An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Color and psychological functioning: a review of theoretical and empirical work

In the past decade there has been increased interest in research on color and psychological functioning. Important advances have been made in theoretical work and empirical work, but there are also important weaknesses in both areas that must be addressed for the literature to continue to develop apace. In this article, I provide brief theoretical and empirical reviews of research in this area, in each instance beginning with a historical background and recent advancements, and proceeding to an evaluation focused on weaknesses that provide guidelines for future research. I conclude by reiterating that the literature on color and psychological functioning is at a nascent stage of development, and by recommending patience and prudence regarding conclusions about theory, findings, and real-world application.

The past decade has seen enhanced interest in research in the area of color and psychological functioning. Progress has been made on both theoretical and empirical fronts, but there are also weaknesses on both of these fronts that must be attended to for this research area to continue to make progress. In the following, I briefly review both advances and weaknesses in the literature on color and psychological functioning.

Theoretical Work

Background and recent developments.

Color has fascinated scholars for millennia ( Sloane, 1991 ; Gage, 1993 ). Theorizing on color and psychological functioning has been present since Goethe (1810) penned his Theory of Colors , in which he linked color categories (e.g., the “plus” colors of yellow, red–yellow, yellow–red) to emotional responding (e.g., warmth, excitement). Goldstein (1942) expanded on Goethe’s intuitions, positing that certain colors (e.g., red, yellow) produce systematic physiological reactions manifest in emotional experience (e.g., negative arousal), cognitive orientation (e.g., outward focus), and overt action (e.g., forceful behavior). Subsequent theorizing derived from Goldstein’s ideas has focused on wavelength, positing that longer wavelength colors feel arousing or warm, whereas shorter wavelength colors feel relaxing or cool ( Nakashian, 1964 ; Crowley, 1993 ). Other conceptual statements about color and psychological functioning have focused on general associations that people have to colors and their corresponding influence on downstream affect, cognition, and behavior (e.g., black is associated with aggression and elicits aggressive behavior; Frank and Gilovich, 1988 ; Soldat et al., 1997 ). Finally, much writing on color and psychological functioning has been completely atheoretical, focused exclusively on finding answers to applied questions (e.g., “What wall color facilitates worker alertness and productivity?”). The aforementioned theories and conceptual statements continue to motivate research on color and psychological functioning. However, several other promising theoretical frameworks have also emerged in the past decade, and I review these frameworks in the following.

Hill and Barton (2005) noted that in many non-human animals, including primate species, dominance in aggressive encounters (i.e., superior physical condition) is signaled by the bright red of oxygenated blood visible on highly vascularized bare skin. Artificial red (e.g., on leg bands) has likewise been shown to signal dominance in non-human animals, mimicking the natural physiological process ( Cuthill et al., 1997 ). In humans in aggressive encounters, a testosterone surge produces visible reddening on the face and fear leads to pallor ( Drummond and Quay, 2001 ; Levenson, 2003 ). Hill and Barton (2005) posited that the parallel between humans and non-humans present at the physiological level may extend to artificial stimuli, such that wearing red in sport contests may convey dominance and lead to a competitive advantage.

Other theorists have also utilized a comparative approach in positing links between skin coloration and the evaluation of conspecifics. Changizi et al. (2006) and Changizi (2009) contend that trichromatic vision evolved to enable primates, including humans, to detect subtle changes in blood flow beneath the skin that carry important information about the emotional state of the conspecific. Increased red can convey anger, embarrassment, or sexual arousal, whereas increased bluish or greenish tint can convey illness or poor physiological condition. Thus, visual sensitivity to these color modulations facilitates various forms of social interaction. In similar fashion, Stephen et al. (2009) and Stephen and McKeegan (2010) propose that perceivers use information about skin coloration (perhaps particularly from the face, Tan and Stephen, 2012 ) to make inferences about the attractiveness, health, and dominance of conspecifics. Redness (from blood oxygenization) and yellowness (from carotenoids) are both seen as facilitating positive judgments. Fink et al. (2006) and Fink and Matts (2007) posit that the homogeneity of skin coloration is an important factor in evaluating the age, attractiveness, and health of faces.

Elliot and Maier (2012) have proposed color-in-context theory, which draws on social learning, as well as biology. Some responses to color stimuli are presumed to be solely due to the repeated pairing of color and particular concepts, messages, and experiences. Others, however, are presumed to represent a biologically engrained predisposition that is reinforced and shaped by social learning. Through this social learning, color associations can be extended beyond natural bodily processes (e.g., blood flow modulations) to objects in close proximity to the body (e.g., clothes, accessories). Thus, for example, red may not only increase attractiveness evaluations when viewed on the face, but also when viewed on a shirt or dress. As implied by the name of the theory, the physical and psychological context in which color is perceived is thought to influence its meaning and, accordingly, responses to it. Thus, blue on a ribbon is positive (indicating first place), but blue on a piece of meat is negative (indicating rotten), and a red shirt may enhance the attractiveness of a potential mate (red = sex/romance), but not of a person evaluating one’s competence (red = failure/danger).

Meier and Robinson (2005) and Meier (in press ) have posited a conceptual metaphor theory of color. From this perspective, people talk and think about abstract concepts in concrete terms grounded in perceptual experience (i.e., they use metaphors) to help them understand and navigate their social world ( Lakoff and Johnson, 1999 ). Thus, anger entails reddening of the face, so anger is metaphorically described as “seeing red,” and positive emotions and experiences are often depicted in terms of lightness (rather than darkness), so lightness is metaphorically linked to good (“seeing the light”) rather than bad (“in the dark”). These metaphoric associations are presumed to have implications for important outcomes such as morality judgments (e.g., white things are viewed as pure) and stereotyping (e.g., dark faces are viewed more negatively).

For many years it has been known that light directly influences physiology and increases arousal (see Cajochen, 2007 , for a review), but recently theorists have posited that such effects are wavelength dependent. Blue light, in particular, is posited to activate the melanopsin photoreceptor system which, in turn, activates the brain structures involved in sub-cortical arousal and higher-order attentional processing ( Cajochen et al., 2005 ; Lockley et al., 2006 ). As such, exposure to blue light is expected to facilitate alertness and enhance performance on tasks requiring sustained attention.

Evaluation and Recommendations

Drawing on recent theorizing in evolutionary psychology, emotion science, retinal physiology, person perception, and social cognition, the aforementioned conceptualizations represent important advances to the literature on color and psychological functioning. Nevertheless, theory in this area remains at a nascent level of development, and the following weaknesses may be identified.

First, the focus of theoretical work in this area is either extremely specific or extremely general. A precise conceptual proposition such as red signals dominance and leads to competitive advantage in sports ( Hill and Barton, 2005 ) is valuable in that it can be directly translated into a clear, testable hypothesis; however, it is not clear how this specific hypothesis connects to a broader understanding of color–performance relations in achievement settings more generally. On the other end of the spectrum, a general conceptualization such as color-in-context theory ( Elliot and Maier, 2012 ) is valuable in that it offers several widely applicable premises; however, these premises are only vaguely suggestive of precise hypotheses in specific contexts. What is needed are mid-level theoretical frameworks that comprehensively, yet precisely explain and predict links between color and psychological functioning in specific contexts (for emerging developments, see Pazda and Greitemeyer, in press ; Spence, in press ; Stephen and Perrett, in press ).

Second, the extant theoretical work is limited in scope in terms of range of hues, range of color properties, and direction of influence. Most theorizing has focused on one hue, red, which is understandable given its prominence in nature, on the body, and in society ( Changizi, 2009 ; Elliot and Maier, 2014 ); however, other hues also carry important associations that undoubtedly have downstream effects (e.g., blue: Labrecque and Milne, 2012 ; green: Akers et al., 2012 ). Color has three basic properties: hue, lightness, and chroma ( Fairchild, 2013 ). Variation in any or all of these properties could influence downstream affect, cognition, or behavior, yet only hue is considered in most theorizing (most likely because experientially, it is the most salient color property). Lightness and chroma also undoubtedly have implications for psychological functioning (e.g., lightness: Kareklas et al., 2014 ; chroma: Lee et al., 2013 ); lightness has received some attention within conceptual metaphor theory ( Meier, in press ; see also Prado-León and Rosales-Cinco, 2011 ), but chroma has been almost entirely overlooked, as has the issue of combinations of hue, lightness, and chroma. Finally, most theorizing has focused on color as an independent variable rather than a dependent variable; however, it is also likely that many situational and intrapersonal factors influence color perception (e.g., situational: Bubl et al., 2009 ; intrapersonal: Fetterman et al., 2015 ).

