An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BJPsych Bull

- v.44(5); 2020 Oct

Homelessness, housing instability and mental health: making the connections

Deborah k. padgett.

1 New York University

Associated Data

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit https://doi.org/10.1192/bjb.2020.49.

Research on the bi-directional relationship between mental health and homelessness is reviewed and extended to consider a broader global perspective, highlighting structural factors that contribute to housing instability and its mental ill health sequelae. Local, national and international initiatives to address housing and mental health include Housing First in Western countries and promising local programmes in India and Africa. Ways that psychiatrists and physicians can be agents of changes range from brief screening for housing stability to structural competence training. Narrow medico-scientific framing of these issues risks losing sight of the foundational importance of housing to mental health and well-being.

Mental illness and homelessness

The bi-directional relationship between mental ill health and homelessness has been the subject of countless reports and a few misperceptions. Foremost among the latter is the popular notion that mental illness accounts for much of the homelessness visible in American cities. To be sure, the failure of deinstitutionalisation, where psychiatric hospitals were emptied, beginning in the 1960s, led to far too many psychiatric patients being consigned to group homes, shelters and the streets. 1 However, epidemiological studies have consistently found that only about 25–30% of homeless persons have a severe mental illness such as schizophrenia. 2

At the same time, the deleterious effects of homelessness on mental health have been established by research going back decades. Early epidemiological studies, comparing homeless persons with their domiciled counterparts, found that depression and suicidal thoughts were far more prevalent, along with symptoms of trauma and substance misuse. 2 , 3 A recent meta-analysis found that more than half of homeless and marginally housed individuals had traumatic brain injuries – a rate far exceeding that of the general population. 4 Qualitative interviews with street homeless persons bring to life the daily struggles and emotional toll of exposure not only to the elements but to scorn and harassment from passers-by and the police. 5

In the USA, healthcare professionals were among the first responders to the homelessness ‘epidemic’ of the 1980s. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Care for the Homeless initiative funded 19 health clinics around the nation, beginning in 1985. Individual physicians, including Jim Withers in Pittsburgh and Jim O'Connell in Boston, made it their mission to go out on the streets rather than participating in the ‘institutional circuit’ 6 that led so many homeless men and women to cycle in and out of emergency departments, hospitals and jails. Health problems such as skin ulcerations, respiratory problems, and injuries were the visible indicia of what foretold a shortened lifespan. 7 Less visible but no less dire are the emotional sequelae of being unhoused – children are especially susceptible to the psychological effects of homelessness and housing instability. 8 The gap between mental health needs and service availability for the homeless population is vast.

The bigger picture: global housing instability and structural factors

Literal homelessness – sleeping rough in places unfit for human habitation – can be seen as the tip of an iceberg of housing insecurity affecting millions of people around the world. 9 As with attempts to count the number of homeless people and the definitional difficulties attending such counts, 10 providing an estimate of the number of housing-unstable persons globally is definitionally and logistically challenging. In terms of slum dwellers (a prevalent form of housing instability), Habitat for Humanity cites estimates ranging from 900 000 to 1.6 billion. 11 The Dharavi slum in Mumbai has one million residents squeezed into two square kilometres, one of the densest human settlements in the world. 11 Substandard housing affects the well-being of inhabitants – crowding, poor sanitation and infestations bring their own risks to health and mental health. 12

Severe housing shortages in low-income countries contrast with the greater availability of housing in higher-income countries. And yet the visibility and persistence of homelessness in wealthier nations attests to the effects of growing income inequities in the midst of plenty. In the USA, attempts to address homelessness must take several structural barriers into account. First, housing is fundamentally viewed as a commodity and is bound up with economic gains in the forms of tax benefits for homeowners and builders, equity or wealth accumulation from owning property, and developers’ profits from housing market speculation. 13 The worst ‘slumlords’ (landlords who own and rent decrepit properties to poor families) reap greater levels of profit than their counterparts who build for affluent buyers or renters. 14 Second, exclusionary zoning ordinances ensure protection of single-family properties, thus reducing housing availability for renters and preventing multi-family dwellings. 15 Finally, access to housing is not a purely economic proposition. The effects of centuries of de facto and de jure racial exclusion continue to uniquely harm African Americans in denying them access to housing and associated wealth accumulation, thus contributing to their disproportionate representation among homeless persons in the USA. 15

The ultimate causes of homelessness are upstream, i.e. a profound lack of affordable housing due in large part to neo-liberal government austerity policies that prevent or limit public funding for housing, gentrification that displaces working and poor families, and growing income disparities that make paying the rent beyond the means of millions of households. Currently, more than half of US households must devote over 50% of their income to paying for housing, an unprecedented level of rent burden. 14 Farmer refers to this phenomenon as ‘structural violence’: the combined and cumulative effects of entrenched socioeconomic inequities that give rise to varied forms of social suffering. 16 Social suffering does not easily align with existing psychiatric nomenclatures and diagnostic algorithms, but its influence on health through chronic stress and allostatic overload weakens immune systems and erodes emotional well-being. 17

International and national initiatives

Interestingly, since its 1948 declaration of a right to housing, 18 the United Nations (UN) has generally steered clear of re-enunciating such a right until the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were announced in 2015. Subsumed within SDG #11, labelled ‘sustainable cities and communities’, is Target 11.1 of ‘safe and affordable housing for all by 2030’. 19 The UN Special Rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, Leilani Farha, recently submitted a set of guidelines for achieving this goal. 20

In the global south, access to mental healthcare for the most vulnerable is extremely limited despite legislative initiatives to expand such care 21 , 22 and reduce human rights abuses against psychiatric patients. 23 The Global Mental Health Movement (GMHM), which began with a series of articles in the Lancet in 2007 asserting ‘no health without mental health’, 24 came together to address a crisis that results in a ‘monumental loss in human capabilities and avoidable suffering’. 21 The Lancet Commission on Global Mental Health and Sustainable Development, part of the GMHM, has strategically partnered with the UN's SDGs to ensure that mental health and substance misuse are integral to the SDGs moving forward. 21 And there are signs of progress – most originating in the work of citizen advocates and patients working through non-profit rather than formal government channels. In Chennai, India, a visionary non-profit known as The Banyan has pioneered a culturally and socially innovative approach, ‘Home Again’, to help homeless persons with severe mental illness recover their lives and live independently or return to their family homes. 25 In West Africa, advocates for AIDS and leprosy patients have turned their talents and expertise to developing programmes for persons with mental illness that are inclusive, rehabilitative and rights based. 23 Zimbabwe's ‘Friendship Bench’ programme, which situates attention to mental health within ongoing community activities, has been replicated worldwide. 26 Although the African approaches are not targeted at homeless persons, they have been heralded as low-barrier and inclusive – and by their location are likely to assist persons with housing insecurity problems among others. 21 The recent Lancet Commission report on global mental health 21 included mention of homelessness as both a cause and consequence of poor mental health.

The advent of Housing First has been a rare success story at the programmatic and systems levels in the US, Canada and Western Europe. 27 Begun in New York City as a small but determined counterpoint to ‘treatment first’ approaches making access to housing contingent on adherence, Housing First has achieved an impressive evidence base and extensive adaptations to new populations such as homeless youth, families and opioid users. 27 By reversing the usual care continuum of first requiring medication adherence, abstinence and proof of ‘housing worthiness’, Housing First is the prime exemplar of an evidence-based, cost-saving enactment of the right to housing. Importantly, it is not ‘housing only’, i.e. support services including mental healthcare are essential to its success. 28 Early reliance on assertive community treatment in Housing First support services was eventually expanded to include less-intensive case management supports for clients whose mental health recovery had proceeded further. 27

Another evidence-based programme known as critical time intervention (CTI) has proven effective in preventing homelessness pending discharge from institutional care. 29 Using time-sensitive intensive supports before and after discharge, CTI connects the patient or client with housing and support services to ease return to the community and avert falling into homelessness. 29 Like Housing First, CTI has focused on persons with mental disorders but has since been adapted for other at-risk groups, such as clients leaving substance misuse treatment settings or prisons.

