- About Grants

- How to Apply - Application Guide

Samples: Applications, Attachments, and Other Documents

As you learn about grantsmanship and write your own applications and progress reports, examples of how others presented their ideas can help. NIH also provides attachment format examples, sample language, and more resources below.

On This Page:

Sample Grant Applications

Nih formats, sample language, and other examples.

With the gracious permission of successful investigators, some NIH institutes have provided samples of funded applications, summary statements, and more. When referencing these examples, it is important to remember:

- The applications below used the form version and instructions that were in effect at the time of their submission. Forms and instructions change regularly. Read and carefully follow the instructions in your chosen funding opportunity and the Application Guide .

- The best way to present your science may differ substantially from the approaches used in these examples. Seek feedback on your draft application from mentors and others.

- Talk to an NIH program officer in your area of science for advice about which grant program would be a good fit for you and the Institute or Center that might be interested in your idea.

- Samples are not available for all grant programs. Because many programs have common elements, the available samples can still provide helpful information and demonstrate effective ways to present information.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID)

- Sample Applications and Summary Statements (R01, R03, R15, R21, R33, SBIR, STTR, K, F, G11, and U01)

- NIAID Sample Forms, Plans, Letters, Emails, and More

National Cancer Institute (NCI)

- Behavioral Research Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21)

- Cancer Epidemiology Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21, R37)

- Implementation Science Grant Applications (R01, R21, R37)

- Healthcare Delivery Research Grant Applications (R01, R03, R21, R50)

National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI)

- Ethical, Legal, and Social Implications (ELSI) Applications and Summary Statements (K99/R00, K01, R01, R03, and R21)

- NHGRI Sample Consent Forms

National Institute on Aging (NIA)

- K99/R00: Pathway to Independence Awards Sample Applications and summary statements

- NIA Small Business Sample Applications (SBIR and STTR Phase 1, Phase 2, and Fast-Track)

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD)

- Research Project Grants (R01) Sample Applications and Summary Statements

- Early Career Research (ECR) R21 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

- Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant (R21) Sample Applications and Summary Statements

NIH provides additional examples of completed forms, templates, plans, and other sample language for reference. Your chosen approach must follow the instructions in your funding opportunity and the How to Apply - Application Guide .

- Application Format Pages

- Annotated Form Sets

- Animal Document Samples from Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare (OLAW) for animal welfare assurances, study proposals, Memorandum of Understanding , and more

- Allowable Appendix Materials Examples

- Authentication of Key Biological and/or Chemical Resources Plan Examples

- Biosketch Format Pages, Instructions, and Samples

- Data Management and Sharing (DMS) Plan Samples

- Informed Consent Example for Certificates of Confidentiality

- Informed Consent Sample Language for secondary research with data and biospecimens and for genomic research

- Model Organism Sharing Plans

- Multiple PI Leadership Plan Examples

- Other Support format page, samples, and instructions

- Scientific Rigor Examples

- Person Months FAQ with example calculations

- Plain Language Examples for application title, abstract, and public health relevance statements

- Project Outcome Description Examples for interim or final Research Performance Progress Report (RPPR)

This page last updated on: June 10, 2024

- Bookmark & Share

- E-mail Updates

- Privacy Notice

- Accessibility

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), 9000 Rockville Pike, Bethesda, Maryland 20892

- NIH... Turning Discovery Into Health

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

Sample Grant Applications

On this page:

- Research Project Grants (R01): Sample Applications and Summary Statements

- Early Career Research (ECR) R21 Awards: Sample Applications and Summary Statements

Exploratory/Developmental Research Grant (R21) Awards: Sample Applications and Summary Statements

Preparing a stellar grant application is critical to securing research funding from NIDCD. On this page you will find examples of grant applications and summary statements from NIDCD investigators who have graciously shared their successful submissions to benefit the research community.

You can find more details about the NIDCD grants process from application to award on our How to Apply for a Grant, Research Training, or Career Development Funding page.

For more examples of applications for research grants, small business grants, training and career awards, and cooperative agreements, please visit Sample Applications & More on the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases website.

Always follow your funding opportunity’s specific instructions for application format. Although these samples demonstrate stellar grantsmanship, time has passed since these applications were submitted and the samples may not reflect changes in format or instructions.

The application text is copyrighted. You may use it only for nonprofit educational purposes provided the document remains unchanged and the researcher, the grantee organization, and NIDCD are all credited.

Section 508 compliance and accessibility: We have reformatted these sample applications to improve accessibility for people with disabilities and users of assistive technology. If you have trouble accessing the content, please contact the NIDCD web team .

Research Project Grants (R01): Sample Applications and Summary Statements

Investigator-initiated Research Project Grants (R01) make up the largest single category of support provided by NIDCD and NIH. The R01 is considered the traditional grant mechanism. These grants are awarded to organizations on behalf of an individual (a principal investigator, or PI) to facilitate pursuit of a research objective in the area of the investigator's research interests and competence.

Laurel H. Carney, Ph.D., University of Rochester

“Developing and testing models of the auditory system with and without hearing loss”

- Full Application (3.53MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (2.7MB PDF)

Leora R. Cherney, Ph.D., & Allen Walter Heinemann, Ph.D., Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago

"Defining trajectories of linguistic, cognitive-communicative and quality of life outcomes in aphasia"

- Full Application (5.59MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (336KB PDF)

Robert C. Froemke, Ph.D., New York University Grossman School of Medicine

“Synaptic basis of perceptual learning in primary auditory cortex”

- Full Application (5.3MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (608KB PDF)

Rene H. Gifford, Ph.D., & Stephen Mark Camarata, Ph.D., Vanderbilt University Medical Center

"Image-guided cochlear implant programming: Pediatric speech, language, and literacy"

- Full Application (9.63MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (485KB PDF)

Stavros Lomvardas, Ph.D., Columbia University Health Sciences

"Principles of zonal olfactory receptor gene expression"

- Full Application (6.37MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (183KB PDF)

Dan H. Sanes, Ph.D., New York University

“Social learning enhances auditory cortex sensitivity and task acquisition”

- Full Application (5.81MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (2.85MB PDF)

Christopher Shera, Ph.D., University of Southern California

"Understanding otoacoustic emissions"

- Full Application (6.9MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (447KB PDF)

Early Career Research (ECR) R21 Awards: Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The NIDCD Early Career Research (ECR) R21 Award supports both basic and clinical research from scientists who are beginning to establish an independent research career. The research must be focused on one or more of NIDCD's scientific mission areas . The NIDCD ECR Award R21 supports projects including secondary analysis of existing data; small, self-contained research projects; development of research methodology; translational research; outcomes research; and development of new research technology. The intent of the NIDCD ECR Award R21 is for the program director(s)/principal investigator(s) to obtain sufficient preliminary data for a subsequent R01 application.

