Developing a Plan of Care for a Patient with Type 2 Diabetes and Hypertension

Write a 3,000 word care study critically examining the needs and evidence-based care for individuals with complex and co-existing health and social care problems in a range of environments, using the NHS as a reference.

Added on 2023-04-23

About This Document

Added on 2023-04-23

End of preview

Want to access all the pages? Upload your documents or become a member.

Decision Making in Complex Chronic Conditions lg ...

Case study on a hypertensive, diabetic obese patient lg ..., nursing diagnosis and medication management for diabetic retinopathy and hypertension lg ..., the opinions of nursing students regarding the .. lg ..., acute care nursing: pathophysiology and management of hypertensive diabetic patient lg ..., healthcare - primary medical diagnoses lg ....

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Dietary and...

Dietary and nutritional approaches for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes

Food for thought, click here to read other articles in this collection.

- Related content

- Peer review

- Nita G Forouhi , professor 1 ,

- Anoop Misra , professor 2 ,

- Viswanathan Mohan , professor 3 ,

- Roy Taylor , professor 4 ,

- William Yancy , director 5 6 7

- 1 MRC Epidemiology Unit, University of Cambridge School of Clinical Medicine, Cambridge, UK

- 2 Fortis-C-DOC Centre of Excellence for Diabetes, Metabolic Diseases and Endocrinology, and National Diabetes, Obesity and Cholesterol Foundation, New Delhi, India

- 3 Dr Mohan’s Diabetes Specialities Centre and Madras Diabetes Research Foundation, Chennai, India

- 4 Magnetic Resonance Centre, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK

- 5 Duke University Diet and Fitness Center, Durham, North Carolina, USA

- 6 Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine, Durham, North Carolina, USA

- 7 Center for Health Services Research in Primary Care, Department of Veterans Affairs, Durham, North Carolina, USA

- Correspondence to: N G Forouhi nita.forouhi{at}mrc-epid.cam.ac.uk

Common ground on dietary approaches for the prevention, management, and potential remission of type 2 diabetes can be found, argue Nita G Forouhi and colleagues

Dietary factors are of paramount importance in the management and prevention of type 2 diabetes. Despite progress in formulating evidence based dietary guidance, controversy and confusion remain. In this article, we examine the evidence for areas of consensus as well as ongoing uncertainty or controversy about dietary guidelines for type 2 diabetes. What is the best dietary approach? Is it possible to achieve remission of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle behaviour changes or is it inevitably a condition causing progressive health decline? We also examine the influence of nutrition transition and population specific factors in the global context and discuss future directions for effective dietary and nutritional approaches to manage type 2 diabetes and their implementation.

Why dietary management matters but is difficult to implement

Diabetes is one of the biggest global public health problems: the prevalence is estimated to increase from 425 million people in 2017 to 629 million by 2045, with linked health, social, and economic costs. 1 Urgent solutions for slowing, or even reversing, this trend are needed, especially from investment in modifiable factors including diet, physical activity, and weight. Diet is a leading contributor to morbidity and mortality worldwide according to the Global Burden of Disease Study carried out in 188 countries. 2 The importance of nutrition in the management and prevention of type 2 diabetes through its effect on weight and metabolic control is clear. However, nutrition is also one of the most controversial and difficult aspects of the management of type 2 diabetes.

The idea of being on a “diet” for a chronic lifelong condition like diabetes is enough to put many people off as knowing what to eat and maintaining an optimal eating pattern are challenging. Medical nutrition therapy was introduced to guide a systematic and evidence based approach to the management of diabetes through diet, and its effectiveness has been demonstrated, 3 but difficulties remain. Although most diabetes guidelines recommend starting pharmacotherapy only after first making nutritional and physical activity lifestyle changes, this is not always followed in practice globally. Most physicians are not trained in nutrition interventions and this is a barrier to counselling patients. 4 5 Moreover, talking to patients about nutrition is time consuming. In many settings, outside of specialised diabetes centres where trained nutritionists/educators are available, advice on nutrition for diabetes is, at best, a printed menu given to the patient. In resource poor settings, when type 2 diabetes is diagnosed, often the patient leaves the clinic with a list of new medications and little else. There is wide variation in the use of dietary modification alone to manage type 2 diabetes: for instance, estimates of fewer than 5-10% of patients with type 2 diabetes in India 6 and 31% in the UK are reported, although patients treated by lifestyle measures may be less closely managed than patients on medication for type 2 diabetes. 7 Although systems are usually in place to record and monitor process measures for diabetes care in medical records, dietary information is often neglected, even though at least modest attention to diet is needed to achieve adequate glycaemic control. Family doctors and hospital clinics should collect this information routinely but how to do this is a challenge. 5 8

Progress has been made in understanding the best dietary advice for diabetes but broader problems exist. For instance, increasing vegetable and fruit intake is recommended by most dietary guidelines but their cost is prohibitively high in many settings: the cost of two servings of fruits and three servings of vegetables a day per individual (to fulfil the “5-a-day” guidance) accounted for 52%, 18%, 16%, and 2% of household income in low, low to middle, upper to middle, and high income countries, respectively. 9 An expensive market of foods labelled for use by people with diabetes also exists, with products often being no healthier, and sometimes less healthy, than regular foods. After new European Union legislation, food regulations in some countries, including the UK, were updated as recently as July 2016 to ban such misleading labels. This is not the case elsewhere, however, and what will happen to such regulation after the UK leaves the European Union is unclear, which highlights the importance of the political environment.

Evidence for current dietary guidelines

In some, mostly developed, countries, dietary guidelines for the management of diabetes have evolved from a focus on a low fat diet to the recognition that more important considerations are macronutrient quality (that is, the type versus the quantity of macronutrient), avoidance of processed foods (particularly processed starches and sugars), and overall dietary patterns. Many systematic reviews and national dietary guidelines have evaluated the evidence for optimal dietary advice, and we will not repeat the evidence review. 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 We focus instead in the following sections on some important principles where broad consensus exists in the scientific and clinical community and highlight areas of uncertainty, but we begin by outlining three underpinning features.

Firstly, an understanding of healthy eating for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes has largely been derived from long term prospective studies and limited evidence from randomised controlled trials in general populations, supplemented by evidence from people with type 2 diabetes. Many published guidelines and reviews have applied grading criteria and this evidence is often of moderate quality in the hierarchy of evidence that places randomised controlled trials at the top. Elsewhere, it is argued that different forms of evidence evaluating consistency across multiple study designs including large population based prospective studies of clinical endpoints, controlled trials of intermediate pathways, and where feasible randomised trials of clinical endpoints should be used collectively for evidence based nutritional guidance. 19

Secondly, it is now recognised that dietary advice for both the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes should converge, and they should not be treated as different entities ( fig 1 ). However, in those with type 2 diabetes, the degree of glycaemic control and type and dose of diabetes medication should be coordinated with dietary intake. 12 With some dietary interventions, such as very low calorie or low carbohydrate diets, people with diabetes would usually stop or reduce their diabetes medication and be monitored closely, as reviewed in a later section.

Dietary advice for different populations for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Thirdly, while recognising the importance of diet for weight management, there is now greater understanding 10 of the multiple pathways through which dietary factors exert health effects through both obesity dependent and obesity independent mechanisms. The influence of diet on weight, glycaemia, and glucose-insulin homeostasis is directly relevant to glycaemic control in diabetes, while other outcomes such as cardiovascular complications are further influenced by the effect of diet on blood lipids, apolipoproteins, blood pressure, endothelial function, thrombosis, coagulation, systemic inflammation, and vascular adhesion. The effect of food and nutrients on the gut microbiome may also be relevant to the pathogenesis of diabetes but further research is needed. Therefore, diet quality and quantity over the longer term are relevant to the prevention and management of diabetes and its complications through a wide range of metabolic and physiological processes.

