How mind maps make researching easier

When you’re first brainstorming a new idea or researching a topic, you don’t know what ideas you’re going to come up with. As such, it’s hard to plan a layout for the information in a typical report format. A mind map allows you to free yourself from a predefined structure, and lets the ideas grow as you develop them, ensuring that you don’t lose track of your thoughts.

- What is a mind map?

A mind map is a visual tool for structuring thoughts. It can be used on an individual or team basis, and results in a hierarchical diagram of everything that has been discussed. The diagram is focused on a single element, where it is discussed, ideas are written down, spreading outwards from the original focus. This spreading and recording of key ideas helps trigger further ideas, and results in their natural grouping.

Records of the use of mind maps date back as early as the third century, and the idea of visually plotting one’s ideas has been used in many different ways throughout history. Through this time, the concept did not have a specific name, and it was only in the 1970’s that British psychologist Tony Buzan popularized the term mind map.

- When to use a mind map

Mind maps are extremely versatile and have a number of potential uses. A mind map’s hierarchical and graphical nature also assists one in memorizing the information you lay down on it, giving them a number of applications:

- As a study aid — you were quite likely taught how to use one growing up, but their visual element is great at triggering memories.

- Researching new products and developing new ideas — as you discuss topics, they are recorded, allowing you to track idea development more easily, and for visualization for multiple people.

- As a problem-solving tool — helpful in brainstorming problems and building on ideas to determine solutions.

- As a presentation method — one is able to show how a process was developed, visualizing alternatives and topics discussed.

While useful for an individual to come up with ideas on their own, a mind map is a great tool for teams that are brainstorming together, ensuring that everyone’s ideas are heard and recorded in a logical, easy to absorb manner.

- Making a mind map with a template

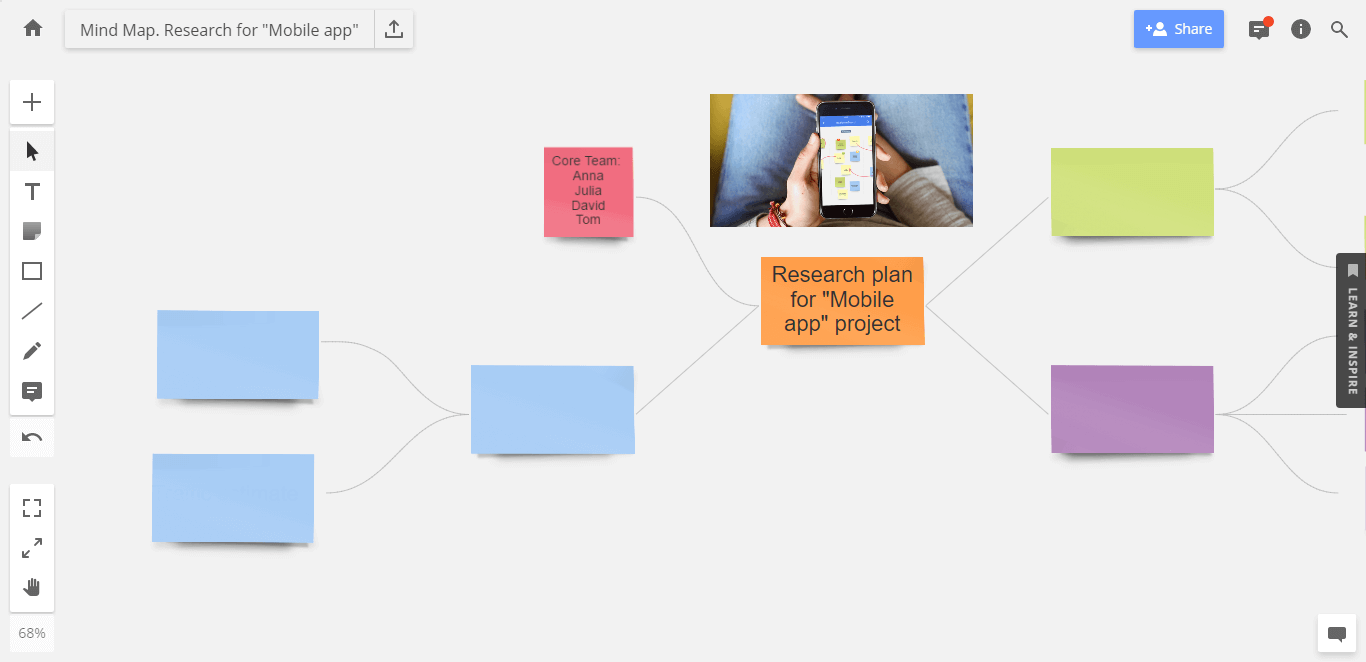

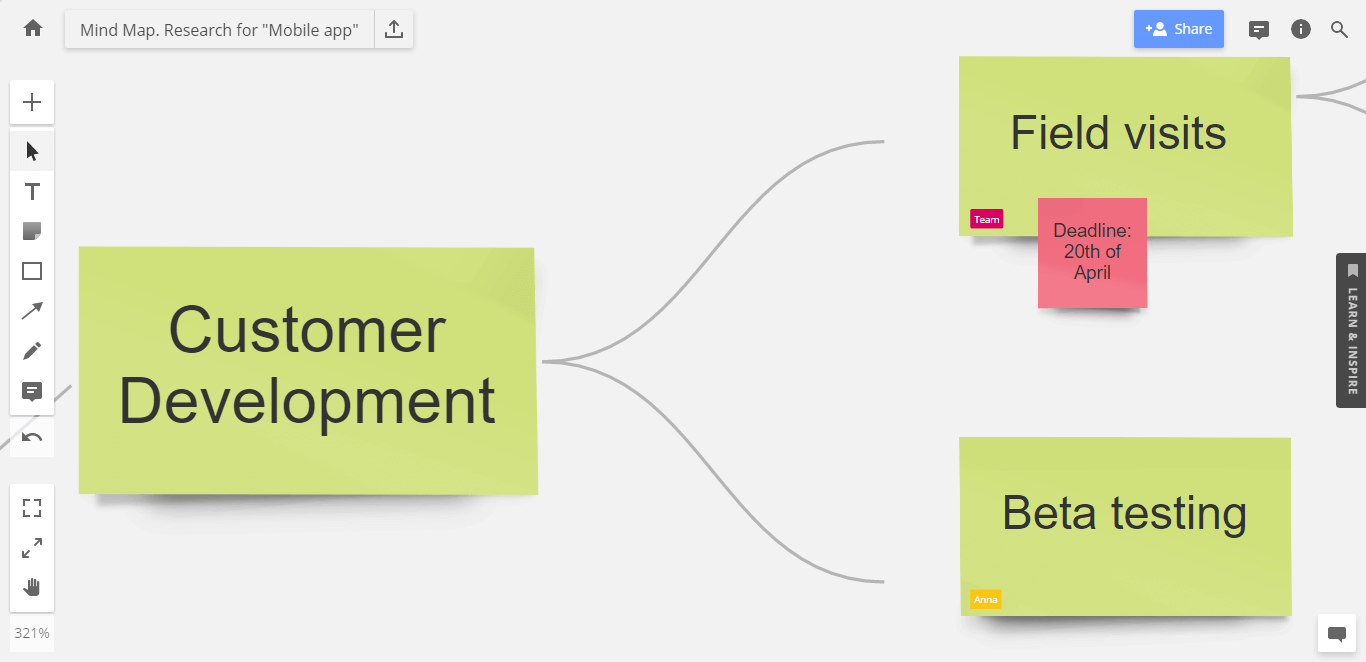

Making a mind map is a fairly straightforward task, but there are a few steps and hints that you can follow to ensure you get the most out of the exercise. To make things easier to understand, we’re going to demonstrate by creating our mind map. While you can jot one down on a piece of paper, there are a number of advantages to be had when using an online mind map maker. So, for our example we’ll use a mind map template in Miro to demonstrate each step.

Step 1: Start with a focus

You’re creating a mind map for a specific reason, whether it’s a subject that you’re investigating, or information you need to present. This idea or thought needs be the center of your mind map. As such, most mind map makers will place your focus idea, or goal, in the middle of the page.

For our example, we want to perform research, with the goal to launch a mobile app for an existing software product.

Pictures and visual elements are much easier for the human brain to remember, and are more likely to trigger associated thoughts than just words. Miro’s visual workspace allows you to upload images, gifs, etc., making it easy to include them in your mind map. Consider using a picture to represent your mind map’s focal idea.

