Real Life Bipolar Disorder: A Case Study of Susan

Bipolar disorder is a complex and often misunderstood mental health condition that affects millions of individuals worldwide. For those living with bipolar disorder, the highs and lows of life can be dizzying, as they navigate through periods of intense mania and debilitating depression. To truly grasp the impact of this disorder, it’s crucial to explore real-life experiences and the stories of those who have dealt firsthand with its challenges.

In this article, we delve into the fascinating case study of Susan, a woman whose life has been profoundly shaped by her bipolar disorder diagnosis. By examining Susan’s journey, we aim to shed light on the realities of living with this condition and the strategies employed to manage and treat it effectively.

But before we plunge deeper into Susan’s story, let’s first gain a comprehensive understanding of bipolar disorder itself. We’ll explore the formal definition, the prevalence of the condition, and its impact on both individuals and society as a whole. This groundwork will set the stage for a more insightful exploration of Susan’s experience and provide valuable context for the subsequent sections of this article.

Bipolar disorder is more than just mood swings; it is a condition that can significantly disrupt an individual’s life, relationships, and overall well-being. By studying a real-life case like Susan’s, we can gain a personal insight into the multifaceted challenges faced by those with bipolar disorder and the importance of effective treatment and support systems. In doing so, we hope to foster empathy, inspire early diagnosis, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge about bipolar disorder’s complexities.

The Case of Susan: A Real Life Experience with Bipolar Disorder

Susan’s story provides a compelling illustration of the impact that bipolar disorder can have on an individual’s life. Understanding her background, symptoms, and the effects of the disorder on her daily life can provide valuable insights into the challenges faced by those with bipolar disorder.

Background Information on Susan

Susan, a thirty-eight-year-old woman, was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at the age of twenty-five. Her early experiences with the disorder were characterized by periods of extreme highs and lows, often resulting in strained relationships and an inability to maintain steady employment. Susan’s episodes of mania frequently led to impulsive decision-making, excessive spending sprees, and risky behaviors. On the other hand, her depressive episodes left her feeling hopeless, fatigued, and unmotivated.

Symptoms and Diagnosis of Bipolar Disorder in Susan

To receive an accurate diagnosis, Susan underwent a thorough examination by mental health professionals. The criteria for diagnosing bipolar disorder include significant and persistent mood swings, alternating between periods of mania and depression. Susan exhibited classic symptoms of bipolar disorder, such as elevated mood, increased energy, racing thoughts, decreased need for sleep, and reckless behavior during her manic episodes. These episodes were interspersed with periods of deep sadness, loss of interest in activities, and changes in appetite and sleep patterns during depressive phases.

Effects of Bipolar Disorder on Susan’s Daily Life

Living with bipolar disorder presents unique challenges for Susan. The unpredictable shifts in her mood and energy levels significantly impact her ability to function in both personal and professional spheres. During manic phases, Susan experiences heightened productivity, creativity, and confidence, often leading her to take on excessive responsibilities and projects. However, these periods are eventually followed by crashes into depressive episodes, leaving her unable to complete tasks, maintain relationships, or even perform routine self-care. The constant fluctuations in her emotional state make it difficult for Susan to establish a sense of stability and predictability in her life.

Susan’s struggle with bipolar disorder is not uncommon. Many individuals with this condition face similar obstacles in their daily lives, attempting to manage the debilitating highs and lows while striving for a sense of normalcy. By understanding the real-life implications of bipolar disorder, we can more effectively tailor our support systems and treatment options to address the needs of individuals like Susan. In the next section, we will explore the various approaches to treating and managing bipolar disorder, providing potential strategies for improving the quality of life for those living with this condition.

Treatment and Management of Bipolar Disorder in Susan

Managing bipolar disorder requires a multifaceted approach that combines psychopharmacological interventions, psychotherapy, counseling, and lifestyle modifications. Susan’s journey towards finding effective treatment and management strategies highlights the importance of a comprehensive and tailored approach.

Psychopharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological interventions play a crucial role in stabilizing mood and managing symptoms associated with bipolar disorder. Susan’s treatment plan involved medications such as mood stabilizers, antipsychotics, and antidepressants. These medications aim to regulate the neurotransmitters in the brain associated with mood regulation. Susan and her healthcare provider closely monitored her medication regimen and made adjustments as needed to achieve symptom control.

Psychotherapy and Counseling

Psychotherapy and counseling provide individuals with bipolar disorder a safe space to explore their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. Susan engaged in cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which helped her identify and challenge negative thought patterns and develop healthy coping mechanisms. Additionally, psychoeducation in the form of group therapy or support groups allowed Susan to connect with others facing similar challenges, fostering a sense of community and reducing feelings of isolation.

Lifestyle Modifications and Self-Care Strategies

In addition to medical interventions and therapy, lifestyle modifications and self-care strategies play a vital role in managing bipolar disorder. Susan found that maintaining a stable routine, including regular sleep patterns, exercise, and a balanced diet, helped regulate her mood. Avoiding excessive stressors and implementing stress management techniques, such as mindfulness meditation or relaxation exercises, also supported her overall well-being. Engaging in activities she enjoyed, nurturing her social connections, and setting realistic goals further enhanced her quality of life.

Striving for stability and managing bipolar disorder is an ongoing process. What works for one individual may not be effective for another. It is crucial for individuals with bipolar disorder to work closely with their healthcare providers and engage in open communication about treatment options and progress. Fine-tuning the combination of psychopharmacological interventions, therapy, and self-care strategies is essential to optimize symptom control and maintain stability.

Understanding the complexity of treatment and management helps foster empathy for individuals like Susan, who face the daily challenges associated with bipolar disorder. It underscores the importance of early diagnosis, accessible mental health care, and ongoing support systems to enhance the lives of individuals living with this condition. In the following section, we will explore the various support systems available to individuals with bipolar disorder, including family support, peer support groups, and the professional resources that contribute to their well-being.

