- Our Mission

Creating Videos to Explore Literary Analysis

Making a short video can be a powerful opportunity for students to explore a reading in a different way from writing an essay.

As an English teacher, one of my first go-to processes when watching a film, even at home for recreation, is digging into the mise-en-scène, or the arrangement of objects and elements onscreen. While considering films this way helps my reader’s brain build analysis, I’m always thinking about steps that help link the processes of reading, writing, and creating. Implementing these steps with my students helps me to know how they think about texts and is also a way for me to learn more about them.

This use of mise-en-scène as a close “reading” step is one way to remind students that everything that appears in a shot for a film or television series (or even TikTok video) is likely there for some purpose. This is true even of still images. By showcasing intentional author and director choices, teachers can activate the writing mind in a variety of ways, which I’ll explain.

Change the Format for Responses to Readings

Rather than write the second or third essay, sometimes I like to let students choose different ways to engage with a reading. This was a practice I used with reading The Catcher in the Rye , in which students responded to the book in groups based on a rubric I shared . When faced with the blank page, sometimes students experience anxiety, but having the opportunity to get up, plan a scene, and talk with peers can help break the ice and inspire thinking processes.

With the design of the rubric, I’m still asking students to create a product that examines the content I’m after, with the additional benefit of the skill building that digital creation allows.

Whether it’s through reenacting a scene somewhere at school or planning a response to sum up thinking about a class reading or concept, film can offer some variety in the ways that students share and present projects. Using film in this way also meets secondary English language arts standards for collaborating and composing using digital and electronic tools—social media apps, YouTube, and laptop cameras. I recommend WeVideo and Adobe tools , which are helpful and specific tools for creating both videos and podcasts.

Students also employ traditional writing methods for scripting what will occur in the videoed exchange. This rough sketch is turned in as part of the process and product . In the past, I’ve also used storyboarding as a method for envisioning written and filmed stories ( Canva has useful resources for this).

Try Zeitgeist Poems

As a reader who appreciates poetry and visual forms, I’m often drawn to the ways that YouTube creators share readings of poems paired with images. In some cases, authors share videos of their own poems. In my class, zeitgeist poems are another Catcher -related activity, resulting in brief, two-to-three-minute recorded responses. This has served as a prereading exercise to think about the idea of a zeitgeist, expanding vocabulary instruction and setting an initial purpose and interest in reading.

The process began with an invitation to write on the page, which then became a multimodal exercise in locating images that paired with and emphasized the words that students chose and arranged to convey the feelings of time, especially related to my students’ experience of the world in 2022. Given their life during the pandemic, there was much to unpack.

As with other video products, students collaborated and explored tools based in social media to create reenactments and do voice-overs for still images. These elements were then combined through the video-editing methods within the platforms the students used. When video is used with the poetic form, imagery is arguably emphasized all the more—an important step for students who may have trouble with visualizing.

Assign Community Video Essays

Finally, I’ve used videos to help students think about poetry and culture, including filmed walk-throughs of projects that they’ve created and written about in response to units of study. Sometimes, students are hesitant to present to a class in real time, but the opportunity to record themselves individually or collaboratively (expanding on learning and presenting about a product they’ve created) can be a more invitational method. This approach also gives students added practice in film editing and media recording techniques that move beyond the slide creation that is common in many of my presentation assignments.

In partnership with fellow teachers, we developed a series of lesson steps that drew upon a unit of study in multicultural literature to help students explore community ideals and engage in problem-solving. This series of lesson steps involved groups deciding how to form a community charter, design their government, and deal with issues that arose within a hypothetical community. Students designed their communities on paper and then used found materials to compose elements of these plans.

Creating physical objects was an engaging exercise in engineering and creativity, giving my students the chance to use spare objects around the classroom space to create three-dimensional blueprints for community models. Students also drafted their initial ideas for the communities on paper and talked through them in small groups with teacher guidance.

The film they created served as a final reflection and presentation step, as students gave guided tours of their communities. They discussed the values that they wanted to emphasize, their decision-making process when faced with issues, and how they redesigned elements of their communities in response to those challenges. I discovered that students who might have shied away from a presentation at the front of the room in traditional speech format were often more comfortable with the take/retake nature of the short film.

Embrace Usefulness, Novelty, and Accessibility

Although I include writing in class daily, it’s sometimes a nice change of pace and a chance for novelty to invite students to film responses, rather than always jotting ideas in the same modes. Additionally, and perhaps more important, utilizing media this way allows me to reach standards and teach aspects of the composing process that would otherwise be difficult to address. As a teacher who is occasionally cast in student-created TikTok videos, I also understand the pull of media and the accessibility that students enjoy for creating short films.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

12.14: Sample Student Literary Analysis Essays

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40514

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

While reading these examples, ask yourself the following questions:

- What is the essay's thesis statement, and how do you know it is the thesis statement?

- What is the main idea or topic sentence of each body paragraph, and how does it relate back to the thesis statement?

- Where and how does each essay use evidence (quotes or paraphrase from the literature)?

- What are some of the literary devices or structures the essays analyze or discuss?

- How does each author structure their conclusion, and how does their conclusion differ from their introduction?

Example 1: Poetry

Victoria Morillo

Instructor Heather Ringo

3 August 2022

How Nguyen’s Structure Solidifies the Impact of Sexual Violence in “The Study”

Stripped of innocence, your body taken from you. No matter how much you try to block out the instance in which these two things occurred, memories surface and come back to haunt you. How does a person, a young boy , cope with an event that forever changes his life? Hieu Minh Nguyen deconstructs this very way in which an act of sexual violence affects a survivor. In his poem, “The Study,” the poem's speaker recounts the year in which his molestation took place, describing how his memory filters in and out. Throughout the poem, Nguyen writes in free verse, permitting a structural liberation to become the foundation for his message to shine through. While he moves the readers with this poignant narrative, Nguyen effectively conveys the resulting internal struggles of feeling alone and unseen.

The speaker recalls his experience with such painful memory through the use of specific punctuation choices. Just by looking at the poem, we see that the first period doesn’t appear until line 14. It finally comes after the speaker reveals to his readers the possible, central purpose for writing this poem: the speaker's molestation. In the first half, the poem makes use of commas, em dashes, and colons, which lends itself to the idea of the speaker stringing along all of these details to make sense of this time in his life. If reading the poem following the conventions of punctuation, a sense of urgency is present here, as well. This is exemplified by the lack of periods to finalize a thought; and instead, Nguyen uses other punctuation marks to connect them. Serving as another connector of thoughts, the two em dashes give emphasis to the role memory plays when the speaker discusses how “no one [had] a face” during that time (Nguyen 9-11). He speaks in this urgent manner until the 14th line, and when he finally gets it off his chest, the pace of the poem changes, as does the more frequent use of the period. This stream-of-consciousness-like section when juxtaposed with the latter half of the poem, causes readers to slow down and pay attention to the details. It also splits the poem in two: a section that talks of the fogginess of memory then transitions into one that remembers it all.

In tandem with the fluctuating nature of memory, the utilization of line breaks and word choice help reflect the damage the molestation has had. Within the first couple of lines of the poem, the poem demands the readers’ attention when the line breaks from “floating” to “dead” as the speaker describes his memory of Little Billy (Nguyen 1-4). This line break averts the readers’ expectation of the direction of the narrative and immediately shifts the tone of the poem. The break also speaks to the effect his trauma has ingrained in him and how “[f]or the longest time,” his only memory of that year revolves around an image of a boy’s death. In a way, the speaker sees himself in Little Billy; or perhaps, he’s representative of the tragic death of his boyhood, how the speaker felt so “dead” after enduring such a traumatic experience, even referring to himself as a “ghost” that he tries to evict from his conscience (Nguyen 24). The feeling that a part of him has died is solidified at the very end of the poem when the speaker describes himself as a nine-year-old boy who’s been “fossilized,” forever changed by this act (Nguyen 29). By choosing words associated with permanence and death, the speaker tries to recreate the atmosphere (for which he felt trapped in) in order for readers to understand the loneliness that came as a result of his trauma. With the assistance of line breaks, more attention is drawn to the speaker's words, intensifying their importance, and demanding to be felt by the readers.

