- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Lung cancer

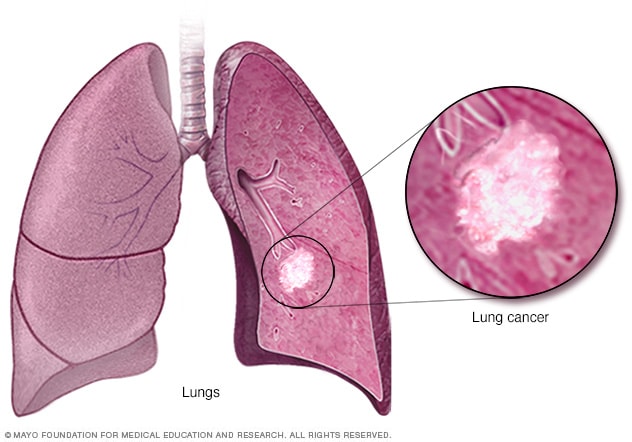

Lung cancer begins in the cells of the lungs.

Lung cancer is a kind of cancer that starts as a growth of cells in the lungs. The lungs are two spongy organs in the chest that control breathing.

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer deaths worldwide.

People who smoke have the greatest risk of lung cancer. The risk of lung cancer increases with the length of time and number of cigarettes smoked. Quitting smoking, even after smoking for many years, significantly lowers the chances of developing lung cancer. Lung cancer also can happen in people who have never smoked.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Lung cancer typically doesn't cause symptoms early on. Symptoms of lung cancer usually happen when the disease is advanced.

Signs and symptoms of lung cancer that happen in and around the lungs may include:

- A new cough that doesn't go away.

- Chest pain.

- Coughing up blood, even a small amount.

- Hoarseness.

- Shortness of breath.

Signs and symptoms that happen when lung cancer spreads to other parts of the body may include:

- Losing weight without trying.

- Loss of appetite.

- Swelling in the face or neck.

When to see a doctor

Make an appointment with your doctor or other healthcare professional if you have any symptoms that worry you.

If you smoke and haven't been able to quit, make an appointment. Your healthcare professional can recommend strategies for quitting smoking. These may include counseling, medicines and nicotine replacement products.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

Get Mayo Clinic cancer expertise delivered to your inbox.

Subscribe for free and receive an in-depth guide to coping with cancer, plus helpful information on how to get a second opinion. You can unsubscribe at any time. Click here for an email preview.

Error Select a topic

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing

Your in-depth coping with cancer guide will be in your inbox shortly. You will also receive emails from Mayo Clinic on the latest about cancer news, research, and care.

If you don’t receive our email within 5 minutes, check your SPAM folder, then contact us at [email protected] .

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

Lung cancer happens when cells in the lungs develop changes in their DNA. A cell's DNA holds the instructions that tell a cell what to do. In healthy cells, the DNA gives instructions to grow and multiply at a set rate. The instructions tell the cells to die at a set time. In cancer cells, the DNA changes give different instructions. The changes tell the cancer cells to make many more cells quickly. Cancer cells can keep living when healthy cells would die. This causes too many cells.

The cancer cells might form a mass called a tumor. The tumor can grow to invade and destroy healthy body tissue. In time, cancer cells can break away and spread to other parts of the body. When cancer spreads, it's called metastatic cancer.

Smoking causes most lung cancers. It can cause lung cancer in both people who smoke and in people exposed to secondhand smoke. But lung cancer also happens in people who never smoked or been exposed to secondhand smoke. In these people, there may be no clear cause of lung cancer.

How smoking causes lung cancer

Researchers believe smoking causes lung cancer by damaging the cells that line the lungs. Cigarette smoke is full of cancer-causing substances, called carcinogens. When you inhale cigarette smoke, the carcinogens cause changes in the lung tissue almost immediately.

At first your body may be able to repair this damage. But with each repeated exposure, healthy cells that line your lungs become more damaged. Over time, the damage causes cells to change and eventually cancer may develop.

Types of lung cancer

Lung cancer is divided into two major types based on the appearance of the cells under a microscope. Your healthcare professional makes treatment decisions based on which major type of lung cancer you have.

The two general types of lung cancer include:

- Small cell lung cancer. Small cell lung cancer usually only happens in people who have smoked heavily for years. Small cell lung cancer is less common than non-small cell lung cancer.

- Non-small cell lung cancer. Non-small cell lung cancer is a category that includes several types of lung cancers. Non-small cell lung cancers include squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and large cell carcinoma.

Risk factors

A number of factors may increase the risk of lung cancer. Some risk factors can be controlled, for instance, by quitting smoking. Other factors can't be controlled, such as your family history.

Risk factors for lung cancer include:

Your risk of lung cancer increases with the number of cigarettes you smoke each day. Your risk also increases with the number of years you have smoked. Quitting at any age can significantly lower your risk of developing lung cancer.

Exposure to secondhand smoke

Even if you don't smoke, your risk of lung cancer increases if you're around people who are smoking. Breathing the smoke in the air from other people who are smoking is called secondhand smoke.

Previous radiation therapy

If you've had radiation therapy to the chest for another type of cancer, you may have an increased risk of developing lung cancer.

Exposure to radon gas

Radon is produced by the natural breakdown of uranium in soil, rock and water. Radon eventually becomes part of the air you breathe. Unsafe levels of radon can build up in any building, including homes.

Exposure to cancer-causing substances

Workplace exposure to cancer-causing substances, called carcinogens, can increase your risk of developing lung cancer. The risk may be higher if you smoke. Carcinogens linked to lung cancer risk include asbestos, arsenic, chromium and nickel.

Family history of lung cancer

People with a parent, sibling or child with lung cancer have an increased risk of the disease.

Complications

Lung cancer can cause complications, such as:

Shortness of breath

People with lung cancer can experience shortness of breath if cancer grows to block the major airways. Lung cancer also can cause fluid to collect around the lungs and heart. The fluid makes it harder for the affected lung to expand fully when you inhale.

Coughing up blood

Lung cancer can cause bleeding in the airway. This can cause you to cough up blood. Sometimes bleeding can become severe. Treatments are available to control bleeding.

Advanced lung cancer that spreads can cause pain. It may spread to the lining of a lung or to another area of the body, such as a bone. Tell your healthcare professional if you experience pain. Many treatments are available to control pain.

Fluid in the chest

Lung cancer can cause fluid to accumulate in the chest, called pleural effusion. The fluid collects in the space that surrounds the affected lung in the chest cavity, called the pleural space.

Pleural effusion can cause shortness of breath. Treatments are available to drain the fluid from your chest. Treatments can reduce the risk that pleural effusion will happen again.

Cancer that spreads to other parts of the body

Lung cancer often spreads to other parts of the body. Lung cancer may spread to the brain and the bones.

Cancer that spreads can cause pain, nausea, headaches or other symptoms depending on what organ is affected. Once lung cancer has spread beyond the lungs, it's generally not curable. Treatments are available to decrease symptoms and to help you live longer.

There's no sure way to prevent lung cancer, but you can reduce your risk if you:

Don't smoke

If you've never smoked, don't start. Talk to your children about not smoking so that they can understand how to avoid this major risk factor for lung cancer. Begin conversations about the dangers of smoking with your children early so that they know how to react to peer pressure.

Stop smoking

Stop smoking now. Quitting reduces your risk of lung cancer, even if you've smoked for years. Talk to your healthcare team about strategies and aids that can help you quit. Options include nicotine replacement products, medicines and support groups.

Avoid secondhand smoke

If you live or work with a person who smokes, urge them to quit. At the very least, ask them to smoke outside. Avoid areas where people smoke, such as bars. Seek out smoke-free options.

Test your home for radon

Have the radon levels in your home checked, especially if you live in an area where radon is known to be a problem. High radon levels can be fixed to make your home safer. Radon test kits are often sold at hardware stores and can be purchased online. For more information on radon testing, contact your local department of public health.

Avoid carcinogens at work

Take precautions to protect yourself from exposure to toxic chemicals at work. Follow your employer's precautions. For instance, if you're given a face mask for protection, always wear it. Ask your healthcare professional what more you can do to protect yourself at work. Your risk of lung damage from workplace carcinogens increases if you smoke.

