The Importance of Technological Change in Shaping Generational Perspectives

If we name each generation based on the technological conditions it experienced, generations may soon encompass only a few years apiece.

“There are a number of labels to describe the young people currently studying at school, college and university,” Ellen John Helsper and Rebecca Evnon wrote in a 2010 article in the British Educational Research Journal . “They include the digital natives, the net generation, the Google generation or the millenials. All of these terms are being used to highlight the significance and importance of new technologies within the lives of young people.”

What seemed noteworthy a decade ago is now commonplace: Slicing the population into ever-narrower generations, each defined by its very specific relationship to technology, is fundamental to how we think about the relationship between age, culture, and technology.

But generation gaps did not begin with the invention of the microchip. What’s new is the fine-slicing of generational divides, the centrality of technology to defining each successive generation. Both of these developments rest on a remarkably intellectual innovation: the idea of generations as socially significant categories.

As Marius Hentea points out in his article “ The Problem of Literary Generations :” “[t]he sociological meaning of ‘generation’ is a post-Enlightenment development.” We’ve moved from a view of generations as biological “in the sense of the generation of a butterfly from a caterpillar,” as Hentea puts it, to a view of generations as sociological. Hentea argues that three nineteenth-century developments were responsible for this emergent concept of generational divides, the first of which was democratization :

By no longer limiting political power to a defined group but rather encouraging political participation across social strata, democracy eased youth into public life in a way other regimes had proven incapable of doing. At the same time, democratization paradoxically created generational categories. With aristocratic privileges abolished and republican duties diminished, the generation provided a fallback for social belonging: not everyone can belong to my generation, so the vestigial desire for distinction is satisfied, but at the same time, no one remains without a generation, so the democratic impulse toward equality is met.

Another important factor was centralization : “the spectacular rise of the bureaucratic state and its disciplinary instruments of control and categorization.” Last but not least, Hentea notes, was the role of technologization :

As technology advanced ever more quickly in the nineteenth century, differentiation based on age became even more important: the young had at their disposal tools their elders did not. The concentration of rapid technological change in urban centers led to youth gaining economic and social advantages at the same time that the transmission of accumulated knowledge and experience from elders lost its relevance for changing industries.

If the role of technology in shaping an emergent generational consciousness seems obvious to us now, however, it far from evident to earlier observers. “Why does contemporary western civilization manifest an extraordinary amount of parent-adolescent conflict?” Kinsley Davis asked in his article “ The Sociology of Parent-Youth Conflict .” In 1940, apparently, it was still possible to see inter-generational conflict as a novel and perplexing mystery.

To one of Davis’ contemporaries, the answer was clear: “the two generations in question have lived under such different economic conditions,” wrote Julien Brenda in a 1938 article, “ The Conflict of Generations in France .” “The old generation was a happy one—unusually happy, I venture to say; the young generation is unhappy, hard pressed by circumstances.”

Wallace Stegner picks up the theme of generational angst in his 1949 article, “ The Anxious Generation .” Writing of the twenty-somethings who came of age during or just after World War II, Stegner says:

They could no more have missed awareness of the tension and fear in their world than a bird could avoid awareness of wind. Far more has been taken from them than had been taken from preceding generations: politically, only uncertainty and fear and the Cold War is left them; the atom bomb is a threat such as the world has a never faced; if by a miracle we escape another war and the bomb, there is always the longer-term disaster of an incredibly multiplying world population and the shrinkage and wastage of world resources and the diminishing of world food supplies.

If that rather grim assessment implicitly rests on a set of assumptions about the impact of technological change—for what else is an atom bomb, if not a technological innovation?—then that assessment only seems apparent through our twenty-first century lens. In the middle of the last century, many still thought it preposterous to attribute generational differences to technological innovation. Writing in the middle of World War II, C. E. Ayres wrote that:

No serious student attributes the evils of the age to its machines. Popular essayists sometimes write as though tanks and airplanes were responsible for the bloodshed which is now going on, and novelists occasionally draw pictures of the horrors of a future in which life will have become wholly mechanized, with babies germinating in test tubes, “scientifically” maimed for the “more efficient” performance of industrial tasks. But this of course is literary nonsense…

Just a few years later, however, A. J. Jaffe would take a very different position in the pages of Scientific Monthly. “ Of the factors causing change in our society, one of the most important is technology—important new inventions as well as minor technical innovations,” Jaffe wrote in “ Technological Innovations and the Changing Socioeconomic Structure .” Making the case for the importance of studying technological change, Jaffe argued that:

Perhaps the single most important reason for studying technological change is to afford society a mechanism for predicting the social changes which are expected to occur… any thinking that will permit a society to better adapt itself to the inevitable changes which will occur—changes stemming in large measure from technological innovations—will be better able to meet such changes.

If that seems like a rather rapid turnaround on the importance of technological change in shaping generational perspectives, well, the pace of change was very much the point. In a 1945 article, “ Characteristics of an Age of Change ,” J. B. McKinney observed that “change, which was hitherto a gradual process, has become, for us, cataclysmic; it has become a tidal wave that threatens to overwhelm us. A decade to-day is the equivalent of a generation, and standards and values topple over like ninepins.”

From this rapid change, it was perceived, sprang generational discord. In his 1940 article, Davis argued that:

Extremely rapid change in modern civilization… tends to increase parent-youth conflict, for within a fast-changing social order the time-interval between generations, ordinarily but a mere moment in the life of a social system, become historically significant, thereby creating a hiatus between one generation and the next. Inevitably, under such a condition, youth is reared in a milieu different from that of the parents; hence the parents become old-fashioned, youth rebellious, and clashes occur which, in the closely confined circle of the immediate family, generate sharp emotion.

