The evolution of global poverty, 1990-2030

Download the full working paper

Subscribe to the Sustainable Development Bulletin

Homi kharas and homi kharas senior fellow - global economy and development , center for sustainable development meagan dooley meagan dooley former senior research analyst - global economy and development , center for sustainable development.

February 2, 2022

The last 30 years have seen dramatic reductions in global poverty, spurred by strong catch-up growth in developing countries, especially in Asia. By 2015, some 729 million people, 10% of the population, lived under the $1.90 a day poverty line, greatly exceeding the Millennium Development Goal target of halving poverty. From 2012 to 2013, at the peak of global poverty reduction, the global poverty headcount fell by 130 million poor people.

This success story was dominated by China and India. In December 2020, China declared it had eliminated extreme poverty completely . India represents a more recent success story. Strong economic growth drove poverty rates down to 77 million, or 6% of the population, in 2019. India will, however, experience a short-term spike in poverty due to COVID-19, before resuming a strong downward path. By 2030, India is likely to essentially eliminate extreme poverty, with less than 5 million people living below the $1.90 line. By 2030, the only Asian countries that are unlikely to meet the goal of ending extreme poverty are Afghanistan, Papua New Guinea, and North Korea.

In other parts of the world, poverty trends are disappointing. In Latin America, poverty fell rapidly at the beginning of this century but has been rising since 2015, with no substantial reductions forecast by the end of this decade. In Africa, poverty has been rising steadily, thanks to rapid population growth and stagnant economic growth. Exacerbated by a pandemic-induced rise in poverty of 11%, African poverty shows little signs of decline through 2030.

Related Content

Homi Kharas, Kristofer Hamel, Martin Hofer

December 13, 2018

Homi Kharas, Kristofer Hamel, Martin Hofer, Baldwin Tong

May 23, 2019

Jasmin Baier, Kristofer Hamel

October 17, 2018

These trends point to the emergence of a very different poverty landscape. Whereas in 1990, poverty was concentrated in low-income, Asian countries, today’s (and tomorrow’s) poverty is largely found in sub-Saharan Africa and fragile and conflict-affected states. By 2030, sub-Saharan African countries will account for 9 of the top 10 countries by poverty headcount. Sixty percent of the global poor will live in fragile and conflict-affected states. Many of the top poverty destinations in the next decade will fall into both of these categories: Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Mozambique and Somalia. Global efforts to achieve the SDGs by 2030, including eliminating extreme poverty, will be complicated by the concentration of poverty in these fragile and hard-to-reach contexts.

By 2030, poverty will be associated not just with countries, but with specific places within countries. Middle-income countries will be home to almost half of the global poor, a dramatic shift from just 40 years earlier. Nigeria is now the global face of poverty, overtaking India as the top poverty destination in 2019. (While India temporarily regained its title due to COVID-19, which pushed many vulnerable Indians back below the poverty line, Nigeria will reclaim the top spot by 2022.) In 2015, Nigeria was home to 80 million poor people, or 11% of global poverty; by 2030, this number could grow to 18%, or 107 million.

Poverty numbers and trends have traditionally been reported on a country-by-country basis. However, today we see that low-income countries have significant corridors of prosperity, while middle-income countries can have large pockets of poverty. With advances in geospatial and sub-national data , there is a growing push to move from country-wide metrics to sub-national data, in order to better identify and target these poverty “hotspots.”

Global Economy and Development

Center for Sustainable Development

John W. McArthur, Fred Dews

September 13, 2024

George Ingram

September 12, 2024

Zuzana Brixiova Schwidrowski, Zoubir Benhanmouche

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Rural Development - Education, Sustainability, Multifunctionality

Poverty Reduction Strategies in Developing Countries

Submitted: 01 June 2021 Reviewed: 02 November 2021 Published: 02 February 2022

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.101472

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Rural Development - Education, Sustainability, Multifunctionality

Edited by Paola de Salvo and Manuel Vaquero Piñeiro

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

3,491 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

Overall attention for this chapters

The existence of extreme poverty in several developing countries is a critical challenge that needs to be addressed urgently because of its adverse implications on human wellbeing. Its manifestations include lack of adequate food and nutrition, lack of access to adequate shelter, lack of access to safe drinking water, low literacy rates, high infant and maternal mortality, high rates of unemployment, and a feeling of vulnerability and disempowerement. Poverty reduction can be attained by stimulating economic growth to increase incomes and expand employment opportunities for the poor; undertaking economic and institutional reforms to enhance efficiency and improve the utilization of resources; prioritizing the basic needs of the poor in national development policies; promoting microfinance programs to remove constraints to innovation, entrepreneurship, and small scale business; developing and improving marketing systems to improve production; providing incentives to the private sector; and, implementing affirmative actions such as targeted cash transfers to ensure that the social and economic benefits of poverty reduction initiatives reach the demographics that might otherwise be excluded.

- poverty reduction

- inclusive economic growth

Author Information

Collins ayoo *.

- Department of Economics, Carleton University, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

