A Step-by-Step Guide to Doing Historical Research [without getting hysterical!] In addition to being a scholarly investigation, research is a social activity intended to create new knowledge. Historical research is your informed response to the questions that you ask while examining the record of human experience. These questions may concern such elements as looking at an event or topic, examining events that lead to the event in question, social influences, key players, and other contextual information. This step-by-step guide progresses from an introduction to historical resources to information about how to identify a topic, craft a thesis and develop a research paper. Table of contents: The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Secondary Sources Primary Sources Historical Analysis What is it? Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Choose a Topic Craft a Thesis Evaluate Thesis and Sources A Variety of Information Sources Take Efficient Notes Note Cards Thinking, Organizing, Researching Parenthetical Documentation Prepare a Works Cited Page Drafting, Revising, Rewriting, Rethinking For Further Reading: Works Cited Additional Links So you want to study history?! Tons of help and links Slatta Home Page Use the Writing and other links on the lefhand menu I. The Range and Richness of Historical Sources Back to Top Every period leaves traces, what historians call "sources" or evidence. Some are more credible or carry more weight than others; judging the differences is a vital skill developed by good historians. Sources vary in perspective, so knowing who created the information you are examining is vital. Anonymous doesn't make for a very compelling source. For example, an FBI report on the antiwar movement, prepared for U.S. President Richard Nixon, probably contained secrets that at the time were thought to have affected national security. It would not be usual, however, for a journalist's article about a campus riot, featured in a local newspaper, to leak top secret information. Which source would you read? It depends on your research topic. If you're studying how government officials portrayed student activists, you'll want to read the FBI report and many more documents from other government agencies such as the CIA and the National Security Council. If you're investigating contemporary opinion of pro-war and anti-war activists, local newspaper accounts provide a rich resource. You'd want to read a variety of newspapers to ensure you're covering a wide range of opinions (rural/urban, left/right, North/South, Soldier/Draft-dodger, etc). Historians classify sources into two major categories: primary and secondary sources. Secondary Sources Back to Top Definition: Secondary sources are created by someone who was either not present when the event occurred or removed from it in time. We use secondary sources for overview information, to familiarize ourselves with a topic, and compare that topic with other events in history. In refining a research topic, we often begin with secondary sources. This helps us identify gaps or conflicts in the existing scholarly literature that might prove promsing topics. Types: History books, encyclopedias, historical dictionaries, and academic (scholarly) articles are secondary sources. To help you determine the status of a given secondary source, see How to identify and nagivate scholarly literature . Examples: Historian Marilyn Young's (NYU) book about the Vietnam War is a secondary source. She did not participate in the war. Her study is not based on her personal experience but on the evidence she culled from a variety of sources she found in the United States and Vietnam. Primary Sources Back to Top Definition: Primary sources emanate from individuals or groups who participated in or witnessed an event and recorded that event during or immediately after the event. They include speeches, memoirs, diaries, letters, telegrams, emails, proclamations, government documents, and much more. Examples: A student activist during the war writing about protest activities has created a memoir. This would be a primary source because the information is based on her own involvement in the events she describes. Similarly, an antiwar speech is a primary source. So is the arrest record of student protesters. A newspaper editorial or article, reporting on a student demonstration is also a primary source. II. Historical Analysis What is it? Back to Top No matter what you read, whether it's a primary source or a secondary source, you want to know who authored the source (a trusted scholar? A controversial historian? A propagandist? A famous person? An ordinary individual?). "Author" refers to anyone who created information in any medium (film, sound, or text). You also need to know when it was written and the kind of audience the author intend to reach. You should also consider what you bring to the evidence that you examine. Are you inductively following a path of evidence, developing your interpretation based on the sources? Do you have an ax to grind? Did you begin your research deductively, with your mind made up before even seeing the evidence. Historians need to avoid the latter and emulate the former. To read more about the distinction, examine the difference between Intellectual Inquirers and Partisan Ideologues . In the study of history, perspective is everything. A letter written by a twenty- year old Vietnam War protestor will differ greatly from a letter written by a scholar of protest movements. Although the sentiment might be the same, the perspective and influences of these two authors will be worlds apart. Practicing the " 5 Ws " will avoid the confusion of the authority trap. Who, When, Where, What and Why: The Five "W"s Back to Top Historians accumulate evidence (information, including facts, stories, interpretations, opinions, statements, reports, etc.) from a variety of sources (primary and secondary). They must also verify that certain key pieces of information are corroborated by a number of people and sources ("the predonderance of evidence"). The historian poses the " 5 Ws " to every piece of information he examines: Who is the historical actor? When did the event take place? Where did it occur? What did it entail and why did it happen the way it did? The " 5 Ws " can also be used to evaluate a primary source. Who authored the work? When was it created? Where was it created, published, and disseminated? Why was it written (the intended audience), and what is the document about (what points is the author making)? If you know the answers to these five questions, you can analyze any document, and any primary source. The