Internet Explorer is no longer supported by Microsoft. To browse the NIHR site please use a modern, secure browser like Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, or Microsoft Edge.

£42.7 million funding boost for mental health research

Published: 30 May 2023

A new £42.7 million investment into mental health research has been announced by the NIHR and the Office for Life Sciences.

The new Mental Health Mission (MHM) will develop innovative new treatments and technologies. The Mission will work with patients, NHS staff and clinicians and innovators to make the UK a leading location in which to test and trial new products.

Two Co-Chairs have been appointed:

- Kathryn Abel, Professor of Psychological Medicine and Reproductive Psychiatry at the University of Manchester

- Husseini Manji, Visiting Professor at Oxford and Duke Universities.

Together, they will:

- set the overarching strategic direction

- drive forward its delivery

- build strong, collaborative working relationships across the wider clinical and research communities

- represent the Mission nationally and internationally.

The Mental Health Mission will be delivered via the NIHR’s Mental Health Translational Research Collaboration (MH-TRC) .

This is a network of leading investigators who specialise in mental health research. It is led by Professor John Geddes of the University of Oxford, and Professor Rachel Upthegrove of the University of Birmingham.

Professor Lucy Chappell, Chief Executive of the NIHR, said:

“Mental ill health affects many people. This investment in the Mental Health Mission aims to deliver a truly exciting range of innovative therapies and technologies that could greatly improve people's lives.

"For example, the development of wellbeing apps, games and services to diagnose child mental health problems early could provide valuable new methods of treatment.

"And in the true spirit of collaboration, the work has intentionally been spread across the country so that more people are able to participate in world-leading mental health research than ever before.”

Professor Abel and Professor Manji said:

“We are delighted to be working together to make the new Mental Health Mission a truly revolutionary force behind mental health research. We want the Mission to create tangible differences to the lives of patients, both in the UK and internationally. Between us, we bring a wealth of experience in mental health research and innovation, and a commitment to genuine collaboration with patients, industry and healthcare staff.

"Bringing together the public sector, patients and industry as equal partners, the Mission will work with the Office for Life Sciences and the NIHR to support the NHS and NIHR to capitalise on its size and scope, and on the depth of its data resources. Alongside additional investment in mental health research and infrastructure, the Mission will foster a step change in the way we think about mental health, mental illness and its treatment. This will support development of the critically needed treatments across the spectrum of mental illness.

"We want the UK to be the most attractive place to conduct robust, high impact mental health research, ensuring people have access to the best, and newest, treatments. We are confident that the Mission will be unique in its ability to convene and challenge national partners to make this happen.”

Demonstrator sites

Of the total investment, more than £20 million will go towards establishing demonstrator sites in Birmingham and Liverpool (£9.9m and £10.5m over five years respectively).

The new centre in Liverpool will help people look after their mental health by understanding how mental, physical and social conditions interlink.

The site in Birmingham will support research and the development of novel treatments for:

- early intervention in psychosis, depression and children

- young people suffering from mental ill health.

The remainder of the £42.7m fund will go to UK-wide work focussed on conditions such as depression and early psychosis. It also help to build mental health research capacity in the NHS, and embedding research findings into practice.

The establishment of sites in the Midlands and the North further demonstrates the Government’s commitment to Levelling Up. It will ensure communities across the UK get to take part in, and benefit from research.

The Mental Health Mission is one of the healthcare research priorities announced by the government as part of its Life Sciences Vision. It will take a Vaccine Taskforce style approach to tackling some of the biggest public health challenges facing the UK.

Building on the model which led to one of the most successful vaccine roll outs in the world and ensured millions got a Covid-19 jab, the government will continue to:

- harness world-leading research expertise

- remove unnecessary bureaucracy

- strengthen partnerships

- support the new healthcare challenges.

According to NHS England, one in four adults and one in 10 children experience mental illness. Bolstering research in this area could help millions of people across the country. The mission will engage with industry by eliminating barriers to develop and test new products, attracting additional private investment and cementing the UK as a life sciences superpower.

Read more about the Mental Health Translational Research Collaboration.

Latest news

Blood tests for diagnosing dementia a step closer for UK

NIHR launches new funding stream to support global health researchers

UK-US collaboration continues to support the next generation of cancer research leaders

App can help people reduce their alcohol intake

Handing out vapes in A&E helps smokers quit

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C13'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 1

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C14'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 2

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C15'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 3

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C16'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - year 4

- 1" class="nav-item" v-on:click="getDoc($event, item['0C17'].replaceAll(/ ]*?>/g, ''))"> Progress report - final

1" v-html="item['0C7']">

Supervisor(s):

1">Read 's thesis online at

')" v-html="p">

Project abstract

Project aims, progress report - year 1, progress report - year 2, progress report - year 3, progress report - year 4, progress report - final year, mental health research uk, the first uk charity dedicated to raising funds for research into mental illnesses, their causes and cures., since 2008, we have ....

in scholarships

research students

research publications

Mental Health Research UK aims to make a significant improvement to the lives of people with mental illness, by funding research into causes and cures. We know it is often challenging to find resources to support PhD studentships and that is why we focus our funding on these awards, supporting mental health researchers of the future.

Although only registered with the Charity Commission in 2008, Mental Health Research UK has already made {{scholarshipsFundedCount}} research awards; the first being funded jointly with the University of Nottingham.

Select the sub-headings below to learn more ...

What we fund

We fund research into:

- The underlying causes of mental ill health

- Treatments for mental health problems

We do not fund research into autism or dementia. Nor do we fund research that involves laboratory animals.

Mental Health Research UK has one competitive round of PhD Scholarship awards per year, launched in the spring, for submission in May, with decisions made in the autumn to start the following year. The annual timeline is as follows:

- March: Scholarships are advertised via our mailing list and listed on our website.

- Mid-May: Closing date for applications.

- July: The panel meets and shortlists applications. Those not shortlisted are informed at once. References and service user reports are organized.

- September: Deadline for the receipt of references and service user reports.

- Late September: The panel meets and selects applicants to be offered a scholarship.

- October: All applicants are notified of the outcome of their application by the end of the month.

Research topics

Mental Health Research UK makes research awards focusing on research into the causes of, or cures for, mental illnesses.

The specific research topics of interest are selected year-on-year by the Trustees. However, the Schizophrenia Research Fund John Grace QC PhD Scholarship award always focuses on Schizophrenia.

Our awards cover fees and stipend only and are based on the Medical Research Council’s minimum stipend and fees for UK students, currently as follows:

2023/24 stipend: Outside London: £18,662; Inside London: £20,622

2023/24 fees: £4,712

Funding will cease at 4 years or on submission of the PhD thesis, whichever is earlier.

The fourth year is regarded as a ‘writing up’ year and the grant will be the stipend and thesis fee only.

In the event of early submission, a brief application to retain the student for the remainder of the period within the total cost envelope will be considered. College fees will be considered, where advertised by the university as being in addition to the tuition fee.

Mental Health Research UK will consider a small grant towards travel and conference allowances, where the student is presenting, subject to prior approval. No contribution will be made towards Research Training and Support grants.

If your university fees or stipend are different from the above, we will consider these provided you advise us with your application.

MD(Res) awards

Please note that applications are not currently being considered.

The Trustees of Mental Health Research UK have, since 2018, supported the MD(Res) degree at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience (IOPPN) at King's College, London.

