We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

Chapter 7: 10 Real Cases on Transient Ischemic Attack and Stroke: Diagnosis, Management, and Follow-Up

Jeirym Miranda; Fareeha S. Alavi; Muhammad Saad

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Case review, case discussion, clinical symptoms.

- Radiologic Findings

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Case 1: Management of Acute Thrombotic Cerebrovascular Accident Post Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Therapy

A 59-year-old Hispanic man presented with right upper and lower extremity weakness, associated with facial drop and slurred speech starting 2 hours before the presentation. He denied visual disturbance, headache, chest pain, palpitations, dyspnea, dysphagia, fever, dizziness, loss of consciousness, bowel or urinary incontinence, or trauma. His medical history was significant for uncontrolled type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and benign prostatic hypertrophy. Social history included cigarette smoking (1 pack per day for 20 years) and alcohol intake of 3 to 4 beers daily. Family history was not significant, and he did not remember his medications. In the emergency department, his vital signs were stable. His physical examination was remarkable for right-sided facial droop, dysarthria, and right-sided hemiplegia. The rest of the examination findings were insignificant. His National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score was calculated as 7. Initial CT angiogram of head and neck reported no acute intracranial findings. The neurology team was consulted, and intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA) was administered along with high-intensity statin therapy. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit where his hemodynamics were monitored for 24 hours and later transferred to the telemetry unit. MRI of the head revealed an acute 1.7-cm infarct of the left periventricular white matter and posterior left basal ganglia. How would you manage this case?

This case scenario presents a patient with acute ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) requiring intravenous t-PA. Diagnosis was based on clinical neurologic symptoms and an NIHSS score of 7 and was later confirmed by neuroimaging. He had multiple comorbidities, including hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, and smoking history, which put him at a higher risk for developing cardiovascular disease. Because his symptoms started within 4.5 hours of presentation, he was deemed to be a candidate for thrombolytics. The eligibility time line is estimated either by self-report or last witness of baseline status.

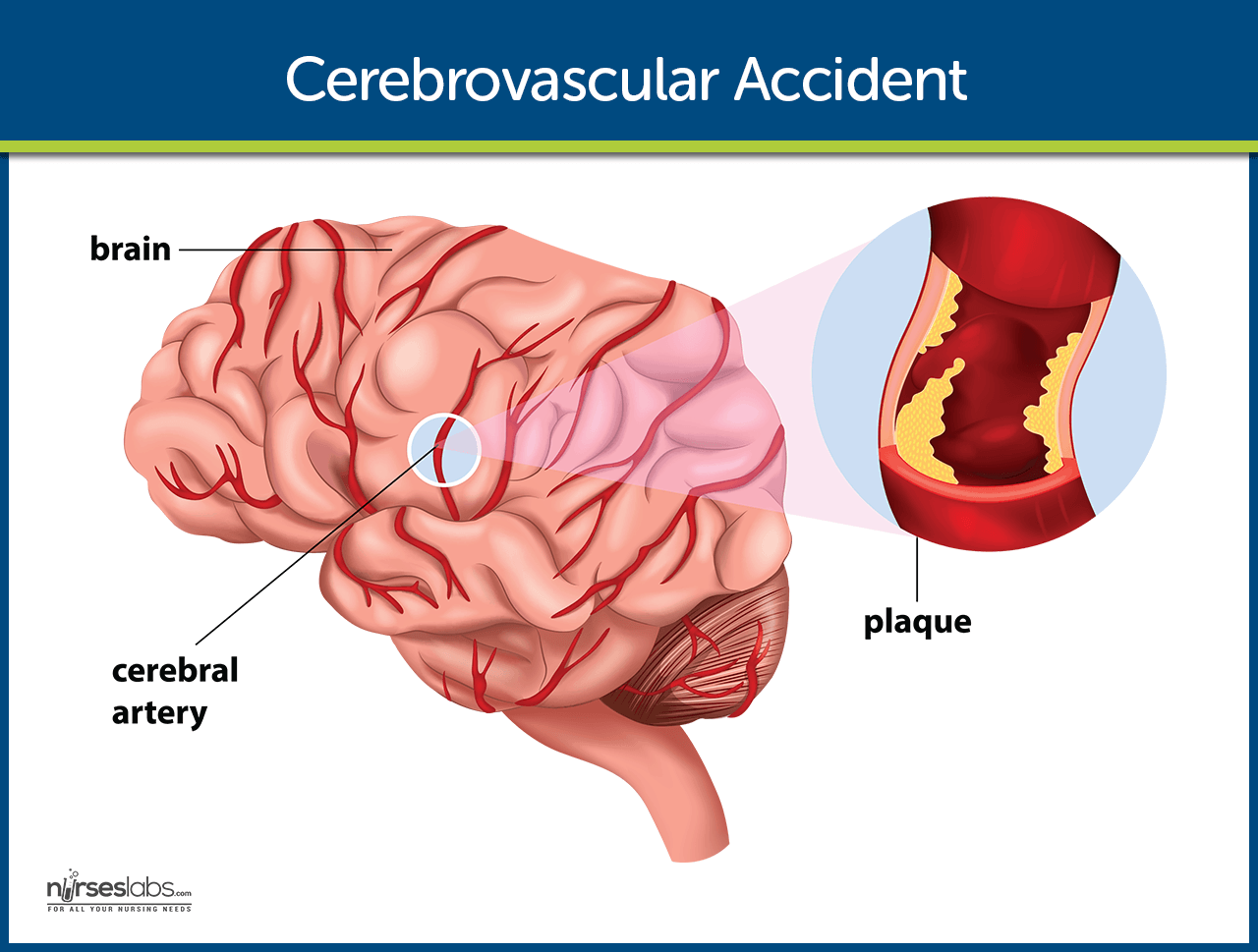

Ischemic strokes are caused by an obstruction of a blood vessel, which irrigates the brain mainly secondary to the development of atherosclerotic changes, leading to cerebral thrombosis and embolism. Diagnosis is made based on presenting symptoms and CT/MRI of the head, and the treatment is focused on cerebral reperfusion based on eligibility criteria and timing of presentation.

