- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Reflective practice toolkit, introduction.

- What is reflective practice?

- Everyday reflection

- Models of reflection

- Barriers to reflection

- Free writing

- Reflective writing exercise

- Bibliography

Many people worry that they will be unable to write reflectively but chances are that you do it more than you think! It's a common task during both work and study from appraisal and planning documents to recording observations at the end of a module. The following pages will guide you through some simple techniques for reflective writing as well as how to avoid some of the most common pitfalls.

What is reflective writing?

Writing reflectively involves critically analysing an experience, recording how it has impacted you and what you plan to do with your new knowledge. It can help you to reflect on a deeper level as the act of getting something down on paper often helps people to think an experience through.

The key to reflective writing is to be analytical rather than descriptive. Always ask why rather than just describing what happened during an experience.

Remember...

Reflective writing is...

- Written in the first person

- Free flowing

- A tool to challenge assumptions

- A time investment

Reflective writing isn't...

- Written in the third person

- Descriptive

- What you think you should write

- A tool to ignore assumptions

- A waste of time

Adapted from The Reflective Practice Guide: an Interdisciplinary Approach / Barbara Bassot.

You can learn more about reflective writing in this handy video from Hull University:

Created by SkillsTeamHullUni

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (Word)

- Hull reflective writing video transcript (PDF)

Where might you use reflective writing?

You can use reflective writing in many aspects of your work, study and even everyday life. The activities below all contain some aspect of reflective writing and are common to many people:

1. Job applications

Both preparing for and writing job applications contain elements of reflective writing. You need to think about the experience that makes you suitable for a role and this means reflection on the skills you have developed and how they might relate to the specification. When writing your application you need to expand on what you have done and explain what you have learnt and why this matters - key elements of reflective writing.

2. Appraisals

In a similar way, undertaking an appraisal is a good time to reflect back on a certain period of time in post. You might be asked to record what went well and why as well as identifying areas for improvement.

3. Written feedback

If you have made a purchase recently you are likely to have received a request for feedback. When you leave a review of a product or service online then you need to think about the pros and cons. You may also have gone into detail about why the product was so good or the service was so bad so other people know how to judge it in the future.

4. Blogging

Blogs are a place to offer your own opinion and can be a really good place to do some reflective writing. Blogger often take a view on something and use their site as a way to share it with the world. They will often talk about the reasons why they like/dislike something - classic reflective writing.

5. During the research process

When researchers are working on a project they will often think about they way they are working and how it could be improved as well as considering different approaches to achieve their research goal. They will often record this in some way such as in a lab book and this questioning approach is a form of reflective writing.

6. In academic writing

Many students will be asked to include some form of reflection in an academic assignment, for example when relating a topic to their real life circumstances. They are also often asked to think about their opinion on or reactions to texts and other research and write about this in their own work.

Think about ... When you reflect

Think about all of the activities you do on a daily basis. Do any of these contain elements of reflective writing? Make a list of all the times you have written something reflective over the last month - it will be longer than you think!

Reflective terminology

A common mistake people make when writing reflectively is to focus too much on describing their experience. Think about some of the phrases below and try to use them when writing reflectively to help you avoid this problem:

- The most important thing was...

- At the time I felt...

- This was likely due to...

- After thinking about it...

- I learned that...

- I need to know more about...

- Later I realised...

- This was because...

- This was like...

- I wonder what would happen if...

- I'm still unsure about...

- My next steps are...

Always try and write in the first person when writing reflectively. This will help you to focus on your thoughts/feelings/experiences rather than just a description of the experience.

Using reflective writing in your academic work

Many courses will also expect you to reflect on your own learning as you progress through a particular programme. You may be asked to keep some type of reflective journal or diary. Depending on the needs of your course this may or may not be assessed but if you are using one it's important to write reflectively. This can help you to look back and see how your thinking has evolved over time - something useful for job applications in the future. Students at all levels may also be asked to reflect on the work of others, either as part of a group project or through peer review of their work. This requires a slightly different approach to reflection as you are not focused on your own work but again this is a useful skill to develop for the workplace.

You can see some useful examples of reflective writing in academia from Monash University , UNSW (the University of New South Wales) and Sage . Several of these examples also include feedback from tutors which you can use to inform your own work.

Laptop/computer/broswer/research by StockSnap via Pixabay licenced under CC0.

Now that you have a better idea of what reflective writing is and how it can be used it's time to practice some techniques.

This page has given you an understanding of what reflective writing is and where it can be used in both work and study. Now that you have a better idea of how reflective writing works the next two pages will guide you through some activities you can use to get started.

- << Previous: Barriers to reflection

- Next: Free writing >>

- Last Updated: Jun 21, 2023 3:24 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/reflectivepracticetoolkit

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

How to Write A Journa l Reflection Before you Grab Your Diary

Navigation Menu – Start & Learn

What is the point of a Reflective Diary

Examples of a Reflective Diary

How to write a Reflective Diary & Other Tips

In Short – this is how you do it

I. What is the point of a Reflective Diary

Quick explanation of a reflective diary:.

A reflective diary is a personal journal (also known as a reflective journal) where individuals write about their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Hence allowing them to reflect on their emotions, from said entry’s.

As humans we are forgetful – The Importance of a Reflective Diary:

There are multiple studies suggest the average human being has 1000’s of thoughts a day. A 2020 Study goes as far to say that this scales to 10’s of thousands if we include our subconscious thinking. Depending on which scientist you believe 50-95% of these thoughts are the same as the day before. Let me repeat that , over 50% of what we think is repeated everyday .

So if you feel life is getting reptitive , chances are it is and something needs to change.

Reflective Diaries and journaling can help identity not only these existing thought patterns but bring out the other hopeful 5-50% .

This brings to light a concept popularised by James Clear (Author of Atomic Habits) that most of what we do is subconscious – a automated habit.

How does Journaling help?

By regularly reflecting on one’s experiences and emotions, individuals can gain insight into their thoughts and behaviours, promote self-awareness, and develop coping strategies for dealing with difficult situations.

We gain regain and conquer our minds , OUR 5-50%!

Objectives of Reflective Diary

The objectives of keeping a reflective diary can vary from person to person, but may include:

- Gaining insight into one’s thoughts and behaviours

- Promoting self-awareness and self-discovery

- Improving communication skills

- Encouraging personal growth and development

- Providing a safe and non-judgmental space for reflection.

II. Examples of a Reflective Diary & Journal

There are many different ways to keep a reflective diary, and the format that works best for you may vary based on your personal preferences and goals.

There is not limits or restrictions to how much formats you use.

These are just to list the examples of reflective journals – feel free to have 1 , 3 or as many as you like!

Some common focuses of reflective diaries include:

- Daily journal reflections – a compact way to track your learning experience and self-growth

- Gratitude journals – to refocus your energy to be more positive (which in biochemistry has been linked with longevity and better living)

- Travel journals – a way to track defining moments of and relive the experience without going abroad

- Growth and self-discovery journals – identifying your “core” , your values and who you are

5 Easy Reflective Journal prompts to help get you started.

If you’re struggling to come up with things to write about, consider using prompts or questions to help guide your reflection.

Some examples of reflective journal prompts / questions include:

- What was the most difficult part of my day and why?

- What did I learn about myself today?

- What am I grateful for today?

- What challenges did I face today and how did I overcome them?

- What did I enjoy most about today?

Reflective Practice – 4 Intermediate Journal Prompts

Examples Reflective journaling can take many different forms and may include writing prompts or questions to help guide the reflection process.

Now that you’ve seen the basic’s , here are some more advanced reflective journaling prompts to consider.

Describe a difficult situation you faced today and how you responded to it.

Write about a positive experience you had today and what made it so special.