Most importantly, the speaker expresses eloquently, and so heartbreakingly, about the effect sexual violence has on a person. Perhaps what seems to be the most frustrating are the people who fail to believe survivors of these types of crimes. This is evident when he describes “how angry” the tenants were when they filled the pool with cement (Nguyen 4). They seem to represent how people in the speaker's life were dismissive of his assault and who viewed his tragedy as a nuisance of some sorts. This sentiment is bookended when he says, “They say, give us details , so I give them my body. / They say, give us proof , so I give them my body,” (Nguyen 25-26). The repetition of these two lines reinforces the feeling many feel in these scenarios, as they’re often left to deal with trying to make people believe them, or to even see them.

It’s important to recognize how the structure of this poem gives the speaker space to express the pain he’s had to carry for so long. As a characteristic of free verse, the poem doesn’t follow any structured rhyme scheme or meter; which in turn, allows him to not have any constraints in telling his story the way he wants to. The speaker has the freedom to display his experience in a way that evades predictability and engenders authenticity of a story very personal to him. As readers, we abandon anticipating the next rhyme, and instead focus our attention to the other ways, like his punctuation or word choice, in which he effectively tells his story. The speaker recognizes that some part of him no longer belongs to himself, but by writing “The Study,” he shows other survivors that they’re not alone and encourages hope that eventually, they will be freed from the shackles of sexual violence.

Works Cited

Nguyen, Hieu Minh. “The Study” Poets.Org. Academy of American Poets, Coffee House Press, 2018, https://poets.org/poem/study-0 .

Example 2: Fiction

Todd Goodwin

Professor Stan Matyshak

Advanced Expository Writing

Sept. 17, 20—

Poe’s “Usher”: A Mirror of the Fall of the House of Humanity

Right from the outset of the grim story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Edgar Allan Poe enmeshes us in a dark, gloomy, hopeless world, alienating his characters and the reader from any sort of physical or psychological norm where such values as hope and happiness could possibly exist. He fatalistically tells the story of how a man (the narrator) comes from the outside world of hope, religion, and everyday society and tries to bring some kind of redeeming happiness to his boyhood friend, Roderick Usher, who not only has physically and psychologically wasted away but is entrapped in a dilapidated house of ever-looming terror with an emaciated and deranged twin sister. Roderick Usher embodies the wasting away of what once was vibrant and alive, and his house of “insufferable gloom” (273), which contains his morbid sister, seems to mirror or reflect this fear of death and annihilation that he most horribly endures. A close reading of the story reveals that Poe uses mirror images, or reflections, to contribute to the fatalistic theme of “Usher”: each reflection serves to intensify an already prevalent tone of hopelessness, darkness, and fatalism.

It could be argued that the house of Roderick Usher is a “house of mirrors,” whose unpleasant and grim reflections create a dark and hopeless setting. For example, the narrator first approaches “the melancholy house of Usher on a dark and soundless day,” and finds a building which causes him a “sense of insufferable gloom,” which “pervades his spirit and causes an iciness, a sinking, a sickening of the heart, an undiscerned dreariness of thought” (273). The narrator then optimistically states: “I reflected that a mere different arrangement of the scene, of the details of the picture, would be sufficient to modify, or perhaps annihilate its capacity for sorrowful impression” (274). But the narrator then sees the reflection of the house in the tarn and experiences a “shudder even more thrilling than before” (274). Thus the reader begins to realize that the narrator cannot change or stop the impending doom that will befall the house of Usher, and maybe humanity. The story cleverly plays with the word reflection : the narrator sees a physical reflection that leads him to a mental reflection about Usher’s surroundings.

The narrator’s disillusionment by such grim reflection continues in the story. For example, he describes Roderick Usher’s face as distinct with signs of old strength but lost vigor: the remains of what used to be. He describes the house as a once happy and vibrant place, which, like Roderick, lost its vitality. Also, the narrator describes Usher’s hair as growing wild on his rather obtrusive head, which directly mirrors the eerie moss and straw covering the outside of the house. The narrator continually longs to see these bleak reflections as a dream, for he states: “Shaking off from my spirit what must have been a dream, I scanned more narrowly the real aspect of the building” (276). He does not want to face the reality that Usher and his home are doomed to fall, regardless of what he does.

Although there are almost countless examples of these mirror images, two others stand out as important. First, Roderick and his sister, Madeline, are twins. The narrator aptly states just as he and Roderick are entombing Madeline that there is “a striking similitude between brother and sister” (288). Indeed, they are mirror images of each other. Madeline is fading away psychologically and physically, and Roderick is not too far behind! The reflection of “doom” that these two share helps intensify and symbolize the hopelessness of the entire situation; thus, they further develop the fatalistic theme. Second, in the climactic scene where Madeline has been mistakenly entombed alive, there is a pairing of images and sounds as the narrator tries to calm Roderick by reading him a romance story. Events in the story simultaneously unfold with events of the sister escaping her tomb. In the story, the hero breaks out of the coffin. Then, in the story, the dragon’s shriek as he is slain parallels Madeline’s shriek. Finally, the story tells of the clangor of a shield, matched by the sister’s clanging along a metal passageway. As the suspense reaches its climax, Roderick shrieks his last words to his “friend,” the narrator: “Madman! I tell you that she now stands without the door” (296).

Roderick, who slowly falls into insanity, ironically calls the narrator the “Madman.” We are left to reflect on what Poe means by this ironic twist. Poe’s bleak and dark imagery, and his use of mirror reflections, seem only to intensify the hopelessness of “Usher.” We can plausibly conclude that, indeed, the narrator is the “Madman,” for he comes from everyday society, which is a place where hope and faith exist. Poe would probably argue that such a place is opposite to the world of Usher because a world where death is inevitable could not possibly hold such positive values. Therefore, just as Roderick mirrors his sister, the reflection in the tarn mirrors the dilapidation of the house, and the story mirrors the final actions before the death of Usher. “The Fall of the House of Usher” reflects Poe’s view that humanity is hopelessly doomed.

Poe, Edgar Allan. “The Fall of the House of Usher.” 1839. Electronic Text Center, University of Virginia Library . 1995. Web. 1 July 2012. < http://etext.virginia.edu/toc/modeng/public/PoeFall.html >.

Example 3: Poetry

Amy Chisnell

Professor Laura Neary

Writing and Literature

April 17, 20—

Don’t Listen to the Egg!: A Close Reading of Lewis Carroll’s “Jabberwocky”

“You seem very clever at explaining words, Sir,” said Alice. “Would you kindly tell me the meaning of the poem called ‘Jabberwocky’?”

