How to write an introduction for a history essay

Every essay needs to begin with an introductory paragraph. It needs to be the first paragraph the marker reads.

While your introduction paragraph might be the first of the paragraphs you write, this is not the only way to do it.

You can choose to write your introduction after you have written the rest of your essay.

This way, you will know what you have argued, and this might make writing the introduction easier.

Either approach is fine. If you do write your introduction first, ensure that you go back and refine it once you have completed your essay.

What is an ‘introduction paragraph’?

An introductory paragraph is a single paragraph at the start of your essay that prepares your reader for the argument you are going to make in your body paragraphs .

It should provide all of the necessary historical information about your topic and clearly state your argument so that by the end of the paragraph, the marker knows how you are going to structure the rest of your essay.

In general, you should never use quotes from sources in your introduction.

Introduction paragraph structure

While your introduction paragraph does not have to be as long as your body paragraphs , it does have a specific purpose, which you must fulfil.

A well-written introduction paragraph has the following four-part structure (summarised by the acronym BHES).

B – Background sentences

H – Hypothesis

E – Elaboration sentences

S - Signpost sentence

Each of these elements are explained in further detail, with examples, below:

1. Background sentences

The first two or three sentences of your introduction should provide a general introduction to the historical topic which your essay is about. This is done so that when you state your hypothesis , your reader understands the specific point you are arguing about.

Background sentences explain the important historical period, dates, people, places, events and concepts that will be mentioned later in your essay. This information should be drawn from your background research .

Example background sentences:

Middle Ages (Year 8 Level)

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15 th and 16 th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges.

WWI (Year 9 Level)

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe.

Civil Rights (Year 10 Level)

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success.

Ancient Rome (Year 11/12 Level)

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times.

2. Hypothesis

Once you have provided historical context for your essay in your background sentences, you need to state your hypothesis .

A hypothesis is a single sentence that clearly states the argument that your essay will be proving in your body paragraphs .

A good hypothesis contains both the argument and the reasons in support of your argument.

Example hypotheses:

Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery.

Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare.

The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders.

Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1 st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state.

3. Elaboration sentences

Once you have stated your argument in your hypothesis , you need to provide particular information about how you’re going to prove your argument.

Your elaboration sentences should be one or two sentences that provide specific details about how you’re going to cover the argument in your three body paragraphs.

You might also briefly summarise two or three of your main points.

Finally, explain any important key words, phrases or concepts that you’ve used in your hypothesis, you’ll need to do this in your elaboration sentences.

Example elaboration sentences:

By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period.

Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined.

The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results.

While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period.

4. Signpost sentence

The final sentence of your introduction should prepare the reader for the topic of your first body paragraph. The main purpose of this sentence is to provide cohesion between your introductory paragraph and you first body paragraph .

Therefore, a signpost sentence indicates where you will begin proving the argument that you set out in your hypothesis and usually states the importance of the first point that you’re about to make.

Example signpost sentences:

The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20 th century.

The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Putting it all together

Once you have written all four parts of the BHES structure, you should have a completed introduction paragraph. In the examples above, we have shown each part separately. Below you will see the completed paragraphs so that you can appreciate what an introduction should look like.

Example introduction paragraphs:

Castles were an important component of Medieval Britain from the time of the Norman conquest in 1066 until they were phased out in the 15th and 16th centuries. Initially introduced as wooden motte and bailey structures on geographical strongpoints, they were rapidly replaced by stone fortresses which incorporated sophisticated defensive designs to improve the defenders’ chances of surviving prolonged sieges. Medieval castles were designed with features that nullified the superior numbers of besieging armies, but were ultimately made obsolete by the development of gunpowder artillery. By the height of the Middle Ages, feudal lords were investing significant sums of money by incorporating concentric walls and guard towers to maximise their defensive potential. These developments were so successful that many medieval armies avoided sieges in the late period. The early development of castles is best understood when examining their military purpose.

The First World War began in 1914 following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. The subsequent declarations of war from most of Europe drew other countries into the conflict, including Australia. The Australian Imperial Force joined the war as part of Britain’s armed forces and were dispatched to locations in the Middle East and Western Europe. Australian soldiers’ opinion of the First World War changed from naïve enthusiasm to pessimistic realism as a result of the harsh realities of modern industrial warfare. Following Britain's official declaration of war on Germany, young Australian men voluntarily enlisted into the army, which was further encouraged by government propaganda about the moral justifications for the conflict. However, following the initial engagements on the Gallipoli peninsula, enthusiasm declined. The naïve attitudes of those who volunteered in 1914 can be clearly seen in the personal letters and diaries that they themselves wrote.

The 1967 Referendum sought to amend the Australian Constitution in order to change the legal standing of the indigenous people in Australia. The fact that 90% of Australians voted in favour of the proposed amendments has been attributed to a series of significant events and people who were dedicated to the referendum’s success. The success of the 1967 Referendum was a direct result of the efforts of First Nations leaders such as Charles Perkins, Faith Bandler and the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders. The political activity of key indigenous figures and the formation of activism organisations focused on indigenous resulted in a wider spread of messages to the general Australian public. The generation of powerful images and speeches has been frequently cited by modern historians as crucial to the referendum results. The significance of these people is evident when examining the lack of political representation the indigenous people experience in the early half of the 20th century.

In the late second century BC, the Roman novus homo Gaius Marius became one of the most influential men in the Roman Republic. Marius gained this authority through his victory in the Jugurthine War, with his defeat of Jugurtha in 106 BC, and his triumph over the invading Germanic tribes in 101 BC, when he crushed the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae (102 BC) and the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae (101 BC). Marius also gained great fame through his election to the consulship seven times. Gaius Marius was the most one of the most significant personalities in the 1st century BC due to his effect on the political, military and social structures of the Roman state. While Marius is best known for his military reforms, it is the subsequent impacts of this reform on the way other Romans approached the attainment of magistracies and how public expectations of military leaders changed that had the longest impacts on the late republican period. The origin of Marius’ later achievements was his military reform in 107 BC, which occurred when he was first elected as consul.

Additional resources

What do you need help with?

Download ready-to-use digital learning resources.

Copyright © History Skills 2014-2024.

Contact via email

Introductions & Conclusions

The introduction and conclusion serve important roles in a history paper. They are not simply perfunctory additions in academic writing, but are critical to your task of making a persuasive argument.

A successful introduction will:

- draw your readers in

- culminate in a thesis statement that clearly states your argument

- orient your readers to the key facts they need to know in order to understand your thesis

- lay out a roadmap for the rest of your paper

A successful conclusion will:

- draw your paper together

- reiterate your argument clearly and forcefully

- leave your readers with a lasting impression of why your argument matters or what it brings to light

How to write an effective introduction:

Often students get slowed down in paper-writing because they are not sure how to write the introduction. Do not feel like you have to write your introduction first simply because it is the first section of your paper. You can always come back to it after you write the body of your essay. Whenever you approach your introduction, think of it as having three key parts:

- The opening line

- The middle “stage-setting” section

- The thesis statement

“In a 4-5 page paper, describe the process of nation-building in one Middle Eastern state. What were the particular goals of nation-building? What kinds of strategies did the state employ? What were the results? Be specific in your analysis, and draw on at least one of the scholars of nationalism that we discussed in class.”

