- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction

- Physiological

- Biochemical

- Thermodynamic

- Autopoietic

- The biosphere

- DNA, RNA, and protein

- Chemistry in common

- Energy, carbon, and electrons

- Prokaryotes and eukaryotes

- Multicellularity

- Classification and microbiota

- Temperature and desiccation

- Radiation and nutrient deprivation

- Sizes of organisms

- Metabolites and water

- Photosensitivity, audiosensitivity, thermosensitivity, chemosensitivity, and magnetosensitivity

- Sensing with technology

- Heritability

- Convergence

- Spontaneous generation

- Geologic record

Hypotheses of origins

- Production of polymers

- The earliest living systems

- What is a cell?

- What is cell theory?

- What do cell membranes do?

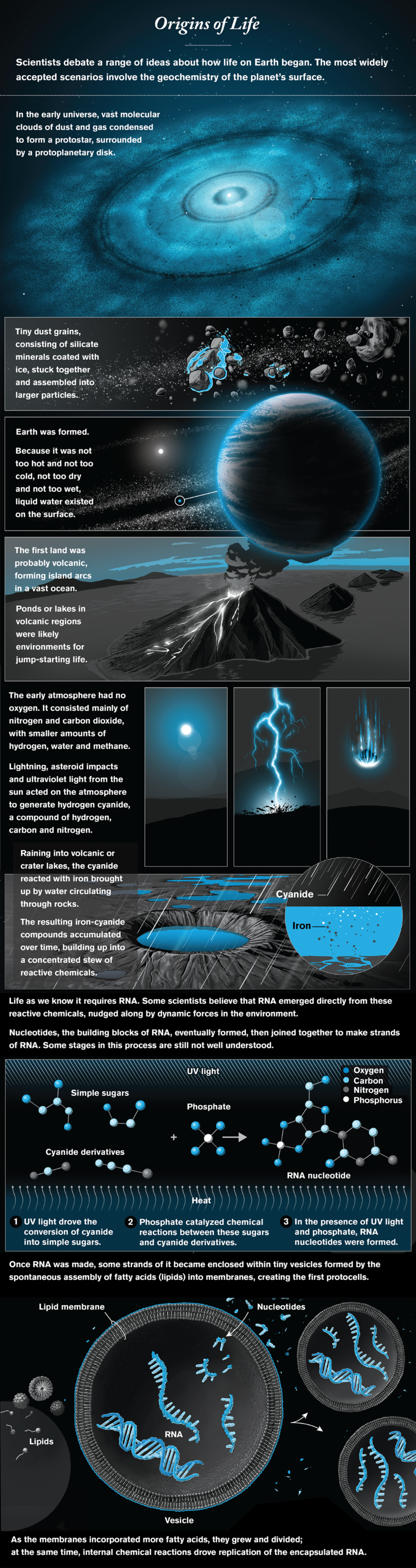

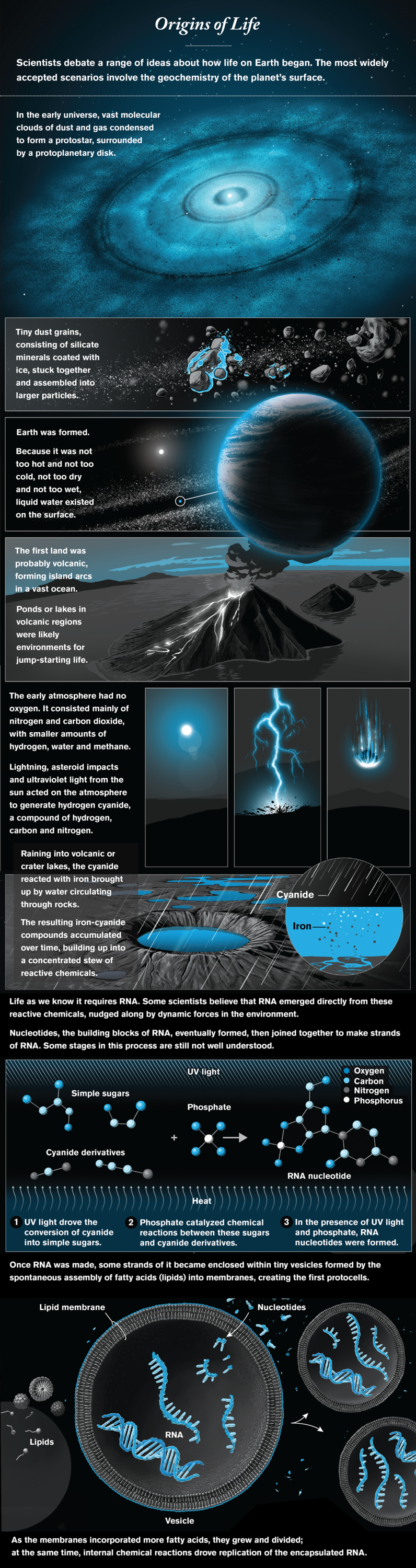

The origin of life

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- Frontiers - What is Life?

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - PubMed Central - What is life?

- University of Minnesota Pressbooks - Introductory Biology: Evolutionary and Ecological Perspectives - Definition of Life

- University of Hawaii - Exploring Our Fluid Earth - Properties of Life

- Biology LibreTexts - The origin of life

- Khan Academy - What is life?

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Life

- Table Of Contents

Perhaps the most fundamental and at the same time the least understood biological problem is the origin of life. It is central to many scientific and philosophical problems and to any consideration of extraterrestrial life . Most of the hypotheses of the origin of life will fall into one of four categories:

- The origin of life is a result of a supernatural event—that is, one irretrievably beyond the descriptive powers of physics , chemistry , and other science .

- Life, particularly simple forms, spontaneously and readily arises from nonliving matter in short periods of time, today as in the past.

- Life is coeternal with matter and has no beginning; life arrived on Earth at the time of Earth’s origin or shortly thereafter.

- Life arose on the early Earth by a series of progressive chemical reactions . Such reactions may have been likely or may have required one or more highly improbable chemical events.

Hypothesis 1, the traditional contention of theology and some philosophy , is in its most general form not inconsistent with contemporary scientific knowledge, although scientific knowledge is inconsistent with a literal interpretation of the biblical accounts given in chapters 1 and 2 of Genesis and in other religious writings. Hypothesis 2 (not of course inconsistent with 1) was the prevailing opinion for centuries. A typical 17th-century view follows:

[May one] doubt whether, in cheese and timber , worms are generated, or, if beetles and wasps, in cow’s dung, or if butterflies, locusts, shellfish , snails, eels, and suchlike be procreated of putrefied matter, which is apt to receive the form of that creature to which it is by the formative power disposed. To question this is to question reason , sense, and experience. If he doubts of this, let him go to Egypt, and there he will find the fields swarming with mice begot of the mud of the Nylus [Nile], to the great calamity of the inhabitants. (Alexander Ross, Arcana Microcosmi , 1652.)

It was not until the Renaissance , with its burgeoning interest in anatomy , that such spontaneous generation of animals from putrefying matter was deemed impossible. During the mid-17th century the British physiologist William Harvey , in the course of his studies on the reproduction and development of the king’s deer , discovered that every animal comes from an egg . An Italian biologist, Francesco Redi , established in the latter part of the 17th century that the maggots in meat came from flies ’ eggs, deposited on the meat. In the 18th century an Italian priest, Lazzaro Spallanzani , showed that fertilization of eggs by sperm was necessary for the reproduction of mammals . Yet the idea of spontaneous generation died hard. Even though it was clear that large animals developed from fertile eggs, there was still hope that smaller beings, microorganisms, spontaneously generated from debris. Many felt it was obvious that the ubiquitous microscopic creatures generated continually from inorganic matter.

Maggots were prevented from developing on meat by covering it with a flyproof screen. Yet grape juice could not be kept from fermenting by putting over it any netting whatever. Spontaneous generation was the subject of a great controversy between the famous French bacteriologists Louis Pasteur and Félix-Archimède Pouchet in the 1850s. Pasteur triumphantly showed that even the most minute creatures came from “ germs ” that floated downward in the air , but that they could be impeded from access to foodstuffs by suitable filtration. Pouchet argued, defensibly, that life must somehow arise from nonliving matter; if not, how had life come about in the first place?