“Let’s hear it,” said Humpty Dumpty. “I can explain all the poems that ever were invented—and a good many that haven’t been invented just yet.” (Carroll 164)

In Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass , Humpty Dumpty confidently translates (to a not so confident Alice) the complicated language of the poem “Jabberwocky.” The words of the poem, though nonsense, aptly tell the story of the slaying of the Jabberwock. Upon finding “Jabberwocky” on a table in the looking-glass room, Alice is confused by the strange words. She is quite certain that “ somebody killed something ,” but she does not understand much more than that. When later she encounters Humpty Dumpty, she seizes the opportunity at having the knowledgeable egg interpret—or translate—the poem. Since Humpty Dumpty professes to be able to “make a word work” for him, he is quick to agree. Thus he acts like a New Critic who interprets the poem by performing a close reading of it. Through Humpty’s interpretation of the first stanza, however, we see the poem’s deeper comment concerning the practice of interpreting poetry and literature in general—that strict analytical translation destroys the beauty of a poem. In fact, Humpty Dumpty commits the “heresy of paraphrase,” for he fails to understand that meaning cannot be separated from the form or structure of the literary work.

Of the 71 words found in “Jabberwocky,” 43 have no known meaning. They are simply nonsense. Yet through this nonsensical language, the poem manages not only to tell a story but also gives the reader a sense of setting and characterization. One feels, rather than concretely knows, that the setting is dark, wooded, and frightening. The characters, such as the Jubjub bird, the Bandersnatch, and the doomed Jabberwock, also appear in the reader’s head, even though they will not be found in the local zoo. Even though most of the words are not real, the reader is able to understand what goes on because he or she is given free license to imagine what the words denote and connote. Simply, the poem’s nonsense words are the meaning.

Therefore, when Humpty interprets “Jabberwocky” for Alice, he is not doing her any favors, for he actually misreads the poem. Although the poem in its original is constructed from nonsense words, by the time Humpty is done interpreting it, it truly does not make any sense. The first stanza of the original poem is as follows:

’Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogroves,

An the mome raths outgrabe. (Carroll 164)

If we replace, however, the nonsense words of “Jabberwocky” with Humpty’s translated words, the effect would be something like this:

’Twas four o’clock in the afternoon, and the lithe and slimy badger-lizard-corkscrew creatures

Did go round and round and make holes in the grass-plot round the sun-dial:

All flimsy and miserable were the shabby-looking birds

with mop feathers,

And the lost green pigs bellowed-sneezed-whistled.

By translating the poem in such a way, Humpty removes the charm or essence—and the beauty, grace, and rhythm—from the poem. The poetry is sacrificed for meaning. Humpty Dumpty commits the heresy of paraphrase. As Cleanth Brooks argues, “The structure of a poem resembles that of a ballet or musical composition. It is a pattern of resolutions and balances and harmonizations” (203). When the poem is left as nonsense, the reader can easily imagine what a “slithy tove” might be, but when Humpty tells us what it is, he takes that imaginative license away from the reader. The beauty (if that is the proper word) of “Jabberwocky” is in not knowing what the words mean, and yet understanding. By translating the poem, Humpty takes that privilege from the reader. In addition, Humpty fails to recognize that meaning cannot be separated from the structure itself: the nonsense poem reflects this literally—it means “nothing” and achieves this meaning by using “nonsense” words.

Furthermore, the nonsense words Carroll chooses to use in “Jabberwocky” have a magical effect upon the reader; the shadowy sound of the words create the atmosphere, which may be described as a trance-like mood. When Alice first reads the poem, she says it seems to fill her head “with ideas.” The strange-sounding words in the original poem do give one ideas. Why is this? Even though the reader has never heard these words before, he or she is instantly aware of the murky, mysterious mood they set. In other words, diction operates not on the denotative level (the dictionary meaning) but on the connotative level (the emotion(s) they evoke). Thus “Jabberwocky” creates a shadowy mood, and the nonsense words are instrumental in creating this mood. Carroll could not have simply used any nonsense words.

For example, let us change the “dark,” “ominous” words of the first stanza to “lighter,” more “comic” words:

’Twas mearly, and the churly pells

Did bimble and ringle in the tink;

All timpy were the brimbledimps,

And the bip plips outlink.

Shifting the sounds of the words from dark to light merely takes a shift in thought. To create a specific mood using nonsense words, one must create new words from old words that convey the desired mood. In “Jabberwocky,” Carroll mixes “slimy,” a grim idea, “lithe,” a pliable image, to get a new adjective: “slithy” (a portmanteau word). In this translation, brighter words were used to get a lighter effect. “Mearly” is a combination of “morning” and “early,” and “ringle” is a blend of “ring” and "dingle.” The point is that “Jabberwocky’s” nonsense words are created specifically to convey this shadowy or mysterious mood and are integral to the “meaning.”

Consequently, Humpty’s rendering of the poem leaves the reader with a completely different feeling than does the original poem, which provided us with a sense of ethereal mystery, of a dark and foreign land with exotic creatures and fantastic settings. The mysteriousness is destroyed by Humpty’s literal paraphrase of the creatures and the setting; by doing so, he has taken the beauty away from the poem in his attempt to understand it. He has committed the heresy of paraphrase: “If we allow ourselves to be misled by it [this heresy], we distort the relation of the poem to its ‘truth’… we split the poem between its ‘form’ and its ‘content’” (Brooks 201). Humpty Dumpty’s ultimate demise might be seen to symbolize the heretical split between form and content: as a literary creation, Humpty Dumpty is an egg, a well-wrought urn of nonsense. His fall from the wall cracks him and separates the contents from the container, and not even all the King’s men can put the scrambled egg back together again!

Through the odd characters of a little girl and a foolish egg, “Jabberwocky” suggests a bit of sage advice about reading poetry, advice that the New Critics built their theories on. The importance lies not solely within strict analytical translation or interpretation, but in the overall effect of the imagery and word choice that evokes a meaning inseparable from those literary devices. As Archibald MacLeish so aptly writes: “A poem should not mean / But be.” Sometimes it takes a little nonsense to show us the sense in something.

Brooks, Cleanth. The Well-Wrought Urn: Studies in the Structure of Poetry . 1942. San Diego: Harcourt Brace, 1956. Print.

Carroll, Lewis. Through the Looking-Glass. Alice in Wonderland . 2nd ed. Ed. Donald J. Gray. New York: Norton, 1992. Print.

MacLeish, Archibald. “Ars Poetica.” The Oxford Book of American Poetry . Ed. David Lehman. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2006. 385–86. Print.

Attribution

- Sample Essay 1 received permission from Victoria Morillo to publish, licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International ( CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 )

- Sample Essays 2 and 3 adapted from Cordell, Ryan and John Pennington. "2.5: Student Sample Papers" from Creating Literary Analysis. 2012. Licensed Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported ( CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 )

beginner's guide to literary analysis

Understanding literature & how to write literary analysis.

Literary analysis is the foundation of every college and high school English class. Once you can comprehend written work and respond to it, the next step is to learn how to think critically and complexly about a work of literature in order to analyze its elements and establish ideas about its meaning.

If that sounds daunting, it shouldn’t. Literary analysis is really just a way of thinking creatively about what you read. The practice takes you beyond the storyline and into the motives behind it.

While an author might have had a specific intention when they wrote their book, there’s still no right or wrong way to analyze a literary text—just your way. You can use literary theories, which act as “lenses” through which you can view a text. Or you can use your own creativity and critical thinking to identify a literary device or pattern in a text and weave that insight into your own argument about the text’s underlying meaning.

Now, if that sounds fun, it should , because it is. Here, we’ll lay the groundwork for performing literary analysis, including when writing analytical essays, to help you read books like a critic.

What Is Literary Analysis?

As the name suggests, literary analysis is an analysis of a work, whether that’s a novel, play, short story, or poem. Any analysis requires breaking the content into its component parts and then examining how those parts operate independently and as a whole. In literary analysis, those parts can be different devices and elements—such as plot, setting, themes, symbols, etcetera—as well as elements of style, like point of view or tone.

When performing analysis, you consider some of these different elements of the text and then form an argument for why the author chose to use them. You can do so while reading and during class discussion, but it’s particularly important when writing essays.