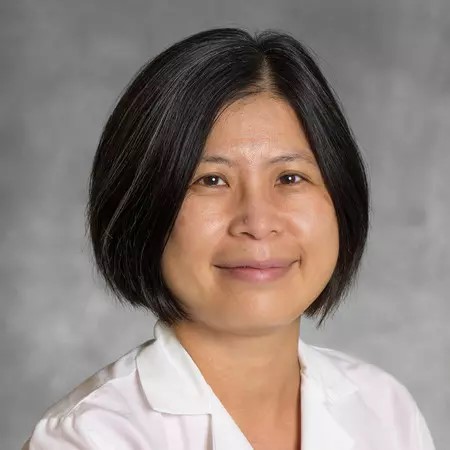

Ho Ming Chow, Ph.D., University of Delaware

“Neural markers of persistence and recovery from childhood stuttering: An fMRI study of continuous speech production”

- Full Application (7.64MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (736KB PDF)

Brian B. Monson, Ph.D., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

"Auditory experience during the prenatal and perinatal period"

- Full Application (3.74MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (525KB PDF)

Elizabeth A. Walker, Ph.D., University of Iowa

“Mechanisms of listening effort in school age children who are hard of hearing”

- Full Application (10.2MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (622KB PDF)

The NIH Exploratory/Developmental Research R21 grant mechanism encourages exploratory and developmental research by providing support for the early and conceptual stages of project development. NIH has standardized the Exploratory/Developmental Grant (R21) application characteristics, requirements, preparation, and review procedures in order to accommodate investigator-initiated (unsolicited) grant applications. Projects should be distinct from those supported through the traditional R01 mechanism. The NIH Grants & Funding website explains the scope of this program .

Taylor Abel, M.D., University of Pittsburgh, & Lori Holt, Ph.D., University of Texas at Austin

“Flexible representation of speech in the supratemporal plane”

- Full Application (11.5MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (1.01MB PDF)

Melissa L. Anderson, Ph.D., MSCI, UMass Chan Medical School

“Deaf ACCESS: Adapting Consent through Community Engagement and State-of-the-art Simulation”

- Full Application (1.34MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (354KB PDF)

Lynnette McCluskey, Ph.D., Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University

“Ace2 in the healthy and inflamed taste system”

- Full Application (6.05MB PDF)

Benjamin R. Munson, Ph.D., University of Minnesota

“Race, ethnicity, and speech intelligibility in normal hearing and hearing impairment”

- Full Application (1.35MB PDF)

- Summary Statement (378KB PDF)

(link is external) .

ANNOTATED SAMPLE GRANT PROPOSALS

How to Use Annotated Sample Grants

Are these real grants written by real students.

Yes! While each proposal represents a successfully funded application, there are two things to keep in mind: 1) The proposals below are final products; no student started out with a polished proposal. The proposal writing process requires stages of editing while a student formulates their project and works on best representing that project in writing. 2) The samples reflect a wide range of project types, but they are not exhaustive . URGs can be on any topic in any field, but all must make a successful argument for why their project should be done/can be done by the person proposing to do it. See our proposal writing guides for more advice. The best way to utilize these proposals is to pay attention to the proposal strengths and areas for improvement on each cover page to guide your reading.

How do I decide which sample grants to read?

When students first look through the database, they are usually compelled to read an example from their major (Therefore, we often hear complaints that there is not a sample proposal for every major). However, this is not the best approach because there can be many different kinds of methodologies within a single subject area, and similar research methods can be used across fields.

- Read through the Methodology Definitions and Proposal Features to identify which methodolog(ies) are most similar to your proposed project.

- Use the Annotated Sample Grant Database ( scroll below the definitions and features) filters or search for this methodology to identify relevant proposals and begin reading!

It does not matter whether the samples you read are summer grants (SURGs) or academic year grants (AYURGs). The main difference between the two grant types is that academic year proposals (AYURG) require a budget to explain how the $1,000 will be used towards research materials, while summer proposals (SURG) do not require a budget (the money is a living stipend that goes directly to the student awardee) and SURGs have a bigger project scope since they reflect a project that will take 8 weeks of full time research to complete. The overall format and style is the same across both grant cycles, so they are relevant examples for you to review, regardless of which grant cycle you are planning to apply.

How do I get my proposal to look like these sample grants?

Do not submit a first draft: These sample proposals went through multiple rounds of revisions with feedback from both Office of Undergraduate Research advisors and the student’s faculty mentor. First, it helps to learn about grant structure and proposal writing techniques before you get started. Then, when you begin drafting, it’s normal to make lots of changes as the grant evolves. You will learn a lot about your project during the editing and revision process, and you typically end up with a better project by working through several drafts of a proposal.

Work with an advisor: Students who work with an Office of Undergraduate Research Advisor have higher success rates than students who do not. We encourage students to meet with advisors well in advance of the deadline (and feel free to send us drafts of your proposal prior to our advising appointment, no matter how rough your draft is!), so we can help you polish and refine your proposal.

Review final proposal checklists prior to submission: the expectation is a two-page, single-spaced research grant proposal (1″ margins, Times New Roman 12 or Arial 11), and proposals that do not meet these formatting expectations will not be considered by the review committee. Your bibliography does not count towards this page limit.

Academic Year URG Submission Checklist

Summer URG Application Checklist

METHODOLOGY DEFINITIONS & PROPOSAL FEATURES

Research methodologies.

The proposed project involves collecting primary sources held in archives, a Special Collections library, or other repository. Archival sources might include manuscripts, documents, records, objects, sound and audiovisual materials, etc. If a student proposes a trip to collect such sources, the student should address a clear plan of what will be collected from which archives, and should address availability and access (ie these sources are not available online, and the student has permission to access the archive).

Computational/Mathematical Modeling

The proposed project involves developing models to numerically study the behavior of system(s), often through computer simulation. Students should specify what modeling tool they will be using (i.e., an off-the-shelf product, a lab-specific codebase), what experience they have with it, and what resources they have when they get stuck with the tool (especially if the advisor is not a modeler). Models often involve iterations of improvements, so much like a Design/Build project, the proposal should clearly define parameters for a “successful” model with indication of how the student will assess if the model meets these minimum qualifications.

Creative Output

The proposed project has a creative output such playwriting, play production, documentary, music composition, poetry, creative writing, or other art. Just like all other proposals, the project centers on an answerable question, and the student must show the question and method associated with the research and generation of that project. The artist also must justify their work and make an argument for why this art is needed and/or how it will add to important conversations .

Design/Build

The proposed project’s output centers around a final product or tool. The student clearly defines parameters for a “successful” project with indication of how they will assess if the product meets these minimum qualifications.

The project takes place in a lab or research group environment, though the methodology within the lab or research group vary widely by field. The project often fits within the larger goals/or project of the research group, but the proposal still has a clearly identified research question that the student is working independently to answer.

Literary/Composition Analysis

The project studies, evaluates, and interprets literature or composition. The methods are likely influenced by theory within the field of study. In the proposal, the student has clearly defined which pieces will be studied and will justify why these pieces were selected. Context will be given that provides a framework for how the pieces will be analyzed or interpreted.

Qualitative Data Analysis

The project proposes to analyze data from non-numeric information such as interview transcripts, notes, video and audio recordings, images, and text documents. The proposal clearly defines how the student will examine and interpret patterns and themes in the data and how this methodology will help to answer the defined research question.

Quantitative Data Analysis

The project proposes to analyze data from numeric sources. The proposal clearly defines variables to be compared and provides insight as to the kinds of statistical tests that will be used to evaluate the significance of the data.

The proposed project will collect data through survey(s). The proposal should clearly defined who will be asked to complete the survey, how these participants will be recruited, and/or proof of support from contacts. The proposal should include the survey(s) in an appendix. The proposal should articulate how the results from these survey(s) will be analyzed.

The proposed project will use theoretical frameworks within their proposed area of research to explain, predict, and/or challenge and extend existing knowledge. The conceptual framework serves as a lens through which the student will evaluate the research project and research question(s); it will likely contain a set of assumptions and concepts that form the basis of this lens.

Proposal Features

Group project.

A group project is proposed by two or more students; these proposals receive one additional page for each additional student beyond the two page maximum. Group projects must clearly articulate the unique role of each student researcher. While the uploaded grant proposal is the same, each student researcher must submit their own application into the system for the review.