Here is an example of a WEAK introduction for this prompt:

“One of the most important tasks the leader of any country faces is how to build a united and strong nation. This has been especially true in the Middle East, where the country of Jordan offers one example of how states in the region approached nation-building. Founded after World War I by the British, Jordan has since been ruled by members of the Hashemite family. To help them face the difficult challenges of founding a new state, they employed various strategies of nation-building.”

Now, here is a REVISED version of that same introduction:

“Since 1921, when the British first created the mandate of Transjordan and installed Abdullah I as its emir, the Hashemite rulers have faced a dual task in nation-building. First, as foreigners to the region, the Hashemites had to establish their legitimacy as Jordan’s rightful leaders. Second, given the arbitrary boundaries of the new nation, the Hashemites had to establish the legitimacy of Jordan itself, binding together the people now called ‘Jordanians.’ To help them address both challenges, the Hashemite leaders crafted a particular narrative of history, what Anthony Smith calls a ‘nationalist mythology.’ By presenting themselves as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups, they established the authority of their own regime and the authority of the new nation, creating one of the most stable states in the modern Middle East.”

The first draft of the introduction, while a good initial step, is not strong enough to set up a solid, argument-based paper. Here are the key issues:

- This first sentence is too general. From the beginning of your paper, you want to invite your reader into your specific topic, rather than make generalizations that could apply to any nation in any time or place. Students often run into the problem of writing general or vague opening lines, such as, “War has always been one of the greatest tragedies to befall society.” Or, “The Great Depression was one of the most important events in American history.” Avoid statements that are too sweeping or imprecise. Ask yourself if the sentence you have written can apply in any time or place or could apply to any event or person. If the answer is yes, then you need to make your opening line more specific.

- Here is the revised opening line: “Since 1921, when the British first created the mandate of Transjordan and installed Abdullah I as its emir, the Hashemite rulers have faced a dual task in nation-building.”

- This is a stronger opening line because it speaks precisely to the topic at hand. The paper prompt is not asking you to talk about nation-building in general, but nation-building in one specific place.

- This stage-setting section is also too general. Certainly, such background information is critical for the reader to know, but notice that it simply restates much of the information already in the prompt. The question already asks you to pick one example, so your job is not simply to reiterate that information, but to explain what kind of example Jordan presents. You also need to tell your reader why the context you are providing matters.

- Revised stage-setting: “First, as foreigners to the region, the Hashemites had to establish their legitimacy as Jordan’s rightful leaders. Second, given the arbitrary boundaries of the new nation, the Hashemites had to establish the legitimacy of Jordan itself, binding together the people now called ‘Jordanians.’ To help them address both challenges, the Hashemite rulers crafted a particular narrative of history, what Anthony Smith calls a ‘nationalist mythology.’”

- This stage-setting is stronger because it introduces the reader to the problem at hand. Instead of simply saying when and why Jordan was created, the author explains why the manner of Jordan’s creation posed particular challenges to nation-building. It also sets the writer up to address the questions in the prompt, getting at both the purposes of nation-building in Jordan and referencing the scholar of nationalism s/he will be drawing on from class: Anthony Smith.

- This thesis statement restates the prompt rather than answers the question. You need to be specific about what strategies of nation-building Jordan’s leaders used. You also need to assess those strategies, so that you can answer the part of the prompt that asks about the results of nation-building.

- Revised thesis statement: “By presenting themselves as descendants of the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups, they established the authority of their regime and the authority of the new nation, creating one of the most stable states in the modern Middle East.”

- It directly answers the question in the prompt. Even though you will be persuading readers of your argument through the evidence you present in the body of your paper, you want to tell them at the outset exactly what you are arguing.

- It discusses the significance of the argument, saying that Jordan created an especially stable state. This helps you answer the question about the results of Jordan’s nation-building project.

- It offers a roadmap for the rest of the paper. The writer knows how to proceed and the reader knows what to expect. The body of the paper will discuss the Hashemite claims “as descendants from the Prophet Muhammad, as leaders of the Arab Revolt, and as the fathers of Jordan’s different tribal groups.”

If you write your introduction first, be sure to revisit it after you have written your entire essay. Because your paper will evolve as you write, you need to go back and make sure that the introduction still sets up your argument and still fits your organizational structure.

How to write an effective conclusion:

Your conclusion serves two main purposes. First, it reiterates your argument in different language than you used in the thesis and body of your paper. Second, it tells your reader why your argument matters. In your conclusion, you want to take a step back and consider briefly the historical implications or significance of your topic. You will not be introducing new information that requires lengthy analysis, but you will be telling your readers what your paper helps bring to light. Perhaps you can connect your paper to a larger theme you have discussed in class, or perhaps you want to pose a new sort of question that your paper elicits. There is no right or wrong “answer” to this part of the conclusion: you are now the “expert” on your topic, and this is your chance to leave your reader with a lasting impression based on what you have learned.

Here is an example of an effective conclusion for the same essay prompt:

“To speak of the nationalist mythology the Hashemites created, however, is not to say that it has gone uncontested. In the 1950s, the Jordanian National Movement unleashed fierce internal opposition to Hashemite rule, crafting an alternative narrative of history in which the Hashemites were mere puppets to Western powers. Various tribes have also reasserted their role in the region’s past, refusing to play the part of “sons” to Hashemite “fathers.” For the Hashemites, maintaining their mythology depends on the same dialectical process that John R. Gillis identified in his investigation of commemorations: a process of both remembering and forgetting. Their myth remembers their descent from the Prophet, their leadership of the Arab Revolt, and the tribes’ shared Arab and Islamic heritage. It forgets, however, the many different histories that Jordanians champion, histories that the Hashemite mythology has never been able to fully reconcile.”

This is an effective conclusion because it moves from the specific argument addressed in the body of the paper to the question of why that argument matters. The writer rephrases the argument by saying, “Their myth remembers their descent from the Prophet, their leadership of the Arab Revolt, and the tribes’ shared Arab and Islamic heritage.” Then, the writer reflects briefly on the larger implications of the argument, showing how Jordan’s nationalist mythology depended on the suppression of other narratives.

Introduction and Conclusion checklist

When revising your introduction and conclusion, check them against the following guidelines:

Does my introduction:

- draw my readers in?

- culminate in a thesis statement that clearly states my argument?

- orient my readers to the key facts they need to know in order to understand my thesis?

- lay out a roadmap for the rest of my paper?

Does my conclusion:

- draw my paper together?

- reiterate my argument clearly and forcefully?

- leave my readers with a lasting impression of why my argument matters or what it brings to light?