Support Systems for Individuals with Bipolar Disorder

Navigating the challenges of bipolar disorder requires a strong support system that encompasses various sources of assistance. From family support to peer support groups and professional resources, these networks play a significant role in helping individuals manage their condition effectively.

Family Support

Family support is vital for individuals with bipolar disorder. Understanding and empathetic family members can provide emotional support, monitor medication adherence, and help identify potential triggers or warning signs of relapse. In Susan’s case, her family played a crucial role in her recovery journey, providing a stable and nurturing environment. Education about bipolar disorder within the family helps foster empathy, reduces stigma, and promotes open communication.

Peer Support Groups

Peer support groups provide individuals with bipolar disorder an opportunity to connect with others who share similar experiences. Sharing personal stories, strategies for coping, and offering mutual support can be empowering and validating. In these groups, individuals like Susan can find solace in knowing that they are not alone in their struggles. Peer support groups may meet in-person or virtually, allowing for easier access to support regardless of physical proximity.

Professional Support and Resources

Professional support is crucial in the management of bipolar disorder. Mental health professionals, such as psychiatrists, psychologists, and therapists, provide expertise and guidance in developing comprehensive treatment plans. Regular therapy sessions allow individuals like Susan to explore emotional challenges and develop healthy coping mechanisms. Psychiatrists closely monitor medication effectiveness and make necessary adjustments. Additionally, case managers or social workers can assist with navigating the healthcare system, accessing resources, and connect individuals with other community services.

Beyond direct professional support, there are resources and organizations dedicated to bipolar disorder education, advocacy, and support. Online forums, websites, and helplines provide information, guidance, and a sense of community. These platforms allow individuals to access information at any time and connect with others who understand their unique experiences.

Support systems for bipolar disorder are crucial in empowering individuals and enabling them to lead fulfilling lives. They contribute to reducing stigma, providing emotional support, and ensuring access to resources and education. Through these support systems, individuals with bipolar disorder can gain self-confidence, develop effective coping strategies, and improve their overall well-being.

In the next section, we explore the significance of case studies in understanding bipolar disorder and how they contribute to advancing research and knowledge in the field. Specifically, we will examine how Susan’s case study serves as a valuable contribution to furthering our understanding of this complex disorder.

The Importance of Case Studies in Understanding Bipolar Disorder

Case studies play a vital role in advancing our understanding of bipolar disorder and its complexities. They offer valuable insights into individual experiences, treatment outcomes, and the overall impact of the condition on individuals and society. Susan’s case study, in particular, provides a unique perspective that contributes to broader research and knowledge in the field.

How Case Studies Contribute to Research

Case studies provide an in-depth examination of specific individuals and their experiences with bipolar disorder. They allow researchers and healthcare professionals to observe patterns, identify commonalities, and gain valuable insights into the factors that influence symptom presentation, treatment response, and prognosis. By analyzing various case studies, researchers can generate hypotheses and refine treatment approaches to optimize outcomes for individuals with bipolar disorder.

Case studies are particularly helpful in documenting rare or atypical presentations of bipolar disorder. They shed light on lesser-known subtypes, such as rapid-cycling bipolar disorder or mixed episodes, contributing to a more comprehensive understanding of the condition. Case studies also provide opportunities for clinicians and researchers to discuss unique challenges and discover innovative interventions to improve treatment outcomes.

Susan’s Case Study in the Context of ATI Bipolar Disorder

Susan’s case study is an example of how individual experiences can inform the development of Assessment Technologies Institute (ATI) for bipolar disorder. By examining her journey, researchers can analyze treatment approaches, evaluate the effectiveness of various interventions, and develop evidence-based guidelines for managing bipolar disorder.

Susan’s case study provides rich information about the impact of medication, psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications on symptom control and overall well-being. It offers valuable insights into the benefits and limitations of specific interventions, highlighting the importance of personalized treatment plans tailored to individual needs. Additionally, Susan’s case study can contribute to ongoing discussions about the role of support systems and the integration of peer support groups in managing and enhancing the lives of individuals with bipolar disorder.

The detailed documentation of Susan’s experiences serves as a powerful tool for healthcare providers, researchers, and individuals living with bipolar disorder. It highlights the complexities and challenges associated with the condition while fostering empathy and understanding among various stakeholders.

Case studies, such as Susan’s, play a crucial role in enhancing our understanding of bipolar disorder. They provide insights into individual experiences, treatment approaches, and the impact of the condition on individuals and society. Through these case studies, we can cultivate empathy for individuals with bipolar disorder, advocate for early diagnosis and effective treatment, and contribute to advancements in research and knowledge.

By illuminating the realities of living with bipolar disorder, we acknowledge the need for accessible mental health care, support systems, and evidence-based interventions. Susan’s case study exemplifies the importance of a comprehensive approach to managing bipolar disorder, integrating psychopharmacological interventions, psychotherapy, counseling, and lifestyle modifications.

Moving forward, it is essential to continue studying cases like Susan’s and explore the diverse experiences within the bipolar disorder population. By doing so, we can foster empathy, encourage early intervention and personalized treatment, and contribute to advancements in understanding bipolar disorder, ultimately improving the lives of individuals affected by this complex condition.

Empathy and Understanding for Individuals with Bipolar Disorder

Developing empathy and understanding for individuals with bipolar disorder is crucial in fostering a supportive and inclusive society. By recognizing the unique challenges they face and the complexity of their experiences, we can better advocate for their needs and provide the necessary resources and support.

It is important to understand that bipolar disorder is not simply a matter of mood swings or being “moody.” It is a chronic and often debilitating mental health condition that affects individuals in profound ways. The extreme highs of mania and the lows of depression can disrupt relationships, employment, and overall quality of life. Developing empathy means acknowledging that these struggles are real and offering support and understanding to those navigating them.