Mental Health Research UK wishes to support young psychiatrists with an interest in mental health research by offering scholarships for this programme because we need to encourage more people to develop careers within academic psychiatry. We are keen to provide a supportive community within Mental Health Research UK for all our scholars, which the MD(Res) award holders will join. This will help doctors thrive in their studies and ensure progress is made towards improving the lives of people with mental health problems, through scientific advances.

Dr Gareth Owen, Chair of the MD(Res) committee, IOPPN said:

"Doctors working in mental health sometimes come to research questions later in their careers with the benefit of clinical experience and training. It is hugely important that their experience and research energy is tapped and academic awards make a real difference to enabling such innovation. These awards from MHRUK are an excellent way to bring clinical experience and high quality research supervision together to foster an exciting new cohort of clinical academics in mental health."

Eligibility

Applications for our awards need to come from UK universities. Research supervisors must be based at UK universities.

We accept one application per scholarship award from any one university. A university may apply for more than one scholarship if they wish.

Please note that we do not accept any requests for funding from individuals, including current PhD students.

User and carer involvement

Best practice will be followed to ensure that service users and carers are involved at all stages with the prioritization of research topics and the commissioning of research.

All research project applications will be peer-reviewed by service user reviewers as well as academic reviewers.

NIHR and NHS information

Mental Health Research UK is a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) non-commercial Partner . This means the studies that we fund may be eligible to access the NIHR Study Support Service which is provided by the NIHR Clinical Research Network. The NIHR Clinical Research Network can now support health and social care research taking place in non-NHS settings, such as studies running in care homes or hospices, or public health research taking place in schools and other community settings. Read the full policy: Eligibility Criteria for NIHR Clinical Research Network Support . In partnership with your local R&D office, we encourage MHRUK award holders to involve your local NIHR Clinical Research Network team in discussions as early as possible when planning your study. This will enable you to fully benefit from the support available through the NIHR Study Support Service.

If your study involves NHS sites in England or Wales you will need to apply for Health Research Authority (HRA) and Health and Care Research Wales (HCRW) Approval .

Open Access publication of research results

Students can download our application form for open access publication of research results here .

PhD Competition {{ ' ' + scholarshipsAvailableYear}}

Mental Health Research UK (incorporating the Schizophrenia Research Fund) is pleased to announce a competition for {{scholarshipsAvailableCount}} PhD Scholarship s beginning September {{scholarshipsAvailableYear}} .

Please note that our PhD scholarship competition is currently closed

We are inviting applications for PhD scholarships under the theme of maternal mental health . We view this topic in its broadest sense inviting proposals that cover all aspects of mental health during pregnancy and in the first year afterwards. We are interested in proposals that aim to understand causes, risk factors, mechanisms, or treatments. MHRUK does not fund health services research.

{{ item['0C0'] + ' ' + item['0C3'] + ': ' + item['0C1']}}

{{item['0C2']}}

We invite applications from UK Universities for these scholarships. The deadline for applications is {{item['0C6']}} .

The full terms and conditions can be found here .

If you have any queries regarding the application process, please read the guidance above and check our FAQs document . If this does not provide the information that you need, please contact [email protected] .

Please note that for each individual scholarship we can accept only one application per university. A university may apply for more than one scholarship if they wish.

Scholarships Awarded

Find out more about the scholarships that we have awarded..

Use the buttons below to filter the list.

1" span v-html="item['0C7']">

Select from the tags below to filter by topic:

Mental Health Research Matters

Funding Opportunities

External – funding opportunities beyond the UKRI Networks

If you’re looking for mental health research funding opportunities, this is a great place to start. See below for a list of funders for mental health research. UKRI – Find the latest funding opportunities from UK Research and Innovation, including mental health. Look out for opportunities from the MRC, and even the EPSRC. NIHR –...

Emerging Minds

In 2021/22, Emerging Minds are focusing particularly on their ‘Big Question Research challenge’ which was identified as a priority in our original consultation workshops with stakeholders.

Violence, Abuse and Mental Health

There are no open funding opportunities for VAMHN network at the moment. Early Career Researcher Bursary Awards The network is delighted to launch another round of the Early Career Researcher (ECR) Training Bursary Scheme, which aims to support junior researchers to attend training courses, research placements at institutions other than their own, and conferences. Applicants...

Closing the Gap

Closing the Gap launched The Impact Accelerator Award, their final funding call, on 27th September 2021.

The aim of the call is to provide support for knowledge mobilisation activities and impact that address the challenge of reducing the health gap for people with experience of severe mental-ill health.

No open funding calls Previous funding calls SMaRteN are pleased to invite proposals for research projects to address student’s key questions about student mental health. Funding is available as part of the UKRI ‘plus’ funding scheme for Mental Health Networks. The deadline for proposals is 17:00 on the 14th of April 2021 This funding call...

MARCH: Social, Cultural and Community Assets for Mental Health

No open funding calls Previous funding calls Second funding round (closed) The MARCH Network’s second round of funding closed on Sunday 31st May 2020. Four projects which answered one of two specific high-priority questions were selected for larger investment of £50K, along with three projects addressing two broader priority questions for innovation grants of £20K,...

eNurture’s final funding round is now closed. eNurture’s third and final funding call is now live. The network is looking to fund research within the following thematic areas: A Focus on Families: The Digital World A Focus on Schools/Peers: The Digital World New Practice Models: Families and Schools Policy, Legal and Regulatory Frameworks Key dates:...

No open funding calls Previous funding calls The TRIUMPH Network plus-funding call for research projects closed in July 2020. They are delighted to announce that grants have been awarded to support the following projects that will start from October 2020. Co-production or adaptation of online interventions for foster care: Promoting the mental health and wellbeing...

Loneliness and Social Isolation Network

No open funding calls Previous funding calls October 2020 – Up to £50K was available from the Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health network as part of their second funding call on interventions. Grants were available for £15K and £50K for small or large projects respectively, provided at 80% of full economic costing. For...

Privacy Overview

Funding opportunity: MRC neurosciences and mental health research grant: Sep 2021

Funding is available from MRC’s Neurosciences and Mental Health Board to support focused research projects on neurosciences and mental health.

We award research grants to UK-based research organisations, and research grants may involve more than one research group or institution.

There is no limit to the funding you can request, but it should be appropriate to the project. Typically awards are up to £1 million. We will usually fund up to 80% of your project’s full economic cost.

Projects can last up to five years and are typically 3-4 years.

Who can apply

Any UK-based researcher with an employment contract at an eligible research organisation can apply. You will need to:

- have at least a graduate degree, although we usually expect most applicants to have a PhD or medical degree

- show that you will direct the project and be actively engaged in the work.

You can include one or more industry partners as project partners in your application. International co-investigators can be included if they provide expertise not available in the UK.

The focus of this funding opportunity is neurosciences and mental health research. There are similar opportunities across other areas of medical research within our remit , including molecular and cellular medicine, infections and immunity, population and systems medicine, and applied global health. There are also other types of awards including programmes, partnerships and new investigator.

You should contact us if you are not sure which opportunity to apply to.

What we're looking for

The MRC’s Neurosciences and Mental Health Board funds research in neurosciences, mental health and disorders of the human nervous system. We aim to transform our understanding of the physiology and behaviour of the human nervous system throughout the life course in health and in illness, as well as how to treat and prevent disorders of the brain.

The research we support includes the interactions between the nervous system and other parts of the body – the brain, mental health and physical health. We are also interested in how episodes throughout life impact on lifelong mental and neurological health.