In the USA, there are a few signs that housing as a social determinant of health is receiving greater recognition. The Obama-era Affordable Care Act offered states the opportunity to expand Medicaid eligibility to millions of low-income households, including coverage for mental healthcare. 30 Although federal rules prohibit use of Medicaid funds to pay for housing (with the exception of nursing homes), some states have creatively used Medicaid funds for all housing-related services short of rent, including move-in costs and follow-up supports. 30 Unfortunately, capital funding for building and developing new housing units remains woefully inadequate, and it is too often left up to the private sector to act on a profit motive incentivised by government subsidies and tax incentives. 15 Given the current national political situation in the US, positive change at the federal level is unlikely, but states and cities continue to independently seek ways to move from shelters to housing. 30

The healthcare landscape in the UK offers opportunities for service integration under coordinated national healthcare, and the link between housing and health is evident in recent cooperation between the National Housing Federation and the Mental Health Foundation in providing supported accommodation for persons with mental disorders. 31 In Western Europe, the establishment of FEANTSA (European Federation of National Organizations Working with the Homeless; www.feantsa.org ) in 1989 with support from the European Commission has brought together representatives from 30 nations for programmatic and research initiatives (many using Housing First). Consideration of mental problems as cause and consequence of homelessness is a key component of FEANTSA's work, with psychiatrists actively involved in research at several sites, e.g. France's multi-city randomised trial of Housing First. 32

Psychiatrists and physicians as agents of change

In what ways can healthcare providers help? For housing-related risk assessment, family or general care physicians may make use of brief screening items inquiring about recent moves, evictions and rent arrears 33 as a means of ascertaining a patient's housing instability. Regrettably, there are limited programmes available to which to refer patients with ‘positive’ screens, but raising awareness and knowing a patient's life challenges can only improve care. Calls for medical training to include ‘structural competency’ 34 point to the broader importance of practitioners becoming versed in patients’ life circumstances linked to poverty to contextualise their health problems. According to Metzl and Hansen, 34 structural competency is the practitioners’ trained ability to recognise that patients’ problems defined clinically as symptoms, attitudes or disease also represent the downstream implications of upstream decisions about housing affordability, healthcare availability, food delivery systems and other infrastructure supports.

Some physicians have called for the right to prescribe housing as a means of solving this underlying problem, with the added advantage of reducing medical costs. 35 Prescribing housing as a form of ‘preventive neuroscience’ has received support from the O'Neill Institute as a cost-saving humane investment in children's brain development. 36 Such attention to social and environmental determinants of health is hardly misplaced, as they account for 90% of health status, with only 10% attributable to medical care. 30

Homeless men and women have few encounters with physicians, much less psychiatrists and other formal mental healthcare providers. Those with diagnoses of severe mental illnesses might have an assigned psychiatrist to prescribe anti-psychotic medications, but these are brief encounters at best. Even in wealthier nations, psychiatrists working in the public sector are relatively fewer in number, overworked, underpaid and rarely able to address the hidden crisis of mental ill health wrought by homelessness and housing instability. In low-income nations, the service gap is even wider. 22

A recent US report on the alarming lack of access to mental healthcare even for the well insured points to a broad-based crisis in mental health services. 37 Ignoring laws ensuring parity, insurers provide much lower coverage for mental health treatment than would be tolerated for cardiac or cancer care, and out-of-pocket costs can run as high as $400 per private psychiatrist visit. 37 The prospects for a homeless man or woman who is feeling anxious, depressed or suicidal are indeed dismal. Although many homeless and other low-income individuals in the US are enrolled in Medicaid, an acute scarcity of psychiatrists who accept Medicaid patients renders such coverage virtually unattainable in many parts of the US. 37

A caveat about the medico-scientific approach moving forward

Attempts to incorporate social determinants thinking into public policy discourse on the mental health benefits of stable housing still have some way to go in jurisdictions where the medico-scientific approach holds sway. As a case in point, witness the recent report by the prestigious US National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) on the health benefits of permanent supportive housing (PSH), a major source of housing and supports for formerly homeless persons with severe mental illness. 38 Acknowledging that research on the topic was severely limited owing to the recency of PSH and its many poorly defined iterations, the NASEM report nevertheless concluded that the health benefits of such housing were minimal, with the possible exception of persons with HIV/AIDS having improved outcomes. 38 The report argued for the need to identify ‘housing-sensitive’ health conditions to point future researchers in the right direction. 38

Such delimiting of what is important to ‘housing-sensitive’ medical conditions exemplifies the narrowness of the medico-scientific model set against a social determinants model combined with human rights. In response to such reductionism, the British Psychological Society recently proposed the Power Threat Meaning Framework as an alternative to the medicalisation of mental illness, 39 proposing that greater attention be given to the implications of power and inequality.

Homelessness represents an existential crisis that threatens mind and body alike. The concept of ontological security, having its modern origins in the writings of sociologist Anthony Giddens, offers phenomenological insights into the benefits of stable housing that domiciled persons easily take for granted. As noted by this author, 40 going from the streets to a home enhances one's ontological security, as such a transition affords a sense of safety, constancy in everyday life, privacy, and a secure platform for identity development. 40 As with Maslow's hierarchy, 41 fundamental human needs must be met in order to satisfy higher-order needs such as belonging and self-actualisation.

Despite a plethora of research linking mental and physical health to housing stability, the salience of structural barriers is too often submerged in ‘blaming the victim’ for her or his plight. Physicians and healthcare providers receive little training in social determinants and often view them as off-limits or distracting from attention to signs and symptoms. Yet psychiatrists and other mental health professionals can become agents of change by paying greater attention to the social determinants of mental health and seeking structural competence in their practice. It is difficult to overestimate the benefits of having a stable, safe home as fundamental to mental health and well-being.

About the author

Deborah K. Padgett , PhD, MPH, is a Professor at the Silver School of Social Work at New York University (NYU). She is also an Affiliated Professor with NYU's Department of Anthropology and College of Global Public Health.

Declaration of interest

Supplementary material.

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

The prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis

Contributed equally to this work with: Stefan Gutwinski, Stefanie Schreiter

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Charité–Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Freie Universität Berlin and Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Berlin, Germany, Biomedical Innovation Academy, Berlin Institute of Health, Berlin, Germany

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

- Stefan Gutwinski,

- Stefanie Schreiter,

- Karl Deutscher,

- Seena Fazel

- Published: August 23, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Homelessness continues to be a pressing public health concern in many countries, and mental disorders in homeless persons contribute to their high rates of morbidity and mortality. Many primary studies have estimated prevalence rates for mental disorders in homeless individuals. We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies on the prevalence of any mental disorder and major psychiatric diagnoses in clearly defined homeless populations in any high-income country.

