Likes, Shares, and Beyond: Exploring the Impact of Social Media in Essays

Table of contents

- 1 Definition and Explanation of a Social Media Essay

- 2.1 Topics for an Essay on Social Media and Mental Health

- 2.2 Social Dynamics

- 2.3 Social Media Essay Topics about Business

- 2.4 Politics

- 3 Research and Analysis

- 4 Structure Social Media Essay

- 5 Tips for Writing Essays on Social Media

- 6 Examples of Social Media Essays

- 7 Navigating the Social Media Labyrinth: Key Insights

In the world of digital discourse, our article stands as a beacon for those embarking on the intellectual journey of writing about social media. It is a comprehensive guide for anyone venturing into the dynamic world of social media essays. Offering various topics about social media and practical advice on selecting engaging subjects, the piece delves into research methodologies, emphasizing the importance of credible sources and trend analysis. Furthermore, it provides invaluable tips on structuring essays, including crafting compelling thesis statements and hooks balancing factual information with personal insights. Concluding with examples of exemplary essays, this article is an essential tool for students and researchers alike, aiding in navigating the intricate landscape of its impact on society.

Definition and Explanation of a Social Media Essay

Essentially, when one asks “What is a social media essay?” they are referring to an essay that analyzes, critiques, or discusses its various dimensions and effects. These essays can range from the psychological implications of its use to its influence on politics, business strategies, and social dynamics.

A social media essay is an academic or informational piece that explores various aspects of social networking platforms and their impact on individuals and society.

In crafting such an essay, writers blend personal experiences, analytical perspectives, and empirical data to paint a full picture of social media’s role. For instance, a social media essay example could examine how these platforms mold public opinion, revolutionize digital marketing strategies, or raise questions about data privacy ethics. Through a mix of thorough research, critical analysis, and personal reflections, these essays provide a layered understanding of one of today’s most pivotal digital phenomena.

Great Social Media Essay Topics

When it comes to selecting a topic for your essay, consider its current relevance, societal impact, and personal interest. Whether exploring the effects on business, politics, mental health, or social dynamics, these social media essay titles offer a range of fascinating social media topic ideas. Each title encourages an exploration of the intricate relationship between social media and our daily lives. A well-chosen topic should enable you to investigate the impact of social media, debate ethical dilemmas, and offer unique insights. Striking the right balance in scope, these topics should align with the objectives of your essays, ensuring an informative and captivating read.

Topics for an Essay on Social Media and Mental Health

- The Impact of Social Media on Self-Esteem.

- Unpacking Social Media Addiction: Causes, Effects, and Solutions.

- Analyzing Social Media’s Role as a Catalyst for Teen Depression and Anxiety.

- Social Media and Mental Health Awareness: A Force for Good?

- The Psychological Impacts of Cyberbullying in the Social Media Age.

- The Effects of Social Media on Sleep and Mental Health.

- Strategies for Positive Mental Health in the Era of Social Media.

- Real-Life vs. Social Media Interactions: An Essay on Mental Health Aspects.

- The Mental Well-Being Benefits of a Social Media Detox.

- Social Comparison Psychology in the Realm of Social Media.

Social Dynamics

- Social Media and its Impact on Interpersonal Communication Skills: A Cause and Effect Essay on Social Media.

- Cultural Integration through Social Media: A New Frontier.

- Interpersonal Communication in the Social Media Era: Evolving Skills and Challenges.

- Community Building and Social Activism: The Role of Social Media.

- Youth Culture and Behavior: The Influence of Social Media.

- Privacy and Personal Boundaries: Navigating Social Media Challenges.

- Language Evolution in Social Media: A Dynamic Shift.

- Leveraging Social Media for Social Change and Awareness.

- Family Dynamics in the Social Media Landscape.

- Friendship in the Age of Social Media: An Evolving Concept.

Social Media Essay Topics about Business

- Influencer Marketing on Social Media: Impact and Ethics.

- Brand Building and Customer Engagement: The Power of Social Media.

- The Ethics and Impact of Influencer Marketing in Social Media.

- Measuring Business Success Through Social Media Analytics.

- The Changing Face of Advertising in the Social Media World.

- Revolutionizing Customer Service in the Social Media Era.

- Market Research and Consumer Insights: The Social Media Advantage.

- Small Businesses and Startups: The Impact of Social Media.

- Ethical Dimensions of Social Media Advertising.

- Consumer Behavior and Social Media: An Intricate Relationship.

- The Role of Social Media in Government Transparency and Accountability

- Social Media’s Impact on Political Discourse and Public Opinion.

- Combating Fake News on Social Media: Implications for Democracy.

- Political Mobilization and Activism: The Power of Social Media.

- Social Media: A New Arena for Political Debates and Discussions.

- Government Transparency and Accountability in the Social Media Age.

- Voter Behavior and Election Outcomes: The Social Media Effect.

- Political Polarization: A Social Media Perspective.

- Tackling Political Misinformation on Social Media Platforms.

- The Ethics of Political Advertising in the Social Media Landscape.

- Memes as a Marketing Tool: Successes, Failures, and Pros of Social Media.

- Shaping Public Opinion with Memes: A Social Media Phenomenon.

- Political Satire and Social Commentary through Memes.

- The Psychology Behind Memes: Understanding Their Viral Nature.

- The Influence of Memes on Language and Communication.

- Tracing the History and Evolution of Internet Memes.

- Memes in Online Communities: Culture and Subculture Formation.

- Navigating Copyright and Legal Issues in the World of Memes.

- Memes as a Marketing Strategy: Analyzing Successes and Failures.

- Memes and Global Cultural Exchange: A Social Media Perspective.

Research and Analysis

In today’s fast-paced information era, the ability to sift through vast amounts of data and pinpoint reliable information is more crucial than ever. Research and analysis in the digital age hinge on identifying credible sources and understanding the dynamic landscape. Initiating your research with reputable websites is key. Academic journals, government publications, and established news outlets are gold standards for reliable information. Online databases and libraries provide a wealth of peer-reviewed articles and books. For websites, prioritize those with domains like .edu, .gov, or .org, but always critically assess the content for bias and accuracy. Turning to social media, it’s a trove of real-time data and trends but requires a discerning approach. Focus on verified accounts and official pages of recognized entities.

Analyzing current trends and user behavior is crucial for staying relevant. Platforms like Google Trends, Twitter Analytics, and Facebook Insights offer insights into what’s resonating with audiences. These tools help identify trending topics, hashtags, and the type of content that engages users. Remember, it reflects and influences public opinion and behavior. Observing user interactions, comments, and shares can provide a deeper understanding of consumer attitudes and preferences. This analysis is invaluable for tailoring content, developing marketing strategies, and staying ahead in a rapidly evolving digital landscape.

Structure Social Media Essay

In constructing a well-rounded structure for a social media essay, it’s crucial to begin with a strong thesis statement. This sets the foundation for essays about social media and guides the narrative.

Thesis Statements

A thesis statement is the backbone of your essay, outlining the main argument or position you will explore throughout the text. It guides the narrative, providing a clear direction for your essay and helping readers understand the focus of your analysis or argumentation. Here are some thesis statements:

- “Social media has reshaped communication, fostering a connected world through instant information sharing, yet it has come at the cost of privacy and genuine social interaction.”

- “While social media platforms act as potent instruments for societal and political transformation, they present significant challenges to mental health and the authenticity of information.”

- “The role of social media in contemporary business transcends mere marketing; it impacts customer relationships, shapes brand perception, and influences operational strategies.”

Social Media Essay Hooks

Social media essay hooks are pivotal in grabbing the reader’s attention right from the beginning and compelling them to continue reading. A well-crafted hook acts as the engaging entry point to your essay, setting the tone and framing the context for the discussion that will follow.

Here are some effective social media essay hooks:

- “In a world where a day without social media is unimaginable, its pervasive presence is both a testament to its utility and a source of various societal issues.”

- “Each scroll, like, and share on social media platforms carries the weight of influencing public opinion and shaping global conversations.”

- “Social media has become so ingrained in our daily lives that its absence would render the modern world unrecognizable.”

Introduction:

Navigating the digital landscape, an introduction for a social media essay serves as a map, charting the terrain of these platforms’ broad influence across various life aspects. This section should briefly summarize the scope of the essay, outlining both the benefits and the drawbacks, and segue into the thesis statement.

When we move to the body part of the essay, it offers an opportunity for an in-depth exploration and discussion. It can be structured first to examine the positive aspects of social media, including improved communication channels, innovative marketing strategies, and the facilitation of social movements. Following this, the essay should address the negative implications, such as issues surrounding privacy, the impact on mental health, and the proliferation of misinformation. Incorporating real-world examples, statistical evidence, and expert opinions throughout the essay will provide substantial support for the arguments presented.

Conclusion:

It is the summit of the essay’s exploration, offering a moment to look back on the terrain covered. The conclusion should restate the thesis in light of the discussions presented in the body. It should summarize the key points made, reflecting on the multifaceted influence of social media in contemporary society. The essay should end with a thought-provoking statement or question about the future role of social media, tying back to the initial hooks and ensuring a comprehensive and engaging end to the discourse.

Tips for Writing Essays on Social Media

In the ever-evolving realm of digital dialogue, mastering the art of essay writing on social media is akin to navigating a complex web of virtual interactions and influences. Writing an essay on social media requires a blend of analytical insight, factual accuracy, and a nuanced understanding of the digital landscape. Here are some tips to craft a compelling essay:

- Incorporate Statistical Data and Case Studies

Integrate statistical data and relevant case studies to lend credibility to your arguments. For instance, usage statistics, growth trends, and demographic information can provide a solid foundation for your points. Case studies, especially those highlighting its impact on businesses, politics, or societal change, offer concrete examples that illustrate your arguments. Ensure your sources are current and reputable to maintain the essay’s integrity.