Poverty is a serious economic and social problem that afflicts a large proportion of the world’s population and manifests itself in diverse forms such as lack of income and productive assets to ensure sustainable livelihoods, chronic hunger and malnutrition, homelessness, lack of durable goods, disease, lack of access to clean water, lack of education, low life expectancy, social exclusion and discrimination, high levels of unemployment, high rate of infant and maternal mortality, and lack of participation in decision making [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Because poverty has deleterious impacts on human well-being, its eradication has been identified as an ethical, social, political and economic imperative of humankind [ 1 , 3 , 4 ]. Thus, the eradication of poverty and hunger were key targets in the Millennium Development Goals that the United Nations adopted in September 2000, and continue to be a priority in the pursuit of the Sustainable Development Goals that the United Nations General Assembly subsequently adopted in January 1, 2016 [ 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 ]. Although poverty exists in all countries, extreme poverty is more widespread in the countries in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia [ 8 , 10 ]. The causes of poverty in these countries are complex and include the pursuit of economic policies that exclude the poor and are biased against them; lack of access to markets and meaningful income-earning opportunities; inadequate public support for microenterprises through initiatives such as low interest credit and skills training; lack of infrastructure; widespread use of obsolete technologies in agriculture; exploitation of poor communities by political elites; inadequate financing of pro-poor programs; low human capital; conflicts and social strife; lack of access to productive resources such as land and capital; fiscal trap; and governance failures. Liu et al. [ 11 ], Beegle and Christiaensen [ 12 ], and Bapna [ 13 ] note that although considerable progress has been made to reduce poverty in the last two decades, more needs to be done to not only reduce the rate of extreme poverty further, but to also reduce the number of those living under extreme poverty. This is an important aspect of poverty reduction given that the rate of poverty can fall while the number of the poor is increasing simultaneously. For example, the poverty rate in Africa decreased from 54% in 1990 to 41% in 2015 but the number of the poor increased from 278 million in 1990 to 413 million in 2015. This constitutes a compelling case for robust well-thought out policies that not only stimulate economic growth but also produce outcomes that are inclusive and sustainable and address other dimensions of well-being such as education, health and gender equality [ 1 , 8 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Examples of poverty reduction initiatives that various countries have adopted are Ghana’s poverty reduction strategy, Ethiopia’s sustainable development and poverty reduction program, Kenya’s economic recovery strategy for wealth and employment creation, Senegal’s poverty reduction strategy, and Uganda’s poverty eradication action plan. Toye [ 21 ] notes that the measures outlined in these strategic policy documents have not been effective in reducing poverty because they were initiated as a condition for development assistance under the debt relief initiative of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. A critical analysis of the poverty reduction measures contained in these documents, however, reveals that to a large extent their failure to significantly reduce the incidence of poverty can be largely attributed to factors such as how the programs were designed, how the poverty reduction policies were targeted, and how they were implemented. This chapter is based on the premise that success in poverty reduction can be achieved by identifying who the poor are, assessing the extent of poverty in the different regions of developing countries, determining both the root causes of poverty and the opportunities that exist for reducing the incidences of poverty and improving the standards of living, and removing the various obstacles to poverty reduction [ 1 , 3 , 6 , 15 , 22 ]. The assumption that economic growth automatically results in a reduction of poverty also needs to be re-examined given the existence of empirical evidence that shows that economic growth can occur while poverty is worsening [ 8 , 16 , 17 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 ]. The focus needs to be on inclusive growth that addresses the unique needs of the poor and increases their access to basic services, employment and income generating opportunities, reliable markets for their products, information, capital and finance, and adequate social protections that remove the causes of the vulnerability of the poor [ 3 , 7 , 14 , 19 , 25 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ]. The experience of diverse rapidly growing developing countries demonstrates that with political will and visionary leadership that is committed to justice, equality, and rule of law, the goal of reducing poverty and improving the living standards of the poor is achievable. Sachs [ 4 ] notes that through such leadership the downward spiral of impoverishment, hunger, and disease that certain parts of the world are caught in can be reversed and the massive suffering of the poor brought to an end. Sachs is categorical that although markets can be powerful engines of economic development, they can bypass large parts of the world and leave them impoverished and suffering without respite. He advocates that the role of markets be supplemented with collective action through effective government provision of health, education and infrastructure. The World Bank [ 1 , 32 , 33 ], Acemoglu and Robinson [ 34 ], and Beegle and Christiaensen [ 12 ] argue that in much of Sub-Saharan Africa where agriculture is the main occupation, low agricultural productivity is a primary cause of poverty. They assert that the low agricultural productivity is a consequence of the ownership structure of the land and the incentives that are created for farmers by the governments and the institutions under which they live. More recently, the COVID-19 global pandemic has significantly increased the number of the newly poor. The World Bank [ 16 ] estimates that in 2020, between 88 million and 115 million people fell into extreme poverty as a result of the pandemic and that in 2021 an additional between 23 million and 35 million people will fall in poverty bringing the new people living in extreme poverty to between 110 million and 150 million. But the World Bank also points out that even before the pandemic, development for many people in the world’s poorest countries was too slow to raise their incomes, enhance living standards, or narrow inequality. Coates [ 35 ] contends that in February 2020, poverty was in fact increasing in several countries while many others were already off track to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 1. In what follows, I explore these issues and identify practical measures that can be applied to stimulate inclusive growth and reduce extreme poverty in developing countries. I also present some case studies to demonstrate how these measures have been successfully applied in various developing countries.

2. Some definitions and statistics

A clear definition of poverty is vital to identifying the causes of poverty, measuring its extent, and in assessing progress towards its eradication. The World Bank defines poverty in terms of poverty lines that are based on estimates of the cost of goods and services needed to meet the basic subsistence needs. Thus, the poor are regarded as those whose incomes is at or below specific poverty lines. The most commonly used international poverty line is $1.90 per day [ 5 , 17 ]. A concept that is closely related to the poverty line is the head count index which is the proportion of the population below the poverty line. Table 1 shows that Sub-Saharan Africa made significant progress in poverty reduction between 1990 and 2018 as indicated by the decrease in the head count index from 55–40%. Over this period, the population of Sub-Saharan Africa increased by 112% from 509.45 million to 1078.31 million and the population of the poor increased by 55% from 280.95 million to 435.56 million. This increase in the number of the poor by about 154.61 million is significant and suggests an urgent need to intensify poverty reduction efforts.

| Poverty line of US$ 1.90 | Poverty line of US$ 3.20 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Head count index | Number of the poor | Head count index | Number of the poor | |

| 1990 | 0.55 | 280.95 | 0.76 | 385.50 |

| 1995 | 0.60 | 352.76 | 0.79 | 463.37 |

| 2000 | 0.58 | 388.27 | 0.79 | 526.33 |

| 2005 | 0.52 | 393.57 | 0.76 | 574.25 |

| 2010 | 0.47 | 412.49 | 0.72 | 626.12 |

| 2015 | 0.42 | 417.60 | 0.68 | 679.09 |

| 2018 | 0.40 | 435.56 | 0.67 | 718.76 |

Head count index (%) and the number of the poor (millions) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: PovCalNet, World Bank.Online.

The rate of poverty in Sub-Saharan Africa is significantly greater if it is assessed using a $3.20 a day poverty line. Several researchers argue that $3.20 a day is a more realistic yardstick for assessing poverty and are critical of the commonly used $1.90 a day poverty line that they regard as being too low for standard of living assessments. As expected, Table 1 shows that over the period under consideration the poverty rates in Sub-Saharan Africa were higher using a $3.20 a day poverty line as compared to poverty rates estimated using a $1.90 a day poverty line. Specifically, using the $3.20 a day poverty line shows that the poverty rates were 76% in 1990 and declined to 67% in 2018. However, over 1990–2018 period, the number of those living in poverty increased by 333.26 million from 385.5 million to 718.76 million ( Figures 1 – 3 ).

Headcount index (%) sub-Saharan Africa. Source: PovCalNet [ 36 ], World Bank. Online.

Number of the poor (millions) in sub-Saharan Africa. Source: PovCalNet [ 36 ], World Bank. Online.

Poverty gap in sub-Saharan Africa. Source: PovCalNet [ 36 ], World Bank. Online.

A useful metric in analyzing poverty issues is the poverty gap which is the ratio by which the mean income of the poor fall below the poverty line. The poverty gap is an indicator of the severity of the poverty problem in any context and provides an estimate of the income that is needed to bring the poor out of poverty. The squared poverty gap is also an indicator of the severity of poverty and is computed as the mean of the squared distances below the poverty line as a proportion of the poverty a line. Its usefulness stems from the fact that it gives greater weight to those who fall far below the poverty line than those who are close to it. Estimates of the squared poverty gap can be used to more effectively target poverty alleviation policies to segments of communities that are more severely impacted by poverty and thus bring about better and more equitable outcomes. Some values of the squared poverty gaps for Sub-Saharan Africa are presented in Table 1 and depicted in Figure 4 . They corroborate the overall picture of the severity of poverty declining in sub-Saharan Africa between 1990 and 2018 ( Table 2 ).

Squared poverty gap in sub-Saharan Africa. Source: PovCalNet [ 36 ], World Bank. Online.

| Pov. Gap ($1.90) | Sq. Pov. Gap ($1.90) | Pov. Gap ($3.20) | Sq. Pov. Gap ($3.20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 0.25 | 0.15 | 0.42 | 0.28 |

| 1995 | 0.29 | 0.17 | 0.46 | 0.31 |

| 2000 | 0.27 | 0.16 | 0.45 | 0.30 |

| 2005 | 0.22 | 0.13 | 0.40 | 0.25 |

| 2010 | 0.19 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 0.22 |

| 2015 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.32 | 0.19 |

| 2018 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.31 | 0.18 |

Poverty gap and squared poverty gap (%) in sub-Saharan Africa.

Source: PovCalNet [ 36 ], World Bank.Online.