Third, theorizing to date has focused primarily on main effects, with only a modicum of attention allocated to the important issue of moderation. As research literatures develop and mature, they progress from a sole focus on “is” questions (“Does X influence Y?”) to additionally considering “when” questions (“Under what conditions does X influence Y and under what conditions does X not influence Y?”). These “second generation” questions ( Zanna and Fazio, 1982 , p. 283) can seem less exciting and even deflating in that they posit boundary conditions that constrain the generalizability of an effect. Nevertheless, this step is invaluable in that it adds conceptual precision and clarity, and begins to address the issue of real-world applicability. All color effects undoubtedly depend on certain conditions – culture, gender, age, type of task, variant of color, etc. – and acquiring an understanding of these conditions will represent an important marker of maturity for this literature (for movement in this direction, see Schwarz and Singer, 2013 ; Tracy and Beall, 2014 ; Bertrams et al., 2015 ; Buechner et al., in press ; Young, in press ). Another, more succinct, way to state this third weakness is that theorizing in this area needs to take context, in all its forms, more seriously.

Empirical Work

Empirical work on color and psychological functioning dates back to the late 19th century ( Féré, 1887 ; see Pressey, 1921 , for a review). A consistent feature of this work, from its inception to the past decade, is that it has been fraught with major methodological problems that have precluded rigorous testing and clear interpretation ( O’Connor, 2011 ). One problem has been a failure to attend to rudimentary scientific procedures such as experimenter blindness to condition, identifying, and excluding color deficient participants, and standardizing the duration of color presentation or exposure. Another problem has been a failure to specify and control for color at the spectral level in manipulations. Without such specification, it is impossible to know what precise combination of color properties was investigated, and without such control, the confounding of focal and non-focal color properties is inevitable ( Whitfield and Wiltshire, 1990 ; Valdez and Mehrabian, 1994 ). Yet another problem has been the use of underpowered samples. This problem, shared across scientific disciplines ( Maxwell, 2004 ), can lead to Type I errors, Type II errors, and inflated effect sizes ( Fraley and Vazire, 2014 ; Murayama et al., 2014 ). Together, these methodological problems have greatly hampered progress in this area.

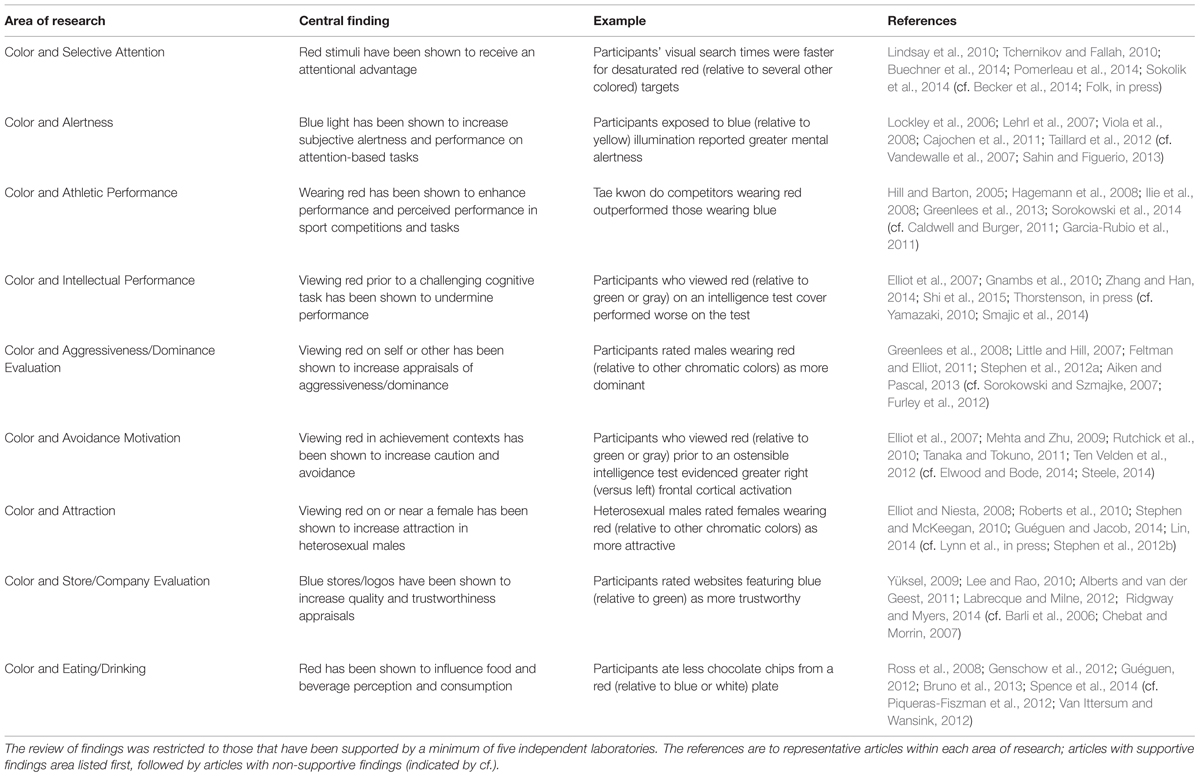

Although some of the aforementioned problems remain (see “Evaluation and Recommendations” below), others have been rectified in recent work. This, coupled with advances in theory development, has led to a surge in empirical activity. In the following, I review the diverse areas in which color work has been conducted in the past decade, and the findings that have emerged. Space considerations require me to constrain this review to a brief mention of central findings within each area. I focus on findings with humans (for reviews of research with non-human animals, see Higham and Winters, in press ; Setchell, in press ) that have been obtained in multiple (at least five) independent labs. Table Table1 1 provides a summary, as well as representative examples and specific references.

Research on color and psychological functioning.

| Area of research | Central finding | Example | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Color and Selective Attention | Red stimuli have been shown to receive an attentional advantage | Participants’ visual search times were faster for desaturated red (relative to several other colored) targets | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Alertness | Blue light has been shown to increase subjective alertness and performance on attention-based tasks | Participants exposed to blue (relative to yellow) illumination reported greater mental alertness | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Athletic Performance | Wearing red has been shown to enhance performance and perceived performance in sport competitions and tasks | Tae kwon do competitors wearing red outperformed those wearing blue | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Intellectual Performance | Viewing red prior to a challenging cognitive task has been shown to undermine performance | Participants who viewed red (relative to green or gray) on an intelligence test cover performed worse on the test | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Aggressiveness/Dominance Evaluation | Viewing red on self or other has been shown to increase appraisals of aggressiveness/dominance | Participants rated males wearing red (relative to other chromatic colors) as more dominant | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Avoidance Motivation | Viewing red in achievement contexts has been shown to increase caution and avoidance | Participants who viewed red (relative to green or gray) prior to an ostensible intelligence test evidenced greater right (versus left) frontal cortical activation | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Attraction | Viewing red on or near a female has been shown to increase attraction in heterosexual males | Heterosexual males rated females wearing red (relative to other chromatic colors) as more attractive | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Store/Company Evaluation | Blue stores/logos have been shown to increase quality and trustworthiness appraisals | Participants rated websites featuring blue (relative to green) as more trustworthy | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

| Color and Eating/Drinking | Red has been shown to influence food and beverage perception and consumption | Participants ate less chocolate chips from a red (relative to blue or white) plate | ; ; ; ; (cf. ; ) |

In research on color and selective attention, red stimuli have been shown to receive an attentional advantage (see Folk, in press , for a review). Research on color and alertness has shown that blue light increases subjective alertness and performance on attention-based tasks (see Chellappa et al., 2011 , for a review). Studies on color and athletic performance have linked wearing red to better performance and perceived performance in sport competitions and tasks (see Maier et al., in press , for a review). In research on color and intellectual performance, viewing red prior to a challenging cognitive task has been shown to undermine performance (see Shi et al., 2015 , for a review). Research focused on color and aggressiveness/dominance evaluation has shown that viewing red on self or other increases appraisals of aggressiveness and dominance (see Krenn, 2014 , for a review). Empirical work on color and avoidance motivation has linked viewing red in achievement contexts to increased caution and avoidance (see Elliot and Maier, 2014 , for a review). In research on color and attraction, viewing red on or near a female has been shown to enhance attraction in heterosexual males (see Pazda and Greitemeyer, in press , for a review). Research on color and store/company evaluation has shown that blue on stores/logos increases quality and trustworthiness appraisals (see Labrecque and Milne, 2012 , for a review). Finally, empirical work on color and eating/drinking has shown that red influences food and beverage perception and consumption (see Spence, in press , for a review).

The aforementioned findings represent important contributions to the literature on color and psychological functioning, and highlight the multidisciplinary nature of research in this area. Nevertheless, much like the extant theoretical work, the extant empirical work remains at a nascent level of development, due, in part, to the following weaknesses.

