Advertisement

The art of the short story, issue 79, spring 1981.

In March, 1959, Ernest Hemingway’s publisher Charles Scribner, Jr. suggested putting together a student’s edition of Hemingway short stories. He listed the twelve stories which were most in demand for anthologies, but thought that the collection could include Hemingway’s favorites, and that Hemingway could write a preface for classroom use. Hemingway responded favorably. He would write the preface in the form of a lecture on the art of the short story.

Hemingway worked on the preface at La Consula, the home of Bill and Annie Davis in Malaga. He was in Spain that summer to follow the mano a mano competition between the brother-in-law bullfighters, Dominguín and Ordóñez. Hemingway traveled with his friend, Antonio Ordóñez, and wrote about this rivalry in “The Dangerous Summer,” a three-part article which appeared in Life .

The first draft of the preface was written in May, and Hemingway completed the piece during the respite after Ordóñez was gored on May 30th. His wife, Mary, typed the draft, and, as she wrote in her book How It Was , she did not entirely approve of it. She wrote her husband a note suggesting rewrites and cuts to remove some of what she felt was its boastful, smug, and malicious tone. But Hemingway made only minor changes.

Hemingway sent the introduction to Charles Scribner and proposed changing the book to a collection for the general public. Scribner agreed to the change. However, he diplomatically suggested not printing the preface as it stood, but rather using only the relevant comments as introductory remarks to the individual stories. Scribner felt that the preface, written as a lecture for college students, would not be accepted by a reading audience which might well “misinterpret it as condescension.” [Scribner to E.H. June 24, 1959.]

The idea of the book was dropped.

Hemingway wrote the preface as if it were an extemporaneous oral presentation before a class on the methods of short story writing. It is similar to a transcript of an informal talk. Judging it against literary standards, or using it to assess Hemingway’s literary capabilities would elevate it beyond this level, and would be inappropriate. Both Hemingway’s wife and his publisher were against its publication, and in the end Hemingway agreed. It appears here because of its content. Hemingway relates the circumstances under which he wrote the short stories; he gives opinion on other writers, critics, and on his own works; he expresses views on the art of the short story.

The essay is published unedited except for some spelling corrections. A holograph manuscript, two type scripts and an addendum, written for other possible selections for the book are in the Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library.

Gertrude Stein who was sometimes very wise said to me on one of her wise days, “Remember, Hemingway, that remarks are not literature.” The following remarks are not intended to be nor do they pretend to be literature. They are meant to be instructive, irritating and informative. No writer should be asked to write solemnly about what he has written. Truthfully yes. Solemnly, no. Should we begin in the form of a lecture designed to counteract the many lectures you will have heard on the art of the short story?

Many people have a compulsion to write. There is no law against it and doing it makes them happy while they do it and presumably relieves them. Given editors who will remove the worst of their emissions, supply them with spelling and syntax and help them shape their thoughts and their beliefs, some compulsory writers attain a temporary fame. But when shit, or merde —a word which teacher will explain—is cut out of a book, the odor of it always remains perceptible to anyone with sufficient olfactory sensibility.

The compulsory writer would be advised not to attempt the short story. Should he make the attempt, he might well suffer the fate of the compulsive architect, which is as lonely an end as that of the compulsive bassoon player. Let us not waste our time considering the sad and lonely ends of these unfortunate creatures, gentlemen. Let us continue the exercise.

Are there any questions? Have you mastered the art of the short story? Have I been helpful? Or have I not made myself clear? I hope so.

Gentlemen, I will be frank with you. The masters of the short story come to no good end. You query this? You cite me Maugham? Longevity, gentlemen, is not an end. It is a prolongation. I cannot say fie upon it, since I have never fie-ed on anything yet. Shuck it off, Jack. Don’t fie on it.

Should we abandon rhetoric and realize at the same time that what is the most authentic hipster talk of today is the twenty-three skidoo of tomorrow? We should? What intelligent young people you are and what a privilege it is to be with you. Do I hear a request for authentic ballroom bananas? I do? Gentlemen, we have them for you in bunches.

Actually, as writers put it when they do not know how to begin a sentence, there is very little to say about writing short stories unless you are a professional explainer. If you can do it, you don’t have to explain it. If you can not do it, no explanation will ever help.

A few things I have found to be true. If you leave out important things or events that you know about, the story is strengthened. If you leave or skip something because you do not know it, the story will be worthless. The test of any story is how very good the stuff is that you, not your editors, omit. A story in this book called “Big Two-Hearted River” is about a boy coming home beat to the wide from a war. Beat to the wide was an earlier and possibly more severe form of beat, since those who had it were unable to comment on this condition and could not suffer that it be mentioned in their presence. So the war, all mention of the war, anything about the war, is omitted. The river was the Fox River, by Seney, Michigan, not the Big Two-Hearted. The change of name was made purposely, not from ignorance nor carelessness but because Big Two-Hearted River is poetry, and because there were many Indians in the story, just as the war was in the story, and none of the Indians nor the war appeared. As you see, it is very simple and easy to explain.

In a story called “A Sea Change,” everything is left out. I had seen the couple in the Bar Basque in St.-Jean-de-Luz and I knew the story too too well, which is the squared root of well, and use any well you like except mine. So I left the story out. But it is all there. It is not visible but it is there.

It is very hard to talk about your work since it implies arrogance or pride. I have tried to get rid of arrogance and replace it with humility and I do all right at that sometimes, but without pride I would not wish to continue to live nor to write and I publish nothing of which I am not proud. You can take that any way you like, Jack. I might not take it myself. But maybe we’re built different.

Another story is “Fifty Grand.” This story originally started like this:

“‘How did you handle Benny so easy, Jack?’ Soldier asked him.

“‘Benny’s an awful smart boxer,’ Jack said. ‘All the time he’s in there, he’s thinking. All the time he’s thinking, I was hitting him.’”

I told this story to Scott Fitzgerald in Paris before I wrote “Fifty Grand” trying to explain to him how a truly great boxer like Jack Britton functioned. I wrote the story opening with that incident and when it was finished I was happy about it and showed it to Scott. He said he liked the story very much and spoke about it in so fulsome a manner that I was embarrassed. Then he said, “There is only one thing wrong with it, Ernest, and I tell you this as your friend. You have to cut out that old chestnut about Britton and Leonard.”

At that time my humility was in such ascendance that I thought he must have heard the remark before or that Britton must have said it to someone else. It was not until I had published the story, from which I had removed that lovely revelation of the metaphysics of boxing that Fitzgerald in the way his mind was functioning that year so that he called an historic statement an “old chestnut” because he had heard it once and only once from a friend, that I realized how dangerous that attractive virtue, humility, can be. So do not be too humble, gentlemen. Be humble after but not during the action. They will all con you, gentlemen. But sometimes it is not intentional. Sometimes they simply do not know. This is the saddest state of writers and the one you will most frequently encounter. If there are no questions, let us press on.

My loyal and devoted friend Fitzgerald, who was truly more interested in my own career at this point than in his own, sent me to Scribner’s with the story. It had already been turned down by Ray Long of Cosmopolitan Magazine because it had no love interest. That was okay with me since I eliminated any love interest and there were, purposely, no women in it except for two broads. Enter two broads as in Shakespeare, and they go out of the story. This is unlike what you will hear from your instructors, that if a broad comes into a story in the first paragraph, she must reappear later to justify her original presence. This is untrue, gentlemen. You may dispense with her, just as in life. It is also untrue that if a gun hangs on the wall when you open up the story, it must be fired by page fourteen. The chances are, gentlemen, that if it hangs upon the wall, it will not even shoot. If there are no questions, shall we press on? Yes, the unfireable gun may be a symbol. That is true. But with a good enough writer, the chances are some jerk just hung it there to look at. Gentlemen, you can’t be sure. Maybe he is queer for guns, or maybe an interior decorator put it there. Or both.

So with pressure by Max Perkins on the editor, Scribner’s Magazine agreed to publish the story and pay me two hundred and fifty dollars, if I would cut it to a length where it would not have to be continued into the back of the book. They call magazines books. There is significance in this but we will not go into it. They are not books, even if they put them in stiff covers. You have to watch this, gentlemen. Anyway, I explained without heat nor hope, seeing the built-in stupidity of the editor of the magazine and his intransigence, that I had already cut the story myself and that the only way it could be shortened by five hundred words and make sense was to amputate the first five hundred. I had often done that myself with stories and it improved them. It would not have improved this story but I thought that was their ass not mine. I would put it back together in a book. They read differently in a book anyway. You will learn about this.

