Pros and Cons for Healthy Food Choices

Eating healthy can help you sustain wellness, achieve longevity and prevent chronic diseases that are costly to treat. Despite public health promotion to eat healthy foods, only 23 percent of Americans consume the daily recommended amounts of fruits and vegetables, according to the 2010 Annual Status Report of the National Prevention, Health Promotion and Public Health Council. Healthy food choices abound in most cities, yet they can be hard to find in restaurants and may be perceived to be costlier than processed foods.

Advertisement

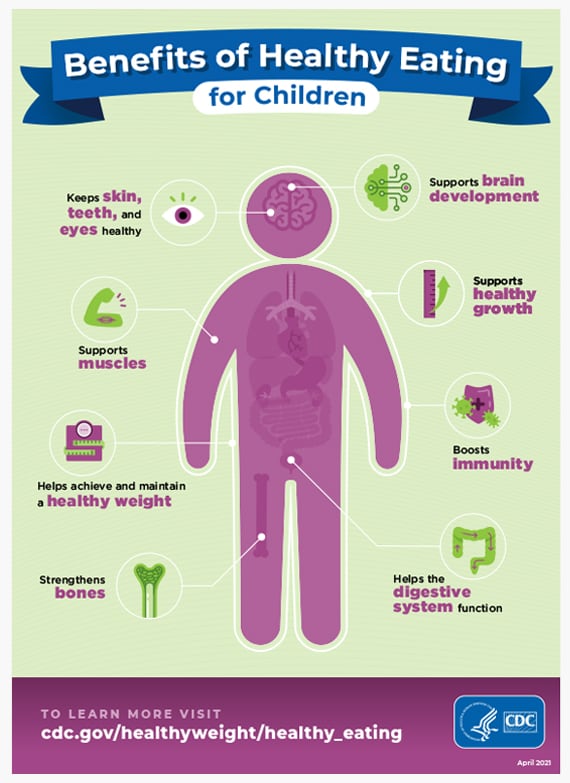

Pro: Promotes Health

Video of the Day

Consuming healthy foods can improve your overall health. Healthy foods are whole, organically grown without pesticides, unprocessed and include fresh fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, seeds, grains and olive and vegetable oils. Healthy foods for people who eat animal products include moderate amounts of low-fat dairy and cold water, fatty fish, such as salmon and light tuna and low amounts of lean meat and poultry. These foods may promote health and increase your longevity. Healthy food choices include products that contain calcium for bone growth, antioxidants to slow down the aging process and healthy fats to maintain cellular and cardiovascular health.

Pro: Reduces Risk of Disease

Healthy foods reduce your risk of chronic diseases. Low glycemic foods, such as barley, grapefruits and chickpeas, help you control blood sugar levels and may reduce your risk of diabetes and complications, such as nerve damage. Healthy fats, such as monounsaturated fatty acids from olive oil and omega-3 fatty acids from walnuts and fish, may reduce your risk of cardiovascular disease.Fruits and vegetables contain an abundance of antioxidants, which may reduce your risk of cancer. Dairy and soy foods contain calcium, which can reduce your risk of osteoporosis.

Con: Not Always Easy to Find

Healthy food choices are not always easy to find, particularly at restaurants. Many fast food restaurants cook with trans fats, industrial processed hydrogenated vegetable oils that can increase your risk of heart disease. Many of the food choices on restaurant menus include foods with high amounts of calories, sodium and saturated fat. To eat healthy, order a salad with dressing on the side.

A common perception among people who do not shop at health food stores is that health foods are more expensive than similar products in mainstream grocery stores. The truth is that many gourmet brands of health foods are costly, yet there are less-expensive health food brands of products. Buying organic produce can be expensive, but can be less costly when grown locally. Eating healthier, sometimes costlier foods, may help you save more tomorrow on not having to pay for health care expenses from treating chronic diseases that may result from eating unhealthy foods. Research at Harvard School of Public Health published in the "Journal of the American College of Nutrition" in 2008 demonstrates that people who are introduced to healthy foods and subsidized 20 percent of the cost increased their consumption of healthy foods after the subsidy was removed.

- Public Health Council: 2010 Annual Status Report

- Harvard School of Public Health: Mediterranean Diet

- Linus Pauling Institute: Glycemic Index

- MayoClinic.com: Dietary Fats

- National Cancer Institute: Antioxidants and Cancer Prevention: Fact Sheet

- University of Maryland Medical Center: Calcium

- University of Maryland Medical Center: Trans Fats 101

- "Journal of the American College of Nutrition"; K.B. Michaels, et al.; Feb. 27, 2008

Report an Issue

Screenshot loading...

- Research article

- Open access

- Published: 06 September 2021

Unhealthy lifestyles, environment, well-being and health capability in rural neighbourhoods: a community-based cross-sectional study

- Anabela Marisa Azul ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3295-1284 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Ricardo Almendra 4 , 5 ,

- Marta Quatorze 6 ,

- Adriana Loureiro 4 ,

- Flávio Reis 2 , 6 , 7 , 8 ,

- Rui Tavares 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Anabela Mota-Pinto 6 , 9 ,

- António Cunha 10 , 11 ,

- Luís Rama 12 ,

- João Oliveira Malva 2 , 6 , 7 , 11 ,

- Paula Santana 4 , 5 ,

- João Ramalho-Santos 1 , 2 , 13 &

HeaLIQs4Cities consortium

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 1628 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

4 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Non-communicable diseases are a leading cause of health loss worldwide, in part due to unhealthy lifestyles. Metabolic-based diseases are rising with an unhealthy body-mass index (BMI) in rural areas as the main risk factor in adults, which may be amplified by wider determinants of health. Changes in rural environments reflect the need of better understanding the factors affecting the self-ability for making balanced decisions. We assessed whether unhealthy lifestyles and environment in rural neighbourhoods are reflected into metabolic risks and health capability.

We conducted a community-based cross-sectional study in 15 Portuguese rural neighbourhoods to describe individuals’ health functioning condition and to characterize the community environment. We followed a qualitatively driven mixed-method design to gather information about evidence-based data, lifestyles and neighbourhood satisfaction (incorporated in eVida technology), within a random sample of 270 individuals, and in-depth interviews to 107 individuals, to uncover whether environment influence the ability for improving or pursuing heath and well-being.

Men showed to have a 75% higher probability of being overweight than women ( p -value = 0.0954); and the reporting of health loss risks was higher in women (RR: 1.48; p -value = 0.122), individuals with larger waist circumference (RR: 2.21; IC: 1.19; 4.27), overweight and obesity (RR: 1.38; p -value = 0.293) and aged over 75 years (RR: 1.78; p -value = 0.235; when compared with participants under 40 years old). Metabolic risks were more associated to BMI and physical activity than diet (or sleeping habits). Overall, metabolic risk linked to BMI was higher in small villages than in municipalities. Seven dimensions, economic development, built (and natural) environment, social network, health care, demography, active lifestyles, and mobility, reflected the self-perceptions in place affecting the individual ability to make healthy choices. Qualitative data exposed asymmetries in surrounding environments among neighbourhoods and uncovered the natural environment and natural resources specifies as the main value of rural well-being.

Conclusions

Metabolic risk factors reflect unhealthy lifestyles and can be associated with environment contextual-dependent circumstances. People-centred approaches highlight wider socioeconomic and (natural) environmental determinants reflecting health needs, health expectations and health capability. Our community-based program and cross-disciplinary research provides insights that may improve health-promoting changes in rural neighbourhoods.

Peer Review reports

Non-communicable diseases (NCD) are the leading causes of health loss globally, accounting for 91% of deaths and almost 87% of disability-adjusted-life-years (DALYs) in Europe [ 1 ], in part due to unhealthy diets and lifestyles [ 2 , 3 ]. A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease [ 4 ], undertaken by the World Health Organisation (WHO) and the Institute for Health, Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) highlight three metabolic risks among the five leading risks of DALYs worldwide: i) high systolic blood pressure (SBP), ii) high fasting plasma glucose and iii) body-mass index (BMI). In parallel, in 2019, a large-scale study including more than 112 million adults across urban and rural neighbourhoods estimated that BMI increased 2.1 kg/m 2 in both women and men in rural neighbourhoods over the past three decades; suggesting that the rising of rural BMI is currently the main health risk factor in adults [ 5 ].