Eat a diet full of fruits and vegetables

Choose a healthy diet with a variety of fruits and vegetables. Food sources of vitamins and nutrients are best. Avoid taking large doses of vitamins in pill form, as they may be harmful. For instance, researchers hoping to reduce the risk of lung cancer in people who smoked heavily gave them beta carotene supplements. Results showed the supplements increased the risk of cancer in people who smoke.

Exercise most days of the week

If you don't exercise regularly, start out slowly. Try to exercise most days of the week.

Lung cancer care at Mayo Clinic

Living with lung cancer?

Connect with others like you for support and answers to your questions in the Lung Cancer support group on Mayo Clinic Connect, a patient community.

Lung Cancer Discussions

90 Replies Sun, Apr 21, 2024

37 Replies Fri, Apr 19, 2024

104 Replies Thu, Apr 18, 2024

- Non-small cell lung cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1450. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Small cell lung cancer. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=1&id=1462. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Niederhuber JE, et al., eds. Cancer of the lung: Non-small cell lung cancer and small cell lung cancer. In: Abeloff's Clinical Oncology. 6th ed. Elsevier; 2020. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Non-small cell lung cancer treatment (PDQ) – Patient version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/patient/non-small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Small cell lung cancer treatment (PDQ) – Patient version. National Cancer Institute. https://www.cancer.gov/types/lung/patient/small-cell-lung-treatment-pdq. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Lung cancer – non-small cell. Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/lung-cancer/view-all. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Lung cancer – small cell. Cancer.Net. https://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/33776/view-all. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Detterbeck FC, et al. Executive Summary: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed.: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013; doi:10.1378/chest.12-2377.

- Palliative care. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. https://www.nccn.org/guidelines/guidelines-detail?category=3&id=1454. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Lung cancer. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/lung-cancer. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Cairns LM. Managing breathlessness in patients with lung cancer. Nursing Standard. 2012; doi:10.7748/ns2012.11.27.13.44.c9450.

- Warner KJ. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. Jan. 13, 2020.

- Brown AY. Allscripts EPSi. Mayo Clinic. July 30, 2019.

- Searching for cancer centers. American College of Surgeons. https://www.facs.org/search/cancer-programs. Accessed Dec. 4, 2023.

- Temel JS, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1000678.

- Dunning J, et al. Microlobectomy: A novel form of endoscopic lobectomy. Innovations. 2017; doi:10.1097/IMI.0000000000000394.

- Leventakos K, et al. Advances in the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer: Focus on nivolumab, pembrolizumab and atezolizumab. BioDrugs. 2016; doi:10.1007/s40259-016-0187-0.

- Dong H, et al. B7-H1, a third member of the B7 family, co-stimulates T-cell proliferation and interleukin-10 secretion. Nature Medicine. 1999;5:1365.

- Aberle DR, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. New England Journal of Medicine. 2011; doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1102873.

- Infographic: Lung Cancer

- Lung cancer surgery

- Lung nodules: Can they be cancerous?

- Super Survivor Conquers Cancer

Associated Procedures

- Ablation therapy

- Brachytherapy

- Bronchoscopy

- Chemotherapy

- Lung cancer screening

- Positron emission tomography scan

- Proton therapy

- Radiation therapy

- Stop-smoking services

News from Mayo Clinic

- Science Saturday: Study finds senescent immune cells promote lung tumor growth June 17, 2023, 11:00 a.m. CDT

- Era of hope for patients with lung cancer Nov. 16, 2022, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: Survivorship after surgery for lung cancer Nov. 15, 2022, 01:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Understanding lung cancer Nov. 02, 2022, 04:00 p.m. CDT

- Lung cancer diagnosis innovation leads to higher survival rates Nov. 02, 2022, 02:30 p.m. CDT

Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, Mayo Clinic in Phoenix/Scottsdale, Arizona, and Mayo Clinic in Jacksonville, Florida, have been recognized among the top Pulmonology hospitals in the nation for 2023-2024 by U.S. News & World Report.

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Make twice the impact

Your gift can go twice as far to advance cancer research and care!

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 22 May 2019

Presentation of lung cancer in primary care

- D. P. Weller 1 ,

- M. D. Peake 2 &

- J. K. Field 3

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine volume 29 , Article number: 21 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

5196 Accesses

17 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Respiratory signs and symptoms

- Signs and symptoms

Survival from lung cancer has seen only modest improvements in recent decades. Poor outcomes are linked to late presentation, yet early diagnosis can be challenging as lung cancer symptoms are common and non-specific. In this paper, we examine how lung cancer presents in primary care and review roles for primary care in reducing the burden from this disease. Reducing rates of smoking remains, by far, the key strategy, but primary care practitioners (PCPs) should also be pro-active in raising awareness of symptoms, ensuring lung cancer risk data are collected accurately and encouraging reluctant patients to present. PCPs should engage in service re-design and identify more streamlined diagnostic pathways—and more readily incorporate decision support into their consulting, based on validated lung cancer risk models. Finally, PCPs should ensure they are central to recruitment in future lung cancer screening programmes—they are uniquely placed to ensure the right people are targeted for risk-based screening programmes. We are now in an era where treatments can make a real difference in early-stage lung tumours, and genuine progress is being made in this devastating illness—full engagement of primary care is vital in effecting these improvements in outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review of interventions to recognise, refer and diagnose patients with lung cancer symptoms

Mohamad M. Saab, Megan McCarthy, … Josephine Hegarty

Implications of incidental findings from lung screening for primary care: data from a UK pilot

Emily C. Bartlett, Jonathan Belsey, … Anand Devaraj

Personalised lung cancer risk stratification and lung cancer screening: do general practice electronic medical records have a role?

Bhautesh Dinesh Jani, Michael K. Sullivan, … Frank M. Sullivan

Introduction

Lung cancer poses a significant public health burden around the world; it is the most common cause of cancer mortality in the UK and it accounts for >20% of cancer deaths. 1 There is significant variation in survival rates around the world and this has been largely attributed to the stage at which the cancer is diagnosed. 2 The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership has demonstrated that survival rates in the UK lag behind those of other countries, and late diagnosis is thought to be a major underlying factor. 3 , 4 Importantly, patients with early-stage disease have a much better prognosis; stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer can have a 5-year survival rate as high as 75%. 5 Even within the UK, however, there is wide variation in lung cancer survival rates and in the proportion of patients diagnosed with early-stage disease. 6

In the UK, most cancers present symptomatically in primary care (most commonly to a general practitioner, or ‘GP’, the medical lead of a primary care team), and the diagnosis is made after a referral for either investigations or directly to secondary care. 7 Many of the symptoms of lung cancer are very common but non-specific in primary care practice: these include chest pain, cough and breathlessness; 8 hence, lung cancer poses a very significant diagnostic challenge—a primary care practitioner (PCP) working full time is likely to only diagnose 1 or 2 cases per year. Further, lung cancer often emerges on a background of chronic respiratory disease and symptoms of chronic cough—typically in patients who smoke. It can be very difficult to identify changes in these chronic symptoms that might indicate the development of a lung tumour.

Smoking remains the principal aetiological factor and smoking cessation is the key public health initiative to reduce mortality from this disease; 9 indeed, at almost any age smoking cessation can produce health benefits. Hence, public health campaigns to promote smoking cessation, supplemented by strategies in primary care based on nicotine replacement therapies should be encouraged. 10 The role of e-cigarettes is not yet fully understood, 11 although any strategy that reduces exposure to tobacco smoke has a potential for producing significant benefits.

How do patients respond to lung cancer symptoms?

There is a significant body of research around patient response to symptoms that might potentially indicate lung cancer. Because symptoms often present within the context of chronic respiratory symptomatology, changes associated with the development of a tumour may go un-noticed or be dismissed. 8 It is known that patients often delay their help seeking through a range of psychological mechanisms including denial and nihilism—hence, there can often be significant delays before patients present to primary care. 12 , 13

There is evidence for variation in the timeliness of presentation of lung cancer in between countries; people with lung cancer often have symptoms for a considerable period of time before they present to primary care and this is a major source of delay in the diagnostic process with potential adverse impact on survival; 14 , 15 this patient interval does, however, vary between studies. It is important that PCPs understand some of the psychological mechanisms that either promote or inhibit early presentation among their patients.

