Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 14 December 2023

The most important issue about water is not supply, but how it is used

- Peter Gleick 0

Peter Gleick is co-founder and a senior fellow at the Pacific Institute in Oakland, California. He is the author of The Three Ages of Water: Prehistoric Past, Imperiled Present, and a Hope for the Future (2023)

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Floods, droughts, pollution, water scarcity and conflict — humanity’s relationship with water is deteriorating, and it is threatening our health and well-being, as well as that of the environment that sustains us. The good news is that a transition from the water policies and technologies of past centuries to more effective and equitable ways of using and preserving this vital resource is not only possible, but under way. The challenge is to accelerate and broaden the transition.

Water policies have typically fostered a reliance on centralized, often massive infrastructure, such as big dams for flood and drought protection, and aqueducts and pipelines to move water long distances. Governments have also created narrow institutions focused on water, to the detriment of the interconnected issues of food security, climate, energy and ecosystem health. The key assumption of these ‘hard path’ strategies is that society must find more and more supply to meet what was assumed to be never-ending increases in demand.

Nature Outlook: Water

That focus on supply has brought great benefits to many people, but it has also had unintended and increasingly negative consequences. Among these are the failure to provide safe water and sanitation to all; unsustainable overdraft of ground water to produce the food and fibre that the world’s 8 billion people need; inadequate regulation of water pollutants; massive ecological disruption of aquatic ecosystems; political and violent conflict over water resources; and now, accelerating climate disruption to water systems 1 .

A shift away from the supply-oriented hard path is possible — and necessary. Central to this change will be a transition to a focus on demand, efficiency and reuse, and on protecting and restoring ecosystems harmed by centuries of abuse. Society must move away from thinking about how to take more water from already over-tapped rivers, lakes and aquifers, and instead find ways to do the things we want with less water. These include, water technologies to transform industries and allow people to grow more food; appliances to reduce the amount of water used to flush toilets, and wash clothes and dishes; finding and plugging leaks in water-distribution systems and homes; and collecting, treating and reusing waste water.

Remarkably, and unbeknown to most people, the transition to a more efficient and sustainable future is already under way.

Singapore and Israel, two highly water-stressed regions, use much less water per person than do other high-income countries, and they recycle, treat and reuse more than 80% of their waste water 2 . New technologies, including precision irrigation, real-time soil-moisture monitoring and highly localized weather-forecasting models, allow farmers to boost yields and crop quality while cutting water use. Damaging, costly and dangerous dams are being removed, helping to restore rivers and fisheries.

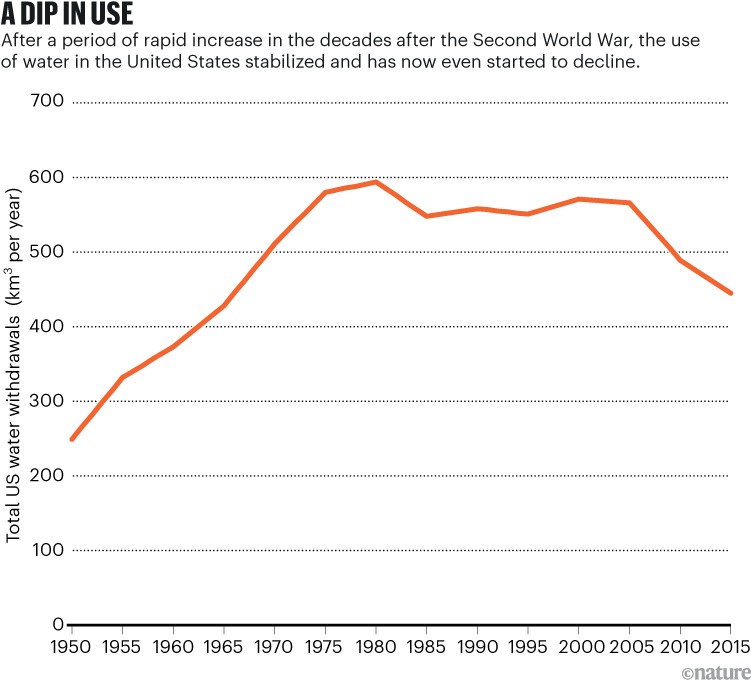

Source: US Geological Survey

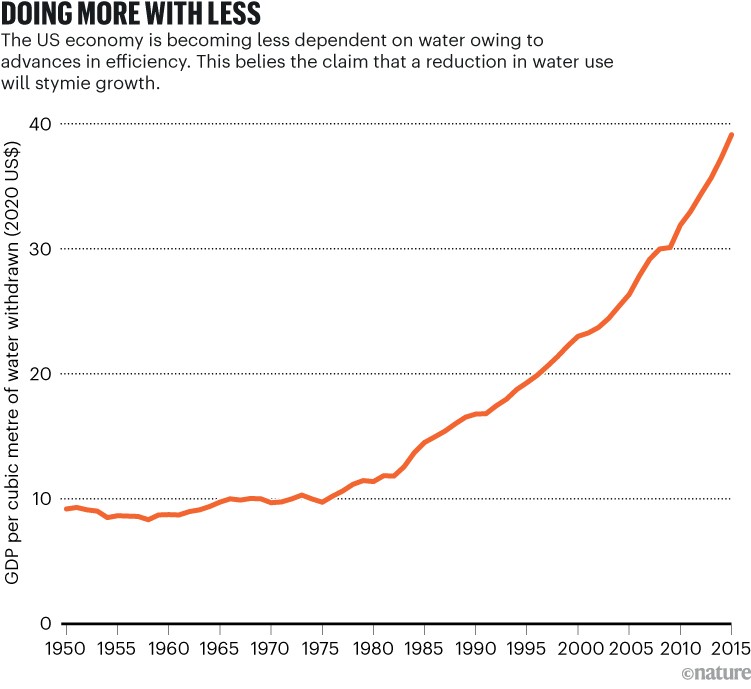

In the United States, total water use is decreasing even though the population and the economy are expanding. Water withdrawals are much less today than they were 50 years ago (see ‘A dip in use’) — evidence that an efficiency revolution is under way. And the United States is indeed doing more with less, because during this time, there has been a marked increase in the economic productivity of water use, measured as units of gross domestic product per unit of water used (see ‘Doing more with less’). Similar trends are evident in many other countries.

Source: US Geological Survey/US Department of Commerce.

Overcoming barriers

The challenge is how to accelerate this transition and overcome barriers to more sustainable and equitable water systems. One important obstacle is the lack of adequate financing and investment in expanding, upgrading and maintaining water systems. Others are institutional resistance in the form of weak or misdirected regulations, antiquated water-rights laws, and inadequate training of water managers with outdated ideas and tools. Another is blind adherence by authorities to old-fashioned ideas or simple ignorance about both the risks of the hard path and the potential of alternatives.

Funding for the modernization of water systems must be increased. In the United States, President Biden’s Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act provides US$82.5 billion for water-related programmes, including removing toxic lead pipes and providing water services to long-neglected front-line communities. These communities include those dependent on unregulated rural water systems, farm-worker communities in California’s Central Valley, Indigenous populations and those in low-income urban centres with deteriorating infrastructure. That’s a good start. But more public- and private-investments are needed, especially to provide modern water and sanitation systems globally for those who still lack them, and to improve efficiency and reuse.

Regulations have been helpful in setting standards to cut waste and improve water quality, but further standards — and stronger enforcement — are needed to protect against new pollutants. Providing information on how to cut food waste on farms and in food processing, and how to shift diets to less water-intensive food choices can help producers and consumers to reduce their water footprints 3 . Corporations must expand water stewardship efforts in their operations and supply chains. Water institutions must be reformed and integrated with those that deal with energy and climate challenges. And we must return water to the environment to restore ecological systems that, in turn, protect human health and well-being.

