- Reference Works

- Children, Youths, & Families

- Health & Mental Health

- Practice & Policy

- NASW Standards

- Children & Schools

- Health & Social Work

- Social Work

- Social Work Abstracts

Social Work Research

- Calls for Papers

- Faculty Center

- Librarian Center

- Student Center

- Booksellers

- Advertisers

- Copyrights & Permissions

- eBook Support

- Write for Us

NASW members can access articles online at: Social Work Research

Social Work Research publishes exemplary research to advance the development of knowledge and inform social work practice. Widely regarded as the outstanding journal in the field, it includes analytic reviews of research, theoretical articles pertaining to social work research, evaluation studies, and diverse research studies that contribute to knowledge about social work issues and problems.

Related Pages

Recent news and updates.

- 4/16/2024: 2025 SSWR Awards: Calls for Nominations Now Open! Deadline: June 30, 2024

- March is Social Work Month: Empowering Social Workers

- 3/1/2024: Abstract Submission Site Now Open! Submission Deadline: April 15, 2024

- 1/5/2024: SSWR Strategic Plan 2024-2028: Learn about our new strategic plan set to inform how we address complex issues.

- 10/17/2023: Social Work Leadership Roundtable Joint Statement on Peace for Israel and Palestine.

- Videos: Conference Invited Sessions & Brief & Brilliant Talks

- Videos: RCDC Training Webinar Series

- Video: Guidelines for Forming a SSWR SIG

- Anti-Harassment and Code of Ethics (Updated 12/15/2020)

- Summary of Actions Taken: policy statements, sponsorship, sign-on letters

- Follow SSWR: Twitter | Instagram | Facebook | YouTube

SSWR Strategic Plan 2024-2028: Learn about our new strategic plan set to inform how we address complex issues.

Building Capacity to Advancing Social Work Science that Informs Solutions to Complex Societal Challenges [ View ]

RCDC Training Webinar Series

Jsswr journal.

The Journal of the Society for Social Work and Research is a peer-reviewed publication dedicated to presenting innovative, rigorous original research on social problems, intervention programs, and policies. [ view more ]

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Is College Worth It?

1. labor market and economic trends for young adults, table of contents.

- Labor force trends and economic outcomes for young adults

- Economic outcomes for young men

- Economic outcomes for young women

- Wealth trends for households headed by a young adult

- The importance of a four-year college degree

- Getting a high-paying job without a college degree

- Do Americans think their education prepared them for the workplace?

- Is college worth the cost?

- Acknowledgments

- The American Trends Panel survey methodology

- Current Population Survey methodology

- Survey of Consumer Finances methodology

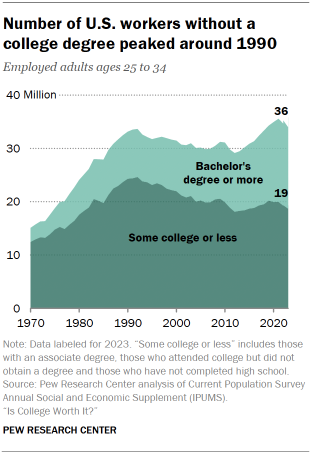

A majority of the nation’s 36 million workers ages 25 to 34 have not completed a four-year college degree. In 2023, there were 19 million young workers who had some college or less education, including those who had not finished high school.

The overall number of employed young adults has grown over the decades as more young women joined the workforce. The number of employed young adults without a college degree peaked around 1990 at 25 million and then started to fall, as more young people began finishing college .

This chapter looks at the following key labor market and economic trends separately for young men and young women by their level of education:

Labor force participation

- Individual earnings

Household income

- Net worth 1

When looking at how young adults are doing in the job market, it generally makes the most sense to analyze men and women separately. They tend to work in different occupations and have different career patterns, and their educational paths have diverged in recent decades.

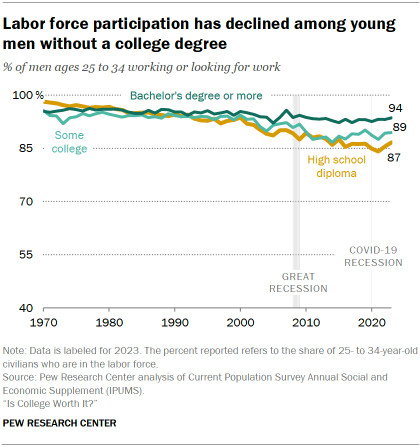

In 1970, almost all young men whose highest educational attainment was a high school diploma (98%) were in the labor force, meaning they were working or looking for work. By 2013, only 88% of high school-educated young men were in the labor force. Today, that share is 87%.

Similarly, 96% of young men whose highest attainment was some college education were in the labor force in 1970. Today, the share is 89%.

By comparison, labor force participation among young men with at least a bachelor’s degree has remained relatively stable these past few decades. Today, 94% of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree are in the labor force.

The long-running decline in the labor force participation of young men without a bachelor’s degree may be due to several factors, including declining wages , the types of jobs available to this group becoming less desirable, rising incarceration rates and the opioid epidemic . 2

Looking at labor force and earnings trends over the past several decades, it’s important to keep in mind broader forces shaping the national job market.

The Great Recession officially ended in June 2009, but the national job market recovered slowly . At the beginning of the Great Recession in the fourth quarter of 2007, the national unemployment rate was 4.6%. Unemployment peaked at 10.4% in the first quarter of 2010. It was not until the fourth quarter of 2016 that unemployment finally returned to its prerecession level (4.5%).

Studies suggest that things started to look up for less-skilled workers around 2014. Among men with less education, hourly earnings began rising in 2014 after a decade of stagnation. Wage growth for low-wage workers also picked up in 2014. The tightening labor markets in the last five years of the expansion after the Great Recession improved the labor market prospects of “vulnerable workers” considerably.

The COVID-19 pandemic interrupted the tight labor market, but the COVID-19 recession and recovery were quite different from the Great Recession in their job market impact. The more recent recession was arguably more severe, as the national unemployment rate reached 12.9% in the second quarter of 2020. But it was short – officially lasting two months, compared with the 18-month Great Recession – and the labor market bounced back much quicker. Unemployment was 3.3% before the COVID-19 recession; three years later, unemployment had once again returned to that level.

Full-time, full-year employment

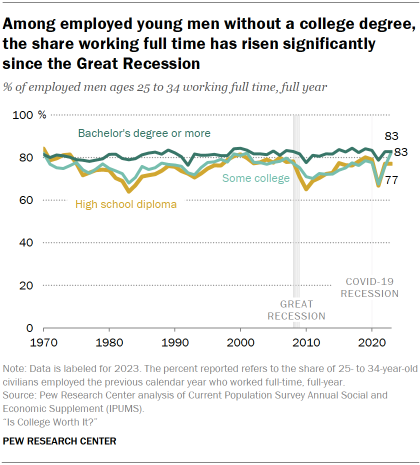

Since the Great Recession of 2007-09, young men without a four-year college degree have seen a significant increase in the average number of hours they work.

- Today, 77% of young workers with a high school education work full time, full year, compared with 69% in 2011.

- 83% of young workers with some college education work full time, full year, compared with 70% in 2011.

The share of young men with a college degree who work full time, year-round has remained fairly steady in recent decades – at about 80% – and hasn’t fluctuated with good or bad economic cycles.

Annual earnings

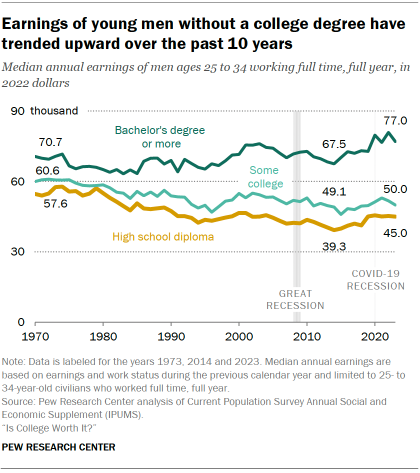

Annual earnings for young men without a college degree were on a mostly downward path from 1973 until roughly 10 years ago (with the exception of a bump in the late 1990s). 3

Earnings have been increasing modestly over the past decade for these groups.