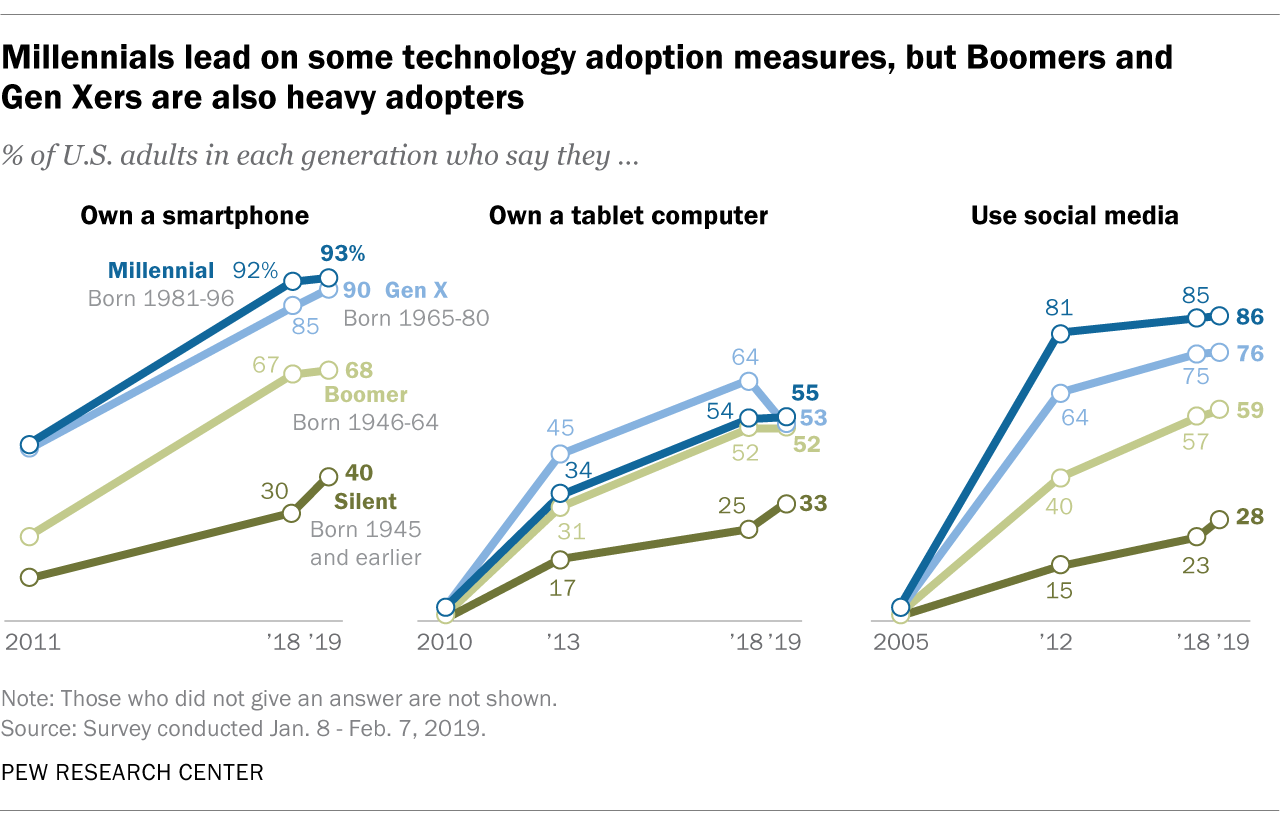

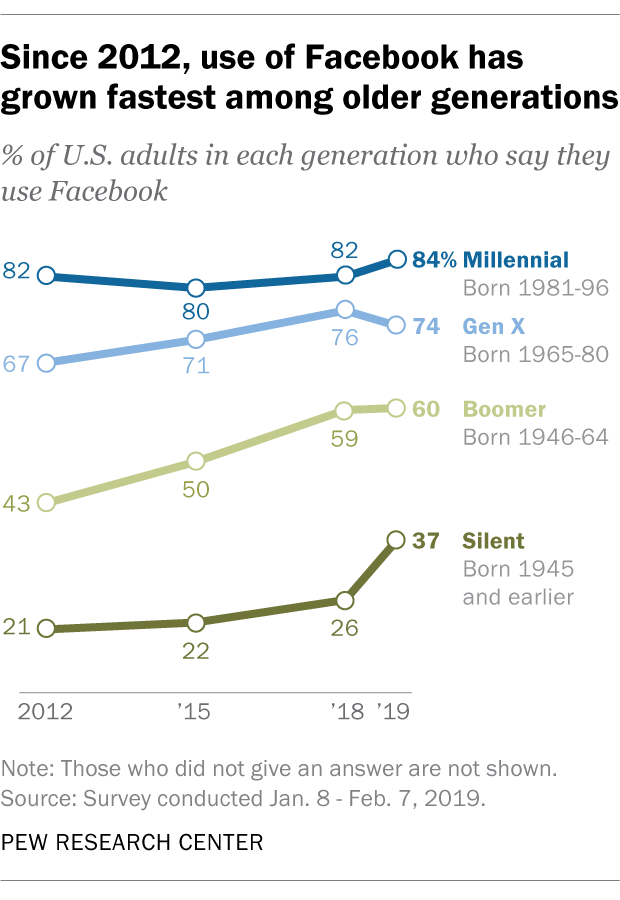

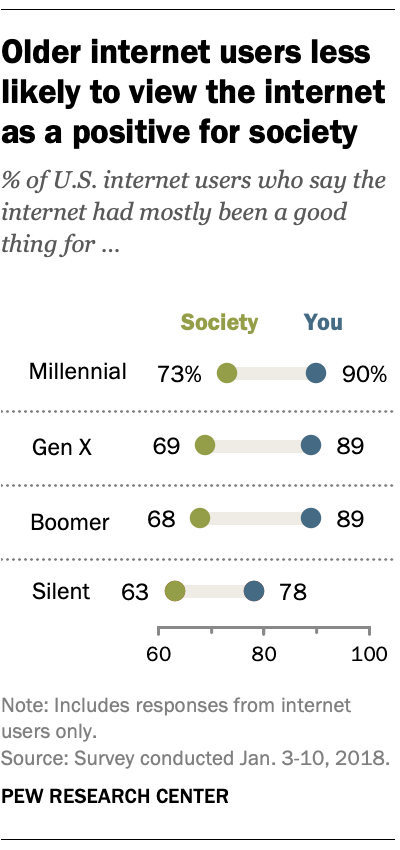

This 80-year-old assertion does an excellent job of anticipating our current tendency to label a new generation every decade, based on its unique relationship to emergent technology. Smartphones have only been in widespread use for a decade, but they’re now so fundamental to our daily lives that it’s hard to remember life without them. How could we possibly see those who can remember life before the smartphone as part of the same generation as those who’ve known nothing else? How could we see kids who’ve grown up on YouTube as part of the same generation that still watched actual TV? Doesn’t the leap from Facebook to SnapChat constitute its own profound generational divide?

Weekly Newsletter

Get your fix of JSTOR Daily’s best stories in your inbox each Thursday.

Privacy Policy Contact Us You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the provided link on any marketing message.

As the pace of technological innovation continues to accelerate, and as each successive round of innovation becomes more widely disseminated, it’s hard to imagine a return to the days when sociological generations spanned multiple decades. If you believe that technological conditions profoundly shape the life experience and perspectives of each successive generation, then those generations will only get narrower.

But that accuracy will come at a price. If we name each generation based on the specific technological conditions it experienced during childhood or adolescence, we may soon be dealing with generations that encompass only a few years apiece. At that point, the very idea of “generations” will cease to have much utility for social scientists, since it will be very hard to analyze attitudinal or behavioral differences between generations that are just a few years part. We’ll have come full circle, back to the early nineteenth century, when the only way to think of generations was in terms of biology, not sociology.

JSTOR is a digital library for scholars, researchers, and students. JSTOR Daily readers can access the original research behind our articles for free on JSTOR.

Get Our Newsletter

More stories.

- What’s a Mental Health Diagnosis For?

- The Seventeenth-Century Space Race (for the Soul)

- The Love Letter Generator That Foretold ChatGPT

Growing Quickly Helped the Earliest Dinosaurs

Recent posts.

- Burlesque Beginnings

- Power over Presidential Records

Support JSTOR Daily

Sign up for our weekly newsletter.

Political Analysis

Home > Political Analysis > Vol. 20 (2019)

The Technology Gap Across Generations: How Social Media Affects the Youth Vote

Yamiemily Hernandez , Seton Hall University

There appears to exist today a generational tug-of-war between Millennials and Baby Boomers. Baby Boomers tend to see Millennials as lazy kids who do not appreciate the value of hard work, spend all day glued to their cell phones, and expect successes to be handed to them on a silver platter. Millennials seem to think that Boomers have harbored all the wealth and success in America without thinking about future generations; they cannot wait for Boomers to retire and create vacancies for key positions in companies. While the accusations generations make against each other rely on stereotypes and may not be entirely truthful, the reality is that the age gap between the Millennial generation and the Baby Boomer generation is one of the largest generational gaps in American history.

Generational differences play an important role in American politics. The defining characteristics of each generation and the emerging age gap have the power to shape politics, elections, and voting trends both now and in the years to come. In a nutshell, Millennials are becoming increasingly liberal in their views and the older generations, like the Baby Boomers, tend to hold more conservative views. Young citizens are less religious, more concerned about social and public policy issues, and favor an activist government. They stray from traditional values and are more accepting of different social groups. Several factors go in to determining how a generation of voters will identify politically and how they vote. Some of the factors that influence political behavior include parent-instilled values, inherent political background, education, political environment, and the media (Fisher, 2014). There also exists a newer and much different explanation for how young voters vote the way that they do: the emergence and usage of social media. Understanding the social media explanation could be significant for the future of campaigning and elections. This paper will analyze the evolution of social media usage in the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections and the ways in which social media influences youth political behavior.