Research we fund includes, but is not limited to, the following areas:

- neurodegeneration

- clinical neurology and neuroinflammation

- mental health

- addictions and substance misuse

- behavioural and learning disorders including autism

- cognitive and behavioural neuroscience and cognitive systems

- sensory neuroscience including vision and hearing

- neurobiology and neurophysiology

- underpinning support – such as neuroimaging technology, brain banking and neuroinformatics

Find out more about science areas we support and our current board opportunity areas .

We encourage you to contact us first to discuss your application, especially if you believe your research may cross MRC research board or research council interests. If your application fits another research board remit better we may decide to transfer it there to be assessed.

Medical Research Council neurosciences and mental health research grants:

- are suitable for focused short or long-term research projects

- can support method development or development and continuation of research facilities

- may involve more than one research group or institution.

We will fund projects lasting up to five years, although projects typically last 3 to 4 years. If your project will last more than three years, you must justify the reason for this; for example, if you need time for data collection or follow-up.

If your project will last less than two years, it must be for proof of principle or pilot work only. We expect proof of principle proposals to support high-risk or high-reward research by critically testing a key hypothesis or demonstrating feasibility of an approach that could lead to fundamentally new avenues of research.

Contact one of our programme managers for advice if you would like to apply for a short or long-duration project.

You can request funding for costs such as:

- a contribution to the salary of the principal investigator and co-investigators

- support for other posts such as research and technical

- research consumables

- travel costs

- data preservation, data sharing and dissemination costs

- estates/indirect costs.

We won’t fund:

- research involving randomised trials of clinical treatments

- funding to use as a ‘bridge’ between grants

- costs for PhD studentships

- publication costs.

How to apply

Application deadlines for Neurosciences and Mental Health Board funding are usually around January, May and September/October, although sometimes dates can change, so check the Funding finder for details.

You can submit to any of the available deadlines in the year. We do not expect you to submit more than two applications at the same time and encourage you to focus on application quality, not the number you can submit. Read our guidance for applicants for details of our resubmission process .

Applying through Je-S

You must apply through the Joint Electronic Submission system (Je-S) . Please read the Je-S how to apply guidance (PDF, 190KB) for more information. If you need help applying, you can contact Je-S on 01793 444164 or by email [email protected] .

You should give your administrative department at least two weeks’ notice that you intend to apply. You must submit your application before 4pm on the deadline date.

When applying select:

● council: MRC ● document type: standard proposal ● scheme: research grant ● call/type/mode: research boards Sep 2021 submissions

Indicating the proposal is a research grant

Select the ‘grant type’ option from the proposal document menu, within the Je-S proposal form. Within the section, select the radio button adjacent to the ‘research grant’ option and select the ‘save’ button.

Guidance for applicants

Our guidance for applicants will:

- help you check your eligibility

- guide you through preparing a proposal

- show you how to prepare a case for support

- provide details of any ethical and regulatory requirements that may apply.

Industrial partners

If you want to include one or more industry partners as a project partner, you must also:

- complete the project partner section in Je-S

- submit an MRC industrial collaboration agreement (MICA) form and heads of terms

- include ‘MICA’ as a prefix to your project title.

Find out more about MRC industry collaboration agreements .

Longitudinal population studies

If your application is to fund new or existing longitudinal population studies, you must first submit an outline application for joint review by the Longitudinal Population Studies Strategic Advisory Panel and the Research Board. Should a full application be invited, this may be submitted within a 12-month window.

Applications for longitudinal population studies must be for core infrastructure only, applications may include associated research only if it is for proof of principle work.

Applicants must speak to the relevant programme manager at least 6 weeks before the outline submission deadline to confirm the eligibility of their application.

Please email [email protected] for the outline template, timeline for review and next outline submission deadline. Applications for funding for clinical (meaning, patient-specific or disease-focused) cohorts are exempt from this process.

How we will assess your application

When we receive your application, it will be peer-reviewed by independent experts from the UK and overseas.

You can nominate up to three independent reviewers. We will invite only one to assess your application, and may decide not to approach any of your nominated reviewers.

Peer reviewers will assess your application and provide comments. They will also score it using the peer reviewer scoring system against the following criteria:

- importance: how important are the questions, or gaps in knowledge, that are being addressed?

- scientific potential: what are the prospects for good scientific progress?

- resources requested: are the requested funds essential for the work? And do the importance and scientific potential justify funding on the scale requested? Does the proposal represent good value for money?

Read the detailed assessment criteria for each grant type .

We will review these scores and comments at a triage meeting and expect to continue with the highest-quality applications with potential to be funded. If your application passes the triage stage, we will give you the chance to respond to reviewers’ comments.

A board meeting will then discuss your proposal and decide if it is suitable for funding. We make a decision within six months of receiving your application.

Find out more about our peer review process .

Contact details

Visit our science contacts page or contact the programme manager most relevant to your research area for advice on developing your application and which board to apply to:

- head of programme – mental health: Dr Karen Brakspear – [email protected]

- programme manager for cognition and developmental disorders: Dr Charlotte Inchley – [email protected]

- programme manager for neuronal function: Dr Simon Fisher – [email protected]

- programme manager for neurodegeneration: Dr Clara Fons – [email protected]

- programme manager for pain and addiction: Dr Siv Vingill – [email protected]

- programme manager for neurological disorders: Dr Steph Migchelsen – [email protected]

- programme manager for adolescent mental health: Dr Victoria Swann – [email protected]

Other contacts

- for queries about submitting your application using Je-S, email [email protected] or call 01793 444164

- for general enquiries about your application contact [email protected]

For general queries about MRC policy and eligibility or if you are not sure who to contact, get in touch with our research funding policy and delivery team:

- [email protected]

- 01793 416440

Additional info

Supporting documents.

- Je-S how to apply guidance (PDF, 190KB)

This is the website for UKRI: our seven research councils, Research England and Innovate UK. Let us know if you have feedback or would like to help improve our online products and services .

Header menu - Mobile | United Kingdom

Header menu - drawer | united kingdom, investment into mental health research: statistics.

In recent years, there has been an acknowledgement that mental health research is significantly below the equivalent of physical health.

As measured by Years Lived with Disability, mental disorders account for at least 21% of the UK disease burden 1 , although further research suggests this has been underestimated by at least a third. 2 In 2018, only 6.1% of the UK’s health research budget was spent on mental health 3 and funding has remained largely unchanged for a decade. 4

There have been recent boosts to mental health research; for example, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) and the NIHR have announced a new £30 million Mental Health Research Initiative in 2021 5, and in May 2023, a new £42.7 million investment into mental health research has been announced by the NIHR and the Office for Life Sciences. 6

But the Royal College of Psychiatrists have stated that “We urgently need more funding for mental health research. If we’re serious about treating mental and physical health equally, funding for mental health research needs to increase exponentially.” 7

GBD results

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171-178.

UK Clinical Research Collaboration. UK Health Research Analysis 2018. January 2020.

MQ. UK Mental Health Research Funding 2014–2017. 2017

£30 million investment to rebalance the scale of mental health research

£42.7 million funding boost for mental health services

RCPsych supports Government funding for research into severe mental illness

See all mental health statistics

Was this content useful?

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Mental illness costs England £300bn a year, study shows

Yearly cost to people, business and public sector found to be twice as big as NHS England’s annual budget

Mental illness costs England £300bn a year, equivalent to nearly double its NHS budget, according to research.

Researchers for the Centre for Mental Health thinktank analysed the economic, health and care impact of mental ill health, as well as human costs from reduced quality of life and wellbeing.