International Travel

Projects may take place internationally. If the proposed country is not the student’s place of permanent residence, the student can additionally apply for funding to cover half the cost of an international plane ticket. Proposals with international travel should likely include travel itineraries and/or proof of support from in-country contacts in the appendix.

Non-English Language Proficiency

Projects may be conducted in a non-English language. If you have proficiency in the proposed language, you should include context (such as bilingual, heritage speaker, or by referencing coursework etc.) If you are not proficient and the project requires language proficiency, you should include a plan for translation or proof of contacts in the country who can support your research in English.

DATABASE OF ANNOTATED SAMPLE GRANTS

| Subject Area | Methodology | Proposal Feature | Review Committee |

|---|---|---|---|

| (608.19 KB) | Fieldwork; Interviews; Quantitative Data Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| (668.31 KB) | Computational/Mathematical Modeling | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (3.42 MB) | Creative output; Survey | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (473.84 KB) | Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (538.77 KB) | Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | ||

| (506.62 KB) | Qualitative Data Analysis; Quantitative Data Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| Computational/Mathematical Modeling; Design/Build | Natural Sciences & Engineering | ||

| (571.6 KB) | Design/Build; Survey | Group Project | Natural Sciences & Engineering |

| Creative Output; Literary/Composition Analysis | Non-English Language Proficiency | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (666.04 KB) | Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (1.24 MB) | Surveys; Interviews; Fieldwork; Qualitative Data Analysis | International Travel | Social Sciences & Journalism |

| (565.53 KB) | Interviews; Qualitative Data Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| Literary/Composition Analysis; Theory | Arts, Humanities & Performance | ||

| (596.44 KB) | Literary Analysis | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (545.94 KB) | Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (1.84 MB) | Archival; Literary/Compositional Analysis | International Travel; Non-English Language Competency | Arts, Humanities & Performance |

| Archival; Literary/Compositional Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | ||

| Archival; Literary/Composition Analysis | Arts, Humanities & Performance | ||

| Indigenous Methods; Creative Output; Interviews; Archival | Social Sciences & Journalism | ||

| Journalistic Output, Creative Output, Interviews | Social Sciences & Journalism | ||

| (1.1 MB) | Interviews; Creative Output; Journalistic Output | Group Project; International Travel; Non-English Language Proficiency | Social Sciences & Journalism |

| (475.41 KB) | Archival | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (606.53 KB) | Theory | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (830.19 KB) | Design/Build | Group Project | Natural Sciences & Engineering |

| (822.21 KB) | Creative Output | Group Project; | Arts, Humanities & Performance |

| (692.36 KB) | Literary/Compositional Analysis; Theory | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (1.17 MB) | Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (854.84 KB) | Literary/Composition Analysis; Theory | Arts, Humanities & Performance | |

| (597.87 KB) | Fieldwork; Lab-based | Natural Sciences & Engineering | |

| (549.81 KB) | Quantitative Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| (777.07 KB) | Survey; Quantitative Data Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| Creative Output | Arts, Humanities & Performance | ||

| (933.69 KB) | Interviews; Fieldwork | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| (468.76 KB) | Fieldwork; Quantitative Data Analysis | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| (828.69 KB) | Design/Build; Quantitative Data Analysis; Lab-based | Social Sciences & Journalism | |

| (555.08 KB) | Creative Output | Arts, Humanities & Performance |

Sample Applications & More

Several NIAID investigators have graciously agreed to share their exceptional applications and summary statements as samples to help the research community. Below the list of applications, you’ll also find example forms, sharing plans, letters, emails, and more. Find more guidance at NIAID’s Apply for a Grant .

Always follow your funding opportunity's instructions for application format. Although these applications demonstrate good grantsmanship, time has passed since these grant recipients applied. The samples may not reflect the latest format or rules. NIAID posts new samples periodically.

The text of these applications is copyrighted. Awardees provided express permission for NIAID to post these grant applications and summary statements for educational purposes. Awardees allow you to use the material (e.g., data, writing, graphics) they shared in these applications for nonprofit educational purposes only, provided the material remains unchanged and the principal investigators, awardee organizations, and NIH NIAID are credited.

Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) . NIAID is strongly committed to protecting the integrity and confidentiality of the peer review process. When NIH responds to FOIA requests for grant applications and summary statements, the material will be subject to FOIA exemptions and include substantial redactions. NIH must protect all confidential commercial or financial information, reviewer comments and deliberations, and personal privacy information.

Note on Section 508 Conformance and Accessibility. We have reformatted these samples to improve accessibility for people with disabilities and users of assistive technology. If you have trouble accessing the content, please contact the NIAID Office of Knowledge and Educational Resources at [email protected] .

Table of Contents

Find sample applications and summary statements below by type:

- Research grants. R01 , R03 , R15 , R21 , and R21/R33

- Small business grants. R41, R42, R43, and R44

- Training and career awards. K01 , K08 , K23 , and F31

- Extramural Associate Research Development Award. G11

- Cooperative agreements. U01

Find additional resources in the NIAID and NIH Sample Forms, Plans, Letters, Emails, and More section.

Research Grants

R01 sample applications and summary statements.

The R01 is the NIH standard independent research project grant. An R01 is meant to give you 4 or 5 years of support to complete a project, publish, and reapply before the grant ends. Read more at NIAID’s Comparing Popular Research Project Grants: R01, R03, and R21 .

R01 Samples Using Forms Version D

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Vernita Gordon, Ph.D., of the University of Texas at Austin “Assessing the roles of biofilm structure and mechanics in pathogenic, persistent infections” (Forms-D) | |

| Monica Gandhi, M.D., of the University of California, San Francisco “Hair Extensions: Using Hair Levels to Interpret Adherence, Effectiveness and Pharmacokinetics with Real-World Oral PrEP, the Vaginal Ring, and Injectables” (Forms-D) | |

| Tom Muir, Ph.D., of Princeton University "Peptide Autoinducers of Staphylococcal Pathogenicity" (Forms-D) | |

R01 Samples Using Forms Version C

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| William Faubion, Ph.D., of the Mayo Clinic Rochester “Inflammatory cascades disrupt Treg function through epigenetic mechanisms” (Forms-C) | |

| Chengwen Li, Ph.D., and Richard Samulski, Ph.D., of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill “Enhance AAV Liver Transduction with Capsid Immune Evasion” (Forms-C) | |

| Mengxi Jiang, Ph.D., of University of Alabama at Birmingham “Intersection of polyomavirus infection and host cellular responses” (Forms-C) | |

R03 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The small grant (R03) supports new research projects that can be carried out in a short period of time with limited resources. They are awarded for up to 2 years and are not renewable. R03s are not intended for new investigators. Read more at NIAID’s Comparing Popular Research Project Grants: R01, R03, and R21 .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Martin Karplus, Ph.D., of Harvard University "Modeling atomic structure of the EmrE multidrug pump to design inhibitor peptides" (Forms-B2) | |

| Chad A. Rappleye, Ph.D., of Ohio State University "Forward genetics-based discovery of Histoplasma virulence genes" (Forms-B2) | |

R15 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The Research Enhancement Award (R15) program supports small-scale research projects to expose students to research and strengthen the research environment at educational institutions that have not been major recipients of NIH support. They are awarded for up to 3 years.