Pasteur’s experimental results were definitive: life does not spontaneously appear from nonliving matter. American historian James Strick reviewed the controversies of the late 19th century between evolutionists who supported the idea of “life from non-life” and their responses to Pasteur’s religious view that only the Deity can make life. The microbiological certainty that life always comes from preexisting life in the form of cells inhibited many post-Pasteur scientists from discussions of the origin of life at all. Many were, and still are, reluctant to offend religious sentiment by probing this provocative subject. But the legitimate issues of life’s origin and its relation to religious and scientific thought raised by Strick and other authors, such as the Australian Reg Morrison, persist today and will continue to engender debate .

Toward the end of the 19th century, hypothesis 3 gained currency. Swedish chemist Svante A. Arrhenius suggested that life on Earth arose from “panspermia,” microscopic spores that wafted through space from planet to planet or solar system to solar system by radiation pressure . This idea, of course, avoids rather than solves the problem of the origin of life. It seems extremely unlikely that any live organism could be transported to Earth over interplanetary or, worse yet , interstellar distances without being killed by the combined effects of cold, desiccation in a vacuum, and radiation .

Although English naturalist Charles Darwin did not commit himself on the origin of life, others subscribed to hypothesis 4 more resolutely. The famous British biologist T.H. Huxley in his book Protoplasm: The Physical Basis of Life (1869) and the British physicist John Tyndall in his “Belfast Address” of 1874 both asserted that life could be generated from inorganic chemicals. However, they had extremely vague ideas about how this might be accomplished. The very phrase “organic molecule” implied, especially then, a class of chemicals uniquely of biological origin. Despite the fact that urea and other organic ( carbon - hydrogen ) molecules had been routinely produced from inorganic chemicals since 1828, the term organic meant “from life” to many scientists and still does. In the following discussion the word organic implies no necessary biological origin. The origin-of-life problem largely reduces to determination of an organic, nonbiological source of certain processes such as the identity maintained by metabolism , growth , and reproduction (i.e., autopoiesis).

Darwin’s attitude was: “It is mere rubbish thinking at present of the origin of life; one might as well think of the origin of matter.” The two problems are in fact curiously connected. Indeed, modern astrophysicists do think about the origin of matter. The evidence is convincing that thermonuclear reactions , either in stellar interiors or in supernova explosions, generate all the chemical elements of the periodic table more massive than hydrogen and helium . Supernova explosions and stellar winds then distribute the elements into the interstellar medium , from which subsequent generations of stars and planets form. These thermonuclear processes are frequent and well-documented. Some thermonuclear reactions are more probable than others. These facts lead to the idea that a certain cosmic distribution of the major elements occurs throughout the universe . Some atoms of biological interest, their relative numerical abundances in the universe as a whole, on Earth, and in living organisms are listed in the table . Even though elemental composition varies from star to star, from place to place on Earth, and from organism to organism, these comparisons are instructive: the composition of life is intermediate between the average composition of the universe and the average composition of Earth. Ninety-nine percent of the mass both of the universe and of life is made of six atoms: hydrogen (H), helium (He), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), and neon (Ne). Might not life on Earth have arisen when Earth’s chemical composition was closer to the average cosmic composition and before subsequent events changed Earth’s gross chemical composition?

| Relative abundances of the elements (percent) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| *0 percent here stands for any quantity less than 10 percent. | |||

| universe | life (terrestrial vegetation) | (crust) | |

| 87 | 16 | 3 | |

| 12 | 0* | 0 | |

| 0.03 | 21 | 0.1 | |

| 0.008 | 3 | 0.0001 | |

| 0.06 | 59 | 49 | |

| 0.02 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.7 | |

| 0.0003 | 0.04 | 8 | |

| 0.0002 | 0.001 | 2 | |

| 0.003 | 0.1 | 14 | |

| 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.7 | |

| 0.00003 | 0.03 | 0.07 | |

| 0.000007 | 0.1 | 0.1 | |

| 0.0004 | 0 | 0 | |

| 0.0001 | 0.1 | 2 | |

| 0.002 | 0.005 | 18 | |

The Jovian planets ( Jupiter , Saturn , Uranus , and Neptune ) are much closer to cosmic composition than is Earth. They are largely gaseous, with atmospheres composed principally of hydrogen and helium. Methane , ammonia , neon, and water have been detected in smaller quantities. This circumstance very strongly suggests that the massive Jovian planets formed from material of typical cosmic composition. Because they are so far from the Sun, their upper atmospheres are very cold. Atoms in the upper atmospheres of the massive, cold Jovian planets cannot now escape from their gravitational fields, and escape was probably difficult even during planetary formation .

Earth and the other planets of the inner solar system , however, are much less massive, and most have hotter upper atmospheres. Hydrogen and helium escape from Earth today; it may well have been possible for much heavier gases to have escaped during Earth’s formation. Very early in Earth’s history, there was a much larger abundance of hydrogen, which has subsequently been lost to space. Most likely the atoms carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen were present on the early Earth, not in the forms of CO 2 ( carbon dioxide ), N 2 , and O 2 as they are today but rather as their fully saturated hydrides: methane, ammonia, and water. The presence of large quantities of reduced (hydrogen-rich) minerals, such as uraninite and pyrite , that were exposed to the ancient atmosphere in sediments formed over two billion years ago implies that atmospheric conditions then were considerably less oxidizing than they are today.

In the 1920s British geneticist J.B.S. Haldane and Russian biochemist Aleksandr Oparin recognized that the nonbiological production of organic molecules in the present oxygen-rich atmosphere of Earth is highly unlikely but that, if Earth once had more hydrogen-rich conditions, the abiogenic production of organic molecules would have been much more likely. If large quantities of organic matter were somehow synthesized on early Earth, they would not necessarily have left much of a trace today. In the present atmosphere—with 21 percent of oxygen produced by cyanobacterial, algal, and plant photosynthesis—organic molecules would tend, over geological time, to be broken down and oxidized to carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and water. As Darwin recognized, the earliest organisms would have tended to consume any organic matter spontaneously produced prior to the origin of life.

The first experimental simulation of early Earth conditions was carried out in 1953 by a graduate student, Stanley L . Miller , under the guidance of his professor at the University of Chicago , chemist Harold C. Urey . A mixture of methane, ammonia, water vapour, and hydrogen was circulated through a liquid solution and continuously sparked by a corona discharge mounted higher in the apparatus. The discharge was thought to represent lightning flashes. After several days of exposure to sparking, the solution changed colour. Several amino and hydroxy acids, familiar chemicals in contemporary Earth life, were produced by this simple procedure. The experiment is simple enough that the amino acids can readily be detected by paper chromatography by high school students. Ultraviolet light or heat was substituted as an energy source in subsequent experiments. The initial abundances of gases were altered. In many other experiments like this, amino acids were formed in large quantities. On the early Earth much more energy was available in ultraviolet light than from lightning discharges. At long ultraviolet wavelengths, methane, ammonia, water, and hydrogen are all transparent, and much of the solar ultraviolet energy lies in this region of the spectrum. The gas hydrogen sulfide was suggested to be a likely compound relevant to ultraviolet absorption in Earth’s early atmosphere. Amino acids were also produced by long-wavelength ultraviolet irradiation of a mixture of methane, ammonia, water, and hydrogen sulfide. At least some of these amino acid syntheses involved hydrogen cyanide and aldehydes (e.g., formaldehyde ) as gaseous intermediates formed from the initial gases. That amino acids, particularly biologically abundant amino acids, are made readily under simulated early Earth conditions is quite remarkable. If oxygen is permitted in these kinds of experiments, no amino acids are formed. This has led to a consensus that hydrogen-rich (or at least oxygen-poor) conditions were necessary for natural organic syntheses prior to the appearance of life.

Under alkaline conditions, and in the presence of inorganic catalysts , formaldehyde spontaneously reacts to form a variety of sugars . The five-carbon sugars fundamental to the formation of nucleic acids , as well as six-carbon sugars such as glucose and fructose , are easily produced. These are common metabolites and structural building blocks in life today. Furthermore, the nucleotide bases and even the biological pigments called porphyrins have been produced in the laboratory under simulated early Earth conditions. Both the details of the experimental synthetic pathways and the question of stability of the small organic molecules produced are vigorously debated. Nevertheless, most, if not all, of the essential building blocks of proteins (amino acids), carbohydrates (sugars), and nucleic acids (nucleotide bases)—that is, the monomers —can be readily produced under conditions thought to have prevailed on Earth in the Archean Eon . The search for the first steps in the origin of life has been transformed from a religious/philosophical exercise to an experimental science.