Recommended Citation

Hernandez, Yamiemily (2019) "The Technology Gap Across Generations: How Social Media Affects the Youth Vote," Political Analysis : Vol. 20, Article 1. Available at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/pa/vol20/iss1/1

Since May 23, 2019

Included in

American Politics Commons , Social Influence and Political Communication Commons , Social Media Commons

- Journal Home

- About This Journal

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Most Popular Papers

- Receive Email Notices or RSS

Advanced Search

ISSN: 2474-2295

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Generational Differences and the Integration of Technology in Learning, Instruction, and Performance

- First Online: 01 January 2013

Cite this chapter

- Eunjung Oh Ph.D. 5 &

- Thomas C. Reeves Ph.D. 6

31k Accesses

32 Citations

1 Altmetric

Generational differences have been widely discussed; attention to and speculation on the characteristics of the Millennial Generation are especially abundant as they pertain to the use of educational technology for education and training. A careful review of the current popular and academic literature reveals several trends. First, whether based on speculation or research findings, discussion has focused on traits of the newer generations of students and workers and how their needs, interests and learning preferences can be met using new media, innovative instructional design and digital technologies. Second, generally speaking, although in the past few years there have been more critical and diverse perspectives on the characteristics of the Millennial Generation reported in the literature than before, more substantive studies in this area are still necessary. This chapter discusses trends and findings based upon the past 10 years’ literature on generational differences, the Millennial Generation, and studies and speculations regarding school and workplace technology integration that is intended to accommodate generational differences. There is still a lack of consensus on the characteristics of the newer generation sufficient to be used as a solid conceptual framework or as a variable in research studies; thus, research in this area demands an ongoing, rigorous examination. Instead of using speculative assumptions to justify the adoption of popular Web 2.0 tools, serious games and the latest high tech gear to teach the Millennial Generation, approaches to integrating technology in instruction, learning, and performance should be determined by considering the potential pedagogical effectiveness of a technology in relation to specific teaching, learning and work contexts. Clearly, today’s higher education institutions and workplaces have highly diverse student bodies and work forces, and it is as important to consider the needs of older participants in learning with technology as it is to consider those of the younger participants. Recommendations for future research and practices in this area conclude the chapter.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Improving Learning and Performance in Diverse Contexts: The Role and Importance of Theoretical Diversity

Technology Education: History of Research

Bauerlein, M. (2008). The dumbest generation: How the digital age stupefies young Americans and jeopardizes our future (Or, don’t trust anyone under 30) . New York, NY: Tarcher.

Google Scholar

Bennett, S., & Maton, K. (2010). Beyond the digital natives debate: Towards a more nuanced understanding of students’ technology experiences. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26 (5), 321–331.

Article Google Scholar

*Bennett, S., Maton, K., & Kervin, L. (2008). The ‘digital natives’ debate: A critical review of the evidence. British Journal of Educational Technology, 39 (5), 775–786.

Bullen, M., Morgan, T., & Qayyum, A. (2011). Digital learners in higher education: Generation is not the issue. Canadian Journal of Learning Technology , 37 (1). Retrieved from http://www/cjlt.ca/index.php/cjlt/article/view/550

Carr, N. (2011). The shallows: What the internet is doing to our brains . New York, NY: W. W. Norton.

Caruso, J. B., & Kvavik, R. B. (2005). ECAR study of students and information technology , 2005 : Convenience , connection , control and learning . Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research. Retrieved from http://net.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ERS0506/ekf0506.pdf

Charsky, D., Kish, M. L., Briskin, J., Hathaway, S., Walsh, K., & Barajas, N. (2009). Millennials need training too: Using communication technology to facilitate teamwork. TechTrends, 53 (6), 42–48.

Coinsidine, D., Horton, J., & Moorman, G. (2009). Teaching and reading the Millennial Generation through media literacy. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 52 (6), 471–481.

Collins, A., & Halverson, R. (2009). Rethinking education in the age of technology: The digital revolution and schooling in America . New York, NY: Teacher College Press.

Correa, T., Hinsley, A. W., & Zúñiga, H. G. D. (2010). Who interacts on the Web? The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior, 26 (2), 247–253.

Eisenberg, M. (2008). Information literacy: Essential skills for the information age. DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology, 28 (2), 39–47.

Elmore, T. (2010). Generation iY: Our last chance to save their future . Norcross, GA: Poet Gardener Publishing.

Goldberg, B., & Pressey, L. C. (1928). How do children spend their time? The Elementary School Journal, 29 (4), 273–276.

Hanewald, R. (2008). Confronting the pedagogical challenge of cyber safety. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 33 (3), 1–16.

Head, A., & Eisenberg, M. (2010). Truth be told : How college students evaluate and use information in the digital age (Project Information Literacy Progress Report). Seattle, WA: University of Washington’s Information School. Retrieved from http://projectinfolit.org/pdfs/PIL_Fall2010_Survey_FullReport1.pdf

Howe, N., & Nadler, R. (2012). Why generations matter: Ten findings from LifeCourse Research on the Workforce. Retrieved from http://www.lifecourse.com/services/generations-in-the-workforce/white-paper.html

*Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000). Millennials rising: The next great generation. New York, NY: Vintage Books.

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (1991). Generations: The history of America’s future, 1584 to 2069. New York: William Morrow & Company.

International Society for Technology in Education. (2011, December 22). NETS for students. Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/standards/nets-for-students/nets-student-standards-2007.aspx

Jackson, M. (2009). Distracted: The erosion of attention and the coming dark age . Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

Jenkins, H. (2009). Confronting the challenges of participatory culture: Media education for the 21st century . Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jonassen, D. H., & Reeves, T. C. (1996). Learning with technology: Using computers as cognitive tools. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology (pp. 693–719). New York, NY: Macmillan.

*Kennedy, G., Dalgarno, B., Bennett, S., Gray, K., Waycott, J., Judd, T., et al. (2009). Educating the net generation : A handbook of findings for practice and policy . Retrieved from http://www.netgen.unimelb.edu.au/outcomes/handbook.html

Kim, B., & Reeves, T. C. (2007). Reframing research on learning with technology: In search of the meaning of cognitive tools. Instructional Science, 35 (3), 207–256.

Lancaster, L. C., & Stillman, D. (2010). The m-factor: How the millennial generation is rocking the workplace . New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Martin, C. A., & Tulgan, B. (2002). Managing the generational mix . Amherst, MA: HRD Press.

McKenney, S. E., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting educational design research . New York, NY: Routledge.

Mishna, F., Cook, C., Saini, M., Wu, M.-J., & MacFadden, R. (2011). Interventions to prevent and reduce cyber abuse of youth: A systematic review. Research on Social Work Practice, 21 (5), 5–14.

Oblinger, D., & Oblinger, J. (Eds.). (2005). Educating the Net Gen . Washington, DC: EDUCAUSE.

*Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9 (5), 1–6.

*Prensky, M. (2010). Teaching digital natives: Partnering for real learning . Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

*Reeves, T. C., & Oh, E. (2007). Generation differences and educational technology research. In J. M. Spector, M. D. Merrill, J. J. G. van Merriënboer, & M. Driscoll (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 295–303). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Rheingold, H. (2012). Net smart: How to thrive online . Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Ribble, M. S., Bailey, G. D., & Ross, T. W. (2004). Digital citizenship: Addressing appropriate technology behavior. Learning & Leading with Technology, 32 (1), 6–11.

Rideout, V. J., Foehr, U. G., & Roberts, D. F. (2010). Generation M2 media in the lives of 8 - to 18 - year - olds : A Kaiser Family Foundation study . Retrieved from http://www.kff.org/entmedia/upload/8010.pdf

Rosen, L. D. (2010). Rewired: Understanding the igeneration and the way they learn . New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

Stout, H. (2010, October 15), Toddlers’ favorite toy: The iPhone. The New York Times . Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2010/10/17/fashion/17TODDLERS.html?pagewanted=all

Tapscott, D. (2009). Grown up digital: How the net generation is changing your world . New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone together: Why we expect more from technology and less from each other . New York, NY: Basic Books.

*Twenge, J. M. (2006). Generation me: Why today’s young Americans are more confident, assertive, entitled—and more miserable than ever before . New York, NY: Free Press.

*Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2009). The narcissism epidemic: Living in the age of entitlement. New York, NY: Free Press.

van den Akker, J., Gravemeijer, K., McKenney, S., & Nieveen, N. (2006). Educational design research . London: Routledge.

Word (Version 2010) [Microsoft Office 2010]. Redmond, WA: Microsoft.

