selling real estate has become the nation’s biggest industry; there is a lot of it, and Sudbury is the new Miami.

Fortunately for Edie, there is a big demand for homemade foods from trustworthy sources. All the food in the grocery stores is grown in test tubes or made in factories. Edie sells out and rides home in time for siesta. There may be lots of electricity from wind and solar farms, but even running tiny heat pumps 4 for cooling is really expensive at peak times. The streets are unpleasantly hot, so many people sleep through the midday.

She checks the balance in her Personal Carbon Allowance (PCA) account to see if she has enough to buy another imported battery for her pushcart e-bike 5 after her nap; batteries have a lot of embodied carbon and transportation emissions and might eat up a month’s worth of her PCA. If she doesn’t have enough then she will have to buy carbon credits, and they are expensive. She sets her alarm for 6:00 p.m. when the streets of Toronto will come alive again on this hot November day.

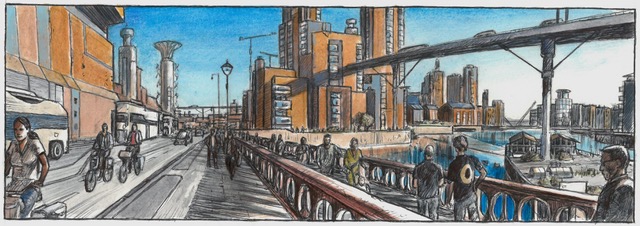

The New Scientist article is illustrated with an image showing people walking and biking, turbines spinning, electric trains running, with kayaks, not cars. This is not an uncommon vision: There are many who suggest we just have to electrify everything and cover it all with solar panels and then we can keep on with the happy motoring.

I am not so optimistic. If we don't keep the global rise in temperature to under 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit (1.5 degrees Celsius) then things are going to get messy. So this story was not just a speculative fantasy but based on previous writing about the need for sufficiency and worries about the embodied carbon of making everything , with some notes from previous Treehugger posts:

- Thanks to climate change, "Coffee plantations in South America, Africa, Asia, and Hawaii are all being threatened by rising air temperatures and erratic rainfall patterns, which invite disease and invasive species to infest the coffee plant and ripening beans." More in Treehugger.

- "Dwindling water supplies and below-average rainfall have consequences for those living in the West." More in Treehugger.

- "We're witnessing the Third Industrial Revolution Playing out in real time." More in Treehugger.

- Tiny heat pumps for tiny spaces are probably going to be common. More in Treehugger.

- Electric cargo bikes will be a powerful tool for low-carbon commerce. More in Treehugger.

- What Will Our Gardens Look Like in 2050?

- Can the Concrete Industry Really Go Carbon Neutral by 2050?

- 2030 Is Out. How About 2050 – Is 2050 Good For You?

- 'The Future We Choose: Surviving the Climate Crisis' (Book Review)

- 2021 in Review: The Year in Net-Zero

- Carbon Emissions Will Kill People. Be Careful Whom You Blame.

- Net-Zero Efforts of Canadian Oil Sands Companies Are Greenwashing

- The International Energy Agency Aims for Net-Zero by 2024

- Architecture 2030 Goes After Embodied Carbon and This Is a Very Big Deal

- John Kerry Says Half of Carbon Cuts Will Come from Tech That We Don't Have

- Emissions from Diet Could Eat Up the Entire 1.5 Degree Carbon Budget

- IPCC Report Is a Prescription for Fixing the Climate Crisis—'It's Now or Never'

- A Year of Living the 1.5 Degree Lifestyle, Extreme Edition

- What Does '12 Years to Save the Planet' Really Mean?

- Generational Divide Over Climate Action Isn't Real, Study Finds

- You Can Live a 1.5 Degree Lifestyle, New Pilot Study Shows

- climate change

Hello From the Year 2050. We Avoided the Worst of Climate Change — But Everything Is Different

L et’s imagine for a moment that we’ve reached the middle of the century. It’s 2050, and we have a moment to reflect—the climate fight remains the consuming battle of our age, but its most intense phase may be in our rearview mirror. And so we can look back to see how we might have managed to dramatically change our society and economy. We had no other choice.

There was a point after 2020 when we began to collectively realize a few basic things.

One, we weren’t getting out of this unscathed. Climate change, even in its early stages, had begun to hurt: watching a California city literally called Paradise turn into hell inside of two hours made it clear that all Americans were at risk. When you breathe wildfire smoke half the summer in your Silicon Valley fortress, or struggle to find insurance for your Florida beach house, doubt creeps in even for those who imagined they were immune.

Two, there were actually some solutions. By 2020, renewable energy was the cheapest way to generate electricity around the planet—in fact, the cheapest way there ever had been. The engineers had done their job, taking sun and wind from quirky backyard DIY projects to cutting-edge technology. Batteries had plummeted down the same cost curve as renewable energy, so the fact that the sun went down at night no longer mattered quite so much—you could store its rays to use later.

And the third realization? People began to understand that the biggest reason we weren’t making full, fast use of these new technologies was the political power of the fossil-fuel industry. Investigative journalists had exposed its three-decade campaign of denial and disinformation, and attorneys general and plaintiffs’ lawyers were beginning to pick them apart. And just in time.

