- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game New

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a Good Answer to Exam Essay Questions

Last Updated: March 17, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Tristen Bonacci . Tristen Bonacci is a Licensed English Teacher with more than 20 years of experience. Tristen has taught in both the United States and overseas. She specializes in teaching in a secondary education environment and sharing wisdom with others, no matter the environment. Tristen holds a BA in English Literature from The University of Colorado and an MEd from The University of Phoenix. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 642,921 times.

Answering essay questions on an exam can be difficult and stressful, which can make it hard to provide a good answer. However, you can improve your ability to answer essay questions by learning how to understand the questions, form an answer, and stay focused. Developing your ability to give excellent answers on essay exams will take time and effort, but you can learn some good essay question practices and start improving your answers.

Understanding the Question

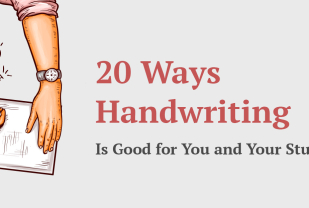

- Analyze: Explain the what, where, who, when, why, and how. Include pros and cons, strengths and weaknesses, etc.

- Compare: Discuss the similarities and differences between two or more things. Don't forget to explain why the comparison is useful.

- Contrast: Discuss how two or more things are different or distinguish between them. Don't forget to explain why the contrast is useful.

- Define: State what something means, does, achieves, etc.

- Describe: List characteristics or traits of something. You may also need to summarize something, such as an essay prompt that asks "Describe the major events that led to the American Revolution."

- Discuss: This is more analytical. You usually begin by describing something and then present arguments for or against it. You may need to analyze the advantages or disadvantages of your subject.

- Evaluate: Offer the pros and cons, positives and negatives for a subject. You may be asked to evaluate a statement for logical support, or evaluate an argument for weaknesses.

- Explain: Explain why or how something happened, or justify your position on something.

- Prove: Usually reserved for more scientific or objective essays. You may be asked to include evidence and research to build a case for a specific position or set of hypotheses.

- Summarize: Usually, this means to list the major ideas or themes of a subject. It could also ask you to present the main ideas in order to then fully discuss them. Most essay questions will not ask for pure summary without anything else.

- Raise your hand and wait for your teacher to come over to you or approach your teacher’s desk to ask your question. This way you will be less likely to disrupt other test takers.

Forming Your Response

- Take a moment to consider your organization before you start writing your answer. What information should come first, second, third, etc.?

- In many cases, the traditional 5-paragraph essay structure works well. Start with an introductory paragraph, use 3 paragraphs in the body of the article to explain different points, and finish with a concluding paragraph.

- It can also be really helpful to draft a quick outline of your essay before you start writing.

- You may want to make a list of facts and figures that you want to include in your essay answer. That way you can refer to this list as you write your answer.

- It's best to write down all the important key topics or ideas before you get started composing your answer. That way, you can check back to make sure you haven't missed anything.

- For example, imagine that your essay question asks: "Should the FIFA World Cup be awarded to countries with human rights violations? Explain and support your answer."

- You might restate this as "Countries with human rights violations should not be awarded the FIFA World Cup because this rewards a nation's poor treatment of its citizens." This will be the thesis that you support with examples and explanation.

- For example, whether you argue that the FIFA World Cup should or should not be awarded to countries with human rights violations, you will want to address the opposing side's argument. However, it needs to be clear where your essay stands about the matter.

- Often, essay questions end up saying things along the lines of "There are many similarities and differences between X and Y." This does not offer a clear position and can result in a bad grade.

- If you are required to write your answer by hand, then take care to make your writing legible and neat. Some professors may deduct points if they cannot read what you have written.

Staying Calm and Focused

- If you get to a point during the exam where you feel too anxious to focus, put down your pencil (or take your hands off of the keyboard), close your eyes, and take a deep breath. Stretch your arms and imagine that you are somewhere pleasant for a few moments. When you have completed this brief exercise, open up your eyes and resume the exam.

- For example, if the exam period is one hour long and you have to answer three questions in that time frame, then you should plan to spend no more than 20 minutes on each question.

- Look at the weight of the questions, if applicable. For example, if there are five 10-point short-answers and a 50-point essay, plan to spend more time on the essay because it is worth significantly more. Don't get stuck spending so much time on the short-answers that you don't have time to develop a complex essay.

- This strategy is even more important if the exam has multiple essay questions. If you take too much time on the first question, then you may not have enough time to answer the other questions on the exam.

- If you feel like you are straying away from the question, reread the question and review any notes that you made to help guide you. After you get refocused, then continue writing your answer.

- Try to allow yourself enough time to go back and tighten up connections between your points. A few well-placed transitions can really bump up your grade.

Community Q&A

- If you are worried about running out of time, put your watch in front of you where you can see it. Just try not to focus on it too much. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

- If you need more practice, make up your own questions or even look at some practice questions online! Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

Tips from our Readers

- Look up relevant quotes if your exam is open notes. Use references from books or class to back up your answers.

- Make sure your sentences flow together and that you don't repeat the same thing twice!

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://www.linnbenton.edu/student-services/library-tutoring-testing/learning-center/academic-coaching/documents/Strategies%20For%20Answering%20Essay%20Questions.pdf

- ↑ https://www.ius.edu/writing-center/files/answering-essay-questions.pdf

- ↑ https://success.uark.edu/get-help/student-resources/short-answer-essays.php

About This Article

To write a good answer to an exam essay question, read the question carefully to find what it's asking, and follow the instructions for the essay closely. Begin your essay by rephrasing the question into a statement with your answer in the statement. Include supplemental facts and figures if necessary, or do textual analysis from a provided piece to support your argument. Make sure your writing is clear and to the point, and don't include extra information unless it supports your argument. For tips from our academic reviewer on understanding essay questions and dealing with testing nerves, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Kristine A.

Did this article help you?

May 29, 2017

Sundari Nandyala

Aug 5, 2016

Oct 1, 2016

Mar 24, 2017

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Don’t miss out! Sign up for

wikiHow’s newsletter

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- Focus and Precision: How to Write Essays that Answer the Question

About the Author Stephanie Allen read Classics and English at St Hugh’s College, Oxford, and is currently researching a PhD in Early Modern Academic Drama at the University of Fribourg.

We’ve all been there. You’ve handed in an essay and you think it’s pretty great: it shows off all your best ideas, and contains points you’re sure no one else will have thought of.

You’re not totally convinced that what you’ve written is relevant to the title you were given – but it’s inventive, original and good. In fact, it might be better than anything that would have responded to the question. But your essay isn’t met with the lavish praise you expected. When it’s tossed back onto your desk, there are huge chunks scored through with red pen, crawling with annotations like little red fire ants: ‘IRRELEVANT’; ‘A bit of a tangent!’; ‘???’; and, right next to your best, most impressive killer point: ‘Right… so?’. The grade your teacher has scrawled at the end is nowhere near what your essay deserves. In fact, it’s pretty average. And the comment at the bottom reads something like, ‘Some good ideas, but you didn’t answer the question!’.

