Quantitative study designs: Case Studies/ Case Report/ Case Series

Quantitative study designs.

- Introduction

- Cohort Studies

- Randomised Controlled Trial

- Case Control

- Cross-Sectional Studies

- Study Designs Home

Case Study / Case Report / Case Series

Some famous examples of case studies are John Martin Marlow’s case study on Phineas Gage (the man who had a railway spike through his head) and Sigmund Freud’s case studies, Little Hans and The Rat Man. Case studies are widely used in psychology to provide insight into unusual conditions.

A case study, also known as a case report, is an in depth or intensive study of a single individual or specific group, while a case series is a grouping of similar case studies / case reports together.

A case study / case report can be used in the following instances:

- where there is atypical or abnormal behaviour or development

- an unexplained outcome to treatment

- an emerging disease or condition

The stages of a Case Study / Case Report / Case Series

Which clinical questions does Case Study / Case Report / Case Series best answer?

Emerging conditions, adverse reactions to treatments, atypical / abnormal behaviour, new programs or methods of treatment – all of these can be answered with case studies /case reports / case series. They are generally descriptive studies based on qualitative data e.g. observations, interviews, questionnaires, diaries, personal notes or clinical notes.

What are the advantages and disadvantages to consider when using Case Studies/ Case Reports and Case Series ?

What are the pitfalls to look for.

One pitfall that has occurred in some case studies is where two common conditions/treatments have been linked together with no comprehensive data backing up the conclusion. A hypothetical example could be where high rates of the common cold were associated with suicide when the cohort also suffered from depression.

Critical appraisal tools

To assist with critically appraising Case studies / Case reports / Case series there are some tools / checklists you can use.

JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Series

JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist for Case Reports

Real World Examples

Some Psychology case study / case report / case series examples

Capp, G. (2015). Our community, our schools : A case study of program design for school-based mental health services. Children & Schools, 37(4), 241–248. A pilot program to improve school based mental health services was instigated in one elementary school and one middle / high school. The case study followed the program from development through to implementation, documenting each step of the process.

Cowdrey, F. A. & Walz, L. (2015). Exposure therapy for fear of spiders in an adult with learning disabilities: A case report. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 43(1), 75–82. One person was studied who had completed a pre- intervention and post- intervention questionnaire. From the results of this data the exposure therapy intervention was found to be effective in reducing the phobia. This case report highlighted a therapy that could be used to assist people with learning disabilities who also suffered from phobias.

Li, H. X., He, L., Zhang, C. C., Eisinger, R., Pan, Y. X., Wang, T., . . . Li, D. Y. (2019). Deep brain stimulation in post‐traumatic dystonia: A case series study. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics. 1-8. Five patients were included in the case series, all with the same condition. They all received deep brain stimulation but not in the same area of the brain. Baseline and last follow up visit were assessed with the same rating scale.

References and Further Reading

Greenhalgh, T. (2014). How to read a paper: the basics of evidence-based medicine. (5th ed.). New York: Wiley.

Heale, R. & Twycross, A. (2018). What is a case study? Evidence Based Nursing, 21(1), 7-8.

Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library. (2019). Study design 101: case report. Retrieved from https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu/tutorials/studydesign101/casereports.cfm

Hoffmann T., Bennett S., Mar C. D. (2017). Evidence-based practice across the health professions. Chatswood, NSW: Elsevier.

Robinson, O. C., & McAdams, D. P. (2015). Four functional roles for case studies in emerging adulthood research. Emerging Adulthood, 3(6), 413-420.

- << Previous: Cross-Sectional Studies

- Next: Study Designs Home >>

- Last Updated: Feb 29, 2024 4:49 PM

- URL: https://deakin.libguides.com/quantitative-study-designs

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods

Published on May 8, 2019 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023.

A case study is a detailed study of a specific subject, such as a person, group, place, event, organization, or phenomenon. Case studies are commonly used in social, educational, clinical, and business research.

A case study research design usually involves qualitative methods , but quantitative methods are sometimes also used. Case studies are good for describing , comparing, evaluating and understanding different aspects of a research problem .

Table of contents

When to do a case study, step 1: select a case, step 2: build a theoretical framework, step 3: collect your data, step 4: describe and analyze the case, other interesting articles.

A case study is an appropriate research design when you want to gain concrete, contextual, in-depth knowledge about a specific real-world subject. It allows you to explore the key characteristics, meanings, and implications of the case.

Case studies are often a good choice in a thesis or dissertation . They keep your project focused and manageable when you don’t have the time or resources to do large-scale research.

You might use just one complex case study where you explore a single subject in depth, or conduct multiple case studies to compare and illuminate different aspects of your research problem.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Once you have developed your problem statement and research questions , you should be ready to choose the specific case that you want to focus on. A good case study should have the potential to:

- Provide new or unexpected insights into the subject

- Challenge or complicate existing assumptions and theories

- Propose practical courses of action to resolve a problem

- Open up new directions for future research

TipIf your research is more practical in nature and aims to simultaneously investigate an issue as you solve it, consider conducting action research instead.

Unlike quantitative or experimental research , a strong case study does not require a random or representative sample. In fact, case studies often deliberately focus on unusual, neglected, or outlying cases which may shed new light on the research problem.

Example of an outlying case studyIn the 1960s the town of Roseto, Pennsylvania was discovered to have extremely low rates of heart disease compared to the US average. It became an important case study for understanding previously neglected causes of heart disease.

However, you can also choose a more common or representative case to exemplify a particular category, experience or phenomenon.

Example of a representative case studyIn the 1920s, two sociologists used Muncie, Indiana as a case study of a typical American city that supposedly exemplified the changing culture of the US at the time.

While case studies focus more on concrete details than general theories, they should usually have some connection with theory in the field. This way the case study is not just an isolated description, but is integrated into existing knowledge about the topic. It might aim to:

- Exemplify a theory by showing how it explains the case under investigation

- Expand on a theory by uncovering new concepts and ideas that need to be incorporated

- Challenge a theory by exploring an outlier case that doesn’t fit with established assumptions

To ensure that your analysis of the case has a solid academic grounding, you should conduct a literature review of sources related to the topic and develop a theoretical framework . This means identifying key concepts and theories to guide your analysis and interpretation.

There are many different research methods you can use to collect data on your subject. Case studies tend to focus on qualitative data using methods such as interviews , observations , and analysis of primary and secondary sources (e.g., newspaper articles, photographs, official records). Sometimes a case study will also collect quantitative data.

Example of a mixed methods case studyFor a case study of a wind farm development in a rural area, you could collect quantitative data on employment rates and business revenue, collect qualitative data on local people’s perceptions and experiences, and analyze local and national media coverage of the development.

The aim is to gain as thorough an understanding as possible of the case and its context.

In writing up the case study, you need to bring together all the relevant aspects to give as complete a picture as possible of the subject.

How you report your findings depends on the type of research you are doing. Some case studies are structured like a standard scientific paper or thesis , with separate sections or chapters for the methods , results and discussion .

Others are written in a more narrative style, aiming to explore the case from various angles and analyze its meanings and implications (for example, by using textual analysis or discourse analysis ).

In all cases, though, make sure to give contextual details about the case, connect it back to the literature and theory, and discuss how it fits into wider patterns or debates.

If you want to know more about statistics , methodology , or research bias , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Normal distribution

- Degrees of freedom

- Null hypothesis

- Discourse analysis

- Control groups

- Mixed methods research

- Non-probability sampling

- Quantitative research

- Ecological validity

Research bias

- Rosenthal effect

- Implicit bias

- Cognitive bias

- Selection bias

- Negativity bias

- Status quo bias

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Case Study? | Definition, Examples & Methods. Scribbr. Retrieved April 4, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/case-study/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, primary vs. secondary sources | difference & examples, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is action research | definition & examples, unlimited academic ai-proofreading.

✔ Document error-free in 5minutes ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Distinguishing case study as a research method from case reports as a publication type

- Kristine M. Alpi William R. Kenan, Jr. Library of Veterinary Medicine, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC http://orcid.org/0000-0002-4521-3523

- John Jamal Evans North Carolina Community College System, Raleigh, NC

Author Biography

Kristine m. alpi, william r. kenan, jr. library of veterinary medicine, north carolina state university, raleigh, nc.

Akers KG, Amos K. Publishing case studies in health sciences librarianship [editorial]. J Med Libr Assoc. 2017 Apr;105(2):115–8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5195/jmla.2017.212 .

Creswell JW. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2018.

Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2009.

Creswell JW. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2014.

Yin RK. Case study research and applications: design and methods. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE; 2018.

Stake RE. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 1995.

Merriam SB. Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1998.

Yazan B. Three approaches to case study methods in education: Yin, Merriam, and Stake. Qual Rep. 2015;20(2):134–52.

Bartlett L, Vavrus F. Rethinking case study research: a comparative approach. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017.

Walsh RW. Exploring the case study method as a tool for teaching public administration in a cross-national context: pedagogy in theory and practice. European Group of Public Administration Conference, International Institute of Administrative Sciences; 2006.

National Library of Medicine. Case reports: MeSH descriptor data 2018 [Internet]. The Library [cited 1 Sep 2018]. < https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/record/ui?ui=D002363 >.

National Library of Medicine. Organizational case studies: MeSH descriptor data 2018 [Internet]. The Library [cited 26 Oct 2018]. < https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/record/ui?ui=D019982 >.

American Psychological Association. APA databases methodology field values [Internet]. The Association; 2016 [cited 1 Sep 2018]. < http://www.apa.org/pubs/databases/training/method-values.aspx >.

ERIC. Case studies [Internet]. ERIC [cited 1 Sep 2018]. < https://eric.ed.gov/?ti=Case+Studies >.

Janke R, Rush K. The academic librarian as co-investigator on an interprofessional primary research team: a case study. Health Inf Libr J. 2014;31(2):116–22.

Clairoux N, Desbiens S, Clar M, Dupont P, St. Jean M. Integrating information literacy in health sciences curricula: a case study from Québec. Health Inf Libr J. 2013;30(3):201–11.

Federer L. The librarian as research informationist: a case study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2013 Oct;101(4):298–302. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3163/1536-5050.101.4.011 .

Medical Library Association. Journal of the Medical Library Association author guidelines: submission categories and format guidelines [Internet]. The Association [cited 1 Sep 2018]. < http://jmla.mlanet.org/ojs/jmla/about/submissions >.

Martin ER. Team effectiveness in academic medical libraries: a multiple case study. J Med Libr Assoc. 2006 Jul;94(3):271–8.

Hancock DR, Algozzine B. Doing case study research: a practical guide for beginning researchers. New York, NY: Teachers College Press; 2017.

Current Issue

ISSN 1558-9439 (Online)

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Writing a case report...

Writing a case report in 10 steps

- Related content

- Peer review

- Victoria Stokes , foundation year 2 doctor, trauma and orthopaedics, Basildon Hospital ,

- Caroline Fertleman , paediatrics consultant, The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust

- victoria.stokes1{at}nhs.net

Victoria Stokes and Caroline Fertleman explain how to turn an interesting case or unusual presentation into an educational report

It is common practice in medicine that when we come across an interesting case with an unusual presentation or a surprise twist, we must tell the rest of the medical world. This is how we continue our lifelong learning and aid faster diagnosis and treatment for patients.

It usually falls to the junior to write up the case, so here are a few simple tips to get you started.

First steps

Begin by sitting down with your medical team to discuss the interesting aspects of the case and the learning points to highlight. Ideally, a registrar or middle grade will mentor you and give you guidance. Another junior doctor or medical student may also be keen to be involved. Allocate jobs to split the workload, set a deadline and work timeframe, and discuss the order in which the authors will be listed. All listed authors should contribute substantially, with the person doing most of the work put first and the guarantor (usually the most senior team member) at the end.

Getting consent

Gain permission and written consent to write up the case from the patient or parents, if your patient is a child, and keep a copy because you will need it later for submission to journals.

Information gathering

Gather all the information from the medical notes and the hospital’s electronic systems, including copies of blood results and imaging, as medical notes often disappear when the patient is discharged and are notoriously difficult to find again. Remember to anonymise the data according to your local hospital policy.

Write up the case emphasising the interesting points of the presentation, investigations leading to diagnosis, and management of the disease/pathology. Get input on the case from all members of the team, highlighting their involvement. Also include the prognosis of the patient, if known, as the reader will want to know the outcome.

Coming up with a title

Discuss a title with your supervisor and other members of the team, as this provides the focus for your article. The title should be concise and interesting but should also enable people to find it in medical literature search engines. Also think about how you will present your case study—for example, a poster presentation or scientific paper—and consider potential journals or conferences, as you may need to write in a particular style or format.

Background research

Research the disease/pathology that is the focus of your article and write a background paragraph or two, highlighting the relevance of your case report in relation to this. If you are struggling, seek the opinion of a specialist who may know of relevant articles or texts. Another good resource is your hospital library, where staff are often more than happy to help with literature searches.

How your case is different

Move on to explore how the case presented differently to the admitting team. Alternatively, if your report is focused on management, explore the difficulties the team came across and alternative options for treatment.

Finish by explaining why your case report adds to the medical literature and highlight any learning points.

Writing an abstract

The abstract should be no longer than 100-200 words and should highlight all your key points concisely. This can be harder than writing the full article and needs special care as it will be used to judge whether your case is accepted for presentation or publication.

Discuss with your supervisor or team about options for presenting or publishing your case report. At the very least, you should present your article locally within a departmental or team meeting or at a hospital grand round. Well done!

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ’s policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

CC0006 Basics of Report Writing

Structure of a report (case study, literature review or survey).

- Structure of report (Site visit)

- Citing Sources

- Tips and Resources

The information in the report has to be organised in the best possible way for the reader to understand the issue being investigated, analysis of the findings and recommendations or implications that relate directly to the findings. Given below are the main sections of a standard report. Click on each section heading to learn more about it.

- Tells the reader what the report is about

- Informative, short, catchy

Example - Sea level rise in Singapore : Causes, Impact and Solution

The title page must also include group name, group members and their matriculation numbers.

Content s Page

- Has headings and subheadings that show the reader where the various sections of the report are located

- Written on a separate page

- Includes the page numbers of each section

- Briefly summarises the report, the process of research and final conclusions

- Provides a quick overview of the report and describes the main highlights

- Short, usually not more than 150 words in length

- Mention briefly why you choose this project, what are the implications and what kind of problems it will solve

Usually, the abstract is written last, ie. after writing the other sections and you know the key points to draw out from these sections. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in the report to decide whether it is relevant to their purposes.

Introduction

- Discusses the background and sets the context

- Introduces the topic, significance of the problem, and the purpose of research

- Gives the scope ie shows what it includes and excludes

In the introduction, write about what motivates your project, what makes it interesting, what questions do you aim to answer by doing your project. The introduction lays the foundation for understanding the research problem and should be written in a way that leads the reader from the general subject area of the topic to the particular topic of research.

Literature Review

- Helps to gain an understanding of the existing research in that topic

- To develop on your own ideas and build your ideas based on the existing knowledge

- Prevents duplication of the research done by others

Search the existing literature for information. Identify the data pertinent to your topic. Review, extract the relevant information for eg how the study was conducted and the findings. Summarise the information. Write what is already known about the topic and what do the sources that you have reviewed say. Identify conflicts in previous studies, open questions, or gaps that may exist. If you are doing

- Case study - look for background information and if any similar case studies have been done before.

- Literature review - find out from literature, what is the background to the questions that you are looking into

- Site visit - use the literature review to read up and prepare good questions before hand.

- Survey - find out if similar surveys have been done before and what did they find?

Keep a record of the source details of any information you want to use in your report so that you can reference them accurately.

Methodology

Methodology is the approach that you take to gather data and arrive at the recommendation(s). Choose a method that is appropriate for the research topic and explain it in detail.

In this section, address the following: a) How the data was collected b) How it was analysed and c) Explain or justify why a particular method was chosen.

Usually, the methodology is written in the past tense and can be in the passive voice. Some examples of the different methods that you can use to gather data are given below. The data collected provides evidence to build your arguments. Collect data, integrate the findings and perspectives from different studies and add your own analysis of its feasibility.

- Explore the literature/news/internet sources to know the topic in depth

- Give a description of how you selected the literature for your project

- Compare the studies, and highlight the findings, gaps or limitations.

- An in-depth, detailed examination of specific cases within a real-world context.

- Enables you to examine the data within a specific context.

- Examine a well defined case to identify the essential factors, process and relationship.

- Write the case description, the context and the process involved.

- Make sense of the evidence in the case(s) to answer the research question

- Gather data from a predefined group of respondents by asking relevant questions

- Can be conducted in person or online

- Why you chose this method (questionnaires, focus group, experimental procedure, etc)

- How you carried out the survey. Include techniques and any equipment you used

- If there were participants in your research, who were they? How did you select them and how may were there?

- How the survey questions address the different aspects of the research question

- Analyse the technology / policy approaches by visiting the required sites

- Make a detailed report on its features and your understanding of it

Results and Analysis

- Present the results of the study. You may consider visualising the results in tables and graphs, graphics etc.

- Analyse the results to obtain answer to the research question.

- Provide an analysis of the technical and financial feasibility, social acceptability etc

Discussion, Limitation(s) and Implication(s)

- Discuss your interpretations of the analysis and the significance of your findings

- Explain any new understanding or insights that emerged as a result of your research

- Consider the different perspectives (social, economic and environmental)in the discussion

- Explain the limitation(s)

- Explain how could what you found be used to make a difference for sustainability

Conclusion and Recommendations

- Summarise the significance and outcome of the study highlighting the key points.

- Come up with alternatives and propose specific actions based on the alternatives

- Describe the result or improvement it would achieve

- Explain how it will be implemented

Recommendations should have an innovative approach and should be feasible. It should make a significant difference in solving the issue under discussion.

- List the sources you have referred to in your writing

- Use the recommended citation style consistently in your report

Appendix (if necessary/any)

Include any material relating to the report and research that does not fit in the body of the report, in the appendix. For example, you may include survey questionnaire and results in the appendix.

- << Previous: Structure of a report

- Next: Structure of report (Site visit) >>

- Last Updated: Jan 12, 2024 11:52 AM

- URL: https://libguides.ntu.edu.sg/report-writing

You are expected to comply with University policies and guidelines namely, Appropriate Use of Information Resources Policy , IT Usage Policy and Social Media Policy . Users will be personally liable for any infringement of Copyright and Licensing laws. Unless otherwise stated, all guide content is licensed by CC BY-NC 4.0 .

Study Design 101: Case Report

- Case Report

- Case Control Study

- Cohort Study

- Randomized Controlled Trial

- Practice Guideline

- Systematic Review

- Meta-Analysis

- Helpful Formulas

- Finding Specific Study Types

- Case Reports

An article that describes and interprets an individual case, often written in the form of a detailed story. Case reports often describe:

- Unique cases that cannot be explained by known diseases or syndromes

- Cases that show an important variation of a disease or condition

- Cases that show unexpected events that may yield new or useful information

- Cases in which one patient has two or more unexpected diseases or disorders

Case reports are considered the lowest level of evidence, but they are also the first line of evidence, because they are where new issues and ideas emerge. This is why they form the base of our pyramid. A good case report will be clear about the importance of the observation being reported.

If multiple case reports show something similar, the next step might be a case-control study to determine if there is a relationship between the relevant variables.

- Can help in the identification of new trends or diseases

- Can help detect new drug side effects and potential uses (adverse or beneficial)

- Educational - a way of sharing lessons learned

- Identifies rare manifestations of a disease

Disadvantages

- Cases may not be generalizable

- Not based on systematic studies

- Causes or associations may have other explanations

- Can be seen as emphasizing the bizarre or focusing on misleading elements

Design pitfalls to look out for

The patient should be described in detail, allowing others to identify patients with similar characteristics.

Does the case report provide information about the patient's age, sex, ethnicity, race, employment status, social situation, medical history, diagnosis, prognosis, previous treatments, past and current diagnostic test results, medications, psychological tests, clinical and functional assessments, and current intervention?

Case reports should include carefully recorded, unbiased observations.

Does the case report include measurements and/or recorded observations of the case? Does it show a bias?

Case reports should explore and infer, not confirm, deduce, or prove. They cannot demonstrate causality or argue for the adoption of a new treatment approach.

Does the case report present a hypothesis that can be confirmed by another type of study?

Fictitious Example

A physician treated a young and otherwise healthy patient who came to her office reporting numbness all over her body. The physician could not determine any reason for this numbness and had never seen anything like it. After taking an extensive history the physician discovered that the patient had recently been to the beach for a vacation and had used a very new type of spray sunscreen. The patient had stored the sunscreen in her cooler at the beach because she liked the feel of the cool spray in the hot sun. The physician suspected that the spray sunscreen had undergone a chemical reaction from the coldness which caused the numbness. She also suspected that because this is a new type of sunscreen other physicians may soon be seeing patients with this numbness.

The physician wrote up a case report describing how the numbness presented, how and why she concluded it was the spray sunscreen, and how she treated the patient. Later, when other doctors began seeing patients with this numbness, they found this case report helpful as a starting point in treating their patients.

Real-life Examples

Hymes KB. Cheung T. Greene JB. Prose NS. Marcus A. Ballard H. William DC. Laubenstein LJ. (1981). Kaposi's sarcoma in homosexual men-a report of eight cases. Lancet. 2 (8247),598-600.

This case report was published by eight physicians in New York city who had unexpectedly seen eight male patients with Kaposi's sarcoma (KS). Prior to this, KS was very rare in the U.S. and occurred primarily in the lower extremities of older patients. These cases were decades younger, had generalized KS, and a much lower rate of survival. This was before the discovery of HIV or the use of the term AIDS and this case report was one of the first published items about AIDS patients.

Wu, E. B., & Sung, J. J. Y. (2003). Haemorrhagic-fever-like changes and normal chest radiograph in a doctor with SARS. Lancet, 361 (9368), 1520-1521.

This case report is written by the patient, a physician who contracted SARS, and his colleague who treated him, during the 2003 outbreak of SARS in Hong Kong. They describe how the disease progressed in Dr. Wu and based on Dr. Wu's case, advised that a chest CT showed hidden pneumonic changes and facilitate a rapid diagnosis.

Related Terms

Case Series

A report about a small group of similar cases.

Preplanned Case-Observation

A case in which symptoms are elicited to study disease mechanisms. (Ex. Having a patient sleep in a lab to do brain imaging for a sleep disorder).

Now test yourself!

1. Case studies are not considered evidence-based even though the authors have studied the case in great depth.

2. When are Case reports most useful?

When you encounter common cases and need more information When new symptoms or outcomes are unidentified When developing practice guidelines When the population being studied is very large

Evidence Pyramid - Navigation

- Meta- Analysis

- << Previous: Welcome to Study Design 101

- Next: Case Control Study >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 10:59 AM

- URL: https://guides.himmelfarb.gwu.edu/studydesign101

- Himmelfarb Intranet

- Privacy Notice

- Terms of Use

- GW is committed to digital accessibility. If you experience a barrier that affects your ability to access content on this page, let us know via the Accessibility Feedback Form .

- Himmelfarb Health Sciences Library

- 2300 Eye St., NW, Washington, DC 20037

- Phone: (202) 994-2850

- [email protected]

- https://himmelfarb.gwu.edu

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

Definition and Introduction

Case analysis is a problem-based teaching and learning method that involves critically analyzing complex scenarios within an organizational setting for the purpose of placing the student in a “real world” situation and applying reflection and critical thinking skills to contemplate appropriate solutions, decisions, or recommended courses of action. It is considered a more effective teaching technique than in-class role playing or simulation activities. The analytical process is often guided by questions provided by the instructor that ask students to contemplate relationships between the facts and critical incidents described in the case.

Cases generally include both descriptive and statistical elements and rely on students applying abductive reasoning to develop and argue for preferred or best outcomes [i.e., case scenarios rarely have a single correct or perfect answer based on the evidence provided]. Rather than emphasizing theories or concepts, case analysis assignments emphasize building a bridge of relevancy between abstract thinking and practical application and, by so doing, teaches the value of both within a specific area of professional practice.

Given this, the purpose of a case analysis paper is to present a structured and logically organized format for analyzing the case situation. It can be assigned to students individually or as a small group assignment and it may include an in-class presentation component. Case analysis is predominately taught in economics and business-related courses, but it is also a method of teaching and learning found in other applied social sciences disciplines, such as, social work, public relations, education, journalism, and public administration.

Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook: A Student's Guide . Revised Edition. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Publishing, 2018; Christoph Rasche and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Analysis . Writing Center, Baruch College; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

How to Approach Writing a Case Analysis Paper

The organization and structure of a case analysis paper can vary depending on the organizational setting, the situation, and how your professor wants you to approach the assignment. Nevertheless, preparing to write a case analysis paper involves several important steps. As Hawes notes, a case analysis assignment “...is useful in developing the ability to get to the heart of a problem, analyze it thoroughly, and to indicate the appropriate solution as well as how it should be implemented” [p.48]. This statement encapsulates how you should approach preparing to write a case analysis paper.

Before you begin to write your paper, consider the following analytical procedures:

- Review the case to get an overview of the situation . A case can be only a few pages in length, however, it is most often very lengthy and contains a significant amount of detailed background information and statistics, with multilayered descriptions of the scenario, the roles and behaviors of various stakeholder groups, and situational events. Therefore, a quick reading of the case will help you gain an overall sense of the situation and illuminate the types of issues and problems that you will need to address in your paper. If your professor has provided questions intended to help frame your analysis, use them to guide your initial reading of the case.

- Read the case thoroughly . After gaining a general overview of the case, carefully read the content again with the purpose of understanding key circumstances, events, and behaviors among stakeholder groups. Look for information or data that appears contradictory, extraneous, or misleading. At this point, you should be taking notes as you read because this will help you develop a general outline of your paper. The aim is to obtain a complete understanding of the situation so that you can begin contemplating tentative answers to any questions your professor has provided or, if they have not provided, developing answers to your own questions about the case scenario and its connection to the course readings,lectures, and class discussions.

- Determine key stakeholder groups, issues, and events and the relationships they all have to each other . As you analyze the content, pay particular attention to identifying individuals, groups, or organizations described in the case and identify evidence of any problems or issues of concern that impact the situation in a negative way. Other things to look for include identifying any assumptions being made by or about each stakeholder, potential biased explanations or actions, explicit demands or ultimatums , and the underlying concerns that motivate these behaviors among stakeholders. The goal at this stage is to develop a comprehensive understanding of the situational and behavioral dynamics of the case and the explicit and implicit consequences of each of these actions.

- Identify the core problems . The next step in most case analysis assignments is to discern what the core [i.e., most damaging, detrimental, injurious] problems are within the organizational setting and to determine their implications. The purpose at this stage of preparing to write your analysis paper is to distinguish between the symptoms of core problems and the core problems themselves and to decide which of these must be addressed immediately and which problems do not appear critical but may escalate over time. Identify evidence from the case to support your decisions by determining what information or data is essential to addressing the core problems and what information is not relevant or is misleading.

- Explore alternative solutions . As noted, case analysis scenarios rarely have only one correct answer. Therefore, it is important to keep in mind that the process of analyzing the case and diagnosing core problems, while based on evidence, is a subjective process open to various avenues of interpretation. This means that you must consider alternative solutions or courses of action by critically examining strengths and weaknesses, risk factors, and the differences between short and long-term solutions. For each possible solution or course of action, consider the consequences they may have related to their implementation and how these recommendations might lead to new problems. Also, consider thinking about your recommended solutions or courses of action in relation to issues of fairness, equity, and inclusion.

- Decide on a final set of recommendations . The last stage in preparing to write a case analysis paper is to assert an opinion or viewpoint about the recommendations needed to help resolve the core problems as you see them and to make a persuasive argument for supporting this point of view. Prepare a clear rationale for your recommendations based on examining each element of your analysis. Anticipate possible obstacles that could derail their implementation. Consider any counter-arguments that could be made concerning the validity of your recommended actions. Finally, describe a set of criteria and measurable indicators that could be applied to evaluating the effectiveness of your implementation plan.

Use these steps as the framework for writing your paper. Remember that the more detailed you are in taking notes as you critically examine each element of the case, the more information you will have to draw from when you begin to write. This will save you time.

NOTE : If the process of preparing to write a case analysis paper is assigned as a student group project, consider having each member of the group analyze a specific element of the case, including drafting answers to the corresponding questions used by your professor to frame the analysis. This will help make the analytical process more efficient and ensure that the distribution of work is equitable. This can also facilitate who is responsible for drafting each part of the final case analysis paper and, if applicable, the in-class presentation.

Framework for Case Analysis . College of Management. University of Massachusetts; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Rasche, Christoph and Achim Seisreiner. Guidelines for Business Case Analysis . University of Potsdam; Writing a Case Study Analysis . University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center; Van Ness, Raymond K. A Guide to Case Analysis . School of Business. State University of New York, Albany; Writing a Case Analysis . Business School, University of New South Wales.

Structure and Writing Style

A case analysis paper should be detailed, concise, persuasive, clearly written, and professional in tone and in the use of language . As with other forms of college-level academic writing, declarative statements that convey information, provide a fact, or offer an explanation or any recommended courses of action should be based on evidence. If allowed by your professor, any external sources used to support your analysis, such as course readings, should be properly cited under a list of references. The organization and structure of case analysis papers can vary depending on your professor’s preferred format, but its structure generally follows the steps used for analyzing the case.

Introduction

The introduction should provide a succinct but thorough descriptive overview of the main facts, issues, and core problems of the case . The introduction should also include a brief summary of the most relevant details about the situation and organizational setting. This includes defining the theoretical framework or conceptual model on which any questions were used to frame your analysis.

Following the rules of most college-level research papers, the introduction should then inform the reader how the paper will be organized. This includes describing the major sections of the paper and the order in which they will be presented. Unless you are told to do so by your professor, you do not need to preview your final recommendations in the introduction. U nlike most college-level research papers , the introduction does not include a statement about the significance of your findings because a case analysis assignment does not involve contributing new knowledge about a research problem.

Background Analysis

Background analysis can vary depending on any guiding questions provided by your professor and the underlying concept or theory that the case is based upon. In general, however, this section of your paper should focus on:

- Providing an overarching analysis of problems identified from the case scenario, including identifying events that stakeholders find challenging or troublesome,

- Identifying assumptions made by each stakeholder and any apparent biases they may exhibit,

- Describing any demands or claims made by or forced upon key stakeholders, and

- Highlighting any issues of concern or complaints expressed by stakeholders in response to those demands or claims.

These aspects of the case are often in the form of behavioral responses expressed by individuals or groups within the organizational setting. However, note that problems in a case situation can also be reflected in data [or the lack thereof] and in the decision-making, operational, cultural, or institutional structure of the organization. Additionally, demands or claims can be either internal and external to the organization [e.g., a case analysis involving a president considering arms sales to Saudi Arabia could include managing internal demands from White House advisors as well as demands from members of Congress].

Throughout this section, present all relevant evidence from the case that supports your analysis. Do not simply claim there is a problem, an assumption, a demand, or a concern; tell the reader what part of the case informed how you identified these background elements.

Identification of Problems

In most case analysis assignments, there are problems, and then there are problems . Each problem can reflect a multitude of underlying symptoms that are detrimental to the interests of the organization. The purpose of identifying problems is to teach students how to differentiate between problems that vary in severity, impact, and relative importance. Given this, problems can be described in three general forms: those that must be addressed immediately, those that should be addressed but the impact is not severe, and those that do not require immediate attention and can be set aside for the time being.

All of the problems you identify from the case should be identified in this section of your paper, with a description based on evidence explaining the problem variances. If the assignment asks you to conduct research to further support your assessment of the problems, include this in your explanation. Remember to cite those sources in a list of references. Use specific evidence from the case and apply appropriate concepts, theories, and models discussed in class or in relevant course readings to highlight and explain the key problems [or problem] that you believe must be solved immediately and describe the underlying symptoms and why they are so critical.

Alternative Solutions

This section is where you provide specific, realistic, and evidence-based solutions to the problems you have identified and make recommendations about how to alleviate the underlying symptomatic conditions impacting the organizational setting. For each solution, you must explain why it was chosen and provide clear evidence to support your reasoning. This can include, for example, course readings and class discussions as well as research resources, such as, books, journal articles, research reports, or government documents. In some cases, your professor may encourage you to include personal, anecdotal experiences as evidence to support why you chose a particular solution or set of solutions. Using anecdotal evidence helps promote reflective thinking about the process of determining what qualifies as a core problem and relevant solution .

Throughout this part of the paper, keep in mind the entire array of problems that must be addressed and describe in detail the solutions that might be implemented to resolve these problems.

Recommended Courses of Action

In some case analysis assignments, your professor may ask you to combine the alternative solutions section with your recommended courses of action. However, it is important to know the difference between the two. A solution refers to the answer to a problem. A course of action refers to a procedure or deliberate sequence of activities adopted to proactively confront a situation, often in the context of accomplishing a goal. In this context, proposed courses of action are based on your analysis of alternative solutions. Your description and justification for pursuing each course of action should represent the overall plan for implementing your recommendations.

For each course of action, you need to explain the rationale for your recommendation in a way that confronts challenges, explains risks, and anticipates any counter-arguments from stakeholders. Do this by considering the strengths and weaknesses of each course of action framed in relation to how the action is expected to resolve the core problems presented, the possible ways the action may affect remaining problems, and how the recommended action will be perceived by each stakeholder.

In addition, you should describe the criteria needed to measure how well the implementation of these actions is working and explain which individuals or groups are responsible for ensuring your recommendations are successful. In addition, always consider the law of unintended consequences. Outline difficulties that may arise in implementing each course of action and describe how implementing the proposed courses of action [either individually or collectively] may lead to new problems [both large and small].

Throughout this section, you must consider the costs and benefits of recommending your courses of action in relation to uncertainties or missing information and the negative consequences of success.

The conclusion should be brief and introspective. Unlike a research paper, the conclusion in a case analysis paper does not include a summary of key findings and their significance, a statement about how the study contributed to existing knowledge, or indicate opportunities for future research.

Begin by synthesizing the core problems presented in the case and the relevance of your recommended solutions. This can include an explanation of what you have learned about the case in the context of your answers to the questions provided by your professor. The conclusion is also where you link what you learned from analyzing the case with the course readings or class discussions. This can further demonstrate your understanding of the relationships between the practical case situation and the theoretical and abstract content of assigned readings and other course content.

Problems to Avoid

The literature on case analysis assignments often includes examples of difficulties students have with applying methods of critical analysis and effectively reporting the results of their assessment of the situation. A common reason cited by scholars is that the application of this type of teaching and learning method is limited to applied fields of social and behavioral sciences and, as a result, writing a case analysis paper can be unfamiliar to most students entering college.

After you have drafted your paper, proofread the narrative flow and revise any of these common errors:

- Unnecessary detail in the background section . The background section should highlight the essential elements of the case based on your analysis. Focus on summarizing the facts and highlighting the key factors that become relevant in the other sections of the paper by eliminating any unnecessary information.

- Analysis relies too much on opinion . Your analysis is interpretive, but the narrative must be connected clearly to evidence from the case and any models and theories discussed in class or in course readings. Any positions or arguments you make should be supported by evidence.

- Analysis does not focus on the most important elements of the case . Your paper should provide a thorough overview of the case. However, the analysis should focus on providing evidence about what you identify are the key events, stakeholders, issues, and problems. Emphasize what you identify as the most critical aspects of the case to be developed throughout your analysis. Be thorough but succinct.

- Writing is too descriptive . A paper with too much descriptive information detracts from your analysis of the complexities of the case situation. Questions about what happened, where, when, and by whom should only be included as essential information leading to your examination of questions related to why, how, and for what purpose.

- Inadequate definition of a core problem and associated symptoms . A common error found in case analysis papers is recommending a solution or course of action without adequately defining or demonstrating that you understand the problem. Make sure you have clearly described the problem and its impact and scope within the organizational setting. Ensure that you have adequately described the root causes w hen describing the symptoms of the problem.

- Recommendations lack specificity . Identify any use of vague statements and indeterminate terminology, such as, “A particular experience” or “a large increase to the budget.” These statements cannot be measured and, as a result, there is no way to evaluate their successful implementation. Provide specific data and use direct language in describing recommended actions.

- Unrealistic, exaggerated, or unattainable recommendations . Review your recommendations to ensure that they are based on the situational facts of the case. Your recommended solutions and courses of action must be based on realistic assumptions and fit within the constraints of the situation. Also note that the case scenario has already happened, therefore, any speculation or arguments about what could have occurred if the circumstances were different should be revised or eliminated.

Bee, Lian Song et al. "Business Students' Perspectives on Case Method Coaching for Problem-Based Learning: Impacts on Student Engagement and Learning Performance in Higher Education." Education & Training 64 (2022): 416-432; The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Georgallis, Panikos and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching using Case-Based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; Hawes, Jon M. "Teaching is Not Telling: The Case Method as a Form of Interactive Learning." Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education 5 (Winter 2004): 47-54; Georgallis, Panikos, and Kayleigh Bruijn. "Sustainability Teaching Using Case-based Debates." Journal of International Education in Business 15 (2022): 147-163; .Dean, Kathy Lund and Charles J. Fornaciari. "How to Create and Use Experiential Case-Based Exercises in a Management Classroom." Journal of Management Education 26 (October 2002): 586-603; Klebba, Joanne M. and Janet G. Hamilton. "Structured Case Analysis: Developing Critical Thinking Skills in a Marketing Case Course." Journal of Marketing Education 29 (August 2007): 132-137, 139; Klein, Norman. "The Case Discussion Method Revisited: Some Questions about Student Skills." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 30-32; Mukherjee, Arup. "Effective Use of In-Class Mini Case Analysis for Discovery Learning in an Undergraduate MIS Course." The Journal of Computer Information Systems 40 (Spring 2000): 15-23; Pessoa, Silviaet al. "Scaffolding the Case Analysis in an Organizational Behavior Course: Making Analytical Language Explicit." Journal of Management Education 46 (2022): 226-251: Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Schweitzer, Karen. "How to Write and Format a Business Case Study." ThoughtCo. https://www.thoughtco.com/how-to-write-and-format-a-business-case-study-466324 (accessed December 5, 2022); Reddy, C. D. "Teaching Research Methodology: Everything's a Case." Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 18 (December 2020): 178-188; Volpe, Guglielmo. "Case Teaching in Economics: History, Practice and Evidence." Cogent Economics and Finance 3 (December 2015). doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/23322039.2015.1120977.

Writing Tip

Ca se Study and Case Analysis Are Not the Same!

Confusion often exists between what it means to write a paper that uses a case study research design and writing a paper that analyzes a case; they are two different types of approaches to learning in the social and behavioral sciences. Professors as well as educational researchers contribute to this confusion because they often use the term "case study" when describing the subject of analysis for a case analysis paper. But you are not studying a case for the purpose of generating a comprehensive, multi-faceted understanding of a research problem. R ather, you are critically analyzing a specific scenario to argue logically for recommended solutions and courses of action that lead to optimal outcomes applicable to professional practice.

To avoid any confusion, here are twelve characteristics that delineate the differences between writing a paper using the case study research method and writing a case analysis paper:

- Case study is a method of in-depth research and rigorous inquiry ; case analysis is a reliable method of teaching and learning . A case study is a modality of research that investigates a phenomenon for the purpose of creating new knowledge, solving a problem, or testing a hypothesis using empirical evidence derived from the case being studied. Often, the results are used to generalize about a larger population or within a wider context. The writing adheres to the traditional standards of a scholarly research study. A case analysis is a pedagogical tool used to teach students how to reflect and think critically about a practical, real-life problem in an organizational setting.

- The researcher is responsible for identifying the case to study; a case analysis is assigned by your professor . As the researcher, you choose the case study to investigate in support of obtaining new knowledge and understanding about the research problem. The case in a case analysis assignment is almost always provided, and sometimes written, by your professor and either given to every student in class to analyze individually or to a small group of students, or students select a case to analyze from a predetermined list.

- A case study is indeterminate and boundless; a case analysis is predetermined and confined . A case study can be almost anything [see item 9 below] as long as it relates directly to examining the research problem. This relationship is the only limit to what a researcher can choose as the subject of their case study. The content of a case analysis is determined by your professor and its parameters are well-defined and limited to elucidating insights of practical value applied to practice.

- Case study is fact-based and describes actual events or situations; case analysis can be entirely fictional or adapted from an actual situation . The entire content of a case study must be grounded in reality to be a valid subject of investigation in an empirical research study. A case analysis only needs to set the stage for critically examining a situation in practice and, therefore, can be entirely fictional or adapted, all or in-part, from an actual situation.

- Research using a case study method must adhere to principles of intellectual honesty and academic integrity; a case analysis scenario can include misleading or false information . A case study paper must report research objectively and factually to ensure that any findings are understood to be logically correct and trustworthy. A case analysis scenario may include misleading or false information intended to deliberately distract from the central issues of the case. The purpose is to teach students how to sort through conflicting or useless information in order to come up with the preferred solution. Any use of misleading or false information in academic research is considered unethical.

- Case study is linked to a research problem; case analysis is linked to a practical situation or scenario . In the social sciences, the subject of an investigation is most often framed as a problem that must be researched in order to generate new knowledge leading to a solution. Case analysis narratives are grounded in real life scenarios for the purpose of examining the realities of decision-making behavior and processes within organizational settings. A case analysis assignments include a problem or set of problems to be analyzed. However, the goal is centered around the act of identifying and evaluating courses of action leading to best possible outcomes.

- The purpose of a case study is to create new knowledge through research; the purpose of a case analysis is to teach new understanding . Case studies are a choice of methodological design intended to create new knowledge about resolving a research problem. A case analysis is a mode of teaching and learning intended to create new understanding and an awareness of uncertainty applied to practice through acts of critical thinking and reflection.

- A case study seeks to identify the best possible solution to a research problem; case analysis can have an indeterminate set of solutions or outcomes . Your role in studying a case is to discover the most logical, evidence-based ways to address a research problem. A case analysis assignment rarely has a single correct answer because one of the goals is to force students to confront the real life dynamics of uncertainly, ambiguity, and missing or conflicting information within professional practice. Under these conditions, a perfect outcome or solution almost never exists.

- Case study is unbounded and relies on gathering external information; case analysis is a self-contained subject of analysis . The scope of a case study chosen as a method of research is bounded. However, the researcher is free to gather whatever information and data is necessary to investigate its relevance to understanding the research problem. For a case analysis assignment, your professor will often ask you to examine solutions or recommended courses of action based solely on facts and information from the case.

- Case study can be a person, place, object, issue, event, condition, or phenomenon; a case analysis is a carefully constructed synopsis of events, situations, and behaviors . The research problem dictates the type of case being studied and, therefore, the design can encompass almost anything tangible as long as it fulfills the objective of generating new knowledge and understanding. A case analysis is in the form of a narrative containing descriptions of facts, situations, processes, rules, and behaviors within a particular setting and under a specific set of circumstances.

- Case study can represent an open-ended subject of inquiry; a case analysis is a narrative about something that has happened in the past . A case study is not restricted by time and can encompass an event or issue with no temporal limit or end. For example, the current war in Ukraine can be used as a case study of how medical personnel help civilians during a large military conflict, even though circumstances around this event are still evolving. A case analysis can be used to elicit critical thinking about current or future situations in practice, but the case itself is a narrative about something finite and that has taken place in the past.

- Multiple case studies can be used in a research study; case analysis involves examining a single scenario . Case study research can use two or more cases to examine a problem, often for the purpose of conducting a comparative investigation intended to discover hidden relationships, document emerging trends, or determine variations among different examples. A case analysis assignment typically describes a stand-alone, self-contained situation and any comparisons among cases are conducted during in-class discussions and/or student presentations.

The Case Analysis . Fred Meijer Center for Writing and Michigan Authors. Grand Valley State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Ramsey, V. J. and L. D. Dodge. "Case Analysis: A Structured Approach." Exchange: The Organizational Behavior Teaching Journal 6 (November 1981): 27-29; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2017; Crowe, Sarah et al. “The Case Study Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 11 (2011): doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-11-100; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 4th edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1994.

- << Previous: Reviewing Collected Works

- Next: Writing a Case Study >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

Case Report vs Cross-Sectional Study: A Simple Explanation

A case report is the description of the clinical story of a single patient. A cross-sectional study involves a group of participants on which data is collected at a single point in time to investigate the relationship between a certain exposure and an outcome.

Here’s a table that summarizes the relationship between a case report and a cross-sectional study:

Further reading

- Case Report: A Beginner’s Guide with Examples

- Case Report vs Case-Control Study

- Cohort vs Cross-Sectional Study

- How to Identify Different Types of Cohort Studies?

- Matched Pairs Design

- Randomized Block Design

Case Study vs. Survey

What's the difference.

Case studies and surveys are both research methods used in various fields to gather information and insights. However, they differ in their approach and purpose. A case study involves an in-depth analysis of a specific individual, group, or situation, aiming to understand the complexities and unique aspects of the subject. It often involves collecting qualitative data through interviews, observations, and document analysis. On the other hand, a survey is a structured data collection method that involves gathering information from a larger sample size through standardized questionnaires. Surveys are typically used to collect quantitative data and provide a broader perspective on a particular topic or population. While case studies provide rich and detailed information, surveys offer a more generalizable and statistical overview.

Further Detail

Introduction.

When conducting research, there are various methods available to gather data and analyze it. Two commonly used methods are case study and survey. Both approaches have their own unique attributes and can be valuable in different research contexts. In this article, we will explore the characteristics of case study and survey, highlighting their strengths and limitations.

A case study is an in-depth investigation of a particular individual, group, or phenomenon. It involves collecting detailed information about the subject of study through various sources such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. Case studies are often used in social sciences, psychology, and business research to gain a deep understanding of complex issues.

One of the key attributes of a case study is its ability to provide rich and detailed data. Researchers can gather extensive information about the subject, including their background, experiences, and perspectives. This depth of data allows for a comprehensive analysis and interpretation of the case, providing valuable insights into the phenomenon under investigation.

Furthermore, case studies are particularly useful when studying rare or unique cases. Since case studies focus on specific individuals or groups, they can shed light on situations that are not easily replicated or observed in larger populations. This makes case studies valuable in exploring complex and nuanced phenomena that may not be easily captured through other research methods.

However, it is important to note that case studies have certain limitations. Due to their in-depth nature, case studies are often time-consuming and resource-intensive. Researchers need to invest significant effort in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. Additionally, the findings of a case study may not be easily generalized to larger populations, as the focus is on a specific case rather than a representative sample.

Despite these limitations, case studies offer a unique opportunity to explore complex issues in real-life contexts. They provide a detailed understanding of individual experiences and can generate hypotheses for further research.

A survey is a research method that involves collecting data from a sample of individuals through a structured questionnaire or interview. Surveys are widely used in social sciences, market research, and public opinion studies to gather information about a larger population. They aim to provide a snapshot of people's opinions, attitudes, behaviors, or characteristics.

One of the main advantages of surveys is their ability to collect data from a large number of respondents. By reaching out to a representative sample, researchers can generalize the findings to a larger population. Surveys also allow for efficient data collection, as questionnaires can be distributed electronically or in person, making it easier to gather a wide range of responses in a relatively short period.

Moreover, surveys offer a structured approach to data collection, ensuring consistency in the questions asked and the response options provided. This allows for easy comparison and analysis of the data, making surveys suitable for quantitative research. Surveys can also be conducted anonymously, which can encourage respondents to provide honest and unbiased answers, particularly when sensitive topics are being explored.

However, surveys also have their limitations. One of the challenges is the potential for response bias. Respondents may provide inaccurate or socially desirable answers, leading to biased results. Additionally, surveys often rely on self-reported data, which may be subject to memory recall errors or misinterpretation of questions. Researchers need to carefully design the survey instrument and consider potential biases to ensure the validity and reliability of the data collected.

Furthermore, surveys may not capture the complexity and depth of individual experiences. They provide a snapshot of people's opinions or behaviors at a specific point in time, but may not uncover the underlying reasons or motivations behind those responses. Surveys also rely on predetermined response options, limiting the range of possible answers and potentially overlooking important nuances.

Case studies and surveys are both valuable research methods, each with its own strengths and limitations. Case studies offer in-depth insights into specific cases, providing rich and detailed data. They are particularly useful for exploring complex and unique phenomena. On the other hand, surveys allow for efficient data collection from a large number of respondents, enabling generalization to larger populations. They provide structured and quantifiable data, making them suitable for statistical analysis.

Ultimately, the choice between case study and survey depends on the research objectives, the nature of the research question, and the available resources. Researchers need to carefully consider the attributes of each method and select the most appropriate approach to gather and analyze data effectively.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

A case report is a detailed report of the diagnosis, treatment, response to treatment, and follow-up after treatment of an individual patient. A case series is group of case reports involving patients who were given similar treatment. Case reports and case series usually contain demographic information about the patient(s), for example, age, gender, ethnic origin.

When information on more than three patients is included, the case series is considered to be a systematic investigation designed to contribute to generalizable knowledge (i.e., research ), and therefore submission is required to the IRB.

For all case reports and case series, a signed HIPAA authorization should be obtained from the patients or their legally authorized representatives for the use and disclosure of their Protected Health Information. The only exception to the requirement for obtaining authorization is if the author of a case report or case series believes that the information is not identifiable; in this case, the author must consult with the Privacy Officer at Boston Medical Center ( [email protected] ) or the HIPAA Privacy Officer of Boston University ( [email protected] ) to seek an expert opinion about the magnitude of the risk of identifying an individual.

For case reports or case series containing more than three patients, the HIPAA authorization should be part of the consent form that is reviewed by the IRB.

For case reports or case series containing three or fewer patients, authors should prepare an authorization form using the following templates and arrange for review as indicated below. The red text in the template should be customized for the specific case report or case series. Please note that for deceased patients, authorization must be obtained from the personal representative, who is the administrator or executor of the patient’s estate.

- Boston Medical Center ( BMC Case Report HIPAA Authorization Template ) – review by the Privacy Officer at Boston Medical Center ( [email protected] ); a copy of the authorization must be filed in each patient’s medical record.

- Goldman School of Dental Medicine ( GSDM Case Report HIPAA Authorization Template ) – review by the HIPAA Privacy Officer of Boston University ( [email protected] )

- Open access

- Published: 05 April 2024

The clinical trial activation process: a case study of an Italian public hospital

- Carolina Pelazza ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7875-3710 1 ,

- Marta Betti 1 ,

- Francesca Marengo 1 ,

- Annalisa Roveta 2 &

- Antonio Maconi 1

Trials volume 25 , Article number: 240 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Background/aims

In order to make the centers more attractive to trial sponsors, in recent years, some research institutions around the world have pursued projects to reorganize the pathway of trial activation, developing new organizational models to improve the activation process and reduce its times.

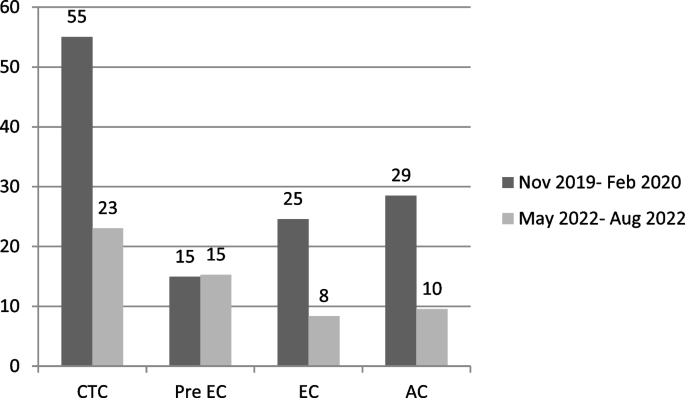

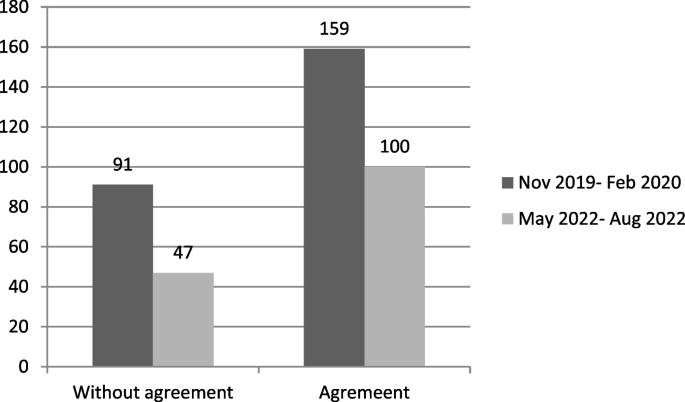

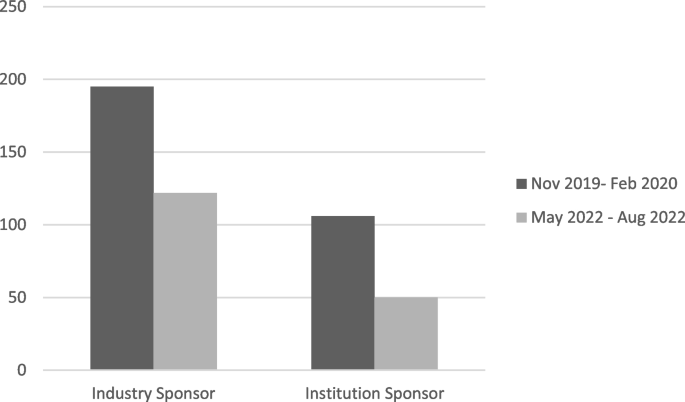

This study aims at analyzing and reorganizing the start-up phase of trials conducted at the Research and Innovation Department (DAIRI) of the Public Hospital of Alessandria (Italy).