In short, the status quo is not acceptable. Efforts must be made at all levels to accelerate the shift from simply supplying more water to meeting human and ecological water needs as carefully and efficiently as possible. No new technologies need to be invented for this to happen, and the economic costs of the transition are much less than the costs of failing to do so. Individuals, communities, corporations and governments all have a part to play. A sustainable water future is possible if we choose the right path.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-023-03899-2

This article is part of Nature Outlook: Water , a supplement produced with financial support from the FII Institute. Nature maintains full independence in all editorial decisions related to the content. About this content .

Caretta, M. A. et al . In: Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (eds Portner, H.-O. et al .) 551–712 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2022)

Google Scholar

Giakoumis, T., Vaghela, C. & Voulvoulis, N. Adv. Chem. Pollut. Environ. Manag. Protect. 5 , 227–252 (2020).

Article Google Scholar

Heller, M. C., Willits-Smith, A., Mahon, T., Keoleian, G. A. & Rose, D. Nature Food 2 , 255–263 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Download references

Related Articles

- Water resources

- Sustainability

- Environmental sciences

How to achieve safe water access for all: work with local communities

Comment 22 MAR 24

The Solar System has a new ocean — it’s buried in a small Saturn moon

News 07 FEB 24

Groundwater decline is global but not universal

News & Views 24 JAN 24

Real-world plastic-waste success stories can help to boost global treaty

Correspondence 14 MAY 24

Inequality is bad — but that doesn’t mean the rich are

Diana Wall obituary: ecologist who foresaw the importance of soil biodiversity

Obituary 10 MAY 24

Forestry social science is failing the needs of the people who need it most

Editorial 15 MAY 24

One-third of Southern Ocean productivity is supported by dust deposition

Article 15 MAY 24

Research Associate - Metabolism

Houston, Texas (US)

Baylor College of Medicine (BCM)

Postdoc Fellowships

Train with world-renowned cancer researchers at NIH? Consider joining the Center for Cancer Research (CCR) at the National Cancer Institute

Bethesda, Maryland

NIH National Cancer Institute (NCI)

Faculty Recruitment, Westlake University School of Medicine

Faculty positions are open at four distinct ranks: Assistant Professor, Associate Professor, Full Professor, and Chair Professor.

Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Westlake University

PhD/master's Candidate

PhD/master's Candidate Graduate School of Frontier Science Initiative, Kanazawa University is seeking candidates for PhD and master's students i...

Kanazawa University

Senior Research Assistant in Human Immunology (wet lab)

Senior Research Scientist in Human Immunology, high-dimensional (40+) cytometry, ICS and automated robotic platforms.

Boston, Massachusetts (US)

Boston University Atomic Lab

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplement Archive

- Article Collection Archive

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- Call for Papers

- Why Publish?

- About Nutrition Reviews

- About International Life Sciences Institute

- Editorial Board

- Early Career Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, physiological effects of dehydration, hydration and chronic diseases, water consumption and requirements and relationships to total energy intake, water requirements: evaluation of the adequacy of water intake, acknowledgments, water, hydration, and health.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Barry M Popkin, Kristen E D'Anci, Irwin H Rosenberg, Water, hydration, and health, Nutrition Reviews , Volume 68, Issue 8, 1 August 2010, Pages 439–458, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00304.x

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This review examines the current knowledge of water intake as it pertains to human health, including overall patterns of intake and some factors linked with intake, the complex mechanisms behind water homeostasis, and the effects of variation in water intake on health and energy intake, weight, and human performance and functioning. Water represents a critical nutrient, the absence of which will be lethal within days. Water's importance for the prevention of nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases has received more attention recently because of the shift toward consumption of large proportions of fluids as caloric beverages. Despite this focus, there are major gaps in knowledge related to the measurement of total fluid intake and hydration status at the population level; there are also few longer-term systematic interventions and no published randomized, controlled longer-term trials. This review provides suggestions for ways to examine water requirements and encourages more dialogue on this important topic.

Water is essential for life. From the time that primeval species ventured from the oceans to live on land, a major key to survival has been the prevention of dehydration. The critical adaptations cross an array of species, including man. Without water, humans can survive only for days. Water comprises from 75% body weight in infants to 55% in the elderly and is essential for cellular homeostasis and life. 1 Nevertheless, there are many unanswered questions about this most essential component of our body and our diet. This review attempts to provide some sense of our current knowledge of water, including overall patterns of intake and some factors linked with intake, the complex mechanisms behind water homeostasis, the effects of variation in water intake on health and energy intake, weight, and human performance and functioning.

Recent statements on water requirements have been based on retrospective recall of water intake from food and beverages among healthy, noninstitutionalized individuals. Provided here are examples of water intake assessment in populations to clarify the need for experimental studies. Beyond these circumstances of dehydration, it is not fully understood how hydration affects health and well-being, even the impact of water intakes on chronic diseases. Recently, Jéquier and Constant 2 addressed this question based on human physiology, but more knowledge is required about the extent to which water intake might be important for disease prevention and health promotion.

As noted later in the text, few countries have developed water requirements and those that exist are based on weak population-level measures of water intake and urine osmolality. 3 , 4 The European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) was recently asked to revise existing recommended intakes of essential substances with a physiological effect, including water since this nutrient is essential for life and health. 5

The US Dietary Recommendations for water are based on median water intakes with no use of measurements of the dehydration status of the population to assist. One-time collection of blood samples for the analysis of serum osmolality has been used by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey program. At the population level, there is no accepted method of assessing hydration status, and one measure some scholars use, hypertonicity, is not even linked with hydration in the same direction for all age groups. 6 Urine indices are used often but these reflect the recent volume of fluid consumed rather than a state of hydration. 7 Many scholars use urine osmolality to measure recent hydration status. 8 , – 12 Deuterium dilution techniques (isotopic dilution with D 2 O, or deuterium oxide) allow measurement of total body water but not water balance status. 13 Currently, there are no completely adequate biomarkers to measure hydration status at the population level.

In discussing water, the focus is first and foremost on all types of water, whether it be soft or hard, spring or well, carbonated or distilled. Furthermore, water is not only consumed directly as a beverage; it is also obtained from food and to a very small extent from oxidation of macronutrients (metabolic water). The proportion of water that comes from beverages and food varies according to the proportion of fruits and vegetables in the diet. The ranges of water content in various foods are presented in Table 1 . In the United States it is estimated that about 22% of water intake comes from food while the percentages are much higher in European countries, particularly a country like Greece with its higher intake of fruits and vegetables, or in South Korea. 3 , – 15 The only in-depth study performed in the United States of water use and water intrinsic to food found a 20.7% contribution from food water; 16 , 17 however, as shown below, this research was dependent on poor overall assessment of water intake.

Ranges of water content for selected foods.

Data from the USDA national nutrient database for standard reference, release 21, as provided in Altman. 126

This review considers water requirements in the context of recent efforts to assess water intake in US populations. The relationship between water and calorie intake is explored both for insights into the possible displacement of calories from sweetened beverages by water and to examine the possibility that water requirements would be better expressed in relation to calorie/energy requirements with the dependence of the latter on age, size, gender, and physical activity level. Current understanding of the exquisitely complex and sensitive system that protects land animals against dehydration is covered and commentary is provided on the complications of acute and chronic dehydration in man, against which a better expression of water requirements might complement the physiological control of thirst. Indeed, the fine intrinsic regulation of hydration and water intake in individuals mitigates prevalent underhydration in populations and its effects on function and disease.