Covering a story? Visit our page for journalists or call (773) 702-8360.

Top Stories

- Upgraded synchrotron starts up at Argonne National Laboratory

David B. Rowley, geologist who overturned conventional wisdom about Earth’s surface evolution, 1954–2024

How uchicago’s center for the study of gender and sexuality ‘is here for everyone’, the origin of life on earth, explained.

The origin of life on Earth stands as one of the great mysteries of science. Various answers have been proposed, all of which remain unverified. To find out if we are alone in the galaxy, we will need to better understand what geochemical conditions nurtured the first life forms. What water, chemistry and temperature cycles fostered the chemical reactions that allowed life to emerge on our planet? Because life arose in the largely unknown surface conditions of Earth’s early history, answering these and other questions remains a challenge.

Several seminal experiments in this topic have been conducted at the University of Chicago, including the Miller-Urey experiment that suggested how the building blocks of life could form in a primordial soup.

Jump to a section:

- When did life on Earth begin?

Where did life on Earth begin?

What are the ingredients of life on earth, what are the major scientific theories for how life emerged, what is chirality and why is it biologically important, what research are uchicago scientists currently conducting on the origins of life, when did life on earth begin .

Earth is about 4.5 billion years old. Scientists think that by 4.3 billion years ago, Earth may have developed conditions suitable to support life. The oldest known fossils, however, are only 3.7 billion years old. During that 600 million-year window, life may have emerged repeatedly, only to be snuffed out by catastrophic collisions with asteroids and comets.

The details of those early events are not well preserved in Earth’s oldest rocks. Some hints come from the oldest zircons, highly durable minerals that formed in magma. Scientists have found traces of a form of carbon—an important element in living organisms— in one such 4.1 billion-year-old zircon . However, it does not provide enough evidence to prove life’s existence at that early date.

Two possibilities are in volcanically active hydrothermal environments on land and at sea.

Some microorganisms thrive in the scalding, highly acidic hot springs environments like those found today in Iceland, Norway and Yellowstone National Park. The same goes for deep-sea hydrothermal vents. These chimney-like vents form where seawater comes into contact with magma on the ocean floor, resulting in streams of superheated plumes. The microorganisms that live near such plumes have led some scientists to suggest them as the birthplaces of Earth’s first life forms.

Organic molecules may also have formed in certain types of clay minerals that could have offered favorable conditions for protection and preservation. This could have happened on Earth during its early history, or on comets and asteroids that later brought them to Earth in collisions. This would suggest that the same process could have seeded life on planets elsewhere in the universe.

The recipe consists of a steady energy source, organic compounds and water.

Sunlight provides the energy source at the surface, which drives photosynthesis. On the ocean floor, geothermal energy supplies the chemical nutrients that organisms need to live.

Also crucial are the elements important to life . For us, these are carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphorus. But there are several scientific mysteries about how these elements wound up together on Earth. For example, scientists would not expect a planet that formed so close to the sun to naturally incorporate carbon and nitrogen. These elements become solid only under very cold temperatures, such as exist in the outer solar system, not nearer to the sun where Earth is. Also, carbon, like gold, is rare at the Earth’s surface. That’s because carbon chemically bonds more often with iron than rock. Gold also bonds more often with metal, so most of it ends up in the Earth’s core. So, how did the small amounts found at the surface get there? Could a similar process also have unfolded on other planets?

The last ingredient is water. Water now covers about 70% of Earth’s surface, but how much sat on the surface 4 billion years ago? Like carbon and nitrogen, water is much more likely to become a part of solid objects that formed at a greater distance from the sun. To explain its presence on Earth, one theory proposes that a class of meteorites called carbonaceous chondrites formed far enough from the sun to have served as a water-delivery system.

There are several theories for how life came to be on Earth. These include:

Life emerged from a primordial soup

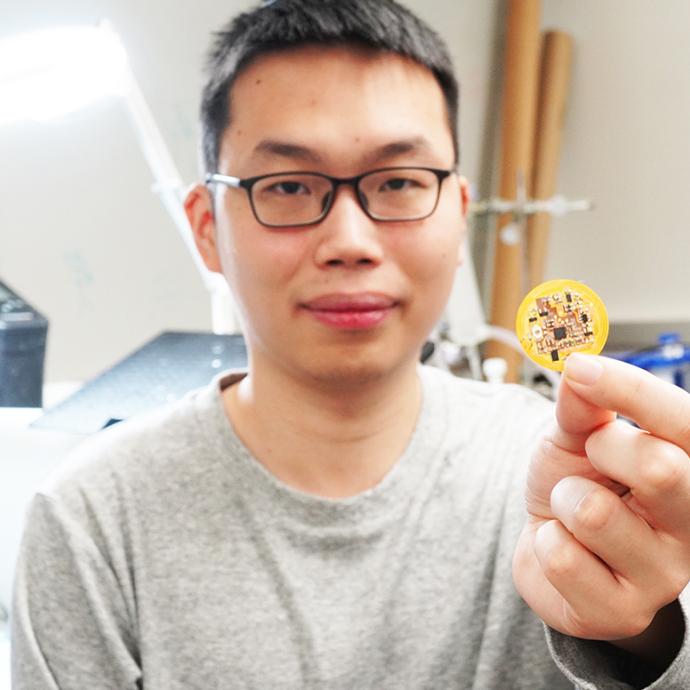

As a University of Chicago graduate student in 1952, Stanley Miller performed a famous experiment with Harold Urey, a Nobel laureate in chemistry. Their results explored the idea that life formed in a primordial soup.

Miller and Urey injected ammonia, methane and water vapor into an enclosed glass container to simulate what were then believed to be the conditions of Earth’s early atmosphere. Then they passed electrical sparks through the container to simulate lightning. Amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, soon formed. Miller and Urey realized that this process could have paved the way for the molecules needed to produce life.

Scientists now believe that Earth’s early atmosphere had a different chemical makeup from Miller and Urey’s recipe. Even so, the experiment gave rise to a new scientific field called prebiotic or abiotic chemistry, the chemistry that preceded the origin of life. This is the opposite of biogenesis, the idea that only a living organism can beget another living organism.

Seeded by comets or meteors

Some scientists think that some of the molecules important to life may be produced outside the Earth. Instead, they suggest that these ingredients came from meteorites or comets.

“A colleague once told me, ‘It’s a lot easier to build a house out of Legos when they’re falling from the sky,’” said Fred Ciesla, a geophysical sciences professor at UChicago. Ciesla and that colleague, Scott Sandford of the NASA Ames Research Center, published research showing that complex organic compounds were readily produced under conditions that likely prevailed in the early solar system when many meteorites formed.

Meteorites then might have served as the cosmic Mayflowers that transported molecular seeds to Earth. In 1969, the Murchison meteorite that fell in Australia contained dozens of different amino acids—the building blocks of life.

Comets may also have offered a ride to Earth-bound hitchhiking molecules, according to experimental results published in 2001 by a team of researchers from Argonne National Laboratory, the University of California Berkeley, and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. By showing that amino acids could survive a fiery comet collision with Earth, the team bolstered the idea that life’s raw materials came from space.

In 2019, a team of researchers in France and Italy reported finding extraterrestrial organic material preserved in the 3.3 billion-year-old sediments of Barberton, South Africa. The team suggested micrometeorites as the material’s likely source. Further such evidence came in 2022 from samples of asteroid Ryugu returned to Earth by Japan’s Hayabusa2 mission. The count of amino acids found in the Ryugu samples now exceeds 20 different types .

In 1953, UChicago researchers published a landmark paper in the Journal of Biological Chemistry that marked the discovery of the pro-chirality concept , which pervades modern chemistry and biology. The paper described an experiment showing that the chirality of molecules—or “handedness,” much the way the right and left hands differ from one another—drives all life processes. Without chirality, large biological molecules such as proteins would be unable to form structures that could be reproduced.