3. Poverty alleviation strategies

Poverty is a challenge that developing countries can overcome through, among others, good economic and social policies, innovative and efficient use of resources, investments in technological advancement, good governance, and visionary leadership with the political will to prioritize the needs of the poor. Sachs [ 4 ] notes that these elements are vital in enabling the provision of schools, clinics, roads, electricity, soil nutrients, and clean drinking water that are basic not only for a life of dignity and health, but also for economic productivity. In several countries measures are already being implemented to combat extreme poverty and improve the standards of living of the impoverished communities with steady progress being realized in several cases. Policy makers can learn important lessons from these poverty reduction measures and replicate and scale them up in other regions. Some strategies that developing countries can apply to reduce both the rate of poverty and number of the poor are:

3.1 Stimulating inclusive economic growth

Economic growth is vital in enabling impoverished communities to utilize their resources to increase both their output and incomes and thus break the poverty trap and be able to provide for their basic needs [ 1 , 4 , 19 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 25 , 37 , 38 ]. However, for economic growth to be effective in reducing poverty, it needs to be both inclusive and to occur at a rate that is higher than the rate of population growth. The fact that agriculture is the dominant economic sector in most poor communities implies that efforts to combat extreme poverty need to be directed towards increasing agricultural production and productivity [ 28 , 30 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 ]. Some concrete ways for achieving this overall goal include promoting the adoption of high yielding crop varieties and use of complementary inputs such as fertilizers and pesticides; intensifying the use of land through technological improvements such as increased use of irrigation where water is a constraint to agricultural production; and, adoption of post-harvesting measures that reduce the loss of agricultural produce. These measures are costly and are likely to be unaffordable to poor households. Their increased adoption requires the provision of cheap credit on terms that are flexible and aligned to the unique circumstances of the poor. How credit programs are designed is critical because it can have a significant impact on poverty reduction and livelihood outcomes [ 35 , 43 ]. When well designed, these programs can stimulate economic growth and enable poor communities to access financial capital for investment in income-generating activities. If poorly designed (e.g. if the interest rates are high and the repayment periods are short), credit programs can be not only exclusionary and inequitable, but the credit can also be misapplied, the poor entrapped in debt cycles, and economic growth and poverty reduction undermined.

Stimulating economic growth also requires public investments in infrastructure such as roads, electrical power, schools, hospitals, and water and sanitation systems [ 23 ]. These investments are important for several reasons. Good roads reduce transportation costs and generate diverse economic benefits that include increased ease of transporting agricultural produce to markets, ease of accessing agricultural inputs, and an increase in the profitability of income-generating businesses [ 23 ]. Providing electric power to impoverished areas not only results in improved standards of living but also stimulates the establishment of small-scale industries that process agricultural produce and thus contribute to value addition, in addition to creating much needed jobs. Providing safe, good-quality water for drinking and domestic use is vital in reducing incidences of debilitating water-borne diseases that are expensive to treat, saving time used to fetch water and enable the time and effort saved to be employed in more productive activities. More generally, investment in infrastructure will make rural economies more productive, increase household incomes, contribute to meeting basic needs, and enable greater saving for the future thus putting the economy on a path of sustainable growth [ 4 , 35 , 40 ].

A key challenge that developing countries face in providing the infrastructure they need is financing. On this issue several researchers advocate for increased use of foreign aid to finance public infrastructure in poor developing countries. According to Sachs [ 4 ], the rationale for this policy proposal is that developing countries are too poor and lack the financial resources for providing the infrastructure that they require to break the poverty trap and enable the provision of basic needs. He argues that if the rich world had committed $195 billion in foreign aid per year between 2005 and 2025, poverty could have been entirely eliminated by the end of this period. Moyo [ 44 ], Easterly [ 45 , 46 ], and Easterly and Levine [ 47 ] are however critical of foreign aid and assert that it not only undermines the ability of poor communities to develop solutions to their problems but also fosters corruption in governments and results in the utilization of the aid funds on non-priority areas. Banerjee and Duflo [ 43 ] and Page and Pande [ 23 ] opine that foreign aid can foster economic growth if well-targeted and used efficiently. They however point out that in most cases foreign aid is a small fraction of the overall financing that is required and that developing countries must increasingly rely on their own resources that are generated through taxes. Successful financing of critical infrastructure and social services will therefore require more efficient expenditures of public resources and the eradication of corruption in governments.

3.2 Economic and institutional reforms

An important step in reducing poverty in developing countries is the implementation of economic and institutional reforms to create conditions that attract investment, enhance competitiveness, ensure increased efficiency in the use of resources, stimulate economic growth, and create jobs. If well designed and implemented, these reforms can be instrumental in strengthening governance and reducing endemic corruption and poor accountability that have contributed to the poor economic performance of several developing countries [ 23 , 27 ]. Some reforms that are needed include the strengthening of land tenure systems to encourage risk-taking and investment in productive income-generating activities; improving governance to ensure greater inclusivity, transparency and accountability; reducing the misuse of public resources and unproductive expenditures; ensuring a greater focus on the needs and priorities of the poor; maintaining macroeconomic stability and addressing structural constraints to accelerating growth e.g. by reducing the high costs of doing business and excessive regulatory burdens; and involving the poor, women, and the youth in decision-making [ 8 ]. These reforms can benefit the poor by improving their access to land and other productive resources and by ensuring that their needs and priorities are adequately considered in policy making. Developing countries also need to reform their tax systems to make them more efficient and pro-poor.

3.3 Promoting microfinance institutions and programs

Lack of finance is a major constraint to the establishment of small scale businesses and other income generating activities in impoverished communities in several developing countries [ 48 , 49 ]. Through microfinance institutions, this constraint can be removed and the much-needed credit provided to small businesses that are often unable to access credit from formal financial institutions. In this way, micro-credit can be instrumental in stimulating economic activity, creating jobs in the informal sector, increasing household incomes, and reducing poverty [ 1 , 3 , 28 , 43 , 48 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. Vatta [ 53 ] has noted that microfinance institutions have good potential to reach the rural poor and to address the basic issues of rural development where formal financial institutions have not been able to make a significant impact. Some advantages of obtaining credit from microfinance institutions include less stringent conditions with regard to providing collateral thus easing access to credit; the possibility of the poor obtaining small amounts of loans more frequently thus enabling the credit needs for diverse purposes and at shorter time intervals to be met; reduced transaction costs; flexibility of loan repayment; and an overall improvement in loan repayment. The small informal self-help groups that are often the units for microcredit lending are also valuable for social empowerment and fostering learning, the development of skills, entrepreneurship, exchange of ideas and experiences, and greater accountability by the group members [ 49 , 54 ]. Sachs [ 4 ] supports microfinance as a viable and promising path to poverty alleviation and cites Bangladesh as a country where micro-credit has contributed to a reduction in poverty through group lending that enabled impoverished women who were previously considered unbankable and not credit worthy to obtain small loans as working capital for microbusiness activities. He further notes that by opening to poor rural women improved economic opportunites, microcredit can be instrumental in reducing fertility rates and thus improve the abilities of households to save and provide better health and education for their children.

3.4 Improving the marketing systems

According to Karnani [ 55 ], the best way to reduce poverty is to raise the productive capacity of the poor. Efficient marketing systems are vital in enabling the poor to increase their production because they permit the delivery of products to markets at competitive prices that result in increased incomes. This is also the reason why developing countries need to explore ways of expanding export markets. The plight of cotton, rice, tea, coffee, and cashew nut farmers in Kenya demonstrates the importance of improving the marketing systems. Weaknesses and inefficiencies in the marketing of these commodities has resulted in the impoverishment of the farmers who face problems such as damage to their harvests, low commodity prices and thus low profits and incomes, and exploitation by middlemen. By improving the marketing system, the growers of these commodities can benefit from better storage that would cushion them from price fluctuations, the pooling of their resources that would enable a reduction of their costs, and the processing of their products to enable value-addition and an improvement on the returns. The implementation of these measures can stimulate local, regional, and national economies; underpin the establishment of a robust agro-industrial sector; create jobs; increase production and incomes; and, contribute to equitable and sustained reduction of poverty.