The report , commissioned by the NHS Confederation’s mental health network, calculated that in 2022, mental illness cost £130bn in human costs, £110bn in economic costs and £60bn in health and care costs.

The £300bn cost in 2022 equates to nearly double the NHS’s entire £153bn budget in England in the same year and is a “comparable impact, economically, to having a pandemic every year”, the report concludes.

The greatest financial impact, £175bn, falls on people living with mental health difficulties and their families, while the public sector incurs £25bn and business £101bn.

For the first time, the report also assessed some wider financial impacts of mental illness such as presenteeism, staff turnover and lost tax revenues from economic inactivity.

The authors calculate that presenteeism – where someone is less productive at work due to impaired cognitive function and emotional distress caused by their mental ill health – cost £41.8bn, while staff turnover due to mental illness cost £43.1bn and lost tax revenues cost £5.7bn.

The report concludes that even the £300bn is likely to be a significant underestimate. If other impacts of mental ill health were included, such as the £10bn to £16bn cost of physical and mental health comorbidities and the £2.1bn cost of mental ill health in prisons, the total would be even higher.

The figures underline the scale of the mental health crisis. Referrals to NHS mental health services in England rose 44% between 2016-17 and from 4.4m to 6.4m in 2021-22, while the number of people in contact with mental health services rose from 3.6 million to 4.5 million during that same period, the National Audit Office calculated.

According to the Department of Health and Social Care, mental health accounts for just 9% of NHS spending despite taking up 23% of the “burden of disease”.

In 2002 the estimated cost of mental ill health in England was £76.3bn. Further analysis of the figures suggests that even accounting for inflation and stripping out any costs in the 2022 figures not included in the 2002 figure, there has been a 40% increase in the cost of mental illness in England in the past two decades.

Andy Bell, the chief executive of the Centre for Mental Health, said ministers “cannot afford to ignore the devastating impact of mental ill health”, adding: “A pound sign can never fully reflect the suffering caused by mental ill health.

“Rising inequality, austerity and cuts to early support have contributed to a nation with overall poorer mental health, and have led to more people reaching crisis point before they get support.”

The NHS Confederation’s mental health network chief executive, Sean Duggan, reiterated the call for action from ministers, saying: “The false economy of failing to invest in mental health is making the country poorer and causing unspoken anguish to so many people and their loved ones. It is vital that we now invest in effective interventions that bring us closer to a mentally healthier nation for all.”

Wes Streeting, the shadow health secretary, said: “The failure of the Conservatives to support people out of lockdown, in particular young people who have felt the effects worse than most, has stored up huge problems for our society, economy and the public finances.”

Brian Dow, the deputy chief executive of Rethink Mental Illness, called mental ill health rates “one of the greatest challenges of the 21st century”.

The report’s release came as a coalition of leading health organisations signed a joint letter urging Victoria Atkins, the health secretary, to take “urgent steps” to protect the mental health and wellbeing of health and care staff as specialist hubs “continue to close”.

Ringfenced funding for NHS mental health and wellbeing hubs was cut a year ago, the organisations said, and as a result, staff in need of support face a “postcode lottery” of care. Of the original 40 hubs, 18 have closed since March 2023, they said.

A government spokesperson said: “We’ve increased spending on mental health by £4.7bn since 2018/19, to support even more people.

“We are also continuing to roll out mental health support teams in schools and colleges, investing £8m in 24 early support hubs and expanding talking therapies services so people get help early on with their mental health.”

- Mental health

Police in England must keep answering mental health calls, charity urges

20,000 people off work in the UK every month for mental ill health

People in 20s more likely to be out of work because of poor mental health than those in early 40s

Children’s emergency mental health referrals in England soar by 53%

Early release of mental health patients in England presents suicide risk, report finds

UK homeowners with mental health problems ‘spend less on essentials to pay mortgage’

Experts call for fewer antidepressants to be prescribed in UK

Third of UK carers with poor mental health have thoughts of suicide, survey finds

Most viewed.

Cookies on GOV.UK

We use some essential cookies to make this website work.

We’d like to set additional cookies to understand how you use GOV.UK, remember your settings and improve government services.

We also use cookies set by other sites to help us deliver content from their services.

You have accepted additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

You have rejected additional cookies. You can change your cookie settings at any time.

- Education, training and skills

- Senior mental health lead training grant funding

- Education & Skills Funding Agency

Senior mental health lead training: conditions of grant for the 2024 to 2025 financial year

Updated 2 April 2024

Applies to England

© Crown copyright 2024

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] .

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/senior-mental-health-lead-training-grant-funding/senior-mental-health-lead-training-conditions-of-grant-for-the-2024-to-2025-financial-year

1. Introduction

The Department for Education ( DfE ) is offering a grant of £1,200 in the 2024 to 2025 financial year for eligible state-funded schools and colleges to train a senior mental health lead.

We encourage eligible settings that want to develop, or introduce, their whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing to apply for a grant. You must identify a senior mental health lead who can begin training by 31 March 2025.

The government remains committed to offering senior mental health lead training to all eligible state-funded schools and colleges by 2025.

2. Purpose of the senior mental health lead training grant

We will provide grants to cover, or contribute towards, the cost of DfE quality assured training for a senior member of school or college staff to train as the ‘senior mental health lead’ for that setting. The training will develop the knowledge and skills to implement an effective whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing in that setting.

All eligible education settings can benefit from this training, and courses are available to meet a variety of learning needs and preferences of senior leads depending on their level of experience, type of setting or location.

3. Grant allocation and eligibility

Each eligible setting that successfully submits both stages of the application process will receive a fixed grant of £1,200 to train a senior mental health lead who will be expected to implement and sustain an effective whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing.

Eligible schools and colleges that claimed a grant in a previous financial year can claim a second £1,200 grant if the senior mental health lead they previously trained left their setting before embedding a whole school or college approach.

4. Eligible settings

All state-funded education settings receiving Education and Skills Funding Agency ( ESFA ) pre-16 revenue, high needs block or 16 to 19 programme funding are eligible for the grant, including:

- mainstream academies and local authority maintained schools

- special academies and local authority maintained special schools (including alternative provision)

- independent special schools whose pupils’ education is funded by their local authority

- further education ( FE ) colleges attended by under-18-year-olds (one claim per campus ID)

- sixth-form colleges

- special post-16 institutions

- non-maintained special schools

- local authorities

- independent training providers

Grant applications can only be submitted by individual settings. Settings within a multi-academy trust must claim individually. Distinct institutions (with a DfE campus ID) within larger FE colleges will each be eligible for a training grant.

Some independent alternative provision settings will be eligible for a grant if the majority of their pupils are funded by the local authority.

4.1 Who is not eligible

Independent institutions (with fee-paying pupils and students) that do not receive the funding types outlined above are not eligible for a grant. Ineligible settings can still access DfE quality assured training courses independently.

This training grant is not available for leaders of early years settings. The department has published a mental health and wellbeing resource article on the Help for early years providers platform on GOV.UK.

If you believe you are eligible, but are experiencing application issues, contact us at [email protected] .

5. Terms on which the grant is allocated to eligible schools and colleges

5.1 before you submit your grant claim.

- have the commitment of your school or college senior leadership team to implement a whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing in your setting

- have identified a senior mental health lead, ready to start training by 31 March 2025, and oversee your setting’s whole school or college approach

You should read the accompanying guidance and reflect on the learning outcomes for the training .

When you apply for the grant, you will be asked to declare that these terms are met.