- Balance Personal Insights with Factual Information

While personal insights can add a unique perspective to your essay, balancing them with factual information is crucial. Personal observations and experiences can make your essay relatable and engaging, but grounding these insights in factual data ensures credibility and helps avoid bias.

- Respect Privacy

When discussing real-world examples or case studies, especially those involving individuals or specific organizations, be mindful of privacy concerns. Avoid sharing sensitive information, and always respect the confidentiality of your sources.

- Maintain an Objective Tone

It is a polarizing topic, but maintaining an objective tone in your essay is essential. Avoid emotional language and ensure that your arguments are supported by evidence. An objective approach allows readers to form opinions based on the information presented.

- Use Jargon Wisely

While using social media-specific terminology can make your essay relevant and informed, it’s important to use jargon judiciously. Avoid overuse and ensure that terms are clearly defined for readers who might not be familiar with their lingo.

Examples of Social Media Essays

Title: The Dichotomy of Social Media: A Tool for Connection and a Platform for Division

Introduction

In the digital era, social media has emerged as a paradoxical entity. It serves as a bridge connecting distant corners of the world and a battleground for conflicting ideologies. This essay explores this dichotomy, utilizing statistical data, case studies, and real-world examples to understand its multifaceted impact on society.

Section 1 – Connection Through Social Media:

Social media’s primary allure lies in its ability to connect. A report by the Pew Research Center shows that 72% of American adults use some form of social media, where interactions transcend geographical and cultural barriers. This statistic highlights the platform’s popularity and role in fostering global connections. An exemplary case study of this is the #MeToo movement. Originating as a hashtag on Twitter, it grew into a global campaign against sexual harassment, demonstrating its power to mobilize and unify people for a cause.

However, personal insights suggest that while it bridges distances, it can also create a sense of isolation. Users often report feeling disconnected from their immediate surroundings, hinting at the platform’s double-edged nature. Despite enabling connections on a global scale, social media can paradoxically alienate individuals from their local context.

Section 2 – The Platform for Division

Conversely, social media can amplify societal divisions. Its algorithm-driven content can create echo chambers, reinforcing users’ preexisting beliefs. A study by the Knight Foundation found that it tends to polarize users, especially in political contexts, leading to increased division. This is further exacerbated by the spread of misinformation, as seen in the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election case, where it was used to disseminate false information, influencing public opinion and deepening societal divides.

Respecting privacy and maintaining an objective tone, it is crucial to acknowledge that social media is not divisive. Its influence is determined by both its usage and content. Thus, it is the obligation of both platforms to govern content and consumers to access information.

In conclusion, it is a complex tool. It has the unparalleled ability to connect individuals worldwide while possessing the power to divide. Balancing the personal insights with factual information presented, it’s clear that its influence is a reflection of how society chooses to wield it. As digital citizens, it is imperative to use it judiciously, understanding its potential to unite and divide.

Delving into the intricacies of social media’s impact necessitates not just a keen eye for detail but an analytical mindset to dissect its multifaceted layers. Analysis is paramount because it allows us to navigate through the vast sea of information, distinguishing between mere opinion and well-supported argumentation.

This essay utilizes tips for writing a social media essay. Statistical data from the Pew Research Center and the Knight Foundation lend credibility to the arguments. The use of the #MeToo movement as a case study illustrates its positive impact, while the reference to the 2016 U.S. Presidential Election demonstrates its negative aspects. The essay balances personal insights with factual information, respects privacy, maintains an objective tone, and appropriately uses jargon. The structure is clear and logical, with distinct sections for each aspect of its impact, making it an informative and well-rounded analysis of its role in modern society.

Navigating the Social Media Labyrinth: Key Insights

In the digital age, the impact of social media on various aspects of human life has become a critical area of study. This article has provided a comprehensive guide for crafting insightful and impactful essays on this subject, blending personal experiences with analytical rigor. Through a detailed examination of topics ranging from mental health and social dynamics to business and politics, it has underscored the dual nature of social media as both a unifying and divisive force. The inclusion of statistical data and case studies has enriched the discussion, offering a grounded perspective on the nuanced effects of these platforms.

The tips and structures outlined serve as a valuable framework for writers to navigate the complex interplay between social media and societal shifts. As we conclude, it’s clear that understanding social media’s role requires a delicate balance of critical analysis and open-mindedness. Reflecting on its influence, this article guides the creation of thoughtful essays and encourages readers to ponder the future of digital interactions and their implications for the fabric of society.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

How Does Media Influence Culture and Society?

Introduction.

The impact of social media on culture cannot be overestimated. It had a great influence on the cultural changes in society, so that the role of men and women has been defined by the mass media. In the process, it affected both intercultural and international communication. Many people globally have been trying to understand the meaning of culture and its influence on how human beings behave (Purvis 46).

So, how does media influence culture and society? This essay tries to answer the question in detail, examining the terms separately and discussing the connection. Besides, the author touches upon another crucial question: how does culture affect global media?

Definitions of Culture

Different sociology scholars have tried to come up with various definitions of culture, with many of them having a lot of contradictions. The media has been instrumental in explaining to the public its meaning and enabling everyone to have a cultural identity. The well-being of people can only be guaranteed if they have a strong and definite identity that influences their sense of self and their relationship with other people who have a different cultural identity.

The difference in beliefs and backgrounds helps people from different societies to relate and negotiate well. Intercultural relations have continued to fail because many people are not aware of their cultural identity. The internet and mass media have been instrumental in promoting globalization which has led to many positive influences on the culture of different societies and races across the world.

Many societies have been able to add new aspects to their cultures as a result of globalization, which is greatly facilitated by the internet and the mass media (Purvis 67). Globalization enables us to have an overview of different cultures across the world and, in the end, be in a position to copy some positive aspects. These papers will highlight the importance of media in culture construction and how the media has led to intercultural socialization.

How Does Media Affect Culture?

Learning about other cultures through the media can create some stereotypes, which can be negative at times. The media plays an important role in educating people and making them familiar with some cultures so as to avoid stereotypes. Examples of stereotypes that have been created by the media include portraying Muslims as terrorists and Africans as illiterates.

By educating people about different cultures and emphasizing the positive aspects, the media can play an important role in constructing the cultures of different societies across the world and, in the process, avoiding prejudice and stereotyping. The mass media has got a large audience that gives a lot of power to influence many societal issues. The media advocates for social concerns and enables communication and exchange of positive cultural values among different societies (Purvis 91).

The mass media presents information about a particular region of culture to the whole world, and it s therefore very important for the information to be properly investigated before the presentation. Global sports such as the World Cup enjoy a lot of following across the world, and the media has the power to influence many cultural aspects during such tournaments.

Many ideas concerning males and masculinity have been constructed by the media. The media portrays a man as brave and without emotions and women as fearful and emotional in television programs and movies. The media forms the idea of a real man in society as one who is aggressive and financially stable. Women are portrayed as housekeepers, and the children grow up with this information.

The media has constructed a new image of beauty which has continued to influence many women and even young girls across the world. Since beauty has been associated with having a slim figure, many women and young girls have become very enthusiastic about weight control and have also been influenced to change their diet. Schools and parents have failed to educate children about sexuality and, in the process leaving the media as the only source of information about sexuality (Siapera 34).

According to traditional cultures, it is often taboo to talk about sexuality with children, but this is bound to change because schools and parents realize that it is no longer sensible to avoid talking to children about sex-related issues. The media plays a very important role in ensuring that societal norms, ideologies, and customs are disseminated. Socialization has been made possible and much simpler because of the media.

Through socialization, different societies are able to share languages, traditions, customs, roles, and values. The media has become a significant social force in recent years, especially for young people. Whereas the older generations view the media as a source of entertainment and information, the majority of young people see it as a perfect platform for socialization.

The media highlights different values and norms and the possible consequences of failing to adhere to societal norms and values. Through the media, society is able to learn how to behave in different circumstances according to one’s role and status (Siapera 34). The media helps in portraying models of behavior that are supposed to be followed by society and its members.

How Does Media Influence Culture & Society?

The media is a fundamental agent of socialization whose operations are very basic compared to other agents such as schools, families, and religious groups. The internet has got different forms of socialization, such as Facebook and Twitter, that have completely revolutionalized the way people socialize in recent times.

Apart from the internet, other media agents that have become very fundamental in socialization include the radio, newspapers, magazines, and tabloids, just to mention a few. Through these media agents, ideas and opinions can be shared and exchanged.

The internet has emerged to be very the most powerful audio-visual medium since it can now be accessed by many people across the world. Through the internet, one is able to influence others or be influenced by other people who use the internet to share and exchange their opinions. Television is another media agent that has really enhanced socialization in many ways (Siapera 71).

Television gives people a good platform to give their opinions on various topics and issues affecting human life. The opinions shared on television reach a large number of people because television is a mass media that is capable of reaching a large audience. The media is often rapid and interactive and is a perfect socialization agent for young people who watch the television most of the time compared to elderly people.

Since the youth form the majority of the audience, many media houses are always smart enough to present topics and programs that appeal to young people. Media houses have the power to manipulate their audience in a skillful manner for the audience to buy into their ideas and messages. The media is able to make some products look appealing to the general public, an example being the status one would acquire if they possessed the latest cell phone in the market (Siapera 85).

The mass media has become a very vital agent in the development of children and the behavior of adults. Although the mass media has some negative influences on the audience, its benefits tend to override the negatives. There are some programs on television that have useful information, like the teachings of some foreign languages that are essential for social interaction.

Programs that teach languages are very beneficial to both children and adults in international socialization. Other programs enable children to be creative and dynamic in their thinking. These programs enable both children and adults to be more knowledgeable and affect their way of doing things. It is, therefore, very important for parents and guardians to be wary of the type of programs their children watch because some programs can end up having a negative influence on them.

