Introduction to Money and Banking

Chapter objectives.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- Defining Money by Its Functions

- Measuring Money: Currency, M1, and M2

- The Role of Banks

- How Banks Create Money

Bring It Home

The many disguises of money: from cowries to crypto.

Here is a trivia question: In the history of the world, what item did people use for money over the broadest geographic area and for the longest period of time? The answer is not gold, silver, or any precious metal. It is the cowrie, a mollusk shell found mainly off the Maldives Islands in the Indian Ocean. Cowries served as money as early as 700 B.C. in China. By the 1500s, they were in widespread use across India and Africa. For several centuries after that, cowries were the means for exchange in markets including southern Europe, western Africa, India, and China: everything from buying lunch or a ferry ride to paying for a shipload of silk or rice. Cowries were still acceptable as a way of paying taxes in certain African nations in the early twentieth century.

What made cowries work so well as money? First, they are extremely durable—lasting a century or more. As the late economic historian Karl Polyani put it, they can be “poured, sacked, shoveled, hoarded in heaps” while remaining “clean, dainty, stainless, polished, and milk-white.” Second, parties could use cowries either by counting shells of a certain size, or—for large purchases—by measuring the weight or volume of the total shells they would exchange. Third, it was impossible to counterfeit a cowrie shell, but dishonest people could counterfeit gold or silver coins by making copies with cheaper metals. Finally, in the heyday of cowrie money, from the 1500s into the 1800s, governments, first the Portuguese, then the Dutch and English, tightly controlled collecting cowries. As a result, the supply of cowries grew quickly enough to serve the needs of commerce, but not so quickly that they were no longer scarce. Money throughout the ages has taken many different forms and continues to evolve even today with the advent of cryptocurrency. What do you think money is?

The discussion of money and banking is a central component in studying macroeconomics. At this point, you should have firmly in mind the main goals of macroeconomics from Welcome to Economics! : economic growth , low unemployment , and low inflation . We have yet to discuss money and its role in helping to achieve our macroeconomic goals.

You should also understand Keynesian and neoclassical frameworks for macroeconomic analysis and how we can embody these frameworks in the aggregate demand/aggregate supply (AD/AS) model. With the goals and frameworks for macroeconomic analysis in mind, the final step is to discuss the two main categories of macroeconomic policy: monetary policy, which focuses on money, banking and interest rates; and fiscal policy, which focuses on government spending, taxes, and borrowing. This chapter discusses what economists mean by money, and how money is closely interrelated with the banking system. Monetary Policy and Bank Regulation furthers this discussion.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Steven A. Greenlaw, David Shapiro, Daniel MacDonald

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Principles of Economics 3e

- Publication date: Dec 14, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/principles-economics-3e/pages/27-introduction-to-money-and-banking

© Jan 23, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

24.2 The Banking System and Money Creation

Learning objectives.

- Explain what banks are, what their balance sheets look like, and what is meant by a fractional reserve banking system.

- Describe the process of money creation (destruction), using the concept of the deposit multiplier.

- Describe how and why banks are regulated and insured.

Where does money come from? How is its quantity increased or decreased? The answer to these questions suggests that money has an almost magical quality: money is created by banks when they issue loans . In effect, money is created by the stroke of a pen or the click of a computer key.

We will begin by examining the operation of banks and the banking system. We will find that, like money itself, the nature of banking is experiencing rapid change.

Banks and Other Financial Intermediaries

An institution that amasses funds from one group and makes them available to another is called a financial intermediary . A pension fund is an example of a financial intermediary. Workers and firms place earnings in the fund for their retirement; the fund earns income by lending money to firms or by purchasing their stock. The fund thus makes retirement saving available for other spending. Insurance companies are also financial intermediaries, because they lend some of the premiums paid by their customers to firms for investment. Mutual funds make money available to firms and other institutions by purchasing their initial offerings of stocks or bonds.

Banks play a particularly important role as financial intermediaries. Banks accept depositors’ money and lend it to borrowers. With the interest they earn on their loans, banks are able to pay interest to their depositors, cover their own operating costs, and earn a profit, all the while maintaining the ability of the original depositors to spend the funds when they desire to do so. One key characteristic of banks is that they offer their customers the opportunity to open checking accounts, thus creating checkable deposits. These functions define a bank , which is a financial intermediary that accepts deposits, makes loans, and offers checking accounts.

Over time, some nonbank financial intermediaries have become more and more like banks. For example, some brokerage firms offer customers interest-earning accounts and make loans. They now allow their customers to write checks on their accounts.

As nonbank financial intermediaries have grown, banks’ share of the nation’s credit market financial assets has diminished. In 1972, banks accounted for nearly 30% of U.S. credit market financial assets. In 2007, that share had dropped to about 15%.

The fact that banks account for a declining share of U.S. financial assets alarms some observers. We will see that banks are more tightly regulated than are other financial institutions; one reason for that regulation is to maintain control over the money supply. Other financial intermediaries do not face the same regulatory restrictions as banks. Indeed, their freedom from regulation is one reason they have grown so rapidly. As other financial intermediaries become more important, central authorities begin to lose control over the money supply.

The declining share of financial assets controlled by “banks” began to change in 2008. Many of the nation’s largest investment banks—financial institutions that provided services to firms but were not regulated as commercial banks—began having serious financial difficulties as a result of their investments tied to home mortgage loans. As home prices in the United States began falling, many of those mortgage loans went into default. Investment banks that had made substantial purchases of securities whose value was ultimately based on those mortgage loans themselves began failing. Bear Stearns, one of the largest investment banks in the United States, required federal funds to remain solvent. Another large investment bank, Lehman Brothers, failed. In an effort to avoid a similar fate, several other investment banks applied for status as ordinary commercial banks subject to the stringent regulation those institutions face. One result of the terrible financial crisis that crippled the U.S. and other economies in 2008 may be greater control of the money supply by the Fed.

Bank Finance and a Fractional Reserve System

Bank finance lies at the heart of the process through which money is created. To understand money creation, we need to understand some of the basics of bank finance.

Banks accept deposits and issue checks to the owners of those deposits. Banks use the money collected from depositors to make loans. The bank’s financial picture at a given time can be depicted using a simplified balance sheet , which is a financial statement showing assets, liabilities, and net worth. Assets are anything of value. Liabilities are obligations to other parties. Net worth equals assets less liabilities. All these are given dollar values in a firm’s balance sheet. The sum of liabilities plus net worth therefore must equal the sum of all assets. On a balance sheet, assets are listed on the left, liabilities and net worth on the right.

The main way that banks earn profits is through issuing loans. Because their depositors do not typically all ask for the entire amount of their deposits back at the same time, banks lend out most of the deposits they have collected—to companies seeking to expand their operations, to people buying cars or homes, and so on. Banks keep only a fraction of their deposits as cash in their vaults and in deposits with the Fed. These assets are called reserves . Banks lend out the rest of their deposits. A system in which banks hold reserves whose value is less than the sum of claims outstanding on those reserves is called a fractional reserve banking system .

Table 24.1 “The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, October 2010” shows a consolidated balance sheet for commercial banks in the United States for October 2010. Banks hold reserves against the liabilities represented by their checkable deposits. Notice that these reserves were a small fraction of total deposit liabilities of that month. Most bank assets are in the form of loans.

Table 24.1 The Consolidated Balance Sheet for U.S. Commercial Banks, October 2010

This balance sheet for all commercial banks in the United States shows their financial situation in billions of dollars, seasonally adjusted, on October 2010.

Source : Federal Reserve Statistical Release H.8, December 3, 2010.

In the next section, we will learn that money is created when banks issue loans.

Money Creation

To understand the process of money creation today, let us create a hypothetical system of banks. We will focus on three banks in this system: Acme Bank, Bellville Bank, and Clarkston Bank. Assume that all banks are required to hold reserves equal to 10% of their checkable deposits. The quantity of reserves banks are required to hold is called required reserves . The reserve requirement is expressed as a required reserve ratio ; it specifies the ratio of reserves to checkable deposits a bank must maintain. Banks may hold reserves in excess of the required level; such reserves are called excess reserves . Excess reserves plus required reserves equal total reserves.

Because banks earn relatively little interest on their reserves held on deposit with the Federal Reserve, we shall assume that they seek to hold no excess reserves. When a bank’s excess reserves equal zero, it is loaned up . Finally, we shall ignore assets other than reserves and loans and deposits other than checkable deposits. To simplify the analysis further, we shall suppose that banks have no net worth; their assets are equal to their liabilities.

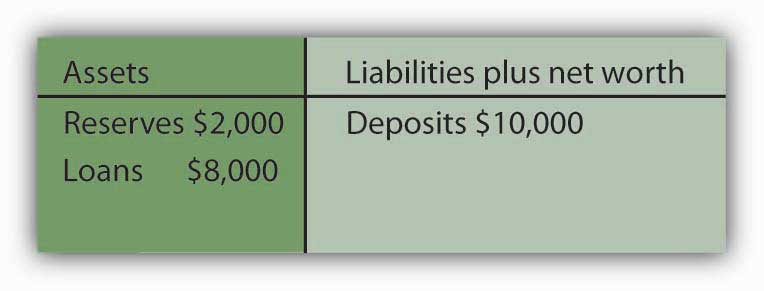

Let us suppose that every bank in our imaginary system begins with $1,000 in reserves, $9,000 in loans outstanding, and $10,000 in checkable deposit balances held by customers. The balance sheet for one of these banks, Acme Bank, is shown in Table 24.2 “A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank” . The required reserve ratio is 0.1: Each bank must have reserves equal to 10% of its checkable deposits. Because reserves equal required reserves, excess reserves equal zero. Each bank is loaned up.