5.2 Permissible spend

The grant must be used to pay for DfE quality assured senior mental health training, to develop the knowledge and skills necessary to implement and sustain an effective whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing in a setting. It will be paid as stated in section 14 of the Education Act 2002 .

You can view the full published list of DfE quality assured courses .

Any element of the grant not spent on a DfE quality assured course can then be used:

- for supply cover for the senior mental health lead, should a school or college need to backfill a senior lead while undertaking training

- to fund further training, activity or resources that support the development of a senior mental health lead, and contribute to the implementation of an effective whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing in a setting

Further training, activity or resources may include:

- additional courses or coaching that support the further development of the senior mental health lead, enabling them to establish, implement or sustain a whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing

- external support to assess your existing school or college approach to promoting and supporting mental health, to identify strengths, weaknesses and areas for improvement

- online resources and toolkits that support the senior lead, or other staff, to embed, sustain or, otherwise, improve the effectiveness of their whole school or college approach to mental health and wellbeing (many resources are available for free)

- other activities by the senior lead within their setting that focus on raising wider awareness and understanding of their whole school or college approach to better promote and support mental health (for example, promotion materials or awareness sessions for education staff)

We do not consider the following expenditure as falling within the scope of further activity:

- employing counsellors or other professional individuals or groups to provide specific social, emotional or mental health interventions for children and young people

5.3 Applying for a grant

You can now apply for a grant if you are able to begin training by 31 March 2025.

Follow these steps to apply:

Complete application form 1 to reserve a grant. This form checks your eligibility. You will be asked to make a series of declarations as described in these conditions of grant.

You will receive confirmation that we have successfully received your application. This will tell you to book a DfE quality assured training course that must start by 31 March 2025. Keep evidence of your booking as you need this when you submit application form 2.

You must submit application form 2 to upload your booking evidence and claim your grant.

The second form asks you to provide evidence you have booked a quality assured course. This can be a scanned copy, screenshot or photograph of your confirmation email or invoice from your training provider. You should ensure that your evidence includes:

- title of the training course

- name of the training provider

If you are applying for a second grant, make sure you ‘tick’ the declaration to confirm your previous senior mental health lead has left. We will not pay your grant if you do not confirm this.

You will have up to 3 weeks to submit the second form. If you do not submit within 3 weeks, we may release your place to applicants on our waiting list.

5.4 When you will be paid

Once you have submitted evidence of your course booking in application form 2, we will review the information provided. We will email you to let you know we have approved your application and confirm when your grant will be paid.

We will make payments on a quarterly basis. When you receive your grant will depend on when you complete the second stage of your application.

Most settings will get their payments on the last working day of:

- September 2024

- December 2024

Academies will get their payments on the first working day of:

- October 2024

- January 2025

Maintained schools and maintained alternative provision settings will receive payment via their local authority. All other settings will receive payment directly. We will make this payment alongside your regular funding and it will appear as a separate line on that remittance.

We will provide local authorities with a breakdown of which schools to pass funding to. Maintained schools and settings should contact their local authority if they have not received their funds.

6. How we will use the data you provide

DfE will collect and use the data submitted through the online forms to compile aggregate statistical information for developing and measuring the impact of the service; and for the purposes of satisfying any legal, accounting or reporting requirements.

When applying for a grant, we will ask you to confirm that you will provide feedback on your training when contacted by DfE .

Your school or college will also be included on a list of published grant claims .

7. Record keeping

You should retain records to show that the grant has been used for the intended purposes for 6 years after the end of the financial year in which the expenditure has taken place.

The books and records of the school or college claiming the grant are open to inspection by the National Audit Office and our representatives.

We may request further information to determine if your school or college has complied with these conditions of grant.

Failure to provide this information may result in the whole or part of the grant paid being recouped.

8. Other terms

You must inform us if your senior mental health lead is unable to complete the training or meet the other terms of this grant.

We reserve the right to withhold payment or seek reimbursement of payments already made if we consider that you have:

- not spent the funding in accordance with this agreement

- breached any other terms of this agreement

- provided false or incorrect statements or information in your funding claim

The school or college will be informed of the above, in writing, along with the sum that immediately becomes payable, by the school or college, back to DfE .

9. Further information

If you have a query about the grant or eligibility criteria which is not covered in these terms and conditions or the guidance below, please contact us using our customer help centre .

Use the links below to find out more about:

- senior mental health lead training

- promoting and supporting mental health and wellbeing in schools and colleges

Is this page useful?

- Yes this page is useful

- No this page is not useful

Help us improve GOV.UK

Don’t include personal or financial information like your National Insurance number or credit card details.

To help us improve GOV.UK, we’d like to know more about your visit today. We’ll send you a link to a feedback form. It will take only 2 minutes to fill in. Don’t worry we won’t send you spam or share your email address with anyone.

Institute of Mental Health Research

The History, Present & Future of LGBTQ+ Mental Health

- Date and time: Wednesday 21 February 2024, 3pm to 4.45pm

- Location: PS/A/202, Lecture Room (Venables Room), Psychology Building, Campus West, University of York ( Map )

- Audience: Open to staff, students, the public

- Admission: Free admission, booking not required

Event details

Three invited speakers will give short talks considering the historical context of LGBTQ+ mental health, the inequalities in mental health faced by these communities today, and how we can improve treatment in the future. This will be followed by a panel discussion drawing on our speakers’ experiences researching the mental health of LGBTQ+ people, working with these groups clinically, and teaching future clinicians to reflect on their practice. These discussions will be relevant to everyone, including LGBTQ+ staff and students and their personal supervisors, as well as those who aim to work clinically, assessing and improving mental health with diverse sexualities and genders.

Dr. Qazi Rahman , Co-director of the LGBT Mental Health Research Group, King's College London

Dr. Ruth Knight , Lecturer, York St Johns

Dr. Miles Rogish , University of York & York House Acquired Brain Injury Service

Note: The University of York is committed to making its events as welcoming and inclusive as possible. Please let us know in advance if you have any accessibility requirements , either by emailing [email protected] or calling 01904 325264: we will make every effort to accommodate your needs.

Venue details

- Wheelchair accessible

Rebecca Jackson

Charity funders of mental health research

Where can I find out about potential charity funding for my study? If you aren’t a well-established researcher, it can be very difficult to know where to start. Even if you are, mental health remains an underfunded area with far fewer charities with either open or themed calls compared to other health conditions. But there are starting points. We worked with Vanessa Pinfold, Chair of the Alliance for Mental Health Funders and Director of the McPin Foundation, on this guide to help mental health researchers navigate a tricky and sparse funding landscape.

The Alliance of Mental Health Research Funders is a consortium of 17 charities with a strong interest in mental health research. The members can broadly be categorised using three groups:

Mental health research funders (sole interest)

Mental Health Research UK (MHRUK) and MQ are both charities whose primary aim is to fund mental health research. They were both set up about 10 years ago. Everything they do is structured around the importance of mental health research and raising funds to invest in new programmes of research.

MHRUK has a PhD scholarship programme with calls for applications once a year – they are often themed calls such as children and young people’s mental health or schizophrenia research. MQ invests every year into new research including an MQ Fellows Award scheme. The MQ Fellows Award supports early career scientists who are asking challenging questions that will contribute to transformative advances in mental health research. The next MQ Fellows Awards round launches in Feb 2022 on the theme of preventing early death. A newer charity in Scotland is called Miricyl with a focus on digital solutions for young people and their family and carers affected by mental illness. There are some charities, often set up in memory of a family member who died that focus on one aspect of mental health research including Orchard OCD that have calls for proposals every two years and The Foundation for Young People’s Mental Health (YPMH) which focuses on supporting the translation of research into innovations in practice and policy. Both work with specific academic teams as well as issuing general research calls. Other research charities with a focus on a particular condition, for example Autistica , which focuses on autism, are health research charities which fund mental health as part of their portfolio.

