Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Nutrition articles from across Nature Portfolio

Nutrition is the organic process of nourishing or being nourished, including the processes by which an organism assimilates food and uses it for growth and maintenance.

Latest Research and Reviews

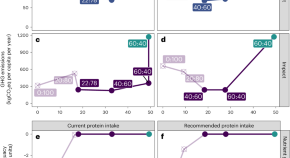

Circular food system approaches can support current European protein intake levels while reducing land use and greenhouse gas emissions

Almost half of land use and nearly three-quarters of greenhouse gas emissions can be reduced by adopting circularity principles and reducing the ratio of animal-sourced protein to plant-sourced protein from 60:40 to 40:60 in European diets.

- Wolfram J. Simon

- Renske Hijbeek

- Hannah H. E. van Zanten

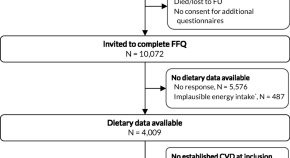

Dietary habits and compliance with dietary guidelines in patients with established cardiovascular disease

- Nadia E. Bonekamp

- Johanna M. Geleijnse

- F. L. J. Visseren

Comparison of dehydration systems in quality and chemical effects on sunflower seeds

- A. A. Ortiz-Hernandez

- M. A. Araiza-Esquivel

- J. J. Ortega-Sigala

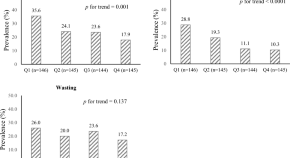

Association between modified youth healthy eating index and nutritional status among Iranian children in Zabol city: a cross-sectional study

- Farshad Amirkhizi

- Mohammad-Reza Jowshan

- Somayyeh Asghari

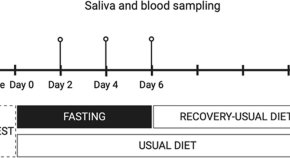

Exploring the effect of prolonged fasting on kynurenine pathway metabolites and stress markers in healthy male individuals

- Varvara Louvrou

- Rima Solianik

- Sophie Erhardt

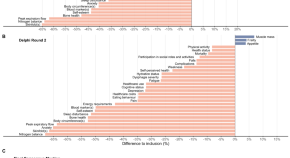

Critical outcomes to be included in the Core Outcome Set for nutritional intervention studies in older adults with malnutrition or at risk of malnutrition: a modified Delphi Study

- Nuno Mendonça

- Christina Avgerinou

- Marjolein Visser

News and Comment

Hunger on campus: why US PhD students are fighting over food

Graduate students are relying on donated and discounted food in the struggle to make ends meet.

- Laurie Udesky

Personalized nutrition as the catalyst for building food-resilient cities

Data-driven personalized nutrition (PN) can address the complexities of food systems in megacities, aiming to enhance food resilience. By integrating individual preferences, health data and environmental factors, PN can optimize food supply chains, promote healthier dietary choices and reduce food waste. Collaborative efforts among stakeholders are essential to implement PN effectively.

- Anna Ziolkovska

- Christian Sina

Seafood access in Kiribati

- Annisa Chand

Metabolic product of excess niacin is linked to increased risk of cardiovascular events

A metabolic product of excess niacin promotes vascular inflammation in preclinical models and is associated with increased rates of major adverse cardiovascular events in humans.

- Gregory B. Lim

Introducing meat–rice: grain with added muscles beefs up protein

The laboratory-grown food uses rice as a scaffold for cultured meat.

- Jude Coleman

‘Blue foods’ to tackle hidden hunger and improve nutrition

Aquatic foods have been overlooked in moves to end food insecurity. That needs to change, says Christopher Golden.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- BMJ NPH Collections

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Online First

- Finding the place for nutrition in healthcare education and practice

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5048-2939 Ebiambu Agwara 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2920-9847 Kathy Martyn 1 ,

- Elaine Macaninch 1 ,

- Wanja Nyaga 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6589-4880 Luke Buckner 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0154-1960 Breanna Lepre 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4555-1407 Celia Laur 1 and

- http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3295-168X Sumantra Ray 1 , 2 , 3

- 1 NNEdPro Global Institute for Food, Nutrition and Health , Cambridge , UK

- 2 School of Biomedical Sciences , Ulster University , Coleraine , UK

- 3 Fitzwilliam College , University of Cambridge , Cambridge , UK

- Correspondence to Professor Sumantra Ray; s.ray{at}nnedpro.org.uk

Background Malnutrition continues to impact healthcare outcomes, quality of life and costs to healthcare systems. The implementation of nutrition care in healthcare practice may improve health outcomes for patients and the community. This paper describes the iterative development and implementation of nutrition medical education resources for doctors and healthcare professionals in England. These resources are part of the Nutrition Education Policy for Healthcare Practice initiative.

Method Action research methodology was employed to develop and implement nutrition education workshops for medical students and doctors. The workshop was developed iteratively by an interdisciplinary project team, and the content was initially based on the General Medical Council outcomes for graduates. It was evaluated using quantitative evaluation tools and informal qualitative feedback captured from attendees using tools provided by the host organisations and developed by the roadshow team.

Results A total of 6 nutrition education workshops were delivered to 169 participants. This simple educational package demonstrated potential for delivery in different healthcare settings; however, formal feedback was difficult to obtain. Evaluation results indicate that workshops were better received when delivered by doctors known to the participants and included local context and examples. Reported barriers to the workshops included difficulty for participants in finding the time to attend, beliefs that peers gave a low priority to nutrition and uncertainty about professional roles in the delivery of nutrition care.

Conclusion A key outcome of this project was the development of resources for nutrition training of doctors, adapted to local needs. However, relatively low attendance and multiple barriers faced in the delivery of these workshops highlight that there is no ideal ‘place’ for nutrition training in current healthcare teaching. Interprofessional education, through relevant clinical scenarios may increase awareness of the importance of nutrition in healthcare, support the alignment of health professional roles and improve subsequent knowledge and skills.

- nutrition assessment

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request.

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjnph-2023-000692

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

There is a great need for more nutrition within medical education, as well as a need for greater clarity of a doctor’s role in nutritional care and when to refer for specialist advice.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The development and implementation of resources for nutrition training of doctors adapted to local needs.

This paper shows that there is no one ‘place’ for nutrition; hence, the Nutrition Implementation Coalition provides a ‘hub’ of material and expertise adapted to the needs of the providers and settings.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The need for multiprofessional ‘hub’ of material and expertise that can support medical schools and healthcare professionals who may lack faculty to develop and implement nutrition education in practice.

Introduction

Malnutrition comprises the double burden of undernutrition and overnutrition including micronutrient deficiencies, which together continue to impact the healthcare outcomes and quality of life of individuals, as well as costs to the healthcare systems. 1 For example, in hospitals, rates of malnutrition remain high, averaging 35% internationally, and in 2015, it was estimated that malnutrition in England cost the National Health Service (NHS) almost £20 billion. 2

Implementing nutritional care in practice requires the application of nutrition knowledge and skills, and ideally this care is individualised to health priorities, patients’ goals, preferences and sociocultural context. 3 Dietitians are specifically trained to provide nutrition care; however, due to their limited numbers, they rely on nutritional problems being recognised by others with subsequent clinical referral. Furthermore, other health professionals, such as doctors and nurses, are well placed to initiate nutrition care and provide support of advice as they tend to have regular contact with patients and doctors are perceived by patients as a credible source of nutrition information. 4 This provides opportunities for discussions and nutrition screening. 5

However, although doctors, nurses and other health professionals perceive nutrition as important, they require the knowledge, skills and confidence to incorporate nutrition as part of patient care or to identify when an individual might benefit from a referral to a dietitian. Importantly, medical students and doctors' welcome further nutrition education, as professional bodies internationally now recommending doctors discuss diet with their patients. 6–8 Despite this perceived need, and continual focus on improving medical nutrition education, undergraduate or preregistration nutrition education for doctors is limited. 9 Moreover, there is limited information available on nutrition learning objectives or outcomes, or teaching methods. Internationally, only 45% of medical education accreditation and curriculum guidance was found to even mention nutrition, 10 and to this end, there is limited incentive for education providers to include nutrition in medical training.