Table 24.2 A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank

We assume that all banks in a hypothetical system of banks have $1,000 in reserves, $10,000 in checkable deposits, and $9,000 in loans. With a 10% reserve requirement, each bank is loaned up; it has zero excess reserves.

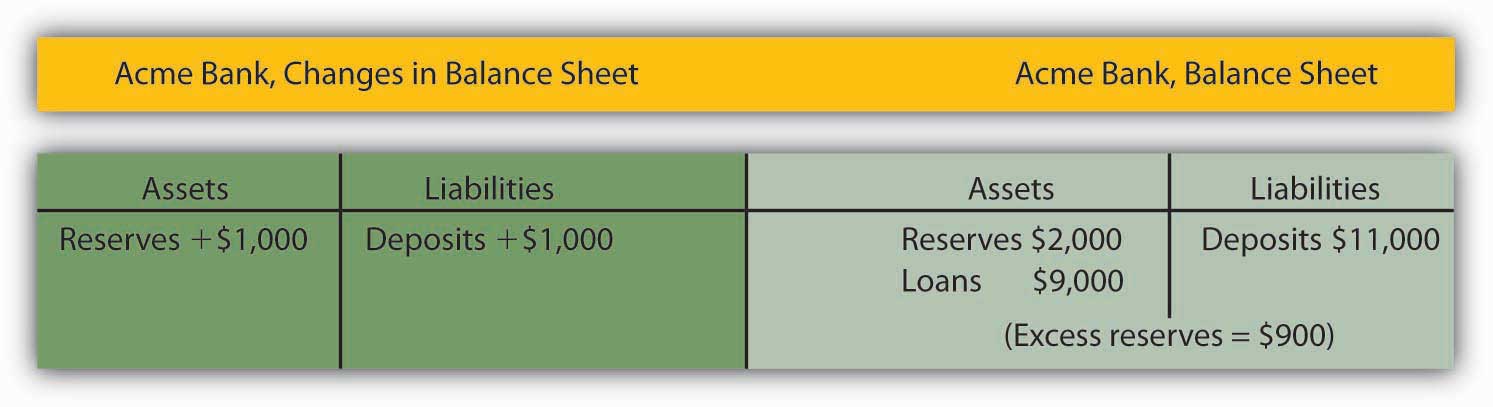

Acme Bank, like every other bank in our hypothetical system, initially holds reserves equal to the level of required reserves. Now suppose one of Acme Bank’s customers deposits $1,000 in cash in a checking account. The money goes into the bank’s vault and thus adds to reserves. The customer now has an additional $1,000 in his or her account. Two versions of Acme’s balance sheet are given here. The first shows the changes brought by the customer’s deposit: reserves and checkable deposits rise by $1,000. The second shows how these changes affect Acme’s balances. Reserves now equal $2,000 and checkable deposits equal $11,000. With checkable deposits of $11,000 and a 10% reserve requirement, Acme is required to hold reserves of $1,100. With reserves equaling $2,000, Acme has $900 in excess reserves.

At this stage, there has been no change in the money supply. When the customer brought in the $1,000 and Acme put the money in the vault, currency in circulation fell by $1,000. At the same time, the $1,000 was added to the customer’s checking account balance, so the money supply did not change.

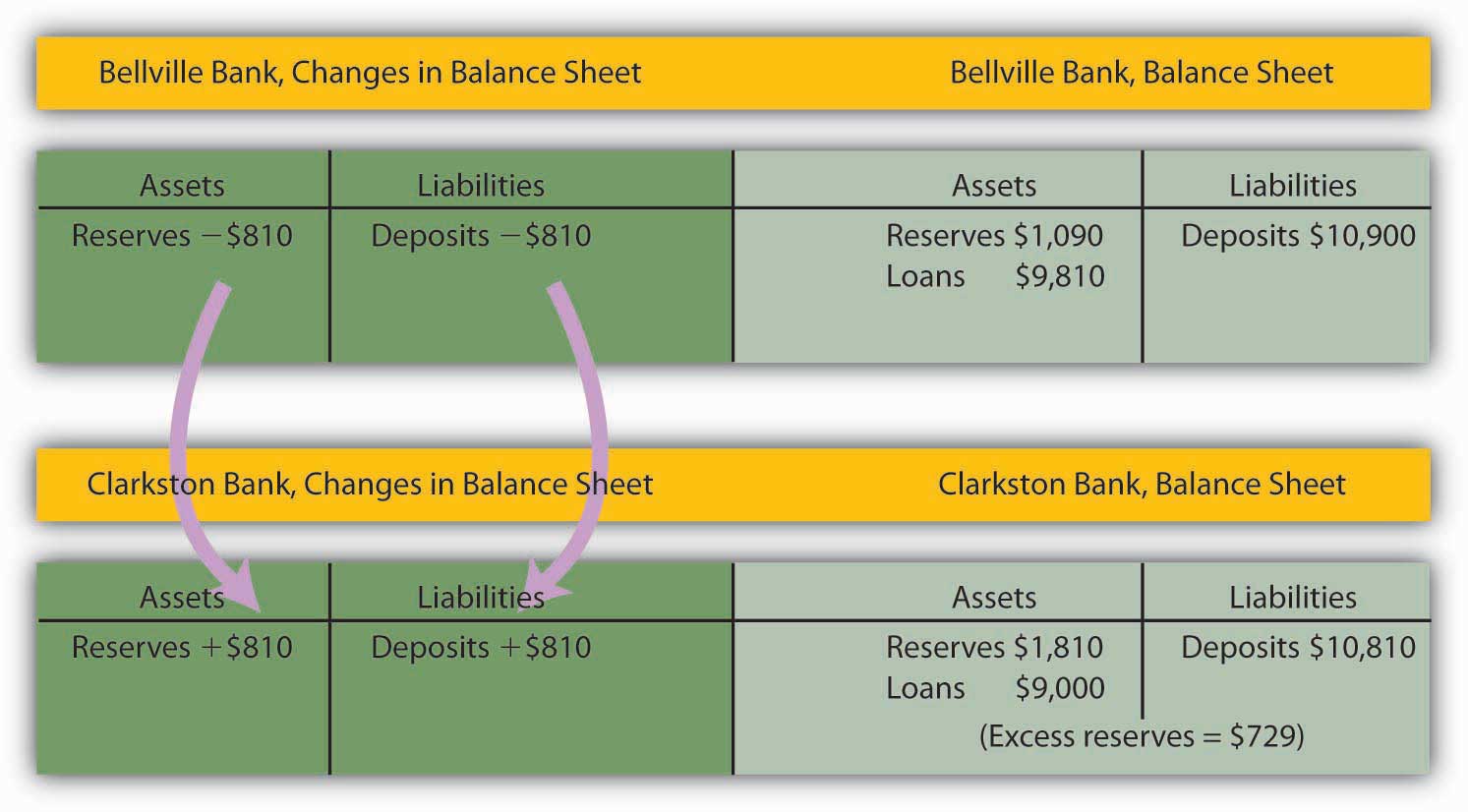

Figure 24.3

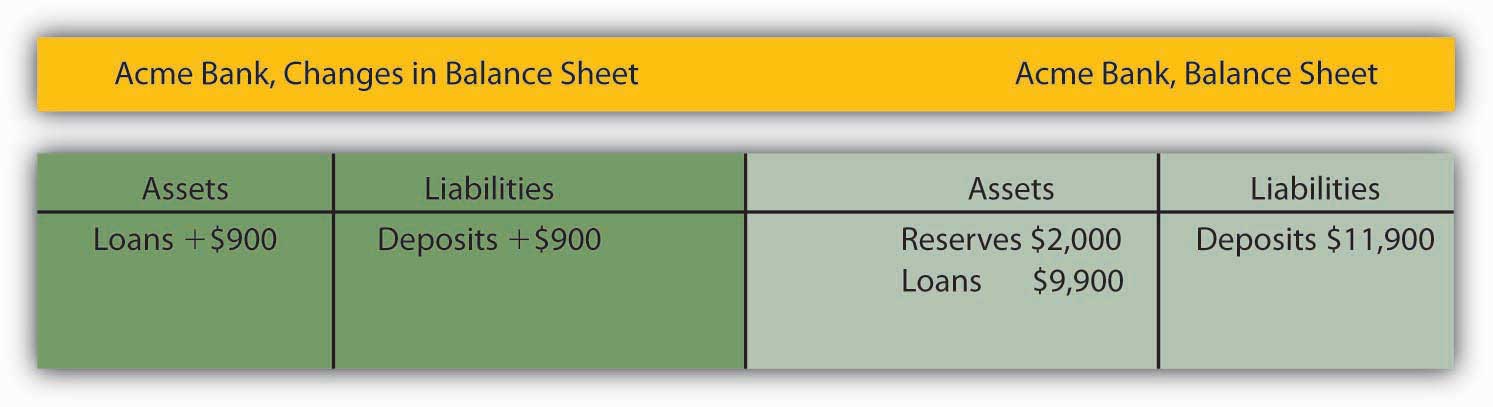

Because Acme earns only a low interest rate on its excess reserves, we assume it will try to loan them out. Suppose Acme lends the $900 to one of its customers. It will make the loan by crediting the customer’s checking account with $900. Acme’s outstanding loans and checkable deposits rise by $900. The $900 in checkable deposits is new money; Acme created it when it issued the $900 loan. Now you know where money comes from—it is created when a bank issues a loan.

