Essay on Peace

500 words essay peace.

Peace is the path we take for bringing growth and prosperity to society. If we do not have peace and harmony, achieving political strength, economic stability and cultural growth will be impossible. Moreover, before we transmit the notion of peace to others, it is vital for us to possess peace within. It is not a certain individual’s responsibility to maintain peace but everyone’s duty. Thus, an essay on peace will throw some light on the same topic.

Importance of Peace

History has been proof of the thousands of war which have taken place in all periods at different levels between nations. Thus, we learned that peace played an important role in ending these wars or even preventing some of them.

In fact, if you take a look at all religious scriptures and ceremonies, you will realize that all of them teach peace. They mostly advocate eliminating war and maintaining harmony. In other words, all of them hold out a sacred commitment to peace.

It is after the thousands of destructive wars that humans realized the importance of peace. Earth needs peace in order to survive. This applies to every angle including wars, pollution , natural disasters and more.

When peace and harmony are maintained, things will continue to run smoothly without any delay. Moreover, it can be a saviour for many who do not wish to engage in any disrupting activities or more.

In other words, while war destroys and disrupts, peace builds and strengthens as well as restores. Moreover, peace is personal which helps us achieve security and tranquillity and avoid anxiety and chaos to make our lives better.

How to Maintain Peace

There are many ways in which we can maintain peace at different levels. To begin with humankind, it is essential to maintain equality, security and justice to maintain the political order of any nation.

Further, we must promote the advancement of technology and science which will ultimately benefit all of humankind and maintain the welfare of people. In addition, introducing a global economic system will help eliminate divergence, mistrust and regional imbalance.

It is also essential to encourage ethics that promote ecological prosperity and incorporate solutions to resolve the environmental crisis. This will in turn share success and fulfil the responsibility of individuals to end historical prejudices.

Similarly, we must also adopt a mental and spiritual ideology that embodies a helpful attitude to spread harmony. We must also recognize diversity and integration for expressing emotion to enhance our friendship with everyone from different cultures.

Finally, it must be everyone’s noble mission to promote peace by expressing its contribution to the long-lasting well-being factor of everyone’s lives. Thus, we must all try our level best to maintain peace and harmony.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Conclusion of the Essay on Peace

To sum it up, peace is essential to control the evils which damage our society. It is obvious that we will keep facing crises on many levels but we can manage them better with the help of peace. Moreover, peace is vital for humankind to survive and strive for a better future.

FAQ of Essay on Peace

Question 1: What is the importance of peace?

Answer 1: Peace is the way that helps us prevent inequity and violence. It is no less than a golden ticket to enter a new and bright future for mankind. Moreover, everyone plays an essential role in this so that everybody can get a more equal and peaceful world.

Question 2: What exactly is peace?

Answer 2: Peace is a concept of societal friendship and harmony in which there is no hostility and violence. In social terms, we use it commonly to refer to a lack of conflict, such as war. Thus, it is freedom from fear of violence between individuals or groups.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

December 2, 2021

Peace Is More Than War’s Absence, and New Research Explains How to Build It

A new project measures ways to promote positive social relations among groups

By Peter T. Coleman , Allegra Chen-Carrel & Vincent Hans Michael Stueber

PeopleImages/Getty Images

Today, the misery of war is all too striking in places such as Syria, Yemen, Tigray, Myanmar and Ukraine. It can come as a surprise to learn that there are scores of sustainably peaceful societies around the world, ranging from indigenous people in the Xingu River Basin in Brazil to countries in the European Union. Learning from these societies, and identifying key drivers of harmony, is a vital process that can help promote world peace.

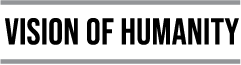

Unfortunately, our current ability to find these peaceful mechanisms is woefully inadequate. The Global Peace Index (GPI) and its complement the Positive Peace Index (PPI) rank 163 nations annually and are currently the leading measures of peacefulness. The GPI, launched in 2007 by the Institute for Economics and Peace (IEP), was designed to measure negative peace , or the absence of violence, destructive conflict, and war. But peace is more than not fighting. The PPI, launched in 2009, was supposed to recognize this and track positive peace , or the promotion of peacefulness through positive interactions like civility, cooperation and care.

Yet the PPI still has many serious drawbacks. To begin with, it continues to emphasize negative peace, despite its name. The components of the PPI were selected and are weighted based on existing national indicators that showed the “strongest correlation with the GPI,” suggesting they are in effect mostly an extension of the GPI. For example, the PPI currently includes measures of factors such as group grievances, dissemination of false information, hostility to foreigners, and bribes.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The index also lacks an empirical understanding of positive peace. The PPI report claims that it focuses on “positive aspects that create the conditions for a society to flourish.” However, there is little indication of how these aspects were derived (other than their relationships with the GPI). For example, access to the internet is currently a heavily weighted indicator in the PPI. But peace existed long before the internet, so is the number of people who can go online really a valid measure of harmony?

The PPI has a strong probusiness bias, too. Its 2021 report posits that positive peace “is a cross-cutting facilitator of progress, making it easier for businesses to sell.” A prior analysis of the PPI found that almost half the indicators were directly related to the idea of a “Peace Industry,” with less of a focus on factors found to be central to positive peace such as gender inclusiveness, equity and harmony between identity groups.

A big problem is that the index is limited to a top-down, national-level approach. The PPI’s reliance on national-level metrics masks critical differences in community-level peacefulness within nations, and these provide a much more nuanced picture of societal peace . Aggregating peace data at the national level, such as focusing on overall levels of inequality rather than on disparities along specific group divides, can hide negative repercussions of the status quo for minority communities.

To fix these deficiencies, we and our colleagues have been developing an alternative approach under the umbrella of the Sustaining Peace Project . Our effort has various components , and these can provide a way to solve the problems in the current indices. Here are some of the elements:

Evidence-based factors that measure positive and negative peace. The peace project began with a comprehensive review of the empirical studies on peaceful societies, which resulted in identifying 72 variables associated with sustaining peace. Next, we conducted an analysis of ethnographic and case study data comparing “peace systems,” or clusters of societies that maintain peace with one another, with nonpeace systems. This allowed us to identify and measure a set of eight core drivers of peace. These include the prevalence of an overarching social identity among neighboring groups and societies; their interconnections such as through trade or intermarriage; the degree to which they are interdependent upon one another in terms of ecological, economic or security concerns; the extent to which their norms and core values support peace or war; the role that rituals, symbols and ceremonies play in either uniting or dividing societies; the degree to which superordinate institutions exist that span neighboring communities; whether intergroup mechanisms for conflict management and resolution exist; and the presence of political leadership for peace versus war.

A core theory of sustaining peace . We have also worked with a broad group of peace, conflict and sustainability scholars to conceptualize how these many variables operate as a complex system by mapping their relationships in a causal loop diagram and then mathematically modeling their core dynamics This has allowed us to gain a comprehensive understanding of how different constellations of factors can combine to affect the probabilities of sustaining peace.

Bottom-up and top-down assessments . Currently, the Sustaining Peace Project is applying techniques such as natural language processing and machine learning to study markers of peace and conflict speech in the news media. Our preliminary research suggests that linguistic features may be able to distinguish between more and less peaceful societies. These methods offer the potential for new metrics that can be used for more granular analyses than national surveys.

We have also been working with local researchers from peaceful societies to conduct interviews and focus groups to better understand the in situ dynamics they believe contribute to sustaining peace in their communities. For example in Mauritius , a highly multiethnic society that is today one of the most peaceful nations in Africa, we learned of the particular importance of factors like formally addressing legacies of slavery and indentured servitude, taboos against proselytizing outsiders about one’s religion, and conscious efforts by journalists to avoid divisive and inflammatory language in their reporting.

