Student mental health is in crisis. Campuses are rethinking their approach

Amid massive increases in demand for care, psychologists are helping colleges and universities embrace a broader culture of well-being and better equipping faculty to support students in need

Vol. 53 No. 7 Print version: page 60

- Mental Health

By nearly every metric, student mental health is worsening. During the 2020–2021 school year, more than 60% of college students met the criteria for at least one mental health problem, according to the Healthy Minds Study, which collects data from 373 campuses nationwide ( Lipson, S. K., et al., Journal of Affective Disorders , Vol. 306, 2022 ). In another national survey, almost three quarters of students reported moderate or severe psychological distress ( National College Health Assessment , American College Health Association, 2021).

Even before the pandemic, schools were facing a surge in demand for care that far outpaced capacity, and it has become increasingly clear that the traditional counseling center model is ill-equipped to solve the problem.

“Counseling centers have seen extraordinary increases in demand over the past decade,” said Michael Gerard Mason, PhD, associate dean of African American Affairs at the University of Virginia (UVA) and a longtime college counselor. “[At UVA], our counseling staff has almost tripled in size, but even if we continue hiring, I don’t think we could ever staff our way out of this challenge.”

Some of the reasons for that increase are positive. Compared with past generations, more students on campus today have accessed mental health treatment before college, suggesting that higher education is now an option for a larger segment of society, said Micky Sharma, PsyD, who directs student life’s counseling and consultation service at The Ohio State University (OSU). Stigma around mental health issues also continues to drop, leading more people to seek help instead of suffering in silence.

But college students today are also juggling a dizzying array of challenges, from coursework, relationships, and adjustment to campus life to economic strain, social injustice, mass violence, and various forms of loss related to Covid -19.

As a result, school leaders are starting to think outside the box about how to help. Institutions across the country are embracing approaches such as group therapy, peer counseling, and telehealth. They’re also better equipping faculty and staff to spot—and support—students in distress, and rethinking how to respond when a crisis occurs. And many schools are finding ways to incorporate a broader culture of wellness into their policies, systems, and day-to-day campus life.

“This increase in demand has challenged institutions to think holistically and take a multifaceted approach to supporting students,” said Kevin Shollenberger, the vice provost for student health and well-being at Johns Hopkins University. “It really has to be everyone’s responsibility at the university to create a culture of well-being.”

Higher caseloads, creative solutions

The number of students seeking help at campus counseling centers increased almost 40% between 2009 and 2015 and continued to rise until the pandemic began, according to data from Penn State University’s Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH), a research-practice network of more than 700 college and university counseling centers ( CCMH Annual Report , 2015 ).

That rising demand hasn’t been matched by a corresponding rise in funding, which has led to higher caseloads. Nationwide, the average annual caseload for a typical full-time college counselor is about 120 students, with some centers averaging more than 300 students per counselor ( CCMH Annual Report , 2021 ).

“We find that high-caseload centers tend to provide less care to students experiencing a wide range of problems, including those with safety concerns and critical issues—such as suicidality and trauma—that are often prioritized by institutions,” said psychologist Brett Scofield, PhD, executive director of CCMH.

To minimize students slipping through the cracks, schools are dedicating more resources to rapid access and assessment, where students can walk in for a same-day intake or single counseling session, rather than languishing on a waitlist for weeks or months. Following an evaluation, many schools employ a stepped-care model, where the students who are most in need receive the most intensive care.

Given the wide range of concerns students are facing, experts say this approach makes more sense than offering traditional therapy to everyone.

“Early on, it was just about more, more, more clinicians,” said counseling psychologist Carla McCowan, PhD, director of the counseling center at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. “In the past few years, more centers are thinking creatively about how to meet the demand. Not every student needs individual therapy, but many need opportunities to increase their resilience, build new skills, and connect with one another.”

Students who are struggling with academic demands, for instance, may benefit from workshops on stress, sleep, time management, and goal-setting. Those who are mourning the loss of a typical college experience because of the pandemic—or facing adjustment issues such as loneliness, low self-esteem, or interpersonal conflict—are good candidates for peer counseling. Meanwhile, students with more acute concerns, including disordered eating, trauma following a sexual assault, or depression, can still access one-on-one sessions with professional counselors.

As they move away from a sole reliance on individual therapy, schools are also working to shift the narrative about what mental health care on campus looks like. Scofield said it’s crucial to manage expectations among students and their families, ideally shortly after (or even before) enrollment. For example, most counseling centers won’t be able to offer unlimited weekly sessions throughout a student’s college career—and those who require that level of support will likely be better served with a referral to a community provider.

“We really want to encourage institutions to be transparent about the services they can realistically provide based on the current staffing levels at a counseling center,” Scofield said.

The first line of defense

Faculty may be hired to teach, but schools are also starting to rely on them as “first responders” who can help identify students in distress, said psychologist Hideko Sera, PsyD, director of the Office of Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging at Morehouse College, a historically Black men’s college in Atlanta. During the pandemic, that trend accelerated.

“Throughout the remote learning phase of the pandemic, faculty really became students’ main points of contact with the university,” said Bridgette Hard, PhD, an associate professor and director of undergraduate studies in psychology and neuroscience at Duke University. “It became more important than ever for faculty to be able to detect when a student might be struggling.”

Many felt ill-equipped to do so, though, with some wondering if it was even in their scope of practice to approach students about their mental health without specialized training, Mason said.

Schools are using several approaches to clarify expectations of faculty and give them tools to help. About 900 faculty and staff at the University of North Carolina have received training in Mental Health First Aid , which provides basic skills for supporting people with mental health and substance use issues. Other institutions are offering workshops and materials that teach faculty to “recognize, respond, and refer,” including Penn State’s Red Folder campaign .

Faculty are taught that a sudden change in behavior—including a drop in attendance, failure to submit assignments, or a disheveled appearance—may indicate that a student is struggling. Staff across campus, including athletic coaches and academic advisers, can also monitor students for signs of distress. (At Penn State, eating disorder referrals can even come from staff working in food service, said counseling psychologist Natalie Hernandez DePalma, PhD, senior director of the school’s counseling and psychological services.) Responding can be as simple as reaching out and asking if everything is going OK.

Referral options vary but may include directing a student to a wellness seminar or calling the counseling center to make an appointment, which can help students access services that they may be less likely to seek on their own, Hernandez DePalma said. Many schools also offer reporting systems, such as DukeReach at Duke University , that allow anyone on campus to express concern about a student if they are unsure how to respond. Trained care providers can then follow up with a welfare check or offer other forms of support.

“Faculty aren’t expected to be counselors, just to show a sense of care that they notice something might be going on, and to know where to refer students,” Shollenberger said.

At Johns Hopkins, he and his team have also worked with faculty on ways to discuss difficult world events during class after hearing from students that it felt jarring when major incidents such as George Floyd’s murder or the war in Ukraine went unacknowledged during class.

Many schools also support faculty by embedding counselors within academic units, where they are more visible to students and can develop cultural expertise (the needs of students studying engineering may differ somewhat from those in fine arts, for instance).

When it comes to course policy, even small changes can make a big difference for students, said Diana Brecher, PhD, a clinical psychologist and scholar-in-residence for positive psychology at Toronto Metropolitan University (TMU), formerly Ryerson University. For example, instructors might allow students a 7-day window to submit assignments, giving them agency to coordinate with other coursework and obligations. Setting deadlines in the late afternoon or early evening, as opposed to at midnight, can also help promote student wellness.

At Moraine Valley Community College (MVCC) near Chicago, Shelita Shaw, an assistant professor of communications, devised new class policies and assignments when she noticed students struggling with mental health and motivation. Those included mental health days, mindful journaling, and a trip with family and friends to a Chicago landmark, such as Millennium Park or Navy Pier—where many MVCC students had never been.