Literary analysis is notably distinct from summary. When you write a summary , you efficiently describe the work’s main ideas or plot points in order to establish an overview of the work. While you might use elements of summary when writing analysis, you should do so minimally. You can reference a plot line to make a point, but it should be done so quickly so you can focus on why that plot line matters . In summary (see what we did there?), a summary focuses on the “ what ” of a text, while analysis turns attention to the “ how ” and “ why .”

While literary analysis can be broad, covering themes across an entire work, it can also be very specific, and sometimes the best analysis is just that. Literary critics have written thousands of words about the meaning of an author’s single word choice; while you might not want to be quite that particular, there’s a lot to be said for digging deep in literary analysis, rather than wide.

Although you’re forming your own argument about the work, it’s not your opinion . You should avoid passing judgment on the piece and instead objectively consider what the author intended, how they went about executing it, and whether or not they were successful in doing so. Literary criticism is similar to literary analysis, but it is different in that it does pass judgement on the work. Criticism can also consider literature more broadly, without focusing on a singular work.

Once you understand what constitutes (and doesn’t constitute) literary analysis, it’s easy to identify it. Here are some examples of literary analysis and its oft-confused counterparts:

Summary: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” the narrator visits his friend Roderick Usher and witnesses his sister escape a horrible fate.

Opinion: In “The Fall of the House of Usher,” Poe uses his great Gothic writing to establish a sense of spookiness that is enjoyable to read.

Literary Analysis: “Throughout ‘The Fall of the House of Usher,’ Poe foreshadows the fate of Madeline by creating a sense of claustrophobia for the reader through symbols, such as in the narrator’s inability to leave and the labyrinthine nature of the house.

In summary, literary analysis is:

- Breaking a work into its components

- Identifying what those components are and how they work in the text

- Developing an understanding of how they work together to achieve a goal

- Not an opinion, but subjective

- Not a summary, though summary can be used in passing

- Best when it deeply, rather than broadly, analyzes a literary element

Literary Analysis and Other Works

As discussed above, literary analysis is often performed upon a single work—but it doesn’t have to be. It can also be performed across works to consider the interplay of two or more texts. Regardless of whether or not the works were written about the same thing, or even within the same time period, they can have an influence on one another or a connection that’s worth exploring. And reading two or more texts side by side can help you to develop insights through comparison and contrast.

For example, Paradise Lost is an epic poem written in the 17th century, based largely on biblical narratives written some 700 years before and which later influenced 19th century poet John Keats. The interplay of works can be obvious, as here, or entirely the inspiration of the analyst. As an example of the latter, you could compare and contrast the writing styles of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Edgar Allan Poe who, while contemporaries in terms of time, were vastly different in their content.

Additionally, literary analysis can be performed between a work and its context. Authors are often speaking to the larger context of their times, be that social, political, religious, economic, or artistic. A valid and interesting form is to compare the author’s context to the work, which is done by identifying and analyzing elements that are used to make an argument about the writer’s time or experience.

For example, you could write an essay about how Hemingway’s struggles with mental health and paranoia influenced his later work, or how his involvement in the Spanish Civil War influenced his early work. One approach focuses more on his personal experience, while the other turns to the context of his times—both are valid.

Why Does Literary Analysis Matter?

Sometimes an author wrote a work of literature strictly for entertainment’s sake, but more often than not, they meant something more. Whether that was a missive on world peace, commentary about femininity, or an allusion to their experience as an only child, the author probably wrote their work for a reason, and understanding that reason—or the many reasons—can actually make reading a lot more meaningful.

Performing literary analysis as a form of study unquestionably makes you a better reader. It’s also likely that it will improve other skills, too, like critical thinking, creativity, debate, and reasoning.

At its grandest and most idealistic, literary analysis even has the ability to make the world a better place. By reading and analyzing works of literature, you are able to more fully comprehend the perspectives of others. Cumulatively, you’ll broaden your own perspectives and contribute more effectively to the things that matter to you.

Literary Terms to Know for Literary Analysis

There are hundreds of literary devices you could consider during your literary analysis, but there are some key tools most writers utilize to achieve their purpose—and therefore you need to know in order to understand that purpose. These common devices include:

- Characters: The people (or entities) who play roles in the work. The protagonist is the main character in the work.

- Conflict: The conflict is the driving force behind the plot, the event that causes action in the narrative, usually on the part of the protagonist

- Context : The broader circumstances surrounding the work political and social climate in which it was written or the experience of the author. It can also refer to internal context, and the details presented by the narrator

- Diction : The word choice used by the narrator or characters

- Genre: A category of literature characterized by agreed upon similarities in the works, such as subject matter and tone

- Imagery : The descriptive or figurative language used to paint a picture in the reader’s mind so they can picture the story’s plot, characters, and setting

- Metaphor: A figure of speech that uses comparison between two unlike objects for dramatic or poetic effect

- Narrator: The person who tells the story. Sometimes they are a character within the story, but sometimes they are omniscient and removed from the plot.

- Plot : The storyline of the work

- Point of view: The perspective taken by the narrator, which skews the perspective of the reader

- Setting : The time and place in which the story takes place. This can include elements like the time period, weather, time of year or day, and social or economic conditions

- Symbol : An object, person, or place that represents an abstract idea that is greater than its literal meaning

- Syntax : The structure of a sentence, either narration or dialogue, and the tone it implies

- Theme : A recurring subject or message within the work, often commentary on larger societal or cultural ideas

- Tone : The feeling, attitude, or mood the text presents

How to Perform Literary Analysis

Step 1: read the text thoroughly.

Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

It’s also important that you don’t skim or speed read. While those are helpful skills, they don’t apply to literary analysis—or at least not this stage.

Step 2: Take Notes as You Read

As you read the work, take notes about different literary elements and devices that stand out to you. Whether you highlight or underline in text, use sticky note tabs to mark pages and passages, or handwrite your thoughts in a notebook, you should capture your thoughts and the parts of the text to which they correspond. This—the act of noticing things about a literary work—is literary analysis.

Step 3: Notice Patterns

As you read the work, you’ll begin to notice patterns in the way the author deploys language, themes, and symbols to build their plot and characters. As you read and these patterns take shape, begin to consider what they could mean and how they might fit together.

As you identify these patterns, as well as other elements that catch your interest, be sure to record them in your notes or text. Some examples include:

- Circle or underline words or terms that you notice the author uses frequently, whether those are nouns (like “eyes” or “road”) or adjectives (like “yellow” or “lush”).

- Highlight phrases that give you the same kind of feeling. For example, if the narrator describes an “overcast sky,” a “dreary morning,” and a “dark, quiet room,” the words aren’t the same, but the feeling they impart and setting they develop are similar.

- Underline quotes or prose that define a character’s personality or their role in the text.

- Use sticky tabs to color code different elements of the text, such as specific settings or a shift in the point of view.

By noting these patterns, comprehensive symbols, metaphors, and ideas will begin to come into focus.

Step 4: Consider the Work as a Whole, and Ask Questions

This is a step that you can do either as you read, or after you finish the text. The point is to begin to identify the aspects of the work that most interest you, and you could therefore analyze in writing or discussion.

Questions you could ask yourself include:

- What aspects of the text do I not understand?

- What parts of the narrative or writing struck me most?

- What patterns did I notice?

- What did the author accomplish really well?

- What did I find lacking?

- Did I notice any contradictions or anything that felt out of place?

- What was the purpose of the minor characters?

- What tone did the author choose, and why?

The answers to these and more questions will lead you to your arguments about the text.

