Peer Observation as a Collaborative Vehicle for Innovation in Incorporating Educational Technology into Teaching

A Case Study

Cite this chapter

- Sven Venema 4 ,

- Steve Drew 5 &

- Jason M. Lodge 6 , 7

Part of the book series: Professional Learning ((PROFL))

1565 Accesses

2 Citations

We provide a case study using peer review and observation of teaching (PRO-Teaching) as a vehicle to develop both a scholarly approach to teaching as well as providing a framework to gather data for ongoing change to facilitate scholarship of learning and teaching.

- Content Knowledge

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge

- Student Engagement

- Student Perception

- Blended Learning

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development, 34 (1), 1–14.

Article Google Scholar

Becher, T., & Trowler, P. (2001). Academic tribes and territories: Intellectual enquiry and the culture of disciplines . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill International.

Google Scholar

Bell, M. (2001). Supported reflective practice: A programme of peer observation and feedback for academic teaching development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6 (1), 29–39.

Berk, R. A. (2005). Survey of 12 strategies to measure teaching effectiveness. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 17 (1), 48–62.

Biggs, J. B. (2003). Teaching for quality learning at university: What the student does (2nd ed.). Buckingham, England, Philadelphia, PA: Society for Research into Higher Education: Open University Press.

Bligh, D. (1998). What’s the use of lectures? (5th ed.). Exeter, England: Intellect.

Brinko, K. T. (1993). The practice of giving feedback to improve teaching: What is effective? The Journal of Higher Education, 64 (5), 574–593.

Buchbinder, S. B., Alt, P. M., Eskow, K., Forbes, W., Hester, E., Struck, M., & Taylor, D. (2005). Creating learning prisms with an interdisciplinary case study workshop. Innovative Higher Education, 29 (4), 257–274.

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and student learning: Testing the linkages. Research in Higher Education, 47 (1), 1–32.

Donnelly, R. (2007). Perceived impact of peer observation of teaching in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 19 (2), 117–129.

Drew, S., & Klopper, C. (2013). PRO-Teaching – Sharing ideas to develop capabilities . Paper presented at the International Conference on Higher Education 2013, Paris, France. Retrieved from http://www.waset.org/journals/waset/v78/v78-297.pdf

Goodyear, P. (2005). Educational design and networked learning: Patterns, pattern languages and design practice. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 21 (1), 82–101.

Goodyear, P., & Ellis, R. A. (2008). University students’ approaches to learning: Rethinking the place of technology. Distance Education, 29 , 141–152.

Gudmundsdottir, S., & Shulman, L. S. (1987). Pedagogical content knowledge in social studies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 31 (2), 59–70.

Harris, J., Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2009). Teachers’ technological pedagogical content knowledge and learning activity types: Curriculum-based technology integration reframed. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 41 (4), 393–416.

Harris, K., L., Farrell, K., Bell, M., Devlin, M., & James, R. (Eds.). (2008). Peer review of teaching in australian higher education: A handbook to support institutions in developing effective policies and practices . Melbourne, Australia: Centre for the Study of Higher Education, Melbourne University.

Iribe, Y., Nagaoka, H., Kouichi, K., & Nitta, T. (2010). Web-based lecture system using slide sharing for classroom questions and answers . International Journal of Knowledge and Web Intelligence, 1 (3), 243–255.

Kember, D. (2000). Action learning and action research: Improving the quality of teaching and learning . London, England: Kogan Page.

Kiewra, K. A. (1985). Investigating notetaking and review: A depth of processing alternative. Educational Psychologist, 20 , 23–32.

Koehler, M. J., & Mishra, P. (2005). What happens when teachers design educational technology? The development of technological pedagogical content knowledge. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 32 (2), 131–152.

Koehler, M., & Mishra, P. (2009). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 9 (1), 60–70.

Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Kereluik, K., Shin, T. S., & Graham, C. R. (2014). The technological pedagogical content knowledge framework. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. Elan, & M. J. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology . New York, NY: Springer.

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of educational technology (2nd ed.). London, England: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Lodge, J. M., & Bonsanquet, A. (2014). Evaluating quality learning in higher education: Re-examining the evidence. Quality in Higher Education, 20 (1), 3–23.

Lomas, L., & Nicholls, G. (2005). Enhancing teaching quality through peer review of teaching. Quality in Higher Education, 11 (2), 137–149.

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. The Teachers College Record, 108 (6), 1017–1054.

Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., & Henriksen, D. (2010). The 7 trans-disciplinary habits of mind: Extending the TPACK framework towards 21st century learning. Educational Technology, 51 (2), 22–28.

Moore, J. L., Dickson-Deane, C., & Galyen, K. (2011). E-Learning, online learning, and distance learning environments: Are they the same? The Internet and Higher Education, 14 (2), 129–135.

Race, P. (2007). The lecturer’s toolkit (3rd ed.). London, England: Routledge.

Schmidt, D. A., Baran, E., Thompson, A. D., Mishra, P., Koehler, M. J., & Shin, T. S. (2009). Technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) the development and validation of an assessment instrument for preservice teachers. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 42 (2), 123–149.

Scott, R. H. (2011). Tableau economique: Teaching economics with a tablet computer. The Journal of Economic Education, 42 , 175–180.

Shin, T., Koehler, M., Mishra, P., Schmidt, D., Baran, E., & Thompson, A. (2009). Changing technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK) through course experiences . Paper presented at the Society for Information Technology & Teacher Education International Conference 2009, Charleston, SC, USA. Retrieved from http://www.editlib.org/p/31309

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15 (2), 4–14.

Tinto, V. (1993). Leaving college : Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition (2nd ed.). Chicago, IL; London, England: University of Chicago Press.

Venema, S., & Lodge, J. M. (2012). Improving first year first semester lecture engagement. 15th First Year in Higher Education (FYHE) Conference, Brisbane, Australia.

Venema, S., & Lodge, J. M. (2013a). Capturing dynamic presentation: Using technology to enhance the chalk and the talk. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology , 29 (1).

Venema, S., & Lodge, J. M. (2013b). A quasi-experimental comparison of assessment feedback mechanisms . Poster presentation, ASCILITE.

Venema, S., & Rock, A. (2014). Improving learning outcomes for first year introductory programming students . 17th First Year in Higher Education (FYHE) Conference, Darwin, Australia.

Zimitat, C. (2006). First year students’ perceptions of the importance of good teaching: Not all things are equal. Proceedings of HERDA 2006 , 386–392 .

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Information and Communication, Griffith University, Australia

Sven Venema

Griffith Sciences, Griffith University, Australia

ARC Science of Learning Research Centre, Australia

Jason M. Lodge

Melbourne Centre for the Study of Higher Education, University of Melbourne, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Griffith University, Australia

Christopher Klopper

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2015 Sense Publishers

About this chapter

Venema, S., Drew, S., Lodge, J.M. (2015). Peer Observation as a Collaborative Vehicle for Innovation in Incorporating Educational Technology into Teaching. In: Klopper, C., Drew, S. (eds) Teaching for Learning and Learning for Teaching. Professional Learning. SensePublishers, Rotterdam. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-289-9_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-289-9_13

Publisher Name : SensePublishers, Rotterdam

Online ISBN : 978-94-6300-289-9

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 04 May 2012

Peer observation of teaching as a faculty development tool

- Peter B Sullivan 1 ,

- Alexandra Buckle 1 ,

- Gregg Nicky 1 &

- Sarah H Atkinson 1

BMC Medical Education volume 12 , Article number: 26 ( 2012 ) Cite this article

23k Accesses

61 Citations

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Peer observation of Teaching involves observers providing descriptive feedback to their peers on learning and teaching practice as a means to improve quality of teaching. This study employed and assessed peer observation as a constructive, developmental process for members of a Pediatric Teaching Faculty.