- Young men with a high school education who are working full time, full year have median earnings of $45,000 today, up from $39,300 in 2014. (All figures are in 2022 dollars.)

- The median earnings of young men with some college education who are working full time, full year are $50,000 today, similar to their median earnings in 2014 ($49,100).

It’s important to note that median annual earnings for both groups of noncollege men remain below their 1973 levels.

Median earnings for young men with a four-year college degree have increased over the past 10 years, from $67,500 in 2014 to $77,000 today.

Unlike young men without a college degree, the earnings of college-educated young men are now above what they were in the early 1970s. The gap in median earnings between young men with and without a college degree grew significantly from the late 1970s to 2014. In 1973, the typical young man with a degree earned 23% more than his high school-educated counterpart. By 2014, it was 72% more. Today, that gap stands at 71%. 4

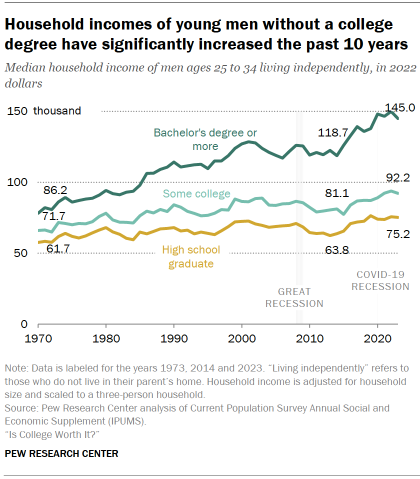

Household income has also trended up for young men in the past 10 years, regardless of educational attainment.

This measure takes into account the contributions of everyone in the household. For this analysis, we excluded young men who are living in their parents’ home (about 20% of 25- to 34-year-old men in 2023).

- The median household income of young men with a high school education is $75,200 today, up from $63,800 in 2014. This is slightly lower than the highpoint reached around 2019.

- The median household income of young men with some college education is $92,200 today, up from $81,100 in 2014. This is close to the 2022 peak of $93,800.

The median household income of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree has also increased from a low point of $118,700 in 2014 after the Great Recession to $145,000 today.

The gap in household income between young men with and without a college degree grew significantly between 1980 and 2014. In 1980, the median household income of young men with at least a bachelor’s degree was about 38% more than that of high school graduates. By 2014, that gap had widened to 86%.

Over the past 10 years, the income gap has fluctuated. In 2023, the typical college graduate’s household income was 93% more than that of the typical high school graduate.

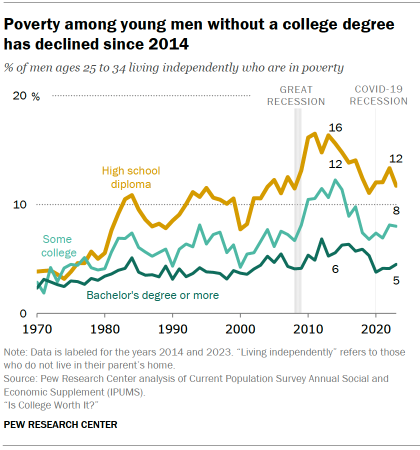

The 2001 recession and Great Recession resulted in a large increase in poverty among young men without a college degree.

- In 2000, among young men living independently of their parents, 8% of those with a high school education were in poverty. Poverty peaked for this group at 17% around 2011 and has since declined to 12% in 2023.

- Among young men with some college education, poverty peaked at 12% around 2014, up from 4% in 2000. Poverty has fallen for this group since 2014 and stands at 8% as of 2023.

- Young men with a four-year college degree also experienced a slight uptick in poverty during the 2001 recession and Great Recession. In 2014, 6% of young college graduates were in poverty, up from 4% in 2000. Poverty among college graduates stands at 5% in 2023.

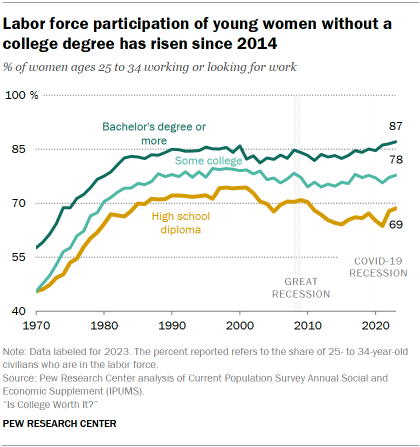

Labor force trends for young women are very different than for young men. There are occupational and educational differences between young women and men, and their earnings have followed different patterns.

Unlike the long-running decline for noncollege young men, young women without a college degree saw their labor force participation increase steadily from 1970 to about 1990.

By 2000, about three-quarters of young women with a high school diploma and 79% of those with some college education were in the labor force.

Labor force participation has also trended upward for college-educated young women and has consistently been higher than for those with less education.

After rising for decades, labor force participation for young women without a college degree fell during the 2001 recession and the Great Recession. Their labor force participation has increased slightly since 2014.

As of 2023, 69% of young women with a high school education were in the labor force, as were 78% of young women with some college education. Today’s level of labor force participation for young women without a college degree is slightly lower than the level seen around 2000.

The decline in labor force participation for noncollege women partly reflects the declining labor force participation for mothers with children under 18 years of age . Other research has suggested that without federal paid parental and family leave benefits for parents, some women with less education may leave the labor force after having a baby.

In contrast, labor force participation for young women with a college degree has fully recovered from the recessions of the early 2000s. Today, 87% of college-educated young women are in the labor force, the highest estimate on record.

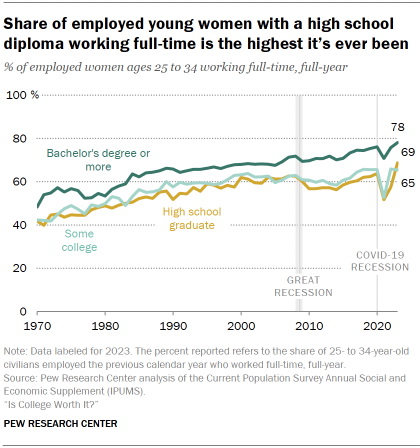

Young women without a college degree have steadily increased their work hours over the decades. The past 10 years in particular have seen a significant increase in the share of employed noncollege women working full time, full year (with the exception of 2021).

- In 2023, 69% of employed young women with a high school education worked full time, full year, up from 56% in 2014. This share is the highest it’s ever been.

- In 2023, 65% of employed women with some college worked full time, full year, up from 58% in 2014. This is among the highest levels ever.

The trend in the share working full time, full year has been similar for young women with college degrees. By 2023, 78% of these women worked full time, full year, the highest share it’s ever been.

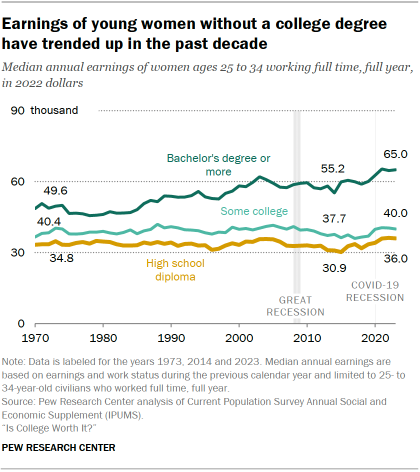

Unlike young men, young women without a college education did not see their earnings fall between 1970 and 2000.

The 2001 recession and Great Recession also did not significantly impact the earnings of noncollege young women. In the past 10 years, their median earnings have trended upward.

- For young women with a high school diploma, median earnings reached $36,000 in 2023, up from $30,900 in 2014.

- For those with some college, median earnings rose to $40,000 in 2023 from $37,700 in 2014.

For young women with a college degree, median earnings rose steadily from the mid-1980s until the early 2000s. By 2003, they reached $62,100, but this declined to $55,200 by 2014. In the past 10 years, the median earnings of college-educated young women have risen, reaching $65,000 in 2023.