Zemke, R., Raines, C., & Filipczak, B. (2000). Generations at work: Managing the class of veterans, boomers, x-ers, and nexters in your workplace . New York, NY: AMACON.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Foundations, Secondary Education, John H. Lounsbury College of Education, Georgia College & State University, 079, Milledgeville, GA, 31061, USA

Eunjung Oh Ph.D.

Learning, Design, and Technology, College of Education, The University of Georgia, 325C Aderhold Hall, Athens, GA, 30602-7144, USA

Thomas C. Reeves Ph.D.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eunjung Oh Ph.D. .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

, Department of Learning Technologies, C, University of North Texas, North Elm 3940, Denton, 76207-7102, Texas, USA

J. Michael Spector

W. Sunset Blvd. 1812, St. George, 84770, Utah, USA

M. David Merrill

, Centr. Instructiepsychol.&-technologie, K.U. Leuven, Andreas Vesaliusstraat 2, Leuven, 3000, Belgium

Research Drive, Iacocca A109 111, Bethlehem, 18015, Pennsylvania, USA

M. J. Bishop

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2014 Springer Science+Business Media New York

About this chapter

Oh, E., Reeves, T.C. (2014). Generational Differences and the Integration of Technology in Learning, Instruction, and Performance. In: Spector, J., Merrill, M., Elen, J., Bishop, M. (eds) Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_66

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-3185-5_66

Published : 22 May 2013

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-1-4614-3184-8

Online ISBN : 978-1-4614-3185-5

eBook Packages : Humanities, Social Sciences and Law Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, generational differences in technology behaviour: comparing millennials and generation x.

ISSN : 0368-492X

Article publication date: 17 January 2020

Issue publication date: 22 October 2020

There are differences in the motivations underlying technology behaviour in each generational group; and there may be variances in the way each generational group uses and gets engaged with technology. In this context, this study aims to address the following questions: “Does generational cohort influence technology behaviour?” and if so: “What are the main motivations underlying Millennials and Generation X technology behaviour?”.

Design/methodology/approach

For this purpose, based on the uses and gratifications theory this study examines technology behaviour through multi-group structural equation modelling, drawing on a sample of 707 millennials and 276 Generation X individuals

Research findings indicate that millennials mostly use and get engaged with technologies for entertainment and hedonic purposes; while Generation X individuals are mainly driven by utilitarian purposes and information search. Further, research findings indicate the moderating role of generational cohort in the use of technologies.

Originality/value

This study provides empirical evidence of the main differences and motivations differences driving technology behaviour of millennials and Generation X individuals.

- Generation X

- Millennials

Calvo-Porral, C. and Pesqueira-Sanchez, R. (2020), "Generational differences in technology behaviour: comparing millennials and Generation X", Kybernetes , Vol. 49 No. 11, pp. 2755-2772. https://doi.org/10.1108/K-09-2019-0598

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Older Adults Perceptions of Technology and Barriers to Interacting with Tablet Computers: A Focus Group Study

Eleftheria vaportzis.

1 Department of Psychology, School of Social Sciences, Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Maria Giatsi Clausen

2 Division of Occupational Therapy and Arts Therapies, School of Health Sciences, Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Alan J. Gow

3 Centre for Cognitive Ageing and Cognitive Epidemiology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Background: New technologies provide opportunities for the delivery of broad, flexible interventions with older adults. Focus groups were conducted to: (1) understand older adults' familiarity with, and barriers to, interacting with new technologies and tablets; and (2) utilize user-engagement in refining an intervention protocol.

Methods: Eighteen older adults (65–76 years old; 83.3% female) who were novice tablet users participated in discussions about their perceptions of and barriers to interacting with tablets. We conducted three separate focus groups and used a generic qualitative design applying thematic analysis to analyse the data. The focus groups explored attitudes toward tablets and technology in general. We also explored the perceived advantages and disadvantages of using tablets, familiarity with, and barriers to interacting with tablets. In two of the focus groups, participants had previous computing experience (e.g., desktop), while in the other, participants had no previous computing experience. None of the participants had any previous experience with tablet computers.

Results: The themes that emerged were related to barriers (i.e., lack of instructions and guidance, lack of knowledge and confidence, health-related barriers, cost); disadvantages and concerns (i.e., too much and too complex technology, feelings of inadequacy, and comparison with younger generations, lack of social interaction and communication, negative features of tablets); advantages (i.e., positive features of tablets, accessing information, willingness to adopt technology); and skepticism about using tablets and technology in general. After brief exposure to tablets, participants emphasized the likelihood of using a tablet in the future.

Conclusions: Our findings suggest that most of our participants were eager to adopt new technology and willing to learn using a tablet. However, they voiced apprehension about lack of, or lack of clarity in, instructions and support. Understanding older adults' perceptions of technology is important to assist with introducing it to this population and maximize the potential of technology to facilitate independent living.

Introduction

Technology now supports or streamlines many day-to-day activities. This continued technological development is occurring alongside the aging of global populations, creating opportunities for technology to assist older people in everyday tasks and activities, such as financial planning and connecting with friends and family. New technology also has the potential to provide timely interventions to assist older adults in keeping healthy and independent for longer (Geraedts et al., 2014 ). Older adults are slower to adopt new technologies than younger adults (Czaja et al., 2006 ), but will do so if those technologies appear to have value, for example in maintaining their quality of life (Heinz et al., 2013 ). To make technology more age-friendly, it is important to understand the advantages and disadvantages that older adults perceive in using it. We therefore explored older adults' familiarity with and barriers to using technology.

Mobile technological devices such as tablet computers (commonly referred to as tablets), a type of portable computer that has a touchscreen, are becoming increasingly popular. The number of adults aged 65–74 years using tablets to go online more than trebled in recent years in the UK, going from 5% in 2012 to 17% in 2013. However, this percentage remains low compared with younger age groups (e.g., 37% of adults aged 25–34 years used tablets to go online in the last 3 months) (Ofcom, 2014a ). Adoption of technology may improve older adults' quality of life, facilitate independent living for longer (Orpwood et al., 2010 ), and bridge the technological gap across generations by teaching older people to use technological devices (Bailey and Ngwenyama, 2010 ). Tablets can offer the same functionality as a normal computer at a smaller, more flexible size and weight. Tablets may also provide a better internet browsing experience compared to mobile phones as they have a larger screen. According to Ofcom ( 2014b ), tablets helped to drive overall internet use in adults over 65 from 33% in 2012 to 42% in 2013. Older adults may prefer tablet technology due to the portability and usability they provide vs. computer technology (e.g., adjustable font or icon size), especially to those who have a wide range of motor and visual abilities (Chan et al., 2016 ). Understanding the barriers to using technology in general and tablets in particular in older adults can provide insights into appropriate ways of introducing tablet technology to this population. This is important as it appears that tablet technology encourages older adults to access the internet. In turn, this may assist in daily activities and decrease isolation, which is more common in older age (Cornwell and Waite, 2009 ). The internet may foster links to friends and family and facilitate essential daily activities, such as shopping and banking (Czaja et al., 2006 ).

Previous studies have explored the perceptions and attitudes of older adults toward new technologies. Heinz et al. ( 2013 ) conducted focus groups with 30 older adults in total (mean age 83), focussing on daily needs and challenges, advantages and disadvantages associated with technology usage, how technology could be helpful, and ways to make technology easier to use. Participants were apparently willing to adopt new technologies when their usefulness and usability surpassed feelings of inadequacy, though some concerns remained over society's overreliance on technology, loss of social contact, and complexity of technological devices. Mitzner et al. ( 2010 ) conducted 18 focus groups with 113 community-dwelling older adults (mean age 73 years). Participants reported using technology at home, at work and for healthcare. Positive reactions to technology included portability and communication, whereas too many options and unsolicited communication were seen as disadvantageous.