No, gentlemen, they would not cut the first five hundred words. They gave it instead to a very intelligent young assistant editor who assured me he could cut it with no difficulty. That was just what he did on his first attempt, and any place he took words out, the story no longer made sense. It had been cut for keeps when I wrote it, and afterwards at Scott’s request I’d even cut out the metaphysics which, ordinarily, I leave in. So they quit on it finally and eventually, I understand, Edward Weeks got Ellery Sedgwick to publish it in the Atlantic Monthly . Then everyone wanted me to write fight stories and I did not write any more fight stories because I tried to write only one story on anything, if I got what I was after, because Life is very short if you like it and I knew that even then. There are other things to write about and other people who write very good fight stories. I recommend to you “The Professional” by W. C. Heinz.

Yes, the confidently cutting young editor became a big man on Reader’s Digest . Or didn’t he? I’ll have to check that. So you see, gentlemen, you never know and what you win in Boston you lose in Chicago. That’s symbolism, gentlemen, and you can run a saliva test on it. That is how we now detect symbolism in our group and so far it gives fairly satisfactory results. Not complete, mind you. But we are getting in to see our way through. Incidently, within a short time Scribner’s Magazine was running a contest for long short stories that broke back into the back of the book, and paying many times two hundred and fifty dollars to the winners.

Now since I have answered your perceptive questions, let us take up another story.

This story is called “The Light of the World.” I could have called it “Behold I Stand at the Door and Knock” or some other stained-glass window title, but I did not think of it and actually “The Light of the World” is better. It is about many things and you would be ill-advised to think it is a simple tale. It is really, no matter what you hear, a love letter to a whore named Alice who at the time of the story would have dressed out at around two hundred and ten pounds. Maybe more. And the point of it is that nobody, and that goes for you, Jack, knows how we were then from how we are now. This is worse on women than on us, until you look into the mirror yourself some day instead of looking at women all the time, and in writing the story I was trying to do something about it. But there are very few basic things you can do anything about. So I do what the French call constater . Look that up. That is what you have to learn to do, and you ought to learn French anyway if you are going to understand short stories, and there is nothing rougher than to do it all the way. It is hardest to do about women and you must not worry when they say there are no such women as those you wrote about. That only means your women aren’t like their women. You ever see any of their women, Jack? I have a couple of times and you would be appalled and I know you don’t appall easy.

What I learned constructive about women, not just ethics like never blame them if they pox you because somebody poxed them and lots of times they don’t even know they have it—that’s in the first reader for squares—is, no matter how they get, always think of them the way they were on the best day they ever had in their lives. That’s about all you can do about it and that is what I was trying for in the story.

Now there is another story called “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” Jack, I get a bang even yet from just writing the titles. That’s why you write, no matter what they tell you. I’m glad to be with somebody I know now and those feecking students have gone. They haven’t? Okay. Glad to have them with us. It is in you that our hope is. That’s the stuff to feed the troops. Students, at ease.

This is a simple story in a way, because the woman who I knew very well in real life but then invented of, to make the woman for this story, is a bitch for the full course and doesn’t change. You’ll probably never meet the type because you haven’t got the money. I haven’t either but I get around. Now this woman doesn’t change. She has been better, but she will never be any better anymore. I invented her complete with handles from the worst bitch I knew (then) and when I first knew her she’d been lovely. Not my dish, not my pigeon, not my cup of tea, but lovely for what she was and I was her all of the above which is whatever you make of it. This is as close as I can put it and keep it clean. This information is what you call the background of a story. You throw it all away and invent from what you know. I should have said that sooner. That’s all there is to writing. That, a perfect ear—call it selective—absolute pitch, the devotion to your work and respect for it that a priest of God has for his, and then have the guts of a burglar, no conscience except to writing, and you’re in gentlemen. It’s easy. Anybody can write if he is cut out for it and applies himself. Never give it a thought. Just have those few requisites. I mean the way you have to write now to handle the way now is now. There was a time when it was nicer, much nicer and all that has been well written by nicer people. They are all dead and so are their times, but they handled them very well. Those times are over and writing like that won’t help you now.

But to return to this story. The woman called Margot Macomber is no good to anybody now except for trouble. You can bang her but that’s about all. The man is a nice jerk. I knew him very well in real life, so invent him too from everything I know. So he is just how he really was, only, he is invented. The White Hunter is my best friend and he does not care what I write as long as it is readable, so I don’t invent him at all. I just disguise him for family and business reasons, and to keep him out of trouble with the Game Department. He is the furthest thing from a square since they invented the circle, so I just have to take care of him with an adequate disguise and he is as proud as though we both wrote it, which actually you always do in anything if you go back far enough. So it is a secret between us. That’s all there is to that story except maybe the lion when he is hit and I am thinking inside of him really, not faked. I can think inside of a lion, really. It’s hard to believe and it is perfectly okay with me if you don’t believe it. Perfectly. Plenty of people have used it since, though, and one boy used it quite well, making only one mistake. Making any mistake kills you. This mistake killed him and quite soon everything he wrote was a mistake. You have to watch yourself, Jack, every minute, and the more talented you are the more you have to watch these mistakes because you will be in faster company. A writer who is not going all the way up can make all the mistakes he wants. None of it matters. He doesn’t matter. The people who like him don’t matter either. They could drop dead. It wouldn’t make any difference. It’s too bad. As soon as you read one page by anyone you can tell whether it matters or not. This is sad and you hate to do it. I don’t want to be the one that tells them. So don’t make any mistakes. You see how easy it is? Just go right in there and be a writer.

That about handles that story. Any questions? No, I don’t know whether she shot him on purpose any more than you do. I could find out if I asked myself because I invented it and I could go right on inventing. But you have to know where to stop. That is what makes a short story. Makes it short at least. The only hint I could give you is that it is my belief that the incidence of husbands shot accidentally by wives who are bitches and really work at it is very low. Should we continue?

If you are interested in how you get the idea for a story, this is how it was with “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.” They have you ticketed and always try to make it that you are someone who can only write about theirself. I am using in this lecture the spoken language, which varies. It is one of the ways to write, so you might as well follow it and maybe you will learn something. Anyone who can write can write spoken, pedantic, inexorably dull, or pure English prose, just as slot machines can be set for straight, percentage, give-away or stealing. No one who can write spoken ever starves except at the start. The others you can eat irregularly on. But any good writer can do them all. This is spoken, approved for over fourteen I hope. Thank you.

Anyway we came home from Africa, which is a place you stay until the money runs out or you get smacked, one year and at quarantine I said to the ship news reporters when somebody asked me what my projects were that I was going to work and when I had some more money go back to Africa. The different wars killed off that project and it took nineteen years to get back. Well it was in the papers and a really nice and really fine and really rich woman invited me to tea and we had a few drinks as well and she had read in the papers about this project, and why should I have to wait to go back for any lack of money? She and my wife and I could go to Africa any time and money was only something to be used intelligently for the best enjoyment of good people and so forth. It was a sincere and fine and good offer and I liked her very much and I turned down the offer.

So I get down to Key West and I start to think what would happen to a character like me whose defects I know, if I had accepted that offer. So I start to invent and I make myself a guy who would do what I invent. I know about the dying part because I had been through all that. Not just once. I got it early, in the middle and later. So I invent how someone I know who cannot sue me—that is me—would turn out, and put into one short story things you would use in, say, four novels if you were careful and not a spender. I throw everything I had been saving into the story and spend it all. I really throw it away, if you know what I mean. I am not gambling with it. Or maybe I am. Who knows? Real gamblers don’t gamble. At least you think they don’t gamble. They gamble, Jack, don’t worry. So I make up the man and the woman as well as I can and I put all the true stuff in and with all the load, the most load any short story ever carried, it still takes off and it flies. This makes me very happy. So I thought that and the Macomber story are as good short stories as I can write for a while, so I lose interest and take up other forms of writing.

Any questions? The leopard? He is part of the metaphysics. I did not hire out to explain that nor a lot of other things. I know, but I am under no obligation to tell you. Put it down to omertà . Look that word up. I dislike explainers, apologists, stoolies, pimps. No writer should be any one of those for his own work. This is just a little background, Jack, that won’t do either of us any harm. You see the point, don’t you? If not it is too bad.