Methods and findings

We systematically searched for observational studies that estimated prevalence rates of mental disorders in samples of homeless individuals, using Medline, Embase, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar. We updated a previous systematic review and meta-analysis conducted in 2007, and searched until 1 April 2021. Studies were included if they sampled exclusively homeless persons, diagnosed mental disorders by standardized criteria using validated methods, provided point or up to 12-month prevalence rates, and were conducted in high-income countries. We identified 39 publications with a total of 8,049 participants. Study quality was assessed using the JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies and a risk of bias tool. Random effects meta-analyses of prevalence rates were conducted, and heterogeneity was assessed by meta-regression analyses. The mean prevalence of any current mental disorder was estimated at 76.2% (95% CI 64.0% to 86.6%). The most common diagnostic categories were alcohol use disorders, at 36.7% (95% CI 27.7% to 46.2%), and drug use disorders, at 21.7% (95% CI 13.1% to 31.7%), followed by schizophrenia spectrum disorders (12.4% [95% CI 9.5% to 15.7%]) and major depression (12.6% [95% CI 8.0% to 18.2%]). We found substantial heterogeneity in prevalence rates between studies, which was partially explained by sampling method, study location, and the sex distribution of participants. Limitations included lack of information on certain subpopulations (e.g., women and immigrants) and unmet healthcare needs.

Conclusions

Public health and policy interventions to improve the health of homeless persons should consider the pattern and extent of psychiatric morbidity. Our findings suggest that the burden of psychiatric morbidity in homeless persons is substantial, and should lead to regular reviews of how healthcare services assess, treat, and follow up homeless people. The high burden of substance use disorders and schizophrenia spectrum disorders need particular attention in service development. This systematic review and meta-analysis has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018085216).

Trial registration

PROSPERO CRD42018085216 .

Author summary

Why was this study done.

- Homelessness continues to affect a large number of people in high-income countries and is associated with an increased risk of mental disorders.

- To guide service development, further research, and public policy, reliable estimates on the prevalence of mental disorders among homeless individuals are needed.

- Many primary investigations into rates of mental disorders have been published since a previous comprehensive quantitative synthesis in 2008.

What did the researchers do and find?

- We performed a systematic database search, extracted data from primary reports, and assessed their risk of bias, resulting in a sample of 39 studies including information from over 8,000 homeless individuals in 11 countries.

- We conducted random effects meta-analyses of 7 common diagnostic categories. Prevalence estimates were all increased in homeless individuals compared with those in the general population. Alcohol use disorders had the highest absolute rate, at 37%, with substantially elevated proportional excesses compared to the general population for schizophrenia spectrum disorders and drug use disorders as well.

- There was substantial between-study variation in prevalence estimates, and meta-regression analyses found that sampling method, participant sex distribution, and study country explained some of the heterogeneity.

What do these findings mean?

- The high burden of substance use disorders and severe mental illness in homeless people represents a unique challenge to public health and policy.

- Future research should prioritize quantification of unmet healthcare needs, and how they can be identified and effectively treated. Research on subgroups, including younger people and immigrant populations, is a priority for prevalence work.

Citation: Gutwinski S, Schreiter S, Deutscher K, Fazel S (2021) The prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. PLoS Med 18(8): e1003750. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750

Academic Editor: Vikram Patel, Harvard Medical School, UNITED STATES

Received: February 2, 2021; Accepted: August 2, 2021; Published: August 23, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Gutwinski et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The Wellcome Trust ( https://wellcome.org ) granted the submission fee for this review to SF (grant number 202836/Z/16/Z). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DSM, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; PI, prediction interval

Introduction

Homelessness is recognized by the United Nations Economic and Social Council as an issue of global importance [ 1 ]. In high-income countries, around 2 million people have been homeless over the past decade [ 2 ]. In the US, the lifetime prevalence of homelessness is estimated at 4.2% [ 3 ], with around 550,000 individuals lacking fixed, regular, and adequate residence on any given night [ 4 ]. Patterns over time have differed by country, although homelessness has increased in many high-income countries in recent years, including in the US and UK since 2017 [ 2 ].

There has been an increasing recognition of the public health importance of homeless persons, with many studies reporting high rates of acute hospitalization, chronic diseases, and mortality [ 5 – 13 ]. Comorbidities increase these risks, particularly mental disorder comorbidities. For example, in a Danish population study, comorbidity of psychiatric disorders increased mortality rates by 70% [ 14 ]. Furthermore, mental illness among homeless individuals has been associated with elevated rates of criminal behavior and victimization [ 15 , 16 ], prolonged courses of homelessness [ 17 , 18 ], and perceived discrimination [ 19 ]. Mental disorders among homeless individuals are mostly treatable and represent an important opportunity to address health inequalities.

Information on the overall extent and pattern of mental disorders among homeless people is necessary to inform resource allocation and service development, and to allow researchers, clinicians, and policymakers to consider evidence gaps. The large number of primary studies, of varying quality and samples, means that systematic reviews are required to clarify and synthesize the evidence, underscore main findings, and consider implications. According to a recent umbrella review, there have been at least 7 systematic reviews with quantitative data synthesis in the past 2 decades [ 20 ]; however, most of them focused on individual diagnostic categories [ 21 – 24 ], examined specific age bands [ 24 , 25 ], or were limited to a single country [ 26 ]. The last meta-analysis to our knowledge that provided a comprehensive account of the prevalence of major mental disorders in homeless adults in high-income countries completed its search in 2007 [ 27 ], and since then, a considerable number of primary studies have been published [ 28 , 29 ]. Thus, we conducted an updated systematic review and meta-analysis on the prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries, and added the diagnostic categories of any mental disorder and bipolar disorder.

Search strategy

We searched for studies that determined prevalence rates for at least 1 of the following disorders among homeless persons: (1) schizophrenia spectrum disorders, (2) major depressive disorder, (3) bipolar disorder, (4) alcohol use disorders, (5) drug use disorders, (6) personality disorders, and (7) any current mental disorder (Axis I disorders in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders [DSM] multiaxial system [ 30 ]).

We have updated an earlier review [ 27 ] that was based on a search for articles published up until December 2007, so we targeted new primary studies published between 1 January 2008 and 1 April 2021. We searched Embase via OvidSP, Medline via OvidSP and via PubMed, and PsycInfo via EBSCOhost. Additionally, we searched Google Scholar using a search query and screened all literature citing the previous review. Finally, we screened reference lists of relevant publications. Each search employed a specific combination of search terms designed to fit the databases’ respective syntaxes and thesaurus systems ( S1 Table ). Articles written in languages other than English or German were translated by professional translators. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis has been published (PROSPERO CRD42018085216). We followed Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines for extracting and assessing data [ 31 ]. This systematic review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (see S2 Table ) [ 32 ].

Eligibility criteria and study selection

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) homelessness status of study participants was validated by an operationalized definition or a sampling method that specifically targeted homeless population; (2) standardized criteria for the psychiatric disorders specified above, based on the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or DSM, were applied; (3) psychiatric diagnoses were made by clinical examination or interviews using validated semi-structured diagnostic instruments; (4) for any psychiatric disorders except for personality disorders (where lifetime rates were used), prevalence rates were reported within 12 months; and (5) study location was a high-income country according to the classification of the World Bank [ 33 ].

Surveys that reported a response rate of less than 50% or exclusively sampled from selected subpopulations (such as elderly homeless, homeless youth, or homeless single parents) were excluded.

In order to assess all results from the bibliographic search process, researchers SS, SG, and KD each carried out a multilevel screening process independently from one another. Any differences between results were resolved by consensus between all the authors.

Data collection and quality assessment

Information from included surveys was extracted on study location, year of diagnostic assessment, operational definition of homelessness status, sampling method, diagnostic procedures, diagnostic criteria, professional qualification of interviewers, response rate, dropout rate, number of participants by sex, sample mean age, current accommodation of participants, sample mean duration of homelessness, and number of participants diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, alcohol- and drug-related disorders, personality disorders, and any primary diagnosis of a mental disorder apart from personality and developmental disorders (i.e., Axis I disorders in DSM). If data regarding any of these categories were unclear in the published study, we corresponded with the primary study authors.