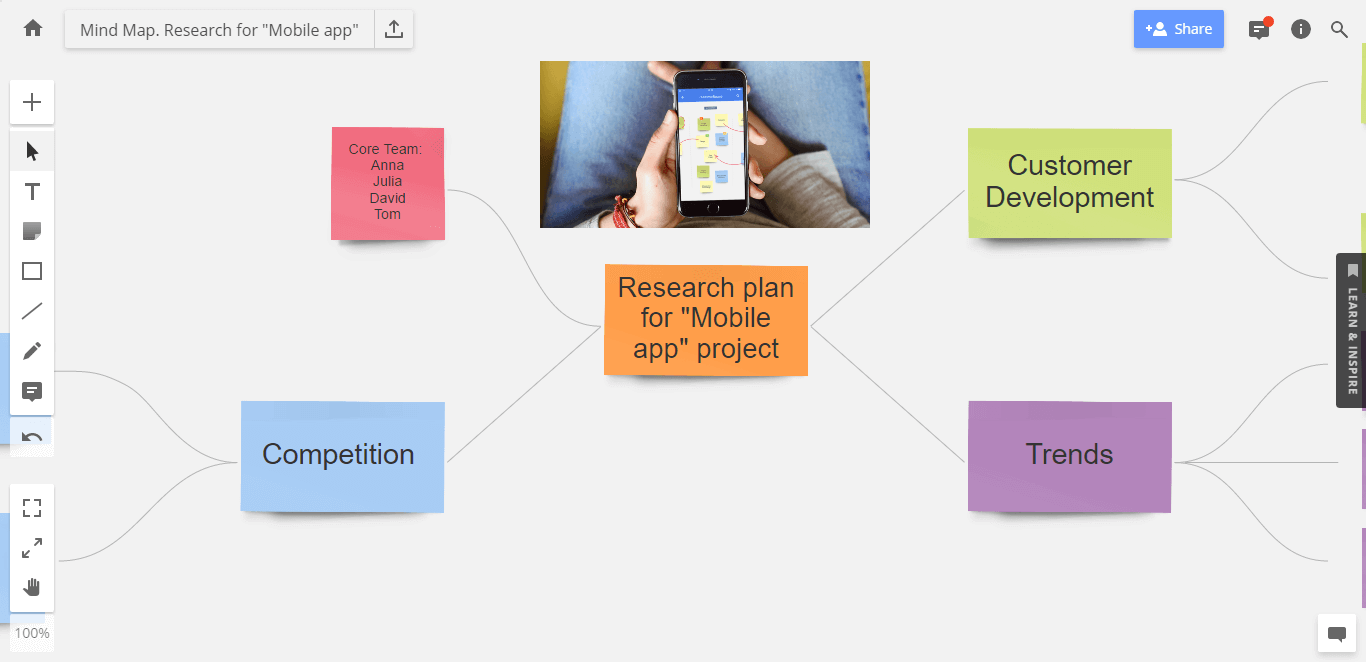

Step 2: Plot sub-groups

From your main idea, you will determine key areas, which are sub-groups of your focus. These can be extremely varied or similar, as long as each group is a distinct subset of the main focus. These groups are connected as lines to our focus.

For our user research, we start quite broad and choose to consider the following three topics:

- Customer Development — we want to confirm that our app will be beneficial to our clients and that the added value will result in maintained or increased profits.

- Trends — to ensure our user experience is up-to-date, we want to discuss new trends that could be implemented.

- Competition — to help understand the current market and identify ways to make our product better, we must analyze competitors’ products.

Don’t be concerned if you only have a few sub-groups. Ideally, you will have less than five, but each mind map has its own requirements, so this can vary.

Group tips:

- To help reinforce the grouping, make use of different colors for each group. You can either draw the lines in different colors, or write or highlight the words in separate colors.

- If you’re not sure what groups to create, try to answer questions about the topic, for example, how you want to perform the research, what results you expect. Each question can be associated with a word and used a group.

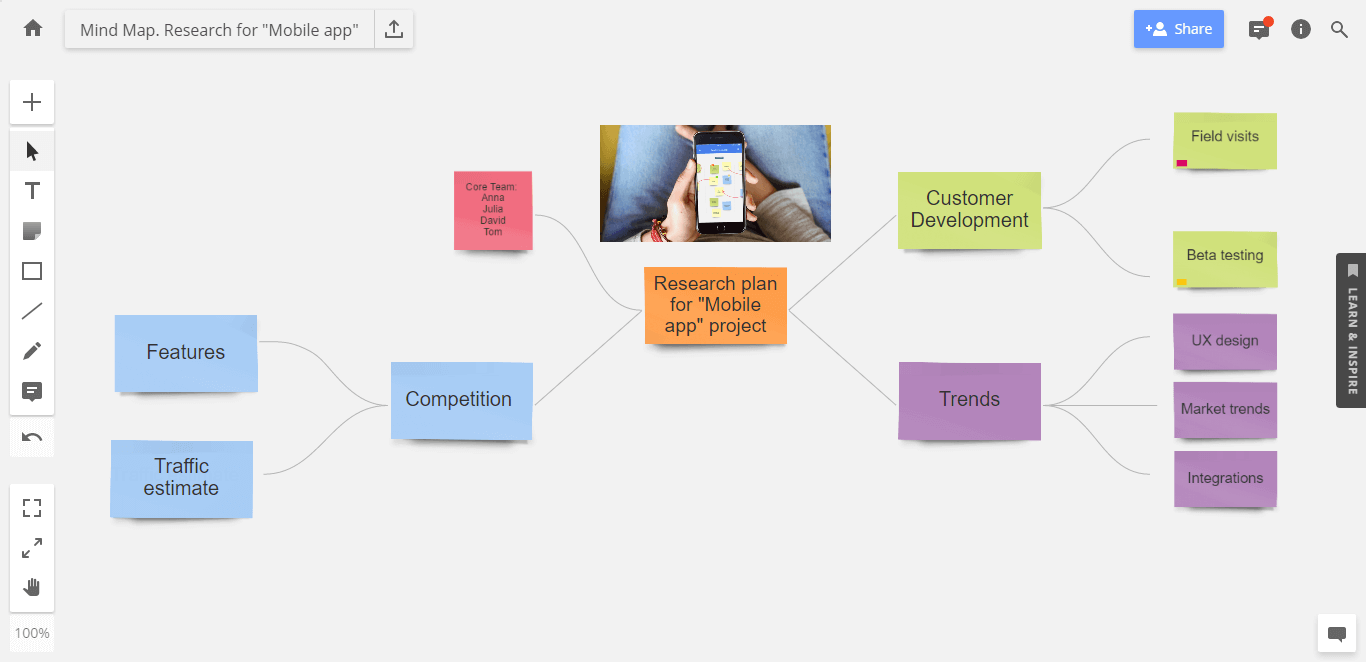

Step 3: Develop further

Each of your sub-groups will likely have their own set of sub-groups. For each of your areas, consider what they mean, and what ideas you feel link to that topic. Look at one group at a time, but come back to a group if there is more to add to it.

When we consider our groups, the next tier for each one could be:

- Field visits — how do users use similar apps now in their day-to-day job?

- Beta testing — to get feedback from customers to the MVP version.

- UX design — look at recently released apps to see what works well.

- Integrations — what other services do, which our users use, where there would be a benefit integrating with our app.

- Market trends — read latest blogs and articles to keep app design up-to-date.

- Features — what features competitor products offer.

- Traffic estimate — how popular competitor products are among users.

We’ve only included a few possible expanded groups here. No doubt, you can easily come up with several more for our fictional situation yourself. Add as many as you feel is necessary for your mind map.

Further development tips:

- For each branch and new item that you use for your mind map, try make use of a single keyword, or keyword pair instead of writing entire phrases. It makes your mind map easier to view and manage, but also prevents you from restricting your thoughts too much, leaving terms open to interpretation.

- Mind maps are often made by writing each keyword on a line. Some people prefer to have the keyword at the end of a line. Both ways work well, and are left to user preference. Try using both to determine which works better for you.

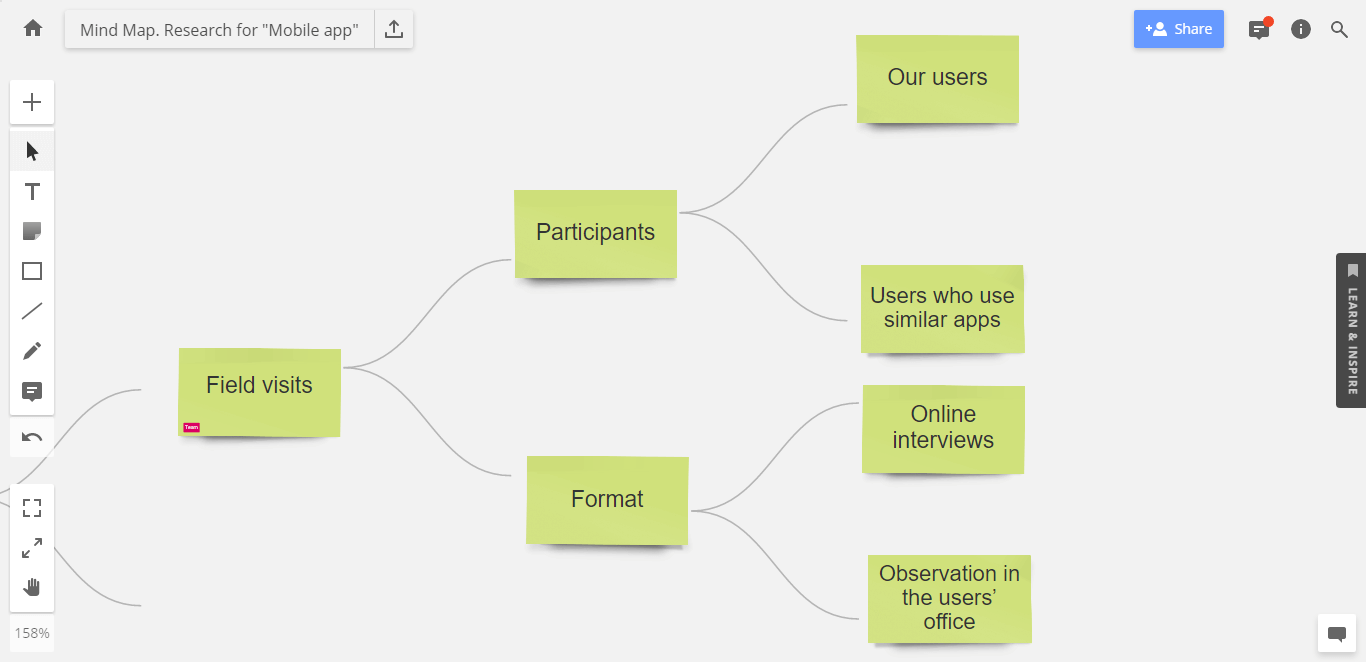

Step 4: Expand

At this stage, you’ve done all the groundwork, and you just need to add as many ideas as you can. Remember, you can always cull ideas at a later stage or move them, so don’t hold back. Record everything that you think of or that is discussed.

As you continue, you might find it easier to focus on a sub-group and fully populate it. Other times, especially when working in teams, people are focusing on different areas at the same time, and you will find as you jump from one group to the next, both approaches will give you the same result.

If necessary, don’t be afraid to add a whole new sub-group to your main focus. There may be something which you didn’t think of earlier, or an existing branch which you have developed to an extent that you feel it deserves to be on its own.

Our example mind map is far from complete. We can expand on some of the points as follows:

- Current users — clients who currently use our software.