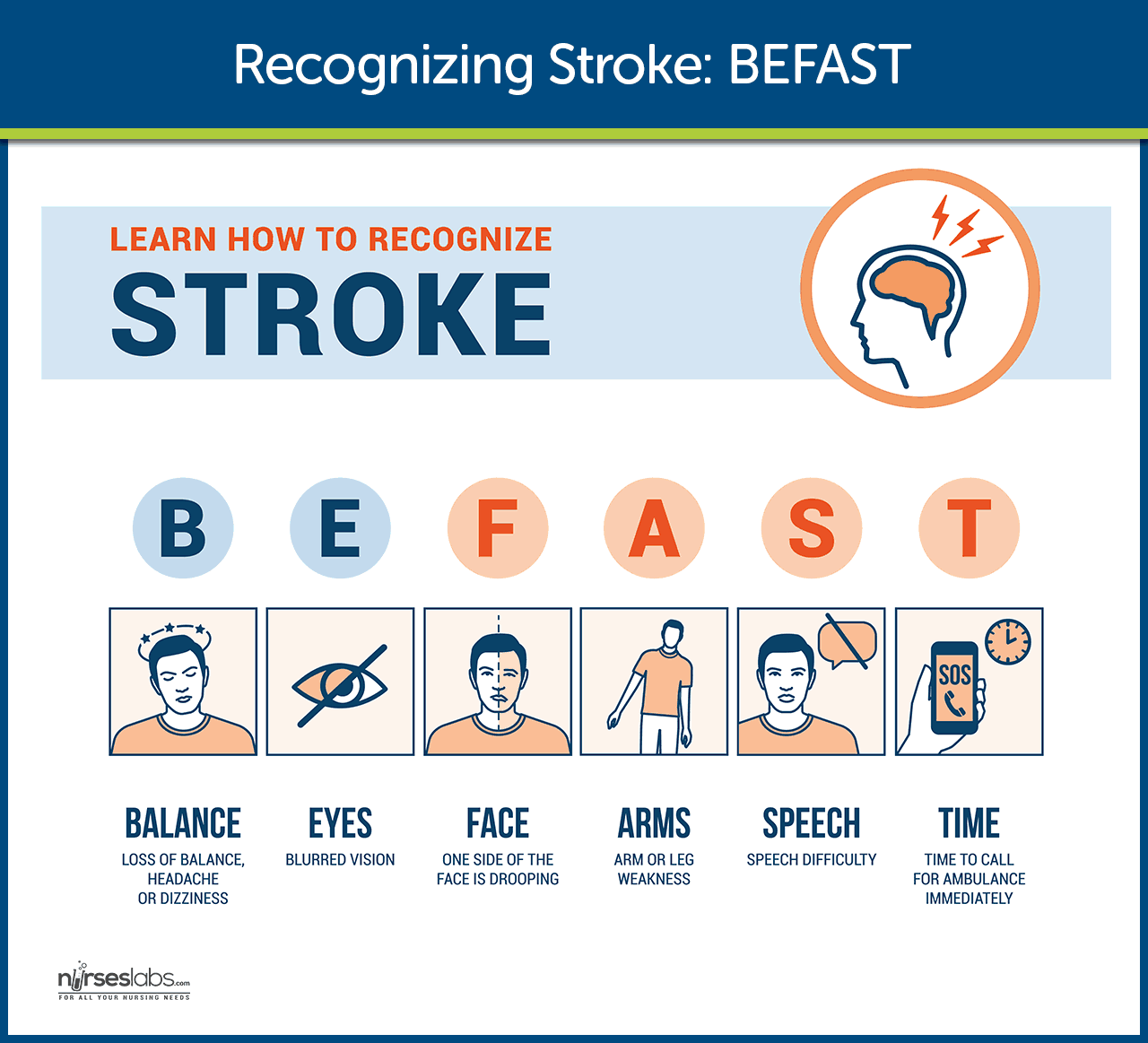

Symptoms include alteration of sensorium, numbness, decreased motor strength, facial drop, dysarthria, ataxia, visual disturbance, dizziness, and headache.

Get Free Access Through Your Institution

Pop-up div successfully displayed.

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMJ Case Rep

Case Report

The cause of the stroke: a diagnostic uncertainty, abhishek dattani.

1 Stroke Medicine, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK

Ava Jackson

2 Stroke and Geriatric Medicine, Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK

A 39-year-old man with a history of sickle cell disease (SCD) presented with left leg weakness. He had a normal CT head and CT angiogram, but MRI head showed multiple acute bilateral cortical infarcts including in the right precentral gyrus. The MRI findings were more in keeping with an embolic source rather than stroke related to SCD, although it could not be ruled out. He also had an echocardiogram which revealed a patent foramen ovale. He was treated with antiplatelet therapy and also had red blood cell exchange transfusion. His symptoms improved significantly and he was discharged with follow-up as an outpatient and a cardiology review.

Stroke in sickle cell disease (SCD) is managed very differently in comparison to other types of strokes. This case report demonstrates the management of these types of stroke but also brings in the element of doubt over the cause of a stroke in this patient due to his MRI and echocardiogram findings.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old man with known SCD of HbSS genotype presented to the Accident & Emergency department during the night with sudden-onset left leg weakness that began that morning. He explained that he woke up well in the morning but later developed numbness in the left leg which was followed by weakness. The numbness had settled but the weakness persisted. He had no speech or visual disturbance, no headache, no vomiting or dizziness and no back pain. He had a medical history of SCD diagnosed at a young age, with two previous chest crises and last admission in 2012 with an uncomplicated sickle crisis. He had no history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack but did have a history of hepatitis B infection, avascular necrosis of the right femoral head and previous blood transfusion in Nigeria 20 years ago. He had no other vascular risk factors. His regular medications included folic acid, penicillin V and naproxen.

On examination, his observations were normal. He had a regular pulse and a clear chest with normal heart sounds. His abdomen was soft and non-tender and he had no calf swelling or tenderness. Neurological examination revealed normal cranial nerve examination. On peripheral nerve examination, he had no wasting/fasciculations, normal tone and normal upper limb examination. Lower limb examination revealed a normal right lower limb but weakness in the left lower limb graded 3/5 hip flexion, 4/5 hip extension, 3/5 knee flexion and extension and 2/5 ankle dorsiflexion and plantarflexion. He had a downgoing right plantar reflex and an equivocal left plantar reflex. His sensation was normal and he had no limb ataxia. He had a positive Hoover’s test, however, and his neurology was showing significant improvement on further assessment. The patient’s National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was 1 on presentation and he had a normal ECG.

Investigations

His blood tests on admission showed a haemoglobin (Hb) level of 97 with a HbS of 87.4%, Hb F 4.0% and HbA 2.2%. A CT head showed no acute infarct and no intra or extra-axial haemorrhage. There was an area of mature ischaemic change in the left centrum semiovale extending into the cortex of the left precentral gyrus. He had a CT angiogram which showed normal intracranial and extracranial vessels.

MRI head ( figures 1–4 ) showed acute bilateral cortical infarcts in different arterial territories with some established ischaemic change. There was diffusion restriction involving the right precentral gyrus in keeping with the patient’s presentation. The multiple territories, however, suggested an embolic source or a patent foramen ovale (PFO). He had an echocardiogram which showed normal left ventricle and right ventricle with good systolic function. Bubble study ( figures 5 and 6 ) showed numerous bubbles crossing from the right to left heart with release of Valsalva suggesting the presence of a PFO. Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) was ruled out on ultrasound Doppler imaging of both legs.

MRI imaging showing bilateral cortical infarcts.

Diffusion restriction suggesting acute ischaemia.

Four-chamber views of bubble study showing bubbles crossing from the right atrium to left atrium across a patent foramen ovale.

Differential diagnosis

Given that the risk of stroke in patients with SCD is higher, it was important for the patient to be evaluated in the hyper-acute stroke unit (HASU) for further assessment and an MRI head with diffusion-weighted imaging.

Once an ischaemic event was confirmed on the MRI scan, the next step was to decide whether the stroke was due to SCD and this was a very difficult decision to make. The MRI findings were compatible with an embolic source rather than SCD. He did, however, have a high sickle percentage of 87.4.

His echocardiogram findings of a PFO added further doubt over the SCD causing the stroke, but it should be noted that PFOs are found in a significant proportion of the normal population and may be an incidental finding.

He was treated with antiplatelet therapy and a statin. His case was thoroughly discussed between the stroke, neuroradiology and haematology consultants and it was decided that he should have a red cell exchange transfusion as it was difficult to rule out SCD as the cause of the stroke. He went on to have the exchange transfusion without complications. His HbS percentage after exchange transfusion was 23.5.

Outcome and follow-up

This patient made a good recovery with significant improvement in his weakness during his stay in hospital and was discharged with follow-up. His blood tests at the time of the stroke included a young stroke screen which was negative including antinuclear antibodies, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody and anticardiolipin antibodies. His most recent review in the stroke clinic 5 months after presentation showed good improvement and no evidence of recurrence of stroke. He remains on clopidogrel and continues to have regular exchange transfusions with the haematology team without any complications. His most recent postexchange transfusion HbS percentage was 25.0.

Medical management of strokes has drastically changed in the UK with the introduction of HASU which is the ideal site of management of patients who are having acute cerebrovascular accidents. 1 The National Clinical Guideline for Stroke states that all patients with features suggesting an acute stroke should receive urgent brain imaging which would include either CT or diffusion-weighted MRI. 2 Patients with features that have resolved by the time of presentation, and therefore may have had a transient ischaemic attack, should be assessed by a stroke specialist urgently. Patients should also have carotid artery imaging with either ultrasound or CT angiogram. Acute stroke is a medical emergency and the initial management of acute ischaemic stroke would include the use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator ideally within 4.5 hours of onset of symptoms 3 followed by antiplatelet therapy if there has been no haemorrhagic transformation.