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Artem Domashevskiy, Ph.D., of John Jay College of Criminal Justice “Development of a Novel Inhibitor of Ricin: A Potential Therapeutic Lead against Deadly Shiga and Related Toxins” (Forms-D) | |

| Rahul Raghavan, Ph.D., of Portland State University "Elucidating the evolution of Coxiella to uncover critical metabolic pathways" (Forms-D) | |

R21 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The R21 funds novel scientific ideas, model systems, tools, agents, targets, and technologies that have the potential to substantially advance biomedical research. R21s are not intended for new investigators, and there is no evidence that they provide a path to an independent research career. Read more at NIAID’s Comparing Popular Research Project Grants: R01, R03, and R21 .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Steven W. Dow, D.V.M., Ph.D., of Colorado State University, Fort Collins "Mechanisms of enteric infection" (Forms-B) | |

| Joseph M. McCune, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of California, San Francisco "Human immune system layering and the neonatal response to vaccines" (Forms-B) | |

| Peter John Myler, Ph.D., and Marilyn Parsons, Ph.D., of the Seattle Biomedical Research Institute "Ribosome profiling of " (Forms-B) | |

| Howard T. Petrie, Ph.D., of Scripps Florida "Lymphoid signals for stromal growth and organization in the thymus." (Forms-B) | |

| Michael N. Starnbach, Ph.D., of Harvard University Medical School "Alteration of host protein stability by Legionella" (Forms-B) | |

R21/R33 Sample Application and Summary Statement

The R21/R33 supports a two-phased award without a break in funding. It begins with the R21 phase for milestone-driven exploratory or feasibility studies with a possible transition to the R33 phase for expanded development. Transition to the second phase depends on several factors, including the achievement of negotiated milestones.

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Stephen Dewhurst, Ph.D., of the University of Rochester "The semen enhancer of HIV infection as a novel microbicide target" (Forms-B) | |

Small Business Grants

R41, r42, r43, and r44 – small business sample applications.

The SBIR (R43/R44) and STTR (R41/R42) programs support domestic small businesses to engage in research and development with the potential for commercialization. Read more about NIAID Small Business Programs .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Ronald Harty, Ph.D., of the University of Pennsylvania “Development of Small Molecule Therapeutics Targeting Hemorrhagic Fever Viruses” (STTR Phase II / R42, Forms-F) | |

| Iain James MacLeod, Ph.D., of Aldatu Biosciences, Inc. “PANDAA for universal, pan-lineage molecular detection of Lassa fever infection.” (SBIR Phase I / R43, Forms-E) | |

| Benjamin Delbert Brooks, Ph.D., of Wasatch Microfluidics “High-throughput, multiplexed characterization and modeling of antibody:antigen binding, with application to HSV” (SBIR Phase I / R43, Forms-D) | |

| Yingru Liu, Ph.D., of TherapyX, Inc. “Experimental Gonococcal Vaccine” (SBIR Phase II / R44, Forms-D) | |

| James Smith, Ph.D., of Sano Chemicals, Inc. “Lead Compound Discovery from Engineered Analogs of Occidiofungin” (STTR Phase I / R41, Forms-D) | |

| David H. Wagner, Ph.D., of OP-T-MUNE, Inc. “Developing a small peptide to control autoimmune inflammation in type 1 diabetes" (STTR Phase I / R41, Forms-D) | |

| Timothy C. Fong, Ph.D., of Cellerant Therapeutics, Inc. "Novel indication for myeloid progenitor use: Induction of tolerance" (STTR Phase I / R41, Forms-B2) | |

| Jose M. Galarza, Ph.D., of Technovax, Inc. "Broadly protective (universal) virus-like particle (VLP) based influenza vaccine" (SBIR Phase I / R43, Forms-B2) | |

| Michael J. Lochhead, Ph.D., of MBio Diagnostics, Inc. "Point-of-Care HIV Antigen/Antibody Diagnostic Device" (SBIR Phase II / R44, Forms-B2) | |

| Kenneth Coleman, Ph.D., of Arietis Corporation "Antibiotics for Recalcitrant Infection" (SBIR Fast-Track, Forms-B1) | |

| Patricia Garrett, Ph.D., of Immunetics, Inc. "Rapid Test for Recent HIV Infection" (SBIR Phase II / R44, Forms-B1) | |

| Raymond Houghton, Ph.D., of InBios International, and David AuCoin, Ph.D., of University of Nevada School of Medicine "Antigen Detection assay for the Diagnosis of Melioidosis" (STTR Phase II / R42, Forms-B1) | |

| Mark Poritz*, Ph.D., of BioFire Diagnostics, LLC. "Rapid, automated, detection of viral and bacterial pathogens causing meningitis" (SBIR Phase I / R43, Forms-B1) |

*Dr. Mark Poritz submitted the original grant application. In the course of the first year of funding, Dr. Andrew Hemmert took on increasing responsibility for the work. For the grant renewal, Dr. Poritz proposed that Dr. Hemmert replace him as the PI.

Training and Career Awards

K01 sample applications and summary statements.

The Research Scientist Development Award (K01) supports those with a research or health-professional doctoral degree and research development plans in epidemiology, computational modeling, or outcomes research. Read more about NIAID Research Career Development (K) Awards .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Jennifer M Ross, Ph.D., of the University of Washington “Modeling approaches to prioritize TB prevention among people with HIV in Uganda” (Forms-E) | |

| Lilliam Ambroggio, Ph.D., of the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center “Metabolomics Evaluation of the Etiology of Pneumonia” (Forms-D) | |

| Peter Rebeiro, Ph.D., of the Vanderbilt University Medical Center "The HIV Care Continuum and Health Policy: Changes through Context and Geography" (Forms-D) | |

K08 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The Mentored Clinical Scientist Research Career Development Award (K08) supports those with current work in biomedical or behavioral research, including translational research, a clinical doctoral degree such as M.D., D.V.M., or O.D., and a professional license to practice in the United States. Read more about NIAID Research Career Development (K) Awards .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Lenette Lu, M.D., Ph.D., of the Massachusetts General Hospital “Antibody Mediated Mechanisms of Immune Modulation in Tuberculosis” (Forms-D) | |

| Tuan Manh Tran, M.D., Ph.D., of the Indiana University-Purdue University at Indianapolis “Defining clinical and sterile immunity to infection using systems biology approaches” (Forms-D) | |

K23 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (K23) supports those with a clinical doctoral degree, who have the potential to develop into productive, clinical investigators, and who have made a commitment to focus their research endeavors on patient-oriented research. Read more about NIAID Research Career Development (K) Awards .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| DeAnna Friedman-Klabanoff, M.D., of University of Maryland, Baltimore “Serological markers of natural immunity to Plasmodium falciparum infection” (Forms-F) | |

F31 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

National Research Service Award (NRSA) individual fellowship (F31) grants provide research experience to predoctoral scientists. Read more about NIAID Fellowship Grants (F) .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Nicole Putnam, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University “The impact of innate immune recognition of Staphylococcus aureus on bone homeostasis and skeletal immunity” | |

| Nico Contreras, Ph.D., of University of Arizona "The Immunological Consequences of Mouse Cytomegalovirus on Adipose Tissue" | |

| Samantha Lynne Schwartz, Ph.D., of Emory University “Regulation of 2'-5'-oligoadenylate synthetase 1 (OAS1) by dsRNA” | |

G11 Sample Applications and Summary Statements

The Extramural Associate Research Development Award (EARDA) (G11) provides funds to institutions eligible to participate in the NIH Extramural Associates Program for establishing or enhancing an office of sponsored research and for other research infrastructure needs. Search for NIAID G11 Opportunities .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Oye Nana Akuffo, M.B.A., of the Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Legon “Capacity Building for Enhanced Research Administration (CaBERA- II) in Africa” (Forms-E) | |

| Andres Jaramillo Zuluaga, M.B.A., Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Medicas (CIDEIM) “Implementing Strategies for Building Capacity in Research Administration at CIDEIM, and Subsequent Dissemination Within Colombia and the Latin American Region” (Forms-E) | |

| Stella Kakeeto, M.B.A., Makerere University “Strengthening Makerere University's Research Administration Capacity for Efficient Management of NIH Grant Awards (SMAC)” (Forms-E) | |

