The Root Causes of the American Revolution

The cause of the american revolution.

- America's Independent Way of Thinking

The Freedoms and Restrictions of Location

The control of government, the economic troubles, the corruption and control, the criminal justice system, grievances that led to revolution and the constitution.

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

The American Revolution began in 1775 as an open conflict between the United Thirteen Colonies and Great Britain. Many factors played a role in the colonists' desires to fight for their independence. Not only did these issues lead to war , but they also shaped the foundation of the United States of America.

No single event caused the revolution. It was, instead, a series of events that led to the war . Essentially, it began as a disagreement over the way Great Britain governed the colonies and the way the colonies thought they should be treated. Americans felt they deserved all the rights of Englishmen. The British, on the other hand, thought that the colonies were created to be used in ways that best suited the Crown and Parliament. This conflict is embodied in one of the rallying cries of the American Revolution : "No Taxation Without Representation."

America's Independent Way of Thinking

In order to understand what led to the rebellion, it's important to look at the mindset of the founding fathers . It should also be noted that this mindset was not that of the majority of colonists. There were no pollsters during the American revolution, but it's safe to say its popularity rose and fell over the course of the war. Historian Robert M. Calhoon estimated that only about 40–45% of the free population supported the revolution, while about 15–20% of the free white males remained loyal.

The 18th century is known historically as the age of Enlightenment . It was a period when thinkers, philosophers, statesman, and artists began to question the politics of government, the role of the church, and other fundamental and ethical questions of society as a whole. The period was also known as the Age of Reason, and many colonists followed this new way of thinking.

A number of the revolutionary leaders had studied major writings of the Enlightenment, including those of Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, and the Baron de Montesquieu. From these thinkers, the founders gleaned such new political concepts as the social contract , limited government, the consent of the governed, and the separation of powers .

Locke's writings, in particular, struck a chord. His books helped to raise questions about the rights of the governed and the overreach of the British government. They spurred the "republican" ideology that stood up in opposition to those viewed as tyrants.

Men such as Benjamin Franklin and John Adams were also influenced by the teachings of the Puritans and Presbyterians. These teachings included such new radical ideas as the principle that all men are created equal and the belief that a king has no divine rights. Together, these innovative ways of thinking led many in this era to consider it their duty to rebel against laws they viewed as unjust.

The geography of the colonies also contributed to the revolution. Their distance from Great Britain naturally created a sense of independence that was hard to overcome. Those willing to colonize the new world generally had a strong independent streak with a profound desire for new opportunities and more freedom.

The Proclamation of 1763 played its own role. After the French and Indian War , King George III issued the royal decree that prevented further colonization west of the Appalachian Mountains. The intent was to normalize relations with the Indigenous peoples, many of whom fought with the French.

A number of settlers had purchased land in the now forbidden area or had received land grants. The crown's proclamation was largely ignored as settlers moved anyway and the "Proclamation Line" eventually moved after much lobbying. Despite this concession, the affair left another stain on the relationship between the colonies and Britain.

The existence of colonial legislatures meant that the colonies were in many ways independent of the crown. The legislatures were allowed to levy taxes, muster troops, and pass laws. Over time, these powers became rights in the eyes of many colonists.

The British government had different ideas and attempted to curtail the powers of these newly elected bodies. There were numerous measures designed to ensure the colonial legislatures did not achieve autonomy, although many had nothing to do with the larger British Empire . In the minds of colonists, they were a matter of local concern.

From these small, rebellious legislative bodies that represented the colonists, the future leaders of the United States were born.

Even though the British believed in mercantilism , Prime Minister Robert Walpole espoused a view of " salutary neglect ." This system was in place from 1607 through 1763, during which the British were lax on enforcement of external trade relations. Walpole believed this enhanced freedom would stimulate commerce.

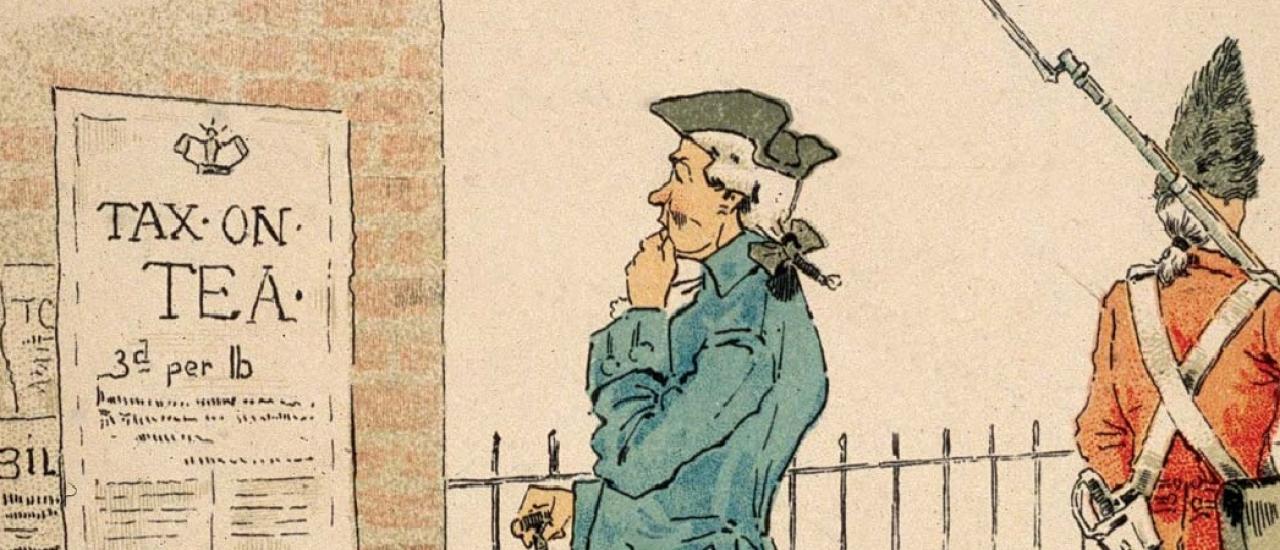

The French and Indian War led to considerable economic trouble for the British government. Its cost was significant, and the British were determined to make up for the lack of funds. They levied new taxes on the colonists and increased trade regulations. These actions were not well received by the colonists.

New taxes were enforced, including the Sugar Act and the Currency Act , both in 1764. The Sugar Act increased already considerable taxes on molasses and restricted certain export goods to Britain alone. The Currency Act prohibited the printing of money in the colonies, making businesses rely more on the crippled British economy.

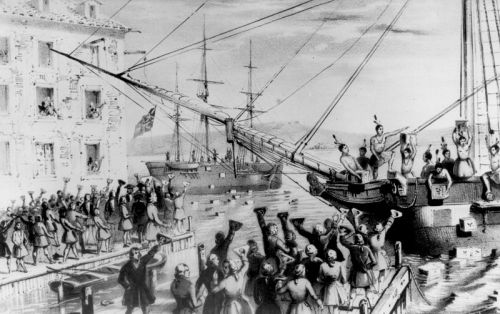

Feeling underrepresented, overtaxed, and unable to engage in free trade, the colonists rallied to the slogan, "No Taxation Without Representation." This discontent became very apparent in 1773 with the events that later became known as the Boston Tea Party .

The British government's presence became increasingly more visible in the years leading to the revolution. British officials and soldiers were given more control over the colonists and this led to widespread corruption.

Among the most glaring of these issues were the "Writs of Assistance." These were general search warrants that gave British soldiers the right to search and seize any property they deemed to be smuggled or illegal goods. Designed to assist the British in enforcing trade laws, these documents allowed British soldiers to enter, search, and seize warehouses, private homes, and ships whenever necessary. However, many abused this power.

In 1761, Boston lawyer James Otis fought for the constitutional rights of the colonists in this matter but lost. The defeat only inflamed the level of defiance and ultimately led to the Fourth Amendment in the U.S. Constitution .

The Third Amendment was also inspired by the overreach of the British government. Forcing colonists to house British soldiers in their homes infuriated the population. It was inconvenient and costly to the colonists, and many also found it a traumatic experience after events like the Boston Massacre in 1770 .