Each included publication was rated on methodological quality by 2 sets of criteria specifically designed to assess prevalence studies: the JBI critical appraisal tool for prevalence studies [ 34 ] and a risk of bias tool [ 35 ]. This process was carried out by SS, SG, and KD independently, and any differences were resolved by discussion.

Statistical analysis

Random effects meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses were performed on each diagnostic category independently—prevalence data for alcohol misuse/abuse and alcohol dependence were both entered into the single category of alcohol use disorders, in accordance with current diagnostic approaches. All analyses were done in R, version 4.0.4 [ 36 ]. The package “metafor,” version 2.4–0, was utilized for meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis, supplemented by “glmulti,” version 1.0.8, for multivariable model selection and “mice”, version 3.13.0, for multivariate imputation [ 37 – 39 ].

Prevalence estimates were transformed on the double arcsine function in order to avoid variance instability and confidence intervals (CIs) exceeding the interval (0 ≤ x ≤ 1) in which prevalence proportions can be meaningfully defined [ 40 ]. We calculated random effects models, which we deemed appropriate considering sampling differences. The Paule–Mandel estimator was chosen to measure between-study variance due to its reliability for different types of models [ 41 ]. A Q- test for heterogeneity was conducted. To quantify measures of between-study heterogeneity, we report the test statistic Q E and corresponding p- value as well as the I 2 statistic. Additionally, we calculated 95% prediction intervals (PIs) for all meta-analytical models [ 42 ]. Because the “metafor::predict.rma” function unrealistically assumed that the model variance τ 2 was a known value [ 43 ], we instead implemented a method proposed by Higgins and colleagues that accounts for τ 2 being an estimate with limited precision ([ 44 ], expression 12).

Additional meta-analyses were carried out in each diagnostic category for low-risk-of-bias studies, assigned during quality assessment [ 35 ]. Subgroup analyses comparing low-risk-of-bias and moderate-risk-of-bias studies were performed through a Q- test. In cases of significant between-subgroup difference, a meta-regression model with risk of bias assessment as a single independent variable was computed to estimate the proportion of variance explained by disparities in methodological quality.

For each diagnostic category, meta-regression analyses were performed to investigate potential sources of heterogeneity. Continuous independent variables for single factor meta-regression were number of participants, sex distribution (female/all), and final year of diagnostic assessments. Categorial independent factors were diagnostic method (structured/semi-structured interview versus non-structured clinical evaluation), sampling method (randomized versus non-randomized sampling methods), and study location (US, UK, or Germany). The 3 study locations were prespecified as predictor variables due to a preponderance of primary studies in each of these countries.

Multivariable meta-regression models were also calculated. The respective independent variables were chosen through automated, information-criterion-based model selection with generalized linear models [ 38 ]. For models with 20 or more included studies, the Akaike information criterion (AIC) was used; for models with fewer than 20 included studies, we utilized the corrected version for small sample sizes (AIC C ) to avoid over-fitting.

The proportion of variance of prevalence estimates explained by any meta-regression model was estimated by the R 2 statistic [ 45 ].

We assumed that missingness was at random [ 46 ], so missing values in independent variables (that were missing despite requests for additional information to primary study authors) were replaced through multiple imputation by chained equations [ 47 ]. For models including incomplete predictor variables, results of meta-regression on imputed data are presented as the primary analysis; meta-regression results on only complete cases are provided as sensitivity analyses [ 48 ].

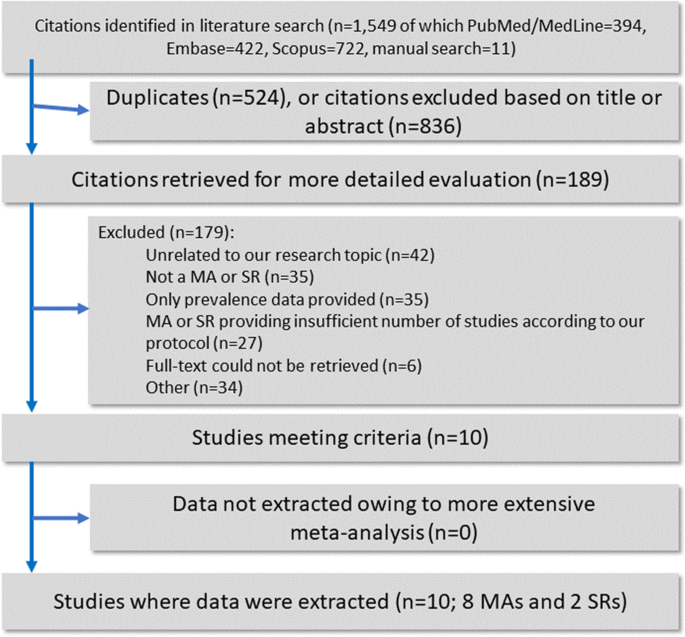

Description of included studies

The systematic literature search returned 5,886 distinct records, of which 144 full texts were assessed (see S3 Table for reasons for exclusion). We identified a total of 39 studies comprising data on 8,049 homeless individuals [ 28 , 29 , 49 – 85 ] (see Fig 1 for flow chart of screening process). This included 10 additional studies for this update [ 28 , 29 , 53 – 55 , 57 , 59 , 62 , 75 , 76 ], and 2 previous investigations were further clarified [ 81 , 83 ].

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g001

Out of the 39 included studies, 27 publications reported age (mean of 41.1 years) [ 28 , 49 – 57 , 59 , 64 , 65 , 67 , 70 – 73 , 75 , 76 , 78 – 82 , 84 , 85 ], and the proportion of women was 22.3% (based on 38 studies) [ 28 , 29 , 49 – 65 , 67 – 85 ]. Eleven studies [ 52 , 56 , 68 , 71 – 74 , 80 , 82 , 83 , 85 ] investigated male-only samples, and 5 studies [ 59 , 65 , 78 , 81 , 84 ] solely women. Of the 39 studies, 27 were from 3 countries: 11 from the US ( n = 2,694 participants) [ 57 , 59 , 60 , 64 , 69 , 75 , 77 , 79 , 83 – 85 ], 7 from the UK ( n = 1,390 participants) [ 49 , 61 , 66 , 67 , 70 , 78 , 82 ], and 9 from Germany ( n = 936 participants) [ 28 , 50 , 51 , 56 , 65 , 71 – 73 , 80 , 81 ]. Six studies were from other European countries ( n = 2,301 participants) [ 29 , 52 , 55 , 58 , 62 , 76 ], 1 study was from Canada ( n = 60 participants) [ 69 ], 2 were from Japan ( n = 194 participants) [ 53 , 54 ], and 2 were from Australia ( n = 667 participants) [ 63 , 74 ]. Fourteen studies reported a response rate of 85% or above [ 49 , 60 , 65 , 66 , 69 – 73 , 78 , 81 , 82 , 84 , 85 ], 20 studies reported a response rate below 85% [ 28 , 29 , 50 – 52 , 54 – 56 , 58 , 59 , 61 – 64 , 68 , 74 , 76 , 79 , 80 , 83 ], and 5 did not report participation rate [ 53 , 57 , 67 , 75 , 77 ]. In 13 studies, participants were accommodated in shelters, hostels, or residential care when assessed [ 28 , 49 , 63 , 66 , 70 , 72 , 74 , 76 – 78 , 81 – 83 ] while in 3 they were rough sleeping [ 54 , 62 , 67 ]; 22 studies had mixed samples regarding accommodation or provided incomplete information [ 29 , 50 – 53 , 55 – 61 , 64 , 65 , 68 , 69 , 71 , 73 , 75 , 79 , 80 , 84 , 85 ]. S4 Table provides further information on methodological and sample characteristics. For quality ratings, see S5 and S6 Tables. S7 Table provides all extracted data that meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses were based on.