U01 Sample Application and Summary Statement

The U01 research project cooperative agreement supports a discrete, specified, circumscribed project for investigators to perform in their areas of specific interest and competency. Learn more about NIAID Cooperative Agreements (U) .

| PI and Recipient Institution | Application Resources |

|---|---|

| Aaron Meyer, Ph.D., of the University of California, Los Angeles Falk Nimmerjahn, Ph.D., of Friedrich-Alexander University Erlangen-Nuremberg, Germany "Mapping the effector response space of antibody combinations" (Forms-E) | |

NIAID and NIH Sample Forms, Plans, Letters, Emails, and More

- Complex Model Organisms Sharing Plan

- Model Organisms Sharing Plan for Mice

- Simple Model Organisms Sharing Plan

- Sample Letter to Document Training in the Protection of Human Subjects

- Withdrawal of an Application Sample Form Letter

- Sample Just-in-Time Email From NIH

- Sample NIAID Request for Just-in-Time Information

- Preparing for a Foreign Organization System (FOS) Review

- Subaward Templates and Tools from the Federal Demonstration Partnership

- DMID Quality Management Guidance and Tools

- Sample Cancer Epidemiology Grant Applications

- Sample Behavioral Research Grant Applications

- Sample Implementation Science Research Applications

- K99/R00 Sample Applications

- Annotated SF 424 Grant Application Forms

- Biosketch Format Pages, Instructions and Samples

- Reference Letters

- Sample Data Tables for Training Grant Applications

- Additional Senior/Key Person Profile Format – for over 100 senior/key people

- Additional Performance Site Format – for over 300 performance sites

- Other Support Format Page

- Scientific Rigor Examples

- Authentication Plan Examples

- Sample Data Management and Sharing Plans

- Examples of Project Leadership Plans for Multiple PI Grant Applications

- Example calculations in the Usage of Person Months questions and answers

- Examples of Allowable Appendix Materials

- Sample Project Outcomes Description for RPPR

- Worksheet for Review of the Vertebrate Animal Section (VAS)

- Sample Animal Study Proposal

Have Questions?

A program officer in your area of science can give you application advice, NIAID's perspective on your research, and confirmation that your proposed research fits within NIAID’s mission.

Find contacts and instructions at When to Contact an NIAID Program Officer .

Successful Grant Proposal Examples: The Ultimate List for 2024

Reviewed by:

January 29, 2024

Table of Contents

Writing grant proposals can be a stressful process for many organizations. However, it's also an exciting time for your nonprofit to secure the funds needed to deliver or expand your services.

In this article, we'll dig into successful grant proposal examples to show how you can start winning grant funding for your organization.

By the time you finish reading this, you'll understand the characteristics of successful proposals, examples of grant proposals in a variety of program areas, and know exactly where you can find more sample grant proposals for nonprofit organizations .

Ready? Let's dig in!

Why Should You Find Successful Grant Proposal Examples?

Whether you are a seasoned grant writer or are preparing your first proposal ever, grant writing can be an intimidating endeavor. Grant writing is like any skill in that if you apply yourself, practice, and practice some more, you are sure to increase your ability to write compelling proposals.

Successful grant proposals not only convey the great idea you have for your organization but convince others to get excited about the future you envision. Many follow similar structures and developing a process that works best for your writing style can help make the task of preparing proposals much easier.

In addition to showing what to and not to do, finding successful grant proposals can help you see significant trends and structures that can help you develop your grant writing capabilities.

What Characteristics Make a Grant Proposal Successful?

"Grant writing is science, but it's not rocket science." - Meredith Noble

There's a lot that goes into creating a successful grant proposal. If you're feeling overwhelmed, Meredith Noble, grant writing expert, shares a straightforward step-by-step process to win funding.

1. Successful grant proposals have a clear focus.

Your first step when searching for funds is to clearly understand why you need those funds and what they will accomplish. Funders want to invest in programs they believe will be successful and impactful.

In your proposals, you want to instill confidence in your organization's commitment to the issue, dedication to the communities you serve, and capacity to fulfill the proposed grant activities.

Some questions that you may want to consider include:

- Are you looking for funds to establish a new program, launch a pilot project, or expand an existing program?

- Will your proposed program be finished in a year, or will it take multiple years to achieve your goal?

- Who is involved in your program, and who will benefit from its success?

- What problem will the proposed program address, and how is that solution unique?

- What are the specific, tangible goals that you hope to accomplish with the potential grant award?

Find Your Next Grant

17K Live Grants on Instrumentl

150+ Grants Added Weekly

2. Successful grant proposals are supported with relevant data.

Before starting your grant proposal, you want to take the time to do your research and make sure that your action plan is realistic and well-supported with data. By presenting yourself as capable and knowledgeable with reliable data, a thorough action plan, and a clear understanding of the subject matter.

It can also be beneficial to include data that your organization has collected to show program impacts and staff successes. Conduct regular analysis of program activities, grant deliverables, and collect success stories from clients and community members.

Some tips for when you collect your grant research :

- Make sure that you gather data from reputable sources. For example, at government sites such as Data.Census.gov , the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics for demographic data, or the U.S. Small Business, Explore Census Data Administration for industry analyses.

- Include diverse data. There may be some statistics where the numbers are enough to grab the reader's attention; other times, it may be helpful to have illustrations, graphs, or maps.

- In addition to quantitative data, qualitative data such as a story from an impacted community member may be extremely compelling.

- Make sure that the data you include is relevant. Throwing random numbers or statistics into the proposal does not make it impressive. All of the included data should directly support the main point of your proposal.

- You may find it useful to log important notes around what data you want to include in your grant proposal using a grant tracking tool such as Instrumentl .

By the way, check out our post on grant statistics after you finish this one!

3. Successful grant proposals are well-organized

Make sure to pay close attention to all of the requirements that a potential funder includes in their grant details and/or request for proposals (RFP). Your submission and all accompanying attachments, which may also include any graphs and illustrations, should adhere precisely to these guidelines.

Frequently the RFP or grant description will include directions for dividing and organizing your proposal. If, however, it does not, it is still best practice to break your proposal into clear sections with concise headings. You can include a table of contents with page numbers as well.

Standard grant proposal sections include:

- Proposal Summary: Also called the Executive Summary, this is a very brief statement (1-3 paragraphs) that explains your proposal and specifically states the amount of funding requested.

- Project Narrative: The bulk of your proposal, the Project Narrative, will do most of the work introducing your organization, the program, and describing your project. - Organization History: Who you are, what you do, where and how you do it. - Statement of the Problem: Background information on the problem and how it will be solved through the grant. - Project Description: Detailed explanation of the program you intend to implement with the grant, including a detailed timeline.

- Budget and Budget Justification: A breakdown of the project resources into specific budget categories, the amount allocated to each category, and appropriate reasons for that breakdown.

Want to get better at grants?

Get access to weekly advice and grant writing templates.

10k+ grant writers have already subscribed

Insights Straight To Your Inbox

4. successful grant proposals are tailored to the funder..

In addition to finding the basic details on the funding opportunity and application guidelines, you should also look into the funder, their giving priorities, and history.

Funders are much more likely to select your organization among others if they clearly understand and empathize with your cause and recognize the impact your work has in the community.

For more details on establishing meaningful relationships with funders, check out our article on How to Approach and Build Grant Funder Relationships .

The first step in determining whether a funding opportunity is a good fit, do some research to ensure your organization's programs and financial needs meet the funder’s interests and resources.