Faculty in the psychology department may have a unique opportunity to leverage insights from their own discipline to improve student well-being. Hard, who teaches introductory psychology at Duke, weaves in messages about how students can apply research insights on emotion regulation, learning and memory, and a positive “stress mindset” to their lives ( Crum, A. J., et al., Anxiety, Stress, & Coping , Vol. 30, No. 4, 2017 ).

Along with her colleague Deena Kara Shaffer, PhD, Brecher cocreated TMU’s Thriving in Action curriculum, which is delivered through a 10-week in-person workshop series and via a for-credit elective course. The material is also freely available for students to explore online . The for-credit course includes lectures on gratitude, attention, healthy habits, and other topics informed by psychological research that are intended to set students up for success in studying, relationships, and campus life.

“We try to embed a healthy approach to studying in the way we teach the class,” Brecher said. “For example, we shift activities every 20 minutes or so to help students sustain attention and stamina throughout the lesson.”

Creative approaches to support

Given the crucial role of social connection in maintaining and restoring mental health, many schools have invested in group therapy. Groups can help students work through challenges such as social anxiety, eating disorders, sexual assault, racial trauma, grief and loss, chronic illness, and more—with the support of professional counselors and peers. Some cater to specific populations, including those who tend to engage less with traditional counseling services. At Florida Gulf Coast University (FGCU), for example, the “Bold Eagles” support group welcomes men who are exploring their emotions and gender roles.

The widespread popularity of group therapy highlights the decrease in stigma around mental health services on college campuses, said Jon Brunner, PhD, the senior director of counseling and wellness services at FGCU. At smaller schools, creating peer support groups that feel anonymous may be more challenging, but providing clear guidelines about group participation, including confidentiality, can help put students at ease, Brunner said.

Less formal groups, sometimes called “counselor chats,” meet in public spaces around campus and can be especially helpful for reaching underserved groups—such as international students, first-generation college students, and students of color—who may be less likely to seek services at a counseling center. At Johns Hopkins, a thriving international student support group holds weekly meetings in a café next to the library. Counselors typically facilitate such meetings, often through partnerships with campus centers or groups that support specific populations, such as LGBTQ students or student athletes.

“It’s important for students to see counselors out and about, engaging with the campus community,” McCowan said. “Otherwise, you’re only seeing the students who are comfortable coming in the door.”

Peer counseling is another means of leveraging social connectedness to help students stay well. At UVA, Mason and his colleagues found that about 75% of students reached out to a peer first when they were in distress, while only about 11% contacted faculty, staff, or administrators.

“What we started to understand was that in many ways, the people who had the least capacity to provide a professional level of help were the ones most likely to provide it,” he said.

Project Rise , a peer counseling service created by and for Black students at UVA, was one antidote to this. Mason also helped launch a two-part course, “Hoos Helping Hoos,” (a nod to UVA’s unofficial nickname, the Wahoos) to train students across the university on empathy, mentoring, and active listening skills.

At Washington University in St. Louis, Uncle Joe’s Peer Counseling and Resource Center offers confidential one-on-one sessions, in person and over the phone, to help fellow students manage anxiety, depression, academic stress, and other campus-life issues. Their peer counselors each receive more than 100 hours of training, including everything from basic counseling skills to handling suicidality.

Uncle Joe’s codirectors, Colleen Avila and Ruchika Kamojjala, say the service is popular because it’s run by students and doesn’t require a long-term investment the way traditional psychotherapy does.

“We can form a connection, but it doesn’t have to feel like a commitment,” said Avila, a senior studying studio art and philosophy-neuroscience-psychology. “It’s completely anonymous, one time per issue, and it’s there whenever you feel like you need it.”

As part of the shift toward rapid access, many schools also offer “Let’s Talk” programs , which allow students to drop in for an informal one-on-one session with a counselor. Some also contract with telehealth platforms, such as WellTrack and SilverCloud, to ensure that services are available whenever students need them. A range of additional resources—including sleep seminars, stress management workshops, wellness coaching, and free subscriptions to Calm, Headspace, and other apps—are also becoming increasingly available to students.

Those approaches can address many student concerns, but institutions also need to be prepared to aid students during a mental health crisis, and some are rethinking how best to do so. Penn State offers a crisis line, available anytime, staffed with counselors ready to talk or deploy on an active rescue. Johns Hopkins is piloting a behavioral health crisis support program, similar to one used by the New York City Police Department, that dispatches trained crisis clinicians alongside public safety officers to conduct wellness checks.

A culture of wellness

With mental health resources no longer confined to the counseling center, schools need a way to connect students to a range of available services. At OSU, Sharma was part of a group of students, staff, and administrators who visited Apple Park in Cupertino, California, to develop the Ohio State: Wellness App .

Students can use the app to create their own “wellness plan” and access timely content, such as advice for managing stress during final exams. They can also connect with friends to share articles and set goals—for instance, challenging a friend to attend two yoga classes every week for a month. OSU’s apps had more than 240,000 users last year.

At Johns Hopkins, administrators are exploring how to adapt school policies and procedures to better support student wellness, Shollenberger said. For example, they adapted their leave policy—including how refunds, grades, and health insurance are handled—so that students can take time off with fewer barriers. The university also launched an educational campaign this fall to help international students navigate student health insurance plans after noticing below average use by that group.

Students are a key part of the effort to improve mental health care, including at the systemic level. At Morehouse College, Sera serves as the adviser for Chill , a student-led advocacy and allyship organization that includes members from Spelman College and Clark Atlanta University, two other HBCUs in the area. The group, which received training on federal advocacy from APA’s Advocacy Office earlier this year, aims to lobby public officials—including U.S. Senator Raphael Warnock, a Morehouse College alumnus—to increase mental health resources for students of color.

“This work is very aligned with the spirit of HBCUs, which are often the ones raising voices at the national level to advocate for the betterment of Black and Brown communities,” Sera said.

Despite the creative approaches that students, faculty, staff, and administrators are employing, students continue to struggle, and most of those doing this work agree that more support is still urgently needed.

“The work we do is important, but it can also be exhausting,” said Kamojjala, of Uncle Joe’s peer counseling, which operates on a volunteer basis. “Students just need more support, and this work won’t be sustainable in the long run if that doesn’t arrive.”

Further reading

Overwhelmed: The real campus mental-health crisis and new models for well-being The Chronicle of Higher Education, 2022

Mental health in college populations: A multidisciplinary review of what works, evidence gaps, and paths forward Abelson, S., et al., Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research, 2022

Student mental health status report: Struggles, stressors, supports Ezarik, M., Inside Higher Ed, 2022

Before heading to college, make a mental health checklist Caron, C., The New York Times, 2022

Related topics

- Mental health

- Stress effects on the body

Contact APA

You may also like.

- Follow us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

- Criminal Justice

- Environment

- Politics & Government

- Race & Gender

Expert Commentary

Improving college student mental health: Research on promising campus interventions

Hiring more counselors isn’t enough to improve college student mental health, scholars warn. We look at research on programs and policies schools have tried, with varying results.

Republish this article

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License .

by Denise-Marie Ordway, The Journalist's Resource September 13, 2023

This <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org/education/college-student-mental-health-research-interventions/">article</a> first appeared on <a target="_blank" href="https://journalistsresource.org">The Journalist's Resource</a> and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.<img src="https://journalistsresource.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/cropped-jr-favicon-150x150.png" style="width:1em;height:1em;margin-left:10px;">

If you’re a journalist covering higher education in the U.S., you’ll likely be reporting this fall on what many healthcare professionals and researchers are calling a college student mental health crisis.

An estimated 49% of college students have symptoms of depression or anxiety disorder and 14% seriously considered committing suicide during the past year, according to a national survey of college students conducted during the 2022-23 school year. Nearly one-third of the 76,406 students who participated said they had intentionally injured themselves in recent months.