Mental health research funding is one aspect of their work (and often a very small part).

There are quite a few charities in this group. Some issue commissions to evaluate work being undertaken internally such as Mind , the Samaritans , Mental Health Foundation , and NSPCC as well as research projects on specific topics. They tend to issue a tender specification and have to respond and are scored against set criteria. There are also charities who fund research alongside policy, training and campaigning activities. This can be funding a professorship position such as Charlie Waller Trust , or funding occasional PhD students as in McPin Foundation . The British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy (BACP) occasionally provides financial support for students undertaking PhD research in counselling and psychotherapy, and offers bursaries and award schemes to help support researchers who are contributing to the evidence-base for the counselling professions. Other institutions such as the Maudsley Charity fund a mix of mental health research and non-research projects. It aims to have national impact but its primary focus is South London.

Mental health research funder allies

There are charities whose work relies on research, who help champion the importance of mental health research and may themselves occasionally fund research activities. From our Alliance this includes the Centre for Mental Health where research is a major part of their own activities, and Bipolar UK .

“There is no equivalent of CRUK or BHF for mental health. I think the bottom line is very few charity mental health funders have open funding calls. But they do have calls from time to time so it’s a good idea to sign up to their newsletters and follow them on twitter”.

Funding calls

Overall, it’s worth making links and keeping an eye on the charity sector as organisations do issue one off calls and new charities set up – such as the Prudence Trust which focuses on young people’s mental health including research for invited applicants. It’s also a good idea to get on the mailing lists so you make sure you hear about the opportunities as soon as they arise.

Mental Health Research UK charity - annual PhD scholarship programme

MQ mental health charity - MQ fellows applications launches in February 2022

Foundation for Young People's Mental Health

Orchard OCD

Mental Health Foundation

Charlie Waller Trust

McPin Foundation

British Association of Counselling and Psychotherapy

Maudsley Charity

Newsletter sign up

By clicking sign up I confirm that I have read and agree with the privacy policy

The use and impact of surveillance-based technology initiatives in inpatient and acute mental health settings: A systematic review

- Find this author on Google Scholar

- Find this author on PubMed

- Search for this author on this site

- ORCID record for Jessica L. Griffiths

- For correspondence: [email protected]

- ORCID record for Katherine R. K. Saunders

- ORCID record for Una Foye

- ORCID record for Anna Greenburgh

- ORCID record for Antonio Rojas-Garcia

- ORCID record for Brynmor Lloyd-Evans

- ORCID record for Sonia Johnson

- ORCID record for Alan Simpson

- Info/History

- Supplementary material

- Preview PDF

Background: The use of surveillance technologies is becoming increasingly common in inpatient mental health settings, commonly justified as efforts to improve safety and cost-effectiveness. However, the use of these technologies has been questioned in light of limited research conducted and the sensitivities, ethical concerns and potential harms of surveillance. This systematic review aims to: 1) map how surveillance technologies have been employed in inpatient mental health settings, 2) identify any best practice guidance, 3) explore how they are experienced by patients, staff and carers, and 4) examine evidence regarding their impact. Methods: We searched five academic databases (Embase, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, PubMed and Scopus), one grey literature database (HMIC) and two pre-print servers (medRxiv and PsyArXiv) to identify relevant papers published up to 18/09/2023. We also conducted backwards and forwards citation tracking and contacted experts to identify relevant literature. Quality was assessed using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. Data were synthesised using a narrative approach. Results: A total of 27 studies were identified as meeting the inclusion criteria. Included studies reported on CCTV/video monitoring (n = 13), Vision-Based Patient Monitoring and Management (VBPMM) (n = 6), Body Worn Cameras (BWCs) (n = 4), GPS electronic monitoring (n = 2) and wearable sensors (n = 2). Twelve papers (44.4%) were rated as low quality, five (18.5%) medium quality, and ten (37.0%) high quality. Five studies (18.5%) declared a conflict of interest. We identified minimal best practice guidance. Qualitative findings indicate that patient, staff and carer perceptions and experiences of surveillance technologies are mixed and complex. Quantitative findings regarding the impact of surveillance on outcomes such as self-harm, violence, aggression, care quality and cost-effectiveness were inconsistent or weak. Discussion: There is currently insufficient evidence to suggest that surveillance technologies in inpatient mental health settings are achieving the outcomes they are employed to achieve, such as improving safety and reducing costs. The studies were generally of low methodological quality, lacked lived experience involvement, and a substantial proportion (18.5%) declared conflicts of interest. Further independent coproduced research is needed to more comprehensively evaluate the impact of surveillance technologies in inpatient settings, including harms and benefits. If surveillance technologies are to be implemented, it will be important to engage all key stakeholders in the development of policies, procedures and best practice guidance to regulate their use, with a particular emphasis on prioritising the perspectives of patients.

Competing Interest Statement

AS and UF have undertaken and published research on BWCs. We have received no financial support from BWC or any other surveillance technology companies. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Clinical Protocols

https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=463993

Funding Statement

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Policy Research Programme (grant no. PR-PRU-0916-22003). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. ARG was supported by the Ramon y Cajal programme (RYC2022-038556-I), funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities.

Author Declarations

I confirm all relevant ethical guidelines have been followed, and any necessary IRB and/or ethics committee approvals have been obtained.

I confirm that all necessary patient/participant consent has been obtained and the appropriate institutional forms have been archived, and that any patient/participant/sample identifiers included were not known to anyone (e.g., hospital staff, patients or participants themselves) outside the research group so cannot be used to identify individuals.

I understand that all clinical trials and any other prospective interventional studies must be registered with an ICMJE-approved registry, such as ClinicalTrials.gov. I confirm that any such study reported in the manuscript has been registered and the trial registration ID is provided (note: if posting a prospective study registered retrospectively, please provide a statement in the trial ID field explaining why the study was not registered in advance).

I have followed all appropriate research reporting guidelines, such as any relevant EQUATOR Network research reporting checklist(s) and other pertinent material, if applicable.

Data Availability

The template data extraction form is available in Supplementary 1. MMAT quality appraisal ratings for each included study are available in Supplementary 2. All data used is publicly available in the published papers included in this review.

View the discussion thread.

Supplementary Material

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word about medRxiv.