Trade and commerce were overly controlled, the British Army made its presence known, and the local colonial government was limited by a power far across the Atlantic Ocean. If these affronts to the colonists' dignity were not enough to ignite the fires of rebellion, American colonists also had to endure a corrupt justice system.

Political protests became a regular occurrence as these realities set in. In 1769, Alexander McDougall was imprisoned for libel when his work "To the Betrayed Inhabitants of the City and Colony of New York" was published. His imprisonment and the Boston Massacre were just two infamous examples of the measures the British took to crack down on protesters.

After six British soldiers were acquitted and two dishonorably discharged for the Boston Massacre—ironically enough, they were defended by John Adams—the British government changed the rules. From then on, officers accused of any offense in the colonies would be sent to England for trial. This meant that fewer witnesses would be on hand to give their accounts of events and it led to even fewer convictions.

To make matters even worse, jury trials were replaced with verdicts and punishments handed down directly by colonial judges. Over time, the colonial authorities lost power over this as well because the judges were known to be chosen, paid, and supervised by the British government. The right to a fair trial by a jury of their peers was no longer possible for many colonists.

All of these grievances that colonists had with the British government led to the events of the American Revolution. And many of these grievances directly affected what the founding fathers wrote into the U.S. Constitution . These constitutional rights and principles reflect the hopes of the framers that the new American government would not subject their citizens to the same loss of freedoms that the colonists had experienced under Britain's rule.

Schellhammer, Michael. " John Adams's Rule of Thirds ." Critical Thinking, Journal of the American Revolution . 11 Feb. 2013.

Calhoon, Robert M. " Loyalism and Neutrality ." A Companion to the American Revolution , edited by Jack P. Greene and J. R. Pole, Wiley, 2008, pp. 235-247, doi:10.1002/9780470756454.ch29

- The Road to the American Revolution

- Major Events That Led to the American Revolution

- The Declaration of Independence

- American Revolution: The Townshend Acts

- Continental Congress: History, Significance, and Purpose

- The History of British Taxation in the American Colonies

- What Was the Sugar Act? Definition and History

- All About the Sons of Liberty

- American Revolution: The Boston Massacre

- American Revolution: The Stamp Act of 1765

- Quartering Act, British Laws Opposed by American Colonists

- American Revolution: Boston Tea Party

- The Currency Act of 1764

- French & Indian/Seven Years' War

- The Original 13 U.S. States

- Questions Left by The Boston Massacre

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.3: The Causes of the American Revolution

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9360

- American YAWP

- Stanford via Stanford University Press

Most immediately, the American Revolution resulted directly from attempts to reform the British Empire after the Seven Years’ War. The Seven Years’ War culminated nearly a half century of war between Europe’s imperial powers. It was truly a world war, fought between multiple empires on multiple continents. At its conclusion, the British Empire had never been larger. Britain now controlled the North American continent east of the Mississippi River, including French Canada. It had also consolidated its control over India. But the realities and responsibilities of the postwar empire were daunting. War (let alone victory) on such a scale was costly. Britain doubled the national debt to 13.5 times its annual revenue. Britain faced significant new costs required to secure and defend its far-flung empire, especially the western frontiers of the North American colonies. These factors led Britain in the 1760s to attempt to consolidate control over its North American colonies, which, in turn, led to resistance.

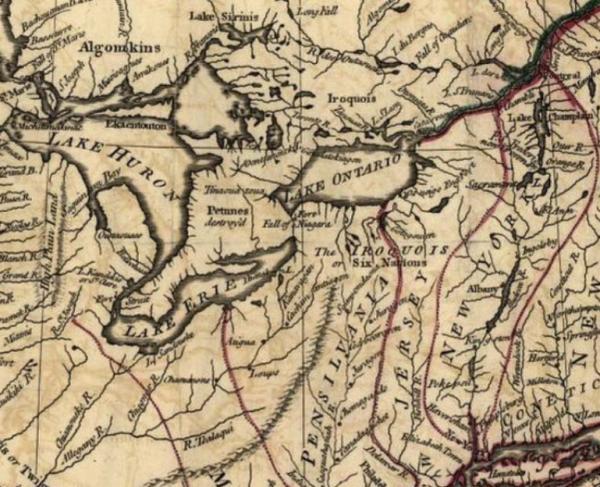

King George III took the crown in 1760 and brought Tories into his government after three decades of Whig rule. They represented an authoritarian vision of empire in which colonies would be subordinate. The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was Britain’s first major postwar imperial action targeting North America. The king forbade settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains in an attempt to limit costly wars with Native Americans. Colonists, however, protested and demanded access to the territory for which they had fought alongside the British.

In 1764, Parliament passed two more reforms. The Sugar Act sought to combat widespread smuggling of molasses in New England by cutting the duty in half but increasing enforcement. Also, smugglers would be tried by vice-admiralty courts and not juries. Parliament also passed the Currency Act, which restricted colonies from producing paper money. Hard money, such as gold and silver coins, was scarce in the colonies. The lack of currency impeded the colonies’ increasingly sophisticated transatlantic economies, but it was especially damaging in 1764 because a postwar recession had already begun. Between the restrictions of the Proclamation of 1763, the Currency Act, and the Sugar Act’s canceling of trials-by-jury for smugglers, some colonists began to fear a pattern of increased taxation and restricted liberties.

In March 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act. The act required that many documents be printed on paper that had been stamped to show the duty had been paid, including newspapers, pamphlets, diplomas, legal documents, and even playing cards. The Sugar Act of 1764 was an attempt to get merchants to pay an already existing duty, but the Stamp Act created a new, direct (or “internal”) tax. Parliament had never before directly taxed the colonists. Instead, colonies contributed to the empire through the payment of indirect, “external” taxes, such as customs duties. In 1765, Daniel Dulany of Maryland wrote, “A right to impose an internal tax on the colonies, without their consent for the single purpose of revenue, is denied, a right to regulate their trade without their consent is, admitted.” 7 Also, unlike the Sugar Act, which primarily affected merchants, the Stamp Act directly affected numerous groups throughout colonial society, including printers, lawyers, college graduates, and even sailors who played cards. This led, in part, to broader, more popular resistance.

Resistance to the Stamp Act took three forms, distinguished largely by class: legislative resistance by elites, economic resistance by merchants, and popular protest by common colonists. Colonial elites responded by passing resolutions in their assemblies. The most famous of the anti-Stamp Act resolutions were the Virginia Resolves, passed by the House of Burgesses on May 30, 1765, which declared that the colonists were entitled to “all the liberties, privileges, franchises, and immunities . . . possessed by the people of Great Britain.” When the Virginia Resolves were printed throughout the colonies, however, they often included a few extra, far more radical resolutions not passed by the Virginia House of Burgesses, the last of which asserted that only “the general assembly of this colony have any right or power to impose or lay any taxation” and that anyone who argued differently “shall be deemed an enemy to this his majesty’s colony.” 8 These additional items spread throughout the colonies and helped radicalize subsequent responses in other colonial assemblies. These responses eventually led to the calling of the Stamp Act Congress in New York City in October 1765. Nine colonies sent delegates, who included Benjamin Franklin, John Dickinson, Thomas Hutchinson, Philip Livingston, and James Otis. 9

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=397&height=438)

The Stamp Act Congress issued a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances,” which, like the Virginia Resolves, declared allegiance to the king and “all due subordination” to Parliament but also reasserted the idea that colonists were entitled to the same rights as Britons. Those rights included trial by jury, which had been abridged by the Sugar Act, and the right to be taxed only by their own elected representatives. As Daniel Dulany wrote in 1765, “It is an essential principle of the English constitution, that the subject shall not be taxed without his consent.” 10 Benjamin Franklin called it the “prime Maxim of all free Government.” 11 Because the colonies did not elect members to Parliament, they believed that they were not represented and could not be taxed by that body. In response, Parliament and the Crown argued that the colonists were “virtually represented,” just like the residents of those boroughs or counties in England that did not elect members to Parliament. However, the colonists rejected the notion of virtual representation, with one pamphleteer calling it a “monstrous idea.” 12