Today, research on the origin of life at UChicago is expanding. As scientists have been able to find more and more exoplanets—that is, planets around stars elsewhere in the galaxy—the question of what the essential ingredients for life are and how to look for signs of them has heated up.

Nobel laureate Jack Szostak joined the UChicago faculty as University Professor in Chemistry in 2022 and will lead the University’s new interdisciplinary Origins of Life Initiative to coordinate research efforts into the origin of life on Earth. Scientists from several departments of the Physical Sciences Division are joining the initiative, including specialists in chemistry, astronomy, geology and geophysics.

“Right now we are getting truly unprecedented amounts of data coming in: Missions like Hayabusa and OSIRIS-REx are bringing us pieces of asteroids, which helps us understand the conditions that form planets, and NASA’s new JWST telescope is taking astounding data on the solar system and the planets around us ,” said Prof. Ciesla. “I think we’re going to make huge progress on this question.”

Last updated Sept. 19, 2022.

Faculty Experts

Clara Blättler

Fred Ciesla

Jack Szostak

Recommended Stories

Earth could have supported crust, life earlier than thought

Earth’s building blocks formed during the solar system’s first…

Additional Resources

The Origins of Life Speaker Series

Recommended Podcasts

Big Brains podcast: Unraveling the mystery of life’s origins on Earth

Discovering the Missing Link with Neil Shubin (Ep. 1)

More Explainers

Improv, Explained

Cosmic rays, explained

Related Topics

Latest news, a uchicago student finds connection and career path in berlin.

Big Brains podcast

Big Brains podcast: What makes something memorable (or forgettable?)

Pride Month

UChicago graduate student selected as 2024 Paul and Daisy Soros Fellow

Go 'Inside the Lab' at UChicago

Explore labs through videos and Q and As with UChicago faculty, staff and students

Inside the Lab

Conservation Lab: Preserving the world’s oldest objects

Around uchicago.

Quantum Computing

Researchers draw inspiration from ancient Alexandria to optimize quantum simulations

Quantrell and PhD Teaching Awards

UChicago announces 2024 winners of Quantrell and PhD Teaching Awards

Campus News

Project to improve accessibility, sustainability of Main Quadrangles

National Academy of Sciences

Five UChicago faculty elected to National Academy of Sciences in 2024

Supply chain software startup FreshX takes first place at 2024 NVC

The College

Two UChicago students honored for commitment to environmental work

Biological Sciences Division

“You have to be open minded, planning to reinvent yourself every five to seven years.”

Kavli Prize

UChicago President Paul Alivisatos shares 2024 Kavli Prize in Nanoscience

Advertisement

How we will discover the mysterious origins of life once and for all

Seventy years ago, three discoveries propelled our understanding of how life on Earth began. But has the biggest clue to life's origins been staring biologists in the face all along?

By Michael Marshall

30 October 2023

The constant changing landscape of Earth may be a vital part of the story of the origins of the first ecosystems.

MARK GARLICK/Spl/Alamy;

HOW did life on Earth begin? Until 70 years ago, generations of scientists had failed to throw much light on biology’s murky beginnings. But then came three crucial findings in quick succession.

In April 1953, the race to uncover the structure of DNA reached its climax. Geneticists soon realised that its double helix form could help explain how life replicates itself – a fundamental property thought to have appeared at or around the origin of life. Just three weeks later, news broke of the astonishing Miller-Urey experiment, which showed how a simple cocktail of chemicals could spontaneously generate amino acids, vital for building the molecules of life. Finally, in September 1953, we gained our first accurate estimate for the age of Earth, giving us a clearer idea of exactly how old life might be.

At that point, we seemed poised to finally understand life’s origins. Today, conclusive answers remain elusive. But the past few years have brought real signs of progress.

For instance, we have found that life’s ability to replicate is not wholly reliant on DNA. We also have a far better idea of the conditions on early Earth when life first appeared – and we are beginning to conduct experiments into how it emerged that are much more sophisticated than Miller-Urey.

A radical new theory rewrites the story of how life on Earth began

It has long been thought that the ingredients for life came together slowly, bit by bit. Now there is evidence it all happened at once in a chemical big bang

So, 70 years on from that incredible year of breakthroughs, how has our picture of life’s…

Article amended on 3 November 2023

Sign up to our weekly newsletter.

Receive a weekly dose of discovery in your inbox! We'll also keep you up to date with New Scientist events and special offers.

To continue reading, subscribe today with our introductory offers

No commitment, cancel anytime*

Offer ends 2nd of July 2024.

*Cancel anytime within 14 days of payment to receive a refund on unserved issues.

Inclusive of applicable taxes (VAT)

Existing subscribers

More from New Scientist

Explore the latest news, articles and features

Quantum biology: New clues on how life might make use of weird physics

Subscriber-only

Environment

To rescue biodiversity, we need a better way to measure it.

Powerful shot of elephants eating garbage up for Earth Photo contest

Why criticisms of the proposed Anthropocene epoch miss the point

Popular articles.

Trending New Scientist articles

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- INNOVATIONS IN

- 09 May 2018

How Did Life Begin?

- Jack Szostak 0

Jack Szostak is a professor of genetics at Harvard Medical School and one of the recipients of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Illustration by Chris Gash

Is the existence of life on Earth a lucky fluke or an inevitable consequence of the laws of nature? Is it simple for life to emerge on a newly formed planet, or is it the virtually impossible product of a long series of unlikely events? Advances in fields as disparate as astronomy, planetary science and chemistry now hold promise that answers to such profound questions may be around the corner. If life turns out to have emerged multiple times in our galaxy, as scientists are hoping to discover, the path to it cannot be so hard. Moreover, if the route from chemistry to biology proves simple to traverse, the universe could be teeming with life.

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets has sparked a renaissance in origin-of-life studies. In a stunning surprise, almost all the newly discovered solar systems look very different from our own. Does that mean something about our own, very odd, system favors the emergence of life? Detecting signs of life on a planet orbiting a distant star is not going to be easy, but the technology for teasing out subtle “biosignatures” is developing so rapidly that with luck we may see distant life within one or two decades.

Innovations In The Biggest Questions In Science

To understand how life might begin, we first have to figure out how—and with what ingredients—planets form. A new generation of radio telescopes, notably the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile’s Atacama Desert, has provided beautiful images of protoplanetary disks and maps of their chemical composition. This information is inspiring better models of how planets assemble from the dust and gases of a disk. Within our own solar system, the Rosetta mission has visited a comet, and OSIRIS-REx will visit, and even try to return samples from, an asteroid, which might give us the essential inventory of the materials that came together in our planet.

Once a planet like our Earth—not too hot and not too cold, not too dry and not too wet—has formed, what chemistry must develop to yield the building blocks of life? In the 1950s the iconic Miller-Urey experiment, which zapped a mixture of water and simple chemicals with electric pulses (to simulate the impact of lightning), demonstrated that amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are easy to make. Other molecules of life turned out to be harder to synthesize, however, and it is now apparent that we need to completely reimagine the path from chemistry to life. The central reason hinges on the versatility of RNA, a very long molecule that plays a multitude of essential roles in all existing forms of life. RNA can not only act like an enzyme, it can also store and transmit information. Remarkably, all the protein in all organisms is made by the catalytic activity of the RNA component of the ribosome, the cellular machine that reads genetic information and makes protein molecules. This observation suggests that RNA dominated an early stage in the evolution of life.

Today the question of how chemistry on the infant Earth gave rise to RNA and to RNA-based cells is the central question of origin-of-life research. Some scientists think that life originally used simpler molecules and only later evolved RNA. Other researchers, however, are tackling the origin of RNA head-on, and exciting new ideas are revolutionizing this once quiet backwater of chemical research. Favored geochemical scenarios involve volcanic regions or impact craters, with complex organic chemistry, multiple sources of energy, and dynamic light-dark, hot-cold and wet-dry cycles. Strikingly, many of the chemical intermediates on the way to RNA crystallize out of reaction mixtures, self-purifying and potentially accumulating on the early Earth as organic minerals—reservoirs of material waiting to come to life when conditions change.

Assuming that key problem is solved, we will still need to understand how RNA was replicated within the first primitive cells. Researchers are just beginning to identify the sources of chemical energy that could enable the RNA to copy itself, but much remains to be done. If these hurdles can also be overcome, we may be able to build replicating, evolving RNA-based cells in the laboratory—recapitulating a possible route to the origin of life.

