Why climate change is still the greatest threat to human health

Polluted air and steadily rising temperatures are linked to health effects ranging from increased heart attacks and strokes to the spread of infectious diseases and psychological trauma.

People around the world are witnessing firsthand how climate change can wreak havoc on the planet. Steadily rising average temperatures fuel increasingly intense wildfires, hurricanes, and other disasters that are now impossible to ignore. And while the world has been plunged into a deadly pandemic, scientists are sounding the alarm once more that climate change is still the greatest threat to human health in recorded history .

As recently as August—when wildfires raged in the United States, Europe, and Siberia—World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a statement that “the risks posed by climate change could dwarf those of any single disease.”

On September 5, more than 200 medical journals released an unprecedented joint editorial that urged world leaders to act. “The science is unequivocal,” they write. “A global increase of 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average and the continued loss of biodiversity risk catastrophic harm to health that will be impossible to reverse.”

Despite the acute dangers posed by COVID-19, the authors of the joint op-ed write that world governments “cannot wait for the pandemic to pass to rapidly reduce emissions.” Instead, they argue, everyone must treat climate change with the same urgency as they have COVID-19.

Here’s a look at the ways that climate change can affect your health—including some less obvious but still insidious effects—and why scientists say it’s not too late to avert catastrophe.

Air pollution

Climate change is caused by an increase of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases in Earth’s atmosphere, mostly from fossil fuel emissions. But burning fossil fuels can also have direct consequences for human health. That’s because the polluted air contains small particles that can induce stroke and heart attacks by penetrating the lungs and heart and even traveling into the bloodstream. Those particles might harm the organs directly or provoke an inflammatory response from the immune system as it tries to fight them off. Estimates suggest that air pollution causes anywhere between 3.6 million and nine million premature deaths a year.

“The numbers do vary,” says Andy Haines , professor of environmental change and public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and author of the recently published book Planetary Health . “But they all agree that it’s a big public health burden.”

People over the age of 65 are most susceptible to the harmful effects of air pollution, but many others are at risk too, says Kari Nadeau , director of the Sean N. Parker Center for Allergy and Asthma Research at Stanford University. People who smoke or vape are at increased risk, as are children with asthma.

Air pollution also has consequences for those with allergies. Carbon dioxide increases the acidity of the air, which then pulls more pollen out from plants. For some people, this might just mean that they face annoyingly long bouts of seasonal allergies. But for others, it could be life-threatening.

“For people who already have respiratory disease, boy is that a problem,” Nadeau says. When pollen gets into the respiratory pathway, the body creates mucus to get rid of it, which can then fill up and suffocate the lungs.

Even healthy people can have similar outcomes if pollen levels are especially intense. In 2016, in the Australian state of Victoria, a severe thunderstorm combined with high levels of pollen to induce what The Lancet has described as “the world’s largest and most catastrophic epidemic of thunderstorm asthma.” So many residents suffered asthma attacks that emergency rooms were overwhelmed—and at least 10 people died as a result.

Climate change is also causing wildfires to get worse, and wildfire smoke is especially toxic. As one recent study showed, fires can account for 25 percent of dangerous air pollution in the U.S. Nadeau explains that the smoke contains particles of everything that the fire has consumed along its path—from rubber tires to harmful chemicals. These particles are tiny and can penetrate even deeper into a person’s lungs and organs. ( Here’s how breathing wildfire smoke affects the body .)

Extreme heat

Heat waves are deadly, but researchers at first didn’t see direct links between climate change and the harmful impacts of heat waves and other extreme weather events. Haines says the evidence base has been growing. “We have now got a number of studies which has shown that we can with high confidence attribute health outcomes to climate change,” he says.

Most recently, Haines points to a study published earlier this year in Nature Climate Change that attributes more than a third of heat-related deaths to climate change. As National Geographic reported at the time , the study found that the human toll was even higher in some countries with less access to air conditioning or other factors that render people more vulnerable to heat. ( How climate change is making heat waves even deadlier .)

That’s because the human body was not designed to cope with temperatures above 98.6°F, Nadeau says. Heat can break down muscles. The body does have some ways to deal with the heat—such as sweating. “But when it’s hot outside all the time, you cannot cope with that, and your heart muscles and cells start to literally die and degrade,” she says.

If you’re exposed to extreme heat for too long and are unable to adequately release that heat, the stress can cause a cascade of problems throughout the body. The heart has to work harder to pump blood to the rest of the organs, while sweat leeches the body of necessary minerals such as sodium and potassium. The combination can result in heart attacks and strokes .

Dehydration from heat exposure can also cause serious damage to the kidneys, which rely on water to function properly. For people whose kidneys are already beginning to fail—particularly older adults—Nadeau says that extreme heat can be a death sentence. “This is happening more and more,” she says.

Studies have also drawn links between higher temperatures and preterm birth and other pregnancy complications. It’s unclear why, but Haines says that one hypothesis is that extreme heat reduces blood flow to the fetus.

Food insecurity

One of the less direct—but no less harmful—ways that climate change can affect health is by disrupting the world’s supply of food.

You May Also Like

This brain-eating amoeba is on the rise

2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

‘Corn sweat’—and other weird weather phenomena—explained

Climate change both reduces the amount of food that’s available and makes it less nutritious. According to an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report , crop yields have already begun to decline as a result of rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and extreme weather events. Meanwhile, studies have shown that increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere can leech plants of zinc, iron, and protein—nutrients that humans need to survive.

Malnutrition is linked to a variety of illnesses, including heart disease, cancer, and diabetes. It can also increase the risk of stunting, or impaired growth , in children, which can harm cognitive function.

Climate change also imperils what we eat from the sea. Rising ocean temperatures have led many fish species to migrate toward Earth’s poles in search of cooler waters. Haines says that the resulting decline of fish stocks in subtropic regions “has big implications for nutrition,” because many of those coastal communities depend on fish for a substantial amount of the protein in their diets.

This effect is likely to be particularly harmful for Indigenous communities, says Tiff-Annie Kenny, a professor in the faculty of medicine at Laval University in Quebec who studies climate change and food security in the Canadian Arctic. It’s much more difficult for these communities to find alternative sources of protein, she says, either because it’s not there or because it’s too expensive. “So what are people going to eat instead?” she asks.

Infectious diseases

As the planet gets hotter, the geographic region where ticks and mosquitoes like to live is getting wider. These animals are well-known vectors of diseases such as the Zika virus, dengue fever, and malaria. As they cross the tropics of Cancer and Capricorn, Nadeau says, mosquitoes and ticks bring more opportunities for these diseases to infect greater swaths of the world.

“It used to be that they stayed in those little sectors near the Equator, but now unfortunately because of the warming of northern Europe and Canada, you can find Zika in places you wouldn’t have expected,” Nadeau says.

In addition, climate conditions such as temperature and humidity can impact the life cycle of mosquitoes. Haines says there’s particularly good evidence showing that, in some regions, climate change has altered these conditions in ways that increase the risk of mosquitos transmitting dengue .

There are also several ways in which climate change is increasing the risk of diseases that can be transmitted through water, such as cholera, typhoid fever, and parasites. Sometimes that’s fairly direct, such as when people interact with dirty floodwaters. But Haines says that drought can have indirect impacts when people, say, can’t wash their hands or are forced to drink from dodgier sources of freshwater.

Mental health

A common result of any climate-linked disaster is the toll on mental health. The distress caused by drastic environmental change is so significant that it has been given its own name— solastalgia .

Nadeau says that the effects on mental health have been apparent in her studies of emergency room visits arising from wildfires in the western U.S. People lose their homes, their jobs, and sometimes their loved ones, and that takes an immediate toll. “What’s the fastest acute issue that develops? It’s psychological,” she says. Extreme weather events such as wildfires and hurricanes cause so much stress and anxiety that they can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder and even suicide in the long run.

