- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

World War I

By: History.com Editors

Updated: May 10, 2024 | Original: October 29, 2009

World War I, also known as the Great War, started in 1914 after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria. His murder catapulted into a war across Europe that lasted until 1918. During the four-year conflict, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire (the Central Powers) fought against Great Britain, France, Russia, Italy, Romania, Canada, Japan and the United States (the Allied Powers). Thanks to new military technologies and the horrors of trench warfare, World War I saw unprecedented levels of carnage and destruction. By the time the war was over and the Allied Powers had won, more than 16 million people—soldiers and civilians alike—were dead.

Archduke Franz Ferdinand

Tensions had been brewing throughout Europe—especially in the troubled Balkan region of southeast Europe—for years before World War I actually broke out.

A number of alliances involving European powers, the Ottoman Empire , Russia and other parties had existed for years, but political instability in the Balkans (particularly Bosnia, Serbia and Herzegovina) threatened to destroy these agreements.

The spark that ignited World War I was struck in Sarajevo, Bosnia, where Archduke Franz Ferdinand —heir to the Austro-Hungarian Empire—was shot to death along with his wife, Sophie, by the Serbian nationalist Gavrilo Princip on June 28, 1914. Princip and other nationalists were struggling to end Austro-Hungarian rule over Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The Great War

The two-night event The Great War begins Monday, May 27 at 8/7c and streams the next day.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand set off a rapidly escalating chain of events: Austria-Hungary , like many countries around the world, blamed the Serbian government for the attack and hoped to use the incident as justification for settling the question of Serbian nationalism once and for all.

Kaiser Wilhelm II

Because mighty Russia supported Serbia, Austria-Hungary waited to declare war until its leaders received assurance from German leader Kaiser Wilhelm II that Germany would support their cause. Austro-Hungarian leaders feared that a Russian intervention would involve Russia’s ally, France, and possibly Great Britain as well.

On July 5, Kaiser Wilhelm secretly pledged his support, giving Austria-Hungary a so-called carte blanche, or “blank check” assurance of Germany’s backing in the case of war. The Dual Monarchy of Austria-Hungary then sent an ultimatum to Serbia, with such harsh terms as to make it almost impossible to accept.

World War I Begins

Convinced that Austria-Hungary was readying for war, the Serbian government ordered the Serbian army to mobilize and appealed to Russia for assistance. On July 28, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, and the tenuous peace between Europe’s great powers quickly collapsed.

Within a week, Russia, Belgium, France, Great Britain and Serbia had lined up against Austria-Hungary and Germany, and World War I had begun.

The Western Front

According to an aggressive military strategy known as the Schlieffen Plan (named for its mastermind, German Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen ), Germany began fighting World War I on two fronts, invading France through neutral Belgium in the west and confronting Russia in the east.

On August 4, 1914, German troops crossed the border into Belgium. In the first battle of World War I, the Germans assaulted the heavily fortified city of Liege , using the most powerful weapons in their arsenal—enormous siege cannons—to capture the city by August 15. The Germans left death and destruction in their wake as they advanced through Belgium toward France, shooting civilians and executing a Belgian priest they had accused of inciting civilian resistance.

First Battle of the Marne

In the First Battle of the Marne , fought from September 6-9, 1914, French and British forces confronted the invading German army, which had by then penetrated deep into northeastern France, within 30 miles of Paris. The Allied troops checked the German advance and mounted a successful counterattack, driving the Germans back to the north of the Aisne River.

The defeat meant the end of German plans for a quick victory in France. Both sides dug into trenches , and the Western Front was the setting for a hellish war of attrition that would last more than three years.

Particularly long and costly battles in this campaign were fought at Verdun (February-December 1916) and the Battle of the Somme (July-November 1916). German and French troops suffered close to a million casualties in the Battle of Verdun alone.

HISTORY Vault: World War I Documentaries

Stream World War I videos commercial-free in HISTORY Vault.

World War I Books and Art

The bloodshed on the battlefields of the Western Front, and the difficulties its soldiers had for years after the fighting had ended, inspired such works of art as “ All Quiet on the Western Front ” by Erich Maria Remarque and “ In Flanders Fields ” by Canadian doctor Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae . In the latter poem, McCrae writes from the perspective of the fallen soldiers:

Published in 1915, the poem inspired the use of the poppy as a symbol of remembrance.

Visual artists like Otto Dix of Germany and British painters Wyndham Lewis, Paul Nash and David Bomberg used their firsthand experience as soldiers in World War I to create their art, capturing the anguish of trench warfare and exploring the themes of technology, violence and landscapes decimated by war.

The Eastern Front

On the Eastern Front of World War I, Russian forces invaded the German-held regions of East Prussia and Poland but were stopped short by German and Austrian forces at the Battle of Tannenberg in late August 1914.

Despite that victory, Russia’s assault forced Germany to move two corps from the Western Front to the Eastern, contributing to the German loss in the Battle of the Marne.

Combined with the fierce Allied resistance in France, the ability of Russia’s huge war machine to mobilize relatively quickly in the east ensured a longer, more grueling conflict instead of the quick victory Germany had hoped to win under the Schlieffen Plan .

Russian Revolution

From 1914 to 1916, Russia’s army mounted several offensives on World War I’s Eastern Front but was unable to break through German lines.

Defeat on the battlefield, combined with economic instability and the scarcity of food and other essentials, led to mounting discontent among the bulk of Russia’s population, especially the poverty-stricken workers and peasants. This increased hostility was directed toward the imperial regime of Czar Nicholas II and his unpopular German-born wife, Alexandra.

Russia’s simmering instability exploded in the Russian Revolution of 1917, spearheaded by Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks , which ended czarist rule and brought a halt to Russian participation in World War I.

Russia reached an armistice with the Central Powers in early December 1917, freeing German troops to face the remaining Allies on the Western Front.

America Enters World War I

At the outbreak of fighting in 1914, the United States remained on the sidelines of World War I, adopting the policy of neutrality favored by President Woodrow Wilson while continuing to engage in commerce and shipping with European countries on both sides of the conflict.

Neutrality, however, it was increasingly difficult to maintain in the face of Germany’s unchecked submarine aggression against neutral ships, including those carrying passengers. In 1915, Germany declared the waters surrounding the British Isles to be a war zone, and German U-boats sunk several commercial and passenger vessels, including some U.S. ships.

Widespread protest over the sinking by U-boat of the British ocean liner Lusitania —traveling from New York to Liverpool, England with hundreds of American passengers onboard—in May 1915 helped turn the tide of American public opinion against Germany. In February 1917, Congress passed a $250 million arms appropriations bill intended to make the United States ready for war.

Germany sunk four more U.S. merchant ships the following month, and on April 2 Woodrow Wilson appeared before Congress and called for a declaration of war against Germany.

Gallipoli Campaign

With World War I having effectively settled into a stalemate in Europe, the Allies attempted to score a victory against the Ottoman Empire, which entered the conflict on the side of the Central Powers in late 1914.

After a failed attack on the Dardanelles (the strait linking the Sea of Marmara with the Aegean Sea), Allied forces led by Britain launched a large-scale land invasion of the Gallipoli Peninsula in April 1915. The invasion also proved a dismal failure, and in January 1916 Allied forces staged a full retreat from the shores of the peninsula after suffering 250,000 casualties.

Did you know? The young Winston Churchill, then first lord of the British Admiralty, resigned his command after the failed Gallipoli campaign in 1916, accepting a commission with an infantry battalion in France.

British-led forces also combated the Ottoman Turks in Egypt and Mesopotamia , while in northern Italy, Austrian and Italian troops faced off in a series of 12 battles along the Isonzo River, located at the border between the two nations.

Battle of the Isonzo

The First Battle of the Isonzo took place in the late spring of 1915, soon after Italy’s entrance into the war on the Allied side. In the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo, also known as the Battle of Caporetto (October 1917), German reinforcements helped Austria-Hungary win a decisive victory.