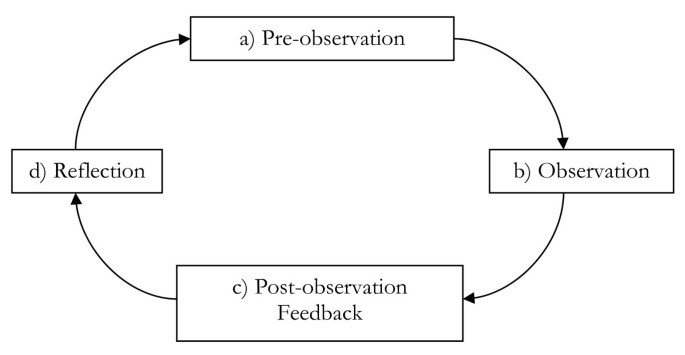

This study describes how peer observation was implemented as part of a teaching faculty development program and how it was perceived by teachers. The PoT process was divided into 4 stages: pre-observation meeting, observation, post-observation feedback and reflection. Particular care was taken to ensure that teachers understood that the observation and feedback was a developmental and not an evaluative process. Twenty teachers had their teaching peer observed by trained Faculty members and gave an e-mail ‘sound-bite’ of their perceptions of the process. Teaching activities included lectures, problem-based learning, small group teaching, case-based teaching and ward-based teaching sessions.

Teachers were given detailed verbal and written feedback based on the observer’s and students’ observations. Teachers’ perceptions were that PoT was useful and relevant to their teaching practice. Teachers valued receiving feedback and viewed PoT as an opportunity for insight and reflection. The process of PoT was viewed as non-threatening and teachers thought that PoT enhanced the quality of their teaching, promoted professional development and was critical for Faculty development.

Conclusions

This study demonstrated that PoT can be used in a constructive way to improve course content and delivery, to support and encourage medical teachers, and to reinforce good teaching.

Peer Review reports

The General Medical Council which regulates medical practice in the United Kingdom has, in its 2009 report ‘Tomorrow’s Doctors’, set the standards that it will use to judge the quality of undergraduate teaching and assessments in individual medical schools. Two quotations from this report give indications of this which are relevant to the present paper:

"‘Everyone involved in educating medical students will be appropriately selected, trained, supported and appraised’" "‘The medical school must ensure that appropriate training is provided…and that staff development programmes promote teaching and assessment skills’"

The aim of this study was to address both of these issues within the context of an undergraduate pediatric course. As part of an ongoing process of course and faculty development a peer observation of teaching (PoT) process was offered as a developmental opportunity for members of the teaching Faculty.

PoT involves observers providing descriptive feedback to their peers on learning and teaching practice [ 1 ] and can be seen as a means by which the quality of teaching and learning process in higher education establishments is both accounted for and improved [ 2 ]. PoT has attracted increasing attention in higher education in recent years. This arises, in part, to help prepare for internal or external audit of teaching as, for instance, in HEFCE-driven assessments of university teaching and is also partly a reflection of the awareness of the need to foster teacher development and professional growth and to adapt to the changing demands of the higher education system [ 3 ].

A consequence of these two drivers is the potential for confusion or conflict about the role of the observer. On the one hand, with evaluation and audit-driven process there is the possibility that observation may acquire a threatening, confrontational dimension, which may alienate the teacher. On the other hand, and probably depending in large measure on how it is approached, the peer observation process may be perceived by the teacher as a constructive, developmental adjunct to their teaching, which improves opportunities for student learning.

In view of this possible controversy, there is a need for clear focus and goals: ‘we should be very clear about exactly what our objectives are for the implementation of peer observation, and the best way to achieve these, before espousing a potentially divisive and detrimental procedure’ [ 3 ]. Shortland states that ‘an inappropriate choice of methodology – may lead to de-motivating feedback, presenting a dilemma within observation practice’ [ 1 ]. This is obviously a major concern and one that is not only represented in the literature, but in actual practice. At its worst, the aims of this exercise introduce ‘conflict’ in a system that is meant to inspire ‘confidence, enthusiasm and a sense of professional worth’ [ 3 ]. As one case report states: ‘Peer observation was designed to meet the twin aims of teacher development and quality assurance. Teachers’ views suggest these two aims may conflict’ [ 4 ].

Ramsden points out that ‘there can be no single right answer to the problem of improving the quality of university teaching’ [ 5 ]. If peer observation feedback is to achieve its goal of being motivating and helping people to learn [ 5 ], then it must be remembered that it is not an ‘automatic recipe for enhanced learning and development’ [ 1 ]. However, research unequivocally indicates that ‘classroom observation methodologies…can provide a different perspective on the observation process and thus play a part in developing observers as reflective practitioners of teaching and learning’ [ 1 ]. Irrespective of the reason for observation of teaching, it is imperative that the process is conducted in a structured and managed fashion. As Fullerton observes, ‘The aim of the observation is to help improve the skills of the observed, therefore quality feedback is essential’ [ 6 ].

Despite a large literature on PoT, there are few accounts of its implementation in clinical teaching [ 7 ] and as far as we are aware no accounts of clinical teachers’ perceptions of PoT. The aims of this project were firstly to implement PoT methods as a constructive, developmental process for members of the Pediatric Teaching Faculty and secondly to assess teachers’ perceptions of the PoT process. Our overall aim was to improve opportunities for student learning in pediatrics in our institution.

Peer observation was undertaken by Faculty members (PBS and SHA) with specific training in PoT provided by a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy with specialist knowledge of PoT. There was one-to-one training in the techniques involved followed by peer observation of trainee observers’ teaching. Our 8 week pediatric course is presented 6 times a year with the ensuing danger of becoming mechanical and stale. We therefore assessed that there was a need for PoT to keep our course material and lectures up to date and to affirm the efforts of our teaching Faculty. Critically, and this was emphasized to teaching Faculty, the PoT process was developed to be constructive and developmental. As discussed in the literature [ 1 ], an inappropriate methodology might lead to de-motivating feedback and would not achieve our aim of improving student learning.

Between October 2008 and January 2011, 15 Consultants (by PBS), 3 Clinical Lecturers and 2 Specialist Registrars (by SHA) were peer observed. Only 4 Consultants regularly contributing to the undergraduate course declined the invitation. The reasons given for declining were: from the most senior (n = 2) “not necessary”; from the most junior “too busy” and the fourth misunderstood the process and has subsequently agreed to participate. The teaching activities observed included 10 lectures, 2 problem-based teaching sessions, 3 small group teaching activities, 3 case-based teaching sessions and 2 ward-based teaching rounds. The teaching sessions were generally about one hour long. The pre-observation meeting generally took between 15 and 20 minutes and the post-observation feedback about 25–30 minutes. Each observation therefore took about 2 hours.

The general approach that was adopted for peer observation of teaching was based on Bell’s model [ 8 ]. Figure 1 illustrates the cyclical nature of the process.

Peer Observation Process (Bell 2002, [ 8 ] ]).

This approach will now be discussed under these four sub-headings:

· Pre-observation meeting

· Observation

· Post observation feedback

· Reflection

Pre-observation meeting

Prior to the observations, a pre-observation meeting was held to clarify the process and enquire of the teacher what they required from the review and to establish the context of the teaching event. Topics covered at this meeting were;

· Context of the teaching; how the session fits into the course

· The content and its place within the curriculum of the unit and the programme of study

· To what extent is this session relied upon to deliver teaching on the whole topic

· Identify specific learning objectives for this session

· Teaching approach to be adopted, anticipated student activities, time plan for the session

· Any potential difficulties or areas of concern

· Any particular aspects that the tutor wishes to have observed

· How the observation is to be conducted

· The way in which the students will be informed and incorporated into the observation

· Any particular concerns that either the observer or the observed might have about undertaking the observation.

