- About the Hub

- Announcements

- Faculty Experts Guide

- Subscribe to the newsletter

Explore by Topic

- Arts+Culture

- Politics+Society

- Science+Technology

- Student Life

- University News

- Voices+Opinion

- About Hub at Work

- Gazette Archive

- Benefits+Perks

- Health+Well-Being

- Current Issue

- About the Magazine

- Past Issues

- Support Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Subscribe to the Magazine

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Credit: Adam Simpson

The Ethics of Self-Driving Cars

Self-driving cars have the potential to make roads safer. but what do we do while they learn from their mistakes.

By J. Cavanaugh Simpson

" Numerous arrests, flat tires, and confrontations with angry pedestrians failed to quench Willie's insatiable driving thirst. Many assumed the cars to be just a passing fad ." —Willie K. Vanderbilt II: A Biography, by Steven H. Gittelman

I n 1900, Willie K. Vanderbilt II, an early adopter of the motorcar, tore across New England in a 28-horsepower Daimler Phoenix he had nicknamed the White Ghost. At 22, this scion of the Vanderbilt railroad dynasty matched the locomotive speed record at the everyone-hang-on-tight pace of 60 mph. On the jaunt between Newport and Boston (2 hours, 47 minutes), he was fined by a Boston policeman for "scorching."

There were no speed limits. There soon would be.

The roadway antics of Vanderbilt and other prosperous drivers of "road engines" (they had to be prosperous—the White Ghost cost $10,000, or about $280,000 in current dollars) led to America's first speed limits, in Connecticut, enacted in 1901: 12 mph in cities and 15 mph on country roads. The restrictions were rarely heeded.

Three years later, Vanderbilt hosted one of America's first major international races: the Vanderbilt Cup on Long Island public roads. Bedecked in goggles and sheathed in dust, drivers in open-cockpit vehicles with spoked wheels and pneumatic tires sped around bends lined with spectators. During the race's second year, Swiss driver Louis Chevrolet crashed his Fiat into a telegraph pole and survived. A year later, a race spectator was hit and did not survive. Other fatalities followed. "The trail of dead and maimed left in the smoke makes it almost certain the mad exhibition of speed will be the last of its kind," reported the Chicago Daily Tribune .

Image caption: A dusty start to the Vanderbilt Cup race on October 24, 1908.

Image credit : Bain News Service / Wikimedia Commons

America avidly followed motorists like Vanderbilt, whose flashy new machines would set the pace for the century of the automobile—altering public safety, economies, and the way humans live. Though not without backlash. Biographer Gittelman writes that Vanderbilt's "racing down country roads invoked not awe but ire from the local citizenry," including farmers who lost horses, chickens, and pigs on rural byways. Drivers met with tacks and nails strewn across their path. "Other times it was upturned rakes and saws."

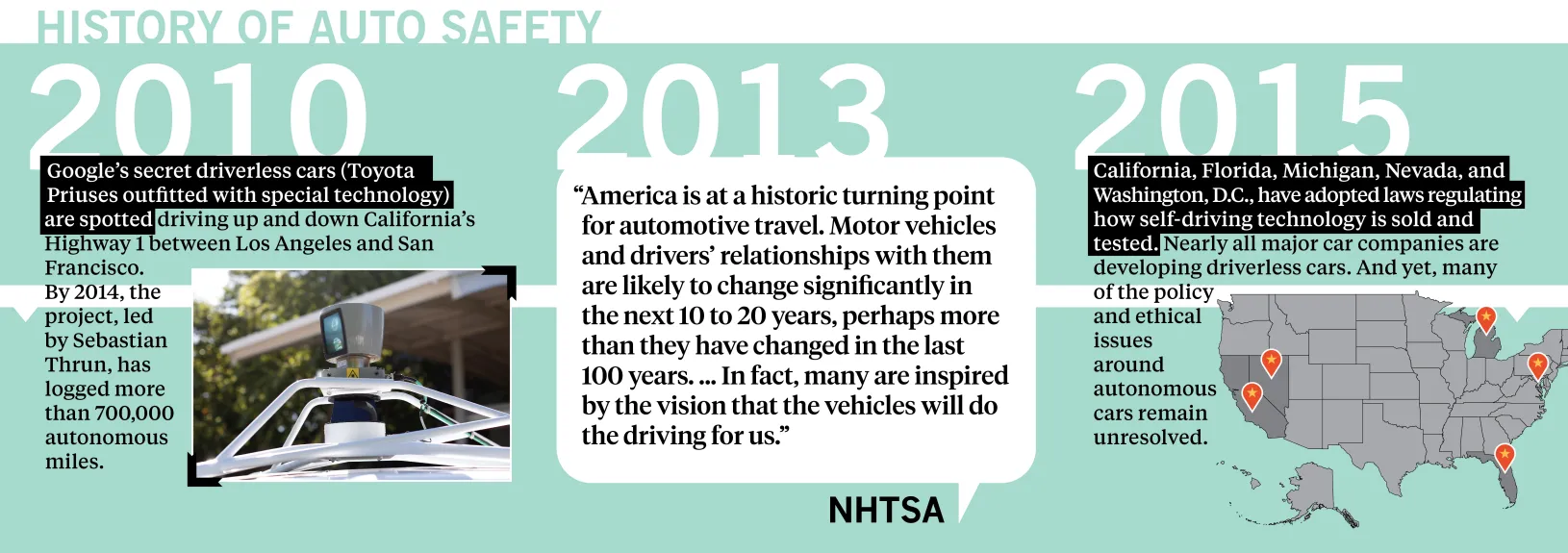

Today we are, like Vanderbilt, in the early days of an automotive technology transformation. Autonomous vehicles—or AVs—"may prove to be the greatest personal transportation revolution since the popularization of the personal automobile nearly a century ago," noted the U.S. Department of Transportation in the first Federal Automated Vehicles Policy in 2016, which suggested but did not require safety assessments.

When the motorcar arrived on the scene, an unsanctioned social experiment unfolded on public thoroughfares. Only after accidents and deaths did most regulation and safety measures follow. Now, a new wave of prosperous early adopters are beta testing AV technology—and venture-capital-fueled self-driving vehicles are honing their computerized skills on urban streets and highways—in yet another ad hoc experiment. The result: ethical dilemmas in safety, society, and culture. Question is, do we really need to reinvent the wheel on how best to adapt to what's coming, or can history offer some clues?

A utonomous vehicles could change societies across the globe, erasing millions of jobs while saving thousands of lives. Reconfiguring cities. Transforming economies. In what some term the early years of a Jetsonian dream, an autonomous vehicle revolution seems inevitable, at least to those investing lots of money and hope. A 2017 Brookings Institution report estimates recent investment in the AV industry at $80 billion, spearheaded by familiar competitors such as Ford, Mercedes-Benz, and General Motors, as well as Tesla, Google's Waymo, Uber, and China's Baidu. Fully self-driving vehicles, and those that augment a human driver with features like automated steering and braking, have been road tested or rolled out with limited restrictions in cities worldwide including Pittsburgh, Austin, Phoenix, San Francisco, Nashville, London, Paris, and Helsinki. In the U.S., a few states allow computers to be "drivers," at least to an extent, or vehicles that have no steering wheels or gas pedals.

Not without human cost. In March, pedestrian Elaine Herzberg , 49, of Tempe, Arizona, was hit by an Uber vehicle that had a driver but was operating in "autonomous mode." Following her death, Uber halted public road testing. The National Transportation Safety Board launched an investigation. Experts like Raj Rajkumar, co-director of the General Motors–Carnegie Mellon Autonomous Driving Collaborative Research Lab, urged a freeze on public road testing. "This isn't like a bug with your phone. People can get killed. Companies need to take a deep breath. The technology is not there yet," Rajkumar told Axios. "This is the nightmare all of us working in this domain always worried about."

As AV tech improves, there's an expectation among public health advocates and others that self-driving vehicles will eventually save many lives. Motor vehicle–related deaths in the U.S. hover above 35,000 annually. Various studies indicate more than 90 percent of traffic accidents are caused by human error, usually speeding or inattention. "Humans are better drivers than squirrels, but we're terrible drivers," lamented Jennifer Bradley, director of the Aspen Institute's Center for Urban Innovation, at a recent symposium at the Bloomberg School of Public Health .

AV development overall won't be stopped by the first pedestrian death—Bridget Driscoll was the first known pedestrian killed by a "horseless carriage," in London in 1896, less than two decades after Karl Benz debuted the first practical gasoline-powered vehicle, the one-cylinder, three-wheeled Motorwagen. The death of the 44-year-old mother didn't prevent Benz's invention from taking over roads worldwide.

Yet the first AV-related pedestrian death and other fatal accidents have prompted growing concern over unintended consequences. And now's likely the time to get ahead of the problems. Otherwise, few people will end up buying or trusting vehicles without human drivers. "There's a window of opportunity but it's not clear how quickly it's closing," says Jason Levine, executive director of the Center for Auto Safety , an independent nonprofit advocacy group. "We are at a moment of tremendous excitement, and there's potentially tremendous value to the tech but also consumer skepticism about its safety and utility."

Autonomous vehicle testing on public roads is nothing like how pharmaceutical "drugs or even children's toys are introduced to the public," Levine adds. "The hubris of putting this tech on roads in a way the average person has not given consent to raises a lot of questions."