Figure 24.4

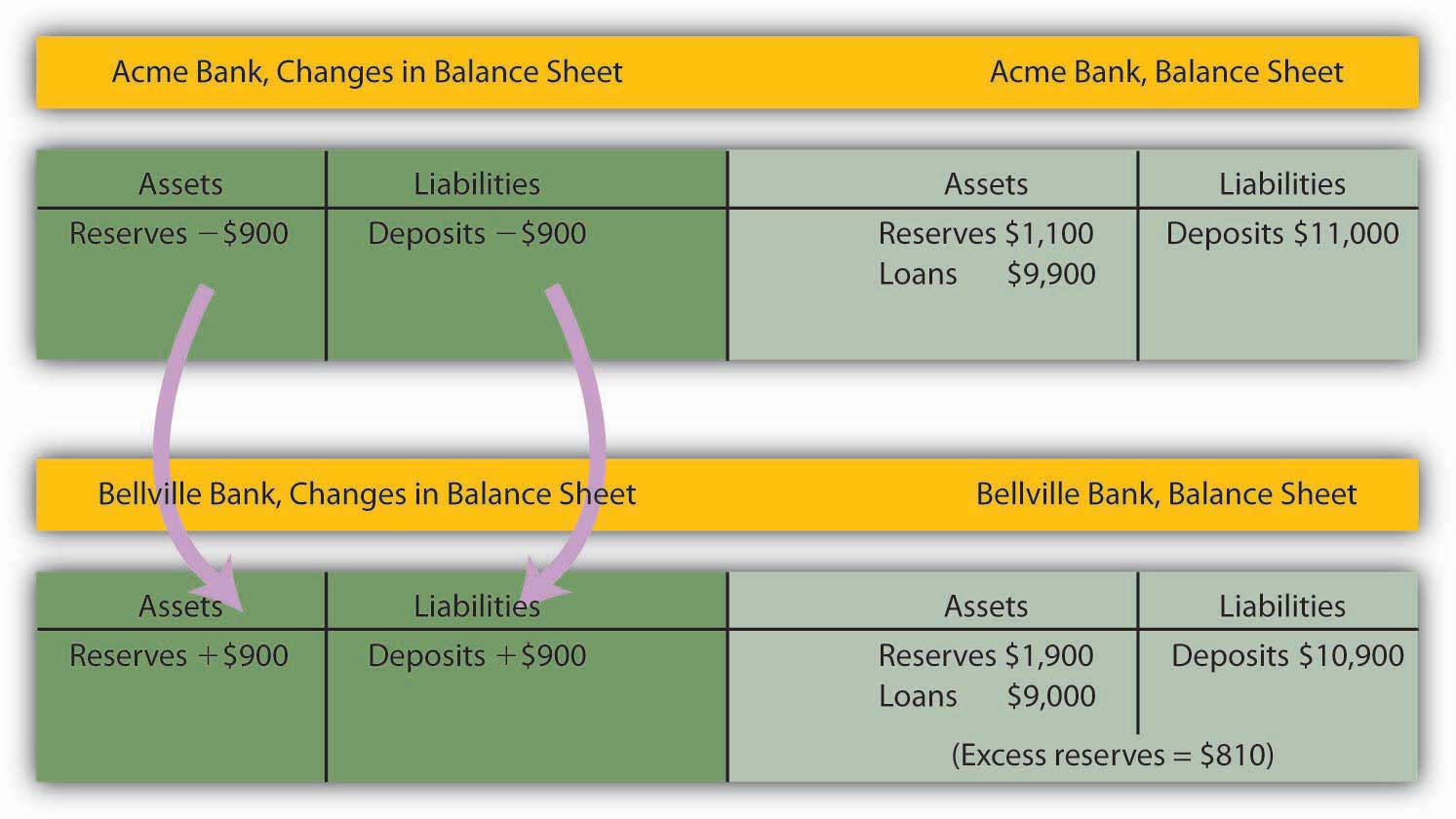

Presumably, the customer who borrowed the $900 did so in order to spend it. That customer will write a check to someone else, who is likely to bank at some other bank. Suppose that Acme’s borrower writes a check to a firm with an account at Bellville Bank. In this set of transactions, Acme’s checkable deposits fall by $900. The firm that receives the check deposits it in its account at Bellville Bank, increasing that bank’s checkable deposits by $900. Bellville Bank now has a check written on an Acme account. Bellville will submit the check to the Fed, which will reduce Acme’s deposits with the Fed—its reserves—by $900 and increase Bellville’s reserves by $900.

Figure 24.5

Notice that Acme Bank emerges from this round of transactions with $11,000 in checkable deposits and $1,100 in reserves. It has eliminated its excess reserves by issuing the loan for $900; Acme is now loaned up. Notice also that from Acme’s point of view, it has not created any money! It merely took in a $1,000 deposit and emerged from the process with $1,000 in additional checkable deposits.

The $900 in new money Acme created when it issued a loan has not vanished—it is now in an account in Bellville Bank. Like the magician who shows the audience that the hat from which the rabbit appeared was empty, Acme can report that it has not created any money. There is a wonderful irony in the magic of money creation: banks create money when they issue loans, but no one bank ever seems to keep the money it creates. That is because money is created within the banking system, not by a single bank.

The process of money creation will not end there. Let us go back to Bellville Bank. Its deposits and reserves rose by $900 when the Acme check was deposited in a Bellville account. The $900 deposit required an increase in required reserves of $90. Because Bellville’s reserves rose by $900, it now has $810 in excess reserves. Just as Acme lent the amount of its excess reserves, we can expect Bellville to lend this $810. The next set of balance sheets shows this transaction. Bellville’s loans and checkable deposits rise by $810.

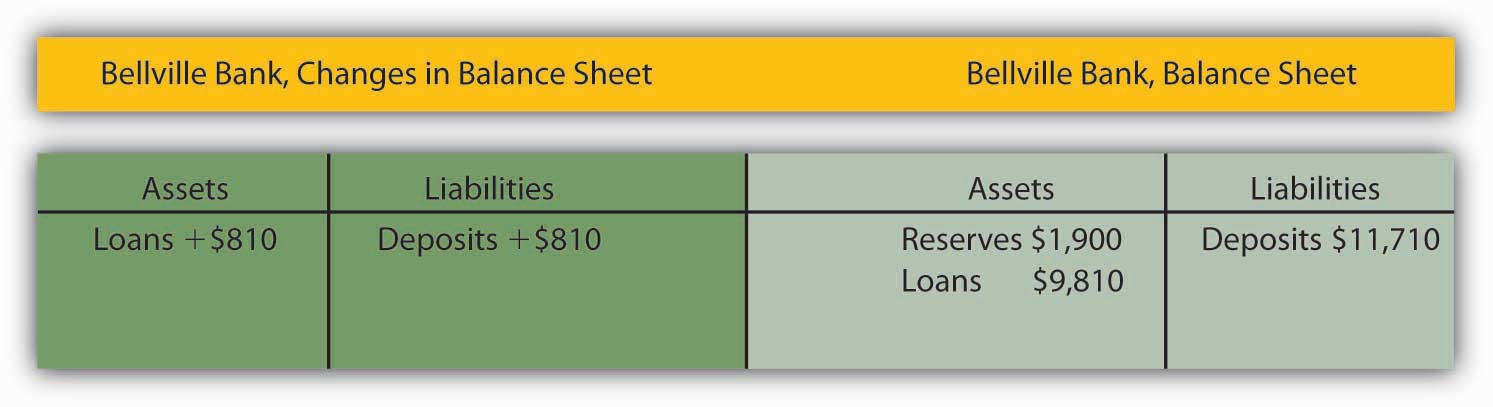

Figure 24.6

The $810 that Bellville lent will be spent. Let us suppose it ends up with a customer who banks at Clarkston Bank. Bellville’s checkable deposits fall by $810; Clarkston’s rise by the same amount. Clarkston submits the check to the Fed, which transfers the money from Bellville’s reserve account to Clarkston’s. Notice that Clarkston’s deposits rise by $810; Clarkston must increase its reserves by $81. But its reserves have risen by $810, so it has excess reserves of $729.

Figure 24.7

Notice that Bellville is now loaned up. And notice that it can report that it has not created any money either! It took in a $900 deposit, and its checkable deposits have risen by that same $900. The $810 it created when it issued a loan is now at Clarkston Bank.

The process will not end there. Clarkston will lend the $729 it now has in excess reserves, and the money that has been created will end up at some other bank, which will then have excess reserves—and create still more money. And that process will just keep going as long as there are excess reserves to pass through the banking system in the form of loans. How much will ultimately be created by the system as a whole? With a 10% reserve requirement, each dollar in reserves backs up $10 in checkable deposits. The $1,000 in cash that Acme’s customer brought in adds $1,000 in reserves to the banking system. It can therefore back up an additional $10,000! In just the three banks we have shown, checkable deposits have risen by $2,710 ($1,000 at Acme, $900 at Bellville, and $810 at Clarkston). Additional banks in the system will continue to create money, up to a maximum of $7,290 among them. Subtracting the original $1,000 that had been a part of currency in circulation, we see that the money supply could rise by as much as $9,000.