First, although in some research in this area color properties are controlled for at the spectral level, in most research it (still) is not. Color control is typically done improperly at the device (rather than the spectral) level, is impossible to implement (e.g., in web-based platform studies), or is ignored altogether. Color control is admittedly difficult, as it requires technical equipment for color assessment and presentation, as well as the expertise to use it. Nevertheless, careful color control is essential if systematic scientific work is to be conducted in this area. Findings from uncontrolled research can be informative in initial explorations of color hypotheses, but such work is inherently fraught with interpretational ambiguity ( Whitfield and Wiltshire, 1990 ; Elliot and Maier, 2014 ) that must be subsequently addressed.

Second, color perception is not only a function of lightness, chroma, and hue, but also of factors such as viewing distance and angle, amount and type of ambient light, and presence of other colors in the immediate background and general environmental surround ( Hunt and Pointer, 2011 ; Brainard and Radonjić, 2014 ; Fairchild, 2015 ). In basic color science research (e.g., on color physics, color physiology, color appearance modeling, etcetera; see Gegenfurtner and Ennis, in press ; Johnson, in press ; Stockman and Brainard, in press ), these factors are carefully specified and controlled for in order to establish standardized participant viewing conditions. These factors have been largely ignored and allowed to vary in research on color and psychological functioning, with unknown consequences. An important next step for research in this area is to move to incorporate these more rigorous standardization procedures widely utilized by basic color scientists. With regard to both this and the aforementioned weakness, it should be acknowledged that exact and complete control is not actually possible in color research, given the multitude of factors that influence color perception ( Committee on Colorimetry of the Optical Society of America, 1953 ) and our current level of knowledge about and ability to control them ( Fairchild, 2015 ). As such, the standard that must be embraced and used as a guideline in this work is to control color properties and viewing conditions to the extent possible given current technology, and to keep up with advances in the field that will increasingly afford more precise and efficient color management.

Third, although in some research in this area, large, fully powered samples are used, much of the research remains underpowered. This is a problem in general, but it is particularly a problem when the initial demonstration of an effect is underpowered (e.g., Elliot and Niesta, 2008 ), because initial work is often used as a guide for determining sample size in subsequent work (both heuristically and via power analysis). Underpowered samples commonly produce overestimated effect size estimates ( Ioannidis, 2008 ), and basing subsequent sample sizes on such estimates simply perpetuates the problem. Small sample sizes can also lead researchers to prematurely conclude that a hypothesis is disconfirmed, overlooking a potentially important advance ( Murayama et al., 2014 ). Findings from small sampled studies should be considered preliminary; running large sampled studies with carefully controlled color stimuli is essential if a robust scientific literature is to be developed. Furthermore, as the “evidentiary value movement” ( Finkel et al., 2015 ) makes inroads in the empirical sciences, color scientists would do well to be at the leading edge of implementing such rigorous practices as publically archiving research materials and data, designating exploratory from confirmatory analyses, supplementing or even replacing significant testing with “new statistics” ( Cumming, 2014 ), and even preregistering research protocols and analyses (see Finkel et al., 2015 , for an overview).

In both reviewing advances in and identifying weaknesses of the literature on color and psychological functioning, it is important to bear in mind that the existing theoretical and empirical work is at an early stage of development. It is premature to offer any bold theoretical statements, definitive empirical pronouncements, or impassioned calls for application; rather, it is best to be patient and to humbly acknowledge that color psychology is a uniquely complex area of inquiry ( Kuehni, 2012 ; Fairchild, 2013 ) that is only beginning to come into its own. Findings from color research can be provocative and media friendly, and the public (and the field as well) can be tempted to reach conclusions before the science is fully in place. There is considerable promise in research on color and psychological functioning, but considerably more theoretical and empirical work needs to be done before the full extent of this promise can be discerned and, hopefully, fulfilled.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

- Aiken K. D., Pascal V. J. (2013). Seeing red, feeling red: how a change in field color influences perceptions. Int. J. Sport Soc. 3 107–120. [ Google Scholar ]

- Akers A., Barton J., Cossey R., Gainsford P., Griffin M., Micklewright D. (2012). Visual color perception in green exercise: positive effects of mood on perceived exertion. Environ. Sci. Technol. 46 8661–8666 10.1021/es301685g [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alberts W., van der Geest T. M. (2011). Color matters: color as trustworthiness cue in websites. Tech. Comm. 58 149–160. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barli Ö., Bilgili B., Dane Ş. (2006). Association of consumers’ sex and eyedness and lighting and wall color of a store with price attraction and perceived quality of goods and inside visual appeal. Percept. Motor Skill 103 447–450 10.2466/PMS.103.6.447-450 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Becker S. I., Valuch C., Ansorge U. (2014). Color priming in pop-out search depends on the relative color of the target. Front. Psychol. 5 : 289 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00289 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bertrams A., Baumeister R. F., Englert C., Furley P. (2015). Ego depletion in color priming research: self-control strength moderates the detrimental effect of red on cognitive test performance. Pers. Soc. Psychol. B. 41 311–322 10.1177/0146167214564968 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brainard D. H., Radonjić A. (2014). “Color constancy” in The New Visual Neurosciences , eds Werner J., Chalupa L. (Cambridge, MA; MIT Press; ), 545–556. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bruno N., Martani M., Corsini C., Oleari C. (2013). The effect of the color red on consuming food does not depend on achromatic (Michelson) contrast and extends to rubbing cream on the skin. Appetite 71 307–313 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.012 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bubl E., Kern E., Ebert D., Bach M., Tebartz van Elst L. (2009). Seeing gray when feeling blue? Depression can be measures in the eye of the diseased. Biol. Psychiat. 68 205–208 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.02.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Buechner V. L., Maier M. A., Lichtenfeld S., Elliot A. J. Emotion expression and color: their joint influence on perceptions of male attractiveness and social position. Curr. Psychol . (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Buechner V. L., Maier M. A., Lichtenfeld S., Schwarz S. (2014). Red – take a closer look. PLoS ONE 9 : e108111 10.1371/journal.pone.0108111 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C. (2007). Alerting effects of light. Sleep Med. Rev . 11 453–464 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.009 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C., Frey S., Anders D., Späti J., Bues M., Pross A., et al. (2011). Evening exposure to a light-emitting diodes (LED)-backlit computer screen affects circadian physiology and cognitive performance. J. Appl. Phsysoil. 110 1432–1438 10.1152/japplphysiol.00165.2011 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cajochen C., Münch M., Kobialka S., Kräuchi K., Steiner R., Oelhafen P., et al. (2005). High sensitivity of human melatonin, alertness, thermoregulation, and heart rate to short wavelength light. J. Clin. Endocr. Metab. 90 1311–1316 10.1210/jc.2004-0957 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Caldwell D. F., Burger J. M. (2011). On thin ice: does uniform color really affect aggression in professional hockey? Soc. Psychol. Pers. Sci. 2 306–310 10.1177/1948550610389824 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Changizi M. (2009). The Vision Revolution . Dallas, TX: Benbella. [ Google Scholar ]

- Changizi M. A., Zhang Q., Shimojo S. (2006). Bare skin, blood and the evolution of primate colour vision. Biol. Lett. 2 217–221 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0440 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chebat J. C., Morrin M. (2007). Colors and cultures: exploring the effects of mall décor on consumer perceptions. J. Bus. Res. 60 189–196 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.11.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chellappa S. L., Steiner R., Blattner P., Oelhafen P., Götz T., Cajochen C. (2011). Non-visual effects of light on melatonin, alertness, and cognitive performance: can blue-enriched light keep us alert? PLoS ONE 26 : e16429 10.1371/journal.pone.0016429 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Committee on Colorimetry of the Optical Society of America (1953). The Science of Color . Washington, DC: Optical Society of America. [ Google Scholar ]