3.5 Cash/income transfer programs

The fight against poverty needs to consider the fact that among the poor are those who cannot actively participate in routine economic activities and are therefore likely to suffer exclusion from the benefits of economic growth. This category of the poor include the old and infirm, the sick and those afflicted by various debilitating conditions, families with young children, and those who have been displaced by war and domestic violence. Special affirmative actions that transfer incomes to these groups are required to provide for their basic needs and ensure more equity in poverty reduction. In impoverished regions where children contribute to the livelihoods of their families by supplying agricultural labor and participating in informal businesses, income transfer programs can provide families with financial relief and enable regular school attendance by children. Such investment in the education of the children is vital in improving their human capital and prospects for employment and can therefore play an important role in long term poverty reduction [ 7 , 8 , 56 ]. Kumara and Pfau [ 57 ] analyzed such programs in Sri Lanka and found that cash transfers in the country significantly reduced child poverty and also increased school attendance and child welfare. Barrientos and Dejong [ 58 ], Monchuk [ 59 ], Banerjee et al. [ 60 ], Page and Pande [ 23 ], Hanna and Olken [ 61 ], and World Bank [ 8 ] strongly support cash transfer programs and contend that these programs are a key instrument in reducing poverty, deprivation, and vulnerability among children and their households. They cite South Africa, Bangladesh, Brazil, Mexico and Chile as examples of countries where cash transfer programs have significantly reduced poverty and vulnerability among poor households. They also point out that cash transfer programs are beneficial to households because they are flexible and enhance the welfare of households given that households are free to use the supplemental income on their priorities.

Cash transfer programs are central to social protection that is much needed in developing countries that face heightened social and economic risks due to structural adjustments driven by globalization. As noted by Sneyd [ 2 ], Monchuk [ 59 ], Barrientos et al. [ 62 ], and Barrientos and Dejong [ 58 ], globalization has resulted in greater openness of developing economies and exposed them to changes in global markets leading to a greater concentration of social risk among vulnerable groups. They regard social protection as the most appropriate framework for addressing rising poverty and vulnerability in the conditions that prevail in developing countries. They recommend that if significant and sustained reduction in poverty is to be achieved, cash transfer programs be accompanied by complementary actions that extend economic opportunities and address the multiple dimensions of poverty such as food, water, sanitation, health, shelter, education and access to services. Fiszbein et al. [ 29 ] strongly support the increased use of social protection programs such as cash transfers to alleviate extreme povery and estimate that in 2014 these programs prevented about 150 million people from falling into poverty. It needs to be noted that although well designed cash transfer programs can be effective in reducing poverty, they are expensive and may be difficult to finance in a sustained manner [ 23 ]. However, by reducing wasteful expenditures and instituting tax reforms, the required resources can be freed for investment in cash transfer programs [ 29 ]. The viability of this approach is evident in the case of Bangladesh and a number of central Asian countries that have been able to successfully finance cash transfers from their national budgets. Countries that are not able to finance cash transfer programs from their own resources need to explore the possibilities of securing medium-term support from international organizations [ 4 , 7 , 29 , 58 , 63 ].

A major concern that several researchers have expressed regarding cash transfer programs is that they have a short term focus of alleviating only current poverty and have thus failed to generate sustained decrease in poverty independent of the transfer themselves. Critics of cash transfers also argue that they are a very cost ineffective approach to poverty alleviation and an unnecessary waste of scarce public resources. Furthermore, they claim that many cash transfer programes are characterized by unnecessary bureaucracy, high administrative costs, corruption, high operational inefficiencies, waste, and poor targeting. The overall result of these weaknesses is that program benefits have to a large extent failed to reach the poorest households. Where these shortcomings exist, they need to be identified through rigorous audits and addressed through improved program design. But more fundamentally, it also needs to be recognized that cash transfer programs are not simply handouts but are investments in poor households that regard the programs as their only hope for a life free from chronic poverty, malnutrition and disease.

4. Selected case studies on poverty reduction in developing countries

The goal of poverty reduction can be achieved through sound policies that address the root causes of poverty, promote inclusive economic growth, prioritize the basic needs of the poor, and provide economic opportunities that empower the poor and enable them to improve their standards of living [ 6 , 8 , 64 ]. In what follows we present a few case studies from sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and Latin America to illustrate real world examples of policies that have resulted in significant reduction in poverty. Policy makers can learn important lessons from these case studies in their attempts to combat poverty in different contexts.

4.1 Sub-Saharan Africa

Several countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have developed poverty reduction plans that are currently being implemented to improve the standards of living of the poor and vulnerable. In Kenya where poverty is widespread and is estimated to exceeed 60 percent, the key elements of the poverty reduction strategy are facilitating sustained and rapid economic growth; increasing the ability of the poor to raise their incomes; improving the quality of life of the poor; improving equity and the participation of the poor in decision-making and in the economy; and improving governance and security [ 65 ]. The government has also implemented macroeconomic reforms to reduce domestic debt burden and high interest rates - this is expected to promote higher private-sector led growth and thus contribute to poverty reduction. An important action that is being carried out to reduce poverty in Kenya is promoting agricultural production. This focus is underpinned by the fact that the majority of Kenyans derive their livelihoods and income from agriculture and live in rural areas. Some specific poverty reduction measures in Kenya that target the agricultural sector include providing subsidized fertilizers and seeds; encouraging the growing of high value crops; rehabilitation and expansion of irrigation projects; and, provision of subsidized credit to alleviate capital contraints. To support agricultural production, the government has also prioritized the strengthening and streamling of the marketing system and the expansion of rural roads to improve the access of the poor to markets, increase economic opportunities, and create employment. Robust efforts are also underway to increase agricultural exports as a means for stimulating domestic agricultural production and increasing the country’s foreign exchange earnings. Other poverty reduction measures that are being implemented in Kenya are the promotion of small scale income generating enterprises; subsidization of education and health care to reduce the costs to poor households; school-feeding programs; rural employment schemes through public works projects; investments in technical and vocational training to enable the youth acquire skills in areas such as carpentry, masonry, and, auto mechanics; and, family planning programs to reduce the fertility rates.

In collaboration with international development partners, Kenya and other low and middle income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa have been implementing cash transfer programs on a limited scale to address extreme poverty and assist vulnerable households. The cash transfers were unconditional in the intial phases with disbursements made to all applicants. Subsequently however, and based on the lessons learned from the earlier phases, several countries have redesigned their cash transfer programs and made them conditional and contingent on means-testing. This is important given the severe budget contraints that developing countries face, the need to target the cash transfers on the poorest and most vulnerable households, and the need to ensure that social protection expenditures are efficient and result in the greatest reduction in poverty. Egger et al. [ 66 ] conducted an empirical study of a cash transfer program in rural western Kenya between mid-2014 and early 2017 and concluded that the program had several positive effects on both the households that received the cash transfers and those that did not. Some specific benefits attributable to the cash transfer program were an increase in consumption expenditures and holdings of durable assets by households; increased demand-driven earnings by local enterprises; increased food security; improved child growth and school attendance; improvement in health of members of the recipient households; female empowerment; and, enhanced psychological well-being. Furthermore, the cash transfer program had a stimulatory effect on local economic activities and these effects persisted long after the cash disbursements. The experience with cash transfer programs demonstrates that they can contribute significantly to a reduction in extreme poverty if they are scaled up, and if they are well designed and targeted at the poorest households.