Notice that when the banks received new deposits, they could make new loans only up to the amount of their excess reserves, not up to the amount of their deposits and total reserve increases. For example, with the new deposit of $1,000, Acme Bank was able to make additional loans of $900. If instead it made new loans equal to its increase in total reserves, then after the customers who received new loans wrote checks to others, its reserves would be less than the required amount. In the case of Acme, had it lent out an additional $1,000, after checks were written against the new loans, it would have been left with only $1,000 in reserves against $11,000 in deposits, for a reserve ratio of only 0.09, which is less than the required reserve ratio of 0.1 in the example.

The Deposit Multiplier

We can relate the potential increase in the money supply to the change in reserves that created it using the deposit multiplier ( m d ), which equals the ratio of the maximum possible change in checkable deposits (∆ D ) to the change in reserves (∆ R ). In our example, the deposit multiplier was 10:

Equation 24.1

[latex]m_d = \frac{ \Delta D}{ \Delta R} = \frac{ \$ 10,000}{ \$ 1,000} = 10[/latex]

To see how the deposit multiplier m d is related to the required reserve ratio, we use the fact that if banks in the economy are loaned up, then reserves, R , equal the required reserve ratio ( rrr ) times checkable deposits, D :

Equation 24.2

[latex]R = rrrD[/latex]

A change in reserves produces a change in loans and a change in checkable deposits. Once banks are fully loaned up, the change in reserves, ∆ R , will equal the required reserve ratio times the change in deposits, ∆ D :

Equation 24.3

[latex]\Delta R = rrr \Delta D[/latex]

Solving for ∆ D , we have

Equation 24.4

[latex]\frac{1}{rrr} \Delta R = \Delta D[/latex]

Dividing both sides by ∆ R , we see that the deposit multiplier, m d , is 1/ rrr :

Equation 24.5

[latex]\frac{1}{rrr} = \frac{ \Delta D}{ \Delta R} = m_d[/latex]

The deposit multiplier is thus given by the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio . With a required reserve ratio of 0.1, the deposit multiplier is 10. A required reserve ratio of 0.2 would produce a deposit multiplier of 5. The higher the required reserve ratio, the lower the deposit multiplier.

Actual increases in checkable deposits will not be nearly as great as suggested by the deposit multiplier. That is because the artificial conditions of our example are not met in the real world. Some banks hold excess reserves, customers withdraw cash, and some loan proceeds are not spent. Each of these factors reduces the degree to which checkable deposits are affected by an increase in reserves. The basic mechanism, however, is the one described in our example, and it remains the case that checkable deposits increase by a multiple of an increase in reserves.

The entire process of money creation can work in reverse. When you withdraw cash from your bank, you reduce the bank’s reserves. Just as a deposit at Acme Bank increases the money supply by a multiple of the original deposit, your withdrawal reduces the money supply by a multiple of the amount you withdraw. And just as money is created when banks issue loans, it is destroyed as the loans are repaid. A loan payment reduces checkable deposits; it thus reduces the money supply.

Suppose, for example, that the Acme Bank customer who borrowed the $900 makes a $100 payment on the loan. Only part of the payment will reduce the loan balance; part will be interest. Suppose $30 of the payment is for interest, while the remaining $70 reduces the loan balance. The effect of the payment on Acme’s balance sheet is shown below. Checkable deposits fall by $100, loans fall by $70, and net worth rises by the amount of the interest payment, $30.

Similar to the process of money creation, the money reduction process decreases checkable deposits by, at most, the amount of the reduction in deposits times the deposit multiplier.

Figure 24.8

The Regulation of Banks

Banks are among the most heavily regulated of financial institutions. They are regulated in part to protect individual depositors against corrupt business practices. Banks are also susceptible to crises of confidence. Because their reserves equal only a fraction of their deposit liabilities, an effort by customers to get all their cash out of a bank could force it to fail. A few poorly managed banks could create such a crisis, leading people to try to withdraw their funds from well-managed banks. Another reason for the high degree of regulation is that variations in the quantity of money have important effects on the economy as a whole, and banks are the institutions through which money is created.

Deposit Insurance

From a customer’s point of view, the most important form of regulation comes in the form of deposit insurance. For commercial banks, this insurance is provided by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Insurance funds are maintained through a premium assessed on banks for every $100 of bank deposits.

If a commercial bank fails, the FDIC guarantees to reimburse depositors up to $250,000 (raised from $100,000 during the financial crisis of 2008) per insured bank, for each account ownership category. From a depositor’s point of view, therefore, it is not necessary to worry about a bank’s safety.

One difficulty this insurance creates, however, is that it may induce the officers of a bank to take more risks. With a federal agency on hand to bail them out if they fail, the costs of failure are reduced. Bank officers can thus be expected to take more risks than they would otherwise, which, in turn, makes failure more likely. In addition, depositors, knowing that their deposits are insured, may not scrutinize the banks’ lending activities as carefully as they would if they felt that unwise loans could result in the loss of their deposits.

Thus, banks present us with a fundamental dilemma. A fractional reserve system means that banks can operate only if their customers maintain their confidence in them. If bank customers lose confidence, they are likely to try to withdraw their funds. But with a fractional reserve system, a bank actually holds funds in reserve equal to only a small fraction of its deposit liabilities. If its customers think a bank will fail and try to withdraw their cash, the bank is likely to fail. Bank panics, in which frightened customers rush to withdraw their deposits, contributed to the failure of one-third of the nation’s banks between 1929 and 1933. Deposit insurance was introduced in large part to give people confidence in their banks and to prevent failure. But the deposit insurance that seeks to prevent bank failures may lead to less careful management—and thus encourage bank failure.

Regulation to Prevent Bank Failure

To reduce the number of bank failures, banks are severely limited in what they can do. They are barred from certain types of financial investments and from activities viewed as too risky. Banks are required to maintain a minimum level of net worth as a fraction of total assets. Regulators from the FDIC regularly perform audits and other checks of individual banks to ensure they are operating safely.

The FDIC has the power to close a bank whose net worth has fallen below the required level. In practice, it typically acts to close a bank when it becomes insolvent, that is, when its net worth becomes negative. Negative net worth implies that the bank’s liabilities exceed its assets.

When the FDIC closes a bank, it arranges for depositors to receive their funds. When the bank’s funds are insufficient to return customers’ deposits, the FDIC uses money from the insurance fund for this purpose. Alternatively, the FDIC may arrange for another bank to purchase the failed bank. The FDIC, however, continues to guarantee that depositors will not lose any money.

Key Takeaways

- Banks are financial intermediaries that accept deposits, make loans, and provide checking accounts for their customers.

- Money is created within the banking system when banks issue loans; it is destroyed when the loans are repaid.

- An increase (decrease) in reserves in the banking system can increase (decrease) the money supply. The maximum amount of the increase (decrease) is equal to the deposit multiplier times the change in reserves; the deposit multiplier equals the reciprocal of the required reserve ratio.

- Bank deposits are insured and banks are heavily regulated.

- Suppose Acme Bank initially has $10,000 in deposits, reserves of $2,000, and loans of $8,000. At a required reserve ratio of 0.2, is Acme loaned up? Show the balance sheet of Acme Bank at present.

- Now suppose that an Acme Bank customer, planning to take cash on an extended college graduation trip to India, withdraws $1,000 from her account. Show the changes to Acme Bank’s balance sheet and Acme’s balance sheet after the withdrawal. By how much are its reserves now deficient?

- Acme would probably replenish its reserves by reducing loans. This action would cause a multiplied contraction of checkable deposits as other banks lose deposits because their customers would be paying off loans to Acme. How large would the contraction be?

Case in Point: A Big Bank Goes Under

Figure 24.9

Wikimedia Commons – CC BY-SA 3.0.

It was the darling of Wall Street—it showed rapid growth and made big profits. Washington Mutual, a savings and loan based in the state of Washington, was a relatively small institution whose CEO, Kerry K. Killinger, had big plans. He wanted to transform his little Seattle S&L into the Wal-Mart of banks.

Mr. Killinger began pursuing a relatively straightforward strategy. He acquired banks in large cities such as Chicago and Los Angeles. He acquired banks up and down the east and west coasts. He aggressively extended credit to low-income individuals and families—credit cards, car loans, and mortgages. In making mortgage loans to low-income families, WaMu, as the bank was known, quickly became very profitable. But it was exposing itself to greater and greater risk, according to the New York Times .

Housing prices in the United States more than doubled between 1997 and 2007. During that time, loans to even low-income households were profitable. But, as housing prices began falling in 2007, banks such as WaMu began to experience losses as homeowners began to walk away from houses whose values suddenly fell below their outstanding mortgages. WaMu began losing money in 2007 as housing prices began falling. The company had earned $3.6 billion in 2006, and swung to a loss of $67 million in 2007, according to the Puget Sound Business Journal . Mr. Killinger was ousted by the board early in September of 2008. The bank failed later that month. It was the biggest bank failure in the history of the United States.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) had just rescued another bank, IndyMac, which was only a tenth the size of WaMu, and would have done the same for WaMu if it had not been able to find a company to purchase it. But in this case, JPMorgan Chase agreed to take it over—its deposits, bank branches, and its troubled asset portfolio. The government and the Fed even negotiated the deal behind WaMu’s back! The then chief executive officer of the company, Alan H. Fishman, was reportedly flying from New York to Seattle when the deal was finalized.

