Latest Issue

The majestic cell

How the smallest units of life determine our health

Recent Issues

- Psychiatry’s new frontiers Hope amid crisis

- AI explodes Taking the pulse of artificial intelligence in medicine

- Health on a planet in crisis

- Real-world health How social factors make or break us

- Molecules of life Understanding the world within us

- All Articles

- The spice sellers’ secret

- ‘And yet, you try’

- Making sense of smell

- Before I go

- My favorite molecule

- View all Editors’ Picks

- Diversity, Equity & Inclusion

- Infectious Diseases

- View All Articles

Why Frankenstein matters

Frontiers in science, technology and medicine

By Audrey Shafer, MD

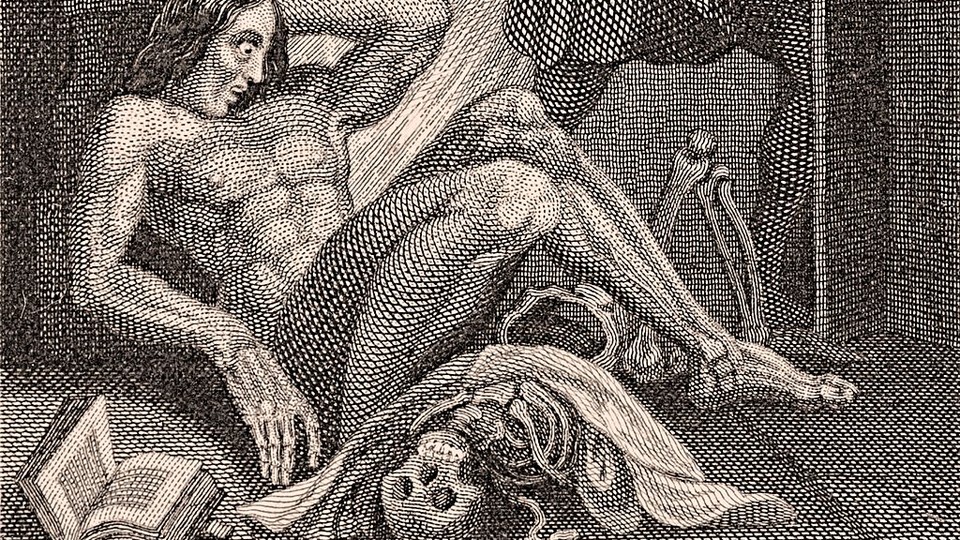

Illustration by Michael Waraksa

“Clear!” At some point during medical education and practice, every physician has heard or given this command. One person — such as a closely supervised medical student — pushes a button to deliver an electric shock and the patient’s body jerks. The code team, in complex choreography, works to restore both the patient’s cardiac rhythm and a pulse strong enough to perfuse vital organs.

After a successful defibrillation effort, team members do not have time to dwell on the line crossed from death to life. It is even difficult to focus on the ultimate goal: to enable the patient to leave the hospital intact, perhaps to grasp a grandchild’s — or grandparent’s — hand while crossing the street to the park.

Despite these dramatic hospital scenes, many scientists, doctors and patients balk at any mention of the words Frankenstein and medicine in the same breath. Because, unlike the Victor Frankenstein of Mary Shelley’s novel, the reanimators at a hospital code have not toiled alone in a garret; assembled body parts from slaughterhouses, dissecting rooms and charnel houses; or created an entirely new being. Nonetheless, in this bicentennial commemorative year of the book’s publication, it is not only germane, but important to consider the impact of this story, including our reactions to it, on the state of scientific research today.

Shelley’s Frankenstein has captured the imaginations of generations, even for those who have never read the tale written by a brilliant 18-year-old woman while on holiday with Lord Byron, Percy Bysshe Shelley and Dr. John Polidori amid extensive storms induced by volcanic ash during the so-called year without a summer. Mary Shelley (her name was Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin at the time) was intrigued by stories of science such as galvanism, which she would have heard through her father’s scientist (then called natural philosopher) friends.

With Frankenstein , Shelley wrote the first novel to forefront science as a means to create life, and as such, she wrote the first major work in the science fiction genre. Frankenstein, a flawed, obsessed student, feverishly reads extensive tomes and refines his experiments. After he succeeds in his labors, Frankenstein rejects his creation: He is revulsed by the sight of the “monster,” whom he describes as hideous. This rejection of the monster leads to a cascade of calamities. The subtitle of the book, The Modern Prometheus , primes the reader for the theme of the dire consequences of “playing God.”

A framework for examining morality and ethics

Frankenstein is not only the first creation story to use scientific experimentation as its method, but it also presents a framework for narratively examining the morality and ethics of the experiment and experimenter. While artistic derivations, such as films and performances, and literary references have germinated from the book for the past 200 years, the current explosion of references to Frankenstein in relation to ethics, science and technology deserves scrutiny.

Science is, by its very nature, an exploration of new frontiers, a means to discover and test new ideas, and an impetus for paradigm shifts. Science is equated with progress and with advances in knowledge and understanding of our world and ourselves. Although a basic tenet of science is to question, there is an underlying belief, embedded in words like “advances” and “progress,” that science will better our lives.

Safeguards, protocols and institution approvals by committees educated in the horrible and numerous examples of unethical experiments done in the name of science are used to prevent a lone wolf like Victor Frankenstein from undertaking his garret experiments. Indeed, it is amusing to think of a mock Institutional Review Board approval process for a proposal he might put forward.

But these protections can go only so far. It is impossible to predict all of the consequences of our current and future scientific and technologic advances. We do not even need to speculate on the potential repercussions of, for example, the creation of a laboratory-designed self-replicating species, as we can look to unintended consequences of therapies such as the drug thalidomide, and controversies over certain gene therapies. This tension, this acknowledgment that unintended consequences occur, is unsettling.

Science and technology have led to impressive improvements in health and health care. People I love are alive today because of cancer treatments unknown decades ago. We are incredibly grateful to the medical scientists who envisioned these drugs and who did the experiments to prove their effectiveness.

As an anesthesiologist, I care for patients at vulnerable times in their lives; I use science and technology to render them unconscious — and to enable them to emerge from an anesthetized state.

But, as the frontiers are pushed further and further, the unintended consequences of how science and technology are used could affect who we are as humans, the viability of our planet and how society evolves. In terms of health, medicine and bioengineering, Frankenstein resonates far beyond defibrillation. These resonances include genetic engineering, tissue engineering, transplantation, transfusion, artificial intelligence, robotics, bioelectronics, virtual reality, cryonics, synthetic biology and neural networks. These fields are fascinating, worthy areas of exploration.

‘Frankenstein’ is not only the first creation story to use scientific experimentation as its method, but it also presents a framework for narratively examining the morality and ethics of the experiment and experimenter.

We, as physicians, health care providers, scientists and people who deeply value what life and health mean, cannot shy away from discussions of the potential implications of science, technology and the social contexts which give new capabilities and interventions even greater complexity. Not much is clear, but that makes the discussion more imperative.

Even the call “Clear!” and the ritual removal of physical contact with a patient just about to receive a shock is not so “clear,” as researchers scrutinize whether interruptions to chest compressions are necessary for occupational safety — that is, it may be deemed safe in the future for shocks and manual compressions to occur simultaneously.

We need to discuss the big questions surrounding what is human, and the implications of those questions. What do we think about the possibility of sentient nonhumans, enhanced beyond our limits, more sapient than Homo sapiens? Who or what will our great-grandchildren be competing against to gain entrance to medical school?

Studying and discussing works of art and imagination such as Frankenstein , and exchanging ideas and perspectives with those whose expertise lies outside the clinic and laboratory, such as artists, humanists and social scientists, can contribute not just to an awareness of our histories and cultures, but also can help us probe, examine and discover our understanding of what it means to be human. That much is clear.