After Caporetto, Italy’s allies jumped in to offer increased assistance. British and French—and later, American—troops arrived in the region, and the Allies began to take back the Italian Front.

World War I at Sea

In the years before World War I, the superiority of Britain’s Royal Navy was unchallenged by any other nation’s fleet, but the Imperial German Navy had made substantial strides in closing the gap between the two naval powers. Germany’s strength on the high seas was also aided by its lethal fleet of U-boat submarines.

After the Battle of Dogger Bank in January 1915, in which the British mounted a surprise attack on German ships in the North Sea, the German navy chose not to confront Britain’s mighty Royal Navy in a major battle for more than a year, preferring to rest the bulk of its naval strategy on its U-boats.

The biggest naval engagement of World War I, the Battle of Jutland (May 1916) left British naval superiority on the North Sea intact, and Germany would make no further attempts to break an Allied naval blockade for the remainder of the war.

World War I Planes

World War I was the first major conflict to harness the power of planes. Though not as impactful as the British Royal Navy or Germany’s U-boats, the use of planes in World War I presaged their later, pivotal role in military conflicts around the globe.

At the dawn of World War I, aviation was a relatively new field; the Wright brothers took their first sustained flight just eleven years before, in 1903. Aircraft were initially used primarily for reconnaissance missions. During the First Battle of the Marne, information passed from pilots allowed the allies to exploit weak spots in the German lines, helping the Allies to push Germany out of France.

The first machine guns were successfully mounted on planes in June of 1912 in the United States, but were imperfect; if timed incorrectly, a bullet could easily destroy the propeller of the plane it came from. The Morane-Saulnier L, a French plane, provided a solution: The propeller was armored with deflector wedges that prevented bullets from hitting it. The Morane-Saulnier Type L was used by the French, the British Royal Flying Corps (part of the Army), the British Royal Navy Air Service and the Imperial Russian Air Service. The British Bristol Type 22 was another popular model used for both reconnaissance work and as a fighter plane.

Dutch inventor Anthony Fokker improved upon the French deflector system in 1915. His “interrupter” synchronized the firing of the guns with the plane’s propeller to avoid collisions. Though his most popular plane during WWI was the single-seat Fokker Eindecker, Fokker created over 40 kinds of airplanes for the Germans.

The Allies debuted the Handley-Page HP O/400, the first two-engine bomber, in 1915. As aerial technology progressed, long-range heavy bombers like Germany’s Gotha G.V. (first introduced in 1917) were used to strike cities like London. Their speed and maneuverability proved to be far deadlier than Germany’s earlier Zeppelin raids.

By the war’s end, the Allies were producing five times more aircraft than the Germans. On April 1, 1918, the British created the Royal Air Force, or RAF, the first air force to be a separate military branch independent from the navy or army.

Second Battle of the Marne

With Germany able to build up its strength on the Western Front after the armistice with Russia, Allied troops struggled to hold off another German offensive until promised reinforcements from the United States were able to arrive.

On July 15, 1918, German troops launched what would become the last German offensive of the war, attacking French forces (joined by 85,000 American troops as well as some of the British Expeditionary Force) in the Second Battle of the Marne . The Allies successfully pushed back the German offensive and launched their own counteroffensive just three days later.

After suffering massive casualties, Germany was forced to call off a planned offensive further north, in the Flanders region stretching between France and Belgium, which was envisioned as Germany’s best hope of victory.

The Second Battle of the Marne turned the tide of war decisively towards the Allies, who were able to regain much of France and Belgium in the months that followed.

The Harlem Hellfighters and Other All-Black Regiments

By the time World War I began, there were four all-Black regiments in the U.S. military: the 24th and 25th Infantry and the 9th and 10th Cavalry. All four regiments comprised of celebrated soldiers who fought in the Spanish-American War and American-Indian Wars , and served in the American territories. But they were not deployed for overseas combat in World War I.

Blacks serving alongside white soldiers on the front lines in Europe was inconceivable to the U.S. military. Instead, the first African American troops sent overseas served in segregated labor battalions, restricted to menial roles in the Army and Navy, and shutout of the Marines, entirely. Their duties mostly included unloading ships, transporting materials from train depots, bases and ports, digging trenches, cooking and maintenance, removing barbed wire and inoperable equipment, and burying soldiers.

Facing criticism from the Black community and civil rights organizations for its quotas and treatment of African American soldiers in the war effort, the military formed two Black combat units in 1917, the 92nd and 93rd Divisions . Trained separately and inadequately in the United States, the divisions fared differently in the war. The 92nd faced criticism for their performance in the Meuse-Argonne campaign in September 1918. The 93rd Division, however, had more success.

With dwindling armies, France asked America for reinforcements, and General John Pershing , commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, sent regiments in the 93 Division to over, since France had experience fighting alongside Black soldiers from their Senegalese French Colonial army. The 93 Division’s 369 regiment, nicknamed the Harlem Hellfighters , fought so gallantly, with a total of 191 days on the front lines, longer than any AEF regiment, that France awarded them the Croix de Guerre for their heroism. More than 350,000 African American soldiers would serve in World War I in various capacities.

Toward Armistice

By the fall of 1918, the Central Powers were unraveling on all fronts.

Despite the Turkish victory at Gallipoli, later defeats by invading forces and an Arab revolt that destroyed the Ottoman economy and devastated its land, and the Turks signed a treaty with the Allies in late October 1918.

Austria-Hungary, dissolving from within due to growing nationalist movements among its diverse population, reached an armistice on November 4. Facing dwindling resources on the battlefield, discontent on the homefront and the surrender of its allies, Germany was finally forced to seek an armistice on November 11, 1918, ending World War I.

Treaty of Versailles

At the Paris Peace Conference in 1919, Allied leaders stated their desire to build a post-war world that would safeguard itself against future conflicts of such a devastating scale.

Some hopeful participants had even begun calling World War I “the War to End All Wars.” But the Treaty of Versailles , signed on June 28, 1919, would not achieve that lofty goal.

Saddled with war guilt, heavy reparations and denied entrance into the League of Nations , Germany felt tricked into signing the treaty, having believed any peace would be a “peace without victory,” as put forward by President Wilson in his famous Fourteen Points speech of January 1918.

As the years passed, hatred of the Versailles treaty and its authors settled into a smoldering resentment in Germany that would, two decades later, be counted among the causes of World War II .

World War I Casualties

World War I took the lives of more than 9 million soldiers; 21 million more were wounded. Civilian casualties numbered close to 10 million. The two nations most affected were Germany and France, each of which sent some 80 percent of their male populations between the ages of 15 and 49 into battle.

The political disruption surrounding World War I also contributed to the fall of four venerable imperial dynasties: Germany, Austria-Hungary, Russia and Turkey.

Legacy of World War I

World War I brought about massive social upheaval, as millions of women entered the workforce to replace men who went to war and those who never came back. The first global war also helped to spread one of the world’s deadliest global pandemics, the Spanish flu epidemic of 1918, which killed an estimated 20 to 50 million people.

World War I has also been referred to as “the first modern war.” Many of the technologies now associated with military conflict—machine guns, tanks , aerial combat and radio communications—were introduced on a massive scale during World War I.

The severe effects that chemical weapons such as mustard gas and phosgene had on soldiers and civilians during World War I galvanized public and military attitudes against their continued use. The Geneva Convention agreements, signed in 1925, restricted the use of chemical and biological agents in warfare and remain in effect today.

Photo Galleries

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

First World War: Causes and Effects Essay

Introduction, the causes of world war one, the effects of the war.

World War one seems like an ancient history with many cases of compelling wars to many people, but amazingly, it became known as the Great War because of influence it caused. It took place across European colonies and their surrounding seas between August 1914 and December 1918 (Tuchman, 2004). Almost sixty million troops mobilized for the war ended up in crippling situations.