- Crowley A. E. (1993). The two dimensional impact of color on shopping. Market. Lett. 4 59–69 10.1007/BF00994188 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cumming G. (2014). The new statistics: why and how. Psychol. Sci. 25 7–29 10.1177/0956797613504966 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cuthill I. C., Hunt S., Cleary C., Clark C. (1997). Color bands, dominance, and body mass regulation in male zebra finches ( Taeniopygia guttata ). Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Sci. 264 1093–1099 10.1098/rspb.1997.0151 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Drummond P. D., Quay S. H. (2001). The effect of expressing anger on cardiovascular reactivity and facial blood flow in Chinese and Caucasians. Psychophysiology 38 190–196 10.1111/1469-8986.3820190 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A. (2012). Color-in-context theory. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 45 61–125 10.1016/B978-0-12-394286-9.00002-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A. (2014). Color psychology: effects of perceiving color on psychological functioning in humans. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 65 95–120 10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115035 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Maier M. A., Moller A. C., Friedman R., Meinhardt J. (2007). Color and psychological functioning: the effect of red on performance attainment. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 136 154–168 10.1037/0096-3445.136.1.154 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliot A. J., Niesta D. (2008). Romantic red: red enhances men’s attraction to women. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 95 1150–1164 10.1037/0022-3514.95.5.1150 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elwood J. A., Bode J. (2014). Student preferences vis-à-vis teacher feedback in university EFL writing classes in Japan. System 42 333–343 10.1016/j.system.2013.12.023 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairchild M. D. (2013). Color Appearance Models, 3rd Edn New York, NY: Wiley Press; 10.1002/9781118653128 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fairchild M. D. (2015). Seeing, adapting to, and reproducing the appearance of nature. Appl. Optics 54 B107–B116 10.1364/AO.54.00B107 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feltman R., Elliot A. J. (2011). The influence of red on perceptions of dominance and threat in a competitive context. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 33 308–314. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fetterman A. K., Liu T., Robinson M. D. (2015). Extending color psychology to the personality realm: interpersonal hostility varied by red preferences and perceptual biases. J. Personal. 83 106–116 10.1111/jopy.12087 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Féré C. (1887). Note sur les conditions physiologiques des émotions. Revue Phil. 24 561–581. [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink B., Grammer K., Matts P. J. (2006). Visible skin color distribution plays a role in the perception of age, attractiveness, and health in female faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 27 433–442 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.08.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fink B., Matts P. J. (2007). The effects of skin colour distribution and topography cues on the perception of female age and health. J. Eur. Acad. Derm. 22 493–498 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2007.02512.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Finkel E. J., Eastwick P. W., Reis H. T. (2015). Best research practices in psychology: Illustrating epistemological and pragmatic considerations with the case of relationship science. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 108 275–297 10.1037/pspi0000007 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Folk C. L. (in press) “The role of color in the voluntary and involuntary guidance of selective attention,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Fraley R. C., Vazire S. (2014). The N-pact factor: evaluating the quality of empirical journals with respect to sample size and statistical power. PLoS ONE 9 : e109019 10.1371/journal.pone.0109019 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Frank M. G., Gilovich T. (1988). The dark side of self and social perception: black uniforms and aggression in professional sports. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54 74–85 10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.74 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Furley P., Dicks M., Memmert D. (2012). Nonverbal behavior in soccer: the influence of dominant and submissive body language on the impression formation and expectancy of success of soccer players. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 34 61–82. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gage J. (1993). Color and Culture: Practice and Meaning from Antiquity to Abstraction . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Garcia-Rubio M. A., Picazo-Tadeo A. J., González-Gómez F. (2011). Does a red shirt improve sporting performance? Evidence from Spanish football. Appl. Econ. Lett. 18 1001–1004 10.1080/13504851.2010.520666 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gegenfurtner K. R., Ennis R. (in press) “Fundamentals of color vision II: higher order color processing,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Genschow O., Reutner L., Wänke M. (2012). The color red reduces snack food and soft Drink intake. Appetite 58 699–702 10.1016/j.appet.2011.12.023 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gnambs T., Appel M., Batinic B. (2010). Color red in web-based knowledge testing. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26 1625–1631 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Goethe W. (1810). Theory of Colors . London: Frank Cass. [ Google Scholar ]

- Goldstein K. (1942). Some experimental observations concerning the influence of colors on the function of the organism. Occup. Ther. Rehab. 21 147–151 10.1097/00002060-194206000-00002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenlees I. A., Eynon M., Thelwell R. C. (2013). Color of soccer goalkeepers’ uniforms influences the outcomed of penalty kicks. Percept. Mot. Skill. 116 1–10 10.2466/30.24.PMS.117x14z6 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Greenlees I., Leyland A., Thelwell R., Filby W. (2008). Soccer penalty takers’ uniform color and pre-penalty kick gaze affect the impressions formed of them by opposing goalkeepers. J. Sport Sci. 26 569–576 10.1080/02640410701744446 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guéguen N. (2012). Color and women attractiveness: when red clothed women are perceived to have more intense sexual intent. J. Soc. Psychol. 152 261–265 10.1080/00224545.2011.605398 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guéguen N., Jacob C. (2014). Coffee cup color and evaluation of a beverage’s “warmth quality.” Color Res. Appl. 39 79–81 10.1002/col.21757 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hagemann N., Strauss B., Leißing J. (2008). When the referee sees red. Psychol. Sci . 19 769–771 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02155.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Higham J. P., Winters S. (in press) “Color and mate choice in non-human animals,” in Handbook of Color Psychology, eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Hill R. A., Barton R. A. (2005). Red enhances human performance in contests. Nature 435 293 10.1038/435293a [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hunt R. W. G., Pointer M. R. (2011). Measuring Colour , 4th Edn New York, NY: Wiley Press; 10.1002/9781119975595 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ilie A., Ioan S., Zagrean L., Moldovan M. (2008). Better to be red than blue in virtual competition. Cyberpsychol. Behav. 11 375–377 10.1089/cpb.2007.0122 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ioannidis J. P. A. (2008). Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology 19 640–648 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818131e7 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson G. M. (in press) “Color appearance phenomena and visual illusions,” in Handbook of Color Psychology, eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Kareklas I., Brunel F. F., Coulter R. A. (2014). Judgment is not color blind: the impact of automatic color preference on product advertising preferences. J. Consum. Psychol. 24 87–95 10.1016/j.jcps.2013.09.005 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Krenn B. (2014). The impact of uniform color on judging tackles in association football. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 15 222–225 10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.11.007 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuehni R. (2012). Color: An Introduction to Practice and Principles , 3rd Edn New York, NY: Wiley; 10.1002/9781118533567 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Labrecque L. L., Milne G. R. (2012). Exciting red and competent blue: the importance of color in marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 40 711–727 10.1007/s11747-010-0245-y [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lakoff G., Johnson M. (1999). Philosophy in the Flesh: The Embodied Mind and its Challenges to Western Thought . New York, NY: Basic Books. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S., Lee K., Lee S., Song J. (2013). Origins of human color preference for food. J. Food Eng. 119 508–515 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.06.021 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee S., Rao V. S. (2010). Color and store choice in electronic commerce: the explanatory role of trust. J. Electr. Commer. Res. 11 110–126. [ Google Scholar ]

- Lehrl S., Gerstmeyer K., Jacob J. H., Frieling H., Henkel A. W., Meyrer R., et al. (2007). Blue light improves cognitive performance. J. Neural Trans. 114 457–460 10.1007/s00702-006-0621-4 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Levenson R. W. (2003). Blood, sweat, and fears: the automatic architecture of emotion. Ann. N. Y. Acad Sci. 1000 348–366 10.1196/annals.1280.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lin H. (2014). Red-colored products enhance the attractiveness of women. Displays 35 202–205 10.1016/j.displa.2014.05.009 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lindsay D. T., Brown A. M., Reijnen E., Rich A. N., Kuzmova Y. I., Wolfe J. M. (2010). Color channels, not color appearance of color categories, guide visual search for desaturated color targets. Psychol. Sci. 21 1208–1214 10.1177/0956797610379861 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Little A. C., Hill R. A. (2007). Attribution to red suggests special role in dominance signaling. J. Evol. Psychol. 5 161–168 10.1556/JEP.2007.1008 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lockley S. W., Evans E. E., Scheer F. A., Brainard G. C., Czeisler C. A., Aeschbach D. (2006). Short-wavelength sensitivity for the direct effects of light on alertness, vigilance, and the waking electroencephalogram in humans. Sleep 29 161–168. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lynn M., Giebelhausen M., Garcia S., Li Y., Patumanon I. Clothing color and tipping: an attempted replication and extension. J. Hosp. Tourism Res. doi: 10.1177/1096348013504001. (in press) [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maier M. A., Hill R., Elliot A. J., Barton R. A. (in press) “Color in achievement contexts in humans,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Maxwell S. (2004). The persistence of underpowered studies in psychological research: causes and consequences. Psychol. Methods 9 147–163 10.1037/1082-989X.9.2.147 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mehta R., Zhu R. (2009). Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on cognitive task performances. Science 323 1226–1229 10.1126/science.1169144 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier B. P. (in press) “Do metaphors color our perception of social life?,” in Handbook of Color sychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Meier B. P., Robinson M. D. (2005). The metaphorical representation of affect. Metaphor Symbol. 20 239–257 10.1207/s15327868ms2004_1 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Murayama K., Pekrun R., Fiedler K. (2014). Research practices that can prevent an inflation of false-positive rates. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18 107–118 10.1177/1088868313496330 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nakashian J. S. (1964). The effects of red and green surroundings on behavior. J. Gen. Psychol. 70 143–162 10.1080/00221309.1964.9920584 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- O’Connor Z. (2011). Colour psychology and colour therapy: caveat emptor. Color Res. Appl. 36 229–334 10.1002/col.20597 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pazda A. D., Greitemeyer T. (in press) “Color in romantic contexts in humans,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Piqueras-Fiszman B., Alcaide J., Roura E., Spence C. (2012). Is it the plate or is it the food? Assessing the influence of the color (black or white) and shape of the plate on the perception of food placed on it. Food Qual. Prefer. 24 205–208 10.1016/j.foodqual.2011.08.011 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pomerleau V. J., Fortier-Gauthier U., Corriveau I., Dell’Acqua R., Jolicœur P. (2014). Colour-specific differences in attentional deployment for equiluminant pop-out colours: evidence from lateralized potentials. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 91 194–205 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2013.10.016 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Prado-León L. R., Rosales-Cinco R. A. (2011). “Effects of lightness and saturation on color associations in the Mexican population,” in New Directions in Colour Studies , eds Biggam C., Hough C., Kay C., Simmons D. (Amsterdam, NL: John Benjamins Publishing Company; ), 389–394. [ Google Scholar ]