Joshua Brown, who died in self-driving accident, tested limits of his Tesla

The ethics of autonomous cars, autonomous trucks will haul your stuff before you ride in a self-driving car, for a much-needed win, self-driving cars should aim lower.

To foster possibly safer scenarios, and with computer-driven cars already en route (Waymo, in particular, reports that it has logged 5 million test miles on public roads), ethical frameworks are emerging. Researchers in public health and engineering at Johns Hopkins and elsewhere are seeking guideposts such as shared incident databases, or studying how humans interact with the vehicles (to avoid, for example, human drivers drifting off to sleep in a car that's not fully autonomous, so they are unable to take over if needed, what's been termed a "fatal nap").

In December, in the Bloomberg School of Public Health's Sheldon Hall, ethics underscored " The Future of Personal Transportation: Safe and Equitable Implementation of Autonomous Vehicles—A Conversation on Public Health Action ," co-sponsored by the Johns Hopkins Center for Injury Research and Policy . Panelists discussed how autonomous vehicles might ease "transportation deserts" in cities but add to the "slothification" of people who won't walk if a self-driving urban podcar awaits. There were equity questions. "Will the technology be affordable?" asked Keshia Pollack Porter, a professor and director of the Bloomberg School's Institute for Health and Social Policy. A probable social consequence—job loss—prompted calls to action. A PowerPoint map indicating that tractor-trailer and delivery driving is a top occupation in 29 U.S. states drew gasps: Many of the nation's more than 3.5 million professional trucking jobs would likely disappear if tractor-trailers were to drive themselves.

The U.S. needs to make a major social commitment, researchers said, including transitional job training and education. "Many times over in human history, tech innovation has meant that machines have replaced humans," says Nancy Kass , a professor of bioethics and public health and a deputy director at the university's Berman Institute of Bioethics . "I'm not sure we in the United States are a model for committing to the human beings who are being replaced."

T ech developers have warned that stringent regulation of AV inventions could hamper innovation. Until recent accidents, members of Congress seemed to agree—for example, supporting bills to exempt up to 100,000 autonomous vehicles per manufacturer from federal safety regulations. Should society simply wait and see how that all goes? A group of Johns Hopkins researchers doesn't think so, and recently won a grant from the Berman Institute's JHU Exploration of Practical Ethics program. On a Tuesday in Hampton House Café at Johns Hopkins' East Baltimore campus, Johnathon Ehsani , an assistant professor of health policy and management, and Tak Igusa , a professor of civil engineering, described the aims of the project and related research. Society is "figuring it out as we go along," Ehsani said. "There's the ethical behavior of the machine, and that captures the popular imagination. 'Is the car I buy going to kill me or other people?' And there are situations in which the vehicle would make ethical decisions.

"Yet as safety experts, our unique contribution seems to lie in how we can shepherd a safe and efficient deployment," Ehsani said. "How can we balance public safety concerns with the potential benefits this will bring society?"

Experts are analyzing roadway crash data to identify things like problematic intersections, to help guide AVs to less tricky routes that allow for sensors and software to gradually become more sophisticated. "In many ways, an autonomous vehicle is like a teenage driver. When you first start going out, you take them out only in parking lots or on quiet residential streets where you know they'll be safe," Ehsani explained.

Regarding safety, two issues seem paramount: 1) how to program self-driving cars to make their own lightning-fast decisions just before a crash, which may require prioritizing some lives over others; and 2) the ethical questions raised by testing software and sensors on public streets—to develop computerized motion control, path planning, or perception—potentially putting people at unnecessary risk. As Drexel University researcher Janet Fleetwood wrote in a seminal 2017 article in the American Journal of Public Health , programmers "recognize that the vehicles are not perfect and will not be anytime soon. What are we to do in the interim while the autonomous vehicles are learning from their mistakes?"

Video credit : TED-Ed

The prospect of robotic car decision making has meant revisiting a thought experiment known as the trolley problem. Imagine a run-away trolley. Five people are tied to the trolley tracks. If you pull a lever, the trolley switches to a different track where there's only one person in harm's way. Do you let the five be killed incidentally, or pull the lever, diverting the trolley and saving them but deliberately killing the one? "The trolley problem is taught in every philosophy class because it doesn't have a clear answer morally," Kass says. "It might behoove a company to do public engagement around this issue on how to program the cars, to determine what most people want—or at least have people understand the trade-offs at stake."

With AV tech being so new, there are many unknowns, but for likely crash situations, human programmers might code such decisions via a forced-choice algorithm: The car's computer would be forced to select, for example, whether to hit a pedestrian or swerve, striking another vehicle or a concrete wall, saving the pedestrian but potentially killing the driver. Although the need for "a forced-choice algorithm may arise infrequently on the road, it is important to analyze and resolve," researcher Fleetwood wrote. Human drivers have long made such last-second decisions. Yet how do we pre-program a "correct" option, or let AI machine learning determine "crash optimization" based on a code of conduct built into the software? "You could say you have a public health responsibility to protect pedestrians," Kass says. "Yet it's not an unreasonable expectation that people buy a car that would keep them [as passengers] safe."

This dilemma remains a substantial barrier to humans ceding control. Among other studies, in a survey of 2,000 people—by researchers at the University of Oregon, the Toulouse School of Economics in France, and MIT Media Lab titled " The Social Dilemma of Autonomous Vehicles "—respondents initially favored a utilitarian morality: that an autonomous vehicle should strive to save the most people. Yet would they buy an AV that prioritized strangers over themselves or their families? The general response: No.

J oshua Brown adored his Tesla Model S, which he named "Tessy." Brown, a former Navy SEAL, made YouTube videos of himself driving no-hands via Autopilot, the semi-autonomous option that controlled his sedan's speed and steering within lanes. Tesla founder Elon Musk tweeted one of those video clips. Brown, 40, later told a neighbor, according to The New York Times , "For something to catch Elon Musk's eye, I can die and go to heaven now."

A few weeks after Musk's tweet in 2016, on a sunny day near Williston, Florida, Brown engaged Autopilot. A National Transportation Safety Board report later revealed the driver's hands remained off the wheel for all but 25 seconds of a 37-minute drive. An alarm sounded six times because his hands were disengaged. Since he did this often, such notification chimes, what some drivers call a "nag," might have become for him mere background noise that he ignored.

When a white semitrailer turned in front of him, his Tesla smashed into it in an explosion of white metal and dust. The NTSB report linked the fatal crash to human error, yet criticized Tesla for systemic concerns , giving "far too much leeway to the driver to divert his attention to something other than driving." Following Brown's death, Tesla updated the software to disable Autopilot after the no-hands alarm sounds for the third time.

Could designers have predicted that Brown would, like Vanderbilt and other auto enthusiasts, push the limits of a cutting-edge machine? "The fact that the driver went so long with his hands off the wheel shouldn't come as a complete surprise," said Jake Fisher, Consumer Reports auto testing director, after the NTSB report. "If a car can physically be driven hands-free, it's inevitable that some drivers will use it that way."

Some argue that AV pioneers end up putting people at risk who haven't chosen to participate in the experiment. "We are going forward a little too fast, and there are no guardrails," says auto safety advocate Levine. "Not taking action as a society until it's abundantly clear there is danger would unfortunately be a repetition of past mistakes."

Image caption: Pictured above is the first traffic light to be installed and operated in Bucharest