What next? Chemists are already asking whether our kind of life can be generated only through a single plausible pathway or whether multiple routes might lead from simple chemistry to RNA-based life and on to modern biology. Others are exploring variations on the chemistry of life, seeking clues as to the possible diversity of life “out there” in the universe. If all goes well, we will eventually learn how robust the transition from chemistry to biology is and therefore whether the universe is full of life-forms or—but for us—sterile.

Illustration by Matthew Twombly

Nature 557 , S13-S15 (2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-05098-w

This article is part of Innovations In The Biggest Questions In Science , an editorially independent supplement produced with the financial support of third parties. About this content .

Related Articles

- Nanoscience and technology

Atomic dynamics of electrified solid–liquid interfaces in liquid-cell TEM

Article 19 JUN 24

Fabrication of red-emitting perovskite LEDs by stabilizing their octahedral structure

Article 12 JUN 24

A two-site Kitaev chain in a two-dimensional electron gas

Endowed Chair in Macular Degeneration Research

Dallas, Texas (US)

The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center (UT Southwestern Medical Center)

Postdoctoral Fellow

Postdoc positions on ERC projects – cellular stress responses, proteostasis and autophagy

Frankfurt am Main, Hessen (DE)

Goethe University (GU) Frankfurt am Main - Institute of Molecular Systems Medicine

ZJU 100 Young Professor

Promising young scholars who can independently establish and develop a research direction.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Zhejiang University

Qiushi Chair Professor

Distinguished scholars with notable achievements and extensive international influence.

Research Postdoctoral Fellow - MD

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

June 1, 2018

How Did Life Begin?

Untangling the origins of organisms will require experiments at the tiniest scales and observations at the vastest

By Jack Szostak

Is the existence of life on Earth a lucky fluke or an inevitable consequence of the laws of nature? Is it simple for life to emerge on a newly formed planet, or is it the virtually impossible product of a long series of unlikely events? Advances in fields as disparate as astronomy, planetary science and chemistry now hold promise that answers to such profound questions may be around the corner. If life turns out to have emerged multiple times in our galaxy, as scientists are hoping to discover, the path to it cannot be so hard. Moreover, if the route from chemistry to biology proves simple to traverse, the universe could be teeming with life.

The discovery of thousands of exoplanets has sparked a renaissance in origin-of-life studies. In a stunning surprise, almost all the newly discovered solar systems look very different from our own. Does that mean something about our own, very odd, system favors the emergence of life? Detecting signs of life on a planet orbiting a distant star is not going to be easy, but the technology for teasing out subtle “biosignatures” is developing so rapidly that with luck we may see distant life within one or two decades.

To understand how life might begin, we first have to figure out how—and with what ingredients—planets form. A new generation of radio telescopes, notably the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array in Chile’s Atacama Desert, has provided beautiful images of protoplanetary disks and maps of their chemical composition. This information is inspiring better models of how planets assemble from the dust and gases of a disk. Within our own solar system, the Rosetta mission has visited a comet, and OSIRIS-REx is on its way back to Earth with samples from an asteroid, which might give us the essential inventory of the materials that came together in our planet.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Credit : Matthew Twombly

Once a planet like our Earth—not too hot and not too cold, not too dry and not too wet—has formed, what chemistry must develop to yield the building blocks of life? In the 1950s the iconic Miller-Urey experiment, which zapped a mixture of water and simple chemicals with electric pulses (to simulate the impact of lightning), demonstrated that amino acids, the building blocks of proteins, are easy to make. Other molecules of life turned out to be harder to synthesize, however, and it is now apparent that we need to completely reimagine the path from chemistry to life. The central reason hinges on the versatility of RNA, a very long molecule that plays a multitude of essential roles in all existing forms of life. RNA can not only act like an enzyme but also store and transmit information. Remarkably, all the protein in all organisms is made by the catalytic activity of the RNA component of the ribosome, the cellular machine that reads genetic information and makes protein molecules. This observation suggests that RNA dominated an early stage in the evolution of life.

Read more from this special report:

The Biggest Questions in Science

Today the question of how chemistry on the infant Earth gave rise to RNA and to RNA-based cells is the central question of origin-of-life research. Some scientists think that life originally used simpler molecules and only later evolved RNA. Other researchers, however, are tackling the origin of RNA head-on, and exciting new ideas are revolutionizing this once quiet backwater of chemical research. Favored geochemical scenarios involve volcanic regions or impact craters, with complex organic chemistry, multiple sources of energy, and dynamic light-dark, hot-cold and wet-dry cycles. Strikingly, many of the chemical intermediates on the way to RNA crystallize out of reaction mixtures, self-purifying and potentially accumulating on the early Earth as organic minerals—reservoirs of material waiting to come to life when conditions change.

Assuming that key problem is solved, we will still need to understand how RNA was replicated within the first primitive cells. Researchers are just beginning to identify the sources of chemical energy that could enable the RNA to copy itself, but much remains to be done. If these hurdles can also be overcome, we may be able to build replicating, evolving RNA-based cells in the laboratory—recapitulating a possible route to the origin of life.

What next? Chemists are already asking whether our kind of life can be generated only through a single plausible pathway or whether multiple routes might lead from simple chemistry to RNA-based life and on to modern biology. Others are exploring variations on the chemistry of life, seeking clues as to the possible diversity of life “out there” in the universe. If all goes well, we will eventually learn how robust the transition from chemistry to biology is and therefore whether the universe is full of life-forms or—but for us—sterile.

This article is part of a special report, “The Biggest Questions in Science,” sponsored by The Kavli Prize . It was produced independently by Scientific American and Nature editors, who have sole responsibility for all the editorial content.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- Image & Use Policy

- Translations

UC MUSEUM OF PALEONTOLOGY

Understanding Evolution

Your one-stop source for information on evolution

From soup to cells: The origin of life

- ES en Español

Studying the origin of life

The origin of life might seem like the ultimate cold case: no one was there to observe it and much of the relevant evidence has been lost in the intervening 3.5 billion years or so. Nonetheless, many separate lines of evidence do shed light on this event, and as biologists continue to investigate these data, they are slowly piecing together a picture of how life originated. Major lines of evidence include DNA, biochemistry, and experiments.

Origins and DNA evidence

Biologists use the DNA sequences of modern organisms to reconstruct the tree of life and to figure out the likely characteristics of the most recent common ancestor of all living things — the “trunk” of the tree of life. In fact, according to some hypotheses, this “most recent common ancestor” may actually be a set of organisms that lived at the same time and were able to swap genes easily. In either case, reconstructing the early branches on the tree of life tells us that this ancestor (or set of ancestors) probably used DNA as its genetic material and performed complex chemical reactions. But what came before it? We know that this last common ancestor must have had ancestors of its own – a long line of forebears forming the root of the tree of life – but to learn about them, we must turn to other lines of evidence.

How did life originate?

Origins and biochemical evidence

Subscribe to our newsletter

- Teaching resource database

- Correcting misconceptions

- Conceptual framework and NGSS alignment

- Image and use policy

- Evo in the News

- The Tree Room

- Browse learning resources

7 theories on the origin of life

The answer to the origin of life remains unknown, but here are scientists best bets

- An electric spark

Molecules of life met on clay

- Deep-sea vents

- Born from ice

- Understanding DNA

- Simple beginnings

- Life came from space

Additional resources

Bibliography.

The origin of life on Earth began more than 3 billion years ago, evolving from the most basic of microbes into a dazzling array of complexity over time. But how did the first organisms on the only known home to life in the universe develop from the primordial soup?

Science remains undecided and conflicted as to the exact origin of life, also known as abiogenesis. Even the very definition of life is contested and rewritten, with one study published in the J ournal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics , suggesting uncovering 123 different published definitions.

Although science still seems unsure, here are some of the many different scientific theories on the origin of life on Earth.

It started with an electric spark

Lightning may have provided the spark needed for life to begin.Electric sparks can generate amino acids and sugars from an atmosphere loaded with water, methane, ammonia and hydrogen , as was shown in the famous Miller-Urey experiment in 1952, according to Scientific American . The experiment's findings suggested that lightning might have helped create the key building blocks of life on Earth in its early days. Over millions of years, larger and more complex molecules could form.