Health loss risks in rural neighbourhoods may be amplified by wider determinants of health and well-being such as the geographic and historical factors across economic and socio-cultural characteristics [ 6 ]. Places are living organisms that produce dynamics, generate environments and create societies [ 7 , 8 ] They are a set of multiple, complex and overlapping environments that support life (e.g., home, social relationships, communities and neighbourhoods) [ 9 ]. The exposure to positive or negative environments, that occur in particular geographic locations, influence human health and well-being throughout the course of life [ 10 , 11 ]. Problems related with built, connective, and relational space present themselves when spatial planning and development models cannot be adjusted in face of a changing landscape, for instance, ageing phenomena [ 12 ]. A growing elderly population accentuates the ability to pursue health in place due to a combination of physical–cognitive and functional–social and psychological fragility [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ].

Communities have a deep understanding of their surrounding environments enabling them to better assess external factors [ 13 , 14 ] impacting health and the ability to make healthy choices. Comprehensive theories of health and social justice [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] intersect individual-level data and broader structural and environmental circumstances, for mapping the conditions that reflect health needs, health expectations and health capability gaps at both individual and community levels. In this way, Ruger’ health capability mode of 2010 [ 18 ] includes the capability to reduce/prevent the exposure to metabolic risks factors, to reduce DALYs and early mortality, to pursue healthy lifestyles, or to gain health-related knowledge, which is viewed both as an end for individuals (intrinsic motivation) but also as a driving force for encouraging changes at the community level, e.g., socioeconomic development, built and natural environment, or social cohesion, particularly in rural areas [ 20 ].

Self-management of NCD remains poorly implemented in rural neighbourhoods despite self-adherence to healthy lifestyles evidence reflected in self-ability to make balanced decisions [ 21 , 22 ]. The community-based participatory research (CBPR) is a wide-ranging methodological approach that concedes the possibility of exploring gaps between what is expected and what is afforded and its interconnections and interdependencies [ 23 ], while evidence-based data can be helpful for assessing an individual’s health functionality. Therefore, we propose a qualitatively driven mixed-method design to assess unhealthy lifestyles of people living in rural neighbourhoods, which includes gathering evidence-based data about metabolic risks and health functionality and studying broader contextual determinants of health and well-being associated to place and neighbourhood. We ultimate expect to uncover health and well-being drivers in rural neighbourhoods, and determine whether community circumstances influence health capability at both the individual and community-level.

Study area, design and community setting

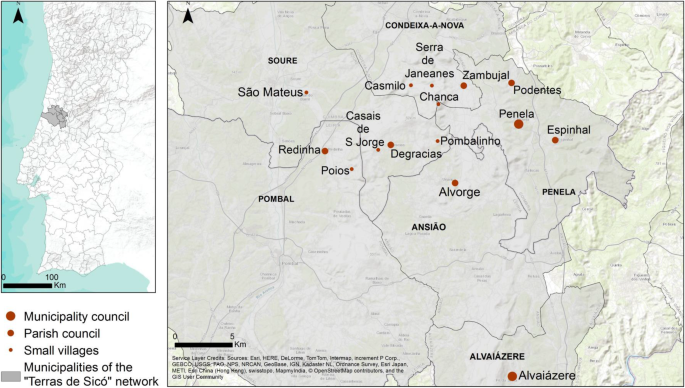

The cross-sectional study was conducted in 15 rural neighbourhoods from six municipalities in the Centre region of Portugal (Fig. 1 ), aiming at 1) assessing evidence-based data and describing lifestyles, 2) examining determinants of health and well-being in rural neighbourhoods, and 3) discuss how individuals’ conditions and population’ circumstances can contribute with a better understanding to improve health capability in rural neighbourhoods.

Location of rural neighbourhoods; basemap is provided by ESRI, available as part of the mapping platform ArcGIS Online

The selection of the rural neighbourhoods of the “ Terras de Sicó ” ( Lands of Sicó ) network (Sicó-network) was drawn on a CBPR approach. Given possible differences at the administrative level, which could influence local practices, we considered the three relevant levels of territory administrative structure: small villages, parish councils, and municipalities seats (hereinafter referred as municipality) (Fig. 1 ). According to the Portuguese National Statistics Institute, in 2011, 3879 individuals were living in the 15 rural neighbourhoods (Table 1 ), one third of the population was older than 64 years and with a high rate of limited literacy (e.g., the proportion of individuals that do not know how to read is almost the same as individuals with higher education); which are common characteristics in Portuguese rural areas [ 24 ].

The study encompasses a qualitatively driven mixed-method design, that is, simultaneously, qualitative (QUAL; inductive theoretical drive) and quantitative (quan): QUAL+quan [ 25 ]: quan to describe and examine individuals’ health functioning condition (evidence-based data and lifestyles); QUAL to document how individuals experience their neighbourhood in terms of health and well-being [ 26 ], and to better understand which local circumstances influence the ability to adopt healthier lifestyles and to pursue health [ 18 ].

Our CBPR approach involved the local representatives from the Sicó-network ( n = 20; among policymakers, local community members and stakeholders); advanced training students and young professionals ( n = 13), from biomedical sciences, medicine and sports sciences; a trans-disciplinary research and innovation team ( n = 18) involving researchers from life sciences, medical and health sciences, and social sciences, and developers of advanced technology for health monitoring and e-health services, including two international members of the HeaLIQs consortium and two members of the consortium Ageing@Coimbra. Two local consolidation meetings with local representatives of the Terras de Sicó network and the research and innovation team, held in two municipalities, Penela (May 28, 2019) and Alvaiázere (June 11, 2019), created the bases of the CBPR approach, and a roadmap for local itineraries and local community engagement. Triangulation between local representatives and researchers regarding the CBPR approach contributed to: better characterizing the demography in the 15 neighbourhoods; co-designing the community program adapted to each neighbourhood; co-constructing a health communication strategy and tailored healthy lifestyles-related messages for older adults with limited literacy; discussing the theoretical background [ 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 ] and the QUAL+quan methodology connecting with a questionnaire [ 27 ] incorporated in pre-existing eVida technology [ 28 ]; and training volunteer students and young professionals to operationalize translational research and participatory approaches with community engagement in neighbourhoods. Local representatives collaborated actively in the dissemination of the program via national/regional media (i.e., newspapers, radio, television and flyers), social media (i.e., Facebook) and institutional websites (e.g., Sicó-network, municipalities, local stakeholders and university). Overall, the design took about 9 months, from January to September 2019.

Mobile healthy living room

The community program took place in a mobile Healthy Living Room (mHLR) (Fig. 2 ), designed as a mobile community service, to reach isolated rural neighbourhoods with lower access to health care facilities and awareness about healthy lifestyles. The mHLR was equipped with a healthy lifestyle assessment toolkit, which comprises medical devices and a questionnaire [ 27 ] incorporated in eVida technology. eVida is a tablet-based application centred on the input of the questionnaires (as discussed in detail below), provides a personalized summary of putative health risks associated with individual characteristics and behaviours [ 28 ].

Community program intervention design; credits: the research team

The community intervention involved 1) the assessment of evidence-based data (e.g., BMI, waist circumference, and self-assessment of illnesses or chronic diseases, medication and sleep habits), 2) lifestyle characterization (e.g., diet, active lifestyles, quality of life and self-assessment of health and well-being), 3) demographic information (i.e., sex, age, employment status and level of education), complemented with 4) the self-assessment of neighbourhood satisfaction, all incorporated in eVida technology, and 5) the individual in-depth interview about the contexts in place to pursue good health in the neighbourhood. Each participant was accompanied by a trained team member and community intervention included two to four team members and four to six students/young professionals, depending on the neighbourhoods’ population.

At the end, participants received the results of the eVida questionnaire and prevention recommendations in an individualised report as well as short cartoon-like active healthy lifestyles messages, about diet, physical activity, social cohesion, and mental health and well-being.

This research was part of a collaborative European research project, Healthy Lifestyle Innovation Quarters for Cities and Citizens (HeaLIQs4Cities), funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology for Health (EIT Health), that unite researchers and neighbourhoods from Coimbra (Portugal), Groningen (The Netherlands) and Copenhagen (Denmark), around the concept of health capability and drivers of health and well-being. Among the stakeholders, the consortium Ageing@Coimbra represents a reference site in Centro region of Portugal within the European Innovation Partnership (EIP) on Active and Healthy Ageing (AHA), that is founded on a quadruple helix-based innovation model for improving active and healthy ageing in Europe [ 28 ].