Public awareness of lung cancer

Over the past few years, there have been campaigns run throughout the UK designed to make the public more aware of symptoms associated with lung cancer—for example the ‘Be clear on Cancer’ campaign run by Public Health England and ‘Diagnose Cancer Early’ in Scotland 16 , 17 (see Fig. 1 ). These campaigns have demonstrated an ability to diagnose additional cancers and effect modest increases in the proportion of patients having tumours diagnosed at stages where they are amenable to resection. 18 , 19

Posters used in the ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ campaign

Of course, lung cancer early detection programmes need to be focussed on the hard-to-reach population and those who will benefit most from involvement; there are often concerns expressed over burdening services with patients with insignificant symptoms 18 and an emerging consensus that all stakeholders should be closely engaged in the campaigns. Nevertheless, available evidence suggests that lung cancer could be diagnosed earlier through these public awareness campaigns, 19 particularly when associated with systems to help primary care physicians risk stratify their patients for lung cancer more effectively—indeed, further work to identify patients who might benefit from targeted interventions should be a priority.

Community-based social marketing interventions have a potential key role; 20 they can increase the likelihood of patients attending PCPs and increase primary care diagnostic activity (such as chest X-ray referrals)—as well as increases in lung cancer diagnostic rates. The level of suspicion at which PCPs consider a referral is a key factor in response to these campaigns—and there are concerns over ‘system overload’ through encouragement to present with symptoms. 13 Ideally, campaigns might preferentially target those at greater risk of lung cancer, such as people with significant smoking histories or occupational exposure.

Primary care response to lung cancer symptoms

In the UK, GPs will on average only diagnose one or two cases of lung cancer per year (if they are in full-time practice). 21 However, during that year, GPs will see hundreds of patients with common symptoms, such as cough, breathlessness and chest pain—hence, there are significant difficulties in identifying, diagnosing and referring these patients in a timely manner.

The 2015 NICE lung cancer guidelines on recognition and referral 22 have underpinned some important strategies to enhance timely lung cancer diagnosis; in many regions of the UK, there are now accelerated diagnostic pathways that assist GPs in identifying and referring patients appropriately. 23 Audit data demonstrate that there are typically several consultations prior to a diagnosis of lung cancer being made. 24 Evidence from significant event analysis in the UK has suggested that there is timely recognition and referral of symptoms in primary care; 25 longer intervals are typically attributed to factors such as X-rays being reported as normal, patient-mediated factors and presentations complicated by co-morbidity. The importance of safety netting has also been emphasised in presentations where a diagnosis of lung cancer is possible. 26

There needs to be continued work to counteract the ‘nihilism’ associated with lung cancer; PCPs are very well aware of patients who may suspect they have lung cancer but fail to present either because they blame themselves (through a history of smoking) or because they believe that if a cancer is diagnosed there is little that can be done about it. 27 This, coupled with the tendency for patients in the UK to be concerned about ‘bothering the doctor’, 28 can have detrimental effects on early diagnosis.

While public campaigns can do much to overcome barriers to presentation, it is vital that PCPs become more pro-active in achieving more timely diagnosis in their practice populations. It is been recommended that they should recognise the psychological mechanisms that might underlie patient delay and tackle nihilistic attitudes through educational and motivational strategies. 29 Indeed, there is cause for cautious optimism with new treatments, and this should be conveyed to patients; for example, the use of stereotactic radiotherapy and volume-sparing surgery means that patients who previously could not be offered curative treatment due to co-morbidities are often now eligible. 30

Audits that systematically identify at-risk patients who may be failing to present are a potential way forward; interventions which identify and target high-risk patients appear feasible in primary care. 31 Crucially, patients should be reassured that PCPs are always happy to see them if they are worried about potential cancer symptoms.

Risk assessment and lung cancer

It is vital in assessing lung cancer risk to look carefully at lifestyle factors and past medical history; only one in seven cases of lung cancer occur in people who have never smoked, and the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease doubles the risk independent of smoking history. 32 A previous history of head and neck, bladder and renal cancers and other factors such as exposure to asbestos or living in high radon exposure areas are all important in lung cancer risk assessment. Family history produces an excess of risk and should be included in risk assessment—as should the symptom of fatigue, a common feature of lung cancer. Cancer decision support tools such as the ‘Caper’ instrument or ‘Q cancer’ have emerged in recent years in the UK, enabling GPs to make assessments of cancer risk based on presenting symptoms; 33 , 34 they have been incorporated into clinical systems in primary care with mixed results.

Beyond these symptom-based models, a number of lung cancer risk models have been developed based on validated epidemiological criteria—for example, the Liverpool Lung Project (LLP) risk model 35 ( www.MyLungRisk.org ), which was subsequently used in the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial. 36 The LLP v2 risk model has also been used in the Liverpool Healthy Lung project, 37 which has accommodated the risk model within primary care practice and produced risk assessments that are useful in clinical decision making is now running into its third year. The Manchester lung cancer pilot study 38 has used the PLCO 2012 risk prediction model 39 and the recent Yorkshire Lung cancer screening trial 40 is using both the LLP v2 and the PLCO 2012 risk models. Models such as these provide a systematic way of assessing lung cancer risk, taking into account a range of factors, including smoking duration, previous respiratory disease, family history of lung cancer, age, previous history of malignancy and asbestos exposure.

Risk stratification in primary care is clearly a key priority. We need to look at instruments such as the LLP model and identify ways that lung cancer risk stratification can be made easy and convenient in primary care. At present, it is not possible to recommend a specific risk assessment tool for use in primary care; current ongoing research in primary care is externally validating existing tools and will compare their efficacy. 41 Acceptability and feasibility also need to be examined; complex algorithms that place extra burden on practitioners are unlikely to succeed. However, we do need to ensure that the basic risk prediction parameters are correctly documented in primary care, so they can be utilised in any future national lung cancer screening programme approved by the UKNSC. We also need a better understanding of ways to maximise benefits of these models—while minimising potential harms such as over-medicalisation, anxiety and false reassurance. 42 Machine learning or neuro-linguistic programming, whereby data from multiple practice-based and external sources might be examined to develop risk estimates, are also likely to play a significant role in the future. 43

Diagnostic pathways

Early diagnosis lung cancer clinics based on multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) are an ideal option for expediting diagnosis—ideally with an urgent (2-week wait) referral; 44 there is good evidence that these specialist MDT clinics are associated with improved outcomes. Another important consideration is involving the whole primary care team and including other practitioners such as pharmacists who see a lot of patients with, for example, repeat purchases of cough medicine. There has been a push to change referral practices in some parts of the UK—for example, to lower the threshold that PCPs refer for chest X-ray 45 and to encourage practitioners to repeat the investigation after a few months if symptoms persist; critically a normal chest X-ray does not exclude diagnosis of lung cancer. One highly successful programme in Leeds included the option for people to self-refer for chest X-rays in walk-in clinics 19 —a crucial element was the engagement of primary care in the design and implementation of the programme.

Diagnostic pathways have been closely examined and tested over recent years, an example being CRUK’s ACE programme (accelerate, coordinate and evaluate) initiated in June 2014 in England and Wales. 23 Patients often have complex pathways that can lead to delays; important initiatives in the ACE programme and elsewhere include risk-stratified computed tomographic (CT) screening criteria for ‘straight to CT’ referrals following normal chest X-rays and a focus on diagnostic paths for patients with vague symptoms.

Work needs to continue on diagnostic pathways that might expedite lung cancer diagnosis. It is important, for example, that we get more evidence on the impact or potential impact of direct access to investigations such as spiral CT from primary care—at present, there is not sufficient evidence or resource to universally implement this strategy, and there is evidence that delays can occur in primary care (for example, through ordering too many chest X-rays. 46 Nevertheless, GPs in the UK often indicate that direct access to investigations would help streamline diagnosis. 7

Lung cancer screening

A major challenge for primary care is the lack of symptoms in very early stage lung cancer, highlighting the importance of examining the potential of screening. The US National Lung Cancer Screening Trial, which used low-dose CT scanning in high-risk patients, showed a 20% reduction in lung cancer-specific mortality and almost a 7% reduction in all-cause mortality—and the US Preventive Task Force on Lung cancer Screening recommended that lung cancer screening should be implemented in high-risk populations. 47 , 48 Accordingly, Medicare agreed to pay for lung cancer screening within certain criteria—however, the current uptake in the US is only ~2% of high-risk individuals.