That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t explain for, apologize for or pimp or tout for some other writer. I have done it and the best luck I had was doing it for Faulkner. When they didn’t know him in Europe, I told them all how he was the best we had and so forth and I over-humbled with him plenty and built him up about as high as he could go because he never had a break then and he was good then. So now whenever he has a few shots, he’ll tell students what’s wrong with me or tell Japanese or anybody they send him to, to build up our local product. I get tired of this but I figure what the hell he’s had a few shots and maybe he even believes it. So you asked me just now what I think about him, as everybody does and I always stall, so I say you know how good he is. Right. You ought to. What is wrong is he cons himself sometimes pretty bad. That may just be the sauce. But for quite a while when he hits the sauce toward the end of a book, it shows bad. He gets tired and he goes on and on, and that sauce writing is really hard on who has to read it. I mean if they care about writing. I thought maybe it would help if I read it using the sauce myself, but it wasn’t any help. Maybe it would have helped if I was fourteen. But I was only fourteen one year and then I would have been too busy. So that’s what I think about Faulkner. You ask that I sum it up from the standpoint of a professional. Very good writer. Cons himself now. Too much sauce. But he wrote a really fine story called “The Bear” and I would be glad to put it in this book for your pleasure and delight, if I had written it. But you can’t write them all, Jack.

It would be simpler and more fun to talk about other writers and what is good and what is wrong with them, as I saw when you asked me about Faulkner. He’s easy to handle because he talks so much for a supposed silent man. Never talk. Jack, if you are a writer, unless you have the guy write it down and have you go over it. Otherwise, they get it wrong. That’s what you think until they play a tape back at you. Then you know how silly it sounds. You’re a writer aren’t you? Okay, shut up and write. What was that question?

Want to keep reading? Subscribe and save 33%.

Subscribe now, already a subscriber sign in below..

Link your subscription

Forgot password?

Featured Audio

Season 4 trailer.

The Paris Review Podcast returns with a new season, featuring the best interviews, fiction, essays, and poetry from America’s most legendary literary quarterly, brought to life in sound. Join us for intimate conversations with Sharon Olds and Olga Tokarczuk; fiction by Rivers Solomon, Jun'ichirō Tanizaki, and Zach Williams; poems by Terrance Hayes and Maggie Millner; nonfiction by Robert Glück, Jean Garnett, and Sean Thor Conroe; and performances by George Takei, Lena Waithe, and many others. Catch up on earlier seasons, and listen to the trailer for Season 4 now.

Suggested Reading

The Black Madonna

“For all her poise and stillness, the Black Madonna was not static. She looked out, and in her eyes were glints of recognition.”

Arts & Culture

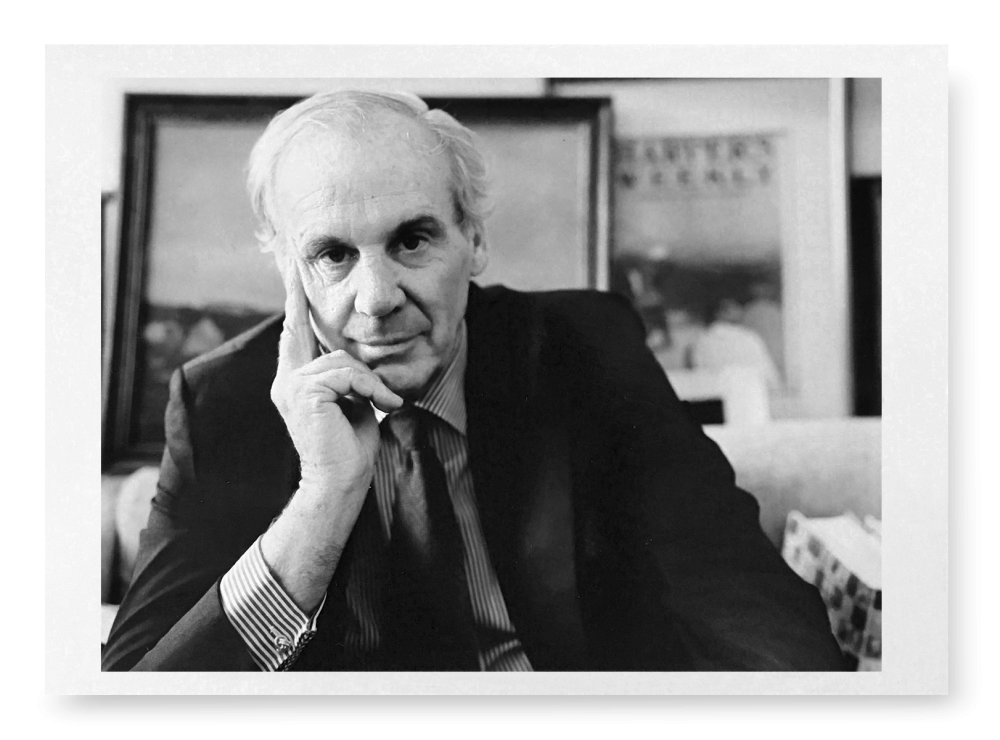

The art of editing no. 4.

By the time I arrived in New York in the late seventies, Lapham was established in the city’s editorial elite, up there with William Shawn at The New Yorker and Barbara Epstein and Bob Silvers at The New York Review of Books . He was a glamorous fixture at literary parties and a regular at Elaine’s. In 1988, he raised plutocratic hackles by publishing Money and Class in America , a mordant indictment of our obsession with wealth. For a brief but glorious couple of years, he hosted a literary chat show on public TV called Bookmark , trading repartee with guests such as Joyce Carol Oates, Gore Vidal, Alison Lurie, and Edward Said. All the while, a new issue of Harper’s would hit the newsstands every month, with a lead essay by Lapham that couched his erudite observations on American society and politics in Augustan prose.

Today Lapham is the rare surviving eminence from that literary world. But he has managed to keep a handsome bit of it alive—so I observed when I went to interview him last summer in the offices of Lapham’s , a book-filled, crepuscular warren on a high floor of an old building just off Union Square. There he presides over a compact but bustling editorial operation, with an improbably youthful crew of subeditors. One LQ intern, who had also done stints at other magazines, told me that Lapham was singular among top editors for the personal attention he showed to each member of his staff.

Our conversation took place over several sessions, each around ninety minutes. Despite the heat, he was always impeccably attired: well-tailored blue blazer, silk tie, cuff links, and elegant loafers with no socks. He speaks in a relaxed baritone, punctuated by an occasional cough of almost orchestral resonance—a product, perhaps, of the Parliaments he is always dashing outside to smoke. The frequency with which he chuckles attests to a vision of life that is essentially comic, in which the most pervasive evils are folly and pretension.

I was familiar with such aspects of the Lapham persona. But what surprised me was his candid revelation of the struggle and self-doubt that lay behind what I had imagined to be his effortlessness. Those essays, so coolly modulated and intellectually assured, are the outcome of a creative process filled with arduous redrafting, rejiggering, revision, and last-minute amendment in the teeth of the printing press. And it is a creative process that always begins—as it did with his model, Montaigne—not with a dogmatic axiom to be unpacked but in a state of skeptical self-questioning: What do I really know? If there a unifying core to Lapham’s dual career as an editor and an essayist, that may be it.

— Jim Holt

From the Archive, Issue 229

Subscribe for free: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Amazon Music

Papers of Ernest Hemingway

The Ernest Hemingway Collection is the most comprehensive Hemingway archives in the world and essential to anyone pursuing a definitive or in-depth study of Hemingway and his writing. In addition to the author’s personal papers , the collection includes approximately 11,000 photographs . The Library also houses the personal papers of Hemingway family members, friends, and scholars.

For more information please contact [email protected] . For more information about Hemingway-related audiovisual materials, please contact [email protected] .

Collection Development Policy

Learn more about the Hemingway collection development policy .

Digitized Materials

A growing number of Hemingway photographs has been digitized and many are available here: Hemingway media galleries . Learn more about the Ernest Hemingway audiovisual materials .

Content Note

Our digitized collections and finding aids (collection guides) contain some content and descriptions that may be harmful or difficult to view. Learn more.

You are using an outdated browser. This site may not look the way it was intended for you. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

London School of Journalism

- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7432 8140

- [email protected]

- Student log in

Search courses

English literature essays, introducing ernest hemingway.

Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961) occupies a prominent place in the annals of American Literary history by virtue of his revolutionary role in the arena of twentieth century American fiction. By rendering a realistic portrayal of the inter-war period with its disillusionment and disintegration of old values, Hemingway has presented the predicament of the modern man in 'a world which increasingly seeks to reduce him to a mechanism, a mere thing'. [1] Written in a simple but unconventional style, with the problems of war, violence and death as their themes, his novels present a symbolic interpretation of life.