Since March of 2020, Kenya’s progress in poverty reduction has been adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic that is estimated to have increased the number of the poor by an additional 2 million through adverse impacts on incomes and jobs [ 24 , 67 ]. The containment measures that were implemented in response to the pandemic significantly slowed economic activity, reduced revenues from household-run businesses, exacerbated food insecurity, and posed a serious threat to the lives and livelihoods of large segments of the population. Some of the actions that the government of Kenya took to address these challenges included allocating more resources to the healthcare sector to combat the pandemic; instituting taxation and spending measures to support healthy firms from permanent closure in order to protect jobs, incomes and the productive capacity of the economy; and, scaling-up social protection programs to offset the increase in poverty and protect the most vulnerable households [ 24 , 67 ].

A number of countries in Asia have developed and implemented programs that have been impactful in significantly reducing extreme poverty. According to the Asian Development Bank (ADB) [ 68 ], these programs were predicated on rapid economic growth driven by innovation, structural reform, and the application of private sector solutions in the public sector. Asia’s progress in raising prosperity and reducing poverty is evident from the fact that since 1990 over a billion people have emerged from extreme poverty and also from the fact that in the decade spanning 2005–2015 more that 611 million people were lifted out of extreme poverty – four-fifths of these were in China (234 million) and India (253 million) [ 68 ]. The general approach that governments of Asia have taken to poverty reduction include accelerating economic growth, increasing the delivery of social services, developing lagging areas, increasing investments to generate jobs, promoting small and medium-sized enterprises, redistributing incomes, balancing rural–urban growth, and developing social protection interventions [ 68 , 69 ].

An example of a successful poverty reduction initiative in Asia is the Shanxi Integrated Agricultural Development Project (SIADP) that was implemented between 2009 and 2016 in the Shanxi province in China with a $ 100 million loan from the ADB. The goal of the SIADP was to improve agricultural production in the region as a way to stimulate economic growth and reduce the level of poverty. Prior to the implementation of the SIADP most farmers in Shanxi province mainly grew wheat and corn that generated low incomes and required extensive use of water and agrochemicals. The farmers in the region also engaged in free-range livestock grazing, an environmentally unsustainable practice that resulted in soil and water pollution from uncontrolled disposal of untreated animal waste. They were also unorganized and did not have good access to markets and finance, and the participation of women in the economy was marginal and their social and economic rights ignored. According to the ADB [ 68 ], the SIADP was implemented by first training farmers in improved production techniques that resulted in the development of a sustainable agricultural sector with the farmers starting to grow high-value crops, and forming contract farming agreements with agro-enterprises that enabled the farmers to gain access to stable markets and premium prices for their produce. The farmers also started breeding and raising livestock under more controlled conditions that enabled not only an increase in livestock output but also the turning of animal waste into compost or biogas which is a source of clean energy. These measures were instrumental in stimulating the region’s bioeconomy, improving the quality of the environment, increasing farm incomes, and reducing the level of poverty in Shanxi province.

Social protection programs are vital in cushioning poor and vulnerable households from crises they are unable to cope with and that are likely to cause an overall reduction and degradation of their physical and social assets [ 68 ]. This is exemplified by the food stamp program that was implemented in 2008 through a partnership between the Government of Mongolia and the ADB. The food stamp program was put in place at a time when the overall poverty rate in Mongolia was 32.6 percent of the population with about 5 percent of the population being categorized as extremely poor. There was also a high level of food insecurity in the country and a high inflation rate that had reached 32.2 percent [ 68 ]. To help reduce the adverse impact of food insecurity and high inflation, the government of Mongolia established a food subsidy program that targeted poor households. The program was very effective in assisting the poor to buy enough floor, rice and other basic commodities and also freed up money that the poor could then spend on other necessities. Following the introduction of this program, school attendance by children increased and their mean grades improved [ 68 ]. The program also supported the poor households in developing alternative food sources. The ADB [ 68 ] notes that the participants in the food stamp program also learned valuable skills in backyard gardening, food storage and food preservation with many of them reporting significant earnings from vegetable production. Thus, the program contributed directly to poverty reduction by mitigating the adverse effects of the food and financial crises on the poor and is a strategy that developing countries need to seriously consider in their efforts to reduce povery and improve living standards.

4.3 Latin America

As a region, Latin America has performed reasonably well in reducing extreme poverty and boosting shared prosperity [ 70 ]. A country-specific assessment however reveals a significant heterogeneity across and within the countries in the region. The countries that have performed well include Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Panama, Uruguay, and Peru while those that have performed poorly include Guatemala, Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua and the Dominican Republic. For the well-performing countries, the reasons include rapid and inclusive economic growth, and the adoption of redistributive policies such as improved access to education, healthcare, and social protections. In these countries, there has been a significant increase in the participation of the poor in labor markets thus enhancing their ability to generate labor income. Cord et al. [ 70 ] assert that the growth in female labor force participation in particular has been strong and has contributed to the substantial drop in poverty rates that has been observed in the well-performing countries. It is worth noting that these gains in poverty reduction and promotion of shared prosperity have been aided by prudent macro fiscal economic policies and positive terms of trade. These countries have also benefitted immensely from remittance flows that have not only complemented the expansion of government transfers and the broadening of pension coverage but have also enabled greater macroeconomic stability, higher savings, more entrepreneurship and better access to healthcare and education. In a country like El Salvador which is one of the largest remittance-receiving countries in the region, these private remittances have played a major role in poverty reduction [ 70 ]. Although, the income transfer programs that several countries in Latin America have implemented have been effective in reducing persistent intergenerational poverty, the incidence of poverty in the region has remained high due, in part, to the limited scale of these programs and weaknesses in their design [ 71 ]. By supplementing household consumption, these programs are playing a key role in human development and preventing future poverty because present consumption improves productive capacity through the expected positive impact of improved nutrition and health status on labour productivity [ 71 ]. Further reduction in poverty in the region requires not only the scaling up of the income transfer programs and improvements in their design to ensure greater efficiency in service delivery, but also the redressing of other critical drivers of poverty such as the long-standing inequalities in access to land and other productive resources [ 71 ]. A problematic issue that needs to be addressed is the over-reliance of these programs on external financing; it poses to policy-makers the challenge of identifying and crafting alternative sources of financing to ensure the sustainability of these programs.

5. Conclusions and policy implications

Poverty is a serious challenge that developing countries are facing today and requires focused and sustained action to significantly reduce it, break the cycle of poverty, and improve the standards of living. Although income is the yardstick that is most commonly used to measure and assess it, poverty is multidimensional and entails diverse aspects of well-being that include food, water, sanitation, health, shelter, education, access to services and human rights [ 20 ]. According to the World Bank, the extent of poverty is highest in Sub Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America where the number of the poor has been increasing due to high population growth and modest economic performance in these regions. Various reports also indicate that the youth are the majority of the population in these countries so that targeting them can be effective in reducing poverty. Developing countries are currently in various stages implementing policies aimed at reducing poverty and vulnerability, and improving the standards of living. Promoting inclusive economic growth is vital not only in increasing output and incomes but also in ensuring that the benefits of economic growth are broadly shared. Some ways of promoting inclusive economic growth are investing in infrastructure and technology; liberalizing trade and expanding export markets; providing incentives to small and medium businesses; providing fiscal stimulus to the economy; ensuring macroeconomic stability; and improving public management and governance [ 8 , 26 , 33 ]. The implementation of these measures in an integrated manner can have positive economy wide effects, incentivize the private sector, create the much needed employment opportunities, and reduce the levels of poverty.