Encouraging Early Diagnosis and Effective Treatment

Early diagnosis and effective treatment are key factors in managing bipolar disorder and reducing the impact of its symptoms. Encouraging individuals to seek help and reducing the stigma associated with mental illness are crucial steps toward achieving early diagnosis. Increased awareness campaigns and education can empower individuals to recognize the signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder in themselves or their loved ones, facilitating timely intervention.

Once diagnosed, providing access to quality mental health care and ensuring individuals receive appropriate treatment is essential. Bipolar disorder often requires a combination of pharmacological interventions, psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications. By advocating for comprehensive treatment plans and promoting ongoing care, we can help individuals with bipolar disorder achieve symptom control and improve their overall well-being.

The Role of Case Studies in Advancing Knowledge about Bipolar Disorder

Case studies, like Susan’s, play a significant role in advancing knowledge about bipolar disorder. They provide unique insights into individual experiences, treatment outcomes, and the wider impact of the condition. Researchers and healthcare providers can learn from these individual cases, developing evidence-based guidelines and refining treatment approaches.

Additionally, case studies contribute to reducing stigma by providing personal narratives that humanize the disorder. They showcase the challenges faced by individuals with bipolar disorder and highlight the importance of support systems, empathy, and understanding. By sharing these stories, we can help dispel misconceptions and promote a more compassionate approach toward mental health as a whole.

In conclusion, developing empathy and understanding for individuals with bipolar disorder is essential. By recognizing the complexity of their experiences, advocating for early diagnosis and effective treatment, and valuing the insights provided by case studies, we can create a society that supports and uplifts those with bipolar disorder. It is through empathy and education that we can reduce stigma, promote accessible mental health care, and improve the lives of those affected by this condition.In conclusion, gaining a comprehensive understanding of bipolar disorder is crucial in order to support individuals affected by this complex mental health condition. Through the real-life case study of Susan, we have explored the numerous facets of bipolar disorder, including its background, symptoms, and effects on daily life. Susan’s journey serves as a powerful reminder of the challenges individuals face in managing the highs and lows of bipolar disorder and emphasizes the importance of effective treatment and support systems.

We have examined the various approaches to treating and managing bipolar disorder, including psychopharmacological interventions, psychotherapy, and lifestyle modifications. Understanding the role of these treatments and the need for personalized care can significantly improve the quality of life for individuals like Susan.

Support systems also play a crucial role in helping those with bipolar disorder navigate the complexities of the condition. From family support to peer support groups and access to professional resources, fostering a strong network of assistance can provide the necessary emotional support, education, and guidance needed for individuals to effectively manage their symptoms.

Furthermore, case studies, such as Susan’s, contribute to advancing our knowledge about bipolar disorder. By delving into individual experiences, researchers gain valuable insights into treatment outcomes, prognosis, and the impact of the condition on individuals and society as a whole. These case studies foster empathy, reduce stigma, and contribute to the development of evidence-based guidelines and interventions that can improve the lives of individuals with bipolar disorder.

In fostering empathy and promoting early diagnosis, effective treatment, and ongoing support, we create a society that actively embraces and supports individuals with bipolar disorder. By encouraging understanding, reducing stigma, and prioritizing mental health care, we can ensure that those affected by bipolar disorder receive the support and resources necessary to lead fulfilling and meaningful lives. Through empathy, education, and continued research, we can work towards a future where individuals with bipolar disorder are understood, valued, and empowered to thrive.

Similar Posts

Income Requirements to Be a Foster Parent: A Comprehensive Guide

Becoming a foster parent is a noble and rewarding endeavor that can profoundly impact the lives of children in need. However, it’s essential to understand the various requirements and responsibilities that come with this role, including financial considerations. This comprehensive guide will explore the income requirements for foster parents, as well as other crucial aspects…

Family Access Berkley: A Guide to Depression Treatment and Support

Darkness can engulf not just individuals but entire families, yet Berkley’s comprehensive guide to depression treatment and support offers a beacon of hope for those seeking to reclaim the light. Depression is a complex mental health condition that affects millions of people worldwide, and its impact extends far beyond the individual experiencing it. In Berkley,…

Understanding Bipolar Codependency: The Relationship Between Codependency and Bipolar Disorder

Imagine being in a relationship where your sense of identity becomes intertwined with someone else’s emotions, needs, and desires. You constantly find yourself putting their well-being above your own, sacrificing your own happiness for theirs. This unhealthy and often destructive pattern is known as codependency. Now, imagine experiencing extreme mood swings that take you on…

The Complex Relationship Between Codependency and Depression: Understanding, Recognizing, and Healing

The intricate relationship between codependency and depression is a complex web that often leaves individuals feeling trapped in a cycle of emotional turmoil. These two conditions, while distinct, frequently intertwine, creating a challenging landscape for those affected and their loved ones. Understanding this connection is crucial for recognizing the signs and taking steps towards healing…

Most Common Reasons for Teenage Breakups: Understanding the Link with Depression

Teenage relationships are a significant part of adolescent development, often marked by intense emotions and experiences. However, these relationships can be fragile, and breakups are a common occurrence during this formative period. The prevalence of teenage breakups is high, with many adolescents experiencing the end of a romantic relationship before they reach adulthood. These breakups…

A Comprehensive Guide for Bipolar Caregivers

Caring for someone with bipolar disorder can be an emotional and challenging journey. As a caregiver, you play a crucial role in supporting your loved one through the ups and downs of this complex mental health condition. But where do you begin? How do you navigate the unfamiliar territory of bipolar caregiving? In this comprehensive…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Patient Case: 30-Year-Old Male With Bipolar Disorder

Nidal Moukaddam, MD, PhD, presents the case of a 30-year-old male diagnosed with bipolar 1 disorder and shares her initial impressions on diagnosis.