Regulation of fluid intake

To prevent dehydration, reptiles, birds, vertebrates, and all land animals have evolved an exquisitely sensitive network of physiological controls to maintain body water and fluid intake by thirst. Humans may drink for various reasons, particularly for hedonic ones, but drinking is most often due to water deficiency that triggers the so-called regulatory or physiological thirst. The mechanism of thirst is quite well understood today and the reason nonregulatory drinking is often encountered is related to the large capacity of the kidneys to rapidly eliminate excesses of water or to reduce urine secretion to temporarily economize on water. 1 But this excretory process can only postpone the necessity of drinking or of ceasing to drink an excess of water. Nonregulatory drinking is often confusing, particularly in wealthy societies that have highly palatable drinks or fluids that contain other substances the drinker seeks. The most common of these are sweeteners or alcohol for which water is used as a vehicle. Drinking these beverages is not due to excessive thirst or hyperdipsia, as can be shown by offering pure water to individuals instead and finding out that the same drinker is in fact hypodipsic (characterized by abnormally diminished thirst). 1

Fluid balance of the two compartments

Maintaining a constant water and mineral balance requires the coordination of sensitive detectors at different sites in the body linked by neural pathways with integrative centers in the brain that process this information. These centers are also sensitive to humoral factors (neurohormones) produced for the adjustment of diuresis, natriuresis, and blood pressure (angiotensin mineralocorticoids, vasopressin, atrial natriuretic factor). Instructions from the integrative centers to the “executive organs” (kidney, sweat glands, and salivary glands) and to the part of the brain responsible for corrective actions such as drinking are conveyed by certain nerves in addition to the above-mentioned substances. 1

Most of the components of fluid balance are controlled by homeostatic mechanisms responding to the state of body water. These mechanisms are sensitive and precise, and are activated with deficits or excesses of water amounting to only a few hundred milliliters. A water deficit produces an increase in the ionic concentration of the extracellular compartment, which takes water from the intracellular compartment causing cells to shrink. This shrinkage is detected by two types of brain sensors, one controlling drinking and the other controlling the excretion of urine by sending a message to the kidneys, mainly via the antidiuretic hormone vasopressin to produce a smaller volume of more concentrated urine. 18 When the body contains an excess of water, the reverse processes occur: the lower ionic concentration of body fluids allows more water to reach the intracellular compartment. The cells imbibe, drinking is inhibited, and the kidneys excrete more water.

The kidneys thus play a key role in regulating fluid balance. As discussed later, the kidneys function more efficiently in the presence of an abundant water supply. If the kidneys economize on water and produce more concentrated urine, they expend a greater amount of energy and incur more wear on their tissues. This is especially likely to occur when the kidneys are under stress, e.g., when the diet contains excessive amounts of salt or toxic substances that need to be eliminated. Consequently, drinking a sufficient amount of water helps protect this vital organ.

Regulatory drinking

Most drinking occurs in response to signals of water deficit. Apart from urinary excretion, the other main fluid regulatory process is drinking, which is mediated through the sensation of thirst. There are two distinct mechanisms of physiological thirst: the intracellular and the extracellular mechanisms. When water alone is lost, ionic concentration increases. As a result, the intracellular space yields some of its water to the extracellular compartment. Once again, the resulting shrinkage of cells is detected by brain receptors that send hormonal messages to induce drinking. This association with receptors that govern extracellular volume is accompanied by an enhancement of appetite for salt. Thus, people who have been sweating copiously prefer drinks that are relatively rich in Na+ salts rather than pure water. When excessive sweating is experienced, it is also important to supplement drinks with additional salt.

The brain's decision to start or stop drinking and to choose the appropriate drink is made before the ingested fluid can reach the intra- and extracellular compartments. The taste buds in the mouth send messages to the brain about the nature, and especially the salt content, of the ingested fluid, and neuronal responses are triggered as if the incoming water had already reached the bloodstream. These are the so-called anticipatory reflexes: they cannot be entirely “cephalic reflexes” because they arise from the gut as well as the mouth. 1

The anterior hypothalamus and pre-optic area are equipped with osmoreceptors related to drinking. Neurons in these regions show enhanced firing when the inner milieu gets hyperosmotic. Their firing decreases when water is loaded in the carotid artery that irrigates the neurons. It is remarkable that the same decrease in firing in the same neurons takes place when the water load is applied on the tongue instead of being injected into the carotid artery. This anticipatory drop in firing is due to communication from neural pathways that depart from the mouth and converge onto neurons that simultaneously sense the blood's inner milieu.

Nonregulatory drinking

Although everyone experiences thirst from time to time, it plays little role in the day-to-day control of water intake in healthy people living in temperate climates. In these regions, people generally consume fluids not to quench thirst, but as components of everyday foods (e.g., soup, milk), as beverages used as mild stimulants (tea, coffee), and for pure pleasure. A common example is alcohol consumption, which can increase individual pleasure and stimulate social interaction. Drinks are also consumed for their energy content, as in soft drinks and milk, and are used in warm weather for cooling and in cold weather for warming. Such drinking seems to also be mediated through the taste buds, which communicate with the brain in a kind of “reward system”, the mechanisms of which are just beginning to be understood. This bias in the way human beings rehydrate themselves may be advantageous because it allows water losses to be replaced before thirst-producing dehydration takes place. Unfortunately, this bias also carries some disadvantages. Drinking fluids other than water can contribute to an intake of caloric nutrients in excess of requirements, or in alcohol consumption that, in some people, may insidiously bring about dependence. For example, total fluid intake increased from 79 fluid ounces in 1989 to 100 fluid ounces in 2002 among US adults, with the difference representing intake of caloric beverages. 19

Effects of aging on fluid intake regulation

The thirst and fluid ingestion responses of older persons to a number of stimuli have been compared to those of younger persons. 20 Following water deprivation, older individuals are less thirsty and drink less fluid compared to younger persons. 21 , 22 The decrease in fluid consumption is predominantly due to a decrease in thirst, as the relationship between thirst and fluid intake is the same in young and old persons. Older persons drink insufficient amounts of water following fluid deprivation to replenish their body water deficit. 23 When dehydrated older persons are offered a highly palatable selection of drinks, this also fails to result in increased fluid intake. 23 The effects of increased thirst in response to an osmotic load have yielded variable responses, with one group reporting reduced osmotic thirst in older individuals 24 and one failing to find a difference. In a third study, young individuals ingested almost twice as much fluid as old persons, even though the older subjects had a much higher serum osmolality. 25

Overall, these studies support small changes in the regulation of thirst and fluid intake with aging. Defects in both osmoreceptors and baroreceptors appear to exist as do changes in the central regulatory mechanisms mediated by opioid receptors. 26 Because the elderly have low water reserves, it may be prudent for them to learn to drink regularly when not thirsty and to moderately increase their salt intake when they sweat. Better education on these principles may help prevent sudden hypotension and stroke or abnormal fatigue, which can lead to a vicious circle and eventually hospitalization.

Thermoregulation

Hydration status is critical to the body's process of temperature control. Body water loss through sweat is an important cooling mechanism in hot climates and in periods of physical activity. Sweat production is dependent upon environmental temperature and humidity, activity levels, and type of clothing worn. Water losses via skin (both insensible perspiration and sweating) can range from 0.3 L/h in sedentary conditions to 2.0 L/h in high activity in the heat, and intake requirements range from 2.5 to just over 3 L/day in adults under normal conditions, and can reach 6 L/day with high extremes of heat and activity. 27 , 28 Evaporation of sweat from the body results in cooling of the skin. However, if sweat loss is not compensated for with fluid intake, especially during vigorous physical activity, a hypohydrated state can occur with concomitant increases in core body temperature. Hypohydration from sweating results in a loss of electrolytes, as well as a reduction in plasma volume, and this can lead to increased plasma osmolality. During this state of reduced plasma volume and increased plasma osmolality, sweat output becomes insufficient to offset increases in core temperature. When fluids are given to maintain euhydration, sweating remains an effective compensation for increased core temperatures. With repeated exposure to hot environments, the body adapts to heat stress and cardiac output and stroke volume return to normal, sodium loss is conserved, and the risk for heat-stress-related illness is reduced. 29 Increasing water intake during this process of heat acclimatization will not shorten the time needed to adapt to the heat, but mild dehydration during this time may be of concern and is associated with elevations in cortisol, increased sweating, and electrolyte imbalances. 29