Image credit : The Library of the Romanian Academy / Wikimedia Commons

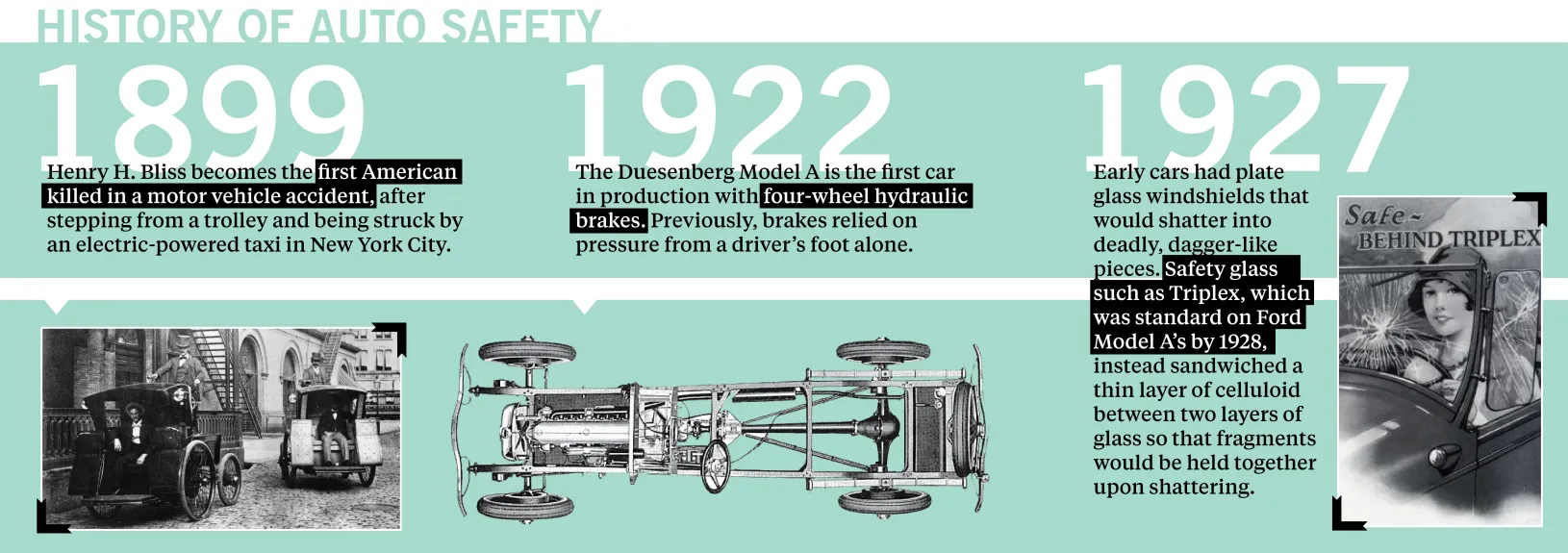

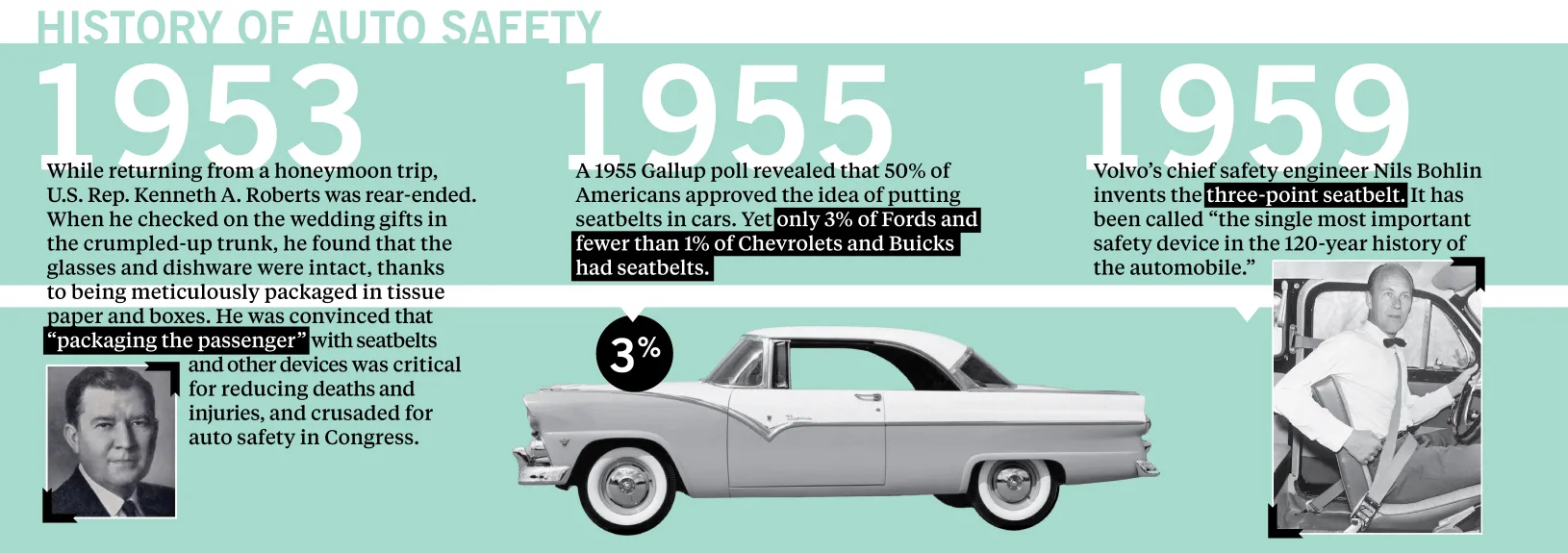

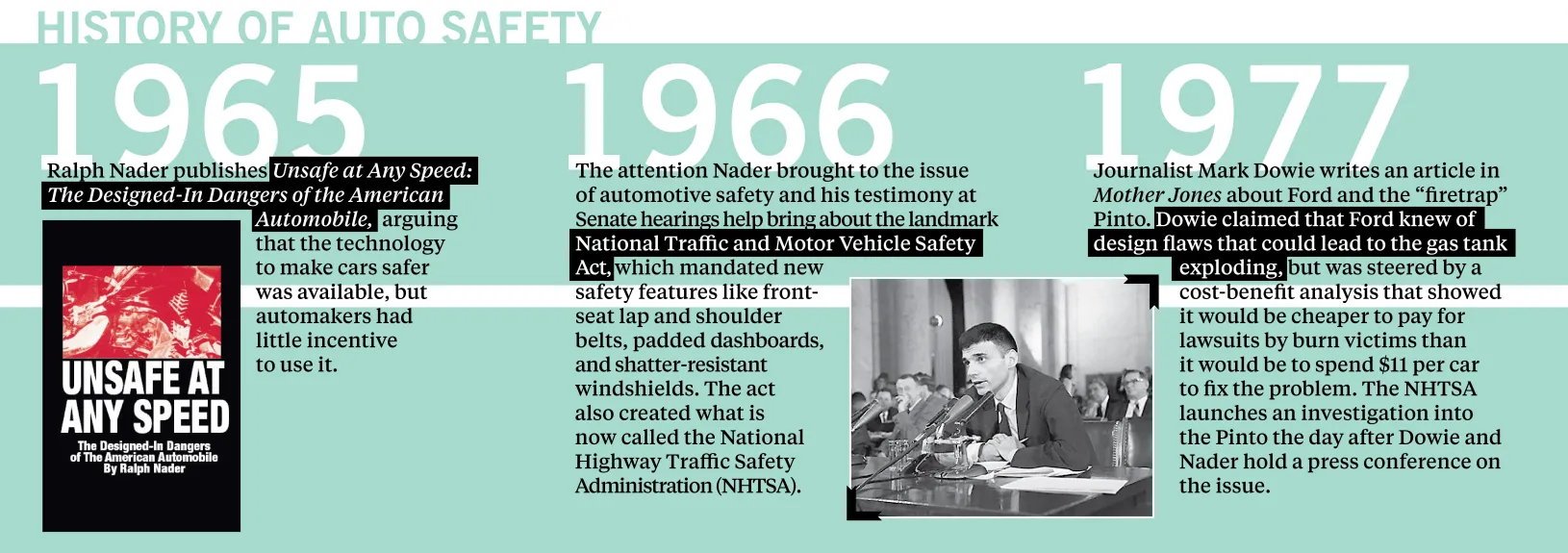

In the first automotive era, collateral damage indeed ensued. In 1900, America counted 8,000 vehicles. By the early 1920s, vehicle numbers hit 10 million, federal records show. Drunk driving, drag racing, and hit-and-run incidents also rose, and U.S.-tracked motor vehicle fatalities mushroomed from just 36 in 1900 to more than 20,000 by 1925. Only after such chaos did most safety measures—including traffic lights, driver's licenses, uniform signage, shatterproof windshields—result, mostly starting in the early 1930s, nearly three decades after the popularization of the car.

As safety plays out today, regulators could proactively require, for example, AV sensor standards; proof of safety testing; clearly visible warnings of limitations (much like airbag warnings); mandatory incident and data reporting and sharing; and road signage notifying people of testing, experts note. "There are no electronic standards. No cybersecurity standards. No baseline metric that self-driving vehicles meet X standard," Levine says. "There's no national framework around autonomous vehicle technology to minimize potential for damage."

Rigorous safety monitoring would be top priority, Kass says. And other testing templates could be adapted, such as some used for pharmaceuticals. "In drug testing there's a Stopping Rule: If you see a rate of adverse effects above a certain predetermined threshold, you call things off. And thinking about that threshold in advance is important," she says. "We as human beings tend to rationalize and justify: 'Well, we don't really think it's a problem. Or, the benefits outweigh the risks.'" Safety test rules can foster essential objectivity.

Entrepreneurs racing for market dominance tend to protect trade secrets, yet sharing incident reports and solutions could prove financially beneficial—much like the Federal Aviation Administration incident databases and the collaborative Commercial Aviation Safety Team that record data, detect risk, and come up with prevention strategies. "A crash for one autonomous vehicle company is bad business for all of them," Ehsani says.

Federal regulators and Congress will likely need to set AV safety and onboard tech standards. Yet anticipating outcomes can prove complex. Safety experts cite lessons from the history of vehicle airbags: Touted as lifesaving, vehicle airbags were installed mostly starting in 1993. By 1996, airbag deployments had caused 25 deaths among children, prompting public outrage. The auto industry had installed high-powered bags designed to shield a 160-pound, nearly 6-foot-tall person. Federal agencies later determined that the tech had not been sufficiently tested on children and smaller adults. After so many fatal accidents, newer "depowered" airbags and highly visible warnings against placing children in front seats resulted, though even those measures took a few years and airbag safety recalls continue.

A global perspective might make a difference. While both America and Europe dominated early automobile innovation, a philosophical split led Europeans to emphasize a "precautionary principle": If there's potential for significant risk of human harm, proceed slowly.

Overall, the United States "tends to privilege entrepreneurial thinking, and people credit the United States for being the engine of discovery," Kass notes. "It's a climate that is conducive to this: more cowboy, less precautionary, less risk averse."

A utonomous vehicles could bring societywide change even more complex than coding a vehicle's moral compass. Potential public health benefits could be impressive: Drunk driving and overall traffic injuries would likely decline; older drivers could increase their mobility and alleviate depression or mental decline with better access to doctors' offices, groceries, and events. At the same time, however, stretched public transportation funds might be siphoned away from buses or light rail. Some states "will want to put in infrastructure for autonomous vehicle lanes," Ehsani says. "It's a good idea now to think: Would the public have benefited more from investment in public transportation? Will the least advantaged be worse off?"

