- A Beginner’s Guide to IELTS

- Common Grammar Mistakes [for IELTS Writing Candidates]

Writing Correction Service

- Free IELTS Resources

- Practice Speaking Test

Select Page

Government Spending Essays – IELTS Writing

Posted by David S. Wills | Feb 21, 2022 | IELTS Tips , Writing | 0

In IELTS writing task 2, it is quite common to be asked about how governments should spend their money. In fact, I see this so frequently that it is almost a unique topic!

Today, I want to show you a few essays about government spending, looking at some sample answers and language points so that you can better understand how to approach this sort of essay.

Government Spending Essays for Task 2

First of all, let’s look at three IELTS task 2 questions that deal with government spending:

The prevention of health problems and illness is more important than treatment and medicine. Government funding should reflect this. To what extent do you agree?

The world today is a safer place than it was a hundred years ago, and governments should stop spending large amounts of money on their armed forces. To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement?

The restoration of old buildings in major cities around the world causes enormous government expenditure. This money should be used for new housing and road development. To what extent do you agree or disagree?

The first question is about how governments should spend money on healthcare , the second is about whether or not they should spend money for military purposes , and the third is about maintaining old building s. As you can see, then, the issue of government funding could be applied to a range of areas.

Also, note the different words and phrases used to introduce the idea of government spending. In the first, it is “government funding,” in the second, “spending” is a verb,” and in the third, it says “government expenditure.”

Vocabulary about Government Spending

When it comes to the topic of government spending, you obviously need to be able to discuss money and specifically large amounts of money. You need to know words and phrases related to government expenditure. Here are some useful ones:

All of these words and phrases will be used in my sample answers below.

You can also see some money idioms here:

When it comes to money verbs, don’t forget that we need to collocate them with certain prepositions. Typically, we say “spend money on”, “invest money in,” or “allocate money for”. There are other common collocations as well. Here are a few examples:

- He spent his birthday money on a new pair of shoes.

- She spent most of her budget on building a social media following.

- We’re going to invest in Apple.

- They invested too much money in that doomed project.

- We saved money on our gas bill by switching providers.

Finally, be careful with the word “budget.” This is one word that I see misused very frequently in IELTS essays. Here is a visual lesson about it, which I posted on Facebook .

You can learn more money vocabulary and also look at some IELTS speaking questions about money in this lesson .

Sample Answers

Ok, now let’s look at my answers to the above questions. These contain the vocabulary I taught you. Take note of how those words and phrases are used.

Essay #1: Government Spending on Healthcare

The prevention of health problems and illness is more important than treatment and medicine. Government funding should reflect this.

To what extent do you agree?

In many countries, government spending on healthcare is a major economic burden. Problems like obesity and heart disease are crippling healthcare systems, and some people suggest that rather than raise taxes to pay for treatments, more money should be invested in preventing these illnesses in the first place. This essay will argue that prevention is better than treatment.

The most obvious benefit of putting prevention before treatment is the reduction in human suffering that would inevitably result. Some of the biggest health problems in modern societies are utterly preventable, and therefore it is reasonable to suggest that money spent this way would cause less anguish. Government campaigns to reduce smoking would reduce cancer rates and this would increase people’s quality of life, and of course end the suffering of people who lose loved ones.

From a purely financial standpoint, it is beneficial to focus on preventing sickness rather than curing it. The cost of treating sick people with expensive medical procedures, equipment, and medicines is vastly higher than the cost of educating people not to smoke, eat unhealthily, or otherwise lead unhealthy lifestyles. Government campaigns have led to huge decreases in smoking in many Western countries, and it is likely that similar campaigns would yield similar results elsewhere. An additional benefit would be the lowering of taxes due to reduced expenditure on healthcare.

In conclusion, preventing a disease makes more sense than waiting to treat it. The benefits to average people and also to governments are significantly higher than simply investing in treatments.

Essay #2: Government Spending on Military

The world today is a safer place than it was a hundred years ago, and governments should stop spending large amounts of money on their armed forces.

To what extent do you agree or disagree with this statement?

In many developed countries, people discuss the ethics of government spending on military forces, with many people pointing out that it is wasteful. This essay will suggest that they are probably right, but that it is a more complicated situation than they think.

To begin with, it is clear that some countries spend vast sums of money on their militaries when there are many other problems that could be tackled using that money. Between the USA and China, for example, more than $1 trillion is spent per year on equipping their various armed forces and this money could potentially have been invested into protecting the environment, ending homelessness and hunger, or improving education systems. Given that these two nations are highly unlikely to be attacked by any other, it seems absurd that they invest so much money in this way.

However, all of that overlooks the fact that geopolitics is complicated and human nature has some dark elements. Although people live in an unprecedented era of peace, it is nonetheless true that this peace is not guaranteed and that it is predicated to some extent upon the fear of reprisals. The US may seem incredibly wasteful with its military spending, but if it did not maintain such a huge military, other aggressive nations would surely attack their neighbours. They are dissuaded of this by the threat of American intervention. Whilst this is highly problematic as no single country should function as a “world police,” it has certainly helped deter and even end major conflicts over the past half century.

In conclusion, it is not easy to say whether countries should stop spending so much money on their militaries. Indeed, whilst it appears this is a reasonable suggestion, the truth is more complicated.

Essay #3: Government Spending on Old Buildings

The restoration of old buildings in major cities around the world causes enormous government expenditure. This money should be used for new housing and road development.

To what extent do you agree or disagree?

Government spending is a highly controversial issue because people naturally have different priorities and beliefs. Some of them think that the money spent on the restoration of old buildings is wasteful, but this essay will argue against that notion, suggesting instead that these are essential pieces of a nation’s heritage.

To begin with, it is understandable that people might feel this way because there are numerous ways that a national budget might be spent, and old buildings are probably not high on most people’s lists. However, not everything that is important is obvious and often people do not realise the value of something until it is gone. Around Asia, for example, many countries underwent the same sort of industrial development in just two or three decades that Europe went through over a period of several centuries. As a result, these countries lost most of their ancient buildings, and these cannot be recovered. Many governments fund the construction of replicas, but these obviously lack the authenticity of truly ancient buildings.

Letting these buildings fall into ruin shows a staggering lack of civic pride. Cities and countries must unite to fund the maintenance of important shared spaces, including these historic sites. Without these places, cities begin to look unremarkable and it is hard to tell one place from another. Whilst it is important to devote spending to new projects, governments must not overlook the heritage aspect that defined their city or country over a long period of time, and which continues to mark it in the modern era.

In conclusion, old buildings may seem like a waste of money because they can be expensive to maintain, but they are important in various ways, and so governments should set aside funding to ensure their upkeep.

About The Author

David S. Wills

David S. Wills is the author of Scientologist! William S. Burroughs and the 'Weird Cult' and the founder/editor of Beatdom literary journal. He lives and works in rural Cambodia and loves to travel. He has worked as an IELTS tutor since 2010, has completed both TEFL and CELTA courses, and has a certificate from Cambridge for Teaching Writing. David has worked in many different countries, and for several years designed a writing course for the University of Worcester. In 2018, he wrote the popular IELTS handbook, Grammar for IELTS Writing and he has since written two other books about IELTS. His other IELTS website is called IELTS Teaching.

Related Posts

The Road to IELTS Success

January 25, 2019

Building and Structure Vocabulary for IELTS

June 12, 2017

Describe a Person You Know Who Dresses Well

June 13, 2022

Some Tips for IELTS Writing Task 1

June 29, 2017

Leave a reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Download my IELTS Books

Recent Posts

- British vs American Spelling

- How to Improve your IELTS Writing Score

- Past Simple vs Past Perfect

- Complex Sentences

- How to Score Band 9 [Video Lesson]

Recent Comments

- Francisca on Adverb Clauses: A Comprehensive Guide

- Mariam on IELTS Writing Task 2: Two-Part Questions

- abdelhadi skini on Subordinating Conjunction vs Conjunctive Adverb

- David S. Wills on How to Describe Tables for IELTS Writing Task 1

- anonymous on How to Describe Tables for IELTS Writing Task 1

- Lesson Plans

- Model Essays

- TED Video Lessons

- Weekly Roundup

Government Spending

What do governments spend their financial resources on?

By: Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

This page was first published in October 16 and last revised in March 2023.

Public spending enables governments to produce and purchase goods and services, in order to fulfill their objectives – such as the provision of public goods or the redistribution of resources. In this topic page we study public spending through the lens of aggregate cross-country data on government expenditures. We begin with an analysis of historical trends and then move on to analyze recent developments in public spending patterns around the world.