Audrey Shafer, MD

Audrey Shafer, MD, is a Stanford professor of anesthesiology, perioperative and pain medicine, the director of the Medicine and the Muse program and the co-director of the Biomedical Ethics and Medical Humanities Scholarly Concentration. She is an anesthesiologist at the Veterans Affairs Palo Alto Health Care System.

Email the author

The Ethical Interest of Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus : A Literature Review 200 Years After Its Publication

- Original Research/Scholarship

- Published: 12 June 2020

- Volume 26 , pages 2791–2808, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Irene Cambra-Badii ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1233-3243 1 , 2 ,

- Elena Guardiola ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8002-1415 3 &

- Josep-E. Baños ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8202-6893 1 , 3

3403 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

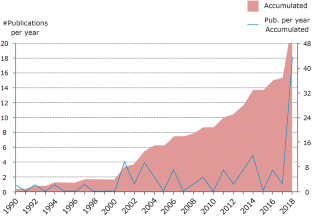

Two hundred years after it was first published, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus remains relevant. This novel has endured because of its literary merits and because its themes lend themselves to analysis from multiple viewpoints. Scholars from many disciplines have examined this work in relation to controversial scientific research. In this paper, we review the academic literature where Frankenstein is used to discuss ethics, bioethics, science, technology and medicine. We searched the academic literature and carried out a content analysis of articles discussing the novel and films derived from it, analyzing the findings qualitatively and quantitatively. We recorded the following variables: year and language of publication, whether it referred to the novel or to a film, the academic discipline in which it was published, and the topics addressed in the analysis. Our findings indicate that the scientific literature on Frankenstein focuses mainly on science and the personality of the scientist rather than on the creature the scientist created or ethical aspects of his research. The scientist’s responsibility is central to the ethical interest of Frankenstein; this issue entails both the motivation underlying the scientist’s acts and the consequences of these acts.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Scheme based on: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 2009;7:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed1000097

Similar content being viewed by others

- Frankenstein

The Perfect Organism: The Intruder of the Alien Films as a Bio-fictional Construct

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

Banerjee, S. (2011). Home is where mamma is: Reframing the science question in Frankenstein. Women's Studies . https://doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2011.527783 .

Article Google Scholar

Barns, I. (1990). Monstrous nature or technology?: Cinematic resolutions of the “Frankenstein Problem”. Science as Culture . https://doi.org/10.1080/09505439009526278 .

Bell, R., & Lederman, N. (2003). Understandings of the nature of science and decision making on science and technology based issues. Science Education . https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10063 .

Bishop, M. (1994). The “making” and re-making of man: 1. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and transplant surgery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 87 (12), 749–751.

Google Scholar

Brem, S., & Anijar, K. (2003). The bioethics of fiction: The chimera in film and print. American Journal of Bioethics . https://doi.org/10.1162/15265160360706787 .

Burgess, M. (2014). Transporting Frankenstein: Mary Shelley's mobile figures. European Romantic Review . https://doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2014.902902 .

Campbell, C. (2003). Biotechnology and the fear of Frankenstein. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0963180103124048 .

Chambers, T. (2018). On cute monkeys and repulsive monsters. Hastings Center Report . https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.930 .

Childress, J. F., & Beauchamp, T. L. (2001). Principles of biomedical ethics . New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, J. (2018). How a horror story haunts science. Science . https://doi.org/10.1126/science.359.6372.148 .

Davies, H. (2004). Can Mary Shelley's Frankenstein be read as an early research ethics text? Medical Humanities . https://doi.org/10.1136/jmh.2003.000153 .

de La Rocque, L., & Texeira, L. A. (2001). Frankenstein, de Mary Shelley, e Drácula, de Bram Stoker: gênero e ciência na Literature. História, Ciências, Saúde—Manguinhos . https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-59702001000200001 .

Djerassi, C. (1998). Ethical discourse by science-in-fiction. Nature . https://doi.org/10.1038/31088 .

Doherty, S. (2003). The 'medicine' of Shelley and Frankenstein. Emergency Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1442-2026.2003.00483.x .

Fairclough, M. (2018). Frankenstein and the “Spark of Being”: Electricity, animation, and adaptation. European Romantic Review . https://doi.org/10.1080/10509585.2018.1465701 .

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014). Use of content analysis to conduct knowledge-building and theory-generating qualitative systematic reviews. Qualitative Research . https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794113481790 .

Fischer, J. (2014). What kind of ethics?—How understanding the field affects the role of empirical research on morality for ethics. In M. Christen, C. van Schaik, J. Fischer, M. Huppenbauer, & C. Tanner (Eds.), Empirically informed ethics: Morality between facts and norms. Library of ethics and applied philosophy (Vol. 32). New York: Springer.

Gaylin, W. (1977). The Frankenstein Factor. The New England Journal of Medicine, 297 , 665–667.

Genís Mas, D. (2016). The sleep of (scientific) reason produces (literary) monsters or, how science and literature shake hands. Mètode, 6 , 14–20.

Ginn, S. (2013). Mary Shelley's Frankenstein: Exploring neuroscience, nature, and nurture in the novel and the films. Progress in Brain Research . https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63287-6.00009-9 .

Goswami, D. (2018). “Filthy creation”: The problem of parenting in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities . https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v10n2.20 .

Goulding, C. (2002). The real Doctor Frankenstein? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1177/014107680209500514 .

Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B.-M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002 .

Greenshields, W. (2018). Frames, vanishing points and blindness: Frankenstein and the field of vision. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities . https://doi.org/10.21659/rupkatha.v10n2.18 .

Hammond, K. (2004). Monsters of modernity: Frankenstein and modern environmentalism. Cultural Geographies . https://doi.org/10.1191/14744744004eu301oa .

Harrison, G., & Gannon, W. (2014). Victor Frankenstein's Institutional Review Board Proposal, 1790. Science and Engineering Ethics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-014-9588-y .

Haste, H. (1997). Myths, monsters, and morality: Understanding 'antiscience' and the media message. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 22 (2), 114–120.

Haynes, R. (2003). From alchemy to artificial intelligence: Stereotypes of the scientist in western literature. Public Understanding of Science . https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662503123003 .

Haynes, R. (2014). Whatever happened to the “mad, bad” scientist? Overturning the stereotype. Public Understanding of Science . https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662514535689 .

Hellsten, I. (2000). Dolly: Scientific breakthrough or Frankenstein's Monster? Journalistic and Scientific Metaphors of Cloning. Metaphor and Symbol . https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327868MS1504_3 .

Holmes, R. (2016). Science fiction: The science that fed Frankenstein. Nature . https://doi.org/10.1038/535490a .

Jochemsen, H. (2006). Normative practices as an intermediate between theoretical ethics and morality. Philosophia Reformata . https://doi.org/10.1163/22116117-90000377 .

Kakoudaki, D. (2018). Unmaking people: The politics of negation in Frankenstein and Ex Machina. Science Fiction Studies . https://doi.org/10.5621/sciefictstud.45.2.0289 .

Koepke, Y. (2018). Lessons from Frankenstein: narrative myth as ethical model. Medical Humanities . https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2017-011376 .

Koren, P., & Bar, V. (2009). Science and it’s images—Promise and threat: From classic literature to contemporary students’ images of science and “the Scientist”. Interchange . https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-009-9088-1 .

Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis. An introduction to its methodology . London: Sage.

Lacefield, K. (2016). Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the Guillotine, and Modern Ontological Anxiety. Text Matters . https://doi.org/10.1515/texmat-2016-0003 .

Laplace-Sinatra, M. (1998). Science, gender and otherness in Shelley's Frankenstein and Kenneth Branagh's film adaptation. European Romantic Review . https://doi.org/10.1080/10509589808570051 .

Lederman, N. (1992). Students' and teachers' conceptions of the nature of science: A review of the research. Journal of research in science teaching . https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.3660290404 .

Mackowiak, P. (2014). President's address: Mary Shelley, Frankenstein, and the dark side of medical science. Transactions of the American Clinical and Climatological Association, 125 , 1–13.

Mccurdy, H. (2006). Vision and leadership: The view from science fiction. Public Integrity, 8 (3), 257–270.