Download as PDF

6265 Bunche Hall Box 951473 University of California, Los Angeles Los Angeles, CA 90095-1473 Phone: (310) 825-4601

Other Resources

- UCLA Library

- Faculty Intranet

- Department Forms

- Office 365 Email

- Remote Help

Campus Resources

- Maps, Directions, Parking

- Academic Calendar

- University of California

- Terms of Use

Social Sciences Division Departments

- Aerospace Studies

- African American Studies

- American Indian Studies

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Asian American Studies

- César E. Chávez Department of Chicana & Chicano Studies

- Communication

- Conservation

- Gender Studies

- Military Science

- Naval Science

- Political Science

How to Write an Introduction For a History Essay Step-by-Step

An introduction of a historical essay acquaints the reader with the topic and how the writer will explain it. It is an important first impression. The introduction is a paragraph long and about five to seven sentences. The parts include the opening sentence, arguments and/or details that will be covered, and a thesis statement (argument of the essay).

What Is A History Essay?

An essay is a short piece of writing that answers a question (“Who are the funniest presidents ”) discusses a subject (“What is Japanese feudalism ”), or addresses a topic (“ Causes and Effects of the Industrial Revolution ”). A historical essay specifically addresses historical matters.

These essays are used to judge a student’s progress in understanding history. They also are used to teach and analyze a student’s ability to write and express their knowledge. A person can know their stuff and still have problems expressing their knowledge.

Skillful communication is an essential tool. When you write your introduction to a historical essay remember that both the information and how you express it are both very important.

Purpose of An Introduction

If a person is formally introduced to you, it is a means of getting acquainted.

An introduction of a historical essay acquaints the reader with the topic and how the writer will explain it. The introduction is a roadmap that lays out the direction you will take in the essay.

This is done by the opening paragraph, which is about five to seven sentences long.

Grab the Reader’s Attention

The introduction of a historical essay should grab the attention of your reader.

It is the first time the reader has to react to your essay. Make sure it is clear, confident, and precise . The introduction should not be generic. It should not be vague.

Do not provide sources in the introduction. You do not want the reader to check them out instead of finishing the introduction. Leave sources to the body of the essay.

When Should You Write The Introduction?

A movie is not filmed straight through. Parts of a movie are filmed separately and later edited together. This is also possible when writing an essay, especially with the ease of computers.

An introduction works off the rest of the essay. If you have already written the whole essay, it can be easier to write an introduction. I often write the blog summary on top last.

Others will find it useful to write the introduction first, perhaps because it provides a helpful outline for the rest of the essay. It is a matter of personal taste and comfort level.

Step-By-Step Instructions

Step one: opening sentence.

The first sentence of your introduction sets the stage and draws the reader in.

The opening sentence should introduce the historical context of the subject matter of your historical essay. Historical context is the political, social, cultural, and economic setting for a particular document, idea, or event. For instance, consider this opening sentence:

The Emancipation Proclamation was an official presidential declaration handed down in the middle of the Civil War declaring slavery was now abolished in areas under Confederate control.

A possible topic of the historical essay is “ The Strengths & Weaknesses of the Emancipation Proclamation .” This opening sentence sets the stage. We are no longer in the current day reading about something in the living room. We are in the middle of the Civil War.

There are various ways to start things off. For instance, you can use a quotation such as President Wilson’s or Winston Churchill’s famous sayings about democracy .

The important thing is to grab the reader’s attention and start the ball rolling. Know your audience. An academic audience expects a more studious approach. And, don’t just start with a catchy sentence that has no value to the rest of the historical essay.

Step Two: Facts/Statistics/Evidence

The next step in writing an introduction is to write a few sentences (three to five) summarizing the argument you will be making. These sentences would provide the facts and arguments that will be expanded upon in the body of the paper. The sentences are basically an outline.

If we continue with the previous subject, the summary section can be like this:

It was a major moral accomplishment to use the abolishment of slavery as a war measure. Meanwhile, it had pragmatic benefits, including as a matter of foreign policy, and harmed the South’s chances to win the war. Nonetheless, the measure was of questionable legality and had the possibility of causing major divisions.

The introduction should be clear and crisp. Try to remove unnecessary content. This is not just about filling a word quota. The introduction should have actual content, not empty calories.

Step Three: Thesis Statement

The finale of the introduction is the thesis statement , the argument being made in the essay. This should be one sentence long. An example would be:

The Emancipation Proclamation was as a whole very successful while having various disadvantages that still made it a risky proposition.

The thesis sentence is very important. It summarizes the core of the essay. The reader is now informed about what you are about to argue. The body of the essay should fill in the details.

In Conclusion About Introductions …

An introduction at a party, date, or in a historical essay is about making a good first impression. The basics are the same. Catch the other person’s attention, provide a snapshot of what you are trying to say, and make the person hungry for more.

The other person often has the obligation to “hear” what you have to say. Take it as an opportunity. And, remember, if you mess up, it will be a lot harder to impress later on.

Teach and Thrive

A Bronx, NY veteran high school social studies teacher who has learned most of what she has learned through trial and error and error and error.... and wants to save others that pain.

RELATED ARTICLES:

How to Write a Conclusion For a History Essay Step-by-Step

A historical essay is a short piece of writing that answers a question or addresses a topic. It shows a student’s historical knowledge and ability to express themselves. The conclusion is a...

The Ultimate Guide to Crafting a Winning Historical Essay Body: Tips and Tricks for Success

A historical essay answers a question or addresses a specific topic. The format is like a sandwich: a body cushioned between the introduction and conclusion paragraphs. Each body paragraph is a...

College of Arts and Sciences

History and American Studies

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- History Resources

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Student Research Grants

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Phi Alpha Theta

Alumni Intros

- Internships

Introduction and Conclusion

INTRODUCTIONS The introduction of a paper must introduce its thesis and not just its topic. Readers will lose some—if not much—of what the paper says if the introduction does not prepare them for what is coming (and tell them what to look for and how to evaluate it).

For example, an introduction that says, “The British army fought in the battle of Saratoga” gives the reader virtually no guidance about the paper’s thesis (i.e., what the paper concludes/argues about the British army at Saratoga).

History papers are not mystery novels. Historians WANT and NEED to give away the ending immediately. Their conclusions—presented in the introduction—help the reader better follow/understand their ideas and interpretations.

In other words, an introduction is a MAP that lays out “the trip the author is going to take [readers] on” and thus “lets readers connect any part of the argument with the overall structure. Readers with such a map seldom get confused or lost.”1

Introductions do four things:

attract the ATTENTION of the reader convince the reader that he/she NEEDS TO READ what the author has to say define the paper’s SPECIFIC TOPIC state and explain the paper’s THESIS Writing the introduction: Consider writing the introduction AFTER finishing your paper. By then, you will know what your paper says. You will have thought it through and provided arguments and supporting evidence; therefore, you will know what the reader needs to know—in brief form—in the introduction. (Always think of your initial introduction as “getting started” and as something that “won’t count.” It is for your eyes only; discard it when you know exactly what your paper says.) A common technique is to turn your conclusion into an introduction. It usually reflects what is in the paper—topic, thesis, arguments, evidence—and can be easily adjusted to be a clear and useful introduction.