The second type of resistance to the Stamp Act was economic. While the Stamp Act Congress deliberated, merchants in major port cities were preparing nonimportation agreements, hoping that their refusal to import British goods would lead British merchants to lobby for the repeal of the Stamp Act. In New York City, “upwards of two hundred principal merchants” agreed not to import, sell, or buy “any goods, wares, or merchandises” from Great Britain. 13 In Philadelphia, merchants gathered at “a general meeting” to agree that “they would not Import any Goods from Great-Britain until the Stamp-Act was Repealed.” 14 The plan worked. By January 1766, London merchants sent a letter to Parliament arguing that they had been “reduced to the necessity of pending ruin” by the Stamp Act and the subsequent boycotts. 15

The third, and perhaps, most crucial type of resistance was popular protest. Riots broke out in Boston. Crowds burned the appointed stamp distributor for Massachusetts, Andrew Oliver, in effigy and pulled a building he owned “down to the Ground in five minutes.” 16 Oliver resigned the position the next day. The following week, a crowd also set upon the home of his brother-in-law, Lieutenant Governor Thomas Hutchinson, who had publicly argued for submission to the stamp tax. Before the evening was over, much of Hutchinson’s home and belongings had been destroyed. 17

Popular violence and intimidation spread quickly throughout the colonies. In New York City, posted notices read:

PRO PATRIA, The first Man that either distributes or makes use of Stampt Paper, let him take care of his House, Person, & Effects. Vox Populi; We dare.” 18

By November 16, all of the original twelve stamp distributors had resigned, and by 1766, groups calling themselves the Sons of Liberty were formed in most colonies to direct and organize further resistance. These tactics had the dual effect of sending a message to Parliament and discouraging colonists from accepting appointments as stamp collectors. With no one to distribute the stamps, the act became unenforceable.

.png?revision=1&size=bestfit&width=423&height=545)

Pressure on Parliament grew until, in February 1766, it repealed the Stamp Act. But to save face and to try to avoid this kind of problem in the future, Parliament also passed the Declaratory Act, asserting that Parliament had the “full power and authority to make laws . . . to bind the colonies and people of America . . . in all cases whatsoever.” However, colonists were too busy celebrating the repeal of the Stamp Act to take much notice of the Declaratory Act. In New York City, the inhabitants raised a huge lead statue of King George III in honor of the Stamp Act’s repeal. It could be argued that there was no moment at which colonists felt more proud to be members of the free British Empire than 1766. But Britain still needed revenue from the colonies. 19

The colonies had resisted the implementation of direct taxes, but the Declaratory Act reserved Parliament’s right to impose them. And, in the colonists’ dispatches to Parliament and in numerous pamphlets, they had explicitly acknowledged the right of Parliament to regulate colonial trade. So Britain’s next attempt to draw revenues from the colonies, the Townshend Acts, were passed in June 1767, creating new customs duties on common items, like lead, glass, paint, and tea, instead of direct taxes. The acts also created and strengthened formal mechanisms to enforce compliance, including a new American Board of Customs Commissioners and more vice-admiralty courts to try smugglers. Revenues from customs seizures would be used to pay customs officers and other royal officials, including the governors, thereby incentivizing them to convict offenders. These acts increased the presence of the British government in the colonies and circumscribed the authority of the colonial assemblies, since paying the governor’s salary had long given the assemblies significant power over them. Unsurprisingly, colonists, once again, resisted.

Even though these were duties, many colonial resistance authors still referred to them as “taxes,” because they were designed primarily to extract revenues from the colonies not to regulate trade. John Dickinson, in his “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania,” wrote, “That we may legally be bound to pay any general duties on these commodities, relative to the regulation of trade, is granted; but we being obliged by her laws to take them from Great Britain, any special duties imposed on their exportation to us only, with intention to raise a revenue from us only, are as much taxes upon us, as those imposed by the Stamp Act.” Hence, many authors asked: once the colonists assented to a tax in any form , what would stop the British from imposing ever more and greater taxes on the colonists? 20

New forms of resistance emerged in which elite, middling, and working-class colonists participated together. Merchants reinstituted nonimportation agreements, and common colonists agreed not to consume these same products. Lists were circulated with signatories promising not to buy any British goods. These lists were often published in newspapers, bestowing recognition on those who had signed and led to pressure on those who had not.

Women, too, became involved to an unprecedented degree in resistance to the Townshend Acts. They circulated subscription lists and gathered signatures. The first political commentaries in newspapers written by women appeared. 21 Also, without new imports of British clothes, colonists took to wearing simple, homespun clothing. Spinning clubs were formed, in which local women would gather at one of their homes and spin cloth for homespun clothing for their families and even for the community. 22

Homespun clothing quickly became a marker of one’s virtue and patriotism, and women were an important part of this cultural shift. At the same time, British goods and luxuries previously desired now became symbols of tyranny. Nonimportation and, especially, nonconsumption agreements changed colonists’ cultural relationship with the mother country. Committees of Inspection monitored merchants and residents to make sure that no one broke the agreements. Offenders could expect to be shamed by having their names and offenses published in the newspaper and in broadsides.

Nonimportation and nonconsumption helped forge colonial unity. Colonies formed Committees of Correspondence to keep each other informed of the resistance efforts throughout the colonies. Newspapers reprinted exploits of resistance, giving colonists a sense that they were part of a broader political community. The best example of this new “continental conversation” came in the wake of the Boston Massacre. Britain sent regiments to Boston in 1768 to help enforce the new acts and quell the resistance. On the evening of March 5, 1770, a crowd gathered outside the Custom House and began hurling insults, snowballs, and perhaps more at the young sentry. When a small number of soldiers came to the sentry’s aid, the crowd grew increasingly hostile until the soldiers fired. After the smoke cleared, five Bostonians were dead, including one of the ringleaders, Crispus Attucks, a former slave turned free dockworker. The soldiers were tried in Boston and won acquittal, thanks, in part, to their defense attorney, John Adams. News of the Boston Massacre spread quickly through the new resistance communication networks, aided by a famous engraving initially circulated by Paul Revere, which depicted bloodthirsty British soldiers with grins on their faces firing into a peaceful crowd. The engraving was quickly circulated and reprinted throughout the colonies, generating sympathy for Boston and anger with Britain.

.png?revision=1)

Resistance again led to repeal. In March 1770, Parliament repealed all of the new duties except the one on tea, which, like the Declaratory Act, was left, in part, to save face and assert that Parliament still retained the right to tax the colonies. The character of colonial resistance had changed between 1765 and 1770. During the Stamp Act resistance, elites wrote resolves and held congresses while violent, popular mobs burned effigies and tore down houses, with minimal coordination between colonies. But methods of resistance against the Townshend Acts became more inclusive and more coordinated. Colonists previously excluded from meaningful political participation now gathered signatures, and colonists of all ranks participated in the resistance by not buying British goods and monitoring and enforcing the boycotts.

Britain’s failed attempts at imperial reform in the 1760s created an increasingly vigilant and resistant colonial population and, most importantly, an enlarged political sphere—both on the colonial and continental levels—far beyond anything anyone could have imagined a few years earlier. A new sense of shared grievances began to join the colonists in a shared American political identity.

America's Wars, Causes of

Terminology, reference sources, search suggestions, primary sources.

- War of 1812

- Mexican War

- Spanish-American War

- World War I

- World War II

- Vietnam War

- Persian Gulf Wars

Poli Sci and Peace Studies Librarian

Hesburgh Library 148 Hesburgh Library University of Notre Dame Notre Dame, IN 46556

(574) 631-8901 [email protected]

- American Revolution

- American Revolutionary War

- American War for Independence

- Revolutionary War (United States)

- The American Revolution by Gordon S. Wood ISBN: 9781598533774 Publication Date: 2015-07-28 The volume includes an introduction, headnotes, a chronology of events, biographical notes about the writers, and detailed explanatory notes, all prepared by our leading expert on the American Revolution. As a special feature, each pamphlet is preceded by a typographic reproduction of its original title page.