- Pressey S. L. (1921). The influence of color upon mental and motor efficiency. Am. J. Psychol. 32 327–356 10.2307/1413999 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ridgway J., Myers B. (2014). A study on brand personality: consumers’ perceptions of colours used in fashion brand logos. Int. J. Fash. Des. Tech. Educ. 7 50–57 10.1080/17543266.2013.877987 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Roberts S. C., Owen R. C., Havlicek J. (2010). Distinguishing between perceiver and wearer effects in clothing color-associated attributions. Evol. Psychol. 8 350–364. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ross C. F., Bohlscheid J., Weller K. (2008). Influence of visual masking technique on the assessment of 2 red wines by trained consumer assessors. J. Food Sci. 73 S279–S285 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00824.x [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Rutchick A. M., Slepian M. L., Ferris B. D. (2010). The pen is mightier than the word: object priming of evaluative standards. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 40 704–708 10.1002/ejsp.753 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sahin L., Figuerio M. G. (2013). Alerting effects of short-wavelength (blue) and long-wavelength (red) lights in the afternoon. Physiol. Behav. 116 1–7 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.03.014 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Schwarz S., Singer M. (2013). Romantic red revisited: red enhances men’s attraction to young, but not menopausal women. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 49 161–164 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.08.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Setchell J. (in press) “Color in competition contexts in non-human animals,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Shi J., Zhang C., Jiang F. (2015). Does red undermine individuals’ intellectual performance? A test in China. Int. J. Psychol. 50 81–84 10.1002/ijop.12076 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sloane P. (1991). Primary Sources, Selected Writings on Color from Aristotle to Albers . New York, NY: Design Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Smajic A., Merritt S., Banister C., Blinebry A. (2014). The red effect, anxiety, and exam performance: a multistudy examination. Teach. Psychol. 41 37–43 10.1177/0098628313514176 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sokolik K., Magee R. G., Ivory J. D. (2014). Red-hot and ice-cold ads: the influence of web ads’ warm and cool colors on click-through ways. J. Interact. Advert. 14 31–37 10.1080/15252019.2014.907757 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Soldat A. S., Sinclair R. C., Mark M. M. (1997). Color as an environmental processing cue: external affective cues can directly affect processing strategy without affecting mood. Soc. Cogn. 15 55–71 10.1521/soco.1997.15.1.55 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorokowski P., Szmajke A. (2007). How does the “red wins: effect work? The role of sportswear colour during sport competitions. Pol. J. Appl. Psychol. 5 71–79. [ Google Scholar ]

- Sorokowski P., Szmajke A., Hamamura T., Jiang F., Sorakowska A. (2014). “Red wins,” “black wins,” “blue loses” effects are in the eye of the beholder, but they are culturally niversal: a cross-cultural analysis of the influence of outfit colours on sports performance. Pol. Psychol. Bull. 45 318–325 10.2478/ppb-2014-0039 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spence C. (in press) “Eating with our eyes,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Spence C., Velasco C., Knoeferle K. (2014). A large sampled study on the influence of the multisensory environment on the wine drinking experience. Flavour 3 8 10.1186/2044-7248-3-8 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Steele K. M. (2014). Failure to replicate the Mehta and Zhu (2009) color-priming effect on anagram solution times. Psychon. B. Rev. 21 771–776 10.3758/s13423-013-0548-3 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Law Smith M. J., Stirrat M. R., Perrett D. I. (2009). Facial skin coloration affects perceived health of human faces. Int. J. Primatol. 30 845–857 10.1007/s10764-009-9380-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., McKeegan A. M. (2010). Lip colour affects perceived sex typicality and attractiveness of human faces. Perception 39 1104–1110 10.1068/p6730 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Oldham F. H., Perrett D. I., Barton R. A. (2012a). Redness enhances perceived aggression, dominance and attractiveness in men’s faces. Evol. Psychol. 10 562–572. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Scott I. M. L., Coetzee V., Pound N., Perrett D. I., Penton-Voak I. S. (2012b). Cross-cultural effects of color, but not morphological masculinity, on perceived attractiveness of men’s faces. Evol. Hum. Behav. 33 260–267 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2011.10.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephen I. D., Perrett D. I. (in press) “Color and face perception,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Stockman A., Brainard D. H. (in press) “Fundamentals of color vision I: processing in the eye,” in Handbook of Color Psychology , eds Elliot A., Fairchild M., Franklin A. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Taillard J., Capelli A., Sagaspe P., Anund A., Akerstadt T. (2012). In-car nocturnal blue light exposure improves motorway driving: a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 7 : e46750 10.1371/journal.pone.0046750 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tan K. W., Stephen I. D. (2012). Colour detection thresholds in faces and colour patches. Perception 42 733–741 10.1068/p7499 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tanaka A., Tokuno Y. (2011). The effect of the color red on avoidance motivation. Soc. Behav. Pers. 39 287–288 10.2224/sbp.2011.39.2.287 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tchernikov I., Fallah M. (2010). A color hierarchy for automatic target selection. PLoS ONE 5 : e9338 10.1371/journal.pone.0009338 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Thorstenson C. A. Functional equivalence of the color red and enacted avoidance behavior? Replication and empirical integration. Soc. Psychol. (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Tracy J. L., Beall A. T. (2014). The impact of weather on women’s tendency to wear red pink when at high risk for conception. PLoS ONE 9 : e88852 10.1371/journal.pone.0088852 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ten Velden F. S., Baas M., Shalvi S., Preenen P. T. Y., De Dreu C. K. W. (2012). In competitive interaction displays of red increase actors’ competitive approach and perceivers’ withdrawal. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol . 48 1205–1208 10.1016/j.jesp.2012.04.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Valdez P., Mehrabian A. (1994). Effects of color on emotions. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 123 394–409 10.1037/0096-3445.123.4.394 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Ittersum K., Wansink B. (2012). Plate size and color suggestability, The Deboeuf Illusion’s bias on serving and eating behavior. J. Consum. Res. 39 215–228 10.1086/662615 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Vandewalle G., Schmidt C., Albouy G., Sterpenich V., Darsaud A., Rauchs G., et al. (2007). Brain responses to violet, blue, and green monochromatic light exposures in humans: prominent role of blue light and the brainstem. PLoS ONE 11 : e1247 10.1371/journal.pone.0001247 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Viola A. U., James L. M., Schlangen L. J. M., Dijk D. J. (2008). Blue-enriched white lightin the workplace improves self-reported alertness, performance and sleep quality. Scan. J. Work Environ. Health 34 297–306 10.5271/sjweh.1268 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Whitfield T. W., Wiltshire T. J. (1990). Color psychology: a critical review. Gen. Soc. Gen. Psychol. 116 385–411. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Yamazaki A. K. (2010). An analysis of background-color effects on the scores of a computer-based English test. KES Part II LNI. 6277 630–636 10.1007/978-3-642-15390-7_65 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Young S. The effect of red on male perceptions of female attractiveness: moderationby baseline attractiveness of female faces. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol . (in press) [ Google Scholar ]

- Yüksel A. (2009). Exterior color and perceived retail crowding: effects on tourists’ shoppingquality inferences and approach behaviors. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tourism 10 233–254 10.1080/15280080903183383 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Zanna M. P., Fazio R. H. (1982). “The attitude behavior relation: Moving toward a third generation of research,” in The Ontario Symposium , Vol. 2 eds Zanna M., Higgins E. T., Herman C. (Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.), 283–301. [ Google Scholar ]

- Zhang T., Han B. (2014). Experience reverses the red effect among Chinese stockbrokers. PLoS ONE 9 : e89193 10.1371/journal.pone.0089193 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- A-Z Publications

Annual Review of Psychology

Volume 74, 2023, review article, open access, the development of color perception and cognition.