The available long-run data shows that the role and size of governments around the world have changed drastically in the last couple of centuries. In early-industrialized countries, specifically, the historical data shows that public spending increased remarkably in the 20th century , as governments started spending more resources on social protection, education, and healthcare.

Recent data on public spending reveals substantial differences across countries. Relative to low-income countries, government expenditure in high-income countries tends to be much larger (both in per capita terms, and as a share of GDP), and it also tends to be more focused on social protection .

Recent data on public spending also shows that governments around the world often rely on the private sector to produce and manage goods and services . And public-private partnerships (PPP), in particular, have become an increasingly popular mechanism for governments to finance, design, build, and operate infrastructure projects. In the period 2005-2010 alone, the total value of PPP projects in low and middle-income countries more than doubled .

Other research and writing on government spending on Our World in Data:

- Healthcare Spending

- Education Spending

Related topics

Military Personnel and Spending

How large are countries’ militaries? How much do they spend on their armed forces? Explore global data on military personnel and spending.

State Capacity

Do governments worldwide have the ability to implement their policies? How is this changing over time? Explore research and data on state capacity.

How common is corruption? What impact does it have? And what can be done to reduce it?

See all interactive charts on government spending ↓

History of government spending

Government spending in early-industrialised countries grew remarkably during the last century.

The visualization shows the evolution of government expenditure as a share of national income, for a selection of countries over the last century. The source of the data is Mauro et al. (2015). 1

If we focus on early-industrialized countries, we can see that there are four broad periods in this chart. In the first period, until the First World War, spending was generally low. These low levels of public spending were just enough for governments to be concerned with basic functions, such as maintaining order and enforcing property rights.

In the second period, between 1915 and 1945, public spending was generally volatile, particularly for countries that were more heavily involved in the First and Second World Wars. Government expenditures as a share of national output went sharply up and down in these countries, mainly because of changes in defense spending and national incomes.

In the third period, between 1945 and 1980, public spending grew particularly fast. As we show in more detail later, this was the result of growth in social spending ; and was largely made possible by historical increases in government revenues over the same period .

Since 1980 the growth of government expenditure has been slowing down in early-industrialized countries – and in some cases, it has gone down in relative terms. However, in spite of differences in levels, in all these countries public spending as a share of GDP is higher today than before the Second World War.

Although the increase in public spending has not been equal in all countries, it is still remarkable that growth has been a general phenomenon, despite large underlying institutional differences.

At the end of the 19th century, European countries spent less than 10% of GDP via the government. In the 21st century, this figure is around 50% in many European countries. The increase in absolute terms – rather than the shown relative terms – is much larger since the level of GDP per capita increased very substantially over this period.

Public spending growth in early-industrialised countries was largely driven by social spending

The visualization above shows that government spending in early-industrialized countries grew substantially in the 20th century. The next visualization shows that this was the result of growth specifically in social spending.

The steep growth of social spending in the second half of the 20th century was largely driven by the expansion of public funding for healthcare and education .

Government spending across the world

Total government spending.

The next visualization maps recent estimates of central government expenditure, as a share of national incomes, across the world. The data is published as part of the World Development Indicators and comes from the IMF.

The most striking feature in the chart is the degree of heterogeneity between world regions. Central governments in high-income countries – particularly those in Europe – tend to control a much larger share of national production than governments in low-income countries.

Countries like France spend multiple times as much as countries like Ethiopia.

These estimates have to be interpreted with caution, since central government expenditure provides a somewhat distorted picture of total public spending, particularly in federal countries with large sub-national governments.

Spending per person

The visualization shows total public expenditure per capita, across all levels of government. To allow for cross-country comparability, these estimates are expressed in current PPP US dollars .

As we can see, cross-country differences are also large here. In India, the government spends a fraction per person than countries like Norway.

Composition of government expenditure

Governments differ substantially not only in size but also in priorities.

The visualizations above show that governments around the world differ considerably in size, even after controlling for underlying differences in economic activity and population. Here we show that governments also differ substantially in terms of how they prioritize expenditures.

The visualization shows the share of government expenditure that is specifically allocated to education.

As we can see, there are large and persistent differences, even within developing countries. The education spending in some developing countries makes up twice or three times the spending in others.

The proportion of government spending that goes towards social protection varies substantially across OECD countries

We have already pointed out that governments in high-income countries spend more resources than governments in low-income countries, both in per capita terms and as a share of their national incomes.

More so, high-income countries also have higher levels of social spending than countries with lower average incomes. 2

The chart here shows social protection expenditures as a share of total general government spending, across different OECD countries. As we can see, there are also large differences across OECD countries themselves.

How do OECD countries distribute their allocations to social spending?

In the chart here we see the allocation of public spending (given as the percentage of a country's GDP) across a range of 'social spending' branches. Note that you can change which country is shown.

Although there are some differences across countries in how social expenditure is distributed, the three priorities are predominantly the same across the OECD. Old age expenditure (in the form of pensions and elderly care) typically receives the largest allocation of social spending, followed by health, with either family or incapacity-related benefits typically coming in third.

The relative importance of these branches has remained largely constant since 1980.

Employee compensation accounts for a large share of public spending in many low-income countries

The next visualization shows the share of central government expenditure that goes to the compensation of government employees. Compensation of employees includes all salaries and benefits (both in cash and in-kind).

As we can see, the salaries of public servants and other government employees are an important component of public spending in most countries. Yet differences between countries are very large.

Throughout Europe, the share of government spending that is devoted to the compensation of government employees ranges between 5% and 15%. In contrast, throughout most of Africa, the available figures range between 30% and 50%.

Public procurement

Procurement plays an important role in government expenditure.

Governments around the world often rely on the private sector to produce and manage goods and services. The process through which governments purchase works, goods, and services from companies, which they have selected for this purpose, is often referred to as 'public procurement.'

The visualization shows the importance of public procurement in OECD countries (and partner countries providing comparable data). It shows the value of total general government procurement as a percentage of GDP.

As we can see, public sector purchases from the private sector are significant in many high-income countries.

Procurement is more than subcontracting large infrastructure projects

Public procurement comprises many different forms of purchases. Public procurement includes, for example, tendering and contracting in order to build large infrastructural projects. However, public procurement goes beyond infrastructure. It also includes, for example, purchases of routine office supplies.

Generally speaking, the part of public procurement that does not fall within the category of gross fixed capital formation (e.g. building new roads), is referred to as 'outsourcing', or 'contracting out'. This form of procurement often relies on short-term contracts.

According to the definitions used by the OECD, outsourcing includes both intermediate goods used by governments (such as procurement of information technology services), or the outsourcing of final goods and services financed by governments (such as social transfers in kind via market producers paid for by governments).

The visualization shows total expenditures on general government outsourcing (accounting for both intermediate and final goods), as a share of GDP.

As we can see, governments in many high-income countries spend substantial resources via outsourcing.

Procurement of infrastructure projects has grown substantially in low and middle-income countries

Public procurement strategies available to governments are varied. Governments may choose to take responsibility for financing, designing, building, and operating infrastructure projects – and they simply outsource specific elements. Or they may choose to pursue a public-private partnership, where private actors directly take responsibility for all these aspects, from financing to operation.

The term 'private finance initiative' is often used to denote a public procurement strategy, whereby governments choose a private firm (or consortium) to construct and operate – and sometimes also finance – public infrastructure. These initiatives typically take the form of long-term contracts. The term 'public-private partnerships' is often used to denote those private finance initiatives where the public sector retains an important participation. More information about terms and classification methodologies can be found in the resources provided by the World Bank's Private Participation in Infrastructure Database (PPID) .