- Potential — identify users who use similar apps.

- Online interviews — for those customers who are based in other countries.

- Observation in the users’ offices — for customers who are close to the office.

Expansion tip:

While you’re working on a mind map, you might find that it generates tasks that need to be completed. You can easily assign tasks to people in your team by encircling certain points and writing a team member’s name and a due date.

- How to save time when making a mind map

Mind maps are a tool to help you work more effectively. Effectiveness is minimized if you spend the whole day working on a single mind map. Your mind map doesn’t have to be perfect. Your mind map doesn’t have to be a work of art. With practice, you’ll figure out what works best for you, but don’t be concerned about finding the perfect image to represent your thought, and don’t worry about colors clashing. What’s important is putting the ideas down. If you need to present the results, you can tidy it up at a later stage, but the most value is found in the creation process, and this should be easy.

As we’ve shown you, a good way to speed up your mind map making is to use a visual workspace instead of pen and paper. The pages expand to fit the extent of your ideas, and you don’t have to waste time trying to plan your layout. You can also easily delete, edit and move ideas on the board. They have the added benefit of allowing remote teams to work together on the same mind map.

If you’re looking for more information or tips about making mind maps, consider checking out one of the following links:

- TonyBuzan.com — learn from the master, Tony Buzan’s website offers a number of additional resources for making the perfect mind map.

- IQMatrix.com — a very extensive article with more information than you could ever need.

- Incorporating mind maps into your work

Different people will often come up different ideas or groups that they feel are the key areas of focus for a mind map. Given the same inputs, different people will all develop a different looking mind map, but the process will still generate the same end items, just grouped differently. That is not something to worry about, though.

One of the great things about mind maps is how much freedom you have with them, both in potential uses, and how you develop them. The more you practice, the more you’ll find a style that suits you, and new ways to use them.

Mind maps are quick and easy to use. Try find new ways to implement them into your work.

Miro is your team's visual platform to connect, collaborate, and create — together.

Join millions of users that collaborate from all over the planet using Miro.

Keep reading

Don’t let ideas die post-retro: 5 ways to make retrospectives more actionable.

Removing the hassle of brainstorm documentation with Miro + Naer

From ideas to execution: 5 ways to go beyond brainstorming to bring ideas to life

Narrowing It Down: Mind Mapping 101: Home

What is mind mapping, mind mapping is a learning tool that can be used to flush out your ideas and organize your thoughts using a diagram. you take your central idea and write out what you know about that particular area. ask the who, what, where, and why questions surrounding your topic area. list key people, date ranges, policies, and even geographical areas that influenced the development of your topic area. creating a mind map gives you the space to remember what you know, and find gaps for what you would like to learn. it is a process that builds confidence in the research process and provides a guide for you to use while searching online and within the databases. it is a great addition to your search strategy rule book. , hazel wagner | tedxnaperville.

Topic Development From a Different Vantage Point

Choosing a topic can be difficult - where do you even start? Below are some videos and tutorials that will help you to understand the research process and how to settle on a topic for your paper that you can further research. Remember - be flexible when doing research - the topic you start with may change by the time you write your paper!

NOTE : These tutorials are only available for currently enrolled LSU students, faculty, and staff. When attempting to access tutorials from off campus, users will be prompted to login to their myLSU Account.

- Video: The Research Process

- Developing a Research Focus

- Choosing a Topic

- Video: How to Narrow Your Topic

Download the MindMap and WordBank

- MindMap and Word Bank

Download Concept Mapping Guide by Center of Academic Success

- Concept Mapping

Mind Mapping and Word Banking

In addition to mind mapping, a word bank is a great tool to use as you are searching online. During your background research process, you will come across various phrases and terms that journalist, experts, and scholars use to discuss your chosen topic. Utilizing this tool helps build a bank full of key words and s earch terms that can be used interchangeably with boolean operators ( AND, OR, NOT or AND NOT) to search for records within the databases.

The difference between mindmapping and concept mapping, what is a concept map, it gives the relationship between individual ideas, words, or images that create a bigger picture. they depict requirements, cause and effect, and contributions between items. concept maps are the best tool for developing logical thinking, breaking down complex systems, and understanding specific ideas' roles within more prominent topics. - mind manager.com .

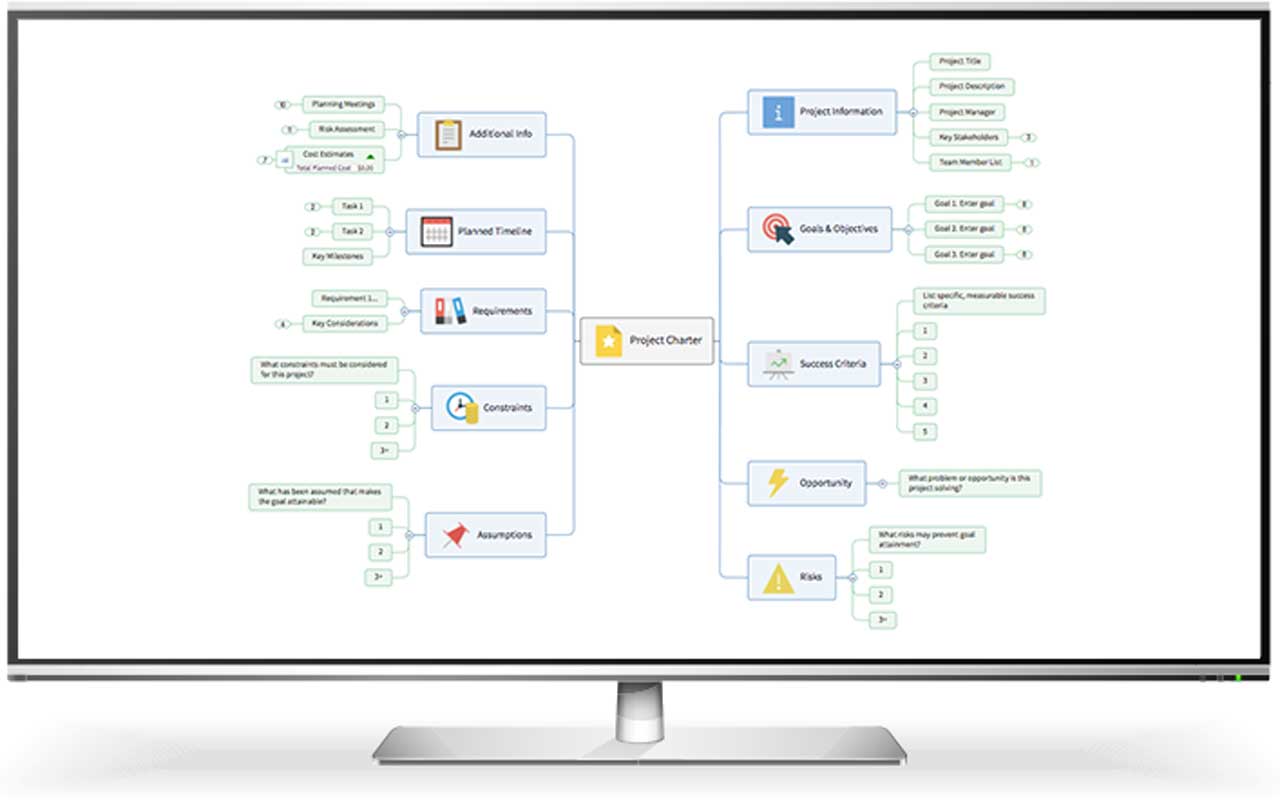

Table image from ZenFlow Chart

African and African American Studies Librarian

Online Mind Mapping Tools

Literati by Credo : Virtual MindMap

- Credo Reference This link opens in a new window Credo Reference is a general reference solution for learners and librarians. Offering 551 hundred highly-regarded titles from over 70 publishers; Credo General Reference covers every major subject. Credo Reference is an online reference service made up of full-text books from the world's best publishers. Whether you're working on a research paper, trying to win trivia or just curious, Credo Reference has something for you.

- Last Updated: Oct 4, 2023 2:18 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.lsu.edu/c.php?g=1206028

Provide Website Feedback Accessibility Statement

- Search Site

- Campus Directory

- Online Forms

- Odum Library

- Visitor Information

- About Valdosta

- VSU Administration

- Virtual Tour & Maps Take a sneak peek and plan your trip to our beautiful campus! Our virtual tour is mobile-friendly and offers GPS directions to all campus locations. See you soon!

- Undergraduate Admissions

- Graduate Admissions

- Meet Your Counselor

- Visit Our Campus

- Financial Aid & Scholarships

- Cost Calculator

- Search Degrees

- Online Programs

- How to Become a Blazer Blazers are one of a kind. They find hands-on opportunities to succeed in research, leadership, and excellence as early as freshman year. Think you have what it takes? Click here to get started.

- Academics Overview

- Academic Affairs

- Online Learning

- Colleges & Departments

- Research Opportunities

- Study Abroad

- Majors & Degrees A-Z You have what it takes to change the world, and your degree from VSU will get you there. Click here to compare more than 100 degrees, minors, endorsements & certificates.

- Student Affairs

- Campus Calendar

- Student Access Office

- Safety Resources

- University Housing

- Campus Recreation

- Health and Wellness

- Student Life Make the most of your V-State Experience by swimming with manatees, joining Greek life, catching a movie on the lawn, and more! Click here to meet all of our 200+ student organizations and activities.

- Booster Information

- V-State Club

- NCAA Compliance

- Statistics and Records

- Athletics Staff

- Blazer Athletics Winners of 7 national championships, VSU student athletes excel on the field and in the classroom. Discover the latest and breaking news for #BlazerNation, as well as schedules, rosters, and ticket purchases.

- Alumni Homepage

- Get Involved

- Update your information

- Alumni Events

- How to Give

- VSU Alumni Association

- Alumni Advantages

- Capital Campaign

- Make Your Gift Today At Valdosta State University, every gift counts. Your support enables scholarships, athletic excellence, facility upgrades, faculty improvements, and more. Plan your gift today!