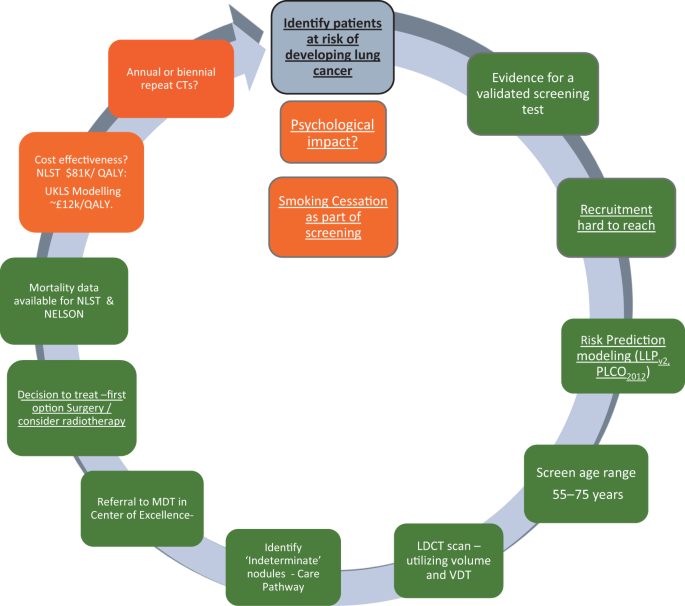

The recent report on the NELSON trial at the World Lung Cancer Conference, Toronto 49 has demonstrated an encouragingly low rate of false positives and a mortality benefit of 26% in men and between 39% and 61% in women—depending on the number of years of follow-up (i.e. 8–10 years). These results provide further impetus for the introduction of spiral CT scanning for individuals at high risk of cancer in the UK. Figure 2 illustrates the process for identifying an appropriate screening population, recruiting them and implementing screening—in many ways more complex than existing cancer screening programmes where recruitment is based principally on age and gender.

Levels of evidence for the implementation of lung cancer screening in Europe. The colour codes refer to the current status March 2019; traffic lights: green—ready, amber—borderline evidence. Underlined text indicates particular relevance for primary care 53

If we are, indeed, on the cusp of a new screening programme, there are important implications for primary care; the key issue in lung cancer screening is identifying the right patients to invite. This is a task that would involve primary care which currently lacks the systems and the processes to undertake the kind of population- based lung cancer risk assessment required. It is important, therefore, that we plan for an era where high-risk patients are screened for lung cancer (implemented, ideally, in tandem with smoking cessation programmes). We should be refining current strategies to risk stratify patients in primary care in preparation for this new era. 50 , 51 Screening alone, however, is not the total answer and a high level of awareness in both the public and the primary care community will remain vital elements in what needs to be a multi-pronged approach. 52

Conclusions and recommendations

Mortality rates for lung cancer remain stubbornly high; if we are to improve lung cancer outcomes, it is important that early diagnosis and screening efforts achieve their maximum potential. We need to:

identify ways of raising awareness of symptoms potentially associated with lung cancer in ways that encourage people at higher risk to come forward—this will require refinement of the messages delivered in awareness-raising strategies

counter the nihilistic beliefs often associated with lung cancer—early diagnosis CAN lead to improved outcomes

continually strive to improve the primary care response to patients with symptoms of lung cancer, supported by better diagnostic pathways and risk-based decision support

identify ‘fail-safe’ mechanisms by which patients advised to ‘watch and wait’ are not lost to follow-up; it is vital that patients understand these safety netting and follow-up advice

ensure that the basic risk prediction parameters are correctly documented in primary care, so they can be utilised in any future national lung cancer screening programme approved by the UKNSC

refine methods to implement lung cancer risk assessment model approaches; this is key to improving diagnosis of early lung cancer—and we should aim for risk estimates that can be readily incorporated into the various kinds of practice software used in primary care practices

continue to improve diagnostic pathways; at present, many different models are being evaluated, including those which give primary care more direct access to investigations such as spiral CT. The key task will be implementation and appropriate support once the best models are determined

fully engage primary care with the likely implementation of spiral CT lung cancer screening in the next few years—this will require the best possible risk-stratification approaches to ensure screening is directed at those who stand to benefit the most from it. It is vital that primary care rises to this challenge

Primary care needs to play a central role in efforts to diagnose lung cancer earlier, if there is to be an improvement in lung cancer outcomes in the years ahead. Research over the past decade gives us a much clearer idea of what needs to be done in refining primary care-based strategies; with adequate commitment and resources primary care will, in conjunction with other health care sectors, help reduce the burden from this disease.

Ferkol, T. & Schraufnagel, D. The global burden of respiratory disease. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 11 , 404–406 (2014).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Torre, L. A., Lindsey, A., Rebecca, L., Siegel, R. L. & Jemal, A. “Lung cancer statistics.” Lung cancer and personalized medicine. Adv. Exp. Med Biol. 893 , 1–19 (2016).

Coleman, M. P., Forman, D., Bryant, H., Butler, J. & Rachet, B. Cancer survival in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden, and the UK, 1995–2007 (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): an analysis of population-based cancer registry data. Lancet 377 , 127–138 (2011).

Tørring, M. L., Frydenberg, M., Hansen, R. P., Olesen, F. & Vedsted, P. Evidence of increasing mortality with longer diagnostic intervals for five common cancers: a cohort study in primary care. Eur. J. Cancer 49 , 2187–2198 (2013).

Walters, S. et al. Lung cancer survival and stage at diagnosis in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK: a population-based study, 2004–2007. Thorax 68 , 551–564 (2013).

Royal College of Physicians. National Lung Cancer Audit Annual report 2017. Available via www.nlcaudit.co.uk

Wagland, R. et al. Facilitating early diagnosis of lung cancer amongst primary care patients: the views of GPs. Eur. J. Cancer Care https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12704 (2017).

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Walter, F. M. et al. Symptoms and other factors associated with time to diagnosis and stage of lung cancer: a prospective cohort study. Br. J. Cancer 112 (suppl 1), S6–S13 (2015).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Forman, D. et al. Time for a European initiative for research to prevent cancer: a manifesto for Cancer Prevention Europe (CPE). J. Cancer Policy 17, 15–23 (2018).

Article Google Scholar

Smith, S. S. et al. Comparative effectiveness of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in primary care clinics. Arch. Intern. Med. 14 (169), 2148–2155 (2009).

Brown, J., Beard, E., Kotz, D., Michie, S. & West, R. Real‐world effectiveness of e‐cigarettes when used to aid smoking cessation: a cross‐sectional population study. Addiction 109 , 1531–1540 (2014).

Hansen, R. P., Vedsted, P., Sokolowski, I., Søndergaard, J. & Olesen, F. Time intervals from first symptom to treatment of cancer: a cohort study of 2,212 newly diagnosed cancer patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 11 , 284 (2011).

Niksic, M. et al. Cancer symptom awareness and barriers to symptomatic presentation in England—are we clear on cancer? Br. J. Cancer 28 (113), 533–542 (2015).

Biswas, M., Ades, A. E. & Hamilton, W. Symptom lead times in lung and colorectal cancers: what are the benefits of symptom based approaches to early diagnosis? Br. J. Cancer 112 , 271–277 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

O’Dowd, E. L. et al. What characteristics of primary care and patients are associated with early death in patients with lung cancer in the UK? Thorax 70 , 161–168 (2015).

Peake, M. D. Be Clear on Cancer: regional and national lung cancer awareness campaigns 2011 to 2014, Final evaluation results. National Cancer Registration and Analysis Service, Public Health England, February 2018. Available via: http://www.ncin.org.uk/cancer_type_and_topic_specific_work/topic_specific_work/be_clear_on_cancer/

Calanzani, N., Weller, D. & Campbell, C. Development of a Methodological Approach to Evaluate the Detect Cancer Early Programme in Scotland Cancer Research UK Early Diagnosis Conference. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/sites/default/files/edrc17_poster-42_nataliacalanzani_monteiro_detect_cancer_early_programme_in_scotland.pdf

Ironmonger, L. et al. An evaluation of the impact of large-scale interventions to raise public awareness of a lung cancer symptom. Br. J. Cancer 112 , 207 (2015).