Step 5: Return to Your Notes and the Text for Evidence

As you identify the argument you want to make (especially if you’re preparing for an essay), return to your notes to see if you already have supporting evidence for your argument. That’s why it’s so important to take notes or mark passages as you read—you’ll thank yourself later!

If you’re preparing to write an essay, you’ll use these passages and ideas to bolster your argument—aka, your thesis. There will likely be multiple different passages you can use to strengthen multiple different aspects of your argument. Just be sure to cite the text correctly!

If you’re preparing for class, your notes will also be invaluable. When your teacher or professor leads the conversation in the direction of your ideas or arguments, you’ll be able to not only proffer that idea but back it up with textual evidence. That’s an A+ in class participation.

Step 6: Connect These Ideas Across the Narrative

Whether you’re in class or writing an essay, literary analysis isn’t complete until you’ve considered the way these ideas interact and contribute to the work as a whole. You can find and present evidence, but you still have to explain how those elements work together and make up your argument.

How to Write a Literary Analysis Essay

When conducting literary analysis while reading a text or discussing it in class, you can pivot easily from one argument to another (or even switch sides if a classmate or teacher makes a compelling enough argument).

But when writing literary analysis, your objective is to propose a specific, arguable thesis and convincingly defend it. In order to do so, you need to fortify your argument with evidence from the text (and perhaps secondary sources) and an authoritative tone.

A successful literary analysis essay depends equally on a thoughtful thesis, supportive analysis, and presenting these elements masterfully. We’ll review how to accomplish these objectives below.

Step 1: Read the Text. Maybe Read It Again.

Constructing an astute analytical essay requires a thorough knowledge of the text. As you read, be sure to note any passages, quotes, or ideas that stand out. These could serve as the future foundation of your thesis statement. Noting these sections now will help you when you need to gather evidence.

The more familiar you become with the text, the better (and easier!) your essay will be. Familiarity with the text allows you to speak (or in this case, write) to it confidently. If you only skim the book, your lack of rich understanding will be evident in your essay. Alternatively, if you read the text closely—especially if you read it more than once, or at least carefully revisit important passages—your own writing will be filled with insight that goes beyond a basic understanding of the storyline.

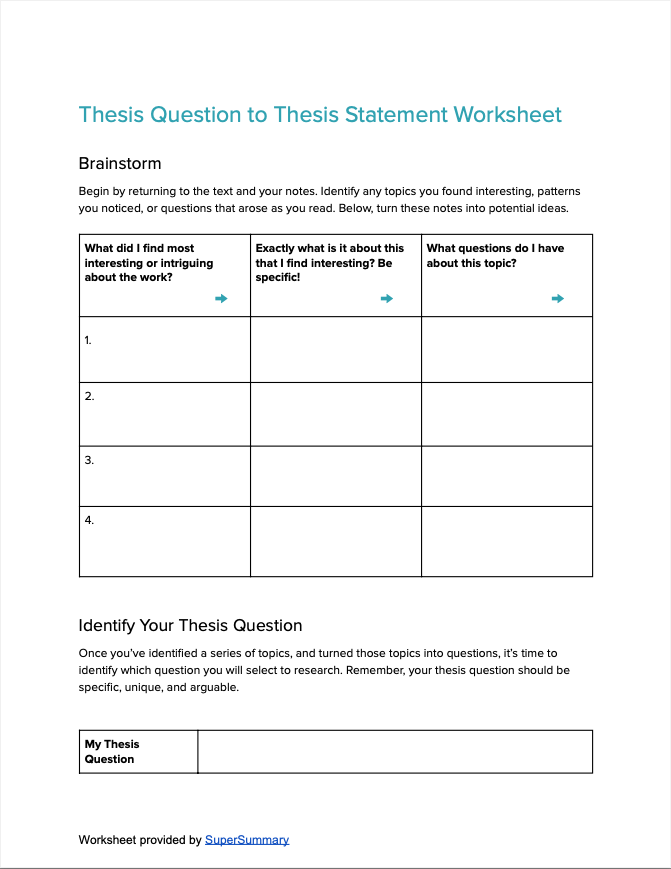

Step 2: Brainstorm Potential Topics

Because you took detailed notes while reading the text, you should have a list of potential topics at the ready. Take time to review your notes, highlighting any ideas or questions you had that feel interesting. You should also return to the text and look for any passages that stand out to you.

When considering potential topics, you should prioritize ideas that you find interesting. It won’t only make the whole process of writing an essay more fun, your enthusiasm for the topic will probably improve the quality of your argument, and maybe even your writing. Just like it’s obvious when a topic interests you in a conversation, it’s obvious when a topic interests the writer of an essay (and even more obvious when it doesn’t).

Your topic ideas should also be specific, unique, and arguable. A good way to think of topics is that they’re the answer to fairly specific questions. As you begin to brainstorm, first think of questions you have about the text. Questions might focus on the plot, such as: Why did the author choose to deviate from the projected storyline? Or why did a character’s role in the narrative shift? Questions might also consider the use of a literary device, such as: Why does the narrator frequently repeat a phrase or comment on a symbol? Or why did the author choose to switch points of view each chapter?

Once you have a thesis question , you can begin brainstorming answers—aka, potential thesis statements . At this point, your answers can be fairly broad. Once you land on a question-statement combination that feels right, you’ll then look for evidence in the text that supports your answer (and helps you define and narrow your thesis statement).

For example, after reading “ The Fall of the House of Usher ,” you might be wondering, Why are Roderick and Madeline twins?, Or even: Why does their relationship feel so creepy?” Maybe you noticed (and noted) that the narrator was surprised to find out they were twins, or perhaps you found that the narrator’s tone tended to shift and become more anxious when discussing the interactions of the twins.

Once you come up with your thesis question, you can identify a broad answer, which will become the basis for your thesis statement. In response to the questions above, your answer might be, “Poe emphasizes the close relationship of Roderick and Madeline to foreshadow that their deaths will be close, too.”

Step 3: Gather Evidence

Once you have your topic (or you’ve narrowed it down to two or three), return to the text (yes, again) to see what evidence you can find to support it. If you’re thinking of writing about the relationship between Roderick and Madeline in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” look for instances where they engaged in the text.

This is when your knowledge of literary devices comes in clutch. Carefully study the language around each event in the text that might be relevant to your topic. How does Poe’s diction or syntax change during the interactions of the siblings? How does the setting reflect or contribute to their relationship? What imagery or symbols appear when Roderick and Madeline are together?

By finding and studying evidence within the text, you’ll strengthen your topic argument—or, just as valuably, discount the topics that aren’t strong enough for analysis.

Step 4: Consider Secondary Sources

In addition to returning to the literary work you’re studying for evidence, you can also consider secondary sources that reference or speak to the work. These can be articles from journals you find on JSTOR, books that consider the work or its context, or articles your teacher shared in class.

While you can use these secondary sources to further support your idea, you should not overuse them. Make sure your topic remains entirely differentiated from that presented in the source.

Step 5: Write a Working Thesis Statement

Once you’ve gathered evidence and narrowed down your topic, you’re ready to refine that topic into a thesis statement. As you continue to outline and write your paper, this thesis statement will likely change slightly, but this initial draft will serve as the foundation of your essay. It’s like your north star: Everything you write in your essay is leading you back to your thesis.

Writing a great thesis statement requires some real finesse. A successful thesis statement is:

- Debatable : You shouldn’t simply summarize or make an obvious statement about the work. Instead, your thesis statement should take a stand on an issue or make a claim that is open to argument. You’ll spend your essay debating—and proving—your argument.

- Demonstrable : You need to be able to prove, through evidence, that your thesis statement is true. That means you have to have passages from the text and correlative analysis ready to convince the reader that you’re right.