The Center for Research and Education on Aging and Technology Enhancement (CREATE) has also reported on the use of technology among community-dwelling adults. Their findings suggested that older adults (60–91 years) were less likely than younger adults to use technology in general, and specifically computers and the internet. Technology adoption was associated with higher cognitive ability, computer self-efficacy and computer anxiety, whereas higher fluid intelligence and crystallized intelligence predicted the use of technology; higher computer anxiety predicted lower use of technology (Czaja et al., 2006 ). An earlier study indicated that older people (60–75 years) perceived less comfort, efficacy and control over computers relative to younger participants, however, direct experience with computers resulted in more positive attitudes (Czaja and Sharit, 1998 ). Alvseike and Brønnick ( 2012 ) reported that cognitive deficits and low self-efficacy associated with older age significantly reduced participants' ability to use technology. Generally, the current literature suggests that although older adults are open to using technology there may be age-related (e.g., cognitive decline) as well as technology-related (e.g., interface usability) barriers.

Tablets offer less complexity compared with other operating systems as they comprise a touch-based interface. For example, Umemuro ( 2004 ) developed an email terminal with a touchscreen and compared it with the same terminal using a standard keyboard and mouse in two groups of Japanese adults (60–76 years old). Participants were required to read and send messages using their assigned terminals. Results suggested that participants using the touchscreen terminal were less anxious compared with those using the standard keyboard terminal. Schneider et al. ( 2008 ) also compared different input devices including a touchscreen with a mouse, or eye-gaze plus keyboard, in sample ranging from 60 to 72. Participants were required to click inside a start stimulus (circle) and then inside a target (square) that appeared on a screen, or to move a stimulus (rectangle) toward a target (another rectangle) on a touchscreen. The authors concluded that the touchscreen input afforded the best performance as reflected by execution time, error rate and subjective evaluation of task difficulty. Interestingly, the older participants (60–72 years) reached a performance level similar to that of younger participants (20–39 years) when using a touchscreen; that is, while they remained slower, this was no longer significantly different. Although the design of applications running on devices is critical, touchscreen interfaces may make it easier for users to complete tasks and contributes to the popularity and success of touchscreen devices (Balagtas-Fernandez et al., 2009 ).

The overall aim of the current study was to build on previous research by investigating the perceptions of, and barriers to, interacting with tablets in healthy older adults who were novice tablet users. We employed focus groups as this methodology offers an open and exploratory way for qualitative data collection (Krueger, 1998 ). We wanted to understand: (a) older adults' attitudes toward technology in general, and tablets in particular; (b) the perceived advantages and disadvantages of using tablets, and how they may be helpful; and (c) familiarity with, and barriers to interacting with tablets. These objectives were conceived so that we might harness user-engagement to refine protocols from previous research in which tablet training has been used as a cognitive intervention (Chan et al., 2016 ), thus directing our future research efforts.

Participants

Potential participants were recruited from the Edinburgh area by contacting clubs for older adults, community centers and email lists using the snowball principle (Goodman, 1961 ). All potential participants provided demographic information by telephone, including that they were free of neurological and psychiatric conditions, and cognitive and motor impairment. Eleven potential participants were excluded at this stage because they did not meet these criteria, and one further participant declined for personal reasons. In total, 18 healthy, community-dwelling older adults between the ages of 65 and 76 years ( M = 71.1; SD = 3.7) agreed to participate in the focus groups. Three focus groups were conducted and each included six participants. All participants were tablet novices, but ranged in their experience with other computing technology (i.e., desktop computers). Those with no previous computing experience were included in one focus group; participants in the two remaining groups all had previous computing experience. The same agenda was used for all groups. Demographic information for the focus group participants is presented in Table Table1 1 .

Demographic characteristics of the participants ( N = 18).

| (%) | |

|---|---|

| Female | 15 (83.3) |

| Male | 3 (16.7) |

| White British | 15 (83.3) |

| White other | 2 (11.1) |

| Did not respond | 1 (5.6) |

| Some high school | 1 (5.6) |

| High school | 4 (22.2) |

| Some college | 6 (33.3) |

| Graduate | 4 (22.2) |

| Post-graduate | 3 (16.7) |

| Alone | 13 (72.2) |

| Partnered | 4 (22.2) |

| Carer | 1 (5.6) |

Percentages may not total 100% due to rounding .

Materials and procedure

We developed focus groups materials based on previous research (Venkatesh et al., 2003 ; Zhou et al., 2014 ; Chan et al., 2016 ). A number of different devices were made available to the participants during the second half of the focus groups to gain feedback from older adults on any likely preferences for size, style, etc., to better direct the selection of the tablet device to be used in a later planned intervention study. We chose the following five touchscreen tablets using independent advice and product reviews at www.which.co.uk : Asus TF103CX (10″, Android), Asus Google Nexus 7 (7″, Android), Samsung Galaxy Tab 3 (8″, Android), Samsung Galaxy Tab 3 (10.1″, Android), and Apple iPad Mini (7.9″, iOS). We covered the brand names/logos on all tablets with masking tape. A previous study investigating text entry on tablets and smartphones in older Chinese adults used four different touch screens: Apple iPod Touch, Dell Streak, Samsung Galaxy Tab and Apple iPad (Zhou et al., 2014 ).

We conducted the focus group sessions between February and March 2015 in a quiet room at Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh. These focus groups were the first stage of a larger study, “Tablet for Healthy Ageing” (Vaportzis et al., 2017 ). The focus group stage was designed to utilize user-engagement to explore older adults' perceptions and attitudes toward tablets and technology in general, and also to refine a proposed intervention protocol using technology with older adults for subsequent stages of the “Tablet for Healthy Ageing.” During the focus groups, participants were specifically asked to provide feedback on the proposed intervention protocol, which referred to themes and activities that might appear during a tablet training course. The group discussions lasted ~2 h, and the same moderator, who was one of the authors of this study (E.V.), conducted all focus groups. Participants were seated around a table with the moderator being seated with them at the table.

Before beginning the focus groups, the moderator reminded participants of the objective of the study, and that the discussions would be used to guide the next stage of the research. Participants gave written informed consent and completed a brief demographics questionnaire reported in Table Table1. 1 . To ensure anonymity, participants' responses could not be linked with participants' identities. Below we present the questions that guided and stimulated the discussion over the first hour.

- Think for a moment about your daily life. What are some of the greatest needs and challenges you have?

- What is technology for you? What does the word “technology” bring to mind?

- Which technologies do you use?

- Given some of the issues that people your age face that we just discussed earlier (such as [examples from earlier conversation]), which technologies do you know about that might be helpful in addressing these problems?

The moderator then pointed toward a selection of tablets, which were arranged on an adjacent table though not switched on, and asked the participants:

- Have you seen a tablet before?

- What are some of the reasons for which you have not used a tablet to date?

- What do you think are the advantages using tablets?

- What do you think are the disadvantages using tablets?

The moderator handed out the tablets. The tablets remained turned off as the main interest at this point was participants' first impressions on the physical aspects of the tablets such as weight and size. Participants took turns to get a feel for all different models. As there were five tablets but six participants, in any given activity two participants shared a device. Different participants paired up for the various tasks to ensure that each participant had the opportunity to complete some of the tasks on their own.

The moderator asked then the following questions:

- What are your initial impressions of the tablets? What is the first thing that comes to your mind?

- - Assisting with everyday living

- - Improving mental abilities

- - Improving general health and wellbeing

After a break, the second hour comprised an interactive session. The moderator gave instructions on how to turn the tablets on, and participants used three applications (apps) in the following order: Google Maps, BBC News, and Chrome browser. We used a brief scenario for each application, and the scenarios were linked to give participants a realistic sense of how people use tablets in their everyday lives. The scenario involved meeting with a friend at the Scottish National Gallery after the focus group. Participants used the Google Maps app to choose their preferred way to get there from Heriot-Watt University. On arriving at the gallery early, the scenario suggested they accessed the BBC News app. They read the news and watched live TV streams. Finally, once their friend arrived, they used the Chrome browser to find out what was on at their preferred cinema.

Then, the moderator asked:

- What are your impressions of the tablet applications that you used?

- What might make it easier to use a tablet?

The moderator handed out printed copies of a tentative intervention programme that would be used in the following stage of the study (Vaportzis et al., 2017 ). The programme included topics that would be covered during the 10-week intervention, including social connectivity and traveling and was based on a previous study (Chan et al., 2016 ). Once participants had enough time to look at the programme, the moderator asked:

- What are your thoughts? What do you think that may or may not work with this programme?