Stroke is more common in patients with SCD compared with the general population with prevalence thought to be around 3.75%, although this varies based on the sickle cell genotype. 4 The pathophysiology of stroke in SCD is thought to be different. The initial theory of the cause of stroke in SCD was an increase in blood viscosity due to sickled red cells which causes stasis and ischaemia leading to a stroke. There are, however, further factors that play a role including the attachment of red blood cells to the vascular endothelium leading to the activation of a pro-inflammatory state causing hyperplasia and fibrosis, and eventually, thrombosis. Furthermore, research suggests a role of the lack of L-arginine in patients with SCD, which leads to a reduction in the effectiveness of nitric oxide-mediated vasodilation pathways. 5 On the other hand, a study in 2015 has shown that first ischaemic strokes in adult patients with SCD were less likely to be secondary to vasculopathy in comparison to children (41% vs 92%) and were more likely to be cardioembolic or due to other causes such as antiphospholipid syndrome, cocaine use or other unknown causes. 6

Patients with SCD are at increased risk of ischaemic strokes and are also at a greater risk of haemorrhagic stroke in comparison to the general population with the greatest incidence being in the 20–29 age group (440 per 100 000 person-years vs 14 per 100 000 person-years in non-SCD). A few studies have been done to look at the risk factors associated with a haemorrhagic stroke in the SCD population and these appear to be recent blood transfusion, hypertension, coagulopathy, recent steroid treatment or acute chest crisis. 7

As with patients without SCD, it is important to perform rapid investigations for patients with SCD who present with symptoms suggestive of a stroke. Initial investigations include CT or MRI brain, although CT may miss early infarcts but is very sensitive for haemorrhagic strokes. It is recommended that vascular imaging, using either CT angiography or MRI angiography, be performed in patients with SCD who present with a stroke to evaluate the cerebral vasculature as well as extracranial disease. These imaging modalities also help to diagnose conditions such as Moyamoya which is a complication in SCD. In cases of subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral angiography can be used to evaluate cerebral aneurysms but in patients with SCD, this can increase risk of stroke and therefore it is recommended that they receive adequate hydration and exchange transfusion to maintain a HbS<30%. 7

Management of ischaemic stroke in SCD differs significantly from patients with non-SCD. Initial management includes oxygen supplementation to maintain peripheral oxygen saturations above 95% to prevent sickling due to deoxygenation. Thrombolysis has not been well studied in this population group and its use in acute ischaemic stroke in patients with SCD is debated. 8 Although there appears to be no specific contraindications against its use, it is known that patients with SCD have an increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage and this should be considered before the use of such agents. 7 The use of red blood cell exchange transfusion is recommended as it decreases HbS concentration, which cause the procoagulant and adhesive properties as well as maximising the delivery of oxygen and thereby decreasing vaso-occlusion. 9 A post-transfusion target usually consists of a Hb level of above 10 g/dL and HbS percentage of less than 30. 4 A retrospective study showed a fivefold decrease in recurrent stroke if exchange transfusion was done within 24 hours of symptom onset. 10 The chronic management and secondary prevention of stroke in these patients is mainly with chronic exchange transfusions usually at 3–4 week intervals to maintain a HbS percentage of under 30. Although there are clear benefits of exchange transfusions, they do not come without their risks and complications including alloimmunisation, haemolytic transfusion reactions and infection. 11 In our patient, there was a long discussion between the stroke, haematology and neuroradiology teams before a decision was made regarding exchange transfusions due to the risks involved. It was decided to commence exchange transfusions given his significantly raised HbS percentage and the findings of the MRI. Besides exchange transfusions, there is also further research looking at the use of hydroxyurea in patients with SCD who have had a stroke, although so far non-inferiority of hydroxyurea in comparison to exchange transfusions has been shown in primary prevention of stroke in patients with SCD. 12

In terms of management of patients with haemorrhagic strokes in patients with SCD, there is currently very little research. The current recommendation is to follow usual management for the general population including management of coagulopathy, transfer to the intensive care unit and good blood pressure control. As with ischaemic stroke, it is also recommended that exchange transfusion be carried out to maintain HbS percentage below 30, although there appears to be very little research into whether this is beneficial. 7 Surgical intervention is rarely needed as shown by the STITCH trial which found no significant difference in outcomes between early neurosurgery and medical management although this was done in a non-SCD population. 13

A PFO has been demonstrated in 10%–26% of healthy adults. 14 In young patients who have had a cryptogenic stroke, however, the prevalence is thought to be much higher, for example, 40% in one study. 15 It is thought that a PFO allows microemboli to pass into the systemic circulation leading to a stroke. Currently, medical management is the first choice of treatment with regard to a PFO following a stroke. This usually consists of antiplatelet therapy or in some cases anticoagulation with warfarin. The main study to look at whether antiplatelet therapy or anticoagulation should be used was the PICSS trial which showed no significant difference in primary end points between the aspirin group compared with the warfarin group. 16 Rarely, percutaneous therapy can be used to close the PFO but this is not usual practice. Meta-analysis has shown that this could reduce the risk of recurrent stroke by 86%. 17 On the other hand, a randomised trial consisting of 909 patients comparing medical therapy with closure of PFO showed no significant difference in primary end point (6.8% vs 5.5%, p=0.37) 18 and many centres currently choose not to close PFOs in such patients.

Our patient had SCD and a PFO. There is evidence that SCD increases the risk of venous thromboembolisms due to a hypercoagulable state and patients with SCD have a higher rate of DVT. 19 This raises the question of the stroke in our patient having been caused by microemboli passing into the arterial circulation through his PFO. The management of such patients is debatable and it is difficult to decide whether our patient’s stroke was caused by SCD alone or a combination of SCD and the PFO. The answer to this question is relevant beyond academic purposes as the patient would require long-term exchange transfusions if we feel the stroke was caused by his SCD. If, however, the PFO was a leading contribution, then he may not require long-term exchange transfusions and his ideal management would be medical management of stroke prevention. Indeed, there are currently limited studies looking into the management of stroke in patients with both SCD and a PFO and there needs to be more research to look at the long-term outcomes in such patients.

Learning points

- Stroke is common in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- The management of stroke in SCD differs significantly.

- Patent foramen ovale (PFO) provides thromboemboli an access to the systemic circulation to cause stroke in young patients.

- Management of stroke in patients with sickle cell disease and PFO provides further debate and needs more research.

Contributors: Both AD and AJ were involved with the conception and drafting of the article, revising it for important changes and providing final approval for the publication of the article. They both agree to be accountable for the article.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

This case study presents a 68-year old “right-handed” African-American man named Randall Swanson. He has a history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and a history of smoking one pack per day for the last 20 years. He is prescribed Atenolol for his HTN, and Simvastatin for Hyperlipidemia (but he has a history of not always taking his meds). His father had a history of hypertension and passed away from cancer 10 years ago. His mother has a history of diabetes and is still alive.

Randall was gardening with his wife on a relaxing Sunday afternoon. Out of nowhere, Randall fell to the ground. When his wife rushed to his side and asked how he was doing, he answered with garbled and incoherent speech. It was then that his wife noticed his face was drooping on the right side. His wife immediately called 911 and paramedics arrived within 6 minutes. Upon initial assessment, the paramedics reported that Randall appeared to be experiencing a stroke as he presented with right-sided facial droop and weakness and numbness on the right side of his body. Fortunately, Randall lived nearby a stroke center so he was transported to St. John’s Regional Medical Center within 17 minutes of paramedics arriving to his home.

Initial Managment

Upon arrival to the Emergency Department, the healthcare team was ready to work together to diagnose Randall. He was placed in bed with the HOB elevated to 30 degrees to decrease intracranial pressure and reduce any risks for aspiration. Randall’s wife remained at his side and provided the care team with his brief medical history which as previously mentioned, consists of hypertension, hyperlipidemia and smoking one pack per day for the last 20 years. He had no recent head trauma, never had a stroke, no prior surgeries, and no use of anticoagulation medications.

Physical Assessment

Upon first impression, Nurse Laura recognized that Randall was calm but looked apprehensive. When asked to state his name and date of birth, his speech sounded garbled at times and was very slow, but he could still be understood. He could not recall the month he was born in but he was alert and oriented to person, time, and situation. When asked to state where he was, he could not recall the word hospital. He simply pointed around the room while repeating “here.”

Further assessment revealed that his pupils were equal and reactive to light and that he presented with right-sided facial paralysis. Randall was able to follow commands but when asked to move his extremities, he could not lift his right arm and leg. He also reported that he could not feel the nurse touch his right arm and leg. Nurse Laura gathered the initial vital signs as follows: BP: 176/82, HR: 93, RR: 20, T:99.4, O2: 92% RA and a headache with pain of 3/10.

Doctor’s Orders

The doctor orders were quickly noted and included:

-2L O2 (to keep O2 >93%)

– 500 mL Bolus NS

– VS Q2h for the first 8 hrs.

-Draw labs for: CBC, INR, PT/INR, PTT, and Troponin

-Get an EKG

-Chest X ray

-Glucose check

-Obtain patient weight

-Perform a National Institute of Health Stroke Scale (also known as NIHSS) Q12h for the first 24 hours, then Q24h until he is discharged

-Notify pharmacy of potential t-PA preparation.

Nursing Actions

Nurse Laura started an 18 gauge IV in Randall’s left AC and started him on a bolus of 500 mL of NS. A blood sample was collected and quickly sent to the lab. Nurse Laura called the Emergency Department Tech to obtain a 12 lead EKG.