In the UK, the responsibility for postgraduate medical education (PGME) is devolved to the respective professional bodies in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 11 The programmes are commonly referred to as foundation programmes, core training and specialty training. 12 During foundation training, junior doctors have protected learning time, and nutrition is identified as part of the syllabus followed in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. 13 Separate curriculum exists for 32 specialty training programmes in the UK. 14 In specialty PGME, nutrition content varies depending on the perceived relevance of nutrition to the medical specialty with limited mandated content. Table 1 shows examples of where nutrition is mandated in UK postgraduate medical curriculum. In 2021, with the aim to standardise nutrition education in undergraduate medical training, a working party convened by the Association for Nutrition (AfN) published the nutrition curriculum for UK undergraduate medical students. 15 This builds on the UK General Medical Council (GMC) ‘outcomes for graduates’, 16 which stipulates the core competencies for medical graduates in the UK. However, ways to support systematic integration of nutrition into medical education are required, as there is currently no requirement to include nutrition in medical training. Even if nutrition education can be integrated into current medical training, there remains a need for nutrition education and ongoing support for medical doctors who are already qualified. 17

- View inline

Examples of where nutrition is mandated in UK postgraduate medical curriculum

With these challenges in mind, in March 2019, the NNEdPro Global Institute for Food, Nutrition and Health, which has a key focus on medical nutrition education, launched a nutrition education package as part of their ‘Nutrition Education Policy in Healthcare Practice (NEPHELP)’ project. The aims of NEPHELP were: (1) to develop, evaluate and implement nutrition education workshops and educational resources; (2) to understand the feasibility and acceptability of a nutrition education model via participant and facilitator feedback; and (3) to gain insights into where doctors and health professionals see the place for nutrition in their education. This paper primarily focuses on aim 1, and to a lesser extent, secondarily focuses on aims 2 and 3.

This paper describes the iterative development and delivery of a nutrition education workshop for junior doctors and health professionals piloted in Glasgow, then delivered at six sites across England. Feasibility and acceptability of the workshops are explored along with reflections on the place for nutrition in medical and healthcare profession education.

Methodological approach

Study design.

The development of NEPHELP used action research methodology, 18 which is considered a pragmatic approach to instigate change. The action research cycle includes problem identification (including reflection), planning, action (implementation of change and monitoring) and evaluation or reflection before starting a new situation analysis. Action research was considered rigorous in this context because it supported the aim of exploring both enablers and barriers to the implementation of nutrition education in medical practice with the research participants. 19

The project was conducted in two stages, including (1) an initial pilot workshop in Glasgow, followed by (2) the delivery of workshops across England as part of the ‘NEPHELP Nutrition Training Roadshow’ ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Place for nutrition paper.

The NEPHELP team

The interdisciplinary teaching team consisted of medical doctors, a registered dietitian, associate and registered nutritionists, a registered nurse, academics and education professionals, all members of the NNEdPro Global Institute. The teaching team developed and delivered the workshops and the evaluation tool.

Stage 1: piloting the NEPHELP workshop

Workshop participants and recruitment.

This was conducted with a multiprofessional international audience attending the BMJ Quality and Safety in Healthcare conference at Glasgow in 2019. Participants voluntarily signed up for a 4-hour NEPHELP nutrition workshop.

Workshop content

The initial workshop content was based on GMC expected learning outcomes for medical graduates, 16 postgraduate curricula 13 20 and perceived nutrition priorities within clinical settings, based on the educational and professional experiences of the interdisciplinary team, and included an overview of nutrition science related to clinical care Case-based discussions were used to assist with the translation of nutrition knowledge into practice.

The workshop aimed for participants to: (1) understand key principles of human nutrition, (2) understand the importance of balanced diet for health, and in illness, recognise factors that impact on equitable access to healthy food, (3) explore how individuals can include nutritional screening, care and dietetic referral into their practice and (4) provide feedback on the acceptability of the workshop as a strategy for delivering nutrition education.

The NEPHELP evaluation tool included quantitative and open-ended questions, which were designed to explore the knowledge, attitude and practices in nutritional care, and perceptions of requirements for nutrition in medical education. Feedback on the workshop content and ideas on how the programme could be improved were also gathered to inform further development of the workshop.

Stage 2: delivering the NEPHELP ‘Nutrition Training Roadshow’ across England

In this second stage, termed the ‘roadshow’, the NEPHELP workshop was delivered, evaluated and adapted to six healthcare settings across England. The NEPHELP roadshow was delivered in three formats: (1) as a part of mandatory training within health settings (hospitals, primary care etc), (2) a standalone workshop or (3) as an invited workshop delivered as part of a general GP training day and organised by an external group.

Participants and recruitment

Workshop participants were invited by the PGME and NHS contacts who also circulated workshop information. The delivery of stage 2 workshops varied depending on NEPHELP facilitator availability, with some being codelivered between the NEPHELP team and local dietitians or doctors.

Following each iteration of the workshop, evaluation forms and informal reflections were captured to inform the refinement of workshop content. The NEPHELP evaluation tool (described above) was adapted to the audience in each workshop. Additional feedback was provided by PGME faculty through their own evaluation forms. This ‘in-house’ feedback differed for each centre, was designed and collected independently but shared with the NEPHELP team. NEPHELP observers took notes during workshop discussions, and after each workshop, the facilitators listened to the observations and critically reflected on the session.

The iterative nature of the action research methodology allowed for the continuous review of data as it was collected. Quantitative data collected through NEPHELP evaluation tool and PGME forms were analysed descriptively. Qualitative data collected from open questions in the evaluation tool, PGME forms, notes taken during the workshop by observers and postworkshop critical reflection sessions were subject to content analysis, 21 an approach widely used in qualitative research. Analysis was completed by two members of the NEPHELP team, who did not have prior relationships with any of the participants. EM and KM independently grouped the material into topics using a word processing package, and the main topics were then discussed with the wider NEPHELP team.

The initial 4-hour workshop was piloted in Glasgow in March 2019, with 40 interdisciplinary participants at the BMJ Quality and Safety in Healthcare conference. Following the pilot, the workshop was modified based on participant evaluations (n=4), oral feedback from participants and the NEPHELP team reflections. The roadshow was conducted between March 2019 and February 2020, with workshops conducted at 6 locations across England with 169 participants and a total of 13.5 hours ( table 2 ).

Overview of completed NEPHELP workshops (March 2019 to February 2020)

At the end of the workshop, five (12.5%) NEPHELP evaluation questionnaires were returned from two doctors working in internal medicine, one GP, one nurse and one service manager ( table 2 ). While all respondents agreed that the workshop was useful for themselves and their colleagues, there were suggestions that the workshop included greater involvement of community care and increased focus on elements of nutrition care across the care continuum. Following this feedback, the focus for NEPHELP to also consider general practitioners and other healthcare professionals was widened.

The total response rate for the NEPHELP evaluation tool was 12.5% for the pilot and 10% for subsequent workshops. In addition, 15% completed PGME evaluation tools, and 26% of participants contributed some feedback but the heterogenic nature meant there was limited consistency in evaluation methods between each session. The combined PGME and NEPHELP evaluation data are reported individually in table 3 .