For instance, more than eight million died and over thirty million people injured in the struggle. The war considerably evolved with the economic, political, cultural and social nature of Europe. Nations from the other continents also joined the war making it worse than it was.

Over a long period, most countries in Europe made joint defense treaties that would help them in battle if the need arose. This was for defense purposes. For instance, Russia linked with Serbia, Germany with Austria-Hungary, France with Russia, and Japan with Britain (Tuchman, 2004).

The war started with the declaration of war on Serbia by Austria-Hungary. This later led to the entry of countries allied to Serbia into the war so as to protect their partners.

Imperialism is another factor that led to the First World War. Many European countries found expansion of their territories enticing.

Before World War One, most European countries considered parts of Asia and Africa as their property because they were highly productive. European nations ended up in confrontations among themselves due to their desire for more wealth from Africa and Asia. This geared the whole world into war afterwards.

Competition to produce more weapons compared to other countries also contributed to the beginning of World War One. Many of the European nations established themselves well in terms of military capacity and eventually sought for war to prove their competence.

Desire for nationalism by the Serbians also played a crucial role in fueling the war. Failure to come to an agreement about Bosnia and Herzegovina led the countries to war. Both countries wanted to prove their supremacy.

Assassination of Archduke Ferdinand and his wife in Austria-Hungary sparked the war. Tuchman (2004) reveals that the Serbians assassinated Ferdinand in Sarajevo in June 1914 while protesting to the control of Sarajevo by Austria-Hungary. The assassination led to war between Serbia and Austria-Hungary. This led to mobilization of Russian troops in preparation for war.

The already prepared Germany immediately joined the war against Russia and France. On the other hand, Russians declared war on Austria and Germany. The invasion of the neutral Belgium by Germany triggered Britain to declare war against Germans.

Earlier, Britain had promised to defend Belgium against any attack. The British entered France with the intention of stopping the advancement of Germany. This intensified the enmity among the countries involved (Tuchman, 2004).

Tuchman (2004) argues that the French together with their weak allies held off the fighting in Paris and adopted trench warfare. The French had decided to defend themselves from the trenches instead of attacking. This eventually gave them the victory.

Although The British had the largest number of fleet in the world by the end of 1914, they could not end the First World War. The Germans had acquired a well-equipped fleet. This helped them advance the war to 1915. However, many countries participating in the war began to prepare for withdrawal from the conflict. The war had changed the social roles in many of the countries involved.

For instance, women in Britain performed duties initially considered masculine so as to increase their income (Tuchman, 2004). In the Western Front, the innovated gas weapons killed many people. In the Eastern Front, Bulgaria joined Austria-Hungary as the central power leading to more attacks in Serbia and Russia. Italy too joined the war and fought with the allied forces.

The British seized German ports in 1916. This led to severe shortage of food in Germany. The shortages encountered by the Germans led to food riots in many of the German towns. The Germans eventually adopted submarine warfare. With the help of this new tactic, they targeted Lusitania, one of the ships from America.

This led to the loss of many lives, including a hundred Americans, prompting America to join the war. On 1stJuly the same year, over twenty thousand people died and forty thousand injured. However, in the month of May the same year, the British managed to cripple the German fleet and eventually take control of the sea (Tuchman, 2004).

The year 1917 marked a remarkable change in Germany. Attempts to convince Mexico to invade the United States proved futile. Germany eventually lost due to lack of sufficient aid from their already worn-out allies. Towards the end of 1918, British food reserves became exhausted. This reduced the intensity of the warfare against Germans. It was in this same year that they established “Women Army Auxiliary Corps”.

It placed women on the forefront in the battlefield for the first time. On the Western Front, the Germans weakness eventually led to their defeat. The war came to an end. The British eventually emerged the superior nation among all the European nations.

The signing of the Treaty of Versailles on twenty eighth June 1919 between the Allied powers and Germany officially ended the war. Other treaties signed later contributed to the enforcement of peace among nations involved in the war (Tuchman, 2004).

First World War outlined the beginning of the modern era; it had an immense impact on the economic and political status of many countries. European countries crippled their economies while struggling to manufacture superior weapons. The Old Russian Empire replaced by a socialist system led to loss of millions of people.

The known Austro-Hungarian Empire and old Holy Roman Empire became extinct. The drawing of Middle East and Europe maps led to conflicts in the present time. The League of Nations formed later contributed significantly in solving international conflicts.

In Britain, a class system arose demarcating the lower class from the advantaged class whereas, in France the number of men significantly reduced (Tuchman, 2004). This led to sharing of the day to day tasks between men and women. First World War also caused the merger of cultures among nations. Poets and authors portray this well. Many people also ended up adopting the western culture and neglecting their own.

In conclusion, the First World War led to the loss of many lives. These included soldiers and innocent citizens of the countries at war. The First World War also led to extensive destruction of property. The infrastructure and buildings in many towns crumbled. It contributed to displacement of people from their homes. Many people eventually lost their land.

The loss of land and displacement of people has substantially contributed to the current conflicts among communities and nations. However, the First World War paved way to the establishment of organizations that ensured that peace prevailed in the world. It also led to the advancement of science and technology. It led to the realization that women too could perform masculine tasks.

Tuchman, W. B. (2004). The Guns of August : New York: Random House Publishing Group.

- First World War Issues and Causes

- First World War: German and Austrian Policies' Response

- World War I Causes by Ethnic Problems in Austro-Hungary

- Was the birthplace of Canada at Vimy Rigde

- United States and World War I

- Why Europe Went to War

- WWI-War: Revolution, and Reconstruction

- World War I Technology

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2019, May 20). First World War: Causes and Effects. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-one-essay/

"First World War: Causes and Effects." IvyPanda , 20 May 2019, ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-one-essay/.

IvyPanda . (2019) 'First World War: Causes and Effects'. 20 May.

IvyPanda . 2019. "First World War: Causes and Effects." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-one-essay/.

1. IvyPanda . "First World War: Causes and Effects." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-one-essay/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "First World War: Causes and Effects." May 20, 2019. https://ivypanda.com/essays/world-war-one-essay/.

World War I Introduction and Overview

Belligerent nations.

- Origins of World War I

World War I on Land

World war i at sea, technical innovation, modern view.

- M.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

- B.A., Medieval Studies, Sheffield University

World War I was a major conflict fought in Europe and around the world between July 28, 1914, and November 11, 1918. Nations from across all non-polar continents were involved , although Russia, Britain, France, Germany, and Austria-Hungary dominated. Much of the war was characterized by stagnant trench warfare and massive loss of life in failed attacks; over eight million people were killed in battle.

The war was fought by two main power blocks: the Entente Powers , or 'Allies,' comprised of Russia, France, Britain (and later the U.S.), and their allies on one side and the Central Powers of Germany, Austro-Hungary, Turkey, and their allies on the other. Italy later joined the Entente. Many other countries played smaller parts on both sides.

Origins of World War I

To understand the origins , it is important to understand how politics at the time. European politics in the early twentieth century were a dichotomy: many politicians thought war had been banished by progress while others, influenced partly by a fierce arms race, felt war was inevitable. In Germany, this belief went further: the war should happen sooner rather than later, while they still (as they believed) had an advantage over their perceived major enemy, Russia. As Russia and France were allied, Germany feared an attack from both sides. To mitigate this threat, the Germans developed the Schlieffen Plan , a swift looping attack on France designed to knock it out early, allowing for concentration on Russia.

Rising tensions culminated on June 28th, 1914 with the assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand by a Serbian activist, an ally of Russia. Austro-Hungary asked for German support and was promised a 'blank cheque'; they declared war on Serbia on July 28th. What followed was a sort of domino effect as more and more nations joined the fight . Russia mobilized to support Serbia, so Germany declared war on Russia; France then declared war on Germany. As German troops swung through Belgium into France days later, Britain declared war on Germany too. Declarations continued until much of Europe was at war with each other. There was widespread public support.