EP: 1 . Patient Case: 30-Year-Old Male With Bipolar Disorder

Ep: 2 . approaching the treatment of bipolar disorder, ep: 3 . treatment selection for bipolar disorder, ep: 4 . takeaways for bipolar disorder management.

Nidal Moukaddam, MD, PhD: Today, we’re going to talk about a new case. A 30-year-old man has taken short-term disability leave from work due to the progression of a depressive episode. He received a diagnosis of bipolar I disorder about 10 years ago. He had his first episode of mania at the age of 20 and 2 subsequent episodes of mania between the ages of 21 and 29. He was treated with lithium, which was highly effective, but he experienced excessive thirst and developed hyperthyroidism. His lithium level at the time was in the therapeutic range of 0.8 mEq/L. He was switched to valproate; however, valproate lacked the efficacy of lithium and caused adverse effects of sedation and weight gain. During his third manic episode, he started on olanzapine but experienced excessive weight gain. He was then cross-titrated to quetiapine, which improved his manic symptoms. However, weight gain again became an adverse effect, and he also complained of sedation. The patient reported sleeplessness and made unnecessary online purchases when unable to sleep, but the quetiapine sleepiness was unacceptable. Despite these adverse effects, he continued taking] quetiapine until he decompensated into his third depressive episode. The quetiapine was then augmented with lamotrigine, which was titrated up to 300 mg per day but demonstrated no efficacy. At the time of presentation, the patient was adhering to the medications. He did not have a substance use disorder, which was confirmed by a negative toxicology screen. His TSH [thyroid-stimulating hormone] level was in the middle of the normal range, and he had no suicidal ideations or psychotic symptoms.

I think the most important thing to do when somebody comes to you, even if they tell you they have a diagnosis, is to confirm the diagnosis. You want to start by making up your own mind, and sometimes the patient is not a good source of information. But in the case of bipolar disorder without psychosis, you expect the patient to be able to give you a solid history. Typically, the part of the history that’s hardest to nail down is mania. When people experience mania, they have excessive energy and excessive activation that creates the need for sleep, and sometimes they like it. They feel that this is the way it should be, so they don’t point it out as pathological. Now, the DSM-5 [ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition ] criteria tell us that mania that leads to hospitalization or some negative consequence like incarceration is problematic no matter what the duration is. Assuming the patient did not end up in the hospital or in prison, we want to verify the story of mania. In the current case presentation, I can see many of my colleagues saying, “Hey, you’re not giving us enough symptoms of mania. He’s a bit sleepless. He makes frivolous purchases. That’s bipolar disorder but not bipolar I; maybe it’s bipolar II.”

Thus, my first step would be to explain that this patient had at least a week without sleep. During that week, he was spacing, had pressured speech, and was talking fast to the point that others around him commented about it. He became more impulsive, and buying things was the tip of the iceberg. He also became more sexual to the point where it got him in trouble in his relationships, he spent more money than he had planned, etc. These examples of impulsivity often nail down the diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Of course, these symptoms change with the time that we live in. For example, before unlimited plans on cell phones, you would have been taught to ask: “Do you get a very high bill on your phone when you’re manic?” Because patients with mania talk a lot, and the bills would be higher when they call across state lines or internationally. First, I would recommend verifying the diagnosis. My impression of the patient is that this is somebody with a set diagnosis of bipolar I. Three manic episodes is a lot. He has impairment because of it, and it’s affected his job. Thus, my first step is confirming the diagnosis. My second would be a lot of psychoeducation; make sure that the patient understands what he’s up against and why he needs treatment.

Transcript Edited for Clarity

Evaluating the Efficacy of Lumateperone for MDD and Bipolar Depression With Mixed Features

Blue Light Blockers: A Behavior Therapy for Mania

Efficacy of Modafinil for Treatment of Neurocognitive Impairment in Bipolar Disorder

Blue Light, Depression, and Bipolar Disorder

Securing the Future of Lithium Research

An Update on Early Intervention in Psychotic Disorders

2 Commerce Drive Cranbury, NJ 08512

609-716-7777

- Search Menu

Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Numismatics

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Social History

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Legal System - Costs and Funding

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Restitution

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Social Issues in Business and Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Social Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Sustainability

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Disability Studies

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

5 Psychiatric Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: The Case of Janice

- Published: February 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Chapter 5 covers the psychiatric treatment of bipolar disorder, including a case history, key principles, assessment strategy, differential diagnosis, case formulation, treatment planning, nonspecific factors in treatment, potential treatment obstacles, ethical considerations, common mistakes to avoid in treatment, and relapse prevention.

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

- Add your ORCID iD

Institutional access

Sign in with a library card.

- Sign in with username/password

- Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

| Month: | Total Views: |

|---|---|

| October 2022 | 4 |

| November 2022 | 1 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

| January 2023 | 6 |

| February 2023 | 4 |

| March 2023 | 6 |

| April 2023 | 1 |

| May 2023 | 1 |

| June 2023 | 3 |

| July 2023 | 2 |

| August 2023 | 2 |

| September 2023 | 4 |

| October 2023 | 4 |

| November 2023 | 3 |

| December 2023 | 4 |

| January 2024 | 14 |

| February 2024 | 6 |

| March 2024 | 3 |

| April 2024 | 3 |

| May 2024 | 6 |

| June 2024 | 5 |

| July 2024 | 2 |

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

- Presidential Message

- Nominations/Elections

- Past Presidents

- Member Spotlight

- Fellow List

- Fellowship Nominations

- Current Awardees

- Award Nominations

- SCP Mentoring Program

- SCP Book Club

- Pub Fee & Certificate Purchases

- LEAD Program

- Introduction

- Find a Treatment

- Submit Proposal

- Dissemination and Implementation

- Diversity Resources

- Graduate School Applicants

- Student Resources

- Early Career Resources

- Principles for Training in Evidence-Based Psychology

- Advances in Psychotherapy

- Announcements

- Submit Blog

- Student Blog

- The Clinical Psychologist

- CP:SP Journal

- APA Convention

- SCP Conference

CASE STUDY Richard (bipolar disorder, substance use disorder)

Case study details.