- The American Revolution 1775-1783 by Richard L. Blanco (Editor) Call Number: 10th Floor Reading Room E 208 .A433 1993 ISBN: 082405623X Publication Date: 1993-03-01 ... this panoramic reference comprises some 700 detailed mini-essays on battles, campaigns, skirmishes, raids, massacres, and sea fights, along with approximately 400 biographical sketches.

- Atlas of early American history : the Revolutionary era, 1760-1790 by Lester Jesse Cappon Publication Date: 1976

- Atlas of the American Revolution by Kenneth Nebenzahl Publication Date: 1974

- Blackwell Encyclopedia of the American Revolution by Jack P. Greene (Editor); J. R. Pole (Editor) ISBN: 1557862443 Publication Date: 1992-04-15 This encyclopedia, to which many of the foremost scholars in the field have contributed, describes clearly and readably the many different ideas and events that constitute what we know as the American Revolution. Equally suitable for browsing and as a reference source, and illustrated with many paintings, drawings and documents of the period, this substantial volume is likely to remain a standard work on the subject for many years to come.

- The Encyclopedia of Colonial and Revolutionary America by John Mack Faragher (Editor) ISBN: 0816017441 Publication Date: 1988-12-01 Spanning the entire colonial period - from the earliest settlements of the 16th century to the 1783 Treaty of Paris, which concluded the American Revolution - this reference work contains 1500 alphabetical entries. The ideas, events, people and developments which defined the birth of the United States have been brought together in a volume which emphasizes key discoveries, battles and trends which shaped the era.

- Encyclopedia of the American Revolution by Mark Mayo Boatner Publication Date: 1966

- The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution by Ian Barnes; Charles Royster (Editor) Call Number: Reference Collection [2nd Floor] E 208 .B36 2000 ISBN: 0415922437 Publication Date: 2000-08-03

- Historical Dictionary of the American Revolution by Terry M. Mays ISBN: 0810834049 Publication Date: 1999-01-14 The Southern campaigns from 1778 to 1781, which are often scantily detailed in American Revolution histories, receive full discussion in this dictionary.

- New American Revolution Handbook by Theodore P. Savas; J. David Dameron ISBN: 9781611210620 Publication Date: 2010-07-01 "The authors use clear and concise writing broken down into short and easy to understand chapters complete with original maps, tables, charts, and dozens of drawings to trace the history of the Revolution from the beginning of the conflict through the final surrender in 1783."

- The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution by Edward G. Gray (Editor); Jane Kamensky (Editor) ISBN: 9780199746705 Publication Date: 2012-12-06 The Oxford Handbook of the American Revolution introduces scholars, students and generally interested readers to the formative event in American history. In thirty-three individual essays, by thirty-three authorities on the Revolution, the Handbook provides readers with in-depth analysis ofthe Revolution's many sides, ranging from the military and diplomatic to the social and political; from the economic and financial, to the cultural and legal.

Books, Documents, Videos, etc.

For materials held by Notre Dame analyzing the causes of the revolution use:

- Advanced Search

- and enter:

- United States History Revolution, 1775-1783 Causes

For materials providing contemporary (1750-1785) opinion & analysis use:

- "great britain" OR england OR "united kingdom") AND ("united states" OR america*) AND relations AND causes

- "great britain" AND ("united states" OR america*) AND colonies AND [ an issue OR topic OR colony name ]

- Use "facets" (left column) to further narrow results

For materials held by other libraries:

- Repeat search in WorldCat

For scholarly articles:

In one or more of the recommended article databases

- ("united states" OR america*) AND (revolution* OR independence) AND (cause* OR origin OR origins)

- ("great britain" OR engl*) AND ("united states" OR america*) AND colonies AND [ an issue OR topic OR colony name, e.g. taxation]

- limit search terms to title, subject or abstract,

- adjust search by adding or removing or modifying search terms, and/or

- limiting search results to "peer reviewed" or "refereed" articles.

For contemporaneous popular opinion & analysis (1750 - 1785):

- adjust search by adding or removing or modifying search terms

Tip: Do not truncate (use the *) with origin. This will retrieve "original" material dealing with the actual conduct of the war rather than its causes. Therefore it may produce many irrelevant records.

Sample Published Collections of Primary Source Materials

- The road to independence : a documentary history of the causes of the American Revolution: 1763-1776 by John. Braeman Publication Date: 1963 Hesburgh Library Lower Level (Ranges 1 - 38) (E 203 .B812 )

- The American Revolution by John H. Rhodehamel (Editor) Call Number: General Collection E 203 .A579 2001 ISBN: 1883011914 Publication Date: 2001-04-01 Drawn from letters, diaries, newspaper articles, public declarations, contemporary narratives, and private memoranda this title brings together over 120 pieces by more than 70 participants to create a unique literary panorama of the War of Independence. It includes a chronology of events, biographical and explanatory notes, and an index.

- Sources and documents illustrating the American revolution, 1764-1788, and the formation of the federal Constitution by Samuel Eliot Morison Publication Date: 1929 General Collection E 203 .M826s

- Declaration of Independence in Historical Context by Barry Alan Shain ISBN: 0300159056 Publication Date: 2014-01-01 General Collection E 221 .D38 2014

- The Remembrancer, or impartial repository of public events Publication Date: 1775 Microforms [Lower Level] Newspaper Collection Microfilm N13 reel 5863-5865

- The American Revolution by Gordon S. Wood Call Number: General Collection E 203 .A5787 2015 ISBN: 9781598533774 Publication Date: 2015-07-28 "a landmark collection of British and American pamphlets from the political debate that divided an empire and created a nation... The volume includes an introduction, headnotes, a chronology of events, biographical notes about the writers, and detailed explanatory notes... As a special feature, each pamphlet is preceded by a typographic reproduction of its original title page."

For other collections of primary source held by Notre Dame use:

- united states history revolution, 1775-1783

- (cause* OR origin OR origins) AND ( sources OR documents)

Tip: Do not truncate (use the *) with origin. This will retrieve "original" material dealing with the actual conduct of the war rather than its causes. Therefore it may produce many irrelevant records.

Also see the "American Memory" project at Library of Congress Collections .

- A complete collection of all the protests of the peers in Parliament, entered on their journals, since the year 1774, on the great questions of the cause and issue of the war between Great-Britain and America, &c to the present time.

- Journal of the Committee of the States containing the proceedings from the first Friday in June, 1784, to the second Friday in August, 1784. Published by order of Congress

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: War of 1812 >>

- Last Updated: Oct 26, 2023 9:33 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.nd.edu/causes-of-american-wars

Need help? Ask us.

Report a problem

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

7 Events That Enraged Colonists and Led to the American Revolution

By: Patrick J. Kiger

Updated: September 5, 2023 | Original: August 20, 2019

The American colonists’ breakup with the British Empire in 1776 wasn’t a sudden, impetuous act. Instead, the banding together of the 13 colonies to fight and win a war of independence against the Crown was the culmination of a series of events, which had begun more than a decade earlier. Escalations began shortly after the end of the French and Indian War —known elsewhere as the Seven Years War in 1763. Here are a few of the pivotal moments that caused the American Revolution.

1. The Stamp Act (March 1765)

To recoup some of the massive debt left over from the war with France, Parliament passed laws such as the Stamp Act , which for the first time taxed a wide range of transactions in the colonies.

“Up until then, each colony had its own government which decided which taxes they would have, and collected them,” explains Willard Sterne Randall , a professor emeritus of history at Champlain College and author of numerous works on early American history, including Unshackling America: How the War of 1812 Truly Ended the American Revolution. “They felt that they’d spent a lot of blood and treasure to protect the colonists from the Indians, and so they should pay their share.”

The colonists didn’t see it that way. They resented not only having to buy goods from the British but pay tax on them as well. “The tax never got collected, because there were riots all over the place,” Randall says. Ultimately, Benjamin Franklin convinced the British to rescind it, but that only made things worse. “That made the Americans think they could push back against anything the British wanted,” Randall says.

2. The Townshend Acts (June-July 1767)

Parliament again tried to assert its authority by passing legislation to tax goods that the Americans imported from Great Britain. The Crown established a board of customs commissioners to stop smuggling and corruption among local officials in the colonies, who were often in on the illicit trade.