After the swift German invasion of France was stopped at the Marne, 'the race to the sea' followed as each side tried to outflank each other ever closer to the English Channel. This left the entire Western Front divided by over 400 miles of trenches, around which the war stagnated. Despite massive battles like Ypres , little progress was made and a battle of attrition emerged, caused partly by German intentions to 'bleed the French dry' at Verdun and Britain's attempts on the Somme . There was more movement on the Eastern Front with some major victories, but there was nothing decisive and the war carried on with high casualties.

Attempts to find another route into their enemy’s territory led to the failed Allied invasion of Gallipoli, where Allied forces held a beachhead but were halted by fierce Turkish resistance. There was also conflict on the Italian front, the Balkans, the Middle East, and smaller struggles in colonial holdings where the warring powers bordered each other.

Although the build-up to war had included a naval arms race between Britain and Germany, the only large naval engagement of the conflict was the Battle of Jutland, where both sides claimed victory. Instead, the defining struggle involved submarines and the German decision to pursue Unrestricted Submarine Warfare (USW). This policy allowed submarines to attack any target they found, including those belonging to the 'neutral' United States, which caused the latter to enter the war in 1917 on behalf of the Allies, supplying much-needed manpower.

Despite Austria-Hungary becoming little more than a German satellite, the Eastern Front was the first to be resolved, the war causing massive political and military instability in Russia, leading to the Revolutions of 1917 , the emergence of socialist government and surrender on December 15. Efforts by the Germans to redirect manpower and take the offensive in the west failed and, on November 11, 1918 (at 11:00 am), faced with allied successes, massive disruption at home and the impending arrival of vast US manpower, Germany signed an Armistice, the last Central power to do so.

Each of the defeated nations signed a treaty with the Allies, most significantly the Treaty of Versailles which was signed with Germany, and which has been blamed for causing further disruption ever since. There was devastation across Europe: 59 million troops had been mobilized, over 8 million died and over 29 million were injured. Huge quantities of capital had been passed to the now emergent United States and the culture of every European nation was deeply affected and the struggle became known as The Great War or The War to End All Wars.

World War I was the first to make major use of machine guns, which soon showed their defensive qualities. It was also the first to see poison gas used on the battlefields, a weapon which both sides made use of, and the first to see tanks, which were initially developed by the allies and later used to great success. The use of aircraft evolved from simply reconnaissance to a whole new form of aerial warfare.

Thanks partly to a generation of war poets who recorded the horrors of the war and a generation of historians who castigated the Allied high command for their decisions and ‘waste of life’ (Allied soldiers being the 'Lions led by Donkeys'), the war was generally viewed as a pointless tragedy. However, later generations of historians have found mileage in revising this view. While the Donkeys have always been ripe for recalibration, and careers built on provocation have always found material (such as Niall Ferguson's The Pity of War ), the centenary commemorations found historiography split between a phalanx wishing to create a new martial pride and sideline the worst of the war to create an image of a conflict well worth fighting and then truly won by the allies, and those who wished to stress the alarming and pointless imperial game millions of people died for. The war remains highly controversial and as subject to attack and defense as the newspapers of the day.

- 5 Key Causes of World War I

- World War I Timeline: 1914, The War Begins

- World War I: A Stalemate Ensues

- World War I Timeline From 1914 to 1919

- The Fourteen Points of Woodrow Wilson's Plan for Peace

- The Causes and War Aims of World War One

- Causes of World War I and the Rise of Germany

- The Major Alliances of World War I

- Key Historical Figures of World War I

- World War I: A Battle to the Death

- World War 1: A Short Timeline Pre-1914

- The Countries Involved in World War I

- World War I: Opening Campaigns

- The First Battle of the Marne

- World War 1: A Short Timeline 1915

- World War I: A Global Struggle

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

Course: US history > Unit 7

- The presidency of Woodrow Wilson

- Blockades, u-boats and sinking of the Lusitania

- Zimmermann Telegram

- United States enters World War I

- World War I: Homefront

The United States in World War I

- Woodrow Wilson's Fourteen Points

- Paris Peace Conference and Treaty of Versailles

- More detail on the Treaty of Versailles and Germany

- The League of Nations

- The Treaty of Versailles

- The First World War

- World War I was the deadliest conflict until that point in human history, claiming tens of millions of casualties on all sides.

- Under President Woodrow Wilson, the United States remained neutral until 1917 and then entered the war on the side of the Allied powers (the United Kingdom, France, and Russia).

- The experience of World War I had a major impact on US domestic politics, culture, and society. Women achieved the right to vote, while other groups of American citizens were subject to systematic repression.

War in Europe and US neutrality

Principal combatants on each side included:, the united states enters world war i, world war i on the home front, aftermath: consequences of world war i, what do you think.

- For more on the origins of the First World War, see Margaret MacMillan, The War that Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (New York: Random House, 2014).

- For more on the nature of the fighting on the Western front, see Ian Ousby, The Road to Verdun: World War I’s Most Momentous Battle and the Folly of Nationalism (New York: Random House, 2002).

- Christopher Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen (New York: Oxford University Press, 2008), 7.

- For more on the experience of American soldiers in WWI, see Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1998).

- For more on the women’s rights movement, see Eleanor Flexner and Ellen Fitzpatrick, Century of Struggle: The Woman’s Rights Movement in the United States (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1996).

- For more, see Capozzola, Uncle Sam Wants You.

- For more, see John Milton Cooper, Jr., Breaking the Heart of the World: Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the League of Nations (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

Home — Essay Samples — Sociology — Connection — Unveiling the Causes and Consequences of World War I

Unveiling The Causes and Consequences of World War I

- Categories: Connection Contract Monarchy

About this sample

Words: 557 |

Published: Mar 1, 2019

Words: 557 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Sociology Law, Crime & Punishment Government & Politics

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 493 words

2 pages / 954 words

3 pages / 1261 words

3 pages / 1462 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Connection

Dublin, the capital of Ireland, is a city brimming with stories waiting to be told. Among its myriad narratives, there's a particular fascination with the serendipitous encounters that occur on Dublin's trains. The concept of [...]

Qualities of strong relationships are the foundation upon which enduring connections are built. This essay delves into the essential characteristics that contribute to the strength and resilience of relationships. By exploring [...]

Remember by Joy Harjo is a powerful and thought-provoking poem that explores themes of identity, memory, and connection to the natural world. Through the use of vivid imagery, symbolism, and a unique narrative structure, Harjo [...]

A. "Mr. Holland's Opus" is a heartwarming film that tells the story of a dedicated music teacher, Glenn Holland, and his journey at John F. Kennedy High School. The movie beautifully captures the transformative power of music [...]

In the ever-evolving tapestry of human existence, two contrasting outlooks often guide our perceptions and actions: realism and optimism. Realism encourages us to confront life's challenges with a clear-eyed view of the world, [...]

Love can hold us captive, chain us down and make us slaves to its cruel ways, blinding us from all judgement. The human condition of love can be expressed as a strong affection for another arising out of kinship, enthusiasm, or [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

World War One Essay

Germany was responsible for World War One. To what extent do you agree with this statement?

Essay by Laura Iafur, 3rd Form

Taking place on 28th July 1914 until 11th November 1918, World War One was one of the deadliest conflicts in history, ending the lives of millions of people. Although no one country deserves more blame than the other countries, many would argue that the country of Serbia, after all, it was a group of Serbian terrorists who killed the hero of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, Franz Ferdinand. This is considered by many, what triggered this war. Others suggest Austria-Hungarian is to blame the most, they wanted war with Serbia even before Franz Ferdinand’s assassination, it seems like the assassination was the opportunity they were waiting for. Some could even say that it was Russia, who was the first to mobilize its troops, creating even more tension in an already unstable Europe. These countries are all guilty for such a violent war, but Germany, being the one that has the blank cheque to Austria-Hungary, is the most responsible of all; without backing up Austria-Hungary, it is improbable that Austria-Hungary would have acted so recklessly.

On 5th July 1914, Germany gave the “blank cheque” of unconditional support to the Austrian-Hungarian Empire, fully aware of the consequences it was probably going to bring. At that moment, Germany had the strongest army, with 2,200,000 soldiers and warships, this guaranteed Austria-Hungary that no matter how drastically they acted, they would receive massive support from Germany. If Germany had not given this back up to Austria-Hungary, they most likely would have done something other than declaring war. Germany knew that Russia would most likely help Serbia, which meant that a local war would escalate into a Global war, but they did it anyway.

Germany also dragged Britain into the war when using the Schlieffen plan. On 2nd August, Germany asked for permission for their army to pass through Belgium, to get to France, but they were refused. Sir Edward Grey proposed to Germany that Britain would stay if Germany did not attack France, but the German generals denied this. On 3rd August, Germany violated international treaties by invading Belgium, a neutral country; knowing that Britain was obligated to help Belgium if an invasion occurred. Therefore, Britain declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914.

The enormous increase in tension between these countries was one of the main reasons for this war to start, there are various factors that led to more tension, many in which Germany was involved. One of these factors was the German and British naval race which did not make Britain happy. (“Britannia rules the waves”), and at the end of 1914, Britain was this race.

The Moroccan crisis, 1906, was another factor. The French wanted to conquer Morocco and Britain agreed to help, but in 1905 Kaiser Wilhelm visited Morocco and promised to protect it against anyone who threatened it. The French and British were furious. Germany had to promise to stay out of Morocco, which didn’t make them happy at all. In 1911, there was a revolution in Morocco, the French sent in an army to control it. Kaiser Wilhelm sent a gunboat to the Moroccan part of Agadir; this angered the French and British. Germany was forced to back down, which made them very angry, it increased their resentment. Kaiser Wilhelm was determined to win the next crisis. All this evidence shows that Germany, at that point was ashamed. They had lost various crisis issues and since they could not allow themselves another defeat. Germany had decided they needed to prove their power, this being the reason they acted in such a careless manner.

Austria-Hungary also deserves part of the blame; they were the ones who declared war first on Serbia on 28th July, 1914. Before 1914, assassinations of royal figures did not usually result in war. However, Austria-Hungary saw the Sarajevo assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife as an opportunity to conquer and destroy Serbia. The Austrian Chief of Staff General Hotzendoz wanted to attack Serbia long before the assassination.

Austria-Hungary sent an ultimatum to Serbia (23rd July) with ten very exigent requests that needed to be accepted to avoid military conflict. Serbia accepted all requests apart from one, which was to allow Austria-Hungary to enter Serbia and oversee investigation and prosecution on the assassination of Franz Ferdinand. Nonetheless, this was not enough for Austria-Hungary, so they declared war, and with Germany’s support, it would’ve provided an easy win.

On the other hand, if Austria-Hungary did not make a move against Serbia, the different nationalities living in the Austria-Hungarian territory could act against their leaders giving the impression to other countries that there won’t have been any consequences. Austria-Hungary could have acted in a different manner on the Serbia war, but it was due to Germany who empowered them to act this way.

The assassination of Franz Ferdinand was conducted by a Serbian terrorist named Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo, Bosnia, 28th June 1914. This was the spark that caused the war. Gavrilo was a nationalist who wanted Bosnia to be its own country, and when Ferdinand announced his trip to SaraJevo, it was the perfect opportunity to strike against Austria-Hungary. Gavrilo was a member of a terrorist group named, Black Hand. Austria-Hungary suspected the involvement of Serbia in the Bosnian attack, thus representing the final act in a long-standing rivalry between Austria-Hungary and Serbia. Russia did not want a war, the Russian Grand Council decided if Serbia was to be invaded, it would have to request a conference to asses the issue. However, Russia had previous issues with Serbia regarding the Bosnian crisis in 1908.

To conclude, World War One was a chain reaction triggered by the assassination Franz Ferdinand; however, Serbia wasn’t mostly responsible but Germany, who pushed Austria-Hungary in making those decisions leading to the global conflict. The alliance system was created to prevent war, but it did the total opposite, where all the countries were forced to join the war.

House Magazine Archive

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

UPSC Coaching, Study Materials, and Mock Exams

Enroll in ClearIAS UPSC Coaching Join Now Log In

Call us: +91-9605741000

First World War (1914-1918): Causes and Consequences

Last updated on October 10, 2023 by Alex Andrews George

Table of Contents

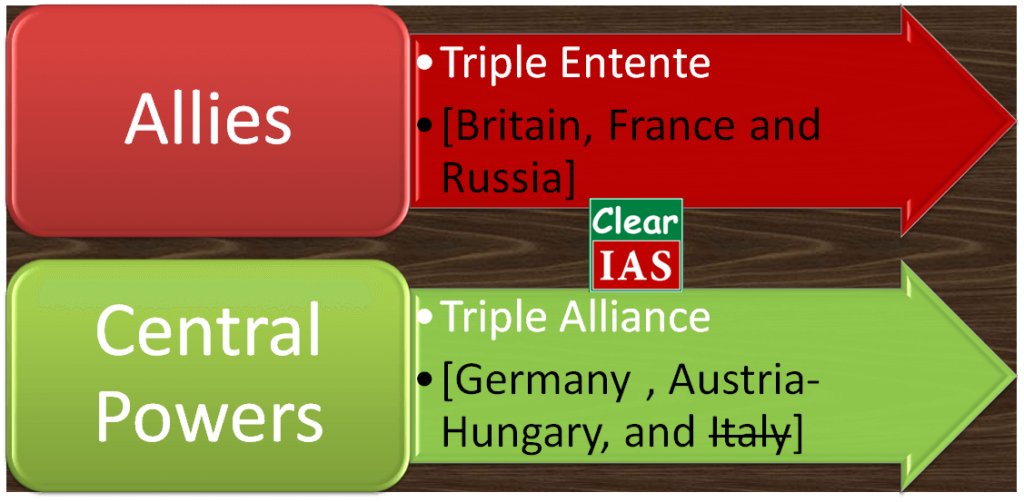

The Two Groups: Allies vs Central Powers

Causes of the First World War

In the background there were many conflicts between European nations. Nations grouped among themselves to form military alliances as there were tension and suspicion among them. The causes of the First World War were:

(1) Conflict between Imperialist countries: Ambition of Germany

- Conflict between old imperialist countries (Eg: Britain and France) vs new imperialist countries (Eg: Germany).

- Germany ship – Imperator.

- German railway line – from Berlin to Baghdad.

(2) Ultra Nationalism

- Pan Slav movement – Russian, Polish, Czhech, Serb, Bulgaria and Greek.

- Pan German movement.

(3) Military Alliance

- Triple Alliance or Central Powers (1882) – Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary.

- Triple Entente or Allies (1907) – Britain, France, Russia.

Note: Although Italy was a member of the Triple Alliance alongside Germany and Austria-Hungary, it did not join the Central Powers, as Austria-Hungary had taken the offensive, against the terms of the alliance. These alliances were reorganised and expanded as more nations entered the war: Italy, Japan and the United States joined the Allies, while the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria joined the Central Powers.

(4) International Anarchy

- Secret agreement between Britain and France allowing Britain to control Egypt and France to take over Morocco. Germany opposed, but settled with a part of French Congo.

- Hague conference of 1882 and 1907 failed to emerge as an international organisation.

(5) Balkan Wars

- Many Balkan nations (Serbia, Bulgaria, Albania, Greece and Montenegro) were under the control of Turkey. They defeated Turkey in the First Balkan War. The subsequent war was between the Balkan countries themselves – Eg: Serbia vs Bulgaria.

- Defeated countries like Turkey and Bulgaria sought German help.

(6) Alsace-Loraine

- During German unification, Germany got Alsace-Loraine from France. France wanted to capture Alsace-Loraine back from Germany.