If popularized, self-driving vehicles could remake American cities and suburbs. On the upside, fewer parking lots might be needed for 24-hour shared vehicles, fostering greener urban areas. Yet cities would lose revenue from parking meters, garages, and citations, forcing higher taxes. (Such city parking revenue is not small change. San Francisco brings in $130 million annually.) Self-driving vehicles could also exacerbate suburban sprawl, as people might live farther out if they can text-and-scroll all the way to work.

Yet the biggest societal shift might be what happens to sustainable livelihoods. A projected decimation of delivery, taxi, and especially truck driving jobs seems the most alarming. America is currently facing a truck driver shortage, and some experts predict automated steering and other driver-assist tech might actually enhance trucking safety, drawing more drivers. Yet other experts say that as AI advances, humans won't be needed. And, since computers or robots don't require sleep or food, a ripple effect would hit supporting industries: restaurants, truck stops, and hotels, affecting millions more. Some truckers could transition to other well-paid jobs, which likely need training, licenses, or certifications, such as firefighters, commercial pilots, or charter boat captains. IT-trained humans could troubleshoot a semi's computer glitches. At the end of the day, however, there's no convincing solution, as similar declines have been faced in the coal and steel industries. The breadth of this transformation might require progressive action.

"With predictions of an enormous impact—millions of jobs and millions of Americans affected—there's an analogy to what happened [during] the Industrial Revolution. With autonomous vehicles, there are positive public health, safety, and environmental outcomes but also human consequences with job loss," Kass says. "Large numbers of Americans are disrupted by something significant—disproportionately affecting those with a high school education or less. A government function would be to identify strategies to help people transition." Kass suggests such measures as federal incentives, taxation, and investment in job training.

Economic adaptations can evolve alongside new technologies, and history again offers a few clues. When motorcars started chugging in the late 1800s, someone quickly had to figure out how to fix them. An economic boon resulted. Among the wealthy, longtime carriage drivers sometimes became "chauffeur mechanics." Vanderbilt, for example, toured Europe in the early 1900s, logging 26 punctured tires, over-heated radiators, broken brake shoes, and locked-up carburetors, fixed mostly by his shot-gun-seat mechanic "Mr. Payne." Articles in the early motorcar journal Horseless Carriage Gazette recommended drivers carry wrenches, hammers, pliers, wire, and a ball of twine for roadside repairs. Across the nation, a growing number of vehicles needed regular repair (especially after Henry Ford produced the more affordable Model T in 1908). Varied craftspeople adapted their skill sets: blacksmiths, bicycle mechanics, electricians, plumbers, carriage makers, and machinists. "The invention and commercialization of automobile technology created the automobile mechanic's occupation de novo ," wrote Kevin L. Borg in Auto Mechanics: Technology and Expertise in Twentieth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007). A training economy was born—YMCA courses, World War I training centers, and later high school auto shops—that quickly proved lucrative. Take New York's West Side YMCA "auto school." "Receipts for the 1905 calendar year totaled nearly twenty thousand dollars, swamping the income generated by all the other courses," Borg wrote. "Many young Americans rushed to embrace the new technology."

Today, tech-enthralled youth might answer a similar call for higher paying IT-mechanic jobs. A February article in Automotive News posed: "Who will repair and maintain these robotic and technological marvels?" Via engineering firm Robert Bosch's internship program in Plymouth, Michigan, community college electronics students have received training with "software and electrical integration of sensors in automated vehicle prototypes." (In regard to tech entrepreneur lineage, the company's founder was a younger contemporary of Benz and a colleague of inventor Thomas A. Edison. In 1886, Bosch, an electrical engineer, opened a precision mechanics workshop in Germany the same year a patent was awarded for Benz Patent Motor Car, Model No. 1.)

T he early automobile, and the romantic recklessness of drivers like Vanderbilt, prompted nothing less than a cultural earthquake, shaking loose a new modernity and sense of personal agency—power, speed, freedom, and control—which seems at odds with self-driving cars. Does such a legacy matter?

T.E. Schlesinger , Johns Hopkins Whiting School of Engineering dean and professor of electrical and computer engineering, grew up in Canada just across the border from Detroit. He's among those who understand the cult of the car: "The human relationship with the automobile is special. People love their cars. People write songs about cars. People don't write songs about their toasters or their TVs." There's the freedom to go where you want to go, to drive down the open road. "If we have autonomous vehicles, will we be able to do that? What is that relationship?"

Overall, the future of autonomous vehicles depends on what humans desire from their modes of transport, and the risks or benefits they glimpse on the horizon. Schlesinger, a founding co-director of the General Motors–Carnegie Mellon collaborative lab, welcomes potentially safer roadways and thinks auto culture will adapt: "All bets are off on design." Cars have resembled a carriage, with an engine in front where the horse used to be, he says. "The driver is sitting there to hold the 'reins.'" A truly self-driving vehicle could resemble "a game room or a virtual reality environment."

Other drivers aren't so sure. At a classic car show 20 minutes north of Johns Hopkins' Homewood campus, restored cars, some from Vanderbilt's era, fill a parking lot beside another tribute to beloved machinery, the Fire Museum of Maryland. Members of the Chesapeake region Antique Automobile Club of America, founded 63 years ago, display vehicles ranging from a shiny black Model T to an elegant 1930s Packard with whitewall tires, from a baby blue 1950s Chevy to a sleek 1970s Corvette Stingray.

Three longtime classic car owners sit in the shade of a tree. When asked about the specter of autonomous cars, they seem resigned. "In 1903, people resisted automobiles," says Al Zimmerman. "They said they would never work. That people would always ride horses."

Norm Heathcote, chapter president, jokes that his wife would likely prefer riding in an autonomous car, instead of having him at the wheel, especially of his maroon 1950 Ford coupe: "With a car that drives itself, she would probably feel a whole lot better." Car colleague Ken Stevenson worries about increasing tech reliance, and the men discuss threats to privacy, such as vehicle software hackers, internet-connected cars, and GPS. "I like a map," Stevenson says. "GPS just makes me feel dumb."

Driving today has already forfeited much of the original thrill, Zimmerman adds: "Modern automobiles versus old cars is already like night and day. Now you just drive along. All you do is aim a little bit. Autonomous cars are not much different."

In the end, what will become of the rebellious American-style independence the automobile has long represented? "Will you be able to light up?" Heathcote asks. Light up? He means: Burn out. Smoke the tires. "Smoke 'em if you got 'em."

J. Cavanaugh Simpson, A&S '97 (MA), is an essayist and a lecturer in the Johns Hopkins Writing Seminars.

Posted in Health , Science+Technology , Politics+Society

Tagged berman institute of bioethics , ethics , driverless cars , autonomous vehicles

Related Content

On the road to safety

You might also like, news network.

- Johns Hopkins Magazine

- Get Email Updates

- Submit an Announcement

- Submit an Event

- Privacy Statement

- Accessibility

Discover JHU

- About the University

- Schools & Divisions

- Academic Programs

- Plan a Visit

- my.JohnsHopkins.edu

- © 2024 Johns Hopkins University . All rights reserved.

- University Communications

- 3910 Keswick Rd., Suite N2600, Baltimore, MD

- X Facebook LinkedIn YouTube Instagram

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Should Self-Driving Cars Have Ethics?

Laurel Wamsley

New research explores how people think autonomous vehicles should handle moral dilemmas. Here, people walk in front of an autonomous taxi being demonstrated in Frankfurt, Germany, last year. Andreas Arnold/Bloomberg via Getty Images hide caption

New research explores how people think autonomous vehicles should handle moral dilemmas. Here, people walk in front of an autonomous taxi being demonstrated in Frankfurt, Germany, last year.

In the not-too-distant future, fully autonomous vehicles will drive our streets. These cars will need to make split-second decisions to avoid endangering human lives — both inside and outside of the vehicles.

To determine attitudes toward these decisions a group of researchers created a variation on the classic philosophical exercise known as " the Trolley problem ." They posed a series of moral dilemmas involving a self-driving car with brakes that suddenly give out: Should the car swerve to avoid a group of pedestrians, killing the driver? Or should it kill the people on foot, but spare the driver? Does it matter if the pedestrians are men or women? Children or older people? Doctors or bank robbers?

To pose these questions to a large range of people, the researchers built a website called Moral Machine , where anyone could click through the scenarios and say what the car should do. "Help us learn how to make machines moral," a video implores on the site.

The grim game went viral, multiple times over.

"Really beyond our wildest expectations," says Iyad Rahwan, an associate professor of Media Arts and Sciences at the MIT Media Lab, who was one of the researchers. "At some point we were getting 300 decisions per second."

What the researchers found was a series of near-universal preferences, regardless of where someone was taking the quiz. On aggregate, people everywhere believed the moral thing for the car to do was to spare the young over the old, spare humans over animals, and spare the lives of many over the few. Their findings, led by by MIT's Edmond Awad, were published Wednesday in the journal Nature.

Author Interviews

What happens when a.i. takes the wheel.

Using geolocation, researchers found that the 130 countries with more than 100 respondents could be grouped into three clusters that showed similar moral preferences. Here, they found some variation.