Americans struck back by organizing a boycott of the British goods that were subject to taxation and began harassing the British customs commissioners. In an effort to quell the resistance, the British sent troops to occupy Boston, which only deepened the ill feeling.

3. The Boston Massacre (March 1770)

Simmering tensions between the British occupiers and Boston residents boiled over one late afternoon when a disagreement between an apprentice wigmaker and a British soldier led to a crowd of 200 colonists surrounding seven British troops. When the Americans began taunting the British and throwing things at them, the soldiers apparently lost their cool and began firing into the crowd .

As the smoke cleared, three men—including an African American sailor named Crispus Attucks —were dead, and two others were mortally wounded. The massacre became a useful propaganda tool for the colonists, especially after Paul Revere distributed an engraving that misleadingly depicted the British as the aggressors.

4. The Boston Tea Party (December 1773)

The British eventually withdrew their forces from Boston and repealed much of the onerous Townshend legislation. But they left in place the tax on tea, and in 1773 enacted a new law, the Tea Act , to prop up the financially struggling British East India Company. The act gave the company extended favorable treatment under tax regulations to sell tea at a price that undercut the American merchants who imported from Dutch traders.

That didn’t sit well with Americans. “They didn’t want the British telling them that they had to buy their tea, but it wasn’t just about that,” Randall explains. “The Americans wanted to be able to trade with any country they wanted.”

The Sons of Liberty , a radical group, decided to confront the British head-on. Thinly disguised as Mohawks, they boarded three ships in Boston harbor and destroyed more than 92,000 pounds of British tea by dumping it into the harbor . To make the point that they were rebels rather than vandals, they avoided harming any of the crew or damaging the ships themselves, and the next day even replaced a padlock that had been broken.

Nevertheless, the act of defiance “really ticked off the British government,” Randall explains. “Many of the East India Company’s shareholders were members of Parliament. They each had paid 1,000 pounds sterling—that would probably be about a million dollars now—for a share of the company, to get a piece of the action from all this tea that they were going to force down the colonists’ throats. So when these bottom-of-the-rung people in Boston destroyed their tea, that was a serious thing to them.”

5. The Coercive Acts (March-June 1774)

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the British government decided that it had to tame the rebellious colonists in Massachusetts . In the spring of 1774, Parliament passed a series of laws, the Coercive Acts , which closed Boston Harbor until restitution was paid for the destroyed tea, replaced the colony’s elected council with one appointed by the British, gave sweeping powers to the British military governor General Thomas Gage, and forbade town meetings without approval.

Yet another provision protected British colonial officials who were charged with capital offenses from being tried in Massachusetts, instead requiring that they be sent to another colony or back to Great Britain for trial.

But perhaps the most provocative provision was the Quartering Act , which allowed British military officials to demand accommodations for their troops in unoccupied houses and buildings in towns, rather than having to stay out in the countryside. While it didn’t force the colonists to board troops in their own homes , they had to pay for the expense of housing and feeding the soldiers. The quartering of troops eventually became one of the grievances cited in the Declaration of Independence .

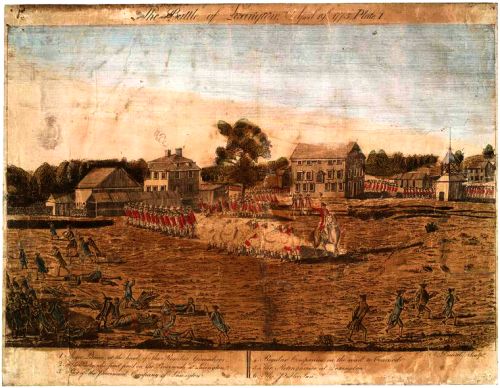

6. Lexington and Concord (April 1775)

British General Thomas Gage led a force of British soldiers from Boston to Lexington, where he planned to capture colonial radical leaders Sam Adams and John Hancock , and then head to Concord and seize their gunpowder. But American spies got wind of the plan, and with the help of riders such as Paul Revere , word spread to be ready for the British.

On the Lexington Common, the British force was confronted by 77 American militiamen , and they began shooting at each other. Seven Americans died, but other militiamen managed to stop the British at Concord and continued to harass them on their retreat back to Boston.

The British lost 73 dead, with another 174 wounded and 26 missing in action. The bloody encounter proved to the British that the colonists were fearsome foes who had to be taken seriously. It was the start of America’s war of independence.

7. British attacks on coastal towns (October 1775-January 1776)

Though the Revolutionary War’s hostilities started with Lexington and Concord, Randall says that at the start, it was unclear whether the southern colonies, whose interests didn’t necessarily align with the northern colonies, would be all in for a war of independence.

“The southerners were totally dependent upon the English to buy their crops, and they didn’t trust the Yankees,” he explains. “And in New England, the Puritans thought the southerners were lazy.”

But that was before the brutal British naval bombardments and burning of the coastal towns of Falmouth, Massachusetts and Norfolk, Virginia helped to unify the colonies. In Falmouth, where townspeople had to grab their possessions and flee for their lives, northerners had to face up to “the fear that the British would do whatever they wanted to them,” Randall says.

As historian Holger Hoock has written , the burning of Falmouth shocked General George Washington , who denounced it as “exceeding in barbarity & cruelty every hostile act practiced among civilized nations.”

Similarly, in Norfolk, the horror of the town’s wooden buildings going up in flames after a seven-hour naval bombardment shocked the southerners, who also knew that the British were offering African Americans their freedom if they took up arms on the loyalist side. “Norfolk stirred up fears of a slave insurrection in the South,” Randall says.

Leaders of the rebellion seized the burnings of the two ports to make the argument that the colonists needed to band together for survival against a ruthless enemy and embrace the need for independence. This spirit ultimately would lead to their victory.

HISTORY Vault: The American Revolution

Stream American Revolution documentaries and your favorite HISTORY series, commercial-free.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Causes of the American Revolution Essay

1775 was the year that saw disagreements explode amid the United States’ colonized states, and the colonizer Great Britain. The phrase “no taxation without representation” is very familiar. The colonies succeeded in getting their independence by the signing of the Treaty of Paris that brought the war to stop. Whereas we cannot point to one particular action as the real cause of the American Revolution, the war was ignited by the way Great Britain treated the thirteen united colonies in comparison to the treatment that the colonies anticipated from Great Britain. The Americans had a feeling that they were equal to the Englishmen, and thus entitled to the same rights (Wood, 2002, p 123-125). On their part, the British had it that the Americans existed to be used according to the stipulation of the parliament, as well as the crown. This disagreement is carried in the American slogan, “no taxation without representation.”

We can look at the independent way of thinking by the American founding fathers. Firstly, geographically, the distance between the colonies and Great Britain made independence that could rarely be overcome. The colonizers were searching for new fertile lands as well as exploring new opportunities, and also being in the free world. Secondly, the presence of colonial legislators implied that the colonies were variously crown independent. Passing of laws, the mustering of the soldier troops, and levying of taxes was under the mandate of legislators. With time, these powers were considered rights. When they were denied by the British, disagreements set in between the groups. The leaders to be in the United States came out of their mothers’ wombs during this era of legislatures.

Thirdly, it was the issue of salutary neglect. Despite the belief strongly held by the British with regard to the leader then (Prime Minister Robert Walpole) favored the “salutary neglect.” This is a structure that promoted negligence in the actual enforcement of the relation to the outside or international trade. He had at the back of his mind that with this liberalism, trade would be triggered even more. Finally, there was the issue of enlightenment. The exposure of a large number of the revolutionary leaders to writings that consisted of works by prominent writers ( John Locke, Baron de Montesquieu) was an eye-opener to the Americans. The writings equipped the founders with concepts relating to limited government, separation of powers, the acceptance of the people governed not forgetting the social contract as well (Bancroft, 2007 pp 162-168).