Programs with vulgar language and violence should be avoided by children because they can influence them negatively. Different networks have really affected the sense of reality in our society. Internet networks have continued to depict some issues that are out of touch with reality (Siapera 85). The issue of stereotypes that have been mentioned in this paper has greatly been cultivated by networks.

People who get information about certain types of people and cultures without real experience can end up having a wrong impression about a particular race, culture, or region that is contrary to the reality of the situation on the ground. Networks have affected our culture by highlighting some cultures as being primitive and, in the process, prompting people to have a cultural shift.

In conclusion, it is important to note that the media has a very important role in shaping our culture. The media has promoted globalization, and in the end, people from different nationalities and cultures are able to exchange values and ideas that are beneficial to their lives.

The mass media and the internet have greatly contributed to the cultural construction of many societies across the world and therefore making them become very important agents of socialization. Mass media agents such as the television, internet, films, and radio have been very instrumental in promoting socialization by providing a perfect platform for exchanging ideas and opinions on various issues that affect life. Networks have also been able to affect different cultures across the world.

Some of the issues highlighted in films and movies are always fiction, but society tends to practice them in reality, which has led to some serious consequences. Networks and organizations have made the world to become a global village. Networks and organizations will no doubt continue to influence the culture of many societies since there is so much information being passed across different networks and organizations. The media will continue to influence people’s way of life both in the present and in the future.

Works Cited

Purvis, Tony. Get Set for Media and Cultural Studies . New York: Edinburgh University Press, 2006. Print.

Siapera, Eugenia. Cultural Diversity and Global Media: The Mediation of Difference. New York: Jon Wiley and Sons, 2010. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 17). How Does Media Influence Culture and Society? https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-our-culture-is-affected-by-the-media/

"How Does Media Influence Culture and Society?" IvyPanda , 17 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/how-our-culture-is-affected-by-the-media/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'How Does Media Influence Culture and Society'. 17 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "How Does Media Influence Culture and Society?" October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-our-culture-is-affected-by-the-media/.

1. IvyPanda . "How Does Media Influence Culture and Society?" October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-our-culture-is-affected-by-the-media/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "How Does Media Influence Culture and Society?" October 17, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/how-our-culture-is-affected-by-the-media/.

- Age and the Agents of Socialization

- Socialization for the Transmission of Culture

- Socialization as a Lifelong Process

- The Impact of Media Bias

- Values Portrayed in Popular Media

- Envisioning the media ten years from now

- Mass Media Impact on Society

- The Effects of Media Violence on People

MINI REVIEW article

Cross-cultural communication on social media: review from the perspective of cultural psychology and neuroscience.

- 1 School of International Economics and Management, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing, China

- 2 School of Economics, Beijing Technology and Business University, Beijing, China

- 3 Institute of the Americas, University College London, London, United Kingdom

Introduction: In recent years, with the popularity of many social media platforms worldwide, the role of “virtual social network platforms” in the field of cross-cultural communication has become increasingly important. Scholars in psychology and neuroscience, and cross-disciplines, are attracted to research on the motivation, mechanisms, and effects of communication on social media across cultures.

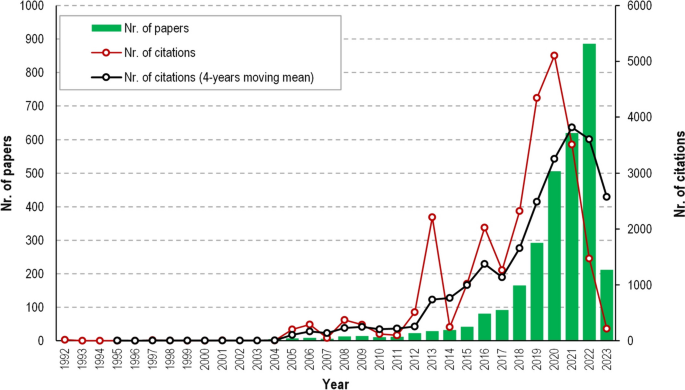

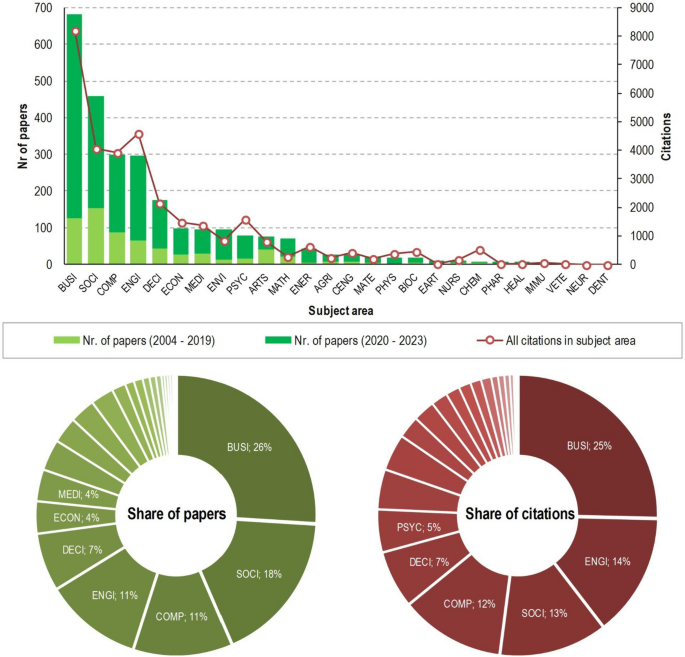

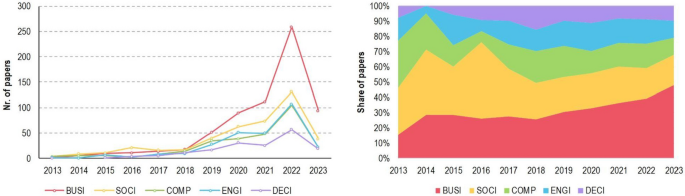

Methods and Analysis: This paper collects the co-citation of keywords in “cultural psychology,” “cross-culture communication,” “neuroscience,” and “social media” from the database of web of science and analyzes the hotspots of the literature in word cloud.

Results: Based on our inclusion criteria, 85 relevant studies were extracted from a database of 842 papers. There were 44 articles on cultural communication on social media, of which 26 were from the perspective of psychology and five from the perspective of neuroscience. There are 27 articles that focus on the integration of psychology and neuroscience, but only a few are related to cross-cultural communication on social media.

Conclusion: Scholars have mainly studied the reasons and implications of cultural communication on social media from the perspectives of cultural psychology and neuroscience separately. Keywords “culture” and “social media” generate more links in the hot map, and a large number of keywords of cultural psychology and neuroscience also gather in the hot map, which reflects the trend of integration in academic research. While cultural characteristics have changed with the development of new media and virtual communities, more research is needed to integrate the disciplines of culture, psychology, and neuroscience.

Introduction

Cross-cultural communication refers to communication and interaction among different cultures, involving information dissemination and interpersonal communication as well as the flow, sharing, infiltration, and transfer of various cultural elements in the world ( Carey, 2009 ; Del Giudice et al., 2016 ). With more than half of the world’s population using social media, such as Facebook, Twitter, and WeChat, communication across culture has become smoother and more frequently ( Boamah, 2018 ; Chin et al., 2021 ). Subsequently, cultural exchanges, collisions, conflicts, and integration among various nationalities, races, and countries on these platforms have become obvious, and related research articles by scholars in different disciplines have increased ( Papa et al., 2020 ). In traditional cross-cultural research, experts often divide different cultures based on their boundaries, such as countries, races, languages, and so on. However, with the development of digitalization, new cultural relationships have been formed both within and outside geopolitical boundaries, and new understanding and theories are needed to explain the motivation, process, and implications of cross-cultural communications in the digital era ( Chin et al., 2020 ). Research in this field is an emerging area, and scholars are studying from different perspectives ( Xu et al., 2016 ; Santoro et al., 2021 ). Cultural psychology and neuroscience are two main base theories, and they show a trend of integration, such as cultural neuroscience and cultural neuropsychology. In this case, it is important to highlight the important achievements of this field and identify potential research gaps to provide potential directions for further research. This review aims to provide an overview of cross-cultural communication research from the perspective of cultural psychology and neuroscience and identify the integrating trend and potential directions.