Kennedy, M. P. T. et al. Lung cancer stage-shift following a symptom awareness campaign. Thorax 73 , 1128–1136 (2018).

Athey, V. L., Suckling, R. J., Tod, A. M., Walters, S. J. & Rogers, T. K. Early diagnosis of lung cancer: evaluation of a community-based social marketing intervention. Thorax 67 , 412–417 (2012).

Hamilton, W., Peters, T. J., Round, A. & Sharp, D. What are the clinical features of lung cancer before the diagnosis is made? A population based case-control study. Thorax 60 , 1059–1065 (2005).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

NICE. Suspected Cancer: Recognition and Referral NICE Guideline [NG12] , National Centre for Health and Care Excellence, London (2015).

Fuller, E., Fitzgerald, K. & Hiom, S. Accelerate, Coordinate, Evaluate Programme: a new approach to cancer diagnosis. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 66 , 176–177 (2016).

Lyratzopoulos, G., Neal, R. D., Barbiere, J. M., Rubin, G. P. & Abel, G. A. Variation in number of general practioner consultations before hospital referral for cancer: findings from the 2010 National Cancer Patient Experience Survey in England. Lancet Oncol. 13 , 353–365 (2012).

Mitchell, E. D., Rubin, G. & Macleod, U. Understanding diagnosis of lung cancer in primary care: qualitative synthesis of significant event audit reports. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 63 , e37–e46 (2013).

Evans, J. et al. GPs’ understanding and practice of safety netting for potential cancer presentations: a qualitative study in primary care. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 68 , e505–e511 (2018).

Corner, J., Hopkinson, J., Fitzsimmons, D., Barclay, S. & Muers, M. Is late diagnosis of lung cancer inevitable? Interview study of patients’ recollections of symptoms before diagnosis. Thorax 60 , 314–319 (2005).

Forbes, L. J. et al. Differences in cancer awareness and beliefs between Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and the UK (the International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership): do they contribute to differences in cancer survival? Br. J. Cancer 108 , 292–300 (2013).

Rubin, G. et al. The expanding role of primary care in cancer control. Lancet Oncol. 16 , 1231–1272 (2015).

Jones, G. S. & Baldwin, D. R. Recent advances in the management of lung cancer. Clin. Med. 18 (suppl 2), s41–s46 (2018).

Wagland, R. et al. Promoting help-seeking in response to symptoms amongst primary care patients at high risk of lung cancer: a mixed method study. PLoS ONE 11 , e0165677 (2016).

Ten Haaf, K., De Koning, H. & Field, J. Selecting the risk cut off for the LLP Model. J. Thorac. Oncol. 12 , S2174 (2017).

Hamilton, W. et al. Evaluation of risk assessment tools for suspected cancer in general practice: a cohort study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 63 , e30–e36 (2013).

Hippisley-Cox, J. & Coupland, C. Identifying patients with suspected lung cancer in primary care: derivation and validation of an algorithm. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 61 , e715–e723 (2011).

Cassidy, A. et al. The LLP risk model: an individual risk prediction model for lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 98 , 270–276 (2008).

Field, J. K. et al. The UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial: a pilot randomised controlled trial of low-dose computed tomography screening for the early detection of lung cancer. Health Technol. Assess. 20 , 1–146 (2016).

Field, J. K. et al. Abstract 4220: Liverpool Healthy Lung Project: a primary care initiative to identify hard to reach individuals with a high risk of developing lung cancer. Cancer Res . https://doi.org/10.1158/1538-7445.AM2017-4220 (2017).

Crosbie, P. A. et al. Implementing lung cancer screening: baseline results from a community-based ‘Lung Health Check’ pilot in deprived areas of Manchester. Thorax 0 , 1–5 (2018).

Google Scholar

Tammemagi, C. M. et al. Lung cancer risk prediction: prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancer screening trial models and validation. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 103 , 1058–1068 (2011).

ISRCTN Registry. The Yorkshire Lung Screening Trial ISRCTN42704678. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/ISRCTN42704678

Schmidt-Hansen, M., Berendse, S., Hamilton, W. & Baldwin, D. R. Lung cancer in symptomatic patients presenting in primary care: a systematic review of risk prediction tools. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 67 , e396–e404 (2017).

Usher-Smith, J., Emery, J., Hamilton, W., Griffin, S. J. & Walter, F. M. Risk prediction tools for cancer in primary care. Br. J. Cancer 113 , 1645 (2015).

Goldstein, B. A., Navar, A. M., Pencina, M. J. & Ioannidis, J. Opportunities and challenges in developing risk prediction models with electronic health records data: a systematic review. J. Am. Med. Inf. Assoc. 24 , 198–208 (2017).

Aldik, G., Yarham, E., Forshall, T., Foster, S. & Barnes, S. J. Improving the diagnostic pathway for patients with suspected lung cancer: analysis of the impact of a diagnostic MDT. Lung Cancer 115 , S12–S13 (2018).

Neal, R. D. et al. Immediate chest X-ray for patients at risk of lung cancer presenting in primary care: randomised controlled feasibility trial. Br. J. Cancer 116 , 293 (2017).

Guldbrandt, L. M., Rasmussen, T. R., Rasmussen, F. & Vedsted, P. Implementing direct access to low-dose computed tomography in general practice—method, adaption and outcome. PLoS ONE 9 , e112162 (2014).

Moyer, V. A. Screening for lung cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 160 , 330–338 (2014).

PubMed Google Scholar

Cheung, L. C., Katki, H. A., Chaturvedi, A. K., Jemal, A. & Berg, C. D. Preventing lung cancer mortality by computed tomography screening: the effect of risk-based versus US Preventive Services Task Force eligibility criteria, 2005–2015. Ann. Intern. Med. 168 , 229–232 (2018).

IASLC. NELSON Study Shows CT Screening for Nodule Volume Management Reduces Lung Cancer Mortality by 26 Percent in Men. 9th World Congress on Lung Cancer . https://wclc2018.iaslc.org/media/2018%20WCLC%20Press%20Program%20Press%20Release%20De%20Koning%209.25%20FINAL%20.pdf

Field, J. K., Duffy, S. W. & Baldwin, D. R. Patient selection for future lung cancer computed tomography screening programmes: lessons learnt post National Lung Cancer Screening Trial. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 7 (suppl 2), S114–S116 (2018).

Yousaf-Khan, U. et al. Risk stratification based on screening history: the NELSON lung cancer screening study. Thorax 72 , 819–824 (2017).

Peake, M. D., Navani, N. & Baldwin, D. The continuum of screening and early detection, awareness and faster diagnosis of lung cancer. Thorax 73 , 1097–1098 (2018).

Field, J. K., Devaraj, A., Duffy, S. W. & Baldwin, D. R. CT screening for lung cancer: is the evidence strong enough? Lung Cancer 91 , 29–35 (2016).

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

D. P. Weller

Centre for Cancer Outcomes, University College London Hospitals Cancer Collaborative, University of Leicester, NCRAS/PHE, London, UK

M. D. Peake

Roy Castle Lung Cancer Research Programme, Department of Molecular and Clinical Cancer Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

J. K. Field

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.P.W. led on literature searching and draft manuscript preparation. J.K.F. and M.D.P. provided input to early drafts and added text in their areas of expertise.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to D. P. Weller .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Weller, D.P., Peake, M.D. & Field, J.K. Presentation of lung cancer in primary care. npj Prim. Care Respir. Med. 29 , 21 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-019-0133-y

Download citation

Received : 22 November 2018

Accepted : 12 April 2019

Published : 22 May 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41533-019-0133-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Anti-proliferative activity, molecular genetics, docking analysis, and computational calculations of uracil cellulosic aldehyde derivatives.

- Asmaa M. Fahim

- Sawsan Dacrory

- Ghada H. Elsayed

Scientific Reports (2023)

Lung cancer and Covid-19: lessons learnt from the pandemic and where do we go from here?