A few questions to ask include:

- What are the organization’s values, written mission, and goals?

- How is what you want to do aligned with the overall mission of this agency?

- Do their giving priorities match with the vision of your proposed program?

- Will this grant cover the entire cost of your program, or will you need to find additional funds?

- Does the grant timeline meet the budget needs of your organization?

- Are there other considerations that might be useful for us to know in preparing your application?

5. Successful grant proposals are proofread!

If you have been in the grant writing game for any extended period of time, chances are that you’ve dealt with tight deadlines. Nonprofit staff often have a lot on their plates, and if you happen to find an attractive funding opportunity when there’s only a handful of days before its deadline, it may be difficult to walk away.

It is crucial to plan an appropriate amount of time to review and proofread your proposal. Grammar mistakes can make or break your submission and they are easy to fix.

General strategies for editing your proposal include:

- Use one of the many available grammar-checking software such as Grammarly or GrammarCheck.me . These online tools are often free to use and can help you quickly and accurately review your work.

- Ask other members of your team to peer-review the proposal. It is especially important to have staff working on or who are directly impacted by the program proposed to ensure everyone is on the same page. Additionally, these staff members have the most information about the program's implementation and can catch inconsistency or unrealistic promises in the proposal.

- It is also helpful to ask someone unfamiliar with your program and the subject matter discussed in the proposal. Sometimes the grant reviewer may not have the same level of knowledge you or your staff have about the subject matter, and so you want to ensure you stay away from overly-specific jargon and undefined acronyms.

- Read through it (again!). A final read-through, maybe out loud, after all the edits have been made, can help you catch overlooked mistakes or inconsistencies in the proposal.

If you're looking to start building your own nonprofit financial statement and nonprofit membership application, get started quickly by using our Nonprofit Financial Statement Template and Nonprofit Membership Application Template . The template is made in Canva, an an easy-to-use creative design tool. You can jump right in, change colors, add your logo, and adjust the copy so it fits your brand.Why start from scratch when you can use one of our templates?

The Ultimate List of Grant Proposal Examples

As stated early on in the article, every grant proposal is unique. We have curated a list of sample grants for various types of projects or nonprofit organizations. This list is in no way exhaustive, but several examples cover common program designs and focus areas that receive philanthropic support through grants.

Research Grant Proposal Samples

Finding a grant opportunity to fund research can be a challenge. These types of grants are typically intensive and require in-depth expertise, a proposed research design, explanation of methodology, project timelines, and evidence of the principal investigator(s) qualifications.

The following are examples of grant proposals in support of research projects or studies.

Harvard University - Proposal to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (2009) :

Researchers at Harvard University proposed to research the “growth of policies in the United States around the use of genomic science in medicine and racial identity.”

For grants focused on research, it is important to ensure that the proposal can be understood by different kinds of stakeholders. While the research may be very specific and require some expertise to understand, the purpose and need for the research undertaken should be able to be understood by anyone.

For example, being cognizant of jargon and when it is and isn’t appropriate to use is incredibly important when developing a research grant proposal.

This proposal to the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, while very detailed and specific, still lays out the intent of the proposal in laymans terms and includes the appropriate amount of detail while ensuring that a broader audience can read and understand the request and purpose of the study.

Northwestern University - Annotated Grant Proposal Sample (2016)

For individuals or organizations who are interested in developing a great grant proposal in support of a research project, Northwestern University has a catalog of grant proposal samples with annotations denoting notable strengths and weaknesses of the application.

Linked above is one such example, a grant proposal in support of a project titled “Understanding the Stability of Barium-Containing Ceramic Glazes”. Review Northwestern University’s catalog of sample proposals here for additional guidance and inspiration.

Clinical Trial Grant Proposal Sample

Clinical trials are important research projects that test medical, behavioral, or surgical inventions to prove or disprove hypotheses about their efficacy. These trials are an important component of scientific and medical advancement. Oftentimes, hospitals or research institutions require robust funding from grants to initiate a trial of this kind.

While clinical trials are highly specific and require a great deal of expert input to develop, reviewing a grant proposal sample can help you prepare should your nonprofit organization decide to pursue a funding opportunity of this kind.

University of Alabama at Birmingham, Center for Clinical and Translational Science – NIH Grant R Series Samples :

If your nonprofit organization is seeking funding for a clinical trial, a great place to begin for tools and resources is the University of Alabama’s Center for Clinical and Translational Science.

The Center’s website has several sample proposals submitted to the National Institutes of Health . For professionals hoping to submit a grant proposal in support of a clinical trial, you may find one among these excellent examples that aligns closely with your work and can guide the grant development process.

Community Garden Grant Proposal Sample

Community gardens are idyllic cornerstones of their neighborhoods, cultivating lush, green spaces where residents can build a thriving community. Some community gardens are run by nonprofits such as land trusts or are born out of special projects initiated by nonprofit organizations.

Either way, to ensure the sustainability of local community gardens, gardeners and community garden managers may need to apply for funding through grant opportunities. Below is just one grant proposal sample in support of a community garden that may help you develop your own winning community garden grant application.

Stockton University – Community Garden 2020 Proposal :

This grant proposal submitted on behalf of Stockton University does an excellent job of illustrating the success of their community garden project and justifies the need for funding to sustain the momentum of the project going forward.

This proposal is also visually compelling and well-designed, incorporating photos and color schemes that directly evoke the image of a flourishing community garden. Ensuring your proposal document is easy to read and incorporates a strong layout and design can sometimes make or break an otherwise strong proposal that is being judged in a competitive pool of applicants. Strong design elements can set your proposal apart and make it shine!

Government Grant Proposal Samples

Government grants are some of the most complex and challenging funding opportunities that a person can come across. Funding from government entities is allocated from tax-payer dollars, and as such the government employs strict requirements and rigorous oversight over the grantmaking process.

Having a successful template or sample in hand can help position you for success when you need help applying for a government grant.

National Endowment for the Humanities - Challenge Grant Proposal Narrative Sample :

Developing a grant narrative is a challenge regardless of the opportunity. Government grants, which require very specific detail, can pose an even greater challenge than most opportunities. Linked here is a successfully funded project of the Alexandria Archive Institute, Inc . through a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).

This project is a great example of how to develop a grant narrative that successfully addresses the stringent requirements associated with grant proposals. Note how each section is laid out, the double spacing, citations, and other key elements that are required in a government proposal to adhere to specific standards.

Even though this is a great example, also be aware that every government agency is different and while this proposal was a successful application for the NEH, other agencies may have different requirements including specific narrative sections, attachments and work plans, among other key items.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) – City of Pleasantville Clean School Bus, Clean Snow Removal Trucks and Clean Bulldozers Project Proposal Sample :

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers an example grant for potential grantees to review. This sample proposal envisions a project by a local municipality to procure buses, snow removal trucks, and bulldozers that produce less emissions thereby decreasing air pollution in the region. This sample proposal is a great guide for developing a compelling narrative and weaving in evidence-based data and information to support throughout.

Conference Grant Proposal Sample

Conferences are an important aspect of a nonprofit or educational institution's operations. Conferences can help bring together like minded individuals across sectors to find solutions and sharpen their skills, and they can facilitate the formation of powerful coalitions and advocacy groups.

Identifying funding for conferences can be difficult, and requires a thoughtful, strategic approach to achieve success. Following a template or grant proposal sample can help guide you through the application process and strengthen your chances of submitting a successful application.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality – American Urological Associations Quality Improvement Summit :

This sample proposal provides an extensive template to follow for writing a successful conference grant proposal. The proposal follows an easily understood, structured narrative, and includes a detailed budget and key personnel profiles that will help anyone applying for grant support strengthen their chances of developing a high-quality application.