If this has ever happened to you (and it has happened to me, a lot), you’ll know how deeply frustrating it is – and how unfair it can seem. This might just be me, but the exhausting process of researching, having ideas, planning, writing and re-reading makes me steadily more attached to the ideas I have, and the things I’ve managed to put on the page. Each time I scroll back through what I’ve written, or planned, so far, I become steadily more convinced of its brilliance. What started off as a scribbled note in the margin, something extra to think about or to pop in if it could be made to fit the argument, sometimes comes to be backbone of a whole essay – so, when a tutor tells me my inspired paragraph about Ted Hughes’s interpretation of mythology isn’t relevant to my essay on Keats, I fail to see why. Or even if I can see why, the thought of taking it out is wrenching. Who cares if it’s a bit off-topic? It should make my essay stand out, if anything! And an examiner would probably be happy not to read yet another answer that makes exactly the same points. If you recognise yourself in the above, there are two crucial things to realise. The first is that something has to change: because doing well in high school exam or coursework essays is almost totally dependent on being able to pin down and organise lots of ideas so that an examiner can see that they convincingly answer a question. And it’s a real shame to work hard on something, have good ideas, and not get the marks you deserve. Writing a top essay is a very particular and actually quite simple challenge. It’s not actually that important how original you are, how compelling your writing is, how many ideas you get down, or how beautifully you can express yourself (though of course, all these things do have their rightful place). What you’re doing, essentially, is using a limited amount of time and knowledge to really answer a question. It sounds obvious, but a good essay should have the title or question as its focus the whole way through . It should answer it ten times over – in every single paragraph, with every fact or figure. Treat your reader (whether it’s your class teacher or an external examiner) like a child who can’t do any interpretive work of their own; imagine yourself leading them through your essay by the hand, pointing out that you’ve answered the question here , and here , and here. Now, this is all very well, I imagine you objecting, and much easier said than done. But never fear! Structuring an essay that knocks a question on the head is something you can learn to do in a couple of easy steps. In the next few hundred words, I’m going to share with you what I’ve learned through endless, mindless crossings-out, rewordings, rewritings and rethinkings.

Top tips and golden rules

I’ve lost count of the number of times I’ve been told to ‘write the question at the top of every new page’- but for some reason, that trick simply doesn’t work for me. If it doesn’t work for you either, use this three-part process to allow the question to structure your essay:

1) Work out exactly what you’re being asked

It sounds really obvious, but lots of students have trouble answering questions because they don’t take time to figure out exactly what they’re expected to do – instead, they skim-read and then write the essay they want to write. Sussing out a question is a two-part process, and the first part is easy. It means looking at the directions the question provides as to what sort of essay you’re going to write. I call these ‘command phrases’ and will go into more detail about what they mean below. The second part involves identifying key words and phrases.

2) Be as explicit as possible

Use forceful, persuasive language to show how the points you’ve made do answer the question. My main focus so far has been on tangential or irrelevant material – but many students lose marks even though they make great points, because they don’t quite impress how relevant those points are. Again, I’ll talk about how you can do this below.

3) Be brutally honest with yourself about whether a point is relevant before you write it.

It doesn’t matter how impressive, original or interesting it is. It doesn’t matter if you’re panicking, and you can’t think of any points that do answer the question. If a point isn’t relevant, don’t bother with it. It’s a waste of time, and might actually work against you- if you put tangential material in an essay, your reader will struggle to follow the thread of your argument, and lose focus on your really good points.

Put it into action: Step One

Let’s imagine you’re writing an English essay about the role and importance of the three witches in Macbeth . You’re thinking about the different ways in which Shakespeare imagines and presents the witches, how they influence the action of the tragedy, and perhaps the extent to which we’re supposed to believe in them (stay with me – you don’t have to know a single thing about Shakespeare or Macbeth to understand this bit!). Now, you’ll probably have a few good ideas on this topic – and whatever essay you write, you’ll most likely use much of the same material. However, the detail of the phrasing of the question will significantly affect the way you write your essay. You would draw on similar material to address the following questions: Discuss Shakespeare’s representation of the three witches in Macbeth . How does Shakespeare figure the supernatural in Macbeth ? To what extent are the three witches responsible for Macbeth’s tragic downfall? Evaluate the importance of the three witches in bringing about Macbeth’s ruin. Are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? “Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, there is profound ambiguity about the actual significance and power of their malevolent intervention” (Stephen Greenblatt). Discuss. I’ve organised the examples into three groups, exemplifying the different types of questions you might have to answer in an exam. The first group are pretty open-ended: ‘discuss’- and ‘how’-questions leave you room to set the scope of the essay. You can decide what the focus should be. Beware, though – this doesn’t mean you don’t need a sturdy structure, or a clear argument, both of which should always be present in an essay. The second group are asking you to evaluate, constructing an argument that decides whether, and how far something is true. Good examples of hypotheses (which your essay would set out to prove) for these questions are:

- The witches are the most important cause of tragic action in Macbeth.

- The witches are partially, but not entirely responsible for Macbeth’s downfall, alongside Macbeth’s unbridled ambition, and that of his wife.

- We are not supposed to believe the witches: they are a product of Macbeth’s psyche, and his downfall is his own doing.

- The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is shaky – finally, their ambiguity is part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. (N.B. It’s fine to conclude that a question can’t be answered in black and white, certain terms – as long as you have a firm structure, and keep referring back to it throughout the essay).

The final question asks you to respond to a quotation. Students tend to find these sorts of questions the most difficult to answer, but once you’ve got the hang of them I think the title does most of the work for you – often implicitly providing you with a structure for your essay. The first step is breaking down the quotation into its constituent parts- the different things it says. I use brackets: ( Within Macbeth ’s representation of the witches, ) ( there is profound ambiguity ) about the ( actual significance ) ( and power ) of ( their malevolent intervention ) Examiners have a nasty habit of picking the most bewildering and terrifying-sounding quotations: but once you break them down, they’re often asking for something very simple. This quotation, for example, is asking exactly the same thing as the other questions. The trick here is making sure you respond to all the different parts. You want to make sure you discuss the following:

- Do you agree that the status of the witches’ ‘malevolent intervention’ is ambiguous?

- What is its significance?

- How powerful is it?

Step Two: Plan

Having worked out exactly what the question is asking, write out a plan (which should be very detailed in a coursework essay, but doesn’t have to be more than a few lines long in an exam context) of the material you’ll use in each paragraph. Make sure your plan contains a sentence at the end of each point about how that point will answer the question. A point from my plan for one of the topics above might look something like this:

To what extent are we supposed to believe in the three witches in Macbeth ? Hypothesis: The witches’ role in Macbeth’s downfall is deliberately unclear. Their claim to reality is uncertain – finally, they’re part of an uncertain tragic universe and the great illusion of the theatre. Para.1: Context At the time Shakespeare wrote Macbeth , there were many examples of people being burned or drowned as witches There were also people who claimed to be able to exorcise evil demons from people who were ‘possessed’. Catholic Christianity leaves much room for the supernatural to exist This suggests that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might, more readily than a modern one, have believed that witches were a real phenomenon and did exist.

My final sentence (highlighted in red) shows how the material discussed in the paragraph answers the question. Writing this out at the planning stage, in addition to clarifying your ideas, is a great test of whether a point is relevant: if you struggle to write the sentence, and make the connection to the question and larger argument, you might have gone off-topic.