Areas of consensus in guidelines

Weight management.

Type 2 diabetes is most commonly associated with overweight or obesity and insulin resistance. Therefore, reducing weight and maintaining a healthy weight is a core part of clinical management. Weight loss is also linked to improvements in glycaemia, blood pressure, and lipids and hence can delay or prevent complications, particularly cardiovascular events.

Energy balance

Most guidelines recommend promoting weight loss among overweight or obese individuals by reducing energy intake. Portion control is one strategy to limit energy intake together with a healthy eating pattern that focuses on a diet composed of whole or unprocessed foods combined with physical activity and ongoing support.

Dietary patterns

The evidence points to promoting patterns of food intake that are high in vegetables, fruit, whole grains, legumes, nuts, and dairy products such as yoghurt but with some cautions. Firstly, some dietary approaches (eg, low carbohydrate diets) recommend restricting the intake of fruits, whole grains, and legumes because of their sugar or starch content. For fruit intake, particularly among those with diabetes, opinion is divided among scientists and clinicians (see appendix on bmj.com). Many guidelines continue to recommend fruit, however, on the basis that fructose intake from fruits is preferable to isocaloric intake of sucrose or starch because of the additional micronutrient, phytochemical, and fibre content of fruit. Secondly, despite evidence from randomised controlled trials and prospective studies 10 that nuts may help prevent type 2 diabetes, some (potentially misplaced) concern exists about their high energy content. Further research in people with type 2 diabetes should help to clarify this.

There is also consensus on the benefits of certain named dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes. Expert guidelines also support other healthy eating patterns that take account of local sociocultural factors and personal preferences.

Foods to avoid

Consensus exists on reducing or avoiding the intake of processed red meats, refined grains and sugars (especially sugar sweetened drinks) both for prevention and management of type 2 diabetes, again with some cautions. Firstly, for unprocessed red meat, the evidence of possible harm because of the development of type 2 diabetes is less consistent and of a smaller magnitude. More research is needed on specific benefits or harms in people with type 2 diabetes. Secondly, evidence is increasing on the relevance of carbohydrate quality: that is that whole grains and fibre are better choices than refined grains and that fibre intake should be at least as high in people with type 2 diabetes as recommended for the general population, that diets that have a higher glycaemic index and load are associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes, and that there is a modest glycaemic benefit in replacing foods with higher glycaemic load with foods with low glycaemic load. However, debate continues about the independence of these effects from the intake of dietary fibre. Some evidence exists that consumption of potato and white rice may increase the risk of type 2 diabetes but this is limited and further research is needed.

Moreover, many guidelines also highlight the importance of reducing the intake of in foods high in sodium and trans fat because of the relevance of these specifically for cardiovascular health.

Areas of uncertainty in guidelines

Optimal macronutrient composition.

One of the most contentious issues about the management of type 2 diabetes has been on the best macronutrient composition of the diet. Some guidelines continue to advise macronutrient quantity goals, such as the European or Canadian recommendation of 45–60% of total energy as carbohydrate, 10–20% as protein, and less than 35% as fat, 13 20 or the Indian guidelines that recommend 50-60% energy from carbohydrates, 10-15% from protein, and less than 30% from fat. 21 In contrast, the most recent nutritional guideline from the American Diabetes Association concluded that there is no ideal mix of macronutrients for all people with diabetes and recommended individually tailored goals. 12 Alternatively, a low carbohydrate diet for weight and glycaemic control has gained popularity among some experts, clinicians, and the public (reviewed in a later section). Others conclude that a low carbohydrate diet combined with low saturated fat intake is best. 22

For weight loss, three points are noteworthy when comparing dietary macronutrient composition. Firstly, evidence from trials points to potentially greater benefits from a low carbohydrate than a low fat diet but the difference in weight loss between diets is modest. 23 Secondly, a comparison of named diet programmes with different macronutrient composition highlighted that the critical factor in effectiveness for weight loss was the level of adherence to the diet over time. 24 Thirdly, the quality of the diet in low carbohydrate or low fat diets is important. 25 26

Research to date on weight or metabolic outcomes in diabetes is complicated by the use of different definitions for the different macronutrient approaches. For instance, the definition of a low carbohydrate diet has ranged from 4% of daily energy intake from carbohydrates (promoting nutritional ketosis) to 40%. 15 Similarly, low fat diets have been defined as fat intake less than 30% of daily energy intake or substantially lower. Given these limitations, the best current approach may be an emphasis on the use of individual assessment for dietary advice and a focus on the pattern of eating that most readily allows the individual to limit calorie intake and improve macronutrient quality (such as avoiding refined carbohydrates).

Regular fish intake of at least two servings a week, including one serving of oily fish (eg, salmon, mackerel, and trout) is recommended for cardiovascular risk prevention but fish intake has different associations with the risk of developing type 2 diabetes across the world—an inverse association, no association, and a positive association. 27 It is thought that the type of fish consumed, preparation or cooking practices, and possible contaminants (eg, methyl mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls) vary by geographical location and contributed to this heterogeneity. More research is needed to resolve whether fish intake should be recommended for the prevention of diabetes. However, the current evidence supports an increase in consumption of oily fish for individuals with diabetes because of its beneficial effects on lipoproteins and prevention of coronary heart disease. Most guidelines agree that omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (fish oil) supplementation for cardiovascular prevention in people with diabetes should not be recommended but more research is needed and the results of the ASCEND (A Study of Cardiovascular Events in Diabetes) trial should help to clarify this. 28

Dairy foods are encouraged for the prevention of type 2 diabetes, with more consistent evidence of the benefits of fermented dairy products, such as yoghurt. Similar to population level recommendations about limiting the intake of foods high in saturated fats and replacing them with foods rich in polyunsaturated fat, the current advice for diabetes also favours low fat dairy products but this is debated. More research is needed to resolve this question.

Uncertainty continues about certain plant oils and tropical oils such as coconut or palm oil as evidence from prospective studies or randomised controlled trials on clinical events is sparse or non-existent. However, olive oil, particularly extra virgin olive oil, has been studied in greater detail with evidence of potential benefits for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes 29 and the prevention of cardiovascular disease within the context of a Mediterranean diet 30 (see article in this series on dietary fats). 31

Difficulties in setting guidelines

Where dietary guidelines exist (in many settings there are none, or they are adapted from those in developed countries and therefore may not be applicable to the local situation), they vary substantially in whether they are evidence based or opinion pieces, and updated in line with scientific progress or outdated. Their accessibility—both physical availability (eg, through a website or clinic) and comprehensibility— for patients and healthcare professionals varies. They vary also in scope, content, detail, and emphasis on the importance of individualised dietary advice, areas of controversy, and further research needs. The quality of research that informs dietary guidelines also needs greater investment from the scientific community and funders. Moreover, lack of transparency in the development of guidelines and bias in the primary nutritional studies can undermine the development of reliable dietary guidelines; recommendations for their improvement must be heeded. 32

Reversing type 2 diabetes through diet

Type 2 diabetes was once thought to be irreversible and progressive after diagnosis, but much interest has arisen about the potential for remission. Consensus on the definition of remission is a sign of progress: glucose levels lower than the diagnostic level for diabetes in the absence of medications for hyperglycaemia for a period of time (often proposed to be at least one year). 33 34 However, the predominant role of energy deficit versus macronutrient composition of the diet in achieving remission is still controversial.