This pre-observation meeting is an essential component in establishing a ‘contract’ with the teacher to underline that this is intended to be a developmental exercise and not an evaluative/assessment process [ 9 ].

Observation

During the observation notes were taken on the content, style and delivery of the teaching and these were used to inform the post observation feedback. With the teacher’s approval a short questionnaire scored with a Likert scale and with space for free text comments (Additional file 1 : Appendix 1) was administered to the students at the end of each observed session. The purpose of this was to help validate any observation made by the observer.

Post observation feedback

The model of feedback for each peer observation was broadly based on the revised Pendleton rules [ 10 ]. The purpose of giving feedback has been well summarized by King (1999), ‘Giving feedback is not just to provide a judgment or evaluation… It is to provide insight’ [ 11 ]. If feedback is to be effective certain criteria must be met. Feedback should be:

· Descriptive - of the behavior rather than the personality

· Specific - rather than general

· Sensitive - to the needs of the receiver as well as the giver

· Directed - towards behavior that can be changed

· Timely - given as close to the event as possible

· Selective - addressing one or two key issues rather than too many at once

At the end of the feedback session the observer and the observee examined and discussed the results of the student questionnaire. Potential solutions to any concerns raised were collaboratively identified and discussed by the observer and observee. Each teacher received a letter providing a written summary of the outcome of the observation process assimilating both the observer’s comments and the students’ comments together with potential solutions to any concerns raised.

An important component of peer observation is the opportunity for teachers to reflect on their teaching in the light of feedback from observation. All participants were invited to reflect on their observation and to send an email with comments on their experience of the process and what, if any, value it had for them as teachers. This informal approach was considered to be more likely to achieve a response rather than any structured or formal approach such as using a questionnaire.

Data analysis

Reflective feedback from the teaching faculty on PoT was analyzed using qualitative methods. Key themes in the data were identified and content analysis was carried out via systematic coding using NVivo Version 9 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Australia). Data were analyzed using a grounded theory approach [ 12 ] with constant comparison. The use of direct quotation gave additional richer perspectives on how, when and why certain observations were made [ 13 ].

Post-PoT recommendations

Observation of teaching activities provided an opportunity to examine both content and delivery of individual course components so that suggestions could be made as to how these might be improved or refined. Some examples of these post-PoT recommendations to individual teachers are listed:

· Ensure that learning objectives for the session are defined

· Refinement of slides by updating old slides and removing unnecessary ones

· Embed video clips in PowerPoint rather than switching to VHS format mid-lecture

· Convert Video to DVD to prevent further deterioration of useful teaching material

· Improve interaction with students

· Update teaching materials on course website e.g. use up to date growth charts

· Avoid “contamination” in small group sessions too close together in a small room

· Improve session structure with less jumping backwards and forwards between topics

· Identify what adult medicine teaches (e.g. Diabetic Ketoacidosis) and ensure consistency

The following letter extracts give a sense of how suggestions for improvement were handled:

"‘One of the disadvantages, of course, of using the white board is that one can end up talking to the white board with one’s back to the students’" "‘I thought a couple of slides which you used could be ditched and we discussed that in our post-observation de-brief. I think this will help deal with some of the time pressures that you were experiencing’"

The Peer Observation process was also useful to reinforce good teaching as the following letter extracts demonstrate:

"‘The presentation was very lively and interactive and well illustrated with case studies. I particularly liked your stick diagram to illustrate the differential diagnosis of Wilms’ tumor and neuroblastoma’"

What about the observees?: the reflective component of PoT

The device of using an email ‘sound-bite’ to document evidence of the reflective component of Peer Observation was vindicated by the 100% response rate from observees. Seven major themes emerged from the data. These were: usefulness and relevance; value of feedback, insight and reflection; non-threatening process; enhanced teaching quality; professional development; and the necessity of peer observation for Faculty development.

Usefulness and relevance

PoT was overwhelmingly described by the Teaching Faculty as extremely useful, valuable and relevant to their teaching practice.

"‘I actually thought that the whole process was extremely useful and relevant’"

Value of feedback

A major theme was that of the value of feedback. Teachers strongly valued receiving feedback from the observer and from students and thought that it improved their performance. An important component of this was receiving ‘immediate feedback’.

"‘One very rarely gets feedback – positive or negative on teaching so it was an interesting and worthwhile experience’" "‘Live feedback can only improve one’s teaching overall’" "‘Useful to have feedback from the perspective of both the students and another teacher’"

Promotion of insight and reflection

Another major theme was that PoT gave teachers insight and promoted reflection on their teaching practice.

"‘Peer review is an essential way of gaining a perspective on one’s teaching’" "‘It made me look critically at the presentation…think more clearly about my objectives’" "‘All too often teaching takes place without the opportunity for this kind of reflection’."

Non-threatening process of PoT

The overwhelming majority of teachers thought that the process of PoT was constructive and non-threatening, although the potential for the process to be threatening was acknowledged. The peer aspect of the process was also appreciated.

"‘Helpful and non-threatening feedback on teaching skills’" "‘The way in which the observation was conducted was considerate and unobtrusive’" "‘Less threatening than a more ‘senior’ member of the teaching faculty sitting in on a session’" "‘When done in a sympathetic, but informed way, this is a helpful tool’"

Enhanced teaching quality

Teachers described the tangible improvement in their teaching practice that had resulted from the detailed and specific feedback they had received from PoT. The overwhelming perception of the teachers was that these changes had resulted in enhanced quality of learning for the students.

"‘I was able to make some useful changes to the lecture that has already led to improvements in the session’" "‘Forced me into improving my audio-visual aids…which I had been meaning to do’" "‘Resulted in a more effective teaching experience for the students’"

Professional development and worth

Teachers thought that PoT enhanced their professional development and feelings of worth. ‘I was fairly confident that students liked my presentations and that it was a fairly interactive session, but hearing from them and you formally just boosted that belief and confidence’

A necessary and important process

Finally, PoT was described by teachers as a necessary and important process in a Teaching Program. The teachers advocated that PoT should be more widely implemented.

"‘If we do not do this we are at risk of doing the same old thing without variation. I am sure that there are some academics who give the same talk today as 20 years ago – is this the way ahead? I think not. If you are not open to learning then you should not teach’" "‘I would recommend peer review to all teachers…should be used more widely’"

Benefit for the observers

The process of training to be an observer and implementing peer observation was also of benefit to the observers’ professional development. It promoted awareness and reflection on one’s own teaching style and content and it was useful to learn from and borrow teaching techniques from other teachers.

This study has shown that PoT can be used as a technique both to update and refine the content and delivery of a well-established teaching course, and to provide useful feedback to teaching Faculty. This technique is useful therefore, to Course Directors who rarely get on opportunity to see the fine detail of the content of course materials or to witness the interaction of teaching faculty and students in the front line. As a result of frequent repetition (our 8 week course is presented 6 times each year) it is easy for lectures to become stale and mechanical. Power Point-based lectures may be inherited from previous teachers and/or repeated from course to course and from year to year without being updated as new information arises. An example of this last point was the use of the 1990 Growth Charts for children rather than the World Health Organization growth charts in widespread use since 2009 in a teaching module on Normal Growth and Development. Introduction of an impartial but informed observer into the teaching session has been shown to be a relatively straightforward way of keeping the course material up to date and refreshing and reaffirming the teaching style of the lecturers. An important part of the process is ‘building a partnership’ or ‘working alliance’ between the observer and observee [ 14 ], and giving specific feedback that is focused on the task and in line with personal goals [ 15 ]. In agreement with a study on the implementation of PoT in pharmaceutical education we found that a particular strength of the process was the pre-observation meeting which allowed for ‘customization of the process to meet the Faculty member’s specific needs’ [ 16 ].

