An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley-Blackwell Online Open

Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories

David a cook.

1 Mayo Clinic Online Learning, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

2 Multidisciplinary Simulation Center, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

3 Division of General Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

Anthony R Artino, Jr

4 Division of Health Professions Education, Department of Medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland, USA

Associated Data

Table S2. A research agenda for motivation in education.

To succinctly summarise five contemporary theories about motivation to learn, articulate key intersections and distinctions among these theories, and identify important considerations for future research.

Motivation has been defined as the process whereby goal‐directed activities are initiated and sustained. In expectancy‐value theory, motivation is a function of the expectation of success and perceived value. Attribution theory focuses on the causal attributions learners create to explain the results of an activity, and classifies these in terms of their locus, stability and controllability. Social‐ cognitive theory emphasises self‐efficacy as the primary driver of motivated action, and also identifies cues that influence future self‐efficacy and support self‐regulated learning. Goal orientation theory suggests that learners tend to engage in tasks with concerns about mastering the content (mastery goal, arising from a ‘growth’ mindset regarding intelligence and learning) or about doing better than others or avoiding failure (performance goals, arising from a ‘fixed’ mindset). Finally, self‐determination theory proposes that optimal performance results from actions motivated by intrinsic interests or by extrinsic values that have become integrated and internalised. Satisfying basic psychosocial needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness promotes such motivation. Looking across all five theories, we note recurrent themes of competence, value, attributions, and interactions between individuals and the learning context.

Conclusions

To avoid conceptual confusion, and perhaps more importantly to maximise the theory‐building potential of their work, researchers must be careful (and precise) in how they define, operationalise and measure different motivational constructs. We suggest that motivation research continue to build theory and extend it to health professions domains, identify key outcomes and outcome measures, and test practical educational applications of the principles thus derived.

Short abstract

Discuss ideas arising from the article at www.mededuc.com discuss.

Introduction

The concept of motivation pervades our professional and personal lives. We colloquially speak of motivation to get out of bed, write a paper, do household chores, answer the phone, and of course, to learn. We sense that motivation to learn exists (as opposed to being a euphemism, intellectual invention or epiphenomenon) and is important as both a dependent variable (higher or lower levels of motivation resulting from specific educational activities) 1 and an independent variable 2 (motivational manipulations to enhance learning) 3 , 4 , 5 . But what do we really mean by motivation to learn, and how can a better understanding of motivation influence what we do as educators?

Countless theories have been proposed to explain human motivation. 6 Although each sheds light on specific aspects of motivation, each of necessity neglects others. The diversity of theories creates confusion because most have areas of conceptual overlap and disagreement, and many employ an idiosyncratic vocabulary using different words for the same concept and the same word for different concepts. 7 Although this can be disconcerting, each contemporary theory nonetheless contributes a unique perspective with potentially novel insights and distinct implications for practice and future research.

Previous reviews of motivation in health professions education have focused on practical implications or broad overviews without extended theoretical elaborations, 2 , 3 or focused on only one theory. 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 A review that explains and contrasts multiple theories will encourage a more nuanced understanding of motivational principles, and will facilitate additional research to advance the science in this field.

The purpose of this cross‐cutting edge article is to succinctly summarise five contemporary theories about motivation to learn, clearly articulate key intersections and distinctions among theories, and identify important considerations for future research. We selected these theories based on their presence in recent reviews; 6 , 17 , 18 , 19 we sought but did not find other broadly‐recognised modern theories. Our goal is not to present a comprehensive examination of recent evidence, but to make the theoretical foundations of motivation accessible to medical educators. We acknowledge that for each theory we can scarcely scratch the surface, and thus suggest further reading for those who wish to study in greater depth (see Table 1 ).

Summary of contemporary motivation theories

AT = attribution theory; EVT = expectancy‐value theory; GOT = goal orientation theory; SCT = social‐cognitive theory; SDT = self‐determination theory.

For this review we define motivation as ‘the process whereby goal‐directed activities are instigated and sustained’, 6 (pg 5) Although others exist, this definition highlights four key concepts: motivation is a process; it is focused on a goal; and it deals with both the initiation and the continuation of activity directed at achieving that goal.

Common themes

We have identified four recurrent themes across the five theories discussed below, and believe that an up‐front overview will help readers recognise commonalities and differences across theories. Table 1 offers a concise summary of each theory and Table 2 attempts to clarify overlapping terminology.

Similar concepts and terminology across several contemporary theories: clarifying confusable terminology

All contemporary theories include a concept related to beliefs about competence . Variously labelled expectancy of success, self‐efficacy, confidence and self‐concept, these beliefs all address, in essence, the question ‘Can I do it?’. However, there are important distinctions both between and within theories, as elaborated below. For example, self‐concept and earlier conceptions of expectancy of success (expectancy‐value theory) viewed these beliefs in general terms (e.g. spanning a broad domain such as ‘athletics’ or ‘clinical medicine’, or generalising across time or situations). By contrast, self‐efficacy (social‐cognitive theory) and later conceptions of expectancy of success viewed these beliefs in much more task‐ and situation‐specific terms (e.g. ‘Can I grade the severity of aortic stenosis?’).

Most theories also include a concept regarding the value or anticipated result of the learning task. These beliefs include specific terms such as task value, outcome expectation and intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation. All address the question, ‘Do I want do to it?’ or ‘What will happen (good or bad) if I do?’. Again, there are important distinctions between theories. For example, task value (expectancy‐value theory) focuses on the perceived importance or usefulness of successful task completion, whereas outcome expectation (social‐cognitive theory) focuses on the probable (expected) result of an action if full effort is invested.

Most theories discuss the importance of attributions in shaping beliefs and future actions. Learners frequently establish conscious or unconscious links between an observed event or outcome and the personal factors that led to this outcome (i.e. the underlying cause). To the degree that learners perceive that the underlying cause is changeable and within their control, they will be more likely to persist in the face of initial failure.

Finally, all contemporary theories of motivation are ‘cognitive’ in the sense that, by contrast with some earlier theories, they presume the involvement of mental processes that are not directly observable. Moreover, recent theories increasingly recognise that motivation cannot be fully explained as an individual phenomenon, but rather that it often involves interactions between an individual and a larger social context. Bandura labelled his theory a ‘social‐cognitive theory’ of learning, but all of the theories discussed below include both social and cognitive elements .

Again, each theory operationalises each concept slightly differently and we encourage readers to pay attention to such distinctions (using Table 2 for support) for the remainder of this text.