Pertinent Lab Results for Randall

The physician and the nurse review the labs:

WBC 7.3 x 10^9/L

RBC 4.6 x 10^12/L

Plt 200 x 10^9/L

LDL 179 mg/dL

HDL 43 mg/dL

Troponin <0.01 ng/mL

EKG and Chest X Ray Results

The EKG results and monitor revealed Randall was in normal sinus rhythm; CXR was negative for pulmonary or cardiac pathology

CT Scan and NIHSS Results

The NIH Stroke Scale was completed and demonstrated that Randall had significant neurological deficits with a score of 13. Within 20 minutes of arrival to the hospital, Randall had a CT-scan completed. Within 40 minutes of arrival to the hospital, the radiologist notified the ED physician that the CT-scan was negative for any active bleeding, ruling our hemorrhagic stroke.

The doctors consulted and diagnosed Randall with a thrombotic ischemic stroke and determined that that plan would include administering t-PA. Since Randall’s CT scan was negative for a bleed and since he met all of the inclusion criteria he was a candidate for t-PA. ( Some of the inclusion criteria includes that the last time the patient is seen normal must be within 3 hours, the CT scan has to be negative for bleeding, the patient must be 18 years or older, the doctor must make the diagnosis of an acute ischemic stroke, and the patient must continue to present with neurological deficits.)

Since the neurologist has recommended IV t-PA, the physicians went into Randall’s room and discussed what they found with him and his wife. Nurse Laura answered and addressed any remaining concerns or questions.

Administration

Randall and his wife decided to proceed with t-PA therapy as ordered, therefore Nurse Laura initiated the hospital’s t-PA protocol. A bolus of 6.73 mg of tPA was administered for 1 minute followed by an infusion of 60.59 mg over the course of 1 hour. ( This was determined by his weight of 74.8 kg). After the infusion was complete, Randall was transferred to the ICU for close observation. Upon reassessment of the patient, Randall still appeared to be displaying neurological deficits and his right-sided paralysis had not improved. His vital signs were assessed and noted as follows: BP: 149/79 HR: 90 RR: 18 T:98.9 O2: 97% 2L NC Pain: 2/10.

Randall’s wife was crying and he appeared very scared, so Nurse John tried to provide as much emotional support to them as possible. Nurse John paid close attention to Randall’s blood pressure since he could be at risk for hemorrhaging due to the medication. Randall was also continually assessed for any changes in neurological status and allergic reactions to the t-PA. Nurse John made sure that Stroke Core Measures were followed in order to enhance Randall’s outcome.

In the ICU, Randall’s neurological status improved greatly. Nurse Jan noted that while he still garbled speech and right-sided facial droop, he was now able to recall information such as his birthday and he could identify objects when asked. Randall was able to move his right arm and leg off the bed but he reported that he was still experiencing decreased sensation, right-sided weakness and he demonstrated drift in both extremities.

The nurse monitored Randall’s blood pressure and noted that it was higher than normal at 151/83. She realized this was an expected finding for a patient during a stroke but systolic pressure should be maintained at less than 185 to lower the risk of hemorrhage. His vitals remained stable and his NIHSS score decreased to an 8. Labs were drawn and were WNL with the exception of his LDL and HDL levels. His vital signs were noted as follows: BP 151/80 HR 92 RR 18 T 98.8 O2 97% RA Pain 0/10

The Doctor ordered Physical, Speech, and Occupational therapy, as well as a swallow test.

Swallowing Screen

Randall remained NPO since his arrival due to the risks associated with swallowing after a stroke. Nurse Jan performed a swallow test by giving Randall 3 ounces of water. On the first sip, Randall coughed and subsequently did not pass. Nurse Jan kept him NPO until the speech pathologist arrived to further evaluate Randall. Ultimately, the speech pathologist determined that with due caution, Randall could be put on a dysphagia diet that featured thickened liquids

Physical Therapy & Occupational Therapy

A physical therapist worked with Randall and helped him to carry out passive range of motion exercises. An occupational therapist also worked with Randall to evaluate how well he could perform tasks such as writing, getting dressed and bathing. It was important for these therapy measures to begin as soon as possible to increase the functional outcomes for Randall. Rehabilitation is an ongoing process that begins in the acute setting.

Day 3- third person

During Day 3, Randall’s last day in the ICU, Nurse Jessica performed his assessment. His vital signs remained stable and WNL as follows: BP: 135/79 HR: 90 RR: 18 T: 98.9 O2: 97% on RA, and Pain 0/10. His NIHSS dramatically decreased to a 2. Randall began showing signs of improved neurological status; he was able to follow commands appropriately and was alert and oriented x 4. The strength in his right arm and leg markedly improved. he was able to lift both his right arm and leg well and while he still reported feeling a little weakness and sensory loss, the drift in both extremities was absent.

Rehabilitation Therapies

Physical, speech, and occupational therapists continued to work with Randall. He was able to call for assistance and ambulate with a walker to the bathroom and back. He was able to clean his face with a washcloth, dress with minimal assistance, brush his teeth, and more. Randall continued to talk with slurred speech but he was able to enunciate with effort.

On day 4, Randall was transferred to the med-surg floor to continue progression. He continued to work with physical and occupational therapy and was able to perform most of his ADLs with little assistance. Randall could also ambulate 20 feet down the hall with the use of a walker.

Long-Term Rehabilitation and Ongoing Care

On day 5, Randall was discharged to a rehabilitation facility and continued to display daily improvement. The dysphagia that he previously was experiencing resolved and he was discharged home 1.5 weeks later. Luckily for Randall, his wife was there to witness his last known well time and she was able to notify first responders. They arrived quickly and he was able to receive t-PA in a timely manner. With the help of the interdisciplinary team consisting of nurses, therapists, doctors, and other personnel, Randall was put on the path to not only recover from the stroke but also to quickly regain function and quality of life very near to pre-stroke levels. It is now important that Randall continues to follow up with his primary doctor and his neurologist and that he adheres to his medication and physical therapy regimen.

Case Management

During Randall’s stay, Mary the case manager played a crucial role in Randall’s path to recovery. She determined that primary areas of concern included his history of medical noncompliance and unhealthy lifestyle. The case manager consulted with Dietary and requested that they provide Randall with education on a healthy diet regimen. She also provided him with smoking cessation information. Since Randall has been noncompliant with his medications, Mary determined that social services should consult with him to figure out what the reasons were behind his noncompliance. Social Services reported back to Mary that Randall stated that he didn’t really understand why he needed to take the medication. It was apparent that he had not been properly educated. Mary also needed to work with Randall’s insurance to ensure that he could go to the rehab facility as she knew this would greatly impact his ultimate outcome. Lastly, throughout his stay, the case manager provided Randall and his wife with resources on stroke educational materials. With the collaboration of nurses, education on the benefits of smoking cessation, medication adherence, lifestyle modifications, and stroke recognition was reiterated to the couple. After discharge, the case manager also checked up with Randall to make sure that he complied with his follow up appointments with the neurologist and physical and speech therapists,

- What risk factors contributed to Randall’s stroke?

- What types of contraindications could have prevented Randall from receiving t-PA?

- What factors attributed to Randall’s overall favorable outcome?

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

This presents an analysis of a case of Ischemic stroke in terms of possible etiology, pathophysiology, drug analysis and nursing care

New? Questions? Start Here!

- Information Hub

- Important Notices

- Need Access to Evidence

- Communities & Collections

- Publication Date

- Posting Date

- Subject(CINAHL)

- Item Format

- Level of Evidence

- Research Approach

- Sigma Chapters

- Author Affiliations

- Review Type

- Create an Account

Ischemic stroke: A case study

View file(s).

Author Information

- Martinez, Rudolf Cymorr Kirby P. ;

- Sigma Affiliation

Item Information

Item link - use this link for citations and online mentions..

Clinical Focus: Adult Medical/Surgical

Repository Posting Date

Type information.

| Type | | |

Category Information

| Evidence Level | ; ; |

Original Publication Info

| 2017-12-07 |

Conference Information

| Name |

Rights Holder

All rights reserved by the author(s) and/or publisher(s) listed in this item record unless relinquished in whole or part by a rights notation or a Creative Commons License present in this item record.

All permission requests should be directed accordingly and not to the Sigma Repository.

All submitting authors or publishers have affirmed that when using material in their work where they do not own copyright, they have obtained permission of the copyright holder prior to submission and the rights holder has been acknowledged as necessary.

Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke)

Learn about the nursing care management of patients with cerebrovascular accident in this nursing study guide .

Table of Contents

- What is Cerebrovascular Accident?