In December, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy issued a rare public health advisory calling attention to the rising number of youth attempting suicide , noting the COVID-19 pandemic has “exacerbated the unprecedented stresses young people already faced.”

Meanwhile, colleges and universities of all sizes are struggling to meet the need for mental health care among undergraduate and graduate students. Many schools have hired more counselors and expanded services but continue to fall short.

Hundreds of University of Houston students held a protest earlier this year , demanding the administration increase the number of counselors and make other changes after two students died by suicide during the spring semester, the online publication Chron reported.

In an essay in the student-run newspaper , The Cougar, last week, student journalist Malachi Key blasts the university for having one mental health counselor for every 2,122 students, a ratio higher than recommended by the International Accreditation of Counseling Services , which accredits higher education counseling services.

But adding staff to a campus counseling center won’t be enough to improve college student mental health and well-being, scholars and health care practitioners warn.

“Counseling centers cannot and should not be expected to solve these problems alone, given that the factors and forces affecting student well-being go well beyond the purview and resources that counseling centers can bring to bear,” a committee of the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine writes in a 2021 report examining the issue.

Advice from prominent scholars

The report is the culmination of an 18-month investigation the National Academies launched in 2019, at the request of the federal government, to better understand how campus culture affects college student mental health and well-being. Committee members examined data, studied research articles and met with higher education leaders, mental health practitioners, researchers and students.

The committee’s key recommendation: that schools take a more comprehensive approach to student mental health, implementing a wide range of policies and programs aimed at preventing mental health problems and improving the well-being of all students — in addition to providing services and treatment for students in distress and those with diagnosed mental illnesses.

Everyone on campus, including faculty and staff across departments, needs to pitch in to establish a new campus culture, the committee asserts.

“An ‘all hands’ approach, one that emphasizes shared responsibility and a holistic understanding of what it means in practice to support students, is needed if institutions of higher education are to intervene from anything more than a reactive standpoint,” committee members write. “Creating this systemic change requires that institutions examine the entire culture and environment of the institution and accept more responsibility for creating learning environments where a changing student population can thrive.”

In a more recent analysis , three leading scholars in the field also stress the need for a broader plan of action.

Sara Abelson , a research assistant professor at Temple University’s medical school; Sarah Lipson , an associate professor at the Boston University School of Public Health; and Daniel Eisenberg , a professor of health policy and management at the University of California, Los Angeles’ School of Public Health, have been studying college student mental health for years.

Lipson and Eisenberg also are principal investigators for the Healthy Minds Network , which administers the Healthy Minds Study , a national survey of U.S college students conducted annually to gather information about their mental health, whether and how they receive mental health care and related issues.

Abelson, Lipson and Eisenberg review the research to date on mental health interventions for college students in the 2022 edition of Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research . They note that while the evidence indicates a multi-pronged approach is best, it’s unclear which specific strategies are most effective.

Much more research needed

Abelson, Lipson and Eisenberg stress the need for more research. Many interventions in place at colleges and universities today — for instance, schoolwide initiatives aimed at reducing mental health stigma and encouraging students to seek help when in duress – should be evaluated to gauge their effectiveness, they write in their chapter, “ Mental Health in College Populations: A Multidisciplinary Review of What Works, Evidence Gaps, and Paths Forward .”

They add that researchers and higher education leaders also need to look at how campus operations, including hiring practices and budgetary decisions, affect college student mental health. It would be helpful to know, for example, how students are impacted by limits on the number of campus counseling sessions they can have during a given period, Abelson, Lipson and Eisenberg suggest.

Likewise, it would be useful to know whether students are more likely to seek counseling when they must pay for their sessions or when their school charges every member of the student body a mandatory health fee that provides free counseling for all students.

“These financially-based considerations likely influence help-seeking and treatment receipt, but they have not been evaluated within higher education,” they write.

Interventions that show promise

The report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine and the chapter by Abelson, Lipson and Eisenberg both spotlight programs and policies shown to prevent mental health problems or improve the mental health and well-being of young people. However, many intervention studies focus on high school students, specific groups of college students or specific institutions. Because of this, it can be tough to predict how well they would work across the higher education landscape.

Scientific evaluations of these types of interventions indicate they are effective:

- Building students’ behavior management skills and having them practice new skills under expert supervision . An example: A class that teaches students how to use mindfulness to improve their mental and physical health that includes instructor-led meditation exercises.

- Training some students to offer support to others , including sharing information and organizing peer counseling groups. “Peers may be ‘the single most potent source of influence’ on student affective and cognitive growth and development during college,” Abelson, Lipson and Eisenberg write.

- Reducing students’ access to things they can use to harm themselves , including guns and lethal doses of over-the-counter medication.

- Creating feelings of belonging through activities that connect students with similar interests or backgrounds.

- Making campuses more inclusive for racial and ethnic minorities, LGBTQ+ students and students who are the first in their families to go to college. One way to do that is by hiring mental health professionals trained to recognize, support and treat students from different backgrounds. “Research has shown that the presentation of [mental health] symptoms can differ based on racial and ethnic backgrounds, as can engaging in help-seeking behaviors that differ from those of cisgender, heteronormative white men,” explain members of National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine committee.

Helping journalists sift through the evidence

We encourage journalists to read the full committee report and aforementioned chapter in Higher Education: Handbook of Theory and Research . We realize, though, that many journalists won’t have time to pour over the combined 304 pages of text to better understand this issue and the wide array of interventions colleges and universities have tried, with varying success.

To help, we’ve gathered and summarized meta-analyses that investigate some of the more common interventions. Researchers conduct meta-analyses — a top-tier form of scientific evidence — to systematically analyze all the numerical data that appear in academic studies on a given topic. The findings of a meta-analysis are statistically stronger than those reached in a single study, partly because pooling data from multiple, similar studies creates a larger sample to examine.

Keep reading to learn more. And please check back here occasionally because we’ll add to this list as new research on college student mental health is published.

Peer-led programs

Stigma and Peer-Led Interventions: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Jing Sun; et al. Frontiers in Psychiatry, July 2022.

When people diagnosed with a mental illness received social or emotional support from peers with similar mental health conditions, they experienced less stress about the public stigma of mental illness, this analysis suggests.

The intervention worked for people from various age groups, including college students and middle-aged adults, researchers learned after analyzing seven studies on peer-led mental health programs written or published between 1975 and 2021.

Researchers found that participants also became less likely to identify with negative stereotypes associated with mental illness.

All seven studies they examined are randomized controlled trials conducted in the U.S., Germany or Switzerland. Together, the findings represent the experiences of a total of 763 people, 193 of whom were students at universities in the U.S.

Researchers focused on interventions designed for small groups of people, with the goal of reducing self-stigma and stress associated with the public stigma of mental illness. One or two trained peer counselors led each group for activities spanning three to 10 weeks.

Five of the seven studies tested the Honest, Open, Proud program, which features role-playing exercises, self-reflection and group discussion. It encourages participants to consider disclosing their mental health issues, instead of keeping them a secret, in hopes that will help them feel more confident and empowered. The two other programs studied are PhotoVoice , based in the United Kingdom, and

“By sharing their own experiences or recovery stories, peer moderators may bring a closer relationship, reduce stereotypes, and form a positive sense of identity and group identity, thereby reducing self-stigma,” the authors of the analysis write.

Expert-led instruction

The Effects of Meditation, Yoga, and Mindfulness on Depression, Anxiety, and Stress in Tertiary Education Students: A Meta-Analysis Josefien Breedvelt; et al. Frontiers in Psychiatry, April 2019.

Meditation-based programs help reduce symptoms of depression, anxiety and stress among college students, researchers find after analyzing the results of 24 research studies conducted in various parts of North America, Asia and Europe.

Reductions were “moderate,” researchers write. They warn, however, that the results of their meta-analysis should be interpreted with caution considering studies varied in quality.

A total of 1,373 college students participated in the 24 studies. Students practiced meditation, yoga or mindfulness an average of 153 minutes a week for about seven weeks. Most programs were provided in a group setting.