These trends first intersected powerfully on Election Day in 2020. The Halloween hurricane that crashed into the Gulf didn’t just take hundreds of lives and thousands of homes; it revealed a political seam that had begun to show up in polling data a year or two before. Of all the issues that made suburban Americans—women especially—uneasy about President Trump, his stance on climate change was near the top. What had seemed a modest lead for the Democratic challenger widened during the last week of the campaign as damage reports from Louisiana and Mississippi rolled in; on election night it turned into a rout, and the analysts insisted that an underappreciated “green vote” had played a vital part—after all, actual green parties in Canada, the U.K. and much of continental Europe were also outperforming expectations. Young voters were turning out in record numbers: the Greta Generation, as punsters were calling them, made climate change their No. 1 issue.

And when the new President took the oath of office, she didn’t disappoint. In her Inaugural Address, she pledged to immediately put America back in the Paris Agreement—but then she added, “We know by now that Paris is nowhere near enough. Even if all the countries followed all the promises made in that accord, the temperature would still rise more than 3°C (5°F or 6°F). If we let the planet warm that much, we won’t be able to have civilizations like the ones we’re used to. So we’re going to make the changes we need to make, and we’re going to make them fast.”

Fast, of course, is a word that doesn’t really apply to Capitol Hill or most of the world’s other Congresses, Parliaments and Central Committees. It took constant demonstrations from ever larger groups like Extinction Rebellion, and led by young activists especially from the communities suffering the most, to ensure that politicians feared an angry electorate more than an angry carbon lobby. But America, which historically had poured more carbon into the atmosphere than any other nation, did cease blocking progress. With the filibuster removed, the Senate passed—by the narrowest of margins—one bill after another to end subsidies for coal and gas and oil companies, began to tax the carbon they produced, and acted on the basic principles of the Green New Deal: funding the rapid deployment of solar panels and wind turbines, guaranteeing federal jobs for anyone who wanted that work, and putting an end to drilling and mining on federal lands.

Sign up for One.Five, TIME’s climate change newsletter

Since those public lands trailed only China, the U.S., India and Russia as a source of carbon, that was a big deal. Its biggest impact was on Wall Street, where investors began to treat fossil-fuel stocks with increasing disdain. When BlackRock, the biggest money manager in the world, cleaned its basic passive index fund of coal, oil and gas stocks, the companies were essentially rendered off-limits to normal investors. As protesters began cutting up their Chase bank cards, the biggest lender to the fossil-fuel industry suddenly decided green investments made more sense. Even the staid insurance industry began refusing to underwrite new oil and gas pipelines—and shorn of its easy access to capital, the industry was also shorn of much of its political influence. Every quarter meant fewer voters who mined coal and more who installed solar panels, and that made political change even easier.

As America’s new leaders began trying to mend fences with other nations, climate action proved to be a crucial way to rebuild diplomatic trust. China and India had their own reasons for wanting swift action—mostly, the fact that smog-choked cities and ever deadlier heat waves were undermining the stability of the ruling regimes. When Beijing announced that its Belt and Road Initiative would run on renewable energy, not coal, the energy future of much of Asia changed overnight. When India started mandating electric cars and scooters for urban areas, the future of the internal-combustion engine was largely sealed. Teslas continued to attract upscale Americans, but the real numbers came from lower-priced electric cars pouring out of Asian factories. That was enough to finally convince even Detroit that a seismic shift was under way: when the first generation of Ford E-150 pickups debuted, with ads demonstrating their unmatched torque by showing them towing a million-pound locomotive, only the most unreconstructed motorheads were still insisting on the superiority of gas-powered rides.

Other easy technological gains came in our homes. After a century of keeping a tank of oil or gas in the basement for heating, people quickly discovered the appeal of air-source heat pumps, which turned the heat of the outdoors (even on those rare days when the temperature still dropped below zero) into comfortable indoor air. Gas burners gave way to induction cooktops. The last incandescent bulbs were in museums, and even most of the compact fluorescents had been long since replaced by LEDs. Electricity demand was up—but when people plugged in their electric vehicles at night, the ever growing fleet increasingly acted like a vast battery, smoothing out the curves as the wind dropped or the sun clouded. Some people stopped eating meat, and lots and lots of people ate less of it—a cultural transformation made easier by the fact that Impossible Burgers turned out to be at least as juicy as the pucks that fast-food chains had been slinging for years. The number of cows on the world’s farms started to drop, and with them the source of perhaps a fifth of emissions. More crucially, new diets reduced the pressure to cut down the remaining tropical rain forests to make way for grazing land.

In other words, the low-hanging fruit was quickly plucked, and the pluckers were well paid. Perhaps the fastest-growing business on the planet involved third-party firms that would retrofit a factory or an office with energy-efficient technology and simply take a cut of the savings on the monthly electric bill. Small businesses, and rural communities, began to notice the economic advantages of keeping the money paid for power relatively close to home instead of shipping it off to Houston or Riyadh. The world had wasted so much energy that much of the early work was easy, like losing weight by getting your hair cut.

But the early euphoria came to an end pretty quickly. By the end of the 2020s, it became clear we would have to pay the price of delaying action for decades.