Remission through a low calorie energy deficit diet

Although the clinical observation of the lifelong, steadily progressive nature of type 2 diabetes was confirmed by the UK Prospective Diabetes Study, 35 rapid normalisation of fasting plasma glucose after bariatric surgery suggested that deterioration was not inevitable. 36 As the main change was one of sudden calorie restriction, a low calorie diet was used as a tool to study the mechanisms involved. In one study of patients with type 2 diabetes, fasting plasma glucose normalised within seven days of following a low calorie diet. 37 This normalisation through diet occurred despite simultaneous withdrawal of metformin therapy. Gradually over eight weeks, glucose stimulated insulin secretion returned to normal. 37 Was this a consequence of calorie restriction or composition of the diet? To achieve the degree of weight loss obtained (15 kg), about 610 kcal a day was provided—510 kcal as a liquid formula diet and about 100 kcal as non-starchy vegetables. The formula diet consisted of 59 g of carbohydrate (30 g as sugars), 11.4 g of fat, and 41 g of protein, including required vitamins and minerals. This high “sugar” approach to controlling blood glucose may be surprising but the critical aspect is not what is eaten but the gap between energy required and taken in. Because of this deficit, the body must use previously stored energy. Intrahepatic fat is used first, and the 30% decrease in hepatic fat in the first seven days appears sufficient to normalise the insulin sensitivity of the liver. 37 In addition, pancreatic fat content fell over eight weeks and beta cell function improved. This is because insulin secretory function was regained by re-differentiation after fat removal. 38

The permanence of these changes was tested by a nutritional and behavioural approach to achieve long term isocaloric eating after the acute weight loss phase. 39 It was successful in keeping weight steady over the next six months of the study. Calorie restriction was associated with both hepatic and pancreatic fat content remaining at the low levels achieved. The initial remission of type 2 diabetes was closely associated with duration of diabetes, and the individuals with type 2 diabetes of shorter duration who achieved normal levels of blood glucose maintained normal physiology during the six month follow-up period. Recently, 46% of a UK primary care cohort remained free of diabetes at one year during a structured low calorie weight loss programme (the DiRECT trial). 40 These results are convincing, and four years of follow-up are planned.

A common criticism of the energy deficit research has been that very low calorie diets may not be achievable or sustainable. Indeed, adherence to most diets in the longer term is an important challenge. 24 However, Look-AHEAD, the largest randomised study of lifestyle interventions in type 2 diabetes (n=5145), randomised individuals to intensive lifestyle management, including the goal to reduce total calorie intake to 1200-1800 kcal/d through a low fat diet assisted by liquid meal replacements, and this approach achieved greater weight loss and non-diabetic blood glucose levels at year 1 and year 4 in the intervention than the control group. 41

Considerable interest has arisen about whether low calorie diets associated with diabetes remission can also help to prevent diabetic complications. Evidence is sparse because of the lack of long term follow-up studies but the existing research is promising. A return to the non-diabetic state brings an improvement in cardiovascular risk (Q risk decreasing from 19.8% to 5.4%) 39 ; case reports of individuals facing foot amputation record a return to a low risk state over 2-4 years with resolution of painful neuropathy 42 43 ; and retinal complications are unlikely to occur or progress. 44 However, other evidence highlights that worsening of treatable maculopathy or proliferative retinopathy may occur following a sudden fall in plasma glucose levels, 45 46 so retinal imaging in 4-6 months is recommended for individuals with more than minimal retinopathy if following a low calorie remission diet. Annual review is recommended for all those in the post-diabetic state, and a “diabetes in remission” code (C10P) is now available in the UK. 34

Management or remission through a low carbohydrate diet

Before insulin was developed as a therapy, reducing carbohydrate intake was the main treatment for diabetes. 47 48 Carbohydrate restriction for the treatment of type 2 diabetes has been an area of intense interest because, of all the macronutrients, carbohydrates have the greatest effect on blood glucose and insulin levels. 49

In a review by the American Diabetes Association, interventions of low carbohydrate (less than 40% of calories) diets published from 2001 to 2010 were identified. 15 Of 11 trials, eight were randomised and about half reported greater improvement in HbA1c on the low carbohydrate diet than the comparison diet (usually a low fat diet), and a greater reduction in the use of medicines to lower glucose. Notably, calorie reduction coincided with carbohydrate restriction in many of the studies, even though it was not often specified in the dietary counselling. One of the more highly controlled studies was an inpatient feeding study, 50 which reported a decline in mean HbA1c from 7.3% to 6.8% (P=0.006) over just 14 days on a low carbohydrate diet.

For glycaemia, other reviews of evidence from randomised trials on people with type 2 diabetes have varying conclusions. 51 52 53 54 55 56 Some concluded that low carbohydrate diets were superior to other diets for glycaemic control, or that a dose response relationship existed, with stricter low carbohydrate restriction resulting in greater reductions in glycaemia. Others cautioned about short term beneficial effects not being sustained in the longer term, or found no overall advantage over the comparison diet. Narrative reviews have generally been more emphatic on the benefits of low carbohydrate diets, including increased satiety, and highlight the advantages for weight loss and metabolic parameters. 57 58 More recently, a one year clinic based study of the low carbohydrate diet designed to induce nutritional ketosis (usually with carbohydrate intake less than 30 g/d) was effective for weight loss, and for glycaemic control and medication reduction. 59 However, the study was not randomised, treatment intensity differed substantially in the intervention versus usual care groups, and participants were able to select their group.

Concerns about potential detrimental effects on cardiovascular health have been raised as low carbohydrate diets are usually high in dietary fat, including saturated fat. For lipid markers as predictors of future cardiovascular events, several studies found greater improvements in high density lipoprotein cholesterol and triglycerides with no relative worsening of low density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients with type 2 diabetes following carbohydrate restriction, 15 with similar conclusions in non-diabetic populations. 57 60 61 62 Low density lipoprotein cholesterol tends to decline more, however, in a low fat comparison diet 61 63 and although low density lipoprotein cholesterol may not worsen with a low carbohydrate diet 63 in the short term, the longer term effects are unclear. Evidence shows that low carbohydrate intake can lower the more atherogenic small, dense low density lipoprotein particles. 57 64 Because some individuals may experience an increase in serum low density lipoprotein cholesterol when following a low carbohydrate diet high in saturated fat, monitoring is important.

Another concern is the effect of the potentially higher protein content of low carbohydrate diets on renal function. Evidence from patients with type 2 diabetes with normal baseline renal function and from individuals without diabetes and with normal or mildly impaired renal function has not shown worsening renal function at one or up to two years of follow-up, respectively. 22 65 66 67 Research in patients with more severely impaired renal function, with or without diabetes, has not been reported to our knowledge. Other potential side effects of a very low carbohydrate diet include headache, fatigue, and muscle cramping but these side effects can be avoided by adequate fluid and sodium intake, particularly in the first week or two after starting the diet when diuresis is greatest. Concern about urinary calcium loss and a possible contribution to increased future risk of kidney stones or osteoporosis 68 have not been verified 69 but evidence is sparse and warrants further investigation. The long term effects on cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes need further evaluation.

Given the hypoglycaemic effect of carbohydrate restriction, patients with diabetes who adopt low carbohydrate diets and their clinicians must understand how to avoid hypoglycaemia by appropriately reducing glucose lowering medications. Finally, low carbohydrate diets can restrict whole grain intake and although some low carbohydrate foods can provide the fibre and micronutrients contained in grains, it may require greater effort to incorporate such foods. This has led some experts to emphasise restricting refined starches and sugars but retaining whole grains.

Nutrition transition and population specific factors

Several countries in sub-Saharan Africa, South America, and Asia (eg, India and China) have undergone rapid nutrition transition in the past two decades. These changes have paralleled economic growth, foreign investment in the fast food industry, urbanisation, direct-to-consumer marketing of foods high in calories, sale of ultraprocessed foods, and as a result, lower consumption of traditional diets. The effect of these factors on nutrition have led to obesity and type 2 diabetes on the one hand, and co-existing undernutrition and micronutrient deficiencies on the other.