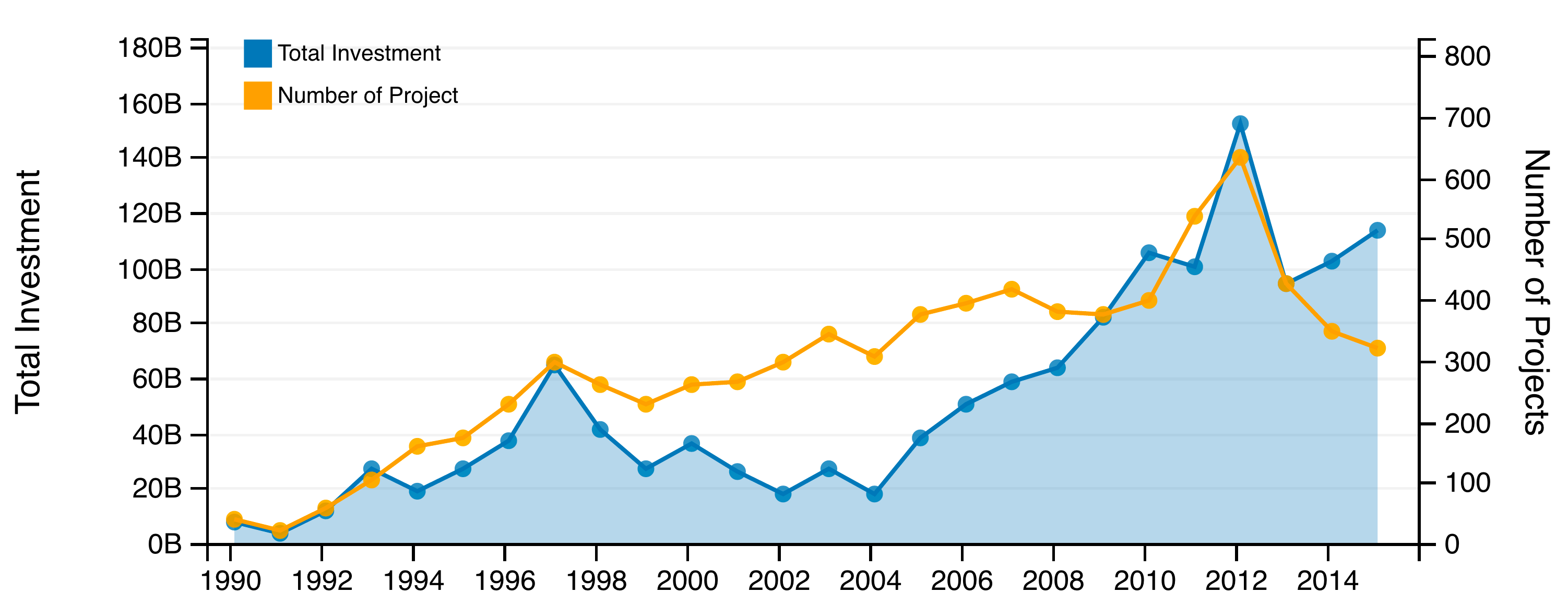

The chart, from the World Bank's PPID, shows the evolution of public-private partnerships in infrastructure, aggregating projects across 139 low and middle-income countries. The blue series shows the total value of projects in US dollars (scale in the left vertical axis), while the orange series shows the total number of projects (scale in the right vertical axis).

As we can see, the last two decades have seen a marked increase in public-private partnerships in low and middle-income countries. In the World Bank's PPID Visualization Dashboard , you can explore the data in more detail. The estimates by sectors and world regions suggest that electricity and roads, specifically in South Asia and Latin America, have been the key drivers of these aggregate trends.

What is linked with government spending?

Government spending correlates with national income.

We have already pointed out that government expenditure as a share of national income is higher in richer countries. The visualization provides further evidence of the extent of this correlation.

The vertical axis measures GDP per capita (after accounting for differences in purchasing power across countries), while the horizontal axis measures government spending as a share of GDP. The vertical axis is expressed by default in a logarithmic scale, so that the correlation is easier to appreciate – you can change to a linear scale by clicking on ‘Settings.’

We can see that there is a strong positive correlation: high-income countries tend to have larger government expenditures as a share of their GDP. And this is also true within world regions (represented here with different colors).

This correlation reflects the fact that high-income countries tend to have more capacity to extract revenues, which in turn is due to their capacity to implement efficient tax collection systems. In our topic page on Taxation, we discuss the drivers of tax revenues in detail.

Government spending is an important instrument for reducing inequality

The visualization shows the reduction of inequality that different OECD countries achieve through taxes and transfers.

The estimates correspond to the percentage point reduction in inequality, as measured by changes in the Gini coefficients of income, before and after taxes and transfers. Income 'before taxes' corresponds to what is usually known as market income (wages and salaries, self-employment income, capital and property income); while income after taxes and transfers corresponds to disposable income (market income, plus social security, cash transfers and private transfers, minus income taxes).

The data shows that across the 35 countries covered, taxes and transfers lower income inequality by around one-third on average. Yet cross-country differences are substantial.

Generally speaking, countries that achieve the largest redistribution through taxes and transfers tend to be those with the lowest after-tax inequality.

Interactive Charts on Government Spending

Mauro, P., Romeu, R., Binder, A., & Zaman, A. (2015). A modern history of fiscal prudence and profligacy. Journal of Monetary Economics, 76, 55-70.

Bastagli, F., Coady, D., & Gupta, S. (2012). Income inequality and fiscal policy (No. 12/08R). International Monetary Fund.

Cite this work

Our articles and data visualizations rely on work from many different people and organizations. When citing this topic page, please also cite the underlying data sources. This topic page can be cited as:

BibTeX citation

Reuse this work freely

All visualizations, data, and code produced by Our World in Data are completely open access under the Creative Commons BY license . You have the permission to use, distribute, and reproduce these in any medium, provided the source and authors are credited.

The data produced by third parties and made available by Our World in Data is subject to the license terms from the original third-party authors. We will always indicate the original source of the data in our documentation, so you should always check the license of any such third-party data before use and redistribution.

All of our charts can be embedded in any site.

Our World in Data is free and accessible for everyone.

Help us do this work by making a donation.

Quick Guide to Understanding the Federal Budget

You may use a budget to determine how much money you need to cover certain expenses such as rent, utilities and groceries, as well as planning for emergencies or investing for the future. Budgets provide a framework to promote your economic well-being.

The U.S. government budget serves the same purpose: the budgetary process of the United States determines how much money the government can spend and where to allocate resources. The federal budget drives fiscal policy and determines the size and scope of the federal government, which in turn helps shape the economy.

Due to its size and scope, the federal budgetary planning process is complex. It involves many people—from the White House, from Congress and from federal agencies, and ultimately taxpayers.

When the Federal Budgetary Process Starts

The federal government fiscal year begins Oct. 1. However, the process for finalizing the federal budget begins much earlier, typically a year prior.

The budgetary planning process begins in the fall when federal agencies submit their budget requests to the Office of Management and Budget. The OMB prepares and manages the budget on behalf of the president. The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 gave the president overall responsibility for budget planning by requiring him to submit an annual, comprehensive budget proposal to Congress; that act also expanded the president’s control over budgetary information by establishing the Bureau of the Budget (renamed the Office of Management and Budget in 1971).

By convention, the president each year submits a proposed budget to Congress by the first Monday in February, The president submits a budget to Congress by the first Monday in February every year. The budget contains estimates of federal government income and spending for the upcoming fiscal year and also recommends funding levels for the federal government. though in some cases the timing differs based upon circumstances. The proposed budget, which is not the final budget, is prioritized by the president’s revenue and spending focus areas.

Government Spending: Focus Areas

As outlined in a previous blog post, federal government spending is divided into three categories:

- Mandatory spending: Funds that pay for Social Security, Medicare, veterans’ benefits, and other categories of mandated spending. In other words, spending that has been designated by law.

- Discretionary spending: Funds that support national defense, health and safety, transportation, education, housing, and other social and environmental programs. Discretionary spending is allocated by Congress through appropriations to federal agencies.

- Interest on the public debt: Funds the government allocates to pay toward outstanding debt.

Resolutions, Appropriations and Authorization

Each April, the U.S. Congress prepares a budget resolution, or a framework, for setting spending limits. The House and Senate each hold hearings of their respective budget committees to hear requests from federal agencies, which outline why their particular programs require the funding. Each committee then submits budgetary resolutions for a vote. Once the resolutions are voted on, Congress begins the appropriations process.

An appropriation is a law that provides budget authority or approval to receive funds. Each year, Congress passes appropriation bills that are generated by 12 financial subcommittees and grouped by the type of program and agency.

Congress can enact supplemental appropriations at any time when there is an urgent funding need .

Once Congress passes all appropriation bills, the completed budget goes back to the president for authorization (formal signature). If Congress, or Congress and the president, cannot agree on the budget, Congress can pass an omnibus bill . An omnibus bill packages together certain budgetary measures for a limited time to ensure funding.