Classification

Risk factors, pathophysiology, statistics and epidemiology, clinical manifestations, complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, medical management, surgical management, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing care planning & goals, nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, what is cerebrovascular accident.

A cerebrovascular accident (CVA), an ischemic stroke or “ brain attack,” is a sudden loss of brain function resulting from a disruption of the blood supply to a part of the brain.

- Cerebrovascular accident or stroke is the primary cerebrovascular disorder in the United States.

- A cerebrovascular accident is a sudden loss of brain functioning resulting from a disruption of the blood supply to a part of the brain.

- It is a functional abnormality of the central nervous system .

- Cryptogenic strokes have no known cause, and other strokes result from causes such as illicit drug use, coagulopathies, migraine, and spontaneous dissection of the carotid or vertebral arteries.

- The result is an interruption in the blood supply to the brain, causing temporary or permanent loss of movement, thought, memory , speech, or sensation.

Strokes can be divided into two classifications.

- Ischemic stroke. This is the loss of function in the brain as a result of a disrupted blood supply.

- Hemorrhagic stroke. Hemorrhagic strokes are caused by bleeding into the brain tissue, the ventricles, or the subarachnoid space.

The following are the nonmodifiable and modifiable risk factors of Cerebrovascular accident:

Nonmodifiable

- Advanced age (older than 55 years)

- Gender (Male)

- Race (African American)

- Hypertension

- Atrial fibrillation

- Hyperlipidemia

- Asymptomatic carotid stenosis and valvular heart disease (eg, endocarditis, prosthetic heart valves)

- Periodontal disease

The disruption in the blood flow initiates a complex series of cellular metabolic events.

- Decreased cerebral blood flow. The ischemic cascade begins when cerebral blood flow decreases to less than 25 mL per 100g of blood per minute.

- Aerobic respiration. At this point, neurons are unable to maintain aerobic respiration.

- Anaerobic respiration. The mitochondria would need to switch to anaerobic respiration, which generates large amounts of lactic acid , causing a change in pH and rendering the neurons incapable of producing sufficient quantities of ATP.

- Loss of function. The membrane pumps that maintain electrolyte balances fail and the cells cease to function.

Stroke is a worldwide phenomenon suffered through all walks of life.

- Morbidity: In 2005, prevalence of stroke was estimated at 2.3 million males and 3.4 million females; many of the approximately 5.7 million U.S. stroke survivors have permanent stroke-related disabilities.

- Mortality: In 2004, stroke ranked fifth as the cause of death for those aged 45 to 64 years and third for those aged 65 years or older (National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [NHLBI], 2007), with 150,000 deaths (American Heart Association and American Stroke Association, 2008); hemorrhagic strokes are more severe, and mortality rates are higher than ischemic strokes, with a 30-day mortality rate of 40% to 80%.

- Cost: Estimated direct and indirect cost for 2008 was $65.5 billion (American Heart Association and American Stroke Association, 2008).

- Stroke is the third leading cause of death after heart disease and cancer .

- Approximately 780, 000 people experience a stroke each year in the United States.

- Approximately 600, 000 of these are new strokes, and 180, 000 are recurrent strokes.

- About 5.6 million noninstitutionalized stroke survivors are alive today.

- Stroke is the leading cause of serious, long-term disability in the United States.

- Direct and indirect costs for stroke cost $65.5 billion in 2008.

- Strokes are usually hemorrhagic (15%) or ischemic/nonhemorrhagic (85%).

- Ischemic strokes are categorized according to their cause: large artery thrombotic strokes (20%), small penetrating artery thrombotic strokes (25%), cardiogenic embolic strokes (20%), cryptogenic strokes (30%), and other (5%).

Strokes are caused by the following:

- Large artery thrombosis . Large artery thromboses are caused by atherosclerotic plaques in the large blood vessels of the brain.

- Small penetrating artery thrombosis. Small penetrating artery thrombosis affects one or more vessels and is the most common type of ischemic stroke.

- Cardiogenic emboli. Cardiogenic emboli are associated with cardiac dysrhythmias, usually atrial fibrillation .

Stroke can cause a wide variety of neurologic deficits, depending on the location of the lesion, the size of the area of inadequate perfusion, and the amount of the collateral blood flow. General signs and symptoms include numbness or weakness of face, arm, or leg (especially on one side of the body); confusion or change in mental status; trouble speaking or understanding speech; visual disturbances; loss of balance, dizziness, difficulty walking ; or sudden severe headache.

General signs and symptoms include numbness or weakness of face, arm, or leg (especially on one side of the body); confusion or change in mental status; trouble speaking or understanding speech; visual disturbances; loss of balance, dizziness, difficulty walking ; or sudden severe headache.

- Numbness or weakness of the face. Without adequate perfusion, oxygen is also low, and facial tissues could not function properly without them.

- Change in mental status. Due to decreased oxygen, the patient experiences confusion .

- Trouble speaking or understanding speech. Cells cease to function as a result of inadequate perfusion.

- Visual disturbances. The eyes also need enough oxygen for optimal functioning.

- Homonymous hemianopsia. There is loss of half of the visual field.

- Loss of peripheral vision . The patient experiences difficulty seeing at night and is unaware of objects or the borders of objects.

- Hemiparesis. There is a weakness of the face, arm, and leg on the same side due to a lesion in the opposite hemisphere.

- Hemiplegia. Paralysis of the face, arm, and leg on the same side due to a lesion in the opposite hemisphere.

- Ataxia. Staggering, unsteady gait and inability to keep feet together.

- Dysarthria. This is the difficulty in forming words.

- Dysphagia . There is difficulty in swallowing.

- Paresthesia. There is numbness and tingling of extremities and difficulty with proprioception.

- Expressive aphasia . The patient is unable to form words that is understandable yet can speak in single-word responses.

- Receptive aphasia . The patient is unable to comprehend the spoken word and can speak but may not make any sense.

- Global aphasia. This is a combination of both expressive and receptive aphasia.

- Hemiplegia, hemiparesis

- Flaccid paralysis and loss of or decrease in the deep tendon reflexes (initial clinical feature) followed by (after 48 hours) reappearance of deep reflexes and abnormally increased muscle tone (spasticity)

Communication Loss

- Dysarthria (difficulty speaking)

- Dysphasia (impaired speech) or aphasia (loss of speech)

- Apraxia (inability to perform a previously learned action)

Perceptual Disturbances and Sensory Loss

- Visual-perceptual dysfunctions (homonymous hemianopia [loss of half of the visual field])

- Disturbances in visual-spatial relations (perceiving the relation of two or more objects in spatial areas), frequently seen in patients with right hemispheric damage

- Sensory losses: slight impairment of touch or more severe with loss of proprioception; difficulty in interrupting visual, tactile, and auditory stimuli

Impaired Cognitive and Psychological Effects

- Frontal lobe damage: Learning capacity, memory, or other higher cortical intellectual functions may be impaired. Such dysfunction may be reflected in a limited attention span, difficulties in comprehension, forgetfulness, and lack of motivation.

- Depression , other psychological problems: emotional lability, hostility, frustration, resentment, and lack of cooperation.