Another common factor is that climate change causes disproportionate harm to the world’s most vulnerable people. On September 2, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released an analysis showing that racial and ethnic minority communities are particularly at risk . According to the report, if temperatures rise by 2°C (3.6°F), Black people are 40 percent more likely to live in areas with the highest projected increases in related deaths. Another 34 percent are more likely to live in areas with a rise in childhood asthma.

Further, the effects of climate change don’t occur in isolation. At any given time, a community might face air pollution, food insecurity, disease, and extreme heat all at once. Kenny says that’s particularly devastating in communities where the prevalence of food insecurity and poverty are already high. This situation hasn’t been adequately studied, she says, because “it’s difficult to capture these shocks that climate can bring.”

Why there’s reason for hope

In recent years, scientists and environmental activists have begun to push for more research into the myriad health effects of climate change. “One of the striking things is there’s been a real dearth of funding for climate change and health,” Haines says. “For that reason, some of the evidence we have is still fragmentary.”

Still, hope is not lost. In the Paris Agreement, countries around the world have pledged to limit global warming to below 2°C (3.6°F)—and preferably to 1.5°C (2.7°F)—by cutting their emissions. “When you reduce those emissions, you benefit health as well as the planet,” Haines says.

Meanwhile, scientists and environmental activists have put forward solutions that can help people adapt to the health effects of climate change. These include early heat warnings and dedicated cooling centers, more resilient supply chains, and freeing healthcare facilities from dependence on the electric grid.

Nadeau argues that the COVID-19 pandemic also presents an opportunity for world leaders to think bigger and more strategically. For example, the pandemic has laid bare problems with efficiency and equity that have many countries restructuring their healthcare facilities. In the process, she says, they can look for new ways to reduce waste and emissions, such as getting more hospitals using renewable energy.

“This is in our hands to do,” Nadeau says. “If we don’t do anything, that would be cataclysmic.”

Related Topics

- AIR POLLUTION

- WATER QUALITY

- NATURAL DISASTERS

- PUBLIC HEALTH

- CLIMATE CHANGE

What we're learning from lung cancer patients who never smoked

The U.S. plans to limit PFAS in drinking water. What does that really mean?

Extreme heat is the future. Here are 10 practical ways to manage it.

Here’s what extreme heat does to the body

Some antibiotics are no longer as effective. That's as concerning as it sounds.

- Environment

- Paid Content

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- Destination Guide

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- For authors

- Browse by collection

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 11, Issue 6

- Health effects of climate change: an overview of systematic reviews

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4548-2229 Rhea J Rocque 1 ,

- Caroline Beaudoin 2 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4716-6505 Ruth Ndjaboue 2 , 3 ,

- Laura Cameron 1 ,

- Louann Poirier-Bergeron 2 ,

- Rose-Alice Poulin-Rheault 2 ,

- Catherine Fallon 2 , 4 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4114-8971 Andrea C Tricco 5 , 6 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4192-0682 Holly O Witteman 2 , 3

- 1 Prairie Climate Centre , The University of Winnipeg , Winnipeg , Manitoba , Canada

- 2 Faculty of Medicine , Université Laval , Quebec , QC , Canada

- 3 VITAM Research Centre for Sustainable Health , Quebec , QC , Canada

- 4 CHUQ Research Centre , Quebec , QC , Canada

- 5 Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute , Toronto , Ontario , Canada

- 6 Dalla Lana School of Public Health , University of Toronto , Toronto , Ontario , Canada

- Correspondence to Dr Rhea J Rocque; rhea.rocque{at}gmail.com

Objectives We aimed to develop a systematic synthesis of systematic reviews of health impacts of climate change, by synthesising studies’ characteristics, climate impacts, health outcomes and key findings.

Design We conducted an overview of systematic reviews of health impacts of climate change. We registered our review in PROSPERO (CRD42019145972). No ethical approval was required since we used secondary data. Additional data are not available.

Data sources On 22 June 2019, we searched Medline, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Embase, Cochrane and Web of Science.

Eligibility criteria We included systematic reviews that explored at least one health impact of climate change.

Data extraction and synthesis We organised systematic reviews according to their key characteristics, including geographical regions, year of publication and authors’ affiliations. We mapped the climate effects and health outcomes being studied and synthesised major findings. We used a modified version of A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews-2 (AMSTAR-2) to assess the quality of studies.

Results We included 94 systematic reviews. Most were published after 2015 and approximately one-fifth contained meta-analyses. Reviews synthesised evidence about five categories of climate impacts; the two most common were meteorological and extreme weather events. Reviews covered 10 health outcome categories; the 3 most common were (1) infectious diseases, (2) mortality and (3) respiratory, cardiovascular or neurological outcomes. Most reviews suggested a deleterious impact of climate change on multiple adverse health outcomes, although the majority also called for more research.

Conclusions Most systematic reviews suggest that climate change is associated with worse human health. This study provides a comprehensive higher order summary of research on health impacts of climate change. Study limitations include possible missed relevant reviews, no meta-meta-analyses, and no assessment of overlap. Future research could explore the potential explanations between these associations to propose adaptation and mitigation strategies and could include broader sociopsychological health impacts of climate change.

- public health

- social medicine

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable as no datasets generated and/or analysed for this study. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information. Additional data are not available.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-046333

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Strengths and limitations of this study

A strength of this study is that it provides the first broad overview of previous systematic reviews exploring the health impacts of climate change. By targeting systematic reviews, we achieve a higher order summary of findings than what would have been possible by consulting individual original studies.

By synthesising findings across all included studies and according to the combination of climate impact and health outcome, we offer a clear, detailed and unique summary of the current state of evidence and knowledge gaps about how climate change may influence human health.

A limitation of this study is that we were unable to access some full texts and therefore some studies were excluded, even though we deemed them potentially relevant after title and abstract inspection.

Another limitation is that we could not conduct meta-meta-analyses of findings across reviews, due to the heterogeneity of the included systematic reviews and the relatively small proportion of studies reporting meta-analytic findings.

Finally, the date of the systematic search is a limitation, as we conducted the search in June 2019.

Introduction

The environmental consequences of climate change such as sea-level rise, increasing temperatures, more extreme weather events, increased droughts, flooding and wildfires are impacting human health and lives. 1 2 Previous studies and reviews have documented the multiple health impacts of climate change, including an increase in infectious diseases, respiratory disorders, heat-related morbidity and mortality, undernutrition due to food insecurity, and adverse health outcomes ensuing from increased sociopolitical tension and conflicts. 2–5 Indeed, the most recent Lancet Countdown report, 2 which investigates 43 indicators of the relationship between climate change and human health, arrived at their most worrisome findings since the beginning of their on-going annual work. This report underlines that the health impacts of climate change continue to worsen and are being felt on every continent, although they are having a disproportionate and unequal impact on populations. 2 Authors caution that these health impacts will continue to worsen unless we see an immediate international response to limiting climate change.

To guide future research and action to mitigate and adapt to the health impacts of climate change and its environmental consequences, we need a complete and thorough overview of the research already conducted regarding the health impacts of climate change. Although the number of original studies researching the health impacts of climate change has greatly increased in the recent decade, 2 these do not allow for an in-depth overview of the current literature on the topic. Systematic reviews, on the other hand, allow a higher order overview of the literature. Although previous systematic reviews have been conducted on the health impacts of climate change, these tend to focus on specific climate effects (eg, impact of wildfires on health), 6 7 health impacts (eg, occupational health outcomes), 8 9 countries, 10–12 or are no longer up to date, 13 14 thus limiting our global understanding of what is currently known about the multiple health impacts of climate change across the world.