Some types of introductions:

Quotation Historical overview (provides introduction to topic AND background so that fewer explanations are needed later in paper) Review of literature or a controversy Statistics or startling evidence Anecdote or illustration Question From general to specific OR specific to general Avoid:

“The purpose of this paper is . . .” OR “This paper is about . . . .” First person (e.g., “I will argue that”) Too many questions Dictionary definitions Length: There is no rule other than to be logical. Short papers require short introductions (e.g., a short paragraph); longer ones may require a page or more to provide all that a reader needs. Longer papers require ELABORATION of the thesis; a sentence is not sufficient to prepare the reader for the many pages of arguments and evidence that follow.

CONCLUSIONS Conclusions are the last thing that readers read; they define readers’ final impression of a paper. A flat, boring conclusion means a flat, boring (or, at least, disappointing) paper.

Conclusions should be a climax, not an anti-climax. They do not just restate what has already been said; they interpret, speculate, and provoke thinking.

Some types of conclusions:

Statement of subject’s significance Call for further research Recommendation or speculation Comparison of part to present Anecdote Quotation Questions (with or without answers) Avoid:

“In conclusion”; “finally”; “thus” Additional or new ideas that introduce a new paper First person Length: Again, there is no rule, although too short conclusions should definitely be avoided. Short conclusions leave the reader on the edge of a cliff with no directions on how to get down.

You are the expert – help your reader pull together and appreciate what he/she has read.

____________________________ 1Howard Becker, Writing for Social Scientists (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986).

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 26, 2024

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

How to Write a History Essay

Last Updated: December 27, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Emily Listmann, MA . Emily Listmann is a private tutor in San Carlos, California. She has worked as a Social Studies Teacher, Curriculum Coordinator, and an SAT Prep Teacher. She received her MA in Education from the Stanford Graduate School of Education in 2014. There are 8 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 243,607 times.

Writing a history essay requires you to include a lot of details and historical information within a given number of words or required pages. It's important to provide all the needed information, but also to present it in a cohesive, intelligent way. Know how to write a history essay that demonstrates your writing skills and your understanding of the material.

Preparing to Write Your Essay

- The key words will often need to be defined at the start of your essay, and will serve as its boundaries. [2] X Research source

- For example, if the question was "To what extent was the First World War a Total War?", the key terms are "First World War", and "Total War".

- Do this before you begin conducting your research to ensure that your reading is closely focussed to the question and you don't waste time.

- Explain: provide an explanation of why something happened or didn't happen.

- Interpret: analyse information within a larger framework to contextualise it.

- Evaluate: present and support a value-judgement.

- Argue: take a clear position on a debate and justify it. [3] X Research source

- Your thesis statement should clearly address the essay prompt and provide supporting arguments. These supporting arguments will become body paragraphs in your essay, where you’ll elaborate and provide concrete evidence. [4] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- Your argument may change or become more nuanced as your write your essay, but having a clear thesis statement which you can refer back to is very helpful.

- For example, your summary could be something like "The First World War was a 'total war' because civilian populations were mobilized both in the battlefield and on the home front".

- Pick out some key quotes that make your argument precisely and persuasively. [5] X Research source

- When writing your plan, you should already be thinking about how your essay will flow, and how each point will connect together.

Doing Your Research

- Primary source material refers to any texts, films, pictures, or any other kind of evidence that was produced in the historical period, or by someone who participated in the events of the period, that you are writing about.

- Secondary material is the work by historians or other writers analysing events in the past. The body of historical work on a period or event is known as the historiography.

- It is not unusual to write a literature review or historiographical essay which does not directly draw on primary material.

- Typically a research essay would need significant primary material.

- Start with the core texts in your reading list or course bibliography. Your teacher will have carefully selected these so you should start there.

- Look in footnotes and bibliographies. When you are reading be sure to pay attention to the footnotes and bibliographies which can guide you to further sources a give you a clear picture of the important texts.

- Use the library. If you have access to a library at your school or college, be sure to make the most of it. Search online catalogues and speak to librarians.

- Access online journal databases. If you are in college it is likely that you will have access to academic journals online. These are an excellent and easy to navigate resources.

- Use online sources with discretion. Try using free scholarly databases, like Google Scholar, which offer quality academic sources, but avoid using the non-trustworthy websites that come up when you simply search your topic online.

- Avoid using crowd-sourced sites like Wikipedia as sources. However, you can look at the sources cited on a Wikipedia page and use them instead, if they seem credible.

- Who is the author? Is it written by an academic with a position at a University? Search for the author online.

- Who is the publisher? Is the book published by an established academic press? Look in the cover to check the publisher, if it is published by a University Press that is a good sign.

- If it's an article, where is published? If you are using an article check that it has been published in an academic journal. [8] X Research source

- If the article is online, what is the URL? Government sources with .gov addresses are good sources, as are .edu sites.

- Ask yourself why the author is making this argument. Evaluate the text by placing it into a broader intellectual context. Is it part of a certain tradition in historiography? Is it a response to a particular idea?

- Consider where there are weaknesses and limitations to the argument. Always keep a critical mindset and try to identify areas where you think the argument is overly stretched or the evidence doesn't match the author's claims. [9] X Research source

- Label all your notes with the page numbers and precise bibliographic information on the source.

- If you have a quote but can't remember where you found it, imagine trying to skip back through everything you have read to find that one line.

- If you use something and don't reference it fully you risk plagiarism. [10] X Research source

Writing the Introduction

- For example you could start by saying "In the First World War new technologies and the mass mobilization of populations meant that the war was not fought solely by standing armies".

- This first sentences introduces the topic of your essay in a broad way which you can start focus to in on more.

- This will lead to an outline of the structure of your essay and your argument.

- Here you will explain the particular approach you have taken to the essay.

- For example, if you are using case studies you should explain this and give a brief overview of which case studies you will be using and why.

Writing the Essay

- Try to include a sentence that concludes each paragraph and links it to the next paragraph.

- When you are organising your essay think of each paragraph as addressing one element of the essay question.

- Keeping a close focus like this will also help you avoid drifting away from the topic of the essay and will encourage you to write in precise and concise prose.

- Don't forget to write in the past tense when referring to something that has already happened.

- Don't drop a quote from a primary source into your prose without introducing it and discussing it, and try to avoid long quotations. Use only the quotes that best illustrate your point.

- If you are referring to a secondary source, you can usually summarise in your own words rather than quoting directly.

- Be sure to fully cite anything you refer to, including if you do not quote it directly.

- Think about the first and last sentence in every paragraph and how they connect to the previous and next paragraph.

- Try to avoid beginning paragraphs with simple phrases that make your essay appear more like a list. For example, limit your use of words like: "Additionally", "Moreover", "Furthermore".

- Give an indication of where your essay is going and how you are building on what you have already said. [15] X Research source

- Briefly outline the implications of your argument and it's significance in relation to the historiography, but avoid grand sweeping statements. [16] X Research source

- A conclusion also provides the opportunity to point to areas beyond the scope of your essay where the research could be developed in the future.

Proofreading and Evaluating Your Essay

- Try to cut down any overly long sentences or run-on sentences. Instead, try to write clear and accurate prose and avoid unnecessary words.