For one thing, the cuts in emissions that scientists prescribed were almost impossibly deep. “If you’d started in 1990 when we first warned you, the job was manageable: you could have cut carbon a percent or two a year,” one eminent physicist explained. “But waiting 30 years turned a bunny slope into a black diamond.” As usual, the easy “solutions” turned out to be no help at all: fracked natural-gas wells were leaking vast quantities of methane into the atmosphere, and “biomass burning”—cutting down forests to burn them for electricity—was putting a pulse of carbon into the air at precisely the wrong moment. (As it happened, the math showed letting trees stand was crucial for pulling carbon from the atmosphere—when secondary forests were allowed to grow, they sucked up a third or more of the excess carbon humanity was producing.) Environmentalists learned they needed to make some compromises, and so most of America’s aging nuclear reactors were left online past their decommissioning dates: that lower-carbon power supplemented the surging renewable industry in the early years, even as researchers continued work to see if fusion power, thorium reactors or some other advanced design could work.

The real problem, though, was that climate change itself kept accelerating, even as the world began trying to turn its energy and agriculture systems around. The giant slug of carbon that the world had put into the atmosphere—more since 1990 than in all of human history before—acted like a time-delayed fuse, and the temperature just kept rising. Worse, it appeared that scientists had systematically underestimated just how much damage each tenth of a degree would actually do, a point underscored in 2032 when a behemoth slice of the West Antarctic ice sheet slid majestically into the southern ocean, and all of a sudden the rise in sea level was being measured in feet, not inches. (Nothing, it turned out, could move Americans to embrace the metric system.) And the heating kept triggering feedback loops that in turn accelerated the heating: ever larger wildfires, for instance, kept pushing ever more carbon into the air, and their smoke blackened ice sheets that in turn melted even faster.

This hotter world produced an ongoing spate of emergencies: “forest-fire season” was now essentially year-round, and the warmer ocean kept hurricanes and typhoons boiling months past the old norms. And sometimes the damage was novel: ancient carcasses kept emerging from the melting permafrost of the north, and with them germs from illnesses long thought extinct. But the greatest crises were the slower, more inexorable ones: the ongoing drought and desertification was forcing huge numbers of Africans, Asians and Central Americans to move; in many places, the heat waves had literally become unbearable, with nighttime temperatures staying above 100°F and outdoor work all but impossible for weeks and months at a time. On low-lying ground like the Mekong Delta, the rising ocean salted fields essential to supplying the world with rice. The U.N. had long ago estimated the century could see a billion climate refugees, and it was beginning to appear it was unnervingly correct. What could the rich countries say? These were people who hadn’t caused the crisis now devouring their lives, and there weren’t enough walls and cages to keep them at bay, so the migrations kept roiling the politics of the planet.

There were, in fact, two possible ways forward. The most obvious path was a constant competition between nations and individuals to see who could thrive in this new climate regime, with luckier places turning themselves into fortresses above the flood. Indeed some people in some places tried to cling to old notions: plug in some solar panels and they could somehow return to a more naive world, where economic expansion was still the goal of every government.

But there was a second response that carried the day in most countries, as growing numbers of people came to understand that the ground beneath our feet had truly shifted. If the economy was the lens through which we’d viewed the world for a century, now survival was the only sensible basis on which to make decisions. Those decisions targeted not just carbon dioxide; these societies went after the wild inequality that also marked the age. The Green New Deal turned out to be everything the Koch brothers had most feared when it was introduced: a tool to make America a fairer, healthier, better-educated place. It was emulated around the world, just as America’s Clean Air Act had long served as a template for laws across the globe. Slowly both the Keeling Curve, measuring carbon in the atmosphere, and the Gini coefficient, measuring the distribution of wealth, began to flatten.

That’s where we are today. We clearly did not “escape” climate change or “solve” global warming—the temperature keeps climbing, though the rate of increase has lessened. It’s turned into a wretched century, which is considerably better than a catastrophic one. We ended up with the most profound and most dangerous physical changes in human history. Our civilization surely teetered—and an enormous number of people paid an unfair and overwhelming price—but it did not fall.

People have learned to defend what can be practically defended: expensive seawalls and pumps mean New York is still New York, though the Antarctic may yet have something to say on the subject. Other places we’ve learned to let go: much of the East Coast has moved in a few miles, to more defensible ground. Yes, that took trillions of dollars in real estate off the board—but the roads and the bridges would have cost trillions to defend, and even then the odds were bad.