Some of the main events that resulted in the revolution include the following:

1763 proclamation, which barred settlement past the Appalachian Mountains; the sugar act of 1764 which raised revenue via increased duties on sugar imported from West Indies; Quartering Act of 1765 where Britain did order that the colonists, where necessary were supposed to house as well feed the British soldiers; and the Stamp Act of 1765 which affected many items including licenses for marriage, but was repealed nine years later (Bancroft, 2007 pp 172-175). Further, the revolution at this point was due to increased hard life impositions from the British side (Bancroft, 2007 pp 1176).

There was the great awakening which was a period of heightened religious activity in all the colonies in America. The enthusiasm that resulted was characterized by disagreements among the competing divisions of churches as well as opposing the existing churches. These religious movements reignited the older customs relating to protestant dissent and resulted in the popular, as well as individualistic means of religiosity which disagreed with the alleges of the instated authorities, and respected chains of command- first within the churches and, after some time, around the 1760s to 1770s, in regal politics. It is argued that the first awaking that involved religious upheavals acted to set the stage for creating colonies that gave a hand to a political revolution. It is thus evident that American Revolution resulted from putting together the customs of republicanism and those relating to the radical protestant dissent (Wood, 2002, pp 178-190).

Works Cited

Bancroft, George. History of the United States-From the Discovery of the American Continent , Volume 4. New York: Read Books Publishers, 2007. Print.

Wood, Gordon S. The American Revolution: Volume 9 of Modern Library Chronicles. New York: Modern Library Publishers, 2002. Print.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2021, December 28). Causes of the American Revolution. https://ivypanda.com/essays/causes-of-the-american-revolution/

"Causes of the American Revolution." IvyPanda , 28 Dec. 2021, ivypanda.com/essays/causes-of-the-american-revolution/.

IvyPanda . (2021) 'Causes of the American Revolution'. 28 December.

IvyPanda . 2021. "Causes of the American Revolution." December 28, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/causes-of-the-american-revolution/.

1. IvyPanda . "Causes of the American Revolution." December 28, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/causes-of-the-american-revolution/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Causes of the American Revolution." December 28, 2021. https://ivypanda.com/essays/causes-of-the-american-revolution/.

- American Revolution and Its Historical Stages

- American Colonial Rebellion: American History

- Colonial Resistance to European Domination: 1765-1775

- Using Sidewalks for Dissent

- Road to Revolution

- American Revolution: Seven Years War in 1763

- Networked Dissent: Threats of Social Media’s Manipulation

- The History of the Stamp Act

- “Critic’s Notebook: Debate? Dissent? Discussion? Oh, Don’t go There” by Michiko Kakutani

- History: From Colonies to States

- If Spain Colonized North America?

- The Rise of an ‘American’ Identity

- Abigail Adams' Views on Republican Motherhood

- The American Road to Independence

- American Revolution Rise: Utopian Views

HoW to Write an Essay on the REvolutionary War

And where to get help.

Revolutionary War

A colorful, story-telling overview of the American Revolutionary War

Causes of the American Revolution

It’s impossible to know all the causes of the American Revolution. This page will cover what we do know.

In the beginning, the colonies were proud to be British. There were small instances of Parliament’s control that bothered the colonists, like the Currency Acts of 1751 and 1764 . But when the French and Indian War took place (1754 – 1763), King George III lost a great deal of money due to buying expensive supplies for his army and the colonies. In order to pay off his debt, he imposed taxes on the colonies without their consent.

This outraged the colonists.

It’s an old saying that you should always look for the money trail. The Protestant Reformation had one, and money was certainly one of the major causes of the American Revolution.

The colonists did not like being taxed for things that had always had free. They immediately began a boycott of British goods.

Now it was the king’s turn to be furious.

King George wasted no time in sending soldiers across the Atlantic to make sure the colonies were behaving as they should.

Soon, what is perhaps the most famous of the causes of the American Revolution came to pass. A young ship owner brought over a ship full of taxed tea from Britain and declared he would see it unloaded …

Causes of the American Revolution : The Boston Tea Party

The colonists decided they would see none of the tea leave the ship. A group of colonists dressed as American Indians boarded the ship at night and threw the tea overboard into the harbor, ruining all of it. When they saw one of their comrades trying to stuff some in his pockets, they stripped the tea from his grasp and sent him home without his pants. They then stripped the ship owner of his clothes and tarred and feathered him.

This event is now known as the Boston tea party .

I can’t resist reminding you of Mr. Banks’ comment in the movie Mary Poppins that when the tea was thrown into the harbor, it became “too weak for even Americans to drink.”

Causes of the American Revolution : The Intolerable Acts

In response to the Boston Tea Party, the king imposed the “Intolerable Acts.”

One of the more major causes of the American Revolution, the Intolerable Acts were …

- The Boston Port Act, closing the port of Boston until the Dutch East India Company had been repaid for the destroyed tea;

- The Massachusetts Government Act, putting the government of Massachussets almost entirely under direct British control;

- The Administration of Justice Act, allowing royal officials to be tried in Britain if the king felt it necessary for fair justice;

- The Quartering Act, ordering the colonies to provide lodging for British soldiers

- The Quebec Act, expanding British territory in Canada and guaranteeing the free practice of Roman Catholicism .

The Quartering Act incensed the colonies most. The king and parliament revived an old law requiring colonists to house British soldiers in their homes. Because of the Boston Massacre (4 years earlier, in 1770), the colonists were afraid of the soldiers in their homes. They would lay awake at night with fear for their children embedded in their hearts like a knife.

This is when the colonies decided that something must be done.

Causes of the American Revolution : The First Continental Congress

Out of the Intolerable Acts the First Continental Congress was born.

In this congress 55 delegates representing 12 of the 13 colonies—Georgia withheld—argued back and forth as to whether or not they should separate from Britain for killing their people, firing cannons on their cities, closing down Boston’s sea port, and, primarily, imposing the intolerable acts.

The congress was in session for two solid months in September and October of 1774. After much dissension, they decided to send a “Declaration of Rights and Grievances” to King George, hoping their demands would be met. At this point, the colonists still could not foresee separating from Britain.

More ominously, they also endorsed the “Suffolk Reserves,” resolutions passed by Suffolk county in Massachusetts—certainly one of the causes of the American Revolution.

Massachusetts was the colony worst hit by the Intolerable Acts. The Suffolk Reserves warned General Thomas Gage that Massachussets would not tolerate their enforcement and that they would retain possession of all taxes collected in Massachusetts.

After sending the Declaration of Rights and Grievances, the First Continental Congress separated to await Britain’s reply.

Causes of the American Revolution : The Battles of Lexington and Concord

Tension was far too high for the king to respond favorably. The colonists began to amass arms and prepare for what they felt was an inevitable battle with the oppressive British army.

It came soon enough. Paul Revere’s ride on April 19, 1775 was to announce the approach of British soldiers to stamp out colonist resistance in the towns of Lexington and Concord.

Lexington was first. The British met only 77 minutemen, and at first were pleased to allow them to leave. However, from some unknown place a shot was fired, and the British opened up on the Americans. Eight were killed, ten wounded, and the British suffered but one minor casualty.

It was made up for at Concord . There the colonists were prepared.

400 minutemen sent the British troops scurrying back to Lexington, completely unprepared to be fired on from the woods during their retreat. Apparently, guerilla tactics were considered ungentleman-like in that day and age.

Ungentlemanly or not, they were effective, and the Americans routed the British all the way back to Boston. There were nearly 300 British casualties, including 73 dead and 23 missing. The Americans suffered less than 100.

Causes of the American Revolution : The Second Continental Congress

It was time to do something. The Continental Congress gathered again in May of 1775, where they would become and remain the government of the colonies until the end of the Revolutionary War.

They quickly made an attempt at peace, sending the Olive Branch Petition to King George declaring their loyalty. When it reached the King he pushed it aside and didn’t even read it, and in response he sent a proclamation to the Congress saying that they would all hang for their defiance to the crown.

The Olive Branch Petition

I thought you might be interested in the proposition the 2nd Continental Congress made to King George III:

“Attached to your Majesty’s person, family, and Government, with all devotion that principle and affection can inspire; connected with Great Britain by the strongest ties that can unite societies, and deploring every event that tends in any degree to weaken them, we solemnly assure your Majesty, that we not only most ardently desire the former harmony between her and these Colonies may be restored, but that a concord may be established between them upon so firm a basis as to perpetuate its blessings, uninterrupted by any future dissensions, to succeeding generations in both countries, and to transmit your Majesty’s name to posterity.”