For instance, the preference for sparing younger people over older ones was much stronger in the Southern cluster (which includes Latin America, as well as France, Hungary, and the Czech Republic) than it was in the Eastern cluster (which includes many Asian and Middle Eastern nations). And the preference for sparing humans over pets was weaker in the Southern cluster than in the Eastern or Western clusters (the latter includes, for instance, the U.S., Canada, Kenya, and much of Europe).

And they found that those variations seemed to correlate with other observed cultural differences. Respondents from collectivistic cultures, which "emphasize the respect that is due to older members of the community," showed a weaker preference for sparing younger people.

Maddie About Science

Watch: self-driving cars need to learn how humans drive.

Rawhan emphasized that the study's results should be used with extreme caution, and they shouldn't be considered the final word on societal preferences — especially since respondents were not a representative sample. (Though the researchers did conduct statistical correction for demographic distortions, reweighing the responses to match a country's demographics.)

What does this add up to? The paper's authors argue that if we're going to let these vehicles on our streets, their operating systems should take moral preferences into account. "Before we allow our cars to make ethical decisions, we need to have a global conversation to express our preferences to the companies that will design moral algorithms, and to the policymakers that will regulate them," they write.

But let's just say, for a moment, that a society does have general moral preferences on these scenarios. Should automakers or regulators actually take those into account?

Last year, Germany's Ethics Commission on Automated Driving created initial guidelines for automated vehicles. One of their key dictates? A prohibition against such decision-making by a car's operating system.

No Driver Input Detected In Seconds Before Deadly Tesla Crash, NTSB Finds

"In the event of unavoidable accident situations, any distinction between individuals based on personal features (age, gender, physical or mental constitution) is strictly prohibited," the report says. "General programming to reduce the number of personal injuries may be justifiable. Those parties involved in the generation of mobility risks must not sacrifice non-involved parties."

But to Daniel Sperling, founding director of the Institute of Transportation Studies at University of California – Davis and author of a book on autonomous and shared vehicles , these moral dilemmas are far from the most pressing questions about these cars.

"The most important problem is just making them safe," he tells NPR. "They're going to be much safer than human drivers: They don't drink, they don't smoke, they don't sleep, they aren't distracted." So then the question is: How safe do they need to be before we let them on our roads?

- artificial intelligence

- self-driving cars

- autonomous vehicles

Loyola University > Center for Digital Ethics & Policy > Research & Initiatives > Essays > Archive > 2018 > Self-Driving Car Ethics

Self-driving car ethics, october 10, 2018.

Earlier this spring 49-year-old Elaine Herzberg was walking her bike across the street in Tempe, Ariz., when she was hit and killed by a car traveling at over 40 miles an hour.

There was something unusual about this tragedy: The car that hit Herzberg was driving on its own. It was an autonomous car being tested by Uber.

It’s not the only car crash connected to autonomous vehicles (AVs) as of late. In May, a Tesla on “autopilot” mode accelerated briefly before hitting the back of a fire truck, injuring two people.

The accidents unearthed debates that have long been simmering around the ethics of self-driving cars. Is this technology really safer than human drivers? How do we keep people safe while this technology is being developed and tested? In the event of a crash, who is responsible: the developers who create faulty software, the human in the driver’s seat who fails to recognize the system failure, or one of the hundreds of other hands that touched the technology along the way?

The need for driving innovation is clear: Motor vehicle deaths topped 40,000 in 2017 according to the National Safety Council. A recent study by RAND Corporation estimates that putting AVs on the road once the technology is just 10 percent better than human drivers could save thousands of lives. Industry leaders continue to push ahead with development of AVs: Over $80 billion has been invested so far in AV technology, the Brookings Institute estimated . Top automotive, rideshare and technology companies including Uber, Lyft, Tesla, and GM have self-driving car projects in the works. GM has plans to release a vehicle that does not need a human driver--and won’t even have pedals or a steering wheel--by 2019.

But as the above crashes indicate, there are questions to be answered before the potential of this technology is fully realized.

Ethics in the programming process

Accidents involving self-driving cars are usually due to sensor error or software error, explains Srikanth Saripalli, associate professor in mechanical engineering at Texas A&M University, in The Conversation . The first issue is a technical one: Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR) sensors won’t detect obstacles in fog, cameras need the right light, and radars aren’t always accurate. Sensor technology continues to develop, but there is still significant work needed for self-driving cars to drive safely in icy, snowy and other adverse conditions. When sensors aren’t accurate, it can cause errors in the system that likely wouldn’t trip up human drivers. In the case of Uber’s accident, the sensors identified Herzberg (who was walking her bike) as a pedestrian, a vehicle and finally a bike “with varying expectations of future travel path,” according to a National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) preliminary report on the incident. The confusion caused a deadly delay--it was only 1.3 seconds before impact that the software indicated that emergency brakes were needed.

Self-driving cars are programmed to be rule-followers, explained Saripalli, but the realities of the road are usually a bit more blurred. In a 2017 accident in Tempe, Ariz., for example, a human-driven car attempted to turn left through three lanes of traffic and collided with a self-driving Uber. While there isn’t anything inherently unsafe about proceeding through a green light, a human driver might have expected there to be left-turning vehicles and slowed down before the intersection, Saripalli pointed out. “Before autonomous vehicles can really hit the road, they need to be programmed with instructions about how to behave when other vehicles do something out of the ordinary,” he writes.

However, in both the Uber accident that killed Herzberg and the Tesla collision mentioned above, there was a person behind the wheel of the car who wasn’t monitoring the road until it was too late. Even though both companies require that drivers keep their hands on the wheel and eyes on the road in case of a system error, this is a reminder that humans are prone to mistakes, accidents and distractions--even when testing self-driving cars. Can we trust humans to be reliable backup drivers when something goes wrong?

Further, can we trust that companies will be thoughtful--and ethical--about the expectations for backup drivers in the race for miles? Backup drivers who worked for Uber told CityLab that they worked eight to ten hour shifts with a 30 minute lunch and were often pressured to forgo breaks. Staying alert and focused for that amount of time is already challenging. With the false security of self-driving technology, it can be tempting to take a quick mental break while on the road. “Uber is essentially asking this operator to do what a robot would do. A robot can run loops and not get fatigued. But humans don’t do that,” an operator told CityLab.

The limits of the trolley scenario

Despite the questions that these accidents raise about the development process, the ethics conversation up to this point has largely been focused on the moment of impact. Consider the “ trolley problem ,” a hypothetical ethical brain teaser frequently brought up in the debate over self-driving cars. If an AV is faced with an inevitable fatal crash, whose life should it save? Should it prioritize the lives of the pedestrian? The passenger? Saving the most lives? Saving the lives of the young or elderly?

Ethical questions abound in every engineering and design decision, engineering researchers Tobias Holstein, Gordana Dodig-Crnkovic and Patrizio Pelliccione argue in their recent paper, Ethical and Social Aspects of Self-Driving Cars , ranging from software security (can the car be hacked?) to privacy (what happens to the data collected by the car sensors?) to quality assurance (how often does a car like this need maintenance checks?). Furthermore, the researchers note that some ethics are directly at odds with the private industry’s financial incentives: Should a car manufacturer be allowed to sell cheaper cars outfitted with cheaper sensors? Could a customer choose to pay more for a feature that lets them influence the decision-making of the vehicle in fatal situations? How transparent should the technology be, and how will that be balanced with intellectual property that is vital to a competitive advantage?

The future impact of this technology hinges on these complex and bureaucratic “mundane ethics,” points out Johannes Himmelreich, interdisciplinary ethics fellow at Stanford University in The Conversation . We need to recognize that big moral quandaries don’t just happen five seconds before the point of impact, he writes. Programmers could choose to optimize acceleration and braking to reduce emissions or improve traffic flow. But even these decisions pose big questions for the future of society: Will we prioritize safety or mobility? Efficiency or environmental concerns?

Ethics and responsibility

Lawmakers have already begun making these decisions. State governments and municipalities have scrambled to play host to the first self-driving car tests, in hopes of attracting lucrative tech companies, jobs and an innovation-friendly reputation. Arizona governor Doug Ducey has been one of the most vocal proponents, welcoming Uber when the company was kicked out of San Francisco for testing without a permit.

Currently there is a patchwork of laws and executive orders at the state level that regulate self-driving cars. Varying laws make testing and the eventual widespread roll-out more complicated and, as it is, it is likely that self-driving cars will need a completely unique set of safety regulations. Outside of the US, there has been more concrete discussion. Last summer Germany adopted the world’s first ethical guidelines for driverless cars. The rules state that human lives must take priority over damage to property and in the case of unavoidable human accident, a decision cannot be made based on “age, gender, physical or mental constitution,” among other stipulations.

There has also been discussion as to whether consumers should have the ultimate choice over AV ethics. Last fall, researchers at the European University Institute suggested the implementation of an “ ethical knob ,” as they call it, in which the consumer would set the software’s ethical decision-making to altruistic (preference for third parties), impartial (equal importance to all parties) or egoistic (preference for all passengers in the vehicle) in the case of an unavoidable accident. While their approach certainly still poses problems (a road in which every vehicle prioritizes the safety of its own passengers could create more risk), it does reflect public opinion. In a series of surveys , researchers found that people believe in utilitarian ethics when in comes to self-driving cars--AVs should minimize casualties in the case of an unavoidable accident--but wouldn’t be keen on riding in a car that would potentially value the lives of multiple others over their own.