Expectancy‐value theories

In a nutshell, expectancy‐value theories 20 , 21 identify two key independent factors that influence behaviour (Fig. 1 ): the degree to which individuals believe they will be successful if they try (expectancy of success), and the degree to which they perceive that there is a personal importance, value or intrinsic interest in doing the task (task value).

Expectancy‐value theory. This is a simplified version of Wigfield and Eccles's theory; it does not contain all of the details of their theory and blurs some subtle but potentially important distinctions. The key constructs of task value and expectancy of success are influenced by motivational beliefs, which are in turn determined by social influences that are perceived and interpreted by learner cognitive processes

Expectancy of success is more than a perception of general competence; it represents a future‐oriented conviction that one can accomplish the anticipated task. If I do not believe I will be successful in accomplishing a task, I am unlikely to begin. Such beliefs can be both general (e.g. global self‐concept) and specific (judgements of ability to learn a specific skill or topic). According to Wigfield and Eccles, 20 expectancy of success is shaped by motivational beliefs that fall into three broad categories: goals, self‐concept and task difficulty. Goals refer to specific short‐ and long‐term learning objectives. Self‐concept refers to general impressions about one's capacity in this task domain (e.g. academic ability, athletic prowess, social skills or good looks). Task difficulty refers to the perceived (not necessarily actual) difficulty of the specific task. Empirical studies show that expectancy beliefs predict both engagement in learning activities and learning achievement (e.g. test scores and grades). In fact, expectancy of success may be a stronger predictor of success than past performance. 20

According to expectancy‐value theorists, however, motivation requires more than just a conviction that I can succeed; I must also expect some immediate or future personal gain or value. Like expectancy of success, task value or valence is perceived (not necessarily actual) and at times idiosyncratic. At least four factors have been conceived as contributing to task value: a given topic might be particularly interesting or enjoyable to the learner (interest or intrinsic value ); learning about a topic or mastering a skill might be perceived as useful for practical reasons, or a necessary step toward a future goal (utility or extrinsic value ); successfully learning a skill might hold personal importance in its own right or as an affirmation of the learner's self‐concept (importance or attainment value ); and focusing time and energy on one task means that other tasks are neglected (opportunity costs ). Other costs and potential negative consequences include anxiety, effort and the possibility of failure. For example, a postgraduate physician might spend extra time learning cardiac auscultation simply because he finds it fascinating, or because he believes it will help him provide better care for patients, or because he perceives this as a fundamental part of his persona as a physician. Alternatively, he might spend less time learning this skill in order to spend more time mastering surgical skills, or because he simply doesn't feel it is worth the effort. Although some evidence suggests that these four factors (interest, utility, importance and cost) are distinguishable from one another in measurement, 20 it is not yet known whether learners make these distinctions in practice. Task value is, in theory, primarily shaped by one motivational belief: affective memories (reactions and emotions associated with prior experiences). Favourable experiences enhance perceived value; unfavourable experiences diminish it.

The motivational beliefs that determine expectancy of success (goals, self‐concept and task difficulty) and task value (affective memories) are in turn shaped by life events, social influences (parents, teacher or peer pressure, professional values, etc.) and the environment. These shaping forces are interpreted through the learner's personal perspectives and perceptions (i.e. cognitive processes). It is perception, and not necessarily reality, that governs motivational beliefs.

Empirical studies (nearly all of them outside of medical education) show that both expectancy of success and value are associated with learning outcomes, including choice of topics to study, degree of involvement in learning (engagement and persistence) and achievement (performance). Task value seems most strongly associated with choice, whereas expectancy of success seems most strongly associated with engagement, depth of processing and learning achievement. 20 In other words, in choosing whether to learn something the task value matters most; once that choice has been made, expectancy of success is most strongly associated with actual success.

Attribution theory

Attribution theory (Fig. 2 ) explains why people react variably to a given experience, suggesting that different responses arise from differences in the perceived cause of the initial outcome. Success or failure in mastering a new skill, for example, might be attributed to personal effort, innate ability, other people (e.g. the teacher) or luck. These attributions are often subconscious, but strongly influence future activities. Failure attributed to lack of ability might discourage future effort, whereas failure attributed to poor teaching or bad luck might suggest the need to try again, especially if the teacher or luck is expected to change. Attributions directly influence expectancy of future success, and indirectly influence perceived value as mediated by the learner's emotional response to success or failure.

Attribution theory. This is a simplified version of Weiner's theory; it does not contain all of the details of his theory and blurs some subtle but potentially important distinctions. The process begins with an event; if the outcome is expected or positive, it will often directly elicit emotions (happiness or frustration) without any further action. However, outcomes that are unexpected, negative or perceived as important will often awaken the inquisitive ‘naïve scientist’ who seeks to identify a causal explanation. The individual will interpret the outcome in light of personal and environmental conditions to ‘hypothesise’ a perceived cause, which can be organised along three dimensions: locus, stability and controllability. Stability influences perceived expectancy of success. Locus, controllability and stability collectively influence emotional responses (which reflect the subjective value) and these in turn drive future behaviours

Attribution theory postulates that humans have a tacit goal of understanding and mastering themselves and their environment, and act as ‘naïve scientists’ to establish cause‐effect relationships for events in their lives. The process of attribution starts with an event, such as receiving a grade or learning a skill. If the result is expected and positive, the learner is content and the naïve scientist is not aroused (i.e. there is nothing to investigate). Conversely, if the result is negative, unexpected or particularly important, the scientist begins to search (often subconsciously) for an explanation, taking into account personal and environmental factors to come up with an hypothesis (i.e. an attribution: ability, effort, luck, health, mood, etc.). However, attributions do not directly motivate behaviour. Rather, they are interpreted or reframed into psychologically meaningful (actionable) responses. Empirical research suggests that such interpretations occur along three distinct conceptual dimensions: locus (internal to the learner or external), stability (likely to change or fixed) and controllability (within or outside the learner's control). For example, poor instructional quality (external locus) might be stable (the only teacher for this topic) or unstable (several other teachers available), and controllable (selected by the learner) or uncontrollable (assigned by others), depending on the learner's perception of the situation. Bad luck is typically interpreted as external, unstable and uncontrollable; personal effort is internal, changeable and controllable; and innate skill is internal, largely fixed and uncontrollable.