( from u-s-history.com )

This united the colonies and birthed the Declaration of Independence , which bore us to war with Britain.

And there you have the causes of the American Revolution.

Causes of the Revolutionary War Module

A curriculum module for use in middle and high school classrooms..

This set of three lesson plans will guide your students through the Conflict in the Colonies (1754-1763), taxation and colonial disputes (1763-1770), and key events during the final five years (1770-1775) leading to the American Revolution.

Conflict in the Colonies Lesson Plan

Colonial Taxes & Disputes Lesson Plan

Solutions or Revolt? Lesson Plan

This Module contains the following:

3 Lesson Plans

Audience: Middle school | High school

This Module is a part of:

- New Visions Social Studies Curriculum

- Curriculum Development Team

- Content Contributors

- Getting Started: Baseline Assessments

- Getting Started: Resources to Enhance Instruction

- Getting Started: Instructional Routines

- Unit 9.1: Global 1 Introduction

- Unit 9.2: The First Civilizations

- Unit 9.3: Classical Civilizations

- Unit 9.4: Political Powers and Achievements

- Unit 9.5: Social and Cultural Growth and Conflict

- Unit 9.6: Ottoman and Ming Pre-1600

- Unit 9.7: Transformation of Western Europe and Russia

- Unit 9.8: Africa and the Americas Pre-1600

- Unit 9.9: Interactions and Disruptions

- Unit 10.0: Global 2 Introduction

- Unit 10.1: The World in 1750 C.E.

- Unit 10.2: Enlightenment, Revolution, and Nationalism

- Unit 10.3: Industrial Revolution

- Unit 10.4: Imperialism

- Unit 10.5: World Wars

- Unit 10.6: Cold War Era

- Unit 10.7: Decolonization and Nationalism

- Unit 10.8: Cultural Traditions and Modernization

- Unit 10.9: Globalization and the Changing Environment

- Unit 10.10: Human Rights Violations

- Unit 11.0: US History Introduction

- Unit 11.1: Colonial Foundations

Unit 11.2: American Revolution

- Unit 11.3A: Building a Nation

- Unit 11.03B: Sectionalism & the Civil War

- Unit 11.4: Reconstruction

- Unit 11.5: Gilded Age and Progressive Era

- Unit 11.6: Rise of American Power

- Unit 11.7: Prosperity and Depression

- Unit 11.8: World War II

- Unit 11.9: Cold War

- Unit 11.10: Domestic Change

- Resources: Regents Prep: Global 2 Exam

- Regents Prep: Framework USH Exam: Regents Prep: US Exam

- Find Resources

American Revolution

Dbq: causes of the american revolution, using evidence: nys regents style dbq.

U.S. History

American Revolution: DBQ: Causes of the American Revolution

Students will examine and evaluate primary and secondary source documents to construct an essay that analyzes the causes of the American Revolution.

Teacher Feedback

Please comment below with questions, feedback, suggestions, or descriptions of your experience using this resource with students.

If you found an error in the resource, please let us know so we can correct it by filling out this form .

Home — Essay Samples — History — History of the United States — American Revolutionary War

Essays on American Revolutionary War

Valley forge: a test of resilience, revolutionary war geographic advantages, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Chains Chapter Summary

The major contributions of crispus attucks and peter salem to the liberation and sovereignty of america during the american revolutionary war, american revolutionary war and the changes it caused on political, social and cultural levels, the american revolutionary war: the battles of lexington and concord, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

The Tremendous Battle at Germantown

The effects of the american revolution, smallpox role in the revolutionary war, the goals of the colonists in the revolutionary war, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Second American Revolution: Its Impact and Legacy

The problems the united states had with paying debts after the revolutionary war, the boston siege: american revolution war, the context of the american revolutionary war from a historical perspective, the features that contribute to the unique character of the american revolutionary war, the difference between american and french revolutions, the battle of saratoga, insurgency and asymmetric warfare in the american revolutionary war , joseph plumb martin and his role in the revolutionary war, war on the colonies: french, indian war and american revolution, what influenced the patriots' win in the revolutionary war, causes of the american revolution: political, economic and ideolodical, an analytical dive into the battle of yorktown, women's participation in the american revolutionary war, rhetorical devices in patrick henry's speech, the pros and cons of the articles of confederation.

April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783

Eastern North America, North Atlantic Ocean, the West Indies

Battle of Brandywine, Battle of Bunker Hill, Battle of Monmouth, Battles of Saratoga, Battle of Bemis Heights

United States War of Independence, Revolutionary War

Before the flare-up of the American Revolutionary War, there had been growing tensions and conflicts between the British crown and its thirteen colonies. Attempts by the British government to raise revenue by taxing the colonies met with heated protest among many colonists. The Stamp Act and Townshend Acts provoked colonial opposition and unrest, leading to the 1770 Boston Massacre and 1773 Boston Tea Party.

By June 1776, a growing majority of the colonists had come to favor independence from Britain. On July 4, the Continental Congress voted to adopt the Declaration of Independence drafted largely by Thomas Jefferson.

In March 1776, the British led by General William Howe retreated to Canada to prepare for a major invasion of New York. A large British fleet was sent to New York with the aim to crush the rebellion. Routed by Howe’s Redcoats on Long Island, Washington’s troops were forced to evacuate from New York City. However, the surprise attack in Trenton and the battle near Princeton, New Jersey after that, marked another small victory for the colonials and revived the flagging hopes of the rebels.

British strategy in 1777 involved two main prongs of attack aimed at separating New England from the other colonies. Following the American victory in Battle of Saratoga, France and America signed treaties of alliance on February 6, 1778, in which France provided America with troops and warships.

On September 3, 1783, the Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by Great Britain and by the United States of America, officially ended the American Revolutionary War.

Britain recognized the United States of America as an independent country. The Constitution was written in 1787 to amend the weak Articles of Confederation and it organized the basic political institutions and formed the three branches of government: judicial, executive, and legislative.

Relevant topics

- Civil Rights Movement

- Industrial Revolution

- Boston Massacre

- Florence Kelley

- Atlantic Slave Trade

- Benjamin Franklin

- African American History

- American Flag

- Californian Gold Rush

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Lesson Plans

- Teacher's Guides

- Media Resources

Voices of the American Revolution

"Molly Pitcher" at the Battle of Monmouth.

Wikimedia Commons

In the years preceding the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, many American colonists expressed opposition to Great Britain's policies toward the colonies, but few thought seriously about establishing an independent nation until late in the imperial crisis. Throughout the years of controversy beginning in the 1760s, Americans expressed a variety of opinions about the legitimacy of open acts of resistance and rebellion, which intensified as armed resistance began in April 1775. On both sides of the issue, perspectives and motivations were diverse. Among those who favored resistance, for example, not all would go so far as to advocate full-scale rebellion against Great Britain or national independence for the United States. The debate, moreover, was not a static one, and its terms shifted over time; by 1776 many colonists found themselves advocating positions undreamed of a decade earlier.

In this lesson, students are taught how to make informed analyses of primary documents illustrating the diversity of religious, political, social, and economic motives behind competing perspectives on questions of independence and rebellion. Making use of a variety of primary texts, the activities below help students to "hear" some of the colonial voices that, in the course of time and under the pressure of novel ideas and events, contributed to the American Revolution.

Guiding Questions

Why were colonists willing to go to war?

Who was "Molly Pitcher"?

What did individuals and groups gain and lose by joining the American Revolution?

Learning Objectives

Examine varying reasons for why individuals chose to rebel or remain loyal.

Analyze documents to determine point of view analysis and use evidence for or against rebellion to inform your position on the compelling questions.

Evaluate the decision by a person or group to take a particular side during the American Revolution.

Lesson Plan Details

NCSS.D1.2.9-12. Explain points of agreement and disagreement experts have about interpretations and applications of disciplinary concepts and ideas associated with a compelling question.

NCSS.D2.His.1.9-12. Evaluate how historical events and developments were shaped by unique circumstances of time and place as well as broader historical contexts.