This dilemma sums up the ethical challenges ahead as self driving technology is tested, developed and increasingly driving next to us on the roads. The public wants safety for the most people possible, but not if it means sacrificing one’s own safety or the safety of loved ones. If people will put their lives in the hands of sensors and software, thoughtful ethical decisions will need to be made to ensure a death like Herzberg’s isn’t inevitable on the journey to safer roads.

Karis Hustad is a Denmark-based freelance journalist covering technology, business, gender, politics and Northern Europe. She previously reported for The Christian Science Monitor and Chicago Inno . Follow her on Twitter @karishustad and see more of her work at karishustad.com .

Research & Initiatives

Return to top.

- Support LUC

- Directories

- Email Sakai Kronos LOCUS Employee Self-Service OneDrive Password Self-Service More Resources

- Symposia Archive

- Upcoming Events

- Past Events

- Publications

- CDEP in the News

© Copyright & Disclaimer 2024

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

The self-driving car revolution reached a momentous milestone with the U.S. Department of Transportation’s release in September 2016 of its first handbook of rules on autonomous vehicles .

Many members of the Stanford community are debating ethical issues that will arise when humans turn over the wheel to algorithms. (Image credit: AlealL / Getty Images)

Discussions about how the world will change with driverless cars on the roads and how to make that future as ethical and responsible as possible are intensifying.

Some of these conversations are taking place at Stanford. The topic of ethics and autonomous cars will be discussed during a free live taping of an episode of Philosophy Talk , a nationally syndicated radio show co-hosted by professors Ken Taylor and John Perry , on Wednesday, May 24, at the Cubberley Auditorium.

Stanford News Service talked to several Stanford scholars for their insights on the most significant ethical questions and concerns when it comes to letting algorithms take the wheel.

Trolley problem debated

A common argument on behalf of autonomous cars is that they will decrease traffic accidents and thereby increase human welfare. Even if true, deep questions remain about how car companies or public policy will engineer for safety.

“Everyone is saying how driverless cars will take the problematic human out of the equation,” said Taylor, a professor of philosophy. “But we think of humans as moral decision-makers. Can artificial intelligence actually replace our capacities as moral agents?”

That question leads to the “trolley problem,” a popular thought experiment ethicists have mulled over for about 50 years, which can be applied to driverless cars and morality.

In the experiment, one imagines a runaway trolley speeding down a track which has five people tied to it. You can pull a lever to switch the trolley to another track, which has only one person tied to it. Would you sacrifice the one person to save the other five, or would you do nothing and let the trolley kill the five people?

Engineers of autonomous cars will now have to tackle this question and other, more complicated scenarios, said Taylor and Rob Reich , the director of Stanford’s McCoy Family Center for Ethics in Society .

“It won’t be just the choice between killing one or killing five,” said Reich, who is also a professor of political science. “Will these cars optimize for overall human welfare, or will the algorithms prioritize passenger safety or those on the road? Or imagine if automakers decide to put this decision into the consumers’ hands, and have them choose whose safety to prioritize. Things get a lot trickier.”

Minimizing risk

But Stephen Zoepf , executive director of the Center for Automotive Research at Stanford (CARS) , along with several other Stanford scholars, including mechanical engineering Professor Chris Gerdes , argue that agonizing over the trolley problem isn’t helpful.

“It’s not productive,” Zoepf said. “People make all sorts of bad decisions. If there is a way to improve on that with driverless cars, why wouldn’t we?”

Zoepf said the more important ethical question is what is the level of risk society would be willing to incur with self-driving cars on the road. For the past several months, Zoepf and his CARS colleagues have been working on a project on ethical programming of automotive vehicles.

“We say, ‘let’s look at the tradeoffs inherent in safety and mobility,’” Zoepf said. “Should there be a designated right of way for automated vehicles, for example, or how fast should we permit automated vehicles to travel?”

Loss of jobs

Another ethical concern is the number of jobs that will be lost if self-driving vehicles become the norm, Taylor and Reich said.

More than 3.5 million truck drivers haul cargo on U.S. roads, according to the latest statistics by the American Trucking Associations , a trade association for the U.S. trucking industry.

“You can’t outsource driving,” Taylor said. “Technology has always destroyed jobs but created other jobs. But with the current technology revolution, things may look differently.”

Technological developments can cause the loss of jobs. But tech companies and governments can and must take steps to prepare for those losses, said Margaret Levi , professor of political science and the director of the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences .

“We have to be prepared for this job loss and know how to deal with it,” Levi said. “That’s part of the ethical responsibility of society. What do we do with people who are displaced? But it is not only the transformation in labor. It is also the transformation in transport, private and public. We must plan for that, too.”

Transparency and collaboration

Some scholars have also pointed out the need for greater transparency in the design of driverless cars.

“Should it be transparent how the algorithms of these cars are made?” Reich said. “The public interest is at stake, and transparency is an important consideration to inform public debate.”

But no matter their stance on a particular issue with self-driving cars, the scholars agree that there needs to be greater collaboration among disciplines in the development stage of this and other revolutionary technology.

“We need social scientists and ethicists on the design teams from the get-go,” Levi said. “That won’t resolve all the questions, but it would at least be a start to dealing with some of them.”

At Stanford, some of these collaborations are already taking place.

Jason Millar, an engineer and postdoctoral research fellow with the Center of Ethics in Society, is also working on the CARS ethical programming project. He is tackling how to translate knowledge developed in academic and philosophical circles into the daily design work of technology and artificial intelligence products.

“The idea is to address the concerns upfront, designing good technology that fits into people’s social worlds,” Millar said.

The Ethics of Self-driving Cars

Lesson Plan

Self-driving cars are already cruising the streets today. And while these cars will ultimately be safer and cleaner than their manual counterparts, they can’t completely avoid accidents altogether. How should the car be programmed if it encounters an unavoidable accident? Patrick Lin navigates the murky ethics of self-driving cars. Patrick Lin navigates the murky ethics of self-driving cars.

After watching the video on the ethical dilemma of self-driving cars , use the discussion questions to investigate the issues that are raised.

Discussion Questions

- In the situation described, would you prioritize your safety over everyone else’s by hitting the motorcycle?

- In the situation described, would you minimize danger to others by not swerving? if so, you would hit the large object and potentially die?

- In the situation described, would you take the middle ground by hitting the SUV since it’s less likely the driver will be injured? Compare this to hitting the motorcycle.

- What should a self-driving car do?

- What is the difference between a ”reaction” (human driver’s split second response) and a “deliberate decision” (driverless car’s calculated response)?

- Programing a car to react in a certain way in an emergency accident situation could be viewed as premeditated homicide. Do you think this is a valid argument? Why or why not?

If you would like to change or adapt any of PLATO's work for public use, please feel free to contact us for permission at [email protected] .

Related Tools

Connect With Us!

Stay Informed

PLATO is part of a global UNESCO network that encourages children to participate in philosophical inquiry. As a partner in the UNESCO Chair on the Practice of Philosophy with Children, based at the Université de Nantes in France, PLATO is connected to other educational leaders around the world.

About Stanford GSB

- The Leadership

- Dean’s Updates

- School News & History

- Commencement

- Business, Government & Society

- Centers & Institutes

- Center for Entrepreneurial Studies

- Center for Social Innovation

- Stanford Seed

About the Experience

- Learning at Stanford GSB

- Experiential Learning

- Guest Speakers

- Entrepreneurship

- Social Innovation

- Communication

- Life at Stanford GSB

- Collaborative Environment

- Activities & Organizations

- Student Services

- Housing Options

- International Students

Full-Time Degree Programs

- Why Stanford MBA

- Academic Experience

- Financial Aid

- Why Stanford MSx

- Research Fellows Program

- See All Programs

Non-Degree & Certificate Programs

- Executive Education

- Stanford Executive Program

- Programs for Organizations

- The Difference

- Online Programs

- Stanford LEAD

- Seed Transformation Program

- Aspire Program

- Seed Spark Program

- Faculty Profiles

- Academic Areas

- Awards & Honors

- Conferences

Faculty Research

- Publications

- Working Papers

- Case Studies

Research Hub

- Research Labs & Initiatives

- Business Library

- Data, Analytics & Research Computing

- Behavioral Lab

Research Labs

- Cities, Housing & Society Lab

- Golub Capital Social Impact Lab

Research Initiatives

- Corporate Governance Research Initiative

- Corporations and Society Initiative

- Policy and Innovation Initiative

- Rapid Decarbonization Initiative

- Stanford Latino Entrepreneurship Initiative

- Value Chain Innovation Initiative

- Venture Capital Initiative

- Career & Success

- Climate & Sustainability

- Corporate Governance

- Culture & Society

- Finance & Investing

- Government & Politics

- Leadership & Management

- Markets and Trade

- Operations & Logistics

- Opportunity & Access

- Technology & AI

- Opinion & Analysis

- Email Newsletter

Welcome, Alumni

- Communities

- Digital Communities & Tools

- Regional Chapters

- Women’s Programs

- Identity Chapters

- Find Your Reunion

- Career Resources

- Job Search Resources

- Career & Life Transitions

- Programs & Webinars

- Career Video Library

- Alumni Education

- Research Resources

- Volunteering

- Alumni News

- Class Notes

- Alumni Voices

- Contact Alumni Relations

- Upcoming Events

Admission Events & Information Sessions

- MBA Program

- MSx Program

- PhD Program

- Alumni Events

- All Other Events

Exploring the Ethics Behind Self-Driving Cars

How do you code ethics into autonomous automobiles? And who is responsible when things go awry?