The government was anxious to broker a deal that did not require use of the FDIC’s depleted funds following IndyMac’s collapse. But it would have done so if a buyer had not been found. As the FDIC reports on its Web site: “Since the FDIC’s creation in 1933, no depositor has ever lost even one penny of FDIC-insured funds.”

Sources : Eric Dash and Andrew Ross Sorkin, “Government Seizes WaMu and Sells Some Assets,” The New York Times , September 25, 2008, p. A1; Kirsten Grind, “Insiders Detail Reasons for WaMu’s Failure,” Puget Sound Business Journal , January 23, 2009; and FDIC Web site at https://www.fdic.gov/edie/fdic_info.html .

Answer to Try It! Problem

Acme Bank is loaned up, since $2,000/$10,000 = 0.2, which is the required reserve ratio. Acme’s balance sheet is:

Figure 24.10

Acme Bank’s balance sheet after losing $1,000 in deposits:

Figure 24.11

Required reserves are deficient by $800. Acme must hold 20% of its deposits, in this case $1,800 (0.2 × $9,000=$1,800), as reserves, but it has only $1,000 in reserves at the moment.

The contraction in checkable deposits would be

∆D = (1/0.2) × (−$1,000) = −$5,000

Principles of Economics Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Get started with computers

- Learn Microsoft Office

- Apply for a job

- Improve my work skills

- Design nice-looking docs

- Getting Started

- Smartphones & Tablets

- Typing Tutorial

- Online Learning

- Basic Internet Skills

- Online Safety

- Social Media

- Zoom Basics

- Google Docs

- Google Sheets

- Career Planning

- Resume Writing

- Cover Letters

- Job Search and Networking

- Business Communication

- Entrepreneurship 101

- Careers without College

- Job Hunt for Today

- 3D Printing

- Freelancing 101

- Personal Finance

- Sharing Economy

- Decision-Making

- Graphic Design

- Photography

- Image Editing

- Learning WordPress

- Language Learning

- Critical Thinking

- For Educators

- Translations

- Staff Picks

- English expand_more expand_less

Money Basics - Assessing How You Manage Money

Money basics -, assessing how you manage money, money basics assessing how you manage money.

Money Basics: Assessing How You Manage Money

Lesson 3: assessing how you manage money.

/en/moneybasics/financial-problem-solving-strategies/content/

Assessing how you manage money

By the end of this lesson, you should be able to:

- Recognize how to manage money

- Judge if it's time to change the way you manage money

- Identify steps you can take to better manage money

- Set financial goals and objectives

How do you manage money?

Every day you make choices about how, where, and when you will spend your money . These choices can have a significant affect on your financial life . Do you spend a lot of money on credit card debt each month? Do you save money regularly? Do you treat yourself to things after a rough week at work?

To get an idea of how you relate to money, take our Money Basics quiz . Choose the answer that most applies to you.

Where does your money go?

If you don't keep track of your expenses , you don't know how you spend your money. When you know where your money goes, you feel more in control. Take time to think about your spending. Ask yourself:

- Do I have a good idea of how much I spend each week or month?

- Do I take care of the essentials first—such as food, utilities, rent, and medical insurance—before spending money on other things?

- Do I have a huge balance on my credit card(s)?

- Am I a savvy shopper?

- Do I save money regularly?

- Do I have three months of living expenses saved?

- Do I have specific goals I'm planning for financially?

Read on to find out how you might change the way you manage your money.

Changing the way you spend money

When assessing how you manage your money, you might want to change your spending and saving habits . Being able to better manage your money will help you prepare for the future.

Bad money management habits can sometimes be difficult to break. To tackle an undesirable habit, consider the following:

- What do I get out of it? If you spend a lot of money but save just a little, what do you get out of it? You get to enjoy stuff, whether it's one more pair of black shoes to add to the five pairs you already own or a new big-screen TV.

- What's the negative? If you go on a shopping spree and don't pay your electric bill, you gain temporary stuff but may lose an important service. If you don't save money, what could happen if an emergency arises? If you look at it this way, you may realize you're not making a good choice.

- Think before you spend. Each time you spend money, you are making a choice. Your choices should reflect your values and financial goals. Before spending, ask yourself, "Do I need it?", "Can I afford it?", and "What is this purchase really costing me?"

- Find a good habit. If you want to get rid of a bad habit related to money management, replace it with a good habit. For example, instead of overspending on designer clothes, start setting aside money for a down payment on a house or other goal. You must truly want to get rid of the bad habit, and you must practice and work at it in order to change.

Eight steps to better money management

As you work toward managing your money more effectively, keep these steps in mind:

1. Plan ahead . Write down your goals and objectives. It's important to be realistic. Will you more likely be able to afford a $200,000 house or one that costs $100,000 or less? Review your goals and objectives regularly to see if you are on track.

2. Create a budget . Make a plan for how you will spend and save money. Update it regularly, and evaluate your goals. Think about your financial situation, where you need to be, and determine how you're going to get there. (You'll learn more about creating a budget in the next lesson.)

3. Keep good records . It's difficult to get your finances under control if you don't understand the basics of good record-keeping. Keeping track of your bills, checks, and other financial transactions is important.

4. Stay insured . Purchase insurance to avoid being hit with a financial loss due to accident or illness. It's an important part of your financial plan.

5. Stay focused . You'll need patience and discipline to start your financial plan and follow through with it. Don't be tempted to overspend.

6. Save more . It's important to save money regularly so you can use it in the future. Begin by faithfully saving a small amount. If you are able to save enough money, you will be able to put some into investments, use it in emergencies, or use it to reach your goals.

7. Educate yourself . No one can protect you from your own bad judgment. Get the information you need to avoid financial trouble, and make thoughtful decisions that can improve your financial security.

8. Take time . Set aside time each month to work on your money management. Pick a time that works for you, such as early in the morning when everyone else is asleep or quiet time at night. You will find that it's time well spent.

Setting goals

Goal setting is an important part of success, whether you're aspiring to reach objectives at school, at work, or in your personal life. Aim too high, and you may get frustrated and give up. Aim too low, and you might not push yourself to reach your full potential.

Think about your financial goals and how you plan to reach them.

- What do you want your financial picture to look like in one year? In five years? In 10 years?

- Do you want to buy a car or house, start a business, or pay off debt?

- What do you need to change to reach your goals?

- How can you make the best use of your money?

Don't worry. You may not have all the answers now. The lessons in this course can help you clearly define your financial goals and help you take steps to achieve them.

To help you get started, use our Goals Worksheet .

/en/moneybasics/creating-a-budget/content/

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.17: Assignment- Problem Set — Money and Banking

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 47487

Click on the following link to download the problem set for this module:

- Money and Banking Problem Set

- Problem Set Assignment: Money and Banking . Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Wage Assignment?

Definition and example of wage assignment, how wage assignment works, wage assignment vs. wage garnishment.

10â000 Hours / Getty Images

A wage assignment is when creditors can take money directly from an employee’s paycheck to repay a debt.

Key Takeaways

- A wage assignment happens when money is taken from your paycheck by a creditor to repay a debt.

- Unlike a wage garnishment, a wage assignment can take place without a court order, and you have the right to cancel it at any time.

- Creditors can only take a portion of your earnings. The laws in your state will dictate how much of your take-home pay your lender can take.

A wage assignment is a voluntary agreement to let a lender take a portion of your paycheck each month to repay a debt. This process allows lenders to take a portion of your wages without taking you to court first.

Borrowers may agree to allow a lender to use wage assignments, for example, when they take out payday loans . The wage assignment can begin without a court order, although the laws about how much they can take from your paycheck vary by state.

For example, in West Virginia, wage assignments are only valid for one year and must be renewed annually. Creditors can only deduct up to 25% of an employee’s take-home pay, and the remaining 75% is exempt, including for an employee’s final paycheck.

If you agree to a wage assignment, that means you voluntarily agree to have money taken out of your paycheck each month to repay a debt.

State laws govern how soon a wage assignment can take place and how much of your paycheck a lender can take. For example, in Illinois, you must be at least 40 days behind on your loan payments before your lender can start a wage assignment. Under Illinois law, your creditor can only take up to 15% of your paycheck. The wage assignment is valid for up to three years after you signed the agreement.

Your creditor typically will send a Notice of Intent to Assign Wages by certified mail to you and your employer. From there, the creditor will send a demand letter to your employer with the total amount that’s in default.

You have the right to stop a wage assignment at any time, and you aren’t required to provide a reason why. If you don’t want the deduction, you can send your employer and creditor a written notice that you want to stop the wage assignment. You will still owe the money, but your lender must use other methods to collect the funds.

Research the laws in your state to see what percentage of your income your lender can take and for how long the agreement is valid.

Wage assignment and wage garnishment are often used interchangeably, but they aren’t the same thing. The main difference between the two is that wage assignments are voluntary while wage garnishments are involuntary. Here are some key differences:

Once you agree to a wage assignment, your lender can automatically take money from your paycheck. No court order is required first, but since the wage assignment is voluntary, you have the right to cancel it at any point.

Wage garnishments are the results of court orders, no matter whether you agree to them or not. If you want to reverse a wage garnishment, you typically have to go through a legal process to reverse the court judgment.

You can also stop many wage garnishments by filing for bankruptcy. And creditors aren’t usually allowed to garnish income from Social Security, disability, child support , or alimony. Ultimately, the laws in your state will dictate how much of your income you’re able to keep under a wage garnishment.