Step Three: Paragraph beginnings and endings

The final step to making sure you pick up all the possible marks for ‘answering the question’ in an essay is ensuring that you make it explicit how your material does so. This bit relies upon getting the beginnings and endings of paragraphs just right. To reiterate what I said above, treat your reader like a child: tell them what you’re going to say; tell them how it answers the question; say it, and then tell them how you’ve answered the question. This need not feel clumsy, awkward or repetitive. The first sentence of each new paragraph or point should, without giving too much of your conclusion away, establish what you’re going to discuss, and how it answers the question. The opening sentence from the paragraph I planned above might go something like this:

Early modern political and religious contexts suggest that Shakespeare’s contemporary audience might more readily have believed in witches than his modern readers.

The sentence establishes that I’m going to discuss Jacobean religion and witch-burnings, and also what I’m going to use those contexts to show. I’d then slot in all my facts and examples in the middle of the paragraph. The final sentence (or few sentences) should be strong and decisive, making a clear connection to the question you’ve been asked:

Contemporary suspicion that witches did exist, testified to by witch-hunts and exorcisms, is crucial to our understanding of the witches in Macbeth. To the early modern consciousness, witches were a distinctly real and dangerous possibility – and the witches in the play would have seemed all-the-more potent and terrifying as a result.

Step Four: Practice makes perfect

The best way to get really good at making sure you always ‘answer the question’ is to write essay plans rather than whole pieces. Set aside a few hours, choose a couple of essay questions from past papers, and for each:

- Write a hypothesis

- Write a rough plan of what each paragraph will contain

- Write out the first and last sentence of each paragraph

You can get your teacher, or a friend, to look through your plans and give you feedback . If you follow this advice, fingers crossed, next time you hand in an essay, it’ll be free from red-inked comments about irrelevance, and instead showered with praise for the precision with which you handled the topic, and how intently you focused on answering the question. It can seem depressing when your perfect question is just a minor tangent from the question you were actually asked, but trust me – high praise and good marks are all found in answering the question in front of you, not the one you would have liked to see. Teachers do choose the questions they set you with some care, after all; chances are the question you were set is the more illuminating and rewarding one as well.

Image credits: banner ; Keats ; Macbeth ; James I ; witches .

Comments are closed.

Stay informed

Receive updates on teaching and learning initiatives and events.

- Resources for teaching

- Assessment design and security

- Tests and exams

Short answer and essay questions

Short answer and essay questions are types of assessment that are commonly used to evaluate a student’s understanding and knowledge.

Tips for creating short answer and essay questions

e.g., What is __? or how could __ be put into practice?

- Consider the course learning outcomes . Design questions that appropriately assess the relevant learning objectives.

- Make sure the content measures knowledge appropriate to the desired learner level and learning goal.

- When students think critically they are required to step beyond recalling factual information , incorporating evidence and examples to corroborate and/or dispute the validity of assertions/suppositions and compare and contrast multiple perspectives on the same argument.

e.g., paragraphs? sentences? Is bullet point format acceptable or does it have to be an essay format?

- Specify how many marks each question is worth .

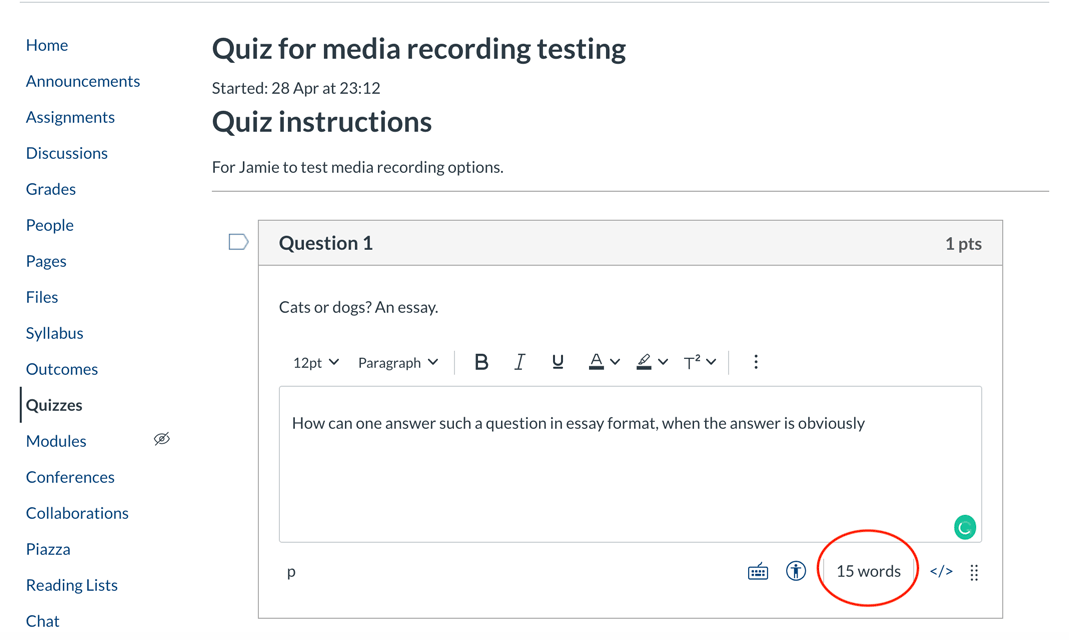

- Word limits should be applied within Canvas for discursive or essay-type responses.

- Check that your language and instructions are appropriate to the student population and discipline of study. Not all students have English as their first language.

- Ensure the instructions to students are clear , including optional and compulsory questions and the various components of the assessment.

Questions that promote deeper thinking

Use “open-ended” questions to provoke divergent thinking.

These questions will allow for a variety of possible answers and encourage students to think at a deeper level. Some generic question stems that trigger or stimulate different forms of critical thinking include:

- “What are the implications of …?”

- “Why is it important …?”

- “What is another way to look at …?”

Use questions that are deliberate in the types of higher order thinking to promote/assess

Rather than promoting recall of facts, use questions that allow students to demonstrate their comprehension, application and analysis of the concepts.

Generic question stems that can be used to trigger and assess higher order thinking

Comprehension.

Convert information into a form that makes sense to the individual .

- How would you put __ into your own words?

- What would be an example of __?

Application

Apply abstract or theoretical principles to concrete , practical situations.

- How can you make use of __?

- How could __ be put into practice?

Break down or dissect information.

- What are the most important/significant ideas or elements of __?

- What assumptions/biases underlie or are hidden within __?

Build up or connect separate pieces of information to form a larger, more coherent pattern

- How can these different ideas be grouped together into a more general category?

Critically judge the validity or aesthetic value of ideas, data, or products.

- How would you judge the accuracy or validity of __?

- How would you evaluate the ethical (moral) implications or consequences of __?

Draw conclusions about particular instances that are logically consistent.

- What specific conclusions can be drawn from this general __?

- What particular actions would be consistent with this general __?

Balanced thinking

Carefully consider arguments/evidence for and against a particular position.

- What evidence supports and contradicts __?

- What are arguments for and counterarguments against __?

Causal reasoning

Identify cause-effect relationships between different ideas or actions.

- How would you explain why __ occurred?

- How would __ affect or influence __?

Creative thinking

Generate imaginative ideas or novel approaches to traditional practices.

- What might be a metaphor or analogy for __?