Combined PGME and NEPHELP evaluation data

The roadshow

Of the six workshops held during the Roadshow, three were mandated sessions and three were voluntary, as summarised in table 2 . Mandated sessions had much higher attendance; however, there was a low response rate overall to the evaluation questionnaires. Feedback from each session was used to inform future sessions ( table 4 ).

Summary of evaluation findings from each workshop

Multiple methods for delivery were tested, spanning rapid sessions in existing training, to full day workshops, with no format perceived as being ideal. The variation in format addressed the logistical constraints on time and location, and the need to fit the workshops within existing programmes of study. For example, a full day session requested by a GP trainer (Essex) was held on a weekend, and although advertised and free, only one person attended. In contrast, the rapid session (East of England) attended by 60 participants aimed to see if the training could be added into an existing event, and if all learning objectives could be covered in the shorter time. Formal feedback from this session was limited.

NEPHELP evaluation responses

The mandated teaching in London at a teaching hospital for foundation year 2 had the highest response rate to the NEPHELP evaluation tool at 52% (n=17). Nine participants (53%) reported receiving no previous nutrition education, while eight (47%) recalled some nutrition training in their medical education. Of participants who reported receiving nutrition training, five reported receiving this education during medical school, one from a self-selected module, one during a biomedical sciences degree and one elsewhere in their foundation training. All participants felt that the clinical nutritional needs of patients were not prioritised, and as a result were poorly addressed in the hospital setting. As noted by one participant, nutrition is ‘ certainly, something that could be improved ’, but felt that it was ‘ unlikely to be top priority in a consultation ’.

When asked to give an example of where nutritional needs for a patient were met, 41% (n=7) recalled examples of acute nutrition, namely, either nasogastric or parenteral nutrition, 29% (n=5) reported seeing clinical benefit from malnutrition treatments and three specifically mentioned the benefits of dietitian involvement in secondary care. One participant noted examples “In upper GI (gastrointestinal) surgery a lot of patients were on TPN (total parenteral nutrition) or NG/NJ (naso gastric/naso jejunal) feeds.” Another mentioned “Gastro ward with dietitian input (eg, TPN patient).”

When these participants were asked about the barriers to effective nutritional care, 15 (88%) identified time as a barrier, 11 (61%) identified a lack of knowledge, 8 (47%) identified a lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities and 7 (41%) perceived a lack of interest from colleagues as a barrier to such care in practice. One participant said, “I'm aware as a junior in A&E [Accident and Emergency] it is quite slow spending time taking a good diet history and giving advice would make consultations even longer.” When questioned about including nutritional screening or history taking as part of their practice respondents reported the following reasons a lack of nutrition training (n=6, 35%), time pressures for doctors (n=5, 29%) and some participants perceived nutrition care as a dietitian’s role (n=4, 24%). Comments included, “Poor training and perception that nutrition is the preserve of dietitians. Time not allocated”. Another focused on the lack of education: “Little education in med school. Not much time. Unclear whose role it is.” The lack of interest and importance was also mentioned: “Both knowledge on importance but also lack of interest in implementing what little people do know about nutrition.”

Most respondents (88%) felt doctors had a role in nutrition care with half (n=9) identifying the role of a doctor in initial assessment to identify nutrition risks and a third (n=5) indicating the importance of onward referral to the dietitian as part of their role. As one participant mentioned, there are “Very few specialists so it needs to be taken responsibility for by all staff.” They saw their role as the “Assessing, advising, signposting and referring.” Another participant focused on actions to take, particularly regarding handover. “Reorganising when and where referrals are required. Risk assessment. Improving inter-team handover.” While one questioned the role of a doctor in nutrition care, highlighting bigger societal issues. “Some roles, but the most significant barriers lie in public health policy, food poverty and education.”

Most participants in this group (16/17) felt that nutrition education should be an essential element of medical training and found the content of the workshop relevant. When asked about the most appropriate timing of this nutrition education, 12 participants (71%) felt this should be linear, with nutrition education increasing from medical school to junior doctor, while 3 participants (18%) felt nutrition education was most relevant to junior doctors. Two participants (12%) felt nutrition training was most relevant to medical students and would be best placed in undergraduate medical education. Seven of the participants (41%) valued skill-based nutrition education and case-based learning. However, opinions varied on what was relevant nutrition content, but included, ‘practical examples and how to put into practice’ , ‘ important from Global public health perspective’, ‘common things in hospital for example, refeeding’, ‘eating disorders, intuitive eating, diet culture and how best to educate without promoting diet culture’. In contrast, one participant did not perceive nutrition as relevant in medical training as “Patient education and school age education plus socioeconomic factors far outweigh medical input” and others felt that “didactic teaching [was] less useful.”

Mandated versus voluntary attendance

Mandated sessions were better attended and evaluated. In the UK, all junior doctors have protected learning time to attend mandated teaching. 11 13 20 22 NEPHELP workshops were delivered in mandated teaching during two FY2 training sessions and one GP trainee protected teaching session. In contrast, attendance at non-mandated training was particularly poor. Participants commented on the difficulties experienced in attending non-mandated sessions due to professional and personal pressures. “If I don’t have to go it’s not something I would attend, at the end of a week I have other priorities”.

Training was generally better received when local doctors were present and less well received when other healthcare professionals individually delivered the same content. The perception was that training would have been better received if a medical role model acted as a peer educator, for example, where teaching was codelivered with another GP trainee as opposed to being delivered by non-medical members of the NEPHELP team who are unknown to the participants. Limited opportunity for interprofessional education (IPE) and poor collaboration in nutrition care across health systems was also identified as a barrier to effective nutrition care practice.

Low prioritisation of nutrition in clinical care

Many participants identified a low priority given to nutrition in clinical care. Foundation year trainees recognised that nutrition is not addressed adequately in clinical practice but did not have recommendations for how it could be improved, citing logistical challenges such as a lack of priority, time and senior recognition of nutrition in patient management, care planning and treatment. They also felt that there was limited time available for education and variation in opinion on the most important aspects of nutrition. Some topics rated as important were based on prior clinical experiences such as working in a ‘gastro’ environment, or seeing TPN/NG feeding, while others perceived a topic to be importance based on personal interests, such as the ‘low carbohydrate diet ’ . Many participants indicated that their personal nutrition knowledge, level of interest and social media informed their practice.

Lack of clarity on roles and responsibilities in nutrition care

While participants recognised the importance of nutrition, they remained unclear on their role and scope of practice (as doctors) in nutrition care. Participants attending the primary care training day did not feel that a session on nutrition was appropriate for them as GPs and perceived nutrition as relating solely to healthy eating. Many Foundation doctors found it challenging to address nutritional issues in practice and indicated that their focus was the immediate medical concern. Some participants believed that public health professionals should hold more responsibility than doctors in the delivery of nutrition care. Addressing misconceptions about the role of diet in the prevention and management of non-communicable diseases, its role in medical treatment across all settings, and how different members of the multi professional healthcare team can work synergistically to achieve favourable patient outcomes, may raise the profile of nutrition in medical practice.

It is recognised that collaboration across professions such as registered nurses, doctors and allied health professionals fosters a positive and rewarding practice environment and improves patient outcomes. 23 This collaboration has previously been identified by medical students and junior doctors with an interest in nutrition as a key factor to support the integration of nutrition into medical practice. 24

Interprofessional education (IPE) is recognised by the WHO as an ‘innovative strategy that will play an important role in mitigating the global health workforce crisis’ and address professional silo working. 25 The cross-cutting nature of nutrition, and its involvement in the promotion of health and prevention and management of disease, reiterates that nutrition should be a core element of all healthcare professional’s education. Ideally, it should be ideally through an IPE lens to foster a multidisciplinary approach in practice.