Finally, participants completed a Tablet Experience Questionnaire to rate their experience with the tablets, and give their opinion about the tablets and applications. All focus group sessions were video-recorded and later transcribed verbatim. The moderator did not take notes during the sessions; rather these were transcribed verbatim from the recordings. The full transcripts were then analyzed as detailed below.

This study was approved by the Heriot-Watt University School of Life Sciences Ethics Committee. All subjects gave written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data analysis

Data analysis was first conducted by one of the researchers (E.V.) and subsequently by an independent researcher with experience in qualitative data analysis to increase confirmability (M.G.C.). We carried out inductive thematic analysis as described by Boyatzis ( 1998 ) using NVivo10 software (NVivo, 2012 ). The focus groups transcripts were initially read numerous times. This process of immersion with data is thought to serve as a “preparation” stage before the actual analysis as it allows familiarization with the language and wording used by the participants. Initially, first-order themes were identified within each response of each participant to the questions posed in the focus groups. These themes were either directly related to the study's research questions, or were entirely new topics that emerged from the participant's comments.

In the next stage, these first-order themes were fused or clustered to a second-order series of themes (”higher order” themes or codes) based on the commonality of their meaning. At this stage, themes from the previous stage either expanded to encompass others or had “shrunk” to become more specific. These final themes were more abstract in their meaning than the previous ones and, were the themes to be finally interwoven with the existing literature (e.g., “cost” and “lack of instructions and guidance” were fused under “barriers to using technologies and tablets”). The process described above was iterative as themes evolved and the data better understood. Further reading led to the identification of additional themes, initially not detected.

Each of the researchers individually coded and categorized data from the same focus group to allow triangulation of findings. Data from the other two focus groups were then coded by one of the researchers (E.V.), and were reviewed repeatedly with particular attention to refining the codes by both researchers. Through comparison, the two researchers discussed and agreed on discrete themes. We refined and finalized the codes, resulting in a list of agreed themes.

The analysis of the focus group transcripts revealed an emphasis on the advantages and disadvantages of using technologies in general with a focus on tablet use. The final four themes were: (a) Barriers to using technologies and tablets; (b) disadvantages and concerns about using technologies and tablets; (c) advantages and potential of technologies and tablets; and (d) skepticism and mixed feelings about technology and tablets. The four themes were common to participants that had previous computer experience and participants that had no previous computer experience, though there were some small differences in the subthemes. For example, lack of instructions and guidance was a subtheme that emerged only in the group that had computer experience. The themes are presented in order of their importance determined by frequency and uniqueness. Participants' quotes are presented to illustrate each theme. Group is indicated by a G and participant by a P next to each quote followed by the appropriate number (e.g., G1, P1). To differentiate the quotes provided by gender, those from male participants are denoted with an M. We present first quotes from participants with previous computer experience (G1 and G2), followed by quotes from participants that reported no/minimal computer experience (G3). A summary of the themes and subthemes is presented on Table Table2 2 .

Focus group themes and subthemes.

| Barriers to using technologies and tablets | Lack of instructions and guidance |

| Lack of knowledge and confidence | |

| Health-related barriers | |

| Cost | |

| Disadvantages and concerns about using technologies and tablets | Too much and too complex technology |

| Feelings of inadequacy and comparison with younger generations | |

| Lack of social interaction and communication | |

| Negative features of tablets | |

| Advantages and potential of technologies and tablets | Positive features of tablets |

| Accessing information | |

| Willingness to adopt technology | |

| Skepticism and mixed feelings about technology and tablets |

Barriers to using technologies and tablets

Participants mentioned a number of perceived and actual barriers to using tablets and technology in general. Four subthemes emerged under this theme: lack of instructions and guidance, lack of knowledge and confidence, health-related barriers, and cost.

Lack of instructions and guidance

Participants noted that if there are any instructions, they are too technical.

- G2, P1(M): “The manual is written by the techies. It's not written by [users] and that's probably a big message to send to the manufacturer.”

- G2, P2: “There might be features [on the tablets] there which might help you from a medical point of view if you knew about them. So you want the manual to be written in the so-called dummy style, so that it's very readable and understandable.”

Participants in another group noted:

- G1, P4: “If you're sitting there by yourself trying to read the instructions that would be quite scary.”

- G1, P6: “A little handout with each tablet showing what the keys are for.”

Lack of instructions and guidance was a subtheme that did not emerge in the group that had no computer experience.

Several participants mentioned that when they asked for assistance, other people quickly completed the job for them instead of guiding them.

- G2, P2: “My daughter comes and helps me, but she does [participant makes quick noise]. There you are mother. And I'm going […] and say, what did your fingers do?”

- G2, P3: “I've got a son and I say “How do I do this?”, and he sets it up for me.” A participant with no computer experience also mentioned: “My son is just too fast. He says it's common sense, use your brain, you should know this. They just have no patience […] they expect to tell you once (G3, P3).”

Lack of knowledge and confidence

Participants emphasized their concern and fear of using tablets and technology in general due to lack of knowledge or low confidence, as well as the perceived dangers of technological equipment. One participant said: “But does it get our confidence, the fact that we don't know how to do all these fancy things…I feel a bit inadequate sometimes (G2, P4).” Participants' responses also suggested that they were not aware of differences between different types of technology (e.g., tablets vs. computers). “That's why I'm trying to find out what is the difference between A (tablets), B (computers) and C (smartphones), apart from a bit more this and a bit less of that, there doesn't seem to be any difference [G3, P5(M)].” Another participant expressed fear of using technology: “I'm just frightened in case I go in somewhere and then I can't get out. You know how they talk about the Trojan viruses and all that spyware and all the rest of it? That's what I'm frightened of, especially when you don't know (G3, P6).”

Health-related barriers

Barriers related to a number of health issues that older people are more likely to have were noted, illustrated by the following quote: “Health is an issue. I mean, I'm quite healthy […] but my knees and arthritis. You can't stop these things and they have an impact on you, how you approach things (G1, P3)”. A participant stated: “Wasn't it a controversy when they produced eBooks that some people found they couldn't read it under certain lighting conditions as well as any problems with eyesight? [G1, P5(M)].”

Participants with no computer experience also mentioned health-related issues.

- G3, P1: “I have difficulty reading signs and anything small. So I would automatically go for the biggest tablet.”

- G3, P3: “I don't know if I would be able to use this [tablet] for a long length of time; […] with my [fractured] wrist and fingers I don't know.”

The high price of tablets and other technological equipment was one of the barriers that participants mentioned.

- G2, P2: “There's also the cost, because you've got software here and you've got software on your main machine and that's always going to be updated every so often […].”

- G2, P4: “Cost comes in to it. It's not so bad nowadays, but it came in to it.”

- G2, P1(M): “Often with technology, if it's a low price, you've probably got fewer facilities.” Cost was a subtheme that did not emerge in the group that had no computer experience.

Disadvantages and concerns about using technologies and tablets

Participants noted a number of issues that discouraged them from using tablets and other technology. Four subthemes emerged under this theme: too much and too complex technology, feelings of inadequacy and comparison with younger generations, lack of social interaction and communication, and negative features of tablets.

Too much and too complex technology

Participants felt that there are too many pieces of technology: “You can have too much technology; if you've got a phone and a tablet, and a laptop and a computer, you're swimming about in it [G2, P1(M)].” Participants also expressed preferences for simpler forms of technology: “I just want the simplest, no frills, no bells and whistles [piece of equipment] (G1, P1).” A participant with no computer experience also said: “Is there a very simple tablet, where you can just say I only want my tablet to do that, that and that? I don't want a million opportunities flashing up every time I touch something. It's trying to sell me something I don't want. I just want to be able to do ABCD (G3, P4).”

Feelings of inadequacy and comparison with younger generations

In several cases, participants compared themselves to younger people who appear to know how to use technology from a very young age.

- G1, P1: “My children just look at a piece of equipment and they're off. […] My brain is just not built to deal with half of the technology out there. I wish I was more the other way, I really do, because I am aware of the being left behind I suppose.”

- G1, P4: “I think maybe this is the first generation where the younger people have the advantage over the older people, because they grow up with technology at school.”