Weiner linked attributions with motivation through the constructs of expectancy of success and task value. 22 Expectancy of success is directly influenced by perceived causes, primarily through the stability dimension: ‘If conditions (the presence or absence of causes) are expected to remain the same, then the outcome(s) experienced in the past will be expected to recur. … If the causal conditions are perceived as likely to change, then … there is likely to be uncertainty about subsequent outcomes’. 22 Locus and controllability are not strongly linked with expectancy of success, because past success (regardless of locus orientation or degree of controllability) will predict future success if conditions remain stable.

By contrast, the link between attributions and ‘goal incentives’ (i.e. task value) is less direct, being mediated instead by the learner's emotions or ‘affective response’. Weiner distinguishes the objective value of achieving a goal (e.g. earning a dollar or learning a skill) from the subjective or affective value of that achievement (e.g. happiness or pride), and argues that there is ‘no blatant reason to believe that objective value is influenced by perceived causality … but [causal ascriptions] do determine or guide emotional reactions, or the subjective consequences of goal attainment’. 22 Other emotional reactions include gratitude, serenity, surprise, anger, guilt, hopelessness, pity and shame. Cognitive processes influence the interplay between an event, the perceived cause and the attributed emotional reaction, with complex and often idiosyncratic results (i.e. how we think influences how we feel). ‘For example, a dollar attained because of good luck could elicit surprise; a dollar earned by hard work might produce pride; and a dollar received from a friend when in need is likely to beget gratitude’, 22 although it might also beget shame or guilt. Weiner distinguishes outcome‐dependent and attribution‐dependent emotions. Outcome‐dependent emotions are the direct result of success (e.g. happiness) or failure (e.g. sadness and frustration). Attribution‐dependent emotions are, as the name implies, determined by the inferred causal dimension: pride and self‐esteem (‘internal’ emotions) are linked with locus; anger, gratitude, guilt, pity and shame (‘social’ emotions) are connected with controllability; and hopelessness and the intensity of many other emotions are associated with stability (i.e. one might feel greater gratitude or greater shame because of a stable cause).

Attribution theory proposes several ‘antecedent conditions’ that influence the attributional process. Environmental antecedents include social norms and information received from self and others (e.g. feedback). Personal antecedents include differences in causal rules, attributional biases and prior knowledge. Attributional biases or errors include: the ‘fundamental attribution error’, in which situation or context‐specific factors are ignored, such that a single event is extrapolated into a universal trait of the individual; self‐serving bias, in which success is ascribed to internal causes and failure is ascribed to external causes; and actor‐observer bias, in which the learner's actions are situation specific and the actions of others are a general trait.

Social‐cognitive theory

Social‐cognitive theory is most generally a theory of learning. It contends that people learn through reciprocal interactions with their environment and by observing others, rather than simply through direct reinforcement of behaviours (as proposed by behaviourist theories of learning). 23 As regards motivation, the theory emphasises that humans are not thoughtless actors responding involuntarily to rewards and punishments, but that cognition governs how individuals interpret their environment and self‐regulate their thoughts, feelings and actions.

Bandura 23 theorised that human performance results from reciprocal interactions between three factors (‘triadic reciprocal determinism’): personal factors (e.g. beliefs, expectations, attitudes and biology), behavioral factors, and environmental factors (both the social and physical environment). Humans are thus proactive and self‐regulating rather than reactive organisms shaped only by the environment; they are ‘both products and producers of their own environments and of their own social systems’. 24 Consider, for example, a medical student in a surgery clerkship that is full of highly competitive peers and is run by a physician with little tolerance of mistakes. Such an environment will interact with the student's personal characteristics (e.g. his confidence, emotions and prior knowledge) to shape how he behaves and whether or not he learns. At the same time, how he behaves will influence the environment and may change some of his personal factors (e.g. his thoughts and feelings). Thus, the extent to which this student is motivated to learn and perform is determined by the reciprocal interactions of his own thoughts and feelings, the nature of the learning environment and his actions.

The active process of regulating one's behaviour and manipulating the environment in pursuit of personal goals is fundamental to functioning as a motivated individual. Whether or not people choose to pursue their goals depends, in no small measure, on beliefs about their own capabilities, values and interests. 24 Chief among these self‐beliefs is self‐efficacy, defined as ‘People's beliefs about their capabilities to produce designated levels of performance that exercise influence over events that affect their lives’. 25 Self‐efficacy is a belief about what a person can do rather than a personal judgement about one's physical or psychological attributes. 26 In Bandura's words, ‘Unless people believe they can produce desired effects by their actions, they have little incentive to act’. 27 Thus, self‐efficacy forms the foundation for motivated action.

Unlike broader notions of self‐concept or self‐esteem, self‐efficacy is domain, task and context‐specific. For instance, a medical student might report fairly high self‐efficacy for simple suturing but may have much lower self‐efficacy for other surgical procedures, or might have lower self‐efficacy in a competitive environment than in a cooperative one.

Self‐efficacy should not be confused with outcome expectation – the belief that certain outcomes will result from given actions 18 (i.e. the anticipated value to the individual). Because self‐efficacy beliefs help to determine the outcomes one expects, the two constructs are typically positively correlated, yet sometimes self‐efficacy and outcome expectations diverge. For example, a high‐performing, highly efficacious college student may choose not to apply to the most elite medical school because she expects a rejection. In this case, academic self‐efficacy is high but outcome expectations are low. Research indicates that self‐efficacy beliefs are usually better predictors of behaviour than are outcome expectations. 26 , 27 Ultimately, however, both self‐efficacy and favourable outcome expectations are required for optimal motivation. 18

Bandura, Zimmerman and Schunk have identified the key role of self‐efficacy in activating core learning processes, including cognition, motivation, affect and selection. 6 , 25 , 28 , 29 Learners come to any learning task with past experiences, aptitudes and social supports that collectively determine their pre‐task self‐efficacy. Several factors influence self‐efficacy during the task (Fig. 3 ), and during and after the task learners interpret cues that further shape self‐efficacy. 27 Among these sources of self‐efficacy, the most powerful is how learners interpret previous experiences (so‐called enactive mastery experiences ). Generally speaking, successes reinforce one's self‐efficacy, whereas failures weaken it. In addition, learners interpret the outcomes of others’ actions ( modelling ). Learners may adjust their own efficacy beliefs based on such vicarious experiences, particularly if they perceive the model as similar to themselves (e.g. a near‐peer). The influence of verbal persuasion (‘You can do it!’) appears to be limited at best. Furthermore, persuasion that proves unrealistic (e.g. persuasion to attempt a task that results in failure) can damage self‐efficacy and lowers the persuader's credibility. Finally, physiological and emotional information shapes self‐efficacy beliefs: enthusiasm and positive emotions typically enhance self‐efficacy whereas negative emotions diminish it. 24 , 27