- What might happen if __? (hypothetical reasoning)

Redesign test questions for open-book format

It is important to redesign the assessment tasks to authentically assess the intended learning outcomes in a way that is appropriate for this mode of assessment. Replacing questions that simply recall facts with questions that require higher level cognitive skills—for example analysis and explanation of why and how students reached an answer—provides opportunities for reflective questions based on students’ own experiences.

More quick, focused problem-solving and analysis—conducted with restricted access to limited allocated resources—will need to incorporate a student’s ability to demonstrate a more thoughtful research-based approach and/or the ability to negotiate an understanding of more complex problems, sometimes in an open-book format.

Layers can be added to the problem/process, and the inclusion of a reflective aspect can help achieve these goals, whether administered in an oral test or written examination format.

Example 2: Analytic style multiple choice question or short answer

Acknowledgement: Deakin University and original multiple choice questions: Jennifer Lindley, Monash University.

Setting word limits for discursive or essay-type responses

Try to set a fair and reasonable word count for long answer and essay questions. Some points to consider are:

- Weighting – what is the relative weighting of the question in the assessment?

- Level of study – what is the suggested word count for written assessments in your discipline, for that level of study?

- Skills development – what skills are you requiring students to demonstrate? Higher level cognitive skills, such as evaluation and analysis, tend to require a lengthier word count in order to adequately respond to the assessment prompt.

- Referencing – will you require students to reference their sources ? This takes time, which should be accounted for in the total time to complete the assessment. References generally would not count towards the word count. Include clear marking guidelines for referencing in rubrics, including assessing skills such as critical thinking and evaluation of information.

Communicate your expectations around word count to students in your assessment instructions, including how you will deal with submissions that are outside the word count.

E.g., Write 600-800 words evaluating the key concepts of XYZ. Excess text over the word limit will not be marked.

Let students know how to check the word count in their submission:

- Show word count in Inspera – question type: Essay.

Multi-choice questions

Write MCQs that assess reasoning, rather than recall.

Page updated 16/03/2023 (added open-book section)

What do you think about this page? Is there something missing? For enquiries unrelated to this content, please visit the Staff Service Centre

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Essay Exams

What this handout is about.

At some time in your undergraduate career, you’re going to have to write an essay exam. This thought can inspire a fair amount of fear: we struggle enough with essays when they aren’t timed events based on unknown questions. The goal of this handout is to give you some easy and effective strategies that will help you take control of the situation and do your best.

Why do instructors give essay exams?

Essay exams are a useful tool for finding out if you can sort through a large body of information, figure out what is important, and explain why it is important. Essay exams challenge you to come up with key course ideas and put them in your own words and to use the interpretive or analytical skills you’ve practiced in the course. Instructors want to see whether:

- You understand concepts that provide the basis for the course

- You can use those concepts to interpret specific materials

- You can make connections, see relationships, draw comparisons and contrasts

- You can synthesize diverse information in support of an original assertion

- You can justify your own evaluations based on appropriate criteria

- You can argue your own opinions with convincing evidence

- You can think critically and analytically about a subject

What essay questions require

Exam questions can reach pretty far into the course materials, so you cannot hope to do well on them if you do not keep up with the readings and assignments from the beginning of the course. The most successful essay exam takers are prepared for anything reasonable, and they probably have some intelligent guesses about the content of the exam before they take it. How can you be a prepared exam taker? Try some of the following suggestions during the semester:

- Do the reading as the syllabus dictates; keeping up with the reading while the related concepts are being discussed in class saves you double the effort later.

- Go to lectures (and put away your phone, the newspaper, and that crossword puzzle!).

- Take careful notes that you’ll understand months later. If this is not your strong suit or the conventions for a particular discipline are different from what you are used to, ask your TA or the Learning Center for advice.

- Participate in your discussion sections; this will help you absorb the material better so you don’t have to study as hard.

- Organize small study groups with classmates to explore and review course materials throughout the semester. Others will catch things you might miss even when paying attention. This is not cheating. As long as what you write on the essay is your own work, formulating ideas and sharing notes is okay. In fact, it is a big part of the learning process.

- As an exam approaches, find out what you can about the form it will take. This will help you forecast the questions that will be on the exam, and prepare for them.

These suggestions will save you lots of time and misery later. Remember that you can’t cram weeks of information into a single day or night of study. So why put yourself in that position?

Now let’s focus on studying for the exam. You’ll notice the following suggestions are all based on organizing your study materials into manageable chunks of related material. If you have a plan of attack, you’ll feel more confident and your answers will be more clear. Here are some tips:

- Don’t just memorize aimlessly; clarify the important issues of the course and use these issues to focus your understanding of specific facts and particular readings.

- Try to organize and prioritize the information into a thematic pattern. Look at what you’ve studied and find a way to put things into related groups. Find the fundamental ideas that have been emphasized throughout the course and organize your notes into broad categories. Think about how different categories relate to each other.

- Find out what you don’t know, but need to know, by making up test questions and trying to answer them. Studying in groups helps as well.

Taking the exam

Read the exam carefully.

- If you are given the entire exam at once and can determine your approach on your own, read the entire exam before you get started.

- Look at how many points each part earns you, and find hints for how long your answers should be.

- Figure out how much time you have and how best to use it. Write down the actual clock time that you expect to take in each section, and stick to it. This will help you avoid spending all your time on only one section. One strategy is to divide the available time according to percentage worth of the question. You don’t want to spend half of your time on something that is only worth one tenth of the total points.

- As you read, make tentative choices of the questions you will answer (if you have a choice). Don’t just answer the first essay question you encounter. Instead, read through all of the options. Jot down really brief ideas for each question before deciding.

- Remember that the easiest-looking question is not always as easy as it looks. Focus your attention on questions for which you can explain your answer most thoroughly, rather than settle on questions where you know the answer but can’t say why.

Analyze the questions

- Decide what you are being asked to do. If you skim the question to find the main “topic” and then rush to grasp any related ideas you can recall, you may become flustered, lose concentration, and even go blank. Try looking closely at what the question is directing you to do, and try to understand the sort of writing that will be required.

- Focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

- Look at the active verbs in the assignment—they tell you what you should be doing. We’ve included some of these below, with some suggestions on what they might mean. (For help with this sort of detective work, see the Writing Center handout titled Reading Assignments.)

Information words, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject. Information words may include:

- define—give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning.

- explain why/how—give reasons why or examples of how something happened.

- illustrate—give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject.

- summarize—briefly cover the important ideas you learned about the subject.

- trace—outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form.

- research—gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you’ve found.

Relation words ask you to demonstrate how things are connected. Relation words may include:

- compare—show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different).

- contrast—show how two or more things are dissimilar.

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation.

- cause—show how one event or series of events made something else happen.

- relate—show or describe the connections between things.

Interpretation words ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Don’t see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation. Interpretation words may include:

- prove, justify—give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth.

- evaluate, respond, assess—state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons (you may want to compare your subject to something else).

- support—give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe).

- synthesize—put two or more things together that haven’t been put together before; don’t just summarize one and then the other, and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together (as opposed to compare and contrast—see above).

- analyze—look closely at the components of something to figure out how it works, what it might mean, or why it is important.

- argue—take a side and defend it (with proof) against the other side.