In the mid-1980s, the typical young woman with a college degree earned about 48% more than her counterpart with a high school diploma. The pay gap among women has widened since then, and by 2014, the typical college graduate earned 79% more than the typical high school graduate. The gap has changed little over the past 10 years.

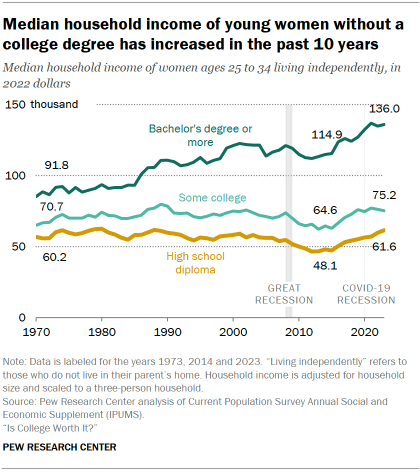

Noncollege young women living independently from their parents have experienced large household income gains over the past 10 years, measured at the median.

- In 2023, young women with a high school diploma had a median household income of $61,600, up from $48,100 in 2014.

- The pattern is similar for young women with some college education. Their median income rose to $75,200 in 2023 from $64,600 in 2014.

The median household income for young women with a four-year college degree is significantly higher than it is for their counterparts without a degree. College-educated young women have made substantial gains in the past 10 years.

The income gap between young women with and without a college degree has widened over the decades. In 1980, the median household income of young women with a college degree was 50% higher than that of high school-educated women. By 2014, the income gap had grown to 139%. Today, the household income advantage of college-educated women stands at 121% ($136,000 vs. $61,600).

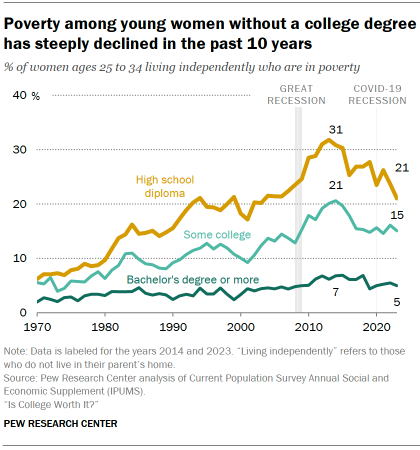

Poverty trends for young women mirror those for young men, although young women are overall more likely to be in poverty than young men. The past 10 years have resulted in a steep reduction in the share of noncollege women in poverty.

- Today, 21% of young women with a high school diploma are living in poverty. This is down from 31% in 2014.

- 15% of young women with some college education live in poverty, compared with 21% in 2014.

- Young women with a college degree are consistently far less likely than either group to be living in poverty (5% in 2023).

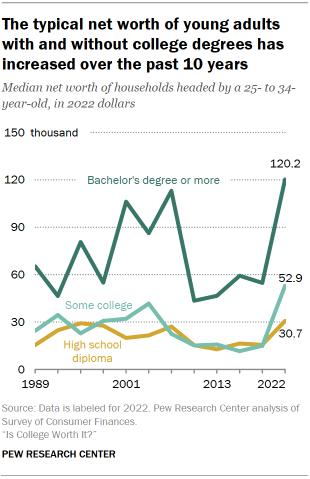

Along with young adults’ rising incomes over the past 10 years, there’s been a substantial increase in their wealth. This part of our analysis does not look at men and women separately due to limitations in sample size.

In 2022, households headed by a young high school graduate had a median net worth of $30,700, up from $12,700 in 2013. Those headed by a young adult with some college education had a median net worth of $52,900, up from $15,700 in 2013.

The typical wealth level of households headed by a young college graduate was $120,200 in 2022, up from $46,600 in 2013.

There has not been any significant narrowing of the wealth gap between young high school graduate and young college graduate households since 2013.

Wealth increased for Americans across age groups over this period due to several factors. Many were able to save money during the pandemic lockdowns. In addition, home values increased, and the stock market surged.

- Most of the analysis in this chapter is based on the Annual Social and Economic Supplement collected by the U.S. Census Bureau. Information on net worth is based on a Federal Reserve survey, which interviews fewer households. Due to this smaller sample size, the net worth of households headed by a young adult cannot be broken out by gender and education. ↩

- Bureau of Labor Statistics data indicates that the labor force participation rate for men ages 25 to 54 has been declining since 1953. ↩

- This analysis looks at the earnings of employed adults working full time, full year. This measure of earnings is not uncommon. For example, the National Center for Education Statistics publishes a series on the annual earnings of 25- to 34-year-olds working full time, full year. ↩

- Other studies using hourly wages rather than annual earnings find that the college wage premium has narrowed. For example, researchers at the San Francisco Federal Reserve report that the college wage gap peaked in the mid-2010s but declined by just 4 percentage points to about 75% in 2022. ↩

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Business & Workplace

- Economic Conditions

- Higher Education

- Income & Wages

- Recessions & Recoveries

- Student Loans

Half of Latinas Say Hispanic Women’s Situation Has Improved in the Past Decade and Expect More Gains

From businesses and banks to colleges and churches: americans’ views of u.s. institutions, fewer young men are in college, especially at 4-year schools, key facts about u.s. latinos with graduate degrees, private, selective colleges are most likely to use race, ethnicity as a factor in admissions decisions, most popular, report materials.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Over recent months, tech companies have been laying workers off by the thousands. It is estimated that in 2022 alone, over 120,000 people have been dismissed from their job at some of the biggest players in tech – Meta , Amazon , Netflix , and soon Google – and smaller firms and starts ups as well. Announcements of cuts keep coming.

Recent layoffs across the tech sector are an example of “social contagion” – companies are laying off workers because everyone is doing it, says Stanford business Professor Jeffrey Pfeffer. (Image credit: Courtesy Jeffrey Pfeffer)

What explains why so many companies are laying large numbers of their workforce off? The answer is simple: copycat behavior, according to Jeffrey Pfeffer, a professor at the Stanford Graduate School of Business .

Here, Stanford News talks to Pfeffer about how the workforce reductions that are happening across the tech industry are a result mostly of “social contagion”: Behavior spreads through a network as companies almost mindlessly copy what others are doing. When a few firms fire staff, others will probably follow suit. Most problematic, it’s a behavior that kills people : For example, research has shown that layoffs can increase the odds of suicide by two times or more .

Moreover, layoffs don’t work to improve company performance, Pfeffer adds. Academic studies have shown that time and time again, workplace reductions don’t do much for paring costs. Severance packages cost money, layoffs increase unemployment insurance rates, and cuts reduce workplace morale and productivity as remaining employees are left wondering, “Could I be fired too?”

For over four decades, Pfeffer, the Thomas D. Dee II Professor of Organizational Behavior, has studied hiring and firing practices in companies across the world. He’s met with business leaders at some of the country’s top companies and their employees to learn what makes – and doesn’t make – effective, evidence-based management. His recent book Dying for a Paycheck: How Modern Management Harms Employee Health and Company Performance–And What We Can Do About It (Harper Business, 2018) looks at how management practices, including layoffs, are hurting, and in some cases, killing workers.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why are so many tech companies laying people off right now?

The tech industry layoffs are basically an instance of social contagion, in which companies imitate what others are doing. If you look for reasons for why companies do layoffs, the reason is that everybody else is doing it. Layoffs are the result of imitative behavior and are not particularly evidence-based.

I’ve had people say to me that they know layoffs are harmful to company well-being, let alone the well-being of employees, and don’t accomplish much, but everybody is doing layoffs and their board is asking why they aren’t doing layoffs also.

Do you think layoffs in tech are some indication of a tech bubble bursting or the company preparing for a recession?

Could there be a tech recession? Yes. Was there a bubble in valuations? Absolutely. Did Meta overhire? Probably. But is that why they are laying people off? Of course not. Meta has plenty of money. These companies are all making money. They are doing it because other companies are doing it.

What are some myths or misunderstandings about layoffs?