historian doesn't look for the truth, since this presumes there is only one true story. The historian tries to understand a number of competing viewpoints to form his or her own interpretation-- what constitutes the best explanation of what happened and why. By using as wide a range of primary source documents and secondary sources as possible, you will add depth and richness to your historical analysis. The more exposure you, the researcher, have to a number of different sources and differing view points, the more you have a balanced and complete view about a topic in history. This view will spark more questions and ultimately lead you into the quest to unravel more clues about your topic. You are ready to start assembling information for your research paper. III. Topic, Thesis, Sources Definition of Terms Back to Top Because your purpose is to create new knowledge while recognizing those scholars whose existing work has helped you in this pursuit, you are honor bound never to commit the following academic sins: Plagiarism: Literally "kidnapping," involving the use of someone else's words as if they were your own (Gibaldi 6). To avoid plagiarism you must document direct quotations, paraphrases, and original ideas not your own. Recycling: Rehashing material you already know thoroughly or, without your professor's permission, submitting a paper that you have completed for another course. Premature cognitive commitment: Academic jargon for deciding on a thesis too soon and then seeking information to serve that thesis rather than embarking on a genuine search for new knowledge. Choose a Topic Back to Top "Do not hunt for subjects, let them choose you, not you them." --Samuel Butler Choosing a topic is the first step in the pursuit of a thesis. Below is a logical progression from topic to thesis: Close reading of the primary text, aided by secondary sources Growing awareness of interesting qualities within the primary text Choosing a topic for research Asking productive questions that help explore and evaluate a topic Creating a research hypothesis Revising and refining a hypothesis to form a working thesis First, and most important, identify what qualities in the primary or secondary source pique your imagination and curiosity and send you on a search for answers. Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive levels provides a description of productive questions asked by critical thinkers. While the lower levels (knowledge, comprehension) are necessary to a good history essay, aspire to the upper three levels (analysis, synthesis, evaluation). Skimming reference works such as encyclopedias, books, critical essays and periodical articles can help you choose a topic that evolves into a hypothesis, which in turn may lead to a thesis. One approach to skimming involves reading the first paragraph of a secondary source to locate and evaluate the author's thesis. Then for a general idea of the work's organization and major ideas read the first and last sentence of each paragraph. Read the conclusion carefully, as it usually presents a summary (Barnet and Bedau 19). Craft a Thesis Back to Top Very often a chosen topic is too broad for focused research. You must revise it until you have a working hypothesis, that is, a statement of an idea or an approach with respect to the source that could form the basis for your thesis. Remember to not commit too soon to any one hypothesis. Use it as a divining rod or a first step that will take you to new information that may inspire you to revise your hypothesis. Be flexible. Give yourself time to explore possibilities. The hypothesis you create will mature and shift as you write and rewrite your paper. New questions will send you back to old and on to new material. Remember, this is the nature of research--it is more a spiraling or iterative activity than a linear one. Test your working hypothesis to be sure it is: broad enough to promise a variety of resources. narrow enough for you to research in depth. original enough to interest you and your readers. worthwhile enough to offer information and insights of substance "do-able"--sources are available to complete the research. Now it is time to craft your thesis, your revised and refined hypothesis. A thesis is a declarative sentence that: focuses on one well-defined idea makes an arguable assertion; it is capable of being supported prepares your readers for the body of your paper and foreshadows the conclusion. Evaluate Thesis and Sources Back to Top Like your hypothesis, your thesis is not carved in stone. You are in charge. If necessary, revise it during the research process. As you research, continue to evaluate both your thesis for practicality, originality, and promise as a search tool, and secondary sources for relevance and scholarliness. The following are questions to ask during the research process: Are there many journal articles and entire books devoted to the thesis, suggesting that the subject has been covered so thoroughly that there may be nothing new to say? Does the thesis lead to stimulating, new insights? Are appropriate sources available? Is there a variety of sources available so that the bibliography or works cited page will reflect different kinds of sources? Which sources are too broad for my thesis? Which resources are too narrow? Who is the author of the secondary source? Does the critic's background suggest that he/she is qualified? After crafting a thesis, consider one of the following two approaches to writing a research paper: Excited about your thesis and eager to begin? Return to the primary or secondary source to find support for your thesis. Organize ideas and begin writing your first draft. After writing the first draft, have it reviewed by your peers and your instructor. Ponder their suggestions and return to the sources to answer still-open questions. Document facts and opinions from secondary sources. Remember, secondary sources can never substitute for primary sources. Confused about where to start? Use your thesis to guide you to primary and secondary sources. Secondary sources can help you clarify your position and find a direction for your paper. Keep a working bibliography. You may not use all the sources you record, but you cannot be sure which ones you will eventually discard. Create a working outline as you research. This outline will, of course, change as you delve more deeply into your subject. A Variety of Information Sources Back to Top "A mind that is stretched to a new idea never returns to its original dimension." --Oliver Wendell Holmes Your thesis and your working outline are the primary compasses that will help you navigate