Method and Source

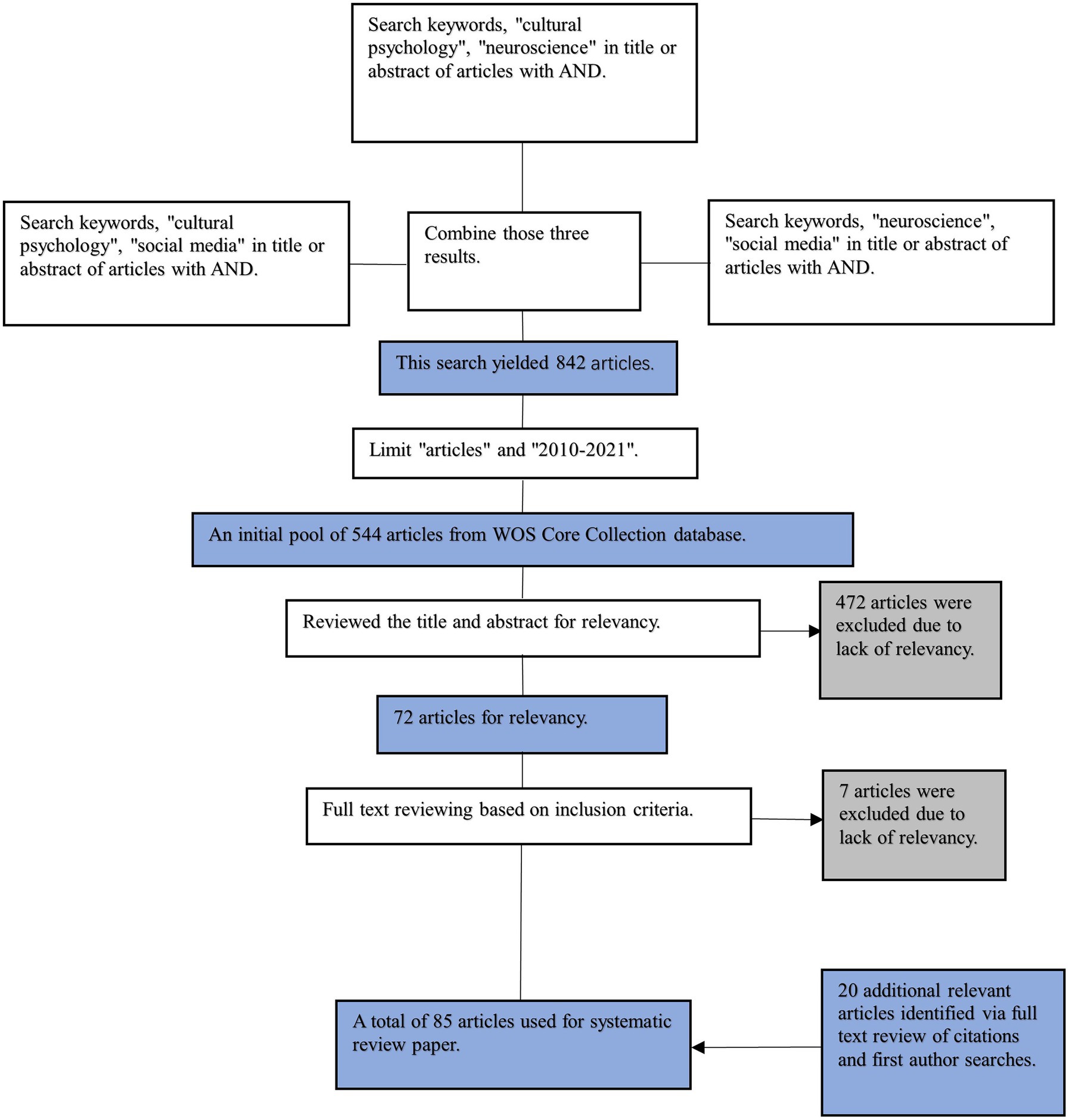

We used the Web of Science (WoS) database to select relevant articles published between January 2010 and December 2021. The following inclusion criteria were used:

1. The document types should be articles rather than proceedings papers or book reviews. And the articles should be included in the Web of Science Core Collection.

2. When searching for articles, the topic should include at least two keywords: “cultural psychology,” “neuroscience,” “social media.”

3. Articles must be published after 2010 to ensure the content of the literature is forward.

4. This study should investigate the integration of cultural psychology and neuroscience or explore cultural issues in social media from the perspective of cultural psychology or neuroscience. The content could be cultural conflict and integration on social platforms, explanations of cultural conflict and integration on social platforms, or integration of neuroscience and cultural psychology.

Based on the above inclusion criteria, 85 relevant studies were searched, analyzed, and evaluated. These documents were identified according to the procedure illustrated in Figure 1 . The following combinations of keywords were used: (cultural psychology AND social media), (neuroscience AND social media), (cultural psychology AND neuroscience), [social media AND (cross-cultural communication OR cultural conflict OR cultural integration)], and (neuroscience, cultural psychology, and cross-cultural). The number of studies was further reduced by limiting the document type and time range. Consequently, we obtained an initial pool of 544 articles. To ensure the relevance of the literature in the initial pool, we reviewed the titles and abstracts of these articles. Articles targeting pure neuroscience and information technology were excluded and 72 articles were retained. We selected 65 articles after reviewing the full text. For most papers excluded from the initial pool, cultural issues on social media were not the main topic but digital media or culture itself. The most typical example of irrelevant articles was that culture or cultural psychology was only briefly mentioned in the abstracts. Moreover, 20 additional relevant articles were identified via full-text review of citations and first author searches. Using the above steps, 85 articles were selected for the literature review.

Figure 1 . Schematic representation of literature search and selection procedure.

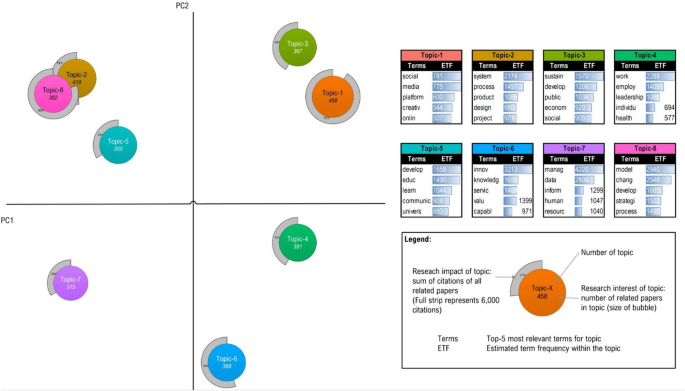

Overview of Selected Articles

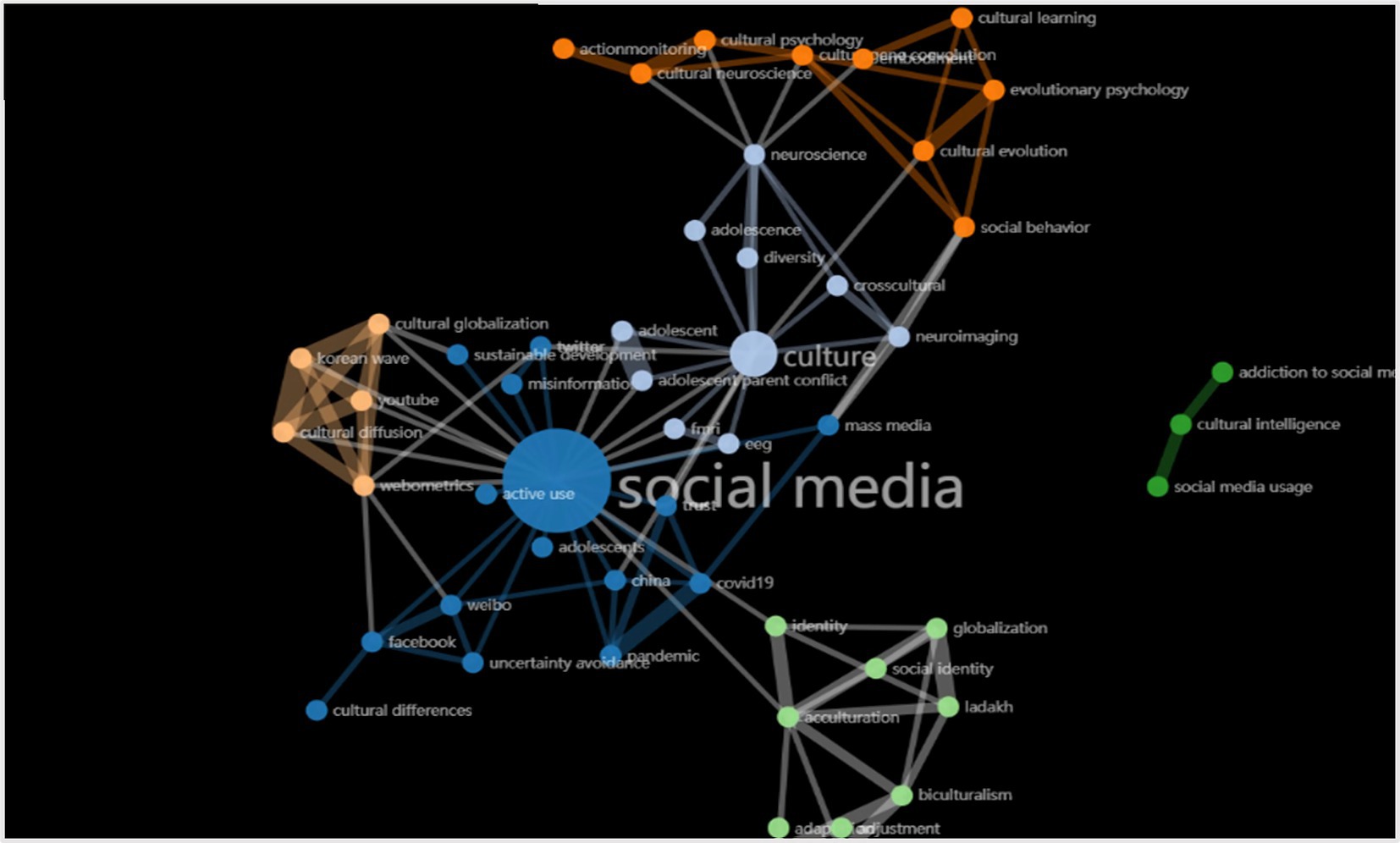

Here, frequency refers to the percentage of occurrences of an item in the total number of studies. The keywords “acculturation,” “cultural evolution” occurred frequently together with “social media,” “culture,” and “neuroscience.” This is as expected because psychologists and economists have long known that human decision-making is influenced by the behavior of others and that public information could improve acculturation and lead to cultural evolution. The popularity of social media clearly gives public information an opportunity to spread widely, which has caused an increase in research on the cross-cultural communication of social media. In the last decade, the link between cultural issues and social media research has grown. This is reflected in the knowledge graph ( Figure 2 ). Keywords “culture” and “social media” generate lots of links with “social media” and “mass media,” which is shown in blue node groups and white node groups. “Social media” and “cultural globalization,” “biculturalism,” “acculturation” also form node convergences. The integration of neuroscience and cultural psychology is also represented in Figure 2 as an orange node group. These integration trends can also be verified in the time dimension. As time passes, keyword frequencies have changed from a single component of “social media” or “culture” to a multi-component of “social media,” “culture,” “acculturation,” “neuroscience,” “cultural evolution.” The frequency of all keywords is presented through the overall word cloud.