Social‐cognitive model of motivated learning. This is adapted from Schunk's model of motivated learning; it incorporates additional concepts from Bandura and other authors. Learners begin a learning task with pre‐existing self‐efficacy determined by past experiences, aptitudes and social supports. Learners can perform the task themselves or watch others (e.g. instructor or peer models) perform the task. During the task, self‐efficacy, together with other personal and situational factors, influences cognitive engagement, motivation to learn, emotional response and task selection. During and after the task, learners perceive and interpret cues that influence self‐efficacy for future tasks. Zimmerman defined a three‐phase self‐regulation cycle that mirrors this model, comprised of forethought (pre‐task), performance and volitional control (during task) and self‐reflection (after task)

One way in which social‐cognitive theory has been operationalised for practical application involves the concept of self‐regulation, which addresses how students manage their motivation and learning. Zimmerman proposed a model of self‐regulation 30 comprising three cyclical stages: forethought (before the task, e.g. appraising self‐efficacy, and establishing goals and strategies), performance (during the task, e.g. self‐monitoring) and self‐reflection (after the task). Self‐regulation is an area of active investigation in medical education. 14 , 15

Goal orientation (achievement goal) theories

The meaning of ‘goals’ in goal orientation theories 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 (also called achievement goal theory) is different from that in most other motivation theories. Rather than referring to learning objectives (‘My goal is to learn about cardiology’), the goals in this cluster of theories refer to broad orientations or purposes in learning that are commonly subconscious. With performance goals the primary concern is to do better than others and avoid looking dumb: ‘I want to get a good grade’. Mastery goals , by contrast, focus on the intrinsic value of learning (i.e. gaining new knowledge or skills): ‘I want to understand the material’. These broad orientations lead in turn to different learning behaviours or approaches. Dweck's theory of ‘implicit theories of intelligence’ takes these two orientations further, suggesting that they reflect learners’ underlying attributions (‘mindsets’, or dispositional attitudes and beliefs) regarding their ability to learn (Fig. 4 ).

Goal orientation theory and implicit theories of intelligence. This is a simplified illustration of Dweck's theory; it does not contain all of the details of her theory and blurs some subtle but potentially important distinctions. Learners tend toward one of two implicit self‐theories or mindsets regarding their ability. Those with an entity mindset view ability as fixed, and because low performance or difficult learning would threaten their self‐concept they unconsciously pursue ‘performance’ goals that help them to look smart and avoid failure. By contrast, those with an incremental mindset view ability as something to be enhanced with practice, and thus pursue goals that cause them to stretch and grow (‘mastery’ goals). Evidence and further theoretical refinements also support the distinction of performance‐approach goals (‘look smart’; typically associated with high performance) and performance‐avoidance goals (‘avoid failure’; invariably associated with poor performance)

Learners with performance goals have a (subconscious) self‐theory that intelligence or ability is a stable fixed trait (an ‘entity’ mindset). People are either smart (or good at basketball or art) or they're not. Because this stable trait cannot be changed, learners are concerned about looking and feeling like they have ‘enough’, which requires that they perform well. Easy, low‐effort successes make them feel smarter and encourage continued study; challenging, effortful tasks and poor performance are interpreted as indicating low ability and lead learners to progressively disengage and eventually give up. Learners with this entity mindset magnify their failures and forget their successes, give up quickly in the face of challenge, and adopt defensive or self‐sabotaging behaviours. A strong belief in their ability may lead them to persevere after failure. However, low confidence will cause them to disengage into a ‘helpless’ state because it is psychologically safer to blame failure on lack of effort (‘I wasn't really trying’) than on lack of intelligence. Dweck noted, ‘It is ironic that those students who are most concerned with looking smart may be at a disadvantage for this very reason’. 32

Learners with a mastery goal orientation, by contrast, have a self‐theory that intelligence and ability can increase or improve through learning (an ‘incremental’ mindset). People get smarter (or better at basketball or art) by studying and practising. This mindset leads people to seek learning opportunities because these will make them smarter. They thrive on challenge and even initial failure because they have an implicit ‘No pain, no gain’ belief. In fact, even learners with low confidence in their current ability will choose challenging tasks if they have an incremental mindset. Learners with an incremental mindset feel smart when they fully engage in learning and stretch their ability (the mastery goal orientation); easy tasks hold little or no value and failure is viewed as simply a cue to look for a better strategy and exert renewed effort.

Mindsets are related to the controllability and stability dimensions of attribution theory: entity mindsets lead to attributions of fixed and uncontrollable causes (e.g. ability), whereas incremental mindsets lead to attributions of controllable and changeable causes (e.g. effort). 31 , 35 Mindsets are typically a matter of degree, not black‐and‐white, and appear to be domain and situation specific: a learner might have predominantly entity beliefs about procedural tasks but incremental beliefs about communication skills. Mindsets change with age: young children typically have incremental mindsets, whereas most people have shifted toward entity mindsets by age 12. 32

Researchers building on the work of Dweck and others 33 , 36 , 37 have separated performance goals into those that make the learner look good (performance ‘approach’ goals such as trying to outperform others) and those in which the learner tries to avoid looking bad (performance ‘avoidance’ goals such as avoiding challenging or uncertain tasks). 38 , 39 Empirical results from real‐world settings differ for different outcomes: performance‐approach goals are consistently more associated with higher achievement (e.g. better grades) than are mastery goals, whereas mastery goals are associated with greater interest and deep learning strategies. These empirical observations require further explanation but could reflect shortcomings in mastery‐oriented study strategies (i.e. learners focus on areas of interest rather than studying broadly) or grading systems that favour superficial learning. 40 Performance‐avoidance goals, by contrast, are consistently associated with low achievement and other negative outcomes.

One of the most compelling findings of Dweck's theory is that the incremental mindset is teachable. Randomised trials demonstrate that teaching students that the brain is malleable and has limitless learning capacity leads them to seek more, and more difficult, learning opportunities and to persevere in the face of challenge. 32 The duration of this effect and its transfer to future tasks remain incompletely elucidated.