Mellor, A. (2001). Frankenstein, racial science, and the yellow peril. Ninet Century Contexts . https://doi.org/10.1080/08905490108583531 .

Micheletti, S. (2018). Hybrids of the romantic: Frankenstein, olimpia, and artificial life. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte . https://doi.org/10.1002/bewi.201801888 .

Miller, G., & McFarlane, A. (2016). Science fiction and the medical humanities. Medical Humanities . https://doi.org/10.1136/medhum-2016-011144 .

Mitra, Z. (2011). A science fiction in a gothic scaffold: A reading of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, 3 (1), 52–59.

Moreno, J. (2018). From Frankenstein to Hawking: Which is the real face of science? The American Journal of Bioethics . https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2018.1461468 .

Nagy, P., Wylie, R., Eschrich, J., & Finn, E. (2018a). Why Frankenstein is a stigma among scientists. Science and Engineering Ethics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9936-9 .

Nagy, P., Wylie, R., Eschrich, J., & Finn, E. (2018b). The enduring influence of a dangerous narrative: How scientists can mitigate the Frankenstein myth. The Journal of Bioethical Inquiry . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-018-9846-9 .

Nowlin, C. (2018). 200 years after Frankenstein. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2018.0054 .

Oakes, E. (2013). Lab life: Vitalism, Promethean Science, and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein. Logos: A Journal of Catholic Thought and Culture, 16 (4), 56–77.

O'Neill, R. (2006). “Frankenstein to futurism”: Representations of organ donation and transplantation in popular culture. Transplantation Reviews . https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trre.2006.09.002 .

Pheasant-Kelly, F. (2018). Reflections of Science and Medicine in Two Frankenstein Adaptations: Frankenstein (Whale 1931) and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (Branagh 1994). Literature and Medicine . https://doi.org/10.1353/lm.2018.0016 .

Prinz, J. J. (2014). Where do morals come from?—A plea for a cultural approach. In M. Christen, C. van Schaik, J. Fischer, M. Huppenbauer, & C. Tanner (Eds.), Empirically informed ethics: Morality between facts and norms. Library of ethics and applied philosophy (Vol. 32). New York: Springer.

Pulido Tirado, G. (2012). Vida artificial y literatura: Mito, leyendas y ciencia en el Frankenstein de Mary Shelley. Tonos digital: Revista electrónica de estudios filológicos, 23 , 1–17.

Reginato, V., Claramonte Gallian, D. M., & Marra, S. (2018). A Literature na formação de futuros cientistas: Lição de Frankenstein. Educacao e Pesquisa . https://doi.org/10.1590/S1517-9702201610157176 .

Reich, W. T. (1978). Encyclopedia of bioethics . New York: Free Press.

Robert, J. S. (2018). Rereading Frankenstein : What if Victor Frankenstein had actually been evil? Hastings Center Report . https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.933 .

Sariols Persson, D. (2011). L'enfant monstre, le monstre enfant. Enfances et Psy . https://doi.org/10.3917/ep.051.0025 .

Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice . London: Sage.

Schroll, M., & Greenword, S. (2011). Worldviews in collision/worldviews in metamorphosis: Toward a multistate paradigm. Anthropology of Consciousness . https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-3537.2011.01037.x .

Severino, S., & Morrison, N. (2013). Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley's Frankenstein, or the modern Prometheus: A psychological study of unrepaired shame. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: Advancing Theory and Professional Practice through Scholarly and Reflective Publications . https://doi.org/10.1177/154230501306700405 .

Stern, M. (2006). Dystopian anxieties versus utopian ideals: Medicine from Frankenstein to the visible human project and body worlds. Science as Culture . https://doi.org/10.1080/09505430500529748 .

Syrdal, D. S., Nomura, T., Hirai, H., & Dautenhahn, K. (2011). Examining the Frankenstein Syndrome. In B. Mutlu, C. Bartneck, J. Ham, V. Evers, & T. Kanda (Eds.), Social robotics. ICSR 2011. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 7072). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-25504-5_13 .

Szollosy, M. (2017). Freud, Frankenstein and our fear of robots: Projection in our cultural perception of technology. AI and Society . https://doi.org/10.1007/s00146-016-0654-7 .

Trichet, Y., & Marion, E. (2014). Le corps, son image et le désir du scientifique dans la fiction cinématographique. Cliniques Mediterraneennes . https://doi.org/10.3917/cm.090.0255 .

Turney, J. (1998). Frankenstein’s footsteps: Science, genetics, and popular culture . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

van den Belt, H. (2009). Playing God in Frankenstein’s footsteps: Synthetic biology and the meaning of life. Nanoethics . https://doi.org/10.1007/s11569-009-0079-6 .

van den Belt, H. (2018). Frankenstein lives on. Science . https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aas9167 .

Villacañas, B. (2001). De doctores y monstruos: la ciencia como transgresión en Dr. Faustus, Frankestein y Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Asclepio, 5 , 10. https://doi.org/10.3989/asclepio.2001.v53.i1.177 .

Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis . Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Book Google Scholar

Westra, L. (1992). Response: Dr. Frankenstein and today's professional biotechnologist: a failed analogy? Between Species, 8 (4), 216–223.

Williams, C. (2001). “Inhumanly brought back to life and misery”: Mary Wollstonecraft, Frankenstein, and the Royal Humane Society. Women’s Writing . https://doi.org/10.1080/09699080100200190 .

Download references

The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain

Irene Cambra-Badii & Josep-E. Baños

Bioethics Chair, Universitat de Vic–Universitat Central de Catalunya, Vic, Spain

Irene Cambra-Badii

School of Medicine, Universitat de Vic–Universitat Central de Catalunya, Casa de Convalescència, Dr. Junyent 1, 08500, Vic, Spain

Elena Guardiola & Josep-E. Baños

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Josep-E. Baños .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cambra-Badii, I., Guardiola, E. & Baños, JE. The Ethical Interest of Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus : A Literature Review 200 Years After Its Publication. Sci Eng Ethics 26 , 2791–2808 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00229-x

Download citation

Received : 14 October 2019

Accepted : 30 May 2020

Published : 12 June 2020

Issue Date : October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-020-00229-x

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Literature analysis

- Feature films

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 30, Issue 1

- Can Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein be read as an early research ethics text?

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Correspondence to: H Davies 40 Avenell Road, London N5 1DP, UK; hugh.daviescorec.org.uk

The current, popular view of the novel Frankenstein is that it describes the horrors consequent upon scientific experimentation; the pursuit of science leading inevitably to tragedy. In reality the importance of the book is far from this. Although the evil and tragedy resulting from one medical experiment are its theme, a critical and fair reading finds a more balanced view that includes science’s potential to improve the human condition and reasons why such an experiment went awry. The author argues that Frankenstein is an early and balanced text on the ethics of research upon human subjects and that it provides insights that are as valid today as when the novel was written. As a narrative it provides a gripping story that merits careful analysis by those involved in medical research and its ethical review, and it is more enjoyable than many current textbooks! To support this thesis, the author will place the book in historical, scientific context, analyse it for lessons relevant to those involved in research ethics today, and then draw conclusions.

- GAfREC, Governance Arrangements for Research Ethics Committees

- IRB, institutional review board

- REC, research ethics committee

- Frankenstein

- scientific experimentation

- research ethics

https://doi.org/10.1136/jmh.2003.000153

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

↵ Page numbers after quotations in the novel are those in the Penguin Classic edition.

Linked Articles

- Letter Can Frankenstein be read as an early research ethics text? I Bamforth Medical Humanities 2004; 30 106-106 Published Online First: 06 Dec 2004.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The World of Philosophy

- Aug 8, 2021

Frankenstein Ethics

The other moral in Frankenstein and how to apply it to human brains and reanimated pigs Some neurology experiments — such as growing miniature human brains and reanimating the brains of dead pigs — are getting weird. It's time to discuss ethics. SCOTTY HENDRICKS

Two bioethicists consider a lesser known moral in Frankenstein and what it means for science today.