Dietary shifts in low and middle income countries have been stark: in India, these include a substantial increase in fat intake in the setting of an already high carbohydrate intake, with a slight increase in total energy and protein, 70 and a decreasing intake of coarse cereals, pulses, fruits, and vegetables 71 ; in China, animal protein and fat as a percentage of energy has also increased, while cereal intake has decreased. 72 An almost universal increase in the intake of caloric beverages has also occurred, with sugar sweetened soda drinks being the main beverage contributing to energy intake, for example among adults and children in Mexico, 73 or the substantial rise in China in sales of sugar sweetened drinks from 10.2 L per capita in 1998 to 55.0 L per capita in 2012. 74 The movement of populations from rural to urban areas within a country may also be linked with shifts in diets to more unhealthy patterns, 75 while acculturation of immigrant populations into their host countries also results in dietary shifts. 76

In some populations, such as South Asians, rice and wheat flour bread are staple foods, with a related high carbohydrate intake (60-70% of calories). 77 Although time trends show that intake of carbohydrate has decreased among South Asian Indians, the quality of carbohydrates has shifted towards use of refined carbohydrates. 71 The use of oils and traditional cooking practices also have specific patterns in different populations. For instance, in India, the import and consumption of palm oil, often incorporated in the popular oil vanaspati (partially hydrogenated vegetable oil, high in trans fats), is high. 78 Moreover, the traditional Indian cooking practice of frying at high temperatures and re-heating increases trans fatty acids in oils. 79 Such oils are low cost, readily available, and have a long shelf life, and thus are more attractive to people from the middle and low socioeconomic strata but their long term effects on type 2 diabetes are unknown.

Despite the nutrition transition being linked to an increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, obesity and other non-communicable diseases, strong measures to limit harmful foods are not in place in many countries. Regulatory frameworks including fiscal policies such as taxation for sugar sweetened beverages need to be strengthened to be effective and other preventive interventions need to be properly implemented. Efforts to control trans fatty acids in foods have gained momentum but are largely confined to developed countries. To reduce consumption in low and middle income countries will require both stringent regulations and the availability and development of alternative choices of healthy and low cost oils, ready made food products, and consumer education. 80 The need for nutritional labelling is important but understanding nutrition labels is a problem in populations with low literacy or nutrition awareness, which highlights the need for educational activities and simpler forms of labelling. The role of dietary/nutritional factors in the predisposition of some ethnic groups to developing type 2 diabetes at substantially lower levels of obesity than European populations 81 is poorly researched and needs investigation.

Despite the challenges of nutritional research, considerable progress has been made in formulating evidence based dietary guidance and some common principles can be agreed that should be helpful to clinicians, patients, and the public. Several areas of uncertainty and controversy remain and further research is needed to resolve these. While adherence to dietary advice is an important challenge, weight management is still a cornerstone in diabetes management, supplemented with new developments, including the potential for the remission of type 2 diabetes through diet.

Future directions

Nutritional research is difficult. Although much progress has been made to improve evidence based dietary guidelines, more investment is needed in good quality research with a greater focus on overcoming the limitations of existing research. Experts should also strive to build consensus using research evidence based on a combination of different study designs, including randomised experiments and prospective observational studies

High quality research is needed that compares calorie restriction and carbohydrate restriction to assess effectiveness and feasibility in the long term. Consensus is needed on definitions of low carbohydrate nutrition. Use of the findings must take account of individual preferences, whole diets, and eating patterns

Further research is needed to resolve areas of uncertainty about dietary advice in diabetes, including the role of nuts, fruits, legumes, fish, plant oils, low fat versus high fat dairy, and diet quantity and quality

Given recent widespread recommendations (such as from the World Health Organization 82 and the UK Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition 83 ) to reduce free sugars to under 10% or even 5% of total energy intake in the general population and to avoid sugar sweetened drinks, we need targeted research on the effect of non-nutritive sweeteners on health outcomes in people with diabetes and in the whole population

Most dietary guidelines are derived from evidence from Western countries. Research is needed to better understand the specific aetiological factors that link diet/nutrition and diabetes and its complications in different regions and different ethnic groups. This requires investment in developing prospective cohorts and building capacity to undertake research in low and middle income settings and in immigrant ethnic groups. Up-to-date, evidence based dietary guidelines are needed that are locally relevant and readily accessible to healthcare professionals, patients, and the public in different regions of the world. Greater understanding is also needed about the dietary determinants of type 2 diabetes and its complications at younger ages and in those with lower body mass index in some ethnic groups

We need investment in medical education to train medical students and physicians in lifestyle interventions, including incorporating nutrition education in medical curricula

Individual, collective, and upstream factors are important. Issuing dietary guidance does not ensure its adoption or implementation. Research is needed to understand the individual and societal drivers of and barriers to healthy eating. Educating and empowering individuals to make better dietary choices is an important strategy; in particular, the social aspects of eating need attention as most people eat in family or social groups and counselling needs to take this into account. Equally important is tackling the wider determinants of individual behaviour—the “foodscape”, sociocultural and political factors, globalisation, and nutrition transition

Key messages

Considerable evidence supports a common set of dietary approaches for the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes, but uncertainties remain

Weight management is a cornerstone of metabolic health but diet quality is also important

Low carbohydrate diets as the preferred choice in type 2 diabetes is controversial. Some guidelines maintain that no single ideal percentage distribution of calories from different macronutrients (carbohydrates, fat, or protein) exists, but there are calls to review this in light of emerging evidence on the potential benefits of low carbohydrate diets for weight management and glycaemic control

The quality of carbohydrates such as refined versus whole grain sources is important and should not get lost in the debate on quantity

Recognition is increasing that the focus of dietary advice should be on foods and healthy eating patterns rather than on nutrients. Evidence supports avoiding processed foods, refined grains, processed red meats, and sugar sweetened drinks and promoting the intake of fibre, vegetables, and yoghurt. Dietary advice should be individually tailored and take into account personal, cultural, and social factors

An exciting recent development is the understanding that type 2 diabetes does not have to be a progressive condition but instead there is potential for remission with dietary intervention

Acknowledgments

We thank Sue Brown as a patient representative of Diabetes UK for her helpful comments and insight into this article.

Contributors and sources: The authors have experience and research interests in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes (NGF, AM, VM, RT, WY), in guideline development (NGF, AM, VM, WY), and in nutritional epidemiology (NGF, VM). Sources of information for this article included published dietary guidelines or medical nutrition therapy guidelines for diabetes, and systematic reviews and primary research articles based on randomised clinical trials or prospective observational studies. All authors contributed to drafting this manuscript, with NGF taking a lead role and she is also the guarantor of the manuscript. All authors gave intellectual input to improve the manuscript and have read and approved the final version.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests and declare the following: NGF receives funding from the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit (MC_UU_12015/5). NGF is a member (unpaid) of the Joint SACN/NHS-England/Diabetes-UK Working Group to review the evidence on lower carbohydrate diets compared with current government advice for adults with type 2 diabetes and is a member (unpaid) of ILSI-Europe Qualitative Fat Intake Task Force Expert Group on update on health effects of different saturated fats. AM received honorarium and research funding from Herbalife and Almond Board of California. VM has received funding from Abbott Health Care for meal replacement studies, the Cashew Export Promotion Council of India, and the Almond Board of California for studies on nuts. RT has received funding from Diabetes UK for the Diabetes Remission Clinical Trial and he is a member (unpaid) of the Joint SACN/NHS-England/Diabetes-UK Working Group to review the evidence on lower carbohydrate diets compared to current government advice for adults with type 2 diabetes. WY has received funding from the Veterans Affairs for research projects examining a low carbohydrate diet in patients with diabetes.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned, externally peer reviewed

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ . Open access fees for the series were funded by Swiss Re, which had no input in to the commissioning or peer review of the articles. The BMJ thanks the series advisers, Nita Forouhi and Dariush Mozaffarian, for valuable advice and guiding selection of topics in the series.