- John Maule 1 , Alice E. Skelton 1 , and Anna Franklin 1

- View Affiliations Hide Affiliations Affiliations: The Sussex Colour Group & Baby Lab, School of Psychology, University of Sussex, Falmer, United Kingdom; email: [email protected]

- Vol. 74:87-111 (Volume publication date January 2023) https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-032720-040512

- First published as a Review in Advance on August 16, 2022

- Copyright © 2023 by the author(s). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. See credit lines of images or other third-party material in this article for license information

Color is a pervasive feature of our psychological experience, having a role in many aspects of human mind and behavior such as basic vision, scene perception, object recognition, aesthetics, and communication. Understanding how humans encode, perceive, talk about, and use color has been a major interdisciplinary effort. Here, we present the current state of knowledge on how color perception and cognition develop. We cover the development of various aspects of the psychological experience of color, ranging from low-level color vision to perceptual mechanisms such as color constancy to phenomena such as color naming and color preference. We also identify neurodiversity in the development of color perception and cognition and implications for clinical and educational contexts. We discuss the theoretical implications of the research for understanding mature color perception and cognition, for identifying the principles of perceptual and cognitive development, and for fostering a broader debate in the psychological sciences.

Article metrics loading...

Full text loading...

Literature Cited

- Achenbach TM , Edelbrock CS. 1983 . Manual for the Child: Behavior Checklist and Child Behavior Profile Burlington: Univ. Vt. [Google Scholar]

- Albany-Ward K. 2005 . What do you really know about colour blindness?. Br. J. Sch. Nurs. 10 : 4 123– 24 [Google Scholar]

- Barbur J , Rodriguez-Carmona M. 2015 . Color vision changes in normal aging. Handbook of Color Psychology A Elliot, M Fairchild, A Franklin 180– 96 Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ. Press [Google Scholar]

- Barry J , Mollan S , Burdon M , Jenkins M , Denniston A. 2017 . Development and validation of a questionnaire assessing the quality of life impact of Colour Blindness (CBQoL). BMC Ophthalmol 17 : 1 179 [Google Scholar]

- Birch J. 2012 . Worldwide prevalence of red-green color deficiency. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 29 : 3 313– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Bonnardel V , Pitchford NJ 2006 . Colour categorization in preschoolers. Progress in Colour Studies , Vol. 2 N Pitchford, CP Biggam 121– 38 Amsterdam: John Benjamins [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. 1975 . Qualities of color vision in infancy. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 19 : 3 401– 19 [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH , Kessen W , Weiskopf S. 1976 . The categories of hue in infancy. Science 191 : 4223 201– 2 [Google Scholar]

- Bosten JM , Beer RD , MacLeod DIA. 2015 . What is white?. J. Vis. 15 : 16 5 [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth RG , Dobkins KR. 2009 . Chromatic and luminance contrast sensitivity in fullterm and preterm infants. J. Vis . 9 : 13 15.1– 16 [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth RG , Dobkins KR. 2013 . Effects of prematurity on the development of contrast sensitivity: testing the visual experience hypothesis. Vis. Res. 82 : 31– 41 [Google Scholar]

- Brown AM , Lindsey DT. 2013 . Infant color vision and color preferences: a tribute to Davida Teller. Vis. Neurosci. 30 : 5–6 243– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Changizi MA , Zhang Q , Shimojo S. 2006 . Bare skin, blood and the evolution of primate colour vision. Biol. Lett. 2 : 2 217– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Chien SHL , Bronson-Castain K , Palmer J , Teller DY 2006 . Lightness constancy in 4-month-old infants. Vis. Res. 46 : 13 2139– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Clifford A , Franklin A , Davies IR , Holmes A. 2009 . Electrophysiological markers of categorical perception of color in 7-month old infants. Brain Cogn . 71 : 2 165– 72 [Google Scholar]

- Clifford A , Witzel C , Chapman A , French G , Hodson R et al. 2014 . Memory colour in infancy?. Perception 43 : 151 (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Conway BR , Chatterjee S , Field GD , Horwitz GD , Johnson EN et al. 2010 . Advances in color science: from retina to behavior. J. Neurosci. 30 : 45 14955– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Conway BR , Ratnasingam S , Jara-Ettinger J , Futrell R , Gibson E. 2020 . Communication efficiency of color naming across languages provides a new framework for the evolution of color terms. Cognition 195 : 104086 [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell MB , Pearce B , Loveridge C , Hurlbert AC. 2015 . Performance on the Farnsworth-Munsell 100-hue test is significantly related to nonverbal IQ. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 56 : 5 3171– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Crognale MA. 2002 . Development, maturation, and aging of chromatic visual pathways: VEP results. J. Vis. 2 : 6 438– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Dannemiller JL. 1989 . A test of color constancy in 9-and 20-week-old human infants following simulated illuminant changes. Dev. Psychol. 25 : 2 171– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Dannemiller JL , Hanko SA. 1987 . A test of color constancy in 4-month-old human infants. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 44 : 2 255– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Davies I , Franklin A. 2002 . Categorical similarity may affect colour pop-out in infants after all. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 20 : 2 185– 203 [Google Scholar]

- Davis JT , Robertson E , Lew-Levy S , Neldner K , Kapitany R et al. 2021 . Cultural components of sex differences in color preference. Child Dev . 92 : 4 1574– 89 [Google Scholar]

- Dobkins KR , Bosworth RG , McCleery JP. 2009 . Effects of gestational length, gender, postnatal age, and birth order on visual contrast sensitivity in infants. J. Vis. 9 : 10 19 [Google Scholar]

- Drivonikou GV , Kay P , Regier T , Ivry RB , Gilbert AL et al. 2007 . Further evidence that Whorfian effects are stronger in the right visual field than the left. PNAS 104 : 3 1097– 1102 [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SH , Plunkett K. 2019 . Infants show early comprehension of basic color words. Dev. Psychol. 55 : 2 240– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Forbes SH , Plunkett K. 2020 . Linguistic and cultural variation in early color word learning. Child Dev . 91 : 1 28– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A , Drivonikou GV , Bevis L , Davies IR , Kay P , Regier T. 2008a . Categorical perception of color is lateralized to the right hemisphere in infants, but to the left hemisphere in adults. PNAS 105 : 9 3221– 25 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A , Drivonikou GV , Clifford A , Kay P , Regier T , Davies IR. 2008b . Lateralization of categorical perception of color changes with color term acquisition. PNAS 105 : 47 18221– 25 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A , Pilling M , Davies I. 2005 . The nature of infant color categorization: evidence from eye movements on a target detection task. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 91 : 3 227– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A , Sowden P , Burley R , Notman L , Alder E. 2008c . Color perception in children with autism. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 38 : 10 1837– 47 [Google Scholar]

- Franklin A , Sowden P , Notman L , Gonzalez-Dixon M , West D et al. 2010 . Reduced chromatic discrimination in children with autism spectrum disorders. Dev. Sci. 13 : 1 188– 200 [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T , Yamasaki T , Kamio Y , Hirose S , Tobimatsu S. 2011 . Parvocellular pathway impairment in autism spectrum disorder: evidence from visual evoked potentials. Res. Autism Spectrum Disord. 5 : 1 277– 85 [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR , Rieger J. 2000 . Sensory and cognitive contributions of color to the recognition of natural scenes. Curr. Biol. 10 : 13 805– 8 [Google Scholar]

- Gegenfurtner KR , Wichmann FA , Sharpe LT. 1998 . The contribution of color to visual memory in X-chromosome-linked dichromats. Vis. Res. 38 : 7 1041– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Gibson E , Futrell R , Jara-Ettinger J , Mahowald K , Bergen L et al. 2017 . Color naming across languages reflects color use. PNAS 114 : 40 10785– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert AL , Regier T , Kay P , Ivry RB. 2006 . Whorf hypothesis is supported in the right visual field but not the left. PNAS 103 : 2 489– 94 [Google Scholar]

- Granrud CE. 2006 . Size constancy in infants: 4-month-olds' responses to physical versus retinal image size. J. Exp. Psychol. Hum. Percept. Perform. 32 : 6 1398– 404 [Google Scholar]

- Granrud CE. 2009 . Development of size constancy in children: a test of the metacognitive theory. Atten. Percept. Psychophys . 71 : 3 644– 54 [Google Scholar]

- Granrud CE , Schmechel TT. 2006 . Development of size constancy in children: a test of the proximal mode sensitivity hypothesis. Percept. Psychophys. 68 : 8 1372– 81 [Google Scholar]

- Grassivaro Gallo P , Oliva S , Lantieri P , Viviani F. 2002 . Colour blindness in Italian art high school students. Percept. Motor Skills 95 : 3 830– 34 [Google Scholar]

- Heaton P , Ludlow A , Roberson D. 2008 . When less is more: poor discrimination but good colour memory in autism. Re s. Autism Spectrum Disord . 2 : 1 147– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Hensch TK. 2005 . Critical period mechanisms in developing visual cortex. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 69 : 215– 37 [Google Scholar]

- Houston-Price C , Nakai S 2004 . Distinguishing novelty and familiarity effects in infant preference procedures. Infant Child Dev . Int. J. Res. Pract . 13 : 4 341– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Huebner GM , Shipworth DT , Gauthier S , Witzel C , Raynham P , Chan W 2016 . Saving energy with light? Experimental studies assessing the impact of colour temperature on thermal comfort. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 15 : 45– 57 [Google Scholar]