A participant in another group also agreed: “A lot of people that [young] age, they seem to pick it up intuitively [G2, P5(M)].”

A feeling of inadequacy compared with younger generations was also reflected in the following quote by a participant with no computer experience: “We are now the children in our children's eyes, I think (G3, P6).” Another participant was skeptical about people's overreliance on technology, and whether this is necessary: “I've been on a train […] and everybody you look at is sitting there with a tablet (G3, P3).”

Lack of social interaction and communication

Participants expressed concern about the lack of social interaction and social skills of future generations. A participant noted: “I think they're [younger people] missing a lot of human interaction, because they are so focused on the screen and machines (G1, P2).” Similarly, a participant with in another group said: “The oddest for me is looking at neighboring tables in a public place and I think ‘Why are you out with this person? (G3, P1)”’ Another participant said: “Well, I take my grandchildren out, if we go for lunch I take their phones off them, because they were sitting at lunch, and you say look, I come down to see you at Christmas, family lunch, take them out, and they all seem to do this all the time. You know, you've been brought up to sit down and talk with your elders and your betters round this table, your mother and your father are there and I'm here, and I've come to see you, so don't sit and play games [G3, P5(M)].

Negative features of tablets

In terms of the perceived disadvantages of using tablets, some participants with computer experience thought that the tablets were quite heavy, for example: “I don't know if I could be bothered carrying that (the tablet) around with me all the time [G2, P5(M)].”

Some found the buttons cumbersome:

- G3, P3: “We press one (button) at the bottom here do we? It would help if they just put a little name.”

- G3, P5(M): “I think the buttons are far too difficult to handle and they should have a label on them saying what they are.”

Advantages and potential of technologies and tablets

Overall, participants rated their tablet experience as positive and most stated that they would be likely to use a tablet in the future. Three subthemes emerged under this theme: positive features of tablets, accessing information, and willingness to adopt technology.

Positive features of tablets

Participants with computer experience were impressed with the screen clarity of the tablets, as the following comment suggests: “It's very clear, it's a nice clear screen, because I thought maybe being so small I would have difficulty reading it, but this will be fine (G1, P3).” They also stressed how important portability and versatility was.

- G2, P2: “One of the advantages […] is how versatile they are. They can play music. […] They take photos […]. They can do anything really, can't they?”

Another participant in the same group said: “My neighbor next door who's in […] the target age group for this project, they've got a PC and they've got this type of device [tablet] in the lounge all the time and is used regularly […] cause I pass the window, I can see them using it, because it's convenient. Don't have to go upstairs to the equipment [G2, P5(M)].”

- G2, P3: “I just had a great granddaughter born on Monday and one of the other grandmothers came along with a tablet and she was taking photos with the tablet. It was tremendous and the quality is really good and that's something that, you know, you can't do on the phone, or you certainly can't do on the laptop.”

Positive features of tablets was a subtheme that did not emerge in the group that had no computer experience.

Accessing information

Participants with computer experience noted that tablets give easy access to information:

- G2, P4: “Information right away. I like that.”

- G2, P3: “I'd know whether the bus is gone or it's coming, that's really important.”

- G2, P5(M): “I see people going on holiday […] using these things [tablets], cause you pull up maps…”

Willingness to adopt technology

Participants expressed interest in learning how to use a tablet as they felt left out.

“I'd really like to be in the modern world and to be able to manage these things and to be able to access more. I just feel very limited in what I'm doing. And I need the courage and to try and trust somebody to give me what I can manage and […] show me how to get in to it (G2, P6).”

Participants in the no computer experience group also stated:

- G3, P6: “I think we're missing out on a lot, because all the information is at hand and we don't know how to collect that information. That's what I personally feel and I want to be able to collate it and just basically know what I'm doing.”

- G3, P5(M): “I just think we're like a forgotten generation, that's what I feel like. You want to go in and you want to be able to talk with your family and your grandchildren and not look vacant when they say, I'm going to do this.”

Skepticism and mixed feelings about technology and tablets

Participants were less in agreement regarding the potential of tablets to improve skills and cognitive abilities. Some participants held that learning to use a tablet could improve various skills and abilities.

- G2, P5(M): “Yeah, it keeps the brain active in one way or another.”

- G2, P4: “For games and that kind of stuff. I'm sure that's why we all do our Sudoku and all these games, things, code words. Yes, because I notice when you stop, you know, on holiday and you haven't access to the paper or whatever, it takes a while to get some of the more complicated words. But, you know, you lose it for a wee while and then you build it up again.”

- G2, P1(M): “Learning any new skill, surely is helping the cognitive function.”

A participant in the group with no computer experience also said: “Oh, I think so, definitely, I do [think that a tablet could be used to improve mental abilities] (G3, P6).” However, others were more skeptical about a tablet's ability to improve older people's skills and abilities as the following quotes by participants with computer experience suggest:

- G1, P4: “But, do you know what, these kind of technologies actually make it harder to focus.”

- G1, P1: “It almost deters you from memory because you've got your calendar on your phone, you don't have to remember any more.” A participant in the group with no computer experience was also skeptical about the ability of a tablet to improve skills and abilities: “What about the reverse of this […] it's stopping you thinking that six sixes are 36 [G2, P1(M)].”

Participants also did not reach consensus about tablet size, as some favored the small tablets due to portability, but others the larger tablets due to the increased screen size.

- G2, P4: “I think with me, it would be the portability of it […]. This is probably slightly too big to go in to my handbag, but the smaller one would.”

- G2, P6: “Size would matter to me as well, but I would go for the big one. And ease of use.”

Similarly, in the group with no computer experience participants said:

- G3, P1: “[I prefer] the smaller one. It's easier to handle. It's lighter”.

- G3, P3:“But the thing about the bigger one is […] if you're looking at something like a film you'll get a bigger picture.”

After completing the focus groups participants rated their tablet experience on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Poor to 5 = Excellent). The majority of participants rated their experience Good to Excellent (94.4%) and stated they would be Likely or Very likely to use a tablet in the future (66.6%). Participants reported that they liked the following: access to information (33.3%), tablet size (33.3%), portability (16.7%), screen clarity (11.1%) and versatility (5.6%). They rated as least desirable: not knowing how to use it (27.8%), small buttons and keyboard (27.8%), sensitivity to touch (27.8%) and size (5.6%); 11.1% reported no negative aspects. Interaction among the overall tablet opinions and the various specific variables (e.g., future tablet usage) are presented in a cross-classification figure (Figure (Figure1 1 ).

Cross-classification of overall tablet opinion.

Our qualitative study explored the acceptability and usability of tablets as a potential tool to improve the health and wellbeing of older adults. Our findings supplement previous studies that investigated perceptions and attitudes of older adults toward new technologies (Mitzner et al., 2010 ). Past research focused on a broad range of technologies, whereas we focused on one specific type of technology (tablets), and therefore incorporated a more hands-on interactive element to the focus groups. Our focus groups considered older adults' views about how they might use tablets as a potential tool to improve their health and wellbeing, in addition to highlighting general attitudes toward technology and tablets, and what might hinder or facilitate using technology and tablets.

The majority of participants enjoyed the tablet experience, and emphasized the likelihood of using a tablet in the future. The positive appraisal of participants' tablet experience was further evidenced by the fact that half of them requested to be included in the following stage of our study. Despite that, the majority of participants lacked confidence in their own abilities to use a tablet. It was also evident from participants' questions that they were unaware of the similarities and differences between different types of technology (e.g., laptop vs. tablet). Overall, participants acknowledged the importance of adopting technology to “move on” and be able to communicate better with younger generations. However, they were concerned about younger people's lack of interaction and communication. Some noted that nowadays people rely too heavily on technology, which is too complicated, and voiced a preference for simpler devices.

Our analyses explored the study's main objectives related to older adults' attitudes toward tablets and technology, the perceived advantages and disadvantages of using tablets, as well as familiarity and barriers to interacting with tablets. In addition to the main objectives of the study, a secondary aim was to refine protocols from previous research in which tablet devices were used as the basis for interventions for cognitive ageing (Chan et al., 2016 ), to replicate that work in subsequent stages of the “Tablet for Healthy Ageing” research programme. Focus group outcomes confirmed that these protocols used previously with a sample of healthy older adults in the USA were appropriate for a UK sample. Therefore, we did not make any major protocol changes for the planned intervention stages (Vaportzis et al., 2017 ).

