ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, tips for writing an effective teaching and research statement.

A compelling teaching and research statement can make the difference between getting the academic job desired and having the profile ignored with dozens of other job seekers. One may not actually be asked to present a teaching statement during the job application process, but the action of writing one will help to clarify one’s goals and how to talk about them. If asked for a statement of teaching and research, then it will be a useful resource to have completed.

Writing a teaching and research statement

Take the time to write your statement correctly, for it is not something that can come “off the top of your head.” Teaching and research statements are a summary of work and teaching philosophy, both of which can be very complicated statements.

The research statement discusses a person’s work in a way that helps people understand one’s interests and focus in his or her work. It should address several points clearly and concisely:

- What impact has it had or is expected to have?

- How does it line up (if it does) with other work being done in the field?

- What changes might there be in a person’s life as a result of this work?

- How might someone be challenged to make use of this work?

- What additional questions have come up as a result of the work?

- What is the timeline and what resources are required to make this happen?

The research statement could be several pages, but be prepared to create a one to two-page summary that can be presented on demand. One can speak with the facility to which they are applying and get an idea of the length and format of the research statement they wish to see.

The teaching statement presents one’s philosophy on teaching. This should not only talk about the techniques used, but the motivation behind choosing those particular methods. Some of the points that a teaching statement might cover are:

- What are one’s goals for teaching and the reasoning behind the particular methods used?

- How have they been adapted to one’s own style?

- How effective are these techniques compared to other techniques in the field?

- How has one’s implementation of a particular tool been influenced by his or her teaching style?

- How does one’s method of teaching take into account the various ways in which people learn?

The teaching statement should communicate a person’s vision for teaching and describe how and why the methods selected improve the teaching experience for people. This is a presentation of how the teaching methods of one person have influenced the teaching profession.

Both the teaching and research statements are created for the employer to determine what kind of teacher or researcher a person is and how he or she will fit into the organization. Especially in the academic role, one must be able to work within the policies of the institution and with the various philosophies of his or her co-workers. Tenure often depends on this.

When creating these statements, there are some guidelines applicable to both:

Focus on the how, not the what

This is not a laundry list of the research work or teaching that’s been done. It may be helpful to present a short list of topics to emphasize the focus or diversity. But the real purpose of these statements is to discuss why those classes were taught, or why that piece of research was done.

Back up statements with evidence

There is often the tendency to make positive, but very open-ended statements in teaching and research statements and CVs. Those get glossed over unless there is a statement of proof accompanying them. One might say “I create a safe learning environment for students,” but the real question is how is this done? Make sure to reword those statements as “I create a safe learning environment for students by…” which covers the obvious question.

Create good writing examples

These statements will give some insight into how well a person can write. They should serve not only as the tool for communicating teaching philosophy and work accomplishments, but as a piece of writing that demonstrates how one communicates through the written word. Do not ignore spelling and grammar checking. Even when making simple revisions, recheck spelling and grammar when done.

Express confidence, not omniscience

Do not let these statements sound as if one knows all there is to know about teaching and research. The tone should not present that mistakes never happened. It is more useful to talk about successes mixed in with some failures and how one learned from those times. Show how one continues to become a better professional by learning from mistakes.

Keep the focus external

These statements should express how the teaching and research efforts were done for the benefit of the students or other researchers. A tone of humility is preferred over a selfish one. This helps to emphasize the motivation for which these tasks were done. Both of these statements give insight into what drives the person and helps the employer see how he or she will work with the existing staff and in the organization.

You may also like to read

- 4 Tips for Teaching 2nd Grade Writing

- Five Tips for Team Teaching

- Effective Teaching Strategies for Special Education

- Effective Teaching Strategies for Adolescent Literacy Teachers

- Web Research Skills: Teaching Your Students the Fundamentals

- Five Tips for Teaching English to Non-Native Speakers

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Job Prospects , Postsecondary (Advanced Education)

- Certificates Programs in Education

- Certificates for Reading Specialist

- Master's in Social Studies Education & Teachi...

Teaching Statements

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write a teaching statement, a 1-4 page document that describes your teaching experiences and pedagogical approaches.The first time you write a teaching statement is often in the context of an application for an academic job or teaching position.

What is a teaching statement?

A teaching statement, or statement of teaching philosophy, highlights academic job candidates’ teaching qualifications, explains their pedagogical approaches, and demonstrates how they will contribute to the teaching culture of prospective institutions.

Because hiring committees for academic jobs cannot observe the teaching of every applicant, they rely on other means of evaluating a candidate’s teaching. These alternatives may include a teaching demonstration during a campus visit; a teaching portfolio consisting of student evaluations, sample syllabi, etc; and/or a teaching statement. By illustrating a candidate’s teaching experiences and philosophy with concrete examples, a teaching statement helps the hiring committee imagine what it would be like inside the candidate’s classroom.

Teaching statements will vary from candidate to candidate (and one candidate’s teaching statements may vary from application to application). The sections below offer guidelines to help you prepare, write, and revise your own teaching statement.

Preparing to write a teaching statement

An effective teaching statement involves both reflection and research. Thinking about your teaching and your goals can be helpful before you begin writing or revising your teaching statement. This process can also prepare you for interview questions that address teaching, should your application lead to an interview.

Brainstorming

Before you begin writing your teaching statement, it can be useful to think more generally about your teaching philosophy. Once you’ve brainstormed some ideas, you can then focus on how to clearly and succinctly communicate those thoughts in a teaching statement. For some general brainstorming strategies, you can consult our Brainstorming handout; the following questions will help you brainstorm more specifically about your teaching philosophy:

- What goals do you set for students in your courses?

- How do you enact those goals?

- How do you evaluate how well those goals are being met?

- What is your plan for developing your teaching? What other aspects of pedagogy would you like to develop in your practice?

- What can a student expect to experience in your class?

- What is the relationship between your teaching and research?

- What are the unique challenges or opportunities to teaching in your field?

- What is your favorite aspect of teaching? Why?

- What is your favorite course to teach? Why?

- How do you effectively teach students with diverse identities and backgrounds?

- How do your beliefs about student learning affect your instructional choices?

Consulting models

Looking at sample teaching statements can give you a better sense of the genre and can help you determine what elements you would like to include in your own teaching statement. Students in your program, recent graduates, and professors may be willing to share models, and many examples are also available online through libraries and faculty resource centers.

As you look at sample teaching statements, think about what you do or do not like about each statement. The following questions can help you determine how you might construct your own statement.

- What is the most memorable part of the teaching statement? Why?

- How is the teaching statement organized (e.g. thematically, chronologically)?

- How easily are you able to follow the structure of the statement?

- What is the writing style of the teaching statement (e.g. formal, conversational)?

- What impression of the writer does the writing style convey?

- What image of the writer are you left with after reading the entire statement?