Plan your answers

Think about your time again. How much planning time you should take depends on how much time you have for each question and how many points each question is worth. Here are some general guidelines:

- For short-answer definitions and identifications, just take a few seconds. Skip over any you don’t recognize fairly quickly, and come back to them when another question jogs your memory.

- For answers that require a paragraph or two, jot down several important ideas or specific examples that help to focus your thoughts.

- For longer answers, you will need to develop a much more definite strategy of organization. You only have time for one draft, so allow a reasonable amount of time—as much as a quarter of the time you’ve allotted for the question—for making notes, determining a thesis, and developing an outline.

- For questions with several parts (different requests or directions, a sequence of questions), make a list of the parts so that you do not miss or minimize one part. One way to be sure you answer them all is to number them in the question and in your outline.

- You may have to try two or three outlines or clusters before you hit on a workable plan. But be realistic—you want a plan you can develop within the limited time allotted for your answer. Your outline will have to be selective—not everything you know, but what you know that you can state clearly and keep to the point in the time available.

Again, focus on what you do know about the question, not on what you don’t.

Writing your answers

As with planning, your strategy for writing depends on the length of your answer:

- For short identifications and definitions, it is usually best to start with a general identifying statement and then move on to describe specific applications or explanations. Two sentences will almost always suffice, but make sure they are complete sentences. Find out whether the instructor wants definition alone, or definition and significance. Why is the identification term or object important?

- For longer answers, begin by stating your forecasting statement or thesis clearly and explicitly. Strive for focus, simplicity, and clarity. In stating your point and developing your answers, you may want to use important course vocabulary words from the question. For example, if the question is, “How does wisteria function as a representation of memory in Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom?” you may want to use the words wisteria, representation, memory, and Faulkner) in your thesis statement and answer. Use these important words or concepts throughout the answer.

- If you have devised a promising outline for your answer, then you will be able to forecast your overall plan and its subpoints in your opening sentence. Forecasting impresses readers and has the very practical advantage of making your answer easier to read. Also, if you don’t finish writing, it tells your reader what you would have said if you had finished (and may get you partial points).

- You might want to use briefer paragraphs than you ordinarily do and signal clear relations between paragraphs with transition phrases or sentences.

- As you move ahead with the writing, you may think of new subpoints or ideas to include in the essay. Stop briefly to make a note of these on your original outline. If they are most appropriately inserted in a section you’ve already written, write them neatly in the margin, at the top of the page, or on the last page, with arrows or marks to alert the reader to where they fit in your answer. Be as neat and clear as possible.

- Don’t pad your answer with irrelevancies and repetitions just to fill up space. Within the time available, write a comprehensive, specific answer.

- Watch the clock carefully to ensure that you do not spend too much time on one answer. You must be realistic about the time constraints of an essay exam. If you write one dazzling answer on an exam with three equally-weighted required questions, you earn only 33 points—not enough to pass at most colleges. This may seem unfair, but keep in mind that instructors plan exams to be reasonably comprehensive. They want you to write about the course materials in two or three or more ways, not just one way. Hint: if you finish a half-hour essay in 10 minutes, you may need to develop some of your ideas more fully.

- If you run out of time when you are writing an answer, jot down the remaining main ideas from your outline, just to show that you know the material and with more time could have continued your exposition.

- Double-space to leave room for additions, and strike through errors or changes with one straight line (avoid erasing or scribbling over). Keep things as clean as possible. You never know what will earn you partial credit.

- Write legibly and proofread. Remember that your instructor will likely be reading a large pile of exams. The more difficult they are to read, the more exasperated the instructor might become. Your instructor also cannot give you credit for what they cannot understand. A few minutes of careful proofreading can improve your grade.

Perhaps the most important thing to keep in mind in writing essay exams is that you have a limited amount of time and space in which to get across the knowledge you have acquired and your ability to use it. Essay exams are not the place to be subtle or vague. It’s okay to have an obvious structure, even the five-paragraph essay format you may have been taught in high school. Introduce your main idea, have several paragraphs of support—each with a single point defended by specific examples, and conclude with a restatement of your main point and its significance.

Some physiological tips

Just think—we expect athletes to practice constantly and use everything in their abilities and situations in order to achieve success. Yet, somehow many students are convinced that one day’s worth of studying, no sleep, and some well-placed compliments (“Gee, Dr. So-and-so, I really enjoyed your last lecture”) are good preparation for a test. Essay exams are like any other testing situation in life: you’ll do best if you are prepared for what is expected of you, have practiced doing it before, and have arrived in the best shape to do it. You may not want to believe this, but it’s true: a good night’s sleep and a relaxed mind and body can do as much or more for you as any last-minute cram session. Colleges abound with tales of woe about students who slept through exams because they stayed up all night, wrote an essay on the wrong topic, forgot everything they studied, or freaked out in the exam and hyperventilated. If you are rested, breathing normally, and have brought along some healthy, energy-boosting snacks that you can eat or drink quietly, you are in a much better position to do a good job on the test. You aren’t going to write a good essay on something you figured out at 4 a.m. that morning. If you prepare yourself well throughout the semester, you don’t risk your whole grade on an overloaded, undernourished brain.

If for some reason you get yourself into this situation, take a minute every once in a while during the test to breathe deeply, stretch, and clear your brain. You need to be especially aware of the likelihood of errors, so check your essays thoroughly before you hand them in to make sure they answer the right questions and don’t have big oversights or mistakes (like saying “Hitler” when you really mean “Churchill”).

If you tend to go blank during exams, try studying in the same classroom in which the test will be given. Some research suggests that people attach ideas to their surroundings, so it might jog your memory to see the same things you were looking at while you studied.

Try good luck charms. Bring in something you associate with success or the support of your loved ones, and use it as a psychological boost.

Take all of the time you’ve been allotted. Reread, rework, and rethink your answers if you have extra time at the end, rather than giving up and handing the exam in the minute you’ve written your last sentence. Use every advantage you are given.

Remember that instructors do not want to see you trip up—they want to see you do well. With this in mind, try to relax and just do the best you can. The more you panic, the more mistakes you are liable to make. Put the test in perspective: will you die from a poor performance? Will you lose all of your friends? Will your entire future be destroyed? Remember: it’s just a test.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Axelrod, Rise B., and Charles R. Cooper. 2016. The St. Martin’s Guide to Writing , 11th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Fowler, Ramsay H., and Jane E. Aaron. 2016. The Little, Brown Handbook , 13th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Gefvert, Constance J. 1988. The Confident Writer: A Norton Handbook , 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton and Company.

Kirszner, Laurie G. 1988. Writing: A College Rhetoric , 2nd ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Lunsford, Andrea A. 2015. The St. Martin’s Handbook , 8th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Woodman, Leonara, and Thomas P. Adler. 1988. The Writer’s Choices , 2nd ed. Northbrook, Illinois: Scott Foresman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Calendar/Events

- Navigate: Students

- One-Stop Resources

- Navigate: Staff

- My Wisconsin Portal

- More Resources

- LEARN Center

- Research-Based Teaching Tips

Short Answer & Essay Tests

Strategies, Ideas, and Recommendations from the faculty Development Literature

General Strategies

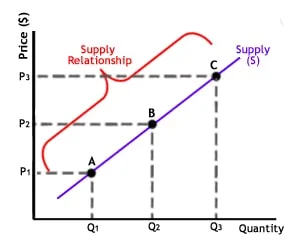

Save essay questions for testing higher levels of thought (application, synthesis, and evaluation), not recall facts. Appropriate tasks for essays include: Comparing: Identify the similarities and differences between Relating cause and effect: What are the major causes of...? What would be the most likely effects of...? Justifying: Explain why you agree or disagree with the following statement. Generalizing: State a set of principles that can explain the following events. Inferring: How would character X react to the following? Creating: what would happen if...? Applying: Describe a situation that illustrates the principle of. Analyzing: Find and correct the reasoning errors in the following passage. Evaluating: Assess the strengths and weaknesses of.