The Deficit and National Debt

The national debt is the amount of money the federal government has borrowed to cover outstanding balances, like the balance you may have on your credit card. If spending exceeds revenue in a given fiscal year, there’s a budget deficit . To make up the deficit, the federal government has to borrow money, which it does by selling marketable securities like Treasury bonds, bills, and Treasury inflation-protected securities.

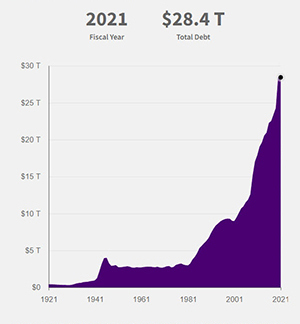

U.S. National Debt Has Grown over the Last 100 Years

SOURCE: Historical Debt Outstanding data set from Fiscal Data; Bureau of Labor Statistics.

NOTES: 2021 dollars. Updated Sept. 30, 2021.

The total national debt is an accumulation of this borrowing along with the interest owed to investors who have purchased the securities. If over time the federal government has deficits (spending greater than tax revenues), the national debt grows.

The national debt allows the government to continue to pay for critical programs and services, even if funds are not immediately available.

U.S. Debt Ceiling and Government Shutdowns

Debt Ceiling

The debt ceiling , or debt limit, is a restriction imposed by Congress on the amount of outstanding debt the federal government can hold. This is like the credit limit your bank can impose. The debt ceiling is the maximum amount that Treasury can borrow to pay “bills” that are due as well as pay for future investments and interest on previously borrowed money. Congress can raise the debt ceiling, but if it is reached without Congress taking action, the government must stop spending, thereby losing the ability to pay bills or fund government programs and services.

While the United States has reached the debt ceiling at times, it has never run out of resources or failed to meet its financial obligations.

Government Shutdowns

Unlike spending stopped by a debt ceiling, a government shutdown is caused by Congress, or Congress and the president, failing to reach an agreement on the budget. Until there is a compromise, federal agencies must discontinue all nonessential functions until funding legislation is passed. Essential services and mandatory spending initiatives are allowed to continue. The overall health of the economy can be a factor in the budgetary process. In economic downturns, a reduction of federal revenue leading to reduced federal spending is expected. This expectation leads to an increased likelihood of debt ceiling overages and government shutdowns in the future.

Your Complete Guide to Government Financial Data

The national debt explainer is the first of four U.S. government financial concepts from “Your Guide to America’s Finances,” also known as America’s Finance Guide, which will have additional explainers to be released in the coming months. The national debt explainer provides an overview of the national debt, a look at funding programs and services, debt trends over time, how the debt is broken down, and more. The information can be found on FiscalData.Treasury.gov .

Fiscal Data is a website from the U.S. Department of the Treasury and Bureau of the Fiscal Service bringing together important data sets related to federal finance. It’s one modern site, designed with you in mind. Explore data sets on topics such as debt, deficit, revenue and spending, including the Monthly Treasury Statement and the Monthly Statement of the Public Debt . Each data set is available in fully machine-readable files, with easily accessible APIs, and comprehensive metadata.

- The Budget and Accounting Act of 1921 gave the president overall responsibility for budget planning by requiring him to submit an annual, comprehensive budget proposal to Congress; that act also expanded the president’s control over budgetary information by establishing the Bureau of the Budget (renamed the Office of Management and Budget in 1971).

- The president submits a budget to Congress by the first Monday in February every year. The budget contains estimates of federal government income and spending for the upcoming fiscal year and also recommends funding levels for the federal government.

Crystal Flynn is a senior content strategist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.

Related Topics

This blog explains everyday economics, consumer topics and the Fed. It also spotlights the people and programs that make the St. Louis Fed central to America’s economy. Views expressed are not necessarily those of the St. Louis Fed or Federal Reserve System.

Media questions

All other blog-related questions

Page One Economics ®

Making sense of the national debt.

"Blessed are the young for they shall inherit the national debt."

—Herbert Hoover

We live in a world of scarcity —which means that our wants exceed the resources required to fulfill them. For many of us, a household budget constrains how many goods and services we can buy. But, what if we want to consume more goods and services than our budget allows? We can borrow against future income to fulfill our wants now. 1 This type of spending—when your spending exceeds your income—is called deficit spending. The downside of borrowing money, of course, is that you must repay it with interest, so you will have less money to buy goods and services in the future.

2018 U.S. Federal Deficit

In 2018 the federal deficit was $779 billion, which means that the U.S. federal government spent $779 billion more than it collected.

SOURCE: https://datalab.usaspending.gov/americas-finance-guide/ . Data are provided by the U.S. Department of the Treasury and refer to fiscal year 2018.

Governments face the same dilemma. They too can run a deficit, or borrow against future income, to fulfill more of their citizens' wants now (Figure 1). For a variety of reasons, governments may borrow rather than fund spending with current taxes. Deficit spending can be used to invest in infrastructure, education, research and development, and other programs intended to boost future productivity. Because this type of investment can increase productive capacity , it can also increase national income over time. And deficit spending can be used to create demand for goods and services during recessions.

For the U.S. government, deficit spending has become the norm. In the past 90 years, it has run 76 annual deficits and only 14 annual surpluses. In the past 50 years, it has run only 4 annual surpluses. 2 The accumulation of past deficits and surpluses is the current national debt : Deficits add to the debt, while surpluses subtract from the debt. At the end of the first quarter of 2019, the total national debt, also called total U.S. federal public debt, was $22 trillion and growing. This circumstance raises important questions: How much debt can an economy sustain? What are the long-term risks of high debt levels?

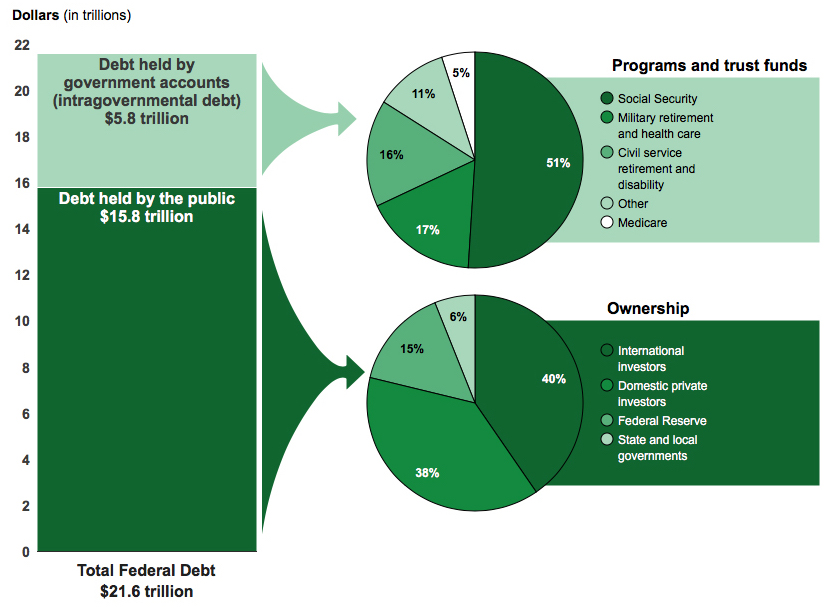

Who "Owns" the National Debt?

While individuals borrow money from financial institutions, the U.S. federal government borrows by selling U.S. Treasury securities (bills, notes, and bonds) to "the public." For example, when investors purchase newly issued U.S. Treasury securities, they are lending their money to the U.S. government. The purchaser may receive periodic payments and/or a final payment, known as the "face value," at the end of the term. You or someone close to you likely holds U.S. Treasury securities either directly in an investment portfolio or indirectly through a mutual fund or pension account. As such, you, or they, own U.S. government debt. But, as a taxpayer, you are also beholden to pay part of that debt. A majority of the national debt is held by "the public," which includes individuals, corporations, state or local governments, Federal Reserve Banks, and foreign governments. 3 In other words, debt held by the public includes U.S. government debt held by any entity except the U.S. federal government itself (Figure 2). The largest public holders of U.S. government debt are international investors (40 percent), domestic private investors (38 percent), Federal Reserve Banks (15 percent), and state and local governments (6 percent). 4

Fiscal Year 2018 Debt Held by the Public and Intragovernmental Debt

SOURCE: https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt , accessed September 5, 2019.