Ernest Miller Hemingway was born in 1899 in Oak Park, Illinois, in an orthodox higher middle class family as the second of six children. His mother, Mrs. Grace Hale Hemingway, an ex-opera singer, was an authoritarian woman who had reduced his father, Mr. Clarence Edmunds Hemingway, a physician, to the level of a hen-pecked husband. Hemingway had a rather unhappy childhood on account of his 'mother's, bullying relations with his father'. [2] He grew up under the influence of his father who encouraged him to develop outdoor interests such as swimming, fishing and hunting. His early boyhood was spent in the northern woods of Michigan among the native Indians, where he learned the primitive aspects of life such as fear, pain, danger and death.

At school, he had a brilliant academic career and graduated at the age of 17 from the Oak Park High School. In 1917 he joined the Kansas City Star as a war correspondent. The following year he participated in the World War by volunteering to work as an ambulance driver on the Italian front, where he was badly wounded but twice decorated for his services. He returned to America in 1919 and married Hadley Richardson in 1921. This was the first of a series of unhappy marriages and divorces. The next year, he reported on the Greco-Turkish War and two years later, gave up journalism to devote himself to fiction. He settled in Paris, where he came into contact with fellow American expatriates such as Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound. 'From her (Gertrude Stein) as well as from Ezra Pound and others, he learned the discipline of his craft - the taut monosyllabic vocabulary, stark dialogue, and understated emotion that are the hallmarks of the Hemingway style'. [3]

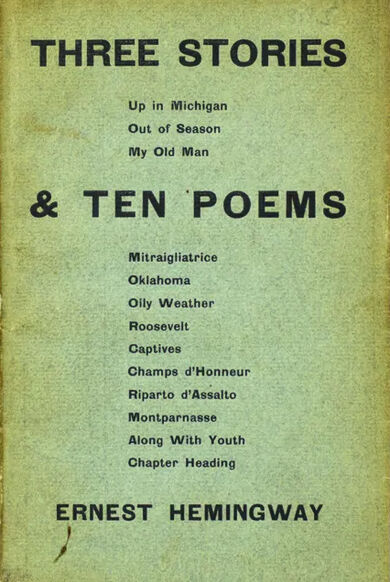

Hemingway's first two published works were In Our Time and Three Stories and Ten Poems . These early stories foreshadow his mature technique and his concern for values in a corrupt and indifferent world. But it was The Torrents of Spring , which appeared in 1926, that established him as a writer of repute. His international reputation was firmly secured by his next three books, The Sun Also Rises, Men Without Women and A Farewell to Arms . This was only the beginning of an illustrious career, with an impressive output of several novels and short stories, a collection of poems and The Fifth Column , a play.

Hemingway was passionately involved with bullfighting, big game hunting and deep sea fishing, and his writing reflects this. He visited Spain during the Civil War and his experiences on the war front form the theme of the best seller For Whom the Bell Tolls . When the Second World War broke out, he took an active part and offered to lead a suicide squadron against the Nazi U Boats. But in the course of the war, he fell ill and was nursed by Mary Walsh, who eventually became his fourth wife and continued to be with him until his death. In 1954, he survived two plane crashes in the African jungle. His adventures and tryst with destiny made him a celebrity all over the English speaking world.

Hemingway began the final phase of his career as a resident of Cuba. There he continued his life of well advertised hunting and adventure, being often in the forefront of literary publicity and controversy. This phase is marked by a decline in his creative genius which, however, attained its original stature with the publication of The Old Man and The Sea in 1952. It was an immense success and won him the Nobel Prize for literature in 1954.

His fortunes took a turn for the worse, when Fidel Castro came to power and ordered the Americans out of Cuba. It proved a great shock to Hemingway and added to his agony over the decline of his creative talents. He fell victim to acute fits of depression and attempted suicide twice. He was hospitalized and treated for his psychological problems. But after a few months of doubts, anxieties and depression, he shot himself on the 2nd of July 1961, bringing to an end one of the most eventful and colorful lives of our times.

Hemingway's literary genius was molded by cultural and literary influences. 'Mark Twain, the War and The Bible were the major influences that shaped Hemingway's thought and art'. [4] During his sojourn in Paris, Hemingway also came into contact with eminent literary figures such as Fitzgerald, Sherwood Anderson, D.H. Lawrence and even T.S. Eliot. 'All or some of them might have left their imprint on him'. [5] Hemingway also acknowledged that he had learnt a great deal from the writings of Joseph Conrad. Besides these, his early experiences in Michigan colored his writing to some extent. The most important influence that left a deep impact on his genius was the nightmarish experiences which he himself had undergone in the two World Wars.

As a novelist, Hemingway is often assigned a place among the writers of `the lost generation', along with Faulkner, Fitzgerald, John Dos Passos and Sinclair Lewis. 'These writers, including Ernest Hemingway, tried to show the loss the First World War had caused in the social, moral and psychological spheres of human life'. [6] They also reveal the horror, the fear and the futility of human existence. True, Hemingway has echoed the longings and frustrations that are typical of these writers, but his work is distinctly different from theirs in its philosophy of life. In his novels 'a metaphysical interest in man and his relation to nature' [7] can be discerned.

Hemingway has been immortalized by the individuality of his style. Short and solid sentences, delightful dialogues, and a painstaking hunt for an apt word or phrase to express the exact truth, are the distinguishing features of his style. He 'evokes an emotional awareness in the reader by a highly selective use of suggestive pictorial detail, and has done for prose what Eliot has done for poetry'. [8] In his accurate rendering of sensuous experience, Hemingway is a realist. As he himself has stated in Death in the Afternoon , his main concern was 'to put down what really happened in action; what the actual things were that produced the emotion you experienced'. [9] This surface realism of his works often tends to obscure the ultimate aim of his fiction. This has often resulted in the charge that there is a lack of moral vision in his novels. Leon Edel has attacked Hemingway for his `Lack of substance' as he called it. According to him, Hemingway's fiction is deficient in serious subject matter. 'It is a world of superficial action and almost wholly without reflection - such reflection as there is tends to be on a rather crude and simplified level'. [10]

But such a casual dismissal as this, presenting Hemingway as a writer devoid of `high seriousness', is not justified. Though Hemingway is apparently a realist who has a predilection for physical action, he is essentially a philosophical writer. His works should be read and interpreted in the light of his famous `Iceberg theory': 'The dignity of the movement of an iceberg is due to only one eighth of it being above the water'. [11] This statement throws light on the symbolic implications of his art. He makes use of physical action to provide a symbolical interpretation of the nature of man's existence. It can be convincingly proved that, 'While representing human life through fictional forms, he has consistently set man against the background of his world and universe to examine the human situation from various points of view'. [12]

In this aspect, he belongs to the tradition of Hawthorne, Poe and Melville, in whose fiction darkness has been used as a major theme to present the lot of man in this world. Hemingway's concern for the predicament of the individual resembles the outlook of these `nocturnal writers'. 'As with them, a moral awareness springs from his awareness of the larger life of the universe. Compared with the larger life of the universe, the individual is a puny thing, a tragic thing. But in this larger life of the universe, the individual has his place of glory'. [13] This awareness of the futility of human existence led Hemingway to deal with the themes of violence, darkness and death in his novels. By presenting the darker side of life, he tries to explore the nature of the individual's predicament in this world.

What attitude should a man take toward a world in which, for reasons of the world's own making and not of his own, he is fundamentally out of place? What personal happiness can he expect to find in a world seething with violence ... what values could one respect when ethical values as a whole seemed university disrespected? [14]

This metaphysical concern about the nature of the individual's existence in relation to the world made Hemingway conceive his protagonists as alienated individuals fighting a losing battle against the odds of life with courage, endurance and will as their only weapons. The Hemingway hero is a lonely individual, wounded either physically or emotionally. He exemplifies a code of courageous behavior in a world of irrational destruction. 'He offers up and exemplifies certain principles of honor, courage and endurance in a life of tension and pain which make a man a man'. [15] Violence, struggle, suffering and hardships do not make him in any way pessimistic. Though the `vague unknown' continues to lure him and frustrate his hopes and purposes, he does not admit defeat. Death rather than humiliation, stoical endurance rather than servile submission are the cardinal virtues of the Hemingway hero.

A close examination of Hemingway's fiction reveals that in his major novels he enacts `the general drama of human pain', and that he has 'used the novel form in order to pose symbolic questions about life'. [16] The trials and tribulations undergone by his protagonists are symbolic of man's predicament in this world. He views life as a perpetual struggle in which the individual has to assert the supremacy of his free will over forces other than himself. In order to assert the dignity of his existence, the individual has to wage a relentless battle against a world which refuses him any identity or fulfillment.