Unfortunately, the entity mindset also appears to be teachable, or at least unintentionally reinforced by individuals and learning climates that encourage competition, frame abilities as static or praise quick and easy success. Feedback intended to boost a learner's confidence (‘You did really well on that test; you must be really smart!’) may inadvertently encourage an entity mindset. Rather than emphasising innate ability, teachers should instill confidence that anyone can learn if they work at it.

Other motivation theories attempt to explain other aspects of goals, such as goal setting and goal content. 6 , 41 Goal orientation theories focus on the why and how of approach and engagement. Goal setting theories focus on the standard of performance, exploring issues such as goal properties (proximity, specificity and difficulty) and the factors that influence goal choice, the targeted level of performance and commitment. 42 Goal content theories focus on what is trying to be achieved (i.e. the expected consequences). Ford and Nichols 41 developed a content taxonomy of 24 basic goals that they categorised as within‐person goals (e.g. entertainment, happiness and intellectual creativity) and goals dealing with interactions between the person and environment (e.g. superiority, belongingness, equity and safety).

Self‐determination theory

Self‐determination theory (Fig. 5 ) posits that motivation varies not only in quantity (magnitude) but also in quality (type and orientation). Humans innately desire to be autonomous – to use their will (the capacity to choose how to satisfy needs) as they interact with their environment – and tend to pursue activities they find inherently enjoyable. Our highest, healthiest and most creative and productive achievements typically occur when we are motivated by an intrinsic interest in the task. Unfortunately, although young children tend to act from intrinsic motivation, by the teenage years and into adulthood we progressively face external (extrinsic) influences to do activities that are not inherently interesting. These influences, coming in the form of career goals, societal values, promised rewards, deadlines and penalties, are not necessarily bad but ultimately subvert intrinsic motivation. Strong evidence indicates that rewards diminish intrinsic motivation. 43 Deci and Ryan developed self‐determination theory to explain how to promote intrinsic motivation and also how to enhance motivation when external pressures are operative.

Self‐determination theory. This is adapted from Ryan and Deci's theory. Self‐determination theory hypothesises three main motivation types: amotivation (lack of motivation), extrinsic motivation and intrinsic motivation, and six ‘regulatory styles’ (dark‐background boxes). Intrinsic motivation (intrinsic regulation) is entirely internal, emerging from pure personal interest, curiosity or enjoyment of the task. At the other extreme, amotivation (non‐regulation) results in inaction or action without real intent. In the middle is extrinsic motivation, with four regulatory styles that vary from external regulation (actions motivated purely by anticipated favourable or unfavourable consequences) to integrated regulation (in which external values and goals have become fully integrated into one's self‐image). The transition from external to integrated regulation requires that values and goals become internalised (personally important) and integrated (fully assimilated into one's sense of self). Internalisation and integration are promoted (or inhibited) by fulfillment (or non‐fulfillment) of three basic psychosocial needs: relatedness, competence and autonomy

Intrinsic motivation is not caused because it is an innate human propensity, but it is alternatively stifled or encouraged by unfavourable or favourable conditions. Cognitive evaluation theory , a sub‐theory of self‐determination theory, proposes that fulfillment of three basic psychosocial needs will foster intrinsic motivation: autonomy (the opportunity to control one's actions), competence (self‐efficacy) and relatedness (a sense of affiliation with or belonging to others to whom one feels [or would like to feel] connected). Autonomy is promoted by providing opportunities for choice, acknowledging feelings, avoiding judgement and encouraging personal responsibility for actions. Rewards, punishments, deadlines, judgemental assessments and other controlling actions all undermine autonomy. Competence is supported by optimal challenge, and by feedback that promotes self‐efficacy (as outlined above) and avoids negativity. Relatedness is promoted through environments exhibiting genuine caring, mutual respect and safety.

In activities motivated by external influences, both the nature of the motivation and the resultant performance vary greatly. The motivation of a medical student who does his homework for fear of punishment is very different from motivation to learn prompted by a sincere desire to provide patients with optimal care. Deci and Ryan proposed that these qualitative differences arise because of differences in the degree to which external forces have been internalised and integrated (assimilated into the individual's sense of self). A second sub‐theory, organismic integration theory, explains these differences.

Organismic integration theory identifies three regulatory styles: intrinsic motivation at one extreme (highly productive and spontaneous), amotivation at the other extreme (complete lack of volition, failure to act or only going through the motions) and extrinsic motivation in between (actions prompted by an external force or regulation). Extrinsic motivation is divided, in turn, into four levels that vary in the degree to which the external regulation has been internalised (taking in a value or regulation) and integrated (further transformation of that regulation into their own self). 44 , 45 The lowest level is external regulation: acting only to earn rewards or avoid punishment. Next is introjected regulation: acting to avoid guilt or anxiety, or to enhance pride or self‐esteem. The regulation has been partially internalised but not accepted as a personal goal. Identified regulation suggests that the external pressure has become a personally important self‐desired goal, but the goal is valued because it is useful rather than because it is inherently desirable. Finally, with integrated regulation the external influences are integrated with internal (intrinsic) interests, becoming part of one's personal identity and aspirations. Regulatory forces with identified and integrated regulation reflect an internal locus of causality (control) and behaviours are perceived as largely autonomous or self‐determined, whereas both external and introjected regulation reflect an external locus of causality. ‘Thus, it is through internalisation and integration that individuals can be extrinsically motivated and still be committed and authentic.’ 45 Research suggests that the same three psychosocial needs described above promote the internalisation and integration of extrinsic motivations, with relatedness and competence being particularly important for internalisation, and autonomy being critical for integration.

Because optimal motivation and well‐being require meeting all three needs, ‘Social contexts that engender conflicts between basic needs set up the conditions for alienation and psychopathology’. 45 The importance of these needs has been confirmed not only in education, but also in workplace performance, patient compliance and overall health and well‐being. 46

Integration across theories

Over the past 25 years, contemporary motivation theories have increasingly shared and borrowed key concepts. 17 For example, all five theories discussed herein acknowledge human cognition as influencing perceptions and exerting powerful motivational controls. All also highlight reciprocal interactions between individuals and their socio‐environmental context. Definitions of expectancy have evolved to reflect substantial overlap with self‐efficacy. Attribution theory emerged from earlier expectancy‐value theories in an effort to explain the origins and antecedents (the ‘Why?’) of expectancies and values, ultimately emphasising the temporal sequence of events and the importance of emotions. Goal orientation theory merged early goal theories with the concept of implicit attributions. Self‐determination theory emphasises both autonomy (locus and control in attribution theory) and competence (very similar to self‐efficacy). With this conceptual overlap, it is easy to get confused with the terms as operationally defined within each theory. Table 2 attempts to clarify these areas of potential confusion.