- How well can you imagine yourself as a student in the writer’s class?

Researching the institution

Different institutions will have different teaching cultures and, therefore, will value different types of teaching statements. For example, a research university and a community college may have different approaches to teaching, so the same teaching statement is unlikely to appeal to both institutions. Instead, you should try to tailor your teaching statement to each individual institution (and department) to which you are applying.

As a first step, you can explore the institution and department websites to learn how much emphasis they place on teaching. You might also research the department faculty, their areas of expertise, and the courses they have recently taught. By learning about your audience, their teaching expectations, and their values, you can tailor your teaching statement to demonstrate how well you will fit into the department’s teaching culture.

You might also think about the department’s needs by considering current offerings and what they can tell you about the priorities and values of the department. Without making assumptions, you can ask yourself:

- How do the department’s offerings compare with common or standard course offerings in the field? How do they compare with courses you have taken or taught?

- How does your current research relate to the department’s course offerings?

- Which courses would you be prepared to teach?

- What future courses might you envision creating for the department?

- Does the department offer any special courses, seminars, or initiatives relevant to your research or teaching experience?

Although a targeted teaching statement is important at any point in the application process, the timing of the hiring committee’s request can also inform you about how targeted the statement should be. For example, if the committee requests a teaching statement after they have already reviewed your initial materials, then you should be even more purposeful in demonstrating how you will fit into their specific teaching culture and how you can contribute to their department’s teaching needs.

Drafting a teaching statement

Because teaching statements are variable in design and structure, you will have many choices to make during the drafting process. Here are some common decision points, considerations, and challenges to keep in mind while writing your teaching statement.

Organizational strategies

Teaching statements do not have one set organizational structure. Instead, you can employ different organizational strategies to emphasize different aspects of your teaching. Here are a few examples that you could consider:

Think of your teaching history as a narrative (past, present, future). How have your previous experiences informed your current practices? How might those practices transform within different contexts in the future? This narrative strategy allows you to build upon past experiences to point towards future development.

Structure your statement around your teaching goals, methods, and assessment. How do your goals inform your methods, and how do you assess the extent to which those goals have been reached? This process-oriented strategy can help you highlight connections between goals and outcomes and show how those connections inform your practice.

Identify themes, concepts, ways of thinking, or learning strategies that are prevalent in your teaching. How do these elements help students learn? This approach can characterize what’s distinctive about your teaching and how it serves students.

Be specific and concrete

Including specific details and explanations in your teaching statement will help the audience picture what it’s like to be in your classroom. Rather than simply mentioning a particular innovation or strategy, include examples of how it has helped students in practice.

Explain terms that could be open to interpretation by your reader. For example, if you mention the importance of critical thinking in your teaching statement, explain what that means to you as an instructor.

Use concrete examples from your teaching and classroom experiences to illustrate how your teaching philosophy informs your practice. How does your philosophy shape your students’ experiences in the classroom?

Incorporate inclusivity

While some applications will also require a diversity statement, the teaching statement is your opportunity to express how you consider diversity and foster inclusivity in the classroom through specific examples. Incorporating inclusivity throughout your teaching statement demonstrates that it is an integral part of your philosophy and practice rather than just a required element tacked on at the end. Here are some questions to help you reflect on how you might incorporate inclusivity in your teaching:

- How does your course material reflect contributions from diverse perspectives?

- How do you encourage collaboration among all students?

- How do you help students from diverse backgrounds feel welcome and safe in your classroom?

- How do you cultivate an inclusive learning environment that encourages students to think about the effects of racial, cultural, gender, socioeconomic, and other differences?

- How do you make your instruction accessible to students with physical disabilities and learning differences?

How do I keep my teaching statement both professional and personal?

As with most writing, knowledge of your intended audience can help guide choices around style. You can use the information you gleaned from researching the institution to develop a sense of their values and level of formality. You might also consider models, especially those from applicants at comparable career stages or applying to comparable institutions, and assess the type of language and tone used.

Especially if you are writing a statement as part of an application, your teaching statement should be unique to you. See our handout on Application Essays for more general advice on writing in application contexts.

What if I’m not an experienced teacher?

Although having extensive teaching experience may help you to draw examples for your teaching statement, prior teaching experience is not required to write a quality teaching statement. In some fields, opportunities to teach are few and far between; committees will be understanding of this, especially at institutions where research is prioritized. Regardless of whether you have much teaching experience, be sure to frame yourself as a teacher rather than a student.

Here are some strategies to help you draft a teaching statement, even if you aren’t an experienced teacher:

- If you haven’t taught your own courses, draw upon experiences when you served as a teaching assistant for another instructor.

- If you don’t have any experience teaching in a classroom, think of other transferable experiences like tutoring, coaching, or mentoring that illustrate what you would be like as a teacher.

- If you have time, seek out teaching-related opportunities, such as giving guest lectures or mentoring junior colleagues.

- If you really have no teaching experience, imagine and describe what you will be like as a teacher, propose courses that you could teach, and provide concrete techniques that you will employ in the classroom.

How do I unify diverse teaching experiences?

Having extensive teaching experience may seem like the optimal situation for writing a teaching statement, but teaching experiences that span a broad range of courses or positions may feel disjointed or difficult to connect in a single teaching statement. In these cases, remember that you can use the diversity of your experiences to highlight your strengths and the approaches that you implement in the classroom. Here are some strategies that can help you identify commonalities across your disparate teaching experiences and construct a cohesive narrative:

- Use a strategy like webbing to help you draw connections between the ideas, theories, and/or practices from your various teaching experiences. For more information about this strategy, see our Webbing video.

- Highlight the flexibility of your teaching and explain how your unique combination of skills can contribute to your success in different teaching contexts.

- Focus your teaching statement on the skills and experiences that are most transferable to your targeted position.

Remember that you don’t need to include every teaching experience in your teaching statement. Your CV will cover all of the courses that you have taught, so your teaching statement can be an opportunity to focus on specific experiences in more detail.

Revising a teaching statement

An effective teaching statement is often the product of a series of revisions. Once you have written a draft, the strategies below can help you look for opportunities to strengthen your statement for specific application contexts and audiences.

Review your application holistically

Consider how your teaching statement fits into your application as a whole. Your teaching statement should complement your other application materials without being redundant. For example, your CV likely lists the courses you have taught; your teaching statement should not repeat the list but may highlight certain courses. Similarly, whereas a research statement will go into detail about your scholarship, your teaching statement can be a place to explain how your research and teaching inform each other. Think about how your entire application paints a cohesive picture of you as an applicant, and determine whether any elements are missing and where they could be included.

Seeking feedback

After you have developed a draft of your teaching statement, seek feedback from multiple sources. Professors, especially those who have served on hiring committees, can provide informed suggestions about the genre, but other helpful readers include fellow students, roommates, partners, family members, and coaches at the Writing Center. Asking these readers for feedback about your entire application can help you identify redundancies or gaps that you could address. See our Getting Feedback handout for advice on how to ask for effective feedback.