To sum up, Hemingway, in his novels and short stories, presents human life as a perpetual struggle which ends only in death. It is of no avail to fight this battle, where man is reduced to a pathetic figure by forces both within and without. However, what matters is the way man faces the crisis and endures the pain inflicted upon him by the hostile powers that be, be it his own physical limitation or the hostility of society or the indifference of unfeeling nature. The ultimate victory depends on the way one faces the struggle. In a world of pain and failure, the individual also has his own weapon to assert the dignity of his existence. He has the freedom of will to create his own values and ideals. In order to achieve this end, he has to carry on an incessant battle against three oppressive forces, namely, the biological, the social and the environmental barriers of this world. According to Hemingway, the struggle between the individual and the hostile deterministic forces takes places at these three different levels. Commenting on this aspect of the existential struggle found in Hemingway's fiction, Charles Child Walcutt has observed that, 'the conflict between the individual needs and social demands is matched by the contest between feeling man and unfeeling universe, and between the spirit of the individual and his biological limitations'. [17] This observation is probably the right key to understand Hemingway, the man and the novelist.

Endnotes 1. Cleanth Brooks, 'Ernest Hemingway, Man On His Moral Uppers' The Hidden God (New Haven and London: Yale Press, 1969), p. 6. 2. Mark Spilka, 'Hemingway and Fauntleroy, An Androgynous Pursuit', American Novelists Revisited ed. Fritz Flishmann (Boston, Massachusetts G.K. Hall and Co., 1982), p. 346. 3. Abraham H. Lass, A student's Guide to 50 American Novelists (New York: Washington Square `Press, 1970), p. 175. 4. Mrs. Mary S. David and Dr. Varshney, A History of American Literature (Barilly: Student Store, 1983), p. 315. Hereinafter cited as Mary S. David. 5. Mary S. David. p.312 6. Mary S. David. p. 315. 7. P.G. Rama Rao, Ernest Hemingway, A Study in Narrative Technique (New Delhi: S. Chand and Co., 1980). p. 4. Hereafter cited as Rama Rao. 8. Rama Rao, p. 31. 9. Ernest Hemingway, Death in the Afternoon (London: Grafton Books, 1986), p. 8. Hereafter cited as Death in the Afternoon. 10. Leon Edel, 'The Art of Evasion' in Hemingway, A Collection of Critical Essays , ed. Robert P. Weeks (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1962), p. 170. 11. Death in the Afternoon , p. 171. 12. B.R. Mullik, Hemingway Studies in American Literature (New Delhi: S. Chand and Co., 1972), p. 8. 13. Chaman Nahal, The Narrative Pattern in Ernest Hemingway's Fiction (New Delhi: Vikas Publication, 1971). p. 26. 14. W.M. Frohock, The Novel of Violence in American Literature (Cambridge, Massachusetts; Cambridge University. 15. Philip Young, 'Ernest Hemingway' Seven Modern American Novelists, an Introduction ed. William Van O' Connor (Minneapolis - The University of Minnesota Press, 1966), p. 158. Hereafter cited as Philip Young. 16. W.R. Goodman, A Manual of American Literature (Delhi: Doabe House, n.d), p. 357. Hereafter cited as Goodman 17. Charles Child Walcutt, American Literary Naturalism, A Divided Stream (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1974), p. 275.

Bibliography Brooks, Cleanth 'Ernest Hemingway, Man On His Moral Uppers' The Hidden God . New Haven and London: Yale Press, 1969. David, Mary S. and Dr. Varshney, A History of American Literature (Bareilly: Student Store, 1983. Edel, Leon 'The Art of Evasion', Hemingway, A Collection of Critical Essays , Ed. Robert P. Weeks Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1962. Frohock, W.M. The Novel of Violence in American Literature . Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 1957. Goodman, W.R. A Manual of American Literature . New Delhi: Doaba House 1968. Hemingway, Ernest. Death in the Afternoon . London: Grafton Books, 1986. Lass, Abraham H. A student's Guide to 50 American Novelists . New York: Washington Square Press, 1970. Mullik, B.R. Hemingway - Studies in American Literature New Delhi: S. Chand and Co., 1972. Nahal, Chaman. The Narrative Pattern in Ernest Hemingway's Fiction . New Delhi: Vikas Publication, 1971. Rao, P.G. Rama. Ernest Hemingway, A Study in Narrative Technique . New Delhi: S. Chand and Co., 1980. Spilka, Mark. 'Hemingway and Fauntleroy, An Androgynous Pursuit', American Novelists Revisited Ed. Fritz Flishmann .Boston: G.K. Hall and Co., 1982. Walcutt, Charles Child. American Literary Naturalism - A Divided Stream . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1974. Young, Philip. 'Ernest Hemingway', Seven Modern American Novelists,- An Introduction . Ed. William Van O' Connor. Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press, 1966.

© Februaruy 2003, Professor Ganesan Balakrishnan, Ph.D Head, PG & Research Dept. of English, Pachaiyappa's College (Affiliated to the University of Madras), Chennai-30, Tamil Nadu, India

- Aristotle: Poetics

- Matthew Arnold

- Margaret Atwood: Bodily Harm and The Handmaid's Tale

- Margaret Atwood 'Gertrude Talks Back'

- Jonathan Bayliss

- Lewis Carroll, Samuel Beckett

- Saul Bellow and Ken Kesey

- John Bunyan: The Pilgrim's Progress and Geoffrey Chaucer: The Canterbury Tales

- T S Eliot, Albert Camus

- Castiglione: The Courtier

- Kate Chopin: The Awakening

- Joseph Conrad: Heart of Darkness

- Charles Dickens

- John Donne: Love poetry

- John Dryden: Translation of Ovid

- T S Eliot: Four Quartets

- William Faulkner: Sartoris

- Henry Fielding

- Ibsen, Lawrence, Galsworthy

- Jonathan Swift and John Gay

- Oliver Goldsmith

- Graham Greene: Brighton Rock

- Thomas Hardy: Tess of the d'Urbervilles

- Nathaniel Hawthorne: The Scarlet Letter

- Ernest Hemingway

- Jon Jost: American independent film-maker

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Will McManus

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ian Mackean

- James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: Ben Foley

- Carl Gustav Jung

- Jamaica Kincaid, Merle Hodge, George Lamming

- Rudyard Kipling: Kim

- D. H. Lawrence: Women in Love

- Henry Lawson: 'Eureka!'

- Machiavelli: The Prince

- Jennifer Maiden: The Winter Baby

- Ian McEwan: The Cement Garden

- Toni Morrison: Beloved and Jazz

- R K Narayan's vision of life

- R K Narayan: The English Teacher

- R K Narayan: The Guide

- Brian Patten

- Harold Pinter

- Sylvia Plath and Alice Walker

- Alexander Pope: The Rape of the Lock

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Doubles

- Jean Rhys: Wide Sargasso Sea. Charlotte Bronte: Jane Eyre: Symbolism

- Shakespeare: Twelfth Night

- Shakespeare: Hamlet

- Shakespeare: Shakespeare's Women

- Shakespeare: Measure for Measure

- Shakespeare: Antony and Cleopatra

- Shakespeare: Coriolanus

- Shakespeare: The Winter's Tale and The Tempest

- Sir Philip Sidney: Astrophil and Stella

- Edmund Spenser: The Faerie Queene

- Tom Stoppard

- William Wordsworth

- William Wordsworth and Lucy

- Studying English Literature

- The author, the text, and the reader

- What is literary writing?

- Indian women's writing

- Renaissance tragedy and investigator heroes

- Renaissance poetry

- The Age of Reason

- Romanticism

- New York! New York!

- Alice, Harry Potter and the computer game

- The Spy in the Computer

- Photography and the New Native American Aesthetic

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

Enhanced Page Navigation

- Article about Ernest Hemingway: A case of identity: Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway

A case of identity: Ernest Hemingway

by Anders Hallengren *

The recognition of Hemingway as a major and representative writer of the United States of America, was a slow but explosive process. His emergence in the western canon was an even more adventurous voyage. His works were burnt in the bonfire in Berlin on May 10, 1933 as being a monument of modern decadence. That was a major proof of the writer’s significance and a step toward world fame.