(7) Immediate Cause: assassination of Francis Ferdinand

- Austrian Archduke Francis Ferdinand was assassinated by a Serbian native (in Bosnia). Austria declared war on Serbia on 28th July, 1914. [Reason for assassination: Annexation by Austria the Bosnia-Herzegovina, against the congress of Berlin, 1878]

The Course of the War

- Group 1 (Allies): Serbia, Russia, Britian, France, USA, Belgium, Portugal, Romania etc

- Group 2 (Central Powers): Austria-Hungary, Germany, Italy, Turkey, Bulgaria etc.

- War on Western Side: Battle of Marne.

- War on Eastern Side: Battle of Tennenberg (Russia was defeated).

- War on the Sea: Batter of Dogger Bank (Germany was defeated), Battle of Jutland (Germany retreated).

- USA entered in 1917.

- Russia withdrew in 1917 after October Revolution.

Treaty of Versailles, Paris

- Germany signed a treaty with Allies (Triple Entente) on 28th June 1919. It was signed at Versailles, near Paris. (14 points)

- Leaders: Clemenceau – France, Lloyd George – Britain, Woodrow Wilson – USA, Orlando – Italy.

Treaties after World War I

- Treaty of Paris – with Germany.

- Treaty of St.Germaine – with Austria.

- Treaty of Trianon- with Hungary.

- Treaty of Neuilly – with Bulgaria.

- Treaty of Severes – with Turkey.

Consequences of First World War

- Rule of King ended in Germany: Germany became a republic on November 1918. The German Emperor Kaiser William II fled to Holland.

- Around 1 crore people were killed.

- Unemployment and famine.

- The fall of Russian empire after October revolution (1917) which resulted in the formation of USSR (1922)

- Emergence of USA as a super power.

- Beginning of the end of European supremacy.

- Japan became a powerful country in Asia.

- Poland, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia became new independent states.

- Baltic countries – Estonia, Latvia and Lithvania – became independent.

- Rule of Ottamans came to an end in Turkey.

- New boundary lines were drawn for Austria, Germany and Turkey.

- Strengthened independence movements in Asia and Africa.

- League of Nations came into being.

- Germany had to return Alsace-Loraine to France.

- German colonies were shared.

- Germany gave up Saar coal field.

- Germany gave up Polish corridor, and made city of Danzig independent.

- Monarchy was abolished in Germany, Austria, Hungary, Turkey and Russia.

- The harsh clauses of the Treaty of Versailles finally resulted in the second world war .

Related posts

- Treaty of Versailles

- Second World War (1939-1945): Causes and Consequences

Aim IAS, IPS, or IFS?

About Alex Andrews George

Alex Andrews George is a mentor, author, and social entrepreneur. Alex is the founder of ClearIAS and one of the expert Civil Service Exam Trainers in India.

He is the author of many best-seller books like 'Important Judgments that transformed India' and 'Important Acts that transformed India'.

A trusted mentor and pioneer in online training , Alex's guidance, strategies, study-materials, and mock-exams have helped many aspirants to become IAS, IPS, and IFS officers.

Reader Interactions

October 25, 2016 at 7:17 pm

May 8, 2024 at 12:43 am

keep your feet covered

November 21, 2016 at 11:32 pm

June 27, 2018 at 10:15 pm

Nice and precise

July 31, 2017 at 10:03 pm

Thanks.. It’s good

September 1, 2017 at 5:06 pm

That was very essential

February 20, 2018 at 7:51 pm

thank you very much.

April 28, 2018 at 3:28 pm

June 22, 2018 at 9:47 pm

Good…..

August 2, 2018 at 3:09 pm

In the course of war, italy is mentioned with central powers while it has joined the allies. Please clarify

December 17, 2020 at 7:02 pm

shut up idiot

August 28, 2018 at 5:26 am

Its very good answer😊

September 23, 2018 at 2:51 pm

Helpful resources

October 1, 2018 at 2:49 pm

Very nice covered

October 13, 2018 at 9:32 pm

U should defined it little more ….but overall it is good

March 30, 2021 at 9:24 am

You didn’t mention about the powerful weapons that was owned by the European countries. Please clarify that portion. Otherwise it’s a very precise and useful note. Thank you.

November 9, 2018 at 1:03 am

January 31, 2019 at 9:55 am

very good answer

February 28, 2019 at 7:01 am

Thanks a lot.

February 28, 2019 at 7:02 am

March 3, 2019 at 5:57 pm

Thank you Its a very nice answer Thus I can get full marks So i am thankful to you

March 22, 2019 at 1:22 pm

April 25, 2019 at 9:36 pm

you are my rolemodal

May 22, 2019 at 3:33 am

nice task….& thanks alot…!!!!

July 17, 2019 at 10:02 pm

I really appreciate may Almighty reward you with goodness

October 8, 2019 at 3:44 pm

Was very useful for ICSE projects (history and civics). Thanks a lot.

November 4, 2019 at 6:39 am

Ath polichu….😁😂

November 23, 2019 at 11:35 pm

Very good sir

November 25, 2019 at 2:42 am

Thank you. Learnt a lot

June 13, 2020 at 9:19 pm

Thanks, It was nice!

December 5, 2020 at 3:22 pm

Thanks, it helped in-home assignment

February 4, 2021 at 11:29 am

You forgot to mention ottoman empire

You forgot to mention ottoman empire in the central power

March 12, 2021 at 3:26 pm

Interesting topic. Great job . Thank you.

March 13, 2023 at 9:35 pm

I like how well u explained ww1 it’s a really good. I Like this article this article is a reliable source!

March 14, 2023 at 3:29 am

Thank U For Making This Helped Me With History Thanks Learned Alot!!!!!!

May 8, 2023 at 8:45 pm

YOu forgot to tak about the ottoman emprire

June 3, 2023 at 11:10 pm

Nice but no clear explanation

January 20, 2024 at 10:36 am

World War I, also known as the First World War, was a massive conflict that occurred from July 28, 1914, to November 11, 1918. It involved major global powers divided into two alliances: the Allies (comprising the British Empire, France, and the Russian Empire) and the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary). The war’s causes were multifaceted, including conflicts between imperialist countries, Germany’s ambitions, ultra-nationalism, military alliances, international anarchy, Balkan Wars, Alsace-Lorraine dispute, and the assassination of Francis Ferdinand. The war led to significant consequences and the Treaty of Versailles in Paris, which aimed to establish peace. 🌍💥🤔

January 20, 2024 at 11:00 am

World War I, a colossal conflict from 1914 to 1918, involved major powers forming two opposing alliances: the Allies (including the British Empire, France, and Russia) against the Central Powers (Germany and Austria-Hungary). Key causes were imperialist rivalries, with Germany’s ambitions and military buildup, ultra-nationalism fueling movements like Pan-Slav and Pan-German, military alliances (Triple Alliance and Triple Entente), and international disputes like Egypt and Morocco. These tensions escalated until the assassination of Francis Ferdinand triggered the war. The aftermath brought the Treaty of Versailles and reshaped the world order, marking a pivotal moment in history. 🌍🔥🕊️ #WWI #History

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Don’t lose out without playing the right game!

Follow the ClearIAS Prelims cum Mains (PCM) Integrated Approach.

Join ClearIAS PCM Course Now

UPSC Online Preparation

- Union Public Service Commission (UPSC)

- Indian Administrative Service (IAS)

- Indian Police Service (IPS)

- IAS Exam Eligibility

- UPSC Free Study Materials

- UPSC Exam Guidance

- UPSC Prelims Test Series

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Online

- UPSC Prelims

- UPSC Interview

- UPSC Toppers

- UPSC Previous Year Qns

- UPSC Age Calculator

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- About ClearIAS

- ClearIAS Programs

- ClearIAS Fee Structure

- IAS Coaching

- UPSC Coaching

- UPSC Online Coaching

- ClearIAS Blog

- Important Updates

- Announcements

- Book Review

- ClearIAS App

- Work with us

- Advertise with us

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- Talk to Your Mentor

Featured on

and many more...