Children and the elderly have differing responses to ambient temperature and different thermoregulatory concerns than healthy adults. Children in warm climates may be more susceptible to heat illness than adults due to their greater surface area to body mass ratio, lower rate of sweating, and slower rate of acclimatization to heat. 30 , 31 Children may respond to hypohydration during activity with a higher relative increase in core temperature than adults, 32 and with a lower propensity to sweat, thus losing some of the benefits of evaporative cooling. However, it has been argued that children can dissipate a greater proportion of body heat via dry heat loss, and the concomitant lack of sweating provides a beneficial means of conserving water under heat stress. 30 Elders, in response to cold stress, show impairments in thermoregulatory vasoconstriction, and body water is shunted from plasma into the interstitial and intracellular compartments. 33 , 34 With respect to heat stress, water lost through sweating decreases the water content of plasma, and the elderly are less able to compensate for increased blood viscosity. 33 Not only do they have a physiological hypodipsia, but this can be exaggerated by central nervous system disease 35 and by dementia. 36 In addition, illness and limitations in daily living activities can further limit fluid intake. When reduced fluid intake is coupled with advancing age, there is a decrease in total body water. Older individuals have impaired renal fluid conservation mechanisms and, as noted above, have impaired responses to heat and cold stress. 33 , 34 All of these factors contribute to an increased risk of hypohydration and dehydration in the elderly.

With regard to physiology, the role of water in health is generally characterized in terms of deviations from an ideal hydrated state, generally in comparison to dehydration. The concept of dehydration encompasses both the process of losing body water and the state of dehydration. Much of the research on water and physical or mental functioning compares a euhydrated state, usually achieved by provision of water sufficient to overcome water loss, to a dehydrated state, which is achieved via withholding of fluids over time and during periods of heat stress or high activity. In general, provision of water is beneficial in individuals with a water deficit, but little research supports the notion that additional water in adequately hydrated individuals confers any benefit.

Physical performance

The role of water and hydration in physical activity, particularly in athletes and in the military, has been of considerable interest and is well-described in the scientific literature. 37 , – 39 During challenging athletic events, it is not uncommon for athletes to lose 6–10% of body weight through sweat, thus leading to dehydration if fluids have not been replenished. However, decrements in the physical performance of athletes have been observed under much lower levels of dehydration, i.e., as little as 2%. 38 Under relatively mild levels of dehydration, individuals engaging in rigorous physical activity will experience decrements in performance related to reduced endurance, increased fatigue, altered thermoregulatory capability, reduced motivation, and increased perceived effort. 40 , 41 Rehydration can reverse these deficits and reduce the oxidative stress induced by exercise and dehydration. 42 Hypohydration appears to have a more significant impact on high-intensity and endurance activity, such as tennis 43 and long-distance running, 44 than on anaerobic activities, 45 such as weight lifting, or on shorter-duration activities, such as rowing. 46

During exercise, individuals may not hydrate adequately when allowed to drink according to thirst. 32 After periods of physical exertion, voluntary fluid intake may be inadequate to offset fluid deficits. 1 Thus, mild-to-moderate dehydration can persist for some hours after the conclusion of physical activity. Research performed on athletes suggests that, principally at the beginning of the training season, they are at particular risk for dehydration due to lack of acclimatization to weather conditions or suddenly increased activity levels. 47 , 48 A number of studies show that performance in temperate and hot climates is affected to a greater degree than performance in cold temperatures. 41 , – 50 Exercise in hot conditions with inadequate fluid replacement is associated with hyperthermia, reduced stroke volume and cardiac output, decreases in blood pressure, and reduced blood flow to muscle. 51

During exercise, children may be at greater risk for voluntary dehydration. Children may not recognize the need to replace lost fluids, and both children as well as coaches need specific guidelines for fluid intake. 52 Additionally, children may require more time to acclimate to increases in environmental temperature than adults. 30 , 31 Recommendations are for child athletes or children in hot climates to begin athletic activities in a well-hydrated state and to drink fluids over and above the thirst threshold.

Cognitive performance

Water, or its lack (dehydration), can influence cognition. Mild levels of dehydration can produce disruptions in mood and cognitive functioning. This may be of special concern in the very young, very old, those in hot climates, and those engaging in vigorous exercise. Mild dehydration produces alterations in a number of important aspects of cognitive function such as concentration, alertness, and short-term memory in children (10–12 y), 32 young adults (18–25 y), 53 , – 56 and the oldest adults (50–82 y). 57 As with physical functioning, mild-to-moderate levels of dehydration can impair performance on tasks such as short-term memory, perceptual discrimination, arithmetic ability, visuomotor tracking, and psychomotor skills. 53 , – 56 However, mild dehydration does not appear to alter cognitive functioning in a consistent manner. 53 , – 58 In some cases, cognitive performance was not significantly affected in ranges from 2% to 2.6% dehydration. 56 , 58 Comparing across studies, performance on similar cognitive tests was divergent under dehydration conditions. 54 , 56 In studies conducted by Cian et al., 53 , 54 participants were dehydrated to approximately 2.8% either through heat exposure or treadmill exercise. In both studies, performance was impaired on tasks examining visual perception, short-term memory, and psychomotor ability. In a series of studies using exercise in conjunction with water restriction as a means of producing dehydration, D'Anci et al. 56 observed only mild decrements in cognitive performance in healthy young men and women athletes. In these experiments, the only consistent effect of mild dehydration was significant elevations of subjective mood score, including fatigue, confusion, anger, and vigor. Finally, in a study using water deprivation alone over a 24-h period, no significant decreases in cognitive performance were seen with 2.6% dehydration. 58 It is therefore possible that heat stress may play a critical role in the effects of dehydration on cognitive performance.

Reintroduction of fluids under conditions of mild dehydration can reasonably be expected to reverse dehydration-induced cognitive deficits. Few studies have examined how fluid reintroduction may alleviate the negative effects of dehydration on cognitive performance and mood. One study 59 examined how water ingestion affected arousal and cognitive performance in young people following a period of 12-h water restriction. While cognitive performance was not affected by either water restriction or water consumption, water ingestion affected self-reported arousal. Participants reported increased alertness as a function of water intake. Rogers et al. 60 observed a similar increase in alertness following water ingestion in both high- and low-thirst participants. Water ingestion, however, had opposite effects on cognitive performance as a function of thirst. High-thirst participants' performance on a cognitively demanding task improved following water ingestion, but low-thirst participants' performance declined. In summary, hydration status consistently affected self-reported alertness, but effects on cognition were less consistent.

Several recent studies have examined the utility of providing water to school children on attentiveness and cognitive functioning in children. 61 , – 63 In these experiments, children were not fluid restricted prior to cognitive testing, but were allowed to drink as usual. Children were then provided with a drink or no drink 20–45 min before the cognitive test sessions. In the absence of fluid restriction and without physiological measures of hydration status, the children in these studies should not be classified as dehydrated. Subjective measures of thirst were reduced in children given water, 62 and voluntary water intake in children varied from 57 mL to 250 mL. In these studies, as in the studies in adults, the findings were divergent and relatively modest. In the research led by Edmonds et al., 61 , 62 children in the groups given water showed improvements in visual attention. However, effects on visual memory were less consistent, with one study showing no effects of drinking water on a spot-the-difference task in 6–7-year-old children 61 and the other showing a significant improvement in a similar task in 7–9-year-old children. 62 In the research described by Benton and Burgess, 63 memory performance was improved by provision of water but sustained attention was not altered with provision of water in the same children.

Taken together, these studies indicate that low-to-moderate dehydration may alter cognitive performance. Rather than indicating that the effects of hydration or water ingestion on cognition are contradictory, many of the studies differ significantly in methodology and in measurement of cognitive behaviors. These variances in methodology underscore the importance of consistency when examining relatively subtle chances in overall cognitive performance. However, in those studies in which dehydration was induced, most combined heat and exercise; this makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of dehydration on cognitive performance in temperate conditions from the effects of heat and exercise. Additionally, relatively little is known about the mechanism of mild dehydration's effects on mental performance. It has been proposed that mild dehydration acts as a physiological stressor that competes with and draws attention from cognitive processes. 64 However, research on this hypothesis is limited and merits further exploration.