Challenges for multiprofessional learning, working and collaboration

During NEPHELP, there was a reluctance from PGME providers to include non-medical professionals within junior doctor-protected sessions, limiting the opportunity and scope for IPE. Moreover, there was a perception that the NEPHELP workshop was not as well received when a medical doctor was not part of the teaching team. For trainees, the historic paucity of nutrition education within medical training limits the number of role models who can model and advocate for nutrition care. 8 26 However, research has identified the importance of professional role models to support learning in medical education and how this authenticates the place for content and its relevance to clinical practice. 27

Using action research methodology, the NEPHELP team set out to develop an educational package based on GMC outcomes for graduates, which could be delivered in different healthcare settings. In addition, they sought to understand where doctors and health professionals see nutrition as fitting into their educational journey and considered the feasibility of this workshop approach.

Lessons learnt from NEPHELP

From this work, we recognise that there is no one ‘place’ for nutrition, but there is a need for clear curriculum content at all stages of a doctor’s education.

Undergraduate and postgraduate nutrition curriculum development

The recently published undergraduate nutrition curriculum for medical doctors represents a consensus among multiple stakeholders, nutrition professionals and medical royal colleges on the required nutrition competencies for medical graduate. 28 This benchmarks what should be taught in medical education as an accompaniment to GMC learning outcomes for graduates. In addition, the 2021 Foundation curriculum 13 supports engagement with third-sector organisations, which are at the forefront in providing services to support health prevention including services to support education or access to healthy foods or services directly addressing food poverty.

Clearer postgraduate mandated nutrition competencies within existing PGME curriculum may help to better elucidate key nutrition knowledge and skills for practicing doctors, which could be a useful accompaniment to the foundation doctor’s curriculum, helping to increase validity and visibility of nutrition while also clarifying the role of medical doctors and the wider MDT. However, F2 participants completing the NEPHELP evaluation tool indicated a preference for more linear nutrition education, suggesting a desire to advance nutrition along with other medical skills but with a clear preference for more clinically focused, case-based teaching.

To demonstrate interprofessional roles and responsibilities of care, there is a need for clinically relevant scenarios more closely aligned to existing roles and workplace expectations to ‘nudge’ professionals to raise the profile of nutrition in their practice, as part of an MDT approach. Educating doctors in the absence of the MDT may not address the issue.

Organisations such as NNEdPro, the AfN and GMC can work with educators, including medical schools and foundation programmes to create a framework for trainees to work towards achieving the role and competencies they outline.

Furthermore, recent findings from Lepre et al , 29 reflecting the expressed needs of end users within the medical/healthcare workforce, indicate the need for knowledge and skills to consider the findings from nutrition screening and assessment and coordinate nutrition care, thereby highlighting the importance of the findings from this work in implementation.

Summary of recommendations

Nutrition educators.

Nutrition content needs to reflect the context of the workplace, with most participants indicating their preference to more clinically focused practical teaching directly relevant to their roles and signposting to resources the participants can use.

Participants preferred practical-based/short-based/skills-based education, which can be easily linked back to practice and can be easily integrated into short windows of opportunity for education.

Universal nutrition education, such as NEPHELP, may offer a short, focused baseline form on which other nutrition education can be recommended to support core as well as more specialist and potentially a more expert specialist nutrition education pathway.

Clinicians in primary and secondary care

The needs of those in primary care and secondary care were noted to be significantly different, as well as a major need to reframe the communication and transfer of nutrition care between the two settings.

There is a need for IPE or discussion across professional boundaries to support nutrition pathways. Without this, it may be difficult to address some of the identified barriers. This may pose a challenge in finding a common language so that nutrition messaging is clear and breaks through professional silos within a more multiprofessional model of care.

Postgraduate medical educators

Although nutrition is mentioned in published curriculum frameworks, examples of how nutrition might be included in education for UK Junior doctors are limited 30 and should be developed to support capacity building.

Trainee GPs wanted more in-depth nutrition education suggesting we need a variety of options and opportunities; from the minimum standards to assure patient safety, to potential career pathways for further specialisation.

To support sustainability, a PGME nutrition curriculum may assist in reaching a consensus on expectations related to nutrition and professional working roles.

PGME providers can take advantage of existing multidisciplinary nutrition educators such as the UK Nutrition Implementation Coalition. Training workshops also need to be endorsed by a professional body with relevant continued professional education credits.

Strengths and limitations

Data from multiple sources of feedback were pooled to provide deeper insights into some of the potential barriers and enablers to implementing nutrition education.

Heterogenic feedback forms and processes in each setting limited analysis. Attempts to standardise data collection on participant opinions on the utility of the nutrition workshops, as well as perceptions on nutrition roles and responsibilities in practice, were made. The NEPHELP evaluation tool was not a validated tool, which limited the usefulness of the feedback captured. To minimise facilitator pre conceptions, postworkshop discussions, alongside evaluations from participants, were used.

Another limitation was the recruitment of participants to participate in the non-mandated sessions. This was particularly evident during the Essex Roadshow event, where despite the workshop being organised at the request of the primary care providers and the enthusiasm to run this workshop outside of normal working hours at the weekend, only one participant attended. Generally, due to the nature of nutrition education and its broad application across multiple areas of practice, most health practitioners would be interested in focused nutrition content that relates to their clinical setting, specialty and region. Hence, we would imagine that if the nutrition content is clinically and regionally specific, this might stimulate greater interest and enthusiasm in nutrition education and its application in their healthcare setting.

Demographics of participants completing feedback were mainly junior doctors and general practitioners. The low response rate limits the generalisability and transferability of our findings and does not consider the views of other healthcare professionals regarding enablers and barriers to nutrition education, as well as the provision of nutrition focused care on clinical practice.

The NEPHELP project successfully delivered and adapted a bespoke nutrition education programme for doctors. However, there was no clear a ‘place’ for this training and there are significant, ongoing, barriers to delivering nutrition training in the medical postgraduate setting.

For this reason, in the UK, NNEdPro, ERimNN (Education And Research In Medical Nutrition Network), Culinary Medicine UK and Nutritank have come together to form the Nutrition Implementation Coalition (2022–23). 31 A coalition encompassing multiprofessionals who can provide a central hub of material and expertise that will support medical schools and health professionals who may lack the current faculty to develop and implement nutrition education. Also, the multiprofessional nature of the coalition can act as a role model for interprofessional working to focus on developing the seamless delivery of nutritional care. Such coalitions may be one way of developing and sustaining interest in developing nutrition expertise, by work alongside mandatory training across the range of healthcare professionals in both primary and secondary care. Finding opportunities for the delivery of clinically relevant nutrition education in ‘bitesize’ sessions may tap into the need for solution-focused education. Nutrition is central to health and disease in both prevention and treatment, this has been recently highlighted through COVID-19 and its sequelae. The interest that developed during the pandemic could provide an opportunity to translate research back into fundamental nutrition training.

Recognising there is no one ‘place’ for nutrition, the Nutrition Implementation Coalition provides a strategy to provide a ‘hub’ of material and expertise that allows the content to be available yet adapted to the needs of the providers and settings. Beyond this paper, this research has continued with the development of the online NEPHELP course via a virtual learning environment and its evaluation in primary care.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication.

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants. Participants were given information sheets about the project and how their responses may be used for research, and to inform the educational evaluation and curriculum development. UK NHS National Research Ethics Service guidance indicates that ethics review was not required. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Acknowledgments

NEPHELP Team & NNEdPro Organisational Support.