Editing and proofreading

Like all application materials, your teaching statement should be free of mechanical errors. Be sure to edit and proofread thoroughly. See our Editing and Proofreading handout or Proofreading video for some strategies.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Meizlish, Deborah, and Matthew Kaplan. 2008. “Valuing and Evaluating Teaching in Academic Hiring: A Multidisciplinary, Cross-Institutional Study.” The Journal of Higher Education 79 (5): 489–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2008.11772114 .

Montell, Gabriela. 2003. “How to Write a Statement of Teaching Philosophy.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , 27 Mar. 2003. https://www.chronicle.com/article/How-to-Write-a-Statement-of/45133 .

O’Neal, Chris, et al. 2007. “Writing a Statement of Teaching Philosophy for the Academic Job Search.” Center for Research on Learning and Teaching. University of Michigan. http://www.crlt.umich.edu/sites/default/wp-content/uploads/sites/346/resource_files/CRLT_no23.pdf .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Connection denied by Geolocation Setting.

Reason: Blocked country: Russia

The connection was denied because this country is blocked in the Geolocation settings.

Please contact your administrator for assistance.

/images/cornell/logo35pt_cornell_white.svg" alt="teaching and research interests statement"> Cornell University --> Graduate School

Teaching philosophy statement, what is a teaching philosophy statement.

A teaching philosophy statement is a narrative that includes:

- your conception of teaching and learning.

- a description of how you teach.

- justification for why you teach that way.

The statement can:

- demonstrate that you have been reflective and purposeful about your teaching.

- communicate your goals as an instructor and your corresponding actions in the classroom.

- point to and tie together the other sections of your portfolio.

What is the purpose of a teaching philosophy statement?

You generally need a teaching statement to apply for an academic position. A teaching statement:

- conveys your teaching values, beliefs, and goals to a broader audience.

- provides a set of criteria and/or standards to judge the quality of your teaching.

- provides evidence of your teaching effectiveness.

Components of a teaching philosophy statement

- educational purpose and learning goals for students

- your teaching methods

- methods for assessing students’ learning

- assessment of teaching

You also may include:

- a list of courses you have taught.

- samples of course syllabi.

- teaching evaluations.

- letters of recommendation.

- a video of a class you have taught (asked for by some universities).

Teaching values, beliefs, and goals

You should consider what you believe is the end goal or purpose of education:

- content mastery

- engaged citizenry

- individual fulfillment

- critical thinking

- problem solving

- discovery and knowledge generation

- self-directed learning

- experiential learning

What criteria are used to judge your teaching?

- student-teaching roles and responsibilities

- student-teacher interaction

- inclusiveness

- teaching methods

- assessment of learning

How do you provide evidence of your teaching effectiveness?

- peer review

- students’ comments

- teaching activities

Writing guidelines:

- There is no required content, set format, or right or wrong way to write a teaching statement. That is why writing one can be challenging.

- Make the length suit the context. Generally, they are one to two pages.

- Use present tense and the first person, in most cases.

- Avoid technical terms and use broadly understood language and concepts, in most cases. Write with the audience in mind. Have someone from your field guide you on discipline-specific jargon and issues to include or exclude.

- Include teaching strategies and methods to help people “see” you in the classroom. Include specific examples of your teaching strategies, assignments, discussions, etc. Help them to visualize the learning environment you create and the exchanges between you and your students.

- Make it memorable and unique. The search committee is seeing many of these documents—What is going to set you apart? What will they remember? Your teaching philosophy will come to life if you create a vivid portrait of yourself as a person who is intentional about teaching practices and committed to your career.

“Own” your philosophy

Don’t make general statements such as “students don’t learn through lecture” or “the only way to teach is with class discussion.” These could be detrimental, appearing as if you have all of the answers. Instead, write about your experiences and your beliefs. You “own” those statements and appear more open to new and different ideas about teaching. Even in your own experience, you make choices about the best teaching methods for different courses and content: sometimes lecture is most appropriate; other times you may use service-learning, for example.

Teaching philosophy statement dos and don’ts:

- Don’t give idyllic but empty concepts.

- Don’t repeat your CV.

- Do research on the teaching institution and disciplinary trends.

- Do keep it short (one to two pages).

- Do provide concrete examples and evidence of usefulness of teaching concepts.

- Do discuss impact of methods, lessons learned, challenges, and innovations—how did students learn?

- Do discuss connections between teaching, research, and service.

Answer these questions to get started:

- The purpose of education is to________.

- Why do you want to teach your subject?

- Students learn best by______________.

- When you are teaching your subject, what are your goals?

- The most effective methods for teaching are___________.

- I know this because__________________.

- The most important aspects of my teaching are______________.

More information on teaching philosophy statements

An excellent guide for writing your teaching philosophy statement is Occasional Paper number 23, “Writing a Statement of Teaching Philosophy for the Academic Job Search,” from the University of Michigan’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, which you can find at this page on The Teaching Philosophy and Statement .

Articles on Teaching Statements:

- “Writing the Teaching Statement” by Rachel Narehood Austin, Science Magazine

- “How to Write a Statement of Teaching Philosophy” by Gabriela Montell, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “What’s Your Philosophy on Teaching, and Does it Matter?” by Gabriela Montell, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “A Teaching Statement” by Jeffrey Marcus, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “Everything But the Teaching Statement” by Jeremy S. Clay, The Chronicle of Higher Education

- “Writing a Teaching Philosophy Statement” by Helen G. Grundman, Notices of the American Mathematical Society

Additional Resources:

- From Cornell’s Center for Teaching Innovation

- From the University of Michigan

- From University of California Berkeley

- From University of Pennsylvania

Electronic portfolios

The electronic portfolio is a way to showcase your accomplishments, skills, and philosophy on the internet. You can write a personal profile; post your CV, resume, research statement, teaching philosophy statement; give links to published articles, work samples, etc.; and post photos and other images. You can continually update it as you progress through your studies and your career. It is readably available for potential employers to see.

Sites that Host Electronic Portfolios:

- Digication (Cornell-supported option)

- Interfolio (fee-based)

- Google Sites (free)

Help at the Center for Teaching Innovation (CTI)

Coursework involving teaching portfolio development.

The course ALS 6015, “ Teaching in Higher Education ,” guides graduate students in how to prepare teaching portfolios and provides opportunity for peer and instructor feedback.

Individual Advice

By enrolling in the CTI’s new Teaching Portfolio Program , you will have access to consultations and advice on helping prepare elements of a teaching portfolio such as a teaching philosophy statement.