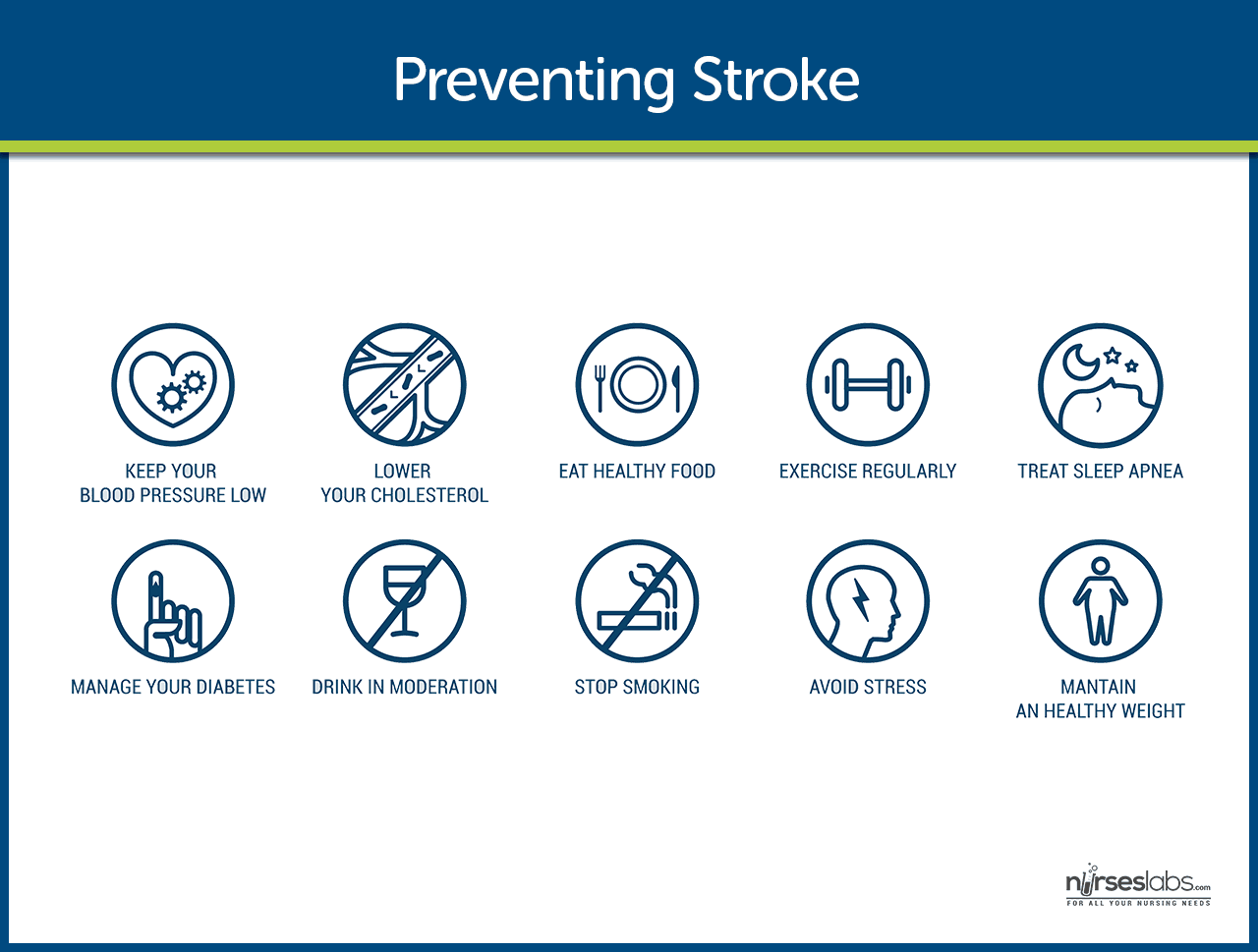

Primary prevention of stroke remains the best approach.

- Healthy lifestyle. Leading a healthy lifestyle which includes not smoking, maintaining a healthy weight, following a healthy diet, and daily exercise can reduce the risk of having a stroke by about one half.

- DASH diet. The DASH ( Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension ) diet is high in fruits and vegetables, moderate in low-fat dairy products, and low in animal protein and can lower the risk of stroke.

- Stroke risk screenings. Stroke risk screenings are an ideal opportunity to lower stroke risk by identifying people or groups of people who are at high risk for stroke.

- Education. Patients and the community must be educated about recognition and prevention of stroke.

- Low-dose aspirin . Research findings suggest that low-dose aspirin may lower the risk of stroke in women who are at risk.

If cerebral oxygenation is still inadequate; complications may occur.

- Tissue ischemia . If cerebral blood flow is inadequate, the amount of oxygen supplied to the brain is decreased, and tissue ischemia will result.

- Cardiac dysrhythmias. The heart compensates for the decreased cerebral blood flow, and with too much pumping, dysrhythmias may occur.

Any patient with neurologic deficits needs a careful history and complete physical and neurologic examination.

- CT scan . Demonstrates structural abnormalities, edema , hematomas, ischemia , and infarctions. Demonstrates structural abnormalities, edema , hematomas, ischemia, and infarctions. Note: May not immediately reveal all changes, e.g., ischemic infarcts are not evident on CT for 8–12 hr; however, intracerebral hemorrhage is immediately apparent; therefore, emergency CT is always done before administering tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA). In addition, patients with TIA commonly have a normal CT scan

- PET scan. Provides data on cerebral metabolism and blood flow changes.

- MRI. Shows areas of infarction, hemorrhage , AV malformations, and areas of ischemia.

- Cerebral angiography. Helps determine specific cause of stroke, e.g., hemorrhage or obstructed artery, pinpoints site of occlusion or rupture. Digital subtraction angiography evaluates patency of cerebral vessels, identifies their position in head and neck, and detects/evaluates lesions and vascular abnormalities.

- Lumbar puncture . Pressure is usually normal and CSF is clear in cerebral thrombosis, embolism, and TIA. Pressure elevation and grossly bloody fluid suggest subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage. CSF total protein level may be elevated in cases of thrombosis because of inflammatory process. LP should be performed if septic embolism from bacterial endocarditis is suspected.

- Transcranial Doppler ultrasonography. Evaluates the velocity of blood flow through major intracranial vessels; identifies AV disease, e.g., problems with carotid system (blood flow/presence of atherosclerotic plaques).

- EEG. Identifies problems based on reduced electrical activity in specific areas of infarction; and can differentiate seizure activity from CVA damage.

- Skull x-ray. May show a shift of pineal gland to the opposite side from an expanding mass; calcifications of the internal carotid may be visible in cerebral thrombosis; partial calcification of walls of an aneurysm may be noted in subarachnoid hemorrhage.

- ECG and echocardiography . To rule out cardiac origin as source of embolus (20% of strokes are the result of blood or vegetative emboli associated with valvular disease, dysrhythmias, or endocarditis).

- Laboratory studies to rule out systemic causes: CBC, platelet and clotting studies, VDRL/RPR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), chemistries ( glucose , sodium ).

Patients who have experienced TIA or stroke should have medical management for secondary prevention.

- Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator would be prescribed unless contraindicated, and there should be monitoring for bleeding .

- Increased ICP. Management of increased ICP includes osmotic diuretics , maintenance of PaCO2 at 30-35 mmHg, and positioning to avoid hypoxia through elevation of the head of the bed.

- Endotracheal Tube. There is a possibility of intubation to establish patent airway if necessary.

- Hemodynamic monitoring. Continuous hemodynamic monitoring should be implemented to avoid an increase in blood pressure .

- Neurologic assessment to determine if the stroke is evolving and if other acute complications are developing

Surgical management may include prevention and relief from increased ICP.

- Carotid endarterectomy. This is the removal of atherosclerotic plaque or thrombus from the carotid artery to prevent stroke in patients with occlusive disease of the extracranial cerebral arteries.

- Hemicraniectomy. Hemicraniectomy may be performed for increased ICP from brain edema in severe cases of stroke.

Nursing Management

After the stroke is complete, management focuses on the prompt initiation of rehabilitation for any deficits.

During the acute phase , a neurologic flow sheet is maintained to provide data about the following important measures of the patient’s clinical status:

- Change in level of consciousness or responsiveness.

- Presence or absence of voluntary or involuntary movements of extremities.

- Stiffness or flaccidity of the neck.

- Eye opening, comparative size of pupils, and pupillary reaction to light.

- Color of the face and extremities; temperature and moisture of the skin.

- Ability to speak.

- Presence of bleeding.

- Maintenance of blood pressure .

During the postacute phase , assess the following functions:

- Mental status (memory, attention span, perception, orientation, affect, speech/language).

- Sensation and perception (usually the patient has decreased awareness of pain and temperature).

- Motor control (upper and lower extremity movement); swallowing ability, nutritional and hydration status, skin integrity, activity tolerance , and bowel and bladder function.

- Continue focusing nursing assessment on impairment of function in patient’s daily activities.

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnoses for a patient with stroke may include the following:

- Impaired physical mobility related to hemiparesis, loss of balance and coordination , spasticity, and brain injury .

- Acute pain related to hemiplegia and disuse.

- Deficient self-care related to stroke sequelae.

- Disturbed sensory perception related to altered sensory reception, transmission, and/or integration.

- Impaired urinary elimination related to flaccid bladder , detrusor instability, confusion , or difficulty in communicating.

- Disturbed thought processes related to brain damage.

- Impaired verbal communication related to brain damage.

- Risk for impaired skin integrity related to hemiparesis or hemiplegia and decreased mobility .

- Interrupted family processes related to catastrophic illness and caregiving burdens.

- Sexual dysfunction related to neurologic deficits or fear of failure.

Main article: Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke) Nursing Care Plans

The major nursing care planning goals for the patient and family may include:

- Improve mobility.

- Avoidance of shoulder pain .

- Achievement of self-care.

- Relief of sensory and perceptual deprivation.

- Prevention of aspiration .

- Continence of bowel and bladder.