Teaching Faculty unanimously described the PoT process as very useful and relevant to their teaching practice and teachers appreciated the opportunity to discuss their teaching and to have constructive feedback. The success of this process was in no small measure related to the efforts expended on emphasizing that it was not an evaluative assessment but being applied by an equal as a professional developmental tool. There is little doubt that when used in such a positive way peer observation encourages and supports teaching Faculty. However, as a GP questionnaire revealed, anxiety is likely to be provoked if PoT is imposed from outside and is not conducted by a peer [ 4 ]. Moreover, as noted in another study, PoT also gave the observing teachers the opportunity to reflect on their own teaching practice and to borrow effective teaching techniques [ 7 ].

This study has also shown how important it is to individual lecturers to receive immediate feedback from students. At the end of each course students are required to complete the Oxford Course Evaluation Questionnaire which is used to assess the students’ perceptions about teaching, workload, goals, standards and assessment methods [ 17 ]. It is based on this ongoing evaluation that we know that the course is successful in achieving its stated aims and objectives and that the great majority of students are satisfied with the organization and delivery of the course. Nevertheless, only occasionally do individual teachers get singled out for special mention so the immediate feedback provided by the simple questionnaire designed for this study enabled lecturers to see how their own lecture was received by the students. Not all comments from students were positive. Examples included ‘spoke too quickly’, ‘too many slides’, ‘rushed at the end’, but when used in conjunction with the feedback from the observation these comments had a confirmatory effect and were taken constructively by the lecturers.

The advantages of PoT when adopted in this developmental way are clear. Teachers described tangible improvements in the quality of their teaching and an enhancement of their professional development and worth. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize the limitations of PoT. The successful application of PoT requires expertise, time and commitment. The fact that it took 30 months to complete 20 observations (at 2 hours each) indicates that the time factor is a significant limitation. This is in agreement with another study which has emphasized concern regarding ‘the time it will add to an already heavy workload’ [ 16 ]. In future it is intended that PoT will be offered to all new lecturers and re-offered to existing lecturers either on request or every five years. It is also hoped that other Faculty members may be willing to acquire the skills necessary to undertake PoT and so share the workload.

This study had a number of limitations. The department of Pediatrics is relatively small and only three peer observers have been trained to date although there are plans for more Faculty members to be trained in this process. There was also a challenge with other time pressures to complete the post-observation meeting and letter in a timely fashion. However, we believe that giving immediate feedback is one of the most important aspects of the process and consequently prioritized the post-observation feedback. Another potential limitation of the study was the lack of anonymity with the e-mail ‘sound-bite’ received from the teachers. We do not think that this is likely to have influenced our results as feedback revealed that teachers felt very comfortable with the peer aspect of PoT and did not view the process as threatening.

In summary, our study showed that PoT can be effectively implemented within an undergraduate pediatric curriculum for the development of the teaching staff and ultimately to improve the quality of student teaching.

Practice points

Peer Observation of Teaching can be used to:

· identify the need to update teaching course materials

· demonstrate to students departmental commitment to good teaching practice

· reaffirm good teaching skills of teaching faculty

· provide developmental feedback to help faculty refine teaching methods

· maintain high standards in undergraduate teaching

Shortland S: Observing teaching in HE: A case study of classroom observation within peer observation. Int J Educ Manag. 2004, 4 (2): 3-15.

Google Scholar

Hammersley-Fletcher L, Orsmond P: Evaluating our peers: is peer observation a meaningful process?. Stud High Educ. 2004, 29 (4): 489-503. 10.1080/0307507042000236380.

Article Google Scholar

Cosh J: Peer observation in Higher Education - A reflective approach. Innovat Educ Teach Int. 1998, 35 (2): 171-176.

Adshead L, White PT, Stephenson A: Introducing peer observation of teaching to GP teachers: a questionnaire study. Med Teach. 2006, 28 (2): e68-e73. 10.1080/01421590600617533.

Ramsden P: Learning to teach in higher education. 2003, Routledge Falmer, Oxon, 2

Fullerton H: Observation of teaching: Guidelines for observers. 1993, SEDA Publications, Birmingham

Finn K, Chiappa V, Puig A, Hunt DP: How to become a better clinical teacher: a collaborative peer observation process. Med Teach. 2011, 33 (2): 151-155. 10.3109/0142159X.2010.541534.

Bell M: Peer observation of teaching in Australia. 2002, LTSN Generic Centre, York

Siddiqui ZS, Jonas-Dwyer D, Carr SE: Twelve tips for peer observation of teaching. Med Teach. 2007 May, 29 (4): 297-300. 10.1080/01421590701291451.

Pendleton D, Scofield T, Tate P, Havelock P: The consultatation: an approach to learning and teaching. 1984, Oxford University Press, Oxford

King J: Giving Feedback. BMJ. 1999, 318 (7200): 2-10.1136/bmj.318.7200.2.

Lingard L, Albert M, Levinson W: Grounded theory, mixed methods, and action research. BMJ. 2008, 337: a567-10.1136/bmj.39602.690162.47.

Atkinson S, Abu-el Haj M: Domain analysis for qualitative public health data. Health Policy Plan. 1996, 11 (4): 438-442. 10.1093/heapol/11.4.438.

MacKinnon MM: Using observational feedback to promote academic development. Int J Acad Dev. 2008, 6 (1): 21-28.

Archer JC: State of the science in health professional education: effective feedback. Med Educ. 2010, 44: 101-108. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03546.x.

Trujillo JM, DiVall MV, Barr J, Gonyeau M, Van Amburgh JA, Matthews J, et al: Development of a Peer Teaching-Assessment Program and a Peer Observation and Evaluation Trial. Am J Pharm Educ. 2008, 72 (6): 1-9.

Trigwell K, Ashwin P: Undergraduate students' experience of learning at the University of Oxford, Oxford Learning Context Project: Final Report. 2003

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6920/12/26/prepub

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Paediatrics, Children’s Hospital, University of Oxford, Oxford, OX3 9DU, UK

Peter B Sullivan, Alexandra Buckle, Gregg Nicky & Sarah H Atkinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter B Sullivan .

Additional information

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PS is Director of Teaching, Learning and Assessment and Head of the University of Oxford, Department of Paediatrics. He is a qualified Physician Educator of the Royal College of Physicians of London and a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. He conceived and carried out the study and wrote the paper. AB is tutor at the University of Oxford and holds the University’s Postgraduate Diploma in Learning and Teaching in Higher Education and is a Fellow of the Higher Education Academy. She has a special interest in Peer Observation and advised on the design of the study and contributed to writing the manuscript. NG is Course Administrator for the undergraduate paediatric course in the University of Oxford, Department of Paediatrics and was responsible for the logistic and administrative arrangements of the study. SA is a Clinical Lecturer in the Department of Paediatrics, University of Oxford with a special interest in Medical Student Education. She contributed to carrying out the study, analysis of data and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Additional file 1: appendix 1.: feedback form. (doc 31 kb), authors’ original submitted files for images.

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Authors’ original file for figure 1

Rights and permissions.

This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Sullivan, P.B., Buckle, A., Nicky, G. et al. Peer observation of teaching as a faculty development tool. BMC Med Educ 12 , 26 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-26

Download citation

Received : 19 September 2011

Accepted : 04 May 2012

Published : 04 May 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-12-26

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Peer observation

- Medical education

BMC Medical Education

ISSN: 1472-6920

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

Observational Studies: Cohort and Case-Control Studies

Jae w. song.