Today, global indices drive funding and program decisions that impact countless lives, making it critical to accurately measure what contributes to socially just, safe and thriving societies. These indices are widely reported in news outlets around the globe, and heads of state often reference them for their own purposes. For example, in 2017 , Honduran President Juan Orlando Hernandez, though he and his country were mired in corruption allegations, referenced his country’s positive increase on the GPI by stating, “Receiving such high praise from an institute that once named this country the most violent in the world is extremely significant.” Although a 2019 report on funding for peace-related projects shows an encouraging shift towards supporting positive peace and building resilient societies, many of these projects are really more about preventing harm, such as grants for bolstering national security and enhancing the rule of law.

The Sustaining Peace Project, in contrast, includes metrics for both positive and negative peace, is enhanced by local community expertise, and is conceptually coherent and based on empirical findings. It encourages policy makers and researchers to refocus attention and resources on initiatives that actually promote harmony, social health and positive reciprocity between groups. It moves away from indices that rank entire countries and instead focuses on identifying factors that, through their interaction, bolster or reduce the likelihood of sustaining peace. It is a holistic perspective.

Tracking peacefulness across the globe is a highly challenging endeavor. But there is great potential in cooperation between peaceful communities, researchers and policy makers to produce better methods and metrics. Measuring peace is simply too important to get only half-right.

World Peace Essay: Prompts, How-to Guide, & 200+ Topics

Throughout history, people have dreamed of a world without violence, where harmony and justice reign. This dream of world peace has inspired poets, philosophers, and politicians for centuries. But is it possible to achieve peace globally? Writing a world peace essay will help you find the answer to this question and learn more about the topic.

In this article, our custom writing team will discuss how to write an essay on world peace quickly and effectively. To inspire you even more, we have prepared writing prompts and topics that can come in handy.

- ✍️ Writing Guide

- 🦄 Essay Prompts

- ✔️ World Peace Topics

- 🌎 Pacifism Topics

- ✌️ Catchy Essay Titles

- 🕊️ Research Topics on Peace

- 💡 War and Peace Topics

- ☮️ Peace Title Ideas

- 🌐 Peace Language Topics

🔗 References

✍️ how to achieve world peace essay writing guide.

Stuck with your essay about peace? Here is a step-by-step writing guide with many valuable tips to make your paper well-structured and compelling.

1. Research the Topic

The first step in writing your essay on peace is conducting research. You can look for relevant sources in your university library, encyclopedias, dictionaries, book catalogs, periodical databases, and Internet search engines. Besides, you can use your lecture notes and textbooks for additional information.

Among the variety of sources that could be helpful for a world peace essay, we would especially recommend checking the Global Peace Index report . It presents the most comprehensive data-driven analysis of current trends in world peace. It’s a credible report by the Institute for Economics and Peace, so you can cite it as a source in your aper.

Here are some other helpful resources where you can find information for your world peace essay:

- United Nations Peacekeeping

- International Peace Institute

- United States Institute of Peace

- European Union Institute for Security Studies

- Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

2. Create an Outline

Outlining is an essential aspect of the essay writing process. It helps you plan how you will connect all the facts to support your thesis statement.

To write an outline for your essay about peace, follow these steps:

- Determine your topic and develop a thesis statement .

- Choose the main points that will support your thesis and will be covered in your paper.

- Organize your ideas in a logical order.

- Think about transitions between paragraphs.

Here is an outline example for a “How to Achieve World Peace” essay. Check it out to get a better idea of how to structure your paper.

- Definition of world peace.

- The importance of global peace.

- Thesis statement: World peace is attainable through combined efforts on individual, societal, and global levels.

- Practive of non-violent communication.

- Development of healthy relationships.

- Promotion of conflict resolution skills.

- Promotion of democracy and human rights.

- Support of peacebuilding initiatives.

- Protection of cultural diversity.

- Encouragement of arms control and non-proliferation.

- Promotion of international law and treaties.

- Support of intercultural dialogue and understanding.

- Restated thesis.

- Call to action.

You can also use our free essay outline generator to structure your world peace essay.

3. Write Your World Peace Essay

Now, it’s time to use your outline to write an A+ paper. Here’s how to do it:

- Start with the introductory paragraph , which states the topic, presents a thesis, and provides a roadmap for your essay. If you need some assistance with this part, try our free introduction generator .

- Your essay’s main body should contain at least 3 paragraphs. Each of them should provide explanations and evidence to develop your argument.

- Finally, in your conclusion , you need to restate your thesis and summarize the points you’ve covered in the paper. It’s also a good idea to add a closing sentence reflecting on your topic’s significance or encouraging your audience to take action. Feel free to use our essay conclusion generator to develop a strong ending for your paper.

4. Revise and Proofread

Proofreading is a way to ensure your essay has no typos and grammar mistakes. Here are practical tips for revising your work:

- Take some time. Leaving your essay for a day or two before revision will give you a chance to look at it from another angle.

- Read out loud. To catch run-on sentences or unclear ideas in your writing, read it slowly and out loud. You can also use our Read My Essay to Me tool.

- Make a checklist . Create a list for proofreading to ensure you do not miss any important details, including structure, punctuation, capitalization, and formatting.

- Ask someone for feedback. It is always a good idea to ask your professor, classmate, or friend to read your essay and give you constructive criticism on the work.

- Note down the mistakes you usually make. By identifying your weaknesses, you can work on them to become a more confident writer.

🦄 World Peace Essay Writing Prompts

Looking for an interesting idea for your world peace essay? Look no further! Use our writing prompts to get a dose of inspiration.

How to Promote Peace in the Community Essay Prompt

Promoting peace in the world always starts in small communities. If people fight toxic narratives, negative stereotypes, and hate crimes, they will build a strong and united community and set a positive example for others.

In your essay on how to promote peace in the community, you can dwell on the following ideas:

- Explain the importance of accepting different opinions in establishing peace in your area.

- Analyze how fighting extremism in all its forms can unite the community and create a peaceful environment.

- Clarify what peace means in the context of your community and what factors contribute to or hinder it.

- Investigate the role of dialogue in resolving conflicts and building mutual understanding in the community.

How to Promote Peace as a Student Essay Prompt

Students, as an active part of society, can play a crucial role in promoting peace at various levels. From educational entities to worldwide conferences, they have an opportunity to introduce the idea of peace for different groups of people.

Check out the following fresh ideas for your essay on how to promote peace as a student:

- Analyze how information campaigns organized by students can raise awareness of peace-related issues.

- Discuss the impact of education in fostering a culture of peace.

- Explore how students can use social media to advocate for a peaceful world.

- Describe your own experience of taking part in peace-promoting campaigns or programs.

How Can We Maintain Peace in Our Society Essay Prompt

Maintaining peace in society is a difficult but achievable task that requires constant attention and effort from all members of society.

We have prepared ideas that can come in handy when writing an essay about how we can maintain peace in our society:

- Investigate the role of tolerance, understanding of different cultures, and respect for religions in promoting peace in society.

- Analyze the importance of peacekeeping organizations.

- Provide real-life examples of how people promote peace.

- Offer practical suggestions for how individuals and communities can work together to maintain peace.

Youth Creating a Peaceful Future Essay Prompt

Young people are the future of any country, as well as the driving force to create a more peaceful world. Their energy and motivation can aid in finding new methods of coping with global hate and violence.