Although research since then has revealed the early atmosphere of Earth was actually hydrogen-poor, scientists have suggested that volcanic clouds in the early atmosphere might have held methane, ammonia and hydrogen and been filled with lightning as well, according to the University of California

The first molecules of life might have met on clay, according to an idea elaborated by organic chemist Alexander Graham Cairns-Smith at the University of Glasgow in Scotland. Cairns-Smith proposed in his 1985 controversial book “ Seven Clues to the Origin of Life'' , that clay crystals preserve their structure as they grow and stick together to form areas exposed to different environments and trap other molecules along the way and organise them into patterns much like our genes do now.

– What is the difference between prokaryotic and eukaryotic cells?

– What is biology?

– What are bacteria?

– What is an amoeba?

– Is there water on Mars?

The main role of DNA is to store information on how other molecules should be arranged. Genetic sequences in DNA are essentially instructions on how amino acids should be arranged in proteins. Cairns-Smith suggests that mineral crystals in clay could have arranged organic molecules into organized patterns. After a while, organic molecules took over this job and organized themselves.

Although Cairns-Smith's theory certainly gave scientists food for thought in the 1980s, it has still not been widely accepted by the scientific community.

Life began at deep-sea vents

The deep-sea vent theory suggests that life may have begun at submarine hydrothermal vents spewing elements key to life, such as carbon and hydrogen-, according to the journal Nature Reviews Microbiology .

Hydrothermal vents can be found in the darkest depths of the ocean floors, typically on diverging continental plates, according to the Natural History Museum . These vents erupt fluid which is superheated by the Earth’s core as it passes up through the crust, before being ejected at the vets. During its journey through the crust it collects dissolved gases and minerals, such as carbon and hydrogen.

Their rocky nooks could then have concentrated these molecules together and provided mineral catalysts for critical reactions. Even now, these vents, rich in chemical and thermal energy, sustain vibrant ecosystems.

Abiogenesis by way of hydrothermal vents continues to be investigated as a plausible cause of life on Earth. In 2019, scientists at University College London , successfully created protocells (non-living structures that help scientists understand the origins of life) under similar hot, alkaline environmental conditions to hydrothermal vents.

Life had a chilly start

Ice might have covered the oceans 3 billion years ago and facilitated the birth of life. "Key organic compounds thought to be important in the origin of life are more stable at lower temperatures,” Jeffrey Bada at the University of California, told New Scientist . At normal temperatures these compounds, such as simple sets of amino acids, are sparsely populated in water, but when frozen become concentrated and facilitate the emergence of life, according to Bada’s work published in the journal I carus .

Ice also might have protected fragile organic compounds in the water below from ultraviolet light and destruction from cosmic impacts. The cold might have also helped these molecules to survive longer, enabling key reactions to happen.

The answer lies in understanding DNA formation

Nowadays DNA needs proteins in order to form, and proteins require DNA to form, so how could these have formed without each other? The answer may be RNA , which can store information like DNA, serve as an enzyme like proteins, and help create both DNA and proteins, according to the journal Molecular Biology of the Cell . Later DNA and proteins succeeded this "RNA world," because they are more efficient.

RNA still exists and performs several functions in organisms, including acting as an on-off switch for some genes. The question still remains how RNA got here in the first place. Some scientists think the molecule could have spontaneously arisen on Earth, while others say that was very unlikely to have happened.

Life had simple beginnings

Instead of developing from complex molecules such as RNA, life might have begun with smaller molecules interacting with each other in cycles of reactions. These might have been contained in simple capsules akin to cell membranes, and over time more complex molecules that performed these reactions better than the smaller ones could have evolved, scenarios dubbed "metabolism-first" models, as opposed to the "gene-first" model of the "RNA world" hypothesis.

Life was brought here from elsewhere in space

Perhaps life did not begin on Earth at all, but was brought here from elsewhere in space, a notion known as panspermia, according to NASA . For instance, rocks regularly get blasted off Mars by cosmic impacts, and a number of Martian meteorites have been found on Earth that some researchers have controversially suggested brought microbes over here, potentially making us all Martians originally. Other scientists have even suggested that life might have hitchhiked on comets from other star systems. However, even if this concept were true, the question of how life began on Earth would then only change to how life began elsewhere in space.

For more information into the theories of life’s origins check out “ The Stairway To Life: An Origin-Of-Life Reality Check ” by Change Laura Tan and “ The Mystery of Life's Origin ” by Charles B. Thaxton, et al.

Matthew Levy et al, “Prebiotic Synthesis of Adenine and Amino Acids Under Europa-like Conditions”, Icarus, Volume 145, June 2000, https://doi.org/10.1006/icar.2000.6365

William Martin, “Hydrothermal vents and the origin of life”, Nature Reviews Microbiology, Volume 6, September 2008, https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro1991

K. A. Dill and L. Agozzino, “Driving forces in the origins of life”, Open biology, Volume 11, February 2021, ttps://doi.org/10.1098/rsob.200324

Ben K. D. Pearce et al, “Origin of the RNA world: The fate of nucleobases in warm little ponds”, PNAS, Volume 114, October 2017, https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1710339114

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Y chromosome is evolving faster than the X, primate study reveals

Why don't humans have gills?

Is Jupiter's Great Red Spot an impostor? Giant storm may not be the original one discovered 350 years ago

Most Popular

- 2 Strawberry Moon 2024: See summer's first full moon rise a day after solstice

- 3 Y chromosome is evolving faster than the X, primate study reveals

- 4 Ming dynasty shipwrecks hide a treasure trove of artifacts in the South China Sea, excavation reveals

- 5 The 2024 summer solstice will be the earliest for 228 years. Here's why.

- 2 If birds are dinosaurs, why aren't they cold-blooded?

- 3 Jaguarundi: The little wildcat that looks like an otter and has 13 ways of 'talking'

- 4 The Hope Diamond: The 'cursed' blue gemstone coveted by royalty

- 5 Astronauts stranded in space due to multiple issues with Boeing's Starliner — and the window for a return flight is closing

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Meaning of Life

Many major historical figures in philosophy have provided an answer to the question of what, if anything, makes life meaningful, although they typically have not put it in these terms (with such talk having arisen only in the past 250 years or so, on which see Landau 1997). Consider, for instance, Aristotle on the human function, Aquinas on the beatific vision, and Kant on the highest good. Relatedly, think about Koheleth, the presumed author of the Biblical book Ecclesiastes, describing life as “futility” and akin to “the pursuit of wind,” Nietzsche on nihilism, as well as Schopenhauer when he remarks that whenever we reach a goal we have longed for we discover “how vain and empty it is.” While these concepts have some bearing on happiness and virtue (and their opposites), they are straightforwardly construed (roughly) as accounts of which highly ranked purposes a person ought to realize that would make her life significant (if any would).

Despite the venerable pedigree, it is only since the 1980s or so that a distinct field of the meaning of life has been established in Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy, on which this survey focuses, and it is only in the past 20 years that debate with real depth and intricacy has appeared. Two decades ago analytic reflection on life’s meaning was described as a “backwater” compared to that on well-being or good character, and it was possible to cite nearly all the literature in a given critical discussion of the field (Metz 2002). Neither is true any longer. Anglo-American-Australasian philosophy of life’s meaning has become vibrant, such that there is now way too much literature to be able to cite comprehensively in this survey. To obtain focus, it tends to discuss books, influential essays, and more recent works, and it leaves aside contributions from other philosophical traditions (such as the Continental or African) and from non-philosophical fields (e.g., psychology or literature). This survey’s central aim is to acquaint the reader with current analytic approaches to life’s meaning, sketching major debates and pointing out neglected topics that merit further consideration.