Workshops and Institutes

For graduate teaching assistants and postdocs considering academic positions in higher education, you could attend a teaching statement workshop as part of the Graduate School’s Academic Job Search Series , or a day-long Teaching Portfolio Institute offered by the CTI to help refine and document your teaching for the job search.

Faculty Application: Teaching Statement

Criteria for success.

Your teaching statement should…

- Describe how you think about teaching (ie, your teaching philosophy).

- Show your teaching experience, including but not limited to courses, workshops, and seminars, and connect your experience to how you will teach in the future.

- Demonstrate match with the needs and curriculum of the department to which you are applying.

- Include existing and new classes you are prepared to teach.

- Avoid typos and errors.

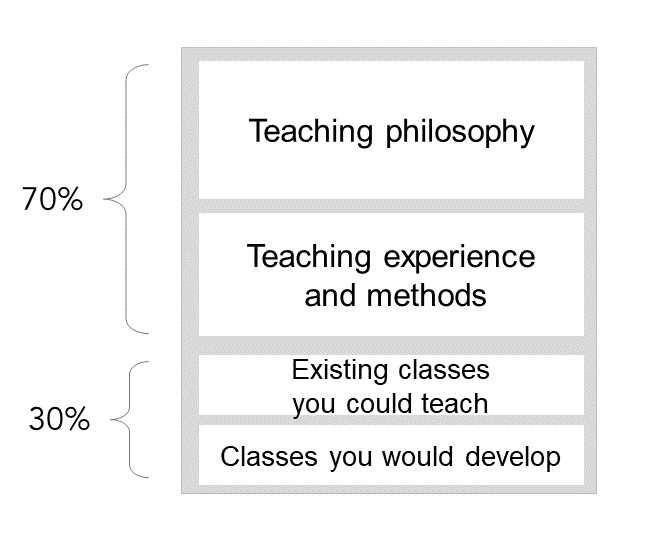

Structure Diagram

A teaching statement – sometimes called a teaching philosophy statement – generally does not have a prescribed structure. Section headings are not required but may be used to help organize the document. If specific instructions are given in the job posting, be sure to follow the guidelines for content, structure, format, and length. Unless otherwise specified, the typical length of a teaching statement for an EECS faculty application is around two pages.

Whatever structure you use, a teaching statement should include the following components: 1) your teaching philosophy (that is, how you think about being a teacher both in and out of the classroom), 2) your teaching experiences and methods, and 3) existing classes you are interested in teaching and future classes that you would develop. We recommend using a structure similar to that in the diagram below.

Identify Your Purpose

A teaching statement should do more than reiterate the Teaching Experience section of your CV. It should explain how you approach teaching, highlight your teaching capabilities and experience, and demonstrate a match with the department to which you are applying. Your teaching statement should work with the rest of your application to demonstrate your branding statement . The overall goal of a teaching statement is to demonstrate that you are ready and qualified to carry out the teaching responsibilities of a professor.

Analyze Your Audience

As with all components of a faculty application, the audience for a teaching statement is the faculty search committee. In particular, Education Officers and other faculty who are deeply invested in teaching are the most likely to read your teaching statement in depth. Your statement should be customized based on the curriculum and needs of your target institution in order to demonstrate that you are a good fit for the teaching needs of the department you are applying to.

Demonstrate how you think about teaching and learning

Your teaching statement should demonstrate how you think about teaching and learning – that is, your teaching philosophy. There is no need to reinvent the wheel; in fact, deviating too much from standard teaching methods is usually frowned upon. While there is no one best way to teach, there is a large body of literature describing effective teaching methods. Whether you draw from this literature, your own experience, or (ideally) a combination of the two, you should clearly outline what you think makes for effective teaching and what educational principles are important to you.

Your teaching statement, like the other parts of your faculty application package, should align with your branding statement . For example, if your research is at the intersection of theory and practice, your teaching methods could also stress this convergence. If applicable, you can also suggest examples for how to link your research and teaching through projects, problem sets, or other means.

You may wish to extend the teaching statement to discuss your impact as a teacher beyond the classroom. Consider other interactions with students including office hours and discussions outside of class. You may also discuss your mentorship style and experiences. When doing so, show your impact on students, which may include papers you published with them, awards, new projects and research directions, or a mentee’s success after graduation.

Support your teaching philosophy with concrete experiences and methods

While it is important to describe your teaching philosophy in your teaching statement, it is not sufficient to only do this in an abstract way. Your teaching philosophy should be supported by concrete experiences and classroom practices. Whether you are describing how you have taught in the past or how you will teach in the future, be specific and realistic. Give a clear picture of what students in your classroom will experience by being specific about techniques you will use, but avoid using jargon that is known only to people in your subfield or to formally trained educators.

When possible, explain how your past teaching experiences, whether formal or informal, have demonstrated your teaching philosophy. When you describe teaching experience, wherever possible, quantify and concretize these experiences – for example, how many class sessions you taught, how many students were in each class, or how many quizzes or problem sets you designed. You can also provide information from teaching evaluations or quote a student’s feedback about your teaching style or methods. When writing about a specific student, avoid mentioning their name or other identifying information if possible.

Leverage every possible teaching-related experience in your statement. Teaching doesn’t only mean standing at the front of a classroom and lecturing. Teaching-related experiences can include tutoring, workshops, seminars, mentoring, outreach events, volunteering, and more. All of these experiences and methods can help to make your teaching philosophy concrete and demonstrate that you are prepared to teach. They can also help you reflect on what you have learned over time, what worked well and what didn’t, and how you overcame challenges.

Especially if you don’t have much teaching experience, you can also demonstrate a growth mindset in your statement . Write about professional development courses or demonstrate a history of getting and implementing as much feedback as possible to highlight this mentality. Demonstrate knowledge of where you can go for help by doing some research into what teaching support is offered at the institution to which you are applying. An internet search for “[Institution Name] teaching center” can usually help to identify these resources. Simply, show how you have grown and will continue to grow over time and what you can offer as a teacher.

Regardless of how much teaching experience you have, your teaching statement should describe techniques and methods you will utilize in your future classes to be an effective teacher. Mention examples of classroom activities you will use and specific learning objectives you have for your students. Describe what kind of classroom environment you are striving for and elaborate on techniques you will use to create that environment in an engaging way.

Present a concrete, flexible, department-specific teaching plan

While the teaching philosophy and experiences you present in applications to different institutions are unlikely to change drastically, your statement should be tailored to demonstrate how you would fit into the department where you are applying. In addition to reflecting your branding statement , classes that you propose to teach should align with the existing curriculum of the department. Information about courses offered is usually available on a department’s website.

Demonstrate that you are able to help meet the needs of the department. To do this, list both classes that already exist at the institution that you would be able to teach and a few classes (undergraduate or graduate) you could develop to fill gaps in the curriculum. In order to suggest classes effectively, you will have to do some research into the curriculum at your target institution. The names and levels of existing classes may differ depending on the institution. The curriculum gap and the needs of the department may differ as well. Be careful not to propose the development of an already established course.