Through this effort we have identified four recurrent themes among contemporary theories: competence beliefs, value beliefs, attribution and social‐cognitive interactions. We do not suggest that these theories can be reduced to these four concepts, but that these foundational principles underpin a more nuanced understanding of individual theories. Research conducted using one theoretical framework might also yield insights relevant to another.

Given the progressive blurring of boundaries and increasing conceptual overlap, can – or should – we ever achieve a grand unified theory of motivation? We note that each theory shines light on a different region of a larger picture, and thus contributes a unique perspective on a complex phenomenon involving individual learners and varying social contexts, topics and outcomes. Moreover, despite our and others’ efforts 7 , 47 to clarify terminology, conceptual differences among theories run much deeper than dictionary definitions can resolve. Even within a given theoretical domain, different investigators have operationally defined concepts and outcome measures with subtle but important distinctions that lead to vastly different conclusions. 31 , 37 , 39 The degree to which these differences can be both theoretically and empirically reconciled remains to be seen. 17 For now, we encourage maintaining theoretical distinctions while thoughtfully capitalising on overlapping concepts and explicit theoretical integrations for the enrichments they afford.

Implications and conclusions

Other authors have identified practical applications of motivation theory, most often instructional changes that could enhance motivation. 3 , 4 , 6 , 16 , 32 In Table S1 (available online) we provide a short summary of these suggestions, nearly all of which warrant investigation in health professions education. Educators and researchers will need to determine whether to apply these and other interventions to all learners (i.e. to improve the overall learning environment and instructional quality) or only to those with specific motivational characteristics (e.g. low self‐efficacy, entity mindsets, maladaptive attributions or external motivations). 17 , 48 , 49

We will limit our further discussion to considerations for future research. Pintrich 50 identified seven broad questions for motivation research and suggested general research principles for investigating these questions; we summarise these in Table S2 (available online). By way of elaboration or emphasis, we conclude with four broad considerations that cut across theoretical and methodological boundaries.

First, motivation is far from a unitary construct. This may seem obvious, yet both lay educators and researchers commonly speak of ‘motivation’ without clarity regarding a specific theory or conceptual framework. Although different theories rarely contradict one another outright, each theory emphasises different aspects of motivation, different stages of learning, different learning tasks and different outcomes. 17 , 19 , 51 To avoid conceptual confusion and to optimise the theory‐building potential of their work, we encourage researchers to explicitly identify their theoretical lens, to be precise in defining and operationalising different motivational constructs, and to conduct a careful review of theory‐specific literature early in their study planning.

Second, measuring the outcomes of motivation studies is challenging for at least two reasons: the selection of which outcomes (psychological constructs) to measure and the choice of specific instruments to measure the selected outcomes. The choice of outcomes and instruments, and the timing of outcome assessment, can significantly influence study results. For instance, results (and thus conclusions) for mastery and performance‐approach goal orientations vary for different outcomes. 39 Schunk identified four general motivation outcomes (choice of tasks, effort, persistence and achievement) and suggested tools for measuring each of these. 6 Learners can also rate how motivating they perceive a course to be. 52 The outcome(s) most relevant to a given study will depend on the theory and the research question. In turn, for each outcome there are typically multiple measurement approaches and specific instruments, each with strengths and limitations. For example, behaviour‐focused measures diminish the importance of cognitive processes, whereas self‐report measures are limited by the accuracy of self‐perceptions. For all instruments, evidence to support the validity of scores should be deliberately planned, collected and evaluated. 53 , 54

Third, researchers should test clear, practical applications of motivation theory. 50 , 55 , 56 Each of the theories discussed above has empirical evidence demonstrating theory‐predicted associations between a predictor condition (e.g. higher versus lower expectancy of success) and motivation‐related outcomes, but the cause‐effect relationship in these studies (often correlational rather than experimental) is not always clear. Moreover, the practical significance of the findings is sometimes uncertain; for example, does a change in the outcome measure reflect a meaningful and lasting change in the learner, or is it merely an artifact of the study conditions? Well‐planned experiments can strengthen causal links between motivational manipulations and outcomes. 57 We can find examples of interventions intended to optimise self‐efficacy, 28 task value, 5 attributions 17 and mindsets, 32 but research on motivational manipulations remains largely limited in both volume and rigour. 17 Moreover, moderating influences such as context (e.g. classroom, clinical or controlled setting) and learner experience or specialty can significantly impact results. Linking motivational concepts with specific cognitive processes may be instrumental in understanding seemingly inconsistent findings. 17 , 39 Finally, real‐world implementations of research‐based recommendations may be challenged by resource limitations, logistical constraints or lack of buy‐in from administrators and teachers; research on translation and implementation will be essential. 58

Lastly, we call for research that builds and extends motivation theory for education generally 50 and health professions education specifically. Theory‐building research should investigate ‘not only that the intervention works but also why it works (i.e., mediating mechanisms) as well as for whom and under what conditions (i.e., moderating influences)’. 17 Such research not only specifies the theoretical lens, interventions and outcomes, but also considers (and ideally predicts) how independent and dependent variables 2 interact with one another and with the topic, task, environment and learner characteristics. 59 Harackiewicz identified four possible relationships and interactions among motivation‐related variables:

- additive (different factors have independent, additive effects on a single outcome),

- interactive (different factors have complex effects on a single outcome),

- specialised (the impact of a given intervention varies for different outcomes) and

- selective (outcomes for a given intervention vary by situation, e.g. context or topic). 39

We encourage would‐be investigators to further explore theory‐specific literatures to understand conceptual nuances, current evidence, potential interactions, important outcomes and timely questions. 47 , 60

Only research grounded in such solid foundations will provide the theoretical clarity and empirical support needed to optimise motivation to learn in health professions education.

Contributors

DAC and ARA jointly contributed to the conception of the work, drafted the initial manuscript, revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final version. ARA is an employee of the US Government. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of Defense, nor the US Government.

Conflicts of interest

the authors are not aware of any conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval

as no human subjects were involved, ethical approval was not required.

Supporting information

Table S1. Summary of practical applications of motivation theory.

Acknowledgments

we thank Kelly Dore for her contributions during the conceptual stages of this review and Adam Sawatsky and Dario Torre for their critiques of manuscript drafts.

The copyright line for this article was changed on 6 October 2016 after original online publication.