In your essay, you can use the following ideas to show the role of youth in creating a peaceful world:

- Analyze the key benefits of youth involvement in peacekeeping.

- Explain why young people are leading tomorrow’s change today.

- Identify the main ingredients for building a peaceful generation with the help of young people’s initiatives.

- Investigate how adolescent girls can be significant agents of positive change in their communities.

Is World Peace Possible Essay Prompt

Whether or not the world can be a peaceful place is one of the most controversial topics. While most people who hear the question “Is a world without war possible?” will probably answer “no,” others still believe in the goodness of humanity.

To discuss in your essay if world peace is possible, use the following ideas:

- Explain how trade, communication, and technology can promote cooperation and the peaceful resolution of conflicts.

- Analyze the role of international organizations like the United Nations and the European Union in maintaining peace in the world.

- Investigate how economic inequality poses a severe threat to peace and safety.

- Dwell on the key individual and national interests that can lead to conflict and competition between countries.

✔️ World Peace Topics for Essays

To help get you started with writing, here’s a list of 200 topics you can use for your future essTo help get you started with writing a world peace essay, we’ve prepared a list of topics you can use:

- Defining peace

- Why peace is better: benefits of living in harmony

- Is world peace attainable? Theory and historical examples

- Sustainable peace: is peace an intermission of war?

- Peaceful coexistence: how a society can do without wars

- Peaceful harmony or war of all against all: what came first?

- The relationship between economic development and peace

- Peace and Human Nature: Can Humans Live without Conflicts ?

- Prerequisites for peace : what nations need to refrain from war?

- Peace as an unnatural phenomenon: why people tend to start a war?

- Peace as a natural phenomenon: why people avoid starting a war?

- Is peace the end of the war or its beginning?

- Hybrid war and hybrid peace

- What constitutes peace in the modern world

- Does two countries’ not attacking each other constitute peace?

- “Cold peace” in the international relations today

- What world religions say about world peace

- Defining peacemaking

- Internationally recognized symbols of peace

- World peace: a dream or a goal?

🌎 Peace Essay Topics on Pacifism

- History of pacifism: how the movement started and developed

- Role of the pacifist movement in the twentieth-century history

- Basic philosophical principles of pacifism

- Pacifism as philosophy and as a movement

- The peace sign: what it means

- How the pacifist movement began: actual causes

- The anti-war movements: what did the activists want?

- The relationship between pacifism and the sexual revolution

- Early pacifism: examples from ancient times

- Is pacifism a religion?

- Should pacifists refrain from any kinds of violence?

- Is the pacifist movement a threat to the national security?

- Can a pacifist work in law enforcement authorities?

- Pacifism and non-violence: comparing and contrasting

- The pacifist perspective on the concept of self-defense

- Pacifism in art: examples of pacifistic works of art

- Should everyone be a pacifist?

- Pacifism and diet: should every pacifist be a vegetarian ?

- How pacifists respond to oppression

- The benefits of an active pacifist movement for a country

✌️ Interesting Essay Titles about Peace

- Can the country that won a war occupy the one that lost?

- The essential peace treaties in history

- Should a country that lost a war pay reparations?

- Peace treaties that caused new, more violent wars

- Can an aggressor country be deprived of the right to have an army after losing a war?

- Non-aggression pacts do not prevent wars

- All the countries should sign non-aggression pacts with one another

- Peace and truces: differences and similarities

- Do countries pursue world peace when signing peace treaties?

- The treaty of Versailles: positive and negative outcomes

- Ceasefires and surrenders: the world peace perspective

- When can a country break a peace treaty?

- Dealing with refugees and prisoners of war under peace treaties

- Who should resolve international conflicts?

- The role of the United Nations in enforcing peace treaties

- Truce envoys’ immunities

- What does a country do after surrendering unconditionally?

- A separate peace: the ethical perspective

- Can a peace treaty be signed in modern-day hybrid wars?

- Conditions that are unacceptable in a peace treaty

🕊️ Research Topics on Peace and Conflict Resolution

- Can people be forced to stop fighting?

- Successful examples of peace restoration through the use of force

- Failed attempts to restore peace with legitimate violence

- Conflict resolution vs conflict transformation

- What powers peacemakers should not have

- Preemptive peacemaking: can violence be used to prevent more abuse?

- The status of peacemakers in the international law

- Peacemaking techniques: Gandhi’s strategies

- How third parties can reconcile belligerents

- The role of the pacifist movement in peacemaking

- The war on wars: appropriate and inappropriate approaches to peacemaking

- Mistakes that peacemakers often stumble upon

- The extent of peacemaking : when the peacemakers’ job is done

- Making peace and sustaining it: how peacemakers prevent future conflicts

- The origins of peacemaking

- What to do if peacemaking does not work

- Staying out: can peacemaking make things worse?

- A personal reflection on the effectiveness of peacemaking

- Prospects of peacemaking

- Personal experience of peacemaking

💡 War and Peace Essay Topics

- Counties should stop producing new types of firearms

- Countries should not stop producing new types of weapons

- Mutual assured destruction as a means of sustaining peace

- The role of nuclear disarmament in world peace

- The nuclear war scenario: what will happen to the world?

- Does military intelligence contribute to sustaining peace?

- Collateral damage: analyzing the term

- Can the defenders of peace take up arms?

- For an armed person, is killing another armed person radically different from killing an unarmed one? Ethical and legal perspectives

- Should a healthy country have a strong army?

- Firearms should be banned

- Every citizen has the right to carry firearms

- The correlation between gun control and violence rates

- The second amendment: modern analysis

- Guns do not kill: people do

- What weapons a civilian should never be able to buy

- Biological and chemical weapons

- Words as a weapon: rhetoric wars

- Can a pacifist ever use a weapon?

- Can dropping weapons stop the war?

☮️ Peace Title Ideas for Essays

- How the nuclear disarmament emblem became the peace sign

- The symbolism of a dove with an olive branch

- Native Americans’ traditions of peace declaration

- The mushroom cloud as a cultural symbol

- What the world peace awareness ribbon should look like

- What I would like to be the international peace sign

- The history of the International Day of Peace

- The peace sign as an accessory

- The most famous peace demonstrations

- Hippies’ contributions to the peace symbolism

- Anti-war and anti-military symbols

- How to express pacifism as a political position

- The rainbow as a symbol of peace

- Can a white flag be considered a symbol of peace?

- Examples of the inappropriate use of the peace sign

- The historical connection between the peace sign and the cannabis leaf sign

- Peace symbols in different cultures

- Gods of war and gods of peace: examples from the ancient mythology

- Peace sign tattoo: pros and cons

- Should the peace sign be placed on a national flag?

🌐 Essay Topics about Peace Language

- The origin and historical context of the word “peace”

- What words foreign languages use to denote “peace”

- What words, if any, should a pacifist avoid?

- The pacifist discourse: key themes

- Disintegration language: “us” vs “them”

- How to combat war propaganda

- Does political correctness promote world peace?

- Can an advocate of peace be harsh in his or her speeches?

- Effective persuasive techniques in peace communications and negotiations

- Analyzing the term “world peace”

- If the word “war” is forbidden, will wars stop?

- Is “peacemaking” a right term?

- Talk to the hand: effective and ineffective interpersonal communication techniques that prevent conflicts

- The many meanings of the word “peace”

- The pacifists’ language: when pacifists swear, yell, or insult

- Stressing similarities instead of differences as a tool of peace language

- The portrayal of pacifists in movies

- The portrayals of pacifists in fiction

- Pacifist lyrics: examples from the s’ music

- Poems that supported peace The power of the written word

- Peaceful coexistence: theory and practice

- Under what conditions can humans coexist peacefully?