the variety of sources available. In "Introduction to the Library" (5-6) the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers suggests you become familiar with the library you will be using by: taking a tour or enrolling for a brief introductory lecture referring to the library's publications describing its resources introducing yourself and your project to the reference librarian The MLA Handbook also lists guides for the use of libraries (5), including: Jean Key Gates, Guide to the Use of Libraries and Information Sources (7th ed., New York: McGraw, 1994). Thomas Mann, A Guide to Library Research Methods (New York: Oxford UP, 1987). Online Central Catalog Most libraries have their holdings listed on a computer. The online catalog may offer Internet sites, Web pages and databases that relate to the university's curriculum. It may also include academic journals and online reference books. Below are three search techniques commonly used online: Index Search: Although online catalogs may differ slightly from library to library, the most common listings are by: Subject Search: Enter the author's name for books and article written about the author. Author Search: Enter an author's name for works written by the author, including collections of essays the author may have written about his/her own works. Title Search: Enter a title for the screen to list all the books the library carries with that title. Key Word Search/Full-text Search: A one-word search, e.g., 'Kennedy,' will produce an overwhelming number of sources, as it will call up any entry that includes the name 'Kennedy.' To focus more narrowly on your subject, add one or more key words, e.g., "John Kennedy, Peace Corps." Use precise key words. Boolean Search: Boolean Search techniques use words such as "and," "or," and "not," which clarify the relationship between key words, thus narrowing the search. Take Efficient Notes Back to Top Keeping complete and accurate bibliography and note cards during the research process is a time (and sanity) saving practice. If you have ever needed a book or pages within a book, only to discover that an earlier researcher has failed to return it or torn pages from your source, you understand the need to take good notes. Every researcher has a favorite method for taking notes. Here are some suggestions-- customize one of them for your own use. Bibliography cards There may be far more books and articles listed than you have time to read, so be selective when choosing a reference. Take information from works that clearly relate to your thesis, remembering that you may not use them all. Use a smaller or a different color card from the one used for taking notes. Write a bibliography card for every source. Number the bibliography cards. On the note cards, use the number rather than the author's name and the title. It's faster. Another method for recording a working bibliography, of course, is to create your own database. Adding, removing, and alphabetizing titles is a simple process. Be sure to save often and to create a back-up file. A bibliography card should include all the information a reader needs to locate that particular source for further study. Most of the information required for a book entry (Gibaldi 112): Author's name Title of a part of the book [preface, chapter titles, etc.] Title of the book Name of the editor, translator, or compiler Edition used Number(s) of the volume(s) used Name of the series Place of publication, name of the publisher, and date of publication Page numbers Supplementary bibliographic information and annotations Most of the information required for an article in a periodical (Gibaldi 141): Author's name Title of the article Name of the periodical Series number or name (if relevant) Volume number (for a scholarly journal) Issue number (if needed) Date of publication Page numbers Supplementary information For information on how to cite other sources refer to your So you want to study history page . Note Cards Back to Top Take notes in ink on either uniform note cards (3x5, 4x6, etc.) or uniform slips of paper. Devote each note card to a single topic identified at the top. Write only on one side. Later, you may want to use the back to add notes or personal observations. Include a topical heading for each card. Include the number of the page(s) where you found the information. You will want the page number(s) later for documentation, and you may also want page number(s)to verify your notes. Most novice researchers write down too much. Condense. Abbreviate. You are striving for substance, not quantity. Quote directly from primary sources--but the "meat," not everything. Suggestions for condensing information: Summary: A summary is intended to provide the gist of an essay. Do not weave in the author's choice phrases. Read the information first and then condense the main points in your own words. This practice will help you avoid the copying that leads to plagiarism. Summarizing also helps you both analyze the text you are reading and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses (Barnet and Bedau 13). Outline: Use to identify a series of points. Paraphrase, except for key primary source quotations. Never quote directly from a secondary source, unless the precise wording is essential to your argument. Simplify the language and list the ideas in the same order. A paraphrase is as long as the original. Paraphrasing is helpful when you are struggling with a particularly difficult passage. Be sure to jot down your own insights or flashes of brilliance. Ralph Waldo Emerson warns you to "Look sharply after your thoughts. They come unlooked for, like a new bird seen on your trees, and, if you turn to your usual task, disappear...." To differentiate these insights from those of the source you are reading, initial them as your own. (When the following examples of note cards include the researcher's insights, they will be followed by the initials N. R.) When you have finished researching your thesis and you are ready to write your paper, organize your cards according to topic. Notecards make it easy to shuffle and organize your source information on a table-- or across the floor. Maintain your working outline that includes the note card headings and explores a logical order for presenting them in your paper. IV. Begin Thinking, Researching, Organizing Back to Top Don't be too sequential. Researching, writing, revising is a complex interactive process. Start writing as soon as possible! "The best antidote to writer's block is--to write." (Klauser 15). However, you still feel overwhelmed and are staring at a blank page, you are not alone. Many students find