Layoffs often do not cut costs, as there are many instances of laid-off employees being hired back as contractors, with companies paying the contracting firm. Layoffs often do not increase stock prices, in part because layoffs can signal that a company is having difficulty. Layoffs do not increase productivity. Layoffs do not solve what is often the underlying problem, which is often an ineffective strategy, a loss of market share, or too little revenue. Layoffs are basically a bad decision.

Companies sometimes lay off people that they have just recruited – oftentimes with paid recruitment bonuses. When the economy turns back in the next 12, 14, or 18 months, they will go back to the market and compete with the same companies to hire talent. They are basically buying labor at a high price and selling low. Not the best decision.

People don’t pay attention to the evidence against layoffs. The evidence is pretty extensive, some of it is reviewed in the book I wrote on human resource management, The Human Equation: Building Profits by Putting People First. If companies paid attention to the evidence, they could get some competitive leverage because they would actually be basing their decisions on science.

You’ve written about the negative health effects of layoffs. Can you talk about some of the research on this topic by you and others?

Layoffs kill people, literally . They kill people in a number of ways. Layoffs increase the odds of suicide by two and a half times. This is also true outside of the United States, even in countries with better social safety nets than the U.S., like New Zealand.

Layoffs increase mortality by 15-20% over the following 20 years.

There are also health and attitudinal consequences for managers who are laying people off as well as for the employees who remain . Not surprisingly, layoffs increase people’s stress . Stress, like many attitudes and emotions, is contagious. Depression is contagious , and layoffs increase stress and depression, which are bad for health.

Unhealthy stress leads to a variety of behaviors such as smoking and drinking more , drug taking , and overeating . Stress is also related to addiction , and layoffs of course increase stress.

What was your reaction to some of the recent headlines of mass layoffs, like Meta laying off 11,000 employees?

I am concerned. Most of my recent research is focused on the effect of the workplace on human health and how economic insecurity is bad for people. This is on the heels of the COVID pandemic and the social isolation resulting from that, which was also bad for people.

We ought to place a higher priority on human life.

If layoffs are contagious within an industry, could it then spread across industries, leading to other sectors cutting staff?

Of course, it already has. Layoffs are contagious across industries and within industries. The logic driving this, which doesn’t sound like very sensible logic because it’s not, is people say, “Everybody else is doing it, why aren’t we?”

Retailers are pre-emptively laying off staff, even as final demand remains uncertain. Apparently, many organizations will trade off a worse customer experience for reduced staffing costs, not taking into account the well-established finding that is typically much more expensive to attract new customers than it is to keep existing ones happy.

Are there past examples of contagious layoffs like the one we are seeing now, and what lessons were learned?

After the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, every airline except Southwest did layoffs. By the end of that year, Southwest, which did not do any layoffs, gained market share. A.G. Lafley, who was the former CEO of Procter and Gamble, said the best time to gain ground on your competition is when they are in retreat – when they are cutting their services, when they are cutting their product innovation because they have laid people off. James Goodnight, the CEO of the software company SAS Institute, has also never done layoffs – he actually hired during the last two recessions because he said it’s the best time to pick up talent.

Any advice to workers who may have been laid off?

My advice to a worker who has been laid off is when they find a job in a company where they say people are their most important asset, they actually check to be sure that the company behaves consistently with that espoused value when times are tough.

If layoffs don’t work, what is a better solution for companies that want to mitigate the problems they believe layoffs will address?

One thing that Lincoln Electric, which is a famous manufacturer of arc welding equipment, did well is instead of laying off 10% of their workforce, they had everybody take a 10% wage cut except for senior management, which took a larger cut. So instead of giving 100% of the pain to 10% of the people, they give 100% of the people 10% of the pain.

Companies could use economic stringency as an opportunity, as Goodnight at the SAS Institute did in the 2008 recession and in the 2000 tech recession. He used the downturn to upgrade workforce skills as competitors eliminated jobs, thereby putting talent on the street. He actually hired during the 2000 recession and saw it as an opportunity to gain ground on the competition and gain market share when everybody was cutting jobs and stopped innovating. And it is [an opportunity]. Social media is not going away. Artificial intelligence, statistical software, and web services industries – none of these things are going to disappear.

A new future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills in Europe and beyond

At a glance.

Amid tightening labor markets and a slowdown in productivity growth, Europe and the United States face shifts in labor demand, spurred by AI and automation. Our updated modeling of the future of work finds that demand for workers in STEM-related, healthcare, and other high-skill professions would rise, while demand for occupations such as office workers, production workers, and customer service representatives would decline. By 2030, in a midpoint adoption scenario, up to 30 percent of current hours worked could be automated, accelerated by generative AI (gen AI). Efforts to achieve net-zero emissions, an aging workforce, and growth in e-commerce, as well as infrastructure and technology spending and overall economic growth, could also shift employment demand.

By 2030, Europe could require up to 12 million occupational transitions, double the prepandemic pace. In the United States, required transitions could reach almost 12 million, in line with the prepandemic norm. Both regions navigated even higher levels of labor market shifts at the height of the COVID-19 period, suggesting that they can handle this scale of future job transitions. The pace of occupational change is broadly similar among countries in Europe, although the specific mix reflects their economic variations.

Businesses will need a major skills upgrade. Demand for technological and social and emotional skills could rise as demand for physical and manual and higher cognitive skills stabilizes. Surveyed executives in Europe and the United States expressed a need not only for advanced IT and data analytics but also for critical thinking, creativity, and teaching and training—skills they report as currently being in short supply. Companies plan to focus on retraining workers, more than hiring or subcontracting, to meet skill needs.

Workers with lower wages face challenges of redeployment as demand reweights toward occupations with higher wages in both Europe and the United States. Occupations with lower wages are likely to see reductions in demand, and workers will need to acquire new skills to transition to better-paying work. If that doesn’t happen, there is a risk of a more polarized labor market, with more higher-wage jobs than workers and too many workers for existing lower-wage jobs.

Choices made today could revive productivity growth while creating better societal outcomes. Embracing the path of accelerated technology adoption with proactive worker redeployment could help Europe achieve an annual productivity growth rate of up to 3 percent through 2030. However, slow adoption would limit that to 0.3 percent, closer to today’s level of productivity growth in Western Europe. Slow worker redeployment would leave millions unable to participate productively in the future of work.

Demand will change for a range of occupations through 2030, including growth in STEM- and healthcare-related occupations, among others

This report focuses on labor markets in nine major economies in the European Union along with the United Kingdom, in comparison with the United States. Technology, including most recently the rise of gen AI, along with other factors, will spur changes in the pattern of labor demand through 2030. Our study, which uses an updated version of the McKinsey Global Institute future of work model, seeks to quantify the occupational transitions that will be required and the changing nature of demand for different types of jobs and skills.

Our methodology

We used methodology consistent with other McKinsey Global Institute reports on the future of work to model trends of job changes at the level of occupations, activities, and skills. For this report, we focused our analysis on the 2022–30 period.

Our model estimates net changes in employment demand by sector and occupation; we also estimate occupational transitions, or the net number of workers that need to change in each type of occupation, based on which occupations face declining demand by 2030 relative to current employment in 2022. We included ten countries in Europe: nine EU members—the Czech Republic, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Netherlands, Poland, Spain, and Sweden—and the United Kingdom. For the United States, we build on estimates published in our 2023 report Generative AI and the future of work in America.

We included multiple drivers in our modeling: automation potential, net-zero transition, e-commerce growth, remote work adoption, increases in income, aging populations, technology investments, and infrastructure investments.

Two scenarios are used to bookend the work-automation model: “late” and “early.” For Europe, we modeled a “faster” scenario and a “slower” one. For the faster scenario, we use the midpoint—the arithmetical average between our late and early scenarios. For the slower scenario, we use a “mid late” trajectory, an arithmetical average between a late adoption scenario and the midpoint scenario. For the United States, we use the midpoint scenario, based on our earlier research.

We also estimate the productivity effects of automation, using GDP per full-time-equivalent (FTE) employee as the measure of productivity. We assumed that workers displaced by automation rejoin the workforce at 2022 productivity levels, net of automation, and in line with the expected 2030 occupational mix.