It is often difficult to know what classes are currently understaffed and what classes may already be in development. To avoid insulting anyone in the department, your suggestions should be concrete but flexible. Use language that suggests you are “prepared” or “willing” to teach or develop certain classes rather than stating what you “will” teach in the department.

MIT EECS affiliates can make an appointment with a Communication Fellow to obtain feedback on any part of their faculty application package.

Resources and Annotated Examples

Teaching statement annotated example 1.

Submitted by an MIT PhD student in 2020-2021 as part of a successful faculty application package 164 KB

Mike Carbin Teaching Statement

Submitted by Mike Carbin, now assistant professor at MIT EECS 746 KB

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

PHQ-9 indicates 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire.

Generalized estimating equations were used, adjusted for demographic characteristics, cohort year, baseline neuroticism, and history of depression (N = 858), with weighting.

A linear mixed model was used, adjusted for demographic characteristics, baseline neuroticism, and history of depression (N = 858), with weighting. The vertical dotted line denotes the beginning of the internship year, and the shaded area indicates the quarterly survey data collected before and during the internship year.

eTable 1. Annual Survey Completion by Cohort Year

eTable 2. Percentage Screening Positive for Depression

eTable 3. Mean 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) Trajectory

eMethods. SAS Code for Longitudinal Analysis of the 9-Item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9)

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Kim E , Sinco BR , Zhao J, et al. Duration of New-Onset Depressive Symptoms During Medical Residency. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7(6):e2418082. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.18082

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Duration of New-Onset Depressive Symptoms During Medical Residency

- 1 University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor

- 2 Department of Surgery, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- 3 Center for Healthcare Outcomes and Policy, Michigan Medicine, Ann Arbor

- 4 Michigan Neuroscience Institute, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

- 5 Department of Surgery, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- 6 Institute for Technology Assessment, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston

- 7 Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor

- 8 Center for Clinical Management and Research, Ann Arbor Veterans Affairs Hospital, Ann Arbor, Michigan

- 9 Department of Anesthesiology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Question Do depressive symptoms with new onset during residency training persist, and are they associated with the long-term mental health of physicians?

Findings In this cohort study of 858 resident physicians, new-onset depressive symptoms identified via positive screening among first-year interns persisted after completion of training at a level more than 3-fold higher than that of their counterparts without depression.

Meaning The persistence of new-onset depressive symptoms observed among interns in this study underscores the need to support mental health among physicians as they progress through training and beyond.

Importance The implications of new-onset depressive symptoms during residency, particularly for first-year physicians (ie, interns), on the long-term mental health of physicians are unknown.

Objective To examine the association between and persistence of new-onset and long-term depressive symptoms among interns.

Design, Setting, and Participants The ongoing Intern Health Study (IHS) is a prospective annual cohort study that assesses the mental health of incoming US-based resident physicians. The IHS began in 2007, and a total of 105 residency programs have been represented in this national study. Interns enrolled sequentially in annual cohorts and completed follow-up surveys to screen for depression using the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) throughout and after medical training. The data were analyzed from May 2023 to March 2024.

Exposure A positive screening result for depression, defined as an elevated PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater (indicating moderate to severe depression) at 1 or more time points during the first postgraduate year of medical training (ie, the intern year).

Main Outcomes and Measures The main outcomes assessed were mean PHQ-9 scores (continuous) and proportions of physicians with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10; categorical or binary) at the time of the annual follow-up survey. To account for repeated measures over time, a linear mixed model was used to analyze mean PHQ-9 scores and a generalized estimating equation (GEE) was used to analyze the binary indicator for a PHQ-9 score of 10 or greater.

Results This study included 858 physicians with a PHQ-9 score of less than 10 before the start of their internship. Their mean (SD) age was 27.4 (9.0) years, and more than half (53.0% [95% CI, 48.5%-57.5%]) were women. Over the follow-up period, mean PHQ-9 scores did not return to the baseline level assessed before the start of the internship in either group (those with a positive depression screen as interns and those without). Among interns who screened positive for depression (PHQ-9 score ≥10) during their internship, mean PHQ-9 scores were significantly higher at both 5 years (4.7 [95% CI, 4.4-5.0] vs 2.8 [95% CI, 2.5-3.0]; P < .001) and 10 years (5.1 [95% CI, 4.5-5.7] vs 3.5 [95% CI, 3.0-4.0]; P < .001) of follow-up. Furthermore, interns with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) demonstrated a higher likelihood of meeting this threshold during each year of follow-up.

Conclusions and Relevance In this cohort study of IHS participants, a positive depression screening result during the intern year had long-term implications for physicians, including having persistently higher mean PHQ-9 scores and a higher likelihood of meeting this threshold again. These findings underscore the pressing need to address the mental health of physicians who experience depressive symptoms during their training and to emphasize the importance of interventions to sustain the health of physicians throughout their careers.

Poor mental health among physicians is a growing professional concern and a public health crisis. 1 Each year, 400 US physicians die by suicide, translating to 1 or more physician deaths by suicide every day. 2 Research has demonstrated that residency training, which lasts 3 to 10 years depending on the specialty pursued, is a particularly challenging time for physician mental health. 3 , 4 Residency has several characteristics implicated in the development of depression, including long work hours and inflexible schedules limiting rest and recovery. 5 - 7 It is well-established in the general population that 1 episode of depression is associated with an increased risk of future episodes (ie, the kindling hypothesis). However, this association has not been established in the setting of residency training, which may be a transient driver of depressive symptoms secondary to a challenging work environment.

Longitudinal data evaluating mental health outcomes beyond the residency training period are lacking. Specifically, whether depressive symptoms resolve in the posttraining period is unknown, as is the potential vulnerability of a segment of the physician workforce to face future episodes of depression. 3 , 8 - 10 Identification of the long-term implications of new-onset depressive symptoms during the intern year (ie, the first year of residency) is critical (1) to understand the association between the training environment and the mental health of both the training and practicing physician workforces and (2) to identify opportunities for intervention before symptoms become severe.

In this study, we examined scores on the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) longitudinally for up to 10 years among a national sample of US physicians enrolled before the start of their internship. We aimed to quantify the persistence and severity of depressive symptoms for physicians who did and did not screen positive for depression during their first year of residency training. We hypothesized that the development of new-onset depressive symptoms as an intern was not transient but that a higher burden of depressive symptoms would persist among physicians well beyond the early years of training.