- Specific : In most cases, successfully addressing a theme that encompasses a work in its entirety would require a book-length essay. Instead, identify a thesis statement that addresses specific elements of the work, such as a relationship between characters, a repeating symbol, a key setting, or even something really specific like the speaking style of a character.

Example: By depicting the relationship between Roderick and Madeline to be stifling and almost otherworldly in its closeness, Poe foreshadows both Madeline’s fate and Roderick’s inability to choose a different fate for himself.

Step 6: Write an Outline

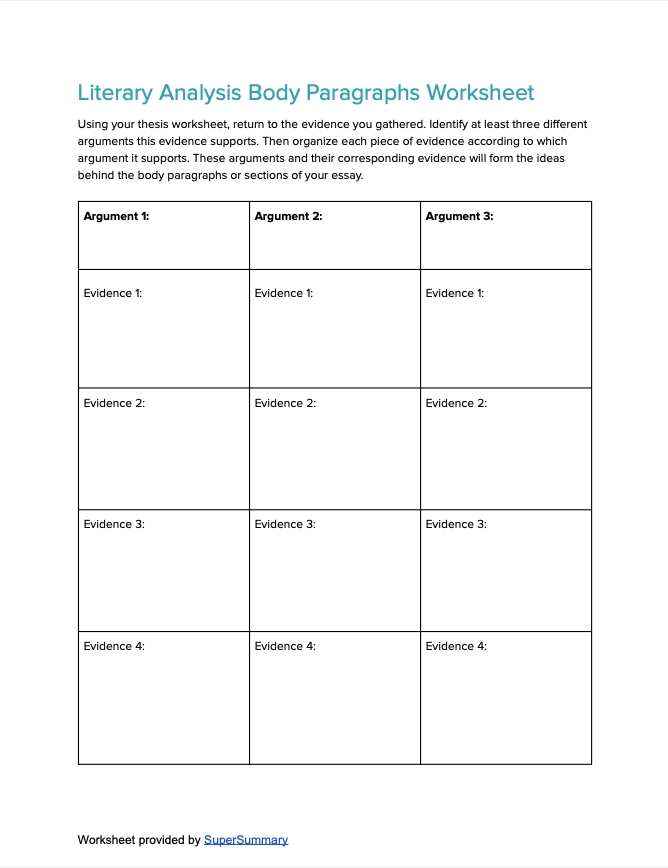

You have your thesis, you have your evidence—but how do you put them together? A great thesis statement (and therefore a great essay) will have multiple arguments supporting it, presenting different kinds of evidence that all contribute to the singular, main idea presented in your thesis.

Review your evidence and identify these different arguments, then organize the evidence into categories based on the argument they support. These ideas and evidence will become the body paragraphs of your essay.

For example, if you were writing about Roderick and Madeline as in the example above, you would pull evidence from the text, such as the narrator’s realization of their relationship as twins; examples where the narrator’s tone of voice shifts when discussing their relationship; imagery, like the sounds Roderick hears as Madeline tries to escape; and Poe’s tendency to use doubles and twins in his other writings to create the same spooky effect. All of these are separate strains of the same argument, and can be clearly organized into sections of an outline.

Step 7: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction serves a few very important purposes that essentially set the scene for the reader:

- Establish context. Sure, your reader has probably read the work. But you still want to remind them of the scene, characters, or elements you’ll be discussing.

- Present your thesis statement. Your thesis statement is the backbone of your analytical paper. You need to present it clearly at the outset so that the reader understands what every argument you make is aimed at.

- Offer a mini-outline. While you don’t want to show all your cards just yet, you do want to preview some of the evidence you’ll be using to support your thesis so that the reader has a roadmap of where they’re going.

Step 8: Write Your Body Paragraphs

Thanks to steps one through seven, you’ve already set yourself up for success. You have clearly outlined arguments and evidence to support them. Now it’s time to translate those into authoritative and confident prose.

When presenting each idea, begin with a topic sentence that encapsulates the argument you’re about to make (sort of like a mini-thesis statement). Then present your evidence and explanations of that evidence that contribute to that argument. Present enough material to prove your point, but don’t feel like you necessarily have to point out every single instance in the text where this element takes place. For example, if you’re highlighting a symbol that repeats throughout the narrative, choose two or three passages where it is used most effectively, rather than trying to squeeze in all ten times it appears.

While you should have clearly defined arguments, the essay should still move logically and fluidly from one argument to the next. Try to avoid choppy paragraphs that feel disjointed; every idea and argument should feel connected to the last, and, as a group, connected to your thesis. A great way to connect the ideas from one paragraph to the next is with transition words and phrases, such as:

- Furthermore

- In addition

- On the other hand

- Conversely

Step 9: Write Your Conclusion

Your conclusion is more than a summary of your essay's parts, but it’s also not a place to present brand new ideas not already discussed in your essay. Instead, your conclusion should return to your thesis (without repeating it verbatim) and point to why this all matters. If writing about the siblings in “The Fall of the House of Usher,” for example, you could point out that the utilization of twins and doubles is a common literary element of Poe’s work that contributes to the definitive eeriness of Gothic literature.

While you might speak to larger ideas in your conclusion, be wary of getting too macro. Your conclusion should still be supported by all of the ideas that preceded it.

Step 10: Revise, Revise, Revise

Of course you should proofread your literary analysis essay before you turn it in. But you should also edit the content to make sure every piece of evidence and every explanation directly supports your thesis as effectively and efficiently as possible.

Sometimes, this might mean actually adapting your thesis a bit to the rest of your essay. At other times, it means removing redundant examples or paraphrasing quotations. Make sure every sentence is valuable, and remove those that aren’t.

Other Resources for Literary Analysis

With these skills and suggestions, you’re well on your way to practicing and writing literary analysis. But if you don’t have a firm grasp on the concepts discussed above—such as literary devices or even the content of the text you’re analyzing—it will still feel difficult to produce insightful analysis.

If you’d like to sharpen the tools in your literature toolbox, there are plenty of other resources to help you do so:

- Check out our expansive library of Literary Devices . These could provide you with a deeper understanding of the basic devices discussed above or introduce you to new concepts sure to impress your professors ( anagnorisis , anyone?).

- This Academic Citation Resource Guide ensures you properly cite any work you reference in your analytical essay.

- Our English Homework Help Guide will point you to dozens of resources that can help you perform analysis, from critical reading strategies to poetry helpers.

- This Grammar Education Resource Guide will direct you to plenty of resources to refine your grammar and writing (definitely important for getting an A+ on that paper).

Of course, you should know the text inside and out before you begin writing your analysis. In order to develop a true understanding of the work, read through its corresponding SuperSummary study guide . Doing so will help you truly comprehend the plot, as well as provide some inspirational ideas for your analysis.

Bell Ringers

5 literary analysis teaching strategies.

If you’ve had a chance to check out my Literary Analysis Writing Unit , then you know I spent months making sure I broke down the complexity of my literary analysis teaching strategies into manageable chunks for students and teachers.

When I first started teaching literary analysis writing, I had almost nothing in terms of resources, so I wanted to make sure you had everything you needed in case you needed to start teaching it tomorrow.

I also want to make sure you teach in a way that eliminates your students writing things like, “I’m going to talk about…” ????

THE WORST. Right?

Here are some quick literary analysis teaching strategies that get results.

These lesson ideas and teaching strategies are some things I have learned while teaching the literary analysis essay for five years in middle school ELA as well as while I was creating my HUGE 25-lesson Literary Analysis Writing Unit .

Let Students Pick Their Literature to Analyze:

If you look at the literary analysis unit, you see that I give teachers and students the option to all read the same short stories OR to give them the option to pick (I still curate a list of texts to choose from for my sanity).