Reading Comprehension: Online Workshop

Thank You 🙌

Learn the short-cut tips nobody knows about solving Reading Comprehension (RC) passages.

Take clearias mock exams: analyse your progress.

Analyse Your Performance and Track Your All-India Ranking

Ias/ips/ifs online coaching: target cse 2025.

Are you struggling to finish the UPSC CSE syllabus without proper guidance?

- Advanced Search

Version 1.0

Last updated 15 august 2019, alliance system 1914.

Alliances were an important feature of the international system on the eve of World War I. The formation of rival blocs of Great Powers has previously considered a major cause of the outbreak of war in 1914, but this assessment misses the point. Instead of increased rigidity, it was, rather, the uncertainty of the alliances’ cohesion in the face of a casus foederis that fostered a preference for high-risk crisis management among decision-makers.

Table of Contents

- 1 Introduction: Alliances and Great Power relations in Europe, 1815-1871

- 2 Dual Alliance and Triple Alliance

- 3 Franco-Russian Alliance and Triple Entente

- 4 Great Power Alliances on the Eve of War

- 5 Conclusion: 1914 - Have Alliances Failed?

Selected Bibliography

Introduction: alliances and great power relations in europe, 1815-1871 ↑.

Alliances were nothing new to international relations in modern Europe. The patterns of cooperation in the first half of the 18 th century had become so familiar that switching strategic partners in preparation for the Seven Years War was dubbed as “ renversement des alliances ”. However, with religious and ideological issues only of marginal relevance to the cabinets of Europe, war-time alliances could be overturned quite easily. The French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802) and Napoleonic Wars (1803-1815) put Great Britain and France in the role of perennial adversaries, both of them forging alliances with other powers if useful and possible. Paul W. Schroeder has argued that the anti-Napoleonic coalition of 1813-1814 proved to be a turning point in international relations, because the four major coalition partners - Great Britain, Russia , Austria , and Prussia - decided to put their alliance on a peace footing after the end of war in 1814 and the Vienna Settlement of 1815. The Quadruple Alliance was meant to guarantee the peace of Europe by keeping a watchful eye on France and to cooperate closely to thwart any threat to international stability on the continent, while the Holy Alliance (originally consisting of Russia, Austria and Prussia) added glamorous rhetoric to this idea. According to Schroeder, traditional balance of power policy gave way to a collective effort among the Great Powers to defend the rights and mutual obligations of all sovereign states, big or small. With France co-opted in 1818, the five Great Powers became known as the Pentarchy. The Pentarchy discussed problems related to the situation of smaller states and decided on solutions to them, a de-facto privilege of the Great Powers in a Europe of sovereign states with different level of strategic clout. Although conflicts among the Great Powers would set limits to their close cooperation in the following decades, the Concert of Europe was still at play in the debates about Balkan crises in the years and months prior to the outbreak of war in 1914. [1]

At its heyday, in the first years after the Congress of Vienna, the new consensus among the Great Powers was strong enough to make separate alliance treaties between some of them seem irrelevant. In the 1820s, with disputes over the future of Spain and her former colonies in Latin America and divergent intentions in the Eastern Question, Great Power relations were transformed. New alliances were forged between Britain and France and between the conservative monarchies of Russia, Prussia, and Austria. The latter was perceived as a bulwark anti-revolutionary policy, the former as a cooperation of more liberal-minded cabinets. With regard to the decline of the Ottoman Empire and its geopolitical consequences, different patterns of alignment emerged in 1840. It was this Eastern Question that sparked the first war between Europe’s Great Powers after the defeat of Napoleon I, Emperor of the French (1769-1821) . His nephew, Napoleon III, Emperor of the French (1808-1873) , was instrumental in the formation of an anti-Russian war coalition in 1853-1854. The Crimean War was a decisive blow to the Vienna Settlement, although the peace treaty of Paris in 1856 reiterated the idea of a Concert of Europe. It left Russia reeling from defeat and encouraged further revision of the international system. Alliances became important tools in the ensuing transformation of Europe. Secret treaties between France and Sardinia and Italy and Prussia, respectively, were crucial in the preparation for the wars of 1859 and 1866, and Prussia’s treaties with the southern German states came to bear in 1870-1871. The so-called Wars of Italian Independence and of German Unification changed the map of Europe by creating new nation states. They also left the Habsburg Monarchy and France in a much weaker position. The creation of Germany under Prussian leadership and the annexation of Alsace-Lorraine was the most obvious shift in the balance of power. [2]

Dual Alliance and Triple Alliance ↑

With the creation of nation states in Germany and Italy completed, 1871 marked a turning point in the development of Europe’s international order. In a series of three victorious wars, Prussia had forged the economically and militarily strong German Empire, which now held a particularly powerful position on the continent. After a crisis in the mid-1870s, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898) settled on a course of securing the empire ’s position by isolating France and engaging with the other Great Powers, in particular Austria-Hungary and Russia. Ever the skillful diplomat, Bismarck was able to achieve this much, but he left a difficult legacy to his successors after his dismissal in 1890. It turned out to be particularly difficult to maintain close ties with Russia without encouraging St. Petersburg to wage a policy of expansion on the Balkans . Several times, Bismarck tried to build on the traditional pattern of anti-revolutionary cooperation between the monarchies of the Romanovs, the Hohenzollern, and the Habsburgs. The Three Emperors’ League was agreed upon in a treaty between Alexander II, Emperor of Russia (1818-1881) , Wilhelm I, German Emperor (1797-1888) , and Francis Joseph I, Emperor of Austria (1830-1916) in September 1873. It evoked the spirit of the Holy Alliance, but would not survive the clash of interests between Austria-Hungary and Russia that developed just a few years later over the expansion of Russian influence in South East Europe and the creation of a Greater Bulgaria in the 1878 San Stefano peace treaty between Russia and the Ottoman Empire. [3]

The Balkan Crisis of the 1870s and the Congress of Berlin in 1878, at which Bismarck did not save Russia from international pressure to give up on the project of Greater Bulgaria, rattled the foundations of the cooperation between the three conservative monarchies of the Hohenzollerns, the Romanovs, and the Habsburgs. An Austrian initiative led to the so-called Dual Alliance, a defensive alliance between the German Empire and the Habsburg Monarchy. The secret alliance treaty of 7 October 1879 assured Austria-Hungary of German military assistance in case of a Russian attack on the Dual Monarchy. Austria-Hungary also committed herself to come to the rescue of her ally in case of a Russian attack on Germany, a highly unlikely scenario. The Germans would get little in return, since the Austrians were under no obligation to come to their ally’s rescue in the case of a French attack on the German Empire. Benevolent neutrality was all they had to promise, unless France would be fighting alongside Russia. [4]

Bismarck wanted to shield the Habsburg Monarchy from Russian aggression and to get a say in Austria’s foreign policy. Without German consent, any diplomatic or military action taken by the Austrians that led to Russian countermeasures might jeopardize Germany’s commitment to the alliance. The casus foederis , Bismarck made clear in the 1880s, would only be triggered if Austria’s actions were first cleared with Berlin and the subsequent Russian attack labeled “unprovoked”. In this way, Bismarck avoided a situation in which the weaker of the allies would be able to steer the stronger one towards war. The German chancellor was not only trying to commit Vienna to close coordination of its Balkan policy with Berlin; he also hoped to make the Dual Alliance the cornerstone of cooperation in other fields and to tie the Habsburg Monarchy to the German Reich in a way reminiscent of the Holy Roman Empire. Gyula Andrássy (1860-1929) , Bismarck’s opponent, refused to have the treaty ratified by parliaments , and it would be kept secret until 1889, when Bismarck published it to deter Russia at the height of the Dual Crisis. [5]