The themes that emerged in the current study were consistent with the literature. For example, disadvantages and concerns about using technologies and tablets emerged both in our study and Heinz et al. ( 2013 ), although the latter labeled the theme “Frustrations, Limitations, and Usability Concerns.” In both studies participants noted that tablets and technology in general are often overly complicated and mentioned that simplified technology would be preferable. Concerns about society's overreliance on technology and the perceived growing lack of social interaction and contact were also noted in both studies. Common subthemes with Mitzner et al. ( 2010 ) included a fear of using technology, the perception of there being too many options offered by technology, barriers that health issues may impose, as well as the high cost of technological equipment. Interestingly, only participants with previous computer experience brought up the latter in our study. It is possible that cost is not one of the main barriers to using technology for people with less experience; their lack of exposure to technology in general may mean they are less aware of the costs of such devices, or simply that other concerns take priority. For example, Czaja et al. ( 2006 ) reported that higher computer anxiety predicted lower use of technology. Although we did not measure anxiety levels, it may be that for some, a lack of confidence rather than cost of equipment is what presents the primary barrier. Another possibility is that the perceived benefits of using technology may outweigh the cost for participants with no computer experience. This finding is consistent with previous studies suggesting the perception of potential benefits was more indicative of technology acceptance than perception of cost (Melenhorst et al., 2001 ; Mitzner et al., 2010 ). The theory of diffusion of innovations (Rogers, 2010 ) also holds that older adults are less likely to adopt new technologies unless they view clear benefits of using them.

Despite the potential barriers and disadvantages of tablets and technology, our findings were also broadly consistent with past research that highlighted their potential advantages. For example, participants in Mitzner et al. ( 2010 ) and our study mentioned positive features of tablets and technology, including quick access to information. In addition, in line with Heinz et al. ( 2013 ) and Mitzner et al. ( 2010 ) our participants indicated that they were eager to adopt technology. Previous studies reported that older adults may be willing to use new technological devices when their usefulness and usability outweigh self-efficacy feelings (Heinz et al., 2013 ). In addition, it has been suggested that older people with high self-efficacy are less anxious about, and more likely to use, technology in general (Czaja et al., 2006 ; Mitzner et al., 2010 ). Our findings appear to be consistent with the suggestion that if older adults were more confident they would be more likely tablet or technology users.

Tablets appear to be user-friendly as they are less complex than other interfaces and do not require wired infrastructure. However, they require support to be introduced to older people in an appropriate manner, as older people may lack confidence when first using this technology. To a large extent, tablet learning has developed outside of formal education; however, informal learning may not be appropriate for older people who typically have more limited exposure to computer technology. Formal tablet training may introduce technology into older people's lives in an accessible way, and assist them in keeping up-to-date with technological advances and current trends. Czaja et al. ( 2012 ) evaluated a community-based computer and internet training program designed for older adults and concluded that it can be effective in terms of increasing computer and internet skill as well as help older adults become more comfortable with computer technology. Ultimately, older people might enjoy the advantages that new technologies can offer, such as quick access of information and social inclusion (Warschauer, 2004 ; Morris, 2013 ).

Overall, the current results are consistent with the Selection Optimization Compensation (SOC) Theory which postulates that there are three fundamental life management processes: selection (goals), optimization (goal-related means to achieve desired goals) and compensation (reaction to loss in goal-related means to maintain success or desired goals) (Baltes, 1997 ). According to SOC, as people grow older, they allocate more resources toward loss management to be able to maintain their goals, which reflects compensation to maintain stability (Baltes, 1997 ). Although the current study did not directly investigate whether participants selected goals, and whether they compensated to maintain these goals, our participants emphasized the importance of learning new things, and keeping up-to-date with current trends (e.g., “I just think we're like a forgotten generation, that's what I feel like. You want to go in and you want to be able to talk with your family and your grandchildren and not look vacant when they say, I'm going to do this.”).

Participants also showed evidence of optimizing behavior, such as requesting or accepting assistance to use technology to achieve their desired goals (e.g., “I just go to my son or my daughter if I need something that I can't get anywhere else and they'll do it for me”). This example of behavior further supports SOC which posits that older adults require more time, practice and cognitive support to achieve learning gains. In addition, our results are consistent with the Adult Learning Theory (Knowles, 1984 ). One of the principles of this theory is that adults need to be involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction. Our participants expressed frustration when they requested assistance and other people completed the job for them rather than providing guidance. This is relevant to another principle of the Adult Learning Theory in which experience provides the basis for the learning activities. Completing tasks for older adults may not only be a source of frustration for them but represents the loss of an opportunity for them to gain experience and learn a new activity.

Our findings may be used to inform technology developers and manufacturers about tablet refinement, thereby increasing the potential for acceptance and adoption of tablets by older adults. Several tablet features are worth consideration. For example, the buttons and keyboard should be larger with clear indication of their function. The larger tablets that we included weighed over 500 g and were felt to be heavy; therefore, tablet weight appears to be a consideration for older people, and while our findings might suggest not exceeding 500 g, specific product testing with this age group would be justified. Our participants did not reach consensus in terms of size. Some participants noted that the smaller tablets were too small to see the screen, and others that the larger tablets were too large to have on them at all times. Another point for refinement is related to operational guidance. Participants felt that instructions are typically difficult for non-technical people to understand. Unlike other electronic equipment (e.g., digital cameras), instructions are typically not included with tablets. Manufacturers might include hardcopy instructions that clearly explain basic functions of a tablet, such as the location of the on/off button and how this is used. For example, in some cases the power button must be held for a few seconds to turn a tablet off whereas others require a single quick press.

We should point out that the majority of participants were female, and therefore, our findings may not transfer to males. Despite that, the gender imbalance may reflect current societal trends. Previous studies found that males are more likely to use or own technological equipment compared with females (Wilson et al., 2003 ; Pinkard, 2005 ). Therefore, it is likely that fewer males were tablet novices, and therefore, eligible to participate in our study. Survey studies could provide insight into whether the gender imbalance in our study was due to fewer females using tablets than males, or due to other reasons such as females being keener to volunteer for research purposes. Although our sample was small, and predominantly female, the quotes presented suggest that the responses were similar for men and women; while consistent, a larger sample of men would be necessary to more fully compare the similarities and differences by gender. Previous studies have, for example, reported gender differences. Czaja et al. ( 2006 ) found that older women used fewer types of technology, were more anxious and had less positive general attitudes about computers relative to older men. Czaja and Sharit ( 1998 ) reported that women found computers more dehumanizing following task experience; however, women also experienced a greater sense of comfort following task experience compared with men.

The inductive nature of analysis was maintained in the sense that there was genuine interest in the raw data to reveal any themes; however, our engagement with previous research, which we aimed to build upon, led to a familiarization with certain concepts, a “conceptual organization.” This can be congruent with thematic analysis, as suggested by Boyatzis ( 1998 ). Sets of underlying ideas and themes in the relevant literature, such as “challenges” and “barriers” relating to the use of tablets, were carefully recorded, and were brought into the analysis. They were, specifically, used during the process of clustering the subthemes in the later stages of the analysis, serving as a guide for developing “meaningful” higher simple themes. It is therefore the subthemes which appear under the “higher simple” themes which explicate the findings of this study.

Our sample included only young-old (i.e., 65–75 years) individuals. The age range was restricted to help control potential cohort effects, and to be in line with inclusion criteria of the following stage of the study. Moreover, the majority of participants were White British, so our sample lacked ethnic diversity. Despite that our results are comparable to Heinz et al. ( 2013 ) who used a midwestern USA sample, suggesting that our results could be transferred beyond the UK. Nevertheless, certain socio-economic variables, such as education, may be higher in our sample compared to other populations (Anderson et al., 2004 ). Finally, our sample was small and therefore larger studies are needed to be able to generalize these findings to populations.