- “A man is a wolf to another man”: the modern perspective

- What factors prevent people from committing a crime?

- Right for peace vs need for peace

- Does the toughening of punishment reduce crime?

- The Stanford prison experiment: implications

- Is killing natural?

- The possibility of universal love: does disliking always lead to conflicts?

- Basic income and the dynamics of thefts

- Hobbesian Leviathan as the guarantee of peace

- Is state-concentrated legitimate violence an instrument for reducing violence overall?

- Factors that undermine peaceful coexistence

- Living in peace vs living for peace

- The relationship between otherness and peacefulness

- World peace and human nature: the issue of attainability

- The most successful examples of peaceful coexistence

- Lack of peace as lack of communication

- Point made: counterculture and pacifism

- What Woodstock proved to world peace nonbelievers and opponents?

- Woodstock and peaceful coexistence: challenges and successes

- Peace, economics, and quality of life

- Are counties living in peace wealthier? Statistics and reasons

- Profits of peace and profits of war: comparison of benefits and losses

- Can a war improve the economy? Discussing examples

- What is more important for people: having appropriate living conditions or winning a war?

- How wars can improve national economies: the perspective of aggressors and defenders

- Peace obstructers: examples of interest groups that sustained wars and prevented peace

- Can democracies be at war with one another?

- Does the democratic rule in a country provide it with an advantage at war?

- Why wars destroy economies: examples, discussion, and counterarguments

- How world peace would improve everyone’s quality of life

- Peace and war today

- Are we getting closer to world peace? Violence rates, values change, and historical comparison

- The peaceful tomorrow: how conflicts will be resolved in the future if there are no wars

- Redefining war: what specific characteristics today’s wars have that make them different from previous centuries’ wars

- Why wars start today: comparing and contrasting the reasons for wars in the modern world to historical examples

- Subtle wars: how two countries can be at war with each other without having their armies collide in the battlefield

- Cyber peace: how cyberwars can be stopped

- Information as a weapon: how information today lands harder blows than bombs and missiles

- Information wars: how the abundance of information and public access to it have not, nonetheless, eliminated propaganda

- Peace through defeating: how ISIS is different from other states, and how can its violence be stopped

- Is world peace a popular idea? Do modern people mostly want peace or mainly wish to fight against other people and win?

- Personal contributions to world peace

- What can I do for attaining world peace? Personal reflection

- Respect as a means of attaining peace: why respecting people is essential not only on the level of interpersonal communications but also on the level of social good

- Peacefulness as an attitude: how one’s worldview can prevent conflicts

- Why a person engages in insulting and offending: analysis of psychological causes and a personal perspective

- A smile as an agent of peace: how simple smiling to people around you contributes to peacefulness

- Appreciating otherness: how one can learn to value diversity and avoid xenophobia

- Peace and love: how the two are inherently interconnected in everyone’s life

- A micro-level peacemaker: my experiences of resolving conflicts and bringing peace

- Forgiveness for the sake of peace: does forgiving other people contribute to peaceful coexistence or promote further conflicts?

- Noble lies: is it acceptable for a person to lie to avoid conflicts and preserve peace?

- What should a victim do? Violent and non-violent responses to violence

- Standing up for the weak : is it always right to take the side of the weakest?

- Self-defense, overwhelming emotions, and witnessing horrible violence: could I ever shoot another person?

- Are there “fair” wars, and should every war be opposed?

- Protecting peace: could I take up arms to prevent a devastating war?

- Reporting violence: would I participate in sending a criminal to prison?

- The acceptability of violence against perpetrators: personal opinion

- Nonviolent individual resistance to injustice

- Peace is worth it: why I think wars are never justified

- How I sustain peace in my everyday life

Learn more on this topic:

- If I Could Change the World Essay: Examples and Writing Guide

- Ending the Essay: Conclusions

- Choosing and Narrowing a Topic to Write About

- Introduction to Research

- How the U.S. Can Help Humanity Achieve World Peace

- Ten Steps to World Peace

- How World Peace is Possible

- World Peace Books and Articles

- World Peace and Nonviolence

- The Leader of World Peace Essay

- UNO and World Peace Essay

- Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to LinkedIn

- Share to email

So, there are a few days left before Halloween, one of the favorite American holidays both for kids and adults. Most probably, your teacher will ask to prepare a Halloween essay. And most probably, it is not the first Halloween essay that you need to prepare. We are sure that...

An investigative essay is a piece of writing based on the information you gather by investigating the topic. Unlike regular research or term paper, this assignment requires you to conduct interviews, study archival records, or visit relevant locations—in a word, inspect things personally. If you’re a fan of detective stories,...

A nationalism essay is focused on the idea of devotion and loyalty to one’s country and its sovereignty. In your paper, you can elaborate on its various aspects. For example, you might want to describe the phenomenon’s meaning or compare the types of nationalism. You might also be interested in...

![peace long essay Human Trafficking Essay Topics, Outline, & Example [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/rusty-wire-e1565360705483-284x153.jpg)

“People for sale” is a phrase that describes exactly what human trafficking is. It also makes for an attention-grabbing title for an essay on this subject. You are going to talk about a severe problem, so it’s crucial to hook the reader from the get-go. A human trafficking essay is...

![peace long essay 256 Advantages and Disadvantages Essay Topics [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/smiling-young-woman-284x153.jpg)

Is globalization a beneficial process? What are the pros and cons of a religious upbringing? Do the drawbacks of immigration outweigh the benefits? These questions can become a foundation for your advantages and disadvantages essay. And we have even more ideas to offer! There is nothing complicated about writing this...

This time you have to write a World War II essay, paper, or thesis. It means that you have a perfect chance to refresh those memories about the war that some of us might forget. So many words can be said about the war in that it seems you will...

![peace long essay 413 Science and Technology Essay Topics to Write About [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/scientist-working-in-science-and-chemical-for-health-e1565366539163-284x153.png)

Would you always go for Bill Nye the Science Guy instead of Power Rangers as a child? Were you ready to spend sleepless nights perfecting your science fair project? Or maybe you dream of a career in science? Then this guide by Custom-Writing.org is perfect for you. Here, you’ll find...

![peace long essay 256 Satirical Essay Topics & Satire Essay Examples [2024]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/classmates-learning-and-joking-at-school-e1565370536154-284x153.jpg)

A satire essay is a creative writing assignment where you use irony and humor to criticize people’s vices or follies. It’s especially prevalent in the context of current political and social events. A satirical essay contains facts on a particular topic but presents it in a comical way. This task...

![peace long essay 267 Music Essay Topics + Writing Guide [2024 Update]](https://custom-writing.org/blog/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/lady-is-playing-piano-284x153.jpg)

Your mood leaves a lot to be desired. Everything around you is getting on your nerves. But still, there’s one thing that may save you: music. Just think of all the times you turned on your favorite song, and it lifted your spirits! So, why not write about it in a music essay? In this article, you’ll find all the information necessary for this type of assignment: And...

Not everyone knows it, but globalization is not a brand-new process that started with the advent of the Internet. In fact, it’s been around throughout all of human history. This makes the choice of topics related to globalization practically endless. If you need help choosing a writing idea, this Custom-Writing.org...

In today’s world, fashion has become one of the most significant aspects of our lives. It influences everything from clothing and furniture to language and etiquette. It propels the economy, shapes people’s personal tastes, defines individuals and communities, and satisfies all possible desires and needs. In this article, Custom-Writing.org experts...