Figure 2 . Keywords knowledge graph.

We identified three different research topics from the 85 selected articles: cross-cultural communication on social platforms, explanation of cultural conflict and integration on social platforms, and the integration of neuroscience and cultural psychology. Existing literature has analyzed and studied the interaction between cross-cultural users, enterprises, and countries on social media. For instance, some scholars have found that social media play a significant role in negotiating and managing the identity of transient migrants relating to the home and host culture during the acculturation process ( Cleveland, 2016 ; Yau et al., 2019 ). Social media usage by expatriates also promotes cultural identity and creativity ( Hu et al., 2020 ). In addition to the discussion of existing phenomena, many articles have discussed the causes of social media cultural transmission. A new research field, cultural neuroscience, indicates the integration of neuroscience and cultural psychology. These issues are reviewed in the following sections.

There were 44 articles on cultural communication on social media, which accounted for 51.76% of the 85 selected papers. Among these, there were 26 studies on cultural communication on social media from the perspective of psychology, five articles from the perspective of neurology, four articles about enterprises using social media for cross-cultural operations, and nine articles about how governments use social media for cross-cultural communication. Although there are 27 articles that discuss the trend of integration of psychology and neuroscience, few use integrated methods to analyze the behavior of cross-cultural communication.

From Perspective of Cultural Psychology

Cultural psychology researchers have focused on why information is shared. Some scholars have divided the reasons into individual and network levels ( Wang et al., 2021 ). Studies have explored information sharing within a specific domain, such as health information and news dissemination ( Hodgson, 2018 ; Li et al., 2018 ; Wang and Chin, 2020 ). Cultural psychology provides a rich explanation for the factors that influence cultural communication. Cultural background affects the process of cultural communication, such as self-construal, which the host country may alter it ( Huang and Park, 2013 ; Thomas et al., 2019 ). This may influence communication behaviors, such as people’s intention to use social media applications, attitudes toward social capital, social media commerce, and sharing behavior itself ( Chu and Choi, 2010 ; Han and Kim, 2018 ; Li et al., 2018 ).

Factors other than culture cannot be ignored: public broadcast firms and fans promote communication, controversial comments may draw more attention, the sociality of the social media capsule expands the scope of information communication, and how news is portrayed has changed ( Meza and Park, 2014 ; Jin and Yoon, 2016 ; Hodgson, 2018 ). Demographic factors, such as sex and age, are not ineffective ( Xu et al., 2015 ). The experiential aspects have also been noted ( Wang et al., 2021 ). Scholars have also noted the importance of cultural intelligence ( Hu et al., 2017 ).

The topic that researchers are most interested in is the relationship between society and individuals. Many studies have focused on the influence of collectivist and individualist cultures, such as social media users’ activity differences, attentional tendencies, and self-concept ( Chu and Choi, 2010 ; Thomas et al., 2019 ). There are some other interesting topics, such as the relationship among multicultural experiences, cultural intelligence, and creativity, the evaluation of the validity of the two measures, the changing status of crucial elements in the social system, and the government effect in risk communication ( Hu et al., 2017 ; Ji and Bates, 2020 ). Extending to the practical level, mobile device application usability and social media commerce were evaluated ( Hoehle et al., 2015 ; Han and Kim, 2018 ).

At the methodological level, researchers have bridged the gap between reality and online behaviors, and the feasibility of social media dataset analysis has been proven ( Huang and Park, 2013 ; Thomas et al., 2019 ). Some new concepts have been examined and some models have been developed ( Hoehle et al., 2015 ; Li et al., 2018 ). The most common method is to quantify questionnaire information ( Chu and Choi, 2010 ; Hu et al., 2017 ; Han and Kim, 2018 ; Li et al., 2018 ; Wang et al., 2021 ). The online survey accounted for a large proportion of respondents. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) is used to evaluate other measures ( Ji and Bates, 2020 ). Researchers are particularly interested in the metric approach ( Meza and Park, 2014 ). Some combine other methods, such as profile and social network analyses ( Xu et al., 2015 ). Scholars have used qualitative research to obtain detailed feedback from respondents ( Jin and Yoon, 2016 ; Hodgson, 2018 ). Content analysis was also used ( Yang and Xu, 2018 ).

From Perspective of Neuroscience

Neuroscientific explanations focus on understanding the mechanisms of cultural conflict and integration. Neuroscience researchers are concerned about the effects of the brain on cultural communication and the possible consequences of cultural communication on human behavior and rely on the study of the brain as a tool. Neuroscience can be used to study how people behave in reality. Given the similarity between offline and online behaviors, neuroscience can study online behaviors and link them to cultural communication ( Meshi et al., 2015 ). Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, both inside and outside the laboratory, have become the subject of neuroscience studies. One example of long-term studies outside the laboratory is the study of natural Facebook behavior that was recorded for weeks ( Montag et al., 2017 ).

Motivation research is a well-documented topic. The reason for using social media, motivation to share information, and neural factors related to sharing behavior have been discussed ( Fischer et al., 2018 ). Many scholars have connected motivation with social life based on the inseparable relationship between online behaviors and social life. Some academics hope to provide predictions of real life, such as forecasting marketing results, while some warned of the risks, in which tremendous attention has been paid to the situation of adolescents ( Motoki et al., 2020 ). They are susceptible to acceptance and rejection ( Crone and Konijn, 2018 ). Behavioral addiction and peer influence in the context of risky behaviors also lead to public concern ( Meshi et al., 2015 ; Sherman et al., 2018 ).

On a practical level, neuroscience studies have made predictions possible through the findings of activity in brain regions linked to mentalizing ( Motoki et al., 2020 ). Judgments of social behavior are also warranted, and peer endorsement is a consideration ( Sherman et al., 2018 ). Thus, the dangers of cultural communication can be alleviated.

At the methodological level, the feasibility of linking directly recorded variables to neuroscientific data has been proven, which provides a methodological basis for further studies linking neuroscience and cultural communication ( Montag et al., 2017 ). Neuroscience researchers have shown a preference for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) methods, which include functional and structural MRI scans ( Montag et al., 2017 ; Sherman et al., 2018 ). Although some scholars have pointed out the shortcomings of MRI research and attempted to use the electroencephalographic (EEG) method, most scholars still use MRI and combine it with other methods, such as neuroimaging ( Motoki et al., 2020 ). Despite the similarities in the methods used, there were differences in the scanned areas. Some researchers scan multiple regions, such as the ventral striatum ( VS ) and ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC), while others focus on analyzing the content of a single region, such as the nucleus accumbens (NAcc; Baek et al., 2017 ). Related characteristics have been discussed, such as theta amplitudes that affect information sharing ( Fischer et al., 2018 ). Some inquire whether the different properties of brain regions can lead to different results ( Montag et al., 2017 ).

Integration of Neuroscience and Cultural Psychology

Of the 85 papers we selected, 27 discussed the integrated development of psychology and neuroscience, and the number of articles in this discipline increased. Cultural psychology has made remarkable progress in identifying various cultural traits that can influence human psychology and behavior on social media. Cultural neuroscience as a cross-subject of the rise in recent years, through the integration of psychology, anthropology, genetics, neuroscience, and other disciplines, explains the interaction of culture and the human brain, and how they jointly affect the neural mechanism of cognitive function. At an early stage, scholars presented the interactive dynamic evolutionary relationship between the brain and culture from multiple perspectives ( Moffittet et al., 2006 ). However, with technological improvements in brain imaging, it is possible to solve and explore interactions between the human brain, psychology, and cultural networks using an empirical approach.

Cultural characteristics have dramatically changed during the last half-century with the development of new media and new virtual ways of communication ( Kotik-Friedgut and Ardila, 2019 ). Existing research has shown that the neural resources of the brain are always adapted to the ever-increasing complexity and scale of social interaction to ensure that individuals are not marginalized by society ( Dunbar and Shultz, 2007 ). The interaction between biological evolution and cultural inheritance is a process full of unknowns and variables. Therefore, research on the relationships between culture, psychology, and neuroscience will progress together.

At the methodological level, communication on social media by users from different backgrounds provides a new research environment and massive data for cross-disciplinary research. Big data on social media and AI technology can analyze not only the reactions, emotions, and expressions of an individual but also the relevant information of an ethnic group or a cultural group. A number of neurological and psychological studies are beginning to leverage AI and social media data, and the two disciplines are intertwined with each other ( Pang, 2020 ; Wang et al., 2021 ). This quantitative analysis also helps enterprises and government departments to understand and affect cultural conflicts and integration ( Bond and Goldstein, 2015 ).

Different Schools of Thoughts

Social media provides platforms for communication and facilitates communication across cultures; however, the specific content exchanged is considered from the perspective of cultural proximity. Although some scholars think that social media can significantly promote mutual acceptance and understanding across cultures, others have realized that digital platforms actually strengthen the recognition and identity of their respective cultures ( Hopkins, 2009 ). To study the motivations, results, and implications of cross-cultural communication in virtual communities and conduct an empirical analysis, psychologists and neuroscientists provide their grounds and explanations.

Current Research Gaps

Although there are many articles discussing the trend of integration of psychology and neuroscience, few of them use integrated methods to analyze the behavior and implications of cross-cultural communication, mainly on cultural evolution and social effects. There are both practical and theoretical needs to be addressed to promote deep integration. For example, both private and public departments urgently need to learn scientific strategies to avoid cultural conflicts and promote integration. Further, a systematic and legal theory is also needed for scholars to conduct research in the sensitive field, which may be related to privacy protection and related issues.