In addition to owing money to "the public," the U.S. government also owes money to departments within the U.S. government. For example, the Social Security system has run surpluses for many years (the amount collected through the Social Security tax was greater than the benefits paid out) and placed the money in a trust fund. 5 These surpluses were used to purchase U.S. Treasury securities. Forecasts suggest that as the population ages and demographics change, the amount paid in Social Security benefits will exceed the revenues collected through the Social Security tax and the money saved in the trust fund will be needed to fill the gap. In short, some of the $22 trillion in total debt is intragovernmental holdings—money the government owes itself. Of the total national debt, $5.8 trillion is intragovernmental holdings and the remaining $16.2 trillion is debt held by the public. 6 Because debt held by the public represents debt payments external to the government, many economists feel it is a better measure of the debt burden.

Household and Government Financing Over the Life Cycle

The life cycle theory of consumption and saving holds that households seek to smooth their consumption of goods and services over the life cycle by borrowing early in life (for college or to buy a home), then saving and paying down debt during their working careers, and finally living on their savings during retirement. Financial advisors often suggest that people try to be debt free before they retire. As such, people are often motivated in their prime working years to pay down their debts and then pay them off entirely before they quit working. Given this mindset, people often assume that government debt must be paid in full at some point. But there are important differences between government debt and household debt.

While people tend to prefer to pay off their debts before they retire (and stop earning income) or die, governments endure indefinitely. In general, governments expect that their economies will continue to grow and that they will continue to collect tax revenue. If governments need to refinance past debts or cover new deficits, they can simply borrow. In effect, governments never need to pay off their debts entirely because the governments will exist indefinitely.

However, this does not mean that debt is without cost. It is important to understand that debt has an opportuni ty cost . For the 2018 fiscal year, interest payments on the U.S. national debt were $523 billion. 7 This money could have financed other projects if the debt did not exist. And, of course, that $523 billion was simply the interest on the existing debt and did not pay down that debt.

How Much Debt Is Too Much Debt?

Although governments may endure indefinitely, that does not mean they can accumulate unlimited debt. Governments must have the necessary income to finance their debt. Economists use gross domestic product (GDP), the total market value, expressed in dollars, of all final goods and services produced in an economy in a given year, as a measure of national income. Because GDP indicates national income, it also indicates the potential income that can be taxed, and taxes are a primary source of government revenues. In this way, a nation's GDP determines how much debt can be supported, which is similar to how a person's income determines how much debt that person can reasonably take on. Just as individuals can sustain higher debt as their incomes increase, economies can sustain higher debt when the economy grows over time. However, if debt grows at a faster rate than income, eventually the debt might become unsustainable. Economists use the debt-to GDP ratio to measure how sustainable the debt is (Figure 3). Some economists, referred to as "owls," suggest that people's worries about U.S. government debt are overblown (see the boxed insert, "Deficit Hawks, Doves, and…Owls?").

Federal Debt Held by the Public as Percent of Gross Domestic Product

Federal debt held by the public has grown faster than GDP, lead ing to a rising debt-to-GDP ratio.

NOTE: Gray bars indicate recessions as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

SOURCE: U.S. Office of Management and Budget. FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=lKfK, accessed September 5, 2019.

The Government Accountability Office (GAO) suggests that the U.S government debt is currently on an unsustainable path: The federal debt is projected to grow at a faster rate than GDP for the foreseeable future. A significant portion of the growth in projected debt is to fund social programs such as Medicare and Social Security. Using debt held by the public (instead of total public debt), the debt-to-GDP ratio averaged 46 percent from 1946 to 2018 but reached 77 percent by the end of 2018 (see Figure 3). It is projected to exceed 100 percent within 20 years. 8

Credit risk is the risk to the lender that the borrower will not repay the loan. It is one component of the interest rate that borrowers pay. Like for all loans, interest rates on Treasury securities reflect risk of default . The higher the risk of default, the higher the interest rate investors will expect: A country perceived as a higher credit risk must pay bond holders higher interest rates than a country perceived as a lower credit risk, all else equal. Thus, when bond yields spike, it might reflect rising risk.

Economist Herb Stein once said, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop." In other words, trends that are unsustainable will not continue because the economy will adjust, sometimes in abrupt and jarring ways. While governments never have to entirely pay off debt, there are debt levels that investors might perceive as unsustainable. A solution some countries with high levels of unsustainable debt have tried is printing money. In this scenario, the government borrows money by issuing bonds and then orders the central bank to buy those bonds by creating (printing) money. History has taught us, however, that this type of policy leads to extremely high rates of inflation ( hyperinflation ) and often ends in economic ruin. Some of the better-known examples of such polices are Germany in 1921-23, Zimbabwe in 2007-09, and Venezuela currently. An important protection against this type of policy is to create an independent central bank that is insulated from the political process and has clear objectives (such as a specific target for the inflation rate) so that it can make policy decisions to sustain economic health over the long run rather than respond to political pressures. 9

Conclusion

The national debt is high by historical standards—and rising. People often assume that governments must pay off their debts in the same way that individuals do. However, there are important differences: Governments (and their economies) do not retire, and governments do not die (or don't intend to). As long as their debt payments remain sustainable, governments can finance their debt indefinitely. And if a government prints money to solve its debt problem, history warns that hyperinflation and financial ruin will likely result. While debt in itself is not a bad thing, it can become dangerous if it becomes unsustainable.

1 Households could alternately spend out of past savings.

2 U.S. Office of Management and Budget, "Federal Surplus or Deficit." FRED®, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=otZF , accessed September 5, 2019.

3 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Frequently Asked Questions about the Public Debt." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/resources/faq/faq_publicdebt.htm#DebtOwner , accessed September 5, 2019.

4 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future: Federal Debt." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=federal_debt , accessed September 5, 2019.

5 Social Security Administration. "Trust Fund Data." https://www.ssa.gov/oact/STATS/table4a3.html , accessed September 5, 2019.

6 U.S. Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Federal Debt Held by the Public." FRED ® , Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?g=mAfK , accessed September 5, 2019.

7 U.S Department of the Treasury, Bureau of the Fiscal Service. "Interest Expense on the Debt Outstanding." https://www.treasurydirect.gov/govt/reports/ir/ir_expense.htm , accessed September 5, 2019.

8 U.S. Government Accountability Office. "America's Fiscal Future." https://www.gao.gov/americas_fiscal_future?t=fiscal_forecast#projecting_the_future , accessed September 5, 2019.

9 Waller, Christopher. "Independence + Accountability: Why the Fed Is a Well-Designed Central Bank." Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review , September/October 2011, 93 (5), pp. 293-301; https://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/11/09/293-302Waller.pdf .

© 2019, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. The views expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis or the Federal Reserve System.

Default: The failure to promptly pay interest or principal when due.

Fiat money: A substance or device used as money, having no intrinsic value (no value of its own), or representational value (not representing anything of value, such as gold).

Hyperinflation: A very rapid rise in the overall price level; an extremely high rate of inflation.

Inflation: A general, sustained upward movement of prices for goods and services in an economy.

National debt: The accumulation of budget deficits. Also known as government debt.

Opportunity cost: The value of the next-best alternative when a decision is made; it's what is given up.

Productive capacity: The maximum output an economy can produce with the current level of available resources.

Scarcity: The condition that exists because there are not enough resources to produce everyone's wants.

U.S. Treasury securities: Bonds, notes, bills, and other debt instruments sold by the U.S. government to finance its expenditures.

Cite this article

Subscribe to Our Newsletter

Stay current with brief essays, scholarly articles, data news, and other information about the economy from the Research Division of the St. Louis Fed.

SUBSCRIBE TO THE RESEARCH DIVISION NEWSLETTER

Research division.

- Legal and Privacy

One Federal Reserve Bank Plaza St. Louis, MO 63102

Information for Visitors

30.1 Government Spending

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify U.S. budget deficit and surplus trends over the past five decades

- Explain the differences between the U.S. federal budget, and state and local budgets

Government spending covers a range of services that the federal, state, and local governments provide. When the federal government spends more money than it receives in taxes in a given year, it runs a budget deficit . Conversely, when the government receives more money in taxes than it spends in a year, it runs a budget surplus . If government spending and taxes are equal, it has a balanced budget . For example, in 2009, the U.S. government experienced its largest budget deficit ever, as the federal government spent $1.4 trillion more than it collected in taxes. This deficit was about 10% of the size of the U.S. GDP in 2009, making it by far the largest budget deficit relative to GDP since the mammoth borrowing the government used to finance World War II.

This section presents an overview of government spending in the United States.

Total U.S. Government Spending

Federal spending in nominal dollars (that is, dollars not adjusted for inflation) has grown by a multiple of more than 38 over the last four decades, from $93.4 billion in 1960 to $3.9 trillion in 2014. Comparing spending over time in nominal dollars is misleading because it does not take into account inflation or growth in population and the real economy. A more useful method of comparison is to examine government spending as a percent of GDP over time.

The top line in Figure 30.2 shows the federal spending level since 1960, expressed as a share of GDP. Despite a widespread sense among many Americans that the federal government has been growing steadily larger, the graph shows that federal spending has hovered in a range from 18% to 22% of GDP most of the time since 1960. The other lines in Figure 30.2 show the major federal spending categories: national defense, Social Security, health programs, and interest payments. From the graph, we see that national defense spending as a share of GDP has generally declined since the 1960s, although there were some upward bumps in the 1980s buildup under President Ronald Reagan and in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. In contrast, Social Security and healthcare have grown steadily as a percent of GDP. Healthcare expenditures include both payments for senior citizens (Medicare), and payments for low-income Americans (Medicaid). State governments also partially fund Medicaid. Interest payments are the final main category of government spending in Figure 30.2.

Each year, the government borrows funds from U.S. citizens and foreigners to cover its budget deficits. It does this by selling securities (Treasury bonds, notes, and bills)—in essence borrowing from the public and promising to repay with interest in the future. From 1961 to 1997, the U.S. government has run budget deficits, and thus borrowed funds, in almost every year. It had budget surpluses from 1998 to 2001, and then returned to deficits.

The interest payments on past federal government borrowing were typically 1–2% of GDP in the 1960s and 1970s but then climbed above 3% of GDP in the 1980s and stayed there until the late 1990s. The government was able to repay some of its past borrowing by running surpluses from 1998 to 2001 and, with help from low interest rates, the interest payments on past federal government borrowing had fallen back to 1.4% of GDP by 2012.

We investigate the government borrowing and debt patterns in more detail later in this chapter, but first we need to clarify the difference between the deficit and the debt. The deficit is not the debt . The difference between the deficit and the debt lies in the time frame. The government deficit (or surplus) refers to what happens with the federal government budget each year. The government debt is accumulated over time. It is the sum of all past deficits and surpluses. If you borrow $10,000 per year for each of the four years of college, you might say that your annual deficit was $10,000, but your accumulated debt over the four years is $40,000.

These four categories—national defense, Social Security, healthcare, and interest payments—account for roughly 73% of all federal spending, as Figure 30.3 shows. The remaining 27% wedge of the pie chart covers all other categories of federal government spending: international affairs; science and technology; natural resources and the environment; transportation; housing; education; income support for the poor; community and regional development; law enforcement and the judicial system; and the administrative costs of running the government.

State and Local Government Spending

Although federal government spending often gets most of the media attention, state and local government spending is also substantial—at about $3.1 trillion in 2014. Figure 30.4 shows that state and local government spending has increased during the last four decades from around 8% to around 14% today. The single biggest item is education, which accounts for about one-third of the total. The rest covers programs like highways, libraries, hospitals and healthcare, parks, and police and fire protection. Unlike the federal government, all states (except Vermont) have balanced budget laws, which means any gaps between revenues and spending must be closed by higher taxes, lower spending, drawing down their previous savings, or some combination of all of these.

U.S. presidential candidates often run for office pledging to improve the public schools or to get tough on crime. However, in the U.S. government system, these tasks are primarily state and local government responsibilities. In fiscal year 2014 state and local governments spent about $840 billion per year on education (including K–12 and college and university education), compared to only $100 billion by the federal government, according to usgovernmentspending.com. In other words, about 90 cents of every dollar spent on education happens at the state and local level. A politician who really wants hands-on responsibility for reforming education or reducing crime might do better to run for mayor of a large city or for state governor rather than for president of the United States.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 2e

- Publication date: Oct 11, 2017

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-2e/pages/30-1-government-spending

© Jun 15, 2022 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Impact of Increasing Government Spending

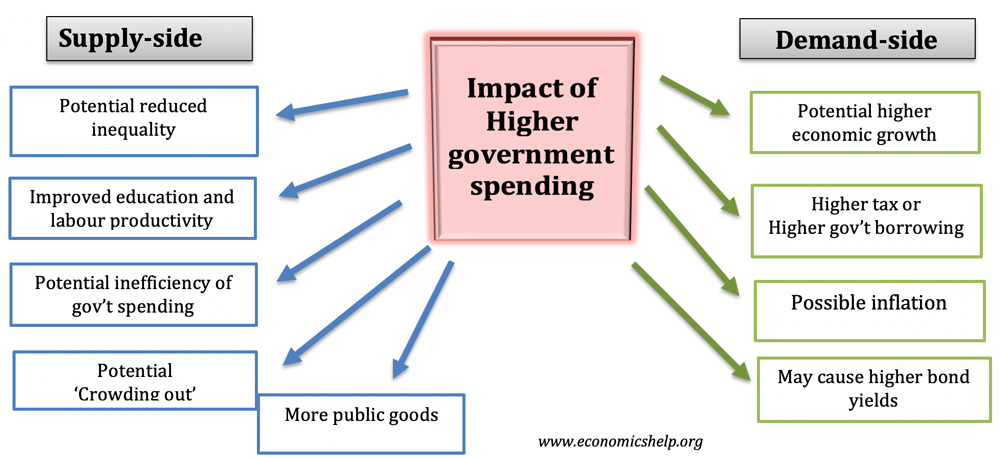

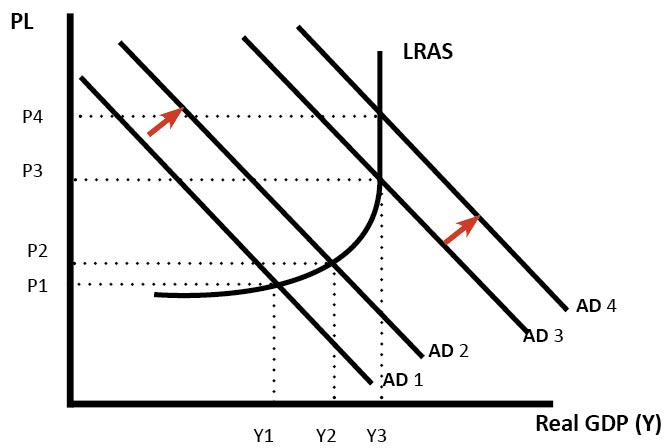

Increased government spending is likely to cause a rise in aggregate demand (AD). This can lead to higher growth in the short-term. It can also potentially lead to inflation.

Higher government spending will also have an impact on the supply-side of the economy – depending on which area of government spending is increased. If spending is focused on improving infrastructure, this could lead to increased productivity and a growth in the long-run aggregate supply. If spending is focused on welfare benefits or pensions, it may reduce inequality, but it could crowd out more productive private sector investment.

Different targets of government spending

- There is a potential higher welfare benefit could reduce incentives to work, but on the other hand, welfare benefits can also help the labour market to function more efficiently.

- Pension spending – An ageing population, requires higher government spending, – pensions and health care spending. But pension spending has no impact on boosting productivity

- Education and training – If successfully targetted on improving skills and education, government spending can increase labour productivity and enable higher long-term economic growth.

- Infrastructure investment – Higher spending on roads and railways can help remove supply bottlenecks and enable greater efficiency. This can also boost long-term economic growth.

- Higher debt interest payments – If the government has higher debt and higher bond yields, then it can cause increased costs of borrowing. This spending will go to investors and have no benefit for the economy.

Evaluation of higher government spending

How is spending financed? It depends on how government spending is financed. If government spending is financed by higher taxes, then tax rises may counter-balance the higher spending, and there will be no increase in aggregate demand (AD).

Crowding out . If the economy is close to full capacity, higher government spending can lead to crowding out . This is when the government spends more, but it has the effect of reducing private sector spending. For example, if the government borrow from the private sector, the private sector has lower savings for private investment.

Inefficiency of gov’t spending . Some free-market economists argue gov’t spending has a significant potential to be more inefficient than the private sector spending. In the government sector, there may be poor information and lack of incentives, which leads to misallocation of resources. Therefore, bigger gov’t sector could lead to less efficient economy as gov’t spending takes place of private-sector spending.