Although the researchers do not specify which types of mindfulness, yoga or meditation training students received, they note that the most commonly offered mindfulness program is Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction and that a frequently practiced form of yoga is Hatha Yoga .

Meta-Analytic Evaluation of Stress Reduction Interventions for Undergraduate and Graduate Students Miryam Yusufov; et al. International Journal of Stress Management, May 2019.

After examining six types of stress-reduction programs common on college campuses, researchers determined all were effective at reducing stress or anxiety among students — and some helped with both stress and anxiety.

Programs focusing on cognitive-behavioral therapy , coping skills and building social support networks were more effective in reducing stress. Meanwhile, relaxation training, mindfulness-based stress reduction and psychoeducation were more effective in reducing anxiety.

The authors find that all six program types were equally effective for undergraduate and graduate students.

The findings are based on an analysis of 43 studies dated from 1980 to 2015, 30 of which were conducted in the U.S. The rest were conducted in Australia, China, India, Iran, Japan, Jordan, Kora, Malaysia or Thailand. A total of 4,400 students participated.

Building an inclusive environment

Cultural Adaptations and Therapist Multicultural Competence: Two Meta-Analytic Reviews Alberto Soto; et al. Journal of Clinical Psychology, August 2018.

If racial and ethnic minorities believe their therapist understands their background and culture, their treatment tends to be more successful, this analysis suggests.

“The more a treatment is tailored to match the precise characteristics of a client, the more likely that client will engage in treatment, remain in treatment, and experience improvement as a result of treatment,” the authors write.

Researchers analyzed the results of 15 journal articles and doctoral dissertations that examine therapists’ cultural competence . Nearly three-fourths of those studies were written or published in 2010 or later. Together, the findings represent the experiences of 2,640 therapy clients, many of whom were college students. Just over 40% of participants were African American and 32% were Hispanic or Latino.

The researchers note that they find no link between therapists’ ratings of their own level of cultural competence and client outcomes.

Internet-based interventions

Internet Interventions for Mental Health in University Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Mathias Harrer; et al. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, June 2019.

Internet-based mental health programs can help reduce stress and symptoms of anxiety, depression and eating disorders among college students, according to an analysis of 48 research studies published or written before April 30, 2018 on the topic.

All 48 studies were randomized, controlled trials of mental health interventions that used the internet to engage with students across various platforms and devices, including mobile phones and apps. In total, 10,583 students participated in the trials.

“We found small effects on depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, as well as moderate‐sized effects on eating disorder symptoms and students’ social and academic functioning,” write the authors, who conducted the meta-analysis as part of the World Mental Health International College Student Initiative .

The analysis indicates programs that focus on cognitive behavioral therapy “were superior to other types of interventions.” Also, programs “of moderate length” — one to two months – were more effective.

The researchers note that studies of programs targeting depression showed better results when students were not compensated for their participation, compared to studies in which no compensation was provided. The researchers do not offer possible explanations for the difference in results or details about the types of compensation offered to students.

About The Author

Denise-Marie Ordway

Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Psychosocial Correlates of Insomnia Among College Students

ORIGINAL RESEARCH — Volume 19 — September 15, 2022

Yves Paul Vincent Mbous, MEng, BSc Hons, BSc 1 ; Mona Nili, PhD, PharmD, MS, MBA 1 ; Rowida Mohamed, MSc, BPharm 1 ; Nilanjana Dwibedi, PhD, MBA, BPharm 1 ( View author affiliations )

Suggested citation for this article: Mbous YPV, Nili M, Mohamed R, Dwibedi N. Psychosocial Correlates of Insomnia Among College Students. Prev Chronic Dis 2022;19:220060. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd19.220060 .

PEER REVIEWED

Introduction

Acknowledgments, author information.

What is already known on this topic?

Despite the well-known prevalence of insomnia among college students, its association with mental health remains a topic of considerable interest, particularly among this vulnerable population constantly adapting to the demands of the academic world.

What is added by this report?

We show that at least a quarter of college students experience insomnia, and we uncover its predominant association with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and depression.

What are the implications for public health practice?

The implications demand a serious consideration of mental health during attempts to improve students’ sleep quality.

Among college students, insomnia remains a topic of research focus, especially as it pertains to its correlates and the extent of its association with mental conditions. This study aimed to shed light on the chief predictors of insomnia among college students.

A cross-sectional survey on a convenience sample of college students (aged ≥18 years) at 2 large midwestern universities was conducted from March 18 through August 23, 2019. All participants were administered validated screening instruments used to screen for insomnia, depression, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Insomnia correlates were identified by using multivariate logistic regression.

Overall, 26.4% of students experienced insomnia; 41.2% and 15.8% had depression and had ADHD symptoms, respectively. Students with depression (adjusted odds ratio, 9.54; 95% CI, 4.50–20.26) and students with ADHD (adjusted odds ratio, 3.48; 95% CI, 1.48–8.19) had significantly higher odds of insomnia. The odds of insomnia were also significantly higher among employed students (odds ratio, 2.10; 95% CI, 1.05–4.18).

This study showed an association between insomnia and mental health conditions among college students. Policy efforts should be directed toward primary and secondary prevention programs that enforce sleep education interventions, particularly among employed college students and those with mental illnesses.

The National Sleep Foundation and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society guidelines recommend 7 to 9 hours of sleep for young adults (1). However, at least 60% of college students have poor quality sleep and garner, on average, 7 hours of sleep per night (2). Previous research showed that up to 75% of college students reported occasional sleep disturbances, while 15% reported overall poor sleep quality (3). In another work, among a sample of 191 undergraduate students, researchers found that 73% of students exhibited some form of sleep problem, with a higher frequency among women than men (4).

Direct consequences of poor sleep among college students include increased tension, irritability, depression, confusion, reduced life satisfaction, or poor academic performance (4). Evidence abounds of the positive correlation between academic failure, low grade point average, negative academic performance, and poor sleep quality patterns (5). As these complications arise early in the life of these students, they might develop into serious ailments as they grow older (high blood pressure, diabetes, stroke) and thereby create an even bigger public health problem. Because insomnia weakens physical and mental functions in addition to academic performances, reduced sleep quality could also lead to mental issues or vice versa (6).

Erratic schedules and lifestyle adjustments coupled with the strain of daily occupation are partly to blame for the general dissatisfaction with sleep quality and duration, because work obligations reduce hours of sleep among college students (2). However, in light of these consequences, it behooves the scientific community to identify modifiable factors associated with insomnia among college students that could help spur countermeasures or design lifestyle interventions to ameliorate the overall well-being of college students. In this study, we strived to identify environmental, mental, and behavioral factors affecting insomnia among college students. The intersection between behavioral factors and mental health is also evaluated in this work because physical activity, particularly, has been shown to mitigate insomnia (7). Because the relationship between insomnia and some of the understudied mental conditions could be bidirectional and given that cause-and-effect will not be established in this study, insomnia was labeled a criterion variable.

Study design, sampling, eligibility criteria

A cross-sectional design was used for this study. Convenience and snowball sampling strategy methods were used for sampling. West Virginia University and Marshall University students aged 18 years or older and able to read and write in English were eligible to participate. Study approval was acquired from the Institutional Review Board of West Virginia University. Consent for participation and anonymity were emphasized before the questionnaire’s distribution, along with instructions for completion. No incentives were provided for participants in this study.

Instruments and measures

Demographic characteristics included sex (male, female), age, race (White; All others, which included Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and any other racial group), marital status (married, not married), educational level (undergraduate, professional or graduate), employment status (employed, unemployed), physical activity (<2 d/wk, ≥2 d/wk), caffeine consumption (<6 cups/d, ≥6 cups/d, because previous research established a daily upper limit of 6 cups to maintain a healthy heart and blood pressure [8]), alcohol use (never, some days or every day), smoking status (yes, no), and the number of chronic non–mental health conditions (guided by the US Health and Human Services’ strategic framework [9], and included arthritis, asthma, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Crohn disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, epilepsy, heart disease, HIV/AIDS, and multiple sclerosis).