This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

- International Diabetes Federation

- Forouzanfar MH ,

- Alexander L ,

- Anderson HR ,

- GBD 2013 Risk Factors Collaborators

- Pastors JG ,

- Warshaw H ,

- DiabCare India 2011 Study Group

- Hippisley-Cox J ,

- England CY ,

- Andrews RC ,

- Thompson JL

- Mozaffarian D

- Boucher JL ,

- Cypress M ,

- American Diabetes Association

- Dworatzek PD ,

- Gougeon R ,

- Sievenpiper JL ,

- Williams SL ,

- Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee

- English P ,

- Wheeler ML ,

- Dunbar SA ,

- Jaacks LM ,

- Diabetes UK Nutrition Working Group

- MacLeod J ,

- Schwingshackl L ,

- Hoffmann G ,

- Lampousi AM ,

- Mozaffarian D ,

- De Leeuw I ,

- Hermansen K ,

- Diabetes and Nutrition Study Group (DNSG) of the European Association

- National Dietary Guidelines Consensus Group

- Luscombe-Marsh ND ,

- Thompson CH ,

- Tobias DK ,

- Manson JE ,

- Ludwig DS ,

- Willett W ,

- Johnston BC ,

- Kanters S ,

- Bandayrel K ,

- Gardner CD ,

- Bersamin A ,

- Trepanowski JF ,

- Del Gobbo LC ,

- Di Giuseppe D ,

- Forouhi NG ,

- ASCEND Study Collaborative Group

- Portillo MP ,

- Romaguera D ,

- Estruch R ,

- Salas-Salvadó J ,

- PREDIMED Study Investigators

- Krauss RM ,

- Cefalu WT ,

- McCombie L ,

- Turner RC ,

- Holman RR ,

- UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group

- Guidone C ,

- Valera-Mora E ,

- Hollingsworth KG ,

- Aribisala BS ,

- Mathers JC ,

- Al-Mrabeh A ,

- Leslie WS ,

- Barnes AC ,

- Wagenknecht LE ,

- Look AHEAD Research Group

- Whittington J

- Pearce IA ,

- The Kroc Collaborative Study Group

- Westman EC ,

- Yancy WS Jr . ,

- Humphreys M

- Bisschop PH ,

- De Sain-Van Der Velden MG ,

- Stellaard F ,

- Sargrad K ,

- Mozzoli M ,

- van Wyk HJ ,

- Snorgaard O ,

- Poulsen GM ,

- Andersen HK ,

- Graves DE ,

- Craven TE ,

- Lipkin EW ,

- Margolis KL

- Chaimani A ,

- Schwedhelm C ,

- Noakes TD ,

- Feinman RD ,

- Pogozelski WK ,

- Hallberg SJ ,

- McKenzie AL ,

- Williams PT ,

- de Melo IS ,

- de Oliveira SL ,

- da Rocha Ataide T

- Mansoor N ,

- Vinknes KJ ,

- Veierød MB ,

- Retterstøl K

- Santos FL ,

- Esteves SS ,

- da Costa Pereira A ,

- Sharman MJ ,

- Forsythe CE

- Friedman AN ,

- Foster GD ,

- Jesudason DR ,

- Pedersen E ,

- Brinkworth GD ,

- Buckley JD ,

- Sakhaee K ,

- Brinkley L ,

- Wycherley TP ,

- Singhal N ,

- Sivakumar B ,

- Jaiswal A ,

- Piernas C ,

- Barquera S ,

- Rivera JA ,

- Ebrahim S ,

- De Stavola B ,

- Holmboe-Ottesen G ,

- Dehghan M ,

- Rangarajan S ,

- Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study investigators

- Bhardwaj S ,

- Ghosh-Jerath S

- Godsland IF ,

- Hughes AD ,

- Chaturvedi N ,

- ↵ World Health Organization. Sugars intake for adults and children. Guideline. WHO, 2015. http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guidelines/sugars_intake/en/

- ↵ Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition. SACN Carbohydrates and Health Report. Public Health England. London, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-carbohydrates-and-health-report

Improving Diabetes Control in a Medicaid Managed Care Population With Complex Needs

A primary care-based integrated care team — including a community health worker (CHW), registered nurse (RN), certified diabetes care and education specialist (CDCES)/registered dietician (RD) and behavioral health counselor — supports patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes in reducing A1c levels.

Unmet social and behavioral health needs can exacerbate risk factors related to uncontrolled diabetes, a condition that disproportionately impacts communities of color and people with lower incomes.

Vayu Health, a California-based nonprofit organization, partnered with Health Net, a Medicaid managed care plan, and Ampla Health, a federally qualified health center, to improve diabetes management among a subset of Health Net’s Medicaid members. Together, the organizations implemented a primary care-based intervention offering integrated care to patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes and an A1c ≥ 9%. This involved connecting patients to an interdisciplinary care team, which included an RN, a CHW embedded within the primary care clinic, and a CDCES/RD and behavioral health counselor who each met with patients virtually. The team worked closely with patients to develop personalized care plans focused on improving glycemic control and addressing other underlying health, behavioral health, and social needs.

The researchers compared outcomes for 51 program-enrolled patients with a comparison group of 477 patients, and found that post-enrollment average monthly A1c among program patients was 0.699 lower than the comparison group. Additionally, one-year post-enrollment, the study found a significant decrease in disparities in A1c control between Hispanic and non-Hispanic program patients.

Despite limitations, such as a small sample size and limited control for confounding variables, this research provides promising evidence consistent with a substantial body of literature demonstrating the benefits of integrated care across patient outcomes. The application of this care model to diabetes management is particularly notable given the condition's widespread prevalence and its disproportionate impact across race, class, and income levels. The program also underscores the potential for cross-sector partnerships in developing innovative care models, with the payer, provider, and a community-based nonprofit each playing crucial roles in the implementation of this program.

Substance Use Disorders and Diabetes Care: Lessons From New York Health Homes

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Case Presentation

Suggested readings, case study: a patient with type 2 diabetes working with an advanced practice pharmacist to address interacting comorbidities.

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

Peggy Yarborough; Case Study: A Patient With Type 2 Diabetes Working With an Advanced Practice Pharmacist to Address Interacting Comorbidities. Diabetes Spectr 1 January 2003; 16 (1): 41–48. https://doi.org/10.2337/diaspect.16.1.41

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Advanced practice pharmacists in the field of diabetes work collaboratively with patients’ medical providers, often in primary care settings or in close proximity to the providers’ practices. They help to integrate the pharmaceutical, medical, education/ counseling, and direct patient care activities necessary to meet patients’ individual self-management and diabetes care needs.

Patient education and self-management behavioral change are underpinnings of pharmaceutical care, and not only as they directly relate to the use of medications. Pharmacists, especially those who are certified diabetes educators (CDEs), frequently provide diabetes patients with education not only on medications, but also on the overall disease state, nutrition, physical activity, decision-making skills, psychosocial adaptation, complication prevention, goal setting, barrier resolution, and cost issues.

In addition to these substantial education responsibilities, advanced practice pharmacists who are Board Certified–Advanced Diabetes Managers (BC-ADMs) play an expanded role that encompasses disease state management. This includes performing clinical assessments and limited physical examinations; recognizing the need for additional care; making referrals as needed; ordering and interpreting specific laboratory tests; integrating their pharmacy patient care plans into patients’ total medical care plans; and entering notes on patient charts or carrying out other forms of written communication with patients’ medical care providers. Depending on state regulations and physician-based protocols, some advanced practice pharmacists can prescribe and adjust medications independently or after consultation with prescribing clinicians.

The clinical activities of BC-ADM pharmacists are not carried out independent of referring, collaborative practitioners. Rather, they are complementary to and serve to enhance the diagnostic, complex physical assessment, and management skills of medical providers.