Developing a Research Topic: Concept Mapping

- Concept Mapping

- Developing Keywords for Searching

- Boolean, Truncation, and Wildcards

- Topic Ideas

- Writing a Research Question

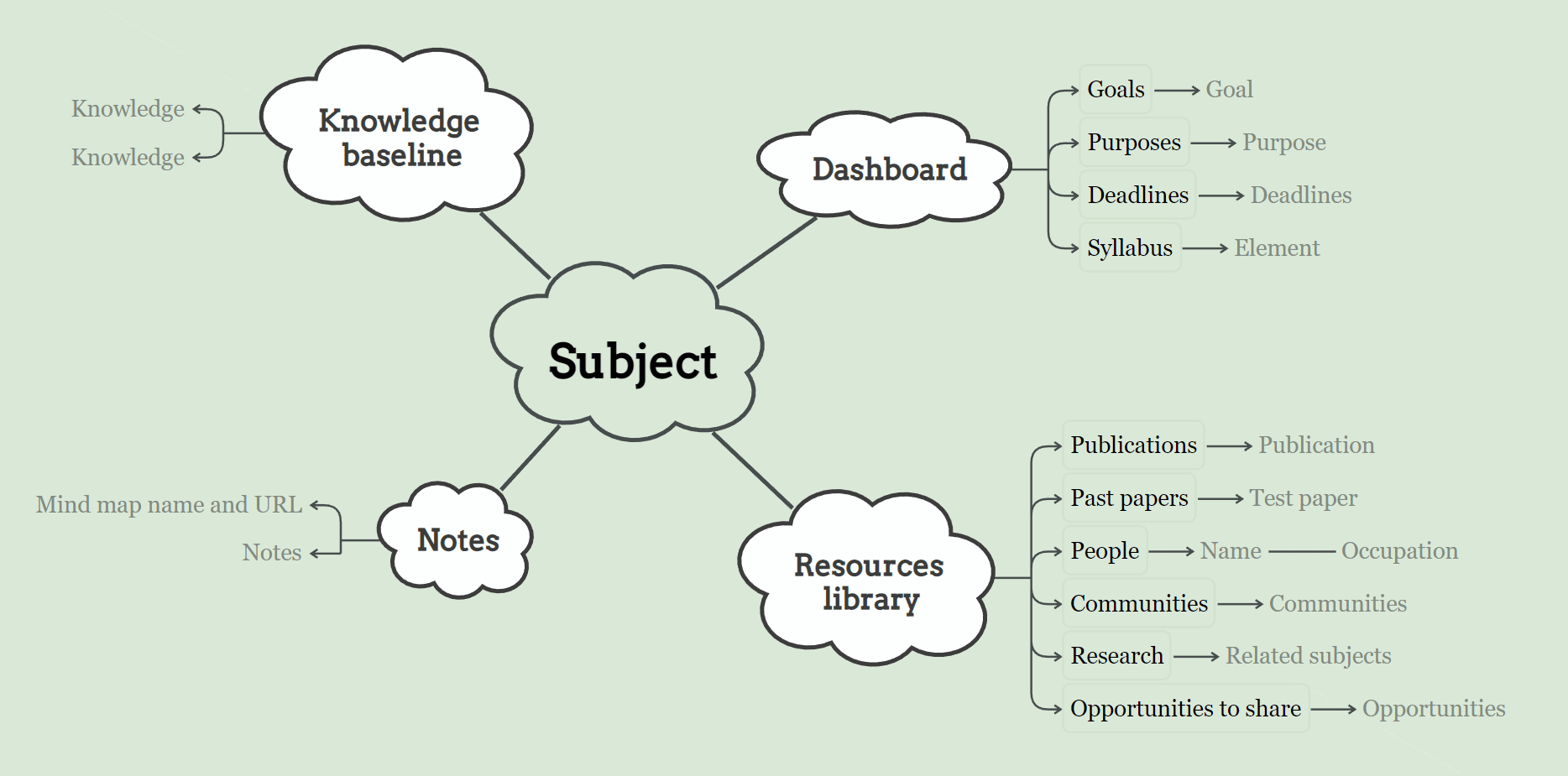

Concept Map / Mind Mapping

What is a concept map.

A concept map is a visual representation of what you know about a topic. Concept maps help you organize your thoughts and explore the relationships in a topic. Use a concept map to organize and represent what you know about a topic. Explore the connections between elements of the topic.

Why use a concept map?

Concept maps can be used to develop a research topic. They are a useful brainstorming tool.

Concept maps can be used to study. Mapping what you know about a subject and examining the relationships between elements help you develop a greater understanding of the material.

How do I create a concept map?

- On a whiteboard

- Any way that works for you!

How do I organize the map?

Most of the time you start with the central idea, topic, or subject. Then you branch out from that central point and show how the main idea can be broken into specific subtopics. Each subtopic can also be broken into even more specific topics,

Make a Research Appointment

Click Make a Research Appointment to schedule a meeting with a librarian!

Organize what you know by subtopic in a topic map.

Use the topic map to define your research topic.

For example: geography - local travel - rail - variants - rail systems - designs & availability - emissions - research & evidence

Make a topic statement or research question.

I am researching the environmental impact of using commuter rail systems in cities.

How does using commuter rail systems in cities affect the environment?

Concept Map, Mind Mapping

Example concept map.

- Next: Developing Keywords for Searching >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 11:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.valdosta.edu/research-topic

- Virtual Tour and Maps

- Safety Information

- Ethics Hotline

- Accessibility

- Privacy Statement

- Site Feedback

- Clery Reporting

- Request Info

- X (Twitter)

What is a Research Mind Map, and how can it help you?

Anyone who is in research, especially in higher education or product development, should know the power of mind maps already. These are sometimes explicitly referenced as a research mind map. However, instead of starting to draw everything out on a piece of paper, it’s best to work with a diagramming tool . Becoming a master of mind maps will help to unlock the power of visual representation and learning .

Many people believe you can only use a mind map in early education or business. Yet mind maps are used all the time whether we know it or not. Imagine the last time you grabbed a piece of paper and started writing down notes. You’re in a class with these notes, and you start drawing shapes around some keywords. You then start to draw arrows or lines to other words from this key central point. In essence, this comes from you as a visual learner, and you’re working on building your first mind map template.

This note-taking endeavor will allow you to build a research mind map in no time. All you need to do is reinforce your understanding of how mind maps can be used in education . That’s because it will be your first step in using a mind map for research. Make sure to understand the different stages of a traditional mind map as well.

How do you write a mind map for research?

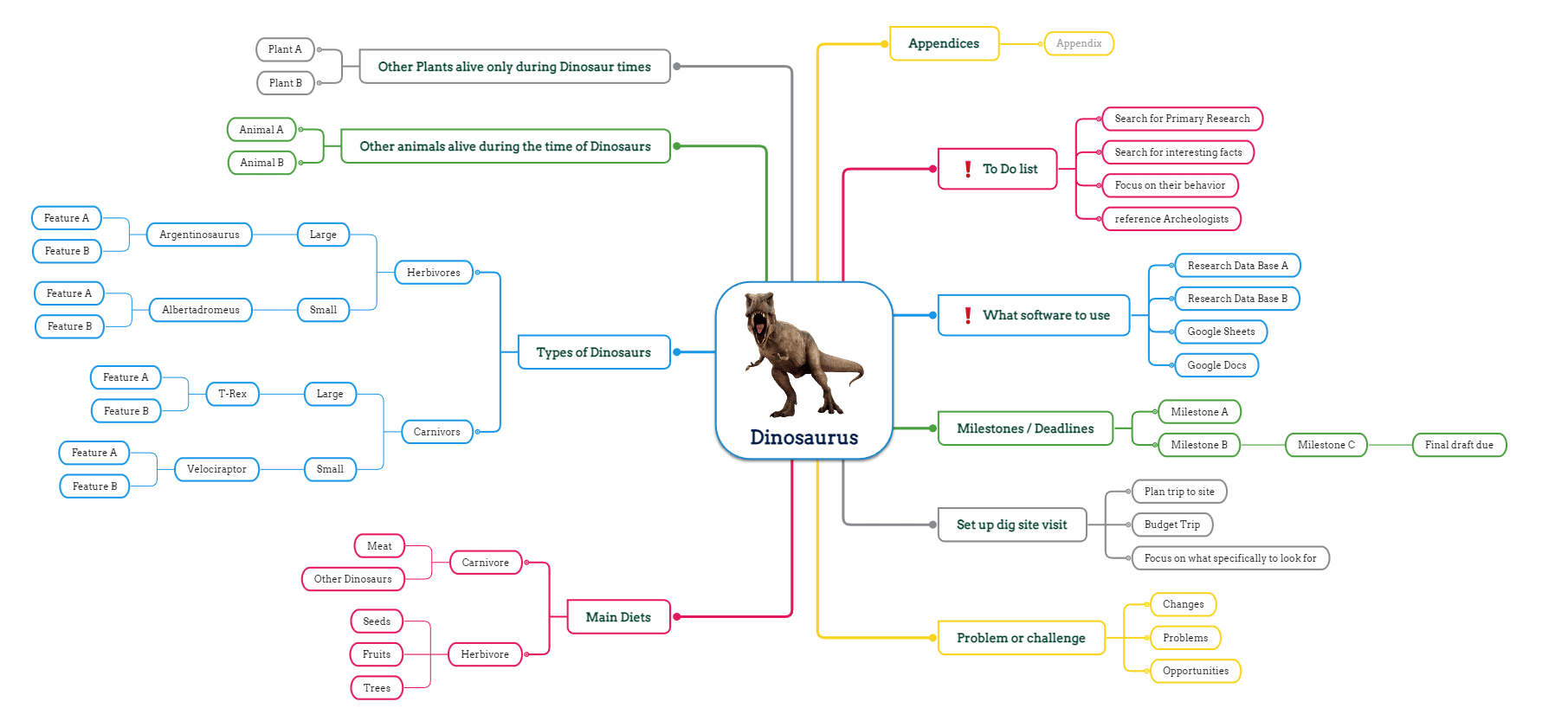

Traditional mind maps are all about brainstorming your ideas. Most mind map examples out there showcase this, yet when it comes to research, we take the opposite direction. We want to take a more focused approach and represent that in our mind map template.