The criterion variable in this study was a diagnosis of insomnia as assessed by the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI). The ISI uses 7 items to evaluate the severity of insomnia. The first 3 items assess severity of sleep onset, sleep maintenance, and early morning awakening problems, and the last 4 examine sleep satisfaction, sleep disturbance, sleep worry, and sleep interference in daily life (10). Each item is graded on a 0 to 4 Likert scale, and the total score is calculated as the sum of each item, yielding minimum and maximum values of 0 and 28, respectively. Total score categories are as follows: 0 to 7 = no clinically significant insomnia; 8 to 14 = subthreshold insomnia; 15 to 21 = clinical insomnia (moderate severity); 22 to 28 = clinical insomnia (severe). In this study, ISI scores were divided into 2 categories based on a cutoff point of 15: patients with clinically significant insomnia (cutoff point of 15 or more) and participants with no clinically significant insomnia (cutoff point less than 15). This threshold point was motivated by the validity of this scale as a primary care diagnostic tool at a cutoff score of 14 (11).

Instruments to screen for depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) were used to evaluate mental health. For depression, we used the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), a self-reported questionnaire that contains 9 items incorporating the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) IV criteria for probable major depressive disorder. Each item can be scored from 0 through 3, and total scores can vary from 0 to 27, with cutoff points of 5, 10, 15, and 20, corresponding respectively to diagnoses of mild, moderate, moderately severe, and severe depressive symptoms. Given the high correlation observed in the literature between the third item of the PHQ-9 (also assessing sleep disturbance) and various sleep scales (12,13), we removed this item before calculating the overall score. PHQ-9 scores were divided into 2 categories: participants with clinically significant depressive symptoms (cutoff point of 8 or more) and participants with no clinically significant depressive symptoms (cutoff point less than 8). This was dictated by the sensitivity and specificity of the PHQ-9 at this cutoff score as a satisfactory diagnostic tool for depression in primary and secondary care settings (14).

For ADHD, Part A of the Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) was used. Only Part A of the questionnaire contains the 6 predictive measures of ADHD symptom severity (15). Items use a Likert scale (never, rarely, sometimes, often, very often). For items 1 to 3, ratings of sometimes, often, or very often were assigned 1 point (ratings of never or rarely were assigned 0 points). For the remaining items, ratings of often or very often were assigned 1 point (ratings of never, rarely, or sometimes were assigned 0 points). A sum of scores of 4 or more indicated ADHD symptoms. Diagnosis of anxiety was established using an item that elicited from participants a recent diagnosis of anxiety or current medication regimen for anxiety. The criterion variable and predictors in this study were collected using a 3-part questionnaire, including demographics, insomnia screening, and mental health screening.

Survey procedure

The online survey was administered using the Qualtrics (Qualtrics) web-based survey tool. The invitation letter to participate in this survey was sent to participants through the listserve to students and social media outlets (Facebook and Twitter) from March 18 through August 23, 2019.

Data analysis

During the analysis, we omitted responses with half or more missing information (75 incomplete and missing responses were excluded from the final sample) from the criterion variable (insomnia) and predictors (ie, ADHD, anxiety, depression, chronic non–mental health conditions, employment status, sex, race and ethnicity, sex, education level, physical activity status, alcohol and caffeine consumption, and smoking). Descriptive statistics were used to describe the study participants. Cell sizes with fewer than 5 were conflated with the next immediate encompassing category. Significant differences in outcomes among predictive factors were determined by using independent t tests. Differences were labeled significant at an α level less than or equal to .05. Were used χ 2 tests of independence to compare the distribution of dependent categorical or nominal variables and the distribution in the criterion variable (for large cell sizes). Fisher tests were used for the same purpose, albeit for smaller cell sizes (~ n = 5). We did not apply any statistical adjustments (eg, Bonferroni adjustments) for multiple comparisons on the same sample out of concern for the substantial reduction in the statistical power of rejecting an incorrect Ho in each test (16).

Multivariable logistic regression models were built to model a relationship between predictors and insomnia. We included logistic regression models analyzing the interaction between different mental conditions and between physical activity and mental health (diagnosis of anxiety, depression, or ADHD). Model 1 regressed the dependent variable on all independent variables. Models 2 through 4 added 2-way interactions between mental conditions, namely anxiety, ADHD, and depression, respectively, and physical activity. From each of these models, odds ratios were derived. The analysis was conducted by using SPSS version 26 (IBM Corp).

Validity and reliability

To validate the use of the foregoing instruments in a college population, we conducted confirmatory factor analyses. Results indicated loading patterns consistent with the structure of the adopted scales. Our method of choice was principal component analysis with varimax rotation. The ISI was a unidimensional scale with factor loading ranging from 0.375 to 0.876. The unidimensional PHQ-9 factor loadings oscillated between 0.627 and 0.881. The ASRS, also unidimensional, had factor loadings ranging from 0.462 to 0.803. The reliability of the ISI, PHQ-9, and ASRS, as assessed using the Cronbach α (0.857, 0.909, 0.768, respectively), was excellent. The degree of concordance between the ISI and the nonsleep scales (divergent validity) was evaluated by using correlation coefficients. We found a weak to moderate magnitude of correlation ( r < 0.7), based on a widespread threshold from the literature (17).

A total of 330 responses were included in our analysis ( Table 1 ). The mean age of participants was 24.4 years old. Across the entire sample, most participants were women (67.0%), White (89.7%), not married (94.2%), undergraduate students (62.4%), and with no chronic non–mental health conditions (69.7%). Based on the screening questionnaires, the prevalences of anxiety, depression, ADHD, and insomnia were 28.5%, 41.2.%, 15.8%, and 26.4%, respectively.

Among the participants with insomnia, most were women (81.6%), White (83.9%), undergraduate students (65.5%), physically active on 2 or more days during the week (79.3%), consumed less than 6 cups of caffeine per day (88.5%), at least occasionally consumed alcohol (67.8%), were nonsmokers (93.1%), had no chronic conditions (58.6%), were not anxious constantly (63.2%), were depressed (78.2%), and had no symptoms of ADHD (62.1%). In general, participants without insomnia followed the same trend, except that most did not have depression (71.2%). Employment status in both groups (participants with and those without insomnia) was roughly similar. Sex, race, the number of chronic non–mental health conditions, depression, and ADHD symptoms were found to be significant correlates of insomnia ( Table 1 ).

Findings from models 2 and 4 were not significant. In model 3, the multiple logistic regression model indicated that psychosocial factors such as employment status, depression, and ADHD significantly increased the odds of insomnia ( Table 2 ). Employed students had 2.10 times higher odds of insomnia compared with unemployed students. In addition, the odds of insomnia were 9.54 and 3.48 times higher for students with depression and ADHD, respectively. Anxiety was not significantly associated with insomnia (adjusted odds ratio: 1.71, P = .13). Physical activity was a significant effect modifier in the association between ADHD and insomnia (adjusted odds ratio: 12.1, P = 0.012). The strength of the association between ADHD symptoms and insomnia was lower among students who exercised 2 or more days a week compared with those who exercised less.