We are still a ways from Shelley's novel, but we are getting closer.

They suggest that scientists begin thinking of sentient creations as having moral rights regardless of what the law says.

Compared to what we see in science fiction, most of our major advances in modifying organisms are actually rather dull. For example, despite being deemed "Frankenfoods," genetically modified crops are typically changed in simple ways that make them hardier and easier to grow. We are still a long way from approaching the work of Dr. Frankenstein. However, we are getting closer all the time. And exactly what we should do in the event that we create an organism with moral standing remains the subject of some debate. Because of this, Dr. Julian Koplin of the University of Melbourne Law School and Dr. John Massie of The Royal Children's Hospital in Melbourne wrote a paper discussing a lesser known ethical lesson of Frankenstein and how it might be applied to some of our more cutting-edge experiments — before we find ourselves asking what to do with artificially created sentient life.

The other moral in Frankenstein

The moral of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein that most people are familiar with is, "Don't play God," or some variation of that theme. Most film and television versions of the story follow this route, perhaps most notably in the famous 1931 film adaptation starring Boris Karloff as the monster. This take on the ethical lesson of Frankenstein may be more useful than the broad warning against hubris, as modern science is getting ever closer to creating things with sentience.

However, Shelly's work covers many themes. One of them is that the real moral failure of Victor Frankenstein was not in creating his creature but in failing to meet or even consider the moral obligations he had to it. Thus, your pedantic friend who notes, "Frankenstein is the name of the doctor, not the monster," is both annoying and correct. Frankenstein never bothered to name his creature after bringing it into the world.

That's not the only thing Frankenstein failed to give the creature. The authors explain: "...the 'monster' had at least some degree of moral status — which is to say, he was the kind of being to which we have moral obligations. Frankenstein refused to recognize any duties towards his creation, including even the modest duties we currently extend towards nonhuman research animals; Frankenstein denied his creature a name, shelter, healthcare, citizenship, or relationships with other creatures of its kind. In so doing, Frankenstein wronged his creation."

The Creature, as the monster is sometimes known in the novel, differs greatly from how most films depict him — uncoordinated, stupid, and brutish. He learns to speak several languages, references classic literature, and reveals that he is a vegetarian for ethical reasons. Before he spends his time devising a complex revenge plot against his creator, his primary desire is for companionship. He is also quite sensitive. Even if he is not entitled to the same moral standing as other humans, it seems intuitive that he has some moral standing that is never recognized. This take on the ethical lesson of Frankenstein may be more useful than the broad warning against hubris, as modern science is getting ever closer to creating things with sentience.

Brain experiments are getting creepy and weird

One area of experimentation is the creation of human brain organoids that provide simplified, living 3D models of the brain. These organoids are grown with stem cells over the course of several months and are very similar to certain parts of the cortex. Scientists are doing this in their effort to better understand the brain and its associated diseases. While it is unlikely that we have created anything complex enough to achieve consciousness, many researchers maintain that it is theoretically possible for an organoid to become conscious. Some experiments have already produced tissues that are light sensitive , suggesting at least a limited capacity for awareness.

In a turn toward a more literal reading of Shelley, a team of Yale scientists reanimated pig brains and kept some of them alive for 36 hours. While these revived brains neither were attached to pig bodies nor exhibited the electrical signals associated with consciousness, the study does raise the possibility that such a thing could be done. Other experiments seem to be based more on The Island of Dr. Moreau by H.G. Wells, including one in which monkeys were modified to carry a human gene for brain development. These monkeys had better short-term memory and reaction times than non-modified monkeys. Where do we go from here? The authors do not propose that we stop any particular research but instead consider the problem of moral standing. We should decide now what duties and moral obligations we owe to a sentient creature before the problem is literally looking us in the face. While it is true that animal research is tightly regulated, nobody seems to have planned for reanimated pigs or monkeys with human-like intelligence. Though ethics reviews of experiments likely would catch the most egregious experiments before they venture into the realm of Gothic horror, they might miss a few things if we do not engage in some bioethical reflection now. The authors suggest that we take two points from Frankenstein to guide us in drawing up new ethical standards: First, we should consider anything we create as existing on a moral plane no matter what the current regulations state. Exactly where a particular creature might fall on the moral spectrum is another question. (For instance, a reanimated pig brain does not have the same moral standing as a human being.)

Second, they remind us that we must try to avoid holding prejudice toward any moral beings that look or act differently than we do. In the novel, Dr. Frankenstein recoils in horror almost instinctively at what he created with monstrous results (no pun intended). We must be willing to consider atypical beings as potentially worthy of moral standing no matter how strange they may be.

Finally, they advise that every manipulated organism be treated with respect. This might be the most easily applied — had Victor Frankenstien respected the graves he looted to create his monster, none of the misfortune that followed would have befallen him.

Recent Posts

Euthanasia in Kant's Ethics

Is This the Best of All Possible Worlds?

Aquinas on Structural Racism

Frankenstein Reflects the Hopes and Fears of Every Scientific Era

The novel is usually considered a cautionary tale for science, but its cultural legacy is much more complicated.

The bicentennial of Frankenstein started early. While Mary Shelley’s momentous novel was published anonymously in 1818, the commemorations began last year to mark the dark and stormy night on Lake Geneva when she (then still Mary Godwin, having eloped with her married lover Percy Shelley) conceived what she called her “hideous progeny.”

In May, MIT Press will publish a new edition of the original text, “annotated for scientists, engineers, and creators of all kinds.” As well as the explanatory and expository notes throughout the book, there are accompanying essays by historians and other writers that discuss Frankenstein ’s relevance and implications for science and invention today.

It’s a smart idea, but treating Frankenstein as a meditation on the responsibilities of the scientist, and the dangers of ignoring them, is bound to give only a partial view of Shelley’s novel. It’s not just a book about science. Moreover, focusing on Shelley’s text doesn’t explore the scope of the Frankenstein myth itself, including its message for scientists.

This is one of those stories everyone knows even without having read the original: Man makes monster; monster runs amok; monster kills man. It may come as a surprise to discover that the creator, not the creature, is called Frankenstein, and that the original creature was not the shambling, grunting, green-faced lunk played by Boris Karloff in the 1931 movie but an articulate soul who meditates on John Milton’s Paradise Lost . Such misconceptions might do little justice to Shelley, but as the critic Chris Baldick has written, “That series of adaptations, allusions, accretions, analogues, parodies, and plain misreadings with follows upon Mary Shelley’s novel is not just a supplementary component of the myth; it is the myth.”

In any case, the essays in the MIT edition have surprisingly little to say about the reproductive and biomedical technologies of our age, such as assisted conception, tissue engineering, stem-cell research, cloning, genetic manipulation, and “ synthetic human entities with embryo-like features ”—the remarkable potential “organisms” with a Frankensteinian name.

That feels like a missed opportunity. Frankenstein is still frequently the first point of reference for media reports of such cutting-edge developments, just as it was when human IVF became a viable technique in the early 1970s. The “Franken” label is now a lazy journalistic cliché for a technology you should distrust, or at least regard as “weird”: Frankenfoods, Frankenbugs. The “wisdom of repugnance,” the phrase coined by the U.S. bioethicist Leon Kass and which informed the decision of the George W. Bush administration to pose drastic restrictions on federally funded stem-cell research in 2001, harked back directly to Mary Shelley’s novel.

Let’s be in no doubt: Frankenstein is one of the most extraordinary achievements in English literature. It’s not flawlessly written, the construction is sometimes awkward—yet it is a profound and unsettling vision, deeply informed about the science and philosophy of its day. That it was written not by an established and experienced author but by a teenager at a very difficult period in her life feels almost miraculous. It’s in fact those troubled circumstances and those flaws that have helped the book to persist, to keep on stimulating debate, and to continue attracting adaptations and variations—some good, many bad, some plain execrable.