- Susanne Sarah Maxwell

- David Weller

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine (2022)

LncRNA CBR3-AS1 potentiates Wnt/β-catenin signaling to regulate lung adenocarcinoma cells proliferation, migration and invasion

Cancer Cell International (2021)

Is the combination of bilateral pulmonary nodules and mosaic attenuation on chest CT specific for DIPNECH?

- Bilal F. Samhouri

- Chi Wan Koo

Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases (2021)

Evaluation of a national lung cancer symptom awareness campaign in Wales

- Grace McCutchan

- Stephanie Smits

British Journal of Cancer (2020)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

What Is Lung Cancer?

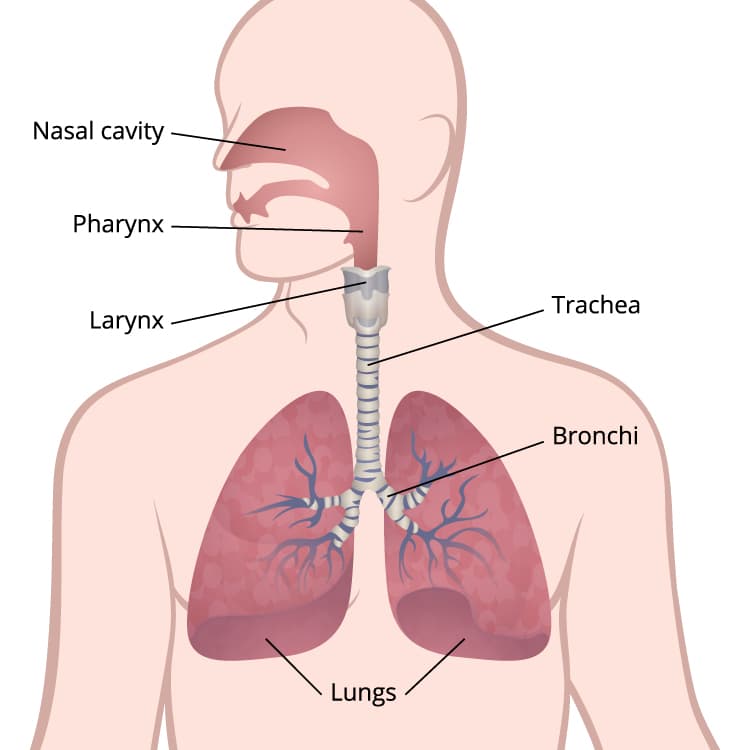

This illustration of the respiratory system shows the lungs, bronchi, trachea, larynx, pharynx, and nasal cavity.

Cancer is a disease in which cells in the body grow out of control. When cancer starts in the lungs, it is called lung cancer.

Lung cancer begins in the lungs and may spread to lymph nodes or other organs in the body, such as the brain. Cancer from other organs also may spread to the lungs. When cancer cells spread from one organ to another, they are called metastases.

Lung cancers usually are grouped into two main types called small cell and non-small cell (non-small cell includes adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma). These types of lung cancer grow differently and are treated differently. Non-small cell lung cancer is more common than small cell lung cancer. For more information, visit the National Cancer Institute’s Lung Cancer.

Stay Informed

Exit notification / disclaimer policy.

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Airway diseases pp 1–19 Cite as

Clinical Presentation of Lung Cancer

- Pınar Akın Kabalak 5 &

- Ülkü Yılmaz 5

- First Online: 21 September 2023

690 Accesses

Among lung cancer patients, 5–15% are asymptomatic despite experiencing serious morbidity and mortality [1]. Symptoms vary as a result of cell type, localization, diameter, stage, concomitant pulmonary disease, and concomitant paraneoplastic syndromes. The prognosis for patients who are symptomatic at the time of diagnosis has been shown to be worse than that for asymptomatic patients [2]. Therefore, to increase survival, it may be possible to reduce the cancer-related mortality at an early stage as a result of screening individuals in the high-risk group using low-dose tomography [3].

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Chute CG, Greenberg ER, Baron J, et al. Presenting conditions of 1539 population-based lung cancer patients by cell type and stage in New Hampshire and Vermont. Cancer. 1985;56(8):2107–11.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Santos-Martínez MJ, Curull V, Blanco ML, et al. Lung cancer at a university hospital: epidemiological and histological characteristics of a recent and a historical series. Arch Bronconeumol. 2005;41(6):307–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1579-2129(06)60230-9 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Field JK, Oudkerk M, Pedersen JH, et al. Prospects for population screening and diagnosis of lung cancer. Lancet. 2013;382(9893):732–41.

Ost DE, Yeung SC, Tanoue LT, et al. Clinical and organizational factors in the initial evaluation of patients with lung cancer. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e121S–41S.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hyde L, Hayde CI. Clinical manifestations of lung cancer. Chest. 1974;65:299. PMID: 4813837.

Beckles MA, Spiro SG, Gen Colice GL, et al. Initial evaluation of the patient with lung cancer: symptoms, signs, laboratory tests, and paraneoplastic syndromes. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):97S–104S.

Kvale PA, Simoff M, Prakash UBS, et al. Lung cancer palliative care. Chest. 2003;123(1 Suppl):284S–311S.

Athey VL, Walters SJ, Rogers TK. Symptoms at lung cancer diagnosis are associated with major differences in prognosis. Thorax. 2018;73(12):1177. Epub 2018 Apr 17

Chute CG, Greenberg ER, Baron J, et al. Presenting conditions of 1539 population-based lung cancer patients by cell type and stage in New Hampshire and Vermont. Cancer. 1985;56(8):2107.

Colice GL. Detecting lung cancer as a cause of hemoptysis in patients with a normal chest radiograph: bronchoscopy vs CT. Chest. 1997;111:877.

Abraham PJ, Capobianco DJ, Cheshire WP. Facial pain as the presenting symptom of lung carcinoma with Normal chest radiograph. Headache. 2003;43(5):499–504.

Farber SM, Mandel W, Spain DM. Diagnosis and treatment of tumors of the chest. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1960.

Google Scholar

Kuo CW, Chen YM, Chao JY, et al. Non-small cell lung cancer in very young and very old patients. Chest. 2000;117:354–7.

Buccheri G, Ferrigno D. Lung cancer: clinical presentation and specialist referral time. Eur Respir J. 2004;24:898–904.

Johnston WW. The malignant pleural effusion. A review of cytopathologic diagnoses of 584 specimens from 472 consecutive patients. Cancer. 1985;56(4):905–9.

Heffner JE, Klein JS. Recent advances in the diagnosis and management of malignant pleural effusions. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83(2):235–50.

Decker DA, Dines DE, Payne WS, et al. The significance of a cytologically negative pleural effusion in bronchogenic carcinoma. Chest. 1978;74(6):640.

Imazio M, Colopi M, De Ferrari GM. Pericardial diseases in patients with cancer: contemporary prevalence, management and outcomes. Heart. 2020;106(8):569–74.

Friedman T, Quencer KB, Kishore SA, et al. Malignant venous obstruction: superior vena cava syndrome and beyond. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2017;34(4):398–408.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gundepalli SG, Tadi P. Cancer, lung pancoast (superior sulcus tumour). Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Stankey RM, Roshe J, Sogocio RM. Carcinoma of the lung and dysphagia. Dis Chest. 1969;55(1):13–7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.55.1.13 .

Marmor S, Cohen S, Fujioka N, et al. Dysphagia prevalence and associated survival differences in older patients with lung cancer: a SEER-Medicare Population-Based Study. J Geriatr Oncol 2020;S1879-4068(19)30426-6.

Coleman RE. Skeletal complications of malignancy. Cancer. 1997;80:1588–94.

Wang CY, Zhang XY. (99m)Tc-MDP wholebody bone imaging in evaluation of the characteristics of bone metastasis of primary lung cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi. 2010;32(5):382–6.

PubMed Google Scholar

Husaini HA, Price PW, Clemons M, et al. Prevention and management of bone metastases in lung cancer: a review. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:251–9.

Lassman AB, DeAngelis LM. Brain metastases. Neurol Clin. 2003;21(1):1.

Delattre JY, Krol G, Thaler HT, et al. Distribution of brain metastases. Arch Neurol. 1988;45(7):741.