This is because the more buy-in students have, the more quality writing you’re going to get out of them.

My first years of teaching the literary analysis essay, we all read the same stories (and I still recommend that method if you need to do that for your sanity), but if you have the ability and time to let them pick their own text, you will see an immediate return in their writing results.

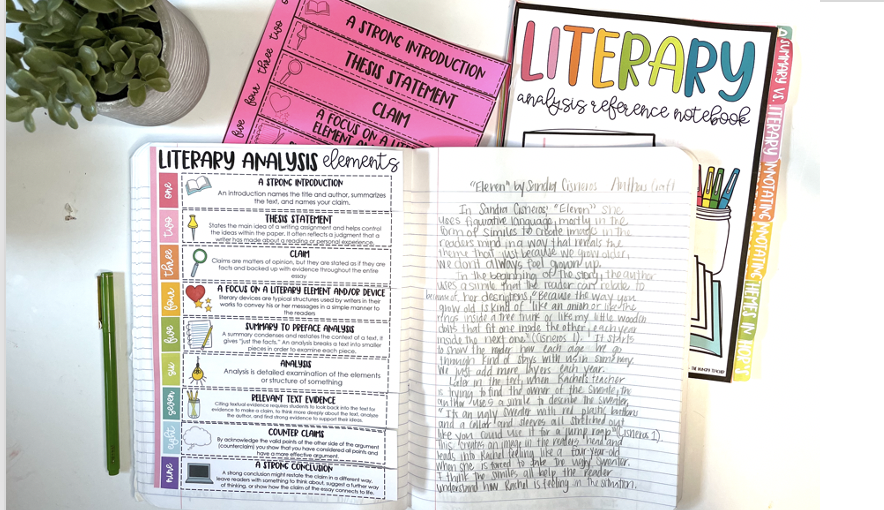

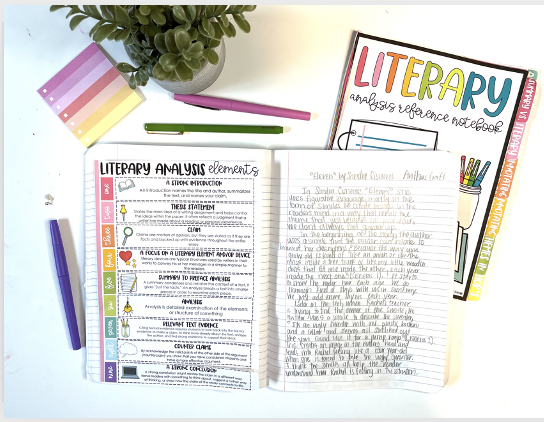

Use My FREE Literary Analysis Reference Booklet

I know I keep talking about this free booklet, but literary analysis is complex, has a lot of steps when broken down, and also has a lot of components students need to include to create a quality final product.

This booklet gives them so many tools to be independent literary analysis essay writers and it’s also a great teacher tool, because you can remind them to check it if they have a question related to its contents!

Model, Model, and Model Some More

I’ve said this before, but I truly believe the reason my students’ ELA proficiency scores increased so drastically in just two short years is because I modeled everything I did right in front of them and/or I created examples of EVERYTHING.

Student’s don’t get stuck on what to write because examples are included.

Let Students Work in Partners

I talk about this in my Literary Analysis Writing Unit , but partner work during essays will change your life.

Ever had a student say:

“I have no idea what the theme is.”

“Where do I find text evidence?”

“I don’t know what to write about.”

Partners will change your classroom forever.

I try to have every student reading the same text as another classmate, but partnerships can work even without the same texts.

Any time students have a question like this, instead of me doing all the heavy lifting, I can simply say, “Why don’t you ask your partner what they wrote?”

They can ask their partner and I can help a lot more students each class period because I am not stuck at the same students’ desk each and every day.

Writing Conferences Made Easy

I believe the best way to do writing conferences is to just do them. By having lots of examples, modeling, and creating partnerships among students ( p.s. all of this is done for you in my Literary Analysis Writing Unit) you have set them up for success when you ask them to write.

This means you now actually have time to individually conference with students.

My best trick for making them quick and not awkward?

Simply go to a student, ask them if you can read their response, read it, and then BOOM! You’ll both have tons to talk and conference about.

If you’re like, okay this all sounds amazing… Just >> CLICK HERE << to check out the full Literary Analysis Writing Unit.

Free Literary Analysis Reference Booklet

If you’re feeling overwhelmed when it comes to teaching literary analysis in middle school ELA, then I’ve got you covered.

This FREE Literary Analysis Booklet has 13 different reference pages for middle school students. They can use them as they do simple responses to reading work or as they navigate their way through complete literary analysis essays.

Each reference pages takes a different element of literary analysis writing and breaks it down into manageable chunks and concepts for students in a way that fosters their independence.

These reference pages support turning your students into analytical readers and writers in no time.

>> CLICK HERE << to snag your FREE Literary Analysis Booklet .

- Read more about: Middle School Reading , Middle School Writing

You might also like...

Reading Conferences: The Golden Gate Bridge Method

Short Story Mentor Texts to Teach Narrative Writing Elements

Using Mentor Texts for Narrative Writing in Middle School ELA

Get your free middle school ela pacing guides with completed scopes and sequences for the school year..

My ELA scope and sequence guides break down every single middle school ELA standard and concept for reading, writing, and language in 6th, 7th, and 8th grade. Use the guides and resources exactly as is or as inspiration for you own!

Meet Martina

I’m a Middle School ELA teacher committed to helping you improve your teaching & implement systems that help you get everything done during the school day!

Let's Connect

Member login.

PRIVACY POLICY

TERMS OF USE

WEBSITE DISCLAIMERS

MEMBERSHIP AGREEEMENT

© The Hungry Teacher • Website by KristenDoyle.co • Contact Martina

Celebrating Secondary

Teaching Literary Analysis in Middle School and High School

November 12, 2020 by Lily Gates

Teaching literary analysis to secondary students can be fun! Both middle school students and high school students can struggle with literary analysis, but an easy way to trick them into analyzing literature is by practicing with short films.

I’ve been using this strategy to teach literary analysis with my struggling readers for years. Using short films to teach literary analysis is a great way to make the process less scary and overwhelming. Using entertaining short films is a way to get students engaged in the literary analysis process.

I use short films to teach so many literary elements such as symbolism, tone, theme, and even social commentary!

Here’s my top 5 favorite short films for teaching literary analysis.

Overview: Lambs tells the story of lamb parents who are a little frustrated and embarrassed that their child isn’t JUST.LIKE.THEM. Through a hilarious learning opportunity, the lamb parents come to realize that conformity shouldn’t be the only option for their child. They decide to embrace their own little lamb’s uniqueness – appreciating him for exactly who he is.

ELA Focus: Use this short film to teach the author’s purpose and social commentary. There’s a definite takeaway here for how important it is to embrace diversity and appreciate your family for who they are – not who we think they should be. During and after viewing, ask students to think about:

- Who is the intended audience for this piece? How do you know?

- What does it mean when a piece is considered a social commentary?

- What makes this short film a social commentary?

Overview: If I’m being honest, this is my all time favorite short film – to watch AND teach! The simple animation packs such a punch! You’ll go from thinking what-in-the-world-is-this? To OMG NO WAY! This short film teaches so many lessons about temptation, choices, and even addiction. I don’t want to give away any spoilers – you just have to watch it to see for yourself what all the hype is about. There’s no dialogue in this film, but every detail from the colors to the sound is beautifully crafted.