- Concentrate on developing a clear, simple and highly readable prose style first before you think about developing your writing further. [17] X Research source

- Reading your essay out load can help you get a clearer picture of awkward phrasing and overly long sentences. [18] X Research source

- When you read through your essay look at each paragraph and ask yourself, "what point this paragraph is making".

- You might have produced a nice piece of narrative writing, but if you are not directly answering the question it is not going to help your grade.

- A bibliography will typically have primary sources first, followed by secondary sources. [19] X Research source

- Double and triple check that you have included all the necessary references in the text. If you forgot to include a reference you risk being reported for plagiarism.

Sample Essay

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

- ↑ http://www.historytoday.com/robert-pearce/how-write-good-history-essay

- ↑ https://www.hamilton.edu/academics/centers/writing/writing-resources/writing-a-good-history-paper

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/thesis_statement_tips.html

- ↑ http://history.rutgers.edu/component/content/article?id=106:writing-historical-essays-a-guide-for-undergraduates

- ↑ https://guides.lib.uw.edu/c.php?g=344285&p=2580599

- ↑ http://www.hamilton.edu/documents/writing-center/WritingGoodHistoryPaper.pdf

- ↑ http://www.bowdoin.edu/writing-guides/

- ↑ https://www.wgtn.ac.nz/hppi/publications/Writing-History-Essays.pdf

About This Article

To write a history essay, read the essay question carefully and use source materials to research the topic, taking thorough notes as you go. Next, formulate a thesis statement that summarizes your key argument in 1-2 concise sentences and create a structured outline to help you stay on topic. Open with a strong introduction that introduces your thesis, present your argument, and back it up with sourced material. Then, end with a succinct conclusion that restates and summarizes your position! For more tips on creating a thesis statement, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lea Fernandez

Nov 23, 2017

Did this article help you?

Matthew Sayers

Mar 31, 2019

Millie Jenkerinx

Nov 11, 2017

Oct 18, 2019

Shannon Harper

Mar 9, 2018

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Level up your tech skills and stay ahead of the curve

Tips from my first year - essay writing

This is the third of a three part series giving advice on the essay writing process, focusing in this case on essay writing.

Daniel is a first year BA History and Politics student at Magdalen College . He is a disabled student and the first in his immediate family to go to university. Daniel is also a Trustee of Potential Plus UK , a Founding Ambassador and Expert Panel Member for Zero Gravity , and a History Faculty Ambassador. Before coming to university, Daniel studied at a non-selective state school, and was a participant on the UNIQ , Sutton Trust , and Social Mobility Foundation APP Reach programmes, as well as being part of the inaugural Opportunity Oxford cohort. Daniel is passionate about outreach and social mobility and ensuring all students have the best opportunity to succeed.

History and its related disciplines mainly rely on essay writing with most term-time work centring on this, so it’s a good idea to be prepared. The blessing of the Oxford system though is you get plenty of opportunity to practice, and your tutors usually provide lots of feedback (both through comments on essays and in tutorials) to help you improve. Here are my tips from my first year as an Oxford Undergraduate:

- Plan for success – a good plan really sets your essay in a positive direction, so try to collect your thoughts if you can. I find a great way to start my planning process is to go outside for a walk as it helps to clear my head of the detail, it allows me to focus on the key themes, and it allows me to explore ideas without having to commit anything to paper. Do keep in mind your question throughout the reading and notetaking process, though equally look to the wider themes covered so that when you get to planning you are in the right frame of mind.

- Use what works for you – if you try to use a method you aren’t happy with, it won’t work. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t experiment; to the contrary I highly encourage it as it can be good to change up methods and see what really helps you deliver a strong essay. However, don’t feel pressured into using one set method, as long as it is time-efficient and it gets you ready for the next stage of the essay process it is fine!

- Focus on the general ideas – summarise in a sentence what each author argues, see what links there are between authors and subject areas, and possibly group your ideas into core themes or paragraph headers. Choose the single piece of evidence you believe supports each point best.

- Make something revision-ready – try to make something which you can come back to in a few months’ time which makes sense and will really get your head back to when you were preparing for your essay.

- Consider what is most important – no doubt if you spoke about everything covered on the reading list you would have far more words than the average essay word count (which is usually advised around 1,500-2,000 words - it does depend on your tutor.) You have a limited amount of time, focus, and words, so choose what stands out to you as the most important issues for discussion. Focus on the important issues well rather than covering several points in a less-focused manner.

- Make it your voice – your tutors want to hear from you about what you think and what your argument is, not lots of quotes of what others have said. Therefore, when planning and writing consider what your opinion is and make sure to state it. Use authors to support your viewpoint, or to challenge it, but make sure you are doing the talking and driving the analysis. At the same time, avoid slang, and ensure the language you use is easy to digest.

- Make sure you can understand it - don’t feel you have to use big fancy words you don’t understand unless they happen to be relevant subject-specific terminology, and don’t swallow the Thesaurus. If you use a technical term, make sure to provide a definition. You most probably won’t have time to go into it fully, but if it is an important concept hint at the wider historical debate. State where you stand and why briefly you believe what you are stating before focusing on your main points. You need to treat the reader as both an alien from another planet, and a very intelligent person at the same time – make sure your sentences make sense, but equally make sure to pitch it right. As you can possibly tell, it is a fine balancing act so my advice is to read through your essay and ask yourself ‘why’ about every statement or argument you make. If you haven’t answered why, you likely require a little more explanation. Simple writing doesn’t mean a boring or basic argument, it just means every point you make lands and has impact on the reader, supporting them every step of the way.

- Keep introductions and conclusions short – there is no need for massive amounts of setting the scene in the introduction, or an exact repeat of every single thing you have said in the essay appearing in the conclusion. Instead, in the first sentence of your introduction provide a direct answer to the question. If the question is suitable, it is perfectly fine to say yes, no, or it is a little more complicated. Whatever the answer is, it should be simple enough to fit in one reasonable length sentence. The next three sentences should state what each of your three main body paragraphs are going to argue, and then dive straight into it. With your conclusion, pick up what you said about the key points. Suggest how they possibly link, maybe do some comparison between factors and see if you can leave us with a lasting thought which links to the question in your final sentence.

- Say what you are going to say, say it, say it again – this is a general essay structure; an introduction which clearly states your argument; a main body which explains why you believe that argument; and a conclusion which summarises the key points to be drawn from your essay. Keep your messaging clear as it is so important the reader can grasp everything you are trying to say to have maximum impact. This applies in paragraphs as well – each paragraph should in one sentence outline what is to be said, it should then be said, and in the final sentence summarise what you have just argued. Somebody should be able to quickly glance over your essay using the first and last sentences and be able to put together the core points.

- Make sure your main body paragraphs are focused – if you have come across PEE (Point, Evidence, Explain – in my case the acronym I could not avoid at secondary school!) before, then nothing has changed. Make your point in around a sentence, clearly stating your argument. Then use the best single piece of evidence available to support your point, trying to keep that to a sentence or two if you can. The vast majority of your words should be explaining why this is important, and how it supports your argument, or how it links to something else. You don’t need to ‘stack’ examples where you provide multiple instances of the same thing – if you have used one piece of evidence that is enough, you can move on and make a new point. Try to keep everything as short as possible while communicating your core messages, directly responding to the question. You also don’t need to cover every article or book you read, rather pick out the most convincing examples.