Reflect on a decision you made and why you made it.

Write about something you’re grateful for today.

III. How to Write a Reflective Diary

3 easy steps to write a reflective diary .

Beginning can often be the biggest issue and reflection can sometimes be difficult, but there are a few simple steps that can help get the cogs turning.

An easy way to remember and Apply this is a RRR framework , with the 3R’s being:

- Record or write down your thoughts and feelings in a free-flowing manner.

- Reflect on what you’ve written and consider what insights or realizations you may have gained.

- Repeat the process on a semi-regular basis and remember to review your previous logs

IV. The 4 Common Problems Of Your 1st Entry & How to Overcome Them

Problem #1: can’t seem to concentrate .

Choose a quiet place or enviorment you are comfortable with to reflect where you won’t be disturbed. The impact of your surroundings are much more detrimental than you may expect- so zoom out a bit.

Problem #2: Don’t have enough time to Journal?

Set aside a regular time each day or week for reflective journaling – this can be as rigorous as you want , whether that be routinely or every now and then. The point of this is to make it a automatic habit. To make Journaling as normal as brushing your teeth or having a shower.

Problem #3: Don’t know where to plot your thoughts?

Chances are if your reading this, even if you dont have access to paper , you definitely have access to a digital device. Decide whether you prefer a physical journal or an electronic one, and select a format that works best for you. Be willing to experiment and be as unconventional as you wish – let your initiative guide your pen or keyboard.

Problem #4: Unsure what to write or uninspired?

Simple answer, relax and write. Be honest with yourself , don’t judge your thoughts and feeling – just write them down. Be open to writing anything , even if it seems random now , it may be a key discovery to a thought pattern in the future.

In Short – How to Write a Reflective Diary

Remember that the main purpose of reflective logs is to gain insight of your own thoughts without judgment and be able to develop from them.

In order to effectively write your reflective diary , Begin with:

- Writing your thoughts & jot your feelings,

- Following the 3R’s process (Record , Reflect , Repeat)

- Finding a quiet place, set a routine, choose format, and write without judgment.

Trust and enjoy the process , quickly dethatch yourself from your day-to-day routines and embrace the silence. Dont expect instant results , prepare to review and take action from any of your new discoveries throughout your Journal Journey. Good Luck!

Terms and Conditions - Privacy Policy

- Subject Guides

Academic writing: a practical guide

Reflective writing.

- Academic writing

- The writing process

- Academic writing style

- Structure & cohesion

- Criticality in academic writing

- Working with evidence

- Referencing

- Assessment & feedback

- Dissertations

- Examination writing

- Academic posters

- Feedback on Structure and Organisation

- Feedback on Argument, Analysis, and Critical Thinking

- Feedback on Writing Style and Clarity

- Feedback on Referencing and Research

- Feedback on Presentation and Proofreading

Writing reflectively is essential to many academic programmes and also to completing applications for employment. This page considers what reflective writing is and how to do it.

What is reflection?

Reflection is something that we do everyday as part of being human. We plan and undertake actions, then think about whether each was successful or not, and how we might improve next time. We can also feel reflection as emotions, such as satisfaction and regret, or as a need to talk over happenings with friends. See below for an introduction to reflection as a concept.

Reflection in everyday life [Google Slides]

What is reflective writing?

Reflective writing should be thought of as recording reflective thinking. This can be done in an everyday diary entry, or instruction in a recipe book to change a cooking method next time. In academic courses, reflective is more complex and focussed. This section considers the main features of reflective writing.

Reflective writing for employability

When applying for jobs, or further academic study, students are required to think through what they have done in their degrees and translate it into evaluative writing that fulfils the criteria of job descriptions and person specifications. This is a different style of writing, the resource below will enable you to think about how to begin this transition.

There are also lots of resources available through the university's careers service and elsewhere on the Skills Guides. The links below are to pages that can offer further support and guidance.

- Careers and Placements Service resources Lots of resources that relate to all aspects of job applications, including tailored writing styles and techniques.

The language of reflective writing

Reflective academic writing is:

- almost always written in the first person.

- evaluative - you are judging something.

- partly personal, partly based on criteria.

- analytical - you are usually categorising actions and events.

- formal - it is for an academic audience.

- carefully constructed.

Look at the sections below to see specific vocabulary types and sentence constructions that can be useful when writing reflectively.

Language for exploring outcomes

A key element of writing reflectively is being able to explain to the reader what the results of your actions were. This requires careful grading of language to ensure that what you write reflects the evidence of what happened and to convey clearly what you achieved or did not achieve.

Below are some ideas and prompts of how you can write reflectively about outcomes, using clarity and graded language.

Expressing uncertainty when writing about outcomes:

- It is not yet clear that…

- I do not yet (fully) understand...

- It is unclear...

- It is not yet fully clear...

- It is not yet (fully?) known…

- It appears to be the case that…

- It is too soon to tell....

Often, in academic learning, the uncertainty in the outcomes is a key part of the learning and development that you undertake. It is vital therefore that you explain this clearly to the reader using careful choices in your language.

Writing about how the outcome relates to you:

- I gained (xxxx) skills…

- I developed…

- The experience/task/process taught me…

- I achieved…

- I learned that…

- I found that…

In each case you can add in words like, ‘significantly’, ‘greatly’, ‘less importantly’ etc. The use of evaluative adjectives enables you to express to the reader the importance and significance of your learning in terms of the outcomes achieved.

Describing how you reached your outcomes:

- Having read....

- Having completed (xxxx)...

- I analysed…

- I applied…

- I learned…

- I experienced…

- Having reflected…

This gives the reader an idea of the nature of the reflection they are reading. How and why you reach the conclusions and learning that you express in your reflective writing is important so the reader can assess the validity and strength of your reflections.

Projecting your outcomes into the future:

- If I completed a similar task in the future I would…

- Having learned through this process I would…

- Next time I will…

- I will need to develop…. (in light of the outcomes)

- Next time my responses would be different....

When showing the reader how you will use your learning in the future, it is important to be specific and again, to use accurate graded language to show how and why what you choose to highlight matters. Check carefully against task instructions to see what you are expected to reflect into the future about.

When reflecting in academic writing on outcomes, this can mean either the results of the task you have completed, for example, the accuracy of a titration in a Chemistry lab session, or what you have learned/developed within the task, for example, ensuring that an interview question is written clearly enough to produce a response that reflects what you wished to find out.

Language choices are important in ensuring the reader can see what you think in relation to the reflection you have done.

Language for interpretation

When you interpret something you are telling the reader how important it is, or what meaning is attached to it.

You may wish to indicate the value of something:

- superfluous

- non-essential

E.g. 'the accuracy of the transcription was essential to the accuracy of the eventual coding and analysis of the interviews undertaken. The training I undertook was critical to enabling me to transcribe quickly and accurately'

You may wish to show how ideas, actions or some other aspect developed over time:

- Initially

- subsequently

- in sequence

E.g. 'Before we could produce the final version of the presentation, we had to complete both the research and produce a plan. This was achieved later than expected, leading to subsequent rushing of creating slides, and this contributed to a lower grade'.

You may wish to show your viewpoint or that of others:

- did not think

- articulated

- did/did not do something

Each of these could be preceded by 'we' or 'I'.

E.g. 'I noticed that the model of the bridge was sagging. I expressed this to the group, and as I did so I noticed that two members did not seem to grasp how serious the problem was. I proposed a break and a meeting, during which I intervened to show the results of inaction.'

There is a huge range of language that can be used for interpretation, the most important thing is to remember your reader and be clear with them about what your interpretation is, so they can see your thinking and agree or disagree with you.