In this study, we aimed to develop such a complete overview by synthesising systematic reviews of health impacts of climate change. This higher order overview of the literature will allow us to better prepare for the worsening health impacts of climate change, by identifying and describing the diversity and range of health impacts studied, as well as by identifying gaps in previous research. Our research objectives were to synthesise studies’ characteristics such as geographical regions, years of publication, and authors’ affiliations, to map the climate impacts, health outcomes, and combinations of these that have been studied, and to synthesise key findings.

We applied the Cochrane method for overviews of reviews. 15 This method is designed to systematically map the themes of studies on a topic and synthesise findings to achieve a broader overview of the available literature on the topic.

Research questions

Our research questions were the following: (1) What is known about the relationship between climate change and health, as shown in previous systematic reviews? (2) What are the characteristics of these studies? We registered our plan (CRD42019145972 16 ) in PROSPERO, an international prospective register of systematic reviews and followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 17 to report our findings, as a reporting guideline for overviews is still in development. 18

Search strategy and selection criteria

To identify relevant studies, we used a systematic search strategy. There were two inclusion criteria. We included studies in this review if they (1) were systematic reviews of original research and (2) reported at least one health impact as it related (directly or indirectly) to climate change.

We defined a systematic review, based on Cochrane’s definition, as a review of the literature in which one ‘attempts to identify, appraise and synthesize all the empirical evidence that meets pre-specified eligibility criteria to answer a specific research question [by] us[ing] explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view aimed at minimizing bias, to produce more reliable findings to inform decision making’. 19 We included systematic reviews of original research, with or without meta-analyses. We excluded narrative reviews, non-systematic literature reviews and systematic reviews of materials that were not original research (eg, systematic reviews of guidelines.)

We based our definition of health impacts on the WHO’s definition of health as, ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. 20 Therefore, health impacts included, among others, morbidity, mortality, new conditions, worsening/improving conditions, injuries and psychological well-being. Included studies could refer to climate change or global warming directly or indirectly, for instance, by synthesising the direct or indirect health effects of temperature rises or of natural conditions/disasters made more likely by climate change (eg, floods, wildfires, temperature variability, droughts.) Although climate change and global warming are not equivalent terms, in an effort to avoid missing relevant literature, we included studies using either term. We included systematic reviews whose main focus was not the health impacts of climate change, providing they reported at least one result regarding health effects related to climate change (or consequences of climate change.) We excluded studies if they did not report at least one health effect of climate change. For instance, we excluded studies which reported on existing measures of health impacts of climate change (and not the health impact itself) and studies which reported on certain health impacts without a mention of climate change, global warming or environmental consequences made more likely by climate change.

On 22 June 2019, we retrieved systematic reviews regarding the health effects of climate change by searching from inception the electronic databases Medline, CINAHL, Embase, Cochrane, Web of Science using a structured search (see online supplemental appendix 1 for final search strategy developed by a librarian.) We did not apply language restrictions. After removing duplicates, we imported references into Covidence. 21

Supplemental material

Screening process and data extraction.

To select studies, two trained analysts first screened independently titles and abstracts to eliminate articles that did not meet our inclusion criteria. Next, the two analysts independently screened the full text of each article. A senior analyst resolved any conflict or disagreement.

Next, we decided on key information that needed to be extracted from studies. We extracted the first author’s name, year of publication, number of studies included, time frame (in years) of the studies included in the article, first author’s institution’s country affiliation, whether the systematic review included a meta-analysis, geographical focus, population focus, the climate impact(s) and the health outcome(s) as well as the main findings and limitations of each systematic review.

Two or more trained analysts (RR, CB, RN, LC, LPB, RAPR) independently extracted data, using Covidence and spreadsheet software (Google Sheets). An additional trained analyst from the group or senior research team member resolved disagreements between individual judgments.

Coding and data mapping

To summarise findings from previous reviews, we first mapped articles according to climate impacts and health outcomes. To develop the categories of climate impacts and health outcomes, two researchers (RR and LC) consulted the titles and abstracts of each article. We started by identifying categories directly based on our data and finalised our categories by consulting previous conceptual frameworks of climate impacts and health outcomes. 1 22 23 The same two researchers independently coded each article according to their climate impact and health outcome. We then compared coding and resolved disagreements through discussion.

Next, using spreadsheet software, we created a matrix to map articles according to their combination of climate impacts and health outcomes. Each health outcome occupied one row, whereas climate impacts each occupied one column. We placed each article in the matrix according to the combination(s) of their climate impact(s) and health outcome(s). For instance, if we coded an article as ‘extreme weather’ for climate and ‘mental health’ for health impact, we noted the reference of this article in the cell at the intersection of these two codes. We calculated frequencies for each cell to identify frequent combinations and gaps in literature. Because one study could investigate more than one climate impact and health outcome, the frequency counts for each category could exceed the number of studies included in this review.

Finally, we re-read the Results and Discussion sections of each article to summarise findings of the studies. We first wrote an individual summary for each study, then we collated the summaries of all studies exploring the same combination of categories to develop an overall summary of findings for each combination of categories.

Quality assessment

We used a modified version of AMSTAR-2 to assess the quality of the included systematic reviews ( online supplemental appendix 2 ). The purpose of this assessment was to evaluate the quality of the included studies as a whole to get a sense of the overall quality of evidence in this field. Therefore, individual quality scores were not compiled for each article, but scores were aggregated according to items. Since AMSTAR-2 was developed for syntheses of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials, working with a team member with expertise in knowledge synthesis (AT), we adapted it to suit a research context that is not amenable to randomised controlled trials. For instance, we changed assessing and accounting for risk of bias in studies’ included randomised controlled trials to assessing and accounting for limitations in studies’ included articles. Complete modifications are presented in online supplemental appendix 2 .

Patient and public involvement

Patients and members of the public were not involved in this study.

Articles identified

As shown in the PRISMA diagram in figure 1 , from an initial set of 2619 references, we retained 94 for inclusion. More precisely, following screening of titles and abstracts, 146 studies remained for full-text inspection. During full-text inspection, we excluded 52 studies, as they did not report a direct health effect of climate change (n=17), did not relate to climate change (n=15), were not systematic reviews (n=10), or we could not retrieve the full text (n=10).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

The flow chart for included articles in this review.

Study descriptions

A detailed table of all articles and their characteristics can be found in online supplemental appendix 3 . Publication years ranged from 2007 to 2019 (year of data extraction), with the great majority of included articles (n=69; 73%) published since 2015 ( figure 2 ). A median of 30 studies had been included in the systematic reviews (mean=60; SD=49; range 7–722). Approximately one-fifth of the systematic reviews included meta-analyses of their included studies (n=18; 19%). The majority of included systematic reviews’ first authors had affiliations in high-income countries, with the largest representations by continent in Europe (n=30) and Australia (n=24) ( figure 3 ). Countries of origin by continents include (from highest to lowest frequency, then by alphabetical order): Europe (30); UK (9), Germany (6), Italy (4), Sweden (4), Denmark (2), France (2), Georgia (1), Greece (1) and Finland (1); Australia (24); Asia (21); China (11), Iran (4), India (1), Jordan (1), Korea (1), Nepal (1), Philippines (1), Taiwan (1); North America (16); USA (15), Canada (1); Africa (2); Ethiopia (1), Ghana (1), and South America (1); Brazil (1).

Number of included systematic reviews by year of publication.

Number of publications according to geographical affiliation of the first author.