Dehydration and delirium

Dehydration is a risk factor for delirium and for delirium presenting as dementia in the elderly and in the very ill. 65 , – 67 Recent work shows that dehydration is one of several predisposing factors for confusion observed in long-term-care residents 67 ; however, in this study, daily water intake was used as a proxy measure for dehydration rather than other, more direct clinical assessments such as urine or plasma osmolality. Older people have been reported as having reduced thirst and hypodipsia relative to younger people. In addition, fluid intake and maintenance of water balance can be complicated by factors such as disease, dementia, incontinence, renal insufficiency, restricted mobility, and drug side effects. In response to primary dehydration, older people have less thirst sensation and reduced fluid intakes in comparison to younger people. However, in response to heat stress, while older people still display a reduced thirst threshold, they do ingest comparable amounts of fluid to younger people. 20

Gastrointestinal function

Fluids in the diet are generally absorbed in the proximal small intestine, and the absorption rate is determined by the rate of gastric emptying to the small intestine. Therefore, the total volume of fluid consumed will eventually be reflected in water balance, but the rate at which rehydration occurs is dependent upon factors affecting the rate of delivery of fluids to the intestinal mucosa. The gastric emptying rate is generally accelerated by the total volume consumed and slowed by higher energy density and osmolality. 68 In addition to water consumed in food (1 L/day) and beverages (circa 2–3 L/day), digestive secretions account for a far greater portion of water that passes through and is absorbed by the gastrointestinal tract (circa 8 L/day). 69 The majority of this water is absorbed by the small intestine, with a capacity of up to 15 L/day with the colon absorbing some 5 L/day. 69

Constipation, characterized by slow gastrointestinal transit, small, hard stools, and difficulty in passing stool, has a number of causes, including medication use, inadequate fiber intake, poor diet, and illness. 70 Inadequate fluid consumption is touted as a common culprit in constipation, and increasing fluid intake is a frequently recommended treatment. Evidence suggests, however, that increasing fluids is only useful to individuals in a hypohydrated state, and is of little utility in euhydrated individuals. 70 In young children with chronic constipation, increasing daily water intake by 50% did not affect constipation scores. 71 For Japanese women with low fiber intake, concomitant low water intake in the diet is associated with increased prevalence of constipation. 72 In older individuals, low fluid intake is a predictor for increased levels of acute constipation, 73 , 74 with those consuming the least amount of fluid having over twice the frequency of constipation episodes than those consuming the most fluid. In one trial, researchers compared the utility of carbonated mineral water in reducing functional dyspepsia and constipation scores to tap water in individuals with functional dyspepsia. 75 When comparing carbonated mineral water to tap water, participants reported improvements in subjective gastric symptoms, but there were no significant improvements in gastric or intestinal function. The authors indicate it is not possible to determine to what degree the mineral content of the two waters contributed to perceived symptom relief, as the mineral water contained greater levels of magnesium and calcium than the tap water. The available evidence suggests that increased fluid intake should only be indicated in individuals in a hypohydrated state. 69 , 71

Significant water loss can occur through the gastrointestinal tract, and this can be of great concern in the very young. In developing countries, diarrheal diseases are a leading cause of death in children, resulting in approximately 1.5–2.5 million deaths per year. 76 Diarrheal illness results not only in a reduction in body water, but also in potentially lethal electrolyte imbalances. Mortality in such cases can many times be prevented with appropriate oral rehydration therapy, by which simple dilute solutions of salt and sugar in water can replace fluid lost by diarrhea. Many consider application of oral rehydration therapy to be one of the significant public health developments of the last century. 77

Kidney function

As noted above, the kidney is crucial in regulating water balance and blood pressure as well as removing waste from the body. Water metabolism by the kidney can be classified into regulated and obligate. Water regulation is hormonally mediated, with the goal of maintaining a tight range of plasma osmolality (between 275 and 290 mOsm/kg). Increases in plasma osmolality and activation of osmoreceptors (intracellular) and baroreceptors (extracellular) stimulate hypothalamic release of arginine vasopressin (AVP). AVP acts at the kidney to decrease urine volume and promote retention of water, and the urine becomes hypertonic. With decreased plasma osmolality, vasopressin release is inhibited, and the kidney increases hypotonic urinary output.

In addition to regulating fluid balance, the kidneys require water for the filtration of waste from the bloodstream and excretion via urine. Water excretion via the kidney removes solutes from the blood, and a minimum obligate urine volume is required to remove the solute load with a maximum output volume of 1 L/h. 78 This obligate volume is not fixed, but is dependent upon the amount of metabolic solutes to be excreted and levels of AVP. Depending on the need for water conservation, basal urine osmolality ranges from 40 mOsm/kg to a maximum of 1,400 mOsm/kg. 78 The ability to both concentrate and dilute urine decreases with age, with a lower value of 92 mOsm/kg and an upper range falling between 500 and 700 mOsm/kg for individuals over the age of 70 years. 79 , – 81 Under typical conditions, in an average adult, urine volume of 1.5 to 2.0 L/day would be sufficient to clear a solute load of 900 to 1,200 mOsm/day. During water conservation and the presence of AVP, this obligate volume can decrease to 0.75–1.0 L/day and during maximal diuresis up to 20 L/day can be required to remove the same solute load. 78 , – 81 In cases of water loading, if the volume of water ingested cannot be compensated for with urine output, having overloaded the kidney's maximal output rate, an individual can enter a hyponatremic state.

Heart function and hemodynamic response

Blood volume, blood pressure, and heart rate are closely linked. Blood volume is normally tightly regulated by matching water intake and water output, as described in the section on kidney function. In healthy individuals, slight changes in heart rate and vasoconstriction act to balance the effect of normal fluctuations in blood volume on blood pressure. 82 Decreases in blood volume can occur, through blood loss (or blood donation), or loss of body water through sweat, as seen with exercise. Blood volume is distributed differently relative to the position of the heart, whether supine or upright, and moving from one position to the other can lead to increased heart rate, a fall in blood pressure, and, in some cases, syncope. This postural hypotension (or orthostatic hypotension) can be mediated by drinking 300–500 mL of water. 83 , 84 Water intake acutely reduces heart rate and increases blood pressure in both normotensive and hypertensive individuals. 85 These effects of water intake on the pressor effect and heart rate occur within 15–20 min of drinking water and can last for up to 60 min. Water ingestion is also beneficial in preventing vasovagal reaction with syncope in blood donors at high risk for post-donation syncope. 86 The effect of water intake in these situations is thought to be due to effects on the sympathetic nervous system rather than to changes in blood volume. 83 , 84 Interestingly, in rare cases, individuals may experience bradycardia and syncope after swallowing cold liquids. 87 , – 89 While swallow syncope can be seen with substances other than water, swallow syncope further supports the notion that the result of water ingestion in the pressor effect has both a neural component as well as a cardiac component.

Water deprivation and dehydration can lead to the development of headache. 90 Although this observation is largely unexplored in the medical literature, some observational studies indicate that water deprivation, in addition to impairing concentration and increasing irritability, can serve as a trigger for migraine and can also prolong migraine. 91 , 92 In those with water deprivation-induced headache, ingestion of water provided relief from headache in most individuals within 30 min to 3 h. 92 It is proposed that water deprivation-induced headache is the result of intracranial dehydration and total plasma volume. Although provision of water may be useful in relieving dehydration-related headache, the utility of increasing water intake for the prevention of headache is less well documented.

The folk wisdom that drinking water can stave off headaches has been relatively unchallenged, and has more traction in the popular press than in the medical literature. Recently, one study examined increased water intake and headache symptoms in headache patients. 93 In this randomized trial, patients with a history of different types of headache, including migraine and tension headache, were either assigned to a placebo condition (a nondrug tablet) or the increased water condition. In the water condition, participants were instructed to consume an additional volume of 1.5 L water/day on top of what they already consumed in foods and fluids. Water intake did not affect the number of headache episodes, but it was modestly associated with reduction in headache intensity and reduced duration of headache. The data from this study suggest that the utility of water as prophylaxis is limited in headache sufferers, and the ability of water to reduce or prevent headache in the broader population remains unknown.