Amid tightening labor markets and a slowdown in productivity growth, Europe and the United States face shifts in labor demand, spurred not only by AI and automation but also by other trends, including efforts to achieve net-zero emissions, an aging population, infrastructure spending, technology investments, and growth in e-commerce, among others (see sidebar, “Our methodology”).

Our analysis finds that demand for occupations such as health professionals and other STEM-related professionals would grow by 17 to 30 percent between 2022 and 2030, (Exhibit 1).

By contrast, demand for workers in food services, production work, customer services, sales, and office support—all of which declined over the 2012–22 period—would continue to decline until 2030. These jobs involve a high share of repetitive tasks, data collection, and elementary data processing—all activities that automated systems can handle efficiently.

Up to 30 percent of hours worked could be automated by 2030, boosted by gen AI, leading to millions of required occupational transitions

By 2030, our analysis finds that about 27 percent of current hours worked in Europe and 30 percent of hours worked in the United States could be automated, accelerated by gen AI. Our model suggests that roughly 20 percent of hours worked could still be automated even without gen AI, implying a significant acceleration.

These trends will play out in labor markets in the form of workers needing to change occupations. By 2030, under the faster adoption scenario we modeled, Europe could require up to 12.0 million occupational transitions, affecting 6.5 percent of current employment. That is double the prepandemic pace (Exhibit 2). Under a slower scenario we modeled for Europe, the number of occupational transitions needed would amount to 8.5 million, affecting 4.6 percent of current employment. In the United States, required transitions could reach almost 12.0 million, affecting 7.5 percent of current employment. Unlike Europe, this magnitude of transitions is broadly in line with the prepandemic norm.

Both regions navigated even higher levels of labor market shifts at the height of the COVID-19 period. While these were abrupt and painful to many, given the forced nature of the shifts, the experience suggests that both regions have the ability to handle this scale of future job transitions.

Businesses will need a major skills upgrade

The occupational transitions noted above herald substantial shifts in workforce skills in a future in which automation and AI are integrated into the workplace (Exhibit 3). Workers use multiple skills to perform a given task, but for the purposes of our quantification, we identified the predominant skill used.

Demand for technological skills could see substantial growth in Europe and in the United States (increases of 25 percent and 29 percent, respectively, in hours worked by 2030 compared to 2022) under our midpoint scenario of automation adoption (which is the faster scenario for Europe).

Demand for social and emotional skills could rise by 11 percent in Europe and by 14 percent in the United States. Underlying this increase is higher demand for roles requiring interpersonal empathy and leadership skills. These skills are crucial in healthcare and managerial roles in an evolving economy that demands greater adaptability and flexibility.

Conversely, demand for work in which basic cognitive skills predominate is expected to decline by 14 percent. Basic cognitive skills are required primarily in office support or customer service roles, which are highly susceptible to being automated by AI. Among work characterized by these basic cognitive skills experiencing significant drops in demand are basic data processing and literacy, numeracy, and communication.

Demand for work in which higher cognitive skills predominate could also decline slightly, according to our analysis. While creativity is expected to remain highly sought after, with a potential increase of 12 percent by 2030, work activities characterized by other advanced cognitive skills such as advanced literacy and writing, along with quantitative and statistical skills, could decline by 19 percent.

Demand for physical and manual skills, on the other hand, could remain roughly level with the present. These skills remain the largest share of workforce skills, representing about 30 percent of total hours worked in 2022. Growth in demand for these skills between 2022 and 2030 could come from the build-out of infrastructure and higher investment in low-emissions sectors, while declines would be in line with continued automation in production work.

Business executives report skills shortages today and expect them to worsen

A survey we conducted of C-suite executives in five countries shows that companies are already grappling with skills challenges, including a skills mismatch, particularly in technological, higher cognitive, and social and emotional skills: about one-third of the more than 1,100 respondents report a shortfall in these critical areas. At the same time, a notable number of executives say they have enough employees with basic cognitive skills and, to a lesser extent, physical and manual skills.

Within technological skills, companies in our survey reported that their most significant shortages are in advanced IT skills and programming, advanced data analysis, and mathematical skills. Among higher cognitive skills, significant shortfalls are seen in critical thinking and problem structuring and in complex information processing. About 40 percent of the executives surveyed pointed to a shortage of workers with these skills, which are needed for working alongside new technologies (Exhibit 4).

Companies see retraining as key to acquiring needed skills and adapting to the new work landscape

Surveyed executives expect significant changes to their workforce skill levels and worry about not finding the right skills by 2030. More than one in four survey respondents said that failing to capture the needed skills could directly harm financial performance and indirectly impede their efforts to leverage the value from AI.

To acquire the skills they need, companies have three main options: retraining, hiring, and contracting workers. Our survey suggests that executives are looking at all three options, with retraining the most widely reported tactic planned to address the skills mismatch: on average, out of companies that mentioned retraining as one of their tactics to address skills mismatch, executives said they would retrain 32 percent of their workforce. The scale of retraining needs varies in degree. For example, respondents in the automotive industry expect 36 percent of their workforce to be retrained, compared with 28 percent in the financial services industry. Out of those who have mentioned hiring or contracting as their tactics to address the skills mismatch, executives surveyed said they would hire an average of 23 percent of their workforce and contract an average of 18 percent.

Occupational transitions will affect high-, medium-, and low-wage workers differently

All ten European countries we examined for this report may see increasing demand for top-earning occupations. By contrast, workers in the two lowest-wage-bracket occupations could be three to five times more likely to have to change occupations compared to the top wage earners, our analysis finds. The disparity is much higher in the United States, where workers in the two lowest-wage-bracket occupations are up to 14 times more likely to face occupational shifts than the highest earners. In Europe, the middle-wage population could be twice as affected by occupational transitions as the same population in United States, representing 7.3 percent of the working population who might face occupational transitions.

Enhancing human capital at the same time as deploying the technology rapidly could boost annual productivity growth

About quantumblack, ai by mckinsey.

QuantumBlack, McKinsey’s AI arm, helps companies transform using the power of technology, technical expertise, and industry experts. With thousands of practitioners at QuantumBlack (data engineers, data scientists, product managers, designers, and software engineers) and McKinsey (industry and domain experts), we are working to solve the world’s most important AI challenges. QuantumBlack Labs is our center of technology development and client innovation, which has been driving cutting-edge advancements and developments in AI through locations across the globe.

Organizations and policy makers have choices to make; the way they approach AI and automation, along with human capital augmentation, will affect economic and societal outcomes.

We have attempted to quantify at a high level the potential effects of different stances to AI deployment on productivity in Europe. Our analysis considers two dimensions. The first is the adoption rate of AI and automation technologies. We consider the faster scenario and the late scenario for technology adoption. Faster adoption would unlock greater productivity growth potential but also, potentially, more short-term labor disruption than the late scenario.

The second dimension we consider is the level of automated worker time that is redeployed into the economy. This represents the ability to redeploy the time gained by automation and productivity gains (for example, new tasks and job creation). This could vary depending on the success of worker training programs and strategies to match demand and supply in labor markets.

We based our analysis on two potential scenarios: either all displaced workers would be able to fully rejoin the economy at a similar productivity level as in 2022 or only some 80 percent of the automated workers’ time will be redeployed into the economy.

Exhibit 5 illustrates the various outcomes in terms of annual productivity growth rate. The top-right quadrant illustrates the highest economy-wide productivity, with an annual productivity growth rate of up to 3.1 percent. It requires fast adoption of technologies as well as full redeployment of displaced workers. The top-left quadrant also demonstrates technology adoption on a fast trajectory and shows a relatively high productivity growth rate (up to 2.5 percent). However, about 6.0 percent of total hours worked (equivalent to 10.2 million people not working) would not be redeployed in the economy. Finally, the two bottom quadrants depict the failure to adopt AI and automation, leading to limited productivity gains and translating into limited labor market disruptions.

Four priorities for companies

The adoption of automation technologies will be decisive in protecting businesses’ competitive advantage in an automation and AI era. To ensure successful deployment at a company level, business leaders can embrace four priorities.