NOTE: Your email address is requested solely to identify you as the sender of this article.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

- Google Plus One

- Addiction Medicine (316)

- Allergy and Immunology (617)

- Anesthesia (159)

- Cardiovascular Medicine (2276)

- Dentistry and Oral Medicine (279)

- Dermatology (201)

- Emergency Medicine (370)

- Endocrinology (including Diabetes Mellitus and Metabolic Disease) (798)

- Epidemiology (11573)

- Forensic Medicine (10)

- Gastroenterology (678)

- Genetic and Genomic Medicine (3575)

- Geriatric Medicine (336)

- Health Economics (616)

- Health Informatics (2304)

- Health Policy (913)

- Health Systems and Quality Improvement (863)

- Hematology (335)

- HIV/AIDS (752)

- Infectious Diseases (except HIV/AIDS) (13149)

- Intensive Care and Critical Care Medicine (755)

- Medical Education (359)

- Medical Ethics (100)

- Nephrology (388)

- Neurology (3346)

- Nursing (191)

- Nutrition (506)

- Obstetrics and Gynecology (651)

- Occupational and Environmental Health (645)

- Oncology (1756)

- Ophthalmology (524)

- Orthopedics (209)

- Otolaryngology (284)

- Pain Medicine (223)

- Palliative Medicine (66)

- Pathology (437)

- Pediatrics (1001)

- Pharmacology and Therapeutics (422)

- Primary Care Research (406)

- Psychiatry and Clinical Psychology (3058)

- Public and Global Health (5983)

- Radiology and Imaging (1221)

- Rehabilitation Medicine and Physical Therapy (714)

- Respiratory Medicine (811)

- Rheumatology (367)

- Sexual and Reproductive Health (350)

- Sports Medicine (316)

- Surgery (386)

- Toxicology (50)

- Transplantation (170)

- Urology (142)

- Open access

- Published: 03 April 2024

Women’s experiences of attempted suicide in the perinatal period (ASPEN-study) – a qualitative study

- Kaat De Backer ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5202-2808 1 ,

- Alexandra Pali ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0009-5817-156X 1 , 2 ,

- Fiona L. Challacombe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3316-8155 3 ,

- Rosanna Hildersley ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1850-6101 3 ,

- Mary Newburn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9471-0908 4 ,

- Sergio A. Silverio ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7177-3471 5 , 6 ,

- Jane Sandall ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2000-743X 1 ,

- Louise M. Howard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9942-744X 3 &

- Abigail Easter ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4462-6537 1

BMC Psychiatry volume 24 , Article number: 255 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

122 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

Suicide is a leading cause of maternal death during pregnancy and the year after birth (the perinatal period). While maternal suicide is a relatively rare event with a prevalence of 3.84 per 100,000 live births in the UK [ 1 ], the impact of maternal suicide is profound and long-lasting. Many more women will attempt suicide during the perinatal period, with a worldwide estimated prevalence of 680 per 100,000 in pregnancy and 210 per 100,000 in the year after birth [ 2 ]. Qualitative research into perinatal suicide attempts is crucial to understand the experiences, motives and the circumstances surrounding these events, but this has largely been unexplored.

Our study aimed to explore the experiences of women and birthing people who had a perinatal suicide attempt and to understand the context and contributing factors surrounding their perinatal suicide attempt.

Through iterative feedback from a group of women with lived experience of perinatal mental illness and relevant stakeholders, a qualitative study design was developed. We recruited women and birthing people ( N = 11) in the UK who self-reported as having undertaken a suicide attempt. Interviews were conducted virtually, recorded and transcribed. Using NVivo software, a critical realist approach to Thematic Analysis was followed, and themes were developed.

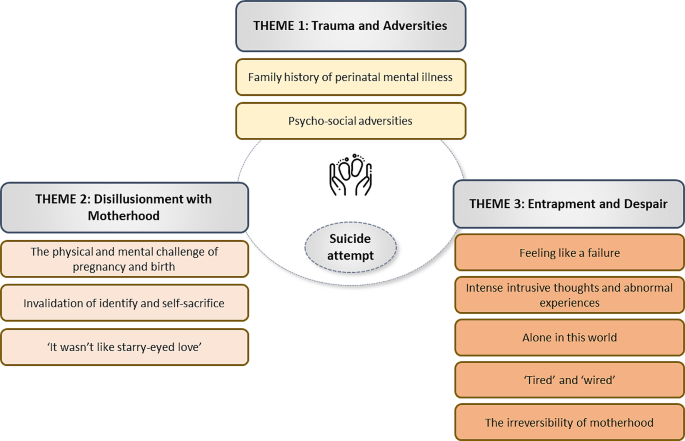

Three key themes were identified that contributed to the perinatal suicide attempt. The first theme ‘Trauma and Adversities’ captures the traumatic events and life adversities with which participants started their pregnancy journeys. The second theme, ‘Disillusionment with Motherhood’ brings together a range of sub-themes highlighting various challenges related to pregnancy, birth and motherhood resulting in a decline in women’s mental health. The third theme, ‘Entrapment and Despair’, presents a range of factors that leads to a significant deterioration of women’s mental health, marked by feelings of failure, hopelessness and losing control.

Conclusions

Feelings of entrapment and despair in women who are struggling with motherhood, alongside a background of traumatic events and life adversities may indicate warning signs of a perinatal suicide. Meaningful enquiry around these factors could lead to timely detection, thus improving care and potentially prevent future maternal suicides.

Peer Review reports

Pregnancy, childbirth, and the postnatal period are a positive and empowering experience for many women and birthing people Footnote 1 . Yet it is widely accepted that the perinatal period is also a time of significant stress, with one in four women experiencing mental health difficulties during this time [ 3 ]. Evidence on the impact of perinatal mental ill-health on the mother [ 4 ], her children [ 5 ], the wider family [ 6 ] and society [ 7 ] has grown in the last decade and worldwide, maternal suicide has been identified as a global public health issue [ 8 ]. In European countries with enhanced surveillance systems for maternal mortality maternal suicide has been identified as one of the leading causes of maternal death [ 9 ]. In the UK, the Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths (MBRRACE-UK) have repeatedly highlighted similar findings, leading to the development and expansion of specialist perinatal mental health services in the UK [ 10 ]. Despite this, there has been no sign of a reduction in suicide rates [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. The UK Government has therefore identified pregnant women and new mothers for the first time as a priority group in the recent Suicide Prevention Strategy [ 15 ].

While maternal suicide is a relatively rare event with a prevalence of 3.84 per 100,000 live births (95% CI 2.55–5.55) in the UK [ 1 ], many more women will attempt suicide during pregnancy and the year after birth. Worldwide, the pooled prevalence of perinatal suicide attempts has been estimated to be 680 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.10–4.69%) during pregnancy and 210 per 100,000 (95% CI 0.01–3.21%) during the first-year postpartum [ 2 ]. As well as distressing in their own right, perinatal suicide attempts are known to increase the risk of future fatal acts [ 16 ]. Antenatal [ 17 ] and postnatal suicide attempts [ 18 ] are also associated with increased maternal and neonatal morbidity, adverse birth outcomes, and further suicide attempts.

It is important to note that terminology in suicide research has been a contentious issue and a wide range of definitions have been used in various contexts. The US National Center for Injury and Control issued guidance on uniform definitions in the context of self-directed violence’ [ 19 ], which has informed our study definition of ‘suicide attempt’: “a non-fatal, self-directed, potentially injurious behaviour with intent to die as a result of the behaviour. A suicide attempt might not result in injury”. This definition contains three components worth highlighting, i.e. (1) suicidal ideation, (2) suicidal intent and (3) suicidal behaviour. ‘Suicidal ideation’, also known as ‘suicidality’ (i.e. thoughts of engaging in suicide-related behaviour) [ 19 ] is a known risk factor for suicide [ 20 ] but does not necessarily lead to suicidal behaviours (e.g., behaviour that is self-directed and deliberately results in injury or the potential for injury to oneself, with implicit or explicit evidence of suicidal intent’) [ 19 ]. ‘Suicide attempt’ must also be distinguished from ‘near-fatal deliberate self-harm’, which was defined by Douglas et al (2004) as ‘an act of self-harm using a method that would usually lead to death, or self-injury to a “vital” body area, or self-poisoning that requires admission to an intensive care unit or is judged to be potentially lethal [ 21 ]’. This definition does not contain an element of ‘suicidal intent’, ie. explicit or implicit evidence that at the time of injury the individual intended to kill self or wished to die, and that the individual understood the probable consequences of his or her actions [ 19 ].