NCSS.D2.His.2.9-12. Analyze change and continuity in historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.3.9-12. Use questions generated about individuals and groups to assess how the significance of their actions changes over time and is shaped by the historical context.

NCSS.D2.His.4.9-12. Analyze complex and interacting factors that influenced the perspectives of people during different historical eras.

NCSS.D2.His.5.9-12. Analyze how historical contexts shaped and continue to shape people’s perspectives.

NCSS.D2.His.12.9-12. Use questions generated about multiple historical sources to pursue further inquiry and investigate additional sources.

NCSS.D2.His.14.9-12. Analyze multiple and complex causes and effects of events in the past.

NCSS.D2.His.15.9-12. Distinguish between long-term causes and triggering events in developing a historical argument.

NCSS.D2.His.16.9-12. Integrate evidence from multiple relevant historical sources and interpretations into a reasoned argument about the past.

Materials. Download and copy any handouts you plan to use in this lesson. For activity 1 below, you will need the PDF Voices of the Revolution: Document Analysis . If you plan to use Option #1—Point – Counterpoint Debate, below, provide students with a copy of the Point – Counterpoint Rubric , available here as a downloadable PDF. If you choose Option #2—Group Research and Class Discussion, provide your students with a copy of the Essay Rubric , also available as a downloadable PDF.

Background. Before beginning the activities described in this lesson, you should provide your students with a general background on the differences that existed among the American colonists prior to the outbreak of war. Guided Readings on the American Revolution, including causes and motivations, are available from The Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History , a link on the EDSITEment-reviewed History Matters .

While you may wish to present the spectrum of colonial opinion in terms of arguments for and against rebelling, help your students to understand that the debate shifted over time, and that acts of resistance do not necessarily amount to calls for rebellion. A good way to introduce such nuances is within a chronological framework. You can find an excellent annotated timeline of events during the Revolutionary War era from the EDSITEment-reviewed American Memory collection.

Another approach to providing an overview of the events and opinions leading up to the Revolutionary war is to present students with the evolving views of a single influential individual over time. For a central example, see the individual letters written by George Washington, available from the EDSITEment-reviewed The Papers of George Washington .

Primary Documents. Introduce your students to a representative cross-section of the documents to be examined in this lesson. One approach might be to identify documents from each of the broad categories below:

A. Religious motivations

Read the essay by Christine Leigh Heyrman, " Religion and the American Revolution ," available from the EDSITEment reviewed TeacherServe . Linked to this website is an exhibit produced by the Library of Congress entitled Religion and the American Revolution , which contains links to several documents showing religious motivations both loyalist and rebel. Of special relevance to this lesson is the webpage Religion and the Founding of the American Republic . Below are just a few of a number of relevant documents and artifacts to be found on this webpage:

- Jonathan Mayhew's " A Discourse Concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to Higher Powers ." which argues from Scripture that God does not forbid resistance to rulers who do not govern wisely.)

- Once a speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly and friend to Benjamin Franklin, Joseph Galloway was a loyalist who fled to England in 1778. In this excerpt from his book, Historical and Political Reflections on the Rise and Progress of the American Rebellion , he asserts that the cause of the rebellion was essentially religious, a result of the animosity of Congregational and Presbyterian interests in America towards the Anglican Church (for more, see Religion and the Founding of the American Republic ).

- An allegory done in needlework , " The Hanging of Absalom ," illustrates the tendency of American colonists to view the conflict with Britain in biblical terms. The following interpretation of this allegory is provided: "The creator of the work saw Absalom as a patriot, rebelling against and suffering from the arbitrary rule of his father King David (symbolizing George III) …" (for more, see Religion and the Founding of the American Republic ).

- Other possibilities from Religion and the Founding of the American Republic include a sermon arguing that rebellion is justified by God, a revolutionary battle flag containing religious symbolism, arguments among Quakers about whether to join the battle, and documents that illustrate divided loyalties within the Anglican Church in America.

B. Loyalist perspectives

Plain Truth , a response written by loyalist James Chalmers to Thomas Paine's Common Sense (the text of Chalmer's response comes from Archiving Early America , a link on the EDSITEment-reviewed Internet Public Library).

Charles Inglis, an Anglican clergyman and loyalist, responded to Thomas Paine with an anonymous pamphlet, " The True Interest of America Impartially Stated ," which argues for a reconciliation between Britain and the American Colonies.

C. Rebel perspectives

Available from the Avalon Project at the Yale Law School , the famous speech by Patrick Henry in which he proclaimed, " Give me Liberty or Give Me Death ." Another example, from The Papers of George Washington , is George Washington's letter of May 31, 1775 to a close friend in which he suggests his resolve to rebel: " But can a virtuous man hesitate in his choice? "

The above video helps students answer the question Who was Molly Pitcher? and understand the role of women during the American Revolution.

D. African American voices

A number of documents related to the position and perspective of African Americans during the Revolution are available from the EDSITEment resource, Africans in America . The following are just a few of the possibilities available on this website:

- African American petition in 1773 to Governor Hutchinson, written by Felix on behalf of "many Slaves, living in the Town of Boston, and other Towns in the Province."

- " Free Black Patriots ," an essay on free black men from the North who fought on the American side.

- " Runaways ," an essay about black slaves who fought on either the British or American side during the Revolution in order to escape slavery.

- In " Of the Natural Rights of Colonists ," Bostonian James Otis wrote that "the colonists are by the law of nature freeborn, as indeed all men are, white or black," making him one of only a few American writers of the time who combined an argument for succession with an argument against slavery.

E. Official and legal documents

- From the Avalon Project at the Yale Law School , two documents written on the eve of the Declaration of Independence: George Mason's Virginia Declaration of Rights (June 12, 1776), and Richard Henry Lee's Resolution , which proposed to the Continental Congress a declaration of independence (June 7, 1776).

- Also, available is Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of taking up Arms (July 6, 1775).

- The text of the Declaration of Independence , as well as a wealth of supporting resources, from the Educator Resources (National Archives and Records Administration).

Activity 1. Tools for Analyzing Primary Documents

The above video from PBS offers a short introduction on the various perspectives and backgrounds of people who would have been faced with the compelling question "Would you have joined the American Revolution?" This can help students see the competing perspectives across and within sides prior to examining primary sources and the motives of specific groups.

Prior to assigning option #1 or option #2, below, provide your students with a general introduction to interpreting primary documents. Here are some possibilities for questions that students can ask themselves of each document (the questions below are also available as a downloadable PDF, Voices of the Revolution: Document Analysis ):

- What is the general motivation of the writer of this document (i.e., religious, philosophical)?

- Were there any antecedent events directly preceding the authoring of the document that may have influenced it (i.e., the Stamp Act, Boston Massacre)?

- Are there any significant attitudes about rights of various groups expressed? Explain.

- Was this a document originally intended for a small audience or large audience? Would the type of original audience affect how the document was authored?

- Is there a specific call to action in the document? If so, what?

- Is there a claim of authority or credibility made by the author of the document (i.e., moral, common sense)?

In addition to these questions, you can also download a Written Document Analysis Worksheet from the Educator Resources , a resource from the National Archives and Records Administration.

To model the process of analyzing primary documents, you may wish to provide the class with copies of the letter of George Washington to George Mason in 1769 . Although a little long, it provides a strong document of which to ask all of the preceding questions. Its readability is also aided by annotation provided following the document. The letter provides natural interest since it was written by the future commander of the armed forces and first president of the United States.

Activity 2. Voices of the Revolution: Individual or Group Options for Independent Study

Option #1—Point–Counterpoint Debate : Assign students to individual historical persons or viewpoints based upon particular primary documents. After students have had time to examine their assigned documents and to fill out a Document Analysis Worksheet , they are ready to prepare for an in-class debate. Use the Rubric for Point–Counterpoint Debate , available here as a downloadable PDF document, to present students with instructions for preparing for the classroom debate. Direct students to the Internet resources described in Preparing to Teach to research the additional information they will need to clarify their position in the debate. As outlined in the Rubric , students then do a "point counterpoint" debate during class time.