It’s too often suggested—some of the commentaries in the MIT edition repeat the idea—that Frankenstein is a warning about a hubristic, overreaching science that unleashes forces it cannot control. “Victor’s error is failing to think harder about the potential repercussions of his work,” writes the bioethicist Josephine Johnston. To Mary Shelley’s biographer Anne Mellor, the novel “portrays the penalties of violating Nature.” This makes it sound as though the attempt to create an “artificial person” from scavenged body parts was always going to end badly: that it was a crazy, doomed project from the start.

But Mary Shelley takes some pains to show that the real problem is not what Victor Frankenstein made, but how he reacted to it. “Now that I had finished,” he says, “the beauty of the dream vanished, and breathless horror and disgust filled my heart.” He rejects the “hideous wretch” he has created, but nothing about that seems inevitable. What would have happened if Victor had instead lived up to his responsibilities by choosing to nurture his creature?

One might answer that the result would have been a pretty dull and short novel. But I’m not so sure. Imagine the story of Victor struggling to have the creature accepted by a society that shunned it as vile and unnatural. We would then be reading a book about social prejudice and our preconceptions of nature—indeed, about the kind of prospect one can easily imagine for a human born by cloning today (if such as thing were scientifically possible and ethically permissible). The moral and philosophical landscape it might have explored would be no less rich.

That Victor did not do this—that he spurned his creation the moment he had made it, merely because he judged it ugly—means that, to my mind, the conclusion we should reach is the one that the speculative-fiction author Elizabeth Bear articulates in the new volume. It is for Victor’s “failure of empathy and his moral cowardice,” Bear says—for his overweening egotism and narcissism—that we should think ill of him, and not because of what he discovered or created.

Mary Shelley, however, gives her readers mixed messages. What she shows us is a man behaving badly, but what she seems to tell us is that he is tragic and sympathetic. All of her characters think so well of “poor, dear Victor” that we’re given pause. Even Robert Walton, the ship’s captain who finds Victor pursuing his creature in the Arctic and whose letters describing that encounter begin and end the book, sees in him a noble, pitiable figure, “amiable and attractive” despite his wrecked and emaciated state. Frankenstein’s only critic is his creature.

This could be seen as a rather exquisite piece of authorial artifice, an early example of the unreliable narrator. It seems more likely to me that Shelley herself wasn’t clear what to make of Victor. In her revised edition of 1831, she emphasized the Faustian aspect of the tale, writing in her introduction that she wanted to show how “supremely frightful would be the effect of any human endeavour to mock the stupendous mechanism of the Creator of the world.” In other words, it was preordained that the creature would be hideous, and inevitable that its creator would recoil “horror-stricken.” That wasn’t then a character failing of Victor’s.

This idea invites the interpretation that Mellor offers in the new edition: “Nature prevents Victor from constructing a normal human being: His unnatural method of reproduction spawns an unnatural being, a freak.”

She sees this as a feminist interpretation (Nature being, in her view, feminine and inviolable), I feel that to the extent that Shelley’s book supports a feminist reading, it is not this, and to the extent that one might draw this interpretation, it is not a feminist one. To condemn Victor for violating “Mother Nature” with his “unnatural being” seems plain disturbing in the 21st century. Certainly it bears out the complaint of the British biologist J. B. S. Haldane in 1924:

There is no great invention, from fire to flying, which has not been hailed as an insult to some god. But if every physical and chemical invention is a blasphemy, every biological invention is a perversion.

By accepting that Victor’s work is inherently perverted and bound to end hideously, Mellor’s accusation leaves us wondering what exactly is meant by “unnatural.” Which real-life interventions are guaranteed to produce a freak? Might that be so with IVF, as its early detractors insisted? Is it the case for so-called “three-parent babies” made by mitochondrial transplantation, a misleading term apparently invented for the very purpose of insisting on its unnaturalness? Would the first human clone be the next “unnatural freak,” if ever that technology becomes possible and desirable?

“Unnatural” is not a neutral description but a morally laden term, and dangerous for that reason: Its use threatens to prejudice or shut down discussion before it begins.

There’s something of this rush to judgment also in the commentary of Charles Robinson, the Frankenstein scholar who introduces the new annotated text. Speaking about the evils released from Pandora’s box by Prometheus’s brother Epimetheus in Greek myth—Shelley subtitled her novel “The Modern Prometheus”—Robinson says that such terrible consequences of careless tampering are reflected in “the pesticide DDT, the atom bomb, Three Mile Island, Chernobyl,” and the British government’s allowing a stem-cell scientist to perform genome editing “despite objections that ethical issues were being ignored.”

But each of these modern developments in fact involved a complex and case-specific chain of events, and incurs a delicate balance of pros and cons. Some, such as the Chernobyl nuclear accident, had rather little to do with the intrinsic ethics of the underlying technology, but were a consequence of particular political and bureaucratic decisions. To imply that they unambiguously show a lack of foresight (Epimetheus’s name means “afterthought”) or indeed of responsibility on the part of the scientists whose work made them possible would be to cheapen the discourse and to evade the real issues.

The decision on genome editing, meanwhile—presumably this refers to the granting of a license by the U.K. Human Fertilization and Embryology Authority for gene-editing of very early stage, non-viable embryos—supports medical research that might, among other things, help to reduce rates of miscarriage. Such work will never be free of ethical objections raised by those opposed to all research on human embryos. Without a doubt, Frankenstein asks challenging questions about research like this that touches on interventions in human life. But to suggest that it warns us to abjure such work doesn’t do Mary Shelley justice.

What, then, does the story of Victor Frankenstein’s doomed and misguided quest have to tell us about modern science in general, and technological intervention in life in particular? I think that, to find an answer, we needn’t try too hard to discern Shelley’s own intentions. Her text arose not out of a conscious desire to tell a moral tale—not, at any rate, one about science—but literally out of a nightmare. In her preface to the 1831 edition she described how the “ghastly image” of a “pale student of unhallowed arts kneeling beside the thing he had put together” came to her as she tried to sleep after listening to conversations between Byron and Percy Shelley deep into the night, concerning the “principle of life.”

That retrospective account surely included some embellishment, but it seems fair to accept Shelley’s assertion that “my imagination, unbidden, possessed and guided me.” The impact and enduring fascination of her novel depend on the author not having worked too hard to impose a meaning on the “ghastly image” she dreamed, to resolve the conflicts that it evoked in her, or to maintain a consistent attitude as she reworked her book.

So we can draw Luddite conclusions if that’s what we look for, just as we can read into the text Shelley’s fears about childbirth, her frustration and anger at her father’s rejection, political worries about the destructive potential of the inchoate mob, or an examination of male terror of female sexual and procreative independence.

But it surely matters at least as much now not just what Frankenstein is about but what the Frankenstein myth is about—what as a culture we have made of this wonderful, undisciplined book, whether that is Hollywood’s insistence that the artificial being be a stiff-limbed quasi-robotic mute or more contemporary efforts to tell a story that is sympathetic to the creature’s point of view. Frankenstein , after all, was never intended as an instruction manual to the bioethicist or the engineer. It is better seen as a catalyst, even an agent provocateur , that lures us into disclosing what we truly hope and fear.

The ambiguity of the book is an essential feature of myth, and all modern myths come from a similar fertile lack of authorial control. That isn’t a failing. Everyone loves a well-crafted story, but those crafted partly by the unconscious and delivered to us misshapen and unfinished hold a particular potential to be reanimated, time after time, to fit and to dramatize the anxieties of the age. Like Victor, we make Frankenstein in our own image.

About the Author

More Stories

A Tiny, Lab-Size Wormhole Could Shatter Our Sense of Reality

The Universe Is Always Looking

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- My Bibliography

- Collections

- Citation manager

Save citation to file

Email citation, add to collections.

- Create a new collection

- Add to an existing collection

Add to My Bibliography

Your saved search, create a file for external citation management software, your rss feed.