Nevertheless, the Dual Alliance was not considered to be just another international treaty, but rather the foundation and symbol of a special relationship between the German Empire and the Dual Monarchy. The very basis of Austro-Hungarian dualism, the dominating influence of the Germans in Austria and the Magyars in Hungary, was seen as non-negotiable in Berlin, in order to keep Slav aspirations in Europe at bay. German diplomats and politicians would not shy away from telling their counterparts so, but up to a point, the underlying Teutonic, anti-Slav rhetoric also limited Germany’s freedom of action. The term “ Nibelungentreue ”, applied to German-Austrian relations by Chancellor Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929) in 1909, put a name to the cultural underpinnings of the Dual Alliance that had to be accounted for by German politicians. With Italy staying out of the fray in 1914, the Dual Alliance became the nucleus of what would be called the war coalition of the Central Powers. [6]

The Dual Alliance would be renewed on a regular basis and still existed in 1914, but by that time, most contemporaries had begun to use the term Triple Alliance when they were talking about Germany’s and Austria-Hungary’s most important alliance treaty. As in the case of Germany, the creation of Italy as a nation state had come at the expense of the Habsburg Monarchy. But unlike Germany, where the idea of uniting the German-speaking parts of Austria with the German Empire enjoyed almost no support, the vision of an Italy that included the Italian-speaking regions of the Habsburg Monarchy held considerable appeal for the Italian elites. In addition, the aspiring new – and still not very strong – Great Power Italy was vying with Austria-Hungary for control in the Adriatic. The potential for conflict between both powers notwithstanding, Italy had reasons to cover her back while she was striving for colonial expansion in the Mediterranean. With France blocking Italy’s path by seizing Tunisia in 1881, the government in Rome had to turn to Vienna and Berlin in search of protection in case of future colonial conflicts.

In the Triple Alliance Treaty of 20 May 1882 between Germany, Austria-Hungary and Italy, Italy and Germany were promised military support in case of an unprovoked attack by France. If two or more of the Great Powers attacked one of the three alliance partners, the other two would also be required to intervene by force. If only one Great Power forced one of the allies to resort to war, the others were obliged to keep a neutral stance, unless they decided to help militarily. [7] Romania , whose king was a member of the Hohenzollern dynasty, acceded in October 1883. [8] The treaty was meant to be secret, but in 1883 an Italian politician made the existence of the alliance public. Its text would be kept secret, as would the articles that were to be added in later years when the treaty was up for renewal. From an Italian point of view, her allies’ pledge of support in case of a war with France was essential; for Bismarck, the alliance helped to keep France isolated and would, in combination with the Dual Alliance, allay Austrian fears of Russian dominance in South East Europe. Vienna’s intention to preserve the status quo on the Balkan peninsula resonated with British priorities in the Eastern Mediterranean. It was also in Berlin’s interest to see the emergence of an alignment of Italy, Great Britain, and Austria-Hungary. This was formalized in a set of agreements brokered by Bismarck that culminated in a treaty between Great Britain and Italy in February 1887, with Austria-Hungary in March 1887 and with Spain in May 1887. The so-called Mediterranean Entente defused conflicts between Austria-Hungary and Italy, but most importantly, it contained Russia in the Eastern Mediterranean quite successfully in the late 1880s and early 1890s.

In 1891, when the Triple Alliance was to be renewed for the second time, the Austrian minister of foreign affairs suggested to the Italians that an agreement between the two allies should be included, which aimed to preserve the status quo in the Balkans and the territorial integrity of the Ottoman Empire. But if the status quo “collapsed”, any temporary or permanent occupation of territories in the area should, according to Article VII, “take place only after a previous agreement between the two Powers, based upon the principle of a reciprocal compensation for every advantage, territorial or other.” This article would be part of the renewed and extended versions of the treaty agreed upon in 1902 and 1912. [9] In 1914-1915, Italy would use Article VII to gain leverage in her negotiations with Austria-Hungary over Trentino and Trieste. In the years before, the article kept a lid on Austro-Italian rivalry in Albania . But with Italy seeking British, French and Russian support between 1899 and 1911, the Triple Alliance was no longer essential for Italy’s colonial aspirations in North Africa and in the Eastern Mediterranean. During the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-1912, Rome could count on the tacit support or at least acquiescence of the other Great Powers. As the Ottoman Empire, weakened by the Italian attack on its North African possessions and the ensuing war, came close to collapse in 1912 in its fight against the Balkan League, which had been forged by Russian diplomacy, the Great Powers set up the London conference. The Concert of Europe was meant to contain the shockwaves and to help find viable solutions to territorial disputes when the spoils of war were divided up. The Triple Alliance was renewed for the last time in December 1912, in the wake of the First Balkan War, with tensions between the Great Powers at crisis level. [10]

Although contemporaries were still using the term Triple Alliance, the cabinets in Berlin and Vienna were no longer convinced of Rome’s attachment to the alliance. In Austria-Hungary, suspicions of Italian duplicity were widespread. Rivalry between both allies in the Adriatic and fear of Italian plans to grab Habsburg territory fueled anxieties and inspired military build-up and heavy-handed policing along the border. A naval armaments race between the allies ensued in the early 1900s that would slow down only on the eve of war. By that time, support for the Triple Alliance in Italy’s political elite had waned. Whereas the alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary had been pivotal to Italian efforts to become a modern, respected great power in the 1880s and most of the 1890s, in the early 20 th century, ties to Vienna and Berlin had become a matter of weighing strategic opportunities. [11] Consequently, uncertainties about Italian policy played a significant role in British, French, German and Austro-Hungarian calculations.

Italy was not the only one about to jump ship and seek closer relations with Britain, France, and Russia; Romania was, as well. In both cases, Austria-Hungary stood in the way of the possibility of expanding influence and gaining territories in the Balkans. In the case of Romania, Vienna’s stance during and after the Second Balkan War soured relations. Both in Italy and in Romania, the hope of annexing parts of the Habsburg Monarchy that had a majority population of co-nationals started to gain more traction among publicists and politicians. Fears of such a policy among the political elites in Vienna and Budapest were not without justification, but greatly exaggerated. Nevertheless, those fears fed into a growing sense of instability and imminent threat to the very existence of the Habsburg Monarchy. By 1914, the future of the Triple Alliance seemed to be in question, but many decision-makers in Vienna and in Berlin who started the July Crisis hoped to keep the Triple Alliance – including Romania – together in case of a European war, or at least to be able to count on Italian and Romanian neutrality. Compared to the days of Bismarck’s chancellorship, the German Empire looked more and more isolated in Europe, with only the declining Habsburg Monarchy left as a weak, but reliable ally. [12]

Franco-Russian Alliance and Triple Entente ↑

Until the late 1880s, the French Republic held a rather isolated position among the Great Powers. Colonial disputes with Britain and Italy played a role, but so did the perception of France as a standard-bearer of revolution . Republicanism and revolution were considered deadly threats to Europe in general and to Russia in particular, especially by the tsar and his government . Bismarck had successfully appealed to the tsar’s conservatism in 1873 and did so again in 1881, when Russia, Germany and Austria-Hungary signed treaties that followed the traditions of the Holy Alliance. With the secret Reinsurance Treaty of 1887 between Germany and Russia, [13] Bismarck tried to keep Russia engaged, but a tariff dispute and Germany’s decision to ban the floating of Russian state loans on German markets in 1887 proved counterproductive. After Bismarck’s fall in 1890, the German decision to let the Reinsurance Treaty expire, and the assertive policy of Berlin’s partners in the Eastern Mediterranean in 1891, furthered the alienation between Germany and Russia. French politicians sensed an opening for closer relations with the only strategic partner left on the continent that might help to counter Germany. The detention of Russian anarchists in France made the republic more palatable to the tsar. Financial support was something the French Republic had to offer, but it also had sizable military capabilities. The visit of a French naval squadron to the Russian harbor of Kronstadt 1891 and a Russian return visit to Toulon in 1893 made the realignment public.