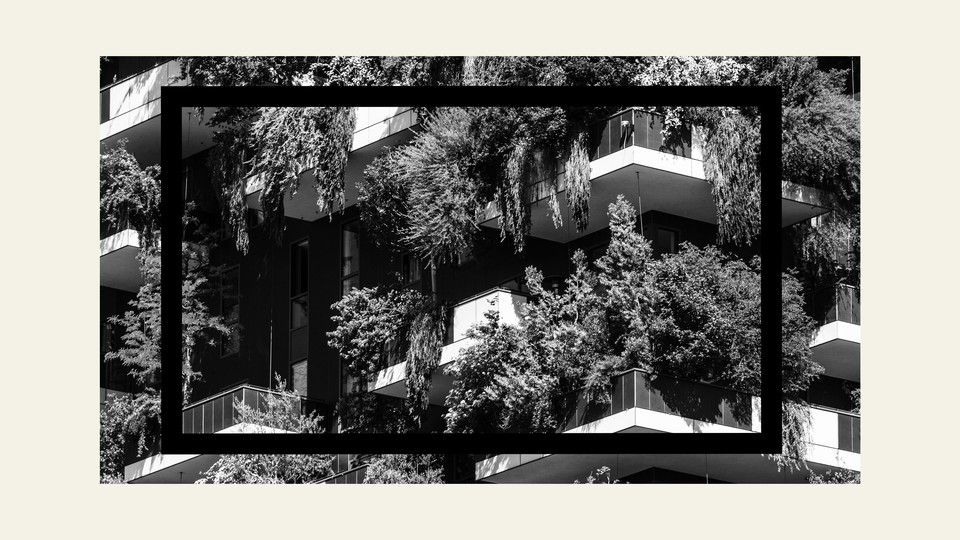

Cities look different now—much more densely populated, as NIMBY defenses against new development gave way to an increasingly vibrant urbanism. Smart municipalities banned private cars from the center of town, opening up free public-transit systems and building civic fleets of self-driving cars that got rid of the space wasted on parking spots. But rural districts have changed too: the erratic weather put a premium on hands-on agricultural skills, which in turn provided opportunities for migrants arriving from ruined farmlands elsewhere. (Farming around solar panels has become a particular specialty.) America’s rail network is not quite as good as it was in the early 20th century, but it gets closer each year, which is good news since low-carbon air travel proved hard to get off the ground.

What’s changed most of all is the mood. The defiant notion that we would forever overcome nature has given way to pride of a different kind: increasingly we celebrate our ability to bend without breaking, to adapt as gracefully as possible to a natural world whose temper we’ve come to respect. When we look back to the start of the century we are, of course, angry that people did so little to slow the great heating: if we’d acknowledged climate change in earnest a decade or two earlier, we might have shaved a degree off the temperature, and a degree is measured in great pain and peril. But we also know it was hard for people to grasp what was happening: human history stretched back 10,000 years, and those millennia were physically stable, so it made emotional sense to assume that stability would stretch forward as well as past.

We know much better now: we know that we’ve knocked the planet off its foundations, and that our job, for the foreseeable centuries, is to absorb the bounces as she rolls. We’re dancing as nimbly as we can, and so far we haven’t crashed.

This is one article in a series on the state of the planet’s response to climate change. Read the rest of the stories and sign up for One.Five, TIME’s climate change newsletter.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People in AI 2024

- Inside the Rise of Bitcoin-Powered Pools and Bathhouses

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What Makes a Friendship Last Forever?

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- Your Questions About Early Voting , Answered

- Column: Your Cynicism Isn’t Helping Anybody

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at [email protected]

To revisit this article, visit My Profile, then View saved stories .

- The Big Story

- Newsletters

- Steven Levy's Plaintext Column

- WIRED Classics from the Archive

- WIRED Insider

- WIRED Consulting

Yuval Noah Harari on what the year 2050 has in store for humankind

Forget programming - the best skill to teach children is reinvention. In this exclusive extract from his new book, the author of Sapiens reveals what 2050 has in store for humankind.

Part one: Change is the only constant

Humankind is facing unprecedented revolutions, all our old stories are crumbling and no new story has so far emerged to replace them. How can we prepare ourselves and our children for a world of such unprecedented transformations and radical uncertainties? A baby born today will be thirty-something in 2050. If all goes well, that baby will still be around in 2100, and might even be an active citizen of the 22nd century. What should we teach that baby that will help him or her survive and flourish in the world of 2050 or of the 22nd century? What kind of skills will he or she need in order to get a job, understand what is happening around them and navigate the maze of life?

Unfortunately, since nobody knows how the world will look in 2050 – not to mention 2100 – we don’t know the answer to these questions. Of course, humans have never been able to predict the future with accuracy. But today it is more difficult than ever before, because once technology enables us to engineer bodies, brains and minds, we can no longer be certain about anything – including things that previously seemed fixed and eternal.

A thousand years ago, in 1018, there were many things people didn’t know about the future, but they were nevertheless convinced that the basic features of human society were not going to change. If you lived in China in 1018, you knew that by 1050 the Song Empire might collapse, the Khitans might invade from the north, and plagues might kill millions. However, it was clear to you that even in 1050 most people would still work as farmers and weavers, rulers would still rely on humans to staff their armies and bureaucracies, men would still dominate women, life expectancy would still be about 40, and the human body would be exactly the same. Hence in 1018, poor Chinese parents taught their children how to plant rice or weave silk, and wealthier parents taught their boys how to read the Confucian classics, write calligraphy or fight on horseback – and taught their girls to be modest and obedient housewives. It was obvious these skills would still be needed in 1050.

In contrast, today we have no idea how China or the rest of the world will look in 2050. We don’t know what people will do for a living, we don’t know how armies or bureaucracies will function, and we don’t know what gender relations will be like. Some people will probably live much longer than today, and the human body itself might undergo an unprecedented revolution thanks to bioengineering and direct brain-computer interfaces. Much of what kids learn today will likely be irrelevant by 2050.