The following case study illustrates the pharmacotherapeutic challenges of diabetes with other comorbidities, which can lead to potential drug-drug and drug-disease interactions. Although it does not offer detailed solutions to such problems, this case does describe the process of patient care and problem resolution as approached by advanced practice pharmacists.

B.L. is a 58-year-old white woman who has been referred to the pharmacist clinician for pharmacotherapy assessment and diabetes management. Her multiple medical conditions include type 2 diabetes diagnosed in 1995, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, asthma, coronary artery disease, persistent peripheral edema, and longstanding musculoskeletal pain secondary to a motor vehicle accident. Her medical history includes atrial fibrillation with cardioversion, anemia, knee replacement, and multiple emergency room (ER) admissions for asthma.

B.L.’s diabetes is currently being treated with a premixed preparation of 75% insulin lispro protamine suspension with 25% insulin lispro preparation (Humalog 75/25), 33 units before breakfast and 23 units before supper. She says she occasionally “takes a little more” insulin when she notes high blood glucose readings, but she has not been instructed on the use of an insulin adjustment algorithm.

Her other routine medications include the fluticasone metered dose inhaler (Flovent MDI), two puffs twice a day; salmeterol MDI (Serevent MDI), two puffs twice a day; naproxen (Naprosyn), 375 mg twice a day; enteric-coated aspirin, 325 mg daily; rosiglitazone (Avandia), 4 mg daily; furosemide (Lasix), 80 mg every morning; diltiazem (Cardizem CD), 180 mg daily (per cardiologist consult); lanoxin (Digoxin), 0.25 mg daily (per cardiologist consult); potassium chloride, 20 mEq daily; and fluvastatin (Lescol), 20 mg at bedtime. Medications she has been prescribed to take “as needed” include sublingual nitroglycerin for chest pain (has not been needed in the past month); furosemide, additional 40 mg later in the day if needed for swelling (on most days the additional dose is needed); and albuterol MDI (Proventil, Ventolin), two to four puffs every 4–6 hours for shortness of breath. She denies use of nicotine, alcohol, or recreational drugs; has no known drug allergies; and is up to date on her immunizations.

B.L.’s chief complaint now is increasing exacerbations of asthma and the need for prednisone tapers. She reports that during her last round of prednisone therapy, her blood glucose readings increased to the range of 300–400 mg/dl despite large decreases in her carbohydrate intake. She reports that she increases the frequency of her fluticasone MDI, salmeterol MDI, and albuterol MDI to four to five times/day when she has a flare-up. However, her husband has been out of work for more than a year, and their only source of income is her Social Security check. Therefore, she has been unable to purchase the fluticasone or salmeterol and so has only been taking prednisone and albuterol for recent acute asthma exacerbations.

B.L. reports eating three meals a day with a snack between supper and bedtime. Her largest meal is supper. She states that she counts her carbohydrate servings at each meal and is “watching what she eats.” She has not been able to exercise routinely for several weeks because of bad weather and her asthma.

The memory printout from her blood glucose meter for the past 30 days shows a total of 53 tests with a mean blood glucose of 241 mg/dl (SD 74). With a premeal glucose target set at 70–140 mg/dl, there were no readings below target, 8% within target, and 91% above target. By comparison, her results from the same month 1 year ago averaged 112 mg/dl, with a high of 146 mg/dl and a low of 78 mg/dl.

Physical Exam

B.L. is well-appearing but obese and is in no acute distress. A limited physical exam reveals:

Weight: 302 lb; height 5′1″

Blood pressure: 130/78 mmHg using a large adult cuff

Pulse 88 bpm; respirations 22 per minute

Lungs: clear to auscultation bilaterally without wheezing, rales, or rhonchi

Lower extremities +1 pitting edema bilaterally; pulses good

B.L. reports that on the days her feet swell the most, she is active and in an upright position throughout the day. Swelling worsens throughout the day, but by the next morning they are “skinny again.” She states that she makes the decision to take an extra furosemide tablet if her swelling is excessive and painful around lunch time; taking the diuretic later in the day prevents her from sleeping because of nocturnal urination.

Lab Results

For the sake of brevity, only abnormal or relevant labs within the past year are listed below.

Hemoglobin A 1c (A1C) measured 6 months ago: 7.0% (normal range: <5.9%; target: <7%)

Creatinine: 0.7 mg/dl (normal range: 0.7–1.4 mg/dl)

Blood urea nitrogen: 16 mg/dl (normal range: 7–21 mg/dl)

Sodium: 140 mEq/l (normal range: 135–145 mEq/l)

Potassium: 3.4 mg/dl (normal range: 3.5–5.3 mg/dl)

Calcium: 8.2 mg/dl (normal range: 8.3–10.2 mg/dl)

Lipid panel

• Total cholesterol: 211 mg/dl (normal range <200 mg/dl)

• HDL cholesterol: 52 mg/dl (normal range: 35–86 mg/dl; target: >55 mg/dl, female)

• LDL cholesterol (calculated): 128 mg/dl (normal range: <130 mg/dl; target: <100 mg/dl) Initial LDL was 164 mg/dl.

• Triglycerides: 154 mg/dl (normal range: <150 mg/dl; target: <150 mg/dl)

Liver function panel: within normal limits

Urinary albumin: <30 μg/mg (normal range: <30 μg/mg)

Poorly controlled, severe, persistent asthma

Diabetes; control recently worsened by asthma exacerbations and treatment

Dyslipidemia, elevated LDL cholesterol despite statin therapy

Persistent lower-extremity edema despite diuretic therapy

Hypokalemia, most likely drug-induced

Hypertension JNC-VI Risk Group C, blood pressure within target and stable

Coronary artery disease, stable

Obesity, stable

Chronic pain secondary to previous injury, stable

Status post–atrial fibrillation with cardioversion

Status post–knee replacement

Financial constraints affecting medication behaviors

Insufficient patient education regarding purposes and role of specific medications

Wellness, preventive, and routine monitoring issues: calcium/vitamin D supplement, magnesium supplement, depression screening, osteoporosis screening, dosage for daily aspirin

Strand et al. 1 proposed a systematic method for evaluation of and intervention for a patient’s pharmacotherapy, using a process called the Pharmacist’s Work-Up of Drug Therapy (PWDT). The PWDT has been modified by subsequent authors, 2 – 4 but the process remains grounded in the following five questions:

What are reasonable outcomes for this patient?

Based on current guidelines and literature, pharmacology, and pathophysiology, what therapeutic endpoints would be needed to achieve these outcomes?

Are there potential medication-related problems that prevent these endpoints from being achieved?

What patient self-care behaviors and medication changes are needed to address the medication-related problems? What patient education interventions are needed to enhance achievement of these changes?

What monitoring parameters are needed to verify achievement of goals and detect side effects and toxicity, and how often should these parameters be monitored?

Outcomes and Endpoints

Clinical outcomes are distinctly different from therapeutic or interventional endpoints. The former refers to the impact of treatment on patients’ overall medical status and quality of life and should emphasize patient-oriented evidence that matters (POEMs) rather than disease-oriented evidence (DOEs).

Therapeutic endpoints include the anticipated and desired clinical effects from drug therapy that are expected, ultimately, to achieve the desired outcome(s). As such, therapeutic endpoints are used as surrogate markers for achievement of outcomes. Commonly, more than one endpoint will be needed to achieve an outcome. For example, near-normal glycemic control and normalization of blood pressure (endpoints) would be necessary to significantly reduce the risk of end-stage renal disease (outcome).

Therapeutic endpoints should be specific, measurable, and achievable within a short period of time. Achievement of clinical outcomes usually cannot be determined except by long-term observation or retrospective analysis.

Outcomes and endpoints for any given patient should be determined collaboratively between patient and provider before selecting or initiating pharmacotherapy or nonpharmacological interventions. Taking the time to identify these components up front (and periodically revise them later on) helps ensure that subsequent medications or strategies are appropriately directed. It further ensures a common vision and commitment for ongoing patient care and self-management among the care team (including the patient), thus maximizing the potential for optimal disease control and patient satisfaction.