To read Hemingway has always produced strong reactions. When his parents received the first copies of their son’s book In Our Time (1924), they read it with horror. Furious, his father sent the volumes back to the publisher, as he could not tolerate such filth in the house. Hemingway’s apparently coarse, crude, vulgar and unsentimental style and manners appeared equally shocking to many people outside his family. On the other hand, this style was precisely the reason why a great many other people liked his work. A myth, exaggerating those features, was to be born.

Hemingway in our time

After he had committed suicide at Ketchum, Idaho, in 1961, the literary position of the 1954 Nobel Laureate changed significantly and has, in a way, even become stronger. This is partly due to several posthumous works and collections that show the author’s versatility – A Moveable Feast (1964), By-Line (1967), 88 Poems (1979), and Selected Letters (1981). It is also the result of painstaking and successful Hemingway research, in which The Hemingway Society (USA) has played an important role since 1980.

Another result of this enduring interest is that many new aspects of Hemingway’s life and works that were previously obscured by his public image have now emerged into the light. On the other hand, posthumously published novels, such as Islands in the Stream (1970) and The Garden of Eden (1986), have disappointed many of the old Hemingway readers. However, rather than bearing witness to declining literary power, (which, considering the author’s declining health would, indeed, be a rather trivial observation even if it were true) the late works confront us with a reappraisal and reconsideration of basic values. They also display an unbiased seeking and experimentation, as if the author was losing both his direction and his footing, or was becoming unrestrained in a new way. Just as modern Hemingway scholarship has added immensely to the depth of our understanding of Hemingway – making him more and more difficult to define! – these works reveal and stress a complexity that may cause bewilderment or relief, depending on what perspective one adopts.

The “hard-boiled” style

The slang word “hard-boiled”, used to describe characters and works of art, was a product of twentieth century warfare. To be “hard-boiled” meant to be unfeeling, callous, coldhearted, cynical, rough, obdurate, unemotional, without sentiment. Later to become a literary term, the word originated in American Army World War I training camps, and has been in common, colloquial usage since about 1930.

Contemporary literary criticism regarded Ernest Hemingway’s works as marked by his use of this style, which was typical of the era. Indeed, in many respects they were regarded as the embodiment and symbol of hard-boiled literature.

However, neither Hemingway the man nor Hemingway the writer should be labeled “hard-boiled” – his style is the only aspect that deserves this epithet, and even that is ambiguous. Let us get down to basics, concentrate on one main feature in his literary style, and then turn to the alleged hard-boiled mind behind it, and his macho style of living and speaking.

A hard-boiled mind?

An unmatched introduction to Hemingway’s particular skill as a writer is the beginning of A Farewell to Arms, certainly one of the most pregnant opening paragraphs in the history of the modern American novel. In that passage the power of concentration reaches a peak, forming a vivid and charged sequence, as if it were a 10-second video summary. It is packed with events and excitement, yet significantly frosty, as if unresponsive and numb, like a silent flashback dream sequence in which bygone images return, pass in review and fade away, leaving emptiness and quietude behind them. The lapidary writing approaches the highest style of poetry, vibrant with meaning and emotion, while the pace is maintained by the exclusion of any descriptive redundancy, of obtrusive punctuation, and of superfluous or narrowing emotive signs:

IN the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains. In the bed of the river there were pebbles and boulders, dry and white in the sun, and the water was clear and swiftly moving and blue in the channels. Troops went by the house and down the road and the dust they raised powdered the leaves of the trees. The trunks of the trees too were dusty and the leaves fell early that year and we saw the troops marching along the road and the dust rising and leaves, stirred by the breeze, falling and the soldiers marching and afterwards the road bare and white except for the leaves.

At the end of the sixteenth chapter of Death in the Afternoon the author approaches a definition of the “hard-boiled” style:

“If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things.”

Ezra Pound taught him “to distrust adjectives” ( A Moveable Feast ). That meant creating a style in accordance with the esthetics and ethics of raising the emotional temperature towards the level of universal truth by shutting the door on sentiment, on the subjective.

A macho style of living and speaking.

The unwritten code

Later biographic research revealed, behind the macho façade of boxing, bullfighting, big-game hunting and deep-sea fishing he built up, a sensitive and vulnerable mind that was full of contradictions.

In Hemingway, sentimentality, sympathy, and empathy are turned inwards, not restrained, but vibrant below and beyond the level of fact and fable. The reader feels their presence although they are not visible in the actual words. That is because of Hemingway’s awareness of the relation between the truth of facts and events and his conviction that they produce corresponding emotions.

“Find what gave you the emotion; what the action was that gave you the excitement. Then write it down making it clear so the reader will see it too and have the same feeling as you had.”

That was the essence of his style, to focus on facts. Hemingway aimed at “the real thing, the sequence of motion and fact which made the emotion and which would be as valid in a year or in ten years or, with luck and if you stated it purely enough, always” ( Death in the Afternoon ). In Hemingway, we see a reaction against Romantic turgidity and vagueness: back to basics, to the essentials. Thus his new realism in a new key resembles the old Puritan simplicity and discipline; both of them refrained from exhibiting the sentimental, the relative.

Hemingway’s sincere and stern ambition was to approach Truth, clinging to an as yet unwritten code, a higher law which he referred to as “an absolute conscience as unchanging as the standard meter in Paris” ( Green Hills of Africa , I: 1).

Hemingway’s near-death experience

Though Hemingway seems to have seen himself and life in general reflected in war, he himself never became reconciled to it. His mind was in a state of civil war, fighting demons inwardly as well as outwardly. In the long run defeat is as revealing and fundamental as victory: we are all losers, defeated by death. To live is the only way to face the ordeal, and the ultimate ordeal in our lives is the opposite of life. Hence Hemingway’s obsession with death. Deep sea fishing, bull-fighting, boxing, big-game hunting, war, – all are means of ritualizing the death struggle in his mind – it is very explicit in books such as A Farewell to Arms and Death in the Afternoon, which were based on his own experience.

Escaping death during World War I.

Modern investigations into so-called Near-Death Experiences (NDE) such as those by Raymond Moody, Kenneth Ring and many others, have focused on a pattern of empirical knowledge gained on the threshold of death; a dream-like encounter with unknown border regions. There is a parallel in Hemingway’s life, connected with the occasion when he was seriously wounded at midnight on July 8, 1918, at Fossalta di Piave in Italy and nearly died. He was the first American to be wounded in Italy during World War I. Here is a case of NDE in Hemingway, and I think that is of basic importance, pertinent to the understanding of all Hemingway’s work. In A Farewell to Arms, an experience of this sort occurs to the ambulance driver Frederic Henry, Hemingway’s alter ego, wounded in the leg by shellfire in Italy. (Concerning the highly autobiographical nature of A Farewell to Arms, see Michael S. Reynolds’s documentary work Hemingway’s First War: The Making of A Farewell to Arms, Princeton University Press 1976). As regards the NDE, we can note the incidental expression “to go out in a blaze of light” (letter to his family, Milan Oct. 18, 1918), and the long statement about what had occurred: Milan, July 21, 1918 ( Selected Letters, ed. Carlos Baker, 1981).

Hemingway touched on that crucial experience in his life – what he had felt and thought – in the short story “Now I Lay Me” (1927):

“my soul would go out of my body … I had been blown up at night and felt it go out of me and go off and then come back”

– and again, briefly, in In Our Time in the lines on the death of Maera. It reappears, in another setting and form, in the image of immortality in the African story The Snows of Kilimanjaro, where the dying Harry knows he is going to the peak called “Ngàje Ngài”, which means, as explained in Hemingway’s introductory note, “the House of God”.

The coyote and the leopard

Hemingway’s seeming insensitive detachment is only superficial, a compulsive avoidance of the emotional, but not of the emotionally tinged or charged. The pattern of his rigid, dispassionate compressed style of writing and way of life gives a picture of a touching Jeremiad of human tragedy. Hemingway’s probe touches nerves, and they hurt. But through the web of failure and disillusion there emerges a picture of human greatness, of confidence even.

Hemingway was not the Nihilist he has often been called. As he belonged to the Protestant nay-saying tradition of American dissent, the spirit of the American Revolution, he denied the denial and acceded to the basic truth which he found in the human soul: the will to live, the will to persevere, to endure, to defy. The all-pervading sense of loss is, indirectly, affirmative. Hemingway’s style is a compulsive suppression of unbearable and inexpressible feelings in the chaotic world of his times, where courage and independence offered a code of survival. Sentiments are suppressed to the boil.

The frontier mentality had become universal – the individual is on his own, like a Pilgrim walking into the unknown with neither shelter nor guidance, thrown upon his own resources, his strength and his judgment. Hemingway’s style is the style of understatement since his hero is a hero of action, which is the human condition.