Early motherhood is a very complicated social problem. Even though the number of teenage mothers globally has decreased since 1991, about 12 million teen girls in developing countries give birth every year. If you need to write a paper on the issue of adolescent pregnancy and can’t find a good...

A very, very good paragraph. thanks

Peace and conflict studies actually is good field because is dealing on how to manage the conflict among the two state or country.

Keep it up. Our world earnestly needs peace

A very, very good paragraph.

United States Institute of Peace

Winning essays, 2013 national winning essays.

First Place: Molly Nemer of Henry Sibley High School in Mendota Heights, MN

- Grounded in Peace: Why Gender Matters

Second Place: Anna Mitchell of Plymouth, MI (Homeschool)

- Up and Out: Women’s Peacebuilding from the Ground Up in Liberia and Afghanistan

Third Place: Bo Yeon Jang of the International School Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam

- Womanhood in Peacemaking: Taking Advantage of Unity through Cultural Roles for a Successful Gendered Approach in Conflict Resolution

2012 national winning essay, “ Awakening Witness and Empowering Engagement: Leveraging New Media for Human Connections ,” by Emily Fox-Penner of the Maret School in Washington, D.C., addressed the essay topic of new media and peacebuilding by examining its role in Egypt in 2011 and Kenya in 2007 (link is the same as it is now from last year)

2011 national winning essay, "Mimes for Good Governance: The Importance of Culture and Morality in the Fight Against Corruption," by Kathryn Botto from the Liberal Arts and Science Academy in Austin, Texas discusses the role of society and culture in dealing with curruption, using Colombia and Kyrgyzstan as case studies.

2010 national winning essay, " Fighting for Local publications in a Globalized World: Unity, Strategy, and Government Support " , by Margaret E. Hardy from Lick-Wilmerding High School in San Francisco, California, discusses necessary conditions for nonviolent movement to successfully control local publications.

2009 national winning essay, "Responding to Crimes against Humanity: Prevention, Deployment, and Localization" , by Sophia Sanchez from Ladue Horton Watkins High School in Saint Louis, Missouri, discusses the role of international actors in protecting civilians from crimes against humanity.

2008 national winning essay , "Resolving Water Conflicts Through the Establishment of Water Authorities, " by Callie Smith from Girls Preparatory School in Chatanooga, Tennessee, discusses how natural publications can be managed to build peace, using case studies from Central Asia and Yemen.

2007 national winning essay , " Reintegrating Children, Building Peace: Interaction, Education, and Youth Participation ," by Wendy Cai from Corona Del Sol High School in Tempe, Arizona, discusses the reintegration of child soldiers into society, using Sierra Leone and Uganda as case studies.

2006 national winning essay , " Defusing Nuclear Tensions Through Internationally Supported Bilateral Collaborations ," by Kona Shen from The Northwest School in Seattle, Washington, compares the decision of Argentina and Brazil to forego nuclear arms development with the nuclear arms race between India and Pakistan.

2005 national winning essay , " Finding Peace: Japan and Cambodia ," by Jessica Perrigan from the Duchesne Academy in Omaha, Nebraska, explores how education is the key to democracy.

2004 national winning essay , " Establishing Peaceful and Stable Postwar Societies Through Effective Rebuilding Strategy ," by Vivek Viswanathan from Herricks High School in New Hyde Park, New York explores the lessons of the Marshall Plan and international efforts in Somalia in an examination of the challenges of post-conflict reconstruction.

2003 national winning essay , " Kuwait and Kosovo: The Harm Principle and Humanitarian War ," by Kevin Kiley from Granite Bay High School in Granite Bay, California, examines the 1990 Gulf War and NATO's intervention in Kosovo to see how they measure up against the criteria of just war.

2002 national winning essay , " Safeguarding Human Rights and Preventing Conflict through U.S. Peacekeeping ," by David Epstein from Pikesville High School in Baltimore, Maryland, cites several examples of appropriate use of American power aimed at putting a stop to crimes against humanity and ending conflict.

2001 national winning essay , " Somalia and Sudan: Sovereignty and Humanitarianism ," by Stefanie Nelson from Bountiful High School in Bountiful, Utah, examines the dynamics of the competing philosophies of sovereignty and humanitarianism in third-party intervention found in civil conflicts in the Sudan and Somalia.

2000 national winning essay , " Promoting Global and Regional Security in the Post-Cold War World ," by Elspeth Simpson from Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas, looks at the U.S. policies that led to intervention in Colombia and North Korea and considers the effectiveness of actions based on humanitarian assistance and national and global security.

1999 national winning essay , " Preventive Diplomacy in the Iraq-Kuwait Dispute and in the Venezuela Border Dispute ," by Jean Marie Hicks of St. Thomas More High School in Rapid City, South Dakota, explores the cases of preventive diplomacy seen in disputes between Iraq and Kuwait and in border disputes involving Venezuela.

1998 national winning essay , " How Should Nations be Reconciled ," by Tim Shenk from Eastern Mennonite High School in Harrisonburg, Virginia, uses South Africa and Bosnia as examples to examine the manner in which war crimes should be accounted for to ensure stable and lasting peace.

1997 national winning essay , " A Just and Lasting Peace ," by Joseph Bernabucci from St. Alban's School in Washington, D.C., examines the steps that can be taken to support successful implementation of a peace agreements and addresses causes of the conflicts by exploring what can be done to discourage renewed violence.

1996 national winning essay , " America and the New World Order ," by Richard Lee from Irmo High School in Columbia, South Carolina, defines U.S. national security interests and gives his criteria for U.S. intervention by examining past cases of intervention.

Beyond Intractability

The Hyper-Polarization Challenge to the Conflict Resolution Field: A Joint BI/CRQ Discussion BI and the Conflict Resolution Quarterly invite you to participate in an online exploration of what those with conflict and peacebuilding expertise can do to help defend liberal democracies and encourage them live up to their ideals.

Follow BI and the Hyper-Polarization Discussion on BI's New Substack Newsletter .

Hyper-Polarization, COVID, Racism, and the Constructive Conflict Initiative Read about (and contribute to) the Constructive Conflict Initiative and its associated Blog —our effort to assemble what we collectively know about how to move beyond our hyperpolarized politics and start solving society's problems.

By Michelle Maiese

September 2003

What it Means to Build a Lasting Peace

It should be noted at the outset that there are two distinct ways to understand peacebuilding. According the United Nations (UN) document An Agenda for Peace [1], peacebuilding consists of a wide range of activities associated with capacity building, reconciliation , and societal transformation . Peacebuilding is a long-term process that occurs after violent conflict has slowed down or come to a halt. Thus, it is the phase of the peace process that takes place after peacemaking and peacekeeping.

Many non-governmental organizations (NGOs), on the other hand, understand peacebuilding as an umbrella concept that encompasses not only long-term transformative efforts, but also peacemaking and peacekeeping . In this view, peacebuilding includes early warning and response efforts, violence prevention , advocacy work, civilian and military peacekeeping , military intervention , humanitarian assistance , ceasefire agreements , and the establishment of peace zones.

In the interests of keeping these essays a reasonable length, this essay primarily focuses on the narrower use of the term "peacebuilding." For more information about other phases of the peace process, readers should refer to the knowledge base essays about violence prevention , peacemaking and peacekeeping , as well as the essay on peace processes which is what we use as our "umbrella" term.

In this narrower sense, peacebuilding is a process that facilitates the establishment of durable peace and tries to prevent the recurrence of violence by addressing root causes and effects of conflict through reconciliation , institution building, and political as well as economic transformation.[1] This consists of a set of physical, social, and structural initiatives that are often an integral part of post-conflict reconstruction and rehabilitation.