Creditors can’t garnish all of the money in your paycheck. Federal law limits the amount that can be garnished to 25% of the debtor’s disposable income. State laws may further limit how much of your income lenders can seize.

Illinois Legal Aid Online. “ Understanding Wage Assignment .” Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

West Virginia Division of Labor. “ Wage Assignments / Authorized Payroll Deductions .” Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

U.S. Department of Labor. “ Fact Sheet #30: The Federal Wage Garnishment Law, Consumer Credit Protection Act's Title III (CCPA) .” Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

Sacramento County Public Law Library. “ Exemptions from Enforcement of Judgments in California .” Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

District Court of Maryland. “ Wage Garnishment .” Accessed Feb. 8, 2022.

- Pre-Markets

- U.S. Markets

- Cryptocurrency

- Futures & Commodities

- Funds & ETFs

- Health & Science

- Real Estate

- Transportation

- Industrials

Small Business

Personal Finance

- Financial Advisors

- Options Action

- Buffett Archive

- Trader Talk

- Cybersecurity

- Social Media

- CNBC Disruptor 50

- White House

- Equity and Opportunity

- Business Day Shows

- Entertainment Shows

- Full Episodes

- Latest Video

- CEO Interviews

- CNBC Documentaries

- CNBC Podcasts

- Digital Originals

- Live TV Schedule

- Trust Portfolio

- Trade Alerts

- Meeting Videos

- Homestretch

- Jim's Columns

- Stock Screener

- Market Forecast

- Options Investing

- Chart Investing

Credit Cards

Credit Monitoring

Help for Low Credit Scores

All Credit Cards

Find the Credit Card for You

Best Credit Cards

Best Rewards Credit Cards

Best Travel Credit Cards

Best 0% APR Credit Cards

Best Balance Transfer Credit Cards

Best Cash Back Credit Cards

Best Credit Card Welcome Bonuses

Best Credit Cards to Build Credit

Find the Best Personal Loan for You

Best Personal Loans

Best Debt Consolidation Loans

Best Loans to Refinance Credit Card Debt

Best Loans with Fast Funding

Best Small Personal Loans

Best Large Personal Loans

Best Personal Loans to Apply Online

Best Student Loan Refinance

All Banking

Find the Savings Account for You

Best High Yield Savings Accounts

Best Big Bank Savings Accounts

Best Big Bank Checking Accounts

Best No Fee Checking Accounts

No Overdraft Fee Checking Accounts

Best Checking Account Bonuses

Best Money Market Accounts

Best Credit Unions

All Mortgages

Best Mortgages

Best Mortgages for Small Down Payment

Best Mortgages for No Down Payment

Best Mortgages with No Origination Fee

Best Mortgages for Average Credit Score

Adjustable Rate Mortgages

Affording a Mortgage

All Insurance

Best Life Insurance

Best Homeowners Insurance

Best Renters Insurance

Best Car Insurance

Travel Insurance

All Credit Monitoring

Best Credit Monitoring Services

Best Identity Theft Protection

How to Boost Your Credit Score

Credit Repair Services

All Personal Finance

Best Budgeting Apps

Best Expense Tracker Apps

Best Money Transfer Apps

Best Resale Apps and Sites

Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL) Apps

Best Debt Relief

All Small Business

Best Small Business Savings Accounts

Best Small Business Checking Accounts

Best Credit Cards for Small Business

Best Small Business Loans

Best Tax Software for Small Business

Filing For Free

Best Tax Software

Best Tax Software for Small Businesses

Tax Refunds

Tax Brackets

Tax By State

Tax Payment Plans

All Help for Low Credit Scores

Best Credit Cards for Bad Credit

Best Personal Loans for Bad Credit

Best Debt Consolidation Loans for Bad Credit

Personal Loans if You Don't Have Credit

Best Credit Cards for Building Credit

Personal Loans for 580 Credit Score or Lower

Personal Loans for 670 Credit Score or Lower

Best Mortgages for Bad Credit

Best Hardship Loans

All Investing

Best IRA Accounts

Best Roth IRA Accounts

Best Investing Apps

Best Free Stock Trading Platforms

Best Robo-Advisors

Index Funds

Mutual Funds

Personal Finance 101: The complete guide to managing your money

Introduction.

Creating a financially secure life can feel like a daunting task that requires the skills of expert mapmaker and GPS programmer. You need to figure out where you are today and where you want to get to. As if that's not a big enough lift, you're then in charge of finding the best route to get from here to there without veering off into costly detours.

Take a deep breath. Relax your shoulders.

It's just seven steps, and that's doable.

Some goals will take years — if not decades — to reach. That's part of the plan! But you also get an immediate payoff: a whole lot less stress starting the minute you dive into taking control of all the money stuff that's gnawing at you.

According to a 2019 survey, 9 in 10 adults say nothing makes them happier or more confident than having their finances in order. This guide is your ticket to joining in.

This guide lays out the seven key steps to focus on to get you working toward long-term financial security. Follow along from start to finish, or jump to the section(s) you want to learn more about.

Set short-term and long-term goals

Building financial security is an ongoing juggling act. Some of the money balls you have in the air are going to be goals you want to reach ASAP. Other goals might have an end date that is a decade, or decades, off but require starting sooner than later.

Creating a master list of all your goals is a smart first step. It's always easier to plot a course of action when you are clear on what you're looking to achieve.

It's up to you whether your list of short- and long-term goals is on a spreadsheet or pencil to paper. Just be sure to give yourself some quiet time to think it through. Here's a simple prompt: Money-wise, what would make you feel great? At its heart, that's what a financial plan delivers: the means to help you feel safe and secure, so you can focus on living, not worrying.

Possibilities to consider:

- Short-term goals to reach in the next year or so: Build an emergency fund that can cover at least three months of living expenses. Keep new credit card charges limited to what you can pay off, in full, each month. Hint: Create and follow a budget. Pay off existing credit card balances.

- Longer-term goals: Start saving at least 10% of gross salary every year for your retirement. Save for a home down payment . Save for a child's (or grandchild's) education in a tax-advantaged 529 Plan .

Create a budget

Not exactly a sexy topic. Agreed. But creating a budget happens to be the one step that makes every other financial goal reachable.

A budget is a line-item accounting of all your income — salary, maybe a side gig, perhaps income from an investment — and all your expenses. The whole purpose of a budget is to lay everything out in front of you so you can see where everything is going and make some tweaks if you're not currently on course to meet your goals.

One way to analyze your current cash flow is to run it through the popular 50/30/20 budgeting framework.

With this approach, the goal is to spend 50% of your after-tax income on essential costs (e.g., rent/mortgage, food, car payments) and 30% on other needed expenses (say, phone and streaming plans) or "nice to haves" such as dining out. The final 20% is for savings: building your emergency reserves, socking away money for retirement and saving up enough funds for a down payment on a house or your next car.

Another framework is the 60% Solution , which divvies up spending and saving targets a bit differently — but with the same focus on making sure you don't shortchange saving for long-term goals.

If your own pie charts look wildly different than either approach, that's your cue to spend some time considering how to adjust your spending or increase your income. (Hello, side gig! Or push for that promotion or raise already.) That will get you on a solid path that helps you meet short-term and long-term goals.

You can fire up an Excel or Google Docs spreadsheet to help you create a budget and track your progress. There are also budgeting apps you can sync with bank accounts that can make it easier to track spending in real time.

Build an emergency fund

Okay, you likely need no convincing that having some money tucked away for life's endless stream of financial curveballs — pandemic layoff, the deductible for an MRI on the knee you wrenched, replacing whatever the mechanic tells you is the reason your car is acting up — is perhaps the ultimate money stress reducer.

But how to create your safety cushion? You've got plenty of stressed-out company. A survey by Bankrate.com found that 60% of people say they don't have enough money saved to cover a $1,000 emergency bill. And just one grand isn't likely even enough. Bankrate said that, among survey participants who had an emergency in 2019, the average tab was $3,500.

Building an emergency fund starts with setting a goal for how much protection you want to build. At a minimum, it's smart to have at least three months' worth of living expenses saved in an emergency account; six is even better.

Can't even imagine pulling that off? Stop focusing on the big end-goal. The trick with this is to create an automated system that adds money to your emergency fund each month.

The best way to achieve this is to open a separate bank or credit union savings account that you designate as your emergency fund. (Keeping this money in your regular checking account introduces the temptation to use the money for non-emergencies.)

Online savings banks typically pay the highest yields. You can open a high-yield online savings account and set up an automatic transfer from your checking account into it. For even less temptation to spend, decline the debit card the online bank might offer you.

Pay off costly credit card debt

The unofficial term for the interest rate charged on unpaid credit card balances is "insane." While it's common for banks to pay savers less than 1% interest these days on savings accounts, the average interest rate they charge credit card users with an unpaid balance is pushing 17%.

Paying off high-rate debt is one of the best investment moves, and the average 17% interest rate charged on unpaid credit card balances is a big roadblock to building financial security

If you have a solid credit score, you might consider checking if you can qualify for a balance transfer deal to a new card that will waive interest payments for an initial period. Not having to pay any interest for a year, or more, gives you a chunk of time to make a big dent in repayment without interest continuing to pile up.

If a balance transfer isn't in the cards for you, there are two popular get-out-of-debt strategies you might consider.