When the topic of the meaning of life comes up, people tend to pose one of three questions: “What are you talking about?”, “What is the meaning of life?”, and “Is life in fact meaningful?”. The literature on life's meaning composed by those working in the analytic tradition (on which this entry focuses) can be usefully organized according to which question it seeks to answer. This survey starts off with recent work that addresses the first, abstract (or “meta”) question regarding the sense of talk of “life’s meaning,” i.e., that aims to clarify what we have in mind when inquiring into the meaning of life (section 1). Afterward, it considers texts that provide answers to the more substantive question about the nature of meaningfulness (sections 2–3). There is in the making a sub-field of applied meaning that parallels applied ethics, in which meaningfulness is considered in the context of particular cases or specific themes. Examples include downshifting (Levy 2005), implementing genetic enhancements (Agar 2013), making achievements (Bradford 2015), getting an education (Schinkel et al. 2015), interacting with research participants (Olson 2016), automating labor (Danaher 2017), and creating children (Ferracioli 2018). In contrast, this survey focuses nearly exclusively on contemporary normative-theoretical approaches to life’s meanining, that is, attempts to capture in a single, general principle all the variegated conditions that could confer meaning on life. Finally, this survey examines fresh arguments for the nihilist view that the conditions necessary for a meaningful life do not obtain for any of us, i.e., that all our lives are meaningless (section 4).

1. The Meaning of “Meaning”

2.1. god-centered views, 2.2. soul-centered views, 3.1. subjectivism, 3.2. objectivism, 3.3. rejecting god and a soul, 4. nihilism, works cited, classic works, collections, books for the general reader, other internet resources, related entries.

One of the field's aims consists of the systematic attempt to identify what people (essentially or characteristically) have in mind when they think about the topic of life’s meaning. For many in the field, terms such as “importance” and “significance” are synonyms of “meaningfulness” and so are insufficiently revealing, but there are those who draw a distinction between meaningfulness and significance (Singer 1996, 112–18; Belliotti 2019, 145–50, 186). There is also debate about how the concept of a meaningless life relates to the ideas of a life that is absurd (Nagel 1970, 1986, 214–23; Feinberg 1980; Belliotti 2019), futile (Trisel 2002), and not worth living (Landau 2017, 12–15; Matheson 2017).

A useful way to begin to get clear about what thinking about life’s meaning involves is to specify the bearer. Which life does the inquirer have in mind? A standard distinction to draw is between the meaning “in” life, where a human person is what can exhibit meaning, and the meaning “of” life in a narrow sense, where the human species as a whole is what can be meaningful or not. There has also been a bit of recent consideration of whether animals or human infants can have meaning in their lives, with most rejecting that possibility (e.g., Wong 2008, 131, 147; Fischer 2019, 1–24), but a handful of others beginning to make a case for it (Purves and Delon 2018; Thomas 2018). Also under-explored is the issue of whether groups, such as a people or an organization, can be bearers of meaning, and, if so, under what conditions.

Most analytic philosophers have been interested in meaning in life, that is, in the meaningfulness that a person’s life could exhibit, with comparatively few these days addressing the meaning of life in the narrow sense. Even those who believe that God is or would be central to life’s meaning have lately addressed how an individual’s life might be meaningful in virtue of God more often than how the human race might be. Although some have argued that the meaningfulness of human life as such merits inquiry to no less a degree (if not more) than the meaning in a life (Seachris 2013; Tartaglia 2015; cf. Trisel 2016), a large majority of the field has instead been interested in whether their lives as individual persons (and the lives of those they care about) are meaningful and how they could become more so.

Focusing on meaning in life, it is quite common to maintain that it is conceptually something good for its own sake or, relatedly, something that provides a basic reason for action (on which see Visak 2017). There are a few who have recently suggested otherwise, maintaining that there can be neutral or even undesirable kinds of meaning in a person’s life (e.g., Mawson 2016, 90, 193; Thomas 2018, 291, 294). However, these are outliers, with most analytic philosophers, and presumably laypeople, instead wanting to know when an individual’s life exhibits a certain kind of final value (or non-instrumental reason for action).

Another claim about which there is substantial consensus is that meaningfulness is not all or nothing and instead comes in degrees, such that some periods of life are more meaningful than others and that some lives as a whole are more meaningful than others. Note that one can coherently hold the view that some people’s lives are less meaningful (or even in a certain sense less “important”) than others, or are even meaningless (unimportant), and still maintain that people have an equal standing from a moral point of view. Consider a consequentialist moral principle according to which each individual counts for one in virtue of having a capacity for a meaningful life, or a Kantian approach according to which all people have a dignity in virtue of their capacity for autonomous decision-making, where meaning is a function of the exercise of this capacity. For both moral outlooks, we could be required to help people with relatively meaningless lives.

Yet another relatively uncontroversial element of the concept of meaningfulness in respect of individual persons is that it is logically distinct from happiness or rightness (emphasized in Wolf 2010, 2016). First, to ask whether someone’s life is meaningful is not one and the same as asking whether her life is pleasant or she is subjectively well off. A life in an experience machine or virtual reality device would surely be a happy one, but very few take it to be a prima facie candidate for meaningfulness (Nozick 1974: 42–45). Indeed, a number would say that one’s life logically could become meaningful precisely by sacrificing one’s well-being, e.g., by helping others at the expense of one’s self-interest. Second, asking whether a person’s existence over time is meaningful is not identical to considering whether she has been morally upright; there are intuitively ways to enhance meaning that have nothing to do with right action or moral virtue, such as making a scientific discovery or becoming an excellent dancer. Now, one might argue that a life would be meaningless if, or even because, it were unhappy or immoral, but that would be to posit a synthetic, substantive relationship between the concepts, far from indicating that speaking of “meaningfulness” is analytically a matter of connoting ideas regarding happiness or rightness. The question of what (if anything) makes a person’s life meaningful is conceptually distinct from the questions of what makes a life happy or moral, although it could turn out that the best answer to the former question appeals to an answer to one of the latter questions.

Supposing, then, that talk of “meaning in life” connotes something good for its own sake that can come in degrees and that is not analytically equivalent to happiness or rightness, what else does it involve? What more can we say about this final value, by definition? Most contemporary analytic philosophers would say that the relevant value is absent from spending time in an experience machine (but see Goetz 2012 for a different view) or living akin to Sisyphus, the mythic figure doomed by the Greek gods to roll a stone up a hill for eternity (famously discussed by Albert Camus and Taylor 1970). In addition, many would say that the relevant value is typified by the classic triad of “the good, the true, and the beautiful” (or would be under certain conditions). These terms are not to be taken literally, but instead are rough catchwords for beneficent relationships (love, collegiality, morality), intellectual reflection (wisdom, education, discoveries), and creativity (particularly the arts, but also potentially things like humor or gardening).

Pressing further, is there something that the values of the good, the true, the beautiful, and any other logically possible sources of meaning involve? There is as yet no consensus in the field. One salient view is that the concept of meaning in life is a cluster or amalgam of overlapping ideas, such as fulfilling higher-order purposes, meriting substantial esteem or admiration, having a noteworthy impact, transcending one’s animal nature, making sense, or exhibiting a compelling life-story (Markus 2003; Thomson 2003; Metz 2013, 24–35; Seachris 2013, 3–4; Mawson 2016). However, there are philosophers who maintain that something much more monistic is true of the concept, so that (nearly) all thought about meaningfulness in a person’s life is essentially about a single property. Suggestions include being devoted to or in awe of qualitatively superior goods (Taylor 1989, 3–24), transcending one’s limits (Levy 2005), or making a contribution (Martela 2016).

Recently there has been something of an “interpretive turn” in the field, one instance of which is the strong view that meaning-talk is logically about whether and how a life is intelligible within a wider frame of reference (Goldman 2018, 116–29; Seachris 2019; Thomas 2019; cf. Repp 2018). According to this approach, inquiring into life’s meaning is nothing other than seeking out sense-making information, perhaps a narrative about life or an explanation of its source and destiny. This analysis has the advantage of promising to unify a wide array of uses of the term “meaning.” However, it has the disadvantages of being unable to capture the intuitions that meaning in life is essentially good for its own sake (Landau 2017, 12–15), that it is not logically contradictory to maintain that an ineffable condition is what confers meaning on life (as per Cooper 2003, 126–42; Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014), and that often human actions themselves (as distinct from an interpretation of them), such as rescuing a child from a burning building, are what bear meaning.

Some thinkers have suggested that a complete analysis of the concept of life’s meaning should include what has been called “anti-matter” (Metz 2002, 805–07, 2013, 63–65, 71–73) or “anti-meaning” (Campbell and Nyholm 2015; Egerstrom 2015), conditions that reduce the meaningfulness of a life. The thought is that meaning is well represented by a bipolar scale, where there is a dimension of not merely positive conditions, but also negative ones. Gratuitous cruelty or destructiveness are prima facie candidates for actions that not merely fail to add meaning, but also subtract from any meaning one’s life might have had.