1 Research Fellow, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery The University of Michigan Health System; Ann Arbor, MI

Kevin C. Chung

2 Professor of Surgery, Section of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery The University of Michigan Health System; Ann Arbor, MI

Observational studies are an important category of study designs. To address some investigative questions in plastic surgery, randomized controlled trials are not always indicated or ethical to conduct. Instead, observational studies may be the next best method to address these types of questions. Well-designed observational studies have been shown to provide results similar to randomized controlled trials, challenging the belief that observational studies are second-rate. Cohort studies and case-control studies are two primary types of observational studies that aid in evaluating associations between diseases and exposures. In this review article, we describe these study designs, methodological issues, and provide examples from the plastic surgery literature.

Because of the innovative nature of the specialty, plastic surgeons are frequently confronted with a spectrum of clinical questions by patients who inquire about “best practices.” It is thus essential that plastic surgeons know how to critically appraise the literature to understand and practice evidence-based medicine (EBM) and also contribute to the effort by carrying out high-quality investigations. 1 Well-designed randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have held the pre-eminent position in the hierarchy of EBM as level I evidence ( Table 1 ). However, RCT methodology, which was first developed for drug trials, can be difficult to conduct for surgical investigations. 3 Instead, well-designed observational studies, recognized as level II or III evidence, can play an important role in deriving evidence for plastic surgery. Results from observational studies are often criticized for being vulnerable to influences by unpredictable confounding factors. However, recent work has challenged this notion, showing comparable results between observational studies and RCTs. 4 , 5 Observational studies can also complement RCTs in hypothesis generation, establishing questions for future RCTs, and defining clinical conditions.

Levels of Evidence Based Medicine

From REF 1 .

Observational studies fall under the category of analytic study designs and are further sub-classified as observational or experimental study designs ( Figure 1 ). The goal of analytic studies is to identify and evaluate causes or risk factors of diseases or health-related events. The differentiating characteristic between observational and experimental study designs is that in the latter, the presence or absence of undergoing an intervention defines the groups. By contrast, in an observational study, the investigator does not intervene and rather simply “observes” and assesses the strength of the relationship between an exposure and disease variable. 6 Three types of observational studies include cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies ( Figure 1 ). Case-control and cohort studies offer specific advantages by measuring disease occurrence and its association with an exposure by offering a temporal dimension (i.e. prospective or retrospective study design). Cross-sectional studies, also known as prevalence studies, examine the data on disease and exposure at one particular time point ( Figure 2 ). 6 Because the temporal relationship between disease occurrence and exposure cannot be established, cross-sectional studies cannot assess the cause and effect relationship. In this review, we will primarily discuss cohort and case-control study designs and related methodologic issues.

Analytic Study Designs. Adapted with permission from Joseph Eisenberg, Ph.D.

Temporal Design of Observational Studies: Cross-sectional studies are known as prevalence studies and do not have an inherent temporal dimension. These studies evaluate subjects at one point in time, the present time. By contrast, cohort studies can be either retrospective (latin derived prefix, “retro” meaning “back, behind”) or prospective (greek derived prefix, “pro” meaning “before, in front of”). Retrospective studies “look back” in time contrasting with prospective studies, which “look ahead” to examine causal associations. Case-control study designs are also retrospective and assess the history of the subject for the presence or absence of an exposure.

COHORT STUDY

The term “cohort” is derived from the Latin word cohors . Roman legions were composed of ten cohorts. During battle each cohort, or military unit, consisting of a specific number of warriors and commanding centurions, were traceable. The word “cohort” has been adopted into epidemiology to define a set of people followed over a period of time. W.H. Frost, an epidemiologist from the early 1900s, was the first to use the word “cohort” in his 1935 publication assessing age-specific mortality rates and tuberculosis. 7 The modern epidemiological definition of the word now means a “group of people with defined characteristics who are followed up to determine incidence of, or mortality from, some specific disease, all causes of death, or some other outcome.” 7

Study Design

A well-designed cohort study can provide powerful results. In a cohort study, an outcome or disease-free study population is first identified by the exposure or event of interest and followed in time until the disease or outcome of interest occurs ( Figure 3A ). Because exposure is identified before the outcome, cohort studies have a temporal framework to assess causality and thus have the potential to provide the strongest scientific evidence. 8 Advantages and disadvantages of a cohort study are listed in Table 2 . 2 , 9 Cohort studies are particularly advantageous for examining rare exposures because subjects are selected by their exposure status. Additionally, the investigator can examine multiple outcomes simultaneously. Disadvantages include the need for a large sample size and the potentially long follow-up duration of the study design resulting in a costly endeavor.

Cohort and Case-Control Study Designs

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Cohort Study

Cohort studies can be prospective or retrospective ( Figure 2 ). Prospective studies are carried out from the present time into the future. Because prospective studies are designed with specific data collection methods, it has the advantage of being tailored to collect specific exposure data and may be more complete. The disadvantage of a prospective cohort study may be the long follow-up period while waiting for events or diseases to occur. Thus, this study design is inefficient for investigating diseases with long latency periods and is vulnerable to a high loss to follow-up rate. Although prospective cohort studies are invaluable as exemplified by the landmark Framingham Heart Study, started in 1948 and still ongoing, 10 in the plastic surgery literature this study design is generally seen to be inefficient and impractical. Instead, retrospective cohort studies are better indicated given the timeliness and inexpensive nature of the study design.

Retrospective cohort studies, also known as historical cohort studies, are carried out at the present time and look to the past to examine medical events or outcomes. In other words, a cohort of subjects selected based on exposure status is chosen at the present time, and outcome data (i.e. disease status, event status), which was measured in the past, are reconstructed for analysis. The primary disadvantage of this study design is the limited control the investigator has over data collection. The existing data may be incomplete, inaccurate, or inconsistently measured between subjects. 2 However, because of the immediate availability of the data, this study design is comparatively less costly and shorter than prospective cohort studies. For example, Spear and colleagues examined the effect of obesity and complication rates after undergoing the pedicled TRAM flap reconstruction by retrospectively reviewing 224 pedicled TRAM flaps in 200 patients over a 10-year period. 11 In this example, subjects who underwent the pedicled TRAM flap reconstruction were selected and categorized into cohorts by their exposure status: normal/underweight, overweight, or obese. The outcomes of interest were various flap and donor site complications. The findings revealed that obese patients had a significantly higher incidence of donor site complications, multiple flap complications, and partial flap necrosis than normal or overweight patients. An advantage of the retrospective study design analysis is the immediate access to the data. A disadvantage is the limited control over the data collection because data was gathered retrospectively over 10-years; for example, a limitation reported by the authors is that mastectomy flap necrosis was not uniformly recorded for all subjects. 11

An important distinction lies between cohort studies and case-series. The distinguishing feature between these two types of studies is the presence of a control, or unexposed, group. Contrasting with epidemiological cohort studies, case-series are descriptive studies following one small group of subjects. In essence, they are extensions of case reports. Usually the cases are obtained from the authors' experiences, generally involve a small number of patients, and more importantly, lack a control group. 12 There is often confusion in designating studies as “cohort studies” when only one group of subjects is examined. Yet, unless a second comparative group serving as a control is present, these studies are defined as case-series. The next step in strengthening an observation from a case-series is selecting appropriate control groups to conduct a cohort or case-control study, the latter which is discussed in the following section about case-control studies. 9

Methodological Issues

Selection of subjects in cohort studies.

The hallmark of a cohort study is defining the selected group of subjects by exposure status at the start of the investigation. A critical characteristic of subject selection is to have both the exposed and unexposed groups be selected from the same source population ( Figure 4 ). 9 Subjects who are not at risk for developing the outcome should be excluded from the study. The source population is determined by practical considerations, such as sampling. Subjects may be effectively sampled from the hospital, be members of a community, or from a doctor's individual practice. A subset of these subjects will be eligible for the study.