Depends on the state of the economy . The impact of government spending also depends on the state of the economy. If the economy is close to full capacity, then higher government spending may cause inflationary pressures and little increase in real GDP. If the economy is in recession, and the government borrows from the private sector, it can act as an expansionary fiscal policy to boost economic growth

UK government spending

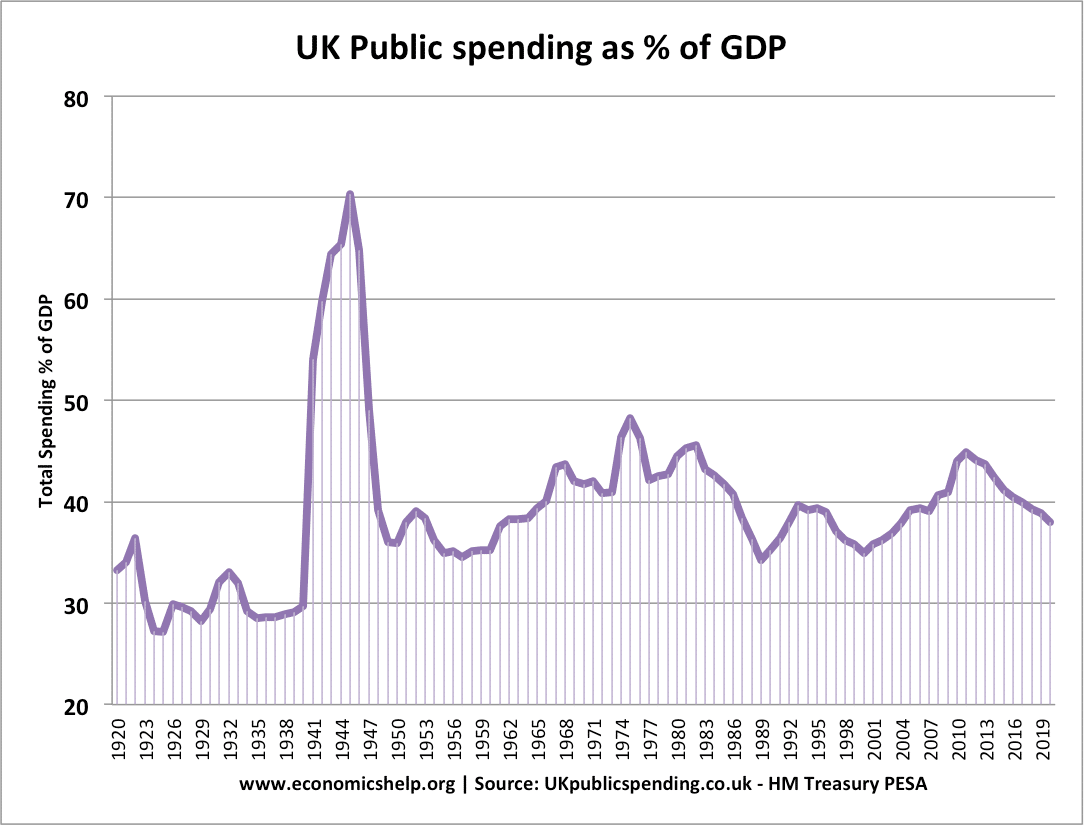

The biggest increase in government spending as % of GDP occurred during the two World Wars. In the post-war period, government spending as % of GDP was higher due to the creation of welfare state – NHS, welfare benefits and spending on council housing.

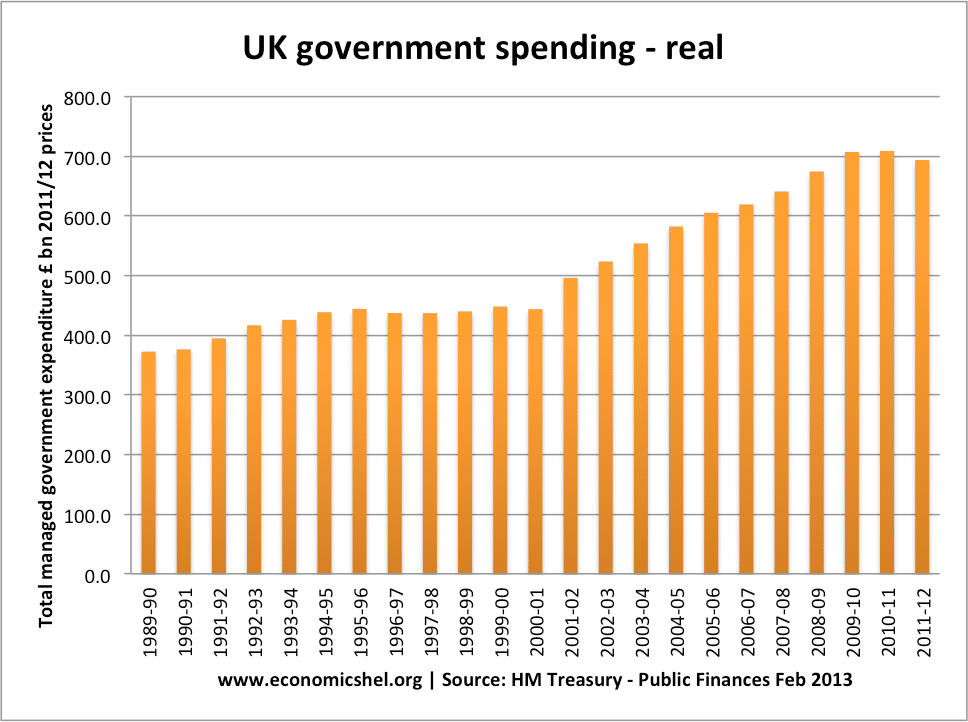

Real Government spending – spending adjusted for inflation.

Readers Question: Why will real GDP tend to rise when government spending and taxes rise by the same amount?

This is a controversial assertion in economics. Certainly many wouldn’t agree.

It is more likely that the rise in taxes will negate the impact of rising government spending. This would leave Aggregate Demand (AD) unchanged.

However, it is possible increased spending and tax rises could lead to an increase in GDP.

In a recession, consumers may reduce spending leading to an increase in private sector saving. Therefore a rise in taxes may not reduce spending as much as usual.

The increased government spending may create a multiplier effect. If government spending causes the unemployed to gain jobs, then they will have more income to spend leading to a further increase in aggregate demand. (e.g. construction workers employed by government increase spending in pubs and transport, causing other sectors of the economy to benefit from the government spending). In these situations of spare capacity in the economy, government spending may cause a bigger final increase in GDP than the initial injection.

However, if the economy was at full capacity, the increased government spending would tend to crowd out the private sector leading to no net increase in AD from switching from private sector spending to government sector spending.

Some economists would argue increasing government spending through higher taxes would lead to a more inefficient allocation of resources as governments tend to be less effective in spending money.

Another consideration is that an economy may grow at 2.5% a year. If there is higher government spending, this growth rate continues. But, the growth is not due to the rising government spending. The government spending just fails to change the growth rate.

- Cutting government spending

- What does the government spend its money on?

- Expansionary fiscal policy

9 thoughts on “Impact of Increasing Government Spending”

helpful article ,thank you

It Is The Best Explanation

Well received

Hi, Thank you for your explicit article

Joe Chukwunyere

But how increases interest rate gov spending increases money supply interest rate down and how invest ment is not coming and twin deficit

This has been of huge help to my research.

its a good well-explained article. but i would rather recommend to evaluate the impacts of increases government spending on each of the macro-economic aims of the economy, both positive and negative.

The research helped a lot..Thank you

How does the SSA GPO on survivor’s help some states equalize the states spending?

Comments are closed.

Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations

This essay is about deficit spending, explaining how it occurs when a government’s expenditures exceed its revenues, leading to a budget deficit financed by borrowing. It discusses the Keynesian economic rationale for deficit spending, particularly during recessions, to stimulate economic growth by creating jobs and boosting consumer confidence. The essay also addresses criticisms and risks, such as the accumulation of public debt, increased borrowing costs, and potential inflation. It highlights the importance of balancing economic stimulation with fiscal responsibility and examines how the impact of deficit spending varies between developing and developed countries. The essay concludes that while deficit spending can be beneficial, it requires careful management to ensure long-term fiscal sustainability.

How it works

The concept of deficit spending, frequently deliberated in fiscal policy discourse, delineates a scenario wherein a government’s disbursements surpass its earnings, culminating in a fiscal shortfall. This disparity is customarily assuaged through financial borrowing, entailing avenues such as the issuance of sovereign bonds or securing loans from international entities. Despite harboring apprehensions, deficit spending emerges as a conventional instrument wielded by governmental bodies to invigorate economic expansion, particularly amidst periods of recession or economic contraction.