writing the first sentence to be the most daunting part of the entire research process. Be creative. Cluster (Rico 28-49). Clustering is a form of brainstorming. Sometimes called a web, the cluster forms a design that may suggest a natural organization for a paper. Here's a graphical depiction of brainstorming . Like a sun, the generating idea or topic lies at the center of the web. From it radiate words, phrases, sentences and images that in turn attract other words, phrases, sentences and images. Put another way--stay focused. Start with your outline. If clustering is not a technique that works for you, turn to the working outline you created during the research process. Use the outline view of your word processor. If you have not already done so, group your note cards according to topic headings. Compare them to your outline's major points. If necessary, change the outline to correspond with the headings on the note cards. If any area seems weak because of a scarcity of facts or opinions, return to your primary and/or secondary sources for more information or consider deleting that heading. Use your outline to provide balance in your essay. Each major topic should have approximately the same amount of information. Once you have written a working outline, consider two different methods for organizing it. Deduction: A process of development that moves from the general to the specific. You may use this approach to present your findings. However, as noted above, your research and interpretive process should be inductive. Deduction is the most commonly used form of organization for a research paper. The thesis statement is the generalization that leads to the specific support provided by primary and secondary sources. The thesis is stated early in the paper. The body of the paper then proceeds to provide the facts, examples, and analogies that flow logically from that thesis. The thesis contains key words that are reflected in the outline. These key words become a unifying element throughout the paper, as they reappear in the detailed paragraphs that support and develop the thesis. The conclusion of the paper circles back to the thesis, which is now far more meaningful because of the deductive development that supports it. Chronological order A process that follows a traditional time line or sequence of events. A chronological organization is useful for a paper that explores cause and effect. Parenthetical Documentation Back to Top The Works Cited page, a list of primary and secondary sources, is not sufficient documentation to acknowledge the ideas, facts, and opinions you have included within your text. The MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers describes an efficient parenthetical style of documentation to be used within the body of your paper. Guidelines for parenthetical documentation: "References to the text must clearly point to specific sources in the list of works cited" (Gibaldi 184). Try to use parenthetical documentation as little as possible. For example, when you cite an entire work, it is preferable to include the author's name in the text. The author's last name followed by the page number is usually enough for an accurate identification of the source in the works cited list. These examples illustrate the most common kinds of documentation. Documenting a quotation: Ex. "The separation from the personal mother is a particularly intense process for a daughter because she has to separate from the one who is the same as herself" (Murdock 17). She may feel abandoned and angry. Note: The author of The Heroine's Journey is listed under Works Cited by the author's name, reversed--Murdock, Maureen. Quoted material is found on page 17 of that book. Parenthetical documentation is after the quotation mark and before the period. Documenting a paraphrase: Ex. In fairy tales a woman who holds the princess captive or who abandons her often needs to be killed (18). Note: The second paraphrase is also from Murdock's book The Heroine's Journey. It is not, however, necessary to repeat the author's name if no other documentation interrupts the two. If the works cited page lists more than one work by the same author, include within the parentheses an abbreviated form of the appropriate title. You may, of course, include the title in your sentence, making it unnecessary to add an abbreviated title in the citation. > Prepare a Works Cited Page Back to Top There are a variety of titles for the page that lists primary and secondary sources (Gibaldi 106-107). A Works Cited page lists those works you have cited within the body of your paper. The reader need only refer to it for the necessary information required for further independent research. Bibliography means literally a description of books. Because your research may involve the use of periodicals, films, art works, photographs, etc. "Works Cited" is a more precise descriptive term than bibliography. An Annotated Bibliography or Annotated Works Cited page offers brief critiques and descriptions of the works listed. A Works Consulted page lists those works you have used but not cited. Avoid using this format. As with other elements of a research paper there are specific guidelines for the placement and the appearance of the Works Cited page. The following guidelines comply with MLA style: The Work Cited page is placed at the end of your paper and numbered consecutively with the body of your paper. Center the title and place it one inch from the top of your page. Do not quote or underline the title. Double space the entire page, both within and between entries. The entries are arranged alphabetically by the author's last name or by the title of the article or book being cited. If the title begins with an article (a, an, the) alphabetize by the next word. If you cite two or more works by the same author, list the titles in alphabetical order. Begin every entry after the first with three hyphens followed by a period. All entries begin at the left margin but subsequent lines are indented five spaces. Be sure that each entry cited on the Works Cited page corresponds to a specific citation within your paper. Refer to the the MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers (104- 182) for detailed descriptions of Work Cited entries. Citing sources from online databases is a relatively new phenomenon. Make sure to ask your professor about citing these sources and which style to use. V. Draft, Revise, Rewrite, Rethink Back to Top "There are days when the result is so bad that no fewer than five revisions are required. In contrast, when I'm greatly inspired, only four revisions are needed." --John Kenneth Galbraith