It is generally agreed that the central task of peacebuilding is to create positive peace, a "stable social equilibrium in which the surfacing of new disputes does not escalate into violence and war."[2] Sustainable peace is characterized by the absence of physical and structural violence , the elimination of discrimination, and self-sustainability.[3] Moving towards this sort of environment goes beyond problem solving or conflict management. Peacebuilding initiatives try to fix the core problems that underlie the conflict and change the patterns of interaction of the involved parties.[4] They aim to move a given population from a condition of extreme vulnerability and dependency to one of self-sufficiency and well-being.[5]

To further understand the notion of peacebuilding, many contrast it with the more traditional strategies of peacemaking and peacekeeping. Peacemaking is the diplomatic effort to end the violence between the conflicting parties, move them towards nonviolent dialogue, and eventually reach a peace agreement. Peacekeeping , on the other hand, is a third-party intervention (often, but not always done by military forces) to assist parties in transitioning from violent conflict to peace by separating the fighting parties and keeping them apart. These peacekeeping operations not only provide security, but also facilitate other non-military initiatives.[6]

Some draw a distinction between post-conflict peacebuilding and long-term peacebuilding. Post-conflict peacebuilding is connected to peacekeeping, and often involves demobilization and reintegration programs, as well as immediate reconstruction needs.[7] Meeting immediate needs and handling crises is no doubt crucial. But while peacemaking and peacekeeping processes are an important part of peace transitions, they are not enough in and of themselves to meet longer-term needs and build a lasting peace.

Long-term peacebuilding techniques are designed to fill this gap, and to address the underlying substantive issues that brought about conflict. Various transformation techniques aim to move parties away from confrontation and violence, and towards political and economic participation, peaceful relationships, and social harmony.[8]

This longer-term perspective is crucial to future violence prevention and the promotion of a more peaceful future. Thinking about the future involves articulating desirable structural, systemic, and relationship goals. These might include sustainable economic development, self-sufficiency, equitable social structures that meet human needs, and building positive relationships.[9]

Peacebuilding measures also aim to prevent conflict from reemerging. Through the creation of mechanisms that enhance cooperation and dialogue among different identity groups , these measures can help parties manage their conflict of interests through peaceful means. This might include building institutions that provide procedures and mechanisms for effectively handling and resolving conflict.[10] For example, societies can build fair courts, capacities for labor negotiation, systems of civil society reconciliation, and a stable electoral process.[11] Such designing of new dispute resolution systems is an important part of creating a lasting peace.

In short, parties must replace the spiral of violence and destruction with a spiral of peace and development, and create an environment conducive to self-sustaining and durable peace.[12] The creation of such an environment has three central dimensions: addressing the underlying causes of conflict, repairing damaged relationships and dealing with psychological trauma at the individual level. Each of these dimensions relies on different strategies and techniques.

The Structural Dimension: Addressing Root Causes

The structural dimension of peacebuilding focuses on the social conditions that foster violent conflict. Many note that stable peace must be built on social, economic, and political foundations that serve the needs of the populace.[13] In many cases, crises arise out of systemic roots. These root causes are typically complex, but include skewed land distribution, environmental degradation, and unequal political representation.[14] If these social problems are not addressed, there can be no lasting peace.

Thus, in order to establish durable peace, parties must analyze the structural causes of the conflict and initiate social structural change. The promotion of substantive and procedural justice through structural means typically involves institution building and the strengthening of civil society .

Avenues of political and economic transformation include social structural change to remedy political or economic injustice, reconstruction programs designed to help communities ravaged by conflict revitalize their economies, and the institution of effective and legitimate restorative justice systems.[15] Peacebuilding initiatives aim to promote nonviolent mechanisms that eliminate violence, foster structures that meet basic human needs , and maximize public participation .[16]

To provide fundamental services to its citizens, a state needs strong executive, legislative, and judicial institutions.[17] Many point to democratization as a key way to create these sorts of peace-enhancing structures. Democratization seeks to establish legitimate and stable political institutions and civil liberties that allow for meaningful competition for political power and broad participation in the selection of leaders and policies.[18] It is important for governments to adhere to principles of transparency and predictability, and for laws to be adopted through an open and public process.[19] For the purpose of post-conflict peacebuilding, the democratization process should be part of a comprehensive project to rebuild society's institutions.

Political structural changes focus on political development, state building , and the establishment of effective government institutions. This often involves election reform, judicial reform, power-sharing initiatives, and constitutional reform. It also includes building political parties, creating institutions that provide procedures and mechanisms for effectively handling and resolving conflict, and establishing mechanisms to monitor and protect human rights . Such institution building and infrastructure development typically requires the dismantling, strengthening, or reformation of old institutions in order to make them more effective.

It is crucial to establish and maintain rule of law, and to implement rules and procedures that constrain the powers of all parties and hold them accountable for their actions.[20] This can help to ease tension, create stability, and lessen the likelihood of further conflict. For example, an independent judiciary can serve as a forum for the peaceful resolution of disputes and post-war grievances.[21]

In addition, societies need a system of criminal justice that deters and punishes banditry and acts of violence.[22] Fair police mechanisms must be established and government officials and members of the police force must be trained to observe basic rights in the execution of their duties.[23] In addition, legislation protecting minorities and laws securing gender equality should be advanced. Courts and police forces must be free of corruption and discrimination.

But structural change can also be economic. Many note that economic development is integral to preventing future conflict and avoiding a relapse into violence.[24] Economic factors that put societies at risk include lack of employment opportunities, food scarcity, and lack of access to natural resources or land. A variety of social structural changes aim to eliminate the structural violence that arises out of a society's economic system. These economic and social reforms include economic development programs, health care assistance, land reform, social safety nets, and programs to promote agricultural productivity.[25]

Economic peacebuilding targets both the micro- and macro-level and aims to create economic opportunities and ensure that the basic needs of the population are met. On the microeconomic level, societies should establish micro-credit institutions to increase economic activity and investment at the local level, promote inter-communal trade and an equitable distribution of land, and expand school enrollment and job training.[26] On the macroeconomic level, the post-conflict government should be assisted in its efforts to secure the economic foundations and infrastructure necessary for a transition to peace.[27]

The Relational Dimension

A second integral part of building peace is reducing the effects of war-related hostility through the repair and transformation of damaged relationships. The relational dimension of peacebuilding centers on reconciliation , forgiveness , trust building , and future imagining . It seeks to minimize poorly functioning communication and maximize mutual understanding.[28]

Many believe that reconciliation is one of the most effective and durable ways to transform relationships and prevent destructive conflicts.[29] The essence of reconciliation is the voluntary initiative of the conflicting parties to acknowledge their responsibility and guilt. Parties reflect upon their own role and behavior in the conflict, and acknowledge and accept responsibility for the part they have played. As parties share their experiences, they learn new perspectives and change their perception of their "enemies." There is recognition of the difficulties faced by the opposing side and of their legitimate grievances, and a sense of empathy begins to develop. Each side expresses sincere regret and remorse, and is prepared to apologize for what has transpired. The parties make a commitment to let go of anger , and to refrain from repeating the injury. Finally, there is a sincere effort to redress past grievances and compensate for the damage done. This process often relies on interactive negotiation and allows the parties to enter into a new mutually enriching relationship.[30]

One of the essential requirements for the transformation of conflicts is effective communication and negotiation at both the elite and grassroots levels . Through both high- and community-level dialogues , parties can increase their awareness of their own role in the conflict and develop a more accurate perception of both their own and the other group's identity .[31] As each group shares its unique history, traditions, and culture, the parties may come to understand each other better. International exchange programs and problem-solving workshops are two techniques that can help to change perceptions, build trust , open communication , and increase empathy .[32] For example, over the course of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the main antagonists have sometimes been able to build trust through meeting outside their areas , not for formal negotiations, but simply to better understand each other.[33]

If these sorts of bridge-building communication systems are in place, relations between the parties can improve and any peace agreements they reach will more likely be self-sustaining.[34] (The Israeli-Palestinian situation illustrates that there are no guarantees, however.) Various mass communication and education measures, such as peace radio and TV , peace-education projects , and conflict-resolution training , can help parties to reach such agreements.[35] And dialogue between people of various ethnicities or opposing groups can lead to deepened understanding and help to change the demonic image of the enemy group.[36] It can also help parties to overcome grief, fear, and mistrust and enhance their sense of security.