- Hurlbert AC , Ling Y. 2007 . Biological components of sex differences in color preference. Curr. Biol. 17 : 16 R623– 25 [Google Scholar]

- Imai M , Saji N , Große G , Schulze C , Asano M , Saalbach H 2020 . General mechanisms of color lexicon acquisition: insights from comparison of German and Japanese speaking children. Proceedings of the 42nd Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society S Denison, M Mack, Y Xu, BC Armstrong 3315– 21 Austin, TX: Cogn. Sci. Soc. [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara S , Ishihara M. 2016 . Ishihara's Design Charts for Colour Deficiency of Unlettered Persons Tokyo: Kanehara Trading [Google Scholar]

- Jandó G , Mikó-Baráth E , Markó K , Hollódy K , Török B , Kovacs I. 2012 . Early-onset binocularity in preterm infants reveals experience-dependent visual development in humans. PNAS 109 : 27 11049– 52 [Google Scholar]

- Johnson EK , McQueen JM , Huettig F. 2011 . Toddlers' language-mediated visual search: They need not have the words for it. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 64 : 9 1672– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Jonauskaite D , Abdel-Khalek AM , Abu-Akel A , Al-Rasheed AS , Antonietti JP et al. 2019 . The sun is no fun without rain: Physical environments affect how we feel about yellow across 55 countries. J. Environ. Psychol. 66 : 101350 [Google Scholar]

- Káldy Z , Blaser E. 2009 . How to compare apples and oranges: infants' object identification tested with equally salient shape, luminance, and color changes. Infancy 14 : 2 222– 43 [Google Scholar]

- Káldy Z , Leslie AM. 2003 . Identification of objects in 9-month-old infants: integrating “what” and “where” information. Dev. Sci. 6 : 3 360– 73 [Google Scholar]

- Kay P , Berlin B , Maffi L , Merrifield WR , Cook R. 2009 . The World Color Survey Stanford, CA: CSLI Publ. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S , Al-Haj M , Chen S , Fuller S , Jain U et al. 2014 . Colour vision in ADHD: part 1—testing the retinal dopaminergic hypothesis. Behav. Brain Funct. 10 : 38 [Google Scholar]

- Kimura A , Wada Y , Yang J , Otsuka Y , Dan I et al. 2010 . Infants’ recognition of objects using canonical color. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 105 : 3 256– 63 [Google Scholar]

- Knoblauch K , Vital-Durand F , Barbur JL. 2001 . Variation of chromatic sensitivity across the life span. Vis. Res. 41 : 1 23– 36 [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen EI. 2004 . Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 16 : 8 1412– 25 [Google Scholar]

- Koh HC , Milne E , Dobkins K. 2010 . Contrast sensitivity for motion detection and direction discrimination in adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and their siblings. Neuropsychologia 48 : 14 4046– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Kowalski K , Zimiles H. 2006 . The relation between children's conceptual functioning with color and color term acquisition. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 94 : 4 301– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Krentz UC , Earl RK. 2013 . The baby as beholder: Adults and infants have common preferences for original art. Psychol. Aesthet. Creativity Arts 7 : 2 181– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Laeng B , Brennen T , Elden Å , Paulsen HG , Banerjee A , Lipton R. 2007 . Latitude-of-birth and season-of-birth effects on human color vision in the Arctic. Vis. Res. 47 : 12 1595– 607 [Google Scholar]

- Lillo J , Moreira H , Alvaro L , Davies I 2014 . Use of basic color terms by red-green dichromats: 1. General description. Color Res. Appl. 39 : 4 360– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Lindsey DT , Brown AM. 2021 . Lexical color categories. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 7 : 605– 31 [Google Scholar]

- Ling BY , Dain SJ. 2018 . Development of color vision discrimination during childhood: differences between Blue-Yellow, Red-Green, and achromatic thresholds. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 35 : 4 B35– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y , Hurlbert A. 2011 . Age-dependence of colour preference in the U.K. population. New Directions in Colour Studies CP Biggam, CA Hough, CJ Kay, DR Simmons 347– 60 Amsterdam: John Benjamins [Google Scholar]

- Linhares JM , Nascimento SMC , Foster DH , Amano K. 2004 . Chromatic diversity of natural scenes. Perception 33 : 1 65 [Google Scholar]

- LoBue V , DeLoache JS. 2011 . Pretty in pink: the early development of gender-stereotyped colour preferences. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 29 : 3 656– 67 [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow AK , Heaton P , Hill E , Franklin A 2014 . Color obsessions and phobias in autism spectrum disorders: the case of JG. Neurocase 20 : 3 296– 306 [Google Scholar]

- Luo MR. 2006 . Applying colour science in colour design. Opt. Laser Technol. 38 : 4–6 392– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Mani N , Johnson E , McQueen JM , Huettig F 2013 . How yellow is your banana? Toddlers' language-mediated visual search in referent-present tasks. Dev. Psychol. 49 : 6 1036– 44 [Google Scholar]

- Mashige KP. 2019 . Impact of congenital color vision defect on color-related tasks among schoolchildren in Durban, South Africa. Clin. Optom. 4130 : 11 97– 102 [Google Scholar]

- Maule J , Franklin A. 2019 . Color categorization in infants. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 30 : 163– 68 [Google Scholar]

- Maule J , Stanworth K , Pellicano E , Franklin A. 2017 . Ensemble perception of color in autistic adults. Autism Res 10 : 5 839– 51 [Google Scholar]

- Maule J , Stanworth K , Pellicano E , Franklin A. 2018 . Color afterimages in autistic adults. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 48 : 4 1409– 21 [Google Scholar]

- Maurer D , Werker JF. 2014 . Perceptual narrowing during infancy: a comparison of language and faces. Dev. Psychobiol. 56 : 2 154– 78 [Google Scholar]

- McKyton A , Ben-Zion I , Doron R , Zohary E. 2015 . The limits of shape recognition following late emergence from blindness. Curr. Biol. 25 : 18 2373– 78 [Google Scholar]

- Muris P , Meesters C , van den Berg F. 2003 . The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)–further evidence for its reliability and validity in a community sample of Dutch children and adolescents. Eur. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 12 : 1– 8 [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento SM , Albers AM , Gegenfurtner KR. 2021 . Naturalness and aesthetics of colors—preference for color compositions perceived as natural. Vis. Res. 185 : 98– 110 [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento SM , Linhares JM , Montagner C , João CA , Amano K et al. 2017 . The colors of paintings and viewers’ preferences. Vis. Res. 130 : 76– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Nithiyaananthan PJ , Kaur S , Anne BT , Eliana AN , Mahadir A. 2020 . Behavioural issues among primary schoolchildren with colour vision deficiency. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 19 : 3 37– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Oliva A , Schyns PG. 2000 . Diagnostic colors mediate scene recognition. Cogn. Psychol. 41 : 2 176– 210 [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein P. 2011 . Cinderella Ate My Daughter New York: HarperCollins [Google Scholar]

- Osorio D , Vorobyev M. 1996 . Colour vision as an adaptation to frugivory in primates. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 263 : 1370 593– 99 [Google Scholar]

- Ossenblok P , Reits D , Spekreijse H. 1992 . Analysis of striate activity underlying the pattern onset EP of children. Vis. Res. 32 : 10 1829– 35 [Google Scholar]

- Palmer SE , Schloss KB. 2010 . An ecological valence theory of human color preference. PNAS 107 : 19 8877– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Paramei GV , Oakley B. 2014 . Variation of color discrimination across the life span. J. Opt. Soc. Am. A 31 : 4 A375– 84 [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano E , Burr D. 2012 . When the world becomes “too real”: a Bayesian explanation of autistic perception. Trends Cogn. Sci. 16 : 10 504– 10 [Google Scholar]

- Peña M , Arias D , Dehaene-Lambertz G. 2014 . Gaze following is accelerated in healthy preterm infants. Psychol. Sci. 25 : 10 1884– 92 [Google Scholar]

- Pereverzeva M , Chien SHL , Palmer J , Teller DY. 2002 . Infant photometry: Are mean adult isoluminance values a sufficient approximation to individual infant values?. Vis. Res. 42 : 13 1639– 49 [Google Scholar]

- Peterzell DH , Werner JS , Kaplan PS. 1995 . Individual differences in contrast sensitivity functions: longitudinal study of 4-, 6- and 8-month-old human infants. Vis. Res. 35 : 7 961– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Pitchaimuthu K , Sourav S , Bottari D , Banerjee S , Shareef I , Kekunnaya R , Röder B. 2019 . Color vision in sight recovery individuals. Restor. Neurol. Neurosci. 37 : 6 583– 90 [Google Scholar]

- Pitchford NJ , Mullen KT. 2002 . Is the acquisition of basic-colour terms in young children constrained?. Perception 31 : 11 1349– 70 [Google Scholar]