Language for analysis

When reflecting, it is important to show the reader that you have analysed the tasks, outcomes, learning and all other aspects that you are writing about. In most cases, you are using categories to provide structure to your reflection. Some suggestions of language to use when analysing in reflective writing are below:

Signposting that you are breaking down a task or learning into categories:

- An aspect of…

- An element of…

- An example of…

- A key feature of the task was... (e.g. teamwork)

- The task was multifaceted… (then go on to list or describe the facets)

- There were several experiences…

- ‘X’ is related to ‘y’

There may be specific categories that you should consider in your reflection. In teamwork, it could be individual and team performance, in lab work it could be accuracy and the reliability of results. It is important that the reader can see the categories you have used for your analysis.

Analysis by chronology:

- Subsequently

- Consequently

- Stage 1 (or other)

In many tasks the order in which they were completed matters. This can be a key part of your reflection, as it is possible that you may learn to do things in a different order next time or that the chronology influenced the outcomes.

Analysis by perspective:

- I considered

These language choices show that you are analysing purely by your own personal perspective. You may provide evidence to support your thinking, but it is your viewpoint that matters.

- What I expected from the reading did not happen…

- The Theory did not appear in our results…

- The predictions made were not fulfilled…

- The outcome was surprising because… (and link to what was expected)

These language choices show that you are analysing by making reference to academic learning (from an academic perspective). This means you have read or otherwise learned something and used it to form expectations, ideas and/or predictions. You can then reflect on what you found vs what you expected. The reader needs to know what has informed our reflections.

- Organisation X should therefore…

- A key recommendation is…

- I now know that organisation x is…

- Theory A can be applied to organisation X

These language choices show that analysis is being completed from a systems perspective. You are telling the reader how your learning links into the bigger picture of systems, for example, what an organisation or entity might do in response to what you have learned.

Analysing is a key element of being reflective. You must think through the task, ideas, or learning you are reflecting on and use categories to provide structure to your thought. This then translates into structure and language choices in your writing, so your reader can see clearly how you have used analysis to provide sense and structure to your reflections.

Language for evaluation

Reflecting is fundamentally an evaluative activity. Writing about reflection is therefore replete with evaluative language. A skillful reflective writer is able to grade their language to match the thinking it is expressing to the reader.

Language to show how significant something is:

- Most importantly

- Significantly

- The principal lesson was…

- Consequential

- Fundamental

- Insignificant

- In each case the language is quantifying the significance of the element you are describing, telling the reader the product of your evaluative thought.

For example, ‘when team working I initially thought that we would succeed by setting out a plan and then working independently, but in fact, constant communication and collaboration were crucial to success. This was the most significant thing I learned.’

Language to show the strength of relationships:

- X is strongly associated with Y

- A is a consequence of B

- There is a probable relationship between…

- C does not cause D

- A may influence B

- I learn most strongly when doing A

In each case the language used can show how significant and strong the relationship between two factors are.

For example, ‘I learned, as part of my research methods module, that the accuracy of the data gained through surveys is directly related to the quality of the questions. Quality can be improved by reading widely and looking at surveys in existing academic papers to inform making your own questions’

Language to evaluate your viewpoint:

- I was convinced...

- I have developed significantly…

- I learned that...

- The most significant thing that I learned was…

- Next time, I would definitely…

- I am unclear about…

- I was uncertain about…

These language choices show that you are attaching a level of significance to your reflection. This enables the reader to see what you think about the learning you achieved and the level of significance you attach to each reflection.

For example, ‘when using systematic sampling of a mixed woodland, I was convinced that method A would be most effective, but in reality, it was clear that method B produced the most accurate results. I learned that assumptions based on reading previous research can lead to inaccurate predictions. This is very important for me as I will be planning a similar sampling activity as part of my fourth year project’

Evaluating is the main element of reflecting. You need to evaluate the outcomes of the activities you have done, your part in them, the learning you achieved and the process/methods you used in your learning, among many other things. It is important that you carefully use language to show the evaluative thinking you have completed to the reader.

Varieties of reflective writing in academic studies

There are a huge variety of reflective writing tasks, which differ between programmes and modules. Some are required by the nature of the subject, like in Education, where reflection is a required standard in teaching.

Some are required by the industry area graduates are training for, such as 'Human Resources Management', where the industry accreditation body require evidence of reflective capabilities in graduates.

In some cases, reflection is about the 'learning to learn' element of degree studies, to help you to become a more effective learner. Below, some of the main reflective writing tasks found in University of York degrees are explored. In each case the advice, guidance and materials do not substitute for those provided within your modules.

Reflective essay writing

Reflective essay tasks vary greatly in what they require of you. The most important thing to do is to read the assessment brief carefully, attend any sessions and read any materials provided as guidance and to allocate time to ensure you can do the task well.

Reflective learning statements

Reflective learning statements are often attached to dissertations and projects, as well as practical activities. They are an opportunity to think about and tell the reader what you have learned, how you will use the learning, what you can do better next time and to link to other areas, such as your intended career.

Making a judgement about academic performance

Think of this type of writing as producing your own feedback. How did you do? Why? What could you improve next time? These activities may be a part of modules, they could be attached to a bigger piece of work like a dissertation or essay, or could be just a part of your module learning.

The four main questions to ask yourself when reflecting on your academic performance.

- Why exactly did you achieve the grade you have been awarded? Look at your feedback, the instructions, the marking scheme and talk to your tutors to find out if you don't know.

- How did your learning behaviours affect your academic performance? This covers aspects such as attendance, reading for lectures/seminars, asking questions, working with peers... the list goes on.

- How did your performance compare to others? Can you identify when others did better or worse? Can you talk to your peers to find out if they are doing something you are not or being more/less effective?

- What can you do differently to improve your performance? In each case, how will you ensure you can do it? Do you need training? Do you need a guide book or resources?

When writing about each of the above, you need to keep in mind the context of how you are being asked to judge your performance and ensure the reader gains the detail they need (and as this is usually a marker, this means they can give you a high grade!).

Writing a learning diary/blog/record

A learning diary or blog has become a very common method of assessing and supporting learning in many degree programmes. The aim is to help you to think through your day-to-day learning and identify what you have and have not learned, why that is and what you can improve as you go along. You are also encouraged to link your learning to bigger thinking, like future careers or your overall degree.

Other support for reflective writing

Online resources.

The general writing pages of this site offer guidance that can be applied to all types of writing, including reflective writing. Also check your department's guidance and VLE sites for tailored resources.

Other useful resources for reflective writing:

Appointments and workshops

- << Previous: Dissertations

- Next: Examination writing >>

- Last Updated: Apr 3, 2024 4:02 PM

- URL: https://subjectguides.york.ac.uk/academic-writing

- EW Liaison Portal

- Academic Essay

- Analytical Art Essay

- Analytical Book Review

- Analytical Film Review

- Argumentative Essay

- Literature Reviews

- Project Report

- Reflective Essay

- Disciplinary Genres

- Useful Links

You are here

- Why do we write reflective essays?

- How do we write reflective essays?

- Paragraph examples of an reflective essay

- Reflective language

- Useful Resources

- Assignment Guidelines

3. How do we write reflective essays?

Understanding the assignment

Read your assignment guidelines carefully to determine which kind of reflections your lecturer wants and what they expect; and what content, such as an event, experience, reading or process, your lecturer wants you to reflect on.

Structuring your essay

A reflective essay typically follows the familiar organisational pattern: Introduction – Body Paragraphs – Conclusion. In the body paragraphs, reflective writing involves a number of formats, and this guide will sugguest a DIEP approach, that is, to describe , interpret , evaluate and plan (Boud et al., 1985).

· Introduction

o Introduce the topic and the scope (What?)

o Justify the topic (Why?)

o Present the purpose of your essay (Thesis statement)

o Give an overview of what you will cover, i.e., description, interpretation, evaluation and plan (How?)