Levels of Subject Selection. Adapted from Ref 9 .

Attrition Bias (Loss to follow-up)

Because prospective cohort studies may require long follow-up periods, it is important to minimize loss to follow-up. Loss to follow-up is a situation in which the investigator loses contact with the subject, resulting in missing data. If too many subjects are loss to follow-up, the internal validity of the study is reduced. A general rule of thumb requires that the loss to follow-up rate not exceed 20% of the sample. 6 Any systematic differences related to the outcome or exposure of risk factors between those who drop out and those who stay in the study must be examined, if possible, by comparing individuals who remain in the study and those who were loss to follow-up or dropped out. It is therefore important to select subjects who can be followed for the entire duration of the cohort study. Methods to minimize loss to follow-up are listed in Table 3 .

Methods to Minimize Loss to Follow-Up

Adapted from REF 2 .

CASE-CONTROL STUDIES

Case-control studies were historically borne out of interest in disease etiology. The conceptual basis of the case-control study is similar to taking a history and physical; the diseased patient is questioned and examined, and elements from this history taking are knitted together to reveal characteristics or factors that predisposed the patient to the disease. In fact, the practice of interviewing patients about behaviors and conditions preceding illness dates back to the Hippocratic writings of the 4 th century B.C. 7

Reasons of practicality and feasibility inherent in the study design typically dictate whether a cohort study or case-control study is appropriate. This study design was first recognized in Janet Lane-Claypon's study of breast cancer in 1926, revealing the finding that low fertility rate raises the risk of breast cancer. 13 , 14 In the ensuing decades, case-control study methodology crystallized with the landmark publication linking smoking and lung cancer in the 1950s. 15 Since that time, retrospective case-control studies have become more prominent in the biomedical literature with more rigorous methodological advances in design, execution, and analysis.

Case-control studies identify subjects by outcome status at the outset of the investigation. Outcomes of interest may be whether the subject has undergone a specific type of surgery, experienced a complication, or is diagnosed with a disease ( Figure 3B ). Once outcome status is identified and subjects are categorized as cases, controls (subjects without the outcome but from the same source population) are selected. Data about exposure to a risk factor or several risk factors are then collected retrospectively, typically by interview, abstraction from records, or survey. Case-control studies are well suited to investigate rare outcomes or outcomes with a long latency period because subjects are selected from the outset by their outcome status. Thus in comparison to cohort studies, case-control studies are quick, relatively inexpensive to implement, require comparatively fewer subjects, and allow for multiple exposures or risk factors to be assessed for one outcome ( Table 4 ). 2 , 9

Advantages and Disadvantages of the Case-Control Study

An example of a case-control investigation is by Zhang and colleagues who examined the association of environmental and genetic factors associated with rare congenital microtia, 16 which has an estimated prevalence of 0.83 to 17.4 in 10,000. 17 They selected 121 congenital microtia cases based on clinical phenotype, and 152 unaffected controls, matched by age and sex in the same hospital and same period. Controls were of Hans Chinese origin from Jiangsu, China, the same area from where the cases were selected. This allowed both the controls and cases to have the same genetic background, important to note given the investigated association between genetic factors and congenital microtia. To examine environmental factors, a questionnaire was administered to the mothers of both cases and controls. The authors concluded that adverse maternal health was among the main risk factors for congenital microtia, specifically maternal disease during pregnancy (OR 5.89, 95% CI 2.36-14.72), maternal toxicity exposure during pregnancy (OR 4.76, 95% CI 1.66-13.68), and resident area, such as living near industries associated with air pollution (OR 7.00, 95% CI 2.09-23.47). 16 A case-control study design is most efficient for this investigation, given the rarity of the disease outcome. Because congenital microtia is thought to have multifactorial causes, an additional advantage of the case-control study design in this example is the ability to examine multiple exposures and risk factors.

Selection of Cases

Sampling in a case-control study design begins with selecting the cases. In a case-control study, it is imperative that the investigator has explicitly defined inclusion and exclusion criteria prior to the selection of cases. For example, if the outcome is having a disease, specific diagnostic criteria, disease subtype, stage of disease, or degree of severity should be defined. Such criteria ensure that all the cases are homogenous. Second, cases may be selected from a variety of sources, including hospital patients, clinic patients, or community subjects. Many communities maintain registries of patients with certain diseases and can serve as a valuable source of cases. However, despite the methodologic convenience of this method, validity issues may arise. For example, if cases are selected from one hospital, identified risk factors may be unique to that single hospital. This methodological choice may weaken the generalizability of the study findings. Another example is choosing cases from the hospital versus the community; most likely cases from the hospital sample will represent a more severe form of the disease than those in the community. 2 Finally, it is also important to select cases that are representative of cases in the target population to strengthen the study's external validity ( Figure 4 ). Potential reasons why cases from the original target population eventually filter through and are available as cases (study participants) for a case-control study are illustrated in Figure 5 .

Levels of Case Selection. Adapted from Ref 2 .

Selection of Controls

Selecting the appropriate group of controls can be one of the most demanding aspects of a case-control study. An important principle is that the distribution of exposure should be the same among cases and controls; in other words, both cases and controls should stem from the same source population. The investigator may also consider the control group to be an at-risk population, with the potential to develop the outcome. Because the validity of the study depends upon the comparability of these two groups, cases and controls should otherwise meet the same inclusion criteria in the study.

A case-control study design that exemplifies this methodological feature is by Chung and colleagues, who examined maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy and the risk of newborns developing cleft lip/palate. 18 A salient feature of this study is the use of the 1996 U.S. Natality database, a population database, from which both cases and controls were selected. This database provides a large sample size to assess newborn development of cleft lip/palate (outcome), which has a reported incidence of 1 in 1000 live births, 19 and also enabled the investigators to choose controls (i.e., healthy newborns) that were generalizable to the general population to strengthen the study's external validity. A significant relationship with maternal cigarette smoking and cleft lip/palate in the newborn was reported in this study (adjusted OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.36-1.76). 18

Matching is a method used in an attempt to ensure comparability between cases and controls and reduces variability and systematic differences due to background variables that are not of interest to the investigator. 8 Each case is typically individually paired with a control subject with respect to the background variables. The exposure to the risk factor of interest is then compared between the cases and the controls. This matching strategy is called individual matching. Age, sex, and race are often used to match cases and controls because they are typically strong confounders of disease. 20 Confounders are variables associated with the risk factor and may potentially be a cause of the outcome. 8 Table 5 lists several advantages and disadvantages with a matching design.

Advantages and Disadvantages for Using a Matching Strategy

Multiple Controls

Investigations examining rare outcomes may have a limited number of cases to select from, whereas the source population from which controls can be selected is much larger. In such scenarios, the study may be able to provide more information if multiple controls per case are selected. This method increases the “statistical power” of the investigation by increasing the sample size. The precision of the findings may improve by having up to about three or four controls per case. 21 - 23

Bias in Case-Control Studies

Evaluating exposure status can be the Achilles heel of case-control studies. Because information about exposure is typically collected by self-report, interview, or from recorded information, it is susceptible to recall bias, interviewer bias, or will rely on the completeness or accuracy of recorded information, respectively. These biases decrease the internal validity of the investigation and should be carefully addressed and reduced in the study design. Recall bias occurs when a differential response between cases and controls occurs. The common scenario is when a subject with disease (case) will unconsciously recall and report an exposure with better clarity due to the disease experience. Interviewer bias occurs when the interviewer asks leading questions or has an inconsistent interview approach between cases and controls. A good study design will implement a standardized interview in a non-judgemental atmosphere with well-trained interviewers to reduce interviewer bias. 9

The STROBE Statement: The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement

In 2004, the first meeting of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) group took place in Bristol, UK. 24 The aim of the group was to establish guidelines on reporting observational research to improve the transparency of the methods, thereby facilitating the critical appraisal of a study's findings. A well-designed but poorly reported study is disadvantaged in contributing to the literature because the results and generalizability of the findings may be difficult to assess. Thus a 22-item checklist was generated to enhance the reporting of observational studies across disciplines. 25 , 26 This checklist is also located at the following website: www.strobe-statement.org . This statement is applicable to cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies. In fact, 18 of the checklist items are common to all three types of observational studies, and 4 items are specific to each of the 3 specific study designs. In an effort to provide specific guidance to go along with this checklist, an “explanation and elaboration” article was published for users to better appreciate each item on the checklist. 27 Plastic surgery investigators should peruse this checklist prior to designing their study and when they are writing up the report for publication. In fact, some journals now require authors to follow the STROBE Statement. A list of participating journals can be found on this website: http://www.strobe-statement.org./index.php?id=strobe-endorsement .