Potential Future Development

For the research object, the classification of culture in emerging research is general, while with the development of big data methods on social media, cross-cultural communication among more detailed groups will be a potential direction. For the research framework, although cultural neuroscience is already a multidisciplinary topic, the ternary interaction among the brain, psychology, and culture in a virtual community will be very important. For the research method, brain imaging technology-related data and social media data may cause issues, such as privacy protection, personal security, informed consent, and individual autonomy. These legal and ethical issues require special attention in the development process of future research.

Cross-cultural communication research in the digital era not only needs to respond to urgent practical needs to provide scientific strategies to solve cultural differences and cultural conflicts, but also to promote the emergence of more vigorous theoretical frameworks and methods. Existing articles have mainly studied the reasons and implications of cultural communication on social media from the perspectives of cultural psychology and neuroscience separately. The CiteSpace-based hot topic map also shows the clustering trend of keywords related to cultural psychology and neuroscience, reflecting the intersection of the two fields. At the same time, there are many links between the two keyword nodes of “culture” and “social media,” which indicates that there is no lack of studies on cultural communication on social media from the perspective of cultural psychology. While cultural characteristics have changed with the development of new media and big data and related technologies have improved significantly, more research is needed to integrate the disciplines of culture, psychology, and neuroscience both in theory and methods.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This paper was funded by the Beijing Social Science Fund, China (Project No. 21JCC060).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baek, E. C., Scholz, C., O’Donnell, M. B., and Falk, E. B. (2017). The value of sharing information: a neural account of information transmission. Psychol. Sci. 28, 851–861. doi: 10.1177/0956797617695073

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Boamah, E. (2018). Information culture of Ghanaian immigrants living in New Zealand. Libr. Rev. 67, 585–606. doi: 10.1108/GKMC-07-2018-0065

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bond, P., and Goldstein, I. (2015). Government intervention and information aggregation by prices. J. Finance 70, 2777–2812. doi: 10.1111/jofi.12303

Carey, J. W. (2009). Communication as Culture: Essays on Media and Society. Routledge.

Google Scholar

Chin, T., Meng, J., Wang, S., Shi, Y., and Zhang, J. (2021). Cross-cultural metacognition as a prior for humanitarian knowledge: when cultures collide in global health emergencies, J. Knowl. Manag. doi: 10.1108/JKM-10-2020-0787 [Epub ahead-of-print]

Chin, T., Wang, S., and Rowley, C. (2020). Polychronic knowledge creation in cross-border business models: a sea-like heuristic metaphor. J. Knowl. Manag. doi: 10.1108/JKM-04-2020-0244 [Epub ahead-of-print]

Chu, S.-C., and Choi, S. M. (2010). Social capital and self-presentation on social networking sites: a comparative study of Chinese and American young generations. Chin. J. Commun. 3, 402–420. doi: 10.1080/17544750.2010.516575

Cleveland, D. J. (2016). Brand personality and organization-public relationships: impacting dimensions by choosing a temperament for communication.

Crone, E. A. M., and Konijn, E. A. (2018). Media use and brain development during adolescence. Nat. Commun. 9:588. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03126-x

Del Giudice, M., Nicotra, M., Romano, M., and Schillaci, C. E. (2016). Entrepreneurial performance of principal investigators and country culture: relations and influences. J. Technol. Transfer. 42, 320–337.

Dunbar, R. I., and Shultz, S. (2007). Evolution in the social brain. Science 317, 1344–1347. doi: 10.1126/science.1145463

Fischer, N. L., Peres, R., and Fiorani, M. (2018). Frontal alpha asymmetry and theta oscillations associated with information sharing intention. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12:166. doi: 10.3389/fnbeh.2018.00166

Han, M. C., and Kim, Y. (2018). How culture and friends affect acceptance of social media commerce and purchase intentions: a comparative study of consumers in the U.S. and China. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 30, 326–335. doi: 10.1080/08961530.2018.1466226

Hodgson, P. (2018). “Global learners’ behavior on news in social media platforms through a MOOC,” in New Media for Educational Change. Educational Communications and Technology Yearbook. eds. L. Deng, W. Ma, and C. Fong (Singapore: Springer), 141–148.

Hoehle, H., Zhang, X., and Venkatesh, V. (2015). An espoused cultural perspective to understand continued intention to use mobile applications: a four-country study of mobile social media application usability. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 24, 337–359. doi: 10.1057/ejis.2014.43

Hopkins, L. (2009). Media and migration: a review of the field. Australia and New Zealand Communication Association.

Hu, S., Jibao, G., Liu, H., and Huang, Q. (2017). The moderating role of social media usage in the relationship among multicultural experiences, cultural intelligence, and individual creativity. Inf. Technol. People 30, 265–281. doi: 10.1108/ITP-04-2016-0099

Hu, S., Liu, H., Zhang, S., and Wang, G. (2020). Proactive personality and cross-cultural adjustment: roles of social media usage and cultural intelligence. Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 74, 42–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.10.002

Huang, C.-M., and Park, D. (2013). Cultural influences on Facebook photographs. Int. J. Psychol. 48, 334–343. doi: 10.1080/00207594.2011.649285

Ji, Y., and Bates, B. R. (2020). Measuring intercultural/international outgroup favoritism: comparing two measures of cultural cringe. Asian J. Commun. 30, 141–154. doi: 10.1080/01292986.2020.1738511

Jin, D. Y., and Yoon, K. (2016). The social mediascape of transnational Korean pop culture: Hallyu 2.0 as spreadable media practice. New Media Soc. 18, 1277–1292. doi: 10.1177/1461444814554895

Kotik-Friedgut, B., and Ardila, A. (2019). A.r. luria’s cultural neuropsychology in the 21st century. Cult. Psychol. 26, 274–286. doi: 10.1177/1354067X19861053

Li, Y., Wang, X., Lin, X., and Hajli, M. (2018). Seeking and sharing health information on social media: a net valence model and cross-cultural comparison. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 126, 28–40. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2016.07.021

Meshi, D., Tamir, D. I., and Heekeren, H. R. (2015). The emerging neuroscience of social media. Trends Cogn. Sci. 19, 771–782. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.004

Meza, V. X., and Park, H. W. (2014). Globalization of cultural products: a webometric analysis of Kpop in Spanish-speaking countries. Qual. Quant. 49, 1345–1360. doi: 10.1007/s11135-014-0047-2

Moffitt, T. E., Caspi, A., and Rutter, M. (2006). Measured gene-environment interactions in psychopathology: concepts, research strategies, and implications for research, intervention, and public understanding of genetics. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 1, 5–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00002.x

Montag, C., Markowetz, A., Blaszkiewicz, K., Andone, I., Lachmann, B., Sariyska, R., et al. (2017). Facebook usage on smartphones and gray matter volume of the nucleus Accumbens. Behav. Brain Res. 329, 221–228. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2017.04.035

Motoki, K., Suzuki, S., Kawashima, R., and Sugiura, M. (2020). A combination of self-reported data and social-related neural measures forecasts viral marketing success on social media. J. Interact. Mark. 52, 99–117. doi: 10.1016/j.intmar.2020.06.003

Pang, H. (2020). Is active social media involvement associated with cross-culture adaption and academic integration among boundary-crossing students? Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 79, 71–81.

Papa, A., Chierici, R., Ballestra, L. V., Meissner, D., and Orhan, M. A. (2020). Harvesting reflective knowledge exchange for inbound open innovation in complex collaborative networks: an empirical verification in Europe. J. Knowl. Manag. doi: 10.1108/JKM-04-2020-0300 [Epub ahead of print]

Santoro, G., Mazzoleni, A., Quaglia, R., and Solima, L. (2021). Does age matter? The impact of SMEs age on the relationship between knowledge sourcing strategy and internationalization. J. Bus. Res. 128, 779–787. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.05.021

Sherman, L. E., Greenfield, P. M., Hernandez, L. M., and Dapretto, M. (2018). Peer influence via Instagram: effects on brain and behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Child Dev. 89, 37–47. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12838

Thomas, J., Al-Shehhi, A., Al-Ameri, M., and Grey, I. (2019). We tweet Arabic; I tweet English: self-concept, language and social media. Heliyon 5:E02087. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2019.e02087

Wang, S., and Chin, T. (2020). A stratified system of knowledge and knowledge icebergs in cross-cultural business models: synthesizing ontological and epistemological views. J. Int. Manag. 26:100780. doi: 10.1016/j.intman.2020.100780

Wang, X., Riaz, M., Haider, S., Alam, K., Sherani,, and Yang, M. (2021). Information sharing on social media by multicultural individuals: experiential, motivational, and network factors. J. Glob. Inf. Manag. 29, 1–24. doi: 10.4018/JGIM.20211101.oa22

Xu, W. W., Park, J. Y., and Park, H. W. (2015). The networked cultural diffusion of Korean wave. Online Inf. Rev. 39, 43–60. doi: 10.1108/OIR-07-2014-0160

Xu, W. W., Park, J.-y., and Park, H. W. (2016). Longitudinal dynamics of the cultural diffusion of Kpop on YouTube. Qual. Quant. 51, 1859–1875. doi: 10.1007/s11135-016-0371-9

Yang, W., and Xu, Q. (2018). “A comparative study of the use of media by Chinese and American governments in risk communication — the use of social media.” 2018 International Joint Conference on Information, Media and Engineering (ICIME).

Yau, A., Marder, B., and O’Donohoe, S. (2019). The role of social media in negotiating identity during the process of acculturation. Inf. Technol. People. [Epub ahead-of-print].

Keywords: cross-culture communication, social media, cultural psychology, neuroscience, cultural neuropsychology, social neuroscience

Citation: Yuna D, Xiaokun L, Jianing L and Lu H (2022) Cross-Cultural Communication on Social Media: Review From the Perspective of Cultural Psychology and Neuroscience. Front. Psychol . 13:858900. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.858900

Received: 20 January 2022; Accepted: 14 February 2022; Published: 08 March 2022.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2022 Yuna, Xiaokun, Jianing and Lu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Han Lu, [email protected]

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Social Media Seen as Mostly Good for Democracy Across Many Nations, But U.S. is a Major Outlier

2. Views of social media and its impacts on society

Table of contents.