Despite the ongoing debates about how to analyze the concept of life’s meaning (or articulate the definition of the phrase “meaning in life”), the field remains in a good position to make progress on the other key questions posed above, viz., of what would make a life meaningful and whether any lives are in fact meaningful. A certain amount of common ground is provided by the point that meaningfulness at least involves a gradient final value in a person’s life that is conceptually distinct from happiness and rightness, with exemplars of it potentially being the good, the true, and the beautiful. The rest of this discussion addresses philosophical attempts to capture the nature of this value theoretically and to ascertain whether it exists in at least some of our lives.

2. Supernaturalism

Most analytic philosophers writing on meaning in life have been trying to develop and evaluate theories, i.e., fundamental and general principles, that are meant to capture all the particular ways that a life could obtain meaning. As in moral philosophy, there are recognizable “anti-theorists,” i.e., those who maintain that there is too much pluralism among meaning conditions to be able to unify them in the form of a principle (e.g., Kekes 2000; Hosseini 2015). Arguably, though, the systematic search for unity is too nascent to be able to draw a firm conclusion about whether it is available.

The theories are standardly divided on a metaphysical basis, that is, in terms of which kinds of properties are held to constitute the meaning. Supernaturalist theories are views according to which a spiritual realm is central to meaning in life. Most Western philosophers have conceived of the spiritual in terms of God or a soul as commonly understood in the Abrahamic faiths (but see Mulgan 2015 for discussion of meaning in the context of a God uninterested in us). In contrast, naturalist theories are views that the physical world as known particularly well by the scientific method is central to life’s meaning.

There is logical space for a non-naturalist theory, according to which central to meaning is an abstract property that is neither spiritual nor physical. However, only scant attention has been paid to this possibility in the recent Anglo-American-Australasian literature (Audi 2005).

It is important to note that supernaturalism, a claim that God (or a soul) would confer meaning on a life, is logically distinct from theism, the claim that God (or a soul) exists. Although most who hold supernaturalism also hold theism, one could accept the former without the latter (as Camus more or less did), committing one to the view that life is meaningless or at least lacks substantial meaning. Similarly, while most naturalists are atheists, it is not contradictory to maintain that God exists but has nothing to do with meaning in life or perhaps even detracts from it. Although these combinations of positions are logically possible, some of them might be substantively implausible. The field could benefit from discussion of the comparative attractiveness of various combinations of evaluative claims about what would make life meaningful and metaphysical claims about whether spiritual conditions exist.

Over the past 15 years or so, two different types of supernaturalism have become distinguished on a regular basis (Metz 2019). That is true not only in the literature on life’s meaning, but also in that on the related pro-theism/anti-theism debate, about whether it would be desirable for God or a soul to exist (e.g., Kahane 2011; Kraay 2018; Lougheed 2020). On the one hand, there is extreme supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for any meaning in life. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life is meaningless. On the other hand, there is moderate supernaturalism, according to which spiritual conditions are necessary for a great or ultimate meaning in life, although not meaning in life as such. If neither God nor a soul exists, then, by this view, everyone’s life could have some meaning, or even be meaningful, but no one’s life could exhibit the most desirable meaning. For a moderate supernaturalist, God or a soul would substantially enhance meaningfulness or be a major contributory condition for it.

There are a variety of ways that great or ultimate meaning has been described, sometimes quantitatively as “infinite” (Mawson 2016), qualitatively as “deeper” (Swinburne 2016), relationally as “unlimited” (Nozick 1981, 618–19; cf. Waghorn 2014), temporally as “eternal” (Cottingham 2016), and perspectivally as “from the point of view of the universe” (Benatar 2017). There has been no reflection as yet on the crucial question of how these distinctions might bear on each another, for instance, on whether some are more basic than others or some are more valuable than others.

Cross-cutting the extreme/moderate distinction is one between God-centered theories and soul-centered ones. According to the former, some kind of connection with God (understood to be a spiritual person who is all-knowing, all-good, and all-powerful and who is the ground of the physical universe) constitutes meaning in life, even if one lacks a soul (construed as an immortal, spiritual substance that contains one’s identity). In contrast, by the latter, having a soul and putting it into a certain state is what makes life meaningful, even if God does not exist. Many supernaturalists of course believe that God and a soul are jointly necessary for a (greatly) meaningful existence. However, the simpler view, that only one of them is necessary, is common, and sometimes arguments proffered for the complex view fail to support it any more than the simpler one.

The most influential God-based account of meaning in life has been the extreme view that one’s existence is significant if and only if one fulfills a purpose God has assigned. The familiar idea is that God has a plan for the universe and that one’s life is meaningful just to the degree that one helps God realize this plan, perhaps in a particular way that God wants one to do so. If a person failed to do what God intends her to do with her life (or if God does not even exist), then, on the current view, her life would be meaningless.

Thinkers differ over what it is about God’s purpose that might make it uniquely able to confer meaning on human lives, but the most influential argument has been that only God’s purpose could be the source of invariant moral rules (Davis 1987, 296, 304–05; Moreland 1987, 124–29; Craig 1994/2013, 161–67) or of objective values more generally (Cottingham 2005, 37–57), where a lack of such would render our lives nonsensical. According to this argument, lower goods such as animal pleasure or desire satisfaction could exist without God, but higher ones pertaining to meaning in life, particularly moral virtue, could not. However, critics point to many non-moral sources of meaning in life (e.g., Kekes 2000; Wolf 2010), with one arguing that a universal moral code is not necessary for meaning in life, even if, say, beneficent actions are (Ellin 1995, 327). In addition, there are a variety of naturalist and non-naturalist accounts of objective morality––and of value more generally––on offer these days, so that it is not clear that it must have a supernatural source in God’s will.

One recurrent objection to the idea that God’s purpose could make life meaningful is that if God had created us with a purpose in mind, then God would have degraded us and thereby undercut the possibility of us obtaining meaning from fulfilling the purpose. The objection harks back to Jean-Paul Sartre, but in the analytic literature it appears that Kurt Baier was the first to articulate it (1957/2000, 118–20; see also Murphy 1982, 14–15; Singer 1996, 29; Kahane 2011; Lougheed 2020, 121–41). Sometimes the concern is the threat of punishment God would make so that we do God’s bidding, while other times it is that the source of meaning would be constrictive and not up to us, and still other times it is that our dignity would be maligned simply by having been created with a certain end in mind (for some replies to such concerns, see Hanfling 1987, 45–46; Cottingham 2005, 37–57; Lougheed 2020, 111–21).

There is a different argument for an extreme God-based view that focuses less on God as purposive and more on God as infinite, unlimited, or ineffable, which Robert Nozick first articulated with care (Nozick 1981, 594–618; see also Bennett-Hunter 2014; Waghorn 2014). The core idea is that for a finite condition to be meaningful, it must obtain its meaning from another condition that has meaning. So, if one’s life is meaningful, it might be so in virtue of being married to a person, who is important. Being finite, the spouse must obtain his or her importance from elsewhere, perhaps from the sort of work he or she does. This work also must obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is meaningful, and so on. A regress on meaningful conditions is present, and the suggestion is that the regress can terminate only in something so all-encompassing that it need not (indeed, cannot) go beyond itself to obtain meaning from anything else. And that is God. The standard objection to this relational rationale is that a finite condition could be meaningful without obtaining its meaning from another meaningful condition. Perhaps it could be meaningful in itself, without being connected to something beyond it, or maybe it could obtain its meaning by being related to something else that is beautiful or otherwise valuable for its own sake but not meaningful (Nozick 1989, 167–68; Thomson 2003, 25–26, 48).

A serious concern for any extreme God-based view is the existence of apparent counterexamples. If we think of the stereotypical lives of Albert Einstein, Mother Teresa, and Pablo Picasso, they seem meaningful even if we suppose there is no all-knowing, all-powerful, and all-good spiritual person who is the ground of the physical world (e.g., Wielenberg 2005, 31–37, 49–50; Landau 2017). Even religiously inclined philosophers have found this hard to deny these days (Quinn 2000, 58; Audi 2005; Mawson 2016, 5; Williams 2020, 132–34).