Any current mental disorders

There were 8 surveys reporting on homeless people having at least 1 diagnosis of a current mental disorder [ 28 , 51 , 54 , 62 , 71 – 73 , 81 ], with a random effects pooled prevalence estimated at 76.2% (95% CI 64.0% to 86.6%) ( Fig 2 ). Individual study prevalence rates ranged from 56.3% to 93.3%, with substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 88% [95% CI 72% to 97%]). The 95% PI was 40% to 99%. Univariable meta-regression analysis revealed that studies with randomized sampling procedures reported significantly higher prevalence estimates than ones with other sampling procedures, accounting for a large proportion of heterogeneity ( R 2 = 59%) (see S8 Table ). Sampling procedure was chosen as the only predictor variable by multivariable model selection (see Table 1 ).

Analytic weights are from random effects meta-analysis. Grey boxes represent study estimates; their size is proportional to the respective analytical weight. Lines through the boxes represent the 95% CIs around the study estimates. The blue diamond represents the mean estimate and its 95% CI. The vertical red dashed line indicates the mean estimate. CI, confidence interval; PI, prediction interval.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g002

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.t001

In a subgroup analysis of 4 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 62 , 71 , 73 , 81 ], the random effects prevalence was 75.3% (95% CI 50.2% to 93.6%; I 2 = 81% [95% CI 32% to 99%]). There was no significant difference between quality subgroups ( Q = 0.03, p = 0.87).

Schizophrenia spectrum disorders

There were 35 surveys reporting on any schizophrenia spectrum disorder [ 28 , 29 , 49 , 51 – 58 , 60 – 74 , 76 – 78 , 80 – 85 ], and the random effects prevalence was 12.4% (95% CI 9.5% to 15.7%) ( Fig 3 ), with substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 93% [95% CI 89% to 96%]; 95% PI 0% to 34%). Primary investigation estimates ranged between 2.0% and 42.2%. No single model coefficient in univariable meta-regression was statistically significant. A multivariable model with sample size, proportion of female participants, and study location in Germany accounted for a small share of the heterogeneity ( R 2 = 16%). The latter model indicated that studies with smaller samples had significantly higher prevalence rates, but only when based on imputed values (see Table 1 ).

Analytic weights are from random effects meta-analysis. Grey boxes represent study estimates; their size is proportional to the respective analytical weight. Lines through the boxes represent the 95% CIs around the study estimates. The blue diamond represents the mean estimate and its 95% CI. The vertical red dashed line indicates the mean estimate. CI, confidence interval; PI, prediction interval; RE, random effects.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g003

A subgroup analysis of 17 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 29 , 49 , 52 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 67 , 69 , 71 , 73 , 78 , 80 , 81 , 84 , 85 ] revealed a random effects pooled prevalence of 10.5% (95% CI 6.2% to 15.7%; I 2 = 94% [95% CI 88% to 98%]). The subgroup difference between low-risk-of-bias and moderate-risk-of-bias studies was non-significant, with the low-risk group resulting in a marginally lower weighted mean ( Q = 1.59, p = 0.21).

Major depression

We identified 18 studies reporting prevalence estimates on major depressive disorder [ 28 , 49 , 52 , 55 , 57 – 60 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 67 , 71 , 77 , 80 , 81 , 84 , 85 ], with a random effects pooled prevalence of 12.6% (95% CI 7.9% to 18.2%) ( Fig 4 ). Individual study estimates ranged between 0% and 40.6% and showed substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 95% [95% CI 90% to 98%]; 95% PI 0% to 40%). Univariable meta-regression analysis produced no significant models (see S8 Table ). For multivariable regression, independent variable sampling procedure and proportion of female participants were selected; the model indicated that studies with randomized sampling reported significantly higher prevalence rates (see Table 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g004

In a subgroup analysis of 13 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 49 , 52 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 67 , 71 , 80 , 81 , 84 , 85 ], the random effects pooled prevalence was 13.0% (95% CI 6.7% to 20.9%; I 2 = 96% [95% CI 90% to 99%]). There were no significant differences in between risk of bias subgroups ( Q = 0.09, p = 0.76).

Bipolar disorder

Fourteen surveys with prevalence estimates on bipolar disorder were identified [ 28 , 49 , 55 , 57 – 59 , 62 , 63 , 65 , 67 , 71 , 77 , 84 , 85 ]. Three studies reported on solely type I bipolar disorder [ 49 , 57 , 85 ], 4 examined all bipolar disorder subtypes [ 28 , 59 , 65 , 71 ], and 7 did not specify [ 55 , 58 , 62 , 63 , 67 , 77 , 84 ]. The random effects pooled prevalence was 4.1% (95% CI 2.0% to 6.7%) ( Fig 5 ), with substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 89% [95% CI 77% to 96%]; 95% PI 0% to 16%). Individual estimates ranged from 1.0% to 13.5%. Univariable regression models indicated that studies with higher proportions of female participants reported significantly higher rates of bipolar disorder (see S8 Table ). In the multivariable model, prevalence estimates from studies with randomized sampling were significantly lower than those from studies with other sampling methods (see Table 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g005

A subgroup analysis of 9 low-risk-of-bias surveys [ 49 , 55 , 58 , 62 , 65 , 67 , 71 , 84 , 85 ] resulted in a random effects pooled prevalence of 2.6% (95% CI 1.0% to 4.9%), with moderate heterogeneity ( I 2 = 78% [95% CI 29% to 96%]). The difference between low-risk-of-bias and moderate-risk-of-bias studies was non-significant ( Q = 2.29, p = 0.13).

Findings for any affective disorder (which included depression and bipolar disorder) are reported in S1 Text and S6 Table .

Alcohol use disorders

Estimates on alcohol use disorders could be extracted from 29 surveys [ 28 , 29 , 51 – 66 , 68 , 71 – 73 , 76 , 77 , 79 – 81 , 84 , 85 ]. The random effects pooled prevalence was 36.7% (95% CI 27.7% to 46.2%) ( Fig 6 ), with individual study estimates ranging from 5.5% to 71.7%, and with substantial between-study heterogeneity ( I 2 = 98% [95% CI 97% to 99%]; 95% PI 2% to 85%). Univariable meta-regression models indicated that studies with smaller samples and studies from Germany (compared to other locations) reported significantly higher rates of alcohol use disorders (see S8 Table ). In multivariable analysis, the best selected model included only study location as a predictor variable, with higher prevalences reported in Germany and North America (see Table 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g006

In a subgroup analysis of 14 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 29 , 52 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 71 , 73 , 79 – 81 , 84 , 85 ], the random effects pooled prevalence was 36.9% (95% CI 21.1% to 54.3%; I 2 = 99% [95% CI 98% to 100%]). There was no significant difference between risk of bias subgroups ( Q < 0.01, p = 0.96).

Drug use disorders

We identified 23 surveys reporting prevalence estimates on drug use disorders [ 28 , 29 , 52 , 53 , 55 – 65 , 71 , 73 , 76 , 79 , 80 , 82 , 84 , 85 ] ( Fig 7 ). A random effects pooled prevalence of 21.7% (95% CI 13.1% to 31.7%) was found, with very high heterogeneity ( I 2 = 99% [95% CI 98% to 99%]; 95% PI 0% to 74%); individual estimates ranged between 0% and 72.1%. According to univariable meta-regression, studies with randomized sampling (as opposed to other sampling methods) estimated significantly lower prevalence rates (see S8 Table ). The selected multivariable model showed that studies from the UK reported lower prevalence rates. These results were confirmed by a secondary complete case analysis.