Clouston PD, DeAngelis LM, Posner JB. The spectrum of neurological disease in patients with systemic cancer. Ann Neurol. 1992;31(3):268–73.

Nutt SH, Patchell RA. Intracranial haemorrhage associated with primary and secondary tumours. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1992;3(3):591.

Grossman SA, Krabak MJ. Leptomeningeal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Rev. 1999;25:103–19.

Morris PG, Reiner AS, Szenberg OR, et al. Leptomeningeal metastasis from non-small cell lung cancer survival and the impact of whole brain radiotherapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:382–5.

Omuro AM, Lallana EC, Bilsky MH, et al. Ventriculoperitoneal shunt in patients with leptomeningeal metastasis. Neurology. 2005;64:1625–7.

Cheng H, Perez-Soler R. Leptomeningeal metastases in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19(1):e43–55.

Lam KY, Lo CY. Metastatic tumours of the adrenal glands: a 30-year experience in a teaching hospital. Clin Endocrinol. 2002;56:95–101.

Article Google Scholar

Raz DJ, Lanuti M, Gaissert HC, et al. Outcomes of patients with isolated adrenal metastasis from non-small cell lung carcinoma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92(5):1788–92.

Kagohashi K, Satoh H, Ishikawa H, et al. Liver metastasis at the time of initial diagnosis of lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2003;20(1):25–8.

https://www.cancer.ca/en/cancer-information/cancer-type/metastatic-cancer/liver-metastases/?region=on

Khaja M, Mundt D, Dudekula RA, et al. Lung cancer presenting as skin metastasis of the back and hand: a case series and literature review. Case Rep Oncol. 2019;12:480–7.

Joll CA. Metastatic tumours of bone. Br J Surg. 1923;11:38–72.

Afshar A, Farhadnia P, Khalkhali H. Metastases to the hand and wrist: an analysis of 221 cases. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(5):923–32.e17.

Flynn CJ, Danjoux C, Wong J, et al. Two cases of acrometastasis to the hands and review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2008;15:51–8.

Mavrogenis AF, Mimidis G, Kokkalis ZT, et al. Acrometastases. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24:279–83.

Unsal M, Kutlar G, Sullu Y, et al. Tonsillar metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Respir J. 2016;10(6):681–3.

Liyang Z, Yuewu L, Xiaoyi L, et al. Metastases to the thyroid gland. A report of 32 cases in PUMCH. Medicine. 2017;96(36):e7927.

Niu FY, Zhou Q, Yang JJ, et al. Distribution and prognosis of uncommon metastases from non-small cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2016;16:149.

Kızılgöz D, Kabalak PA, Cengiz Tİ, et al. Splenic metastasis in lung cancer. Turk Klin Arch Lung. 2017;18(2):47–51.

Efthymiou C, Spyratos D, Kontakiotis T. Endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes in lung cancer. Hormones. 2018;17:351–8.

Anwar A, Jafri F, Ashraf S, et al. Paraneoplastic syndromes in lung cancer and their management. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(15):359.

Rossato M, Zabeo E, Burei M, et al. Lung cancer and paraneoplastic neurologic syndromes. Case report and review of the literature. Clin Lung Cancer. 2013;14(3):301–9.

Pelosof LC, Gerber DE. Paraneoplastic syndromes: an approach to diagnosis and treatment. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(9):838–54.

Thomas L, Kwok Y, Edelman MJ. Management of paraneoplastic syndromes in lung cancer. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2004;5(1):51–62.

Makiyama Y, Kikuchi T, Otani A, et al. Clinical and immunological characterization of paraneoplastic retinopathy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54(8):5424–31.

Stoyanov GS, Dzhenkov DL, Tzaneva M. Thrombophlebitis Migrans (Trousseau syndrome) in pancreatic adenocarcinoma: an autopsy report. Cureus. 2019;11(8):e5528.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dalakas MC, Hohlfeld R. Polymyositis and dermatomyositis. Lancet. 2003;362(9388):971–82.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Pulmonology, Health Sciences University Atatürk Chest and Chest Surgery Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

Pınar Akın Kabalak & Ülkü Yılmaz

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Eskişehir Osmangazi University, Eskisehir, Türkiye

Cemal Cingi

Department of Pulmonology, Celal Bayar University, Manisa, Türkiye

Arzu Yorgancıoğlu

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Kırıkkale University, Kırıkkale, Türkiye

Nuray Bayar Muluk

Federal University of Bahia School of Medicine and ProAR Foundation, Salvador - Bahia, Brazil

Alvaro A. Cruz

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Kabalak, P.A., Yılmaz, Ü. (2023). Clinical Presentation of Lung Cancer. In: Cingi, C., Yorgancıoğlu, A., Bayar Muluk, N., Cruz, A.A. (eds) Airway diseases. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22483-6_60-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-22483-6_60-1

Received : 11 November 2022

Accepted : 11 November 2022

Published : 21 September 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-22482-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-22483-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Reference Module Medicine

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Lung Cancer: Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

Affiliation.

- 1 US Naval Hospital Sigonella Italy, PSC 836 Box 2670, FPO, AE 09636.

- PMID: 29313654

In the absence of screening, most patients with lung cancer are not diagnosed until later stages, when the prognosis is poor. The most common symptoms are cough and dyspnea, but the most specific symptom is hemoptysis. Digital clubbing, though rare, is highly predictive of lung cancer. Symptoms can be caused by the local tumor, intrathoracic spread, distant metastases, or paraneoplastic syndromes. Clinicians should suspect lung cancer in symptomatic patients with risk factors. The initial study should be chest x-ray, but if results are negative and suspicion remains, the clinician should obtain a computed tomography scan with contrast. The diagnostic evaluation for suspected lung cancer includes tissue diagnosis, staging, and determination of functional capacity, which are completed simultaneously. Tissue samples should be obtained using the least invasive method possible. Management is based on the individual tumor histology, molecular testing results, staging, and performance status. The management plan is determined by a multidisciplinary team consisting of a pulmonology subspecialist, medical oncology subspecialist, radiation oncology subspecialist, and thoracic surgeon. The family physician should remain involved with the patient to ensure that patient priorities are supported and, if necessary, to arrange for end-of-life care.

Written permission from the American Academy of Family Physicians is required for reproduction of this material in whole or in part in any form or medium.