· Body Paragraphs (DIEP)

o Describe objectively what happened

v Give the details of what happened (Include the necessary who, what, when, where, how and why. You may not need to recall the whole experience, e.g., an incident/ lecture/ reading, but just a key aspect of the experience itself.)

v Answer: “What did you do, read, see, hear, etc.?”

o Interpret what happened

v Explain why things happened in the way they did

v Answer: “What might this experience mean?”

v Answer: “How did it make you feel?”

v Answer: “How does it relate to what you know/ have learned?”

v AbswerL “What new insights have you gained from it?”

v Answer: “What are your hypothesis/ conclusions?”

o Evaluate the effectiveness of the experience

v Make judgments on whether the experience is effective for you and how beneficial and useful the experience has been

v Answer: “What is your opinion about this experience?”

Answer: “Why do you have this opinion?”

Answer: “What is the value of this experience?”

o Plan how this experience might help you in the future

v Outline a plan for how the experience may impact your thinking or behaviour in your course, programme, future career and life in general

v Answer: “How will you transfer or apply your new knowledge and insights in the future?”

v Answer

· Conclusion

o Restate your thesis statement

o Summarise the main ideas of the body paragraphs

o State your overview of the experience regarding its usefulness and effectiveness for you and your future

For Writing Teachers

- Learn@PolyU

- EWR Consultation Booking

- Information Package for NEW Writing Teachers (Restricted Access)

- Useful materials

For CAR Teachers

- Writing Requirement Information

- Reading Requirement Information

About this website

This website is an open access website to share our English Writing Requirement (General Education) writing support materials to support these courses

- to support PolyU students’ literacy development within and across the disciplines

- to support subject and language teachers to implement system-level measures for integrating literacy-sensitive pedagogies across the university

This platform provides access to generic genre guides representing typical university assignments as well as links to subjects offered by faculties with specific disciplinary genres and relevant support materials.

The materials can be retrieved by students by choosing the genres that interest them on the landing page. Each set of materials includes a genre guide, genre video, and a genre checklist. The genre guide and video are to summarize the genres in two different ways (i.e. textual and dynamic) to fit different learning styles. The genre checklist is for students to self-regulate their writing process. The genre guide and checklist include links to various ELC resources that can provide further explanation to language items (e.g. hedging and academic vocabulary).

The platform also acts as a one-stop-shop for writing resources for students, language teachers and subject leaders. Information about the English Writing Requirement policy can also be found on this platform. There are training materials for new colleagues joining the EWR Liaison Team.

How to Write a Reflective Essay?

07 August, 2020

17 minutes read

Author: Elizabeth Brown

A reflective essay is a personal perspective on an issue or topic. This article will look at how to write an excellent reflexive account of your experience, provide you with reflexive essay framework to help you plan and organize your essay and give you a good grounding of what good reflective writing looks like.

What is a Reflective Essay?

A reflective essay requires the writer to examine his experiences and explore how these experiences have helped him develop and shaped him as a person. It is essentially an analysis of your own experience focusing on what you’ve learned.

Don’t confuse reflexive analysis with the rhetorical one. If you need assistance figuring out how to write a rhetorical analysis , give our guide a read!

Based on the reflective essay definition, this paper will follow a logical and thought-through plan . It will be a discussion that centers around a topic or issue. The essay should strive to achieve a balance between description and personal feelings.

It requires a clear line of thought, evidence, and examples to help you discuss your reflections. Moreover, a proper paper requires an analytical approach . There are three main types of a reflective essay: theory-based, a case study or an essay based on one’s personal experience.

Unlike most academic forms of writing, this writing is based on personal experiences and thoughts. As such, first-person writing position where the writer can refer to his own thoughts and feelings is essential. If the writer talks about psychology or medicine, it is best to use the first-person reference as little as possible to keep the tone objective and science-backed.

To write this paper, you need to recollect and share personal experience . However, there is still a chance that you’ll be asked to talk about a more complex topic.

By the way, if you are looking for good ideas on how to choose a good argumentative essay topic , check out our latest guide to help you out!

The Criteria for a Good Reflective Essay

The convention of an academic reflective essay writing will vary slightly depending on your area of study. A good reflective essay will be written geared towards its intended audience. These are the general criteria that form the core of a well-written piece:

- A developed perspective and line of reasoning on the subject.

- A well-informed discussion that is based on literature and sources relevant to your reflection.

- An understanding of the complex nuance of situations and the tributary effects that prevent them from being simple and clear-cut.

- Ability to stand back and analyze your own decision-making process to see if there is a better solution to the problem.

- A clear understanding of h ow the experience has influenced you.

- A good understanding of the principles and theories of your subject area.

- Ability to frame a problem before implementing a solution.

These seven criteria form the principles of writing an excellent reflective essay.

Still need help with your essay? Handmade Writing is here to assist you!

What is the Purpose of Writing a Reflective Essay?

The purpose of a reflective essay is for a writer to reflect upon experience and learn from it . Reflection is a useful process that helps you make sense of things and gain valuable lessons from your experience. Reflective essay writing allows you to demonstrate that you can think critically about your own skills or practice strategies implementations to learn and improve without outside guidance.

Another purpose is to analyze the event or topic you are describing and emphasize how you’ll apply what you’ve learned.

How to Create a Reflective Essay Outline

- Analyze the task you’ve received

- Read through and understand the marking criteria

- Keep a reflective journal during the experience

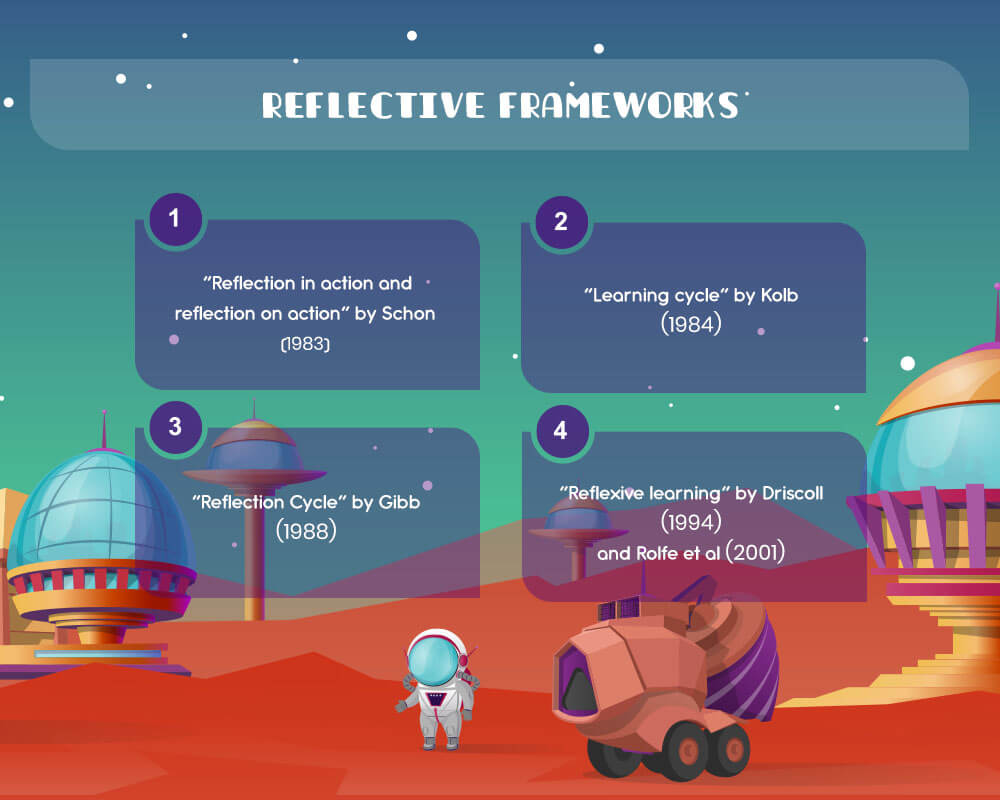

- Use a reflective framework (Schon, Driscoll, Gibbs, and Kolb) to help you analyze the experience

- Create a referencing system to keep institutions and people anonymous to avoid breaking their confidentiality

- Set the scene by using the five W’s (What, Where, When, Who and Why) to describe it

- Choose the events or the experiences you’re going to reflect on

- Identify the issues of the event or experience you want to focus on

- Use literature and documents to help you discuss these issues in a wider context

- Reflect on how these issues changed your position regarding the issue

- Compare and contrast theory with practice

- Identify and discuss your learning needs both professionally and personally

Don’t forget to adjust the formatting of your essay. There are four main format styles of any academic piece. Discover all of them from our essay format guide!