At present, too many schools focus on cramming information. In the past this made sense, because information was scarce, and even the slow trickle of existing information was repeatedly blocked by censorship. If you lived, say, in a small provincial town in Mexico in 1800, it was difficult for you to know much about the wider world. There was no radio, television, daily newspapers or public libraries. Even if you were literate and had access to a private library, there was not much to read other than novels and religious tracts. The Spanish Empire heavily censored all texts printed locally, and allowed only a dribble of vetted publications to be imported from outside. Much the same was true if you lived in some provincial town in Russia, India, Turkey or China. When modern schools came along, teaching every child to read and write and imparting the basic facts of geography, history and biology, they represented an immense improvement.

In contrast, in the 21st century we are flooded by enormous amounts of information, and even the censors don’t try to block it. Instead, they are busy spreading misinformation or distracting us with irrelevancies. If you live in some provincial Mexican town and you have a smartphone, you can spend many lifetimes just reading Wikipedia, watching TED talks, and taking free online courses. No government can hope to conceal all the information it doesn’t like. On the other hand, it is alarmingly easy to inundate the public with conflicting reports and red herrings. People all over the world are but a click away from the latest accounts of the bombardment of Aleppo or of melting ice caps in the Arctic, but there are so many contradictory accounts that it is hard to know what to believe. Besides, countless other things are just a click away, making it difficult to focus, and when politics or science look too complicated it is tempting to switch to funny cat videos, celebrity gossip or porn.

In such a world, the last thing a teacher needs to give her pupils is more information. They already have far too much of it. Instead, people need the ability to make sense of information, to tell the difference between what is important and what is unimportant, and above all to combine many bits of information into a broad picture of the world.

In truth, this has been the ideal of western liberal education for centuries, but up till now even many western schools have been rather slack in fulfilling it. Teachers allowed themselves to focus on shoving data while encouraging pupils “to think for themselves”. Due to their fear of authoritarianism, liberal schools had a particular horror of grand narratives. They assumed that as long as we give students lots of data and a modicum of freedom, the students will create their own picture of the world, and even if this generation fails to synthesise all the data into a coherent and meaningful story of the world, there will be plenty of time to construct a good synthesis in the future. We have now run out of time. The decisions we will take in the next few decades will shape the future of life itself, and we can take these decisions based only on our present world view. If this generation lacks a comprehensive view of the cosmos, the future of life will be decided at random.

Part two: The heat is on

Besides information, most schools also focus too much on providing pupils with a set of predetermined skills such as solving differential equations, writing computer code in C++, identifying chemicals in a test tube or conversing in Chinese. Yet since we have no idea how the world and the job market will look in 2050, we don’t really know what particular skills people will need. We might invest a lot of effort teaching kids how to write in C++ or how to speak Chinese, only to discover that by 2050 AI can code software far better than humans, and a new Google Translate app enables you to conduct a conversation in almost flawless Mandarin, Cantonese or Hakka, even though you only know how to say “Ni hao”.

So what should we be teaching? Many pedagogical experts argue that schools should switch to teaching “the four Cs” – critical thinking, communication, collaboration and creativity. More broadly, schools should downplay technical skills and emphasise general-purpose life skills. Most important of all will be the ability to deal with change, to learn new things and to preserve your mental balance in unfamiliar situations. In order to keep up with the world of 2050, you will need not merely to invent new ideas and products – you will above all need to reinvent yourself again and again.

For as the pace of change increases, not just the economy, but the very meaning of “being human” is likely to mutate. In 1848, the Communist Manifesto declared that “all that is solid melts into air”. Marx and Engels, however, were thinking mainly about social and economic structures. By 2048, physical and cognitive structures will also melt into air, or into a cloud of data bits.

In 1848, millions of people were losing their jobs on village farms, and were going to the big cities to work in factories. But upon reaching the big city, they were unlikely to change their gender or to add a sixth sense. And if they found a job in some textile factory, they could expect to remain in that profession for the rest of their working lives.

By 2048, people might have to cope with migrations to cyberspace, with fluid gender identities, and with new sensory experiences generated by computer implants. If they find both work and meaning in designing up-to-the-minute fashions for a 3D virtual-reality game, within a decade not just this particular profession, but all jobs demanding this level of artistic creation might be taken over by AI. So at 25, you introduce yourself on a dating site as “a twenty-five-year-old heterosexual woman who lives in London and works in a fashion shop.” At 35, you say you are “a gender-non-specific person undergoing age- adjustment, whose neocortical activity takes place mainly in the NewCosmos virtual world, and whose life mission is to go where no fashion designer has gone before”. At 45, both dating and self-definitions are so passé. You just wait for an algorithm to find (or create) the perfect match for you. As for drawing meaning from the art of fashion design, you are so irrevocably outclassed by the algorithms, that looking at your crowning achievements from the previous decade fills you with embarrassment rather than pride. And at 45, you still have many decades of radical change ahead of you.

Please don’t take this scenario literally. Nobody can really predict the specific changes we will witness. Any particular scenario is likely to be far from the truth. If somebody describes to you the world of the mid-21st century and it sounds like science fiction, it is probably false. But then if somebody describes to you the world of the mid 21st-century and it doesn’t sound like science fiction – it is certainly false. We cannot be sure of the specifics, but change itself is the only certainty.