- It works, it doesn’t work, it is a little more complicated – this is a structure I developed for writing main body paragraphs, though it is worth noting it may not work for every question. It works; start your paragraph with a piece of evidence that supports your argument fully. It doesn’t work; see if there is an example which seems to contradict your argument, but suggest why you still believe your argument is correct. Then, and only if you can, see if there is an example which possibly doesn’t quite work fully with your argument, and suggest why possibly your argument cannot wholly explain this point or why your argument is incomplete but still has the most explanatory power. See each paragraph as a mini-debate, and ensure different viewpoints have an opportunity to be heard.

- Take your opponents at their best – essays are a form of rational dialogue, interacting with writing on this topic from the past, so if you are going to ‘win’ (or more likely just make a convincing argument as you don’t need to demolish all opposition in sight) then you need to treat your opponents fairly by choosing challenging examples, and by fairly characterising their arguments. It should not be a slinging match of personal insults or using incredibly weak examples, as this will undermine your argument. While I have never attacked historians personally (though you may find in a few readings they do attack each other!), I have sometimes chosen the easier arguments to try to tackle, and it is definitely better to try to include some arguments which are themselves convincing and contradictory to your view.

- Don’t stress about referencing – yes referencing is important, but it shouldn’t take too long. Unless your tutor specifies a method, choose a method which you find simple to use as well as being an efficient method. For example, when referencing books I usually only include the author, book title, and year of publication – the test I always use for referencing is to ask myself if I have enough information to buy the book from a retailer. While this wouldn’t suffice if you were writing for a journal, you aren’t writing for a journal so focus on your argument instead and ensure you are really developing your writing skills.

- Don’t be afraid of the first person – in my Sixth Form I was told not to use ‘I’ as it weakened my argument, however that isn’t the advice I have received at Oxford; in fact I have been encouraged to use it as it forces me to take a side. So if you struggle with making your argument clear, use phrases like ‘I believe’ and ‘I argue’.

I hope this will help as a toolkit to get you started, but my last piece of advice is don’t worry! As you get so much practice at Oxford you get plenty of opportunity to perfect your essay writing skills, so don’t think you need to be amazing at everything straight away. Take your first term to try new methods out and see what works for you – don’t put too much pressure on yourself. Good luck!

How to Write a History Essay with Outline, Tips, Examples and More

Before we get into how to write a history essay, let's first understand what makes one good. Different people might have different ideas, but there are some basic rules that can help you do well in your studies. In this guide, we won't get into any fancy theories. Instead, we'll give you straightforward tips to help you with historical writing. So, if you're ready to sharpen your writing skills, let our history essay writing service explore how to craft an exceptional paper.

What is a History Essay?

A history essay is an academic assignment where we explore and analyze historical events from the past. We dig into historical stories, figures, and ideas to understand their importance and how they've shaped our world today. History essay writing involves researching, thinking critically, and presenting arguments based on evidence.

Moreover, history papers foster the development of writing proficiency and the ability to communicate complex ideas effectively. They also encourage students to engage with primary and secondary sources, enhancing their research skills and deepening their understanding of historical methodology. Students can benefit from utilizing essay writers services when faced with challenging assignments. These services provide expert assistance and guidance, ensuring that your history papers meet academic standards and accurately reflect your understanding of the subject matter.

History Essay Outline

.png)

The outline is there to guide you in organizing your thoughts and arguments in your essay about history. With a clear outline, you can explore and explain historical events better. Here's how to make one:

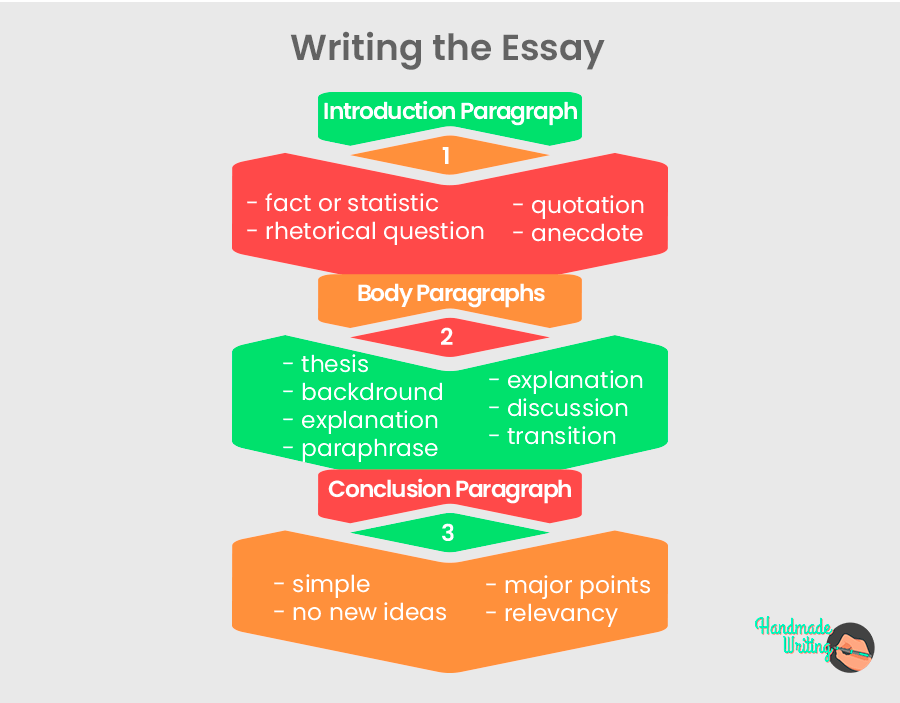

Introduction

- Hook: Start with an attention-grabbing opening sentence or anecdote related to your topic.

- Background Information: Provide context on the historical period, event, or theme you'll be discussing.

- Thesis Statement: Present your main argument or viewpoint, outlining the scope and purpose of your history essay.

Body paragraph 1: Introduction to the Historical Context

- Provide background information on the historical context of your topic.

- Highlight key events, figures, or developments leading up to the main focus of your history essay.

Body paragraphs 2-4 (or more): Main Arguments and Supporting Evidence

- Each paragraph should focus on a specific argument or aspect of your thesis.

- Present evidence from primary and secondary sources to support each argument.

- Analyze the significance of the evidence and its relevance to your history paper thesis.

Counterarguments (optional)

- Address potential counterarguments or alternative perspectives on your topic.

- Refute opposing viewpoints with evidence and logical reasoning.

- Summary of Main Points: Recap the main arguments presented in the body paragraphs.

- Restate Thesis: Reinforce your thesis statement, emphasizing its significance in light of the evidence presented.

- Reflection: Reflect on the broader implications of your arguments for understanding history.

- Closing Thought: End your history paper with a thought-provoking statement that leaves a lasting impression on the reader.

References/bibliography

- List all sources used in your research, formatted according to the citation style required by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include both primary and secondary sources, arranged alphabetically by the author's last name.