Richard is a 62-year-old single man who says that his substance dependence and his bipolar disorder both emerged in his late teens. He says that he started to drink to “feel better” when his episodes of depression made it hard for him to interact with his peers. He also states that alcohol and cocaine are a natural part of his manic episodes. He also notes that coming off the cocaine and binge drinking contribute to low mood, but he has not responded well to referrals to AA and past inpatient stays have led to only temporary abstinence. Yet, Richard is now trying to forge a closer relationship to his adult children, and he says he is especially motivated to get a better handle on both his bipolar disorder and his substance use. He has been more compliant with his mood stabilizing and antidepressant medication, and his psychiatrist would like his dual diagnoses addressed with psychotherapy.

- Alcohol Use

- Elevated Mood

- Impulsivity

- Mania/Hypomania

- Mood Cycles

- Substance Abuse

Diagnoses and Related Treatments

1. bipolar disorder, 2. mixed substance use/dependence.

Thank you for supporting the Society of Clinical Psychology. To enhance our membership benefits, we are requesting that members fill out their profile in full. This will help the Division to gather appropriate data to provide you with the best benefits. You will be able to access all other areas of the website, once your profile is submitted. Thank you and please feel free to email the Central Office at [email protected] if you have any questions

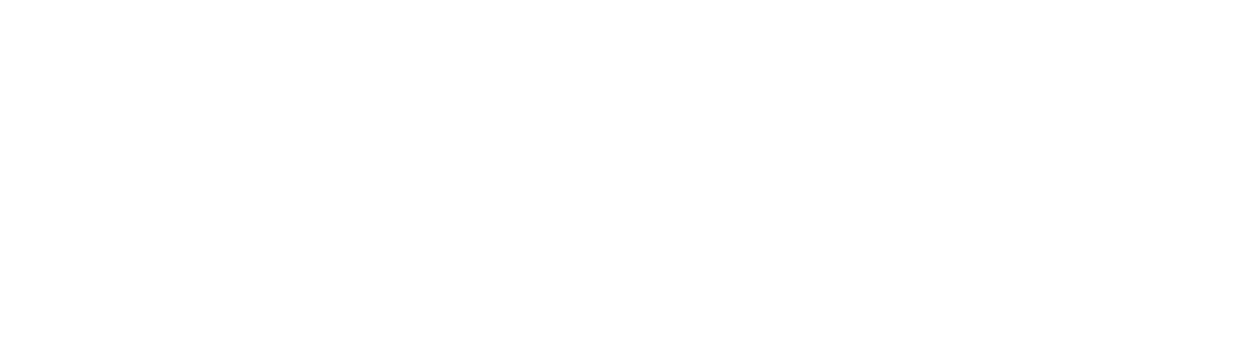

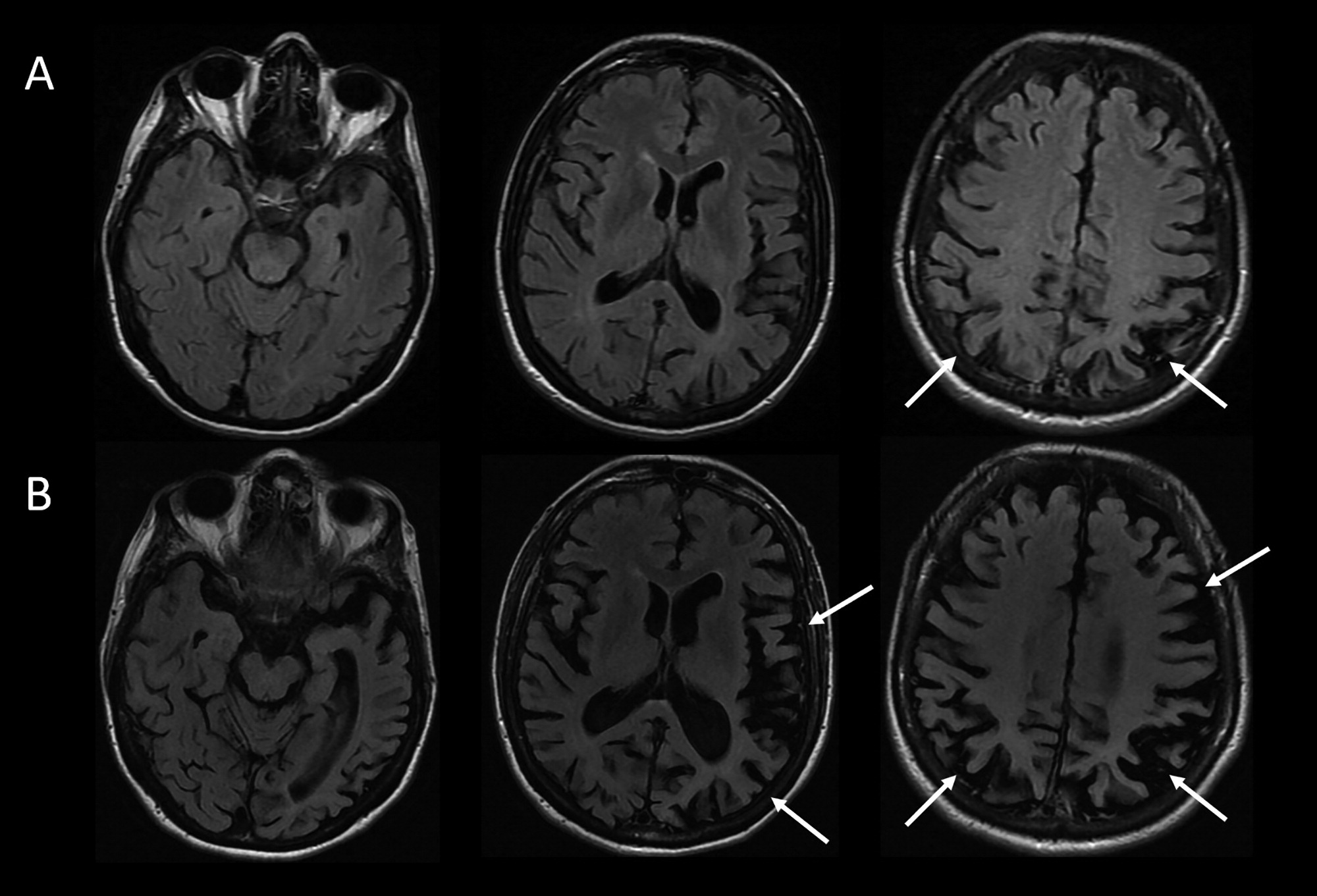