Related Posts: Essay outline | Essay format Guide

Using Reflective Frameworks

A good way to develop a reflective essay plan is by using a framework that exists. A framework will let help you break the experience down logical and make the answer easier to organize. Popular frameworks include: Schon’s (1983) Reflection in action and reflection on action .

Schon wrote ‘The Reflective Practitioner’ in 1983 in which he describes reflection-in-action and reflection-on-action as tools for learning how to meet challenges that do not conform to formulas learned in school through improvisation. He mentioned two types of reflection : one during and one after. By being aware of these processes while on a work-experience trail or clinical assignment you have to write a reflective account for, you get to understand the process better. So good questions to ask in a reflective journal could be:

<td “200”>Reflection-pre-action <td “200”>Reflection-in-action <td “200”>Reflection-on-Action<td “200”>What might happen? <td “200”>What is happening in the situation? <td “200”>What were your insights after?<td “200”>What possible challenges will you face? <td “200”>Is it working out as you expected? <td “200”>How did it go in retrospect?<td “200”>How will you prepare for the situation? <td “200”>What are the challenges you are dealing with? <td “200”>What did you value and why?<td “200”> <td “200”>What can you do to make the experience a successful one? <td “200”>What would you do differently before or during a similar situation?<td “200”> <td “200”>What are you learning? <td “200”>What have you learned?

This will give you a good frame for your paper and help you analyze your experience.

Kolb’s (1984) Learning Cycle

Kolb’s reflective framework works in four stages:

- Concrete experience. This is an event or experience

- Reflective observation. This is reflecting upon the experience. What you did and why.

- Abstract conceptualization. This is the process of drawing conclusions from the experience. Did it confirm a theory or falsify something? And if so, what can you conclude from that?

- Active experimentation. Planning and trying out the thing you have learned from this interaction.

Gibb’s (1988) Reflection Cycle

Gibbs model is an extension of Kolb’s. Gibb’s reflection cycle is a popular model used in reflective writing. There are six stages in the cycle.

- Description. What happened? Describe the experience you are reflecting on and who is involved.

- Feelings. What were you thinking and feeling at the time? What were your thoughts and feelings afterward?

- Evaluation. What was good and bad about the experience? How did you react to the situation? How did other people react? Was the situation resolved? Why and how was it resolved or why wasn’t it resolved? Could the resolution have been better?

- Analysis. What sense can you make of the situation? What helped or hindered during the event? How does this compare to the literature on the subject?

- Conclusion. What else could you have done? What have you learned from the experience? Could you have responded differently? How would improve or repeat success? How can you avoid failure?

- Action plan. If it arose again what would you do? How can you better prepare yourself for next time?

Driscoll’s Method (1994) and Rolfe et al (2001) Reflexive Learning

The Driscoll Method break the process down into three questions. What (Description), So What (Analysis) and Now What (Proposed action). Rolf et al 2001 extended the model further by giving more in-depth and reflexive questions.

- What is the problem/ difficulty/reason for being stuck/reason for feeling bad?

- What was my role in the situation?

- What was I trying to achieve?

- What actions did I take?

- What was the response of others?

- What were the consequences for the patient / for myself / for others?

- What feeling did it evoke in the patient / in myself / in others?

- What was good and bad about the experience?

- So, what were your feelings at the time?

- So, what are your feelings now? Are there any differences? Why?

- So, what were the effects of what you did or did not do?

- So, what good emerged from the situation for yourself and others? Does anything trouble you about the experience or event?

- So, what were your experiences like in comparison to colleagues, patients, visitors, and others?

- So, what are the main reasons for feeling differently from your colleagues?

- Now, what are the implications for you, your colleagues and the patients?

- Now, what needs to happen to alter the situation?

- Now, what are you going to do about the situation?

- Now, what happens if you decide not to alter anything?

- Now, what will you do differently if faced with a similar situation?

- Now, what information would you need to deal with the situation again?

- Now, what methods would you use to go about getting that information?

This model is mostly used for clinical experiences in degrees related to medicine such as nursing or genetic counseling. It helps to get students comfortable thinking over each experience and adapting to situations.

This is just a selection of basic models of this type of writing. And there are more in-depth models out there if you’re writing a very advanced reflective essay. These models are good for beginner level essays. Each model has its strengths and weaknesses. So, it is best to use one that allows you to answer the set question fully.

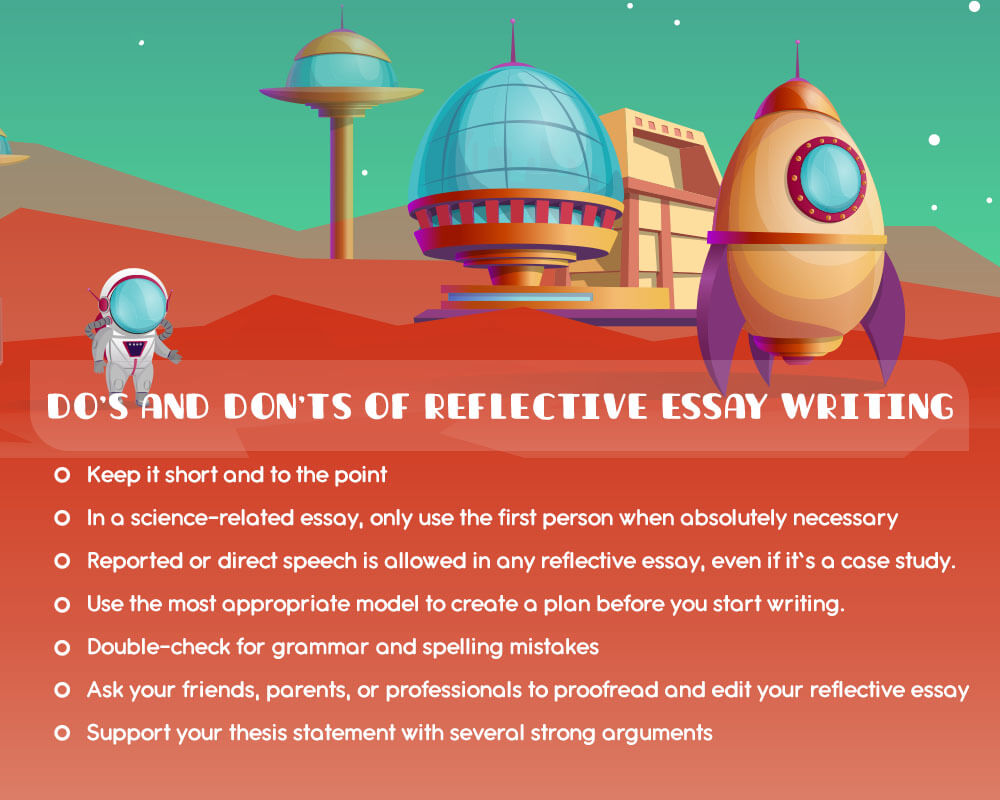

This written piece can follow many different structures depending on the subject area . So, check your assignment to make sure you don’t have a specifically assigned structural breakdown. For example, an essay that follows Gibbs plan directly with six labeled paragraphs is typical in nursing assignments. A more typical piece will follow a standard structure of an introduction, main body, and conclusion. Now, let’s look into details on how to craft each of these essay parts.