There are three drawbacks to giving students a choice. First, some students will waste time trying to decide which questions to answer. Second, you will not know whether all students are equally knowledgeable about all the topics covered on the test. Third, since some questions are likely to be harder than others, the test could be unfair.

Tests that ask only one question are less valid and reliable than those with a wider sampling of test items. In a fifty-minute class period, you may be able to pose three essay questions or ten short answer questions.

To reduce students' anxiety and help them see that you want them to do their best, give them pointers on how to take an essay exam. For example:

- Survey the entire test quickly, noting the directions and estimating the importance and difficulty of each question. If ideas or answers come to mind, jot them down quickly.

- Outline each answer before you begin to write. Jot down notes on important points, arrange them in a pattern, and add specific details under each point.

Writing Effective Test Questions

Avoid vague questions that could lead students to different interpretations. If you use the word "how" or "why" in an essay question, students will be better able to develop a clear thesis. As examples of essay and short-answer questions: Poor: What are three types of market organization? In what ways are they different from one another? Better: Define oligopoly. How does oligopoly differ from both perfect competition and monopoly in terms of number of firms, control over price, conditions of entry, cost structure, and long-term profitability? Poor: Name the principles that determined postwar American foreign policy. Better: Describe three principles on which American foreign policy was based between 1945 and 1960; illustrate each of the principles with two actions of the executive branch of government.

If you want students to consider certain aspects or issues in developing their answers, set them out in separate paragraph. Leave the questions on a line by itself.

Use your version to help you revise the question, as needed, and to estimate how much time students will need to complete the question. If you can answer the question in ten minutes, students will probably need twenty to thirty minutes. Use these estimates in determining the number of questions to ask on the exam. Give students advice on how much time to spend on each question.

Decide which specific facts or ideas a student must mention to earn full credit and how you will award partial credit. Below is an example of a holistic scoring rubric used to evaluate essays:

- Full credit-six points: The essay clearly states a position, provides support for the position, and raises a counterargument or objection and refutes it.

- Five points: The essay states a position, supports it, and raises a counterargument or objection and refutes it. The essay contains one or more of the following ragged edges: evidence is not uniformly persuasive, counterargument is not a serious threat to the position, some ideas seem out of place.

- Four points: The essay states a position and raises a counterargument, but neither is well developed. The objection or counterargument may lean toward the trivial. The essay also seems disorganized.

- Three points: The essay states a position, provides evidence supporting the position, and is well organized. However, the essay does not address possible objections or counterarguments. Thus, even though the essay may be better organized than the essay given four points, it should not receive more than three points.

- Two points: The essay states a position and provides some support but does not do it very well. Evidence is scanty, trivial, or general. The essay achieves it length largely through repetition of ideas and inclusion of irrelevant information.

- One point: The essay does not state the student's position on the issue. Instead, it restates the position presented in the question and summarizes evidence discussed in class or in the reading.

Try not to bias your grading by carrying over your perceptions about individual students. Some faculty ask students to put a number or pseudonym on the exam and to place that number / pseudonym on an index card that is turned in with the test, or have students write their names on the last page of the blue book or on the back of the test.

Before you begin grading, you will want an overview of the general level of performance and the range of students' responses.

Identify exams that are excellent, good, adequate, and poor. Use these papers to refresh your memory of the standards by which you are grading and to ensure fairness over the period of time you spend grading.

Shuffle papers before scoring the next question to distribute your fatigue factor randomly. By randomly shuffling papers you also avoid ordering effects.

Don't let handwriting, use of pen or pencil, format (for example, many lists), or other such factors influence your judgment about the intellectual quality of the response.

Write brief notes on strengths and weaknesses to indicate what students have done well and where they need to improve. The process of writing comments also keeps your attention focused on the response. And your comments will refresh your memory if a student wants to talk to you about the exam.

Focus on the organization and flow of the response, not on whether you agree or disagree with the students' ideas. Experiences faculty note, however, that students tend not to read their returned final exams, so you probably do not need to comment extensively on those.

Most faculty tire after reading ten or so responses. Take short breaks to keep up your concentration. Also, try to set limits on how long to spend on each paper so that you maintain you energy level and do not get overwhelmed. However, research suggests that you read all responses to a single question in one sitting to avoid extraneous factors influencing your grading (for example, time of day, temperature, and so on).

Wait two days or so and review a random set of exams without looking at the grades you assigned. Rereading helps you increase your reliability as a grader. If your two score differ, take the average.

This protects students' privacy when you return or they pick up their tests. Returning Essay Exams

A quick turnaround reinforces learning and capitalizes on students' interest in the results. Try to return tests within a week or so.

Give students a copy of the scoring guide or grading criteria you used. Let students know what a good answer included and the most common errors the class made. If you wish, read an example of a good answer and contrast it with a poor answer you created. Give students information on the distribution of scores so they know where they stand.

Some faculty break the class into small groups to discuss answers to the test. Unresolved questions are brought up to the class as a whole.

Ask students to tell you what was particularly difficult or unexpected. Find out how they prepared for the exam and what they wish they had done differently. Pass along to next year's class tips on the specific skills and strategies this class found effective.

Include a copy of the test with your annotations on ways to improve it, the mistakes students made in responding to various question, the distribution of students' performance, and comments that students made about the exam. If possible, keep copies of good and poor exams.

The Strategies, Ideas and Recommendations Here Come Primarily From:

Gross Davis, B. Tools for Teaching. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1993.

McKeachie, W. J. Teaching Tips. (10th ed.) Lexington, Mass.: Heath, 2002.

Walvoord, B. E. and Johnson Anderson, V. Effective Grading. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass, 1998.

And These Additional Sources... Brooks, P. Working in Subject A Courses. Berkeley: Subject A Program, University of California, 1990.

Cashin, W. E. "Improving Essay Tests." Idea Paper, no. 17. Manhattan: Center for Faculty

Evaluation and Development in Higher Education, Kansas State University, 1987.

Erickson, B. L., and Strommer, D. W. Teaching College Freshmen. San Francisco:

Jossey-Bass, 1991.

Fuhrmann, B. S. and Grasha, A. F. A Practical Handbook for College Teachers. Boston:

Little, Brown, 1983.

Jacobs, L. C. and Chase, C. I. Developing and Using Tests Effectively: A Guide for Faculty.

San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1992.

Jedrey, C. M. "Grading and Evaluation." In M. M. gullette (ed.), The Art and Craft of Teaching.

Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1984.

Lowman, J. Mastering the Techniques of Teaching. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1984.

Ory, J. C. Improving Your Test Questions. Urbana:

Office of Instructional Res., University of Illinois, 1985.