The outcomes and endpoints for a patient such as B.L. are numerous and obviously would not be addressed or attained in a single session. Therefore, after desired outcomes and endpoints are determined, they should be prioritized according to medical urgency and patient preference. Implementation and goal setting related to these priorities can then be undertaken, thus establishing a treatment plan for the eventual attainment of the full list.

During ongoing and follow-up visits, this care plan should be reviewed and modified as indicated by changes in patient status, preferences, and medical findings. Examples of desired outcomes and endpoints for B.L. are given in Tables 1 and 2 . For the sake of brevity, these tables are not intended to be inclusive.

Medication-Related Problems and Proposed Interventions

With agreement between patient and clinician concerning desired outcomes and endpoints, the next logical step is to evaluate whether the current treatment plan is likely to achieve those goals, or, if treatment is to be initiated, which therapies or interventions should be selected.

According to Strand et al., 1 a medication-related problem is any aspect of a patient’s drug therapy that is interfering with a desired, positive patient (therapeutic) outcome or endpoint. The PWDT proposes a systematic and comprehensive method to identify, resolve, or prevent medication-related problems based on the following major categories:

No indication for a current drug

Indication for a drug (or device or intervention) but none prescribed

Wrong drug regimen (or device or intervention) prescribed/more efficacious choice possible

Too much of the correct drug

Too little of the correct drug

Adverse drug reaction/drug allergy

Drug-drug, drug-disease, drug-food interactions

Patient not receiving a prescribed drug

Routine monitoring (labs, screenings, exams) missing

Other problems, such as potential for overlap of adverse effects

Once problems are identified, resolutions must be developed, prioritized, and implemented. Patient or caregiver input is especially helpful at this stage because the individual can describe subjective as well as objective data, expectations or concerns that may be affecting drug therapy, and deficits in drug knowledge, understanding, or administration.

Resolutions may result from numerous strategies, including dose alteration, addition or discontinuation of medication, adjunct medications, regimen adjustment, complementary therapies, instruction on medication administration or devices, disease or medication education, development of “cues” as compliance reminders (e.g., pill boxes), and identification of ways to avoid, detect, or manage side effects or toxicities. Needless to say, the involvement of patients and family or caregivers is critical for successful implementation of most resolution strategies and for optimal disease management.

Because of the extent of B.L.’s medication-related problems and potential interventions ( Tables 3 and 4 ), it was agreed to tackle first her asthma exacerbations and high blood glucose levels. To this end, B.L. was counseled about the role of maintenance asthma medications versus rescue drugs. The root of her confusion between these agents was easy to understand—because the prednisone and fluticasone were both called steroids, it seemed likely that the tablets were a cheaper and easier way to take the medicine. Likewise, since albuterol and salmeterol were both called bronchodilators, it seemed that the albuterol was the cheaper way to take the medicine.

Having grasped the concept of asthma prevention, she was willing to convert to a product combining fluticasone and salmeterol (Advair Diskus) for maintenance/prevention and to reserve the albuterol for quick relief of acute symptoms. Free samples of the new product were dispensed, and B.L. was enrolled in the manufacturer’s indigent drug program for subsequent supplies.

She was further instructed on the use of a peak flow meter and advised to monitor her readings and symptoms. At the next visit, these data will be used to determine her maximal expiratory effort (“personal best”) and to construct an asthma action plan.

B.L.’s insulin was changed to a basal-based regimen utilizing bedtime glargine (Lantus) insulin and premeal lispro (Humalog) insulin. Education was provided on this dosing concept. She and the pharmacist discussed how this regimen can give greater flexibility in dosing, especially for responding to changes in diet, exercise, and disease exacerbations or medications. She was also given an initial supplementary adjustment algorithm (sliding scale) to correct for any temporary elevation of blood glucose. She agreed to test four times daily and to record her blood glucose results, carbohydrate intake, and insulin doses. At the next visit, these data will be used to modify the adjustment algorithm and to construct a prospective algorithm for matching premeal bolus insulin to the anticipated carbohydrate intake (insulin-to-carbohydrate ratio).

The final interventions for this visit were to increase the dose of potassium chloride and change the fluvastatin to atorvastatin (Lipitor) to further reduce B.L.’s LDL cholesterol. Medication education for atorvastatin was provided, and patient questions were answered.

Other medication-related problems and interventions identified for B.L. are listed and briefly discussed in Tables 3 and 4 . For the sake of brevity, these lists are not inclusive nor are all pharmacotherapy issues discussed.

Monitoring for Effectiveness, Side Effects, and Toxicity

The last step in the PWDT process is to develop a plan to evaluate the patient’s progress in attaining desired outcomes, therapeutic endpoints, and behavior changes; to assess effectiveness of pharmacotherapy; and to identify side effects, drug interactions, or toxicity issues that need to be addressed.

The monitoring/follow-up component is the most tedious aspect of the PWDT. For each medication or intervention, key parameters must be identified as markers for effectiveness, for side effects, for drug interactions, and for toxicity. In addition, the time frame and process for assessing those parameters must be determined. Finally, the desired range for the parameter must be listed or a “decision point” must be identified to signal that additional action will be required.

It should be noted that only a limited number of parameters are selected for a given patient. For example, it is not necessary to list and monitor for every possible side effect with equal intensity and frequency. Selection of the monitoring parameters is based on the positive effects (efficacy) that are most important to the care of that patient, as well as the adverse effects (side effects, toxicity, or drug interactions) that are most important to avoid for the safety of that patient or to which that patient is most prone.

Because the monitoring component is usually extensive, examples listed for B.L. in Table 5 have been limited to three of the medication or regimen changes that were made at the first pharmacist visit: switching from fluvastatin to atorvastatin; switching from two shots of premixed 75/25 lispro to bedtime glargine with premeal lispro; and substituting the combination inhaler product for her fluticasone and salmeterol MDI prescriptions. Because atorvastatin and fluvastatin differ chemically, the monitoring parameters for this change are similar to those for initiation of a new medication. Monitoring for the new insulin regimen (basal insulin with premeal bolus) focuses primarily on glycemic control patterns and hypoglycemic episodes. Because B.L. has previously used the two ingredients of her new inhaler product (fluticasone and salmeterol) without adverse effect, monitoring of her new asthma therapy is focused on effectiveness, tolerance of inhalation of its dry powder formula, and use of the administration device.

Diabetes patients with multiple co-morbidities have concerns about all of their problems, not just the diabetes; therefore, BC-ADM pharmacists must comprehensively explore all the ramifications of comorbidities as well as patients’ feelings, expectations, and concerns for total health. B.L. is a good example of this; even though her referral was for “diabetes management,” her greatest concern at this visit was her asthma exacerbations.

As can be seen in this case, each coexisting disease or coprescribed drug has a domino effect, affecting other diseases or drugs and ultimately affecting quality of life. With input from B.L., the pharmacist clinician was able to develop a PWDT that addresses her diabetes as well as her other health care needs.

B.L. was able to leave the health center with a few achievable self-care goals and medication changes that address her acute concerns and with the knowledge and confidence that, at each subsequent visit, additional progress will be made toward her personalized health status goals.

Examples of B.L.’s Desired Outcomes

Examples of B.L.’s Therapeutic Endpoints

Examples of B.L.’s Medication-Related Problems

Examples of B.L.’s Interventions (Prioritized and to be Implemented Accordingly)

Examples of B.L.’s Monitoring Plans

Peggy Yarborough, PharmD, MS, BC-ADM, CDE, FAPP, FASHP, NAP, is a professor at Campbell University School of Pharmacy in Buies Creek, N.C., and a pharmacist clinician at Wilson Community Health Center in Wilson, N.C.