One of the more pervasive myths regarding water intake is its relation to improvements of the skin or complexion. By improvement, it is generally understood that individuals are seeking to have a more “moisturized” look to the surface skin, or to minimize acne or other skin conditions. Numerous lay sources such as beauty and health magazines as well as postings on the Internet suggest that drinking 8–10 glasses of water a day will “flush toxins from the skin” and “give a glowing complexion” despite a general lack of evidence 94 , 95 to support these proposals. The skin, however, is important for maintaining body water levels and preventing water loss into the environment.

The skin contains approximately 30% water, which contributes to plumpness, elasticity, and resiliency. The overlapping cellular structure of the stratum corneum and lipid content of the skin serves as “waterproofing” for the body. 96 Loss of water through sweat is not indiscriminate across the total surface of the skin, but is carried out by eccrine sweat glands, which are evenly distributed over most of the body surface. 97 Skin dryness is usually associated with exposure to dry air, prolonged contact with hot water and scrubbing with soap (both strip oils from the skin), medical conditions, and medications. While more serious levels of dehydration can be reflected in reduced skin turgor, 98 , 99 with tenting of the skin acting as a flag for dehydration, overt skin turgor in individuals with adequate hydration is not altered. Water intake, particularly in individuals with low initial water intake, can improve skin thickness and density as measured by sonogram, 100 offsets transepidermal water loss, and can improve skin hydration. 101 Adequate skin hydration, however, is not sufficient to prevent wrinkles or other signs of aging, which are related to genetics and to sun and environmental damage. Of more utility to individuals already consuming adequate fluids is the use of topical emollients; these will improve skin barrier function and improve the look and feel of dry skin. 102 , 103

Many chronic diseases have multifactorial origins. In particular, differences in lifestyle and the impact of environment are known to be involved and constitute risk factors that are still being evaluated. Water is quantitatively the most important nutrient. In the past, scientific interest with regard to water metabolism was mainly directed toward the extremes of severe dehydration and water intoxication. There is evidence, however, that mild dehydration may also account for some morbidities. 4 , 104 There is currently no consensus on a “gold standard” for hydration markers, particularly for mild dehydration. As a consequence, the effects of mild dehydration on the development of several disorders and diseases have not been well documented.

There is strong evidence showing that good hydration reduces the risk of urolithiasis (see Table 2 for evidence categories). Less strong evidence links good hydration with reduced incidence of constipation, exercise asthma, hypertonic dehydration in the infant, and hyperglycemia in diabetic ketoacidosis. Good hydration is associated with a reduction in urinary tract infections, hypertension, fatal coronary heart disease, venous thromboembolism, and cerebral infarct, but all these effects need to be confirmed by clinical trials. For other conditions such as bladder or colon cancer, evidence of a preventive effect of maintaining good hydration is not consistent (see Table 3 ).

Categories of evidence used in evaluating the quality of reports.

Data adapted from Manz. 104

Summary of evidence for association of hydration status with chronic diseases.

Categories of evidence: described in Table 2 .

Water consumption, water requirements, and energy intake are linked in fairly complex ways. This is partially because physical activity and energy expenditures affect the need for water but also because a large shift in beverage consumption over the past century or more has led to consumption of a significant proportion of our energy intake from caloric beverages. Nonregulatory beverage intake, as noted earlier, has assumed a much greater role for individuals. 19 This section reviews current patterns of water intake and then refers to a full meta-analysis of the effects of added water on energy intake. This includes adding water to the diet and water replacement for a range of caloric and diet beverages, including sugar-sweetened beverages, juice, milk, and diet beverages. The third component is a discussion of water requirements and suggestions for considering the use of mL water/kcal energy intake as a metric.

Patterns and trends of water consumption

Measurement of total fluid water consumption in free-living individuals is fairly new in focus. As a result, the state of the science is poorly developed, data are most likely fairly incomplete, and adequate validation of the measurement techniques used is not available. Presented here are varying patterns and trends of water intake for the United States over the past three decades followed by a brief review of the work on water intake in Europe.

There is really no existing information to support an assumption that consumption of water alone or beverages containing water affects hydration differentially. 3 , 105 Some epidemiological data suggest water might have different metabolic effects when consumed alone rather than as a component of caffeinated or flavored or sweetened beverages; however, these data are at best suggestive of an issue deserving further exploration. 106 , 107 As shown below, the research of Ershow et al. indicates that beverages not consisting solely of water do contain less than 100% water.

One study in the United States has attempted to examine all the dietary sources of water. 16 , 17 These data are cited in Table 4 as the Ershow study and were based on National Food Consumption Survey food and fluid intake data from 1977–1978. These data are presented in Table 4 for children aged 2–18 years (Panel A) and for adults aged 19 years and older (Panel B). Ershow et al. 16 , 17 spent a great deal of time working out ways to convert USDA dietary data into water intake, including water absorbed during the cooking process, water in food, and all sources of drinking water.

Beverage pattern trends in the United States for children aged 2–18 years and adults aged 19 years and older, (nationally representative).

Note: The data are age and sex adjusted to 1965.

Values stem from the Ershow calculations. 16

These researchers created a number of categories and used a range of factors measured in other studies to estimate the water categories. The water that is found in food, based on food composition table data, was 393 mL for children. The water that was added as a result of cooking (e.g., rice) was 95 mL. Water consumed as a beverage directly as water was 624 mL. The water found in other fluids, as noted, comprised the remainder of the milliliters, with the highest levels in whole-fat milk and juices (506 mL). There is a small discrepancy between the Ershow data regarding total fluid intake measures for these children and the normal USDA figures. That is because the USDA does not remove milk fats and solids, fiber, and other food constituents found in beverages, particularly juice and milk.

A key point illustrated by these nationally representative US data is the enormous variability between survey waves in the amount of water consumed (see Figure 1 , which highlights the large variation in water intake as measured in these surveys). Although water intake by adults and children increased and decreased at the same time, for reasons that cannot be explained, the variation was greater among children than adults. This is partly because the questions the surveys posed varied over time and there was no detailed probing for water intake, because the focus was on obtaining measures of macro- and micronutrients. Dietary survey methods used in the past have focused on obtaining data on foods and beverages containing nutrient and non-nutritive sweeteners but not on water. Related to this are the huge differences between the the USDA surveys and the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) performed in 1988–1994 and in 1999 and later. In addition, even the NHANES 1999–2002 and 2003–2006 surveys differ greatly. These differences reflect a shift in the mode of questioning with questions on water intake being included as part of a standard 24-h recall rather than as stand-alone questions. Water intake was not even measured in 1965, and a review of the questionnaires and the data reveals clear differences in the way the questions have been asked and the limitations on probes regarding water intake. Essentially, in the past people were asked how much water they consumed in a day and now they are asked for this information as part of a 24-h recall survey. However, unlike for other caloric and diet beverages, there are limited probes for water alone. The results must thus be viewed as crude approximations of total water intake without any strong research to show if they are over- or underestimated. From several studies of water and two ongoing randomized controlled trials performed by us, it is clear that probes that include consideration of all beverages and include water as a separate item result in the provision of more complete data.

Water consumption trends from USDA and NHANES surveys (mL/day/capita), nationally representative. Note: this includes water from fluids only, excluding water in foods. Sources for 1965, 1977–1978, 1989–1991, and 1994–1998, are USDA. Others are NHANES and 2005–2006 is joint USDA and NHANES.