- Most do not think they can influence politics in their country

- The perceived impacts of the internet and social media on society

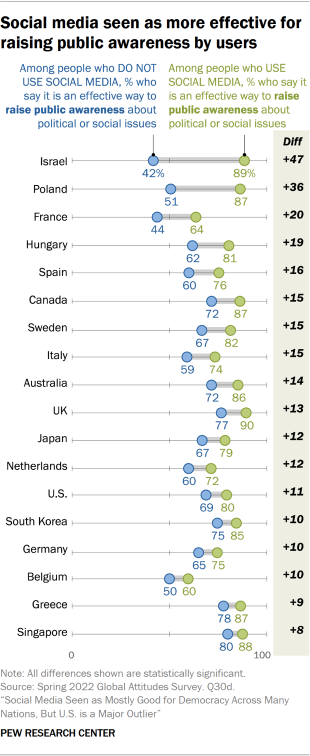

- Majorities view social media as a way to raise awareness among the public and elected officials

- Widespread smartphone ownership while very few do not own a mobile phone at all

- Most say they use social media sites

- Frequent posting about social or political issues on social media is uncommon

- Acknowledgments

- Appendix A: Classifying democracies

- Appendix B: Negative Impact of the Internet and Social Media Index

- Appendix C: Political categorization

- Classifying parties as populist

- Classifying parties as left, right or center

- Appendix E: Country-specific examples of smartphones

- Appendix F: Country-specific examples of social media sites

- Pew Research Center’s Spring 2022 Global Attitudes Survey

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

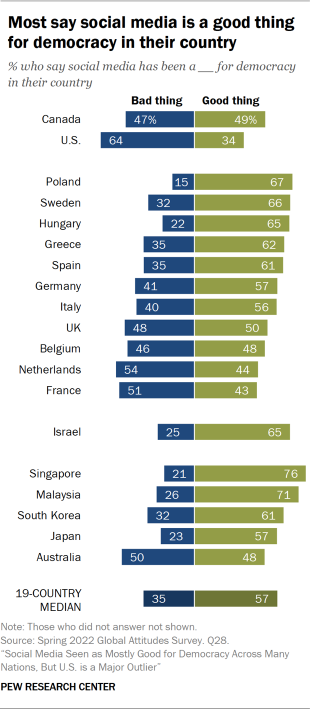

When asked whether social media is a good or bad thing for democracy in their country, a median of 57% across 19 countries say that it is a good thing. In almost every country, close to half or more say this, with the sentiment most common in Singapore, where roughly three-quarters believe social media is a good thing for democracy in their country. However, in the Netherlands and France, about four-in-ten agree. And in the U.S., only around a third think social media is positive for democracy – the smallest share among all 19 countries surveyed.

In eight countries, those who believe that the political system in their country allows them to have an influence on politics are also more likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy. This gap is most evident in Belgium, where 62% of those who feel their political system allows them to have a say in politics also say that social media is a good thing for democracy in their country, compared with 44% among those who say that their political system does not allow them much influence on politics.

Those who view the spread of false information online as a major threat to their country are less likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy, compared with those who view the spread of misinformation online as either a minor threat or not a threat at all. This is most clearly observed in the Netherlands, where only four-in-ten (39%) among those who see the spread of false information online as a major threat say that social media has been a good thing for democracy in their country, as opposed to the nearly six-in-ten (57%) among those who do not consider the spread of misinformation online to be a threat who say the same. This pattern is evident in eight other countries as well.

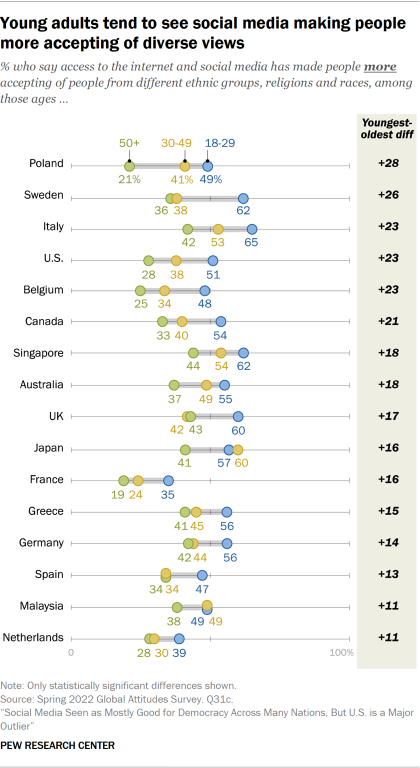

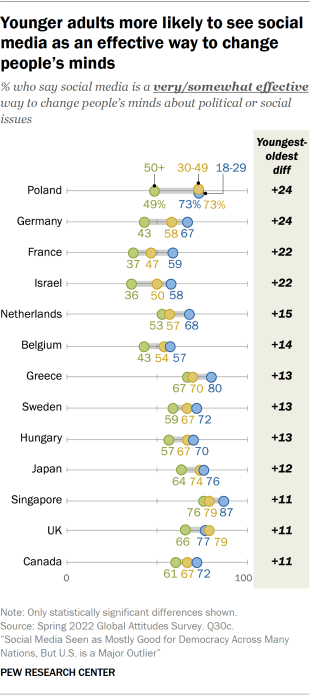

Views also vary by age. Older adults in 12 countries are less likely to say that social media is a good thing for democracy in their country when compared to their younger counterparts. In Japan, France, Israel, Hungary, the UK and Australia, the gap between the youngest and oldest age groups is at least 20 percentage points and ranges as high as 41 points in Poland, where nearly nine-in-ten (87%) younger adults say that social media has been a good thing for democracy in the country and only 46% of adults over 50 say the same.

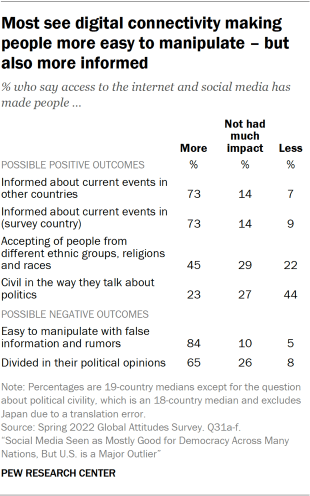

The publics surveyed believe the internet and social media are affecting societies. Across the six issues tested, few tend to say they see no changes due to increased connectivity – instead seeing things changing both positively and negatively – and often both at the same time.

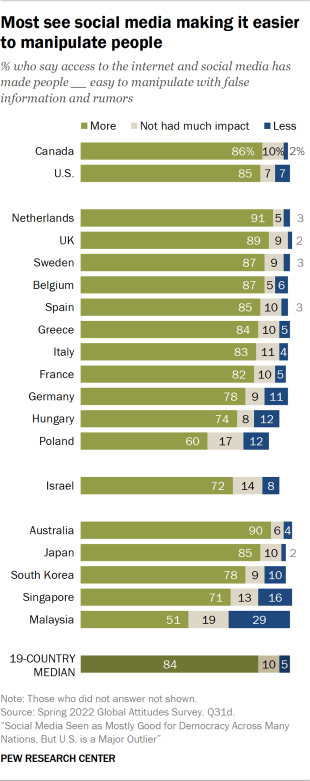

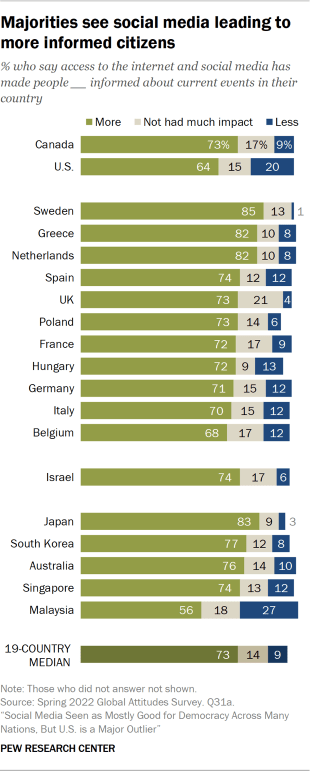

A median of 84% say technological connectivity has made people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors – the most among the six issues tested. Despite this, medians of 73% describe people being more informed about both current events in other countries and about events in their own country. Indeed, in most countries, those who think social media has made it easier to manipulate people with misinformation and rumors are also more likely to think that social media has made people more informed.