Dance Grant Proposal Sample

There are countless arts and cultural nonprofit organizations in the United States. According to Americans for the Arts , there are over 113,000 organizations (nonprofit or otherwise) devoted to promoting arts and culture in communities throughout the country—including dance.

Whether a theater that focuses on dance performance or a studio that teaches beginners how to appreciate the art form, there are a variety of dance-focused nonprofits that exist. Identifying strong grant proposal samples for dance-focused organizations or projects can be helpful as you work to help your dance program grow and gain revenue.

Mass Cultural Council – Dance/Theater Project Grant Sample :

This is an example proposal for an interactive dance/theatrical puppet project that focuses on engaging families. While this example captures a very unique and specific project, it also provides a good example of how to craft a case statement , write a strong project description, and develop a detailed project budget.

Daycare Grant Proposal Sample

In the United States, daycares are a vital component of childhood development, but unfortunately many families are unable to access them due to cost or accessibility. Studies show that in 2020 alone, over 57% of working families spent more than $10,000 on childcare while 51% U.S. residents live in regions classified as “childcare deserts”.

Given this, nonprofit daycares are vital to supporting future generations and providing accessible and affordable childcare for parents throughout the country. Many nonprofit daycares rely on generous funding through grants. Nonprofit day care professionals can use all the help they can get to submit winning proposals and sustain their daycare’s operations.

Relying on a high-quality grant proposal sample or template can be a huge help when working on a grant application or writing a proposal in support of a daycare.

AWE - Digital Learning Solutions – Grant Proposal Template :

While not a straightforward grant proposal sample, this grant template provides detailed guidance and helpful examples of how to respond to common questions and how to craft essential elements of a grant proposal focused on childcare and childhood development.

For example, the template provides easy to understand steps and bulleted lists for every key component of the grant proposal including a case statement, organizational capacity and information, project sustainability, project budget, and project evaluation.

Literacy Grant Proposal Sample

Promoting literacy is a very common mission for nonprofit organizations throughout the U.S. and the world. Literacy projects and programs are typically provided by educational institutions or education focused nonprofits.

In fact, according to the Urban Institute , Education focused nonprofits made up 17.2% of all public charities. With numbers like these, it can be helpful to gain insights from a grant proposal sample that will help you win grants and grow your organization.

Suburban Council of International Literacy (Reading) Association “Simply Reading” – Grant Proposal Sample :

This sample proposal to the Suburban Council of International Literacy (Reading) Association (SCIRA) is a great example of a strongly developed narrative that makes a powerful case for how fostering a love for reading among young students can result in improved educational outcomes. This helpful guide provides a framework for drafting a high-quality grant narrative while also giving examples of other key proposal elements such as a project budget.

Successful Educational Grant Proposals

Educational programming can be highly diverse in its delivery. Check out these examples of successful grant proposals for education to help you get started winning funds for your next educational program.

Kurzweil Educational Systems : In addition to this being a successful grant proposal, this example also includes detailed explanations of each section and provides useful guidelines that can help you frame your proposal.

Salem Education Foundation : This foundation has posted a sample application of a school seeking funding for increasing youth enrichment opportunities for their annual grant.

This is a great example for funding opportunities that ask specific questions about your organization and the proposed project instead of requesting a general proposal or narrative.

Successful Youth Grant Proposals

These examples of grant proposals for youth programs can help you tap into one of the largest categories of charitable dollars.

Family Service Association (FSA): This example of a grant proposal that is well-written and comprehensive. It is for a community block grant focused on youth development to expand services and cover staff salaries.

The Boys and Girls Club of America (BGCA): This is a sample produced by the national office of the BGCA to assist local branches in securing funds for youth programming and expanding services.

Successful Health-Related Grant Proposals

There is a large amount of funding for health-related initiatives, from healthcare grants to individuals, operational support for organizations or clinicians, and supporting researchers advancing the field. These sample grants give a bit of insight into this diverse sphere.

Centerville Community Center : Follow this link to read a grant to support community-based programming to raise awareness of cardiovascular disease prevention. This proposal does a great job of breaking down the project description, proposed activities, tracking measures, and timeline.

Prevention Plus Wellness : This is a sample grant proposal for nonprofit organizations to assist those looking to secure funds to address substance use and wellness programming for youth and young adults.

National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID): The NIAID has released several examples of proposal applications and scientific research grant proposal samples that successfully secured funding for scientific research related to healthcare.

Other Successful Grant Proposals

Of the over 1.6 million nonprofit organizations in the United States , your funding requests may fall out of the three general categories described above. We have included additional grants that may help meet your diverse needs.

Kennett Area Senior Center : Submitted to a local community foundation, this proposal requests funding between the range of $1,000 to $10,000 to provide critical services and assistance to local seniors.

In addition to being very detailed in describing the program details it also carefully describes the problem to be addressed.

Region 2 Arts Council: This comprehensive grant proposal requests funds to support an artist to continue expanding their skills and professional experience. This is a useful example for individual grants or scholarships for professional or scholastic opportunities in supported fields.

St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church: This is an excellent example of a faith-based organization’s proposal to secure funds for a capital project to repair their building. The framing of this proposal and the language in the narrative can be used to help shape proposal letters to individual donors and to foundations, which can be especially useful for faith-based organizations or other groups looking to secure funds.

Tips to Get More Successful Grant Proposal Examples

If you are interested in finding more grant proposal examples, especially those directly related to your organization's priorities and service area, you can look at a few places.

1st: Foundation Websites

Sometimes a foundation will include past proposal submissions publicly on the website. These are especially useful if you are seeking grants from the organization. You can see exactly what kind of proposals they found compelling enough to fund and see if there are any trends in their structure or language.

2nd: Online Tools and Workshops

Sites like the Community Tool Box or Non-Profit Guides offer free online resources for organizations working to support healthier communities and support social change. They provide helpful advice for new nonprofits and provide a whole suite of sample grants to help you start winning grants step by step.

You may also be able to ask other members of the Instrumentl community for their past successful grant proposals by attending our next live workshop. Hundreds of grant proposals attend these every few weeks. To RSVP, go here .

3rd: Collect your own!

As you start submitting grants, you are also creating a collection of sample grants tailored to your subject area. Every response offers an invaluable learning opportunity that can help you strengthen your grant writing skills.

Perhaps there are similarities among proposals that do exceptionally well. If a submission is rejected, ask for feedback or a score breakdown. Then, you may be able to see what areas need improvement for the future. Read our post on grant writing best practices for more on how to evaluate your past proposals.

Wrapping Things Up: Successful Grant Proposal Examples

Grant writing is a skill that anyone can learn. And as you begin to build your skills and prepare to write your next proposal, let these examples of successful grant proposals act as a guide to successful grant writing. Don’t however mistake a useful example as the ultimate guide to winning a grant for your organization.

Make sure to keep your unique mission, vision, and voice in the proposal!

Are you ready to get started?

Try Instrumentl free for 14-days now to start finding funders that fit your organization’s needs. Our unique matching algorithm will only show you active open grant opportunities that your nonprofit can apply for so you can start winning more grant funding.

Instrumentl's Tracker makes saving all your grant proposals to one place easy and encourages more collaboration across your team. To get started, click the button below.

Instrumentl team

Instrumentl is the all-in-one grant management tool for nonprofits and consultants who want to find and win more grants without the stress of juggling grant work through disparate tools and sticky notes.

Become a Stronger Grant Writer in Just 5 Minutes

17,502 open grants waiting for you.