In this study, we identified factors associated with insomnia among college students. ADHD, depression, and employment status were significantly associated with insomnia. We reported a 26.4% prevalence of insomnia among college students, a finding consistent with existing literature. A previous meta-analysis reported an overall insomnia prevalence of 18.5% (95% CI, 11.2%–28.8%) among university students; our estimate fell within this reported CI (6). Another study found that insomnia prevalence was 26.7% among university nursing students (18). Taylor and coworkers reported an insomnia prevalence of 9.5% among a cohort of 1,039 college students by using the ISI and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) (19); their operational definition of chronic insomnia was established over 3 months as opposed to 1 month in our study. In our work, small cell sizes restricted the categorization of insomnia into moderate, mild, or severe. This explains the deviation of our results from those of past researchers that used the ISI systematic classification of different degrees of insomnia. For instance, Gress-Smith et al found that 47% of college students had mild insomnia and 22.5% had moderate to severe insomnia (20). In another ISI-based study, 12% of students endorsed a diagnosis of clinical insomnia, and 45% met the criteria for subclinical insomnia (21). All these intricacies cement our results within the current pool of research.

Our findings indicated that 78.2% of students with insomnia also experienced depression, and the odds of insomnia were 9.54 times higher among students with depression than students without depression. Olufsen et al reported a prevalence of depression among college students with insomnia of 30% to 38%, using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV) (22). Another research concluded that depressive symptoms, assessed using criteria of the DSM-IV, were associated with increased insomnia complaints among college students (odds ratio, 1.09) (23). These findings lend credence to the bidirectional relationship between insomnia and depression. Thus, it is typical of patients with insomnia to exhibit psychological profiles (poor coping skills, poor health status, ruminative traits) that herald the onset of depression. Ubiquitous characteristics of insomnia, such as fatigue, irritability, and cognitive impairment, which are well-known derivatives of insomnia among students, exacerbate depressive symptoms (24).

In our sample, 15.8% had ADHD, and the odds of insomnia were 3.48 times higher for students with ADHD than those without ADHD. The prevalence of clinically significant cases of ADHD varies between 2% and 8% of the college student population (25). A previous study showed a similar ADHD prevalence to ours at ~19% (26). In the same study, the authors also reported that students with ADHD had a risk of insomnia 2.7 times greater than those without ADHD (26). These observations indicate the importance of examining symptom clusters that involve both sleep and mental and emotional components when investigating and treating insomnia, depression, or ADHD.

Physical activity mitigated the effect of mental health on insomnia. As regular physical activity helps improve sleep quality (7) and has psychological benefits (27), it was not surprising to find that among those with mental conditions, those who exercised more often (in this case, 2 or more days per week) seemed to have better sleep quality than those who exercised less. Students are often hesitant to seek help for mental health and insomnia concerns; therefore, interventions need to be youth-friendly, acceptable, feasible, and nonstigmatizing (28). Young people view physical activity as helpful in mitigating mental conditions as well as being nonstigmatizing (29). Although most university campuses offer physical activity–based wellness programs, research exploring students’ perceptions of on-campus physical activity initiatives as alternatives to mental health and insomnia management strategy is limited (30).

We found that employment was significantly associated with sleep problems among college students. Similarly, previous research has linked employment to insomnia. A meta-analysis found job demand to be negatively correlated with sleep quality, whereas job control was positively correlated (31). Students, most of whom held part-time jobs and thus had less job control yet high job demands, might understandably experience substantial sleep difficulties and reduced sleep quality in general. Also, the competing demands to complete academic requirements and maintain employment may also serve as structural barriers to adequate sleep.

Strengths and limitations

This study had several strengths. First, we evaluated factors susceptible to accompany a diagnosis of insomnia in a sample of college students. Further, we used established instruments that we validated psychometrically across a new population. However, this study had a few limitations. First, the data were collected from 2 universities, namely West Virginia and Marshall University, thus limiting the generalizability of the findings. Information on study majors was not collected, yet could have influenced the prevalence and the uncovered associations of insomnia and mental conditions. Further, we used a cross-sectional design and could only establish association, not causality. Finally, small cell sizes restricted the stratification of insomnia, which would have enriched our results.

Our results indicate that better mental health and insomnia must be addressed concomitantly as their association is not random. Addressing these issues entails better time management skills dedicated to studying, work, and leisure. Such skills should be at the fingertips of college students to help them cope with the increasing demands of university life. These findings should also be communicated to the employers of college students who in turn should prioritize the overall well-being of their employees. As a future direction for our work, we endeavor to measure health services utilization among students with mental conditions that tie directly to sleep quality; this, in a bid, to inform policy on the need to improve mental health services access for college students.

The burden of insomnia among college students is one that must be readily addressed as its spillover effects decrease substantial traits that are crucial for college life. Mental health, specifically depression and ADHD, and employment are salient contributors to the high levels of insomnia. Addressing these associations could help improve the experience and well-being of college students. Further, the promotion on campuses of healthy behaviors such as physical activity could yield significant improvements vis-à-vis the lifestyle of college students, as physical activity, in this study, has been shown to mitigate the effect of mental health on insomnia or vice versa.

The authors would like to thank Jason Kang, MD, MS, for his input during the conception of this study.

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest, and the authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this article are included within the study. No financial support was received for this work. Permission to use the ASRS was obtained from Ronald C. Kessler.

Author contributions: conceptualization, all authors; data curation, Mr Mbous and Dr Nili; formal analysis, Mr Mbous, Dr Nili, and Ms Mohamed; investigation and methodology, all authors; project administration, Mr Mbous and Dr Nili; supervision, Dr Dwibedi; writing the original draft, Mr Mbous; writing review and editing, all authors.

Corresponding Author: Yves Paul Vincent Mbous, MEng, BSc Hons, BSc, School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Systems and Policy, PO Box 9510, Morgantown, WV 26506. Email: [email protected] .

Author Affiliations: 1 School of Pharmacy, Department of Pharmaceutical Systems and Policy, West Virginia University, Morgantown, West Virginia.

- Hirshkowitz M, Whiton K, Albert SM, Alessi C, Bruni O, DonCarlos L, et al. National Sleep Foundation’s sleep time duration recommendations: methodology and results summary. Sleep Health 2015;1(1):40–3. CrossRef PubMed

- Lund HG, Reider BD, Whiting AB, Prichard JR. Sleep patterns and predictors of disturbed sleep in a large population of college students. J Adolesc Health 2010;46(2):124–32. CrossRef PubMed

- Sing CY, Wong WS. Prevalence of insomnia and its psychosocial correlates among college students in Hong Kong. J Am Coll Health 2010;59(3):174–82. CrossRef PubMed

- Buboltz WC Jr, Brown F, Soper B. Sleep habits and patterns of college students: a preliminary study. J Am Coll Health 2001;50(3):131–5. CrossRef PubMed

- Gomes AA, Tavares J, de Azevedo MHP. Sleep and academic performance in undergraduates: a multi-measure, multi-predictor approach. Chronobiol Int 2011;28(9):786–801. CrossRef PubMed

- Jiang XL, Zheng XY, Yang J, Ye CP, Chen YY, Zhang ZG, et al. A systematic review of studies on the prevalence of insomnia in university students. Public Health 2015;129(12):1579–84. CrossRef PubMed

- Hartescu I, Morgan K. Regular physical activity and insomnia: an international perspective. J Sleep Res 2019;28(2):e12745. CrossRef PubMed

- Zhou A, Hyppönen E. Long-term coffee consumption, caffeine metabolism genetics, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective analysis of up to 347,077 individuals and 8368 cases. Am J Clin Nutr 2019;109(3):509–16. CrossRef PubMed

- Goodman RA, Posner SF, Huang ES, Parekh AK, Koh HK. Defining and measuring chronic conditions: imperatives for research, policy, program, and practice. Prev Chronic Dis 2013;10:E66. CrossRef PubMed

- Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep 2011;34(5):601–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Gagnon C, Bélanger L, Ivers H, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index in primary care. J Am Board Fam Med 2013;26(6):701–10. CrossRef PubMed

- Collins AR, Cheung J, Croarkin PE, Kolla BP, Kung S. Effects of transcranial magnetic stimulation on sleep quality and mood in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Sleep Med 2022;18(5):1297–1305. CrossRef PubMed