- Raskin LA , Maital S , Bornstein MH. 1983 . Perceptual categorization of color: a life-span study. Psychol. Res. 45 : 2 135– 45 [Google Scholar]

- Regier T , Kay P , Cook RS. 2005 . Focal colors are universal after all. PNAS 102 : 23 8386– 91 [Google Scholar]

- Rice M. 1980 . Cognition to Language: Categories, Word Meanings, and Training University Park, PA: Univ. Park Press [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M , Franklin A , Knoblauch K. 2018 . A novel method to investigate how dimensions interact to inform perceptual salience in infancy. Infancy 23 : 6 833– 56 [Google Scholar]

- Rogers M , Witzel C , Rhodes P , Franklin A. 2020 . Color constancy and color term knowledge are positively related during early childhood. J. Exp. Child. Psychol. 196 : 104825 [Google Scholar]

- Rubin LR , Lackey WL , Kennedy FA , Stephenson RB. 2009 . Using color and grayscale images to teach histology to color-deficient medical students. Anat. Sci. Educ. 2 : 2 84– 88 [Google Scholar]

- Saji N , Imai M , Asano M. 2020 . Acquisition of the meaning of the word orange requires understanding of the meanings of red, pink, and purple: constructing a lexicon as a connected system. Cogn. Sci. 44 : 1 e12813 [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson LK , Horst JS. 2008 . Confronting complexity: insights from the details of behavior over multiple timescales. Dev. Sci. 11 : 2 209– 15 [Google Scholar]

- Sandhofer CM , Smith LB. 1999 . Learning color words involves learning a system of mappings. Dev. Psychol. 35 : 3 668– 79 [Google Scholar]

- Schloss KB , Lessard L , Racey C , Hurlbert AC. 2018a . Modeling color preference using color space metrics. Vis. Res. 151 : 99– 116 [Google Scholar]

- Schloss KB , Lessard L , Walmsley CS , Foley K. 2018b . Color inference in visual communication: the meaning of colors in recycling. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 3 : 5 [Google Scholar]

- Schloss KB , Poggesi RM , Palmer SE. 2011 . Effects of university affiliation and “school spirit” on color preferences: Berkeley versus Stanford. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 18 : 3 498– 504 [Google Scholar]

- Simmons DR , Robertson AE , McKay LS , Toal E , McAleer P , Pollick FE. 2009 . Vision in autism spectrum disorders. Vis. Res. 49 : 22 2705– 39 [Google Scholar]

- Simoncelli EP , Olshausen BA. 2001 . Natural image statistics and neural representation. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24 : 1193– 216 [Google Scholar]

- Siuda-Krzywicka K , Boros M , Bartolomeo P , Witzel C 2019 . The biological bases of colour categorisation: from goldfish to the human brain. Cortex 118 : 82– 106 [Google Scholar]

- Skelton A , Catchpole G , Abbott J , Bosten J , Franklin A. 2017 . Biological origins of color categorization. PNAS 114 : 21 5545– 50 [Google Scholar]

- Skelton AE , Franklin A. 2020 . Infants look longer at colours that adults like when colours are highly saturated. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 27 : 1 78– 85 [Google Scholar]

- Skelton AE , Franklin A , Bosten J. 2022a . Colour vision is aligned with natural scene statistics at 4-months of age. bioRxiv 494927. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.06.06.494927 [Crossref]

- Skelton AE , MacInnes A , Panda K , Maule J , Bosten J et al. 2021 . Infants look longer at urban scenes than scenes of nature, and chromatic and spatial scene statistics can account for their looking Paper presented at the Lancaster Conference on Infant and Early Child Development Lancaster, UK: Aug 25– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Skelton AE , Maule J , Franklin A. 2022b . Infant color perception: insight into perceptual development. Child Dev. Perspect. 16 : 90– 95 [Google Scholar]

- Smithson HE. 2005 . Sensory, computational and cognitive components of human colour constancy. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 360 : 1458 1329– 46 [Google Scholar]

- Sorokowski P , Sorokowska A , Witzel C. 2014 . Sex differences in color preferences transcend extreme differences in culture and ecology. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 21 : 5 1195– 201 [Google Scholar]

- Spence C. 2015 . On the psychological impact of food colour. Flavour 4 : 21 [Google Scholar]

- Stephen ID , Coetzee V , Law Smith M , Perrett DI 2009 . Skin blood perfusion and oxygenation colour affect perceived human health. PLOS ONE 4 : 4 e5083 [Google Scholar]

- Suero MI , Pérez ÁL , Díaz F , Montanero M , Pardo PJ et al. 2005 . Does Daltonism influence young children's learning?. Learn. Individ. Diff. 15 : 2 89– 98 [Google Scholar]

- Sugita Y. 2004 . Experience in early infancy is indispensable for color perception. Curr. Biol. 14 : 14 1267– 71 [Google Scholar]

- Tagarelli A , Piro A , Tagarelli G , Lantieri PB , Risso D , Olivieri RL. 2004 . Colour blindness in everyday life and car driving. Acta Ophthalmol. Scand. 82 : 436– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Tang T , Álvaro L , Alvarez J , Maule J , Skelton A et al. 2022 . ColourSpot, a novel gamified tablet-based test for accurate diagnosis of color vision deficiency in young children. Behav. Res. Methods 54 : 1148– 60 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C , Clifford A , Franklin A 2013a . Color preferences are not universal. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 142 : 4 1015– 27 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C , Franklin A. 2012 . The relationship between color-object associations and color preference: further investigation of ecological valence theory. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 19 : 2 190– 97 [Google Scholar]

- Taylor C , Schloss K , Palmer SE , Franklin A. 2013b . Color preferences in infants and adults are different. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 20 : 5 916– 22 [Google Scholar]

- Teller DY. 1998 . Spatial and temporal aspects of infant color vision. Vis. Res. 38 : 21 3275– 82 [Google Scholar]

- Teller DY , Peeples DR , Sekel M. 1978 . Discrimination of chromatic from white light by two-month-old human infants. Vis. Res. 18 : 1 41– 48 [Google Scholar]

- Tham DSY , Sowden PT , Grandison A , Franklin A , Lee AKW et al. 2020 . A systematic investigation of conceptual color associations. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149 : 7 1311– 32 [Google Scholar]

- Thomas BAWM , Kaur S , Hairol MI , Ahmad M , Wee LH. 2018 . Behavioural and emotional issues among primary school pupils with congenital colour vision deficiency in the Federal Territory of Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: a case-control study. F1000Research 7 : 1834 [Google Scholar]

- Torrents A , Bofill F , Cardona G. 2011 . Suitability of school textbooks for 5 to 7 year old children with colour vision deficiencies. Learn. Individ. Diff. 21 : 5 607– 12 [Google Scholar]

- Tregillus KE , Isherwood ZJ , Vanston JE , Engel SA , MacLeod DI et al. 2021 . Color compensation in anomalous trichromats assessed with fMRI. Curr. Biol. 31 : 5 936– 42 [Google Scholar]

- Uebel-von Sandersleben H , Albrecht B , Rothenberger A , Fillmer-Heise A , Roessner V et al. 2017 . Revisiting the co-existence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and chronic tic disorder in childhood—the case of colour discrimination, sustained attention and interference control. PLOS ONE 12 : 6 e0178866 [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K , Dobkins K , Barner D. 2013 . Slow mapping: color word learning as a gradual inductive process. Cognition 127 : 3 307– 17 [Google Scholar]

- Wagner K , Jergens J , Barner D. 2018 . Partial color word comprehension precedes production. Lang. Learn. Dev. 14 : 4 241– 61 [Google Scholar]

- Wedge-Roberts RJ. 2021 . Colour constancy: cues, priors and development PhD Thesis Durham Univ. Durham, UK: [Google Scholar]

- Wedge-Roberts RJ , Aston S , Kentridge R , Beierholm U , Nardini M , Olkkonen M. 2022 . Developmental changes in colour constancy in a naturalistic object selection task. Dev. Sci In press. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13306 [Crossref] [Google Scholar]

- Werner JS , Marsh-Armstrong B , Knoblauch K. 2020 . Adaptive changes in color vision from long-term filter usage in anomalous but not normal trichromacy. Curr. Biol. 30 : 15 3011– 15 [Google Scholar]

- Wichmann FA , Sharpe LT , Gegenfurtner KR. 2002 . The contributions of color to recognition memory for natural scenes. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 28 : 3 509– 20 [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox T. 1999 . Object individuation: infants’ use of shape, size, pattern, and color. Cognition 72 : 2 125– 66 [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox T , Chapa C. 2004 . Priming infants to attend to color and pattern information in an individuation task. Cognition 90 : 3 265– 302 [Google Scholar]

- Witzel C , Flack Z , Sanchez-Walker E , Franklin A 2021 . Colour category constancy and the development of colour naming. Vis. Res. 187 : 41– 54 [Google Scholar]