Analytic weights are from random effects meta-analysis. Grey boxes represent study estimates; their size is proportional to the respective analytical weight. Lines through the boxes represent the 95% CIs around the study estimates. The blue diamond represents the mean estimate and its 95% CI. The vertical red dashed line indicates the mean estimate. CI, confidence interval; PI, prediction interval; RE: random effects.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g007

A subgroup analysis of 13 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 29 , 52 , 55 , 58 , 60 , 62 , 65 , 71 , 73 , 79 , 80 , 84 , 85 ] resulted in a random effects pooled prevalence of 18.1% (95% CI 10.5% to 27.2%), with substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 97% [95% CI 94% to 99%]). The difference between subgroups was not significant ( Q = 0.65, p = 0.42).

Personality disorders

Fourteen studies reported prevalence estimates on lifetime personality disorders [ 28 , 51 – 53 , 62 , 64 , 67 , 75 – 77 , 80 , 82 , 84 , 85 ], with a random effects pooled prevalence of 25.4% (95% CI 10.9% to 43.6%) ( Fig 8 ). Individual estimates ranged between 0% and 98.3%, resulting in substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 99% [95% CI 97% to 99%]; 95% PI 0% to 91%). Univariable regression models did not yield significant results (see S8 Table ), and neither did the selected multivariable model (see Table 1 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.g008

In a subgroup analysis of 6 low-risk-of-bias studies [ 52 , 62 , 67 , 80 , 84 , 85 ], the random effects pooled prevalence was 21.0% (95% CI 4.7% to 44.5%), with substantial heterogeneity ( I 2 = 97% [95% CI 92% to 100%]). The difference between subgroups was not significant ( Q = 0.32, p = 0.57).

This systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of mental illness among homeless people in high-income countries included 39 studies comprising a total of 8,049 participants. We investigated 7 common psychiatric diagnoses, and examined possible explanations for the between-study heterogeneity. We report 3 main findings.

With a pooled prevalence of around 37%, alcohol-related disorders were the most prevalent diagnostic category. This prevalence estimate is around 10-fold greater than general population estimates: An EU study reported a 12-month prevalence of 3.4% in the general population [ 86 ]. Correspondingly, drug-related disorders were the second most common current mental disorder, with a pooled prevalence of 22% (which can be compared with the 12-month prevalence in the US general population of 2.5% [ 87 ]). We found substantial variation between the individual studies contributing to these estimates, with individual study estimates ranging from 5.5% to 71.7% for alcohol-related disorders; this variation was partially accounted for by study location. Particularly, German-based samples typically had higher prevalence rates of alcohol use disorders than those from other nations. This might highlight geographical differences regarding the affordability and availability of substances, including a comparatively low alcohol tax in Germany [ 88 ]. Irrespective of this moderating factor, the strong association between homelessness and substance abuse reflects a bidirectional relationship: Alcohol and drug use represent possible coping strategies in marginalized housing situations. At the same time, substance abuse and other psychiatric disorders precede the onset of homelessness in many people, with alcohol use disorders in particular emerging at an earlier point in life compared to age-matched non-homeless comparisons [ 89 ], suggesting that substance use might contribute to the deterioration of an individual’s housing situation. Such deterioration is consistent with the links between substance use disorders and excess mortality in homeless people [ 11 ], homelessness chronicity, psychosocial problems [ 90 ], and poorer long-term housing stability [ 91 ].

A second main finding was that some study characteristics consistently explained the variations in prevalence. In 5 diagnostic groups, methods were important, specifically the number of included participants and the sampling procedure. Unexpectedly, the latter had differential effects by diagnostic group. In bipolar disorder and drug use disorders, randomization was associated with lower prevalence estimates, whereas for any current mental disorder and major depression, it was associated with higher estimates. These findings underline the importance of standardized methodological procedures for homelessness research. We recommend that new research studies should base their inclusion criteria on a standardized definition of homelessness based on ETHOS criteria [ 92 ] and use randomized sampling, standardized diagnostic instruments, and trained interviewers with clinical backgrounds (including nurses, psychologists, and medical doctors).

Our third main finding was high prevalence rates for treatable mental illnesses, with 1 in 8 homeless individuals having either major depression (12.6%) or schizophrenia spectrum disorders (12.4%). This represents a high rate of schizophrenia spectrum disorders among homeless people, and a very large excess compared to the 12-month prevalence in the general population, which for schizophrenia is estimated around 0.7% in high-income countries [ 86 ]. For major depression, the difference from the general population is not marked, as the 12-month prevalence in the US general population is estimated at 10% [ 93 ], although comparisons would need to account for the differences in age and sex structure between the samples contributing to this review and the general population. Depression remains important because it is modifiable, and because of its effects on adverse outcomes. In addition, a recent cohort study based in Vancouver, Canada, found that substance use disorders were associated with worsening of psychosis in homeless people, underscoring the links between these mental disorders, and the importance of treatment in mitigating their effects directly and indirectly [ 13 ]. This study also found elevated risks of mortality in those with psychosis and alcohol use disorders [ 13 ].

Overall, our findings underscore the importance of mental health problems among homeless individuals. This review is complemented by other research on the often precarious financial and housing situation of psychiatric patients, for whom high rates of homelessness, indebtedness, and lack of bank account ownership have been reported [ 94 – 97 ]. Being homeless and having mental disorders are therefore closely interrelated. Fragmented and siloed services will therefore be typically unable to address these linked psychosocial and health problems. The mental disorders reported in this study are typically associated with unmet needs in the homeless population [ 51 , 98 – 100 ], which further indicates the need for integrated approaches. Many different initiatives to address these needs have been researched over the last decade, among them Housing First, Intensive Case Management, Assertive Community Treatment, and Critical Time Intervention. Randomized controlled studies using these approaches have generally resulted in positive effects on housing stability, but only moderate or no effects on most indicators of mental health in comparison to usual care, including for substance use [ 101 – 104 ]. Therefore, further improvements in management and treatment are necessary that focus on these common mental disorders.

The COVID-19 pandemic has put homeless people at particular risk of infection and further marginalization [ 105 ]. But it has shown what is possible—government agencies and charity organizations managed to quickly provide accommodation to a large number of rough-sleeping homeless people in some European regions [ 106 , 107 ].

Some limitations to this review need to be considered. We searched a limited number of databases, so it is possible that we missed certain primary reports, although this possibility was minimized by searching through reference lists and Google Scholar citations. Furthermore, despite the high rate of multimorbidity in homeless populations [ 108 , 109 ], included studies lacked information on comorbidity. With most of the primary studies reporting prevalence rates of more than 1 of the investigated diagnostic categories, effects from the same sample were in many cases entered into multiple meta-analytical models. This may have led to measurement error and overestimation if diagnostic criteria overlap, but without diagnostic validity studies specific to homeless persons, this remains uncertain. We limited the number of demographic variables that we conducted heterogeneity analyses on, because of variations in measurement and reporting detail. Future work, including individual participant meta-analysis, could standardize information on age, socioeconomic background, and ethnicity, for example.

The present review focuses on high-income countries because sample and diagnostic heterogeneity would presumably increase if a wider range of countries was included. It is important to note, however, that homeless populations in low- and middle-income countries need investigation, and may have higher rates of trauma-related symptoms [ 110 , 111 ]. The prevalence of the mental disorders reported in the current review does not consider unmet healthcare needs or treatment provision, which are additional elements to consider in developing services. Finally, several subpopulations were underrepresented: migrants and refugees (individuals who did not speak the local language were excluded from some study samples), the “hidden homeless” population (e.g., “couch-surfers”) [ 112 ] (sampling procedures were often not able to identify this group), and, importantly, homeless women. Twenty-two percent of participants in the included studies were female, lower than most estimates of the proportion of women among homeless populations, which range between 25% and 40% [ 4 , 113 ].