Regarding the geographical focus of systematic reviews, most of the included studies (n=68; 72%) had a global focus or no specified geographical limitations and therefore included studies published anywhere in the world. The remaining systematic reviews either targeted certain countries (n=12) (1 for each Australia, Germany, Iran, India, Ethiopia, Malaysia, Nepal, New Zealand and 2 reviews focused on China and the USA), continents (n=5) (3 focused on Europe and 2 on Asia), or regions according to geographical location (n=6) (1 focused on Sub-Saharan Africa, 1 on Eastern Mediterranean countries, 1 on Tropical countries, and 3 focused on the Arctic), or according to the country’s level of income (n=3) (2 on low to middle income countries, 1 on high income countries).

Regarding specific populations of interest, most of the systematic reviews did not define a specific population of interest (n=69; 73%). For the studies that specified a population of interest (n=25; 26.6%), the most frequent populations were children (n=7) and workers (n=6), followed by vulnerable or susceptible populations more generally (n=4), the elderly (n=3), pregnant people (n=2), people with disabilities or chronic illnesses (n=2) and rural populations (n=1).

We assessed studies for quality according to our revised AMSTAR-2. Complete scores for each article and each item are available in online supplemental appendix 4 . Out of 94 systematic reviews, the most commonly fully satisfied criterion was #1 (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome (PICO) components) with 81/94 (86%) of included systematic reviews fully satisfying this criterion. The next most commonly satisfied criteria were #16 (potential sources of conflict of interest reported) (78/94=83% fully), #13 (account for limitations in individual studies) (70/94=75% fully and 2/94=2% partially), #7 (explain both inclusion and exclusion criteria) (64/94=68% fully and 19/94=20% partially), #8 (description of included studies in adequate detail) (36/94=38% fully and 41/94=44% partially), and #4 (use of a comprehensive literature search strategy) (0/94=0% fully and 80/94=85% partially). For criteria #11, #12, and #15, which only applied to reviews including meta-analyses, 17/18 (94%) fully satisfied criterion #11 (use of an appropriate methods for statistical combination of results), 12/18 (67%) fully satisfied criterion #12 (assessment of the potential impact of Risk of Bias (RoB) in individual studies) (1/18=6% partially), and 11/18 (61%) fully satisfied criterion #15 (an adequate investigation of publication bias, small study bias).

Climate impacts and health outcomes

Regarding climate impacts, we identified 5 mutually exclusive categories, with 13 publications targeting more than one category of climate impacts: (1) meteorological (n=71 papers) (eg, temperature, heat waves, humidity, precipitation, sunlight, wind, air pressure), (2) extreme weather (n=24) (eg, water-related, floods, cyclones, hurricanes, drought), (3) air quality (n=7) (eg, air pollution and wildfire smoke exposure), (4) general (n=5), and (5) other (n=3). Although heat waves could be considered an extreme weather event, papers investigating heat waves’ impact on health were classified in the meteorological impact category, since some of these studies treated them with high temperature. ‘General’ climate impacts included articles that did not specify climate change impacts but stated general climate change as their focus. ‘Other’ climate impacts included studies investigating other effects indirectly related to climate change (eg, impact of environmental contaminants) or general environmental risk factors (eg, environmental hazards, sanitation and access to clean water.)

We identified 10 categories to describe the health outcomes studied by the systematic reviews, and 29 publications targeted more than one category of health outcomes: (1) infectious diseases (n=41 papers) (vector borne, food borne and water borne), (2) mortality (n=32), (3) respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological (n=23), (4) healthcare systems (n=16), 5) mental health (n=13), (6) pregnancy and birth (n=11), 7) nutritional (n=9), (8) skin diseases and allergies (n=8), (9) occupational health and injuries (n=6) and (10) other health outcomes (n=17) (eg, sleep, arthritis, disability-adjusted life years, non-occupational injuries, etc)

Figure 4 depicts the combinations of climate impact and health outcome for each study, with online supplemental appendix 5 offering further details. The five most common combinations are studies investigating the (1) meteorological impacts on infectious diseases (n=35), (2) mortality (n=24) and (3) respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological outcomes (n=17), (4) extreme weather events’ impacts on infectious diseases (n=14), and (5) meteorological impacts on health systems (n=11).

Summary of the combination of climate impact and health outcome (frequencies). The total frequency for one category of health outcome could exceed the number of publications included in this health outcome, since one publication could explore the health impact according to more than one climate factor (eg, one publication could explore both the impact of extreme weather events and temperature on mental health).

For studies investigating meteorological impacts on health, the three most common health outcomes studied were impacts on (1) infectious diseases (n=35), (2) mortality (n=24) and (3) respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological outcomes (n=17). Extreme weather event studies most commonly reported health outcomes related to (1) infectious diseases (n=14), (2) mental health outcomes (n=9) and (3) nutritional outcomes (n=6) and other health outcomes (eg, injuries, sleep) (n=6). Studies focused on the impact of air quality were less frequent and explored mostly health outcomes linked to (1) respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological outcomes (n=6), (2) mortality (n=5) and (3) pregnancy and birth outcomes (n=3).

Summary of findings

Most reviews suggest a deleterious impact of climate change on multiple adverse health outcomes, with some associations being explored and/or supported with consistent findings more often than others. Some reviews also report conflicting findings or an absence of association between the climate impact and health outcome studied (see table 1 for a detailed summary of findings according to health outcomes).

- View inline

Summary of findings from systematic reviews according to health outcome and climate impact

Notable findings of health outcomes according to climate impact include the following. For meteorological factors (n=71), temperature and humidity are the variables most often studied and report the most consistent associations with infectious diseases and respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological outcomes. Temperature is also consistently associated with mortality and healthcare service use. Some associations are less frequently studied, but remain consistent, including the association between some meteorological factors (eg, temperature and heat) and some adverse mental health outcomes (eg, hospital admissions for mental health reasons, suicide, exacerbation of previous mental health conditions), and the association between heat and adverse occupational outcomes and some adverse birth outcomes. Temperature is also associated with adverse nutritional outcomes (likely via crop production and food insecurity) and temperature and humidity are associated with some skin diseases and allergies. Some health outcomes are less frequently studied, but studies suggest an association between temperature and diabetes, impaired sleep, cataracts, heat stress, heat exhaustion and renal diseases.

Extreme weather events (n=24) are consistently associated with mortality, some mental health outcomes (eg, distress, anxiety, depression) and adverse nutritional outcomes (likely via crop production and food insecurity). Some associations are explored less frequently, but these studies suggest an association between drought and respiratory and cardiovascular outcomes (likely via air quality), between extreme weather events and an increased use of healthcare services and some adverse birth outcomes (likely due to indirect causes, such as experiencing stress). Some health outcomes are less frequently studied, but studies suggest an association between extreme weather events and injuries, impaired sleep, oesophageal cancer and exacerbation of chronic illnesses. There are limited and conflicting findings for the association between extreme weather events and infectious diseases, as well as for certain mental health outcomes (eg, suicide and substance abuse). At times, different types of extreme weather events (eg, drought vs flood) led to conflicting findings for some health outcomes (eg, mental health outcomes, infectious diseases), but for other health outcomes, the association was consistent independently of the extreme weather event studied (eg, mortality, healthcare service use and nutritional outcomes).

The impact of air quality on health (n=7) was less frequently studied, but the few studies exploring this association report consistent findings regarding an association with respiratory-specific mortality, adverse respiratory outcomes and an increase in healthcare service use. There is limited evidence regarding the association between air quality and cardiovascular outcomes, limited and inconsistent evidence between wildfire smoke exposure and adverse birth outcomes, and no association is found between exposure to wildfire smoke and increase in use of health services for mental health reasons. Only one review explored the impact of wildfire smoke exposure on ophthalmic outcomes, and it suggests that it may be associated with eye irritation and cataracts.