Publication types

- Adenocarcinoma / complications

- Adenocarcinoma / diagnostic imaging*

- Adenocarcinoma / pathology

- Adenocarcinoma / physiopathology

- Carcinoma, Large Cell / complications

- Carcinoma, Large Cell / diagnostic imaging*

- Carcinoma, Large Cell / pathology

- Carcinoma, Large Cell / physiopathology

- Carcinoma, Squamous Cell / complications

- Carcinoma, Squamous Cell / diagnostic imaging*

- Carcinoma, Squamous Cell / pathology

- Carcinoma, Squamous Cell / physiopathology

- Cough / etiology

- Dyspnea / etiology

- Hemoptysis / etiology

- Lung Neoplasms / complications

- Lung Neoplasms / diagnostic imaging*

- Lung Neoplasms / pathology

- Lung Neoplasms / physiopathology

- Neoplasm Staging

- Paraneoplastic Syndromes / etiology

- Respiratory Function Tests

- Small Cell Lung Carcinoma / complications

- Small Cell Lung Carcinoma / diagnostic imaging*

- Small Cell Lung Carcinoma / pathology

- Small Cell Lung Carcinoma / physiopathology

Lung Cancer Clinical Presentation

There are no specific signs and symptoms for lung cancer, and the clinical presentation of lung cancer may vary from patient to patient. At the time of diagnosis, the vast majority of patients with lung cancer have advanced disease. The frequent absence of symptoms until locally advanced or metastatic disease is present reveals the aggressive nature of lung cancer and also highlights the urgent need to expand efforts to routinely screen patients at high risk. Research indicates that many cases of lung cancer are often detected incidentally via chest imaging. In about 7% to 10% of cases, lung cancer is detected and diagnosed in asymptomatic patients when a chest radiograph is performed to diagnose other conditions. At initial diagnosis, 20% of patients have localized disease, 25% of patients have regional metastasis, and 55% of patients have distant disease spread. In some cases, high-risk patients may be diagnosed while asymptomatic through screening with low-dose computed tomography. About three-fourths of nonscreened patients with lung cancer present with one or more symptoms at the time of diagnosis. The most common symptoms include cough, dyspnea, and hemoptysis. Although the clinical presentation of lung cancer is not specific to the classification or histology of the cancer, certain obstacles may be more likely with different types. One study noted that the most common symptoms at presentation were cough (55%), dyspnea (45%), pain (38%), and weight loss (36%), as well as hemoptysis. The new onset of cough in a smoker or former smoker should raise suspicion for lung cancer. The clinical manifestations of lung cancer may be due to intrathoracic effects of the tumor (e.g., cough, hemoptysis, pleural disease), extrathoracic metastases (most commonly liver, bone, brain), or paraneoplastic phenomena (e.g., hypercalcemia, Cushing syndrome, hypercoagulability disorders, various neurologic syndromes). Squamous cell and small cell cancers usually cause a cough early due to the involvement of the central airways. Hemoptysis is a significant symptom in anyone with a history of smoking. Although bronchitis is the most frequent cause of hemoptysis, 20% to 50% of patients with underlying lung cancer present with hemoptysis. While rare, patients with lung cancer may present with shoulder pain, Horner syndrome, and hand-muscle atrophy, and this group of symptoms is referred to as Pancoast syndrome . Pancoast syndrome is most frequently due to lung cancers arising in the superior sulcus. Metastasis from lung cancer to bone is generally symptomatic, and pain in the back, chest, or extremity and elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase are frequently present in patients who have bone metastasis. Moreover, levels of serum calcium may be elevated due to extensive bone disease, and an estimated 20% of patients with non–small cell lung cancer have bone metastases at the time of diagnosis. The American Cancer Society (ACS) indicates that in addition to the signs and symptoms mentioned above, patients with lung cancer may also experience hoarseness, new-onset wheezing, and fatigue. The ACS also encourages individuals to seek medical care early if they are experiencing any symptoms, since early detection and treatment may improve overall clinical outcomes in some patients. The content contained in this article is for informational purposes only. The content is not intended to be a substitute for professional advice. Reliance on any information provided in this article is solely at your own risk.

Related Content

Contemporary developments in met-selective kinase inhibitors in advanced non–small-cell lung cancer.

- Advertising Contacts

- Editorial Staff

- Professional Organizations

- Submitting a Manuscript

- Privacy Policy

- Classifieds

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- NPJ Prim Care Respir Med

Presentation of lung cancer in primary care

D. p. weller.

1 Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK

M. D. Peake

2 Centre for Cancer Outcomes, University College London Hospitals Cancer Collaborative, University of Leicester, NCRAS/PHE, London, UK

J. K. Field

3 Roy Castle Lung Cancer Research Programme, Department of Molecular and Clinical Cancer Medicine, The University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

Survival from lung cancer has seen only modest improvements in recent decades. Poor outcomes are linked to late presentation, yet early diagnosis can be challenging as lung cancer symptoms are common and non-specific. In this paper, we examine how lung cancer presents in primary care and review roles for primary care in reducing the burden from this disease. Reducing rates of smoking remains, by far, the key strategy, but primary care practitioners (PCPs) should also be pro-active in raising awareness of symptoms, ensuring lung cancer risk data are collected accurately and encouraging reluctant patients to present. PCPs should engage in service re-design and identify more streamlined diagnostic pathways—and more readily incorporate decision support into their consulting, based on validated lung cancer risk models. Finally, PCPs should ensure they are central to recruitment in future lung cancer screening programmes—they are uniquely placed to ensure the right people are targeted for risk-based screening programmes. We are now in an era where treatments can make a real difference in early-stage lung tumours, and genuine progress is being made in this devastating illness—full engagement of primary care is vital in effecting these improvements in outcomes.

Introduction

Lung cancer poses a significant public health burden around the world; it is the most common cause of cancer mortality in the UK and it accounts for >20% of cancer deaths. 1 There is significant variation in survival rates around the world and this has been largely attributed to the stage at which the cancer is diagnosed. 2 The International Cancer Benchmarking Partnership has demonstrated that survival rates in the UK lag behind those of other countries, and late diagnosis is thought to be a major underlying factor. 3 , 4 Importantly, patients with early-stage disease have a much better prognosis; stage 1 non-small-cell lung cancer can have a 5-year survival rate as high as 75%. 5 Even within the UK, however, there is wide variation in lung cancer survival rates and in the proportion of patients diagnosed with early-stage disease. 6

In the UK, most cancers present symptomatically in primary care (most commonly to a general practitioner, or ‘GP’, the medical lead of a primary care team), and the diagnosis is made after a referral for either investigations or directly to secondary care. 7 Many of the symptoms of lung cancer are very common but non-specific in primary care practice: these include chest pain, cough and breathlessness; 8 hence, lung cancer poses a very significant diagnostic challenge—a primary care practitioner (PCP) working full time is likely to only diagnose 1 or 2 cases per year. Further, lung cancer often emerges on a background of chronic respiratory disease and symptoms of chronic cough—typically in patients who smoke. It can be very difficult to identify changes in these chronic symptoms that might indicate the development of a lung tumour.

Smoking remains the principal aetiological factor and smoking cessation is the key public health initiative to reduce mortality from this disease; 9 indeed, at almost any age smoking cessation can produce health benefits. Hence, public health campaigns to promote smoking cessation, supplemented by strategies in primary care based on nicotine replacement therapies should be encouraged. 10 The role of e-cigarettes is not yet fully understood, 11 although any strategy that reduces exposure to tobacco smoke has a potential for producing significant benefits.

How do patients respond to lung cancer symptoms?

There is a significant body of research around patient response to symptoms that might potentially indicate lung cancer. Because symptoms often present within the context of chronic respiratory symptomatology, changes associated with the development of a tumour may go un-noticed or be dismissed. 8 It is known that patients often delay their help seeking through a range of psychological mechanisms including denial and nihilism—hence, there can often be significant delays before patients present to primary care. 12 , 13

There is evidence for variation in the timeliness of presentation of lung cancer in between countries; people with lung cancer often have symptoms for a considerable period of time before they present to primary care and this is a major source of delay in the diagnostic process with potential adverse impact on survival; 14 , 15 this patient interval does, however, vary between studies. It is important that PCPs understand some of the psychological mechanisms that either promote or inhibit early presentation among their patients.

Public awareness of lung cancer

Over the past few years, there have been campaigns run throughout the UK designed to make the public more aware of symptoms associated with lung cancer—for example the ‘Be clear on Cancer’ campaign run by Public Health England and ‘Diagnose Cancer Early’ in Scotland 16 , 17 (see Fig. Fig.1). 1 ). These campaigns have demonstrated an ability to diagnose additional cancers and effect modest increases in the proportion of patients having tumours diagnosed at stages where they are amenable to resection. 18 , 19

Posters used in the ‘Be Clear on Cancer’ campaign

Of course, lung cancer early detection programmes need to be focussed on the hard-to-reach population and those who will benefit most from involvement; there are often concerns expressed over burdening services with patients with insignificant symptoms 18 and an emerging consensus that all stakeholders should be closely engaged in the campaigns. Nevertheless, available evidence suggests that lung cancer could be diagnosed earlier through these public awareness campaigns, 19 particularly when associated with systems to help primary care physicians risk stratify their patients for lung cancer more effectively—indeed, further work to identify patients who might benefit from targeted interventions should be a priority.

Community-based social marketing interventions have a potential key role; 20 they can increase the likelihood of patients attending PCPs and increase primary care diagnostic activity (such as chest X-ray referrals)—as well as increases in lung cancer diagnostic rates. The level of suspicion at which PCPs consider a referral is a key factor in response to these campaigns—and there are concerns over ‘system overload’ through encouragement to present with symptoms. 13 Ideally, campaigns might preferentially target those at greater risk of lung cancer, such as people with significant smoking histories or occupational exposure.

Primary care response to lung cancer symptoms

In the UK, GPs will on average only diagnose one or two cases of lung cancer per year (if they are in full-time practice). 21 However, during that year, GPs will see hundreds of patients with common symptoms, such as cough, breathlessness and chest pain—hence, there are significant difficulties in identifying, diagnosing and referring these patients in a timely manner.