With the core topic in mind, it’s even best to consider using an image in the center. But, again, it helps to bring a different medium to your mind map examples.

In this case, our focus will be dinosaurs. This research mind map will end up acting not only as a place for research but an outline of tasks. This helps to provide a completely holistic approach and has everything on one digital mind map .

Once you find your focus – you want to build out your subgroups. These will be that mix of research areas, deadlines, to-do lists, and other components that are part of the research. It should have the core research problem being looked into.

Keep in mind to stay focused with this digital mind map. You don’t need any special mind-mapping software for research. Just find the most flexible and feature-rich diagramming tool possible, such as us at Mindomo.

What does research include?

It doesn’t matter if you’re looking into academic research or professional research. If you’re looking into product research at a company, it will have similar data categories. Research is a way to increase our overall collective knowledge. It is done to evaluate a hypothesis as well as generate questions for additional research. Part of doing research is to combine it all together, the knowledge, data, references, and inferences into a presentable format.

A research mind map helps with the collection of the components of research. This includes:

- Documentation

- Information

- Data collection

- Analysis results.

There are different methodologies that one can use when conducting research as well. These are further broken down into whether you’re looking for qualitative research vs. quantitative research.

Sources of data for research come in three different formats. Again they are the same for academic or professional uses. First, we have first-party or primary data, which the researcher is collecting. A classic example is the collection of data through a survey.

Then there’s second-party or secondary data which is the use of existing verifiable data sources. This helps to validate primary data at times. There are also third-party data, which isn’t always used in research. This is more about reference data that doesn’t directly tie into what the research is about.

Why use a mind map for research?

When using mind mapping software for research, it’s all about organization and reducing chaos. From there, the benefits of using a digital mind map become easier to see.

It becomes your organizational tool

As mentioned a few times, here is where everything comes together. This is your research planner, as well as your data sets. You can use one side for pure research information and the other side for tasks and to-do lists.

It’s easier to see relations and patterns

A research mind map will have all the data in one place. The inferences to prove the hypothesis will be easier to handle since you don’t need to switch between screens.

Excellent for collaboration

Research is best done in groups. Having a mind map online helps with this collaboration and can grow as the research data grows. It’s also great to use as an education mind map when training future researchers. Once all the research is published, it’s easy to convert the research mind map into an education mind map.

Just what is needed for future research

Using a research mind map built off of a mind map template means the ability to start new research immediately. In addition, a mind map template built out of a diagramming tool helps speed up administrative tasks and gets you focused on the research portion.

Finding the right diagramming tool

Mindomo helps you create a mind map template that can be customized to become a research mind map. It’s an excellent option for those that are looking for mind-mapping software for research and starts out free. You can easily build out your mind map online directly and start your collaboration today.

There are also plenty of Mindomo integrations possible to help integrate datasets and information as needed. No need to have one space for data collection, another place for structure, and another for tasks and deadlines. A research mind map will only help enhance your output, so why not branch out into this today?

Keep it smart, simple, and creative! The Mindomo Team

Related Posts

Unlocking the Power of Mind Mapping Software for Students

Unlocking the Power of Biology Mind Maps: A Visual Learning Revolution

Improving English Fluency: The Role of Mind Maps for English Learning

Science Mind Maps: Harnessing the Power of Mind Maps for Science Research

Cracking the Code to Creative Thinking: Ignite Your Brain and Unleash Your Ideas

How To Read a Book Effectively and Digest Information – Growth Reading

Write a comment cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Productivity

How to use mind mapping, this simple organizational technique could deliver powerful benefits..

Updated November 20, 2023 | Reviewed by Gary Drevitch

Cowritten by Kelsey Schultz and Tchiki Davis.

Mind mapping is a technique through which you develop and visually organize thoughts, ideas, and information. This technique involves identifying a central topic (often represented as an image) and creating branches indicating the relevant categories that are related to the central topic extending radially from the central idea (Budd, 2004).

A mind map essentially provides a scaffold that helps structure complex concepts and allows for a better understanding of the relationship between concepts (Zhao et al., 2022). In other words, a mind map allows you to take advantage of the vast neural real estate dedicated to visual processing and leverage it for breaking down complex topics into digestible or actionable bits.

The process of creating mind maps can have numerous benefits. For example, a mind map allows you to get into the details of a concept without losing track of the big picture. Mind maps can also help show the non-linear relations between different categories within a given concept. Additionally, mind maps can be an optimal method for collaborative brainstorming .

Psychological research has also shown that mind mapping is an excellent tool for enhancing learning and understanding. For example, in a sample of 120 8th-grade students, researchers found that students who were taught using a mind-mapping technique performed better on a subsequent test than students who were taught using traditional methods (Parikh, 2016).

Other studies have found similar results. For example, a study involving college freshmen taking a writing class showed that students who were taught to use mind maps to organize their ideas made greater improvements in their writing ability than students taught to organize their ideas using traditional methods (Al-Jarf, 2009).

How to Do Mind Mapping

- Define your central topic. First, consider what the focus of your mind map should be and write it out in the center of the page. For example, if you are mind mapping out a to-do list, you would simply write “to-do list."

- Identify your first-level concepts or topics. Next, consider the broader categories related to your central topic. These categories will become the first nodes branching off from the central point of your mind map. Sticking with the to-do list example, your first-level categories might include home, work, errands, and personal health.

- Expand your branches. Each of the first-level categories you defined will branch off into different sub-categories, or second-level categories. For example, branches from the first-level category “home” might include cleaning and preparing for visitors. Each of these second-level categories might also have branches. For example, the category “cleaning” might include vacuuming, laundry, and dishes, and the category “preparing for visitors” might include changing the sheets and making snacks. Each branch can expand as many times as necessary.

- Add images or annotations. Many people find it helpful to include images that represent different categories or different levels of priority. Using annotations or different colored pens when creating your mind map can also be a helpful way to indicate urgency or to set your different categories apart.

Pen and Paper

Pen and paper are easily accessible and provide ample flexibility in how your maps are structured. You can keep them simple with just a single pen and notebook paper, or you can get creative with different colored pencils, pens, stickers, and drawings. It might be helpful to get erasable pens if possible, in case you decide to reorganize some aspects of your map. Computer software can also be a great tool for mind mapping because it allows you to organize a vast amount of information in one convenient place.

Adapted from a post on mind mapping published by The Berkeley Well-Being Institute.

Al-Jarf, R. (2009). Enhancing freshman students’ writing skills with a mind-mapping software. Available at SSRN 3901075.

Budd, J. W. (2004). Mind maps as classroom exercises. The journal of economic education, 35(1), 35-46.

Parikh, N. D. (2016). Effectiveness of teaching through mind mapping technique. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 3(3), 148-156.

Zhao, L., Liu, X., Wang, C., & Su, Y. S. (2022). Effect of different mind mapping approaches on primary school students’ computational thinking skills during visual programming learning. Computers & Education, 181, 104445.

Tchiki Davis, Ph.D. , is a consultant, writer, and expert on well-being technology.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Support Group

- International

- New Zealand

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

- Search the site

What is Mind-Mapping? The Ultimate Guide to Using This Powerful Tool

Anthony Metivier | March 5, 2024 | Podcast , Thinking

Podcast: Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

Well, imagine you’re listening to a history lecture. Instead of taking notes , your fingers itch to make a mindmap of World War I events as you hear them.

But how do you draw mind maps?

And, can mind maps alone boost your memory, learning power, and creativity?

In this article, you’ll explore a complete guide to mind mapping, how to draw one, including multiple examples of mind maps. We’ll also examine whether mind mapping alone can improve your brainpower and creativity, and what else you can do.

Here’s what I’ll cover:

What is Mind Mapping?

- Benefits of Mind Mapping

Who, When, and How to Make a Mind Map

Tools you can use for mind mapping.

- Can Mind Mapping Alone Improve Your Memory?

- How to Combine a Mind Map with the Major System

Mind mapping is a simple, visual way to organize your ideas for better clarity and recall . Mind maps focus on only one central concept or idea and are based on radial hierarchies and tree structures.

What does all that mean? Let’s get into the details.

A Brief History and Definition of Mind Mapping Methods

The practice of drawing radial maps to map information goes back several centuries.

Some people credit the first mind maps to the 3rd-century philosopher Porphyry of Tyros . Ramon Llull , Leonardo Da Vinci, and Isaac Newton also used mind mapping techniques. Much later, in the 1960s, scientists Allan Collins and Ross Quillian developed the semantic network into mind maps.

However, it was psychology consultant Tony Buzan who first popularized the term “mind map.” Buzan drew colorful, tree-like structures called radial trees where a central topic branched out to several sub-topics.

The Tony Buzan Learning Center defines their Mind Map as “a powerful graphic technique which provides a universal key to unlock the potential of the brain. It harnesses the full range of cortical skills – word, image, number, logic, rhythm, color, and spatial awareness – in a single, uniquely powerful manner.”

These pictorial representations introduced by Buzan are now being used by students, teachers, engineers, psychologists, and others in many ways . His Mind Map Mastery is probably the best book he produced on the topic.

So, what does a mind map look like?