In summary, we found high prevalence of mental disorders among homeless people in high-income countries, with around three-quarters having any mental disorder and a third having alcohol use disorders. Future research should focus on integrated service models addressing the identified needs of substance use disorders, schizophrenia spectrum disorders, and depression in homeless individuals as a priority. In addition, new work could consider focusing on underrepresented subpopulations like homeless women and migrants. Furthermore, longitudinal studies could examine mechanisms linking homelessness and mental disorders in order to develop more effective preventive measures.

Supporting information

S1 table. database search strings..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s001

S2 Table. PRISMA 2009 checklist.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s002

S3 Table. Studies excluded at full-text screening, with reasons.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s003

S4 Table. Study characteristics.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s004

S5 Table. JBI checklist for prevalence studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s005

S6 Table. Risk of bias tool.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s006

S7 Table. Data basis for meta-analyses and meta-regression analyses.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s007

S8 Table. Univariable regression models.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s008

S9 Table. Results of single factor meta-regression models for affective disorders (pooled).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s009

S10 Table. Results of multiple factor meta-regression for affective disorders (pooled).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s010

S1 Text. Affective disorders.

Results of meta-analysis and meta-regression analysis.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1003750.s011

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to authors of included and non-included publications who provided additional details about their studies: C. Adams, H.-J. Salize, A. Greifenhagen, C. Vazquez, U. Beijer, C. Siegel, and G. Gilchrist. We are also grateful to the professional translator N. Spennemann for assistance with Japanese studies.

- 1. United Nations Commission for Social Development. Affordable housing and social protection systems for all to address homelessness. Report of the Secretary-General. E/CN.5/2020/3. New York: United Nations Commission for Social Development; 2019 Nov 27 [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: https://undocs.org/en/E/CN.5/2020/3 .

- 2. Directorate of Employment, Labour and Social Affairs. HC3.1 Homeless population. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; 2020 [cited 2020 May 3]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/family/HC3-1-Homeless-population.pdf .

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 4. Henry M, Mahathey A, Morrill T, Robinson A, Shivji A, Watt R. The 2018 Annual Homeless Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress. Part 1: point-in-time estimates of homelessness. Washington (DC): US Department of Housing and Urban Development; 2018 Dec [cited 2020 May 10]. Available from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2018-AHAR-Part-1.pdf .

- 28. Bäuml J, Brönner M, Baur B, Pitschel-Walz GG, Jahn T, Bäuml J. Die SEEWOLF-Studie: seelische Erkrankungsrate in den Einrichtungen der Wohnungslosenhilfe im Großraum München. Archiv für Wissenschaft und Praxis der sozialen Arbeit. Freiburg im Breisgau: Lambertus-Verlag; 2017.

- 33. World Bank. World Bank country and lending groups. Washington (DC): World Bank; 2020 [cited 2020 Sep 11]. Available from: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups .

- 34. JBI. Critical appraisal tools. Adelaide: University of Adelaide; 2021 [cited 2021 Aug 12]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools .

- 43. Viechtbauer W. Package ‘metafor.’ Version 2.4–0. Comprehensive R Archive Network; 2020 [cited 2021 Apr 21]. Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/metafor/metafor.pdf .

- 106. Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, Jenrick R. 6,000 new supported homes as part of landmark commitment to end rough sleeping. London: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government; 2020 May 24 [cited 2021 Jan 1]. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/6-000-new-supported-homes-as-part-of-landmark-commitment-to-end-rough-sleeping .

- 107. Deutsche Welle. Berlin opens first hostel for the homeless amid coronavirus pandemic. Deutsche Welle. 2020 Mar 31 [cited 2021 Jan 2]. Available from: https://www.dw.com/en/berlin-opens-first-hostel-for-the-homeless-amid-coronavirus-pandemic/a-52972263 .

- 113. Neupert P. Statistikbericht 2017. Berlin: Bundesarbeitsgemeinschaft Wohnungslosenhilfe. 2018 [cited 2020 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.bagw.de/fileadmin/bagw/media/Doc/STA/STA_Statistikbericht_2017.pdf .

The Complex Link Between Homelessness and Mental Health

Many americans are at heightened risk of homelessness due to the pandemic..

Posted May 21, 2021 | Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

- An estimated 20 to 25 percent of the U.S. homeless population suffers from severe mental illness, compared to 6 percent of the general public.

- The combination of mental illness, substance abuse, and poor physical health makes it difficult to maintain employment and residential stability.

- Better mental health services would combat not only mental illness but homelessness as well.

This post was written by Lenni Marcus, Cameron Johnson, and Danna Ramirez.

For many Americans, the prospect of losing their homes and falling into uncertain housing situations became excruciatingly prescient during the economic downturn caused by the impact of the coronavirus outbreak. A 2019 study suggested that even at that time, 40 percent of Americans were already one missed paycheck away from poverty.

And though governmental policies have temporarily slowed or halted evictions in many places, many individuals and families are still at risk of homelessness, or have already fallen through the cracks. Few are on a path to financial recovery and the profound aftershocks of this crisis will be felt far beyond the upcoming months and may impact families and their mental health for years to come.

Many homeless people share similar experiences, but a substantial subgroup of the homeless population struggle with severe mental illness as well. Yet the resilience of this group is often understated. Some just need help accessing resources, including mental health services, to reach a stable housing and financial situation. To understand how to better provide resources to break the cycle of homelessness, it is important to understand the many factors that may contribute to their impoverished state.

Homelessness and Mental Health

The idea that mental illness alone causes homelessness is naive and inaccurate, for two major reasons. First, the overwhelming majority of those living with mental illness are not homeless (and studies have failed to demonstrate a causal relationship between the two).

These types of distortions can have dangerous implications, wrongly focusing the attention on the individual rather than on the institutions that perpetuate housing insecurity. As a result, the illusory division between the “mentally ill homeless” and the “non-mentally ill homeless” casts the former as more deserving of intervention and services and the latter as seemingly “unworthy” or “undeserving” of support.

Though there is no causal relationship between mental illness and homelessness, those who suffer from housing insecurity are struggling significantly, both psychologically and emotionally. The constellation of economics, subsistence living, family breakdown, psychological deprivation, and impoverished self-esteem all contribute to the downward cycle of poverty.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), in 2010, 26.2 percent of all sheltered persons who were homeless had a severe mental illness, and 34.7 percent of all sheltered adults who were homeless had chronic substance use issues. Of those who experience chronic/long-term homelessness, approximately 30 percent have mental health conditions and 50 percent have co-occurring substance use problems. Also, they typically endure traumatic experiences that could potentially lead to mental health struggles, and certain environmental factors may increase the likelihood that they encounter future traumas.

Over 92 percent of mothers who are homeless have experienced severe physical and/or sexual abuse during their lifetime, and about two-thirds of homeless mothers have histories of domestic violence . Mothers who are homeless have three times the rate of PTSD and twice the rate of drug and alcohol dependence of their low-income housed counterparts. Left untreated, these stressors can further damage their mental health, potentially triggering maladaptive coping and putting them at risk for future traumatic events.

Breaking the Cycle of Homelessness

Homelessness is a social problem with complex and multifactorial origins. It underlies economic , social , and biographical risk factors such as poverty, lack of affordable housing, community and family breakdown, childhood adversity, neglect, and lack of social support, to name a few. These factors contribute to the onset, duration, frequency, and type of homelessness amongst individuals of all ages.