Poverty reduction can also be enhanced through microfinance institutions that not only provide credit to small borrowers who are often unable to access credit from formal financial institutions, but also mobilize domestic savings and channel these savings towards income generating activities [ 43 ]. This role of microfinance institutions is particularly important in developing countries where most businesses are small scale and face severe financing constraints [ 43 , 48 , 51 , 52 ]. The available empirical evidence demonstrates that microfinance has been instrumental in supporting income generating activities in impoverished regions and thus contributed to the provision of basic needs and reduction of poverty. Developing countries can also address the challenge of poverty by improving the efficiency and competitiveness of their economies. This can be accomplished through economic and institutional reforms that reduce the cost of doing business, strengthen the linkages between various sectors of the economy, protect property rights, reduce corruption, and foster greater accountability in public management. Tax regimes also need to be reformed to make them more efficient, provide incentives to small businesses, effect redistribution in favor of the poor, and generate more resources that can be used to finance critical services such as education, health, water and sanitation, and shelter for the poor. Furthermore, through tax reforms employment opportunities can be expanded as a key step in poverty reduction. Finally, carefully designed affirmative actions and social protection programs need to be included as a key pillar of the poverty reduction strategies of developing countries given that there will invariably be groups in society whose unique circumstances result in their exclusion from the economic and social benefits of conventional poverty reduction measures. This is the rationale for the cash transfer programs that several developing countries are increasingly implementing to reduce poverty and vulnerability. The private sector and international development institutions can play an important role in poverty reduction in developing countries by providing expertise and the supplemental resources and assistance that are needed to implement poverty reduction plans. Success in poverty eradication requires a focus on areas where poverty is widespread and the use of innovative and practical policy instruments that are most likely to lift the greatest number of the poor out of poverty. It is a goal that is attainable through collaboration among all stakeholders, prioritization of the basic needs of the poor, the determination to improve economic performance to realize inclusive economic growth and break the vicious cycle of povery, empowering the poor to take control of their future, and by mainstreaming poverty reduction into national policies and actions.

- 1. World Bank. World Development Report 1990: Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 1990a

- 2. Sneyd A. The poverty of ‘poverty reduction’: The case of African cotton. Third World Quarterly. 2015; 36 (1):55-74

- 3. World Bank. World Development Report 2000/2001: Attacking Poverty. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001

- 4. Sachs JD. The End of Poverty: The Economic Possibilities for Our Time. New York: Penguin Press; 2005

- 5. Ferreira FH, Chen S, Dabalen A, Dikhanov Y, Hamadeh N, Jolliffe D, et al. A global count of the extreme poor in 2012: Data issues, methodology and initial results. Journal of Economic Inequality. 2016; 14 :1-32

- 6. World Bank. Monitoring Global Poverty: Report of the Commission on Global Poverty. Washington, DC; 2017a

- 7. World Bank. Closing the Gap: The State of Social Safety Nets 2017. Washington, DC: Technical report; 2017b

- 8. World Bank. Global Monitoring Report 2014/2015: Ending Poverty and Sharing Prosperity. Washington, DC; 2015

- 9. Alkire S, Roche JM, Vaz A. Changes over time in multidimensional poverty: Methodology and results for 34 countries. World Development. 2017; 94 :232-249

- 10. Hamel, K., B. Tong and M. Hofer. 2019. Poverty in Africa is Now Falling-but not Fast Enough. Future Development. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/futuredevelopment/2019/03/28/poverty-in-africa-is-now-falling-but-not-fast-enough/ [Accessed: 27, April; 2021]

- 11. Liu M, Feng X, Wang S, Qiu H. China’s poverty alleviation over the last 40 years: Successes and challenges. The Australian Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics. 2020; 64 (1):209-228

- 12. Beegle K, Christiaensen L, editors. Accelerating Poverty Reduction in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2019

- 13. Bapna M. World poverty: Sustainability is key to development goals. Nature. 2012; 489 :367

- 14. Ferreira FH, Leite PG, Ravallion M. Poverty reduction without economic growth? Journal of Development Economics. 2010; 93 (1):20-36

- 15. United Nations. Report of the World Summit for Social Development, New York; 1995. p. 1995

- 16. World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2020: Reversals of Fortune. Washington, DC; 2020a

- 17. World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2018: Piecing Together the Poverty Puzzle. Washington, DC; 2018

- 18. World Bank. World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development. Washington, DC; 2012

- 19. Dollar D, Kraay A. Growth is good for the poor. Journal of Economic Growth. 2002; 7 (3):195-225

- 20. Singh PK, Chudasama H. Evaluating poverty alleviation strategies in a developing country. PLoS One. 2020; 15 (1):e0227176. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0227176

- 21. Toye J. Poverty reduction. Development in Practice. 2007; 17 (4/5):505-510

- 22. Moser CON. The asset vulnerability framework: Reassessing urban poverty reduction strategies. World Development. 1998; 26 (1):1-19

- 23. Page L, Pande R. Ending global poverty: Why money isn’t enough. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2018; 32 (4):173-200

- 24. World Bank. 2020b. Kenya Economic Update: Navigating the Pandemic, November 2020 | Edition No. 22, Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/34819/Kenya-Economic-Update-Navigating-thePandemic.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- 25. World Bank. Poverty and Shared Prosperity 2016: Taking on Inequality. Washington, DC; 2016

- 26. Ravallion M, Chen S. China’s (uneven) progress against poverty. Journal of Development Economics. 2007; 82 (1):1-42

- 27. Arndt C, McKay A, Tarp F. Growth and Poverty in sub-Saharan Africa. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press; 2016

- 28. Narayan-Parker D. Empowerment and Poverty Reduction: A Sourcebook. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; 2002

- 29. Fiszbein A, Kanbur R, Yemtsov R. Social protection and poverty reduction: Global patterns and some targets. World Development. 2014; 61 :167-177

- 30. World Bank. Growing the Rural Non-Farm Economy to Alleviate Poverty: An Evaluation of the Contribution of the World Bank Group. Washington, DC; 2017c

- 31. Kraay A. When is growth pro-poor? Evidence from a panel of countries. Journal of Development Economics. 2006; 80 (1):198-227

- 32. World Bank. World Development Report 2008: Agriculture for Development. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008

- 33. World Bank. Entering the 21st Century: World Development Report 1999/2000. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000

- 34. Acemoglu D, Robinson JA. Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Currency; 2012

- 35. Coates, L. 2021. How An Evidence-Based Program from Bangladesh could Scale to End Extreme Poverty. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/future-development/2021/02/11/how-an-evidence-based-program-from-bangladesh-could-scale-to-end-extreme-poverty/ [Accessed: October 17, 2021]

- 36. PovCalNet, World Bank. Available from: http://iresearch.worldbank.org/PovcalNet/jsp/index.jsp

- 37. Beegle K, Christiaensen L, Dabalen A, Gaddis I. Poverty in a Rising Africa. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; 2016

- 38. Bloeck MC, Galiani S, Weinschelbaum F. Poverty alleviation strategies under informality: Evidence for Latin America. Latin American Economic Review. 2019; 28 (14):1-40