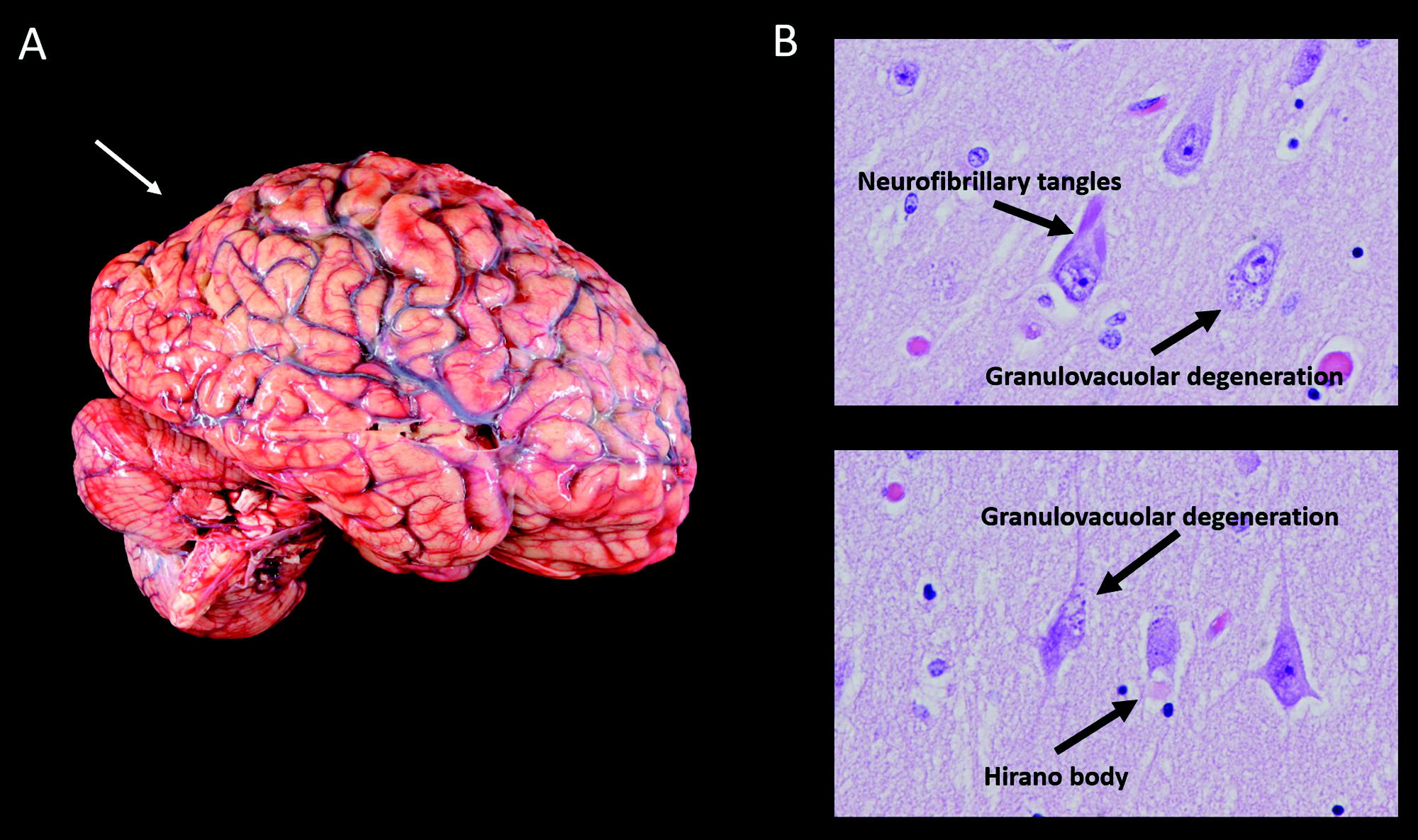

Case Study 1: A 55-Year-Old Woman With Progressive Cognitive, Perceptual, and Motor Impairments

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, case presentation, what are diagnostic considerations based on the history how might a clinical examination help to narrow the differential diagnosis.

How Does the Examination Contribute to Our Understanding of Diagnostic Considerations? What Additional Tests or Studies Are Indicated?

| Feature | Posterior cortical atrophy | Corticobasal syndrome |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive and motor features | Visual-perceptual: space perception deficit, simultanagnosia, object perception deficit, environmental agnosia, alexia, apperceptive prosopagnosia, and homonymous visual field defect | Motor: limb rigidity or akinesia, limb dystonia, and limb myoclonus |

| Visual-motor: constructional dyspraxia, oculomotor apraxia, optic ataxia, and dressing apraxia | ||

| Other: left/right disorientation, acalculia, limb apraxia, agraphia, and finger agnosia | Higher cortical features: limb or orobuccal apraxia, cortical sensory deficit, and alien limb phenomena | |

| Imaging features (MRI, FDG-PET, SPECT) | Predominant occipito-parietal or occipito-temporal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion | Asymmetric perirolandic, posterior frontal, parietal atrophy, and hypometabolism or hypoperfusion |

| Neuropathological associations | AD>CBD, LBD, TDP, JCD | CBD>PSP, AD, TDP |

Considering This Additional Data, What Would Be an Appropriate Diagnostic Formulation?