Such profound change may well transform the basic structure of life, making discontinuity its most salient feature. From time immemorial, life was divided into two complementary parts: a period of learning followed by a period of working. In the first part of life you accumulated information, developed skills, constructed a world view, and built a stable identity. Even if at 15 you spent most of your day working in the family’s rice field (rather than in a formal school), the most important thing you were doing was learning: how to cultivate rice, how to conduct negotiations with the greedy rice merchants from the big city and how to resolve conflicts over land and water with the other villagers. In the second part of life you relied on your accumulated skills to navigate the world, earn a living, and contribute to society. Of course, even at 50 you continued to learn new things about rice, about merchants and about conflicts, but these were just small tweaks to well-honed abilities.

By the middle of the 21st century, accelerating change plus longer lifespans will make this traditional model obsolete. Life will come apart at the seams, and there will be less and less continuity between different periods of life. “Who am I?” will be a more urgent and complicated question than ever before.

This is likely to involve immense levels of stress. For change is almost always stressful, and after a certain age most people just don’t like to change. When you are 15, your entire life is change. Your body is growing, your mind is developing, your relationships are deepening. Everything is in flux, and everything is new. You are busy inventing yourself. Most teenagers find it frightening, but at the same time, also exciting. New vistas are opening before you, and you have an entire world to conquer. By the time you are 50, you don’t want change, and most people have given up on conquering the world. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt. You much prefer stability. You have invested so much in your skills, your career, your identity and your world view that you don’t want to start all over again. The harder you’ve worked on building something, the more difficult it is to let go of it and make room for something new. You might still cherish new experiences and minor adjustments, but most people in their fifties aren’t ready to overhaul the deep structures of their identity and personality.

There are neurological reasons for this. Though the adult brain is more flexible and volatile than was once thought, it is still less malleable than the teenage brain. Reconnecting neurons and rewiring synapses is damned hard work. But in the 21st century, you can hardly afford stability. If you try to hold on to some stable identity, job or world view, you risk being left behind as the world flies by you with a whooooosh. Given that life expectancy is likely to increase, you might subsequently have to spend many decades as a clueless fossil. To stay relevant – not just economically, but above all socially – you will need the ability to constantly learn and to reinvent yourself, certainly at a young age like 50.

As strangeness becomes the new normal, your past experiences, as well as the past experiences of the whole of humanity, will become less reliable guides. Humans as individuals and humankind as a whole will increasingly have to deal with things nobody ever encountered before, such as super-intelligent machines, engineered bodies, algorithms that can manipulate your emotions with uncanny precision, rapid man-made climate cataclysms, and the need to change your profession every decade. What is the right thing to do when confronting a completely unprecedented situation? How should you act when you are flooded by enormous amounts of information and there is absolutely no way you can absorb and analyse it all? How to live in a world where profound uncertainty is not a bug, but a feature?

To survive and flourish in such a world, you will need a lot of mental flexibility and great reserves of emotional balance. You will have to repeatedly let go of some of what you know best, and feel at home with the unknown. Unfortunately, teaching kids to embrace the unknown and to keep their mental balance is far more difficult than teaching them an equation in physics or the causes of the first world war. You cannot learn resilience by reading a book or listening to a lecture. The teachers themselves usually lack the mental flexibility that the 21st century demands, for they themselves are the product of the old educational system.

The Industrial Revolution has bequeathed us the production-line theory of education. In the middle of town there is a large concrete building divided into many identical rooms, each room equipped with rows of desks and chairs. At the sound of a bell, you go to one of these rooms together with 30 other kids who were all born the same year as you. Every hour some grown-up walks in and starts talking. They are all paid to do so by the government. One of them tells you about the shape of the Earth, another tells you about the human past, and a third tells you about the human body. It is easy to laugh at this model, and almost everybody agrees that no matter its past achievements, it is now bankrupt. But so far we haven’t created a viable alter- native. Certainly not a scaleable alternative that can be implemented in rural Mexico rather than just in upmarket California suburbs.

Part three: Hacking humans

So the best advice I could give a 15-year-old stuck in an outdated school somewhere in Mexico, India or Alabama is: don’t rely on the adults too much. Most of them mean well, but they just don’t understand the world. In the past, it was a relatively safe bet to follow the adults, because they knew the world quite well, and the world changed slowly. But the 21st century is going to be different. Due to the growing pace of change, you can never be certain whether what the adults are telling you is timeless wisdom or outdated bias.

So on what can you rely instead? Technology? That’s an even riskier gamble. Technology can help you a lot, but if technology gains too much power over your life, you might become a hostage to its agenda. Thousands of years ago, humans invented agriculture, but this technology enriched just a tiny elite, while enslaving the majority of humans. Most people found themselves working from sunrise till sunset plucking weeds, carrying water buckets and harvesting corn under a blazing sun. It can happen to you too.

Technology isn’t bad. If you know what you want in life, technology can help you get it. But if you don’t know what you want in life, it will be all too easy for technology to shape your aims for you and take control of your life. Especially as technology gets better at understanding humans, you might increasingly find yourself serving it, instead of it serving you. Have you seen those zombies who roam the streets with their faces glued to their smartphones? Do you think they control the technology, or does the technology control them?

Should you rely on yourself, then? That sounds great on Sesame Street or in an old-fashioned Disney film, but in real life it doesn’t work so well. Even Disney is coming to realise it. Just like Inside Ou t’s Riley Andersen , most people hardly know themselves, and when they try to “listen to themselves” they easily become prey to external manipulations. The voice we hear inside our heads was never trustworthy, because it always reflected state propaganda, ideological brainwashing and commercial advertisement, not to mention biochemical bugs.