From a financial standpoint, the "avalanche" method makes the most sense. You pay the minimum due each month on all your credit cards, and then add more money to the card charging the highest interest rate. When the balance on your highest-rate card is paid off, you start shoveling the extra payments to the card with the next-highest interest rate. Rinse and repeat.

Stymied as to where you can find the extra money to add to the highest-rate card? Time to scour that budget you've got running in the background. Maybe an expense gets totally chopped, or maybe you do some strategic nipping and tucking to reduce monthly outlays for some of your expenses.

With the "snowball" strategy, on the other hand, you send your extra monthly payments to the card with the smallest unpaid balance. The allure of this pay-back method is that it provides a nice bit of psychological mojo: By focusing on the card with the smallest balance, you'll get it paid off faster. Seeing a card balance hit zero can be valuable motivation … if you need it. Otherwise, the avalanche system actually will save you more money.

Save for retirement

Even if you have decades to go until retirement, the time to get started saving was yesterday. The longer you wait to get serious about this big honking goal, the more you will need to contribute to land in retirement in good shape.

There's no one rule for how much you'll want (read: need) to save for retirement, but a solid guideline is to have a multiple of your salary set aside at different ages. As you can see below, having retirement account balances equal to two times your salary by age 35 sets you up for success. When you're 50, the aim is to have six times your salary in retirement account, and by your late 60s, having 10 times your salary saved up is recommended.

The best way to save for retirement is to use special accounts that give you valuable tax breaks. Many workplaces offer retirement accounts that you contribute to, such as 401(k) and 403(b) plans — the former by private employers, the latter by nonprofits and the government. And everyone with earned income can contribute to their own individual retirement account — or IRA, for short. Many brokerages offer IRAs.

With both 401(k)/403(b) plans and IRAs, you may be able to choose between a "traditional" account or a "Roth" account. The difference is when you grab your tax break.

With traditional 401(k) and 403(b) accounts, you get an upfront tax break: Your contribution reduces your taxable income for the year. Traditional IRA accounts may also qualify for this upfront tax break, depending on your income. When you eventually make withdrawals from traditional retirement accounts, you owe income tax on every dollar you withdraw.

Roth 401(k) plans and IRAs deliver the tax break in retirement. The money you contribute today doesn't reduce your current income and your contribution is made with after-tax dollars. But when you make withdrawals in retirement, there will be no tax owed.

There are lots of moving pieces to nailing saving for retirement. Here are some key steps to take at different life stages.

- Start saving at least 10% of your gross salary ASAP. Saving 15% is even better . If you wait until your 30s to get serious about this, you'll likely need to save 20% or more of your salary to reach your retirement target. If you can't get to 10% right out of the gate, commit to a plan to boost your contribution rate at least one percentage point a year.

- Don't pass up a workplace retirement saving bonus . If you have a workplace plan, chances are you were "auto-enrolled." So far, so good. But there's a trap, too: Lots of plans automatically set your initial contribution rate at a level that is too low to qualify for the maximum matching contribution they offer to all employees. Grrr! Check with human resources that you are contributing at least enough to get the maximum match.

- No workplace plan? Check out IRAs. If you are an independent contractor/perma-gig worker, you qualify for a SEP IRA, which allows savers to contribute more each year than regular IRAs. That said, SEP IRAs only come in the traditional format; there is no Roth version of a SEP IRA. By the way, officially, SEP IRA is a Simplified Employee Pension Individual Retirement Arrangement.

- Consider saving in a Roth. Chances are you've yet to hit peak earnings, right? That means you've also probably not hit your peak income-tax rate, either. When you are in a lower tax bracket, a Roth 401(k) or a Roth IRA can make a lot of sense, given there's not a big value in getting the upfront tax break from a traditional account. Anyone can contribute to a Roth 401(k) or 403(b) if the plan offers it, but there is an income cutoff (it's pretty high) to be eligible to save in Roth IRA.

- Just getting started? Aim to contribute 15% of your gross salary.

- Don't cash out when you job-hop. If you have a workplace retirement plan, you are allowed to move the money when you leave the job. One option is to take the money as cash. This is a seriously bad move. Not only will you trigger a 10% IRS penalty, but you may also owe income tax. And most important: You've just stolen from your future self, who is going to need that money in retirement. Leave the money where it is, or consider a 401(k) rollover.

- Fire up an online retirement calculator . Now's the time to see if you're in the ballpark of where you want to be in 20 or so years. If you're coming up short, start picking apart your budget (and lifestyle) to find ways to save more. By your 40s, most financial advisors recommend having two to three times your annual salary saved in retirement funds.

- Prioritize retirement over paying for college . Cold-hearted? Ruthless? Not if you work with your kid to focus on schools that are a good financial fit. Hint: It's all about the net price— that doesn't require you to raid your retirement account or slow down on your savings. That reduces the odds the kids will need to support you in retirement.

- Steer clear of lifestyle creep . Yep, you're making more now than in your 20s but, um, are you spending it all?

- Here are some numbers to consider. By age 50, experts say to have six times your salary saved. By age 55, have seven times your salary saved.

- Get an estimate of your retirement income. There are online calculators that can help you hammer out a sense of how much monthly income you may be able to safely generate from your retirement savings, Social Security check and pension benefit — if you have one.

- Consider bringing in a pro to strategize. You may enjoy being a DIY retirement saver. But given all the moving parts in hatching a successful retirement income plan, you might consider consulting with a certified financial planner to work through your retirement income plan. There are many planners who charge a flat or hourly fee for a specific assignment. Or you might want to consider hiring a pro on an ongoing basis to help you manage your finances throughout your retirement.

- Take advantage of catch-up contributions. Once you cross the retirement savings Rubicon that is the half-century mark, the annual contribution limits for IRAs and 401(k)/403(b) plans rise. If a spin through an online retirement income calculator didn't deliver the numbers you'd like, stuff more money into your accounts now.

- Build tax diversification. If you've done most of your workplace retirement savings in traditional accounts, you might want to consider spending a few years saving in a Roth equivalent, if your plan offers one. Retirement planning experts recommend adding some Roth retirement savings as a way to create "tax diversification" that can help keep your IRS tab down once you retire.

- Check if these numbers add up. By age 60, have eight times your salary saved. By age 67, have 10 times your salary saved.

- Consider waiting to claim Social Security. You can start collecting your retirement benefit at age 62. Every month you delay past 62 earns you a higher eventual payout. Wait until age 70 and your payout will be 76% higher than what you'd get if you claim eight years earlier.

- Earn just enough to avoid starting retirement account withdrawals. If you want (and can) continue to work full-time at a fast-paced job, that's great. But if you're ready to downshift or you were pushed out of your career, a practical strategy may be to work at a job that brings in enough to cover your living expenses, even if you can't afford to continue to add to your retirement savings. At this point, giving what you have already saved more time to compound before starting withdrawals is a smart move.

Invest for retirement with a long-term focus

What you manage to save for retirement is the biggest factor in how comfy you're going to be when it's time to step off the work treadmill. But how you invest the money in your retirement accounts plays a large role, too.

Saving for retirement breaks down into how much you want to invest in stocks and how much in bonds. As if this needed pointing out now, stocks can be volatile at times, though over long periods (10 years or more) they have historically delivered higher returns than bonds.

Bonds are more chill. They don't fall like stocks in rough times — in fact, they typically rise when stocks are cratering. However, they don't gain as much as stocks, either.

A hidden risk to consider when you are deciding on your mix of stocks and bonds is inflation. That's the annoying fact that, over time, stuff costs more. Even at a benign 2% inflation rate, what costs $1,000 today will cost more than $1,600 in 25 years. Stocks over long stretches have produced the best inflation-beating gains.

The right stock-bond mix depends on your personal goals, stomach for risk and time horizon — or number of years you expect to hold your investments. Jack Bogle, renowned founder of Vanguard and tireless advocate for individual investors, suggested this simple rule of thumb: Subtract your age from 110. That's how much, percentage-wise, you might want to keep in stocks.

Borrow smart

Big-ticket purchases typically involve taking out a loan. The house you want to buy. The cars you drive. Helping your kids pay for college.

The key to building financial security is to only borrow what you truly need. And that can get tricky because right when you are looking to buy a house/car/college education, the lenders are focused on telling you the maximum you are allowed to borrow. No one is going to look you in the eye and suggest you borrow less. Lenders have no clue, or interest, in how the loan they are dangling in front of you impacts your ability to meet all your other goals.

That's on you. Your goal should always be to borrow as little as possible to meet your goal. The less you borrow, the more money you have for other goals. You need a car? Okay, but do you need a new car tricked out with every premium package? Might your financial life benefit from considering a less expensive model? Buying a used car that has been on the road for three or so years means you're letting someone else pay for the 40% to 50% depreciation that is common in the early years after buying a new car.

Same goes with the house. A recent study found that the median price of a four-bedroom home was $100,000 more than a three-bedroom. Or consider a slightly longer commute, which can also be a big money saver.

Borrowing as little as possible is how you free up hundreds of dollars in your budget to put toward other goals.

Once you determine your maximum borrowing budget, doing some advance prep work to get your credit score as high as possible can help you qualify for the best deal.

Personal Finance 101

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Money Laundering?

- How It Works

Types of Transactions

Electronic money laundering, the bottom line.