The Intern Health Study (IHS) is an ongoing annual cohort study that began in 2007 to assess the mental health of incoming first-year resident physicians (interns) who are based in the US. 11 A total of 105 residency programs have been represented in this national study. The overarching aim of the IHS is to assess the psychological, genetic, and program factors involved in the onset of depression among physicians in training. A subset of physicians recruited as interns were invited to participate in follow-up surveys of their mental health on an annual basis throughout residency training and beyond (as outlined in the Participant Recruitment section). The University of Michigan Institutional Review Board approved this cohort study. Participants provided informed consent. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology ( STROBE ) reporting guideline.

Beginning in 2007, cohorts of incoming interns (ie, graduating medical students) enrolled in the IHS before the start of residency training and were followed up quarterly during their first year of training. Interns were invited electronically to participate following match day, the day each year when graduating medical students learn their specialty and training location. Participants received between $50 and $125 in compensation, depending on the year they joined the study. The study questionnaires for single-year participants included a wide range of questions on mental health, training program features, and personal demographic measurements administered at baseline (3 months before the start of residency) and at the end of months 3, 6, 9, and 12 of their internship. Self-reported race and ethnicity were included in the current analysis due to prior research by our group, which has found that race and ethnicity may affect depressive symptoms among resident physicians. These categories were defined by the study investigators but self-reported by participants on the baseline survey as Asian, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latinx, White, other race or ethnicity (including American Indian or Alaska Native, Arab or Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander, other race or ethnicity, or multiple races or ethnicities), or unknown race or ethnicity. A subset of participants were then followed up for 1 assessment completed annually. Figure 1 describes the recruitment and retention of the annual follow-up survey participants.

After the initiation of the IHS in 2007, an adaptive participant recruitment strategy began in 2009 to recruit from previously enrolled interns. This recruitment strategy was designed to develop a continuous stream of annual data for each participant. At the beginning of the IHS (in 2007), the invitation was extended to all participants to participate in follow-up surveys on an annual basis. Beginning in 2014, participants from a University of Michigan biomarker substudy were invited each year, including participants from 3 previous cohorts (2010, 2011, and 2012). 12 In 2020, recruitment was expanded to include the entire University of Michigan intern cohorts, starting with those enrolled in 2017 onward. In 2022, all surgeons from the 2009 to 2013 cohorts not already included in the annual survey were invited. All enrolled participants in the yearly follow-up study were subsequently invited to complete a survey each year until the conclusion of the study period (eTable 1 in Supplement 1 ). Annual surveys were not conducted during 2017 and 2021 due to funding limitations. Participants were offered $25 for each annual survey completed.

Upon initial enrollment in the IHS, participants completed surveys self-reporting their demographic characteristics, such as age, race and ethnicity, partnership status, program type, and specialty. The preinternship assessment included depression (measured with the PHQ-9), neuroticism (measured with the NEO Personality Inventory), history of depression among immediate family members, and personal history of medication or psychotherapy for depression. 13 , 14 The PHQ-9 was used to measure depressive symptoms at baseline, at quarterly intervals across participant intern year, and annually (scores indicate the following: 0-4, none to minimal depression; 5-9, mild depression; 10-14, moderate depression; 15-19, moderately severe depression; and 20-27, severe depression). 14 The PHQ-9 was selected due to its high sensitivity and specificity for detecting clinically meaningful depression and its comparability to clinician-administered assessments. Participants were given 1 month to complete each survey.

An elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) correlates with a moderate to severe burden of depressive symptoms and is both sensitive and specific as a screening measure for moderate to severe depression (however, it is not a substitute for a clinical diagnosis of depression). 15 Residents with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) at the baseline survey, assessed 3 months before the internship, were excluded. Among the included participants with a baseline PHQ-9 score indicating none to mild depression (<10), an instance of an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) on at least 1 quarterly assessment during the intern year was considered a positive screening result for depression. Follow-up PHQ-9 scores on annual surveys were compared between the cohorts who did and did not meet this definition for new-onset depressive symptoms. We compared mean PHQ-9 scores and proportions of physicians who met the criteria of an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) between the 2 groups.

Longitudinal analysis was performed to evaluate the trajectory of mean PHQ-9 scores throughout follow-up using a linear mixed model. The difference between mean PHQ-9 scores was evaluated across 10 years of follow-up after internship completion and compared with the preinternship baseline. The percentage of residents with depression over time was analyzed using a generalized estimating equation model. The percentage of physicians with moderate to severe depressive symptoms was compared beginning 1 year after internship completion up to 10 years. Both the linear mixed model for mean PHQ-9 scores and the generalized estimating equation model for depression were adjusted for demographic characteristics, cohort year, baseline neuroticism scores, and a personal history of depression.

All longitudinal analyses were compared between the original dataset and a modified dataset with imputations across 20 variables to evaluate the effect of missing data on our results. Missing data were imputed with the fully conditional specification method. Imputation yielded more than 95% relative efficiency and did not affect our results. Therefore, original data without imputation were used for the final analysis.

Weights were computed in 2 stages, consistent with previous weighting strategies applied in this dataset. 5 First, selection weights were calculated from propensity scores for participating in the IHS based on the distribution of race, ethnicity, and sex among potential participants at the preinternship recruitment stage. In the propensity score analysis, the outcome was designated as participation in the IHS, and the selected covariates were binary sex, race, and ethnicity (categorized as Asian, White, or other underrepresented racial or ethnic minority). Due to small samples, underrepresented minority groups were combined into a single category. The propensity score weight was calculated as 1/(propensity score).

Poststratification weights were calculated from the annual distributions of race, ethnicity, and sex from the Association of American Medical Colleges database. The overall weight was the product of the selection and poststratification weights. The final weight was the overall weight, truncated at the 95th percentile.

All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc). The analytic code is provided in the eMethods in Supplement 1 . The data were analyzed from May 2023 to March 2024.

Of the 1868 individuals invited to participate in the annual follow-up surveys, 1049 (56.2%) agreed ( Figure 1 ). We excluded individuals who were missing PHQ-9 data on any of the annual or quarterly surveys (155 [8.3%]) or had an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) at baseline (36 [1.8%]), resulting in 2867 follow-up assessments of 858 individual physicians. The mean (SD) age of participants was 27.4 (9.0) years; 53.0% (95% CI, 48.5%-57.5%) were women and 47.0% (95% CI, 42.5%-51.5%) were men ( Table ). Participants identified as Asian (36.6% [95% CI, 32.1%-41.1%]), Black (4.4% [95% CI, 2.0%-6.7%]), Hispanic (6.1% [95% CI, 3.5%-8.7%]), White (35.3% [95% CI, 31.7%-38.9%]), or other or unknown race or ethnicity (17.6% [95% CI, 13.4%-21.8%]). The mean (SD) follow-up from the completion of the intern year was 5 (3) years. Of the 858 physicians in the final analytic sample, 302 (35.2%) reported having depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score ≥10) during the intern year on at least 1 quarterly survey.