The theoretical underpinnings of deficit spending trace back to Keynesian economics, postulating that during epochs of economic tumult marked by soaring joblessness or subdued consumer demand, state intervention via augmented spending can catalyze economic resurgence.

Through investments in infrastructural ventures, social welfare endeavors, and miscellaneous public amenities, governments can foster job creation, elevate consumer confidence, and catalyze overall economic dynamism. This escalated expenditure can engender a multiplier effect, wherein the initial disbursement begets supplementary economic dividends as capital permeates through the economic milieu.

Nevertheless, deficit spending does not evade critique or hazards. A primary apprehension revolves around the accretion of public indebtedness. As governmental bodies resort to heightened borrowing to underwrite their fiscal shortfalls, they ultimately confront the obligation to retire these debts along with accrued interest, a burden that could substantially encumber forthcoming fiscal frameworks. Escalating debt levels can precipitate augmented borrowing costs, as creditors may stipulate elevated interest rates to offset perceived risks. Moreover, excessive indebtedness can encroach upon private investment, as governmental borrowing could precipitate overall interest rate hikes, rendering capital acquisition more onerous for commercial entities and individuals.

A corollary concern associated with deficit spending is the specter of inflation. When governmental outlays surge without commensurate revenue augmentation, this can precipitate an uptick in the aggregate money supply. Should this inflation outstrip the concomitant expansion in goods and services, it may engender heightened price levels and diminished consumer purchasing clout. Inflation has the potential to erode the value of savings and fixed incomes, disproportionately impacting individuals with lower earnings and potentially fomenting social and economic disarray.

Notwithstanding these misgivings, myriad economists contend that deficit spending harbors the potential for utility when judiciously applied. During the crucible of the 2008 global financial meltdown, several nations undertook expansive deficit spending initiatives to ameliorate economic vicissitudes. These endeavors were attributed with forestalling deeper recessionary crevasses and expediting convalescence. Analogously, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, governmental entities worldwide embarked upon unparalleled deficit spending endeavors to buttress commercial enterprises, individuals, and healthcare infrastructures.

The efficacy of deficit spending hinges upon sundry variables, including extant public indebtedness levels, the overall economic robustness, and the precise policy formulations. It is incumbent upon governments to strike a equipoise between invigorating the economy and upholding fiscal prudence. This frequently necessitates the deployment of targeted and ephemeral deficit spending, undergirded by a cogent blueprint for reverting to fiscal equilibrium upon the amelioration of economic circumstances.

Moreover, the repercussions of deficit spending are contingent upon context. In less developed nations, where access to capital markets may be circumscribed and borrowing costs exorbitant, executing deficit spending initiatives sans imperiling fiscal stability may prove more arduous. Such nations may necessitate succor from international entities like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank to adroitly navigate their fiscal shortfalls.

In contradistinction, developed nations boasting robust credit standings and mature financial markets may enjoy greater latitude in engaging in deficit spending sans immediate adverse repercussions. Nevertheless, even within these precincts, vigilant oversight of debt levels and ensurance of sustainable borrowing practices over the longue durée remain imperative.

In summation, deficit spending embodies a nuanced and multifaceted instrument of fiscal policy, replete with both potential dividends and pitfalls. When wielded sagaciously, it can invigorate economic expansion and mitigate the impacts of economic downturns. Nonetheless, prudent stewardship is imperative to avert the perils of burgeoning indebtedness and inflation. By cognizantly apprehending the dynamics of deficit spending, policymakers can make informed decisions that reconcile transient economic exigencies with enduring fiscal robustness.

Cite this page

Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations. (2024, Jun 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/

"Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations." PapersOwl.com , 1 Jun 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/ [Accessed: 1 Jun. 2024]

"Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations." PapersOwl.com, Jun 01, 2024. Accessed June 1, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/

"Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations," PapersOwl.com , 01-Jun-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/. [Accessed: 1-Jun-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Deficit Spending: Economic Implications and Practical Considerations . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/deficit-spending-economic-implications-and-practical-considerations/ [Accessed: 1-Jun-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

How much has the U.S. government spent this year?

The U.S. government has spent $ NaN million in fiscal year to ensure the well-being of the people of the United States.

Fiscal year-to-date (since October ) total updated monthly using the Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS) dataset.

Compared to the federal spending of $ 0 million for the same period last year ( Oct -1 - Invalid Date null ) our federal spending has by $ 0 million .

Key Takeaways

The federal government spends money on a variety of goods, programs, and services to support the American public and pay interest incurred from borrowing. In fiscal year (FY) 0, the government spent $, which was than it collected (revenue), resulting in a .

The U.S. Constitution gives Congress the ability to create a federal budget – in other words, to determine how much money the government can spend over the course of the upcoming fiscal year. Congress’s budget is then approved by the President. Every year, Congress decides the amount and the type of discretionary spending, as well as provides resources for mandatory spending.

Money for federal spending primarily comes from government tax collection and borrowing. In FY 0 government spending equated to roughly $0 out of every $10 of the goods produced and services provided in the United States.

Federal Spending Overview

The federal government spends money on a variety of goods, programs, and services that support the economy and people of the United States. The federal government also spends money on the interest it has incurred on outstanding federal debt . Consequently, as the debt grows, the spending on interest expense also generally grows.

If the government spends more than it collects in revenue , then there is a budget deficit. If the government spends less than it collects in revenue, there is a budget surplus. In fiscal year (FY) , the government spent $ , which was than it collected (revenue), resulting in a . Visit the national deficit explainer to see how the deficit and revenue compare to federal spending.

Federal government spending pays for everything from Social Security and Medicare to military equipment, highway maintenance, building construction, research, and education. This spending can be broken down into two primary categories: mandatory and discretionary. These purchases can also be classified by object class and budget functions .

Throughout this page, we use outlays to represent spending. This is money that has actually been paid out and not just promised to be paid. When issuing a contract or grant, the U.S. government enters a binding agreement called an obligation. This means the government promises to spend the money, either immediately or in the future. As an example, an obligation occurs when a federal agency signs a contract, awards a grant, purchases a service, or takes other actions that require it to make a payment. Obligations do not always result in payments being made, which is why we show actual outlays that reflect actual spending occurring.

To see details on federal obligations, including a breakdown by budget function and object class, visit USAspending.gov .

The U.S. Treasury uses the terms “government spending,” “federal spending,” “national spending,” and “federal government spending” interchangeably to describe spending by the federal government.

According to the Constitution’s Preamble, the purpose of the federal government is “…to establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity.” These goals are achieved through government spending.

Spending Categories

The federal budget is divided into approximately 20 categories, known as budget functions. These categories organize federal spending into topics based on their purpose (e.g., National Defense, Transportation, and Health).

What does the government buy?

The government buys a variety of products and services used to serve the public - everything from military aircraft, construction and highway maintenance equipment, buildings, and livestock, to research, education, and training. The chart below shows the top 10 categories and agencies for federal spending in FY .

Visit the Monthly Treasury Statement (MTS) dataset to explore and download this data.

For more details on U.S. government spending by category and agency, visit USAspending.gov’s Spending Explorer and Agency Profile pages.

The Difference Between Mandatory, Discretionary, and Supplemental Spending

Who controls federal government spending.

Government spending is broken down into two primary categories: mandatory and discretionary. Mandatory spending represents nearly two-thirds of annual federal spending. This type of spending does not require an annual vote by Congress. The second major category is discretionary spending. The difference between mandatory and discretionary spending relates to whether spending is dictated by prior law or voted on in the annual appropriations process. Another type of appropriation spending is called supplemental appropriations , in which spending laws are passed to address needs that have arisen after the fiscal year has begun.

Mandatory Spending

Mandatory spending, also known as direct spending, is mandated by existing laws. This type of spending includes funding for entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security and other payments to people, businesses, and state and local governments. For example, the Social Security Act requires the government to provide payments to beneficiaries based on the amount of money they’ve earned and other factors. Last amended in 2019, the Social Security Act will determine the level of federal spending into the future until it is amended again. Due to authorization laws, the funding for these programs must be allocated for spending each year, hence the term mandatory.

Discretionary Spending

Discretionary spending is money formally approved by Congress and the President during the appropriations process each year. Generally, Congress allocates over half of the discretionary budget towards national defense and the rest to fund the administration of other agencies and programs. These programs range from transportation, education, housing, and social service programs, as well as science and environmental organizations.

Supplemental Spending