A crucial component of such dialogue is future imaging , whereby parties form a vision of the commonly shared future they are trying to build. Conflicting parties often have more in common in terms of their visions of the future than they do in terms of their shared and violent past.[37] The thought is that if they know where they are trying to go, it will be easier to get there.

Another way for the parties to build a future together is to pursue joint projects that are unrelated to the conflict's core issues and center on shared interests. This can benefit the parties' relationship. Leaders who project a clear and hopeful vision of the future and the ways and means to get there can play a crucial role here.

But in addition to looking towards the future, parties must deal with their painful past. Reconciliation not only envisions a common, connected future, but also recognizes the need to redress past wrongdoing.[38] If the parties are to renew their relationship and build an interdependent future, what has happened must be exposed and then forgiven .

Indeed, a crucial part of peacebuilding is addressing past wrongdoing while at the same time promoting healing and rule of law.[39] Part of repairing damaged relationships is responding to past human rights violations and genocide through the establishment of truth commissions , fact-finding missions, and war crimes tribunals .[40] These processes attempt to deal with the complex legal and emotional issues associated with human rights abuses and ensure that justice is served. It is commonly thought that past injustice must be recognized, and the perpetrators punished if parties wish to achieve reconciliation.

However, many note that the retributive justice advanced by Western legal systems often ignores the needs of victims and exacerbates wounds.[41] Many note that to advance healing between the conflicting parties, justice must be more reparative in focus. Central to restorative justice is its future-orientation and its emphasis on the relationship between victims and offenders. It seeks to engage both victims and offenders in dialogue and make things right by identifying their needs and obligations.[42] Having community-based restorative justice processes in place can help to build a sustainable peace.

The Personal Dimension

The personal dimension of peacebuilding centers on desired changes at the individual level. If individuals are not able to undergo a process of healing, there will be broader social, political, and economic repercussions.[43] The destructive effects of social conflict must be minimized, and its potential for personal growth must be maximized.[44] Reconstruction and peacebuilding efforts must prioritize treating mental health problems and integrate these efforts into peace plans and rehabilitation efforts.

In traumatic situations, a person is rendered powerless and faces the threat of death and injury. Traumatic events might include a serious threat or harm to one's family or friends, sudden destruction of one's home or community, and a threat to one's own physical being.[45] Such events overwhelm an individual's coping resources, making it difficult for the individual to function effectively in society.[46] Typical emotional effects include depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. After prolonged and extensive trauma, a person is often left with intense feelings that negatively influence his/her psychological well-being. After an experience of violence, an individual is likely to feel vulnerable, helpless, and out of control in a world that is unpredictable.[47]

Building peace requires attention to these psychological and emotional layers of the conflict. The social fabric that has been destroyed by war must be repaired, and trauma must be dealt with on the national, community, and individual levels.[48] At the national level, parties can accomplish widespread personal healing through truth and reconciliation commissions that seek to uncover the truth and deal with perpetrators. At the community level, parties can pay tribute to the suffering of the past through various rituals or ceremonies, or build memorials to commemorate the pain and suffering that has been endured.[49] Strong family units that can rebuild community structures and moral environments are also crucial.

At the individual level, one-on-one counseling has obvious limitations when large numbers of people have been traumatized and there are insufficient resources to address their needs. Peacebuilding initiatives must therefore provide support for mental health infrastructure and ensure that mental health professionals receive adequate training. Mental health programs should be adapted to suit the local context, and draw from traditional and communal practice and customs wherever possible.[50] Participating in counseling and dialogue can help individuals to develop coping mechanisms and to rebuild their trust in others.[51]

If it is taken that psychology drives individuals' attitudes and behaviors, then new emphasis must be placed on understanding the social psychology of conflict and its consequences. If ignored, certain victims of past violence are at risk for becoming perpetrators of future violence.[52] Victim empowerment and support can help to break this cycle.

Peacebuilding Agents

Peacebuilding measures should integrate civil society in all efforts and include all levels of society in the post-conflict strategy. All society members, from those in elite leadership positions, to religious leaders, to those at the grassroots level, have a role to play in building a lasting peace. Many apply John Paul Lederach's model of hierarchical intervention levels to make sense of the various levels at which peacebuilding efforts occur.[53]

Because peace-building measures involve all levels of society and target all aspects of the state structure, they require a wide variety of agents for their implementation. These agents advance peace-building efforts by addressing functional and emotional dimensions in specified target areas, including civil society and legal institutions.[54] While external agents can facilitate and support peacebuilding, ultimately it must be driven by internal forces. It cannot be imposed from the outside.

Various internal actors play an integral role in peacebuilding and reconstruction efforts. The government of the affected country is not only the object of peacebuilding, but also the subject. While peacebuilding aims to transform various government structures, the government typically oversees and engages in this reconstruction process. A variety of the community specialists, including lawyers, economists, scholars, educators, and teachers, contribute their expertise to help carry out peacebuilding projects. Finally, a society's religious networks can play an important role in establishing social and moral norms.[55]

Nevertheless, outside parties typically play a crucial role in advancing such peacebuilding efforts. Few peacebuilding plans work unless regional neighbors and other significant international actors support peace through economic development aid and humanitarian relief .[56] At the request of the affected country, international organizations can intervene at the government level to transform established structures.[57] They not only provide monetary support to post-conflict governments, but also assist in the restoration of financial and political institutions. Because their efforts carry the legitimacy of the international community, they can be quite effective.

Various institutions provide the necessary funding for peacebuilding projects. While international institutions are the largest donors, private foundations contribute a great deal through project-based financing.[58] In addition, regional organizations often help to both fund and implement peacebuilding strategies. Finally, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) often carry out small-scale projects to strengthen countries at the grassroots level. Not only traditional NGOs but also the business and academic community and various grassroots organizations work to further these peace-building efforts. All of the groups help to address "the limits imposed on governmental action by limited resources, lack of consensus, or insufficient political will."[59]

Some suggest that governments, NGOs, and intergovernmental agencies need to create categories of funding related to conflict transformation and peacebuilding.[60] Funds are often difficult to secure when they are intended to finance preventive action. And middle-range initiatives, infrastructure building, and grassroots projects do not typically attract significant funding, even though these sorts of projects may have the greatest potential to sustain long-term conflict transformation.[61] Those providing resources for peacebuilding initiatives must look to fill these gaps. In addition, external actors must think through the broader ramifications of their programs.[62] They must ensure that funds are used to advance genuine peacebuilding initiatives rather than be swallowed up by corrupt leaders or channeled into armed conflict.

But as already noted, higher-order peace, connected to improving local capacities, is not possible simply through third-party intervention.[63] And while top-down approaches are important, peace must also be built from the bottom up. Many top-down agreements collapse because the ground below has not been prepared. Top-down approaches must therefore be buttressed, and relationships built.