As biotechnology and machine learning improve, it will become easier to manipulate people’s deepest emotions and desires, and it will become more dangerous than ever to just follow your heart. When Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu or the government knows how to pull the strings of your heart and press the buttons of your brain, could you still tell the difference between your self and their marketing experts?

To succeed in such a daunting task, you will need to work very hard on getting to know your operating system better. To know what you are, and what you want from life. This is, of course, the oldest advice in the book: know thyself. For thousands of years, philosophers and prophets have urged people to know themselves. But this advice was never more urgent than in the 21st century, because unlike in the days of Laozi or Socrates, now you have serious competition. Coca-Cola, Amazon, Baidu and the government are all racing to hack you. Not your smartphone, not your computer, and not your bank account – they are in a race to hack you , and your organic operating system. You might have heard that we are living in the era of hacking computers, but that’s hardly half the truth. In fact, we are living in the era of hacking humans.

The algorithms are watching you right now. They are watching where you go, what you buy, who you meet. Soon they will monitor all your steps, all your breaths, all your heartbeats. They are relying on Big Data and machine learning to get to know you better and better. And once these algorithms know you better than you know yourself, they could control and manipulate you, and you won’t be able to do much about it. You will live in the matrix, or in The Truman Show . In the end, it’s a simple empirical matter: if the algorithms indeed understand what’s happening within you better than you understand it, authority will shift to them.

Of course, you might be perfectly happy ceding all authority to the algorithms and trusting them to decide things for you and for the rest of the world. If so, just relax and enjoy the ride. You don’t need to do anything about it. The algorithms will take care of everything. If, however, you want to retain some control of your personal existence and of the future of life, you have to run faster than the algorithms, faster than Amazon and the government, and get to know yourself before they do. To run fast, don’t take much luggage with you. Leave all your illusions behind. They are very heavy.

Yuval Noah Harari's 21 Lessons for the 21st Century (Vintage Digital) is published on August 30

This article was originally published by WIRED UK

Life in 2050: A Glimpse at Education in the Future

Thanks to growing internet access and emerging technologies, the way we think of education will dramatically change..

Matthew S. Williams

Welcome back to our “Life in 2050” series, where we examine how changes that are anticipated for the coming decades will alter the way people live their lives. In previous installments, we looked at how warfare , the economy , housing , and space exploration (which took two installments to cover!) will change by mid-century.

Today, we take a look at education and how social, economic, and technological changes will revolutionize the way children, youth, and adults go to school. Whereas modern education has generally followed the same model for over three hundred years, a transition is currently taking place that will continue throughout this century.

This transition is similar to what is also taking place in terms of governance, the economy, and recreation. In much the same way, the field of education will evolve in this century to adapt to four major factors. They include:

- Growing access to the internet

- Improvements in technology

- Distributed living and learning

- A new emphasis on problem-solving and gamification

The resulting seismic shift expected to occur by 2050 and after will be tantamount to a revolution in how we think about education and learning. Rather than a centralized structure where information is transmitted, and retention is tested, the classroom of the future is likely to be distributed in nature and far more hands-on.

To the next generations, education in the future will look a lot more like playtime than schooling!

A Time-Honored Model

Since the 19th century, public education has become far more widespread. In 1820, only 12% of people worldwide could read and write. As of 2016, that figure was reversed, where only 14% of the world’s population remained illiterate. Beyond basic literacy, the overall level of education has also increased steadily over time.

Since the latter half of the 20th century, secondary and post-secondary studies (university and college) have expanded considerably across the world. Between 1970 and 2020 , the percentage of adults with no formal education went from 23% to less than 10%; those with a partial (or complete) secondary education went from 16% to 36%; and those with a post-secondary education from about 3.3% to 10%.

Of course, there remains a disparity between the developing and developed world when it comes to education outcomes. According to data released in 2018 by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the percentage of people to graduate secondary school (among their 38 member nations) was 76.86% for men and 84.82% for women.

The same data indicated that among OECD nations, an average of 36.55% of the population (29.41% men and 44.10% women) received a post-secondary degree. This ranges from a Bachelor’s degree (24.07% men, 36.91% women) and a Master’s degree (10.5% men, 16.17% women) to a Ph.D. (less than 1% of men and women).

Despite this expansion in learning, the traditional model of education has remained largely unchanged since the 19th century. This model consists of people divided by age (grades), learning a standardized curriculum that is broken down by subject (maths, sciences, arts, social sciences, and athletics), and being subject to evaluation (quizzes, tests, final exam).

This model has been subject to revision and expansion over time, mainly in response to new technologies, socio-political developments, and economic changes. However, the structure has remained largely intact, with the institutions, curricula, and accreditation standards subject to centralized oversight and control.

Global Internet

According to a 2019 report compiled by the United Nations’ Department of Economic and Social Affairs — titled “ World Population Prospects 2019 ” — the global population is expected to reach 9.74 billion by mid-century. With a population of around 5.29 billion, Asia will still be the most populous continent on the planet.

However, it will be Africa that experiences the most growth between now and mid-century. Currently, Africa has a population of 1.36 billion, which is projected to almost double by 2050 — reaching up to 2.5 billion (an increase of about 83%). This population growth will be mirrored by economic growth, which will then drive another sort of growth.