- Financial Crime & Fraud

- Definitions M - Z

The prevention of money laundering has become an international effort

James Chen, CMT is an expert trader, investment adviser, and global market strategist.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/photo__james_chen-5bfc26144cedfd0026c00af8.jpeg)

Money laundering is an illegal activity that makes large amounts of money generated by criminal activity, such as drug trafficking or terrorist funding, appear to have come from a legitimate source. The money from the criminal activity is considered dirty, and the process “launders” it to look clean. Financial institutions employ anti-money laundering (AML) policies to detect and prevent this activity.

Key Takeaways

- Money laundering disguises financial assets without detecting the illegal activity that produced them.

- Online banking and cryptocurrencies have made it easier for criminals to transfer and withdraw money without detection.

- The prevention of money laundering has become an international effort that includes terrorist funding among its targets.

- The financial industry also has its own set of strict anti-money laundering (AML) measures in place.

Investopedia / Julie Bang

How Money Laundering Works

Money laundering is essential for criminal organizations that use illegally obtained money. Criminals deposit money in legitimate financial institutions to appear as if it comes from legitimate sources. Laundering money typically involves three steps although some stages may be combined or repeated.

- Placement: Injects the “dirty money” into the legitimate financial system.

- Layering: Conceals the source of the money through a series of transactions and bookkeeping tricks.

- Integration: Laundered money is disbursed from the legitimate account.

The Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) requires financial institutions to keep records of cash purchases of negotiable instruments, file reports of cash transactions exceeding $10,000, and report suspicious activity that might signal money laundering.

- Structuring or Smurfing : Large allotments of illegally obtained cash are divided into multiple small deposits and spread over many different accounts

- “Mules” or cash smugglers: Cash is smuggled across borders and deposited into foreign accounts

- Investing in commodities: Using gems and gold that can be moved easily to other jurisdictions

- Buying and Selling: Using cash for quick turnaround investment in assets such as real estate, cars, and boats

- Gambling: Using casino transactions to launder money

- Shell companies : Establishing inactive companies or corporations that exist on paper only

The rise of online banking institutions, anonymous online payment services, and peer-to-peer (P2P) transfers with mobile phones have made detecting the illegal transfer of money increasingly difficult. Proxy servers and anonymous software make the third component of money laundering, integration, difficult to detect as money can be transferred or withdrawn with little or no trace of an Internet protocol (IP) address.

Money can be laundered through online auctions and sales, gambling websites, and virtual gaming sites, where ill-gotten money is converted into gaming currency, then back into real, usable, and untraceable “clean” money.

Money laundering may involve cryptocurrencies , such as Bitcoin . While not completely anonymous, they can be used in blackmail schemes, the drug trade, and other criminal activities due to their relative anonymity compared with fiat currency .

AML laws have been slow to catch up to cybercrime since most laws are still based on detecting dirty money as it passes through traditional banking institutions and channels.

According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, global money-laundering transactions account for roughly $800 billion to $2 trillion annually, or 2% to 5% of global gross domestic product (GDP) . In 1989, the Group of Seven (G-7) formed an international committee called the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to fight money laundering on an international scale. In the early 2000s, its purview was expanded to include terrorist activity.

The United States passed the Bank Secrecy Act in 1970, requiring financial institutions to report cash transactions above $10,000 or unusual activity on a suspicious activity report (SAR) to the Department of the Treasury . This information is used by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to be shared with domestic criminal investigators, international bodies, or foreign financial intelligence units.

Money laundering was deemed illegal in the United States in 1986, with the passage of the Money Laundering Control Act. After Sept. 11, 2001, the USA Patriot Act expanded money laundering efforts. The Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) offers a professional designation known as a Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialist (CAMS) . These individuals work as brokerage compliance managers, Bank Secrecy Act officers, financial intelligence unit managers, surveillance analysts, and financial crimes investigative analysts.

What Is an Example of Money Laundering?

Cash earned illegally from selling drugs may be laundered through highly cash-intensive businesses such as a laundromat or restaurant where the illegal cash is mingled with business cash before deposit. These types of businesses are often referred to as “fronts.”

What Are Signs of Money Laundering?

Money laundering red flags include suspicious or secretive behavior by an individual around money matters, making large transactions with cash , owning a company that seems to serve no real purpose, conducting overly complex transactions, or making several transactions just under the reporting threshold.

How Is Real Estate Used for Money Laundering?

Criminals use real estate transactions, including undervaluation or overvaluation of properties, buying and selling properties rapidly, using third parties or companies that distance the transaction from the criminal source of funds, and private sales.

How Are Cryptocurrencies Used in Money Laundering?

The U.S. Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) noted in a June 2021 report that convertible virtual currencies (CVCs) , or cryptocurrencies, are a currency of choice in various online illicit activities. CVCs can layer transactions and obfuscate the origin of money derived from criminal activity. Criminals use several money-laundering techniques involving cryptocurrencies, including “mixers” and “tumblers” that break the connection between an address or crypto “wallet” sending cryptocurrency and the address receiving it.

Money laundering disguises illegally obtained financial assets. Global governments and financial institutions have anti-money laundering measures in place. Online activity and digital assets have added to money laundering transactions.

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. “ Money Laundering .”

Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. “ Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) .”

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “ History of Anti-Money Laundering Laws .”

Financial Action Task Force. “ History of the FATF .”

Congressional Research Service. " U.S. Efforts to Combat Money Laundering, Terrorist Financing, and Other Illicit Financial Threats: An Overview ." Page 2.

Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists. “ Start Your CAMS Journey Today: CAMS Frequently Asked Questions ." Select "The CAMS Certification."

Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada. “ Operational Brief: Indicators of Money Laundering in Financial Transactions Related to Real Estate .”

Financial Crimes Enforcement Network. “ Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism National Priorities .” Page 5.

- What Is Fraud? Definition, Types, and Consequences 1 of 31

- What Is White-Collar Crime? Meaning, Types, and Examples 2 of 31

- What Is Corporate Fraud? Definition, Types, and Example 3 of 31

- What Is Accounting Fraud? Definition and Examples 4 of 31

- Financial Statement Manipulation 5 of 31

- Detecting Financial Statement Fraud 6 of 31

- What Is Securities Fraud? Definition, Main Elements, and Examples 7 of 31

- What Is Insider Trading and When Is It Legal? 8 of 31

- What Is a Pyramid Scheme? How Does It Work? 9 of 31

- Ponzi Schemes: Definition, Examples, and Origins 10 of 31

- Ponzi Scheme vs. Pyramid Scheme: What's the Difference? 11 of 31

- What Is Money Laundering? 12 of 31

- How Does a Pump-and-Dump Scam Work? 13 of 31

- Racketeering Definition, State vs. Federal Offenses, and Examples 14 of 31

- Mortgage Fraud: Understanding and Avoiding It 15 of 31

- Wire Fraud Laws: Overview, Definition and Examples 16 of 31

- The Most Common Types of Consumer Fraud 17 of 31

- Who Is Liable for Credit Card Fraud? 18 of 31

- How to Avoid Debit Card Fraud 19 of 31

- The Biggest Stock Scams of Recent Time 20 of 31

- Enron Scandal: The Fall of a Wall Street Darling 21 of 31

- Bernie Madoff: Who He Was, How His Ponzi Scheme Worked 22 of 31

- 5 Most Publicized Ethics Violations by CEOs 23 of 31

- The Rise and Fall of WorldCom: Story of a Scandal 24 of 31

- Four Scandalous Insider Trading Incidents 25 of 31

- What Is the Securities Exchange Act of 1934? Reach and History 26 of 31

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Defined, How It Works 27 of 31

- Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) Overview 28 of 31

- Anti Money Laundering (AML) Definition: Its History and How It Works 29 of 31

- Compliance Department: Definition, Role, and Duties 30 of 31

- Compliance Officer: Definition, Job Duties, and How to Become One 31 of 31

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/AML-7a3c35887ed946d1ba9cb56fae105db5.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The money supply is the total amount of money available in an economy at any given time. It's important to study this supply so that we can understand how accessible money is in our system. Because money can exist in different forms and in different kinds of accounts, it can be more or less liquid. Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards ...

Time Value of Money - TVM: The time value of money (TVM) is the idea that money available at the present time is worth more than the same amount in the future due to its potential earning capacity ...

First, they are extremely durable—lasting a century or more. As the late economic historian Karl Polyani put it, they can be "poured, sacked, shoveled, hoarded in heaps" while remaining "clean, dainty, stainless, polished, and milk-white.". Second, parties could use cowries either by counting shells of a certain size, or—for large ...

Expert-verified. a) A = P (1 + rt) A = 1000 ( …. Ch 05: Assignment - Time Value of Money 1. Simple versus compound interest Financial contracts involving investments, mortgages, loans, and so on are based on either a fixed or a variable interest rate. Assume that fixed interest rates are used throughout this question.

The balance sheet for one of these banks, Acme Bank, is shown in Table 24.2 "A Balance Sheet for Acme Bank". The required reserve ratio is 0.1: Each bank must have reserves equal to 10% of its checkable deposits. Because reserves equal required reserves, excess reserves equal zero. Each bank is loaned up.

Don't be tempted to overspend. 6. Save more. It's important to save money regularly so you can use it in the future. Begin by faithfully saving a small amount. If you are able to save enough money, you will be able to put some into investments, use it in emergencies, or use it to reach your goals. 7. Educate yourself.

Velocity Of Money: The velocity of money is the rate at which money is exchanged from one transaction to another and how much a unit of currency is used in a given period of time. Velocity of ...