Understand the potential. Leaders need to understand the potential of these technologies, notably including how AI and gen AI can augment and automate work. This includes estimating both the total capacity that these technologies could free up and their impact on role composition and skills requirements. Understanding this allows business leaders to frame their end-to-end strategy and adoption goals with regard to these technologies.

Plan a strategic workforce shift. Once they understand the potential of automation technologies, leaders need to plan the company’s shift toward readiness for the automation and AI era. This requires sizing the workforce and skill needs, based on strategically identified use cases, to assess the potential future talent gap. From this analysis will flow details about the extent of recruitment of new talent, upskilling, or reskilling of the current workforce that is needed, as well as where to redeploy freed capacity to more value-added tasks.

Prioritize people development. To ensure that the right talent is on hand to sustain the company strategy during all transformation phases, leaders could consider strengthening their capabilities to identify, attract, and recruit future AI and gen AI leaders in a tight market. They will also likely need to accelerate the building of AI and gen AI capabilities in the workforce. Nontechnical talent will also need training to adapt to the changing skills environment. Finally, leaders could deploy an HR strategy and operating model to fit the post–gen AI workforce.

Pursue the executive-education journey on automation technologies. Leaders also need to undertake their own education journey on automation technologies to maximize their contributions to their companies during the coming transformation. This includes empowering senior managers to explore automation technologies implications and subsequently role model to others, as well as bringing all company leaders together to create a dedicated road map to drive business and employee value.

AI and the toolbox of advanced new technologies are evolving at a breathtaking pace. For companies and policy makers, these technologies are highly compelling because they promise a range of benefits, including higher productivity, which could lift growth and prosperity. Yet, as this report has sought to illustrate, making full use of the advantages on offer will also require paying attention to the critical element of human capital. In the best-case scenario, workers’ skills will develop and adapt to new technological challenges. Achieving this goal in our new technological age will be highly challenging—but the benefits will be great.

Eric Hazan is a McKinsey senior partner based in Paris; Anu Madgavkar and Michael Chui are McKinsey Global Institute partners based in New Jersey and San Francisco, respectively; Sven Smit is chair of the McKinsey Global Institute and a McKinsey senior partner based in Amsterdam; Dana Maor is a McKinsey senior partner based in Tel Aviv; Gurneet Singh Dandona is an associate partner and a senior expert based in New York; and Roland Huyghues-Despointes is a consultant based in Paris.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Generative AI and the future of work in America

The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier

What every CEO should know about generative AI

Articles on Social media Africa

Displaying all articles.

TikTok activism: how queer Zimbabweans use social media to show love and fight hate

Gibson Ncube , Stellenbosch University and Princess Sibanda , University of Fort Hare

Democracy in Africa: digital voting technology and social media can be a force for good – and bad

Maxwell Maseko , University of the Witwatersrand

TikTok in Kenya: the government wants to restrict it, but my study shows it can be useful and empowering

Stephen Mutie , Kenyatta University

Science journalism in South Africa: social media is helping connect with new readers

Sisanda Nkoala , University of the Western Cape

Social media content in times of war: an expert guide on how to keep violence off your feeds

Megan Knight , University of Hertfordshire

Looking for work? 3 tips on how social media can help young South Africans

Willie Tafadzwa Chinyamurindi , University of Fort Hare ; Liezel Cilliers , University of Fort Hare , and Obrain Tinashe Murire , Walter Sisulu University

Ghana school students talk about their social media addiction, and how it affects their use of English

Ramos Asafo-Adjei , Takoradi Technical University

Algorithms, bots and elections in Africa: how social media influences political choices

Martin N Ndlela , Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences

Social media could help Lagos police officers fight crime: why it’s not happening

Usman A. Ojedokun , University of Ibadan

Related Topics

- African social media

- Disinformation

- Misinformation

- Peacebuilding

- Social media

- X (formerly Twitter)

Top contributors

Associate professor, University of the Western Cape

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The British Journal of Social Work

- About the British Association of Social Workers

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, why the ref matters, the process of assessment, social work and social policy: uoa20 results, the research landscape, research impact, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Social Work Research in the UK: A View through the Lens of REF2021

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Nicky Stanley, Elaine Sharland, Luke Geoghegan, Ravinder Barn, Alisoun Milne, Judith Phillips, Kirby Swales, Social Work Research in the UK: A View through the Lens of REF2021, The British Journal of Social Work , Volume 53, Issue 8, December 2023, Pages 3546–3565, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcad116

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The Research Assessment Exercise was introduced in 1986 to measure research quality and to determine the allocation of higher education funding. The renamed Research Excellence Framework (REF) has become an important barometer of research capacity and calibre across academic disciplines in UK universities. Based on the expert insights of REF sub-panel members for Unit of Assessment 20 (UOA20), Social Work and Social Policy, this article contributes to understanding of the current state of UK social work research. It documents the process of research quality assessment and reports on the current social work research landscape, including impact. Given its growing vigour, increased engagement with theory and conceptual frameworks, policy and practice and its methodological diversity, it is evident that social work research has achieved considerable consolidation and growth in its activity and knowledge base. Whilst Russell Group and older universities cluster at the top of the REF rankings, this cannot be taken for granted as some newer institutions performed well in REF2021. The article argues that the discipline’s embeddedness in interdisciplinary research, its quest for social justice and its applied nature align well with the REF framework where interdisciplinarity, equality, diversity and inclusion and impact constitute core principles.

The Research Excellence Framework (REF) has significant implications for the quality and vitality of UK research, for academic disciplines, universities, university departments, future research funding and academic careers. The REF usually takes place every six years; the previous exercise was completed in 2014, but REF2021 did not report until June 2022 following delays caused by the pandemic. The assessment process is delivered through panels and sub-panels which take responsibility for Units of Assessment (UOAs). UOA20 covered Social Work and Social Policy and included some, but not all, research in Criminology. Units submitting to the REF were assessed on quality of research outputs, impact (research-generated effects, or benefits beyond academia, demonstrated by case studies) and environment (demonstrated by environment statements and additional data).

Universities and their staff commit significant energy and resources to the REF process and, with the shift to assessing impact introduced for REF2014, social work organisations and policy makers also contribute by providing information and supporting statements to evidence impact. It is therefore essential that all opportunities for learning offered by the REF exercise are captured.

This article has been produced by both academic and impact assessors who served on Sub-panel 20 for REF2021, with the aim of disseminating and reflecting on the picture of social work research and impact provided by REF assessment. We acknowledge that UOA20 does not capture all social work research produced in the UK: numerous research outputs are not submitted for REF assessment and some universities take the strategic decision to return their social work research to another UOA such as Allied Health Professions (UOA3) or Sociology (UOA21). Members of Sub-panel 20 encountered challenges in distinguishing social work from social policy and criminology research: much of the work assessed was interdisciplinary and, for many outputs, disciplinary boundaries appeared porous. Nevertheless, opportunities for painting a picture of social work research across the UK are rare and this account benefits from the fact that some social work assessors contributed to the work of the sub-panel in both 2014 and 2021, enabling us to comment on change and growth.

Research England, part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) which provides government funding for research, managed the REF process and acted on behalf of the Scottish Funding Council, the Higher Education Council for Wales and the Department for the Economy in Northern Ireland. Formal REF outputs include reports to universities and their departments, ratings tables which are broken down by UOA and by institution, and panel reports which include overviews of the work of individual sub-panels [see REF2021 (2022b) for Sub-panel 20’s overview report]. The REF has strong governance processes so, whilst other organisations may use REF data to produce their own material (e.g. university marketing campaigns or university ‘league tables’ published in the national press) these are not endorsed by the REF. This article represents the views of social work assessors who served on Sub-panel 20; our comments should not be attributed to UKRI or the chairs of Sub-panel 20 or Main Panel C. We offer ‘high-level’ conclusions about the assessment process and the broad profile of social work research and impact that the REF provides. We do not comment on specific outputs, researchers or institutions.