August 13, 2015

Illustration by Abigail Goh

Imagine a runaway trolley barreling down on five people standing on the tracks up ahead. You can pull a lever to divert the trolley onto a different set of tracks where only one person is standing. Is the moral choice to do nothing and let the five people die? Or should you hit the switch and therefore actively participate in a different person’s death?

In the real world, the “trolley problem” first posed by philosopher Philippa Foot in 1967 is an abstraction most won’t ever have to actually face. And yet, as driverless cars roll into our lives, policymakers and auto manufacturers are edging into similar ethical dilemmas.

Quote One of the questions that comes up in class discussions is whether, as a driver, you should be able to program a degree of selfishness, making the car save the driver and passengers rather than people outside the car. Attribution Ken Shotts

For instance, how do you program a code of ethics into an automobile that performs split-second calculations that could harm one human over another? Who is legally responsible for the inevitable driverless-car accidents — car owners, carmakers, or programmers? Under what circumstances is a self-driving car allowed to break the law? What regulatory framework needs to be applied to what could be the first broad-scale social interaction between humans and intelligent machines?

Ken Shotts and Neil Malhotra , professors of political economy at Stanford GSB, along with Sheila Melvin , mull the philosophical and psychological issues at play in a new case study titled “ ‘The Nut Behind the Wheel’ to ‘Moral Machines’: A Brief History of Auto Safety .” Shotts discusses some of the issues here:

What are the ethical issues we need to be thinking about in light of driverless cars?

This is a great example of the “trolley problem.” You have a situation where the car might have to make a decision to sacrifice the driver to save some other people, or sacrifice one pedestrian to save some other pedestrians. And there are more subtle versions of it. Say there are two motorcyclists, one is wearing a helmet and the other isn’t. If I want to minimize deaths, I should hit the one wearing the helmet, but that just doesn’t feel right.

These are all hypothetical situations that you have to code into what the car is going to do. You have to cover all these situations, and so you are making the ethical choice up front.

It’s an interesting philosophical question to think about. It may turn out that we’ll be fairly consequentialist about these things. If we can save five lives by taking one, we generally think that’s something that should be done in the abstract. But it is something that is hard for automakers to talk about because they have to use very precise language for liability reasons when they talk about lives saved or deaths.

What are the implications of having to make those ethical choices in advance?

Right now, we make those instinctive decisions as humans based on our psychology. And we make those decisions erroneously some of the time. We make mistakes, we mishandle the wheel. But we make gut decisions that might be less selfish than what we would do if we were programming our own car. One of the questions that comes up in class discussions is whether, as a driver, you should be able to program a degree of selfishness, making the car save the driver and passengers rather than people outside the car. Frankly, my answer would be very different if I were programming it for driving alone versus having my 7-year-old daughter in the car. If I have her in the car, I would be very, very selfish in my programming.

Who needs to be taking the lead on parsing these ethical questions — policymakers, the automotive industry, philosophers?

The reality is that a lot of it will be what the industry chooses to do. But then policymakers are going to have to step in at some point. And at some point, there are going to be liability questions.

There are also questions about breaking the law. The folks at the Center for Automotive Research at Stanford have pointed out that there are times when normal drivers do all sorts of illegal things that make us safer. You’re merging onto the highway and you go the speed of traffic, which is faster than the speed limit. Someone goes into your lane and you briefly swerve into an oncoming lane. In an autonomous vehicle, is the “driver” legally culpable for those things? Is the automaker legally culpable for it? How do you handle all of that? That’s going to need to be worked out. And I don’t know how it is going to be worked out, frankly. Just that it needs to be.

Are there any lessons to be learned from the history of auto safety that could help guide us?

Sometimes eliminating people’s choices is beneficial. When seatbelts were not mandatory in cars, they were not supplied in cars, and when they were not mandatory to be used, they were not used. Looking at cost-benefit analysis, seatbelts are incredibly cost effective at saving lives, as is stability control. There are real benefits to having things like that mandated so that people don’t have the choice not to buy them.

The liability system can also induce companies to include automated safety features. But that actually raises an interesting issue, which is that in the liability system, sins of commission are punished more severely than sins of omission. If you put in airbags and the airbag hurts someone, that’s a huge liability issue. Failing to put in the airbag and someone dies? Not as big of an issue. Similarly, suppose that with a self-driving car, a company installs safety features that are automated. They save a lot of lives, but some of the time they result in some deaths. That safety feature is going to get hit in the liability system, I would think.

What sort of regulatory thickets are driverless cars headed into?

When people talk about self-driving cars, a lot of the attention falls on the Google car driving itself completely. But this really is just a progression of automation, bit by bit by bit. Stability control and anti-lock brakes are self-driving–type features, and we’re just getting more and more of them. Google gets a lot of attention in Silicon Valley, but the traditional automakers are putting this into practice.

So you could imagine different platforms and standards around all this. For example, should this be a series of incremental moves or should it be a big jump all the way to a Google-style self-driving car? Setting up different regulatory regimes would favor one of those approaches over the other. I’m not sure whether it’s the right policy, but incremental moves could be a good policy. But it also would be really good from the perspective of the auto manufacturers, and less good from the perspective of Google. And it could be potentially to a company’s advantage if they could try to influence the direction that the standards go in a way that favors their technology. This is something that companies moving into this area have to think about strategically, in addition to thinking about the ethical stuff.

What other big ethical questions do you see coming down the road?

At some point, do individuals get banned from having the right to drive? It sounds really far-fetched now. Being able to hit the road and drive freely is a very American thing to do. It feels weird to take away something that feels central to a lot of people’s identity.

But there are precedents for it. The one that Neil Malhotra, one of my coauthors on this case, pointed out is building houses. This used to be something we all did for ourselves with no government oversight 150 years ago. That’s a very immediate thing — it’s your dwelling, your castle. But if you try to build a house in most of the United States nowadays, there are all sorts of rules for how you have to do the wiring, how wide this has to be, how thick that has to be. Every little detail is very, very tightly regulated. Basically, you can’t do it yourself unless you follow all those rules. We’ve taken that out of individuals’ hands because we viewed there were beneficial consequences of taking it out of individuals’ hands. That may well happen for cars.

Graphics sources: newyorkologist.org; oldcarbrocheres.com; National Museum of American History; Academy of Achievement; iStock/hxdbzxy; Reuters/Stephen Lam.

For media inquiries, visit the Newsroom .

Explore More

Communicating the future: defining where we want ai to take us, navigating the ai revolution: practical insights for entrepreneurs, invisible matchmakers: how algorithms pair people with opportunities, editor’s picks.

‘The Nut Behind the Wheel’ to ‘Moral Machines:’ A Brief History of Auto Safety Neil Malhotra, Ken Shotts, Sheila Melvin

- See the Current DEI Report

- Supporting Data

- Research & Insights

- Share Your Thoughts

- Search Fund Primer

- Teaching & Curriculum

- Affiliated Faculty

- Faculty Advisors

- Louis W. Foster Resource Center

- Defining Social Innovation

- Impact Compass

- Global Health Innovation Insights

- Faculty Affiliates

- Student Awards & Certificates

- Changemakers

- Dean Jonathan Levin

- Dean Garth Saloner

- Dean Robert Joss

- Dean Michael Spence

- Dean Robert Jaedicke

- Dean Rene McPherson

- Dean Arjay Miller

- Dean Ernest Arbuckle

- Dean Jacob Hugh Jackson

- Dean Willard Hotchkiss

- Faculty in Memoriam

- Stanford GSB Firsts

- Annual Alumni Dinner

- Class of 2024 Candidates

- Certificate & Award Recipients

- Dean’s Remarks

- Keynote Address

- Teaching Approach

- Analysis and Measurement of Impact

- The Corporate Entrepreneur: Startup in a Grown-Up Enterprise

- Data-Driven Impact

- Designing Experiments for Impact

- Digital Marketing

- The Founder’s Right Hand

- Marketing for Measurable Change

- Product Management

- Public Policy Lab: Financial Challenges Facing US Cities

- Public Policy Lab: Homelessness in California

- Lab Features

- Curricular Integration

- View From The Top

- Formation of New Ventures

- Managing Growing Enterprises

- Startup Garage

- Explore Beyond the Classroom

- Stanford Venture Studio

- Summer Program

- Workshops & Events

- The Five Lenses of Entrepreneurship

- Leadership Labs

- Executive Challenge

- Arbuckle Leadership Fellows Program

- Selection Process

- Training Schedule

- Time Commitment

- Learning Expectations

- Post-Training Opportunities

- Who Should Apply

- Introductory T-Groups

- Leadership for Society Program

- Certificate

- 2024 Awardees

- 2023 Awardees

- 2022 Awardees

- 2021 Awardees

- 2020 Awardees

- 2019 Awardees

- 2018 Awardees

- Social Management Immersion Fund

- Stanford Impact Founder Fellowships

- Stanford Impact Leader Prizes

- Social Entrepreneurship

- Stanford GSB Impact Fund

- Economic Development

- Energy & Environment

- Stanford GSB Residences

- Environmental Leadership

- Stanford GSB Artwork

- A Closer Look

- California & the Bay Area

- Voices of Stanford GSB

- Business & Beneficial Technology

- Business & Sustainability

- Business & Free Markets

- Business, Government, and Society Forum

- Get Involved

- Second Year

- Global Experiences

- JD/MBA Joint Degree

- MA Education/MBA Joint Degree

- MD/MBA Dual Degree

- MPP/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Computer Science/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Electrical Engineering/MBA Joint Degree

- MS Environment and Resources (E-IPER)/MBA Joint Degree

- Academic Calendar

- Clubs & Activities

- LGBTQ+ Students

- Military Veterans

- Minorities & People of Color

- Partners & Families

- Students with Disabilities

- Student Support

- Residential Life

- Student Voices

- MBA Alumni Voices

- A Week in the Life

- Career Support

- Employment Outcomes

- Cost of Attendance

- Knight-Hennessy Scholars Program

- Yellow Ribbon Program

- BOLD Fellows Fund

- Application Process

- Loan Forgiveness

- Contact the Financial Aid Office

- Evaluation Criteria

- GMAT & GRE

- English Language Proficiency

- Personal Information, Activities & Awards

- Professional Experience

- Letters of Recommendation

- Optional Short Answer Questions

- Application Fee

- Reapplication

- Deferred Enrollment

- Joint & Dual Degrees

- Entering Class Profile

- Event Schedule

- Ambassadors

- New & Noteworthy

- Ask a Question

- See Why Stanford MSx

- Is MSx Right for You?