Try freewriting your first draft. Freewriting is a discovery process during which the writer freely explores a topic. Let your creative juices flow. In Writing without Teachers , Peter Elbow asserts that "[a]lmost everybody interposes a massive and complicated series of editings between the time words start to be born into consciousness and when they finally come off the end of the pencil or typewriter [or word processor] onto the page" (5). Do not let your internal judge interfere with this first draft. Creating and revising are two very different functions. Don't confuse them! If you stop to check spelling, punctuation, or grammar, you disrupt the flow of creative energy. Create; then fix it later. When material you have researched comes easily to mind, include it. Add a quick citation, one you can come back to later to check for form, and get on with your discovery. In subsequent drafts, focus on creating an essay that flows smoothly, supports fully, and speaks clearly and interestingly. Add style to substance. Create a smooth flow of words, ideas and paragraphs. Rearrange paragraphs for a logical progression of information. Transition is essential if you want your reader to follow you smoothly from introduction to conclusion. Transitional words and phrases stitch your ideas together; they provide coherence within the essay. External transition: Words and phrases that are added to a sentence as overt signs of transition are obvious and effective, but should not be overused, as they may draw attention to themselves and away from ideas. Examples of external transition are "however," "then," "next," "therefore." "first," "moreover," and "on the other hand." Internal transition is more subtle. Key words in the introduction become golden threads when they appear in the paper's body and conclusion. When the writer hears a key word repeated too often, however, she/he replaces it with a synonym or a pronoun. Below are examples of internal transition. Transitional sentences create a logical flow from paragraph to paragraph. Iclude individual words, phrases, or clauses that refer to previous ideas and that point ahead to new ones. They are usually placed at the end or at the beginning of a paragraph. A transitional paragraph conducts your reader from one part of the paper to another. It may be only a few sentences long. Each paragraph of the body of the paper should contain adequate support for its one governing idea. Speak/write clearly, in your own voice. Tone: The paper's tone, whether formal, ironic, or humorous, should be appropriate for the audience and the subject. Voice: Keep you language honest. Your paper should sound like you. Understand, paraphrase, absorb, and express in your own words the information you have researched. Avoid phony language. Sentence formation: When you polish your sentences, read them aloud for word choice and word placement. Be concise. Strunk and White in The Elements of Style advise the writer to "omit needless words" (23). First, however, you must recognize them. Keep yourself and your reader interested. In fact, Strunk's 1918 writing advice is still well worth pondering. First, deliver on your promises. Be sure the body of your paper fulfills the promise of the introduction. Avoid the obvious. Offer new insights. Reveal the unexpected. Have you crafted your conclusion as carefully as you have your introduction? Conclusions are not merely the repetition of your thesis. The conclusion of a research paper is a synthesis of the information presented in the body. Your research has led you to conclusions and opinions that have helped you understand your thesis more deeply and more clearly. Lift your reader to the full level of understanding that you have achieved. Revision means "to look again." Find a peer reader to read your paper with you present. Or, visit your college or university's writing lab. Guide your reader's responses by asking specific questions. Are you unsure of the logical order of your paragraphs? Do you want to know whether you have supported all opinions adequately? Are you concerned about punctuation or grammar? Ask that these issues be addressed. You are in charge. Here are some techniques that may prove helpful when you are revising alone or with a reader. When you edit for spelling errors read the sentences backwards. This procedure will help you look closely at individual words. Always read your paper aloud. Hearing your own words puts them in a new light. Listen to the flow of ideas and of language. Decide whether or not the voice sounds honest and the tone is appropriate to the purpose of the paper and to your audience. Listen for awkward or lumpy wording. Find the one right word, Eliminate needless words. Combine sentences. Kill the passive voice. Eliminate was/were/is/are constructions. They're lame and anti-historical. Be ruthless. If an idea doesn't serve your thesis, banish it, even if it's one of your favorite bits of prose. In the margins, write the major topic of each paragraph. By outlining after you have written the paper, you are once again evaluating your paper's organization. OK, you've got the process down. Now execute! And enjoy! It's not everyday that you get to make history. VI. For Further Reading: Works Cited Back to Top Barnet, Sylvan, and Hugo Bedau. Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing: A Brief Guide to Argument. Boston: Bedford, 1993. Brent, Doug. Reading as Rhetorical Invention: Knowledge,Persuasion and the Teaching of Research-Based Writing. Urbana: NCTE, 1992. Elbow, Peter. Writing without Teachers. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. Gibladi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers. 4th ed. New York: Modern Language Association, 1995. Horvitz, Deborah. "Nameless Ghosts: Possession and Dispossession in Beloved." Studies in American Fiction , Vol. 17, No. 2, Autum, 1989, pp. 157-167. Republished in the Literature Research Center. Gale Group. (1 January 1999). Klauser, Henriette Anne. Writing on Both Sides of the Brain: Breakthrough Techniques for People Who Write. Philadelphia: Harper, 1986. Rico, Gabriele Lusser. Writing the Natural Way: Using Right Brain Techniques to Release Your Expressive Powers. Los Angeles: Houghton, 1983. Sorenson, Sharon. The Research Paper: A Contemporary Approach. New York: AMSCO, 1994. Strunk, William, Jr., and E. B. White. The Elements of Style. 3rd ed. New York: MacMillan, 1979. Back to Top This guide adapted from materials published by Thomson Gale, publishers. For free resources, including a generic guide to writing term papers, see the Gale.com website , which also includes product information for schools.