ELA Focus : Use this short film to teach symbolism, theme, and author’s purpose. During and after viewing, ask students to think about:

- How does the lack of dialogue enhance the meaning?

- How does color symbolism affect this piece?

- How is the title of the short film symbolic?

3. Snack Attack

Overview: This is such a great short film to use when teaching literary analysis because it requires students to focus on detail and flashbacks! The film tells the story of an elderly woman and a young man who are waiting on the same bus. A misunderstanding causes a disagreement among the two, but there’s a twist at the end that will leave everyone laughing.

ELA Focus: Use this short film to teach flashbacks, characterization, and theme! During and after viewing, ask students to think about:

- What is the filmmaker attempting to teach us about assumptions?

- How do flashbacks enhance the theme?

- What type of characterization is utilized within the film?

Overview: Soar is such a powerful short film about growth mindset. This film tells the story of a young inventor who keeps “failing” at creating different airplane designs. Just when she’s about to give up, a TINY boy and his model airplane fall out of the sky. The young girl has to save the day by developing a design for this tiny boy’s plane so that she can help him catch up with the rest of his fleet/family. Giving up just isn’t an option if she wants to save her new friend!

ELA focus: I use this short film to teach connotation vs. denotation, mood, tone, and symbolism. During and after viewing, ask students to think about:

- Why is the title of this short film a good “fit?”

- What could the stars possibly symbolize?

- What does this short film teach us about mindset?

5. The Small Shoemaker

The Small Shoemaker is set on the beautiful streets of Paris and tells the story of a small business owner who crafts beautiful shoes and is challenged when a strange street vendor comes to town. The shoemaker must learn how to deal with competition, be creative, and find inspiration even in unlikely places.

ELA focus: This is a great short film to not only teach personification, but also mood and characterization. During and after viewing, ask students to think about:

- How do indirect and direct characterization function in the film?

- How does the personification function in this piece to enhance the mood?

- How does the characterization enhance the conflict in this film?

These are just a few of my favorite short films to use when teaching literary analysis or literary elements. You can grab all of the worksheets and organizers I use for teaching these short films here! I also have more great short films to use when teaching literary analysis that you can check out here !

Grab the bundle of all 10 short films + literary analysis graphic organizers here!

What are some of your favorite short films or videos to use when teaching your students how to analyze literature?

celebratingsecondary

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Teaching Literary Analysis in Middle School. My literary analysis resources have basically been seven or eight years in the making. I don't know about you, but when I first realized I needed to be teaching literary analysis to a bunch of twelve and thirteen year-olds, I didn't even know where to begin. I had been teaching upper elementary ...

Theme in Literature. A theme is the main message a reader can learn about life or human nature from a literary piece. From a story you have read in class, identify a theme that the reader may learn from the story. In a well-organized essay, describe this theme.

The body of your essay is everything between the introduction and conclusion. It contains your arguments and the textual evidence that supports them. Paragraph structure. A typical structure for a high school literary analysis essay consists of five paragraphs: the three paragraphs of the body, plus the introduction and conclusion.

Teaching Literary Analysis. Guide students through the five steps of understanding and writing literary analysis: choosing and focusing a topic, gathering, presenting and analyzing textual evidence, and concluding. Literary analysis is a vital stage in the development of students' critical thinking skills.

Literary analysis involves examining all the parts of a novel, play, short story, or poem—elements such as character, setting, tone, and imagery—and thinking about how the author uses those elements to create certain effects. A literary essay isn't a book review: you're not being asked whether or not you liked a book or whether you'd ...

It might seem a little elementary, but when middle school students are starting out with literary analysis, they often need a little hand-holding. Later on, when they have gained some confidence, they can analyze without the sentence stems. 3. Provide examples from your whole-class read-alouds. Every day, I spend at least ten minutes reading a ...

Creating Videos to Explore Literary Analysis. Making a short video can be a powerful opportunity for students to explore a reading in a different way from writing an essay. As an English teacher, one of my first go-to processes when watching a film, even at home for recreation, is digging into the mise-en-scène, or the arrangement of objects ...

Teaching middle school students how to write high-quality literary analysis can be a huge challenge. As I'm sure you've found, oftentimes, students' literary analysis barely scratches the surface and sounds more like a summary than an analysis. While it can be tough to get students to go deep and move beyond the surface, I promise you it ...

Teaching Effective Literary Analysis Essays. Just a few days ago I was blogging about how I literally Googled, "How do you teach effective literary analysis essays?". And although middle school ELA teachers across the nation are expected to teach 12, 13, and 14 year olds how to analyze a piece of literature in the form of an essay, there ...

These 4 steps will help prepare you to write an in-depth literary analysis that offers new insight to both old and modern classics. 1. Read the text and identify literary devices. As you conduct your literary analysis, you should first read through the text, keeping an eye on key elements that could serve as clues to larger, underlying themes.

The term regularly used for the development of the central idea of a literary analysis essay is the body. In this section you present the paragraphs (at least 3 paragraphs for a 500-750 word essay) that support your thesis statement. Good literary analysis essays contain an explanation of your ideas and evidence from the text (short story,

Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap. City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative. Table of contents. Example 1: Poetry. Example 2: Fiction. Example 3: Poetry. Attribution. The following examples are essays where student writers focused on close-reading a literary work.

Get a sense of what to do right with this literary analysis essay example that will offer inspiration for your own assignment. ... At the middle school level, a literary analysis essay can be as short as one page. For high schoolers, the essay may become much longer as they progress.

Literary analysis for middle-grade students (grades 5-8) Goals: 1. Encourage student to begin to think about why literature works through conversation about discussion questions. 2. Teach student to write short essays as answers to these questions. 3. Preserve the student's love of reading.

Step 1: Read the Text Thoroughly. Literary analysis begins with the literature itself, which means performing a close reading of the text. As you read, you should focus on the work. That means putting away distractions (sorry, smartphone) and dedicating a period of time to the task at hand.

This FREE Literary Analysis Booklet has 13 different reference pages for middle school students. They can use them as they do simple responses to reading work or as they navigate their way through complete literary analysis essays. Each reference pages takes a different element of literary analysis writing and breaks it down into manageable ...

Here's my top 5 favorite short films for teaching literary analysis. Lambs. Overview: Lambs tells the story of lamb parents who are a little frustrated and embarrassed that their child isn't JUST.LIKE.THEM. Through a hilarious learning opportunity, the lamb parents come to realize that conformity shouldn't be the only option for their child.

Keep reading for TEN tips that will help with scaffolding literary analysis. Give a PRE- and post-ASSESSMENT. Students are motivated when they can see their growth. Giving them a pre-assessment that is similar to the post-assessment is one way to provide that perspective. An authentic literary analysis assignment usually involves writing an ...

A complete unit plan. Includes pacing, content, step-by-step teacher instructions, and solid class period structures. Strategies and frameworks for scaffolding and differentiating your instruction so all students are successful and increase their writing independence. Specific strategies to teach your students to dig deeper into their analysis.

Ideas- The main idea, supporting details, evidence, and explanation. Ideas are the heart of any good paper. This is where you get the argument, the main idea, or the details that really bring the paper to life. Ideas should be the first thing discussed and brainstormed in the writing process.

Teaching all the Middle School ELA for 6th, 7th, and 8th grade Literature, Informational, Grammar, and Writing standards is completely broken down and done for you with this complete ELA curriculum bundle of units. This bundle includes all of my literary devices units, my nonfiction unit, all of my. 70. Products. $499.99 $997.00 Save $497.01.

Below each prompt title is the number of sources. Zeros denote prompts that are not research or source dependent. Zeros also indicate when the number of sources is unknown or unspecified (i.e., recommends