How to Write an Introduction?

There are several good ways to start a reflective essay . Remember that an introduction to a reflective essay differs depending on upon what kind of reflection is involved. A science-based introduction should be brief and direct introducing the issue you plan on discussing and its context.

Related post: How to write an Essay Introduction

For example, a nursing student might want to discuss the overreliance on medical journals in the industry and why peer-reviewed journals led to mistaken information. In this case, one good way how to start a reflective essay introduction is by introducing a thesis statement. Help the reader see the real value of your work.

Do you need help with your thesis statement? Take a look at our recent guide explaining what is a thesis statement .

Let’s look at some reflective essay examples.

‘During my first month working at Hospital X, I became aware just how many doctors treated peer-views journal articles as a gospel act. This is a dangerous practice that because of (a), (b) and (c) could impact patients negatively.’

The reflective essay on English class would begin differently. In fact, it should be more personal and sound less bookish .

How to Write the Main Body Paragraphs?

The main body of the essay should focus on specific examples of the issue in question. A short description should be used for the opener. Each paragraph of this piece should begin with an argument supporting the thesis statement.

The most part of each paragraph should be a reflexive analysis of the situation and evaluation . Each paragraph should end with a concluding sentence that caps the argument. In a science-based essay, it is important to use theories, other studies from journals and source-based material to argue and support your position in an objective manner.

How to Write the Conclusion?

A conclusion should provide a summary of the issues explored, remind the reader of the purpose of the essay and suggest an appropriate course of action in relation to the needs identified in the body of the essay.

This is mostly an action plan for the future. However, if appropriate a writer can call readers to action or ask questions. Make sure that the conclusion is powerful enough for readers to remember it. In most cases, an introduction and a conclusion is the only thing your audience will remember.

Reflective Essay Topics

Here are some good topics for a reflective essay. We’ve decided to categorize them to help you find good titles for reflective essays that fit your requirement.

Medicine-related topics:

- Write a reflective essay on leadership in nursing

- How did a disease of your loved ones (or your own) change you?

- Write a reflection essay on infection control

- How dealing with peer-reviewed journals interrupts medical procedures?

- Write a reflection essay about community service

- Write a reflective essay on leadership and management in nursing

Topics on teamwork:

- Write a reflective essay on the group presentation

- What makes you a good team player and what stays in the way of improvement?

- Write a reflective essay on the presentation

- Write about the last lesson you learned from working in a team

- A reflective essay on career development: How teamwork can help you succeed in your career?

Topics on personal experiences:

- Write a reflective essay on the pursuit of happiness: what it means to you and how you’re pursuing it?

- Write a reflective essay on human sexuality: it is overrated today? And are you a victim of stereotypes in this area?

- Write a reflective essay on growing up

- Reflective essay on death: How did losing a loved one change your world?

- Write a reflective essay about a choice you regret

- Write a reflective essay on the counseling session

Academic topics:

- A reflective essay on the writing process: How does writing help you process your emotions and learn from experiences?

- Write a reflective essay on language learning: How learning a new language changes your worldview

- A reflective essay about a choice I regret

Related Posts: Research Paper topics | Compare&Contrast Essay topics

Reflective Essay Example

Tips on writing a good reflective essay.

Some good general tips include the following:

As long as you use tips by HandMade Writing, you’ll end up having a great piece. Just stick to our recommendations. And should you need the help of a pro essay writer service, remember that we’re here to help!

A life lesson in Romeo and Juliet taught by death

Due to human nature, we draw conclusions only when life gives us a lesson since the experience of others is not so effective and powerful. Therefore, when analyzing and sorting out common problems we face, we may trace a parallel with well-known book characters or real historical figures. Moreover, we often compare our situations with […]

Ethical Research Paper Topics

Writing a research paper on ethics is not an easy task, especially if you do not possess excellent writing skills and do not like to contemplate controversial questions. But an ethics course is obligatory in all higher education institutions, and students have to look for a way out and be creative. When you find an […]

Art Research Paper Topics

Students obtaining degrees in fine art and art & design programs most commonly need to write a paper on art topics. However, this subject is becoming more popular in educational institutions for expanding students’ horizons. Thus, both groups of receivers of education: those who are into arts and those who only get acquainted with art […]

Reflective writing: Reflective essays

- What is reflection? Why do it?

- What does reflection involve?

- Reflective questioning

- Reflective writing for academic assessment

- Types of reflective assignments

- Differences between discursive and reflective writing

- Sources of evidence for reflective writing assignments

- Linking theory to experience

- Reflective essays

- Portfolios and learning journals, logs and diaries

- Examples of reflective writing

- Video summary

- Bibliography

On this page:

“Try making the conscious effort to reflect on the link between your experience and the theory, policies or studies you are reading” Williams et al., Reflective Writing

Writing a reflective essay

When you are asked to write a reflective essay, you should closely examine both the question and the marking criteria. This will help you to understand what you are being asked to do. Once you have examined the question you should start to plan and develop your essay by considering the following:

- What experience(s) and/or event(s) are you going to reflect on?

- How can you present these experience(s) to ensure anonymity (particularly important for anyone in medical professions)?

- How can you present the experience(s) with enough context for readers to understand?

- What learning can you identify from the experience(s)?

- What theories, models, strategies and academic literature can be used in your reflection?

- How this experience will inform your future practice

When structuring your reflection, you can present it in chronological order (start to finish) or in reverse order (finish to start). In some cases, it may be more appropriate for you to structure it around a series of flashbacks or themes, relating to relevant parts of the experience.

Example Essay Structure

This is an example structure for a reflective essay focusing on a single experience or event:

When you are writing a reflective assessment, it is important you keep your description to a minimum. This is because the description is not actually reflection and it often counts for only a small number of marks. This is not to suggest the description is not important. You must provide enough description and background for your readers to understand the context.

You need to ensure you discuss your feelings, reflections, responses, reactions, conclusions, and future learning. You should also look at positives and negatives across each aspect of your reflection and ensure you summarise any learning points for the future.

- << Previous: Reflective Assessments

- Next: Portfolios and learning journals, logs and diaries >>

- Last Updated: Jan 19, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/reflectivewriting

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

- Schools & departments

Structure of academic reflections

Guidance on the structure of academic reflections.

Academic reflections or reflective writing completed for assessment often require a clear structure. Contrary to some people’s belief, reflection is not just a personal diary talking about your day and your feelings.

Both the language and the structure are important for academic reflective writing. For the structure you want to mirror an academic essay closely. You want an introduction, a main body, and a conclusion.

Academic reflection will require you to both describe the context, analyse it, and make conclusions. However, there is not one set of rules for the proportion of your reflection that should be spent describing the context, and what proportion should be spent on analysing and concluding. That being said, as learning tends to happen when analysing and synthesising rather than describing, a good rule of thumb is to describe just enough such that the reader understands your context.

Example structure for academic reflections

Below is an example of how you might structure an academic reflection if you were given no other guidance and what each section might contain. Remember this is only a suggestion and you must consider what is appropriate for the task at hand and for you yourself.

Introduction

Identifies and introduces your experience or learning

- This can be a critical incident

- This can be the reflective prompt you were given

- A particular learning you have gained

When structuring your academic reflections it might make sense to start with what you have learned and then use the main body to evidence that learning, using specific experiences and events. Alternatively, start with the event and build up your argument. This is a question of personal preference – if you aren’t given explicit guidance you can ask the assessor if they have a preference, however both can work.

Highlights why it was important

- This can be suggesting why this event was important for the learning you gained

- This can be why the learning you gained will benefit you or why you appreciate it in your context

You might find that it is not natural to highlight the importance of an event before you have developed your argument for what you gained from it. It can be okay not to explicitly state the importance in the introduction, but leave it to develop throughout your reflection.

Outline key themes that will appear in the reflection (optional – but particularly relevant when answering a reflective prompt or essay)

- This can be an introduction to your argument, introducing the elements that you will explore, or that builds to the learning you have already gained.

This might not make sense if you are reflecting on a particular experience, but is extremely valuable if you are answering a reflective prompt or writing an essay that includes multiple learning points. A type of prompt or question that could particularly benefit from this would be ‘Reflect on how the skills and theory within this course have helped you meet the benchmark statements of your degree’

It can be helpful to explore one theme/learning per paragraph.

Explore experiences

- You should highlight and explore the experience you introduced in the introduction

- If you are building toward answering a reflective prompt, explore each relevant experience.

As reflection is centred around an individual’s personal experience, it is very important to make experiences a main component of reflection. This does not mean that the majority of the reflective piece should be on describing an event – in fact you should only describe enough such that the reader can follow your analysis.

Analyse and synthesise

- You should analyse each of your experiences and from them synthesise new learning

Depending on the requirements of the assessment, you may need to use theoretical literature in your analysis. Theoretical literature is a part of perspective taking which is relevant for reflection, and will happen as a part of your analysis.

Restate or state your learning

- Make a conclusion based on your analysis and synthesis.

- If you have many themes in your reflection, it can be helpful to restate them here.

Plan for the future

- Highlight and discuss how your new-found learnings will influence your future practice

Answer the question or prompt (if applicable)

- If you are answering an essay question or reflective prompt, make sure that your conclusion provides a succinct response using your main body as evidence.

Using a reflective model to structure academic reflections

You might recognise that most reflective models mirror this structure; that is why a lot of the reflective models can be really useful to structure reflective assignments. Models are naturally structured to focus on a single experience – if the assignment requires you to focus on multiple experiences, it can be helpful to simply repeat each step of a model for each experience.

One difference between the structure of reflective writing and the structure of models is that sometimes you may choose to present your learning in the introduction of a piece of writing, whereas models (given that they support working through the reflective process) will have learning appearing at later stages.

However, generally structuring a piece of academic writing around a reflective model will ensure that it involves the correct components, reads coherently and logically, as well as having an appropriate structure.

Reflective journals/diaries/blogs and other pieces of assessed reflection

The example structure above works particularly well for formal assignments such as reflective essays and reports. Reflective journal/blogs and other pieces of assessed reflections tend to be less formal both in language and structure, however you can easily adapt the structure for journals and other reflective assignments if you find that helpful.

That is, if you are asked to produce a reflective journal with multiple entries it will most often (always check with the person who issued the assignment) be a successful journal if each entry mirrors the structure above and the language highlighted in the section on academic language. However, often you can be less concerned with form when producing reflective journals/diaries.

When producing reflective journals, it is often okay to include your original reflection as long as you are comfortable with sharing the content with others, and that the information included is not too personal for an assessor to read.

Developed from:

Ryan, M., 2011. Improving reflective writing in higher education: a social semiotic perspective. Teaching in Higher Education, 16(1), 99-111.

University of Portsmouth, Department for Curriculum and Quality Enhancement (date unavailable). Reflective Writing: a basic introduction [online]. Portsmouth: University of Portsmouth.

Queen Margaret University, Effective Learning Service (date unavailable). Reflection. [online]. Edinburgh: Queen Margaret University.

Reflective Essay: Introduction, Structure, Topics, Examples For University

Table of Contents

If you’re not quite sure how to go about writing reflective essays, they can be a real stumbling block. Reflective essays are essentially a critical examination of a life experience, and with the right guidance, they don’t have to be too difficult to write. As with other essays, a reflective essay needs to be well structured and easily understood, but its content is more like a diary entry.

This guide discusses how to write a successful reflective essay, including what makes a great structure and some tips on the writing process. To make this guide the ultimate guide for anyone who needs help with reflective essays, we’ve included an example reflective essay as well.

Reflective Essay

Reflective essays require students to examine their life experiences, especially those which left an impact.

The purpose of writing a reflective essay is to challenge students to think deeply and to learn from their experiences. This is done by describing their thoughts and feelings regarding a certain experience and analyzing its impact.

Reflective essays are a unique form of academic writing that encourages introspection and self-analysis. They provide an opportunity for individuals to reflect upon their experiences, thoughts, and emotions, and effectively communicate their insights. In this article, we will explore the essential components of a reflective essay, discuss popular topics, provide guidance on how to start and structure the essay, and offer examples to inspire your writing.

I. Understanding Reflective Essays:

- Definition and purpose of reflective essays

- Key characteristics that distinguish them from other types of essays

- Benefits of writing reflective essays for personal growth and development

II. Choosing a Reflective Essay Topic:

- Exploring personal experiences and their impact

- Analyzing significant life events or milestones

- Examining challenges, successes, or failures and lessons learned

- Reflecting on personal growth and transformation

- Discussing the impact of specific books, movies, or artworks

- Analyzing the influence of cultural or social experiences

- Reflecting on internships, volunteer work, or professional experiences

III. Starting a Reflective Essay:

- Engage the reader with a captivating hook or anecdote

- Introduce the topic and provide context

- Clearly state the purpose and objectives of the reflection

- Include a thesis statement that highlights the main insights to be discussed

IV. Writing a Reflective Essay on a Class:

- Assessing the overall learning experience and objectives of the class

- Analyzing personal growth and development throughout the course

- Reflecting on challenges, achievements, and lessons learned

- Discussing the impact of specific assignments, projects, or discussions

- Evaluating the effectiveness of teaching methods and materials

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid in Reflective Essay Writing:

- Superficial reflection without deep analysis

- Overuse of personal opinions without supporting evidence

- Lack of organization and coherence in presenting ideas

- Neglecting to connect personal experiences to broader concepts or theories

- Failing to provide specific examples to illustrate key points

VI. Why “Shooting an Elephant” by George Orwell is Classified as a Reflective Essay:

- Briefly summarize the essay’s content and context

- Analyze the introspective and self-analytical elements in Orwell’s narrative

- Discuss the themes of moral conflict, imperialism, and personal conscience

- Highlight Orwell’s reflections on the psychological and emotional impact of his actions

VII. Reflective Essay Structure:

- Engaging opening statement or anecdote

- Background information and context

- Clear thesis statement

- Present and analyze personal experiences, thoughts, and emotions

- Reflect on the significance and impact of those experiences

- Connect personal reflections to broader concepts or theories

- Provide supporting evidence and specific examples

- Summarize key insights and reflections

- Emphasize the personal growth or lessons learned

- Conclude with a thought-provoking statement or call to action

VIII. Reflective Essay Examples:

- Example 1: Reflecting on a life-changing travel experience

- Example 2: Analyzing personal growth during a challenging academic year

- Example 3: Reflecting on the impact of volunteering at a local shelter

During a reflective essay, the writer examines his or her own experiences, hence the term ‘reflection’. The purpose of a reflective essay is to allow the author to recount a particular life experience. However, it should also explore how he or she has changed or grown as a result of the experience.