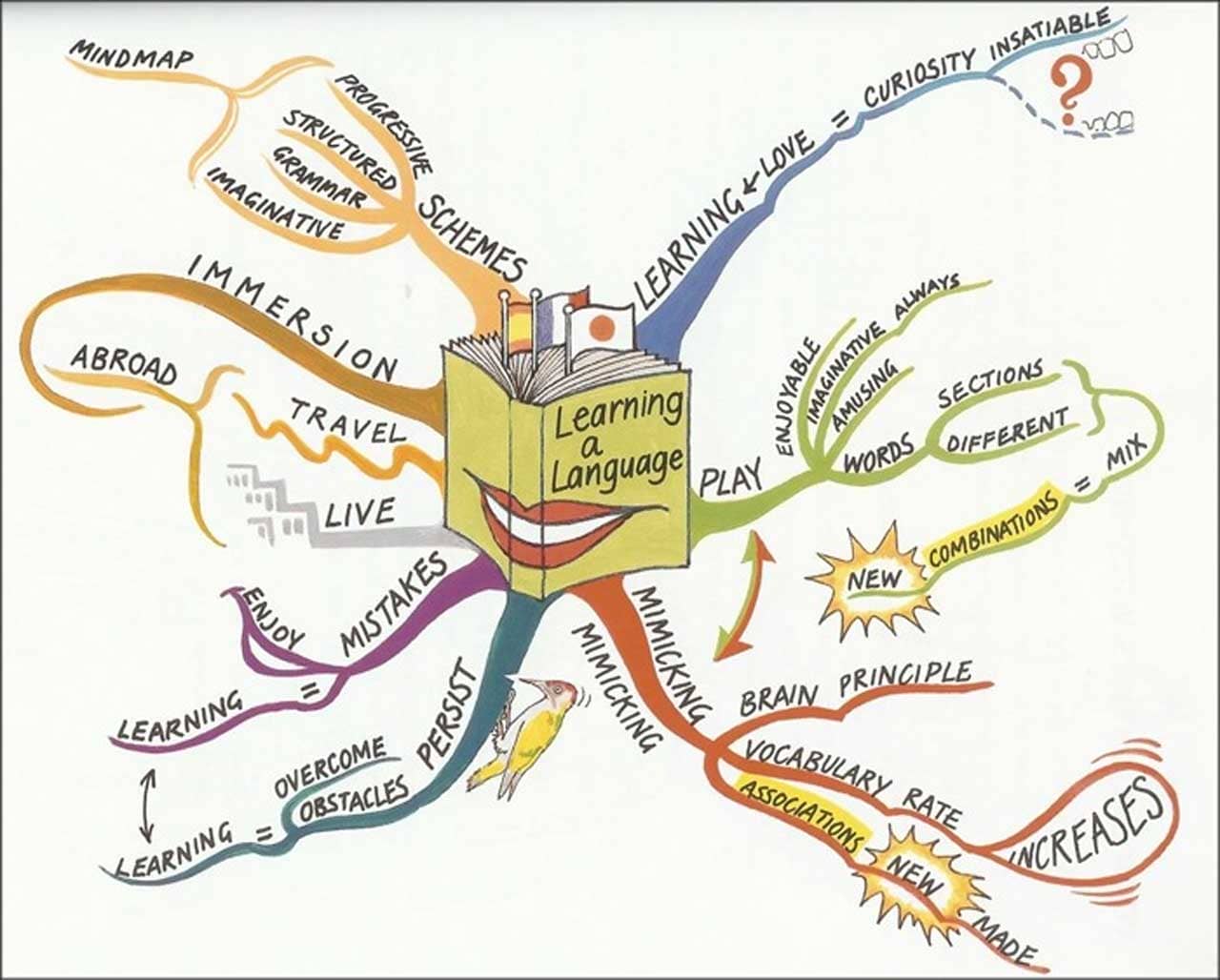

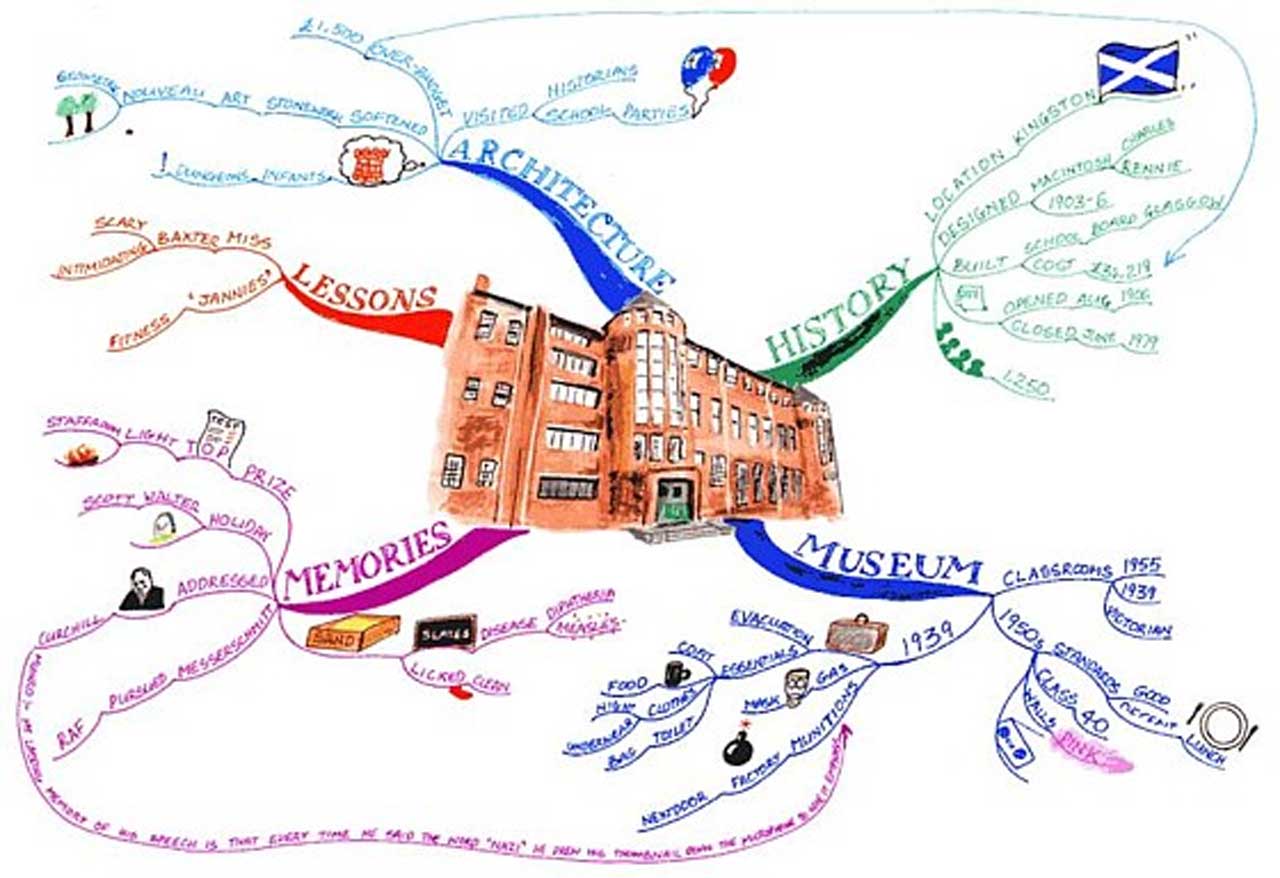

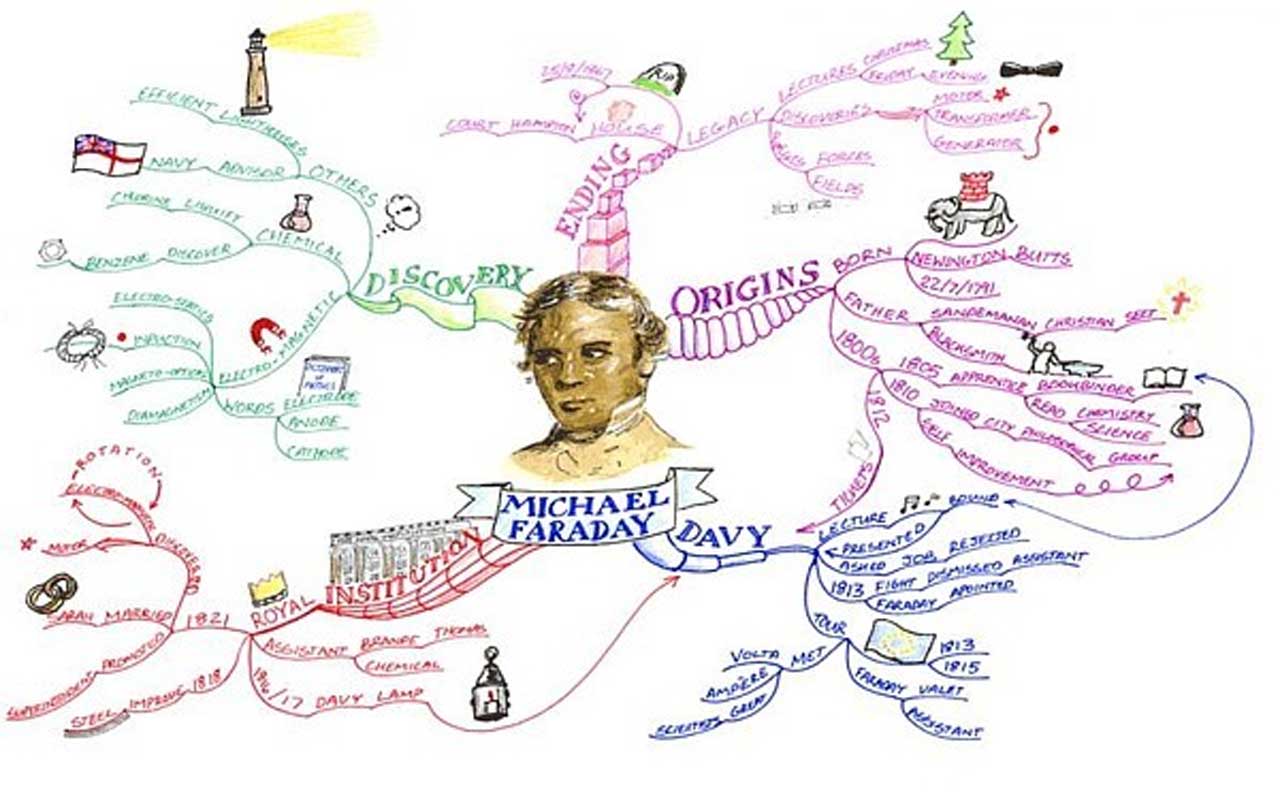

Examples of Mind Maps

To get the most benefit out of mind mapping or any kind of mind-mapping exercise, make sure your mind maps are colorful and engaging. Don’t worry: the results can look analytical and artistic at the same time.