- Schulte T, Hofmeister D, Mehnert-Theuerkauf A, Hartung T, Hinz A. Assessment of sleep problems with the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) and the sleep item of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2021;29(12):7377–84. CrossRef PubMed

- Manea L, Gilbody S, McMillan D. Optimal cut-off score for diagnosing depression with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): a meta-analysis. CMAJ 2012;184(3):E191–6. CrossRef PubMed

- Daigre Blanco C, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Valero S, Bosch R, Roncero C, Gonzalvo B, et al. Adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS-v1.1) symptom checklist in patients with substance use disorders. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2009;37(6):299–305. PubMed

- Perneger TV. What’s wrong with Bonferroni adjustments. BMJ 1998;316(7139):1236–8. CrossRef PubMed

- Abma IL, Rovers M, van der Wees PJ. Appraising convergent validity of patient-reported outcome measures in systematic reviews: constructing hypotheses and interpreting outcomes. BMC Res Notes 2016;9(1):226. CrossRef PubMed

- Angelone AM, Mattei A, Sbarbati M, Di Orio F. Prevalence and correlates for self-reported sleep problems among nursing students. J Prev Med Hyg 2011;52(4):201–8. PubMed

- Taylor DJ, Bramoweth AD, Grieser EA, Tatum JI, Roane BM. Epidemiology of insomnia in college students: relationship with mental health, quality of life, and substance use difficulties. Behav Ther 2013;44(3):339–48. CrossRef PubMed

- Gress-Smith JL, Roubinov DS, Andreotti C, Compas BE, Luecken LJ. Prevalence, severity and risk factors for depressive symptoms and insomnia in college undergraduates. Stress Health 2015;31(1):63–70. CrossRef PubMed

- Gellis LA, Park A, Stotsky MT, Taylor DJ. Associations between sleep hygiene and insomnia severity in college students: cross-sectional and prospective analyses. Behav Ther 2014;45(6):806–16. CrossRef PubMed

- Olufsen IS, Sørensen ME, Bjorvatn B. New diagnostic criteria for insomnia and the association between insomnia, anxiety and depression. Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2020;140(1). PubMed

- Fernández-Mendoza J, Vela-Bueno A, Vgontzas AN, Olavarrieta-Bernardino S, Ramos-Platón MJ, Bixler EO, et al. Nighttime sleep and daytime functioning correlates of the insomnia complaint in young adults. J Adolesc 2009;32(5):1059–74. CrossRef PubMed

- Grandner MA, Malhotra A. Connecting insomnia, sleep apnoea and depression. Respirology 2017;22(7):1249–50. CrossRef PubMed

- DuPaul GJ, Weyandt LL, O’Dell SM, Varejao M. College students with ADHD: current status and future directions. J Atten Disord 2009;13(3):234–50. CrossRef PubMed

- Evren B, Evren C, Dalbudak E, Topcu M, Kutlu N. The impact of depression, anxiety, neuroticism, and severity of Internet addiction symptoms on the relationship between probable ADHD and severity of insomnia among young adults. Psychiatry Res 2019;271:726–31. CrossRef PubMed

- Mourady D, Richa S, Karam R, Papazian T, Hajj Moussa F, El Osta N, et al. Associations between quality of life, physical activity, worry, depression and insomnia: a cross-sectional designed study in healthy pregnant women. PLoS One 2017;12(5):e0178181. CrossRef PubMed

- Aguirre Velasco A, Cruz ISS, Billings J, Jimenez M, Rowe S. What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 2020;20(1):293. CrossRef PubMed

- Mason OJ, Holt R. Mental health and physical activity interventions: a review of the qualitative literature. J Ment Health 2012;21(3):274–84. CrossRef PubMed

- deJonge ML, Jain S, Faulkner GE, Sabiston CM. On campus physical activity programming for post-secondary student mental health: examining effectiveness and acceptability. Ment Health Phys Act 2021;20:100391. CrossRef

- Van Laethem M, Beckers DGJ, Kompier MAJ, Dijksterhuis A, Geurts SAE. Psychosocial work characteristics and sleep quality: a systematic review of longitudinal and intervention research. Scand J Work Environ Health 2013;39(6):535–49. CrossRef PubMed

| Variable | Total | No Insomnia | Insomnia | value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24.4 (4.4) | 25.1 (4.6) | 23.7 (3.7) | .084 | |

| Male | 109 (33.0) | 93 (38.3) | 16 (18.4) | .001 |

| Female | 221 (67.0) | 150 (61.7) | 71 (81.6) | |

| White | 296 (89.7) | 223 (91.8) | 73 (83.9) | .04 |

| All others | 34 (10.3) | 20 (8.2) | 14 (16.1) | |

| Not married | 311 (94.2) | 226 (93.0) | 85 (97.7) | .29 |

| Married | 19 (5.8) | 17 (7.0) | 2 (2.3) | |

| Undergraduate | 206 (62.4) | 149 (61.3) | 57 (65.5) | .49 |

| Professional or graduate | 124 (37.6) | 94 (38.7) | 30 (34.5) | |

| No | 178 (53.9) | 132 (54.3) | 46 (52.9) | .82 |

| Yes | 152 (46.1) | 111 (45.7) | 41 (47.1) | |

| <2 d/wk | 48 (14.5) | 30 (12.3) | 18 (20.7) | .06 |

| ≥2 d/wk | 282 (85.5) | 213 (87.7) | 69 (79.3) | |

| <6 cups/d | 298 (90.3) | 221 (90.9) | 77 (88.5) | .56 |

| ≥6 cups/d | 20 (6.1) | 16 (6.6) | 4 (4.6) | |

| Not at all | 116 (35.2) | 88 (36.2) | 28 (32.2) | .19 |

| Some days or every day | 214 (64.8) | 155 (63.8) | 59 (67.8) | |

| Not at all | 310 (93.9) | 229 (94.2) | 81 (93.1) | .49 |

| Every day and some days | 20 (6.1) | 14 (5.8) | 6 (6.9) | |

| 0 | 230 (69.7) | 179 (73.7) | 51 (58.6) | <.001 |

| 1 | 72 (21.8) | 52 (21.4) | 20 (23.0) | |

| ≥2 | 28 (8.5) | 12 (4.9) | 16 (18.4) | |

| No | 236 (71.5) | 181 (74.5) | 55 (63.2) | .05 |

| Yes | 94 (28.5) | 62 (25.5) | 32 (36.8) | |

| No | 192 (58.2) | 173 (71.2) | 19 (21.8) | <.001 |

| Yes | 136 (41.2) | 68 (28.0) | 68 (78.2) | |

| No | 276 (83.6) | 222 (91.4) | 54 (62.1) | <.001 |

| Yes | 52 (15.8) | 21 (8.6) | 31 (35.6) | |

| No | 286 (86.7) | 227 (93.4) | 59 (67.8) | < .001 |

| Yes | 40 (12.1) | 14 (5.8) | 26 (29.9) | |

| No | 280 (84.8) | 217 (89.3) | 63 (72.4) | <.001 |

| Yes | 48 (14.5) | 24 (9.9) | 24 (27.6) | |

| No | 314 (95.2) | 239 (98.4) | 75 (86.2) | .001 |

| Yes | 14 (4.2) | 4 (1.6) | 10 (11.5) | |

Abbreviations: ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; NA, not applicable. a Data are number (percentage) unless otherwise specified. Numbers may not add to total because of missing data. b Independent t test. c Pearson χ 2 . d P value between .001 and <.01. e P value between .01 and <.05. f All other races included Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and any other racial group. g Fisher exact test. h P < .001.

| Predictor | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | value |

|---|---|---|

| 1.07 (0.95–1.20) | .26 | |

| Male | 1 [Reference] | .09 |

| Female | 1.93 (0.90–4.17) | |

| All others | 1 [Reference] | .35 |

| White | 0.61 (0.21–1.73) | |

| Not married | 1 [Reference] | .19 |

| Married | 1.51 (0.82–2.80) | |

| Undergraduate | 1 [Reference] | .96 |

| Professional or graduate | 0.98 (0.39–2.48) | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | .04 |

| Yes | 2.10 (1.05–4.18) | |

| <2 d/wk | 1 [Reference] | .88 |

| ≥2 d/wk | 0.94 (0.38–2.31) | |

| <6 cups/d | 1 [Reference] | .17 |

| ≥6 cups/d | 0.33 (0.07–1.60) | |

| Never or some days | 1 [Reference] | .87 |

| Every day | 0.81 (0.07–9.54) | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | .36 |

| Yes | 1.55 (0.61–3.96) | |

| 1.65 (1.08–2.52) | .02 | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | .13 |

| Yes | 1.71 (0.85–3.42) | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | <.001 |

| Yes | 9.54 (4.50–20.26) | |

| No | 1 [Reference] | .004 |

| Yes | 3.48 (1.48–8.19) | |

a All other races included Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander, and any other racial group. b P value between .01 and <.05. c P < .001. d P value between .001 and <.01.