Water consumption data for Europe are collected far more selectively than even the crude water intake questions from NHANES. A recent report from the European Food Safety Agency provides measures of water consumption from a range of studies in Europe. 4 , – 109 Essentially, what these studies show is that total water intake is lower across Europe than in the United States. As with the US data, none are based on long-term, carefully measured or even repeated 24-h recall measures of water intake from food and beverages. In an unpublished examination of water intake in UK adults in 1986–1987 and in 2001–2002, Popkin and Jebb have found that although intake increased by 226 mL/day over this time period, it was still only 1,787 mL/day in the latter period (unpublished data available from BP); this level is far below the 2,793 mL/day recorded in the United States for 2005–2006 or the earlier US figures for comparably aged adults.

A few studies have been performed in the United States and Europe utilizing 24-h urine and serum osmolality measures to determine total water turnover and hydration status. Results of these studies suggest that US adults consume over 2,100 mL of water per day while adults in Europe consume less than half a liter. 4 , 110 Data on total urine collection would appear to be another useful measure for examining total water intake. Of course, few studies aside from the Donald Study of an adolescent cohort in Germany have collected such data on population levels for large samples. 109

Effects of water consumption on overall energy intake

There is an extensive body of literature that focuses on the impact of sugar-sweetened beverages on weight and the risk of obesity, diabetes, and heart disease; however, the perspective of providing more water and its impact on health has not been examined. The literature on water does not address portion sizes; instead, it focuses mainly on water ad libitum or in selected portions compared with other caloric beverages. A detailed meta-analysis of the effects of water intake alone (i.e., adding additional water) and as a replacement for sugar-sweetened beverages, juice, milk, and diet beverages appears elsewhere. 111

In general, the results of this review suggest that water, when consumed in place of sugar-sweetened beverages, juice, and milk, is linked with reduced energy intake. This finding is mainly derived from clinical feeding studies but also from one very good randomized, controlled school intervention and several other epidemiological and intervention studies. Aside from the issue of portion size, factors such as the timing of beverage and meal intake (i.e., the delay between consumption of the beverage and consumption of the meal) and types of caloric sweeteners remain to be considered. However, when beverages are consumed in normal free-living conditions in which five to eight daily eating occasions are the norm, the delay between beverage and meal consumption may matter less. 112 , – 114

The literature on the water intake of children is extremely limited. However, the excellent German school intervention with water suggests the effects of water on the overall energy intake of children might be comparable to that of adults. 115 In this German study, children were educated on the value of water and provided with special filtered drinking fountains and water bottles in school. The intervention schoolchildren increased their water intake by 1.1 glasses/day ( P < 0.001) and reduced their risk of overweight by 31% (OR = 0.69, P = 0.40).

Classically, water data are examined in terms of milliliters (or some other measure of water volume consumed per capita per day by age group). This measure does not link fluid intake and caloric intake. Disassociation of fluid and calorie intake is difficult for clinicians dealing with older persons with reduced caloric intake. This milliliter water measure assumes some mean body size (or surface area) and a mean level of physical activity – both of which are determinants of not only energy expenditure but also water balance. Children are dependent on adults for access to water, and studies suggest that their larger surface area to volume ratio makes them susceptible to changes in skin temperatures linked with ambient temperature shifts. 116 One option utilized by some scholars is to explore food and beverage intake in milliliters per kilocalorie (mL/kcal), as was done in the 1989 US recommended dietary allowances. 4 , 117 This is an option that is interpretable for clinicians and which incorporates, in some sense, body size or surface area and activity. Its disadvantage is that water consumed with caloric beverages affects both the numerator and the denominator; however, an alternative measure that could be independent of this direct effect on body weight and/or total caloric intake is not presently known.

Despite its critical importance in health and nutrition, the array of available research that serves as a basis for determining requirements for water or fluid intake, or even rational recommendations for populations, is limited in comparison with most other nutrients. While this deficit may be partly explained by the highly sensitive set of neurophysiological adaptations and adjustments that occur over a large range of fluid intakes to protect body hydration and osmolarity, this deficit remains a challenge for the nutrition and public health community. The latest official effort at recommending water intake for different subpopulations occurred as part of the efforts to establish Dietary Reference Intakes in 2005, as reported by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academies of Science. 3 As a graphic acknowledgment of the limited database upon which to express estimated average requirements for water for different population groups, the Committee and the Institute of Medicine stated: “While it might appear useful to estimate an average requirement (an EAR) for water, an EAR based on data is not possible.” Given the extreme variability in water needs that are not solely based on differences in metabolism, but also on environmental conditions and activities, there is not a single level of water intake that would assure adequate hydration and optimum health for half of all apparently healthy persons in all environmental conditions. Thus, an adequate intake (AI) level was established in place of an EAR for water.

The AIs for different population groups were set as the median water intakes for populations, as reported in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys; however, the intake levels reported in these surveys varied greatly based on the survey years (e.g., NHANES 1988–1994 versus NHANES 1999–2002) and were also much higher than those found in the USDA surveys (e.g., 1989–1991, 1994–1998, or 2005–2006). If the AI for adults, as expressed in Table 5 , is taken as a recommended intake, the wisdom of converting an AI into a recommended water or fluid intake seems questionable. The first problem is the almost certain inaccuracy of the fluid intake information from the national surveys, even though that problem may also exist for other nutrients. More importantly, from the standpoint of translating an AI into a recommended fluid intake for individuals or populations, is the decision that was made when setting the AI to add an additional roughly 20% of water intake, which is derived from some foods in addition to water and beverages. While this may have been a legitimate effort to use total water intake as a basis for setting the AI, the recommendations that derive from the IOM report would be better directed at recommendations for water and other fluid intake on the assumption that the water content of foods would be a “passive” addition to total water intake. In this case, the observations of the dietary reference intake committee that it is necessary for water intake to meet needs imposed by metabolism and environmental conditions must be extended to consider three added factors, namely body size, gender, and physical activity. Those are the well-studied factors that allow a rather precise measurement and determination of energy intake requirements. It is, therefore, logical that those same factors might underlie recommendations to meet water intake needs in the same populations and individuals. Consideration should also be given to the possibility that water intake needs would best be expressed relative to the calorie requirements, as is done regularly in the clinical setting, and data should be gathered to this end through experimental and population research.

Water requirements expressed in relation to energy recommendations.

AI for total fluids derived from dietary reference intakes for water, potassium, sodium, chloride, and sulphate.

Ratios for water intake based on the AI for water in liters/day calculated using EER for each range of physical activity. EER adapted from the Institute of Medicine Dietary Reference Intakes Macronutrients Report, 2002.

It is important to note that only a few countries include water on their list of nutrients. 118 The European Food Safety Authority is developing a standard for all of Europe. 105 At present, only the United States and Germany provide AI values for water. 3 , 119

Another approach to the estimation of water requirements, beyond the limited usefulness of the AI or estimated mean intake, is to express water intake requirements in relation to energy requirements in mL/kcal. An argument for this approach includes the observation that energy requirements for each age and gender group are strongly evidence-based and supported by extensive research taking into account both body size and activity level, which are crucial determinants of energy expenditure that must be met by dietary energy intake. Such measures of expenditure have used highly accurate methods, such as doubly labeled water; thus, estimated energy requirements have been set based on solid data rather than the compromise inherent in the AIs for water. Those same determinants of energy expenditure and recommended intake are also applicable to water utilization and balance, and this provides an argument for pegging water/fluid intake recommendations to the better-studied energy recommendations. The extent to which water intake and requirements are determined by energy intake and expenditure is understudied, but in the clinical setting it has long been practice to supply 1 mL/kcal administered by tube to patients who are unable to take in food or fluids. Factors such as fever or other drivers of increased metabolism affect both energy expenditure and fluid loss and are thus linked in clinical practice. This concept may well deserve consideration in the setting of population intake goals.