- Stratton R ,

- DiMaria-Ghalili RA ,

- Mirtallo JM ,

- Tobin BW , et al

- Desbrow B ,

- Hughes RM ,

- Leveritt MD

- Leveritt MD ,

- Desbrow B , et al

- Douglas PL ,

- McCarthy H ,

- McCotter LE , et al

- Macaninch E ,

- Buckner L ,

- Amin P , et al

- Crowley J ,

- Mansfield KJ ,

- Ray S , et al

- General Medical Council

- British Medical Association

- Health Education England

- Association for Nutrition

- Macdonald MB ,

- Ferguson LM , et al

- Abramovich N ,

- Burridge J , et al

- Stevens FCJ ,

- Aryee PA , et al

- Maudsley RF

- Douglas P , et al

EA and KM are joint first authors.

X @DrBreannaLepre, @Celia_Laur

EA and KM contributed equally.

Contributors The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: EM, KM, LB, CL, BL and SR. Data collection: WN, LB, EA, LB and EM. Analysis and interpretation of results: EA, SR and KM. Draft manuscript preparation: EA, KM and SR. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript. SR is the guarantor of this work.

Funding NEPHELP was developed as a nutrition education programme for healthcare professionals following a grant from the Medical Nutrition International award for 2017-2019, with initial periods of time spent surveying needs of future participants. 8 The project continued through further AIM foundation funding through 2021.

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Many of us can’t imagine starting the day without a cup of coffee. One reason may be that it supplies us with a jolt of caffeine, a mild stimulant to the central nervous system that quickly boosts our alertness and energy levels. [1] Of course, coffee is not the only caffeine-containing beverage. Read on to learn more about sources of caffeine, and a review of the research on this stimulant and health.

Absorption and Metabolism of Caffeine

The chemical name for the bitter white powder known as caffeine is 1,3,7 trimethylxanthine. Caffeine is absorbed within about 45 minutes after consuming, and peaks in the blood anywhere from 15 minutes to 2 hours. [2] Caffeine in beverages such as coffee, tea, and soda is quickly absorbed in the gut and dissolves in both the body’s water and fat molecules. It is able to cross into the brain. Food or food components, such as fibers, in the gut can delay how quickly caffeine in the blood peaks. Therefore, drinking your morning coffee on an empty stomach might give you a quicker energy boost than if you drank it while eating breakfast.

Caffeine is broken down mainly in the liver. It can remain in the blood anywhere from 1.5 to 9.5 hours, depending on various factors. [2] Smoking speeds up the breakdown of caffeine, whereas pregnancy and oral contraceptives can slow the breakdown. During the third trimester of pregnancy, caffeine can remain in the body for up to 15 hours. [3]

People often develop a “caffeine tolerance” when taken regularly, which can reduce its stimulant effects unless a higher amount is consumed. When suddenly stopping all caffeine, withdrawal symptoms often follow such as irritability, headache, agitation, depressed mood, and fatigue. The symptoms are strongest within a few days after stopping caffeine, but tend to subside after about one week. [3] Tapering the amount gradually may help to reduce side effects.

Sources of Caffeine

Caffeine is naturally found in the fruit, leaves, and beans of coffee , cacao, and guarana plants. It is also added to beverages and supplements. There is a risk of drinking excess amounts of caffeinated beverages like soda and energy drinks because they are taken chilled and are easy to digest quickly in large quantities.

- Coffee. 1 cup or 8 ounces of brewed coffee contains about 95 mg caffeine. The same amount of instant coffee contains about 60 mg caffeine. Decaffeinated coffee contains about 4 mg of caffeine. Learn more about coffee .

- Espresso. 1 shot or 1.5 ounces contains about 65 mg caffeine.

- Tea. 1 cup of black tea contains about 47 mg caffeine. Green tea contains about 28 mg. Decaffeinated tea contains 2 mg, and herbal tea contains none. Learn more about tea .

- Soda. A 12-ounce can of regular or diet dark cola contains about 40 mg caffeine. The same amount of Mountain Dew contains 55 mg caffeine.

- Chocolate (cacao) . 1 ounce of dark chocolate contains about 24 mg caffeine, whereas milk chocolate contains one-quarter of that amount.

- Guarana. This is a seed from a South American plant that is processed as an extract in foods, energy drinks, and energy supplements. Guarana seeds contain about four times the amount of caffeine as that found in coffee beans. [4] Some drinks containing extracts of these seeds can contain up to 125 mg caffeine per serving.

- Energy drinks. 1 cup or 8 ounces of an energy drink contains about 85 mg caffeine. However the standard energy drink serving is 16 ounces, which doubles the caffeine to 170 mg. Energy shots are much more concentrated than the drinks; a small 2 ounce shot contains about 200 mg caffeine. Learn more about energy drinks .

- Supplements. Caffeine supplements contain about 200 mg per tablet, or the amount in 2 cups of brewed coffee.

Recommended Amounts

In the U.S., adults consume an average of 135 mg of caffeine daily, or the amount in 1.5 cups of coffee (1 cup = 8 ounces). [5] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration considers 400 milligrams (about 4 cups brewed coffee) a safe amount of caffeine for healthy adults to consume daily. However, pregnant women should limit their caffeine intake to 200 mg a day (about 2 cups brewed coffee), according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

The American Academy of Pediatrics suggests that children under age 12 should not consume any food or beverages with caffeine. For adolescents 12 and older, caffeine intake should be limited to no more than 100 mg daily. This is the amount in two or three 12-ounce cans of cola soda.

Caffeine and Health

Caffeine is associated with several health conditions. People have different tolerances and responses to caffeine, partly due to genetic differences. Consuming caffeine regularly, such as drinking a cup of coffee every day, can promote caffeine tolerance in some people so that the side effects from caffeine may decrease over time. Although we tend to associate caffeine most often with coffee or tea, the research below focuses mainly on the health effects of caffeine itself. Visit our features on coffee , tea , and energy drinks for more health information related to those beverages.

Caffeine can block the effects of the hormone adenosine, which is responsible for deep sleep . Caffeine binds to adenosine receptors in the brain, which not only lowers adenosine levels but also increases or decreases other hormones that affect sleep, including dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine, and GABA. [2] Levels of melatonin, another hormone promoting sleep, can drop in the presence of caffeine as both are metabolized in the liver. Caffeine intake later in the day close to bedtime can interfere with good sleep quality. Although developing a caffeine tolerance by taking caffeine regularly over time may lower its disruptive effects, [1] those who have trouble sleeping may consider minimizing caffeine intake later in the day and before going to bed.

In sensitive individuals, caffeine can increase anxiety at doses of 400 mg or more a day (about 4 cups of brewed coffee). High amounts of caffeine may cause nervousness and speed up heart rate, symptoms that are also felt during an anxiety attack. Those who have an underlying anxiety or panic disorder are especially at risk of overstimulation when overloading on caffeine.

Caffeine stimulates the heart, increases blood flow, and increases blood pressure temporarily, particularly in people who do not usually consume caffeine. However, strong negative effects of caffeine on blood pressure have not been found in clinical trials, even in people with hypertension, and cohort studies have not found that coffee drinking is associated with a higher risk of hypertension. Studies also do not show an association of caffeine intake and atrial fibrillation (abnormal heart beat), heart disease , or stroke. [3]

Caffeine is often added to weight loss supplements to help “burn calories.” There is no evidence that caffeine causes significant weight loss. It may help to boost energy if one is feeling fatigued from restricting caloric intake, and may reduce appetite temporarily. Caffeine stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, which plays a role in suppressing hunger, enhancing satiety, and increasing the breakdown of fat cells to be used for energy. [6] Cohort studies following large groups of people suggest that a higher caffeine intake is associated with slightly lower rates of weight gain in the long term. [3] However, a fairly large amount of caffeine (equivalent to 6 cups of coffee a day) may be needed to achieve a modest increase in calorie “burn.” Additional calories obtained from cream, milk, or sweetener added to a caffeinated beverage like coffee or tea can easily negate any calorie deficit caused by caffeine.