Data collection

One dimension of the data aimed at collecting evidence-based data, lifestyles and self-assessment of neighbourhood satisfaction incorporated in eVida, as mentioned above, while another dimension of the data aspired at documenting the contexts in place influencing the ability to pursue health and well-being in the neighbourhood. The weight and waist circumference were measured and BMI assessed; the factors associated with illnesses or chronic diseases, medication, and sleep habits were self-reported. The quality of life followed EQ-5D-5L questionnaire: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression (each dimension is rated on scale with 5 levels: no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems). We also considered two additional dimensions of self-assessment of health and well-being of ‘quality of life’ (with 5 levels, strongly disagree, disagree, neither agree nor disagree, agree, strongly agree) and ‘health condition’ (with 5 levels, very good, good, reasonable, bad, very bad). Regarding the description of lifestyles, diet was categorized per food groups per day and per week (following 5 levels in the Likert scale).

Qualitative research advances the possibilities of a deeper understanding of people’s perceptions and expectations and exploring unique topics within the research aims. For that purpose, we conducted the open-ended question in an in-depth interview: “ What would you change in your neighbourhood to have a healthier life? ”. To reduce eventual desirability bias, participants were ensured prior the eVida questionnaire that were no right or wrong responses and a privacy environment was ensured during the interview; the eVida and interview took in between 45 to 60 min.

Through eVida, information was collected on a random sample of 270 individuals living in rural neighbourhoods from the Sicó-network, considering the dimension and location of the neighbourhood (small villages, parish council and municipalities), constituting a sample with a margin of error of 5.75% and confidence level of 95%. The sample size for the interviews was determined by applying the saturation point criteria, and was stopped after 107 testimonials were collected. This study design was considered the most appropriate way to describe individuals’ lifestyles and communities’ environments. The collection of QUAL+quan data was performed by researchers with background on life sciences, medical and health sciences, and social sciences; the CBPR approach from the very early stages revealed to be determinant for the research methodology and outcomes. Furthermore, the first day of intervention was followed by a preliminary assessment and discussion by the advanced training students (and young professionals) and the team, in order to identify personal bias, optimize the use of eVida and the interview, and minimize any other form of unintended coercion with participants. Data collection was conducted between September 4 and 23, 2019.

Ethical considerations

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Centre Regional Health Administration of Portugal: Reference 91/2019. Participants were required to be 18 years or older and were asked to sign a written informed consent before initiating the community intervention. At the end, participants received a bag with the individualised report and the short cartoon-like active healthy lifestyles messages, about diet, physical activity, social cohesion, and mental health and well-being.

Data analysis

Testimonies were documented in writing, and then transcribed and translated to English. Each participant was linked the age, sex and municipality council in order to present direct quotations (e.g., Female, 68, Small Village, Pombalinho 610). The first four authors performed an independent analysis in all testimonies developing a parallel codification on drivers of health and well-being at community level in the rural neighbourhoods. After several collective discussions rounds (over a period of 3 months), seven consensual dimensions were identified a priori: economic development, built environment, social network, health care, demography, active lifestyles and mobility. The a priori themes were used to code the qualitative data in which subtopics were built upon [ 29 ].

All testimonies were imported to MAXQDA Analytics Pro 2020 version 20.0.0 (Berlin, Germany: VERBI Software GmbH) for coding and analysis. The coding was done in three stages. In the first stage, the testimonies were coded based on the selected dimensions. In a second stage of coding, the resulting identification of sub-topics for each of the 7 dimensions based on mention frequency, and the identification of predominant topics, in both individual accounts and different neighbourhoods, was carried out independently across researchers. Any new codes were consensually debated during regular team meetings. In the third stage, all testimonies were coded once more by applying the final coding scheme. All coded testimonies were evaluated for emerging topics. We used several strategies to ensure quality in data coding. The composition of coding pairs was changed after 10 to 15 testimonies to reduce possible systematic bias. Using this approach, we were able to examine the in situ community needs in the 15 rural neighbourhoods. We also documented the clear individual positive perceptions of living in rural neighbourhoods: i) in terms of healthy living and well-being; ii) the different ways of describing and explaining lifestyles and daily habits; iii) the multiples ways of living and be engaged with community environment; iv) access to health care and health services.

Authors involved in the analyses maintained the explanatory map of the CBPR process from the research goals to data collection and analysis. The number and the frequency of subjects mentioned by participants in different topics support the reliability and credibility of our findings. We also used the lexical search on the MAXQDA program for key codes, to identify the frequency and number of mentions for consistency in participants’ responses.

To supplement the qualitative analysis, binomial logistic regression models were applied: BMI (classified in two categories: 1. overweight and obesity and 2. normal and low weight), waist circumference (classified in two categories: 1. and 2.), self-assessed health status (classified in two categories: 1. good and very good and 2. less than good), were assessed as dependent variables and sex, age (continuous), place of residence (classified in the three classes: 1. small villages, 2. parish councils and 3. municipalities), as independent.

Demographic characteristics

Two hundred seventy people participated (84 in small villages, 112 in parish councils and 74 in municipalities). Women made up a larger proportion of the participants (63%) in the three levels (Table 1 ). The median age was 69 years (1st quartile: 58 years; 3rd quartile: 77 years), with 78% of the participants above 55 years of age. Most of the participants were retired (64%), with a higher proportion (77%) in small villages. The level of education varied along the neighbourhoods, with a small proportion (9%) having receiving higher education (4 and 3% in small villages and parish councils, and 24% in municipalities); the largest share of participants completed the first two grades of basic education (69%), and 14% did not receiving primary education (29, 9 and 7% in small villages, parish councils and municipalities, respectively).

Individual health functionality

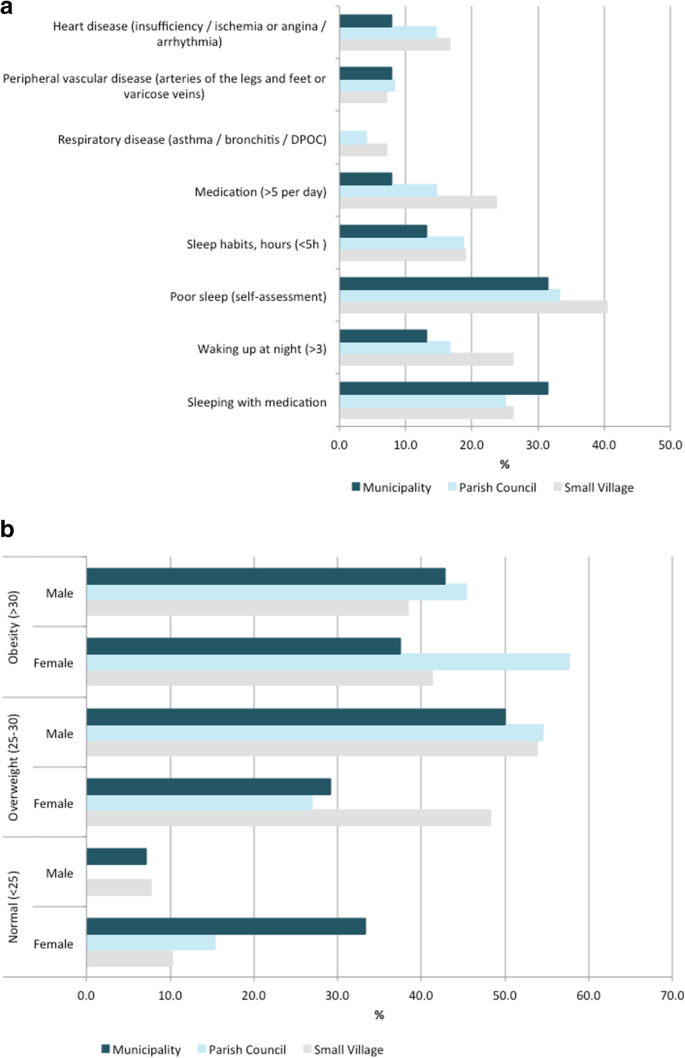

The proportion of participants with normal BMI was substantially lower above 55 years of age, with a higher proportion of women presenting normal BMI than men for the participants aged 55 to 74 years (Additional file 1 : Table S1). The proportion of participants with obesity was slightly higher in women aged 55 to 74 years and lower in the other range of ages (< 54 years, > 75 years). In terms of obesity data by rural neighbourhood, the proportion of participants with obesity was lower in municipalities (32%) than in small villages (38%) and parish councils (45%). For the participants aged 55 to 74 years (Fig. 3 a), excess weight was lower in women in all types of neighbourhoods (48 and 54% in small village; 27 and 55% in parish councils; 29 and 50% in municipalities; respectively); obesity was higher in men in municipalities (43 and 38%, respectively). Overall, men had a 75% higher probability of being overweight than women ( p -value: 0.0954), while waist circumference measurements reflected obesity over age, being consistently higher in participants > 75 years of age; the risk of having high waist circumference was 2.45 (IC: 1.1; 5.7) times higher in individuals living in small villages than in municipalities.