About 3 percent of Americans experience at least one episode of homelessness throughout their lives. Many enter an unbreakable cycle of homeless living due to the lack of access to adequate resources.

There are many components involved in the healthy exit of homelessness, with two of the most important being housing and social support . Meaningful and sustainable employment is fundamental to creating and maintaining housing stability. At the same time, individuals experiencing homelessness face many barriers to finding and maintaining employment . Most organizations that provide brief employment interventions assist individuals with only their most immediate employment needs (e.g., resume preparing); frequently these have little or no beneficial effects.

More intensive interventions that include an educational and/or training component are effective for those who participate regularly. Connecting people experiencing homelessness with job training and placement programs provides them with the necessary tools for long-term stability and success.

Access to housing and effective employment programs alone do not address other issues, such as loneliness , social exclusion, or any psychological problems that might have emerged. Promoting social connections as part of the transition out of homelessness plays a major role in improving outcomes.

Social support is a multidimensional concept that is measured by the size of a social network , received social support, and perceived social support. Received and perceived social support can each consist of different components: emotional support (the expression of positive affect and empathetic understanding), financial support (the provision of financial advice or aid), and instrumental support (tangible, material, or behavioral assistance). Therefore, programs providing training in job and life skills should also address how to navigate through social networking and how to maintain healthy social relations.

Breaking the cycle of homelessness requires institutions and policymakers to focus their efforts on multifaceted programs that are as complex as the social problem itself.

About the Authors

Lenni Marcus is a former social worker at the Compass program for young adults at The Menninger Clinic.

Cameron Johnson is a research assistant at The Menninger Clinic . Cameron collects and manages treatment outcomes survey data, which Menninger uses to help track the symptoms of patients.

Danna Ramirez is the Clinical Research Informatics Engineer at The Menninger Clinic . Her research interests include the neurobiology of psychiatric disorders, especially personality disorders and mood disorders

Mind Matters is a collaborative blog written by Menninger staff and an occasional invited guest to increase awareness about mental health. Launched in 2019, Mind Matters is curated and edited by an expert clinical team, which is led by Robyn Dotson Martin, LPC-S. Martin serves as an Outpatient Assessment team leader and staff therapist.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 05 April 2024

Addressing health needs in people with mental illness experiencing homelessness

- Nick Kerman ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5219-0449 1 &

- Vicky Stergiopoulos ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3941-9434 1 , 2

Nature Mental Health volume 2 , pages 354–366 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

881 Accesses

12 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social sciences

Homelessness among people with mental illness is a prevalent and persisting problem. This Review examines the intersection between mental illness and homelessness in high-income countries, including prevalence rates and changes over time, the harmful effects of homelessness, and evidence-based health and housing interventions for homeless people with mental illness. Special populations and their support needs are also highlighted. Throughout this Review, policy and service implementation failures that have precipitated and perpetuated homelessness among people with mental illness are discussed, and policy and practice priorities critical to reducing homelessness and improving health outcomes in this population are proposed.

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Psilocybin microdosers demonstrate greater observed improvements in mood and mental health at one month relative to non-microdosing controls

Homelessness is an extreme form of material deprivation that occurs when people do not have permanent, safe and adequate accommodations. Although there is no consensus on the types of living situation that constitute homelessness, definitions often include temporarily residing in emergency accommodations (such as shelters), living on the streets, in cars or in buildings not intended for human habitation or staying temporarily with family and friends (that is, hidden homelessness) 1 , 2 . People experiencing homelessness are also overrepresented in hospitals and jails, making these institutions central to some experiences of homelessness 3 , 4 .

Homelessness in its various forms is an enduring social problem that is widespread in high-income countries. An estimated 2.1 million people experience homelessness every year across 36 member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) 5 . As shown in Table 1 , homelessness estimates and trends vary considerably among high-income countries. However, comparisons between countries are challenging due to different methodological approaches and definitions of homelessness. Still, there are evident prevalence trends in some countries. In the USA, there was a very slight, gradual decline in daily homelessness rates from 647,258 in 2007 to 582,462 in 2022, before increasing to 653,104 in 2023, as measured by annual point-in-time counts 6 . Similarly, homelessness has stagnated or increased in many European countries during the past decade, with the notable exception of Finland, which has observed sizable decreases in the number of people experiencing homelessness over the past decade 7 , 8 . Other high-income countries have failed to monitor homelessness rates at the population level, or have done so very narrowly, yielding a lack of clarity about the extent of the problem and the effectiveness of the investments made to address it.

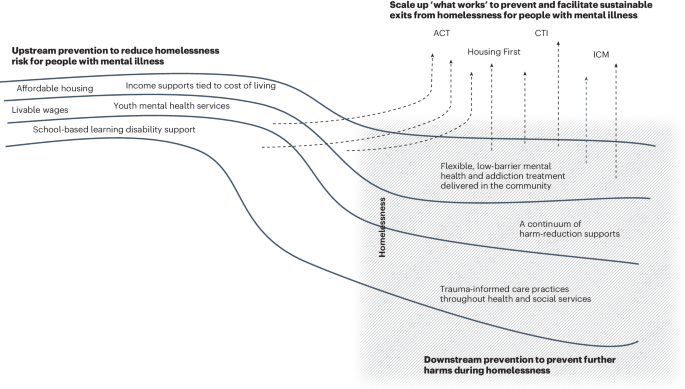

Homelessness is fundamentally a housing problem, with the limited availability of affordable housing being a foremost contributor to homelessness in communities 9 . However, other key structural- and individual-level factors can also affect rates of homelessness. For example, both unemployment and the quality of the social safety net, such as income support programs, have been tied to homelessness rates 10 , 11 , 12 . In addition, poor health, early childhood adversity and trauma, and involvement in the criminal justice system are associated with increased risk of homelessness 12 . Thus, populations experiencing marginalization, such as people with mental illness, that are disproportionately affected by these structural- and individual-level factors are at higher risk of homelessness. It is estimated that 76.2% of people experiencing homelessness have a current mental disorder 13 .

Given the persistence of homelessness in many jurisdictions and the prevalence of mental illness among people experiencing homelessness, this Review will discuss the intersection of mental illness and homelessness, and identify urgent priorities for action in high-income countries.

Mental illness and homelessness: emergence of an intractable problem

The intersection between mental illness and homelessness in many high-income countries is often described as having its modern origins in deinstitutionalization. Beginning in the 1960s, many psychiatric hospitals were closed in response to growing concerns about the poor quality of care in those facilities, emerging evidence on recovery in mental illness and advancements in psychotropic medications. The scale of the psychiatric hospital closures during deinstitutionalization transformed mental health systems. Of the 559,000 state psychiatric hospital beds that existed in the USA in 1955, over 400,000 had been closed by the early 1980s 14 . Similar reductions in psychiatric inpatient beds occurred in Canada (a 70.6% decline from 1965 to 1981) 15 and in the UK (a 60.0% decrease from 1954 to 1990) 16 . As a result, many long-stay hospital patients with serious mental illness were discharged to community settings. This transformational shift corresponded with rising rates of homelessness among people with mental illness during these decades. This led to assumptions that an insufficient supply of appropriate housing and mental health support alternatives had resulted in increased rates of homelessness for this population 17 . Recent research has questioned the extent to which there was a causal relationship between deinstitutionalization and homelessness rates among people with mental illness, with evidence that this may have been confounded by other societal changes that occurred during subsequent decades 18 . Nevertheless, deinstitutionalization precipitated the transformation of mental health systems, marked by the limited availability of community services and funding in some regions—ill-enduring effects with which community mental health systems continue to grapple and that disproportionally affect people with mental illness who experience homelessness 16 , 17 .