- Improved thought processes.

- Achieving a form of communication .

- Maintaining skin integrity .

- Restore family functioning.

- Improve sexual function.

- Absence of complications.

Nursing care has a significant impact on the patient’s recovery. In summary, here are some nursing interventions for patients with stroke:

- Positioning. Position to prevent contractures, relieve pressure, attain good body alignment, and prevent compressive neuropathies.

- Prevent flexion . Apply splint at night to prevent flexion of the affected extremity.

- Prevent adduction. Prevent adduction of the affected shoulder with a pillow placed in the axilla.

- Prevent edema. Elevate affected arm to prevent edema and fibrosis.

- Full range of motion. Provide full range of motion four or five times a day to maintain joint mobility.

- Prevent venous stasis. Exercise is helpful in preventing venous stasis, which may predispose the patient to thrombosis and pulmonary embolus .

- Regain balance. Teach patient to maintain balance in a sitting position, then to balance while standing and begin walking as soon as standing balance is achieved.

- Personal hygiene . Encourage personal hygiene activities as soon as the patient can sit up.

- Manage sensory difficulties. Approach patient with a decreased field of vision on the side where visual perception is intact.

- Visit a speech therapist. Consult with a speech therapist to evaluate gag reflexes and assist in teaching alternate swallowing techniques.

- Voiding pattern. Analyze voiding pattern and offer urinal or bedpan on patient’s voiding schedule.

- Be consistent in patient’s activities. Be consistent in the schedule, routines, and repetitions; a written schedule, checklists, and audiotapes may help with memory and concentration, and a communication board may be used.

- Assess skin. Frequently assess skin for signs of breakdown, with emphasis on bony areas and dependent body parts.

Improving Mobility and Preventing Deformities

- Position to prevent contractures; use measures to relieve pressure, assist in maintaining good body alignment, and prevent compressive neuropathies.

- Apply a splint at night to prevent flexion of affected extremity.

- Prevent adduction of the affected shoulder with a pillow placed in the axilla.

- Elevate affected arm to prevent edema and fibrosis.

- Position fingers so that they are barely flexed; place hand in slight supination. If upper extremity spasticity is noted, do not use a hand roll; dorsal wrist splint may be used.

- Change position every 2 hours; place patient in a prone position for 15 to 30 minutes several times a day.

Establishing an Exercise Program

- Provide full range of motion four or five times a day to maintain joint mobility, regain motor control, prevent contractures in the paralyzed extremity, prevent further deterioration of the neuromuscular system, and enhance circulation. If tightness occurs in any area, perform a range of motion exercises more frequently.

- Exercise is helpful in preventing venous stasis, which may predispose the patient to thrombosis and pulmonary embolus.

- Observe for signs of pulmonary embolus or excessive cardiac workload during exercise period (e.g., shortness of breath, chest pain , cyanosis , and increasing pulse rate ).

- Supervise and support the patient during exercises; plan frequent short periods of exercise, not longer periods; encourage the patient to exercise unaffected side at intervals throughout the day.

Preparing for Ambulation

- Start an active rehabilitation program when consciousness returns (and all evidence of bleeding is gone, when indicated).

- Teach patient to maintain balance in a sitting position, then to balance while standing (use a tilt table if needed).

- Begin walking as soon as standing balance is achieved (use parallel bars and have a wheelchair available in anticipation of possible dizziness).

- Keep training periods for ambulation short and frequent.

Preventing Shoulder Pain

- Never lift patient by the flaccid shoulder or pull on the affected arm or shoulder.

- Use proper patient movement and positioning (e.g., flaccid arm on a table or pillows when patient is seated, use of sling when ambulating).

- Range of motion exercises are beneficial, but avoid over strenuous arm movements.

- Elevate arm and hand to prevent dependent edema of the hand; administer analgesic agents as indicated.

Enhancing Self Care

- Encourage personal hygiene activities as soon as the patient can sit up; select suitable self-care activities that can be carried out with one hand.

- Help patient to set realistic goals; add a new task daily.

- As a first step, encourage patient to carry out all self-care activities on the unaffected side.

- Make sure patient does not neglect affected side; provide assistive devices as indicated.

- Improve morale by making sure patient is fully dressed during ambulatory activities.

- Assist with dressing activities (e.g., clothing with Velcro closures; put garment on the affected side first); keep environment uncluttered and organized.

- Provide emotional support and encouragement to prevent fatigue and discouragement.

Managing Sensory-Perceptual Difficulties

- Approach patient with a decreased field of vision on the side where visual perception is intact; place all visual stimuli on this side.

- Teach patient to turn and look in the direction of the defective visual field to compensate for the loss; make eye contact with patient, and draw attention to affected side.

- Increase natural or artificial lighting in the room; provide eyeglasses to improve vision.

- Remind patient with hemianopsia of the other side of the body; place extremities so that patient can see them.

Assisting with Nutrition

- Observe patient for paroxysms of coughing , food dribbling out or pooling in one side of the mouth , food retained for long periods in the mouth, or nasal regurgitation when swallowing liquids.

- Consult with speech therapist to evaluate gag reflexes; assist in teaching alternate swallowing techniques, advise patient to take smaller boluses of food, and inform patient of foods that are easier to swallow; provide thicker liquids or pureed diet as indicated.

- Have patient sit upright, preferably on chair, when eating and drinking; advance diet as tolerated.

- Prepare for GI feedings through a tube if indicated; elevate the head of bed during feedings, check tube position before feeding , administer feeding slowly, and ensure that cuff of tracheostomy tube is inflated (if applicable); monitor and report excessive retained or residual feeding .

Attaining Bowel and Bladder Control

- Perform intermittent sterile catheterization during the period of loss of sphincter control.

- Analyze voiding pattern and offer urinal or bedpan on patient’s voiding schedule.

- Assist the male patient to an upright posture for voiding.

- Provide highfiber diet and adequate fluid intake (2 to 3 L/day), unless contraindicated.

- Establish a regular time (after breakfast) for toileting.

Improving Thought Processes

- Reinforce structured training program using cognitive, perceptual retraining, visual imagery, reality orientation, and cueing procedures to compensate for losses.

- Support patient: Observe performance and progress, give positive feedback, convey an attitude of confidence and hopefulness; provide other interventions as used for improving cognitive function after a head injury.

Improving Communication

- Reinforce the individually tailored program.

- Jointly establish goals, with the patient taking an active part.

- Make the atmosphere conducive to communication , remaining sensitive to patient’s reactions and needs and responding to them in an appropriate manner; treat the patient as an adult.

- Provide strong emotional support and understanding to allay anxiety ; avoid completing patient’s sentences.

- Be consistent in schedule, routines, and repetitions. A written schedule, checklists, and audiotapes may help with memory and concentration; a communication board may be used.

- Maintain patient’s attention when talking with the patient, speak slowly, and give one instruction at a time; allow the patient time to process.

- Talk to aphasic patients when providing care activities to provide social contact.

Maintaining Skin Integrity

- Frequently assess skin for signs of breakdown, with emphasis on bony areas and dependent body parts.

- Employ pressure relieving devices; continue regular turning and positioning (every 2 hours minimally); minimize shear and friction when positioning.

- Keep skin clean and dry, gently massage the healthy dry skin and maintain adequate nutrition .

Improving Family Coping

- Provide counseling and support to the family.

- Involve others in patient’s care; teach stress management techniques and maintenance of personal health for family coping.

- Give family information about the expected outcome of the stroke, and counsel them to avoid doing things for the patient that he or she can do.

- Develop attainable goals for the patient at home by involving the total health care team, patient, and family.

- Encourage everyone to approach the patient with a supportive and optimistic attitude, focusing on abilities that remain; explain to the family that emotional lability usually improves with time.

Helping the Patient Cope with Sexual Dysfunction

- Perform indepth assessment to determine sexual history before and after the stroke.

- Interventions for patient and partner focus on providing relevant information, education, reassurance, adjustment

- of medications, counseling regarding coping skills, suggestions for alternative sexual positions, and a means of sexual expression and satisfaction.

Teaching points

- Teach patient to resume as much self care as possible; provide assistive devices as indicated.

- Have occupational therapist make a home assessment and recommendations to help the patient become more independent.

- Coordinate care provided by numerous health care professionals; help family plan aspects of care.

- Advise family that patient may tire easily, become irritable and upset by small events, and show less interest in daily events.

- Make a referral for home speech therapy. Encourage family involvement. Provide family with practical instructions to help patient between speech therapy sessions.

- Discuss patient’s depression with the physician for possible antidepressant therapy.