- How it works

Historical Research – A Guide Based on its Uses & Steps

Published by Alvin Nicolas at August 16th, 2021 , Revised On August 29, 2023

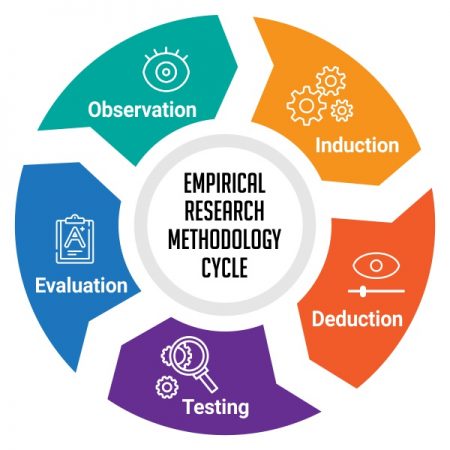

History is a study of past incidents, and it’s different from natural science. In natural science, researchers prefer direct observations. Whereas in historical research, a researcher collects, analyses the information to understand, describe, and explain the events that occurred in the past.

They aim to test the truthfulness of the observations made by others. Historical researchers try to find out what happened exactly during a certain period of time as accurately and as closely as possible. It does not allow any manipulation or control of variables .

When to Use the Historical Research Method?

You can use historical research method to:

- Uncover the unknown fact.

- Answer questions

- Identify the association between the past and present.

- Understand the culture based on past experiences..

- Record and evaluate the contributions of individuals, organisations, and institutes.

How to Conduct Historical Research?

Historical research involves the following steps:

- Select the Research Topic

- Collect the Data

- Analyse the Data

- Criticism of Data

- Present your Findings

Tips to Collect Data

Step 1 – select the research topic.

If you want to conduct historical research, it’s essential to select a research topic before beginning your research. You can follow these tips while choosing a topic and developing a research question .

- Consider your previous study as your previous knowledge and data can make your research enjoyable and comfortable for you.

- List your interests and focus on the current events to find a promising question.

- Take notes of regular activities and consider your personal experiences on a specific topic.

- Develop a question using your research topic.

- Explore your research question by asking yourself when? Why? How

Step 2- Collect the Data

It is essential to collect data and facts about the research question to get reliable outcomes. You need to select an appropriate instrument for data collection . Historical research includes two sources of data collection, such as primary and secondary sources.

Primary Sources

Primary sources are the original first-hand resources such as documents, oral or written records, witnesses to a fact, etc. These are of two types, such as:

Conscious Information : It’s a type of information recorded and restored consciously in the form of written, oral documents, or the actual witnesses of the incident that occurred in the past.

It includes the following sources:

| Records Government documents Images autobiographies letters | Constitiutions Court-decisions Diaries Audios Videos | Wills Declarations Licenses Reports |

Unconscious information : It’s a type of information restored in the form of remains or relics.

It includes information in the following forms:

| Fossils Tools Weapons Household articles Clothes or any belonging of humans | Language literature Artifacts Abandoned places Monuments |

Secondary Sources

Sometimes it’s impossible to access primary sources, and researchers rely on secondary sources to obtain information for their research.

It includes:

- Publications

- Periodicals

- Encyclopedia

Step 3 – Analyse the Data

After collecting the information, you need to analyse it. You can use data analysis methods like

- Thematic analysis

- Coding system

- Theoretical model ( Researchers use multiple theories to explain a specific phenomenon, situations, and behavior types.)

- Quantitative data to validate

Step 4 – Criticism of Data

Data criticism is a process used for identifying the validity and reliability of the collected data. It’s of two types such as:

External Criticism :

It aims at identifying the external features of the data such as signature, handwriting, language, nature, spelling, etc., of the documents. It also involves the physical and chemical tests of paper, paint, ink, metal cloth, or any collected object.

Internal Criticism :

It aims at identifying the meaning and reliability of the data. It focuses on the errors, printing, translation, omission, additions in the documents. The researchers should use both external and internal criticism to ensure the validity of the data.