Thus, an important task in sustaining peace is to build a peace constituency within the conflict setting. Middle-range actors form the core of a peace constituency. They are more flexible than top-level leaders, and less vulnerable in terms of daily survival than those at the grassroots level.[64] Middle-range actors who strive to build bridges to their counterparts across the lines of conflict are the ones best positioned to sustain conflict transformation. This is because they have an understanding of the nuances of the conflict setting, as well as access to the elite leadership .

Many believe that the greatest resource for sustaining peace in the long term is always rooted in the local people and their culture.[65] Parties should strive to understand the cultural dimension of conflict, and identify the mechanisms for handling conflict that exist within that cultural setting. Building on cultural resources and utilizing local mechanisms for handling disputes can be quite effective in resolving conflicts and transforming relationships. Initiatives that incorporate citizen-based peacebuilding include community peace projects in schools and villages, local peace commissions and problem-solving workshops , and a variety of other grassroots initiatives .

Effective peacebuilding also requires public-private partnerships in addressing conflict and greater coordination among the various actors.[66] International governmental organizations, national governments, bilateral donors, and international and local NGOs need to coordinate to ensure that every dollar invested in peacebuilding is spent wisely.[67] To accomplish this, advanced planning and intervention coordination is needed.

There are various ways to attempt to coordinate peace-building efforts. One way is to develop a peace inventory to keep track of which agents are doing various peace-building activities. A second is to develop clearer channels of communication and more points of contact between the elite and middle ranges. In addition, a coordination committee should be instituted so that agreements reached at the top level are actually capable of being implemented.[68] A third way to better coordinate peace-building efforts is to create peace-donor conferences that bring together representatives from humanitarian organizations, NGOs, and the concerned governments. It is often noted that "peacebuilding would greatly benefit from cross-fertilization of ideas and expertise and the bringing together of people working in relief, development, conflict resolution, arms control, diplomacy, and peacekeeping."[69] Lastly, there should be efforts to link internal and external actors. Any external initiatives must also enhance the capacity of internal resources to build peace-enhancing structures that support reconciliation efforts throughout a society.[70] In other words, the international role must be designed to fit each case.

[1] Boutros-Ghali, Boutros. An Agenda for Peace. New York: United Nations 1995 .

[1a] SAIS, "The Conflict Management Toolkit: Approaches," The Conflict Management Program, Johns Hopkins University [available at: http://www.sais-jhu.edu/resources/middle-east-studies/conflict-management-toolkit

[2] Henning Haugerudbraaten, "Peacebuilding: Six Dimensions and Two Concepts," Institute For Security Studies. [available at: http://www.iss.co.za/Pubs/ASR/7No6/Peacebuilding.html ]

[3] Luc Reychler, "From Conflict to Sustainable Peacebuilding: Concepts and Analytical Tools," in Peacebuilding: A Field Guide , Luc Reychler and Thania Paffenholz, eds. (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Inc., 2001), 12.

[4] Reychler, 12.

[5] John Paul Lederach, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies . (Washington, D.C., United States Institute of Peace, 1997), 75.

[6] SAIS, [available at: http://www.sais-jhu.edu/resources/middle-east-studies/conflict-management-toolkit ]

[7] Michael Doyle and Nicholas Sambanis. "Building Peace: Challenges and Strategies After Civil War," The World Bank Group. [available at: http://www.chs.ubc.ca/srilanka/PDFs/Building%20peace--challenges%20and%20strategies.pdf ] 3.

[8] Doyle and Sambanis, 2

[9] Lederach, 77.

[11] Doyle and Sambanis, 5.

[13] Haugerudbraaten

[14] Haugerudbraaten

[16] Lederach, 83.

[19] Neil J. Kritz, "The Rule of Law in the Post-Conflict Phase: Building a Stable Peace," in Managing Global Chaos: Sources or and Responses to International Conflict , eds. Chester A. Crocker and Fen Osler Hampson with Pamela Aall. (Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press, 1996), 593.

[20] Kritz, 588.

[21] Kritz, 591.

[22] Kritz, 591.

[25] Michael Lund, "A Toolbox for Responding to Conflicts and Building Peace," In Peacebuilding: A Field Guide , Luc Reychler and Thania Paffenholz, eds. (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, Inc., 2001), 18.

[27] These issues are discussed in detail in the set of essays on development in this knowledge base.

[28] Lederach, 82.

[29] Hizkias Assefa, "Reconciliation," in Peacebuilding: A Field Guide , Luc Reychler and Thania Paffenholz, eds. (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, Inc., 2001), 342.

[30] Assefa, 340.

[33] Kathleen Stephens, "Building Peace in Deeply Rooted Conflicts: Exploring New Ideas to Shape the Future" INCORE, 1997.

[34] Reychler, 13.

[35] Lund, 18.

[37] Lederach, 77.

[38] Lederach, 31.

[39] Howard Zehr, "Restorative Justice," In Peacebuilding: A Field Guide , Luc Reychler and Thania Paffenholz, eds. (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, Inc., 2001), 330.

[41] Zehr, 330.

[42] Zehr, 331.

[44] Lederach, 82.

[45] Hugo van der Merwe and Tracy Vienings, "Coping with Trauma," in Peacebuilding: A Field Guide, Luc Reychler and Thania Paffenholz, eds. (Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Reinner Publishers, Inc., 2001), 343.

[46] van der Merwe, 343.

[47] van der Merwe, 345.

[48] van der Merwe, 343.

[49] van der Merwe, 344.

[51] van der Merwe, 347.

[52] van der Merwe, 344.

[53] John Paul Lederach, Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies, Chapter 4.

[56] Doyle and Sambanis, 18.

[59] Stephens.

[60] Lederach, 89.

[61] Lederach, 92.

[62] Lederach, 91.

[63] Doyle and Sambanis, 25.

[64] Lederach, 94.

[65] Lederach, 94.

[66] Stephens.

[67] Doyle and Sambanis, 23.

[68] Lederach, 100.

[69] Lederach, 101.

[70] Lederach, 103.

Use the following to cite this article: Maiese, Michelle. "Peacebuilding." Beyond Intractability . Eds. Guy Burgess and Heidi Burgess. Conflict Information Consortium, University of Colorado, Boulder. Posted: September 2003 < http://www.beyondintractability.org/essay/peacebuilding >.

Additional Resources

The intractable conflict challenge.

Our inability to constructively handle intractable conflict is the most serious, and the most neglected, problem facing humanity. Solving today's tough problems depends upon finding better ways of dealing with these conflicts. More...

Selected Recent BI Posts Including Hyper-Polarization Posts

- Crisis, Contradiction, Certainty, and Contempt -- Columbia Professor Peter Coleman, an expert on intractable conflict, reflects on the intractable conflict occurring on his own campus, suggesting "ways out" that would be better for everyone.

- Massively Parallel Peace and Democracy Building Links for the Week of April 28, 2024 -- New suggested readings from colleagues and the Burgesses.

- Attack the Problem, Not the People -- "Separate the people from the problem" might be the most often violated fundamental conflict resolution principle, even by people who know better. And it is hurting us.

Get the Newsletter Check Out Our Quick Start Guide

Educators Consider a low-cost BI-based custom text .

Constructive Conflict Initiative

Join Us in calling for a dramatic expansion of efforts to limit the destructiveness of intractable conflict.

Things You Can Do to Help Ideas

Practical things we can all do to limit the destructive conflicts threatening our future.

Conflict Frontiers