We begin by considering the implications of the REF for universities, their staff and for society more broadly. We then move to explaining the REF process, in particular the workings of Sub-panel 20. We provide accounts of social work research and impact as viewed through the lens of the REF before reaching some conclusions. Discussion of research environment, the third element of REF assessment, is woven through. Each academic assessor on Sub-panel 20 reviewed only the outputs allocated to themself; none saw the full array. Whilst we have been able to draw on Sub-panel 20’s published overview report (REF2021, 2022), REF rules required us to destroy all notes and records. Instead, we have engaged in iterative consultation with all seven social work academic assessors on Sub-panel 20, eliciting their responses to a questionnaire and their comments on successive drafts of this article. This dialogical process has enabled us to paint a rich picture of social work research submitted to Sub-panel 20. Since REF impact case studies, and impact scores for each UOA submission, are in the public domain ( REF2021, 2022a ), we have been able to return directly to these to inform this account.

The REF is a long-established feature of university life in the UK. Whilst Hong Kong, Australia, New Zealand and Italy have adopted similar systems for appraising university research, the model is not found in all jurisdictions. Notwithstanding its critics, the REF is widely regarded as a barometer of the health and quality of UK research and a great deal of work goes into preparing submissions. Universities use REF results to market teaching programmes, impress funders, boost staff morale and attract new staff and students. University websites are replete with REF-related quotes on impact, research quality and international and national league tables. The REF results impact on the reputations and status of universities, departments and individual academics.

REF results are used to determine the distribution of the UK Research Councils’ block grants known as quality-related (QR) funds (Research Excellence Grant in Scotland), which provide funding for university research over several years. Once announced, grants can inform universities’ strategic planning, as this funding stream is known and sustained, unlike much other research funding which is allocated through competitive bidding processes. In July 2022, following publication of the REF results, Research England announced that QR funding (in England) would rise from £1.789 billion in 2021–2022 to £1.974 billion in 2022–2023 and 2023–2024, an increase of 10.4 per cent ( University Business, 2022 ). The distribution formula remains unchanged; those who have done proportionally better in REF have received a greater proportion of funding. Where growth has increased, for example in North-East England, universities have benefited ( Coe and Kernohan, 2022 ).

The implications of additional research funding are significant. Research councils and other funders can use REF outcomes as a benchmark of research quality. A key change since REF2014 is that UK access to European Union research funding is restricted following Brexit. Hence, QR funding’s contribution to the total research pot is now greater and may be relied on more heavily. Arguably, the REF process provides accountability for public investment, so that the benefits of university research can be demonstrated to funders and society as a whole. Along with other forms of audit, it creates a performance incentive for universities.

Within universities, REF results are used to inform institutional decisions on resource allocation. Departments that have improved their position in the league tables may expect to be rewarded, whilst departments whose ranking has fallen and who lack other sources of income (particularly teaching income) may be vulnerable to cuts. There are also implications for staff contracts. Following the Stern Review (2016) , in REF2021, all staff with ‘significant responsibility for research’ were entered for REF assessment, a rule change that resulted in 76,132 academics submitting at least one research output, compared with 52,000 in 2014.

Universities developed their own internal systems for assessing the quality of outputs well ahead of the REF submission deadline. In some institutions, staff with ‘significant responsibility’ for research but with outputs either scarce or judged internally to be of low quality may have been ‘invited to consider’ changing to ‘teaching only’ contracts in order to ensure a high-quality submission overall. The REF results do not specify the ratings allocated to individual researchers’ outputs, so offering protection for individual careers. For staff included in the REF, particularly those chosen to submit an impact case study, advantages may include opportunities for promotion or career advancement elsewhere.

The value of the REF is not uncontested. Some critics regard it as emblematic of an expanding audit culture ( Torrance, 2020 ) that ‘constructs an illusion of intellectual excellence and innovation whose true purpose is the neutralization of the university as a centre of independent knowledge creation and learning’ ( O’Regan and Gray, 2018 , p. 533). The University and Colleges Union ( UCU, 2022 ) considered the REF ‘a flawed, bureaucratic nightmare … a drain on the time and resources of university staff, and funding often entrenches structural inequalities’. Others are more qualified in their appraisals. Whilst also criticising the neoliberal underpinnings of the REF, MacDonald (2017) recognises that it can provide institutional space and incentive for impactful research for the public good. Manville et al. (2021) highlight the burden imposed by the REF, but report that over half the academics surveyed claimed it had not significantly influenced their own research. At the other end of the spectrum, Whitfield (2023) expresses confidence in the REF as a mechanism for ensuring accountability for government research funding which has strengthened the quality of UK research.

As suggested by the UCU, QR funding allocations may reinforce some existing inequalities between universities: wealthier institutions tend to perform well and so receive more QR funding. Russell Group (a self-selected group of twenty-four older and better-endowed universities) and older universities cluster at the top of the rankings. But this cannot be taken for granted and in social work and social policy, some newer institutions performed well in 2021.

For the world outside universities, the REF’s emphasis on impact and requirement to produce impact case studies has had the effect of strengthening communication and collaboration between university-based researchers and a wide range of partners from the practice and policy sectors. As an applied discipline, social work research has always maintained close links with research users, but the assessment of impact has sharpened researchers’ interest in how their research is disseminated, taken up and translated into social change. With research translation now a major preoccupation for academia, university research is increasingly likely to be engaging in ongoing dialogue with a variety of stakeholders and contributing to local, regional and national priorities.

UOA20 was one of twelve sub-panels that sat under REF2021’s Main Panel C which covered the social sciences. This structure allowed for planning, calibration and management of the task of assessing very large amounts of material to be carried out across disciplines, with the aim of achieving consistency and adherence to common practices and standards. Chairs were appointed to the REF panels and sub-panels following open advertisement and interviews and sub-panel members were nominated by learned bodies and other associations such as the Association of Professors of Social Work, Joint Social Work Education Council, the British Association of Social Work, the British Society of Gerontology and some of the major charities. Impact assessors and research users were similarly nominated and came from a range of practice, policy, research and knowledge transfer organisations. Sub-panel members were appointed in stages, allowing sub-panels to ensure they included a wide range of expertise and were sufficiently diverse and representative. The REF’s own analysis of appointments to all REF2021 sub-panels found significantly increased representativeness since 2014 ( REF2021/01, 2021 ). Sub-panel 20 included twenty-six academic assessors (eight of whom were predominantly social work academics), three research users, six impact assessors, one panel adviser and one panel secretary. Twenty-four sub-panel members (63 per cent) were women and fourteen (37 per cent) were men. Twenty-one per cent of the sub-panel were from Black and Minoritised ethnic communities. Institutions from each of the UK’s four nations were represented as were Russell Group and post-1992 universities (approximately seventy-eight institutions, mostly former polytechnics granted university status by the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act).

Sub-panel 20 met between November 2019 and March 2022. Restrictions imposed by the pandemic meant that most meetings were held online, but this did not seem to impede communication or decision-making. Planning and preparation started early and sub-panel members were able to contribute to developing guidance for submitting units—this was deliberately broad and inclusive reflecting the disciplines’ porous boundaries—planning workload management and working methods. All sub-panel members undertook unconscious bias training and participated in calibration exercises designed to ensure consistency in grading all components of submissions. In keeping with REF guidance ( REF2021a, 2019 ) regarding the reliability of citation data, especially in applied research fields, Sub-panel 20 made no use of bibliographic metrics to inform the assessment of outputs, relying solely on expert review. A grading process underpinned by assessor commentary was adopted with continuous monitoring of assessors’ rating patterns and particular attention given to borderline grades.

In total, seventy-six universities submitted research to sub-panel 20 – 15 more than in REF2014. Of these, 39.5 per cent were pre-1992 and 60.5 per cent were post-1992 universities. Fourteen institutions submitted to UOA20 for the first time, indicating expansion of research in these fields.

Likewise, the numbers of full-time equivalent (FTE) staff with significant responsibility for research who were returned to UOA20 increased by 61.8 per cent from REF2014. This growth is in part attributable to changes in REF procedures: REF2014 did not require all such staff to be submitted, whereas REF2021 did. However, it also indicates the vigour of the UOA20 disciplines. The sub-panel received a total of 5,158 outputs for review, an increase of 8 per cent from REF2014.