- Search in PubMed

- Search in NLM Catalog

- Add to Search

The Ethical Interest of Frankenstein; Or, the Modern Prometheus: A Literature Review 200 Years After Its Publication

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain.

- 2 Bioethics Chair, Universitat de Vic-Universitat Central de Catalunya, Vic, Spain.

- 3 School of Medicine, Universitat de Vic-Universitat Central de Catalunya, Casa de Convalescència, Dr. Junyent 1, 08500, Vic, Spain.

- 4 Department of Experimental and Health Sciences, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. [email protected].

- 5 School of Medicine, Universitat de Vic-Universitat Central de Catalunya, Casa de Convalescència, Dr. Junyent 1, 08500, Vic, Spain. [email protected].

- PMID: 32533445

- DOI: 10.1007/s11948-020-00229-x

Two hundred years after it was first published, Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus remains relevant. This novel has endured because of its literary merits and because its themes lend themselves to analysis from multiple viewpoints. Scholars from many disciplines have examined this work in relation to controversial scientific research. In this paper, we review the academic literature where Frankenstein is used to discuss ethics, bioethics, science, technology and medicine. We searched the academic literature and carried out a content analysis of articles discussing the novel and films derived from it, analyzing the findings qualitatively and quantitatively. We recorded the following variables: year and language of publication, whether it referred to the novel or to a film, the academic discipline in which it was published, and the topics addressed in the analysis. Our findings indicate that the scientific literature on Frankenstein focuses mainly on science and the personality of the scientist rather than on the creature the scientist created or ethical aspects of his research. The scientist's responsibility is central to the ethical interest of Frankenstein; this issue entails both the motivation underlying the scientist's acts and the consequences of these acts.

Keywords: Ethics; Feature films; Frankenstein; Literature analysis; Science; Scientist.

PubMed Disclaimer

Similar articles

- Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus: a classic novel to stimulate the analysis of complex contemporary issues in biomedical sciences. Cambra-Badii I, Guardiola E, Baños JE. Cambra-Badii I, et al. BMC Med Ethics. 2021 Feb 23;22(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12910-021-00586-7. BMC Med Ethics. 2021. PMID: 33622293 Free PMC article.

- Facing the Pariah of Science: The Frankenstein Myth as a Social and Ethical Reference for Scientists. Nagy P, Wylie R, Eschrich J, Finn E. Nagy P, et al. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020 Apr;26(2):737-759. doi: 10.1007/s11948-019-00121-3. Epub 2019 Jul 10. Sci Eng Ethics. 2020. PMID: 31292834

- [A study of development of medicine and science in the nineteenth century science fiction: biomedical experiments in Mary Shelley's Frankenstein]. Choo JU. Choo JU. Uisahak. 2014 Dec;23(3):543-72. doi: 10.13081/kjmh.2014.23.543. Uisahak. 2014. PMID: 25608508 Korean.

- [Allotransplantation, literature and movie]. Glicenstein J. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007 Oct;52(5):509-12. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2007.07.010. Epub 2007 Sep 11. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2007. PMID: 17850947 Review. French.

- [Man and his fellow-creatures under ethical aspects]. Teutsch GM. Teutsch GM. ALTEX. 2005;22(4):199-226. ALTEX. 2005. PMID: 16344905 Review. German.

- Banerjee, S. (2011). Home is where mamma is: Reframing the science question in Frankenstein. Women's Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00497878.2011.527783 . - DOI

- Barns, I. (1990). Monstrous nature or technology?: Cinematic resolutions of the “Frankenstein Problem”. Science as Culture. https://doi.org/10.1080/09505439009526278 . - DOI

- Bell, R., & Lederman, N. (2003). Understandings of the nature of science and decision making on science and technology based issues. Science Education. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.10063 . - DOI

- Bishop, M. (1994). The “making” and re-making of man: 1. Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, and transplant surgery. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 87(12), 749–751.

- Brem, S., & Anijar, K. (2003). The bioethics of fiction: The chimera in film and print. American Journal of Bioethics. https://doi.org/10.1162/15265160360706787 . - DOI

Publication types

- Search in MeSH

LinkOut - more resources

Full text sources.

- Citation Manager

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

- Help & FAQ

Introduction: Frankenstein, Race and Ethics

Research output : Contribution to journal › Editorial › peer-review

At the Frankenstein @ 200 colloquium, March 2019, Princeton University (sponsored by a David Gardner Grant), Professors John Bugg (Fordham University) and Adam Potkay (The College of William and Mary) presented papers addressing the topic, ‘Teaching Frankenstein: Race, Ethics, and Pedagogy’. My introduction sets the stage for their now evolved articles. John Bugg’s ‘Teaching Frankenstein and Race’ takes up the problems of turning this conjunction into an allegory, a gesture in the first reviews, and persisting in critical discussion. Adam Potkay takes up a related conjunction, pressed into a conditional logic: the foundation of happiness on virtue (the classical tradition), or the reverse, the foundation of virtue on happiness (social and material contingencies). Bugg’s story wends through critical and reception history to the classrooms of the twenty-first century; Potkay traces a genealogy of race and happiness into Richard Wright’s midcentury novel of racial trauma, Native Son.

| Original language | English (US) |

|---|---|

| Pages (from-to) | 12-21 |

| Number of pages | 10 |

| Journal | |

| Volume | 34 |

| Issue number | 1 |

| DOIs | |

| State | Published - Jan 2 2020 |

All Science Journal Classification (ASJC) codes

- Literature and Literary Theory

- Frankenstein

- Mary Shelley

- US Declaration of Independence

- racialized differentials

- reception history

- rejected daughters

- rejected sons

Access to Document

- 10.1080/09524142.2020.1761110

Other files and links

- Link to publication in Scopus

Fingerprint

- Happiness Medicine and Dentistry 100%

- Injury Medicine and Dentistry 33%

- Gesture Medicine and Dentistry 33%

- Richard Wright Arts and Humanities 25%

- Critical discussion Arts and Humanities 25%

- Conditional Logic Arts and Humanities 25%

- Racial Trauma Keyphrases 25%

T1 - Introduction

T2 - Frankenstein, Race and Ethics

AU - Wolfson, Susan J.

N1 - Publisher Copyright: © 2020, © 2020 The Keats-Shelley Memorial Association.

PY - 2020/1/2

Y1 - 2020/1/2

N2 - At the Frankenstein @ 200 colloquium, March 2019, Princeton University (sponsored by a David Gardner Grant), Professors John Bugg (Fordham University) and Adam Potkay (The College of William and Mary) presented papers addressing the topic, ‘Teaching Frankenstein: Race, Ethics, and Pedagogy’. My introduction sets the stage for their now evolved articles. John Bugg’s ‘Teaching Frankenstein and Race’ takes up the problems of turning this conjunction into an allegory, a gesture in the first reviews, and persisting in critical discussion. Adam Potkay takes up a related conjunction, pressed into a conditional logic: the foundation of happiness on virtue (the classical tradition), or the reverse, the foundation of virtue on happiness (social and material contingencies). Bugg’s story wends through critical and reception history to the classrooms of the twenty-first century; Potkay traces a genealogy of race and happiness into Richard Wright’s midcentury novel of racial trauma, Native Son.

AB - At the Frankenstein @ 200 colloquium, March 2019, Princeton University (sponsored by a David Gardner Grant), Professors John Bugg (Fordham University) and Adam Potkay (The College of William and Mary) presented papers addressing the topic, ‘Teaching Frankenstein: Race, Ethics, and Pedagogy’. My introduction sets the stage for their now evolved articles. John Bugg’s ‘Teaching Frankenstein and Race’ takes up the problems of turning this conjunction into an allegory, a gesture in the first reviews, and persisting in critical discussion. Adam Potkay takes up a related conjunction, pressed into a conditional logic: the foundation of happiness on virtue (the classical tradition), or the reverse, the foundation of virtue on happiness (social and material contingencies). Bugg’s story wends through critical and reception history to the classrooms of the twenty-first century; Potkay traces a genealogy of race and happiness into Richard Wright’s midcentury novel of racial trauma, Native Son.