Step 5 – Present your Findings

While presenting the findings of your research , you need to ensure that you have met the objectives of your research or not. Historical material can be organised based on the theme and topic, and it’s known as thematic and topical arrangement. You can follow these tips while writing your research paper :

Build Arguments and Narrative

Your research aims not just to collect information as these are the raw materials of research. You need to build a strong argument and narrate the details of past events or incidents based on your findings.

Organise your Argument

You can review the literature and other researchers’ contributions to the topic you’ve chosen to enhance your thinking and argument.

Proofread, Revise and Edit

After putting your findings on a paper, you need to proofread it to weed out the errors, rewrite it to improve, and edit it thoroughly before submitting it.

Are you looking for professional research writing services?

We hear you.

- Whether you want a full dissertation written or need help forming a dissertation proposal, we can help you with both.

- Get different dissertation services at ResearchProspect and score amazing grades!

In this world of technology, many people rely on Google to find out any information. All you have to do is enter a few keywords and sit back. You’ll find several relevant results onscreen.

It’s an effective and quick way of gathering information. Sometimes historical documents are not accessible to everyone online, and you need to visit traditional libraries to find out historical treasures. It will help you explore your knowledge along with data collection.

You can visit historical places, conduct interviews, review literature, and access primary and secondary data sources such as books, newspapers, publications, documents, etc. You can take notes while collecting the information as it helps to organise the data accurately.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Historical Research

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| It is easy to calculate and understand the obtained information. It is applied to various time periods based on industry custom. It helps in understanding current educational practices, theories, and problems based on past experiences. It helps in determining when and how a specific incident exactly happened in the past. | A researcher cannot control or manipulate the variables. It’s time-consuming Researchers cannot affect past incidents. Historical Researchers need to rely on the available data most excessively on secondary data. Researchers cannot conduct surveys and experiments in the past. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the initial steps to perform historical research.

Initial steps for historical research:

- Define research scope and period.

- Gather background knowledge.

- Identify primary and secondary sources.

- Develop research questions.

- Plan research approach.

- Begin data collection and analysis.

You May Also Like

A meta-analysis is a formal, epidemiological, quantitative study design that uses statistical methods to generalise the findings of the selected independent studies.

This post provides the key disadvantages of secondary research so you know the limitations of secondary research before making a decision.

In correlational research, a researcher measures the relationship between two or more variables or sets of scores without having control over the variables.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- Request Info

- Resource Library

How Institutions Use Historical Research Methods to Provide Historical Perspectives

An Overview of Historical Research Methods

Historical research methods enable institutions to collect facts, chronological data, and other information relevant to their interests. But historical research is more than compiling a record of past events; it provides institutions with valuable insights about the past to inform current cultural, political, and social dynamics.

Historical research methods primarily involve collecting information from primary and secondary sources. While differences exist between these sources, organizations and institutions can use both types of sources to assess historical events and provide proper context comprehensively.

Using historical research methods, historians provide institutions with historical insights that can give perspectives on the future.

Individuals interested in advancing their careers as historians can pursue an advanced degree, such as a Master of Arts in History , to help them develop a systematic understanding of historical research and learn about the use of digital tools for acquiring, accessing, and managing historical information.

Historians use historical research methods to obtain data from primary and secondary sources and, then, assess how the information contributes to understanding a historical period or event. Historical research methods are used with primary and secondary sources. Below is a description of each type of source.

What Is a Primary Source?

Primary sources—raw data containing first-person accounts and documents—are foundational to historical and academic research. Examples of primary sources include eyewitness accounts of historical events, written testimonies, public records, oral representations, legal documents, artifacts, photographs, art, newspaper articles, diaries, and letters. Individuals often can find primary sources in archives and collections in universities, libraries, and historical societies.

A primary source, also known as primary data, is often characterized by the time of its creation. For example, individuals studying the U.S. Constitution’s beginnings can use The Federalist Papers, a collection of essays by Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, written from October 1787 to May 1788, as a primary source for their research. In this example, the information was witnessed firsthand and created at the time of the event.

What Is a Secondary Source?

Primary sources are not always easy to find. In the absence of primary sources, secondary sources can play a vital role in describing historical events. A historian can create a secondary source by analyzing, synthesizing, and interpreting information or data provided in primary sources. For example, a modern-day historian may use The Federalist Papers and other primary sources to reveal historical insights about the series of events that led to the creation of the U.S. Constitution. As a result, the secondary source, based on historical facts, becomes a reliable source of historical data for others to use to create a comprehensive picture of an event and its significance.

The Value of Historical Research for Providing Historical Perspectives

Current global politics has its roots in the past. Historical research offers an essential context for understanding our modern society. It can inform global concepts, such as foreign policy development or international relations. The study of historical events can help leaders make informed decisions that impact society, culture, and the economy.