To help you see what I mean, here are some great examples of how fun and engaging mind maps can be. Some of them look messy — but look deeper and you’ll see they are examples of detailed trains of thought.

Source: Tony Buzan Learning Center

Source: MindMapArt

Source: BiggerPlate

These fascinating examples are colorful, though in some cases, also quite visually overwhelming.

That’s why I’ve pared down my own style, and am glad I got Tony Buzan’s seal of approval after doing so:

Anthony Metivier with a Buzan-style Mind Map

But you might be asking: aren’t these the same as spider maps, concept maps , and other such visualizations?

No. There are some key differences.

Why are Mind Maps Effective?

Nobel prize winner Dr. Roger Sperry’s research proved that visual forms of note making are more effective than written methods.

He showed that the brain is divided into two hemispheres that perform cortical skills like logic, imagination, color recognition, and others. These functions work in sync when you mindmap your thoughts, creating a lasting impression in your brain.

Mind maps are effective because:

- They nudge you to ditch the usual, bullet-point style of thinking, which pushes you to use your creativity.

- They are presented in a brain-friendly format — and people can grasp the linkages quickly.

- They let you see the bigger picture.

- They keep you focused on key issues.

- They give you time for “diffuse thinking” as you pause to change colors and reflect on keywords and images.

- And, they help you retain and recall more information through patterns and associations.

Next, let’s look at why mind mapping can be beneficial.

Benefits of Using a Mind Mapping Method

Years of research have gone into testing the effectiveness of mind mapping.

In a 2005 study by G. Cunningham , 80% of the students agreed that mind mapping helped them understand science concepts better.

Paul Farrand proved the efficacy of mind mapping as a study technique and encouraged its use in medical curricula.

Mind maps are known to help you to improve your productivity at work, academic success, and even to manage your life.

Here’s how you could apply it in your day-to-day life:

- Note Taking: You can map out notes from a podcast, a project discussion, or a seminar.

- Brainstorming: Helps in real-time collaboration with your team members to make informed business decisions.

- Studying: You can summarize books.

- Presenting information to an audience: Use it to get your team’s buy-in for anything through clear narratives.

- Problem-solving: Sometimes, it helps if you map out your current situation and your desired situation separately. This will help you come up with solutions easily.

- Increasing creativity: The words, images, and colors you use let you see the information from a very different perspective.

- Planning: Plan your holiday or your next sales strategy using mind maps.

- Language learning: Use a simple, 12-point mind map to combine 12 vocabulary words with the Major System. Here’s how:

Now that you have a fair idea of mind maps, let’s understand who should use it, as well as when and how.

Who Should Use Mind Maps?

Mind maps are particularly helpful for those who:

- (Or need practice becoming more visual.

- Deal with lots of information or a project that needs more clarity.

- Need to brainstorm for ideas from others to build a bigger project or solution.

Mind mapping has also proven useful for dyslexic students and those with ADHD .

When Should You Use Mind Maps?

Create mind maps when you need to achieve some goal — to understand your course material or project better, or to assess the ideas from brainstorming sessions .

Remember — mind mapping isn’t the end goal by itself.

And don’t spend too much time perfecting it. If it takes too long, it may hamper your creative thinking.

How to Make a Mind Map

Drawing a mind map is pretty straightforward.

For example, if you want to prepare a meeting agenda take a blank page and follow these basic steps:

- Draw a bubble in the middle of the page with the title of your meeting.

- Branch out with new bubbles from the central theme, with each branch representing the topics you want to address.

- Draw lines to connect each of them to the middle bubble.

- Add new ideas starting from the general to the specific.

- Repeat this for each subtopic branching out from the topics.

What are the Rules for Mind Mapping?

Mind maps are meant to be hierarchical and show relationships among pieces of the whole.

What are the guidelines you can use?

Tips for Drawing a Mind Map

Here are some mind mapping rules to make your mind map project expressive and compelling.

- Use colors, illustrations, and pictures: Some of the most effective mind maps have more doodles and symbols than words.

- Keep the topics and sub-topics brief: Stick to a single word each, or just a picture instead of long phrases or sentences.

- Keyword for branches: Name your branches or lines using a keyword each.

- Use different text sizes and alignment: Provide as many visual cues as you can to emphasize important points.

- Use symbols: Draw symbols like arrows and shapes to classify your thoughts.

- Space it out: Leave enough negative space between your idea bubbles.

- Highlight important stuff: Highlight important branches or bubbles with borders or colors.

- Create linear lists: You can create linear hierarchies using bullet points and numbered lists.

- Mix up word sizes and fonts: Add in hierarchies of words using different font sizes to highlight their importance.

- Use varying cases: Use lower and upper cases to highlight the importance of ideas.

Every little effort you put into your mind map project will engage your brain. And, all these visual aids will make your mind map more memorable and easier to recall.

Now, do you draw mind maps on paper, or is there a diagramming tool to do it?

The answer is: both.

You can draw mind maps by hand, just like note-taking during a lecture.

Or you can use websites or mobile phone apps to do it.

Traditional Mind Maps

Nothing is as comforting as putting pen to paper when an idea strikes you. This is, in fact, the simplest way to map your ideas.

It is your personal project — your thoughts, handwriting, and your doodles. You can create it yourself or in groups on a whiteboard during a brainstorming session.

The pen-and-paper method works perfectly most of the time, but it does have limitations:

- You may not have enough space on the paper to expand your thoughts.

- You can’t make too many corrections.

- And, it may not always be presentable enough to share in a formal meeting.

The other option is to use mind mapping software — websites and apps.

Mind Mapping Software

Mind mapping apps and websites help you organize your ideas and store large amounts of data in a single location.

What makes for great mind mapping software ?

The best mind mapping tools…

- Allow you to create a wide network of ideas, facts, and connections.

- Let you make quick changes through automatic spatial organization and hierarchical structuring (particularly useful while brainstorming).

- Let you play with fonts and colors, and even drag and drop files into the mind mapping program.

Which are the Best Mind Mapping Software Tools?

Here are three of the best online mind mapping tools available today:

1. MindManager by MindJet: This tool is for business users — a professional mind map maker with MS Office integration. You could even pick a mind map template in the tool to get started.

Source: MindManager

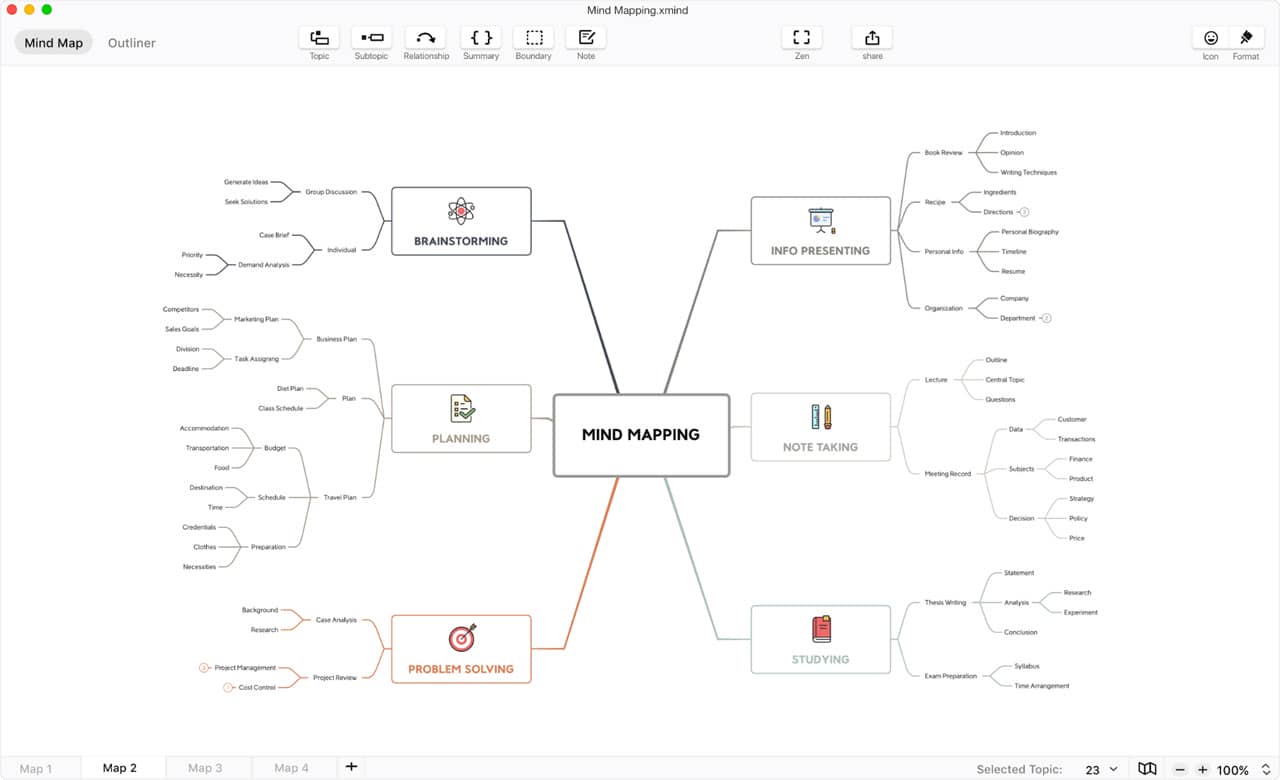

2. XMind: This mind mapping tool has a simple interface and is mainly for enterprise-level users . It lets you convert your mind maps to a Gantt chart that shows the start and end dates and progress of each task.

You can even use a countdown timer to time your sessions on this mind mapping software (this will keep you focused and will stop you from spending too much time mind mapping and brainstorming).