Advertisement

Can learning motivation predict learning achievement? A case study of a mobile game-based English learning approach

- Published: 10 October 2016

- Volume 22 , pages 2159–2173, ( 2017 )

Cite this article

- Chia-Hui Tsai 1 ,

- Ching-Hsue Cheng 2 ,

- Duen-Yian Yeh 3 &

- Shih-Yun Lin 2

3106 Accesses

26 Citations

Explore all metrics

This study applied a quasi-experimental design to investigate the influence and predictive power of learner motivation for achievement, employing a mobile game-based English learning approach. A system called the Happy English Learning System, integrating learning material into a game-based context, was constructed and installed on mobile devices to conduct the experiment. The sample comprised 38 Taiwanese vocational high school students. The experimental period was 8 weeks. Through statistical methods, the results verified the positive effectiveness of the approach for promoting student English learning motivation and achievement, indicating the partially predictive power of student learning motivation on English achievement. Notably, the results evidenced the necessity of a long experimental period and sufficient external stimulation to enhance student learning effectiveness. Finally, this study proposed several positive suggestions for English learning and teaching in Taiwan vocational education.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Adoption of online mathematics learning in Ugandan government universities during the COVID-19 pandemic: pre-service teachers’ behavioural intention and challenges

Geofrey Kansiime & Marjorie Sarah Kabuye Batiibwe

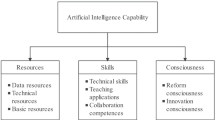

Effects of higher education institutes’ artificial intelligence capability on students' self-efficacy, creativity and learning performance

Shaofeng Wang, Zhuo Sun & Ying Chen

The Gamification of Learning: a Meta-analysis

Michael Sailer & Lisa Homner

Bandura, A. (1994). Social cognitive theory and the exercise of control over HIV infection. In R. DiClemente & J. Pererson (Eds.), Preventing AIDS: Theories and methods of behavioral interventions (pp. 25–59). New York: Plenum.

Chapter Google Scholar

Cavus, N., & Ozdamli, F. (2011). Basic elements and characteristics of mobile learning. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28 , 937–942.

Article Google Scholar

Cerasoli, C. P., Nicklin, J. M., & Ford, M. T. (2014). Intrinsic motivation and extrinsic incentives jointly predict performance: A 40-year meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin . doi: 10.1037/a0035661 .Accessed 29 Oct 2015

Google Scholar

Chen, C. M., & Chung, C. J. (2008). Personalized mobile English vocabulary learning system based on item response theory and learning memory cycle. Computers & Education, 51 (2), 624–645.

Cheng, C. H., & Su, C. H. (2012). A game-based learning system for improving student’s learning effectiveness in system analysis course. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 31 , 669–675.

Connolly, T. M., Stansfield, M., & Hainey, T. (2011). An alternate reality game for language learning: ARGuing for multilingual motivation. Computers & Education, 57 (1), 1389–1415.

Connolly, T. M., Boyle, E. A., MacArthur, E., Hainey, T., & Boyle, J. M. (2012). A systematic literature review of empirical evidence on computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 59 (2), 661–686.

Deng, L. J., & Hu, H. P. (2007). Vocabulary acquisition in multimedia environment. US-China Foreign Language, 5 (8), 55–59.

Duncan, T. G., & McKeachie, W. J. (2005). The making of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire. Educational Psychologist, 40 , 117–128.

Dweck, C., & Leggett, E. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95 (2), 256–273.

Feng, H.-Y., Fan, J.-J., & Yang, H.-Z. (2013). The relationship of learning motivation and achievement in EFL: Gender as an intermediated variable. Educational Research International, 2 (2), 50–58.

Fowler, R. L. (1992). Using the extreme groups strategy when measures are not normally distributed. Applied Psychological Measurement, 16 , 249–259.

Girard, C., Ecalle, J., & Magnan, A. (2012). Serious games as new educational tools: How effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 28 (6), 1–13.

Hays, R. T. (2005). The effectiveness of instructional games: A literature review and discussion . Orlando: Naval Air Warfare Center Training Division http://www.dtic.mil/cgi-bin/GetTRDoc?AD=ADA441935 . Accessed 29 Oct 2006.

Book Google Scholar

Huang, Y.-M., Huang, Y.-M., Huang, S.-H., & Lin, Y.-T. (2012). A ubiquitous English vocabulary learning system: Evidence of active/passive attitudes vs. usefulness/ease-of-use. Computers & Education, 58 , 273–282.

Hwang, G. J., Sung, H. Y., Hung, C. M., & Huang, I. (2012). Development of a personalized educational computer game based on students’ learning styles. Educational Technology Research & Development, 60 (4), 623–638.

Hwang, W. Y., Shih, T. K., Ma, Z. H., & Shadiev, R. (2016). Evaluating listening and speaking skills in a mobile game-based learning environment with situational contexts. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 29 (4), 639–657.

Kavita, K. S. (2014). Motivational beliefs and academic achievement of university students. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4 (1), 1–3.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development . Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall Inc..

Kukulska-Hulme, A. (2005). The mobile language learner- Now and in the future . Fran vision till praktik. language learning symposium conducted at umea university in sweden. http://www2.humlab.umu.se/symposium2005/program.htm . Accessed 19 May 2006.

Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Shield, L. (2008). An overview of mobile assisted language learning: From content delivery to supported collaboration and interaction. ReCALL, 20 (3), 271–289.

Lan, Y. J., Sung, Y. T., & Chang, K. E. (2007). A mobile-device-supported peer assited learning system for collaborative early EFL reading. Language, Learning and Technology, 11 (3), 130–151.

Liu, T. Y., & Chu, Y. L. (2010). Using ubiquitous games in an English listening and speaking course: Impact on learning outcomes and motivation. Computers & Education, 55 (2), 630–643.

Miller, L. M., Chang, C.-I., Wang, S., Beier, M. E., & Klisch, Y. (2011). Learning and motivational impacts of a multimedia science game. Computers & Education, 57 (1), 1425–1433.

Noels, K. A., Pelletier, L. G., Clément, R., & Vallerand, R. J. (2000). Why are you learning a second language? Motivational orientations and self-determination theory. Language Learning, 50 , 57–85.

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Pajares, M., & Graham, L. (1999). Self-efficacy motivation contrusts and math performance of entering middle school students. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24 , 124–139.