Evidence-based data by rural neighbourhood for participants aged 55 to 74 years

NCD risks associated to chronic diseases were reported by 25% of the participants aged 55 to 74 years (Fig. 3 b) including: (i) heart disease (heart failure, ischemia or angina, arrhythmia) was declared by 13% (17% in small villages, 15% in parish councils and 8% in municipalities); (ii) peripheral vascular disease (problems in arteries of the legs and feet, or varicose veins) was mentioned by 8% (7% in small villages, 8% in parish councils and 8% in municipalities); and (iii) respiratory disease (asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) was declared by 4% (7% in small villages and 4% in parish councils) (the information for all participants is presented in supplementary Table S1 ). The lowest prevalence of medication was documented in parish councils (33%) and municipalities (32%) (Additional file 1 : Table S1); overall, a substantial proportion of the participants (59%) reported were taking 2–5 medications a day, and a lower proportion (16%) reported taking > 5 medications a day.

Sleeping habits ranged from ≥7 h for 38% of the individuals and less than 5 hours for 17% of the individuals, with a clear trend of more sleeping hours in individuals living in municipalities (Additional file 1 : Table S1). Sleep without interruption was reported by 48% of the individuals, with higher prevalence (55%) in individuals living in municipalities. Consistently with sleeping hours, 35% of the individuals considered having poor sleep quality (41, 33 and 32%, in small villages, parish councils and municipalities, respectively; supplementary Table S1 ).

Self-rated health condition ranged from good (47%) to reasonable (42%), with little differences in neighbourhoods. About 5% of participants referred having very good health, consistently in all neighbourhoods, contrasting with the 5% of participants that mentioned having bad health, with lower incidence in municipalities (3%). Severe or extreme pain was reported by 6 and 1% of the individuals, respectively, with higher incidence from participants living in small villages. In terms of self-rated well-being, a large proportion of participants (74%) reported having a good quality of life, with 25% of the individuals attributing the highest score (18% living in small villages, 30% in parish council and 26% in municipalities). Across data, participants with higher waist circumference had a 2.21 (IC: 1.19; 4.27) higher probability of presenting a poor self-evaluation of their health status.

Unhealthy lifestyles according to rural neighbourhood type

The description of lifestyles in the 15 rural neighbourhoods is shown in Table 2 . A large proportion of participants (81%) reported eating fruit and vegetables 0–1 times per day. Only 1% of the participants mentioned eating fruit and vegetables fewer than once. A substantial proportion of individuals reported eating fish, meat and eggs (87%) 0–1 times per week in all neighbourhoods; also, a considerable share of individuals reported eating bread, pasta or cereal (82%) 0–1 per day, ranging from 78% in parish councils to 89% in small villages. Many participants reported drinking milk (66%) 0–1 per day, ranging from 50% of individuals living in municipalities to 60% of respondents from small villages; 6 and 9% mentioned drinking milk once a week or never, respectively, with little differences in all neighbourhood types. The majority of the population (69%) referred eating fried and salty foods once a week or less, in all neighbourhoods. Some participants (59%) mentioned eating sweets once a week or never, and 7% reported eating more than once a day (2% in small villages, 11% in parish council and 8% in municipalities). Regarding active lifestyles, a large proportion of participants (67%) reported having daily active routines. A lower proportion of participants (21%) reported regular vigorous physical activity, ranging from 11% doing gymnastics (e.g., fitness, Pilates, yoga), 4% water-based exercise (e.g., swimming or water aerobics), 2% bicycling, 1% running and 3% other sports. In general, those living in the municipalities assess better quality of life (following EQ-5D-5L questionnaire); regarding the self-assessment of health and well-being, the inferior levels were observed in small villages.

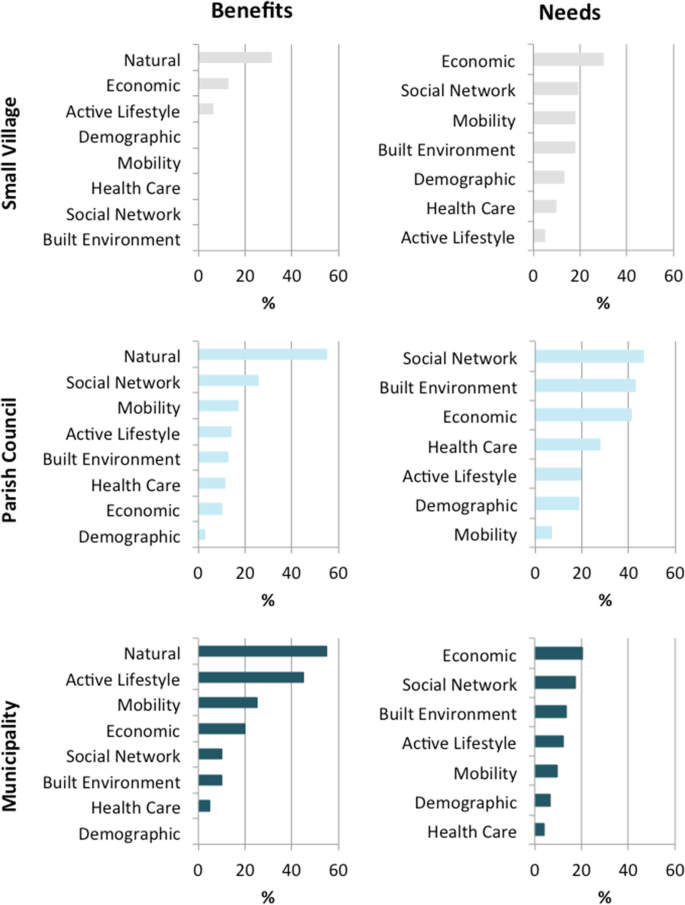

Characterization of community environment

Individual reflections pinpointed seven dimensions as the main drivers to pursue health and well-being in rural neighbourhoods. These include: economic development, built (and natural) environment, social network, health care, demography, active lifestyles and mobility (Fig. 4 ; supplementary Table S 2 ). Such reflections envision people-centred expectations and a deeper understanding of valuable surrounding environments connected to well-being, which contribute to unforeseen wider ‘needs’ and ‘benefits’ of rural areas.

Individual’s reflections about community circumstances influencing health and well-being in their rural neighbourhood

One third of the participants (86) stressed economic development as the main community need –financial, technological and digitalisation investment, high-value-added industry, industrial infrastructures, digitalisation for remote working–, with particular focus on economic innovation and diversification to encourage the establishment of young people in rural areas. Regional policies to improve investment and attractiveness of high-skilled young workers were mentioned by 12 participants.

Built environment, goods and services, underlined by 73 participants, emphasize the need for maintenance and conservation of (i) infrastructures for social interaction, ranging from cultural activities (24), green-blue areas for practicing physical activity and exercise, e.g., green public spaces, camping areas, river beaches, playing areas for children (18), to connected green-blue infrastructures for enjoying nature (14); (ii) infrastructures for promoting the inclusive walkability, namely for youth and elderly people with morbidities, such as smooth and safe walking paths and resting places (10) or sound barriers (2); and (iii) the patrimonial rehabilitation for tourism and habitation (3). Among the services needed, cafes, grocery stores or restaurants, bank, book stores and shopping facilities were mentioned. However, built environment reflected asymmetries in the neighbourhoods; some participants (7) underlined the accessibility to cafes, supermarkets and restaurants in their respective neighbourhoods as an additional benefit of living in rural areas, while others (11) mentioned safe streets, infrastructures for practicing exercise, e.g., gymnasium, swimming pool, tennis court and walking routes, and cultural activities, e.g., folk activities, folk music, cinema and theatre.

Social relationships and networks in neighbourhoods, mentioned by 81 participants, included local community-based initiatives and means of communication to reinforce social connections and dynamics. Asymmetrically, other participants (20) reinforcing local networks and dynamics as a benefit of living in their neighbourhoods, exemplifying with the active participation in collective grape/olive picking, or cultural and recreation activities.