Caffeine can cross the placenta, and both mother and fetus metabolize caffeine slowly. A high intake of caffeine by the mother can lead to prolonged high caffeine blood levels in the fetus. Reduced blood flow and oxygen levels may result, increasing the risk of miscarriage and low birth weight. [3] However, lower intakes of caffeine have not been found harmful during pregnancy when limiting intakes to no more than 200 mg a day. A review of controlled clinical studies found that caffeine intake, whether low, medium, or high doses, did not appear to increase the risk of infertility. [7]

Most studies on liver disease and caffeine have specifically examined coffee intake. Caffeinated coffee intake is associated with a lower risk of liver cancer, fibrosis, and cirrhosis. Caffeine may prevent the fibrosis (scarring) of liver tissue by blocking adenosine, which is responsible for the production of collagen that is used to build scar tissue. [3]

Studies have shown that higher coffee consumption is associated with a lower risk of gallstones. [8] Decaffeinated coffee does not show as strong a connection as caffeinated coffee. Therefore, it is likely that caffeine contributes significantly to this protective effect. The gallbladder is an organ that produces bile to help break down fats; consuming a very high fat diet requires more bile, which can strain the gallbladder and increase the risk of gallstones. It is believed that caffeine may help to stimulate contractions in the gallbladder and increase the secretion of cholecystokinin, a hormone that speeds the digestion of fats.

Caffeine may protect against Parkinson’s disease. Animal studies show a protective effect of caffeine from deterioration in the brain. [3] Prospective cohort studies show a strong association of people with higher caffeine intakes and a lower risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. [9]

Caffeine has a similar action to the medication theophylline, which is sometimes prescribed to treat asthma. They both relax the smooth muscles of the lungs and open up bronchial tubes, which can improve breathing. The optimal amount of caffeine needs more study, but the trials reviewed revealed that even a lower caffeine dose of 5 mg/kg of body weight showed benefit over a placebo. [10] Caffeine has also been used to treat breathing difficulties in premature infants. [3]

Caffeine stimulates the release of a stress hormone called epinephrine, which causes liver and muscle tissue to release its stored glucose into the bloodstream, temporarily raising blood glucose levels. However, regular caffeine intake is not associated with an increased risk of diabetes . In fact, cohort studies show that regular coffee intake is associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes , though the effect may be from the coffee plant compounds rather than caffeine itself, as decaffeinated coffee shows a similar protective effect. [3] Other observational studies suggest that caffeine may protect and preserve the function of beta cells in the pancreas, which are responsible for secreting insulin. [11]

Signs of Toxicity

Caffeine toxicity has been observed with intakes of 1.2 grams or more in one dose. Consuming 10-14 grams at one time is believed to be fatal. Caffeine intake up to 10 grams has caused convulsions and vomiting, but recovery is possible in about 6 hours. Side effects at lower doses of 1 gram include restlessness, irritability, nervousness, vomiting, rapid heart rate, and tremors.

Toxicity is generally not seen when drinking caffeinated beverages because a very large amount would need to be taken within a few hours to reach a toxic level (10 gm of caffeine is equal to about 100 cups of brewed coffee). Dangerous blood levels are more often seen with overuse of caffeine pills or tablets. [3]

Did You Know?

- Caffeine is not just found in food and beverages but in various medications. It is often added to analgesics (pain relievers) to provide faster and more effective relief from pain and headaches. Headache or migraine pain is accompanied by enlarged inflamed blood vessels; caffeine has the opposite effect of reducing inflammation and narrowing blood vessels, which may relieve the pain.

- Caffeine can interact with various medications. It can cause your body to break down a medication too quickly so that it loses its effectiveness. It can cause a dangerously fast heart beat and high blood pressure if taken with other stimulant medications. Sometimes a medication can slow the metabolism of caffeine in the body, which may increase the risk of jitteriness and irritability, especially if one tends to drink several caffeinated drinks throughout the day. If you drink caffeinated beverages daily, talk with your doctor about potential interactions when starting a new medication.

Energy Drinks

- Clark I, Landolt HP. Coffee, caffeine, and sleep: A systematic review of epidemiological studies and randomized controlled trials. Sleep medicine reviews . 2017 Feb 1;31:70-8. *Disclosure: some of HPL’s research has been supported by Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Military Nutrition Research. Caffeine for the Sustainment of Mental Task Performance: Formulations for Military Operations. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. 2, Pharmacology of Caffeine. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK223808/

- van Dam RM, Hu FB, Willett WC. Coffee, Caffeine, and Health. NEJM . 2020 Jul 23; 383:369-378

- Moustakas D, Mezzio M, Rodriguez BR, Constable MA, Mulligan ME, Voura EB. Guarana provides additional stimulation over caffeine alone in the planarian model. PLoS One . 2015 Apr 16;10(4):e0123310.

- Drewnowski A, Rehm CD. Sources of caffeine in diets of US children and adults: trends by beverage type and purchase location. Nutrients . 2016 Mar;8(3):154.

- Harpaz E, Tamir S, Weinstein A, Weinstein Y. The effect of caffeine on energy balance. Journal of basic and clinical physiology and pharmacolog y. 2017 Jan 1;28(1):1-0.

- Bu FL, Feng X, Yang XY, Ren J, Cao HJ. Relationship between caffeine intake and infertility: a systematic review of controlled clinical studies. BMC Womens Health . 2020;20(1):125.

- Zhang YP, Li WQ, Sun YL, Zhu RT, Wang WJ. Systematic review with meta‐analysis: coffee consumption and the risk of gallstone disease. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics . 2015 Sep;42(6):637-48.

- Hong CT, Chan L, Bai CH. The Effect of Caffeine on the Risk and Progression of Parkinson’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. Nutrients . 2020 Jun;12(6):1860.

- Welsh EJ, Bara A, Barley E, Cates CJ. Caffeine for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2010;2010(1):CD001112.

- Lee S, Min JY, Min KB. Caffeine and Caffeine Metabolites in Relation to Insulin Resistance and Beta Cell Function in US Adults. Nutrients . 2020 Jun;12(6):1783.

Last reviewed July 2020

Terms of Use

The contents of this website are for educational purposes and are not intended to offer personal medical advice. You should seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. Never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this website. The Nutrition Source does not recommend or endorse any products.

We've been independently researching and testing products for over 120 years. If you buy through our links, we may earn a commission. Learn more about our review process.

The Best Bath Towels, According to Testing

We spent six years evaluating more than 90 bath towels in our Textiles Lab.

Finding the best bath towel is largely based on personal preference, but one thing we can agree on is that it should be absorbent to dry you off, comfortable against your skin and long-lasting to stand up to repeated use and laundering. It also doesn't hurt to have one that dries quickly after it gets wet.

- Best Overall: Frontgate Resort Collection Bath Towel

- Best Value : Amazon Basics Quick-Dry Bath Towel, Set of 2

- Best Quick-Dry: Everplush Diamond Jacquard Bath Towel

- Best Lightweight: Pottery Barn Hydrocotton Quick-Dry Towel

- Best Heavyweight: Brooklinen Super Plush Bath Towel, 2-Pack

- Softest: Riley Plush Bath Towel

- Most Absorbent: RH Ultra Soft Turkish Bath Towel

- Best Luxury: Matouk Milagro Bath Towel

Frontgate Resort Collection Bath Towels

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 3/5 | Softness: 4.3/5 | Durability: 4.2/5

Frontgate's towel uses a simple, high-quality construction that outperformed most other towels in our review. Part of that is thanks to its material, including long-staple Turkish cotton fibers (which are smoother and more durable than traditional cotton). As an added bonus, it comes in 25 colors so there's something for every preference.