For information concerning POEMs and DOEs: a multitude of literature on this topic is available through Internet sources. Search for “patient oriented evidence that matters” using a medical topic browser.

Email alerts

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Epilogue

- Advanced Practice Care: Advanced Practice Care in Diabetes: Preface

- Online ISSN 1944-7353

- Print ISSN 1040-9165

- Diabetes Care

- Clinical Diabetes

- Diabetes Spectrum

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes

- Scientific Sessions Abstracts

- BMJ Open Diabetes Research & Care

- ShopDiabetes.org

- ADA Professional Books

Clinical Compendia

- Clinical Compendia Home

- Latest News

- DiabetesPro SmartBrief

- Special Collections

- DiabetesPro®

- Diabetes Food Hub™

- Insulin Affordability

- Know Diabetes By Heart™

- About the ADA

- Journal Policies

- For Reviewers

- Advertising in ADA Journals

- Reprints and Permission for Reuse

- Copyright Notice/Public Access Policy

- ADA Professional Membership

- ADA Member Directory

- Diabetes.org

- X (Twitter)

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Terms & Conditions

- Get Adobe Acrobat Reader

- © Copyright American Diabetes Association

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

Tensions in Diabetes Care Practice: Ethical Challenges with a Focus on Nurses in a Home-Based Care Team

- Open Access

- First Online: 20 July 2017

Cite this chapter

You have full access to this open access chapter

- Pei-Yi Liu 3 &

- Helen Kohlen 4

20k Accesses

Caring for patients with chronic diseases, including diabetes, causes ethical dilemmas and challenges healthcare professionals constantly during their daily work, particularly nurses. This qualitative case study concentrates on home-care nurses’ experience in diabetes care practice, where complex care takes place in a multi-professional team. The research findings show that home-care nurses experience tensions in the diabetes care context. Tensions can be identified around three themes: identification of care receivers, performance of care actions and foundations of care relationships. The healthcare environment revealed a sense of responsibility without authority, while professional caring responsibilities are not made explicit. Nurses are observably overwhelmed in diabetes care. The research findings may assist in improving diabetes care practice by clarifying the nursing professional’s roles, intensifying nurses’ professional awareness and caring competencies, as well as establishing a nourishing care environment in which all care team members share responsibility and caring.

The authors would like to acknowledge the research support of the department of the home-care centre (PflegeNetz) at the university hospital Freiburg, which provided the opportunity to have conversations with the participants on which this study is based.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Interprofessional care of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care: family physicians’ perspectives

Jacqueline M. I. Torti, Olga Szafran, … Neil R. Bell

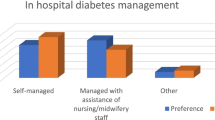

Nurse, midwife and patient perspectives and experiences of diabetes management in an acute inpatient setting: a mixed-methods study

Sara Holton, Bodil Rasmussen, … Ilyana Mohamed Hussain

Exploring interprofessional collaboration during the integration of diabetes teams into primary care

Enza Gucciardi, Sherry Espin, … Linda Dorado

- Diabetes Care Practices

- Home-based Care Teams

- Care Receiver

- tensionTension

- diseaseDisease

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

Introduction

The prevalence of diabetes is rising worldwide and the condition has become a major health and economic problem. Diabetes is a chronic illness which results in a relentless, ongoing and incurable suffering, and an inseparable part of it is the suffering of the whole person. The appropriate management of diabetes care includes more than just glycaemic control. How to support patients to live well with diabetes is a tough lifelong task for both patients and healthcare professionals.

Scholars have engaged in promoting the quality of diabetes care for a long time. Disease self-management and self-efficacy have been reported as important concepts in diabetes care and empowering patients to be active can lead to successful diabetes management (Moser et al. 2006 ; Shigaki et al. 2010 ). For patients and healthcare professionals, respecting the disease without letting it dominate the patient’s life is key (Ingadottir 2009 , pp. 77–92). Normalizing the process of managing diabetes can encourage patients to regulate their lifestyles with respect to controlling the disease (Olshansky et al. 2008 ).

In diabetes care practice, an individual care plan tailoring to the patient’s needs and ongoing care provided by healthcare professionals who work together could be suggested as constituting good care (McDonald et al. 2012 ). A collaborative healthcare team can not only strengthen diabetes self-care in practice, but also ensure that effective medical, preventive and health maintenance interventions take place (Von Korff et al. 1997 ). The foregoing argumentation reinforces the need for implementation of “The Logic of Care” in diabetes care practice to achieve improvement.

“The Logic of Care” is based on Mol’s field research. Using methods such as ethnographic observations, background research and interviews with diabetes patients and medical practitioners in a hospital in the Netherlands, Mol ( 2008 ) engaged critically with the current healthcare models which see patients as consumers and citizens. In the light of Mol’s argumentation, care is not a limited product, but more like a dynamic and open-ended process (Mol 2008 , p. 14). A caring process consists of interactive relationships among all of the caring actors (e.g. patients and professionals), and it can be shifted and adapted according to different care outcomes (Mol 2008 , p. 20). With respect to the concept of patients as citizens who have abilities and rights to make their own choices and enact their will, Mol elaborated that the patient-citizens have little choice but to bracket a part of what they are and seek ways to live with a disease (Mol 2008 , p. 35). Caring is therefore a matter of being attuned, respecting and being adaptable instead of controlling (Mol 2008 , p. 36).

By Mol’s assumption, care has its own logic. But one kind of logic (e.g. the logic of care) is not always intrinsically better than other kinds of logic (e.g. the logic of choice) (Mol 2008 , p. 92). In practice, we sometimes need the logic of care, but it can be employed alongside other logics depending on the care situation . It is important that all caring actors be active (Mol 2008 , p. 93). In this paper, we utilized “The Logic of Care” conceptualized by Mol for our research approach. Meanwhile, we stressed the ethical dilemmas occurring in a home-based care team.

The notion of the global marketplace has spread to the domain of health services, so that health has come to be seen as a commodity, with the body as its site and the patient as a customer (Parker 1999 ). Patients’ satisfaction has become a significant indicator to measure the quality of care when patient-centred care is supplied (Robin et al. 2008 ; Wagner and Bear 2009 ). Footnote 1 The challenge for healthcare workers is to work within, but also to resist the reductionist impetus of economically based and commercially driven approaches to healthcare (Parker 1999 ). Healthcare workers face the rigorous tasks of maintaining holistic care, preserving the personal and professional–recipient relationship and finding ways of demonstrating their capacity to deliver high-quality care in a cost-effective way (Parker 1999 ). Moral tensions may accordingly arise.

Moral tensions in care practice may additionally originate in the different understanding of illness and the distinct demands of diabetes care on healthcare professionals and patients. Patients focus more often on consequences and the impact on their daily life, while healthcare professionals pay more attention to the medical treatment and economic efficiency (Hörnsten et al. 2004 ). Whereas healthcare professionals pay much attention to the best interests of patients , they usually have to exercise both clinical and moral responsibilities in relation with patients. For this reason, care responsibilities are determined not only by considerations of the patients’ rights and respect for their freedom but also by consideration of the wider health needs of the individual and the community (Thompson et al. 2006 ).

In the healthcare system, medical orientation, hierarchy, authority and unequal power among physicians, patients and nurses are noticeable (Daiski 2004 ; Kramer and Schmalenberg 2003 ). The hierarchy between different professionals affects how a professional can act on his own moral position (Kälvemark et al. 2004 ). How do healthcare workers work within this kind of medical environment and simultaneously preserve their professional awareness ? Which care problems and ethical dilemmas can be raised? How do healthcare workers practically reflect on care problems and ethical dilemmas? And how do healthcare workers deal with them in their daily work? To further grasp the ethical dilemmas in diabetes care, it makes sense to take a look at the actors and to review how authority , responsibility and trust play out among physicians, patients and nurses in everyday practice.