Find grant opportunities to grow your nonprofit

10 Ready-to-Use Cold Email Templates That Break The Ice With Funders

Transform funder connections with our 10 expert-crafted cold email templates. Engage, build bonds, showcase impact, and elevate conversations effortlessly.

How to Save Up to 15 Hours per Week with Smarter Grant Tracking

Related posts, 5 mistakes you’re making with your grant writing – and what to do instead.

Grant writing can be complex, and even seasoned professionals make mistakes. In this article, we'll highlight five common errors and provide actionable solutions to improve your grant writing game.

How To Write A Grant Acceptance Letter: What Nonprofits Often Miss

Handwritten thank-you notes can make one feel genuinely appreciated. In cultivating funder relationships, communication is paramount. Crafting a gracious grant acceptance letter lays the foundation for a long-term relationship, potentially leading to sustainable funding. In this article, we'll guide you through crafting memorable and effective grant acceptance letters, empowering you to nurture relationships with your funders and build a robust network of support.

5 Tips For Using AI To Write Grants: 4 Experts Putting It To The Test

These days, it feels like Artificial Intelligence (AI) is everywhere. We spoke to four industry experts to learn how they are—or are not—using AI to support their grant-seeking efforts.

Try Instrumentl

The best tool for finding & organizing grants

128 reviews | High Performer status on g2.com

Grant Proposals (or Give me the money!)

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write and revise grant proposals for research funding in all academic disciplines (sciences, social sciences, humanities, and the arts). It’s targeted primarily to graduate students and faculty, although it will also be helpful to undergraduate students who are seeking funding for research (e.g. for a senior thesis).

The grant writing process

A grant proposal or application is a document or set of documents that is submitted to an organization with the explicit intent of securing funding for a research project. Grant writing varies widely across the disciplines, and research intended for epistemological purposes (philosophy or the arts) rests on very different assumptions than research intended for practical applications (medicine or social policy research). Nonetheless, this handout attempts to provide a general introduction to grant writing across the disciplines.

Before you begin writing your proposal, you need to know what kind of research you will be doing and why. You may have a topic or experiment in mind, but taking the time to define what your ultimate purpose is can be essential to convincing others to fund that project. Although some scholars in the humanities and arts may not have thought about their projects in terms of research design, hypotheses, research questions, or results, reviewers and funding agencies expect you to frame your project in these terms. You may also find that thinking about your project in these terms reveals new aspects of it to you.

Writing successful grant applications is a long process that begins with an idea. Although many people think of grant writing as a linear process (from idea to proposal to award), it is a circular process. Many people start by defining their research question or questions. What knowledge or information will be gained as a direct result of your project? Why is undertaking your research important in a broader sense? You will need to explicitly communicate this purpose to the committee reviewing your application. This is easier when you know what you plan to achieve before you begin the writing process.

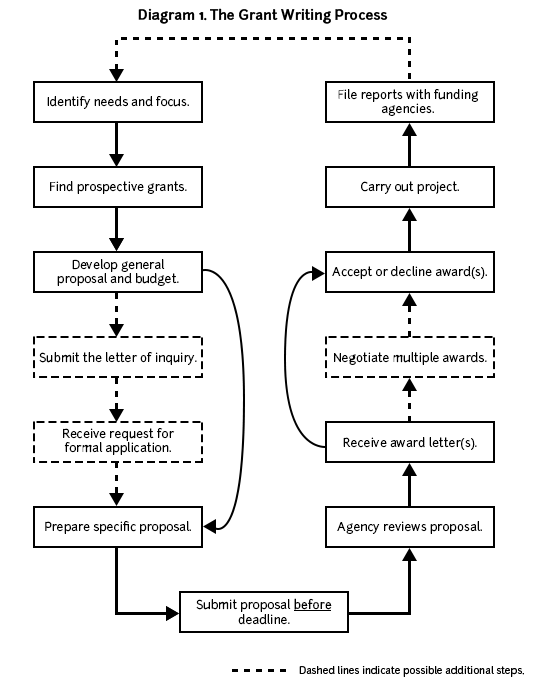

Diagram 1 below provides an overview of the grant writing process and may help you plan your proposal development.

Applicants must write grant proposals, submit them, receive notice of acceptance or rejection, and then revise their proposals. Unsuccessful grant applicants must revise and resubmit their proposals during the next funding cycle. Successful grant applications and the resulting research lead to ideas for further research and new grant proposals.

Cultivating an ongoing, positive relationship with funding agencies may lead to additional grants down the road. Thus, make sure you file progress reports and final reports in a timely and professional manner. Although some successful grant applicants may fear that funding agencies will reject future proposals because they’ve already received “enough” funding, the truth is that money follows money. Individuals or projects awarded grants in the past are more competitive and thus more likely to receive funding in the future.

Some general tips

- Begin early.

- Apply early and often.

- Don’t forget to include a cover letter with your application.

- Answer all questions. (Pre-empt all unstated questions.)

- If rejected, revise your proposal and apply again.

- Give them what they want. Follow the application guidelines exactly.

- Be explicit and specific.

- Be realistic in designing the project.

- Make explicit the connections between your research questions and objectives, your objectives and methods, your methods and results, and your results and dissemination plan.

- Follow the application guidelines exactly. (We have repeated this tip because it is very, very important.)

Before you start writing

Identify your needs and focus.

First, identify your needs. Answering the following questions may help you:

- Are you undertaking preliminary or pilot research in order to develop a full-blown research agenda?

- Are you seeking funding for dissertation research? Pre-dissertation research? Postdoctoral research? Archival research? Experimental research? Fieldwork?

- Are you seeking a stipend so that you can write a dissertation or book? Polish a manuscript?

- Do you want a fellowship in residence at an institution that will offer some programmatic support or other resources to enhance your project?

- Do you want funding for a large research project that will last for several years and involve multiple staff members?

Next, think about the focus of your research/project. Answering the following questions may help you narrow it down:

- What is the topic? Why is this topic important?

- What are the research questions that you’re trying to answer? What relevance do your research questions have?

- What are your hypotheses?

- What are your research methods?

- Why is your research/project important? What is its significance?

- Do you plan on using quantitative methods? Qualitative methods? Both?

- Will you be undertaking experimental research? Clinical research?

Once you have identified your needs and focus, you can begin looking for prospective grants and funding agencies.

Finding prospective grants and funding agencies

Whether your proposal receives funding will rely in large part on whether your purpose and goals closely match the priorities of granting agencies. Locating possible grantors is a time consuming task, but in the long run it will yield the greatest benefits. Even if you have the most appealing research proposal in the world, if you don’t send it to the right institutions, then you’re unlikely to receive funding.

There are many sources of information about granting agencies and grant programs. Most universities and many schools within universities have Offices of Research, whose primary purpose is to support faculty and students in grant-seeking endeavors. These offices usually have libraries or resource centers to help people find prospective grants.

At UNC, the Research at Carolina office coordinates research support.

The Funding Information Portal offers a collection of databases and proposal development guidance.

The UNC School of Medicine and School of Public Health each have their own Office of Research.

Writing your proposal

The majority of grant programs recruit academic reviewers with knowledge of the disciplines and/or program areas of the grant. Thus, when writing your grant proposals, assume that you are addressing a colleague who is knowledgeable in the general area, but who does not necessarily know the details about your research questions.

Remember that most readers are lazy and will not respond well to a poorly organized, poorly written, or confusing proposal. Be sure to give readers what they want. Follow all the guidelines for the particular grant you are applying for. This may require you to reframe your project in a different light or language. Reframing your project to fit a specific grant’s requirements is a legitimate and necessary part of the process unless it will fundamentally change your project’s goals or outcomes.