Due to the limitations in carrying out RCTs in surgical investigations, observational studies are becoming more popular to investigate the relationship between exposures, such as risk factors or surgical interventions, and outcomes, such as disease states or complications. Recognizing that well-designed observational studies can provide valid results is important among the plastic surgery community, so that investigators can both critically appraise and appropriately design observational studies to address important clinical research questions. The investigator planning an observational study can certainly use the STROBE statement as a tool to outline key features of a study as well as coming back to it again at the end to enhance transparency in methodology reporting.

Acknowledgments

Supported in part by a Midcareer Investigator Award in Patient-Oriented Research (K24 AR053120) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (to Dr. Kevin C. Chung).

None of the authors has a financial interest in any of the products, devices, or drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Peer observation

Peer observation is one element which teachers may choose to focus on during their professional practice days . Find out what it is and how to get started. Includes implementation tools and video case studies.

The use of the resources on this page is optional. They can be a useful reference point for future planning and improvement if appropriate to the needs of the school.

About peer observation

Peer observation is about teachers observing each others’ practice and learning from one another. It aims to support the sharing of best practice and build awareness about the impact of your own teaching.

Effective peer observation (including feedback and reflection):

- focuses on teachers' individual needs and gives an opportunity to learn from, and give feedback to peers

- is a core component of creating a professional community and building collective efficacy

- can help teachers continue to improve their practice in ways that better promote student learning

- is a developmental learning opportunity.

For principals and school leaders: Integrating peer observation within existing structures, such as your school strategic plan, will facilitate a greater line of sight between personal and collective improvement goals.

Get started

The following resources will help you to get started with - or further embed - peer observation at your school.

Tools and tips for teachers

Stages of peer observation - templates

Blank and annotated templates for teachers to help inform the stages of peer observation:

Giving feedback to colleagues

The following guidelines outline protocols for school staff to:

- give quality feedback to colleagues

- create an open and supportive culture during peer observations.

Case studies

Video case studies to support schools in embedding peer observation, feedback and reflection are available below.

Chelsea Heights Primary School

Peer observation at Chelsea Heights Primary School is linked to teachers' professional practice Performance and Development goals and the school's Annual Implementation Plan.

Learn more about how teachers work together to navigate peer observation and feedback at Chelsea Heights Primary School.

Roxburgh College

This school takes a holistic approach to peer observation, involving teachers, parents and students in learning walks.

Learn more about what drives the college’s passion for peer observation and how it is conducted.

You can also view short videos from the school/teacher , student and parent perspectives.

Verney Road School

This specialist school's approach to peer observation was developed by its teachers and education support staff. Teachers and education support staff use their mobile phones to film short videos, which are then used for peer observation and feedback conversations.

See Verney Road School's approach to peer observation.

For more information, see the peer observation process at Verney Road School.

Watch how a teacher and an educational support staff member undertake peer observation together at Verney Road School.

Our website uses a free tool to translate into other languages. This tool is a guide and may not be accurate. For more, see: Information in your language

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

Bronchiectasis-associated infections and outcomes in a large, geographically diverse electronic health record cohort in the United States

- Samantha G Dean 1 ,

- Rebekah A Blakney 1 ,

- Emily E Ricotta 1 ,

- James D Chalmers 2 ,

- Sameer S Kadri 3 ,

- Kenneth N Olivier 4 , 5 &

- D Rebecca Prevots 1

BMC Pulmonary Medicine volume 24 , Article number: 172 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Bronchiectasis is a pulmonary disease characterized by irreversible dilation of the bronchi and recurring respiratory infections. Few studies have described the microbiology and prevalence of infections in large patient populations outside of specialized tertiary care centers.

We used the Cerner HealthFacts Electronic Health Record database to characterize the nature, burden, and frequency of pulmonary infections among persons with bronchiectasis. Chronic infections were defined based on organism-specific guidelines.

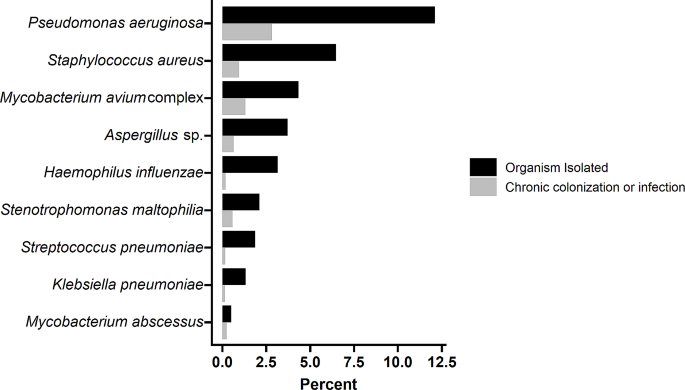

We identified 7,749 patients who met our incident bronchiectasis case definition. In this study population, the organisms with the highest rates of isolate prevalence were Pseudomonas aeruginosa with 937 (12%) individuals, Staphylococcus aureus with 502 (6%), Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) with 336 (4%), and Aspergillus sp. with 288 (4%). Among persons with at least one isolate of each respective pathogen, 219 (23%) met criteria for chronic P. aeruginosa colonization, 74 (15%) met criteria for S. aureus chronic colonization, 101 (30%) met criteria for MAC chronic infection, and 50 (17%) met criteria for Aspergillus sp. chronic infection. Of 5,795 persons with at least two years of observation, 1,860 (32%) had a bronchiectasis exacerbation and 3,462 (60%) were hospitalized within two years of bronchiectasis diagnoses. Among patients with chronic respiratory infections, the two-year occurrence of exacerbations was 53% and for hospitalizations was 82%.

Conclusions

Patients with bronchiectasis experiencing chronic respiratory infections have high rates of hospitalization.

Peer Review reports

Bronchiectasis is a pulmonary disease defined by the irreversible dilation of the bronchi [ 1 , 2 ]. Patients typically have a chronic, productive cough and recurring respiratory infections [ 1 ], with an associated increased risk of mortality [ 3 ]. The current estimated prevalence of bronchiectasis in the United States is up to 213 cases per 100,000 [ 4 ] across all age groups, and 700 per 100,000 among adults aged > 65 years [ 5 ]. Bronchiectasis has multiple causes including infectious, inflammatory, autoimmune, allergic, and congenital disorders [ 6 , 7 ]. Recurrent respiratory infections are common and result from impaired mucociliary clearance [ 8 ]. These infections trigger inflammation, which in turn worsens underlying damage. Consequently, this vicious cycle leads to increased frequency of exacerbations [ 1 , 8 , 9 ].