Health care, mentioned by 42 participants, was mostly associated to elderly dependency and included the need for better and long-term health care services (39), support in transport to health care services (1) and pharmacies (2). Asymmetrically, the suitable health care support and services, primary health care services and pharmacies, emphasized by 9 participants, reflected the beneficial aspects mentioned in some neighbourhoods. Adult social care support, particularly day centres and nursing homes, underlined by 21 participants, including childcare and family care were also among the needs reported in rural neighbourhoods.

Demographic factors, mentioned by 37 participants, focused particularly on population ageing and the need of (young) people (30) as social pressure to improve education and (re)open schools (3) and kindergartens (3). The local education, stressed by 2 participants, was reported as a main benefit in their own neighbourhood, to promote well-being.

Active lifestyles, emphasized by 35 participants, include the need for (i) lifelong learning opportunities and digital inclusion, e.g., internet, information and communication technologies (ICTs) (17 participants); (ii) access to places for practicing physical activity and exercise, e.g., soccer, yoga, Pilates, fitness, pool, and walking (10 participants); and (iii) cultural activities, e.g., dance, music, cinema (8 participants). Mobility, mentioned by 30 participants, included the need of accessible public transport (25) and safe accessible walking routes (5). Asymetrycally, several participants (16) underlined the functionality in mobility –public transports systems– and accessibility and linkages (highways) to villages and cities nearby as a main benefit of their neighbourhood.

Natural resources and natural environment were in the centre of health and well-being in rural neighbourhoods. The majority of the individuals (237) mentioned to like living in their neighbourhood and 55 participants featured the natural environment was as the main community benefit to improve quality of life, describing their neighbourhood as calm, beautiful, healthy and safe. The prioritisation on quality of life include (i) daily routines linked to land use, e.g., gardening, agriculture, silvo-pastoral practices; (ii) biodiversity; (iii) connectivity with nature, e.g., swimming and fishing in rivers, walking in green spaces, woodlands and mountains; and (iv) environmental quality, e.g., lower exposure to air / noise pollution. More than two thirds of the participants (192) mentioned they would not live elsewhere if they could and one third (92) revealed they would not change anything in their neighbourhood. Overall, 216 participants underlined that their own neighbourhood is a good place to live. Specific testimonies on these issues are sampled below (Table 3 ).

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first qualitatively driven mixed-method approach to assess whether unhealthy lifestyles and surrounding environments are reflected into metabolic risks and health capability at individual and community-level in rural neighbourhoods.

In terms of the main findings, excess weight and obesity are more prevalent in men between 55 to 74 years and in individuals younger than 54 years, respectively, while in women obesity predominates between 55 to 74 years while excess weight is more predominant in individuals younger than 54. Considering the overall population, NCD risk linked to BMI was superior in small villages than in municipalities. NCD risk associated to unhealthy lifestyles was less evident for diet and sleep habits than for (lack of) physical activity. Diet habits reported by the participants strongly evidenced the adherence to a Mediterranean dietary pattern, which is linked to healthy lifestyles due to its protective effect against several metabolic risks and NCD, namely type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease (CVD), obesity, cancers and total mortality [ 30 ]. Diet and metabolic risks were described as the second and third leading risks factors of early mortality in a recent survey for Portugal [ 31 ]; but it did not address rural and urban neighbourhoods separately. In Europe, DALYs and risks evidences from NCD also often expose dietary and metabolic risk factors [ 12 ], but again little is known about the relationship between NCD burden and community environment. Healthy diet habits reported in our study suggest that the accessibility to healthy food in own gardens and farms as well as in local markets enable the ability to make healthy choices. Indeed, several participants from small villages mentioned they produce their own food (e.g., vegetables and legumes, fruits and nuts, cereals, meat, eggs, cheese, olive oil), whereas participants from parish councils and municipalities mentioned obtaining local products in grocery stores or the local weekly markets.

Low level of regular physical activity and exercise was admitted by most of the participants in all neighbourhoods. Physical inactivity has been recognized as the fourth leading risk factor for global mortality [ 32 ] and the most pressing public health burden of the current century [ 33 ]. Portugal is the second country in the euro-area with higher physical inactivity in people over 60 years of age and among the countries with higher prevalence of multi-morbidity in people between 60 and 65 years [ 34 ]. Two previous reviews have highlighted that physical inactivity may be explained by pursuing health focused on individual-level determinants, such as self-motivation or literacy, whereas surrounding environment also determines the ability to prevent metabolic risks and choose healthy lifestyles [ 35 , 36 ].

The qualitative research revealed people-centred health and well-being expectations, allowing us to identify seven main dimensions in community circumstances: economic development, built and natural environment, social network, health care, demography, active lifestyles, and mobility, affecting the options to improve or pursue healthier lifestyles, with asymmetries among the neighbourhoods. In fact, participants reframed the narratives, “ I like where I am! ”, underlining the benefits of living in their own neighbourhood; while two thirds of the participants revealed they wouldn’t live elsewhere if they could. Several studies have previously researched the effect of place of residence in terms of availability and accessibility in order to improve health [ 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 ].

Economic development and built environment emerged as the main community needs, namely via financial, technological, and digitalisation investment to attract high-skilled young workers to rural areas, and social interaction and lifelong learning activities, respectively, given that built and natural environment are the setting for the development of human activities [ 41 ]. Natural resources and natural environment were stressed as the main value of rural well-being. However some participants mentioned missing planned and oriented structures to connect with nature, such as functional green-blue areas to exercise / be physically active, or socialize, which can be also an opportunity to come with co-benefits for biodiversity and nature protection and conservation [ 42 ]. Some rural neighbourhoods have been associated with less vigorous physical activity due to socio-economic disadvantages, including less availability to, and use of, facilities for sports and recreational activities [ 43 , 44 ]. By contrast rural neighbourhoods with available green spaces and higher accessibility or walkability tend to contribute to metabolic risk prevention, namely for T2DM [ 36 ]. However the (perceived) accessibility of walkability in rural and urban neighbourhoods may vary in different parts of the world. The low use of the bicycle as a mode of transportation reported in our study can be associated with the absence of specific infrastructures for cycling safety (e.g. on-road bike routes, on-road marked bike lanes), mentioned by some participants, but could also be due to the (high) average participant age. Notably, previous qualitative studies have stressed the positive association between adapted designing interventions in the environment for promoting active lifestyles and PA in rural adults, with gains to social cohesion and individual health conditions [ 43 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 ].

Rural neighbourhoods in Portugal are characterized by a higher ageing index, lower geographical access to health care, lower average income and declining population [ 48 , 49 ], but there still is an underestimation of health capability versus disease burden and environment. DALYs have been relevant in terms of the costs to direct health care, namely to the public sector [ 50 ]; however, the translation of such knowledge rarely results into positive contributions and policies to rural neighbourhoods [ 20 ]. Some key subjects need to be considered in further research, including whether the 1) prevalence of women is associated with the demographic uneven structure of the elderly populations, or with women involvement in community, such as agriculture and social activities; 2) increase in evidence-based health and well-being is accompanied by an improvement in community environment, and whether common causes of choosing to live in rural neighbourhoods, such as greater food security, safety, connection with nature, quality of environment, improve metabolic risks and NCD over time [ 8 ] and thus health capability. The ambition of creating accessibility of ‘health-promoting environments’ in green and public areas, to reduce the NCD is well reflected on goal 11.7 of the World Health Organization’s sustainable development goals (2016) [ 51 ]. Populations in rural areas have access to, among other things, healthy food and healthy environmental resources; however rural structural capacities are often under-represented in developing and implementing socioeconomic policies.

In fact, rural marginalization affects health and social justice [ 52 ] and impacts metabolic risks and co-morbidities in populations [ 5 ]. BMI and waist measures observed in this study combined with the participatory approach about lifestyles and community environment, configure an opportunity to act differently in terms of improving health capability in Portuguese rural neighbourhoods, and these findings could thus serve as a driving force for encouraging healthy changes at both individual and community levels [ 18 ].