All outputs were reviewed by two assessors. One took responsibility for reviewing all outputs for an institution, so providing a full overview of that university’s unit of submission. The second was allocated on the basis of their expertise. A high number of interdisciplinary outputs was assessed and where expertise was felt to be lacking, in consultation with the sub-panel’s interdisciplinary adviser, outputs were cross-referred to appropriate sub-panels. Where gradings differed substantially, paired assessors discussed them and reached a joint decision. Very occasionally, a third assessor was brought in. The same approach was employed to assess impact case studies which were assessed jointly by an impact assessor and the academic assessor with responsibility for the submitting institution. Environment statements were assessed in larger groups of three including the allocated institutional assessor and two other panel members. The overall quality profile for each unit of submission to the REF2021 was calculated using a formula weighting of 60 per cent for outputs, 25 per cent for impact and 15 per cent for environment.

As noted above, it was not always easy to allocate outputs to one specific discipline. However, if the number of outputs allocated to a second assessor with social work expertise is used as a crude indicator of discipline, Sub-panel 20 assessed approximately 1,400 outputs for social work, 2,220 for social policy and 1,130 for criminology. Social work outputs therefore constituted approximately 30 per cent of the work assessed. In total, 225 impact case studies were assessed across all three disciplines, up from 190 in 2014. About one-third of these were predominantly social work, although this categorisation is very approximate since many were multidisciplinary.

Table 1 shows the final profiles for outputs, impact and environment across the whole UOA. As in REF2014, the UOA as a whole performed particularly well in respect of impact with over three-quarters of case studies rated 3* (internationally excellent) or 4* (world-leading). Similarly, three-quarters of the outputs assessed were rated 3* or 4*. Direct comparison between REF2021 and REF2014 results is difficult, due to changed rules regarding the ratio of outputs to returned FTE staff, and because REF2021 covered seven years (1 January 2014–31 December 2020) whilst REF2014 covered six years (January 2008–December 2013). Nonetheless, these results represent a slight improvement on those of REF2014. Of the 4,844 outputs submitted to the sub-panel, 577 (12 per cent) were attributed to early career researchers, signalling the continued growth and sustainability of the research community. Similarly, the environment statements submitted to Sub-panel 20 reported a 20.9 per cent increase in PhD completions over the REF period, as seen in Table 2 .

Quality profiles (FTE weighted) for UOA20, REF2021

Source : REF2021 (2022b , p. 126).

UoA20 all doctoral awards by academic year, REF2021

Source : REF2021 (2022b , p. 136).

Other indicators of growth found across the sub-panel included an average increase in universities’ social work and social policy research funding of £4.2 million per annum across the REF period.

Following changes in the REF guidance, the environment statements reported on equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) issues more fully than in REF2014. The stronger statements assessed provided detail on progress made since REF2014 regarding under-representation of staff with protected characteristics (i.e. age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex and sexual orientation as defined by the 2010 Equality Act).

Significant progress towards, or the achievement of, key EDI benchmarks was found in some cases, although this tended to be better evidenced for gender than ethnicity or other protected characteristics. However, there were some examples of positive practice in relation to research students: for instance, one institution had targeted PhD studentships on Black, Asian and Minoritised students.

The final ranking table for UOA20 was not dissimilar to that for REF2014, with the top end dominated by the better-resourced Russell Group and older universities. However, it was notable that more post-1992 institutions featured in the top thirty universities for social work and social policy than in 2014, indicating the increasing strength of some of these departments. As a group, institutions submitting to UOA20 for the first time produced a generally lower profile than the overall sub-panel profile: success in the REF is, to some extent, shaped by experience in and the resource devoted to crafting the submission. However, these new submissions displayed some key strengths and demonstrated expansion of the disciplines.

Turning to UK social work outputs submitted to Sub-panel 20, the overarching impression is that social work has continued to grow in maturity, sophistication and confidence as a research discipline and interdisciplinary field. Increased breadth and diversity were demonstrated in the range of contemporary issues explored and approaches taken. Assessors saw examples of outstanding excellence amongst outputs based on applied and empirical, conceptual and literature-based research. Where substantive themes or methodologies were familiar from REF2014, these were often treated with greater refinement and criticality. There were also strong signs that substantial funder investment can bear fruit in research of world-leading quality. Whilst centres of excellence in particular sub-fields produced some outstanding outputs, excellent research and 4* outputs were identified in all submitting units, including those newly submitting to the REF.

Output quality assessment

The three criteria used for appraising the quality of outputs were ‘originality, significance and rigour’ (see Box 1 ).

The overall quality of each output was judged according to the following starred level ratings:

Four star: quality that is world leading in terms of originality, significance and rigour.

Three star: quality that is internationally excellent in terms of originality, significance and rigour but which falls short of the highest standards of excellence.

Two star: quality that is recognised internationally in terms of originality, significance and rigour.

One star: quality that is recognised nationally in terms of originality, significance and rigour.

Unclassified: outputs that fall below the quality levels described above or do not meet the definition of research used for the REF.

Demonstrating research quality

Whilst claims to originality, significance and rigour were commonly flagged in outputs assessed, their validity needed to be demonstrated and not merely asserted. Originality was strongest where, for example, a new model was introduced for conceptualising or responding to a familiar social work issue or new questions explored in uncharted territory. It was less evident where a tried and tested approach was being replicated or there was significant overlap between outputs within the same submission. Significance could be both under-sold, commonly as an afterthought, or over-sold, say by drawing far-reaching implications from an exploratory study. Conversely, compelling significance could be demonstrated where clear contributions to knowledge, implications for law, policy, practice and/or research were well integrated. We discuss demonstration of rigour in more detail below. However, we saw instances where limited funding or tight deadlines appeared to have led to hurriedly written reports or lack of fit between funder agendas and real-world practicalities (such as challenges with implementing initiatives to be evaluated) compromised the suitability and effectiveness of the research approach taken.

Topics examined

As in REF2014, there was a preponderance of social work research on children and families, particularly child safeguarding, looked after children and young people and care leavers. In contrast, there was less attention to early help and support (services provided for children and families as soon as a problem appears). Some outputs highlighted the socio-economic, political and cultural determinants of challenges these children and families face, others focused on their individual and immediate characteristics and contexts. Many outputs discussed evaluation of new, sometimes innovative, practice or policy initiatives and their impacts; others explored pathways through and outcomes from services-as-usual. A prominent theme was child protection threshold decision-making, with relationship-based and trauma-informed practice, online harms and child trafficking more recently emerging themes.

Amongst outputs addressing social work and social care with adults and older people, established foci on ageing and dementia, mental health, disabilities, care and carers, and palliative or end-of-life care, were complemented by growth in attention to sexuality and LGBTQ+ groups, and gerotechnology. Other themes included isolation and loneliness, work and retirement and cultural and environmental gerontology.

Several research themes cross-cut service user groups. Prominent amongst them was interpersonal violence against children, women and older people. Cross-cutting themes were also commonly interdisciplinary and spoke to ‘big’ contemporary social work and policy challenges: inequalities, poverty and social exclusion, migration and digital transformation. For example, there was clear growth in outputs addressing social work with refugees, asylum seekers and migrants; with Black and Minoritised communities and on digital technologies—their opportunities and risks, impacts on practice and technological value as research tools. Intergenerational and spatial perspectives were also foregrounded.

As in REF2014, an array of outputs considered the social work profession: its governance and regulation; professional identity, ethics and values; organisational cultures; supervision and support; social workers’ well-being and professional education.

Use of theory and conceptual frameworks

There was wide variation in the extent to which outputs engaged with theory or concepts. A minority were written expressly to use a particular theoretical or conceptual lens to scrutinise social work issues. Elsewhere, variable recourse to theory could reflect significant differences in funding level and requirements. Outputs from government- or agency-commissioned research were more often targeted towards practice or policy application than theorisation. In contrast, larger-scale research council or charity funding could provide the platform for outputs whose sophisticated application of theory significantly enhanced their contributions to knowledge as well as practice and policy.