- MSx Stories

- Leadership Development

- How You Will Learn

- Admission Events

- Personal Information

- GMAT, GRE & EA

- English Proficiency Tests

- Career Change

- Career Advancement

- Career Support and Resources

- Daycare, Schools & Camps

- U.S. Citizens and Permanent Residents

- Requirements

- Requirements: Behavioral

- Requirements: Quantitative

- Requirements: Macro

- Requirements: Micro

- Annual Evaluations

- Field Examination

- Research Activities

- Research Papers

- Dissertation

- Oral Examination

- Current Students

- Education & CV

- International Applicants

- Statement of Purpose

- Reapplicants

- Application Fee Waiver

- Deadline & Decisions

- Job Market Candidates

- Academic Placements

- Stay in Touch

- Faculty Mentors

- Current Fellows

- Standard Track

- Fellowship & Benefits

- Group Enrollment

- Program Formats

- Developing a Program

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Strategic Transformation

- Program Experience

- Contact Client Services

- Campus Experience

- Live Online Experience

- Silicon Valley & Bay Area

- Digital Credentials

- Faculty Spotlights

- Participant Spotlights

- Eligibility

- International Participants

- Stanford Ignite

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Operations, Information & Technology

- Organizational Behavior

- Political Economy

- Classical Liberalism

- The Eddie Lunch

- Accounting Summer Camp

- California Econometrics Conference

- California Quantitative Marketing PhD Conference

- California School Conference

- China India Insights Conference

- Homo economicus, Evolving

- Political Economics (2023–24)

- Scaling Geologic Storage of CO2 (2023–24)

- A Resilient Pacific: Building Connections, Envisioning Solutions

- Adaptation and Innovation

- Changing Climate

- Civil Society

- Climate Impact Summit

- Climate Science

- Corporate Carbon Disclosures

- Earth’s Seafloor

- Environmental Justice

- Operations and Information Technology

- Organizations

- Sustainability Reporting and Control

- Taking the Pulse of the Planet

- Urban Infrastructure

- Watershed Restoration

- Junior Faculty Workshop on Financial Regulation and Banking

- Ken Singleton Celebration

- Marketing Camp

- Quantitative Marketing PhD Alumni Conference

- Presentations

- Theory and Inference in Accounting Research

- Stanford Closer Look Series

- Quick Guides

- Core Concepts

- Journal Articles

- Glossary of Terms

- Faculty & Staff

- Subscribe to Corporate Governance Emails

- Researchers & Students

- Research Approach

- Charitable Giving

- Financial Health

- Government Services

- Workers & Careers

- Short Course

- Adaptive & Iterative Experimentation

- Incentive Design

- Social Sciences & Behavioral Nudges

- Bandit Experiment Application

- Conferences & Events

- Reading Materials

- Energy Entrepreneurship

- Faculty & Affiliates

- SOLE Report

- Responsible Supply Chains

- Current Study Usage

- Pre-Registration Information

- Participate in a Study

- Founding Donors

- Program Contacts

- Location Information

- Participant Profile

- Network Membership

- Program Impact

- Collaborators

- Entrepreneur Profiles

- Company Spotlights

- Seed Transformation Network

- Responsibilities

- Current Coaches

- How to Apply

- Meet the Consultants

- Meet the Interns

- Intern Profiles

- Collaborate

- Research Library

- News & Insights

- Databases & Datasets

- Research Guides

- Consultations

- Research Workshops

- Career Research

- Research Data Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Research Guides

- Material Loan Periods

- Fines & Other Charges

- Document Delivery

- Interlibrary Loan

- Equipment Checkout

- Print & Scan

- MBA & MSx Students

- PhD Students

- Other Stanford Students

- Faculty Assistants

- Research Assistants

- Stanford GSB Alumni

- Telling Our Story

- Staff Directory

- Site Registration

- Alumni Directory

- Alumni Email

- Privacy Settings & My Profile

- Event Registration Help

- Success Stories

- The Story of Circles

- Support Women’s Circles

- Stanford Women on Boards Initiative

- Alumnae Spotlights

- Insights & Research

- Industry & Professional

- Entrepreneurial Commitment Group

- Recent Alumni

- Half-Century Club

- Fall Reunions

- Spring Reunions

- MBA 25th Reunion

- Half-Century Club Reunion

- Faculty Lectures

- Ernest C. Arbuckle Award

- Alison Elliott Exceptional Achievement Award

- ENCORE Award

- Excellence in Leadership Award

- John W. Gardner Volunteer Leadership Award

- Robert K. Jaedicke Faculty Award

- Jack McDonald Military Service Appreciation Award

- Jerry I. Porras Latino Leadership Award

- Tapestry Award

- Student & Alumni Events

- Executive Recruiters

- Interviewing

- Land the Perfect Job with LinkedIn

- Negotiating

- Elevator Pitch

- Email Best Practices

- Resumes & Cover Letters

- Self-Assessment

- Whitney Birdwell Ball

- Margaret Brooks

- Bryn Panee Burkhart

- Margaret Chan

- Ricki Frankel

- Peter Gandolfo

- Cindy W. Greig

- Natalie Guillen

- Carly Janson

- Sloan Klein

- Sherri Appel Lassila

- Stuart Meyer

- Tanisha Parrish

- Virginia Roberson

- Philippe Taieb

- Michael Takagawa

- Terra Winston

- Johanna Wise

- Debbie Wolter

- Rebecca Zucker

- Complimentary Coaching

- Changing Careers

- Work-Life Integration

- Career Breaks

- Flexible Work

- Encore Careers

- Join a Board

- D&B Hoovers

- Data Axle (ReferenceUSA)

- EBSCO Business Source

- Global Newsstream

- Market Share Reporter

- ProQuest One Business

- RKMA Market Research Handbook Series

- Student Clubs

- Entrepreneurial Students

- Stanford GSB Trust

- Alumni Community

- How to Volunteer

- Springboard Sessions

- Consulting Projects

- 2020 – 2029

- 2010 – 2019

- 2000 – 2009

- 1990 – 1999

- 1980 – 1989

- 1970 – 1979

- 1960 – 1969

- 1950 – 1959

- 1940 – 1949

- Service Areas

- ACT History

- ACT Awards Celebration

- ACT Governance Structure

- Building Leadership for ACT

- Individual Leadership Positions

- Leadership Role Overview

- Purpose of the ACT Management Board

- Contact ACT

- Business & Nonprofit Communities

- Reunion Volunteers

- Ways to Give

- Fiscal Year Report

- Business School Fund Leadership Council

- Planned Giving Options

- Planned Giving Benefits

- Planned Gifts and Reunions

- Legacy Partners

- Giving News & Stories

- Giving Deadlines

- Development Staff

- Submit Class Notes

- Class Secretaries

- Board of Directors

- Health Care

- Sustainability

- Class Takeaways

- All Else Equal: Making Better Decisions

- If/Then: Business, Leadership, Society

- Grit & Growth

- Think Fast, Talk Smart

- Spring 2022

- Spring 2021

- Autumn 2020

- Summer 2020

- Winter 2020

- In the Media

- For Journalists

- DCI Fellows

- Other Auditors

- Academic Calendar & Deadlines

- Course Materials

- Entrepreneurial Resources

- Campus Drive Grove

- Campus Drive Lawn

- CEMEX Auditorium

- King Community Court

- Seawell Family Boardroom

- Stanford GSB Bowl

- Stanford Investors Common

- Town Square

- Vidalakis Courtyard

- Vidalakis Dining Hall

- Catering Services

- Policies & Guidelines

- Reservations

- Contact Faculty Recruiting

- Lecturer Positions

- Postdoctoral Positions

- Accommodations

- CMC-Managed Interviews

- Recruiter-Managed Interviews

- Virtual Interviews

- Campus & Virtual

- Search for Candidates

- Think Globally

- Recruiting Calendar

- Recruiting Policies

- Full-Time Employment

- Summer Employment

- Entrepreneurial Summer Program

- Global Management Immersion Experience

- Social-Purpose Summer Internships

- Process Overview