At-home users praised the towel's softness and said it looked great after repeated use. One described it as having "a classic, plush feel and a substantial hand," while adding, "These have stayed soft after months of use thus far." Users also highlighted the appearance and one called it "a perfect size to wrap around my body." Just note that although at-home testers unanimously gave it perfect scores for softness, it didn't earn quite as high softness ratings in our comparison tests when consumers felt it alongside other towels.

When it came to our Textiles Lab evaluations, this one earned perfect scores in our absorbency tests. It's not quick-drying and only had a moderate dry speed in our tests, and though it had some shrinkage in the wash, it was overall durable with strong fabric that didn't show signs of wear after laundering.

Material: 100% cotton | Weight: 700 GSM | Colors: 26 options | Dimensions: 30" x 58" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

Amazon Basics Quick-Dry Bath Towels, 2-Pack

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 3.5 /5 | Drying speed: 3.5/5 | Softness: 4/5 | Durability: 3.8/5

If you're looking to save or prefer to buy towels on Amazon , this one had an standout performance and costs just $10 per towel. It feels lightweight — it's thinner and less dense than other towels — yet is still super soft. I've been using this one at home to get a sense of how it compares to the others we recommend and have been impressed that it feels more expensive than it actually is.

Not all testers loved its lightweight feel, especially those that prefer the heftier weight of a luxe towel. However, users said it feels soft and absorbent during real use after showers. It was somewhat absorbent in Lab tests, though it didn't soak up fluid as easily as other options and had some shrinkage after laundering. Still, its performance for the price can't be beat.

Material: 100% cotton | Weight: Not listed | Colors: 4 options | Dimensions: 30" x 54" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

Everplush Diamond Jacquard Bath Towel

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 5/5 | Softness: 4.4/5 | Durability: 4.1/5

This quick-dry towel is my personal favorite thanks to its unique construction. I especially love how it has cotton on the outside for softness, but microfiber on the inside for enhanced performance. The result makes it an excellent balance of absorbent, quick-drying, strong and shrink-resistant. Testers also noted that they liked the texture, which looks different than typical cotton loops.

One thing to note is that the fabric surface showed fuzzy signs of wear more quickly than other towels in our laundering evaluations. Still, it was a top performer and the only towel to ace both absorbency and drying time tests. We're also fans of the brand's Hokime Ribbed Towels for those who prefer even more of a textured feel as these were also top performers in our tests.

READ OUR FULL REVIEW: The Everplush Diamond Jacquard is the Only Bath Towel I Need

Material: 48% polyester, 40% cotton, 12% polyamide | Weight: Not listed | Colors: 9 options | Dimensions: 30" x 56" inches | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

Pottery Barn Hydrocotton Quick-Dry Towel

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 3.5/5 | Softness: 4.7/5 | Durability: 4/5

If you prefer a luxurious towel that's not too heavy , this one is your best bet. It's made of Turkish cotton that's certified organic by the Global Organic Textile Standard (GOTS), plus it stood out in our tests for being super soft and ultra-absorbent. In fact, it earned perfect absorbency ratings in our evaluations, soaking up all fluid without any liquid running off. Our testers unanimously gave it high scores, referring to it as "comfy," "so fluffy" and the "ideal towel." I tried it at home and agree: It has stayed soft despite repeated use and feels lighter than other absorbent towels I've tried.

Beyond that, it held up well to our laundering tests — the fabric looked and felt good (despite some shrinkage) even after 20 wash cycles. Just note that although the name claims these towels are quick-dry, they actually took longer to fully dry than other bath towels in our test.

Material: 100% organic Turkish cotton | Weight: 550 GSM | Colors: 14 options | Dimensions: 28" x 50" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

Brooklinen Super-Plush Bath Towels, 2-Pack

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 3/5 | Softness: 4.8/5 | Durability: 3.9 /5

This style is ideal for anyone who prefers the comfort of a soft, dense towel: Its cotton fabric has the heaviest weight of all our picks at a whopping 820 GSM. This helped it achieve excellent absorbency in Lab evaluations and superior softness ratings in our consumer tester reviews. One tester noted, "It is a very thick towel that absorbs the water off your body practically in one pass," while another proclaimed, "It's the best towel I've ever used." I've personally used this one at home and can attest to its thick and absorbent construction.

Another highlight is that it didn't shed lint in the wash, which is a common concern with plush towels. It did have some shrinkage after laundering and it wasn't quick-drying, but both of these areas still scored average compared to other towels in our test. On top of that, this one is backed by our Good Housekeeping Seal , which means we stand behind it with our limited warranty.

Material: 100% Turkish cotton | Weight: 820 GSM | Colors: 11 options, with additional seasonal colors | Dimensions: 30" x 58" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet, bath mat

Riley Home Plush Bath Towel

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 4/5 | Softness: 5/5 | Durability: 4.1 /5

Riley's towel uses a zero-twist combed cotton construction, meaning the fibers are longer and stronger so it's softer, more absorbent and more durable. At-home users unanimously gave it perfect scores for softness and raved about its luxurious feel. In fact, one tester said, "It was the softest towel I've ever used," while another told us, "I expected the softness to disappear with washing, but it stayed soft. And the fluffiness didn't decrease with washing either."

In addition to the exceptional reviews from consumer testers, our analysts were amazed by how soft it remained after repeated laundering cycles in our standardized tests, though it did have some shrinkage. It also earned perfect absorbency scores in the Lab and dried fairly quickly, which is impressive for a plush, 100% cotton towel. Just note that at times we've seen inventory issues with this style with certain colors and sizes sold out online. We also recently tested Riley's Spa Towel Collection , which is more of a low-pile towel (i.e. not as plush or dense) and was well-loved by testers.

Material: 100% cotton | Weight: 650 GSM | Colors: 6 options | Dimensions: 30" x 58" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

RH Ultra-Soft Turkish Bath Towel

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 2/5 | Softness: 4.9/5 | Durability: 3.8/5

This 100% cotton towel was by far the most absorbent in our tests, quickly soaking up all fluid without any runoff. Plus, our panel praised the fluffiness and rated it softer than dozens of others in a blind comparison. They specifically liked the heavy, blanket-like feel and described it as super plush.

On the flip side, these towels took a while to dry, which is not surprising with such high absorbency. It also shrunk a bit in our wash tests. Still, if you want to wrap yourself in a thick, cozy towel that dries you off quickly, this is the one for you.

Material: 100% cotton | Weight: 750 GSM | Colors: 15 options | Dimensions: 30" x 56" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet

Matouk Milagro Bath Towel

LAB RESULTS: Absorbency: 5/5 | Drying speed: 4/5 | Softness: 4.9/5 | Durability: 4.6/5

Though it's certainly not for everyone, this one's a great choice for anyone who's looking for the most luxurious option that's worth the splurge . The towel size is longer than average at 60 inches, plus it's soft, fluffy and fairly lightweight. The brand says it uses a long-staple cotton and zero-twist construction, which helps the towel become softer and more absorbent.

A tester described this towel as feeling like a "soft, fluffy cloud" and added, "I liked drying my hair with it (it felt less harsh)." It was super absorbent in Lab tests, yet didn't take too long to dry compared to other absorbent styles. It did have notable shrinkage in laundering tests, but the appearance looked like new after repeated washing.

Material: 100% cotton | Weight: 550 GSM | Colors: 17 options | Dimensions: 30" x 60" | Matching pieces: Washcloth, hand towel, bath sheet, bath mat, fingertip towel

More types of bath towels to consider

Our tests show that the traditional bath towel style made with cotton terry loops performs best in terms of absorbency, softness and overall tester satisfaction. That being said, there are some novel types of towels that have been gaining popularity for their unique attributes. Here are some that we tested and recommend if you're looking for something new:

- Best Waffle Towel: The Parachute Waffle Towel is super lightweight at 220 GSM and dried quickly in our tests. The downside is that it wasn't as absorbent as traditional towels, which is true for every waffle towel we've tested. We also recently tested the popular Onsen Waffle Weave Bath Towel . It stood out for its durability, but didn't earn high scores in our absorbency, drying speed or softness tests.