Reviews which stated climate change as their general focus and did not specify the climate impact(s) under study were less frequent (n=5), but they suggest an association between climate change and pollen allergies in Europe, increased use of healthcare services, obesity, skin diseases and allergies and an association with disability-adjusted life years. Reviews investigating the impact of other climate-related factors (n=3) show inconsistent findings concerning the association between environmental pollutant and adverse birth outcomes, and two reviews suggest an association between environmental risk factors and pollutants and childhood stunting and occupational diseases.

Most reviews concluded by calling for more research, noting the limitations observed among the studies included in their reviews, as well as limitations in their reviews themselves. These limitations included, among others, some systematic reviews having a small number of publications, 24 25 language restrictions such as including only papers in English, 26 27 arriving at conflicting evidence, 28 difficulty concluding a strong association due to the heterogeneity in methods and measurements or the limited equipment and access to quality data in certain contexts, 24 29–31 and most studies included were conducted in high-income countries. 32 33

Previous authors also discussed the important challenge related to exploring the relationship between climate change and health. Not only is it difficult to explore the potential causal relationship between climate change and health, mostly due to methodological challenges, but there are also a wide variety of complex causal factors that may interact to determine health outcomes. Therefore, the possible causal mechanisms underlying these associations were at times still unknown or uncertain and the impacts of some climate factors were different according to geographical location and specificities of the context. Nonetheless, some reviews offered potential explanations for the climate-health association, with the climate factor at times, having a direct impact on health (eg, flooding causing injuries, heat causing dehydration) and in other cases, having an indirect impact (eg, flooding causing stress which in turn may cause adverse birth outcomes, heat causing difficulty concentrating leading to occupational injuries.)

Principal results

In this overview of systematic reviews, we aimed to develop a synthesis of systematic reviews of health impacts of climate change by mapping the characteristics and findings of studies exploring the relationship between climate change and health. We identified four key findings.

First, meteorological impacts, mostly related to temperature and humidity, were the most common impacts studied by included publications, which aligns with findings from a previous scoping review on the health impacts of climate change in the Philippines. 10 Indeed, meteorological factors’ impact on all health outcomes identified in this review are explored, although some health outcomes are more rarely explored (eg, mental health and nutritional outcomes). Although this may not be surprising given that a key implication of climate change is the long-term meteorological impact of temperature rise, this finding suggests we also need to undertake research focused on other climate impacts on health, including potential direct and indirect effects of temperature rise, such as the impact of droughts and wildfire smoke. This will allow us to better prepare for the health crises that arise from these ever-increasing climate-related impacts. For instance, the impacts of extreme weather events and air quality on certain health outcomes are not explored (eg, skin diseases and allergies, occupational health) or only rarely explored (eg, pregnancy outcomes).

Second, systematic reviews primarily focus on physical health outcomes, such as infectious diseases, mortality, and respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological outcomes, which also aligns with the country-specific previous scoping review. 10 Regarding mortality, we support Campbell and colleagues’ 34 suggestion that we should expand our focus to include other types of health outcomes. This will provide better support for mitigation policies and allow us to adapt to the full range of threats of climate change.

Moreover, it is unclear whether the distribution of frequencies of health outcomes reflects the actual burden of health impacts of climate change. The most commonly studied health outcomes do not necessarily reflect the definition of health presented by the WHO as, ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. 20 This suggests that future studies should investigate in greater depth the impacts of climate change on mental and broader social well-being. Indeed, some reviews suggested that climate change impacts psychological and social well-being, via broader consequences, such as political instability, health system capacity, migration, and crime, 3 4 35 36 thus illustrating how our personal health is determined not only by biological and environmental factors but also by social and health systems. The importance of expanding our scope of health in this field is also recognised in the most recent Lancet report, which states that future reports will include a new mental health indicator. 2

Interestingly, the reviews that explored the mental health impacts of climate change were focused mostly on the direct and immediate impacts of experiencing extreme weather events. However, psychologists are also warning about the long-term indirect mental health impacts of climate change, which are becoming more prevalent for children and adults alike (eg, eco-anxiety, climate depression). 37 38 Even people who do not experience direct climate impacts, such as extreme weather events, report experiencing distressing emotions when thinking of the destruction of our environment or when worrying about one’s uncertain future and the lack of actions being taken. To foster emotional resilience in the face of climate change, these mental health impacts of climate change need to be further explored. Humanity’s ability to adapt to and mitigate climate change ultimately depends on our emotional capacity to face this threat.

Third, there is a notable geographical difference in the country affiliations of first authors, with three quarters of systematic reviews having been led by first authors affiliated to institutions in Europe, Australia, or North America, which aligns with the findings of the most recent Lancet report. 2 While perhaps unsurprising given the inequalities in research funding and institutions concentrated in Western countries, this is of critical importance given the significant health impacts that are currently faced (and will remain) in other parts of the world. Research funding organisations should seek to provide more resources to authors in low-income to middle-income countries to ensure their expertise and perspectives are better represented in the literature.

Fourth, overall, most reviews suggest an association between climate change and the deterioration of health in various ways, illustrating the interdependence of our health and well-being with the well-being of our environment. This interdependence may be direct (eg, heat’s impact on dehydration and exhaustion) or indirect (eg, via behaviour change due to heat.) The most frequently explored and consistently supported associations include an association between temperature and humidity with infectious diseases, mortality and adverse respiratory, cardiovascular and neurological outcomes. Other less frequently studied but consistent associations include associations between climate impacts and increased use of healthcare services, some adverse mental health outcomes, adverse nutritional outcomes and adverse occupational health outcomes. These associations support key findings of the most recent Lancet report, in which authors report, among others, increasing heat exposure being associated with increasing morbidities and mortality, climate change leading to food insecurity and undernutrition, and to an increase in infectious disease transmission. 2

That said, a number of reviews included in this study reported limited, conflicting and/or an absence of evidence regarding the association between the climate impact and health outcome. For instance, there was conflicting or limited evidence concerning the association between extreme weather events and infectious diseases, cardiorespiratory outcomes and some mental health outcomes and the association between air quality and cardiovascular-specific mortality and adverse birth outcomes. These conflicting and limited findings highlight the need for further research. These associations are complex and there exist important methodological challenges inherent to exploring the causal relationship between climate change and health outcomes. This relationship may at times be indirect and likely determined by multiple interacting factors.

The climate-health link has been the target of more research in recent years and it is also receiving increasing attention from the public and in both public health and climate communication literature. 2 39–41 However, the health framing of climate change information is still underused in climate communications, and researchers suggest we should be doing more to make the link between human health and climate change more explicit to increase engagement with the climate crisis. 2 41–43 The health framing of climate communication also has implications for healthcare professionals 44 and policy-makers, as these actors could play a key part in climate communication, adaptation and mitigation. 41 42 45 These key stakeholders’ perspectives on the climate-health link, as well as their perceived role in climate adaptation and mitigation could be explored, 46 since research suggests that health professionals are important voices in climate communications 44 and especially since, ultimately, these adverse health outcomes will engender pressure on and cost to our health systems and health workers.

Strengths and limitations

To the best of our knowledge, the current study provides the first broad overview of previous systematic reviews exploring the health impacts of climate change. Our review has three main strengths. First, by targeting systematic reviews, we achieve a higher order summary of findings than what would have been possible by consulting individual original studies. Second, by synthesising findings across all included studies and according to the combination of climate impact and health outcome, we offer a clear, detailed and unique summary of the current state of evidence and knowledge gaps about how climate change may influence human health. This summary may be of use to researchers, policy-makers and communities. Third, we included studies published in all languages about any climate impact and any health outcome. In doing so, we provide a comprehensive and robust overview.

Our work has four main limitations. First, we were unable to access some full texts and therefore some studies were excluded, even though we deemed them potentially relevant after title and abstract inspection. Other potentially relevant systematic reviews may be missing due to unseen flaws in our systematic search. Second, due to the heterogeneity of the included systematic reviews and the relatively small proportion of studies reporting meta-analytic findings, we could not conduct meta-meta-analyses of findings across reviews. Future research is needed to quantify the climate and health links described in this review, as well as to investigate the causal relationship and other interacting factors. Third, due to limited resources, we did not assess overlap between the included reviews concerning the studies they included. Frequencies and findings should be interpreted with potential overlap in mind. Fourth, we conducted the systematic search of the literature in June 2019, and it is therefore likely that some recent systematic reviews are not included in this study.

Conclusions

Overall, most systematic reviews of the health impacts of climate change suggest an association between climate change and the deterioration of health in multiple ways, generally in the direction that climate change is associated with adverse human health outcomes. This is worrisome since these outcomes are predicted to rise in the near future, due to the rise in temperature and increase in climate-change-related events such as extreme weather events and worsened air quality. Most studies included in this review focused on meteorological impacts of climate change on adverse physical health outcomes. Future studies could fill knowledge gaps by exploring other climate-related impacts and broader psychosocial health outcomes. Moreover, studies on health impacts of climate change have mostly been conducted by first authors affiliated with institutions in high-income countries. This inequity needs to be addressed, considering that the impacts of climate change are and will continue to predominantly impact lower income countries. Finally, although most reviews also recommend more research to better understand and quantify these associations, to adapt to and mitigate climate change’s impacts on health, it will also be important to unpack the ‘what, how, and where’ of these effects. Health effects of climate change are unlikely to be distributed equally or randomly through populations. It will be important to mitigate the changing climate’s potential to exacerbate health inequities.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not required.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contributions of Selma Chipenda Dansokho, as research associate, and Thierry Provencher, as research assistant, to this project, and of Frederic Bergeron, for assistance with search strategy, screening and selection of articles for the systematic review.

- Portier C ,

- Arnell N , et al

- Hsiang SM ,

- Frumkin H ,

- Holloway T , et al

- Alderman K ,

- Turner LR ,

- Coates SJ ,

- Davis MDP ,

- Andersen LK

- Jin H , et al

- Azizi M , et al

- Dorotan MM ,

- Sigua JA , et al

- Mcintyre M , et al

- Liu J , et al

- Herlihy N ,

- Bar-Hen A ,

- Verner G , et al

- Hosking J ,

- Campbell-Lendrum D

- Pollock M ,

- Fernandes RM ,

- Witteman HO ,

- Dansokho SC ,

- McKenzie J ,

- Pieper D , et al

- ↵ About Cochrane reviews . Available: https://www.cochranelibrary.com/about/about-cochrane-reviews [Accessed 14 Sept 2020 ].

- World Health Organization

- ↵ Covidence systematic review software . Available: www.covidence.org

- Schlosberg D , et al

- Amegah AK ,

- Jaakkola JJK

- Zheng S , et al

- Leyva EWA ,

- Davidson PM

- Phalkey RK ,

- Aranda-Jan C ,

- Marx S , et al

- Porpora MG ,

- Piacenti I ,

- Scaramuzzino S , et al

- Morton LC ,

- Zhu R , et al

- Rutherford S , et al

- Klinger C ,

- Xu D , et al

- Campbell S ,

- Remenyi TA ,

- White CJ , et al

- Palmer J , et al

- Benevolenza MA ,

- Davenport L

- Maibach EW ,

- Baldwin P , et al

- Schütte S ,

- Nisbet MC ,

- Maibach EW , et al

- Costello A ,

- Montgomery H ,

- Hess J , et al

- Berhane K ,

- Bernhardt V ,

- Finkelmeier F ,

- Verhoff MA , et al

- de Sousa TCM ,

- Amancio F ,

- Hacon SdeS , et al

- Bai Z , et al

- Roda Gracia J ,

- Schumann B ,

- Hedlund C ,

- Blomstedt Y ,

- Aghamohammadi N , et al

- Khader YS ,

- Abdelrahman M ,

- Abdo N , et al

- Matysiak A ,

- Mackenzie JS , et al

- Nichols A ,

- Maynard V ,

- Goodman B , et al

- Tong S , et al

- Swynghedauw B

- Emelyanova A ,

- Oksanen A , et al

- Su H , et al

- Mengersen K ,

- Dale P , et al

- Veenema TG ,

- Thornton CP ,

- Lavin RP , et al

- Gatton ML ,

- Ghazani M ,

- FitzGerald G ,

- Hu W , et al

- Lu Y , et al

- Fearnley E ,

- Woster AP ,

- Goldstein RS , et al

- Philipsborn R ,

- Brosi BJ , et al

- Semenza JC ,

- Rechenburg A , et al

- Stensgaard A-S ,

- Vounatsou P ,

- Sengupta ME , et al

- Shipp-Hilts A ,

- Eidson M , et al

- Thomas DR ,

- Salmon RL , et al

- Prudhomme C , et al

- Wildenhain J ,

- Vandenbergh A , et al

- Barnett AG ,

- Wang X , et al

- Ghanizadeh G ,

- Heidari M ,

- Lawton EM ,

- Liang R , et al

- Moghadamnia MT ,

- Ardalan A ,

- Mesdaghinia A , et al

- Parthasarathy R ,

- Krishnan A , et al

- Sanderson M ,

- Arbuthnott K ,

- Kovats S , et al

- Schubert AJ ,

- Jehn M , et al

- Sheffield PE ,

- Guo Y , et al

- Daniels A , et al

- Madaniyazi L ,

- Yu W , et al

- Pereira G ,

- Uhl SA , et al

- Johnston FH , et al

- Youssouf H ,

- Liousse C ,

- Roblou L , et al

- Agnew M , et al

- Zhang Y , et al

- Crooks JL ,

- Davies JM , et al

- Sawatzky A ,

- Cunsolo A ,

- Jones-Bitton A , et al

- Duan J , et al

- Kunzweiler K ,

- Garthus-Niegel S

- Fernandez A ,

- Jones M , et al

- Saha S , et al

- Carolan-Olah M ,

- Frankowska D

- McCormick S

- Poursafa P ,

- Kelishadi R

- Vilcins D ,

- Huang K-C ,

- Yang T-Y , et al

- Augustin J ,

- Franzke N ,

- Augustin M , et al

- Binazzi A ,

- Bonafede M , et al

- Bonafede M ,

- Marinaccio A ,

- Asta F , et al

- Flouris AD ,

- Ioannou LG , et al

- Kjellstrom T ,

- Baldasseroni A

- Varghese BM ,

- Bi P , et al

- Wimalawansa SA ,

- Wimalawansa SJ

- Ahn HS , et al

- Otte im Kampe E ,

- Rifkin DI ,

Supplementary materials

Supplementary data.

This web only file has been produced by the BMJ Publishing Group from an electronic file supplied by the author(s) and has not been edited for content.

- Data supplement 1

- Data supplement 2

- Data supplement 3

- Data supplement 4

- Data supplement 5

Twitter @RutNdjab, @ATricco, @hwitteman

Contributors RN, CF, ACT, HOW contributed to the design of the study. CB, RN, LPB, RAPR and HOW contributed to the systematic search of the literature and selection of studies. RR, HOW, LC conducted data analysis and interpretation. RR and HOW drafted the first version of the article with early revision by CB, LC and RN. All authors critically revised the article and approved the final version for submission for publication. RR and HOW had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Funding This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) FDN-148426. The CIHR had no role in determining the study design, the plans for data collection or analysis, the decision to publish, nor the preparation of this manuscript. ACT is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Knowledge Synthesis. HOW is funded by a Tier 2 Canada Research Chair in Human-Centred Digital Health.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Newsroom Post

Climate change: a threat to human wellbeing and health of the planet. taking action now can secure our future.