- 39. Van den Broeck G, Maertens M. Moving up or moving out? Insights into rural development and poverty reduction in Senegal. World Development. 2017; 99 :95-109

- 40. Mellor JW, Malik SJ. The impact of growth in small commercial farm productivity on rural poverty reduction. World Development. 2017; 91 :1-10

- 41. Malumfashi SL. The concept of poverty and its various dimensions. In: Duze MC, Mohammed H, Kiyawa IA, editors. Poverty in Nigeria Causes, Manifestations and Alleviation Strategies. First ed. London: Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.; 2008, 2008

- 42. Aliyu SUR. Poverty: Causes, nature and measurement. In: Duze MC, Mohammed H, Kiyawa IA, editors. Poverty in Nigeria Causes, Manifestations and Alleviation Strategies. First ed. London: Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd.; 2008

- 43. Banerjee AV, Duflo E. Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: Public Affairs; 2012

- 44. Moyo D. Dead Aid: Why Aid is Not Working and How there is a Better Way for Africa. London: Allen Lane; 2009

- 45. Easterly W. The White Man’s Burden: Why the West’s Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2006

- 46. Easterly W. The Elusive Quest for Growth: Economists’ Adventures and Misadventures in the Tropics. Cambridge: MIT Press; 2001

- 47. Easterly W, Levine R. Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic division. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1997; 112 (4):1203-1250

- 48. Imai K, Arun T, Annim S. Microfinance and household poverty reduction: New evidence from India. World Development. 2010; 38 (12):1760-1774

- 49. Bruton GD, Ketchen DJ, Ireland RD. Entrepreneurship as a solution to poverty. Journal of Business Venturing. 2013; 28 (6):683-689

- 50. Gulyani S, Talukdar D. Inside informality: The links between poverty, microenterprises, and living conditions in Nairobi’s slums. World Development. 2010; 38 (12):1710-1726

- 51. Banerjee AV, Duflo E. The economic lives of the poor. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2007; 21 (1):141-168

- 52. Hermes N. Does microfinance affect income inequality? Applied Economics. 2014; 46 (9):1021-1034

- 53. Vatta K. Microfinance and poverty alleviation. Economic and Political Weekly. 2003; 38 (5):32-33

- 54. Si S, Yu X, Wu A, Chen S, Chen S, Su Y. Entrepreneurship and poverty reduction: A case study of Yiwu, China. Asia Pacific Journal of Management. 2015; 32 (1):119-143

- 55. Karnani A. Marketing and poverty alleviation: The perspective of the poor. Markets, Globalization & Development Review. 2017; 2 (1):1. DOI: 10.23860/MGDR

- 56. Toye J, Jackson C. Public expenditure policy and poverty reduction: Has the World Bank got it right? Institute of Development Studies Bulletin. 1996; 27 (l):56-66

- 57. Kumara AS, Pfau WD. Impact of cash transfer programmes on school attendance and child poverty: An ex ante simulation for Sri Lanka. The Journal of Development Studies. 2011; 47 (11):1699-1720

- 58. Barrientos A, Dejong J. Child poverty and cash transfers. In: CHIP Report, No. 4. London: Childhood Poverty Research and Policy Centre; 2004

- 59. Monchuk V. Reducing Poverty and Investing in People: The New Role of Safety Nets in Africa. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2013

- 60. Banerjee AV, Hanna R, Kreindler GE, Olken BA. Debunking the stereotype of the lazy welfare recipient: Evidence from cash transfer programs. The World Bank Research Observer. 2017; 32 (2):155-184

- 61. Hanna R, Olken BA. Universal basic incomes versus targeted transfers: Anti-poverty programs in developing countries. Journal of Economic Perspectives. 2018; 32 (4):201-226

- 62. Barrientos A, Hulme D, Shepherd A. Can social protection tackle chronic poverty? The European Journal of Development Research. 2005; 17 (1):8-23

- 63. Coady D. Alleviating Structural Poverty in Developing Countries: The Approach of Progresa in Mexico, mimeo. Washington DC: International Food Policy Research Institute; 2003

- 64. Ravallion M. Growth and poverty: Evidence for developing countries in the 1980s. Economics Letters. 1995; 48 :411-417

- 65. Republic of Kenya. Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper 2001-2004 Vols. I & II. Nairobi: Government Printer; 2001

- 66. Egger D, Haushofer J, Miguel E, Niehaus P, Walker MW. General Equilibrium Effects of Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 26600. Cambridge Massachusetts; 2021. Available from: https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w26600/w26600.pdf [Accessed on December 12, 2021]

- 67. World Bank. Kenya Economic Update: Rising Above the Waves. Washington, DC; 2021 Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/35946

- 68. Asian Development Bank (ADB). Effective Approaches to Poverty Reduction: Selected Cases from the Asian Development Bank. Manila, Philippines : Asian Development Bank Institute; 2019

- 69. Glauben T, Herzfeld T, Rozelle S, Wang X. Persistent poverty in rural China: Where, why and how to escape? World Development. 2012; 40 :784-795

- 70. Cord L, Genoni ME, Rodríguez-Castelán C. Shared Prosperity and Poverty Eradication in Latin America and the Caribbean. Washington, D.C.: World Bank; 2015

- 71. Barrientos A, Santibañez C. Social policy for poverty reduction in lower-income countries in Latin America: Lessons and challenges. Social Policy and Administration. 2009; 43 (4):409-424

© 2021 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Rural development.

Edited by Paola de Salvo and Manuel Vaquero Pineiro

Published: 02 February 2022

By Okanlade Adesokan Lawal-Adebowale

1068 downloads

By Austine Phiri

400 downloads

By Jacob Alhassan Hamidu, Charlisa Afua Brown and Mar...

460 downloads

IntechOpen Author/Editor? To get your discount, log in .

Discounts available on purchase of multiple copies. View rates

Local taxes (VAT) are calculated in later steps, if applicable.

Support: [email protected]

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Poverty in America — Causes And Effects Of Poverty

Causes and Effects of Poverty

- Categories: Child Poverty Poverty in America

About this sample

Words: 736 |

Published: Jun 13, 2024

Words: 736 | Pages: 2 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Underlying causes of poverty, effects on individuals and communities, breaking the cycle.

Cite this Essay

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below:

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 1135 words

1 pages / 477 words

1 pages / 650 words

4 pages / 1975 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Poverty in America

Homelessness started to become a dilemma since the 1930s leaving millions of people without homes or jobs during The Great Depression. Homeless people face numerous challenges every day dealing with shelters and food in order to [...]

Dorothy Allison's essay "A Question of Class" delves into the complexities of social class and its impact on individuals' lives. The essay explores the ways in which class influences one's identity, opportunities, and [...]

Poverty in America stands as a paradox in a nation renowned for its wealth and opportunity. Despite being one of the world's richest countries, the United States struggles with significant levels of poverty that affect millions [...]

Michael Patrick MacDonald’s memoir, All Souls, provides a poignant and raw account of growing up in South Boston during the 1970s and 1980s. The book explores themes of poverty, violence, and racism, as well as the impact of [...]

A small boy tugs at his mother’s coat and exclaims, “Mom! Mom! There’s the fire truck I wanted!” as he gazes through the glass showcase to the toy store. The mother looks down at the toy and sees the price, she pulls her son [...]

In today's society, poverty remains a pervasive and pressing issue that affects millions of individuals worldwide. From lack of access to basic necessities such as food, shelter, and healthcare, to limited opportunities for [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- General Assembly

- Second Committee

Extreme Poverty in Developing Countries Inextricably Linked to Global Food Insecurity Crisis, Senior Officials Tell Second Committee

Delegates warn agriculture sector underdeveloped, underfunded, beset by crises.