Notes (if applicable)

- Include footnotes or endnotes to provide additional explanations, citations, or commentary on specific points within your history essay.

History Essay Format

Adhering to a specific format is crucial for clarity, coherence, and academic integrity. Here are the key components of a typical history essay format:

Font and Size

- Use a legible font such as Times New Roman, Arial, or Calibri.

- The recommended font size is usually 12 points. However, check your instructor's guidelines, as they may specify a different size.

- Set 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Double-space the entire essay, including the title, headings, body paragraphs, and references.

- Avoid extra spacing between paragraphs unless specified otherwise.

- Align text to the left margin; avoid justifying the text or using a centered alignment.

Title Page (if required):

- If your instructor requires a title page, include the essay title, your name, the course title, the instructor's name, and the date.

- Center-align this information vertically and horizontally on the page.

- Include a header on each page (excluding the title page if applicable) with your last name and the page number, flush right.

- Some instructors may require a shortened title in the header, usually in all capital letters.

- Center-align the essay title at the top of the first page (if a title page is not required).

- Use standard capitalization (capitalize the first letter of each major word).

- Avoid underlining, italicizing, or bolding the title unless necessary for emphasis.

Paragraph Indentation:

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches or use the tab key.

- Do not insert extra spaces between paragraphs unless instructed otherwise.

Citations and References:

- Follow the citation style specified by your instructor (e.g., MLA, APA, Chicago).

- Include in-text citations whenever you use information or ideas from external sources.

- Provide a bibliography or list of references at the end of your history essay, formatted according to the citation style guidelines.

- Typically, history essays range from 1000 to 2500 words, but this can vary depending on the assignment.

How to Write a History Essay?

Historical writing can be an exciting journey through time, but it requires careful planning and organization. In this section, we'll break down the process into simple steps to help you craft a compelling and well-structured history paper.

Analyze the Question

Before diving headfirst into writing, take a moment to dissect the essay question. Read it carefully, and then read it again. You want to get to the core of what it's asking. Look out for keywords that indicate what aspects of the topic you need to focus on. If you're unsure about anything, don't hesitate to ask your instructor for clarification. Remember, understanding how to start a history essay is half the battle won!

Now, let's break this step down:

- Read the question carefully and identify keywords or phrases.

- Consider what the question is asking you to do – are you being asked to analyze, compare, contrast, or evaluate?

- Pay attention to any specific instructions or requirements provided in the question.

- Take note of the time period or historical events mentioned in the question – this will give you a clue about the scope of your history essay.

Develop a Strategy

With a clear understanding of the essay question, it's time to map out your approach. Here's how to develop your historical writing strategy:

- Brainstorm ideas : Take a moment to jot down any initial thoughts or ideas that come to mind in response to the history paper question. This can help you generate a list of potential arguments, themes, or points you want to explore in your history essay.

- Create an outline : Once you have a list of ideas, organize them into a logical structure. Start with a clear introduction that introduces your topic and presents your thesis statement – the main argument or point you'll be making in your history essay. Then, outline the key points or arguments you'll be discussing in each paragraph of the body, making sure they relate back to your thesis. Finally, plan a conclusion that summarizes your main points and reinforces your history paper thesis.

- Research : Before diving into writing, gather evidence to support your arguments. Use reputable sources such as books, academic journals, and primary documents to gather historical evidence and examples. Take notes as you research, making sure to record the source of each piece of information for proper citation later on.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate potential counterarguments to your history paper thesis and think about how you'll address them in your essay. Acknowledging opposing viewpoints and refuting them strengthens your argument and demonstrates critical thinking.

- Set realistic goals : Be realistic about the scope of your history essay and the time you have available to complete it. Break down your writing process into manageable tasks, such as researching, drafting, and revising, and set deadlines for each stage to stay on track.

Start Your Research

Now that you've grasped the history essay topic and outlined your approach, it's time to dive into research. Here's how to start:

- Ask questions : What do you need to know? What are the key points to explore further? Write down your inquiries to guide your research.

- Explore diverse sources : Look beyond textbooks. Check academic journals, reliable websites, and primary sources like documents or artifacts.

- Consider perspectives : Think about different viewpoints on your topic. How have historians analyzed it? Are there controversies or differing interpretations?

- Take organized notes : Summarize key points, jot down quotes, and record your thoughts and questions. Stay organized using spreadsheets or note-taking apps.

- Evaluate sources : Consider the credibility and bias of each source. Are they peer-reviewed? Do they represent a particular viewpoint?

Establish a Viewpoint

By establishing a clear viewpoint and supporting arguments, you'll lay the foundation for your compelling historical writing:

- Review your research : Reflect on the information gathered. What patterns or themes emerge? Which perspectives resonate with you?

- Formulate a thesis statement : Based on your research, develop a clear and concise thesis that states your argument or interpretation of the topic.

- Consider counterarguments : Anticipate objections to your history paper thesis. Are there alternative viewpoints or evidence that you need to address?

- Craft supporting arguments : Outline the main points that support your thesis. Use evidence from your research to strengthen your arguments.

- Stay flexible : Be open to adjusting your viewpoint as you continue writing and researching. New information may challenge or refine your initial ideas.

Structure Your Essay

Now that you've delved into the depths of researching historical events and established your viewpoint, it's time to craft the skeleton of your essay: its structure. Think of your history essay outline as constructing a sturdy bridge between your ideas and your reader's understanding. How will you lead them from point A to point Z? Will you follow a chronological path through history or perhaps dissect themes that span across time periods?

And don't forget about the importance of your introduction and conclusion—are they framing your narrative effectively, enticing your audience to read your paper, and leaving them with lingering thoughts long after they've turned the final page? So, as you lay the bricks of your history essay's architecture, ask yourself: How can I best lead my audience through the maze of time and thought, leaving them enlightened and enriched on the other side?

Create an Engaging Introduction

Creating an engaging introduction is crucial for capturing your reader's interest right from the start. But how do you do it? Think about what makes your topic fascinating. Is there a surprising fact or a compelling story you can share? Maybe you could ask a thought-provoking question that gets people thinking. Consider why your topic matters—what lessons can we learn from history?

Also, remember to explain what your history essay will be about and why it's worth reading. What will grab your reader's attention and make them want to learn more? How can you make your essay relevant and intriguing right from the beginning?

Develop Coherent Paragraphs

Once you've established your introduction, the next step is to develop coherent paragraphs that effectively communicate your ideas. Each paragraph should focus on one main point or argument, supported by evidence or examples from your research. Start by introducing the main idea in a topic sentence, then provide supporting details or evidence to reinforce your point.

Make sure to use transition words and phrases to guide your reader smoothly from one idea to the next, creating a logical flow throughout your history essay. Additionally, consider the organization of your paragraphs—is there a clear progression of ideas that builds upon each other? Are your paragraphs unified around a central theme or argument?

Conclude Effectively

Concluding your history essay effectively is just as important as starting it off strong. In your conclusion, you want to wrap up your main points while leaving a lasting impression on your reader. Begin by summarizing the key points you've made throughout your history essay, reminding your reader of the main arguments and insights you've presented.