BERLIN, Feb 28 – Human-induced climate change is causing dangerous and widespread disruption in nature and affecting the lives of billions of people around the world, despite efforts to reduce the risks. People and ecosystems least able to cope are being hardest hit, said scientists in the latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, released today.

“This report is a dire warning about the consequences of inaction,” said Hoesung Lee, Chair of the IPCC. “It shows that climate change is a grave and mounting threat to our wellbeing and a healthy planet. Our actions today will shape how people adapt and nature responds to increasing climate risks.”

The world faces unavoidable multiple climate hazards over the next two decades with global warming of 1.5°C (2.7°F). Even temporarily exceeding this warming level will result in additional severe impacts, some of which will be irreversible. Risks for society will increase, including to infrastructure and low-lying coastal settlements.

The Summary for Policymakers of the IPCC Working Group II report, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability was approved on Sunday, February 27 2022, by 195 member governments of the IPCC, through a virtual approval session that was held over two weeks starting on February 14.

Urgent action required to deal with increasing risks

Increased heatwaves, droughts and floods are already exceeding plants’ and animals’ tolerance thresholds, driving mass mortalities in species such as trees and corals. These weather extremes are occurring simultaneously, causing cascading impacts that are increasingly difficult to manage. They have exposed millions of people to acute food and water insecurity, especially in Africa, Asia, Central and South America, on Small Islands and in the Arctic.

To avoid mounting loss of life, biodiversity and infrastructure, ambitious, accelerated action is required to adapt to climate change, at the same time as making rapid, deep cuts in greenhouse gas emissions. So far, progress on adaptation is uneven and there are increasing gaps between action taken and what is needed to deal with the increasing risks, the new report finds. These gaps are largest among lower-income populations.

The Working Group II report is the second instalment of the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), which will be completed this year.

“This report recognizes the interdependence of climate, biodiversity and people and integrates natural, social and economic sciences more strongly than earlier IPCC assessments,” said Hoesung Lee. “It emphasizes the urgency of immediate and more ambitious action to address climate risks. Half measures are no longer an option.”

Safeguarding and strengthening nature is key to securing a liveable future

There are options to adapt to a changing climate. This report provides new insights into nature’s potential not only to reduce climate risks but also to improve people’s lives.

“Healthy ecosystems are more resilient to climate change and provide life-critical services such as food and clean water”, said IPCC Working Group II Co-Chair Hans-Otto Pörtner. “By restoring degraded ecosystems and effectively and equitably conserving 30 to 50 per cent of Earth’s land, freshwater and ocean habitats, society can benefit from nature’s capacity to absorb and store carbon, and we can accelerate progress towards sustainable development, but adequate finance and political support are essential.”

Scientists point out that climate change interacts with global trends such as unsustainable use of natural resources, growing urbanization, social inequalities, losses and damages from extreme events and a pandemic, jeopardizing future development.

“Our assessment clearly shows that tackling all these different challenges involves everyone – governments, the private sector, civil society – working together to prioritize risk reduction, as well as equity and justice, in decision-making and investment,” said IPCC Working Group II Co-Chair Debra Roberts.

“In this way, different interests, values and world views can be reconciled. By bringing together scientific and technological know-how as well as Indigenous and local knowledge, solutions will be more effective. Failure to achieve climate resilient and sustainable development will result in a sub-optimal future for people and nature.”

Cities: Hotspots of impacts and risks, but also a crucial part of the solution

This report provides a detailed assessment of climate change impacts, risks and adaptation in cities, where more than half the world’s population lives. People’s health, lives and livelihoods, as well as property and critical infrastructure, including energy and transportation systems, are being increasingly adversely affected by hazards from heatwaves, storms, drought and flooding as well as slow-onset changes, including sea level rise.

“Together, growing urbanization and climate change create complex risks, especially for those cities that already experience poorly planned urban growth, high levels of poverty and unemployment, and a lack of basic services,” Debra Roberts said.

“But cities also provide opportunities for climate action – green buildings, reliable supplies of clean water and renewable energy, and sustainable transport systems that connect urban and rural areas can all lead to a more inclusive, fairer society.”

There is increasing evidence of adaptation that has caused unintended consequences, for example destroying nature, putting peoples’ lives at risk or increasing greenhouse gas emissions. This can be avoided by involving everyone in planning, attention to equity and justice, and drawing on Indigenous and local knowledge.

A narrowing window for action

Climate change is a global challenge that requires local solutions and that’s why the Working Group II contribution to the IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) provides extensive regional information to enable Climate Resilient Development.

The report clearly states Climate Resilient Development is already challenging at current warming levels. It will become more limited if global warming exceeds 1.5°C (2.7°F). In some regions it will be impossible if global warming exceeds 2°C (3.6°F). This key finding underlines the urgency for climate action, focusing on equity and justice. Adequate funding, technology transfer, political commitment and partnership lead to more effective climate change adaptation and emissions reductions.

“The scientific evidence is unequivocal: climate change is a threat to human wellbeing and the health of the planet. Any further delay in concerted global action will miss a brief and rapidly closing window to secure a liveable future,” said Hans-Otto Pörtner.

For more information, please contact:

IPCC Press Office, Email: [email protected] IPCC Working Group II: Sina Löschke, Komila Nabiyeva: [email protected]

Notes for Editors

Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

The Working Group II report examines the impacts of climate change on nature and people around the globe. It explores future impacts at different levels of warming and the resulting risks and offers options to strengthen nature’s and society’s resilience to ongoing climate change, to fight hunger, poverty, and inequality and keep Earth a place worth living on – for current as well as for future generations.

Working Group II introduces several new components in its latest report: One is a special section on climate change impacts, risks and options to act for cities and settlements by the sea, tropical forests, mountains, biodiversity hotspots, dryland and deserts, the Mediterranean as well as the polar regions. Another is an atlas that will present data and findings on observed and projected climate change impacts and risks from global to regional scales, thus offering even more insights for decision makers.

The Summary for Policymakers of the Working Group II contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report (AR6) as well as additional materials and information are available at https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/

Note : Originally scheduled for release in September 2021, the report was delayed for several months by the COVID-19 pandemic, as work in the scientific community including the IPCC shifted online. This is the second time that the IPCC has conducted a virtual approval session for one of its reports.

AR6 Working Group II in numbers

270 authors from 67 countries

- 47 – coordinating authors

- 184 – lead authors

- 39 – review editors

- 675 – contributing authors

Over 34,000 cited references

A total of 62,418 expert and government review comments

(First Order Draft 16,348; Second Order Draft 40,293; Final Government Distribution: 5,777)

More information about the Sixth Assessment Report can be found here .

Additional media resources

Assets available after the embargo is lifted on Media Essentials website .

Press conference recording, collection of sound bites from WGII authors, link to presentation slides, B-roll of approval session, link to launch Trello board including press release and video trailer in UN languages, a social media pack.

The website includes outreach materials such as videos about the IPCC and video recordings from outreach events conducted as webinars or live-streamed events.

Most videos published by the IPCC can be found on our YouTube channel. Credit for artwork

About the IPCC

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the UN body for assessing the science related to climate change. It was established by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) in 1988 to provide political leaders with periodic scientific assessments concerning climate change, its implications and risks, as well as to put forward adaptation and mitigation strategies. In the same year the UN General Assembly endorsed the action by the WMO and UNEP in jointly establishing the IPCC. It has 195 member states.