There are some limitations to this study. The approach was conducted in a single region of the country; thus, results cannot be generalized to other rural neighbourhoods or remote regions. Moreover, data was collected during standard working hours of the week, which might have influenced the sample, including ageing index and the prevalence of women participating. However, we did cover a representative sample of rural populations in Portugal. The eVida has been designed to be user friendly and of almost immediate understanding to participants (10 to 20 min to complete) [ 27 ]. Although the eVida has been re-designed to record information about external environment factors, testimonies were mostly documented in writing and then transcribed. Future research in health innovation devices should also focus on developing programs that can incorporate context-based information, and with it, a better understanding of how ability to pursue health come as a whole from internal and external factors. The use of technology-based devices is increasingly modifying resources and support of health care services and health monitoring, traditionally carried out by health providers in medical facilities. Such innovative devices and adapted strategies have been suggested to encourage active self-management and to ‘empower’ behaviours, and as a way to acquire reliable health-related knowledge to make self-balance decisions [ 28 ].

The qualitative driven mixed-method design allowed us to gather data concerning unhealthy lifestyles of individuals but also to collect in-depth information about community environments that facilitate / weaken individual health and well-being, and their ability to make healthy choices (data saturation was achieved by characterizing broader determinants of health and well-being in neighbourhoods). We believe that the mixed-method described is one way to combine multiple components acting independently and inter-dependently, in order to better understand health capability at both the individual and community levels. The main strengths of the study include the co-designing community program involving the local representatives of the Sicó-network and advanced training students (and young professionals), working together with a trans-disciplinary research team. With the advantages of CBPR, the involvement of community in the early stage of the study provided the opportunity for discussing and adapting the health-related messages for a population with a high ageing index and limited literacy living in the Sicó-network (Portuguese National Statistics, 2019). Such involvement of community and its degrees of negotiation, and flexibility, enabled researchers to uncover gaps regarding (natural) environment contextual-dependent circumstances influencing the ability of individuals to pursue health in their own neighbourhoods.

Our findings are relevant for raising healthy lifestyles awareness and health seeking-skills to improve the self-ability to make balanced decisions, for implementing technology-based devices combined with participatory dynamics, as well as for encouraging the active engagement of local representative planners (governments and other stakeholders) in research to enhance the capacity building and thus the capability for improving heath in rural areas. There are specific contexts of marginalized rural areas for whom the (itinerant) health promotion services and support seem to be an important component of cohesion and equity [ 53 , 54 , 55 ]. The impact of design and intervention with community representatives is planned and further reflexion on follow-up of the healthy lifestyle assessment in rural (and urban) neighbourhoods is required, which is feasible using the tools in a reference site of the collaborative network European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing (EIP on AHA) [ 28 , 56 , 57 , 58 ].

Revisiting our initial research aim to assess whether unhealthy lifestyles and environment in rural neighbourhoods are reflected into metabolic risks and health capability, we observed that NCD risk in overweight individuals (aged 55 to 74 years) was higher in men in all neighbourhoods; and metabolic risks were more associated to BMI and physical activity than diet (or sleeping habits). The qualitative research allowed us to uncovering seven environmental circumstances reflecting health needs, health expectations and health capability at community-level: economic development, built (and natural) environment, social network, health care, demography, active lifestyles, and mobility, which also underline the asymmetries among neighbourhoods. Notably, participants often reframed their narratives to express the benefits of living in rural areas. Natural resources and environment were pinpointed as the main value of rural well-being, with a particular focus on land use, biodiversity and connectivity with nature, as well as environmental quality. Our CBPR approach contributed for the active involvement of the local representatives and to adapt the health-related messages for older adults with limited literacy. The co-benefits from this co-designing community program and cross-disciplinary research provide further evidence to support people-centred approaches for pushing health and well-being at a broader social, health care and natural environment agenda in rural neighbourhoods.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Abbreviations

Active and Healthy Ageing

Body Mass Index

Cardiovascular Disease

Community-Based Participatory Research

Disability-Adjusted-Life-Years

European Innovation Partnership

European Institute of Innovation and Technology for Health

Healthy Lifestyle Innovation Quarters for Cities and Citizens

Information and Communication Technologies

Institute for Health, Metrics and Evaluation

mobile Healthy Living Room

Non-Communicable Diseases

Systolic blood pressure

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

World Health Organisation

GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1789–858.

Article Google Scholar

Cordain L, Eaton SB, Sebastian A, Mann N, Lindeberg S, Watkins BA, et al. Origins and evolution of the Western diet: health implications for the 21st century. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81(2):341–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn.81.2.341 .

Roth GA, Johnson C, Abajobir A, Abd-Allah F, Abera SF, Abyu G, et al. Global, regional, and National Burden of cardiovascular diseases for 10 causes, 1990 to 2015. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(1):1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.052 .

NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128·9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–42.

Non-Communicable Diseases Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Rising rural body-mass index is the main driver of the global obesity epidemic in adults. Nature. 2019;569:260–4.

Reid S. The rural determinants of health: using critical realism as a theoretical framework. Rural Remote Health. 2019;19:5184.

PubMed Google Scholar

Barton H, Tsourou C. Healthy urban planning in practice: experience of European cities. Report of the WHO City Action Group on Healthy Urban Planning. In: A WHO guide to planning for people: WHO Regional Office for Europe. Copenhagen, Denmark; 2000.

Samoggia A, Bertazzoli A, Ruggeri A. European rural development policy approaching health issues: an exploration of programming schemes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2973. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16162973 .

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Santana P. Urbanização e saúde. Janus. 2009;2009:1–7.

Google Scholar

Santana P, Nogueira H, Costa C, Santos R. Identificação das vulnerabilidades do ambiente físico e social na construção da Cidade Saudável. Coimbra: A Cidade e a Saúde; 2007. p. 165–81.

Corburn J. Urban place and health equity: critical issues and practices. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14020117 .

WHO. Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases in the WHO European Region 2016-2025. 2016.

Creswell JW, Hirose M. Mixed methods and survey research in family medicine and community health. Fam Med Community Health. 2019;7:86.

Hilger-Kolb J, Ganter C, Albrecht M, Bosle C, Fischer JE, Schilling L, et al. Identification of starting points to promote health and wellbeing at the community level - a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6425-x .

Nussbaum M. Nature, function, and capability: aristotle on political distribution. In: Oxford studies in ancient philosophy: Supplementary volume: Oxford University Press. Oxford, United Kingdom; 1988. p. 145–84.

Nussbaum M. Creating capabilities: the human development approach. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2011. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061200 .

Book Google Scholar

Ruger JP. Health, capability, and justice: toward a new paradigm of health ethics, policy and law. Cornell J Law Public Policy. 2006;15(2):403–82.

Ruger JP. Health capability: conceptualization and operationalization. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):41–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2008.143651 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ruger JP. Ethics of the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2004;364(9439):1092–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17067-0 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

OECD/European Union. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018: State of Health in the EU Cycle. Brussels: OECD Publishing; 2018.

WHO. Global Status Report on Noncommunicable Diseases 2014. 2014.

WHO. Noncommunicable Diseases Progress Monitor 2020. 2020.

Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, Becker AB. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19(1):173–202. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Mota-Pinto A, Rodrigues V, Botelho A, Veríssimo MT, Morais A, Alves C, et al. A socio-demographic study of aging in the Portuguese population: the EPEPP study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;52(3):304–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2010.04.019 .

Morse JM, Niehaus L. Mixed method design: principles and procedures. New York: Routledge; 2009.

Barton H, Grant M. A health map for the local human habitat. J R Soc Promot Heal. 2006;126(6):252–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/1466424006070466 .

Reis F, Sá-Moura B, Guardado D, Couceiro P, Catarino L, Mota-Pinto A, et al. Development of a healthy lifestyle assessment toolkit for the general public. Front Med. 2019;6:134.

Malva JO, Amado A, Rodrigues A, Mota-Pinto A, Cardoso AF, Teixeira AM, et al. The quadruple Helix-based innovation model of reference sites for active and healthy ageing in Europe: the ageing@Coimbra case study. Front Med. 2018;5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00132 .

Carroll C, Booth A, Cooper K. A worked example of “best fit” framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemopreventive agents. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-29 .

Miller V, Webb P, Micha R, Mozaffarian D. Defining diet quality: a synthesis of dietary quality metrics and their validity for the double burden of malnutrition. Lancet Planetary Health. 2020;4(8):e352–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30162-5 .

General Directorate of Health and Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Portugal: The Nation’s Health 1990–2016: An overview of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016 Results. Direção-Geral da Saúde, Lisboa, Portugal. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Seattle, USA; 2018.

WHO. Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health. Geneva: WHO; 2010.