Take, for example, the Industrial Revolution. Studying the history of the rise of industry in the West helps to put the current world order in perspective. The recorded events of that age reveal that the first designers of the systems of industry, including the United States, dominated the global landscape in the following decades and centuries. Similarly, the digital revolution is creating massive shifts in international politics and society. Historians play a pivotal role in using historical research methods to record and analyze information about these trends to provide future generations with insightful historical perspectives.

In addition to creating meaningful knowledge of global and economic affairs, studying history highlights the perspectives of people and groups who triumphed over adversity. For example, the historical fights for freedom and equality, such as the struggle for women’s voting rights or ending the Jim Crow era in the South, offer relevant context for current events, such as efforts at criminal justice reform.

History also is the story of the collective identity of people and regions. Historical research can help promote a sense of community and highlight the vibrancy of different cultures, creating opportunities for people to become more culturally aware and empowered.

The Tools and Techniques of Historical Research Methods

A primary source is not necessarily an original source. For example, not everyone can access the original essays written by Hamilton because they are precious and must be preserved and protected. However, thanks to digitization, institutions can access, manage, and interpret essential information, artifacts, and images from the essays without fear of degradation.

Using technology to digitize historical information creates what is known as digital history. It offers opportunities to advance scholarly research and expand knowledge to new audiences. For example, individuals can access a digital copy of The Federalist Papers from the Library of Congress’s website anytime, from anywhere. This digital copy can still serve as a primary source because it contains the same content as the original paper version created hundreds of years ago.

As more primary and secondary sources are digitized, researchers are increasingly using artificial intelligence (AI) to search, gather, and analyze these sources. An AI method known as optical character recognition can help historians with digital research. Historians also can use AI techniques to close gaps in historical information. For example, an AI system developed by DeepMind uses deep neural networks to help historians recreate missing pieces and restore ancient Greek texts on stone tablets that are thousands of years old.

As digital tools associated with historical research proliferate, individuals seeking to advance in a history career need to develop technical skills to use advanced technology in their research. Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History program prepares students with knowledge of historical research methods and critical technology skills to advance in the field of history.

Prepare to Make an Impact

Through effective historical research methods, institutions, organizations, and individuals can learn the significance of past events and communicate important insights for a better future. In museums, government agencies, universities and colleges, nonprofits, and historical associations, the combination of technology and historical research plays a central role in extending the reach of historical information to new audiences. It can also guide leaders charged with making important decisions that can impact geopolitics, society, economic development, community building, and more.

Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History prepares students with knowledge of historical research methods and skills to use technology to advance their careers across many industries and fields of study. The program’s curriculum offers students the flexibility to choose from four concentrations—Public History, American History, World History, or Legal and Constitutional History—to customize their studies based on their career goals and personal interests.

Learn how Norwich University’s online Master of Arts in History degree can prepare individuals for career success in the field of history.

Recommended Readings

What Is Digital History? A Guide to Digital History Resources, Museums, and Job Description Old World vs. New World History: A Curriculum Comparison How to Become a Researcher

Getting Started with Primary Sources , Library of Congress What Is a Primary Source? , ThoughtCo. Full Text of The Federalist Papers , Library of Congress Digital History , The Inclusive Historian’s Handbook Historians in Archives , American Historical Association How AI Helps Historians Solve Ancient Puzzles , Financial Times

Explore Norwich University

Your future starts here.

- 30+ On-Campus Undergraduate Programs

- 16:1 Student-Faculty Ratio

- 25+ Online Grad and Undergrad Programs

- Military Discounts Available

- 22 Varsity Athletic Teams

Future Leader Camp

Join us for our challenging military-style summer camp where we will inspire you to push beyond what you thought possible:

- Session I July 13 - 21, 2024

- Session II July 27 - August 4, 2024

Explore your sense of adventure, have fun, and forge new friendships. High school students and incoming rooks, discover the leader you aspire to be – today.

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Emotions

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music and Media

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Oncology

- Medical Toxicology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Cognitive Psychology

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business Ethics

- Business and Government

- Business and Technology

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Administration

- Public Policy

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

1 Historiographic Approaches

- Published: September 2008

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter discusses a range of classical and contemporary historiographic approaches to social work and social welfare history research. These include empirical or descriptive historiography, social historiography, cultural historiography; feminist, gender-based, and queer historiography, postmodern historiography, Marxist historiography, and quantitative historiography.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 23 |

| November 2022 | 22 |

| December 2022 | 9 |

| January 2023 | 7 |

| February 2023 | 17 |

| March 2023 | 18 |

| April 2023 | 24 |

| May 2023 | 14 |

| June 2023 | 15 |

| July 2023 | 14 |

| August 2023 | 36 |

| September 2023 | 29 |

| October 2023 | 26 |

| November 2023 | 31 |

| December 2023 | 26 |

| January 2024 | 50 |

| February 2024 | 33 |

| March 2024 | 38 |

| April 2024 | 36 |

| May 2024 | 50 |

| June 2024 | 16 |

| July 2024 | 148 |

| August 2024 | 3 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us