Then, consider the broader significance of your topic—what implications does it have for our understanding of history or for the world today? You might also want to reflect on any unanswered questions or areas for further exploration. Finally, end with a thought-provoking statement or a call to action that encourages your reader to continue thinking about the topic long after they've finished reading.

Reference Your Sources

Referencing your sources is essential for maintaining the integrity of your history essay and giving credit to the scholars and researchers who have contributed to your understanding of the topic. Depending on the citation style required (such as MLA, APA, or Chicago), you'll need to format your references accordingly. Start by compiling a list of all the sources you've consulted, including books, articles, websites, and any other materials used in your research.

Then, as you write your history essay, make sure to properly cite each source whenever you use information or ideas that are not your own. This includes direct quotations, paraphrases, and summaries. Remember to include all necessary information for each source, such as author names, publication dates, and page numbers, as required by your chosen citation style.

Review and Ask for Advice

As you near the completion of your history essay writing, it's crucial to take a step back and review your work with a critical eye. Reflect on the clarity and coherence of your arguments—are they logically organized and effectively supported by evidence? Consider the strength of your introduction and conclusion—do they effectively capture the reader's attention and leave a lasting impression? Take the time to carefully proofread your history essay for any grammatical errors or typos that may detract from your overall message.

Furthermore, seeking advice from peers, mentors, or instructors can provide valuable insights and help identify areas for improvement. Consider sharing your essay with someone whose feedback you trust and respect, and be open to constructive criticism. Ask specific questions about areas you're unsure about or where you feel your history essay may be lacking. If you need further assistance, don't hesitate to reach out and ask for help. You can even consider utilizing services that offer to write a discussion post for me , where you can engage in meaningful conversations with others about your essay topic and receive additional guidance and support.

History Essay Example

In this section, we offer an example of a history essay examining the impact of the Industrial Revolution on society. This essay demonstrates how historical analysis and critical thinking are applied in academic writing. By exploring this specific event, you can observe how historical evidence is used to build a cohesive argument and draw meaningful conclusions.

FAQs about History Essay Writing

How to write a history essay introduction, how to write a conclusion for a history essay, how to write a good history essay.

- Plagiarism Report

- Unlimited Revisions

- 24/7 Support

How to Write a History Essay?

04 August, 2020

10 minutes read

Author: Tomas White

There are so many types of essays. It can be hard to know where to start. History papers aren’t just limited to history classes. These tasks can be assigned to examine any important historical event or a person. While they’re more common in history classes, you can find this type of assignment in sociology or political science course syllabus, or just get a history essay task for your scholarship. This is Handmadewriting History Essay Guide - let's start!

Purpose of a History Essay

Wondering how to write a history essay? First of all, it helps to understand its purpose. Secondly, this essay aims to examine the influences that lead to a historical event. Thirdly, it can explore the importance of an individual’s impact on history.

However, the goal isn’t to stay in the past. Specifically, a well-written history essay should discuss the relevance of the event or person to the “now”. After finishing this essay, a reader should have a fuller understanding of the lasting impact of an event or individual.

Need basic essay guidance? Find out what is an essay with this 101 essay guide: What is an Essay?

Elements for Success

Indeed, understanding how to write a history essay is crucial in creating a successful paper. Notably, these essays should never only outline successful historic events or list an individual’s achievements. Instead, they should focus on examining questions beginning with what , how , and why . Here’s a pro tip in how to write a history essay: brainstorm questions. Once you’ve got questions, you have an excellent starting point.

Preparing to Write

Evidently, a typical history essay format requires the writer to provide background on the event or person, examine major influences, and discuss the importance of the forces both then and now. In addition, when preparing to write, it’s helpful to organize the information you need to research into questions. For example:

- Who were the major contributors to this event?

- Who opposed or fought against this event?

- Who gained or lost from this event?

- Who benefits from this event today?

- What factors led up to this event?

- What changes occurred because of this event?

- What lasting impacts occurred locally, nationally, globally due to this event?

- What lessons (if any) were learned?

- Why did this event occur?

- Why did certain populations support it?

- Why did certain populations oppose it?

These questions exist as samples. Therefore, generate questions specific to your topic. Once you have a list of questions, it’s time to evaluate them.

Evaluating the Question

Seasoned writers approach writing history by examining the historic event or individual. Specifically, the goal is to assess the impact then and now. Accordingly, the writer needs to evaluate the importance of the main essay guiding the paper. For example, if the essay’s topic is the rise of American prohibition, a proper question may be “How did societal factors influence the rise of American prohibition during the 1920s? ”

This question is open-ended since it allows for insightful analysis, and limits the research to societal factors. Additionally, work to identify key terms in the question. In the example, key terms would be “societal factors” and “prohibition”.

Summarizing the Argument

The argument should answer the question. Use the thesis statement to clarify the argument and outline how you plan to make your case. In other words. the thesis should be sharp, clear, and multi-faceted. Consider the following tips when summarizing the case:

- The thesis should be a single sentence

- It should include a concise argument and a roadmap

- It’s always okay to revise the thesis as the paper develops

- Conduct a bit of research to ensure you have enough support for the ideas within the paper

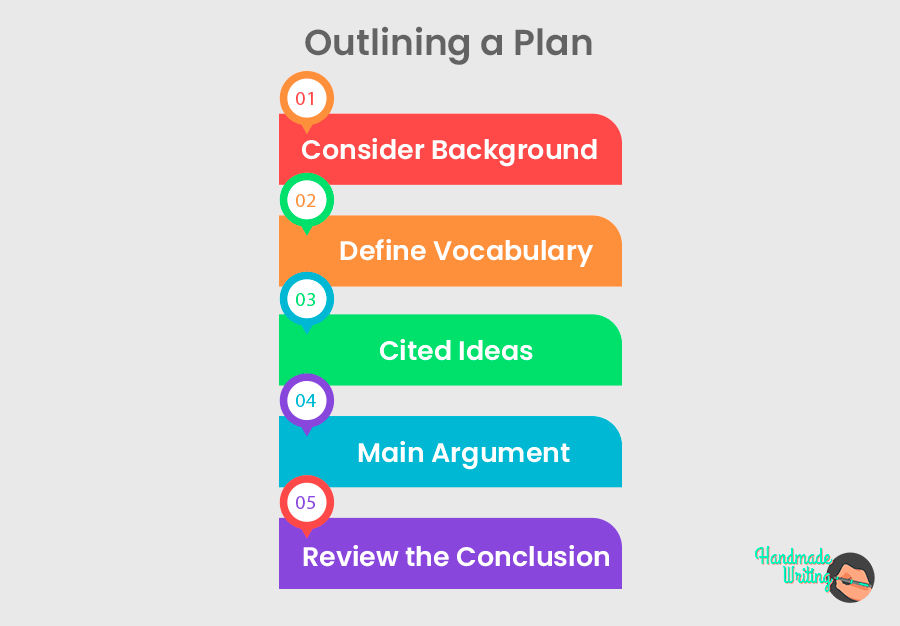

Outlining a History Essay Plan