Does information about the longitudinal course of her illness alter the formulation about the most likely underlying neuropathological process, neuropathology.

| Feature | Case of PCA/CBS due to AD | Exemplar case of CBD |

|---|---|---|

| Macroscopic findings | Cortical atrophy: symmetric, mild | Cortical atrophy: often asymmetric, predominantly affecting perirolandic cortex |

| Substantia nigra: appropriately pigmented | Substantia nigra: severely depigmented | |

| Microscopic findings | Tau neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques | Primary tauopathy |

| No tau pathology in white matter | Tau pathology involves white matter | |

| Hirano bodies, granulovacuolar degeneration | Ballooned neurons, astrocytic plaques, and oligodendroglial coiled bodies | |

| (Lewy bodies, limbic) |

Information

Published in.

- Posterior Cortical Atrophy

- Corticobasal Syndrome

- Atypical Alzheimer Disease

- Network Degeneration

Competing Interests

Funding information, export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Transforming the understanding and treatment of mental illnesses.

Información en español

Celebrating 75 Years! Learn More >>

- Science News

- Meetings and Events

- Social Media

- Press Resources

- Email Updates

- Innovation Speaker Series

Genomic Data From More Than 41,000 People Shed New Light on Bipolar Disorder

September 29, 2021 • Research Highlight

In the largest genome-wide association study of bipolar disorder to date, researchers found about twice as many genetic locations associated with bipolar disorder as reported in previous studies. These and other genome-wide findings help improve our understanding of the biological origins of bipolar disorder and suggest some promising genes for further research.

The study, led by the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium bipolar disorder working group, is published in Nature Genetics . The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium is a global collaborative effort consisting of more than 800 investigators, including researchers in the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) Intramural Research Program and extramural scientists conducting NIMH-supported research.

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness characterized by episodes of mania and depression that can seriously impair day-to-day functioning. Affecting up to 50 million people worldwide, bipolar disorder is a major public health concern. Although evidence suggests that genes play an important role in the development of bipolar disorder, researchers still do not have a clear understanding of the disorder’s specific biological causes. Examining common genetic variations in the genomes (or complete set of DNA) of people with bipolar disorder is a way that scientists can home in on the genetic factors that are likely to play a causal role in the disorder.

For this study, the researchers analyzed genomic data from 57 groups of participants across Europe, North America, and Australia. These cohorts included individuals receiving clinical care for bipolar disorder and individuals classified as having bipolar disorder based on data from health registries, electronic health records, or repositories. The total combined sample included 41,917 individuals with bipolar disorder and 371,549 individuals without bipolar disorder.

The researchers used an approach known as a genome-wide association study (GWAS) , which allowed them to identify common genetic variations that are more likely to occur in people with bipolar disorder. Identifying these variations can provide important clues about the biological pathways and processes that are likely to be involved in the disorder.

According to the GWAS results, a total of 64 genomic locations, or risk loci , were associated with bipolar disorder even after accounting for all the variations studied across the genome. These 64 risk loci included 33 that had not been reported in previous bipolar disorder studies. Among the novel loci, the researchers found that bipolar disorder was associated with the major histocompatibility complex, which is a large group of genes involved in immune function. They also found a correlation between bipolar disorder and loci linked to other psychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia, major depression, and childhood-onset disorders such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

The study findings also revealed genome-wide genetic overlaps, or correlations, between bipolar disorder and certain traits. For example, the results showed a genetic correlation between bipolar disorder and both alcohol use and smoking, as well as genetic correlations with some aspects of sleep (daytime sleepiness, insomnia, and sleep duration).

The researchers also compared genetic overlap between the two types of bipolar disorder: bipolar I disorder (which includes manic episodes and, typically, depressive episodes) and bipolar II disorder (which includes depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes). As expected, the results indicated a substantial but incomplete genetic overlap between the two types. Comparing the two types and their associations with other psychiatric disorders, the researchers found that bipolar I disorder showed a stronger genetic correlation with schizophrenia, whereas bipolar II disorder was more closely correlated with major depression. Additional studies with detailed trait data for large cohorts will be essential for further understanding the genetic components of these bipolar disorder types.

Drawing from the GWAS results, the researchers found that the 64 risk loci contained at least 161 individual genes. Some of these genes play a role in how neurons signal to each other in the brain. Some of these genes are also known to be targets for certain types of drugs currently used to treat bipolar disorder, such as antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, and antiepileptics. And some genes are known to be targets for other drug types, including calcium channel blockers (typically used to treat high blood pressure) and certain anesthetics.

The researchers then used an analytic technique called “fine-mapping” to connect risk loci with specific genes that are most likely to play a causal role in bipolar disorder. This technique identified 15 genes with the strongest evidence, which suggests they are promising candidates for further study.

Overall, the study findings confirmed many of the risk loci and genetic correlations reported in previous studies. But the study also represents an advance for the field, as a 1.5-fold increase in the number of participants effectively doubled the number of loci identified as associated with bipolar disorder. According to the researchers, this marks an “inflection point” in discovery because it indicates that the number of loci identified will continue to increase rapidly with the addition of new cohorts.

Taken together, these findings establish a more detailed picture of the genetic factors that underlie bipolar disorder and suggest possible biological targets for new treatments.