Al Tunaiji H, Davis JC, Mansournia MA, Khan KM. Population attributable fraction of leading non-communicable cardiovascular diseases due to leisure-time physical inactivity: a systematic review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2019;5(1):e000512. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsem-2019-000512 .

WHO. World Report on Ageing and Health. 2015.

Van Holle V, Deforche B, Van Cauwenberg J, Goubert L, Maes L, Van de Weghe N, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and different domains of physical activity in European adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):807. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-807 .

DenBraver NR, Lakerveld J, Rutters F, Schoonmade LJ, Brug J, Beulens JWJ. Built environmental characteristics and diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0997-z .

Article CAS Google Scholar

Diez Roux AV. Investigating neighborhood and area effects on health. Am J Public Health. 2001;91(11):1783–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.91.11.1783 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how can we conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55(1):125–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00214-3 .

Cummins S, Stafford M, Macintyre S, Marmot M, Ellaway A. Neighbourhood environment and its association with self rated health: evidence from Scotland and England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005;59(3):207–13. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.016147 .

Barton H, Thompson S, Burgess S, Grant M. The Routledge handbook of planning for health and well-being. Shaping a sustainable and healthy future. Devon: Routledge; 2015.

Bird EL, Ige JO, Pilkington P, Pinto A, Petrokofsky C, Burgess-Allen J. Built and natural environment planning principles for promoting health: an umbrella review. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):930. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5870-2 .

Ten Brink P, Mutafoglu K, Schweitzer J-P, Kettunen M, Twigger-Ross C, Kuipers Y, et al. The health and social benefits of Nature and biodiversity protection-executive summary. London/Brussels: Institute for European Environmental Policy; 2016.

Kegler MC, Swan DW, Alcantara I, Feldman L, Glanz K. The influence of rural home and neighborhood environments on healthy eating, physical activity, and weight. Prev Sci. 2014;15(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-012-0349-3 .

Chrisman M, Nothwehr F, Yang G, Oleson J. Environmental influences on physical activity in rural Midwestern adults: a qualitative approach. Health Promot Pract. 2015;16(1):142–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839914524958 .

Barnidge EK, Baker EA, Estlund A, Motton F, Hipp PR, Brownson RC. A participatory regional partnership approach to promote nutrition and physical activity through environmental and policy change in rural Missouri. Prev Chronic Dis. 2015;12:140593. https://doi.org/10.5888/pcd12.140593 .

Hege A, Christiana RW, Battista R, Parkhurst H. Active living in rural Appalachia: using the rural active living assessment (RALA) tools to explore environmental barriers. Prev Med Rep. 2017;8:261–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.11.007 .

Luo Y, Zhang L, Pan X. Neighborhood environments and cognitive decline among middle-aged and older people in China. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2019;74(7):e60–71. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbz016 .

de Almeida SJ, Augusto GF, Fronteira I, Hernandez-Quevedo C. Portugal: health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2017;19:1–184.

Soares da Silva D, Figueiredo E, Eusébio C, Carneiro MJ. The countryside is worth a thousand words – Portuguese representations on rural areas. J Rural Stud. 2016;44:77–88.

European Commission and Economic Policy Committee (Ageing Working Group). The 2018 Ageing report: economic and budgetary projections for the EU member states (2016-2070). European Commission, Brussels; 2018.

WHO. Sustainable Development Goal 11. 2016.

Braveman PA, Kumanyika S, Fielding J, LaVeist T, Borrell LN, Manderscheid R, et al. Health disparities and health equity: The issue is justice. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(SUPPL. 1):S149.

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Walsh K, O’Shea E. Responding to rural social care needs: older people empowering themselves, others and their community. Health Place. 2008;14(4):795–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.12.006 .

Nimegeer A, Farmer J. Prioritising rural authenticity: community members’ use of discourse in rural healthcare participation and why it matters. J Rural Stud. 2016;43:94–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.11.006 .

Winterton R, Warburton J, Keating N, Petersen M, Berg T, Wilson J. Understanding the influence of community characteristics on wellness for rural older adults: a meta-synthesis. J Rural Stud. 2016;45:320–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2015.12.010 .

Sá-Moura B, Couceiro P, Catarino L, Guardado D, Brito M, Gomes B, et al. Bridging health and social care with the citizens – the case of EIT health project “Healiqs4cities” and “Praça Vida+”, in Portugal. Care Wkly. 2018;2:21–4.

Bousquet J, Malva J, Nogues M, Mañas LR, Vellas B, Farrell J, et al. Operational definition of active and healthy aging (AHA): the European innovation partnership (EIP) on AHA reference site questionnaire: Montpellier October 20–21, 2014, Lisbon July 2, 2015. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2015;16(12):1020–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.09.004 .

Bousquet J, Illario M, Farrell J, Batey N, Carriazo AM, Malva J, et al. The reference site collaborative network of the European innovation partnership on active and healthy ageing. Transl Med. 2019;19:66–81 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31360670 . Accessed 28 May 2021.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Advanced training students and young professionals that helped in the implementation of the community program in the 15 neighbourhoods of the Sicó-network: Adriana Caldo, Ana Pedrosa, André Caseiro, Beatriz Vaz, Carlos Farinha, Catarina Santos, Fernanda Silva, Inês Cipriano, Larissa Theil, Lilian Merini, Márcio Cascante, Rafael Rodrigues and Rafael Neves; the members of the Association Terras de Sicó (Lands of Sicó) and all the local stakeholders that helped implementing and disseminating our activities. HeaLIQs4Cities Consortium involved, which is composed by António Cunha, André Pardal, Eugénia Peixoto, Diana Guardado from the Instituto Pedro Nunes (IPN, Coimbra, Portugal); Marieke Zwaving from Rijksuniversiteit Groningen (The Netherlands); Eduardo Briones Pérez De La Blanca from Servicio Andaluz de Salud (SAS, Seville, Spain); Roel A. van der Heijden, Ruth Koops van ‘t Jagt and Daan Bultje from University Medical Center Groningen (UMCG, The Netherlands); João Malva, Flávio Reis, Luís Rama, Manuel Veríssimo, Ana Teixeira, Margarida Lima, Lèlita Santos, Filipe Palavra, Pedro Ferreira, Anabela Mota Pinto, Paula Santana, Ricardo Almendra, Adriana Loureiro, Inês Viana, Marta Quatorze, Anabela Marisa Azul, João Ramalho-Santos from the University of Coimbra (Portugal); Catharina Thiel Sandholdt and Maria Kristiansen from University of Copenhagen (UCPH, Denmark). We thank to the Reviewers the comments, which contributed for improving the manuscript. This research work was also developed under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), through the COMPETE 2020 – Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation and Portuguese national funds via FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, the project UID/NEU/04539/2019, the Centro 2020 Regional Operational Programme: project CENTRO-01-0145-FEDER-000012-HealthyAging2020, the FOIE GRAS project, funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020, Research and Innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant Agreement No. 722619, and the Decree Law 57/2016 (amended by Law 57/2017).

This research was developed in the scope of the European project Healthy Lifestyle Innovation Quarters for Cities and Citizens (HeaLIQs4Cities), funded by the European Institute of Innovation and Technology for Health (EIT Health) [Project Number 18036]. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, analysing or interpreting data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology (CNC), University of Coimbra, 3004-504, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul, Rui Tavares & João Ramalho-Santos

Center for Innovative Biomedicine and Biotechnology (CIBB), University of Coimbra, 3030-789, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul, Flávio Reis, Rui Tavares, João Oliveira Malva & João Ramalho-Santos

University of Coimbra, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research (IIIUC), 3030-789, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul & Rui Tavares

Centre of Studies in Geography and Spatial Planning (CEGOT), Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Colégio de São Jerónimo, University of Coimbra, 3004-530, Coimbra, Portugal

Ricardo Almendra, Adriana Loureiro & Paula Santana

Department of Geography and Tourism, Faculty of Arts and Humanities, Colégio de São Jerónimo, University of Coimbra, 3004-530, Coimbra, Portugal

Ricardo Almendra & Paula Santana

Coimbra Institute for Clinical and Biomedical Research (iCBR), Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3030-789, Coimbra, Portugal

Marta Quatorze, Flávio Reis, Anabela Mota-Pinto & João Oliveira Malva

Institute of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, 3030-370, Coimbra, Portugal

Flávio Reis & João Oliveira Malva

Clinical Academic Center of Coimbra (CACC), 3030-370, Coimbra, Portugal

Flávio Reis

CIMAGO-Center for Research in the Environment, Genetics and Oncobiology, Faculty of Medicine, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Mota-Pinto