Palomo-Duarte, M., Berns, A., Cejas, A., Dodero, J. M., Caballero, J. A., & Ruiz-Rube, I. (2016). Assessing foreign language learning through mobile game-based learning environments. International Journal of Human Capital and Information Technology Professionals, 7 (2), 53–67.

Papastergiou, M. (2009). Digital game-based learning in high school computer science education: Impact on educational effectiveness and student motivation. Computers & Education, 52 (1), 1–12.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 , 667–686.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Garcia, T., & Mckeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionnaire (MSLQ) . Ann Arbor: National Center for Research to Improve Teaching and Learning, School of Education, The University of Michigan.

Prensky, M. (2001). Fun, play, and games: What makes games engaging. In Digital game-based learning (pp. 11–16). New York: McGraw Hill.

Rollings, A., & Morris, D. (2004). Game architecture and design . Berkeley: New Riders.

Sandberg, J., Maris, M., & de Geus, K. (2011). Mobile English learning: An evidence-based study with fifth graders. Computers & Education, 57 (1), 1334–1347.

Schunk, D. (1991). Self-efficacy and academic motivation. Educational Psychologist, 26 (3, 4), 207–231.

Shiratuddin, N., Zaibon, S. B. (2011). Designing user experience for mobile game-based learning. 2011 International Conference on User Science and Engineering , 89–94. 29 Nov. - 01 Dec. 2011, Selangor, Malaysia.

Smith, G. G., Li, M., Drobisz, J., Park, H. R., Kim, D., & Smith, S. D. (2013). Play games or study? Computer games in eBooks to learn English vocabulary. Computers & Education, 69 , 274–286.

Thornton, P., & Houser, C. (2005). Using mobile phones in English education in Japan. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 21 , 217–228.

Tsau, C. C., & Hao, C. H. (2010). The influence of the elementary students’ early English learning experience on their English motivation and academic achievements. Journal of Educational Practice and Research, 23 (2), 95–124.

VanZile-Tamsen, C., & Livingston, J. (1999). The differential impact of motivation on the selfregulated strategy use of high- and low-achieving college students. Journal of College Student Development, 40 (1), 54–60.

Wouters, P., van Nimwegen, C., van Oostendorp, H., & van der Spek, E. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of the cognitive and motivational effects of serious games. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105 (2), 249–265.

Yang, W., & Dai, W. (2011). Rote memorization of vocabulary and vocabulary development. English Language Teaching, 4 (4), 61–64.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sport and Health Promotion, Transworld University, 1221, Zhennan Rd., Douliu, Yunlin County, 64063, Taiwan

Chia-Hui Tsai

Department of Information Management, National Yunlin University of Science & Technology, 123 University Rd., Section 3, Douliou, Yunlin, 640, Taiwan

Ching-Hsue Cheng & Shih-Yun Lin

Department of Information and Electronic Commerce Management, Transworld University, 1221, Zhennan Rd., Douliu, Yunlin, 64063, Taiwan

Duen-Yian Yeh

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ching-Hsue Cheng .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tsai, CH., Cheng, CH., Yeh, DY. et al. Can learning motivation predict learning achievement? A case study of a mobile game-based English learning approach. Educ Inf Technol 22 , 2159–2173 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9542-5

Download citation

Published : 10 October 2016

Issue Date : September 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-016-9542-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Mobile learning

- Game-based learning

- English learning

- Vocational education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- LOGIN & Help

A Case Study of Learning, Motivation, and Performance Strategies for Teaching and Coaching CDE Teams

Research output : Contribution to journal › Article › peer-review

- Career Development Events

- CDE preparation

- learning strategies

- motivational strategies

- performance strategies

- teaching and coaching

- teacher behaviors

- coaching strategies

Online availability

- 10.5032/jae.2016.03115

Library availability

Fingerprint.

- learning strategy Social Sciences 89%

- event Social Sciences 54%

- Teaching Social Sciences 41%

- teacher Social Sciences 32%

- extrinsic motivation Social Sciences 24%

- student Social Sciences 23%

- intrinsic motivation Social Sciences 20%

- coach Social Sciences 18%

T1 - A Case Study of Learning, Motivation, and Performance Strategies for Teaching and Coaching CDE Teams

AU - Ball, Anna

AU - Bowling, Amanda

AU - Bird, Will

N2 - This intrinsic case study examined the case of students on CDE (Career Development Event) teams preparing for state competitive events and the teacher preparing them in a school with a previous exemplary track record of winning multiple state and national career development events. The students were interviewed multiple times during the 16-week preparation period before, during, and after the district and state CDEs. From the interview data it was found the teacher used a variety of motivational strategies when preparing CDE teams. The teacher shifted the use of both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation strategies based on students' needs. The teacher also utilized performance strategies including both coaching and learning strategies, to develop students' competitive drive and content knowledge. From the findings it is recommended that CDE coaches assess students' needs and utilize the successful coaching behaviors and strategies accordingly.

AB - This intrinsic case study examined the case of students on CDE (Career Development Event) teams preparing for state competitive events and the teacher preparing them in a school with a previous exemplary track record of winning multiple state and national career development events. The students were interviewed multiple times during the 16-week preparation period before, during, and after the district and state CDEs. From the interview data it was found the teacher used a variety of motivational strategies when preparing CDE teams. The teacher shifted the use of both extrinsic and intrinsic motivation strategies based on students' needs. The teacher also utilized performance strategies including both coaching and learning strategies, to develop students' competitive drive and content knowledge. From the findings it is recommended that CDE coaches assess students' needs and utilize the successful coaching behaviors and strategies accordingly.

KW - Career Development Events

KW - CDE preparation

KW - learning strategies

KW - motivational strategies

KW - performance strategies

KW - teaching and coaching

KW - teacher behaviors

KW - coaching strategies

U2 - 10.5032/jae.2016.03115

DO - 10.5032/jae.2016.03115

M3 - Article

SN - 1042-0541

JO - Journal of Agricultural Education

JF - Journal of Agricultural Education

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Infographic

Difficult Conversations: Common Mistakes Infographic

Infographic Transcript

Expert Interviews

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Team Management

Learn the key aspects of managing a team, from building and developing your team, to working with different types of teams, and troubleshooting common problems.

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

SWOT Analysis

How to Build a Strong Culture in a Distributed Team

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Top tips for delegating.

Delegate work to your team members effectively with these top tips

Ten Dos and Don'ts of Change Conversations

Tips for tackling discussions about change

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Beyonder creativity.

Moving From the Ordinary to the Extraordinary

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .