- Search Menu

- Advance Articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Why Submit?

- About Human Communication Research

- About International Communication Association

- Editorial Board

- Advertising & Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

“what theory are you using”, theory is ubiquitous in published communication scholarship, what is theory anyway, is theory really necessary, the chicken or the egg: theory or data first, will any theory do, what is a theoretical contribution, theoretical bandwidth, what are the benefits of theory, the current state of communication theory, looking forward, data availability, conflicts of interest.

- < Previous

The role of theory in researching and understanding human communication

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Timothy R Levine, David M Markowitz, The role of theory in researching and understanding human communication, Human Communication Research , Volume 50, Issue 2, April 2024, Pages 154–161, https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad037

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Communication is a theory-driven discipline, but does it always need to be? This article raises questions related to the role of theory in communication science, with the goal of providing a thoughtful discussion about what theory is, why theory is (or is not) important, the role of exploration in theory development, what constitutes a theoretical contribution, and the current state of theory in the field. We describe communication researchers’ interest with theory by assessing the number of articles in the past decade of research that mention theory (nearly 80% of papers have attended to theory in some way). This article concludes with a forward-looking view of how scholars might think about theory in their work, why exploratory research should be valued more and not considered as conflicting with theory, and how conceptual clarity related to theoretical interests and contributions are imperative for human communication research.

Theory looms large in the practice of human communication scholarship. College-level textbooks on various communication topics describe relevant theories to students enrolled in communication classes. In thesis and dissertation defenses, students are often asked, “What theory are you using?,” implying that they must apply at least one theory to ground their research and contribute to the field. In the peer-review process of academic journals, a perceived failure to be sufficiently theoretical can be grounds for rejection. Few, if any, modern communication scholars would embrace the labels of being “dust-bowl” or atheoretical. Surely, no serious communication scholar is genuinely and categorically against theory. Theory is undeniably a desirable “warm-fuzzy good thing” in modern academic culture ( Mook, 1983 ). Without it, the bedrock of communication and other social sciences is shaky and uncertain. No academic discipline could be built from a purely empirical foundation. Having theory—understanding the value it provides, what we gain by building and extending theory, and the contributions that a scholar can make to theory—is more complicated and nuanced, however. We interrogate these complications in this article.

This article addresses a broad set of questions about the past, present, and future role of theory in communication scholarship: What is theory? Do all scholarly contributions require theory? What does it mean to make a theoretical contribution? What does theory do for us? And, if we continue to accept theory as a scholarly imperative, what is the current state of theory in the field and where might communication theory go in the future? To address these questions, we follow and draw on important commentaries such as those of Chaffee and Berger (1987) , Slater and Gleason (2012) , and DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) , but we provide our own perspective. Unlike similar essays on communication theory, our goal is not to be prescriptive about how to do theory (e.g., how to create or even define theory), nor are we attempting to be pollyannish about the many accepted virtues of theory. Instead, a conversation about communication theory is advanced by asking questions that are hard to answer, interrogating some often-implicit presumptions about the role of theory in communication science, and raising some less obvious implications of theory. This article will succeed if it prompts deeper thought and discussion on the topic of communication theory across many areas of the field. We envision this being useful for early career communication scholars who are uncertain about what theory really is and why it matters, and a thoughtful commentary for seasoned communication researchers who may wrestle with theory development as they move forward in their established research programs.

In our experience, graduate students (and undergrads, junior faculty, visiting scholars, etc.) are frequently asked “what theory are you using?” when trying to position one’s work within communication science at large. This question raises many meta-theoretical issues relevant to this article. First, the question implies that theory is a prerequisite for scholarship. Later in this article, we will argue that this perspective is unfortunately limiting, and that there is a need for exploratory and pre-theoretical inquiry and data. Further, a relevant theory is not always available for each research interest. A better initial question, in our opinion, asks if there is a relevant theory to be tested, extended, or used. When no relevant theory exists, the lack of a theory should not preclude research nor publication. Advancing theory is undeniably valuable. Not all scholarly contributions, however, explicitly advance theory in ways that are recognized at the time they are written.

When a relevant theory or theories are available, follow-up questions might address how the theory is being engaged (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Is the theory being directly tested in a way that is informative about the merits of the theory? How is the theory being advanced? Is a boundary condition being explored or the scope being extended? Merely using a theory to inform a topic can provide valuable direction and insights, but using theory is less likely to push the theory and its related propositions forward. Making a theoretical contribution involves actually advancing the theory itself ( Slater & Gleason, 2012 ).

We opened by opining that communication scholarship is consumed with theory and that contributing to theory is a priority of the discipline. To descriptively demonstrate this extent of this interest, we evaluated over 10,000 full text communication articles across 26 journals that were published in the last decade (see Markowitz et al., 2021 ), in search of how often they focus on five key theory-related terms ( theory , theories , theoretical , theoretical contribution , theoretical contributions ). The top panel of Figure 1 represents the percentage of papers within each year that mentioned at least one of the five terms related to theory. On average, 79.1% (8,320 of 10,517) of articles mentioned one theory-related term, with a relatively stable distribution over time (see the bottom panel of Figure 1 for a breakdown by journal). Of the 60,727 times that one of the five theory-related terms appeared in the sample, over half were related to the word theory alone (55.1%; 33,462/60,727). A thematic review of these cases revealed that theory is used in a variety of ways by communication researchers. The word is attached to specific social scientific theories (e.g., Construal Level Theory, Social Identity Theory), the term is used abstractly to feign the appearance of theory (e.g., “message processing theory,” “organizational communication theory”), the word theory serves as sign-posts in academic papers (e.g., “in the theory section above”), and finally, the term attempts to mark one’s contributions (e.g., “has several implications for theory and research on selective exposure”). 1 Together, the ubiquity of theory and theory-related terms, we believe, stems from and reflects expectations for publishing norms that value theory in the field of communication.

The rate of mentioning theory in communication science articles.

Our findings align with those of Slater and Gleason (2012) who examined articles in three elite communication journals in 2008–2009. They report that a sizable number of articles advanced theories in at least one of several ways. They reported, for example, that 54% of the articles they examined in Journal of Communication , Human Communication Research , and Communication Research addressed boundary conditions, 40% expanded a theories range of application, 22% advanced a mechanism, and 12% revised a theory. Alternatively, theoretical contributions, such as creating a new theory, comparing theories, and synthesizing across theories, were less common occurring in only 8% of articles combined.

We note, however, that mentioning at least one theory-related term does not mean that the work counts as contributing to theory. Of course, deeply theoretical work mentions theory, but so too do articles that engage in a practice that might be called theoretical name dropping . Our concern is that if work must invoke theory to pass the peer-review process, then exploratory and pre-theoretical work might mention a theory or otherwise invoke theory-related words to appear theoretical and thereby get published. In line with this concern, DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) found that the use of words in articles specifically related to theory evaluation were infrequent. In a sample of articles from four top journals between 2013 and 2015 ( Journal of Communication , Human Communication Research , Communication Research , Communication Monographs ), just less than one-third of them included at least one theory evaluation word, and at least half of those were evaluating method rather than theory.

Deciding what is truly theory and what is not requires defining theory. This is where our conversation becomes more complex.

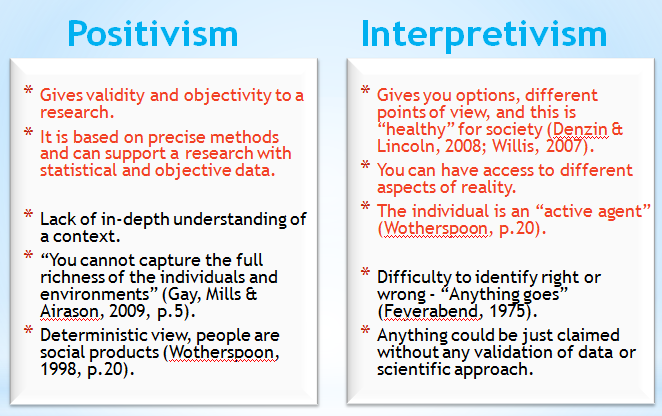

Despite the ubiquity of researchers’ focus on theory in published communication scholarship ( Figure 1 ), any thoughtful discussion of theory is fraught from the start due to unavoidable definitional ambiguity. There is no one definition of communication theory, nor can there be, nor should there be. As Miller and Nicholson (1976) rightfully suggested, definitions are not by their nature things that are correct or incorrect. Although undeniably circular, words mean what people mean by them, and people use words differently. This is especially true of theory. No one scholar, nor do a collection of scholars, become the definitive authority or arbitrator on what theory is and what it is not.

Definitional diversity in conceptually constituting theory is intellectually rich. In modern intellectual thought, different specialties and perspectives are welcomed and valued. The alternatives to diversity in theory definitions are hegemony and the demise of academic freedom. Treasured intellectual diversity, however, comes at the cost of potential misunderstanding stemming from people using the same word to mean so many different things (e.g., see Bem, 2003 ). Valuing intellectual diversity also requires us to abandon rigidity in prescribing fixed rules of doing communication theory and research.

Although there can be no one universal definition of theory, we agree with DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) that regardless of approaches, scholars should strive for greater clarity in what they mean by theory and their theoretical contribution. Diversity in definitions should be expected, but clarity and the thoughtful explication of one’s approach to theory should also be expected in any social science.

The lack of a shared definition for theory puts communication scholars in a Catch-22. Communication scholars value theory and appreciate approaching theory with rigor and clarity. Communication scholars also value intellectual diversity, and valuing diverse perspectives and approaches prevents scholars from imposing their own views of theory on other scholars. We find that an “anything goes” approach to theory intellectually troubling, but we are equally disturbed by imposing views and perspectives on other scholars. While we do not see an easy way out of this conundrum, we see much value in acknowledging that it exists and being thoughtful about how we balance conflicting values.

When scholars define theory, perhaps the most notable dimension of variability for the word theory is narrowness-breadth. At the wide end of this continuum, theory is synonymous with being minimally conceptional. Explicating a construct with a conceptual definition could constitute theory under some of the more expansive uses of the term (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Similarly, at the broad end of the continuum, theory can be synonymous with explanation. Efforts to answer “why” can count as theory. Sometimes, although we personally think this goes too far, simply adding the word theory to a topic or phenomenon (e.g., media theory, aggression theory, language theory) can pass as theory or at least provide the appearance of theory.

We prefer a much narrower use of the term, where theory can be considered a set of logically coherent and inter-related propositions or conjectures that (a) provide a unifying explanatory mechanism and (b) can be used to derive testable and falsifiable predictions . In this relatively narrow view, thinking conceptually or just explaining is not enough. Specifying a path model or set of mediated links might or might not count as theory. We note that some scholars may use the word theory even more restrictively, desiring to limit the term to formal axiomatic theories, and considering work to count as theoretical only if it conforms to a strict hypothetico-deductive depiction (or caricature) of science. Slater and Gleason (2012) provide a definition similar to ours. They see “the primary role of theory in communication science as the provision of explanation, of proposing causal processes, the explanation of ‘how’ and ‘under what circumstances’ in ways that result in empirically testable and falsifiable predictions” (p. 216).

The point here, however, is not to advocate for particular definition of theory but instead to argue that the efforts to impose a universal definition of theory is fundamentally misguided. Appreciation of theory requires recognition of the diversity of approaches to theory and a willingness to be respectful of approaches other than one’s own. The topic of theory needs to be approached with a cognizance of its diversity. Arguments about whose definition of theory is best will often be counterproductive. More constructive arguments will provide cogent reasons why an approach to defining theory is best for the intellectual endeavor to which it is applied.

Now that we have embraced the ambiguity inherent in defining theory, we next contemplate the necessity of theory. If we cannot provide a consensus definition of theory, then how can we demand or test it? Do (or would) we even know theory when we see it?

In our view, the necessity of theory varies according to the breadth of the term’s use. Being minimally conceptual is probably a prerequisite for making a scholarly contribution. After all, understanding what one is studying is typically either a prerequisite for, or a desired outcome of, advancing knowledge. If scholarly activities — such as concept explication, creating a new measure, description, observation, and hypothesis generation — indeed count (see Slater & Gleason, 2012 ), then requiring theory seems constructive.

One can imagine empirically documenting an effect or phenomenon whose explanation is not yet understood. While this might not count as a theoretical advancement under most uses of the term, it might nevertheless make a valuable contribution to knowledge. If nothing else, we typically need to know what needs explaining before we go about explaining it ( Rozin, 2001 ). Thus, disregarding the contribution of scholarship that is not “full-on” theory in some narrow sense is counterproductive to the advancement of knowledge.

Park et al. (2005) provide an instructive example. Their first study simply documents the existence of a strong finding. Unlike in the United States, Korean spam emails often contain an apology. What follows are five experiments testing various explanations before settling on a normative account. The work is not grounded in a specific theory, but it is clearly a systematic effort to document and explain a communication phenomenon. What if, however, they had packaged their studies as a series of articles rather than in one. Would this make the work any more or less theoretical?

One of the more controversial, meta-scientific questions in communication science is: Must we have theory? We answer “yes” in the broadest sense, as it helps to clarify our thinking about a topic. We also answer “no” in a narrower sense of theory. In explaining why not, we acknowledge that it would also always be better if we had at least one good theory than if we did not. Nevertheless, a well-articulated and relevant theory is not currently available for every conceivable topic or hypothesis worthy of investigation. It is not hard to imagine useful and enlightening scholarship that is neither formally engaged in theory building nor explicitly testing an existing theory. Simply put, if one is interested in a question or phenomenon where suitable theory is currently lacking, this ought not preclude research. Consequently, it follows that not all valuable scholarship requires theory in the narrow sense.

Which comes first, theory or data? The answer is it can be either, or the two can work together in an iterative, interactive, and abductive process ( Rozeboom, 2016 ). Different disciplines and specialties put a different emphasis on the primacy of theory in empirical research. Communication, on the one hand, sometimes views a strict hypothetico-deductive dogma as the ideal for formal theory testing, presupposing an existing formal theory from which to derive hypotheses. Computer science, on the other hand, is typically less strict in its placement or appreciation of theory in the research process. Quite often, computer scientists will obtain data, analyze them, and then identify the theory or theories that fit the findings as a final step. A communication scholar may scoff at this research process, though norms are powerful drivers of behavior ( Cialdini, 2006 ), and conventions related to theory are to be appreciated and scrutinized within the context of a discipline, specialty and even sub-specialty.

Building theory can be a purely logical process, but we are likely to develop more and better communication research if relevant data from exploratory research is available. Exploratory research, we contend, is not synonymous with being atheoretical. We tentatively define exploratory research as research guided by curiosity and seeking to document a finding or set of findings rather engaging in hypothetico-deductive hypothesis testing or focusing on explanation . We further note that not all hypothesis tests are theoretical. The logic behind hypotheses often takes the form of “others have found this, therefore we will too.” Such research falls in between more purely exploratory work and explicit theory testing where hypotheses follow from theory.

We contend that exploration is symbiotic with and often contributes to theory because it can highlight relationships that were unanticipated by theory, offering new hypotheses for future research. Even purely descriptive research can provide an understanding of the phenomena of interest, thereby providing a solid empirical foundation for conceptual construction. The placement of theory in the research process is not specifically a statement about the work’s value or rigor; it likely emphasizes the goals and norms of a particular research community. Consistent with our views on defining theory, we encourage our colleagues to be ecumenical in approaching theory-data time ordering.

An even more difficult question asks if all theories are equal. If some theories are indeed better than others, then what makes them so? Are there instances when no applicable theory is preferred to a misapplied or unreliable theory?

At the risk of diverting from our previous, more ecumenical perspective, we will tentatively take the position that some theories are indeed preferable to other theories—at least for certain applications—and along certain criteria of evaluation. For example, DeAndrea and Holbert (2017) expanded on Chaffee and Berger’s (1987) list of criteria for evaluating theory. Their refined list includes explanatory power, predictive power, parsimony, falsifiability, logical consistency, heuristic value, and organizing power. Building on this work, we further cautiously propose that theory can do more harm than good when it is misapplied, used haphazardly, or thrown at data to see if it sticks. If the goal of scholarship is the pursuit of knowledge and understanding, it seems possible that certain frames, stances, models, and understandings might be counterproductive or misguided.

From our perspective, a first consideration regarding the utility of theory is one of relevance. Does the sphere of application fall within the boundary conditions of the theory, or does the application involve interrogating the boundary conditions of the theory? If the answer to both questions is no, then the application is probably ill-advised on the grounds of relevance. Irrelevant theory distracts from empirical contributions. This is the theoretical equivalent of a red herring argument.

The second test is more difficult and involves a cost–benefit analysis of gains and losses in knowledge, insight, and understanding. Consistent with commentators such as Levine and McCornack (2014) , we envision evaluative dimensions, such as clarity, coherence, and verisimilitude, in assessing the scholarly value added by a theory. The more that a theory clarifies rather than clouds our understanding, the more valuable it is. Theory can bring order to otherwise unruly facts, findings, and ideas, or it can lead to logical inconsistencies, the latter obviously being less desirable. The insights offered by theories can align with known facts and findings or it can be contradicted by data and evidence ( Levine & McCornack, 2014 ).

In practice, assessing the alignment of theory with data is an especially thorny issue in quantitative, social scientific communication research. Not all scholarship strives to be empirical nor scientific, and theory-data alignment might not be the point in many scholarly endeavors. But when it is, theory-data alignment quickly becomes deeply problematic in the actual practice of communication scholarship, particularly when inferential statistics, and especially p -values, are involved ( Denworth, 2019 ).

One issue concerns “undead theories” ( Ferguson & Heene, 2012 ). It is not unusual in the social sciences for theoretical predictions to be soundly falsified, yet, nevertheless, applied despite their documented empirical deficiencies. Such theories are functionally sets of counterfactual conjectures that are passed off as good science. We anticipate that the reader will have their favorite undead theory, but we also anticipate that one scholar’s undead theory is another’s source of wisdom. Both can be true, which we appreciate, and will explain.

While the replication crisis in the social sciences has become an increasingly recognized issue ( Open Science Collaboration, 2015 ), it has also long been recognized that modern social science practices ensure that almost any hypothesis will receive mixed support regardless of its validity or verisimilitude ( Meehl, 1978 ). Essentially, the fact that the nil-null hypothesis is never literally true regardless of the soundness of the theory (Meehl’s crud factor), sub-optimal statistical power, questionable research practices such as p -hacking, and publication bias all combine to make the empirical merit of any claim murky at best ( Dienlin et al., 2021 ; Lewis, 2020 ; Markowitz et al., 2021 ). Accumulating more data over time often further muddies the water as mixed findings pile up and multiple citations can legitimately be provided in support of incompatible empirical claims. Not even meta-analysis is immune. As prior work shows ( Levine & Weber, 2020 ), regardless of the topic, findings in communication are heterogeneous, and the heterogeneity is seldom resolved by moderator analysis. In this way, meta-analytic results often document rather than resolve conclusions of mixed support for theoretical predictions. The net result is that a theory’s supporters and critics can both provide plenty of citations for why the theory is well supported and clearly falsified.

A common concern in academic research publishing is to articulate how one’s work makes a substantial theorical contribution ( DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ; Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Articles in flagship, high-impact communication journals are often rejected if theoretical contributions are not substantial and clearly expressed. For example, the Journal of Communication suggests “Submissions are expected to present arguments that are theoretically sophisticated, conceptually meaningful, and methodologically sound” ( Journal of Communication, 2022 ). The words sophisticated and meaningful in their instructions for authors are subjective and elusive. Considering the subjective aspect of such appraisal, what does it mean to make a theoretical contribution?

Given that we have argued so far that defining theory is misguided, that formal theory is not necessary for all research endeavors, and that unequivocally establishing the empirical merit of theory is nearly impossible, one might expect an argument dismissing the very idea of theoretical contribution. A close read of what preceded, however, conveys several ways to make a theoretical contribution (cf. Slater & Gleason, 2012 ). Clarifying a conceptualization, providing an explanation, making or testing a prediction, testing theoretical boundary conditions, articulating a unifying framework integrating two or more seemly unrelated facts, and identifying a moderator that resolves previously unexplained heterogeneity can all count as theoretical contributions if done in a way to be conceptually coherent. One can seek to create new theory, pit existing theories against each other, or reconcile apparently conflicting theories. In our view, all such outcomes can offer new knowledge that conceptually builds on an existing foundation of empirical findings.

Critically, a theoretical contribution is different from discovering a new, statistically significant finding. Moving from empirical findings to theoretical contribution involves answering questions related to the mechanism underlying the finding. How does the finding fit within the larger nomological network of findings in the domain ( Cronbach & Meehl, 1955 )? What are the limits of the finding? How robust is it? How far can it be generalized? What are its moderators and antecedents? These questions, among many others, may help to position a finding better as a theoretical contribution instead of an empirical one-off result.

The most basic types of theoretical contributions are conceptualizing or explicating a new construct, reconceptualizing an existing construct, or providing a new explanation for an empirically documented effect. These types of contributions might be considered theoretical building blocks for subsequent theoretical development. Although these types of contributions may also be seen as just minimally theoretical, they are nevertheless important because other types of theoretical contributions require well explicated components and explanations. Coherent conceptual structures can lead to testable and falsifiable hypotheses about human communication and logically coherent networks of hypotheses can lead to formal theory.

A second approach to theoretical contribution involves variations on theory creation. Arguments for the desirability of a new theory will often take one of three forms. The first notes the absence of a relevant theory for a given topic or purpose. If no relevant theory exists and if theory is desired, then it follows that theory creation is needed. The second type of argument rests on making the case that existing, relevant theory is deficient, and the deficiencies are both sufficiently severe and intractable to justify a new theory as a rival. Third, prior theory can be accepted, but arguments are made that the new perspective offers additional insights that would not otherwise be gained.

Once a theory exists in the literature, it is often the goal of communication research to test, extend, modify, or apply a theory to improve our understanding of human communication. Each of these (testing, extending, modifying, or applying) moves communication theory forward. We note, however, that at least for scientific research, testing should typically precede the other forms of contribution to ensure theoretical adequacy prior to extension or application.

Many discussions of theoretical contributions will involve value judgments regarding theoretical bandwidth. Discussions of theoretical bandwidth, in turn, may deal with two qualitatively different issues. The first relates to how theory is defined. One might think of explicating a construct as a narrower contribution than explaining the relationship between two explicated constructs. Explaining how a well-understood effect fits with a network of documented effects is broader still.

Second, communication theories vary widely in their topical scope and boundary conditions. Communication theories might focus on a particular topic or phenomenon, others on a broader domain or function, and others still might be general theories of communication. Further, regardless of topical breadth, boundary conditions can vary. Communication theories, for example, might be limited to a particular age group, point in time, media, or culture.

It is likely tempting to equate theoretical bandwidth and theoretical contribution under the likely tacit presumption that more is better. While surely there are knowledge-gain advantages to breadth, any firm link between breadth and contribution is qualified by all other things being equal. Surely contribution is more closely tied to how well a theoretical goal is accomplished than to how ambitious the goal is (cf., DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ).

Rather than reviewing the extensive literature on the value of theory, we focus here on two benefits of theory that we believe are highlighted less frequently but are no less important.

Generality and external validity

Perhaps the most underappreciated benefit of theory is that it can provide satisfying answers to questions of generality in ways that data simply cannot. Theory is a better approach to achieving external validity than research design.

We have all seen data collected on college students and wondered if the findings might apply to working adults. We all likely agree that for most topics, a nationally representative sample is preferable to a sample of college students (though, see Coppock et al., 2018 ). Nevertheless, we might still wonder that if the data were collected at a different point in time, or if the questions were worded a bit differently, or perhaps presented in a different order, would the findings be the same? These sorts of questions cannot be answered with data because we can never sample everyone everywhere over all times in all possible ways. No matter how much data we have, data are finite, and representative sampling and inferential statistics do not change this uncomfortable truth.

Fortunately, theory provides an elegant solution. Theoretical claims specify what is expected under what conditions. Theory, and more precisely its boundary conditions, provide us with statements of the extent of generality. As described by Mook (1983) , we specify generality theoretically, then we test and validate claims of generality with data. Rather than fretting over the sampling of participants, multiple message instantiations, multiple situations, and a host of other study-specific idiosyncrasies, we use theory to make generalizations and data to test those generalizations ( Ewoldsen, 2022 ). We could ask if a theory applies to non-WEIRD cultures, and then test core claims with a non-WEIRD culture ( Henrich et al., 2010 ; Many Labs 2, 2018 ).

Theory as agenda setting

A second underappreciated function of theory is research agenda setting. Just as the media might tell us which news topics and frames are important, so too does theory tell us what we need to study, how to study it, and what to expect. It is not unusual for new researchers to struggle with topic selection. Theory provides a straight-forward way to come up with a hypothesis and an approach to testing it. This topic selection approach can also be flipped. We can ask, what if a theory was wrong? How might we show that? A research design should flow from these questions.

Theory offers an even more important agenda setting function. As Berlo (1960) famously identified when defining communication as process, a wide variety of forces can affect how communication unfolds. Regardless of the specific topic or focus, the potentially important considerations are numerous. Theory tells us what is most important and what is less important. In other words, theory tells us what to prioritize.

We are more pleased than not with the current state of communication theory as its progress is undeniable. There was a time when the lack of communication theory was bemoaned and when most theories were taken from other disciplines (see Berger, 1991 ). Our perception of the current literature, formed by our lived experience across decades of publishing and reading communication scholarship, is that the number of communication theories and theoretical ideas have grown, and the communication trade deposit with related fields has diminished. The latter point, of course, deserves a strict empirical evaluation to test how communication and other social sciences share ideas and theories.

As the reader has surely noticed, we have approached this article from a particular perspective. The present authors have a quantitative and social scientific approach to communication scholarship. A consequence of originating from this scholarly tradition is that our commentary is better targeted for research publishing in outlets such as Human Communication Research than outlets like Communication, Culture, & Critique . Both are worthy outlets, but they have different orientations and conventions.

Like most communication scholars, we are theory advocates. We use, have written our own, and made contributions to theory on a range of topics relevant to human communication. While we ascribe to the idea that “there is nothing so practical as a good theory” ( Lewin, 1951 , p. 169), blind allegiance to theory is ill-advised. Theories, we believe, must have testable and falsifiable components to them. We encourage our fellow communication scholars to “follow the data.” Moving science forward requires theoretical predictions that hold up to data over time.

Replications play an increasingly important role in theory testing, but also add a final set of complications to address. Theory and evidence can misalign for several reasons, and it is usually unclear why a test failed. Perhaps some critical aspect of the research setting was different, producing an unexpected result. A moderating variable may have impacted the results, such that the findings do not invalidate the theory, but instead provides a nuanced understanding of the conditions that led to a particular effect and those that did not (or led to the opposite effect). Theory should be a guidepost for empirical research, not gospel, upon considering the results. Of course, theory and data can also misalign because the theory is mis-specified. In practice, it can be difficult to discern valid support from false positives and mis-specified predictions from a methodological artifact or undetected moderators. Nevertheless, we envision a future where replication is both more prevalent and more valued.

Communication is an eclectic discipline, and science is not the only method for understanding communication. Further, we as a field draw on and adopt ideas from different fields, authors publish in journals outside of communication research, and there is no singular approach to the same research question. We encourage authors to continue this tolerance and flexibility with exploratory and “pre-theory” work as well. As mentioned, there are times when a good theory simply does not fit one’s phenomenon of interest. Communication scholars should not be faced with a “square peg, round hole” problem just to satisfy reviewers who demand more theory. One can try to fit a square peg into a round hole with enough force, but it will not fit well and there may be important consequences because of this exercise (e.g., theory–data misalignment). Exploratory work should be considered and applauded when we simply do not know how concepts will relate to each other. Proposing a research question instead of hypotheses derived from theory is not an admission of a research study being atheoretical, but instead, an admission of one’s curiosity and uncertainty. Thus, we envision a future where exploratory and descriptive work is more prevalent and more appreciated.

It is also important for authors to think about and explicitly communicate the role of theory in their research. This article has noted the many functions that theory can serve; yet, these functions are often assumed or implied in a manuscript when they could be made explicit. Being forthcoming about the role of theory in one’s research will lead to conceptual and contribution-related clarity. This will lead to less superficial applications of theory (e.g., theoretical name dropping ) and toward more conceptual richness. If communication research is to value theory—and we undoubtedly think it should—then theory should be used appropriately. Theories are built on a foundation of empirical evidence, collected over time allowing researchers to draw nuanced conclusions and make subsequent predictions about human communication. Using the term theory to sound more scientific, rigorous, or grounded is gratuitous and should be avoided. Consequently, we envision a future where communication theory, in form and function, is used more thoughtfully and transparently.

Finally, we are encouraged that all major communication research journals have a large focus on theory in their articles (e.g., at least 50% of articles in each journal mention theory in some manner; Figure 1 ). However, the degree to which the published communication literature is advancing theory in consequential ways or settings is unclear ( DeAndrea & Holbert, 2017 ). We encourage scholars to be flexible with their assumptions about a theory, testing it in ways that might be unconventional and creative in the pursuit of new knowledge. To this end, null effects are still informative ( Francis, 2012 ; Levine, 2013 ), especially if a study is adequately powered. For example, understanding what leads to null effects might be helpful for the development of boundary conditions of theory. Null effects are difficult to publish, but communication research can lead in their normalization in the pursuit of greater theoretical precision and explication. Thus, we envision a future where researchers are more frank about empirical support, and more precise with predictions.

Data related to Figure 1 can be retrieved from Markowitz et al. (2021) or by contacting David M. Markowitz.

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

The authors also report no conflicts of interest with the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

A systematic, qualitative review of how theory terms were used across the entire sample is beyond the scope of this commentary. We used these data to descriptively demonstrate how theory is prevalent in communication research, and used as a means to achieve different ends.

Bem D. ( 2003 ). Writing the empirical journal article. In Darley J. M. , Zanna M. P. (Eds.), The complete academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). (pp. 185–219). American Psychological Association .

Google Scholar

Google Preview

Berger C. R. ( 1991 ). Communication theories and other curios . Communication Monographs , 58 ( 1 ), 101 – 113 . https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759109376216

Berlo D. K. ( 1960 ). The process of communication: An introduction to theory and practice . Holt, Rinehart and Winston .

Chaffee S. H. , Berger C. R. ( 1987 ). What communication scientists do. In Berger C. R. , Chaffee S. H. (Eds.), Handbook of Communication Science (pp. 99 – 122 ). Sage .

Cialdini R. B. ( 2006 ). Influence: The psychology of persuasion . Harper Business .

Coppock A. , Leeper T. J. , Mullinix K. J. ( 2018 ). Generalizability of heterogeneous treatment effect estimates across samples . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences , 115 ( 49 ), 12441 – 12446 . https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1808083115

Cronbach L. J. , Meehl P. E. ( 1955 ). Construct validity in psychological tests . Psychological Bulletin , 52 ( 4 ), 281 – 302 . https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

Denworth L. ( 2019 ). The significant problem of p-values . Scientific American . https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1019-62

DeAndrea D. C. , Holbert L. R. ( 2017 ) Increasing clarity where it is needed most: Articulating and evaluating theoretical contributions . Annals of the International Communication Association , 41 ( 2 ), 168 – 180 . https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2017.1304163

Dienlin T. , Johannes N. , Bowman N. D. , Masur P. K. , Engesser S. , Kümpel A. S. , Lukito J. , Bier L. M. , Zhang R. , Johnson B. K. , Huskey R. , Schneider F. M. , Breuer J. , Parry D. A. , Vermeulen I. , Fisher J. T. , Banks J. , Weber R. , Ellis D. A. , de Vreese C. ( 2021 ). An agenda for open science in communication . Journal of Communication , 71 ( 1 ), 1 – 26 . https://doi.org/10.1093/JOC/JQZ052

Ewoldsen D. R. ( 2022 ). A discussion of falsifiability and evaluating research: Issues of variance accounted for and external validity . Asian Communication Research , 19 ( 2 ), 5 – 14 . https://doi.org/10.20879/acr.2022.19.2.5

Ferguson C. J. , Heene M. ( 2012 ). A vast graveyard of undead theories: Publication bias and psychological science’s aversion to the null . Perspectives on Psychological Science , 7 ( 6 ), 555 – 561 . https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691612459059

Francis G. ( 2012 ). Publication bias and the failure of replication in experimental psychology . Psychonomic Bulletin & Review , 19 ( 6 ), 975 – 991 . https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-012-0322-y

Henrich J. , Heine S. J. , Norenzayan A. ( 2010 ). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences , 33 ( 2–3 ), 61 – 83 . https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X

Journal of Communication . ( 2022 ). Author instructions . Oxford Academic . https://academic.oup.com/joc/pages/General_Instructions

Levine T. R. ( 2013 ). A defense of publishing nonsignificant (ns) results . Communication Research Reports , 30 ( 3 ), 270 – 274 . https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2013.806261

Levine T. R. , McCornack S. A. ( 2014 ). Theorizing about deception . Journal of Language and Social Psychology , 33 ( 4 ), 431 – 440 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927x14536397

Levine T. R. , Weber R. ( 2020 ). Unresolved heterogeneity in meta-analysis: Combined construct invalidity, confounding, and other challenges to understanding mean effect sizes . Human Communication Research , 46 ( 2–3 ), 343 – 354 . https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqz019

Lewin K. ( 1951 ). Field theory in social science: Selected theoretical papers . Harper & Brothers . https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1951-06769-000

Lewis N. A. ( 2020 ). Open communication science: A primer on why and some recommendations for how . Communication Methods and Measures , 14 ( 2 ), 71 – 82 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2019.1685660

Many Labs 2 . ( 2018 ). Many Labs 2: Investigating variation in replicability across samples and settings . Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science , 1 ( 4 ), 443 – 490 . https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245918810

Markowitz D. M. , Song H. , Taylor S. H. ( 2021 ). Tracing the adoption and effects of open science in communication research . Journal of Communication , 71 ( 5 ), 739 – 763 . https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqab030

Meehl P. E. ( 1978 ). Theoretical risks and tabular asterisks: Sir Karl, Sir Ronald, and the slow progress of soft psychology . Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology , 46 ( 4 ), 806 – 834 . https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.46.4.806

Miller G. R. , Nicholson H. E. ( 1976 ). Communication inquiry: A perspective on a process . Addison-Wesley Pub. Co .

Mook D. G. ( 1983 ). In defense of external invalidity . American Psychologist , 38 ( 4 ), 379 – 387 . https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.38.4.379

Park H. S. , Lee H. E. , Song J. A. ( 2005 ). “ I am sorry to send you spam” Cross-cultural difference in email advertising in Korea and the US . Human Communication Research , 31 ( 3 ), 365 – 398 , https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2005.tb00876.x

Open Science Collaboration . ( 2015 ). Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science . Science , 349 ( 6251 ), aac4716. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aac4716

Rozeboom W. W. ( 2016 ). Good science is abductive, not hypothetico-deductive. In Harlow L. L. , Mulaik S. A. , Steiger J. H. (Eds.), What if there were no significance tests? (pp. 335–391). Routledge .

Rozin P. ( 2001 ). Social psychology and science: Some lessons from Solomon Asch . Personality and Social Psychology Review , 5 ( 1 ), 2 – 14 . https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327957PSPR0501_1

Slater M. D. , Gleason L. S. ( 2012 ). Contributing to theory and knowledge in quantitative communication science . Communication Methods and Measures , 6 ( 4 ), 215 – 236 . https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.732626

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Advertising and Corporate Services

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1468-2958

- Copyright © 2024 International Communication Association

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Guide to Communication Research Methodologies: Quantitative, Qualitative and Rhetorical Research

Overview of Communication

Communication research methods, quantitative research, qualitative research, rhetorical research, mixed methodology.

Students interested in earning a graduate degree in communication should have at least some interest in understanding communication theories and/or conducting communication research. As students advance from undergraduate to graduate programs, an interesting change takes place — the student is no longer just a repository for knowledge. Rather, the student is expected to learn while also creating knowledge. This new knowledge is largely generated through the development and completion of research in communication studies. Before exploring the different methodologies used to conduct communication research, it is important to have a foundational understanding of the field of communication.

Defining communication is much harder than it sounds. Indeed, scholars have argued about the topic for years, typically differing on the following topics:

- Breadth : How many behaviors and actions should or should not be considered communication.

- Intentionality : Whether the definition includes an intention to communicate.

- Success : Whether someone was able to effectively communicate a message, or merely attempted to without it being received or understood.

However, most definitions discuss five main components, which include: sender, receiver, context/environment, medium, and message. Broadly speaking, communication research examines these components, asking questions about each of them and seeking to answer those questions.

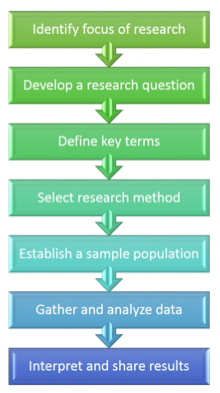

As students seek to answer their own questions, they follow an approach similar to most other researchers. This approach proceeds in five steps: conceptualize, plan and design, implement a methodology, analyze and interpret, reconceptualize.

- Conceptualize : In the conceptualization process, students develop their area of interest and determine if their specific questions and hypotheses are worth investigating. If the research has already been completed, or there is no practical reason to research the topic, students may need to find a different research topic.

- Plan and Design : During planning and design students will select their methods of evaluation and decide how they plan to define their variables in a measurable way.

- Implement a Methodology : When implementing a methodology, students collect the data and information they require. They may, for example, have decided to conduct a survey study. This is the step when they would use their survey to collect data. If students chose to conduct a rhetorical criticism, this is when they would analyze their text.

- Analyze and Interpret : As students analyze and interpret their data or evidence, they transform the raw findings into meaningful insights. If they chose to conduct interviews, this would be the point in the process where they would evaluate the results of the interviews to find meaning as it relates to the communication phenomena of interest.

- Reconceptualize : During reconceptualization, students ask how their findings speak to a larger body of research — studies related to theirs that have already been completed and research they should execute in the future to continue answering new questions.

This final step is crucial, and speaks to an important tenet of communication research: All research contributes to a better overall understanding of communication and moves the field forward by enabling the development of new theories.

In the field of communication, there are three main research methodologies: quantitative, qualitative, and rhetorical. As communication students progress in their careers, they will likely find themselves using one of these far more often than the others.

Quantitative research seeks to establish knowledge through the use of numbers and measurement. Within the overarching area of quantitative research, there are a variety of different methodologies. The most commonly used methodologies are experiments, surveys, content analysis, and meta-analysis. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Experiments : Experiments are an empirical form of research that enable the researcher to study communication in a controlled environment. For example, a researcher might know that there are typical responses people use when they are interrupted during a conversation. However, it might be unknown as to how frequency of interruption provokes those different responses (e.g., do communicators use different responses when interrupted once every 10 minutes versus once per minute?). An experiment would allow a researcher to create these two environments to test a hypothesis or answer a specific research question. As you can imagine, it would be very time consuming — and probably impossible — to view this and measure it in the real world. For that reason, an experiment would be perfect for this research inquiry.

Surveys : Surveys are often used to collect information from large groups of people using scales that have been tested for validity and reliability. A researcher might be curious about how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. The researcher could create a survey where respondents answer questions about a) the information their supervisors self-disclose and b) their perceptions of their supervisors. The data collected about these two variables could offer interesting insights about this communication. As you would guess, an experiment would not work in this case because the researcher needs to assess a real relationship and they need insight into the mind of the respondent.

Content Analysis : Content analysis is used to count the number of occurrences of a phenomenon within a source of media (e.g., books, magazines, commercials, movies, etc.). For example, a researcher might be interested in finding out if people of certain races are underrepresented on television. They might explore this area of research by counting the number of times people of different races appear in prime time television and comparing that to the actual proportions in society.

Meta-Analysis : In this technique, a researcher takes a collection of quantitative studies and analyzes the data as a whole to get a better understanding of a communication phenomenon. For example, a researcher might be curious about how video games affect aggression. This researcher might find that many studies have been done on the topic, sometimes with conflicting results. In their meta-analysis, they could analyze the existing statistics as a whole to get a better understanding of the relationship between the two variables.

Qualitative research is interested in exploring subjects’ perceptions and understandings as they relate to communication. Imagine two researchers who want to understand student perceptions of the basic communication course at a university. The first researcher, a quantitative researcher, might measure absences to understand student perception. The second researcher, a qualitative researcher, might interview students to find out what they like and dislike about a course. The former is based on hard numbers, while the latter is based on human experience and perception.

Qualitative researchers employ a variety of different methodologies. Some of the most popular are interviews, focus groups, and participant observation. To better understand these research methods, you can explore the following examples:

Interviews : This typically consists of a researcher having a discussion with a participant based on questions developed by the researcher. For example, a researcher might be interested in how parents exert power over the lives of their children while the children are away at college. The researcher could spend time having conversations with college students about this topic, transcribe the conversations and then seek to find themes across the different discussions.

Focus Groups : A researcher using this method gathers a group of people with intimate knowledge of a communication phenomenon. For example, if a researcher wanted to understand the experience of couples who are childless by choice, he or she might choose to run a series of focus groups. This format is helpful because it allows participants to build on one another’s experiences, remembering information they may otherwise have forgotten. Focus groups also tend to produce useful information at a higher rate than interviews. That said, some issues are too sensitive for focus groups and lend themselves better to interviews.

Participant Observation : As the name indicates, this method involves the researcher watching participants in their natural environment. In some cases, the participants may not know they are being studied, as the researcher fully immerses his or herself as a member of the environment. To illustrate participant observation, imagine a researcher curious about how humor is used in healthcare. This researcher might immerse his or herself in a long-term care facility to observe how humor is used by healthcare workers interacting with patients.

Rhetorical research (or rhetorical criticism) is a form of textual analysis wherein the researcher systematically analyzes, interprets, and critiques the persuasive power of messages within a text. This takes on many forms, but all of them involve similar steps: selecting a text, choosing a rhetorical method, analyzing the text, and writing the criticism.

To illustrate, a researcher could be interested in how mass media portrays “good degrees” to prospective college students. To understand this communication, a rhetorical researcher could take 30 articles on the topic from the last year and write a rhetorical essay about the criteria used and the core message argued by the media.

Likewise, a researcher could be interested in how women in management roles are portrayed in television. They could select a group of popular shows and analyze that as the text. This might result in a rhetorical essay about the behaviors displayed by these women and what the text says about women in management roles.

As a final example, one might be interested in how persuasion is used by the president during the White House Correspondent’s Dinner. A researcher could select several recent presidents and write a rhetorical essay about their speeches and how they employed persuasion during their delivery.

Taking a mixed methods approach results in a research study that uses two or more techniques discussed above. Often, researchers will pair two methods together in the same study examining the same phenomenon. Other times, researchers will use qualitative methods to develop quantitative research, such as a researcher who uses a focus group to discuss the validity of a survey before it is finalized.

The benefit of mixed methods is that it offers a richer picture of a communication phenomenon by gathering data and information in multiple ways. If we explore some of the earlier examples, we can see how mixed methods might result in a better understanding of the communication being studied.

Example 1 : In surveys, we discussed a researcher interested in understanding how a supervisor sharing personal information with his or her subordinate affects the way the subordinate perceives his or her supervisor. While a survey could give us some insight into this communication, we could also add interviews with subordinates. Exploring their experiences intimately could give us a better understanding of how they navigate self-disclosure in a relationship based on power differences.

Example 2 : In content analysis, we discussed measuring representation of different races during prime time television. While we can count the appearances of members of different races and compare that to the composition of the general population, that doesn’t tell us anything about their portrayal. Adding rhetorical criticism, we could talk about how underrepresented groups are portrayed in either a positive or negative light, supporting or defying commonly held stereotypes.

Example 3 : In interviews, we saw a researcher who explored how power could be exerted by parents over their college-age children who are away at school. After determining the tactics used by parents, this interview study could have a phase two. In this phase, the researcher could develop scales to measure each tactic and then use those scales to understand how the tactics affect other communication constructs. One could argue, for example, that student anxiety would increase as a parent exerts greater power over that student. A researcher could conduct a hierarchical regression to see how each power tactic effects the levels of stress experienced by a student.

As you can see, each methodology has its own merits, and they often work well together. As students advance in their study of communication, it is worthwhile to learn various research methods. This allows them to study their interests in greater depth and breadth. Ultimately, they will be able to assemble stronger research studies and answer their questions about communication more effectively.

Note : For more information about research in the field of communication, check out our Guide to Communication Research and Scholarship .

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

The Craft of Writing a Strong Hypothesis

Table of Contents

Writing a hypothesis is one of the essential elements of a scientific research paper. It needs to be to the point, clearly communicating what your research is trying to accomplish. A blurry, drawn-out, or complexly-structured hypothesis can confuse your readers. Or worse, the editor and peer reviewers.

A captivating hypothesis is not too intricate. This blog will take you through the process so that, by the end of it, you have a better idea of how to convey your research paper's intent in just one sentence.

What is a Hypothesis?

The first step in your scientific endeavor, a hypothesis, is a strong, concise statement that forms the basis of your research. It is not the same as a thesis statement , which is a brief summary of your research paper .

The sole purpose of a hypothesis is to predict your paper's findings, data, and conclusion. It comes from a place of curiosity and intuition . When you write a hypothesis, you're essentially making an educated guess based on scientific prejudices and evidence, which is further proven or disproven through the scientific method.

The reason for undertaking research is to observe a specific phenomenon. A hypothesis, therefore, lays out what the said phenomenon is. And it does so through two variables, an independent and dependent variable.

The independent variable is the cause behind the observation, while the dependent variable is the effect of the cause. A good example of this is “mixing red and blue forms purple.” In this hypothesis, mixing red and blue is the independent variable as you're combining the two colors at your own will. The formation of purple is the dependent variable as, in this case, it is conditional to the independent variable.

Different Types of Hypotheses

Types of hypotheses

Some would stand by the notion that there are only two types of hypotheses: a Null hypothesis and an Alternative hypothesis. While that may have some truth to it, it would be better to fully distinguish the most common forms as these terms come up so often, which might leave you out of context.

Apart from Null and Alternative, there are Complex, Simple, Directional, Non-Directional, Statistical, and Associative and casual hypotheses. They don't necessarily have to be exclusive, as one hypothesis can tick many boxes, but knowing the distinctions between them will make it easier for you to construct your own.

1. Null hypothesis

A null hypothesis proposes no relationship between two variables. Denoted by H 0 , it is a negative statement like “Attending physiotherapy sessions does not affect athletes' on-field performance.” Here, the author claims physiotherapy sessions have no effect on on-field performances. Even if there is, it's only a coincidence.

2. Alternative hypothesis

Considered to be the opposite of a null hypothesis, an alternative hypothesis is donated as H1 or Ha. It explicitly states that the dependent variable affects the independent variable. A good alternative hypothesis example is “Attending physiotherapy sessions improves athletes' on-field performance.” or “Water evaporates at 100 °C. ” The alternative hypothesis further branches into directional and non-directional.

- Directional hypothesis: A hypothesis that states the result would be either positive or negative is called directional hypothesis. It accompanies H1 with either the ‘<' or ‘>' sign.

- Non-directional hypothesis: A non-directional hypothesis only claims an effect on the dependent variable. It does not clarify whether the result would be positive or negative. The sign for a non-directional hypothesis is ‘≠.'

3. Simple hypothesis

A simple hypothesis is a statement made to reflect the relation between exactly two variables. One independent and one dependent. Consider the example, “Smoking is a prominent cause of lung cancer." The dependent variable, lung cancer, is dependent on the independent variable, smoking.

4. Complex hypothesis

In contrast to a simple hypothesis, a complex hypothesis implies the relationship between multiple independent and dependent variables. For instance, “Individuals who eat more fruits tend to have higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.” The independent variable is eating more fruits, while the dependent variables are higher immunity, lesser cholesterol, and high metabolism.

5. Associative and casual hypothesis

Associative and casual hypotheses don't exhibit how many variables there will be. They define the relationship between the variables. In an associative hypothesis, changing any one variable, dependent or independent, affects others. In a casual hypothesis, the independent variable directly affects the dependent.

6. Empirical hypothesis

Also referred to as the working hypothesis, an empirical hypothesis claims a theory's validation via experiments and observation. This way, the statement appears justifiable and different from a wild guess.

Say, the hypothesis is “Women who take iron tablets face a lesser risk of anemia than those who take vitamin B12.” This is an example of an empirical hypothesis where the researcher the statement after assessing a group of women who take iron tablets and charting the findings.

7. Statistical hypothesis

The point of a statistical hypothesis is to test an already existing hypothesis by studying a population sample. Hypothesis like “44% of the Indian population belong in the age group of 22-27.” leverage evidence to prove or disprove a particular statement.

Characteristics of a Good Hypothesis

Writing a hypothesis is essential as it can make or break your research for you. That includes your chances of getting published in a journal. So when you're designing one, keep an eye out for these pointers:

- A research hypothesis has to be simple yet clear to look justifiable enough.

- It has to be testable — your research would be rendered pointless if too far-fetched into reality or limited by technology.

- It has to be precise about the results —what you are trying to do and achieve through it should come out in your hypothesis.

- A research hypothesis should be self-explanatory, leaving no doubt in the reader's mind.

- If you are developing a relational hypothesis, you need to include the variables and establish an appropriate relationship among them.

- A hypothesis must keep and reflect the scope for further investigations and experiments.

Separating a Hypothesis from a Prediction

Outside of academia, hypothesis and prediction are often used interchangeably. In research writing, this is not only confusing but also incorrect. And although a hypothesis and prediction are guesses at their core, there are many differences between them.

A hypothesis is an educated guess or even a testable prediction validated through research. It aims to analyze the gathered evidence and facts to define a relationship between variables and put forth a logical explanation behind the nature of events.

Predictions are assumptions or expected outcomes made without any backing evidence. They are more fictionally inclined regardless of where they originate from.

For this reason, a hypothesis holds much more weight than a prediction. It sticks to the scientific method rather than pure guesswork. "Planets revolve around the Sun." is an example of a hypothesis as it is previous knowledge and observed trends. Additionally, we can test it through the scientific method.

Whereas "COVID-19 will be eradicated by 2030." is a prediction. Even though it results from past trends, we can't prove or disprove it. So, the only way this gets validated is to wait and watch if COVID-19 cases end by 2030.

Finally, How to Write a Hypothesis

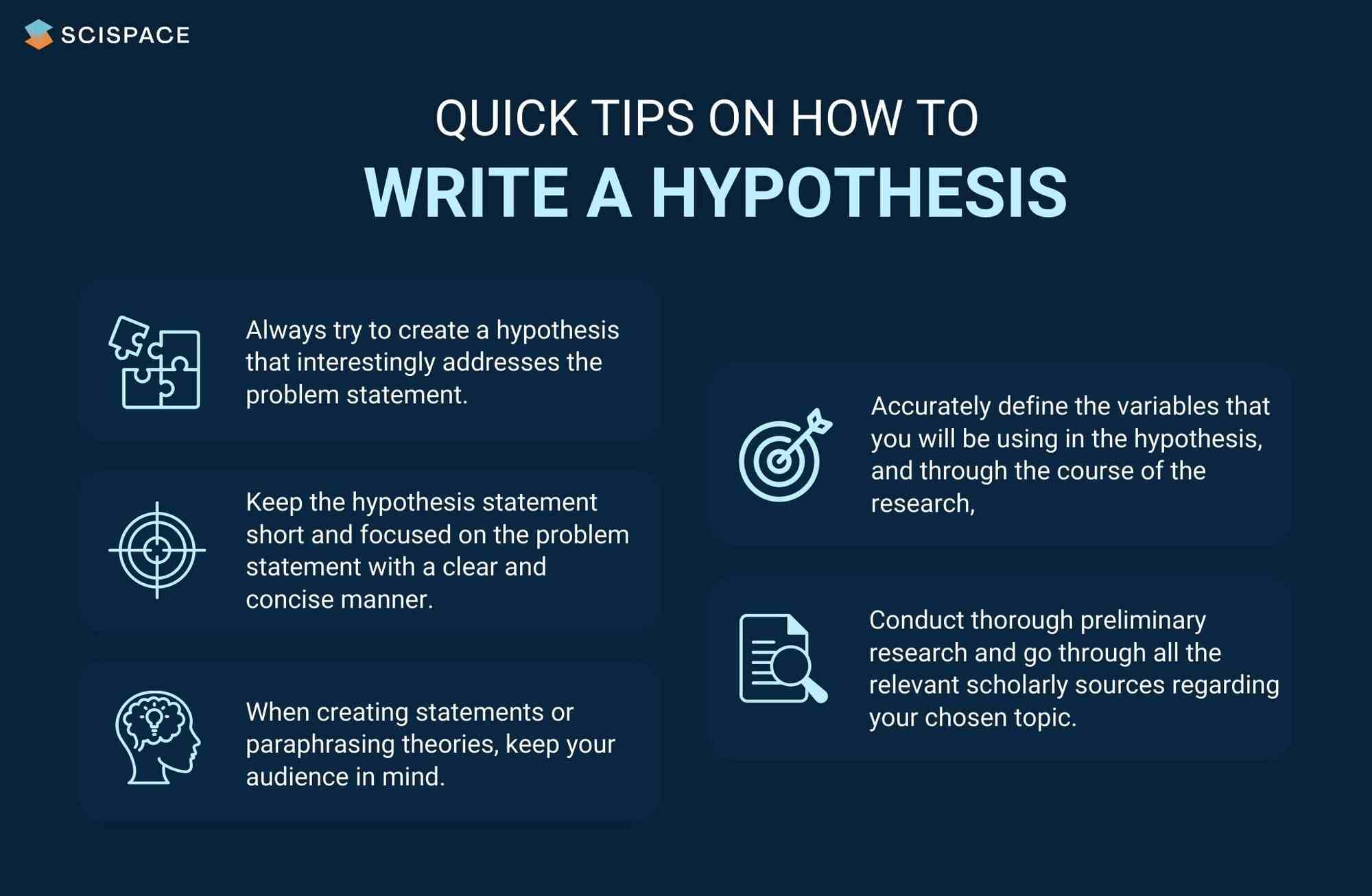

Quick tips on writing a hypothesis

1. Be clear about your research question

A hypothesis should instantly address the research question or the problem statement. To do so, you need to ask a question. Understand the constraints of your undertaken research topic and then formulate a simple and topic-centric problem. Only after that can you develop a hypothesis and further test for evidence.

2. Carry out a recce

Once you have your research's foundation laid out, it would be best to conduct preliminary research. Go through previous theories, academic papers, data, and experiments before you start curating your research hypothesis. It will give you an idea of your hypothesis's viability or originality.

Making use of references from relevant research papers helps draft a good research hypothesis. SciSpace Discover offers a repository of over 270 million research papers to browse through and gain a deeper understanding of related studies on a particular topic. Additionally, you can use SciSpace Copilot , your AI research assistant, for reading any lengthy research paper and getting a more summarized context of it. A hypothesis can be formed after evaluating many such summarized research papers. Copilot also offers explanations for theories and equations, explains paper in simplified version, allows you to highlight any text in the paper or clip math equations and tables and provides a deeper, clear understanding of what is being said. This can improve the hypothesis by helping you identify potential research gaps.

3. Create a 3-dimensional hypothesis

Variables are an essential part of any reasonable hypothesis. So, identify your independent and dependent variable(s) and form a correlation between them. The ideal way to do this is to write the hypothetical assumption in the ‘if-then' form. If you use this form, make sure that you state the predefined relationship between the variables.

In another way, you can choose to present your hypothesis as a comparison between two variables. Here, you must specify the difference you expect to observe in the results.

4. Write the first draft

Now that everything is in place, it's time to write your hypothesis. For starters, create the first draft. In this version, write what you expect to find from your research.

Clearly separate your independent and dependent variables and the link between them. Don't fixate on syntax at this stage. The goal is to ensure your hypothesis addresses the issue.

5. Proof your hypothesis

After preparing the first draft of your hypothesis, you need to inspect it thoroughly. It should tick all the boxes, like being concise, straightforward, relevant, and accurate. Your final hypothesis has to be well-structured as well.

Research projects are an exciting and crucial part of being a scholar. And once you have your research question, you need a great hypothesis to begin conducting research. Thus, knowing how to write a hypothesis is very important.

Now that you have a firmer grasp on what a good hypothesis constitutes, the different kinds there are, and what process to follow, you will find it much easier to write your hypothesis, which ultimately helps your research.

Now it's easier than ever to streamline your research workflow with SciSpace Discover . Its integrated, comprehensive end-to-end platform for research allows scholars to easily discover, write and publish their research and fosters collaboration.

It includes everything you need, including a repository of over 270 million research papers across disciplines, SEO-optimized summaries and public profiles to show your expertise and experience.

If you found these tips on writing a research hypothesis useful, head over to our blog on Statistical Hypothesis Testing to learn about the top researchers, papers, and institutions in this domain.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. what is the definition of hypothesis.

According to the Oxford dictionary, a hypothesis is defined as “An idea or explanation of something that is based on a few known facts, but that has not yet been proved to be true or correct”.

2. What is an example of hypothesis?

The hypothesis is a statement that proposes a relationship between two or more variables. An example: "If we increase the number of new users who join our platform by 25%, then we will see an increase in revenue."

3. What is an example of null hypothesis?

A null hypothesis is a statement that there is no relationship between two variables. The null hypothesis is written as H0. The null hypothesis states that there is no effect. For example, if you're studying whether or not a particular type of exercise increases strength, your null hypothesis will be "there is no difference in strength between people who exercise and people who don't."

4. What are the types of research?

• Fundamental research

• Applied research

• Qualitative research

• Quantitative research

• Mixed research

• Exploratory research

• Longitudinal research

• Cross-sectional research

• Field research

• Laboratory research

• Fixed research

• Flexible research

• Action research

• Policy research

• Classification research

• Comparative research

• Causal research

• Inductive research

• Deductive research

5. How to write a hypothesis?

• Your hypothesis should be able to predict the relationship and outcome.

• Avoid wordiness by keeping it simple and brief.

• Your hypothesis should contain observable and testable outcomes.

• Your hypothesis should be relevant to the research question.

6. What are the 2 types of hypothesis?

• Null hypotheses are used to test the claim that "there is no difference between two groups of data".

• Alternative hypotheses test the claim that "there is a difference between two data groups".

7. Difference between research question and research hypothesis?

A research question is a broad, open-ended question you will try to answer through your research. A hypothesis is a statement based on prior research or theory that you expect to be true due to your study. Example - Research question: What are the factors that influence the adoption of the new technology? Research hypothesis: There is a positive relationship between age, education and income level with the adoption of the new technology.

8. What is plural for hypothesis?

The plural of hypothesis is hypotheses. Here's an example of how it would be used in a statement, "Numerous well-considered hypotheses are presented in this part, and they are supported by tables and figures that are well-illustrated."

9. What is the red queen hypothesis?

The red queen hypothesis in evolutionary biology states that species must constantly evolve to avoid extinction because if they don't, they will be outcompeted by other species that are evolving. Leigh Van Valen first proposed it in 1973; since then, it has been tested and substantiated many times.

10. Who is known as the father of null hypothesis?

The father of the null hypothesis is Sir Ronald Fisher. He published a paper in 1925 that introduced the concept of null hypothesis testing, and he was also the first to use the term itself.

11. When to reject null hypothesis?

You need to find a significant difference between your two populations to reject the null hypothesis. You can determine that by running statistical tests such as an independent sample t-test or a dependent sample t-test. You should reject the null hypothesis if the p-value is less than 0.05.

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

The Research Hypothesis: Role and Construction

- First Online: 01 January 2012

Cite this chapter

- Phyllis G. Supino EdD 3

5994 Accesses

A hypothesis is a logical construct, interposed between a problem and its solution, which represents a proposed answer to a research question. It gives direction to the investigator’s thinking about the problem and, therefore, facilitates a solution. There are three primary modes of inference by which hypotheses are developed: deduction (reasoning from a general propositions to specific instances), induction (reasoning from specific instances to a general proposition), and abduction (formulation/acceptance on probation of a hypothesis to explain a surprising observation).

A research hypothesis should reflect an inference about variables; be stated as a grammatically complete, declarative sentence; be expressed simply and unambiguously; provide an adequate answer to the research problem; and be testable. Hypotheses can be classified as conceptual versus operational, single versus bi- or multivariable, causal or not causal, mechanistic versus nonmechanistic, and null or alternative. Hypotheses most commonly entail statements about “variables” which, in turn, can be classified according to their level of measurement (scaling characteristics) or according to their role in the hypothesis (independent, dependent, moderator, control, or intervening).