Although certain organisms such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus have been associated with exacerbations of bronchiectasis [ 10 ], systematic evaluations of bronchiectasis-associated infections in large community and non-tertiary referral populations are lacking. Understanding the etiology and impact of bronchiectasis has implications for effectively treating patients and managing disease [ 11 ]. Ongoing cohort studies are expanding our knowledge about the landscape of infections among bronchiectasis patients. In the United States (US), data collected through the US Bronchiectasis Research Registry (BRR) describe infections and treatment among bronchiectasis patients [ 12 ]. The European Multicentre Bronchiectasis Audit and Research Collaboration (EMBARC) registry in Europe has recruited more than 20,000 patients as of September 2020 and will provide further insight regarding infections in bronchiectasis patients [ 13 , 14 ]. However, the US BRR and the EMBARC registry are both based primarily in specialist bronchiectasis clinics and therefore may be biased towards more severe manifestations of the disease. In this study we use a large, nationally distributed Electronic Health Record (EHR) dataset, including microbiological data, to describe bronchiectasis-associated infections and selected outcomes.

Study population

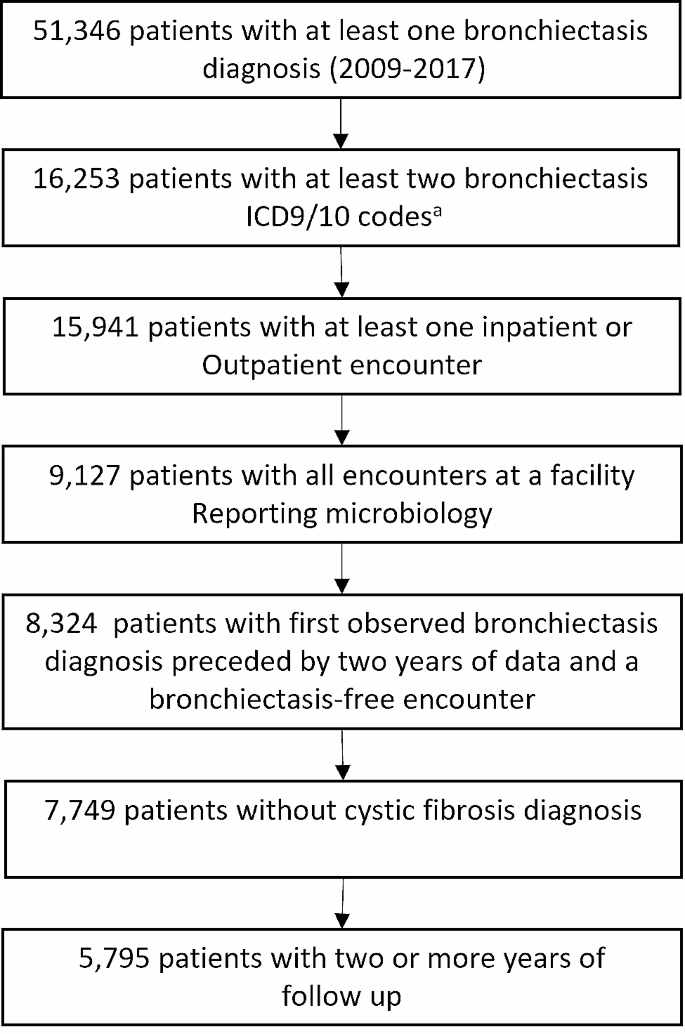

Our study population comprised patients in the Cerner HealthFact s Electronic Health Record (EHR) database with at least two International Classification of Diseases 9th or 10th revision (ICD9/10) codes for bronchiectasis from 2009 to 2017 (Fig. 1 ), with no ICD9/10 codes for cystic fibrosis, and where all encounters were in inpatient or outpatient healthcare facilities reporting microbiology data. Facility characteristics are described in Table 1 . We considered bronchiectasis cases to be incident if no prior encounters included a bronchiectasis ICD9/10 code for the two years preceding the first bronchiectasis ICD9/10 code (Fig. 1 ). We included microbiology isolates from only respiratory sites and subset to the most common species isolated, after removing non-pathogenic species and non-speciated results (Table 2 ). We used text searches for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), asthma, and lung cancer to identify ICD codes for these conditions. We defined time under observation as the duration of time between the incident bronchiectasis encounter and the end of the study period.

Study population flowchart. a ICD9/10 codes: 494.0, 494.1, 494, 011.50, 011.54, 748.6, 011.51, 011.53, 011.52, 011.55, 011.5, 011.56, J47, J47.9, J47.1, J47.0, Q33.4

Data analysis

To estimate the prevalence of organisms associated with bronchiectasis [ 12 ], we summed the number of persons in our population with at least one isolate of the selected organisms on or after the date of their first bronchiectasis diagnosis. Whether frequent detection of an organism is considered “infection” or “colonization” varies by organism, thus we also assessed the prevalence using organism-specific definitions of chronic infection or chronic colonization from the literature and expert opinion. For Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) and M. abscessus , we defined chronic infection as two or more isolates on separate days within two years of one another [ 15 ]. For Aspergillus sp [ 16 ]. and Stenotrophomas maltophilia [ 17 ] we defined chronic infection as two or more isolates on separate days within one year of one another. For Pseudomonas aeruginosa , we used the definition of chronic colonization established by international consensus and also used in the bronchiectasis severity index (BSI), which counts the number of individuals who had at least two isolates of P. aeruginosa three or more months apart within a year [ 18 , 19 ]. For the remaining species where a more specific definition was not available, we continued to use the EMBARC/BRR chronic colonization definition (Table 2 ). For calculations of the prevalence of at least one isolate of the specified organism the population denominator was the 7,749 persons who met our case definition for incident bronchiectasis. For purposes of clarity, for the remainder of this paper we will refer to the organism-specific definitions of chronic colonization and chronic infection as “chronic infection.” For calculations of chronic infection prevalence, the population denominator was all persons with at least one isolate of the specified organism.

To describe the impact of chronic infections on clinical outcomes, we evaluated hospitalizations and exacerbations among patients with chronic infection for the most common organisms. For all analyses of chronic infection, we included the 5,795 patients (75% of study population) with at least two years of follow up time after their initial bronchiectasis diagnosis. Hospitalizations were defined as any inpatient encounter. Exacerbations were defined as one or more ICD9/10 codes for bronchiectasis with acute exacerbation or acute respiratory infection, COPD with acute exacerbation, or asthma with acute exacerbation. Codes for asthma and COPD were included to increase the sensitivity of capturing exacerbations. We included a thirty day “window” prior to the incident bronchiectasis diagnosis encounter to include hospitalizations and exacerbations that may have contributed to the identification of bronchiectasis. Rates of hospitalization and exacerbations were calculated for the duration of the study period following the incident bronchiectasis encounter. In addition, because MAC and P. aeruginosa are of particular concern among persons with bronchiectasis, we calculated the total time hospitalized using the cumulative time across inpatient encounters. Analysis was completed using R version 3.6.1. We assessed the significance of the difference in proportions of exacerbations and hospitalizations among chronic infection subgroups using two-proportion z-tests with a one-sided alternative and significance assessed at p < 0.05. Relative risks of exacerbations and hospitalizations comparing chronic infection vs. no infection were estimated using a univariate negative binomial regression.

We identified 7,749 persons with incident bronchiectasis, which comprised our study population (Fig. 1 ). Of these, 5,050 (65%) were women and 5,030 (65%) were aged ≥ 65 years. Concurrent pulmonary disease was common: 3,848 (50%) were diagnosed with COPD, 2,741 (35%) with asthma, and 537 (7%) with lung cancer (Table 3 ). Overall, persons sought care at 260 unique healthcare facilities, and 65% had all encounters at a single facility within the EHR system during the study period. An additional 24% received care at two facilities.

Prevalence of infecting pathogens