Tollefson, S. K. Encouraging Student Writing. Berkeley:

Office of Educational Development, University of California, 1988.

Unruh, D. Test Scoring manual: Guide for Developing and Scoring Course Examinations.

Los Angeles: Office of Instructional Development, University of California, 1988.

Walvoord, B. E. Helping Students Write Well: A Guide for Teachers in All Disciplines.

(2nded.) New York: Modern Language Association, 1986.

We use cookies on this site. By continuing to browse without changing your browser settings to block or delete cookies you agree to the UW-Whitewater Privacy Notice .

- A-Z Directory

- Campus Maps

- Faculties and Schools

- International

- People and Departments

- Become A Student

- Give to Memorial

- Faculty & Staff

- Online Learning

- Self Service

- Other MUN Login Services

- Academic Success Centre

- Learning skills resources

Exam Strategies: Short Answer & Essay Exams

Essay exams involve a significant written component in which you are asked to discuss and expand on a topic. These could include written responses in the form of a formal essay or a detailed short-answer response.

- Short answer vs essay questions

Preparing for an essay exam

Answering essay questions.

Check out our visual resources for " Test Taking Strategies: Short Answer & Essay Questions " below!

What is the difference between a short answer and an essay question?

- Both short-answer and essay questions ask you to demonstrate your knowledge of course material by relating your answer to concepts covered in the course.

- Essay questions require a thesis (argument) and supporting evidence (from course material - lectures, readings, discussions, and assignments) outlined in several paragraphs, including an introduction, body, and conclusion.

- Short-answer questions are more concise than essay answers - think of it as a “mini-essay” - and use a sentence or two to introduce your topic; select a few points to discuss; add a concluding sentence that sums up your response.

- Review your course material - look for themes within the topics covered, use these to prepare sample questions if your instructor has not given direction on what to expect from essay questions.

- Create outlines to answer your practice questions. Choose a definite argument or thesis statement and organize supporting evidence logically in body paragraphs. Try a mnemonic (like a rhyme or acronym) to help remember your outline.

- Practice! Using your outline, try using a timer to write a full response to your practice or sample questions within the exam time limit.

- Review the question carefully. Think about what it is asking - what are you expected to include? What material or examples are relevant?

- Underline keywords in the question to identify the main topic and discussion areas.

- Plan your time. Keep an eye on the time allowed and how many essay questions you are required to answer. Consider the mark distribution to determine how much time to spend on each question or section.

- Make a plan. Take a few minutes to brainstorm and plan your response - jot down a brief outline to order your points and arguments before you start to write.

- Include a thesis statement in your introduction so that your argument is clear, even if you run out of time, and help structure your answer.

- Write a conclusion , even if brief - use this to bring your ideas together to answer the question and suggest the broader implications.

- Clearly and concisely answer the question :

- In your introduction, show that you understand the question and outline how you will answer it.

- Make one point or argument per paragraph and include one or two pieces of evidence or examples for each point.

- In your conclusion, summarize the arguments to answer the question.

"Test Taking Strategies: Short Answer & Essay Questions"

Does your next test have short answer or essay questions? Let's look at how to prepare for these type of questions, how to answer these types of questions, and strategies to keep in mind during the exam. Fight exam writer's block and achieve your best marks yet!

- "Test Taking Strategies: Short Answer & Essay Questions" PDF

- "Test Taking Strategies: Short Answer & Essay Questions" Video

Looking for more strategies and tips? Check out MUN's Academic Success Centre online!

Carnegie Mellon University. (n.d.). Successful exam strategies. Carnegie Mellon University: Student Academic Success. Retrieved April 1, 2022 from https://www.cmu.edu/student-success/other-resources/fast-facts/exam-strategies.pdf

Memorial University of Newfoundland. (n.d.). Exam strategies: Short answer & essay exams. Memorial University of Newfoundland: Academic Success Centre. Retrieved April 1, 2022 from https://www.mun.ca/munup/vssc/learning/exam-strategies-essays.php

Trent University. (n.d.). How to understand and answer free response or essay exam questions. Trent University: Academic Skills. Retrieved April 1, 2022 from https://www.trentu.ca/academicskills/how-guides/how-study/prepare-and-write-exams/how-understand-and-answer-free-response-or-essay-exam

University of Queensland Australia. (n.d.). Exam tips. University of Queensland Australia: Student support, study skills. Retrieved April 1, 2022 from https://my.uq.edu.au/information-and-services/student-support/study-skills/exam-tips

University of Waterloo. (n.d.). Exam questions: Types, characteristics, and suggestions. University of Waterloo: Centre for Teaching Excellence. Retrieved April 1, 2022 from https://uwaterloo.ca/centre-for-teaching-excellence/teaching-resources/teaching-tips/developing-assignments/exams/questions-types-characteristics-suggestions

- Learning supports

- Peer-Assisted Learning

- Help centres

- Study spaces

- Graduate student supports

- Events and workshops

- Faculty & staff resources

Related Content

Personal Essay and Short Answer Prompts

Personal essay prompts.

To help us get to know you in the application review process, you are required to submit a personal essay. For insight and advice about how to approach writing your personal essay, see our Expert Advice page.

- Common Application first-year essay prompts

- Common App transfer essay prompt: Please provide a personal essay that addresses your reasons for transferring and the objectives you hope to achieve.

- Coalition, powered by Scoir first-year and transfer essay prompts

Short Answer Question

For both first-year and transfer applicants, we ask you to complete a short answer essay (approximately 250 words) based on one of two prompts.

- Vanderbilt University values learning through contrasting points of view. We understand that our differences, and our respect for alternative views and voices, are our greatest source of strength. Please reflect on conversations you’ve had with people who have expressed viewpoints different from your own. How did these conversations/experiences influence you?

- Vanderbilt offers a community where students find balance between their academic and social experiences. Please briefly elaborate on how one of your extracurricular activities or work experiences has influenced you.

- School Search

- Guided Tour

Writing samples are an important part of your application to any college. Your responses show how well you would fit with an institution; your ability to write clearly, concisely, and develop an argument; and your ability to do the work required of you should you be accepted. Use both short answer questions and personal essays to highlight your personality and what makes you unique while also showing off your academic talents.

Short Answer Questions

Short answer questions are almost harder to write than a personal essay, since you usually have a word limit. Often, this may be as short as 150 words (a paragraph). This means that your answers must be clear and concise without being so bare bones that you don’t seem to have a personality. In fact, it’s okay if you answer the question in less than the allotted space. Provided you avoid clichés and sarcasm and answer the question wholly, less can be more. Here are some tips to help you ace your short answers:

- Don’t repeat the question.

- Don’t use unnecessarily large words. Not only will you come off as pretentious at best and ignorant at worst, but it’s unlikely that you’ll be able to keep the same tone throughout your response. After all, wouldn’t it be easier for you to read a paragraph that addresses “how to write concisely” rather than one about “how to circumvent the superfluous use of language?” Craft your response so that your reader can easily understand your point without resorting to a thesaurus.

- Answer honestly. If you are asked to discuss one of your favorite things, don’t feel ashamed to tell the truth. Colleges want to get to know you. A “cool” answer isn’t as interesting as your honest, unique one.