There is an illuminating text in William James (1842-1910) which is both significant and reminiscent, bridging the gap between Puritan moralism, its educational parables and exempla, and lost-generation turbulent heroism. In a letter written in Yosemite Valley to his son, Alexander, William James wrote:

“I saw a moving sight the other morning before breakfast in a little hotel where I slept in the dusty fields. The young man of the house had shot a little wolf called coyote in the early morning. The heroic little animal lay on the ground, with his big furry ears, and his clean white teeth, and his jolly cheerful little body, but his brave little life was gone. It made me think how brave all these living things are. Here little coyote was, without any clothes or house or books or anything, with nothing but his own naked self to pay his way with, and risking his life so cheerfully – and losing it – just to see if he could pick up a meal near the hotel. He was doing his coyote-business like a hero, and you must do your boy-business, and I my man-business bravely, too, or else we won’t be worth as much as a little coyote.” ( The Letters of William James, ed. Henry James, Little, Brown and Co.: Boston 1926.)

The courageous coyote thus serves as a moral example, illustrating a philosophy of life which says that it is worth jeopardizing life itself to be true to one’s own nature. That is precisely the point of the frozen leopard close to the western summit of Kilimanjaro in Hemingway’s famous short story. That is the explanation of what the leopard was seeking at that altitude, and the answer was given time and again in the works of Ernest Hemingway.

Jeopardizing life itself to be true to one’s own nature.

But what about the ugliness, then? What about all the evil, the crude, the rude, the rough, the vulgar aspects of his work, even the horror, which dismayed people? How could all that be compatible with moral standards? He justified the inclusion of such aspects in a letter to his “Dear Dad” in 1925:

“The reason I have not sent you any of my work is because you or Mother sent back the In Our Time books. That looked as though you did not want to see any. You see I am trying in all my stories to get the feeling of the actual life across – not to just depict life – or criticize it – but to actually make it alive. So that when you have read something by me you actually experience the thing. You can’t do this without putting in the bad and the ugly as well as what is beautiful. Because if it is all beautiful you can’t believe in it. Things aren’t that way. It is only by showing both sides – 3 dimensions and if possible 4 that you can write the way I want to.

So when you see anything of mine that you don’t like remember that I’m sincere in doing it and that I’m working toward something. If I write an ugly story that might be hateful to you or to Mother the next one might be one that you would like exceedingly.”

Hemingway family photo, 1909.

Merging gender in Eden

Like many other of his works, True at First Light was a blend of autobiography and fiction in which the author identified with the first person narrator. The author, who never kept a journal or wrote an autobiography in his life, draws on experience for his realism, slightly transforming events in his life. In this sense, the posthumous novel Islands in the Stream is in some places neither fictional nor fictitious. The Garden of Eden , however, a book brimming with the author’s vulnerability just as A Farewell to Arms is, treats intimate and delicate matters. It is a story told in the third person, as are all his major works. Thus we get to know the writer David Bourne, assuredly an explorer like Daniel Boone, on his adventurous Mediterranean honeymoon.

The anti-hero’s wife in The Garden of Eden, Catherine Bourne, is one of the most persuasive and lively heroines in Hemingway’s works. She is depicted with fascination and fear, like Marcel Proust’s Albertine and, at least in name, she reminds us of the strong and attractive Catherine Barkley (alias the seven-year-older Agnes Von Kurowsky), the Red Cross heroine in A Farewell to Arms. The former character is much more complex and difficult to define, however, and her ardor and the fire of marital love prove consuming and transmogrifying.

Living at the Grau (“canal”) du Roi, on the shores of the stream that runs from Aigues-Mortes straight down to the sea, the newly wedded couple in The Garden of Eden live in a borderland where “water” and “death” are key words, and where connotations like L’eau du Léthe present themselves: Eros and Thanatos, love and death, paradise and trespass.

In this innocent borderland, moral limits are immediately extended, and conventional roles are reversed. Sipping his post-coital fine à l’eau in the afternoon, David Bourne feels relieved of all the problems he had before his marriage, and has no thought of “writing nor anything but being with this girl,” who absorbs him and assumes command. Then the blond, sun-tanned Catherine appears with her hair “cropped as short as a boy’s,” declaring:

“now I am a boy … You see why it’s dangerous, don’t you? … Why do we have to go by everyone else’s rules? We’re us … Please understand and love me … I am Peter … You’re my beautiful lovely Catherine.”

From that moment the tables are turned. David-Catherine accepts and submits, and Catherine-Peter takes over the man’s role. She mounts him in bed at night, and penetrates him in conjugal bliss:

“He had shut his eyes and he could feel the long light weight of her on him … and then lay back in the dark and did not think at all and only felt the weight and the strangeness inside and she said: ‘Now you can’t tell who is who can you?”

Ernest Hemingway, 1901.

The father in the garden

Women with a gamin hairstyle, lovers who cut and dye their hair and change sexual roles, are themes that, with variations, occur in his novels from A Farewell to Arms, For Whom the Bell Tolls, to the posthumous Islands in the Stream. They culminate in The Garden of Eden. When writing The Garden of Eden he appeared as a redhead one day in May 1947. When asked about it, he said he had dyed his hair by mistake. In that novel, the search for complete unity between the lovers is carried to extremes. It may seem that the halves of the primordial Androgyne of the Platonic myth (once cut in two by Zeus and ever since longing to become a complete being again) are uniting here. Set in a fictional Paradise, a Biblical “Eden”, the novel is perhaps even more a story about expulsion, the loss of innocence, and the ensuing liberation, about knowledge acquired through the Fall, which is the basis of culture, about the ordeals and the high price an author must pay to become a writer worthy of his salt. Against a mythical background, the voice of Hemingway’s father is heard, challenging his son, as did the Father in the Biblical Garden. Slightly disguised, Hemingway’s dear father, who haunted his son’s life and work even after he had shot himself in 1928, remained an internalized critic until Ernest also took his life in 1961. Hemingway’s père pressed his ambivalent son to surpass himself and produce a distinct and lively multidimensional text, – “3 dimensions and if possible 4”:

“He found he knew much more about his father than when he had first written this story and he knew he could measure his progress by the small things which made his father more tactile and to have more dimensions than he had in the story before.”

After they had committed honeymoon adultery with the girl both spouses equally love passionately, David exclaims: “We’ve been burned out … Crazy woman burned out the Bournes.” This consuming and transforming fire of love and its subsequent trials and transgressions, in the end has a purging effect on the writer, who finally, as if emerging from a chrysalis stage, rises like the Phoenix from his bed and sits down in a regenerated mood to write in a perfect style:

“He got out his pencils and a new cahier, sharpened five pencils and began to write the story of his father and the raid in the year of the Maji-Maji rebellion … David wrote steadily and well and the sentences that he had made before came to him complete and entire and he put them down, corrected them, and cut them as if he were going over proof. Not a sentence was missing … He wrote on a while longer now and there was no sign that any of it would ever cease returning to him intact.”

Maji-Maji and Mau Mau

But why is Maji-Maji so important to the author when he has attained perfection?

When Tanzania gained independence in 1961-62, President Julius Nyerere proclaimed that the new republic was the fulfillment of the Maji-Maji dream. The Maji-Maji Rebellion had been a farmers’ revolt against colonial rule in German East Africa in 1905-1907. It began in the hill country southwest of Dar es-Salaam and spread rapidly until the insurrection was finally crushed after some 70,000 Africans had been killed. The farmers challenged the German militia fearlessly, crying “Maji! Maji!” when they attacked, believing themselves to be protected from bullets and death by “magic water”. Maji is Swahili for “water” – one of the key words in Hemingway’s novel.

The conviction and purposefulness of the Maji-Maji in The Garden of Eden, corresponds to the Kenyan Mau-Mau context of the novel True at First Light, which Hemingway started writing after his East African safari in 1953. Mau Mau was an insurrection of Kikuyo farm laborers in 1952. It was led by Jomo Kenyatta, who was subsequently held in prison until he became the premier of Kenya in 1963 (and the first President of the Republic in 1964). For Kikuyo men or women (and there were several women in the movement), to join Mau Mau meant dedicating their lives to a cause and sacrificing everything else, it meant taking a sacred oath that definitely cut them off from decorum and ordinary life.

In Hemingway’s vision, Maji-Maji and Mau Mau blend with his notion of the ideal committed writer, a man who is prepared to die for his art, and for art’s sake.