Thousands of people from all over the world contribute to the work of the IPCC. For the assessment reports, IPCC scientists volunteer their time to assess the thousands of scientific papers published each year to provide a comprehensive summary of what is known about the drivers of climate change, its impacts and future risks, and how adaptation and mitigation can reduce those risks.

The IPCC has three working groups: Working Group I , dealing with the physical science basis of climate change; Working Group II , dealing with impacts, adaptation and vulnerability; and Working Group III , dealing with the mitigation of climate change. It also has a Task Force on National Greenhouse Gas Inventories that develops methodologies for measuring emissions and removals. As part of the IPCC, a Task Group on Data Support for Climate Change Assessments (TG-Data) provides guidance to the Data Distribution Centre (DDC) on curation, traceability, stability, availability and transparency of data and scenarios related to the reports of the IPCC.

IPCC assessments provide governments, at all levels, with scientific information that they can use to develop climate policies. IPCC assessments are a key input into the international negotiations to tackle climate change. IPCC reports are drafted and reviewed in several stages, thus guaranteeing objectivity and transparency. An IPCC assessment report consists of the contributions of the three working groups and a Synthesis Report. The Synthesis Report integrates the findings of the three working group reports and of any special reports prepared in that assessment cycle.

About the Sixth Assessment Cycle

At its 41st Session in February 2015, the IPCC decided to produce a Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). At its 42nd Session in October 2015 it elected a new Bureau that would oversee the work on this report and the Special Reports to be produced in the assessment cycle.

Global Warming of 1.5°C , an IPCC special report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty was launched in October 2018.

Climate Change and Land , an IPCC special report on climate change, desertification, land degradation, sustainable land management, food security, and greenhouse gas fluxes in terrestrial ecosystems was launched in August 2019, and the Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate was released in September 2019.

In May 2019 the IPCC released the 2019 Refinement to the 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories , an update to the methodology used by governments to estimate their greenhouse gas emissions and removals.

In August 2021 the IPCC released the Working Group I contribution to the AR6, Climate Change 2021, the Physical Science Basis

The Working Group III contribution to the AR6 is scheduled for early April 2022.

The Synthesis Report of the Sixth Assessment Report will be completed in the second half of 2022.

For more information go to www.ipcc.ch

Related Content

Remarks by the ipcc chair during the press conference to present the working group ii contribution to the sixth assessment report.

Monday, 28 February 2022 Distinguished representatives of the media, WMO Secretary-General Petteri, UNEP Executive Director Andersen, We have just heard …

February 2022

Fifty-fifth session of the ipcc (ipcc-55) and twelfth session of working group ii (wgii-12), february 14, 2022, working group report, ar6 climate change 2022: impacts, adaptation and vulnerability.

- Ways to Give

- Contact an Expert

- Explore WRI Perspectives

Filter Your Site Experience by Topic

Applying the filters below will filter all articles, data, insights and projects by the topic area you select.

- All Topics Remove filter

- Climate filter site by Climate

- Cities filter site by Cities

- Energy filter site by Energy

- Food filter site by Food

- Forests filter site by Forests

- Freshwater filter site by Freshwater

- Ocean filter site by Ocean

- Business filter site by Business

- Economics filter site by Economics

- Finance filter site by Finance

- Equity & Governance filter site by Equity & Governance

Search WRI.org

Not sure where to find something? Search all of the site's content.

How Climate Change Affects Health and How Countries Can Respond

- Climate Resilience

- adaptation finance

- climate change

- climatewatch-pinned

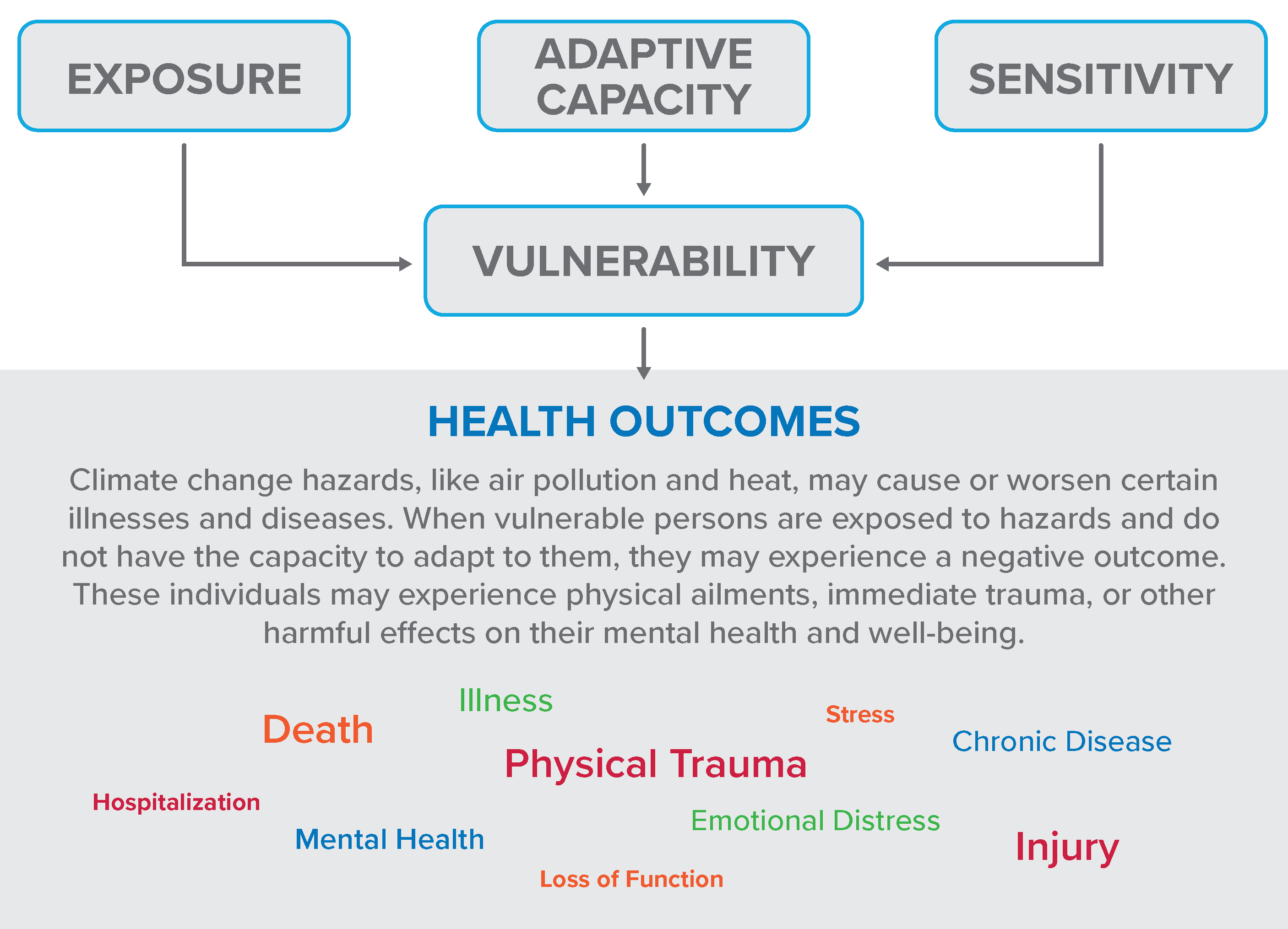

Since early 2020, the world’s attention has been on the global coronavirus pandemic. The pandemic continues to put massive stress on existing health systems, exposing their fault lines. As nations think about how to make health systems more resilient to current and future threats, one threat must not be overlooked: climate change is also impacting human health and straining heavily burdened health services everywhere.