Mullins, N., Forstner, A. J., O’Connell, K. S., Coombes, B., Coleman, J. R., Qiao, Z., Als, T. D., Bigdeli, T. B., Børte, S., Bryois, J., Charney, A. W., Drange, O. K., Gandal, M. J., Hagenaars, S. P., Ikeda, M., Kamitaki, N., Kim, M., Krebs, K., Panagiotaropoulou, G.,…Andreassen, O.A. (2021). Genome-wide association study of more than 40,000 bipolar disorder cases provides new insights into the underlying biology. Nature Genetics, 53, 817–829. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-021-00857-4

MH109528 , MH094421 , MH085520

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cambridge Open

Genetic contributions to bipolar disorder: current status and future directions

Kevin s. o'connell.

1 Division of Mental Health and Addiction, NORMENT Centre, Institute of Clinical Medicine, University of Oslo, Oslo University Hospital, 0407Oslo, Norway

Brandon J. Coombes

2 Department of Health Sciences Research, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a highly heritable mental disorder and is estimated to affect about 50 million people worldwide. Our understanding of the genetic etiology of BD has greatly increased in recent years with advances in technology and methodology as well as the adoption of international consortiums and large population-based biobanks. It is clear that BD is also highly heterogeneous and polygenic and shows substantial genetic overlap with other psychiatric disorders. Genetic studies of BD suggest that the number of associated loci is expected to substantially increase in larger future studies and with it, improved genetic prediction of the disorder. Still, a number of challenges remain to fully characterize the genetic architecture of BD. First among these is the need to incorporate ancestrally-diverse samples to move research away from a Eurocentric bias that has the potential to exacerbate health disparities already seen in BD. Furthermore, incorporation of population biobanks, registry data, and electronic health records will be required to increase the sample size necessary for continued genetic discovery, while increased deep phenotyping is necessary to elucidate subtypes within BD. Lastly, the role of rare variation in BD remains to be determined. Meeting these challenges will enable improved identification of causal variants for the disorder and also allow for equitable future clinical applications of both genetic risk prediction and therapeutic interventions.

Definition of illness

Affective disorders are classified along a spectrum from unipolar depression to bipolar disorder (BD) type II and type I (Carvalho, Firth, & Vieta, 2020 ; Grande, Berk, Birmaher, & Vieta, 2016 ). The presence of recurring manic or hypomanic episodes alternating with euthymia or depressive episodes distinguishes BD from other affective disorders (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ; World Health Organization et al., 1992 ). BD type I (BDI) is characterized by alternating manic and depressive episodes ( Fig. 1 ). Psychotic symptoms also occur in a majority of these patients which may lead to compromised functioning and hospitalization. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) also allows for individuals impaired by manic episodes without depression to still be diagnosed with BDI (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). In comparison, a diagnosis of BD type II (BDII) is based on the occurrence of at least one depressive and one hypomanic episode during the lifetime, but no manic episodes ( Fig. 1 ). A diagnosis of BD not otherwise specified or BD unspecified may be given when a patient has bipolar symptoms that do not fit within these major subtype categories. The DSM-5 also includes specifiers which define the clinical features of episodes and the course of the disorder, namely, anxious distress, mixed features, rapid cycling, melancholic features, atypical features, psychotic features (mood-congruent and mood-incongruent), catatonia, peripartum onset, and seasonal pattern (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ). In addition, the DSM-5 includes schizoaffective BD as a distinct diagnosis wherein individuals suffer from psychotic symptoms as well as episodes of mania or depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ).

Polarity of symptoms for bipolar disorder subtypes. Bipolar disorder type I is characterized by at least one manic episode. Bipolar disorder type II is characterized by at least one depressive and one hypomanic episode during the lifetime, but no manic episodes. Major depressive disorder does not include episodes of hypomania or mania.

Epidemiology

BD is projected to affect about 50 million people worldwide (GBD 2016 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators, 2017 ). The BD subtypes each have an estimated lifetime prevalence of approximately 1% (Merikangas et al., 2007 , 2011 ) although large ranges in lifetime prevalence have been reported (BDI: 0.1–1.7%, BDII: 0.1–3.0%) (Angst, 1998 ; Merikangas et al., 2007 , 2011 ). Most studies report no gender differences in the prevalence of BD; however, women may be at increased risk for BDII, rapid cycling, and mixed episodes (Diflorio & Jones, 2010 ; Nivoli et al., 2011 ). The mean age of onset of BD is at approximately 20 years. An earlier age of onset is associated with poorer prognosis, increased comorbidity, onset beginning with depression, and more severe depressive episodes, as well as longer treatment delays (Joslyn, Hawes, Hunt, & Mitchell, 2016 ). Additionally, initial depressive episodes may lead to a misdiagnosis of major depressive disorder until the onset of manic or hypomanic episodes necessary to confirm BD (Zimmerman, Ruggero, Chelminski, & Young, 2008 ).

BD is often comorbid with other psychiatric (Eser, Kacar, Kilciksiz, Yalçinay-Inan, & Ongur, 2018 ; Frías, Baltasar, & Birmaher, 2016 ; Salloum & Brown, 2017 ) and non-psychiatric disorders (Bortolato, Berk, Maes, McIntyre, & Carvalho, 2016 ; Correll et al., 2017 ; Vancampfort et al., 2016 ). It is estimated that >90% of BD patients have at least one lifetime comorbid disorder, and >70% present with three or more comorbid disorders during their lifetime (Merikangas et al., 2007 ). Such ubiquitous comorbidity within BD suggests the disturbance of multiple systems and pathways, and the presence of comorbidities is associated with increased premature mortality in BD when compared to the general population (Kessing, Vradi, McIntyre, & Andersen, 2015 ; Roshanaei-Moghaddam & Katon, 2009 ).

Classical genetic epidemiology

Family studies.