In the private library of Dag Hammarskjöld , who was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize after his death in the Congo (Africa) in 1961, the year Hemingway died, a copy of the beautiful original edition of A Farewell to Arms (Charles Scribner´s Sons, 1929) may still be seen (now in the Royal Library, Stockholm). In a way it is significant that the Secretary-General of the United Nations, who was dedicated to peacemaking, should have been a Hemingway reader.

* Anders Hallengren (1950-2024) was an associate professor of Comparative Literature and a research fellow in the Department of History of Literature and the History of Ideas at Stockholm University. He served as consulting editor for literature at Nobelprize.org. Dr. Hallengren was a fellow of The Hemingway Society (USA) and was on the Steering Committee for the 1993 Guilin ELT/Hemingway International Conference in the People’s Republic of China. Among his works in English are The Code of Concord: Emerson’s Search for Universal Laws; Gallery of Mirrors: Reflections of Swedenborgian Thought; and What is National Literature: Lectures on Emerson, Dostoevsky and Hemingway and the Meaning of Culture.

First published 28 August 2001

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Nobel prizes 2023.

Explore prizes and laureates

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

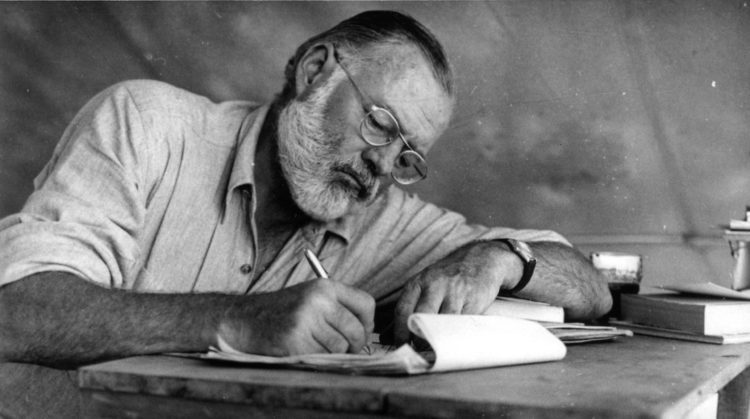

Ernest hemingway (1899–1961) and art.

Gertrude Stein

Pablo Picasso

Still Life with a Ginger Jar and Eggplants

Paul Cézanne

Plate 15 from "The Disasters of War" (Los Desastres de la Guerra): 'And there is no help' (Y no hai remedio)

Goya (Francisco de Goya y Lucientes)

Ernest Hemingway

Yousuf Karsh

The Harvesters

Pieter Bruegel the Elder

Colette Hemingway Independent Scholar

October 2004

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) ( 1986.1098.12 ), the author of many classic works, including In Our Time, The Sun Also Rises , A Farewell to Arms , Green Hills of Africa , For Whom the Bell Tolls , The Old Man and the Sea , and The Garden of Eden , was awarded the Nobel Prize in literature in 1954. During his early years in Paris in the 1920s, the American writer reached what some scholars consider his artistic maturity. New ways of expression and the exchange of ideas between writers, painters, dancers , and philosophers living in the city at this time nurtured the young author, leaving him with lasting impressions for his renowned short stories and novels.

Ernest and his first wife, Hadley, first came to Paris in 1921. Soon after their arrival, they became well acquainted with the other writers and many of the great masters of twentieth-century painting, among them Miró, Masson, Gris, and Picasso , with whom they shared the scene of excitement and budding accomplishment. Gertrude Stein ( 47.106 ), who was also living and writing in Paris at this time, was a close friend of Hemingway and a collector of contemporary art. Stein urged the young American writer to study the art that abounded in the city.

In 1925, Ernest and Hadley purchased Joan Miró’s painting The Farm (1921–22), now in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. A few years later, Hemingway wrote an article for Cahiers d’Art about his purchase of the painting and the impact of Miró’s composition on him. This marked the beginning of the writer’s lifelong admiration for and friendship with a number of European and American painters. In 1931, Hemingway and his second wife, Pauline Pfeiffer, purchased The Guitar Player (1926) and The Bullfighter (1913), both by their friend Juan Gris. The latter work would be reproduced as the frontispiece for Hemingway’s treatise on bullfighting Death in the Afternoon (1932). Soon thereafter, Ernest and Pauline acquired a number of paintings by the French Surrealist André Masson, five of which are now in the Ernest Hemingway Collection at the John F. Kennedy Library, Boston.

Throughout his life, Hemingway visited art galleries and museums, some of his favorites being the Prado, the Louvre, the Accademia in Venice, the Art Institute of Chicago, and the Metropolitan Museum. Along with his appreciation of European art, he expressed admiration for Winslow Homer and owned works by the American painters Waldo Peirce and Henry Strater. Hemingway wrote commentaries on art and artists, and, in many of his works, referred to paintings by Bruegel ( 19.164 ), Bosch, Cézanne ( 61.101.4 ), Goya , Homer, and others. In his novel For Whom the Bell Tolls (1940), he gives excruciating accounts of the devastation suffered on both sides during the Spanish Civil War, with many of his passages reading very much like the images depicted by Goya in his series of etchings ( 32.62.17 ) titled The Disasters of War (1810–23). In other works, Hemingway comments on Cézanne’s style and way of interpreting the world around him. The author remarked in one interview that he learned as much from painters about how to write as from writers. Painters and their works were integral to Hemingway’s learning to see, to hear, and to feel or not feel. They were part of the writer’s renowned ability to present an image hard, clear, and concentrated, using the language of ordinary speech without vague generalities, as true as a painter’s color.

Hemingway, Colette. “Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) and Art.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/hemw/hd_hemw.htm (October 2004)

Further Reading

Baker, Carlos. Hemingway, the Writer as Artist . 3d ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1963.

Hemingway, Ernest. A Moveable Feast . New York: Scribner, 1964.

Hornblower, Simon, and Antony Spawforth, eds. The Oxford Classical Dictionary . 3d ed., rev. New York: Oxford University Press, 2003.

Turner, Jane, ed. The Dictionary of Art . 34 vols. New York: Grove, 1996.

Watts, Emily Stipes. Ernest Hemingway and the Arts . Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1971.

Additional Essays by Colette Hemingway

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Greek Hydriai (Water Jars) and Their Artistic Decoration .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Hellenistic Jewelry .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Intellectual Pursuits of the Hellenistic Age .” (April 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Mycenaean Civilization .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Retrospective Styles in Greek and Roman Sculpture .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Africans in Ancient Greek Art .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art .” (July 2007)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Architecture in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Greek Gods and Religious Practices .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Art of Classical Greece (ca. 480–323 B.C.) .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Labors of Herakles .” (January 2008)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Athletics in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Rise of Macedon and the Conquests of Alexander the Great .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Technique of Bronze Statuary in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Women in Classical Greece .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Cyprus—Island of Copper .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Music in Ancient Greece .” (October 2001)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Etruscan Art .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Prehistoric Cypriot Art and Culture .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Sardis .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Medicine in Classical Antiquity .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Southern Italian Vase Painting .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Theater in Ancient Greece .” (October 2004)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ The Kithara in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Hemingway, Colette. “ Minoan Crete .” (October 2002)

Related Essays

- Pablo Picasso (1881–1973)

- School of Paris

- Anselm Kiefer (born 1945)

- Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment

- Frederic Remington (1861–1909)

- The Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburgs, 1400–1600

- Jean Antoine Houdon (1741–1828)

- Paul Cézanne (1839–1906)

- Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1525–1569)

- Winslow Homer (1836–1910)

List of Rulers

- List of Rulers of Europe

- Presidents of the United States of America

- France, 1900 A.D.–present

- The United States and Canada, 1900 A.D.–present

- 19th Century A.D.

- 20th Century A.D.

- American Literature / Poetry

- Floral Motif

- Installation Art

- Literature / Poetry

- Modern and Contemporary Art

- Printmaking

- Regionalism

- United States

Artist or Maker

- Bruegel, Pieter, the Elder

- Cézanne, Paul

- Homer, Winslow

- Karsh, Yousuf

- Picasso, Pablo

Online Features

- Connections: “Hemingway” by Seán Hemingway

- MetMedia: The Harvesters

- Nieman Foundation

- Fellowships

To promote and elevate the standards of journalism

Nieman News

Back to News

Notable Narratives

May 4, 2021, ernest hemingway's true and lasting writing lessons, a new documentary by ken burns and lynn novick explores the complexity of the man, and the legacy of his work.

By Dale Keiger

Tagged with

Ernest Hemingway Literary Hub