An increase in extreme poverty in developing countries — for the first time in two decades — is inextricably linked to the global food insecurity crisis , senior United Nations officials warned the Second Committee (Economic and Financial) today, calling for urgent strategies to turn back the tide.

Benjamin Davis, Director of the Inclusive Rural Transformation and Gender Equality Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), presented reports of the Secretary-General titled “Eradicating rural poverty to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (document A/78/238 ) and “Agriculture development, food security and nutrition” (documents A/78/218 , A/78/233 , A/78/74 ). He noted that more than 80 per cent of the world’s extreme poor live in rural areas — at rates nearly three times higher than among urban residents. He called for the implementation of inclusive, environmentally sustainable strategies that put the eradication of rural poverty at the centre.

Turning to the report on agriculture development, food security and nutrition, he said that some 29.6 per cent of the global population — 2.4 billion people — were moderately or severely food-insecure in 2022, 391 million more than in 2019, with more women and people in rural areas denied access to safe, nutritious and sufficient food year-round. A long-term, holistic approach is needed to address structural problems such as political and economic shocks, unsustainable management of natural resources and socioeconomic exclusion.

Similarly, John Wilmoth, Officer-in-Charge of the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, introduced the report of the Secretary-General titled “Implementation of the third United Nations Decade for the Eradication of Poverty (2018-2027)” (document A/78/239 ), spotlighting that about 670 million people were estimated to be living in extreme poverty in 2022, an increase of 70 million people compared with pre-pandemic projections. He stressed that the poorest countries spent billions on debt payments, preventing them from investing in sustainable development.

In the ensuing debate, speakers echoed the urgency of addressing the dangers of the regressive poverty trend. Congo’s representative lamented that, after recording substantial progress in reducing extreme poverty, the world now finds itself in a state of indescribable poverty. He called for urgent action to reverse the negative trends, highlighting the need to connect rural and urban areas with infrastructure, public goods and capacity-building, as “eradicating poverty in all its forms is essential”.

The representative of Nepal, speaking on behalf of the Group of Least Developed Countries, noted that those States are host to over half of the world’s extreme poor, facing “unprecedented levels of hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition”. Agriculture, being the most important sector of the economy for these countries, has been hard hit by conflicts, leading to high costs of agricultural inputs and fertilizer shortages, a result of which “about two thirds of people facing extreme poverty in the world are workers and families in the agriculture sector”.

Viet Nam’s delegate, speaking on behalf of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), recalled that agriculture provided employment for as much as 32 per cent of the region’s population and 22 per cent of gross domestic production. Citing its significant contribution towards poverty eradication and the reduction of hunger, he added that sustainable agriculture and food systems are important to ensure the availability, affordability and sustainability of food products for all. The reduction of poverty and the promotion of rural development are therefore key priorities.

The representative of Nicaragua, stressing the key priority of eradicating extreme poverty, called for a new global order and a multipolar world characterized by transparent, equitable agreements and solidarity. Many developing countries struggle with indebtedness, requiring the financial system to put forward monetary policies that are fair. She also criticized illegal unilateral coercive measures imposed by imperial and neocolonial countries on more than 30 countries, affecting more than 2 billion people.

Taking up the theme of food security as a major solution to extreme poverty, speakers pointed to its promise and potential, while lamenting that the agriculture sector is underdeveloped, underfunded and beset by crises. The representative of Samoa, speaking on behalf of the Alliance of Small Island States, said the group considers agricultural development, food security and nutrition critical. Reversal of progress in this regard is therefore a source of concern for those States, requiring drastic action to invert the disturbing trend.

Niger’s representative said that the agricultural sector employs nearly 80 per cent of its working population and represents on average 40 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). However, despite the significant assets that Niger has — 19 million hectares of arable land — and the enormous efforts that have been made, “we face agricultural challenges” including lack of access to technology for producers and an underdeveloped agricultural transport sector.

Striking an optimistic note, the representative of the United Republic of Tanzania said his country aims to be a hub and basket of the African food supply. He cited a clear land-ownership policy, a 29 per cent increase in the budget for agriculture between 2022 and 2024, and subsidies in fertilizers and seeds. The country is piloting a youth programme to make agriculture more attractive, aiming to generate more than 10,000 enterprises in eight years.

A report was also presented by the Director of the Partnerships and United Nations Collaboration Division at FAO.

The Committee will meet again at 3 p.m. on Thursday, 12 October, to conclude its joint discussion of eradication of poverty and agriculture development, food security and nutrition, before taking up operational activities.

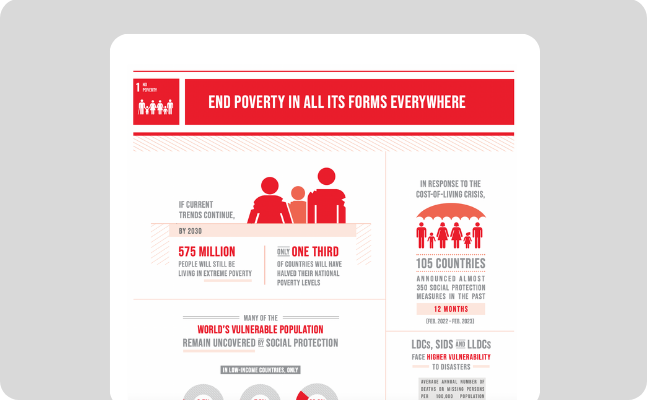

Introduction of Reports

JOHN WILMOTH, Officer-in-Charge of the Division for Inclusive Social Development of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs , introducing the report of the Secretary-General titled “Implementation of the Third United Nations Decade for the Eradication of Poverty (2018-2027)” (document A/78/239 ), said that the document provides a review of the progress made and the gaps and challenges in the context of ongoing global and mutually reinforcing crises. “It states that the disruptions caused by the pandemic in 2020 led to an increase in extreme poverty for the first time in more than two decades,” he said, spotlighting a compounding cost-of-living crisis and related inflationary shocks triggered by the war in Ukraine. “About 670 million people were estimated to be living in extreme poverty in 2022, an increase of 70 million people compared with pre-pandemic projections,” he stressed, adding that 1.1 billion out of 6.1 billion people in 110 countries surveyed are living in multidimensional poverty in 2023. “Projections show that almost 600 million people will still suffer from hunger in 2030,” he said, citing the report, which notes that the poorest countries spent billions on debt payments, preventing them from investing in sustainable development. The report makes recommendations on how to reach a rapid and sustainable recovery and end poverty for all, he concluded.

BENJAMIN DAVIS, Director of the Inclusive Rural Transformation and Gender Equality Division of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), presented reports of the Secretary-General titled “Eradicating rural poverty to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” (document A/78/238 ) and “Agriculture development, food security and nutrition” (documents A/78/218 , A/78/233 , A/78/74 ).

According to the report on eradicating rural poverty, more than 80 per cent of the world’s extreme poor live in rural areas. Poverty rates, in fact, are nearly three times higher among rural than among urban residents. The report notes that progress is being thwarted by the slow and uneven recovery from COVID‑19 and other crises, such as conflict, fluctuating commodity prices and extreme weather. While people living in rural poverty contribute the least to climate change, they are the most vulnerable to it, he said, and called for the implementation of inclusive, environmentally sustainable rural development strategies that put the eradication of rural poverty at the centre. Among other things, the report calls for increasing investments in social services and emphasizes the need to expand access to financial services.