- Encourage patient to attend community-based stroke clubs to give a feeling of belonging and fellowship to others.

- Encourage patient to continue with hobbies, recreational and leisure interests, and contact with friends to prevent social isolation .

- Encourage family to support patient and give positive reinforcement.

- Remind spouse and family to attend to personal health and wellbeing.

Expected patient outcomes may include the following:

- Improved mobility.

- Absence of shoulder pain .

- Self-care achieved.

- Achieved a form of communication.

- Maintained skin integrity .

- Restored family functioning.

- Improved sexual function.

Patient and family education is a fundamental component of rehabilitation.

- Consult an occupational therapist. An occupational therapist may be helpful in assessing the home environment and recommending modifications to help the patient become more independent.

- Physical therapy. A program of physical therapy may be beneficial, whether it takes place in the home or in an outpatient program.

- Antidepressant therapy. Depression is a common and serious problem in the patient who has had a stroke.

- Support groups . Community-based stroke support groups may allow the patient and the family to learn from others with si milar problems and to share their experiences.

- Assess caregivers . Nurses should assess caregivers for signs of depression, as depression is also common among caregivers of stroke survivors.

The focus of documentation should involve:

- Individual findings including level of function and ability to participate in specific or desired activities.

- Needed resources and adaptive devices.

- Results of laboratory tests, diagnostic studies, and mental status or cognitive evaluation .

- SO/family support and participation.

- Plan of care and those involved in planning .

- Teaching plan.

- Response to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcomes .

- Modifications to plan of care.

Posts related to Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke):

- 8+ Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke) Nursing Care Plans

- Drugs Affecting Coagulation

10 thoughts on “Cerebrovascular Accident (Stroke)”

I’m impressed, I have been challenged to read more.

The article was helpful

Am so impressed with the write up am student will wish to develop a research topic in CVA

As a nursing student, I want to thank this article for the valuable information on cerebrovascular accident nursing management. Understanding the importance of proper care and management for stroke patients is a crucial aspect of my education and future practice as a nurse. This article has provided me with a deeper insight into the role of the nurse in promoting positive outcomes for stroke patients, and I am grateful for the opportunity to learn more about this important topic. Thank you!

very presented alihamudulillah i got something

Hi Mugoya, Wonderful to hear you gained something valuable from the study guide! If you’re curious about more or have any questions, feel free to reach out. Always here to help!

well explained great article for students ……… Kindly increase the number of mcqs

Hi Abdur, Thanks for the positive feedback on the article! I’m glad to hear it’s helpful for students. All of our practice questions are available at our Nursing Test Bank page . If there are specific topics you’d like to see more questions on, just drop a suggestion. Your input helps us create better resources!

So interesting, very very good notes.

So interesting topic to learn

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

NIHSS 23 on presentation, consistent with large left MCA syndrome. Non-contrast head CT showed a dense L MCA (figure 1A) without early infarct changes, ASPECTS 10 (figure 1B). He received Alteplase IV r-tPA with a door-to-needle time of 27 minutes, 54 minutes from symptom onset.

This case scenario presents a patient with acute ischemic cerebrovascular accident (CVA) requiring intravenous t-PA. Diagnosis was based on clinical neurologic symptoms and an NIHSS score of 7 and was later confirmed by neuroimaging.

CVA case study - LPN Program. LPN Program. Course. Foundations of Clinical Nursing (KSPN-0104) 46 Documents. Students shared 46 documents in this course. University Kansas City Kansas Community College. Academic year: 2020/2021. Uploaded by: Anonymous Student.

Some case studies in Wuhan described immense inflammatory responses to COVID-19, including elevated acute phase reactants, such as CRP and D-dimer. Raised D-dimers are a non-specific marker of a prothrombotic state and have been associated with greater morbidity and mortality relating to stroke and other neurological features. 14.

A stroke or cerebrovascular accident (CVA) is an acute compromise of the cerebral perfusion or vasculature. Approximately 85% of strokes are ischemic and rest are hemorrhagic.[1] In this discussion, we mainly confine to ischemic strokes. Over the past several decades, the incidence of stroke and mortality is decreasing.[2] Stroke is the leading cause of adult disability worldwide. It is thus ...

A PFO has been demonstrated in 10%-26% of healthy adults. 14 In young patients who have had a cryptogenic stroke, however, the prevalence is thought to be much higher, for example, 40% in one study. 15 It is thought that a PFO allows microemboli to pass into the systemic circulation leading to a stroke.

In this retrospective study, the case records of 1,287 stroke patients admitted to Al-basher Hospital during a three-year period were reviewed. The stroke patient cohort included 60% men and 40% ...

Signs and symptoms of stroke are presented contralaterally. The purpose of this case report is to demonstrate the use of PT interventions to improve shoulder function and gait mechanics in a post CVA patient. Case Description: Patient is a retired 75-yo male who sustained a left ischemic CVA in 2017 with an insidious onset.

The outcome of this study can help guide future clinicians in decision making with CVA patients who need improvement with shoulder ROM and gait mechanics Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA) is known as Stroke It is a damage to the brain due to an interruption of blood supply Two main types of stroke: ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke

Nurse Laura started an 18 gauge IV in Randall's left AC and started him on a bolus of 500 mL of NS. A blood sample was collected and quickly sent to the lab. Nurse Laura called the Emergency Department Tech to obtain a 12 lead EKG. Pertinent Lab Results for Randall. The physician and the nurse review the labs: WBC 7.3 x 10^9/L. RBC 4.6 x 10^12/L.

(CVA) , commonly known as a stroke, leaving 40% of stroke patients with moderate impairments and up to 30% with severe disabilities. 1 . ... This case study pertains to an individual in the sub-acute phase, 5 months post ischemic stroke. As most intensive therapies are started in the acute phase,

This presents an analysis of a case of Ischemic stroke in terms of possible etiology, pathophysiology, drug analysis and nursing care

A cerebrovascular accident (CVA), an ischemic stroke or " brain attack," is a sudden loss of brain function resulting from a disruption of the blood supply to a part of the brain. Cerebrovascular accident or stroke is the primary cerebrovascular disorder in the United States. A cerebrovascular accident is a sudden loss of brain functioning ...

cva case study. Course. Nursing Care of Adult I (NUR 390) 107 Documents. Students shared 107 documents in this course. University Concordia University Saint Paul. Academic year: 2023/2024. Uploaded by: Anonymous Student. This document has been uploaded by a student, just like you, who decided to remain anonymous.

Case Study 64 Acute Cerebrovascular Accident (CVA) N., a 79-year-old woman, arrives at the emergency room with expressive aphasia, left facial droop, left- sided hemiparesis, and mild dysphagia. Her husband states that when she awoke that morning at 0600, she stayed in bed, complaining of a mild headache over the right temple and feeling ...

Case study on cerebro vascular accident (CVA) or stroke. It include History, Physical Examination, nursing care plan and Orem's nursing theory applied. Cerebrovascular disorder or CVA is damage to part of the brain when its blood supply is suddenly reduced or stopped. The part of the brain deprived of blood dies and can no longer function.

Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA) John Gates, 59 years old Primary Concept Perfusion Interrelated Concepts (In order of emphasis) 1. Stress 2. Coping 3. Clinical Judgment 4. Patient Education RAPID Reasoning Case Study: STUDENT Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA) History of Present Problem:

CASE STUDY - CVA (Cerebrovascular Accident) - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. The document describes a case study of a 31-year-old male patient who suffered a craniocerebral trauma from a gunshot wound to the head. He underwent craniotomy, debridement, dural repair, and cerebrospinal fluid repair.

UNFOLDING Clinical Reasoning Case Study: STUDENT Cerebral Vascular Accident (CVA) History of Present Problem: John Gates is a 59-year-old male with a history of diabetes type II and hypertension who was at work when he had sudden onset of right-sided weakness, right facial droop, and difficulty speaking. He was transported to the emergency department (ED) where these symptoms continue to persist.

CVA Case Study. Course: Med Surg (NUR170) 168 Documents. Students shared 168 documents in this course. University: Galen College of Nursing. AI Chat. Info More info. Download. AI Quiz. Save. CASE STUDY ONE: Post-Clinical Assignment-W eek 1. Patient: Mrs. Johnson is an 89 y.o. female, admitted to Galen inpatient rehab for continued .

have selected a patient with CVA for my medical case study in critical care nursing [11]. The material is presented here to provide an overall frame work of nursing care for patient with cerebro vascular accident [12]. OBJECTIVES To perform a health assessment of the client with cerebro vascular accident.