Finally, for decades there has been discussion about expressing nutrient requirements per 1,000 kcal so that a single number would apply reasonably across the spectrum of age groups. This idea, which has never been adopted by the Institute of Medicine and the National Academies of Science, may lend itself to an improved expression of water/fluid intake requirements, which must eventually replace the AIs. Table 5 presents the IOM water requirements and then develops a ratio of mL/kcal based on them. The European Food Safety Agency refers positively to the possibility of expressing water intake recommendations in mL/kcal as a function of energy requirements. 105 Outliers in the adult male categories, which reach ratios as high as 1.5, may well be based on the AI data from the United States, which are above those in the more moderate and likely more accurate European recommendations.

The topic of utilizing mL/kcal to examine water intake and water gaps is explored in Table 6 , which takes the full set of water intake AIs for each age-gender grouping and examines total intake. The data suggest a high level of fluid deficiency. Since a large proportion of fluids in the United States is based on caloric beverages and this proportion has changed markedly over the past 30 years, fluid intake increases both the numerator and the denominator of this mL/kcal relationship. Nevertheless, even using 1 mL/kcal as the AI would leave a gap for all children and adolescents. The NHANES physical activity data were also translated into METS/day to categorize all individuals by physical activity level and thus varying caloric requirements. Use of these measures reveals a fairly large fluid gap, particularly for adult males as well as children ( Table 6 ).

Water intake and water intake gaps based on US Water Adequate Intake Recommendations (based on utilization of water and physical activity data from NHANES 2005–2006).

Note: Recommended water intake for actual activity level is the upper end of the range for moderate and active.

A weighted average for the proportion of individuals in each METS-based activity level.

This review has pointed out a number of issues related to water, hydration, and health. Since water is undoubtedly the most important nutrient and the only one for which an absence will prove lethal within days, understanding of water measurement and water requirements is very important. The effects of water on daily performance and short- and long-term health are quite clear. The existing literature indicates there are few negative effects of water intake while the evidence for positive effects is quite clear.

Little work has been done to measure total fluid intake systematically, and there is no understanding of measurement error and best methods of understanding fluid intake. The most definitive US and European documents on total water requirements are based on these extant intake data. 3 , 105 The absence of validation methods for water consumption intake levels and patterns represents a major gap in knowledge. Even varying the methods of probing in order to collect better water recall data has been little explored.

On the other side of the issue is the need to understand total hydration status. There are presently no acceptable biomarkers of hydration status at the population level, and controversy exists about the current knowledge of hydration status among older Americans. 6 , 120 Thus, while scholars are certainly focused on attempting to create biomarkers for measuring hydration status at the population level, the topic is currently understudied.

As noted, the importance of understanding the role of fluid intake on health has emerged as a topic of increasing interest, partially because of the trend toward rising proportions of fluids being consumed in the form of caloric beverages. The clinical, epidemiological, and intervention literature on the effects of added water on health are covered in a related systematic review. 111 The use of water as a replacement for sugar-sweetened beverages, juice, or whole milk has clear effects in that energy intake is reduced by about 10–13% of total energy intake. However, only a few longer-term systematic interventions have investigated this topic and no randomized, controlled, longer-term trials have been published to date. There is thus very minimal evidence on the effects of just adding water to the diet and of replacing water with diet beverages.

There are many limitations to this review. One certainly is the lack of discussion of potential differences in the metabolic functioning of different types of beverages. 121 Since the literature in this area is sparse, however, there is little basis for delving into it at this point. A discussion of the potential effects of fructose (from all caloric sweeteners when consumed in caloric beverages) on abdominal fat and all of the metabolic conditions directly linked with it (e.g., diabetes) is likewise lacking. 122 , – 125 A further limitation is the lack of detailed review of the array of biomarkers being considered to measure hydration status. Since there is no measurement in the field today that covers more than a very short time period, except for 24-hour total urine collection, such a discussion seems premature.

Some ways to examine water requirements have been suggested in this review as a means to encourage more dialogue on this important topic. Given the significance of water to our health and of caloric beverages to our total energy intake, as well as the potential risks of nutrition-related noncommunicable diseases, understanding both the requirements for water in relation to energy requirements, and the differential effects of water versus other caloric beverages, remain important outstanding issues.

This review has attempted to provide some sense of the importance of water to our health, its role in relationship to the rapidly increasing rates of obesity and other related diseases, and the gaps in present understanding of hydration measurement and requirements. Water is essential to our survival. By highlighting its critical role, it is hoped that the focus on water in human health will sharpen.

The authors wish to thank Ms. Frances L. Dancy for administrative assistance, Mr. Tom Swasey for graphics support, Dr. Melissa Daniels for assistance, and Florence Constant (Nestle's Water Research) for advice and references.

This work was supported by the Nestlé Waters, Issy-les-Moulineaux, France, 5ROI AGI0436 from the National Institute on Aging Physical Frailty Program, and NIH R01-CA109831 and R01-CA121152.

Declaration of interest

The authors have no relevant interests to declare.

Nicolaidis S . Physiology of thirst . In: Arnaud MJ , ed. Hydration Throughout Life . Montrouge: John Libbey Eurotext ; 1998 : 247 .

Google Scholar

Jequier E Constant F . Water as an essential nutrient: the physiological basis of hydration . Eur J Clin Nutr. 2010 ; 64 : 115 – 123 .

Institute of Medicine . Panel on Dietary Reference Intakes for Electrolytes and Water. Dietary Reference Intakes for Water, Potassium, Sodium, Chloride, and Sulfate . Washington, DC: The National Academies Press ; 2005 .

Manz F Wentz A . Hydration status in the United States and Germany . Nutr Rev. 2005 ; 63 :(Suppl): S55 – S62 .

European Food Safety Authority . Scientific opinion of the Panel on Dietetic Products Nutrition and Allergies. Draft dietary reference values for water . EFSA J. 2008 : 2 – 49 .

Stookey JD . High prevalence of plasma hypertonicity among community-dwelling older adults: results from NHANES III . J Am Diet Assoc. 2005 ; 105 : 1231 – 1239 .

Armstrong LE . Hydration assessment techniques . Nutr Rev. 2005 ; 63 (Suppl): S40 – S54 .

Bar-David Y Urkin J Kozminsky E . The effect of voluntary dehydration on cognitive functions of elementary school children . Acta Paediatr. 2005 ; 94 : 1667 – 1673 .

Shirreffs S . Markers of hydration status . J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2000 ; 40 : 80 – 84 .

Popowski L Oppliger R Lambert G Johnson R Johnson A Gisolfi C . Blood and urinary measures of hydration status during progressive acute dehydration . Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 ; 33 : 747 – 753 .

Bar-David Y Landau D Bar-David Z Pilpel D Philip M . Urine osmolality among elementary schoolchildren living in a hot climate: implications for dehydration . Ambulatory Child Health. 1998 ; 4 : 393 – 397 .

Fadda R Rapinett G Grathwohl D Parisi M Fanari R Schmitt J . The Benefits of Drinking Supplementary Water at School on Cognitive Performance in Children . Washington, DC: International Society for Developmental Psychobiology ; 2008 : Abstract from poster session at the 41st Annual Conference of International Society for Psychobiology. Abstracts published in: Developmental Psychobiology 2008: v. 50(7): 726 . http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/121421361/PDFSTART

Eckhardt CL Adair LS Caballero B , et al . Estimating body fat from anthropometry and isotopic dilution: a four-country comparison . Obes Res. 2003 ; 11 : 1553 – 1562 .

Moreno LA Sarria A Popkin BM . The nutrition transition in Spain: a European Mediterranean country . Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002 ; 56 : 992 – 1003 .

Lee MJ Popkin BM Kim S . The unique aspects of the nutrition transition in South Korea: the retention of healthful elements in their traditional diet . Public Health Nutr. 2002 ; 5 : 197 – 203 .

Ershow AG Brown LM Cantor KP . Intake of tapwater and total water by pregnant and lactating women . Am J Public Health. 1991 ; 81 : 328 – 334 .

Ershow AG Cantor KP . Total Water and Tapwater Intake in the United States: Population-Based Estimates of Quantities and Sources . Bethesda, MD: FASEB/LSRO ; 1989 .