To date, perinatal suicide research has predominately been based on case note reviews [ 1 ], retrospective cohort studies [ 22 ], or qualitative studies focussing on suicidal ideation [ 23 ]. Research into suicide attempts in the perinatal period is therefore acutely needed, to gain a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding maternal suicide, the support available to perinatal women and how future deaths can be avoided. To our knowledge, no studies in the UK have used qualitative methods to explore the experiences of women who undertook a suicide attempt in pregnancy or during the postnatal period, yet survived. A better understanding of these events could help refine support and early interventions for women and birthing people at risk.

Aim of the study

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of women and birthing people who had undertaken one or more suicide attempts during the perinatal period.

Study design

The ASPEN-study (Attempted Suicide during the PEriNatal period) utilised a qualitative design, using semi-structured interviews, to allow for an in-depth understanding of the contextual factors of perinatal suicide attempts, and to demystify the taboos and misunderstanding that are enshrouding this phenomenon [ 24 ]. Qualitative methods are particularly helpful to study sensitive topics [ 25 ] and can facilitate a deeper understanding of suicide attempts, beyond merely explaining [ 26 ]. We adopted a critical realist ontology, meaning participants’ accounts were seen as ‘truths’, even when their reported recall might have been impacted by serious mental illness and/or distress at the time of events [ 27 ]. We also adopted an objectivist epistemological stance meaning our belief system of how we acquire knowledge is one of reality existing and not being constructed, thus enabling an approach to participants’ narratives with no preconceived notions of how the participants may experience the phenomenon of interest [ 28 ]. Drawing on our epistemological and ontological positions, a critical realist approach to Thematic Analysis was best aligned with our philosophical underpinnings. Critical realist TA is an alternative approach to Thematic Analysis, that differs from codebook TA with its positivistic assumptions [ 29 ], or reflexive TA that is grounded in philosophical constructivism [ 30 , 31 ]. Critical realist TA is an explanatory approach that aims to produce causal knowledge through qualitative research on phenomena in the world around us [ 32 , 33 ]. We wanted to go beyond merely ‘exploring’ the phenomenon of perinatal suicide attempt, but aimed to understand what women had experienced during this time, such as any significant life course events they identified as relevant to their perinatal suicide attempt, the specific circumstances in the lead-up to the suicide attempt, their views of motherhood and how this impacted their mental health and any key elements or milestones that made a substantial difference on their journey to recovery. As such, this approach informed our development and structure of the interview schedule and analysis of the data to ensure that this was captured.

Participants and recruitment

The study was advertised through social media and third sector organisations in the field of perinatal mental health and suicide prevention (see Acknowledgements). Interested participants were included if they: (1) were 18 years of age or older; (2) had one or more suicide attempts during the perinatal period (i.e. from pregnancy up to the first year after giving birth), including when the attempt was prevented by self, a loved one or a member of the public; (3) and this happened less than 10 years ago; (4) were residing in the UK; and (5) were not receiving inpatient psychiatric care or experiencing an acute episode of a psychiatric disorder at the time of recruitment. The latter exclusion criterium was adopted in line with our safety protocol, to prevent delays in recovery by addressing such a difficult event outside a therapeutic environment. We used both convenience sampling and purposive sampling techniques: we interviewed anyone who responded to our recruitment materials, met the inclusion criteria and wanted to participate in the study after reading the participant information sheet (convenience sampling). Simultaneously, we also made concerted efforts through intense collaboration with community leaders and third sector organisations to recruit a diverse sample of women and birthing people from different ethnic, cultural, socio-economic and religious backgrounds (purposive sampling). A total of twelve women and birthing people contacted the research team with an interest in the study. Eligibility for the study was explored in a sensitive way, against the overall inclusion criteria and the three components of the study’s definition of ‘suicide attempt’ (suicidal ideation, intent and behaviour). Where in doubt, eligibility was discussed with the wider supervision team. In total, eleven interviews were conducted. A twelfth interested participant did not attend the (online) interview and did not respond to any follow-up emails. Recruitment was finalised when no new themes were being generated from data analysis of the last two interviews [ 34 ]. Participants received reimbursement of £50 for their time to complete the interview and a short demographic survey.

Data collection and analysis

Semi-structured interviews lasted between 38 and 115 min ( MTime = 65 min) and were conducted via video-conference software (Microsoft Teams) by one researcher (KDB) between October 2022 and April 2023. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and de-identified by a professional transcription company. Field notes were taken during the interview. Transcriptions were checked for accuracy by two researchers (KDB, AP). The interview schedule, which was co-designed with a panel of women with lived experience of perinatal mental illness, aimed to explore experiences of mental health difficulties prior to and during the perinatal period, the circumstances in the lead-up to the suicide attempt, and those following the suicide attempt. The interview schedule was used flexibly and did not prevent participants from sharing their story in the order they preferred, but instead, was used as an aid to prompt where required. Interview data was so rich that a secondary analysis focusing on social support prior and after women’s suicide attempts was undertaken, to be published separately.

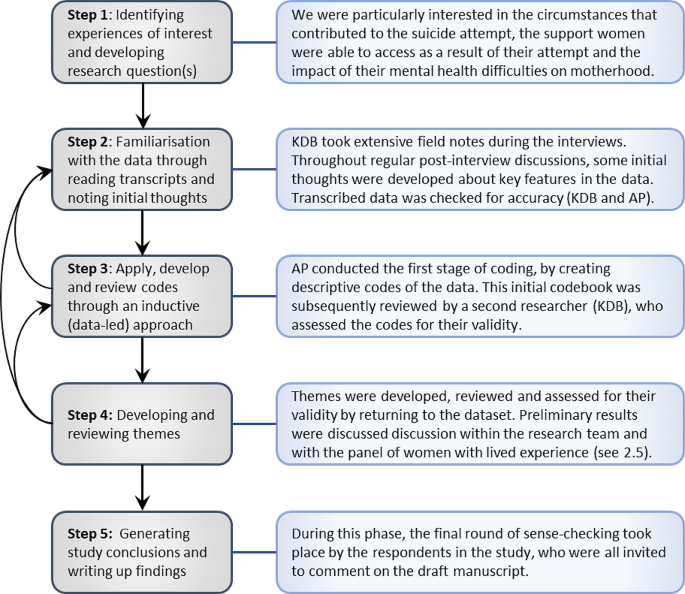

Thematic Analysis (TA) [ 30 , 31 , 33 ] of the interview data was conducted using NVivo software while adopting a critical realist approach to Thematic Analysis [ 30 , 31 , 33 ]. The process of data analysis is rarely a linear event, and guided by Fryer’s previous work on critical realist TA [ 33 ], our approach to data analysis is presented in Fig. 1 and can best be described as follows:

Display of critical realist approach to thematic analysis

Public and patient involvement and engagement (PPIE)

An established advisory panel of women with lived experience of perinatal mental illness was consulted during different phases of the study with additional feedback sought from key stakeholders in the field of perinatal mental illness (see Acknowledgements). The process of PPIE during the study design and data collection phase of this study has been documented elsewhere [ 35 ]. A draft manuscript was shared with research participants to sense-check findings and comment on the manuscript. Participants were also given the opportunity to select a pseudonym of their choice. A total of 8 participants reviewed the draft manuscript and their feedback was incorporated in the final version of this paper.

The study team and reflexivity