IPN-Laboratory of Automatics and Systems, Pedro Nunes Institute, 3030-199, Coimbra, Portugal

- António Cunha

Ageing@Coimbra, EIP on AHA Reference Site, Coimbra, Portugal

António Cunha & João Oliveira Malva

Faculty of Sport Sciences and Physical Education, University of Coimbra, 3040-256, Coimbra, Portugal

Department of Life Sciences (DCV), Faculty of Sciences and Technology, University of Coimbra, 3000-456, Coimbra, Portugal

João Ramalho-Santos

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- , André Pardal

- , Eugénia Peixoto

- , Diana Guardado

- , Marieke Zwaving

- , Eduardo Briones Pérez De La Blanca

- , Roel A. van der Heijden

- , Ruth Koops Van’t Jagt

- , Daan Bultje

- , João Malva

- , Flávio Reis

- , Luís Rama

- , Manuel Veríssimo

- , Ana Teixeira

- , Margarida Lima

- , Lèlita Santos

- , Filipe Palavra

- , Pedro Ferreira

- , Anabela Mota Pinto

- , Paula Santana

- , Ricardo Almendra

- , Adriana Loureiro

- , Inês Viana

- , Marta Quatorze

- , Anabela Marisa Azul

- , João Ramalho-Santos

- , Catharina Thiel Sandholdt

- & Maria Kristiansen

Contributions

AMA was involved in the conceptualization and design of the study, all stages of data collection, curation, and analysis and led on writing the paper: original draft. RA, MQ, AL, PS and JRS were involved in the conceptualization and design of the study, all stages of data collection, curation, and analysis and writing the paper. FR, AMP, AC, LR, JOM, were involved in the conceptualization and design, data collection and writing the paper. RT was involved in the visual content. AC, JOM and HeaLIQs4Cities Consortium were involved in the funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Anabela Marisa Azul or João Ramalho-Santos .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate, consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: table s1..

Evidence-based data by neighbourhoods’ type.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Characterization of the community environment needs by neighbourhoods’ type and self-assessment of neighbourhood’ satisfaction.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Azul, A.M., Almendra, R., Quatorze, M. et al. Unhealthy lifestyles, environment, well-being and health capability in rural neighbourhoods: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 21 , 1628 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11661-4

Download citation

Received : 11 November 2020

Accepted : 25 August 2021

Published : 06 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11661-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Non-communicable diseases

- Healthy lifestyles

- Health loss

- Health capability

- Qualitative driven mixed-methods

- Participatory community-based research

- Built environment

- Natural environment

- Rural areas

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Advantages And Disadvantages Of Healthy Lifestyle?

Welcome to an exciting discussion about the advantages and disadvantages of a healthy lifestyle! We all know that living a healthy life has numerous benefits, but have you ever stopped to consider the potential downsides? Don’t worry, we’ve got you covered. In this article, we’ll explore both the positives and negatives of adopting a healthy lifestyle, giving you a well-rounded perspective on this popular topic.

Let’s dive right in and explore the advantages first. When it comes to living a healthy lifestyle, the benefits are plentiful. From improved physical fitness to increased mental well-being, there’s no denying the positive impact it can have on your overall quality of life. Engaging in regular exercise not only helps you stay in shape, but it also boosts your energy levels and enhances your mood. Additionally, maintaining a nutritious diet can contribute to weight management, reduce the risk of chronic diseases, and promote better digestion. It’s no wonder that so many people are eager to embrace a healthier way of living.

However, like everything in life, there are also disadvantages to consider. One potential drawback is the level of commitment required. It’s no secret that adopting a healthy lifestyle requires discipline and dedication. From meal planning to regular exercise routines, it can be challenging to maintain the necessary habits amidst a busy schedule. Furthermore, the cost of healthy food options and fitness memberships may pose financial challenges for some individuals. It’s essential to weigh these factors alongside the advantages to determine if a healthy lifestyle is the right fit for you.

A healthy lifestyle offers numerous advantages for overall well-being. Regular exercise helps maintain a healthy weight, boosts mood, and reduces the risk of chronic diseases. A balanced diet rich in fruits, vegetables, and whole grains provides essential nutrients while lowering the risk of heart disease and obesity. Additionally, healthy habits can improve sleep quality and increase energy levels. However, it’s important to note that a healthy lifestyle might require time and effort, and some people may find it challenging to stick to new habits.

Advantages and Disadvantages of a Healthy Lifestyle

Living a healthy lifestyle has become increasingly popular in recent years. People are becoming more conscious of the impact their lifestyle choices have on their overall well-being. In this article, we will explore the advantages and disadvantages of adopting a healthy lifestyle. It is important to note that while there are numerous benefits to living a healthy lifestyle, there are also some potential drawbacks to consider. Let’s delve deeper into this topic and understand the various aspects related to a healthy lifestyle.

The Advantages of a Healthy Lifestyle

Living a healthy lifestyle offers numerous advantages that contribute to a person’s overall well-being. One of the main benefits is improved physical health. Engaging in regular exercise, eating a balanced diet, and getting enough sleep can help prevent various health conditions such as heart disease, obesity, and diabetes. By maintaining a healthy weight, individuals can reduce their risk of developing these chronic diseases.

Another advantage of a healthy lifestyle is increased energy levels. When we prioritize our health, we provide our bodies with the necessary nutrients and care to function optimally. This leads to higher energy levels, allowing us to be more productive in our daily lives. Additionally, a healthy lifestyle can improve mental health by reducing stress levels and boosting mood. Regular exercise releases endorphins, which are known as “feel-good” hormones, promoting a sense of well-being and happiness.

Physical Fitness and Overall Well-being

Physical fitness is an essential aspect of a healthy lifestyle and offers a range of benefits. Regular exercise not only helps maintain a healthy weight but also improves cardiovascular health. Engaging in activities such as running, swimming, or cycling can strengthen the heart and lungs, reducing the risk of heart disease. Exercise also promotes better sleep patterns, which are crucial for overall well-being.

Furthermore, a healthy lifestyle can enhance cognitive function. Studies have shown that exercise and a balanced diet can improve memory, focus, and concentration. By providing our brains with the necessary nutrients, we support optimal cognitive performance. Additionally, a healthy lifestyle can slow down the aging process, both internally and externally. Eating a diet rich in antioxidants and engaging in regular exercise can help reduce the signs of aging, keeping us looking and feeling younger.

The Disadvantages of a Healthy Lifestyle

While there are many advantages to living a healthy lifestyle, it is important to acknowledge that there can be some disadvantages as well. One potential drawback is the cost associated with healthy living. Organic or locally sourced food, gym memberships, and fitness equipment can be more expensive than their less healthy alternatives. This can make it challenging for individuals on a tight budget to prioritize their health.

Another disadvantage is the time commitment required for maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Regular exercise and meal preparation can be time-consuming, especially for those with busy schedules. Balancing work, family, and personal commitments while prioritizing health can be a juggling act. Additionally, social pressures and temptations can make it difficult to stick to a healthy lifestyle. Attending social gatherings or eating out with friends may present challenges in making healthy food choices.

Maintaining a Healthy Balance

It is crucial to strike a balance when adopting a healthy lifestyle to avoid potential disadvantages. Finding affordable and accessible ways to prioritize health, such as cooking meals at home and incorporating physical activity into daily routines, can help overcome financial and time-related challenges. It is also important to remember that occasional indulgences or deviations from a strict healthy routine are not inherently negative. Allowing flexibility in our lifestyle choices can contribute to long-term success and enjoyment of a healthy lifestyle.

In conclusion, a healthy lifestyle offers numerous advantages, including improved physical and mental health, increased energy levels, and better overall well-being. However, it is essential to consider potential drawbacks such as cost, time commitment, and social pressures. By finding a balance and making sustainable choices, individuals can reap the benefits of a healthy lifestyle while navigating the challenges that may arise. It is worth the effort to invest in our health and well-being, as the advantages outweigh the disadvantages in the long run.

Key Takeaways: Advantages and Disadvantages of a Healthy Lifestyle

- Advantages of a healthy lifestyle include increased energy levels and improved physical fitness.

- Following a healthy lifestyle can help reduce the risk of chronic diseases like heart disease and diabetes.

- Eating a balanced diet and exercising regularly are key components of a healthy lifestyle.

- Disadvantages of a healthy lifestyle may include the need for discipline and self-control.