KW - Abjection

KW - Frankenstein

KW - Mary Shelley

KW - Native Son

KW - US Declaration of Independence

KW - ethnicity

KW - racialized differentials

KW - reception history

KW - rejected daughters

KW - rejected sons

KW - slavery

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?scp=85087568455&partnerID=8YFLogxK

UR - http://www.scopus.com/inward/citedby.url?scp=85087568455&partnerID=8YFLogxK

U2 - 10.1080/09524142.2020.1761110

DO - 10.1080/09524142.2020.1761110

M3 - Editorial

AN - SCOPUS:85087568455

SN - 0952-4142

JO - Keats-Shelley Review

JF - Keats-Shelley Review

200 Years of Frankenstein: Mary Shelley’s Masterpiece as a Lens on Today’s Most Pressing Questions of Science, Ethics, and Human Creativity

By maria popova.

A teenage girl grieving the death of her infant daughter is sitting on the almost unbearably beautiful shore of a Swiss mountain lake. Her own mother, a pioneering feminist and political philosopher , has died of complications from childbirth exactly a month after bringing her into the world. Her philosopher father has cut her off for eloping to Europe with her lover — a struggling poet, whom she would marry six months later, after the suicide of his estranged first wife.

Mary Shelley (August 30, 1797–February 1, 1851) is just shy of her nineteenth birthday. She and her lover — Percy Bysshe Shelley — are spending the summer with Percy’s best friend, the poet Lord Byron, whose wife has just left him and taken custody of their infant daughter, Ada Lovelace . One June evening, Lord Byron proposes that the downtrodden party amuse themselves by each coming up with a ghost story. What Mary dreams up would go on to become one of the world’s most visionary works of literature, strewn with abiding philosophical questions about creativity and responsibility, the limits and liabilities of science, and the moral dimensions of technological progress.

The year is 1816. Decades stand between her and the first working incandescent light bulb. It would be more than a century before the Milky Way is revealed as not the whole of the universe but one of innumerable galaxies in it. Photography is yet to be invented; the atom yet to be split; Neptune, penicillin, and DNA yet to be discovered; relativity theory and quantum mechanics yet to be conceived of. The very word scientist is yet to be coined ( for the Scottish mathematician Mary Somerville ).

Against this backdrop and its narrow parameters of knowledge barely imaginable to today’s vista of scientific understanding, Mary Shelley unleashed her imagination on Lord Byron’s challenge and began gestating what would be published eighteen months later, on the first day of 1818, as Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus . Its message is as cautionary as it is irrepressibly optimistic. “The labours of men of genius,” this woman of genius writes, “however erroneously directed, scarcely ever fail in ultimately turning to the solid advantage of mankind.”

Two hundred years later, Arizona State University launched The Frankenstein Bicentennial Project — a cross-disciplinary, multimedia endeavor to engage the people of today with the timeless issues of science, technology, and creative responsibility posed by Shelley’s searching intellect and imagination. As part of the celebration, MIT Press published Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds ( public library ) — Shelley’s original 1818 manuscript, line-edited by the world’s leading expert on the text and accompanied by annotations and essays by prominent contemporary thinkers across science, technology, philosophy, ethics, feminism, and speculative fiction. What emerges is the most thrilling science-lensed reading of a literary classic since Lord Byron’s Don Juan annotated by Isaac Asimov .

Editors David H. Guston, Ed Finn, and Jason Scott Robert, who consider Shelley’s masterwork “a book that can encourage us to be both thoughtful and hopeful” and describe their edition as one intended “to enhance our collective understandings and to invent — intentionally — a world in which we all want to live and, indeed, a world in which we all can thrive,” write in the preface:

No work of literature has done more to shape the way humans imagine science and its moral consequences than Frankenstein; or The Modern Prometheus , Mary Shelley’s remarkably enduring tale of creation and responsibility… In writing Frankenstein, Mary produced both in the creature and in its creator tropes that continue to resonate deeply with contemporary audiences. Moreover, these tropes and the imaginations they engender actually influence the way we confront emerging science and technology, conceptualize the process of scientific research, imagine the motivations and ethical struggles of scientists, and weigh the benefits of scientific research against its anticipated and unforeseen pitfalls.

It is almost impossible to imagine what the world, the everyday world, was like two centuries ago — a difference so profound it seeps into language itself. With this in mind, the editors offer a thoughtful note on their choice of referring to Doctor Frankenstein’s creation as “the creature” (rather than daemon , which Shelley herself uses, or monster , as posthumous criticism often does). In consonance with bryologist Robin Wall Kimmerer’s insight into how naming confers dignity upon life , they write:

It is worth pointing out that the way we now use the word creature ignores a richer etymology. Today, we refer to birds and bees as creatures. Living things are creatures by virtue of their living-ness. When we call something a creature today, we rarely think in terms of something that has been created, and thus we erase the idea of a creator behind the creature. We have likewise lost the social connotation of the term creature, for creatures are made not just biologically (or magically) but also socially.

This nexus of the scientific and the social at the heart of Shelley’s novel comes alive in a lovely companion to the annotated edition: Reanimation! — a seven-part series of animated conversations with scientists by science communication powerhouse Massive , exploring the prescient questions embedded in Shelley’s novel — questions touching on the nature of consciousness, the evolution and definition of life, the ethics of genetic engineering, the future of the human body and artificial intelligence.

In the first film — which calls to mind Freeman Dyson’s assertion that “a new generation of artists, writing genomes as fluently as Blake and Byron wrote verses, might create an abundance of new flowers and fruit and trees and birds to enrich the ecology of our planet” — BBC science communicator Britt Wray and ecologist and biologist Ben Novak echo poet Denise Levertov’s lament about our tendency to see ourselves as separate from nature through the lens of genetic engineering and synthetic biology:

I’m really hoping that synthetic biology as a whole can drive a different appreciation — a different definition and relationship — of what we see to be nature. For years, we have peddled this notion that humans are separate entities from nature — there’s the arrogance that humans are somehow divinely above nature and we’re the caretakers of the world and we can do whatever we want with it. But there really hasn’t been a universal realization that we are nature.

Perhaps the central animating question of Shelley’s novel is what she termed “the nature of the principle of life” — that curious island of being amid the vast cosmic ocean of nonbeing. This is what theoretical physicist Sara Imari Walker and exoplanetary scientist and astrobiologist Caleb Scharf consider in the second film, exploring the nature and definition of life on Earth and beyond, and what we mean by intelligence when we speak of intelligent life:

We’ve really thought about life as being a binary phenomenon — something is alive or it’s not… In the context of origins of life, that’s really critical, because you want to talk about the transition between nonliving things and living things… [But] life in general is actually a process that occurs across multiple scales, and you can talk about a cell in my body being alive or you can talk about me being alive and you can also… go up in scale and maybe think about societies as being alive. That’s one of the things that’s really interesting about life… it has this kind of hierarchical structure where you have many layers of organization. […] We might be able to understand more universal properties of life based on organizational principles — [not] just focusing on the things life is made of, but how it is organized. That’s [why] reductionism has been hard in biology — because we always try to separate out these scales and treat them separately. But [in reality] you have ordered processes and dynamics across multiple scales — that really is the intrinsic indicative process of life.

In the third film, philosopher and cognitive scientist David Chalmers and comparative neuroscientist Danbee Kim examine the nature of consciousness — a philosophical inquiry that occupied Plato , entered the realm of science through William James’s pioneering writings , and has been the subject of another lovely animation by Massive:

Trying to go directly from the cells to behavior is not going to be possible. Why? Because there are actually several levels of organization in between them. If you start with the cell, then the next level of organization would be a circuit. And how does the nervous system as an organ interact with other organs in the body? And then, after that, is the organism and all the movements produced by an organism. But that still isn’t behavior, because behavior is something that arises when you have goals for your movements and the only way for you to really pick or even decide a goal is not in a vacuum — it has to be within your environment: What other creatures, what other organisms, do you have to coordinate with in order to exist in your immediate local physical space? […] It’s this interplay between brains, bodies, and the world that, in the end, allows us to develop these goals… and the development of those goals is what I would call cognition .