The opinions expressed by authors contributing to this journal do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Public Health Service, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or the authors’ affiliated institutions.

Exit Notification / Disclaimer Policy

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal website.

- Linking to a non-federal website does not constitute an endorsement by CDC or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the website.

- You will be subject to the destination website's privacy policy when you follow the link.

- CDC is not responsible for Section 508 compliance (accessibility) on other federal or private website.

Advertisement

Changes in College Students Mental Health and Lifestyle During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies

- Systematic Review

- Open access

- Published: 03 August 2022

- Volume 7 , pages 537–550, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Chiara Buizza ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3339-3539 1 ,

- Luciano Bazzoli 1 &

- Alberto Ghilardi 1

10k Accesses

48 Citations

62 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

College students have poorer mental health than their peers. Their poorer health conditions seem to be caused by the greater number of stressors to which they are exposed, which can increase the risk of the onset of mental disorders. The pandemic has been an additional stressor that may have further compromised the mental health of college students and changed their lifestyles with important consequences for their well-being. Although research has recognized the impact of COVID-19 on college students, only longitudinal studies can improve knowledge on this topic. This review summarizes the data from 17 longitudinal studies examining changes in mental health and lifestyle among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to improve understanding of the effects of the outbreak on this population. Following PRISMA statements, the following databases were searched PubMed, EBSCO, SCOPUS and Web of Science. The overall sample included 20,108 students. The results show an increase in anxiety, mood disorders, alcohol use, sedentary behavior, and Internet use and a decrease in physical activity. Female students and sexual and gender minority youth reported poorer mental health conditions. Further research is needed to clarify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on vulnerable subgroups of college students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Media Use and Mental Health among Young Adults

Social media and youth mental health.

What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

College students’ mental health has been an increasing concern. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought this vulnerable population into renewed focus. The pandemic has been an important stressor that may have compromised the mental health of college students and changed their lifestyles with significant consequences on their well-being and academic performance. Several studies have shown that college students present poorer mental health compared to their peers in the general population (Kang et al., 2021 ; Lovell et al., 2015 ), and the COVID-19 pandemic may have been a stressor that further worsened the mental health conditions of college students. However, the empirical link between COVID-19 pandemic and college students’ mental health has not been established clearly. Although many studies assess the effects of the pandemic on college students, no systematic reviews analyze the changes in their well-being and lifestyles over time. This study addresses this research gap by systematically reviewing the longitudinal studies that investigate the differences in college students’ mental health and lifestyles before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The worst mental health condition of college students, compared to their peers, seems to be related to the fact that college students are exposed to a high number of stressors. The academic career is a critical period of life that involves facing new and complex developmental challenges (Ruby et al., 2009 ). College students are in an uncomfortable position between family expectations, personal achievements, study, and work, and all these factors may contribute to the development or intensification of certain psychological illnesses (Hyun et al., 2007 ; Sharp & Theiler, 2018 ). During college years, students are also actively involved in a process of identity formation, influenced by contact with their peers (Adams et al., 2006 ; Luyckx et al., 2006 ), with important consequences on their self-esteem and psychological well-being (Cameron, 1999 ). Isolation and loneliness, as experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, can be a significant risk factor for good psychological development and for the mental health of adolescents and young adults (Acquah et al., 2016 ; Adam et al., 2011 ; Bozoglan et al., 2013 ; Chang et al., 2014 ; Christ et al., 2017 ; Muyan & Chang, 2015 ; Peltzer & Pengpid, 2017 ; Shen & Wang, 2019 ; Zawadzki et al., 2013 ).

Stressful life events also seem to be a factor that can contribute to the development of mental disorders (Cohen et al., 2019 ; Meyer-Lindenberg & Tost, 2012 ; Slavich, 2016 ). According to psychiatric epidemiological research, most high-prevalence mental disorders emerge during adolescence and early adulthood (de Girolamo et al., 2012 ; Kessler et al., 2007 ). As is shown by a recent systematic review of studies assessing differences in mental health among the general population before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, mental health problems increased during lockdown, although without a specific trend (Richter et al., 2021 ). Some studies have revealed a possible increase in mental health problems among college students during the pandemic (Deng et al., 2021 ), while other studies have found a decrease in psychological symptoms (Horita et al., 2021 ; Li et al., 2020b ; Rettew et al., 2021 ). Another important limitation of research on this topic has been its reliance on cross-sectional designs, which does not allow for displaying the evolution of mental health and lifestyle of students over time. Understanding the effects of the pandemic requires an overview of longitudinal studies to highlight changes in psychological symptoms, lifestyle, and well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to compare it to a baseline assessment before the restrictions were imposed.

Current Study

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a stressor that may have compromised the mental health of college students and changed their lifestyles with important consequences on their well-being. Although research has recognized the impact of COVID-19 on college students, longitudinal studies can contribute greater knowledge on this topic. This systematic review summarizes available data from longitudinal studies examining changes in mental health and lifestyle among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic.

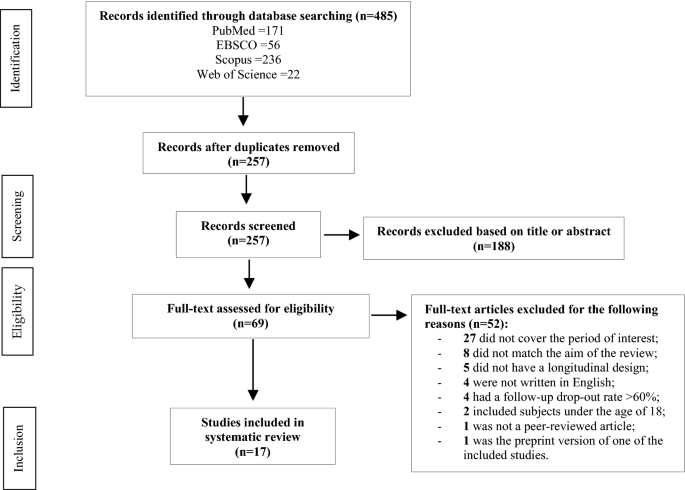

Protocol and Registration

This systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher et al., 2015 ). The protocol was registered with the Open Science Foundation (OSF) database. The protocol, which includes the research questions, detailed methods, and planned analyses for the review, can be accessed at the following URL: https://osf.io/m6hyg/ , https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/M6HYG (Date of registration: 31 May 2021).

Inclusion Criteria

This systematic review included longitudinal studies examining changes in mental health and lifestyle among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The term “change” is defined as any before-after difference reported in the mental health and lifestyle related variables investigated by the included studies. Data collected before January 2020 (for Wuhan and Hubei province, China), February 2020 (for the rest of China), and March 2020 (for the rest of the world) are considered “before” the COVID-19 pandemic. Data collected after those dates are considered “during” the COVID-19 pandemic.