Physicians who experienced new-onset depressive symptoms during their intern year were more likely to be female, to report higher baseline PHQ-9 and NEO scores, and to have a personal or family history of depression ( Table ). No association was observed between depressive symptomatology during the intern year and a prior history of receiving medication or psychotherapy for depression.

We compared the proportion of physicians with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) indicating moderate to severe depressive symptoms at each year of annual follow-up between those who did and did not have an elevated PHQ-9 score during their intern year. The proportion of physicians who exceeded this threshold was higher at every year of follow-up among those who screened positive for depression at least once during their intern year compared with those who did not. A total of 21.9% of participants (95% CI, 15.6%-29.8%) who screened positive for depression during the internship also screened positive 1 year after completing their intern year. In contrast, only 6.6% (95% CI, 4.2%-10.3%) of the cohort with a PHQ-9 score of less than 10 during their intern year screened positive for depression in the first year of follow-up ( Figure 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ). At 5 years after their internship, 8.8% of participants (95% CI, 5.8%-13.1%) who screened positive for depression during their intern year continued to exceed this PHQ-9 threshold, compared with just 2.4% (95% CI, 1.4%-4.3%) in the cohort without elevated PHQ-9 scores during their intern year ( P < .001). Eight years after internship completion, reflecting the early years of independent practice for most participants, 8.9% of interns (95% CI, 5.7%-13.5%) with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) during their intern year still exceeded this threshold, compared with just 3.7% (95% CI, 2.2%-6.2%) among those without an elevated score during their intern year ( P = .015; Figure 2 and eTable 2 in Supplement 1 ).

Among physicians with new-onset depressive symptoms as interns, mean PHQ-9 scores remained higher throughout follow-up compared with those without an elevated PHQ-9 score (<10) throughout their internship. Although it did not exceed the standard PHQ-9 threshold of 10 suggestive of moderate to severe depression, the mean PHQ-9 score at 1 year after internship completion was nearly 2-fold higher in the group who had experienced more depressive symptoms as interns (6.5 [95% CI, 6.1-6.9] vs 3.9 [3.6-4.2]; P < .001). This difference remained statistically significant across all 10 years of follow-up ( Figure 3 and eTable 3 in Supplement 1 ). For example, among interns who screened positive for depression (PHQ-9 score ≥10) during their internship, mean PHQ-9 scores were significantly higher at both 5 years (4.7 [95% CI, 4.4-5.0] vs 2.8 [95% CI, 2.5-3.0]; P < .001) and 10 years (5.1 [95% CI, 4.5-5.7] vs 3.5 [95% CI, 3.0-4.0]; P < .001) of follow-up. The mean PHQ-9 scores for both groups never returned to baseline ( Figure 3 ). At 10 years after internship completion, physicians who screened positive for depression during their internship still had higher rates of positive depression screening (12.6% [95% CI, 5.9%-24.7%] vs 7.7% in the general population).

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the potential persistence of depressive symptoms after a physician’s first year in training in the US. Although previous studies have described an increase in the level of depressive symptoms during the first year of training, prior studies have not tracked these symptoms as physicians progress through training and into practice. 3 Using a prospective cohort design and a nationally representative sample of physicians, we observed that the development of moderate to severe depressive symptoms as an intern was associated with worse long-term mental health outcomes. These findings highlight that the early years of medical training not only result in higher transient levels of depression, but they also may have lasting implications for the long-term health of the physician workforce.

Notably, screening positive for depression during the intern year was associated with a higher likelihood of screening positive for depression after completing the first years of medical training. The most significant difference between groups was noted 1 year after completion of the internship, with 21.9% (95% CI, 15.6%-29.8%) of physicians with an elevated PHQ-9 score (≥10) as interns still exceeding this threshold for depression, a level more than 3-fold higher than that for physicians who did not screen positive for depression during their internship (6.6% [95% CI, 4.2%-10.3%]; P < .001). Although rates of positive depression screening decreased steadily over time, physicians who screened positive for depression during their internship still had higher rates of positive depression screening 10 years after internship completion. In addition to rates higher than their physician peers, these physicians also exceeded the prevalence of depression among similarly aged adults in the general population (12.6% [95% CI, 5.9%-24.7%] in this study vs 7.7% in the general population). 16

The second key finding relates to mean PHQ-9 scores between groups and for the entire study population. For both groups of interns, PHQ-9 scores remained higher than their baseline (before residency). However, mean scores of both groups returned to well below the elevated PHQ-9 threshold (≥10) by the completion of training. Interns with more depressive symptoms continued to have a higher burden of depressive symptoms long after completion of training. After the initial spike in depressive symptoms during the internship ( Figure 3 , vertical line), there was a steady decrease in PHQ-9 scores for both groups. Yet the difference in means between groups remained statistically significant throughout the follow-up period. Taken collectively, these findings suggest that depressive symptoms early in training may often persist throughout a physician’s early career trajectory.

Our findings have many important implications. These results suggest that accepting depressive symptoms among training doctors as commonplace may translate to increased depressive symptoms for nearly a decade among practicing physicians. Physician mental health was exacerbated during the recent COVID-19 pandemic, but our findings suggest that medical trainees have higher rates of depressive symptoms that have long preceded the pandemic. Finally, our findings suggest (to our knowledge, for the first time) that addressing resident mental health may improve the long-term mental health of our professional workforce.

Sleep duration and hours worked are both associated with an increased risk of depression among medical trainees. Early work from the IHS demonstrated that for each additional hour of work, the risk of depression increased by 5%; for each hour of less sleep, the risk of depression increased by 59%, even when accounting for an individual’s sleep quality measured before internship training. 17 Although duty hours have improved in US residency programs (albeit not equally across all specialties), substantial work remains in this domain. 18 Recent work from our group and others suggests that reducing duty hours has a protective effect on the development of depressive symptoms during training. 6 , 19 - 21 Although this solution is not simple and all-encompassing, future research should examine whether depression during the intern year is prevented by reduced duty hours and increased hours slept and whether this, in turn, improves the long-term mental health of physicians.

Our research also highlights the need to better support mental health among physicians as they progress through training and to destigmatize mental health care within our professional culture. Universal well-being needs assessments for counseling services, opt-out counseling programs, and autoenrollment of interns in mental health resources to decrease barriers to access and overcome stigma should be further considered as potential solutions. 22 , 23 Beyond efforts targeted at individuals, ongoing work to address workplace culture for training physicians should be widely implemented. 19 , 20 , 24 Systems-based interventions may include further evaluation of the feedback and assessment methods and recognition of the importance of allowing time to practice basic preventative health care. Understanding these interconnected elements is imperative to understanding the relationship between residency and the mental health of residents and the workforce.

Many future areas of research are critical for reducing depression among US physicians. Further testing of the kindling hypothesis, or the concept that an initial episode of depression may serve as an independent risk factor for future depressive episodes, should be pursued using methods to support causal inferences (eg, target trial emulation, instrumental variables). Future research may also examine how mental illness affects workforce sustainability, including potential physician shortages in critical areas such as general surgery and primary care. Further research is needed to better understand the association between depression and attrition and to explore potential consequences on physician shortages. Routine screening for depression may also be considered to help identify and target interventions for those most at risk of developing depression. Finally, focused attention is necessary for subgroups underrepresented in the literature, specifically gender-diverse and nonheterosexual groups. Emerging evidence indicates that sexual minority (ie, bisexual or homosexual) individuals in medical training experience higher levels of depression than their heterosexual counterparts. 25 Previous studies involving IHS participants reported that sexual minority individuals enter residency with higher PHQ-9 scores than their heterosexual peers and experience a more pronounced increase in depressive symptoms throughout their internship. 26 As inclusivity in our profession increases, there is an ongoing need to support this diverse workforce appropriately.

This study has some limitations. The observational design limits the establishment of causal relationships. We cannot determine whether depression arising during the intern year increases a physician’s risk of later depression or whether depression that surfaces during the internship is a marker for underlying risk. Although the PHQ-9 used on both quarterly and annual surveys has high sensitivity and specificity in assessing diagnoses of major depressive disorder according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition , criteria, we recognize that our interpretations are limited to the PHQ-9 outcome measure as opposed to a clinical diagnosis of depression. 15 Selection bias may also be implicated, given that study initiation and continued participation were based on voluntary enrollment. Statistically, we aimed to minimize this bias by including weights in our analysis.

The findings of this cohort study underscore that the increase in depressive symptoms observed during medical internships, although most notable in the first year of training, may persist for many trainees and physicians. This research suggests that there may be lasting consequences of depressive symptoms well beyond the years spent in medical training, emphasizing the need to support training doctors to safeguard the long-term health of those entrusted to ensure the health of others.

Accepted for Publication: April 20, 2024.

Published: June 21, 2024. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.18082

Open Access: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the CC-BY License . © 2024 Kim E et al. JAMA Network Open .

Corresponding Author: Tasha M. Hughes, MD, MPH, Department of Surgery, University of Michigan Medical School, 1500 E Medical Center Dr, Ann Arbor, MI 48109 ( [email protected] ).

Author Contributions: Drs Bohnert and Hughes had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Concept and design: Kim, Cunningham, Bohnert, Hughes.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Kim, Sinco, Hughes.

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Statistical analysis: Kim, Sinco, Zhao, Fang.

Obtained funding: Sen.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Kim, Sinco, Zhao, Fang, Cunningham.

Supervision: Cunningham, Sen, Hughes.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant R01-MH101459 from the National Institutes of Health for the development and maintenance of the Intern Health Study (Dr Sen) and by a Research Advisory Committee grant from the University of Michigan Department of Surgery (Dr Hughes).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Data Sharing Statement: See Supplement 2 .

- Register for email alerts with links to free full-text articles

- Access PDFs of free articles

- Manage your interests

- Save searches and receive search alerts

COMMENTS

Possible Research Statement Content: 1. A summary of your research and how it contributes to the broader field. 2. Specific examples that illustrate your results and impacts (e.g., major publications, breakthroughs, unique techniques you employ). 3. Who you've collaborated with or will collaborate with in your field or the new department.

Teaching and research statements are a summary of work and teaching philosophy, both of which can be very complicated statements. The research statement discusses a person's work in a way that helps people understand one's interests and focus in his or her work. It should address several points clearly and concisely:

First, your teaching statement should be student centered (like your teaching!), which means focusing on the student outcomes you want to achieve through your teaching methods. In addition, you probably have more experience than you think. For example, you can pull from whatever teaching/mentoring experiences you have encountered in your ...

comparative measure. As a testament to my teaching ability, I recently received Harvard's Certificate of Distinction in Teaching. Teaching Experience In both fall 2009 and spring 2011, I served as the teaching fellow to Torben Iversen for Comparative Political Economy: Developed Countries. The class covered various topics

As a teacher, I hope to advance the intellectual development of my students to the best of my abilities. I am confident that my past teaching experiences, strong academic background, and communication skills coupled with thorough preparation and enthusiasm for the subject will make me an excellent teacher. Title. teaching-statement.PDF. Author.

The research statement (or statement of research interests) is a common component of academic job applications. It is a summary of your research accomplishments, current work, and future direction and potential of your work. The statement can discuss specific issues such as: The research statement should be technical, but should be intelligible ...

6. Collaboration (current/potential). 7. Future direction(s) of your research/scholarship. • Brief and well-organized • No grammatical, spelling, or punctuation errors • Aim for 1-3 pages • Single-spaced or 1.5 spaced • Concise paragraphs • Short bulleted lists can be used • Clear subject headings can be helpful.

An effective teaching statement involves both reflection and research. Thinking about your teaching and your goals can be helpful before you begin writing or revising your teaching statement. This process can also prepare you for interview questions that address teaching, should your application lead to an interview.

HOW RESEARCH RELATES TO YOUR TEACHING ONLY TEACHING RESEARCH + TEACHING Your EXPERIENCE with research will help you bring real-world examples into your instruction. You are KNOWLEDGEABLE about current findings in your field. You can help TRAIN students to think like a scientist. Your RESEARCH RESULTS can be discussed in your

How do your research and disciplinary context influence your teaching? How do the identities and backgrounds of both you and your students affect teaching and learning in your classes? How do you account for different styles of learning? Questions to Consider for a Research Statement:

A good research interest statement sample can be hard to find. Still, it can also be a beneficial tool for writing one and preparing for a grad school application or post-graduate position. Your research interest statement is one of the key components of your application to get into grad school.In a few cases, admissions committees have used it instead of an interview, so it is important to ...

A research statement is a one to three page document that may be required to apply for an ... (e.g., personal statement, teaching statement, statement of diversity, resume/cv, cover letter, etc.) describing your academic career, so be discriminating and strategic ... specific interest in a field/area of research: "My primary academic ...

A Teaching Statement can address any or all of the following: Your conception of how learning occurs. A description of how your teaching facilitates student learning. A reflection of why you teach the way you do. The goals you have for yourself and for your students. How your teaching enacts your beliefs and goals.

1: Summary of Quantitative Teaching Evaluations. Question Score. The class as a whole was: 4.11/5 The content of the class was: 4.01/5 The instructor's contribution to the class was: 4.41/5 The instructor's effectiveness in teaching the subject matter was: 4.26/5. Statement of Teaching Interests, Kevin R. Covey 2.

• "Writing a research statement", Jim Austin (2002), sciencecareers.org • "The truth behind teaching and research statements", Peter Fiske (1997) Some last words.... Advice from UCSF faculty: 1. Be personal. This document is about you: who you are as a scientist, what interests you, where you see your research going in the future.