In the fourth film, molecular biologist Kate Krueger and paleoanthropologist and archaeologist Genevieve Dewar consider the common human impulse for transformation, which undergirds both our most primitive Stone Age tools and our most advanced gene editing technologies:

Once we see the development of culture and social interactions, we actually see for the first time our species being able to step outside of and above biological evolution. […] It’s very rare that humans like to sit still and do nothing and maintain stasis. While we love what we know and we do want to maintain it, I think all of us would love to make the world a more interesting place and a more useful place, and be able to do more things and climb higher and move faster. This is also part of our nature — the desire to create and to grow and to change.

In the fifth film, engineer and ethicist Braden Allenby and biomedical engineer Conor Walsh contemplate the widening gap between our technological capabilities and our wisdom, and consider how the abiding philosophical question of what it means to be human is changing in the era of CRISPR and wearable robotics:

When you start to get a much more rapid change in technology, particularly technology that affects the human… you begin to get human as a process. The idea of human that we have is already changing much more rapidly than we know, but the process of human has simply accelerated. It continues, and we remain human.

In the sixth film, historian and philosopher of science Margaret Wertheim , neuroscientist and AI researcher Daniel Baer, and engineer and ethicist Branden Allenby reflect on our perpetually evolving definition of and ethical parameters around what constitutes intelligence and what makes an intelligence “artificial”:

I suspect that we are not going to think we see a conscious machine even when they are running the planet… We have an extraordinary ability as humans — as soon as we offload something to machines that has to do with our cognition, we call it simple and it’s obviously not part of intelligence. [For example], the first people who were called computers were in fact very highly trained mathematicians, many of them women , who did systemic mathematical solutions for very complex equations for things like ballistics… and they were regarded as extremely intelligent. That lasted until TI came up with the first calculator and then, suddenly, we decided that mathematical calculations weren’t part of being intelligent. So my suspicion is that we already have machines that, to at least first degree, are AI.

In the seventh and final film, BBC science communicator Britt Wray, theoretical physicist Sara Imari Walker, and paleoanthropologist and archaeologist Genevieve Dewar examine what may be the overarching philosophical concern of Shelley’s masterwork — the God complex with which we wield our tools and regard their creations, and the interplay between fear and curiosity indelible to all innovation and to every leap of science:

What makes Homo sapiens special and different is their ability to innovate on the fly, come up with new ideas and new ways of doing things, [and] learn from the mistake of others and communicate rapidly… to build upon the mistakes of the past.

Complement Frankenstein: Annotated for Scientists, Engineers, and Creators of All Kinds with philosopher Joanna Bourke’s synthesis of three centuries of ideas about what it means to be human and Maya Angelou’s arresting message to humanity in the golden age of twentieth-century scientific breakthrough, then visit Massive for more animated conversations with leading scientists about some of the most exciting frontiers of science and the most morally complex questions of our time.

— Published June 14, 2018 — https://www.themarginalian.org/2018/06/14/frankenstein-science-mit-massive/ —

www.themarginalian.org

PRINT ARTICLE

Email article, filed under, animation books culture mary shelley philosophy science, view full site.

The Marginalian participates in the Bookshop.org and Amazon.com affiliate programs, designed to provide a means for sites to earn commissions by linking to books. In more human terms, this means that whenever you buy a book from a link here, I receive a small percentage of its price, which goes straight back into my own colossal biblioexpenses. Privacy policy . (TLDR: You're safe — there are no nefarious "third parties" lurking on my watch or shedding crumbs of the "cookies" the rest of the internet uses.)

- Open access

- Published: 23 February 2021

Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus : a classic novel to stimulate the analysis of complex contemporary issues in biomedical sciences

- Irene Cambra-Badii ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1233-3243 1 ,

- Elena Guardiola 2 &

- Josep-E. Baños 2

BMC Medical Ethics volume 22 , Article number: 17 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

22k Accesses

4 Citations

4 Altmetric

Metrics details

Advances in biomedicine can substantially change human life. However, progress is not always followed by ethical reflection on its consequences or scientists’ responsibility for their creations. The humanities can help health sciences students learn to critically analyse these issues; in particular, literature can aid discussions about ethical principles in biomedical research. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus (1818) is an example of a classic novel presenting complex scenarios that could be used to stimulate discussion.

Within the framework of the 200th anniversary of the novel, we searched PubMed to identify works that explore and discuss its value in teaching health sciences. Our search yielded 56 articles, but only two of these reported empirical findings. Our analysis of these articles identified three main approaches to using Frankenstein in teaching health sciences: discussing the relationship between literature and science, analysing ethical issues in biomedical research, and examining the importance of empathy and compassion in healthcare and research. After a critical discussion of the articles, we propose using Frankenstein as a teaching tool to prompt students to critically analyse ethical aspects of scientific and technological progress, the need for compassion and empathy in medical research, and scientists’ responsibility for their discoveries.

Frankenstein can help students reflect on the personal and social limits of science, the connection between curiosity and scientific progress, and scientists’ responsibilities. Its potential usefulness in teaching derives from the interconnectedness of science, ethics, and compassion. Frankenstein can be a useful tool for analysing bioethical issues related to scientific and technological advances, such as artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and cloning. Empirical studies measuring learning outcomes are necessary to confirm the usefulness of this approach.

Peer Review reports

In the last two centuries, scientific discoveries and technological innovations in biomedical sciences have improved the lives of most human beings immensely. However, education in the health sciences often fails to analyse the myriad consequences of scientific and technological advances from a bioethical point of view. In part, this failure derives from the compartmentalization of higher education. Bioethics is classified as a branch of moral philosophy, which is considered to lie in the sphere of the humanities rather than in the sphere of science and technology, and health sciences education largely ignores the humanities [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. Moreover, traditional teaching methods like lectures are poorly suited to teaching issues related to bioethics, such as compassionate care or appropriate relationships among health professionals, patients, and society, which require active pedagogical techniques that help students develop critical thinking skills and problem-solving competences [ 7 , 8 ].

Literature can help students appreciate the complexity of biomedical scenarios and improve their understanding of illness [ 9 ]. Various authors have suggested that literature can enhance future health professionals’ reflective thinking and improve their ability to analyse biomedical issues scientifically and honestly [ 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 ].

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the modern Prometheus , published in 1818, is one of the most influential works in the history of English literature. It has influenced scientific thinking [ 17 , 18 ] and has become a modern myth [ 17 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ]. Its value lies not only in its literary qualities, plot, and characters, but also in its reflective focus and compassionate approach to the character of Frankenstein’s creature [ 25 ].

Mary Shelley’s novel has come to be considered a canonical work. Its literary value and importance for science perdure today, more than 200 years after its first publication. Its place in the canon is ensured by its inclusion in educational curricula, especially in higher education [ 26 ], just as its place in popular culture is ensured by cinematic adaptations—especially James Whale’s (1931) and Kenneth Branagh’s (1994) versions, known worldwide. The current paper aims to examine the value of this work for ethicists and health sciences students, beyond popular culture or critical acclaim.

In a previous paper [ 27 ], we presented a content analysis of articles in the scientific literature that used the novel to discuss issues related to ethics, bioethics, science, technology, or medicine. We concluded that these articles focused mainly on Dr Frankenstein’s personality and scientific research rather than on ethical aspects related to his research or to the results of this research. Most of the papers analysed dealt with the importance of Frankenstein for reflecting science [ 17 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 ], scientists [ 20 , 32 ], the limits of scientific activity [ 22 , 24 , 33 ], and the need for peer review in research [ 32 , 34 ].

In the current article, we review the literature on Frankenstein in the medical humanities and health sciences and propose different ways that Shelley’s novel can be used in teaching future health professionals.