The format of reflective writing can vary, but you’ll most likely see it in the form of a learning log or diary entry. The author’s diary entries demonstrate how the author’s thoughts have developed and evolved over the course of a particular period of time.

The format of a reflective essay can vary depending on the intended audience. A reflective essay might be academic or part of a broader piece of writing for a magazine, for example.

While the format for class assignments may vary, the purpose generally remains the same: tutors want students to think deeply and critically about a particular learning experience. Here are some examples of reflective essay formats you may need to write:

Focusing on personal growth:

Tutors often use this type of paper to help students develop their ability to analyze their personal life experiences so that they can grow and develop emotionally. As a result of the essay, the student gains a better understanding of themselves and their behaviors.

Taking a closer look at the literature:

The purpose of this type of essay is for students to summarize the literature, after which it is applied to their own experiences.

What am I supposed to write about?

When deciding on the content of your reflective essay, you need to keep in mind that it is highly personal and is intended to engage the reader. Reflective essays are much more than just recounting a story. As you reflect on your experience (more on this later), you will need to demonstrate how it influenced your subsequent behavior and how your life has consequently changed.

Start by thinking about some important experiences in your life that have had a profound impact on you, either positively or negatively. A reflection essay topic could be a real-life experience, an imagined experience, a special object or place, a person who influenced you, or something you’ve seen or read.

If you are asked to write a reflective essay for an academic assignment, it is likely that you will be asked to focus on a particular episode – such as a time when you had to make an influential decision – and explain the results. In a reflective essay, the aftermath of the experience is especially significant; miss this out and you will simply be telling a story.

Is Remote Learning a Genuine Alternative to More Traditional Methods?

Considerations

In this type of essay, the reflective process is at the core, so it’s important that you get it right from the beginning. Think deeply about how the experience you have chosen to focus on impacted or changed you. Consider the implications for you on a personal level based on your memories and feelings.

Once you have chosen the topic of your essay, it is imperative that you spend a lot of time thinking about it and studying it thoroughly. Write down everything you remember about it, describing it as clearly and completely as you can. Use your five senses to describe your experience, and be sure to use adjectives. During this stage, you can simply take notes using short phrases, but make sure to record your reactions, perceptions, and experiences.

As soon as you’ve emptied your memory, you should begin reflecting. Choosing some reflection questions that will help you think deeply about the impact and lasting effects of your experience is a helpful way to do this. Here are some suggestions:

- As a result of the experience, what have you learned about yourself?

- What have you developed as a result? How?

- Has it had a positive or negative impact on your life?

- Looking back, what would you do differently?

- If you could go back, what would you do differently? Did you make the right decisions?

- How would you describe the experience in general? What did you learn from the experience? What skills or perspectives did you acquire?

You can use these signpost questions to kick-start your reflective process. Remember that asking yourself lots of questions is crucial to ensuring that you think deeply and critically about your experiences – a skill at the heart of a great reflective essay.

Use models of reflection (like the Gibbs or Kolb cycles) before, during, and after the learning process to ensure that you maintain a high standard of analysis. Before you get to the nitty-gritty of the process, consider questions such as: what might happen (in regards to the experience)?

Will there be any challenges? What knowledge will be needed to best prepare? When you are planning and writing, these questions may be helpful: what is happening within the learning process? Has everything worked according to plan? How am I handling the challenges that come with it?

Do you need to do anything else to ensure that the learning process is successful? Is there anything I can learn from this? Using a framework like this will enable you to keep track of the reflective process that should guide your work.

Here’s a useful tip: no matter how well prepared you feel with all that time spent reflecting in your arsenal, don’t start writing your essay until you have developed a comprehensive, well-rounded plan. There will be so much more coherence in what you write, your ideas will be expressed with structure and clarity, and your essay will probably receive higher marks as a result.

It’s especially important when writing a reflective essay as it’s possible for people to get a little ‘lost’ or disorganized as they recount their own experiences in an erratic and often unsystematic manner since it’s an incredibly personal topic. But if you outline thoroughly (this is the same thing as a ‘plan’) and adhere to it like Christopher Columbus adhered to a map, you should be fine as you embark on the ultimate step of writing your essay. We’ve summarized the benefits of creating a detailed essay outline below if you’re still not convinced of the value of planning:

An outline can help you identify all the details you plan to include in your essay, allowing you to remove all superfluous details so that your essay is concise and to the point.

Think of the outline as a map – you plan in advance which points you will navigate through and discuss in your writing. You will more likely have a clear line of thought, making your work easier to understand. You’ll be less likely to miss out on any pertinent details, and you won’t have to go back at the end and try to fit them in.

This is a real-time-saver! When you use the outline as an essay’s skeleton, you’ll save a tremendous amount of time when writing because you’ll know exactly what you want to say. Due to this, you will be able to devote more time to editing the paper and ensuring it meets high standards.

As you now know the advantages of using an outline for your reflective essay, it is important that you know how to create one. There can be significant differences between it and other typical essay outlines, mostly due to the varying topics. As always, you need to begin your outline by drafting the introduction, body, and conclusion. We will discuss this in more detail below.

Introduction

Your reflective essay must begin with an introduction that contains both a hook and a thesis statement. The goal of a ‘hook’ is to capture the attention of your audience or reader from the very beginning. In the first paragraph of your story, you should convey the exciting aspects of your story so that you can succeed in

If you think about the opening quote of this article, did it grab your attention and make you want to read more? This thesis statement summarizes the essay’s focus, which in this case is a particular experience that left a lasting impression on you. Give a quick overview of your experience – don’t give too much information away or you’ll lose readers’ interest.

Education Essay Can Come from Both a Brilliant and Mediocre Writer

Reflection Essay Structure

A reflective essay differs greatly from an argumentative or research paper in its format. Reflective essays are more like well-structured stories or diary entries that are rife with insights and reflections. Your essay may need to be formatted according to the APA style or MLA style.

In general, the length of a reflection paper varies between 300 and 700 words, but it is a good idea to check with your instructor or employer about the word count. Even though this is an essay about you, you should try to avoid using too much informal language.

The following shortcuts can help you format your paper according to APA or MLA style if your instructor asks:

MLA Format for Reflective Essay

- Times New Roman 12 pt font double spaced;

- 1” margins;

- The top right includes the last name and page number on every page;

- Titles are centered;

- The header should include your name, your professor’s name, course number, and the date (dd/mm/yy);

- The last page contains a Works Cited list.

Reflective Essay in APA Style

- Include a page header on the top of every page;

- Insert page number on the right;

- Your reflective essay should be divided into four parts: Title Page, Abstract, Main Body, and References.

Reflective Essay Outline

Look at your brainstorming table to start organizing your reflective essay. ‘Past experience’ and ‘description’ should make up less than 10% of your essay.

You should include the following in your introduction:

- Grab the reader’s attention with a short preview of what you’ll be writing about.

Example: We found Buffy head-to-toe covered in tar, starved and fur in patches, under an abandoned garbage truck.

- It is important to include ‘past experiences’ in a reflective essay thesis statement; a brief description of what the essay is about.

Example: My summer volunteering experience at the animal shelter inspired me to pursue this type of work in the future.

Chronological events are the best way to explain the structure of body paragraphs. Respond to the bold questions in the ‘reflection’ section of the table to create a linear storyline.

Here’s an example of what the body paragraph outline should look like:

- Explicit expectations about the shelter

Example: I thought it was going to be boring and mundane.

- The first impression

- Experience at the shelter

Example: Finding and rescuing Buffy.

- Other experiences with rescuing animals

- Discoveries

Example: Newly found passion and feelings toward the work.

- A newly developed mindset

Example: How your thoughts about animal treatment have changed.

Tips on How to Stay Productive While Working Remotely

Here’s How You Can Submit a Well-Written Reflective Essay for University