- Best Organic Towel: Not only is the Coyuchi Temescal Organic Towel certified by GOTS (so you know the entire production process follows strict standards), but it was also one of the top performers in our softness and absorbency tests, proving that you don't need to sacrifice towel quality by shopping more sustainability. The downside is that this one is extremely pricey.

- Best Linen Towel: Linen towels are not common, but they stand out for having a crisp, textured feel. We recently tested the Linoto Linen Spa Bath Towel , which was overall durable and well-liked by at-home testers. However, it wasn't rated as soft as cotton bath towels in comparison tests and didn't soak up water easily in our absorbency tests.

- Best Hybrid Towel: Boll & Branch's Waffle Terry Bath Towel has a unique construction with a traditional terry fabric on one side and a waffle fabric on the other. It was fairly absorbent with an average drying speed, and at-home testers unanimously loved using it.

How we test bath towels

My team of product analysts and I have tested more than 90 bath towels in the past six years. Each one is put through the wringer in both Lab tests and consumer evaluations. Here's how the bath towels are scored:

✔️ Absorbency: Using the apparatus pictured here, we set up a towel sample at a 60-degree angle and pour water onto it from a standard distance. Any water that the towel doesn't absorb rolls off the fabric and into the container below, which we weigh to measure much runs off. This test is performed multiple times on each towel, including after repeated wash cycles because absorbency can change after extended use. A towel with perfect absorbency doesn't have any runoff.

✔️ Drying speed : We apply a standard amount of water to a towel swatch then hang it to dry. We reweigh the swatch every 30 minutes until it reaches its original weight, indicating that the towel has fully dried.

✔️ Washability: Our analysts wash and dry each towel 20 times, measuring shrinkage and appearance throughout this process. We also measure weight loss from laundering to see how much each towel sheds lint.

✔️ Fabric strength: A specialized machine called the Instron pulls swatches of towel fabric apart and measures the force needed to break each one.

✔️ Consumer tests: Dozens of consumer testers use the towels at home and rate them on factors like softness, appearance, whether they were dried off quickly and more. We also set up blinded softness tests in our Lab, where additional consumers feel and rate each one in a side-by-side comparison.

How to choose the right bath towel for you

One thing we've learned from extensive consumer testing is that picking out the best bath towel is largely based on personal preference. Here's what you should consider:

- If you want a super soft, ultra-absorbent towel, look for 100% cotton with dense, plush loops on the surface. You can also look at fabric weight, which is shown in GSM (grams per square meter). Over 600 GSM is considered heavy, so these will typically be the plushest. Lighter towels like waffle weaves or ribs typically weren't as soft in our test.

- If you want a towel that's quick-drying and more durable, consider a cotton-poly blend or a lighter fabric with a low pile (short loops). Fluffy loops help the towel feel soft and absorb water, but they can take longer to dry and may show more wear from laundering.

Is Egyptian or Turkish cotton better for towels?

It’s not a rule of thumb, but towels labeled as “Turkish cotton” or “Made in Turkey” performed better in our tests than those claiming to be made of “Egyptian” cotton. In theory, they’re very similar: Both are long-staple fibers, helping to make the fabrics softer and more durable. However, Turkish cotton is more popular in bath towels and is known for drying faster than Egyptian cotton, which is more commonly seen in bed sheets. Plus, there have been instances of bedding fabrics mislabeled as Egyptian cotton, especially because it's difficult to verify this claim.

How do you stop towels from shedding fluff?

My best tip is to wash them before use. Sometimes there are loose fibers leftover from the production process, but laundering the towels a few times should help get rid of them. Not to mention, washing them also makes the towels more absorbent because it gets rid of leftover finishes from production.

Why trust Good Housekeeping?

Lexie Sachs is the executive director of strategy & operations at the Good Housekeeping Institute , where she has been researching, testing and writing about bath towels for over a decade. Lexie has developed proprietary evaluations while also following standardized industry test methods to review dozens of styles both in the Textiles Lab and in the homes of consumer testers.

Testing for this article has also been conducted by senior textiles analyst Emma Seymour , textiles product reviews analyst Grace Wu and contributing analyst Rachael Chen .

Lexie Sachs (she/her) is the executive director of strategy and operations at the Good Housekeeping Institute and a lead reviewer of products in the bedding, travel, lifestyle, home furnishings and apparel spaces. She has over 15 years of experience in the consumer products industry and a degree in fiber science from Cornell University. Lexie serves as an expert source both within Good Housekeeping and other media outlets, regularly appearing on national broadcast TV segments. Prior to joining GH in 2013, Lexie worked in merchandising and product development in the fashion and home industries.

Grace Wu (she/her) is a product reviews analyst at the Good Housekeeping Institute 's Textiles, Paper and Apparel Lab, where she evaluates fabric-based products using specialized equipment and consumer tester data. Prior to starting at Good Housekeeping in 2022, she earned a master of engineering in materials science and engineering and a bachelor of science in fiber science from Cornell University. While earning her degrees, Grace worked in research laboratories for smart textiles and nanotechnology and held internships at Open Style Lab and Rent the Runway.

Emma Seymour (she/her) is a senior product analyst at the Good Housekeeping Institute 's Textiles, Paper and Apparel Lab, where she has led testing for luggage, pillows, towels, tampons and more since 2018. She graduated from Cornell University with a bachelor of science in fiber science and apparel design and a minor in gerontology, completing research in the Body Scanner Lab on optimizing activewear for athletic performance.

@media(max-width: 64rem){.css-o9j0dn:before{margin-bottom:0.5rem;margin-right:0.625rem;color:#ffffff;width:1.25rem;bottom:-0.2rem;height:1.25rem;content:'_';display:inline-block;position:relative;line-height:1;background-repeat:no-repeat;}.loaded .css-o9j0dn:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/goodhousekeeping/static/images/Clover.5c7a1a0.svg);}}@media(min-width: 48rem){.loaded .css-o9j0dn:before{background-image:url(/_assets/design-tokens/goodhousekeeping/static/images/Clover.5c7a1a0.svg);}} Around the Bathroom

The Best Bath Towels on Amazon

14 Designer-Approved Bathroom Looks

The Best Toilets

The Best Toilet Bowl Cleaners

The Best Shower Filters

The Best Bathroom Cleaners

The Best Bathroom Scales, Tested & Reviewed

The Best Shower Cleaners

The Best Degreasers

The Best Eco-Friendly Household Cleaners

14 Over-the-Toilet Storage Ideas to Stay Organized

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.361; 2018

Science and Politics of Nutrition

Dietary carbohydrates: role of quality and quantity in chronic disease, david s ludwig.

1 New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, USA

2 Department of Pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

3 Department of Nutrition, Harvard T H Chan School of Public Health, Boston, USA

4 Channing Division of Network Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston

5 Department of Physiology, University of Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland.

Jennie Brand-Miller

6 Charles Perkins Centre, School of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia

David S Ludwig and colleagues examine the links between different types of carbohydrates and health

Carbohydrate is the only macronutrient with no established minimum requirement. Although many populations have thrived with carbohydrate as their main source of energy, others have done so with few if any carbohydrate containing foods throughout much of the year (eg, traditional diets of the Inuit, Laplanders, and some Native Americans). 1 2 If carbohydrate is not necessary for survival, it raises questions about the amount and type of this macronutrient needed for optimal health, longevity, and sustainability. This review focuses on these current controversies, with special focus on obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and early death.

Role of carbohydrate consumption in human development