- Supplement your résumé. Talk about things that aren’t mentioned anywhere else in your application to show off a different side of your personality.

- Always use details to bring even a short story to life.

- Don’t be afraid of the word limit. Write out your answer without worrying about the length and then go back and delete any unnecessary information. Underline the stand-out points and trim the rest.

- Describe your personal growth. When discussing an activity or event in your life, ask yourself what you learned or took away from it. Colleges like to understand how you’ve been changed by your experiences and see that you possess self-awareness.

- Be specific about each institution. If asked why you want to attend a particular school, make sure to reference any times you visited the campus, met with admissions counselors, or spoke with current students or alumni. Talk about programs that interest you and how you think they will benefit you in the future. Tell your readers why the idea of being a student at their institution excites you. College admissions officers can spot generic answers, so do your research if you don’t know a lot about the school. Talk about each school as if it is your top choice, even if it’s not. Under no circumstances should you say that a particular school is your “safety.”

The Personal Essay

The majority of colleges will ask you to submit at least one personal essay as part of your application. (You can find the 2019–2020 application platform personal essay prompts here , but not all schools use an application platform. In such cases, you will find essay prompts on the school’s own application.) By reading your submission, college admissions officers become familiar with your personality and writing proficiency. Your essay, along with your other application materials, helps them determine if you would be a good fit for the school and if you would be able to keep up with the rigor of the course load. A well-written, insightful essay can set you apart from other applicants with identical grades and test scores. Likewise, a poorly constructed essay can be detrimental to your application.

To ensure that your essay is the best it can be, you will need to spend some time reviewing the essay prompt to understand the question. Not only will you need time to become familiar with the directions, but you will also want to take your time when constructing your essay. No one can sit down and write the perfect essay in one shot. These things take effort, brainpower, and a significant amount of patience. Consider these steps for producing a well-written, thoughtful response to any essay prompt:

- Get moving. The best way to activate your mind is to activate your body. The act of moving forward, whether you are on foot or on a bike, can help you work through the ideas that might feel stuck. Read the prompt thoroughly, and then see what comes to you as your move through your neighborhood.

- Write down your ideas . When you get home, write down the ideas that stood out. Simply put the pen to paper or your hands to the keys and write without worrying about sentence structure or grammar. There’s plenty of time to edit later on.

- Rule out ideas that won’t work. Use the resources in the section below to decide if you are being asked to write a personal, school, or creative/intellectual statement and read through the the corresponding tips. If any of your ideas don’t fall within our guidelines, find a different approach to answering the question or rule out the topic altogether.

- Construct an outline (or two). At most, you will be able to use 650 words to respond to the question, so every statement you make must serve your overall objective. To stay on topic and build your story or argument, it’s helpful to have a map to guide you. Choose a topic or two from you list and give yourself plenty of time to outline each idea. Use bullet points and separate each section by paragraph. You may realize that one topic is too broad and you need to narrow your focus. If you make two outlines, ask a trusted adult to help you decide which one is stronger than the other. Even if you're not a fan of outlines and prefer to write organically, writing down your ideas in a consecutive list and creating a pseudo-outline can still help you maintain organization and flow between ideas when you actually fill in the blanks.

- Fill in the details with positivity. You are now ready to begin your first draft of your essay. Staying positive in your writing, even if you choose to tackle a hard subject, will endear you to admissions officers while negativity, self-pity, and resentment aren’t going to make your case. Use vivid descriptions when telling your story, but don’t stray too far from your main topic as to become dishonest or exaggerated. Admissions officers are well versed in picking out the real from the fake and aren’t going to be impressed by a made-up story.

- Walk away. When you’ve finished your first draft, walk away for a while, even a day or two, and clear your mind. You’ll be able to look at it with fresh eyes later and make edits to strengthen your argument or main idea.

- Ask for the appropriate amount of help. While it is okay to have a parent or teacher read over your essay to make sure that the points you want to make are coming through or to offer minor suggestions, it is under no circumstances acceptable to allow anyone else to make significant changes, alter the voice or message, or write the essay for you. A dishonest application will be noticed and dismissed by admissions officers.

- Edit. For the initial proofreading, read your essay out loud or backwards, sentence by sentence. Reading it in a form that you haven’t gotten used to will make it easier for you to spot grammatical and spelling errors. Then, ask for one family member or friend to read the essay out loud to you. Together, you can listen for things you missed with your eyes.

The Three Types of Essay Questions

There are three types of personal essays: the personal statement, the school statement, and the creative or intellectual statement. These are described below.

The Personal Statement

- Goal: The personal statement should be a window into your inner life. It is a chance to show schools who you are beyond your grades, test scores, and extracurricular activities. An honest, thoughtful reflection will help admissions officers understand your passions, goals, and relationships with family, friends, and other communities.

- Example: “Some students have a background, identity, interest, or talent that is so meaningful they believe their application would be incomplete without it. If this sounds like you, then please share your story.” – Common Application, 2015

- Don’t attempt to sum up your life in one statement. Instead, try to pick one significant experience to elaborate on. Use details to paint a picture for the reader. Talk about how you were affected and what changed about your perception of the world. How did the experience bring you to where you are today?

- Don’t reiterate your résumé. Let your résumé, transcripts, and test scores tell one story about you. Use your essay to tell a different one. Think of it not as a place to impress, but as a place to reflect.

- Don’t talk about an experience that isn’t unique. While almost anyone could say that they struggled with history in high school, few could describe the influence that their great-grandfather had on their understanding of U.S. history in the context of World War II. Picking an experience or topic that will set you apart from other applicants is key to catching the eye of the admissions team.

- Don’t write to impress. Schools don’t want you to write about what you think they want to hear. It’s easy for them to tell when you aren’t being genuine. Pick a topic that’s significant and meaningful to you even if it’s not “impressive.” Having personal awareness is impressive on its own.

The School Statement

- Goal: With your school statement, it should be clear that you have done your research on the school to which you are applying. Admissions counselors use the essay to assess your enthusiasm for the school and your commitment to discovering how the education will benefit you in the future. You want them to understand what you are drawn to so they can begin to envision you as a student on campus.

- Example: “Which aspects of Tufts’ curriculum or undergraduate experience prompted your application? In short: Why Tufts?” – Tufts University, 2015

- Don’t make general statements. It’s important to cite specifics instead of referencing the obvious. If a school is highly ranked and is known for its strong liberal arts curriculum, that’s dandy, but it’s common knowledge. Instead, talk about the teachers, programs, school traditions, clubs, and activities that put the school at the top of your list. If possible, reference any times you visited the campus, met with admissions counselors, or spoke with current students or alumni. Show them that you cared to do more than just a simple Google search.

- Don’t use the same essay for every school. It may be tempting to reuse the same essay for every school, but your essay should not be so general that you can sub out each school’s name as if it were a fill-in-the-blank answer. Sure, you may be able to recycle some content that applies to multiple schools on your list, but be sure to round off each essay with tangible information about the institution (references to buildings on campus, your interview, the mascot, an exciting lecture series, etc.). This proves that you aren’t applying to the school on a whim.

- Don’t overlook the facts. Verifying your statements about a school is essential. If you say that you are excited to become a theater major but the college did away with the program five years ago, admissions counselors may not take you seriously. Do yourself a favor and fact-check.

The Creative/Intellectual Statement