According to a 2018 report by the UN’s International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 90% of the global population will have access to broadband internet services by 2050, thanks to the growth of mobile devices and satellite internet services . That’s 8.76 billion people, a 220% increase over the 4 billion people (about half of the global population) that have access right now.

The majority of these new users will come from the “developing nations,” meaning countries in Africa, South America, and Oceania. Therefore, the internet of the future will be far more representative of the global population as more stories, events, and trends that drive online behavior come from outside of Europe and North America.

Similarly, the internet will grow immensely as trillions of devices, cameras, sensors, homes, and cities are connected to the internet — creating a massive expansion in the “ Internet of Things .” Given the astronomical amount of data that this will generate on a regular basis, machine learning and AI will be incorporated to keep track of it all, find patterns in the chaos, and even predict future trends.

AI will also advance thanks to research into the human brain and biotechnology, which will lead to neural net computing that is much closer to the real thing. Similarly, this research will lead to more advanced versions of Neuralink , neural implants that will help remedy neurological disorders and brain injuries, and also allow for brain-to-machine interfacing.

This means that later in this century, people will be able to perform all the tasks they rely on their computers for, but in a way that doesn’t require a device. For those who find the idea of neural implants unsettling or repugnant, computing will still be possible using smart glasses, smart contact lenses , and wearable computers .

From Distance Ed to MOOCs

In the past year, the coronavirus and resulting school closures have been a major driving force for the growth of online learning. However, the trend towards decentralization was underway long before that, with virtual classrooms and online education experiencing considerable growth over the past decade.

In fact, a report compiled in February of 2020 by Research and Markets indicated that by 2025, the online education market would be valued at about $320 billion USD . This represents a growth of 170% — and a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.23% since 2019 when the e-learning industry was valued at $187.87 billion USD .

What’s more, much of this growth will be powered by economic progress and rising populations in the developing nations (particularly in Africa, Asia, and South America). Already, online education is considered a cost-effective means to address the rising demand for education in developing nations.

As Stefan Trines, a research editor with the World Education News & Reviews, explained in an op-ed he penned in August of 2018 :

“While still embryonic, digital forms of education will likely eventually be pursued in the same vein as traditional distance learning models and the privatization of education, both of which have helped increase access to education despite concerns over educational quality and social equality.

“Distance education already plays a crucial role in providing access to education for millions of people in the developing world. Open distance education universities in Bangladesh, India, Iran, Pakistan, South Africa, and Turkey alone currently enroll more than 7 million students combined.”

While barriers remain in the form of technological infrastructure (aka. the “digital divide”), the growth of internet access in the next few decades will be accompanied by an explosion in online learning. Another consequence will be the proliferation of Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs) and other forms of e-learning, which will replace traditional distance education.

Here too, the growth in the past few years has been very impressive (and indicative of future trends). Between 2012 and 2018 , the number of MOOCs available increased by more than 683%, while the total number of students enrolled went from 10 million (in 2013) to 81 million, and the number of universities offering them increased by 400% (from 200 to 800).

Between 2020 and 2050 , the number of people without any formal education will decline from 10% to 5% of the global population. While the number of people with a primary and lower secondary education is expected to remain largely the same, the number of people with secondary education is projected to go from 21% to 29% and post-secondary education from 11% to 18.5%.

For developing nations, distributed learning systems will offer a degree of access and flexibility that traditional education cannot. This is similar to the situation in many remote areas of the world, where the necessary infrastructure doesn’t always exist (i.e., roads, school buses, schoolhouses, etc.).

New Technologies & New Realities

Along with near-universal internet access, there are a handful of technologies that will make education much more virtual, immersive, and hands-on. These include augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), haptics , cloud computing, and machine learning (AI). Together, advances in these fields will be utilized to enhance education.

By definition, AR refers to interactions with physical environments that are enhanced with the help of computer-mediated images and sounds, while VR consists of interacting with computer-generated simulated environments. However, by 2050, the line between simulated and physical will be blurred to the point where they are barely distinguishable.

This will be possible thanks to advances in “haptics,” which refers to technology that stimulates the senses. Currently, this technology is limited to stimulating the sensation of touch and the perception of motion. By 2050, however, haptics, AR, and VR are expected to combine in a way that will be capable of creating totally realistic immersive environments.

These environments will stimulate the five major senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, smell) as well as somatosensory perception — pressure, pain, temperature, etc. For students, this could mean simulations that allow the student to step into a moment in history and to see and feel what it was like to live in another time and place — with proper safety measures (let’s not forget that history is full of violence!).

This technology could extend beyond virtual environments and allow students the opportunity to visit places all around the globe and experience what it feels like to actually be there. It’s even possible that this technology will be paired with remote-access robotic hosts so students can physically interact with the local environment and people.

Cloud computing will grow in tandem with increased internet access, leading to an explosion in the amount of data that a classroom generates and has access to. The task of managing this data will be assisted by machine learning algorithms and classroom AIs that will keep track of student tasks, learning, retention, and assess their progress.

New & Personalized Curriculums

In fact, AI-driven diagnostic assessments are likely to replace traditional grading, tests, and exams as the primary means of measuring student achievement. Rather than being given letter grades or pass/fail evaluations, students will need to fulfill certain requirements in order to unlock new levels in their education.