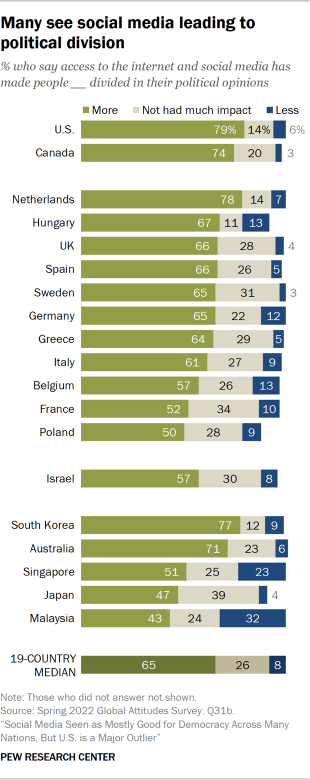

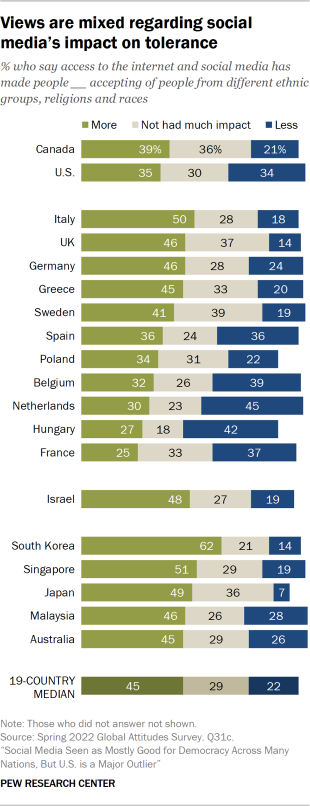

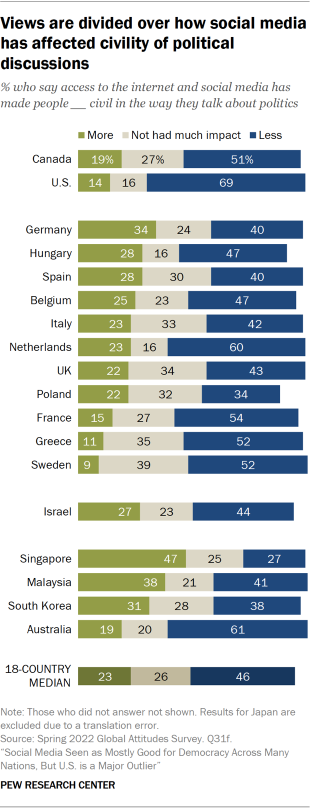

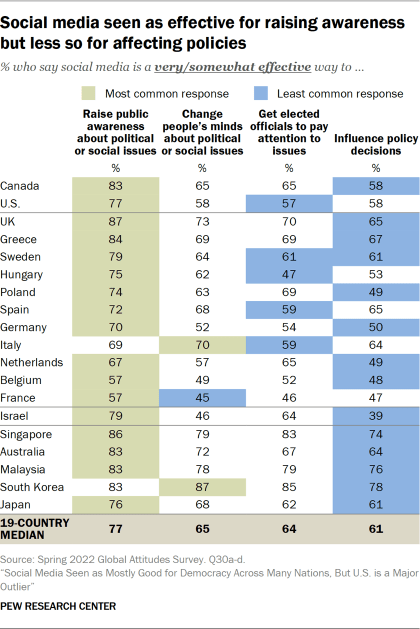

When it comes to politics, the internet and social media are generally seen as disruptive, with a median of 65% saying that people are now more divided in their political opinions. Some of this may be due to the sense – shared by a median of 44% across the 19 countries – that access to the internet and social media has led people to be less civil in the way they talk about politics. Despite this, slightly more people (a median of 45%) still say connectivity has made people more accepting of people from different ethnic groups, religions and races than say it has made people less accepting (22%) or had no effect (29%).

There is widespread concern over misinformation – and a sense that people are more susceptible to manipulation

Previously reported results indicate that a median of 70% across the 19 countries surveyed believe that the spread of false information online is a major threat to their country. In places like Canada, Germany and Malaysia, more people name this as a threat than say the same of any of the other issues asked about.

This sense of threat is related to the widespread belief that people today are now easier to manipulate with false information and rumors thanks to the internet and social media. Around half or more in every country surveyed shares this view. And in places like the Netherlands, Australia and the UK, around nine-in-ten see people as more manipulable.

In many places, younger people – who tend to be more likely to use social media (for more on usage, see Chapter 3 ) – are also more likely to say it makes people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors. For example, in South Korea, 90% of those under age 30 say social media makes people easier to manipulate, compared with 65% of those 50 and older. (Interestingly, U.S.-focused research has found older adults are more likely to share misinformation than younger ones.) People with more education are also often more likely than those with less education to say that social media has led to people being easier to manipulate.

In 2018, when Pew Research Center asked a similar question about whether access to mobile phones, the internet and social media has made people easier to manipulate with false information and rumors, the results were largely similar. Across the 11 emerging economies surveyed as part of that project , at least half in every country thought this was the case and in many places, around three-quarters or more saw this as an issue. Large shares in many places were also specifically concerned that people in their country might be manipulated by domestic politicians. For more on how the two surveys compare, see “ In advanced and emerging economies, similar views on how social media affects democracy and society .”

Spotlight on the U.S.: Attitudes and experiences with misinformation

Misinformation has long been seen as a source of concern for Americans. In 2016 , for example, in the wake of the U.S. presidential election, 64% of U.S. adults thought completely made-up news had caused a great deal of confusion about the basic facts of current events. At the time, around a third felt that they often encountered political news online that was completely made up and another half said they often encountered news that was not fully accurate. Moreover, about a quarter (23%) said they had shared such stories – whether knowingly or not.

When asked in 2019 who was the cause of made-up news, Americans largely singled out two groups of people: political leaders (57%) and activists (53%). Fewer placed blame on journalists (36%), foreign actors (35%) or the public (26%). A large majority of Americans that year (82%) also described themselves as either “very” or “somewhat” concerned about the potential impact of made-up news on the 2020 presidential election. People who followed political and election news more closely and those with higher levels of political knowledge also tended to be more concerned.

Among adult American Twitter users in 2021, in particular, there was widespread concern about misinformation: 53% said inaccurate or misleading information is a major problem on the platform and 33% reported seeing a lot of that type of content when using the site.

As of 2021 , around half (48%) of Americans thought the government should take steps to restrict false information, even if it meant losing freedom to access and publish content – a share that had increased somewhat substantially since 2018, when 39% felt the same.

Most say people are more informed about current events – foreign and domestic – thanks to social media and the internet

A majority in every country surveyed thinks that access to the internet and social media has made people in their country more informed about domestic current events. In Sweden, Japan, Greece and the Netherlands, around eight-in-ten or more share this view, while in Malaysia, a smaller majority (56%) says the same.

Younger adults tend to see social media making people more informed than older adults do. Older adults, for their part, don’t necessarily see the internet and social media making people less informed about what’s happening in their country; rather, they’re somewhat more likely to describe these platforms as having little effect on people’s information levels. In the case of the U.S., for example, 71% of adults under 30 say social media has made people more informed about current events in the U.S., compared with 60% of those ages 50 and older. But those ages 50 and older are about twice as likely to say social media has not had much impact on how informed people are compared with those under 30: 19% vs. 11%, respectively.

In seven of the surveyed countries, people with higher levels of education are more likely than those with lower levels to see social media informing the public on current events in their own country.

Majorities in every country also agree that the internet and social media are making people more informed about current events happening in other countries. The two questions are extremely highly correlated ( r = 0.94), meaning that in most places where people say social media is making people more informed about domestic events, they also say the same of international events. (See the topline for detailed results for both questions, by country.)

In the 2018 survey of emerging economies , results of a slightly different question also found that a majority in every country – and around seven-in-ten or more in most places – said people were more informed thanks to social media, the internet and smartphones, rather than less.

In some countries, those who think social media has made it easier to manipulate people with misinformation and rumors are also more likely to think that social media has made people more informed. This finding, too, was similar in the 2018 11-country study of emerging economies: Generally speaking, individuals who are most attuned to the potential benefits technology can bring to the political domain are also the ones most anxious about the possible harms.

Spotlight on the U.S.: Social media use and news consumption

In the U.S. , around half of adults say they either get news often (17%) or sometimes (33%) from social media. When it comes to where Americans regularly get news on social media, Facebook outpaces all other social media sites. Roughly a third of U.S. adults (31%) say they regularly get news from Facebook. While Twitter is only used by about three-in-ten U.S. adults (27%), about half of its users (53%) turn to the site to regularly get news there. And a quarter of U.S. adults regularly get news from YouTube, while smaller shares get news from Instagram (13%), TikTok (10%) or Reddit (8%). Notably, TikTok has seen rapid growth as a source of news among younger Americans in recent years.

On several social media sites asked about, adults under 30 make up the largest share of those who regularly get news on the site. For example, half or more of regular news consumers on Snapchat (67%), TikTok (52%) or Reddit (50%) are ages 18 to 29.

While this survey finds that 64% of Americans think the public has become more informed thanks to social media, results of Center analyses do show that Americans who mainly got election and political information on social media during the 2020 election were less knowledgeable and less engaged than those who primarily got their news through other methods (like cable TV, print, etc.).

Majorities or pluralities tend to see social media leading to more political divisions

Around half or more in almost every country surveyed think social media has made people more divided in their political opinions. The U.S., South Korea and the Netherlands are particularly likely to hold this view. As a separate analysis shows, the former two also stand out for being the countries where people are most likely to report conflicts between people who support different political parties . While perceived political division in the Netherlands is somewhat lower, it, too, stands apart: Between 2021 and 2022, the share who said there were conflicts increased by 23 percentage points – among the highest year-on-year shifts evident in the survey.

More broadly, across each of the countries surveyed, people who see social division between people who support different political parties, are, in general, more likely to see social media leading people to be more divided in their political opinions.

In a number of countries, younger people are somewhat more likely to see social media enlarging political differences than older people. More educated people, too, often see social media exacerbating political divisions more than those with less education.

Similarly, in the survey of 11 emerging economies conducted in 2018, results of a slightly different question indicated that around four-in-ten or more in every country – and a majority in most places – thought social media had made people more divided.

Publics diverge over whether social media has made people more accepting of differences

There is less consensus over what role social media has played when it comes to tolerance: A 19-country median of 45% say it has made people more accepting of people from different ethnic backgrounds, religions and races, while a median of 22% say it has made them less so, and 29% say that it has not had much impact either way.

South Korea, Singapore, Italy and Japan are the most likely to see social media making people more tolerant. On the flip side, the Netherlands and Hungary stand out as the two countries where a plurality says the internet and social media have made people less accepting of people with racial or religious differences. Most other societies are somewhat divided, as in the case of the U.S., where around a third of the public falls into each of the three groups.