Source: XMind

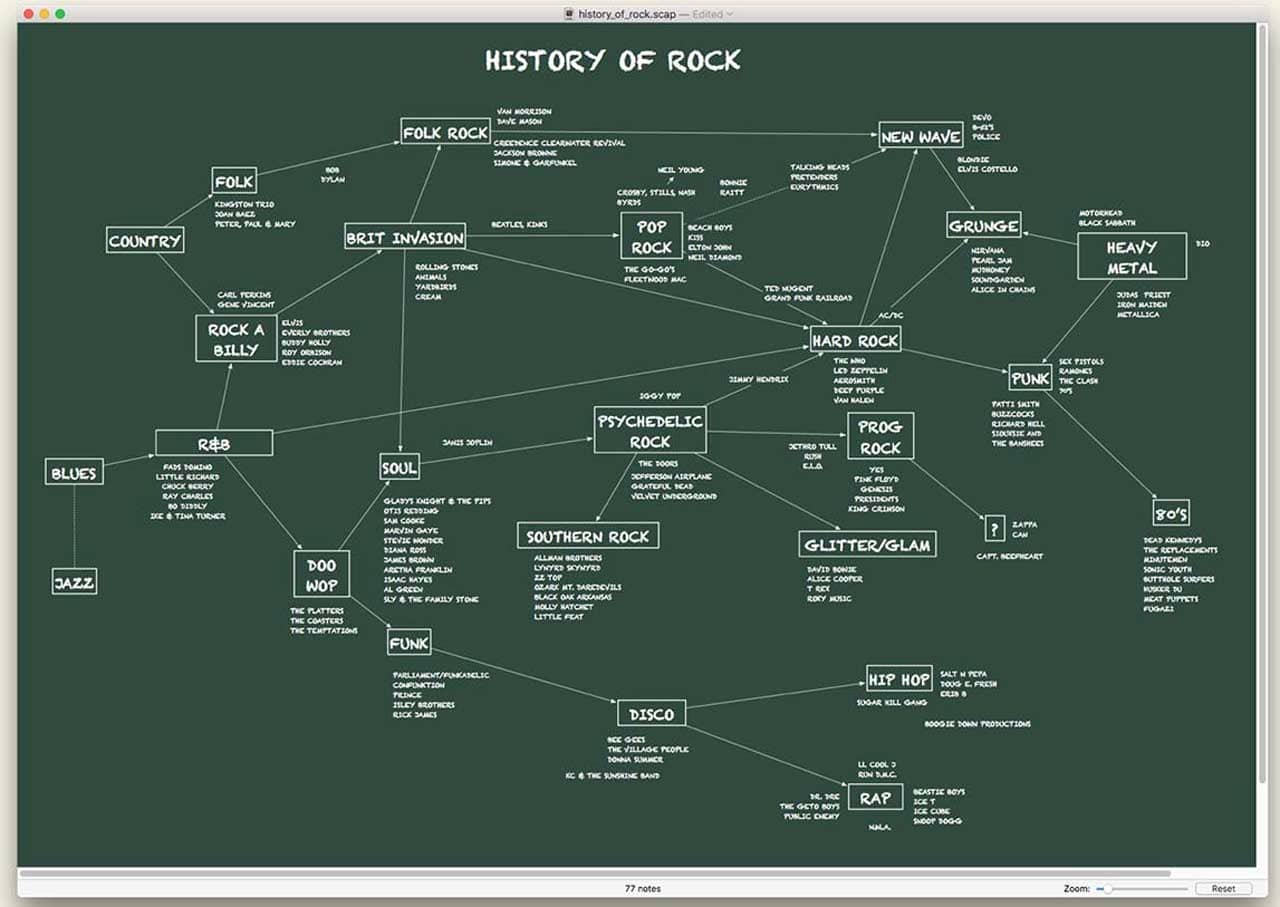

3. Scapple: This mind mapping tool was built for writers by a writers group called “Literature and Latte.” It is easy to use and comes with great features (minus embedding audio and video).

With this mind mapping application, you’re not limited to starting with a central theme. You can begin with a small idea, then work backward to reach the main idea.

Source: Scapple

You could also experiment with an open-source free mind mapping tool like FreeMind or Coggle .

The point is this: there are a lot of options. For an example of one teacher who uses software and teaches with a specific focus on personal develop is Joseph Rodrigues. Here’s one of his best:

Mind Map + Memory Palace = Magnetic Memory

A mind map is an excellent non-linear visual representation of your ideas that mimics the way your brain thinks. You can also use mind mapping for business to help you determine how the market thinks too.

Once you master it (whether you use a notebook or a mind mapping software), you’ll never go back to linear note-taking ever again. But, mind mapping alone may not boost your brainpower as much as when combined with the Magnetic Memory Method. If you need more mind map examples , we have plenty.

Ready to use this combination to fire up your memory, creativity, and learning? Sign up for my free memory improvement kit today!

Related Posts

Mind mapping improves memory and creativity. These mind mapping examples for using the method of…

You want to expand your mind but don't know how. These 15 secrets show you…

It's possible to increase your IQ. The best part is that it's easy to do…

Last modified: March 5, 2024

About the Author / Anthony Metivier

2 Responses to " What is Mind-Mapping? The Ultimate Guide to Using This Powerful Tool "

Yesssss! Mind mapping has been KEY to getting my latest writing project off the ground. Thank so much for this guide! ❤️

That’s great, Deb.

Just about every one of my book projects have also involved mind mapping. I’ve got another one that just left the first draft stage, in fact. I sometimes use additional mind maps to work out the second drafts as well.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

I accept the Privacy Policy

POPULAR POSTS

- How to Remember Things: 18 Proven Memory Techniques

- How to Build a Memory Palace: Proven Memory Palace Technique Approach

- How to Learn a New Language Fast: A Step-by-Step Guide

- Digital Amnesia: 5 Ways To Stop The Internet From Ruining Your Memory

- 15 Brain Exercises & Memory Exercises For Rapid Remembering

- The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci

- Effortless Conference Interpreting: 7 Career-Making Memory Tips

- How To Teach Your Kids Memory Techniques

- 5 Unconventional, But Proven Note Taking Techniques

Recent Posts

- Do Brain Games Work? Here’s A Better Way To Fix Your Memory

- How To Prepare For A Debate: 8 Ways To Win & Build Reputation

- 3 Polymath Personality Traits Masterful People Nurture & Amplify

- Lifelong Learning: The Benefits in Life and in Today’s Job Market

- How To Stop Losing Things: 6 Proven Tips

Pay with Confidence

Memory Courses

- The Magnetic Memory Method Masterclass

- The Magnetic Memory Method Masterplan

- How To Learn And Memorize The Vocabulary Of Any Language

- How To Learn And Memorize Poetry

- How To Memorize Names and Faces

- How to Memorize Math, Numbers, Simple Arithmetic and Equations

- How to Remember Your Dreams

Quick Links

- Testimonials

- Privacy Policy

- Privacy Tools

- Terms of Service

P.O. Box 933 Mooloolaba, QLD 4557 Australia

Memory Improvement Blog

- How to Build A Memory Palace

- Eidetic Memory

- Episodic Memory

- Photographic Memory

- Improve Memory for Studying

- Memorization Techniques

- How to Memorize Things Fast

- Brain Exercises

- The Magnetic Memory Method Podcast

- Memory Improvement Resources for Learning And Remembering

COOL MEMORY TECHNIQUES!

GET YOUR FREE 4-PART VIDEO MINI-COURSE

Improve your memory in record time! Just enter your email below now to subscribe.

- How to learn anything at lightning fast speeds

- Improve your short and long term memory almost overnight

- Learn any language with and recall any information with ease

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Educ

The effect of implementing mind maps for online learning and assessment on students during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study

Amany a. alsuraihi.

Physics Department, Faculty of Science, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, 21589 Saudi Arabia

Associated Data

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available as additional files.

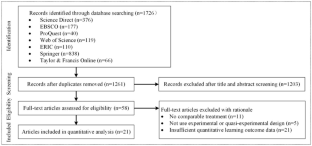

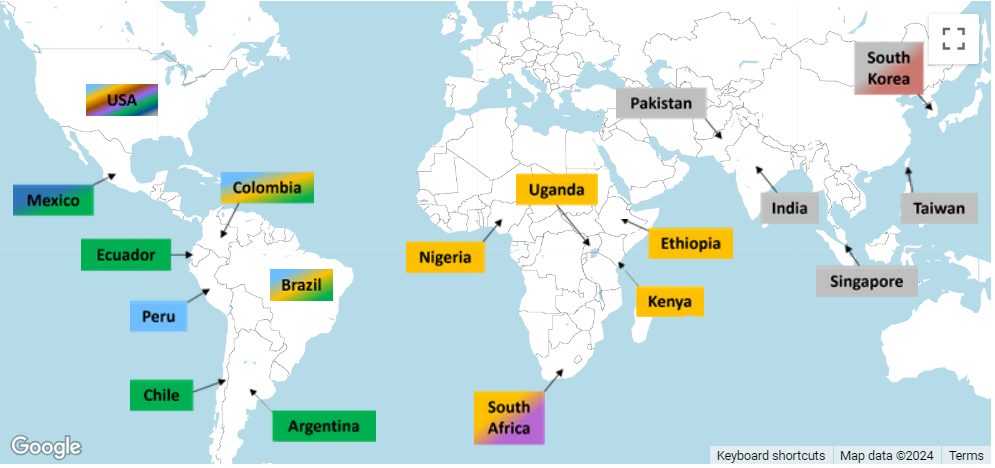

In Saudi Arabia, the sudden shift from conventional (in-person) to online education due to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic affected teaching and assessment methods. This research aimed to assess the effectiveness of mind maps in this regard, measure students’ reactions to certain educational environment-related changes caused by the pandemic, and identify skills that students perceived they gained through mind mapping.

This study employed a non-intervention (cross sectional) design. Participants were King Abdulaziz University students from two medical physics courses (second and fourth level). Data were collected twice (after the first and last mind mapping assignments), and responses were analyzed using a paired t-test. Overall student results were compared against overall student performance in the previous term using chi-squares test hypothesis testing. The data were collected and analyzed using SPSS software.

The results of the paired t-test showed no significant differences between students’ mean satisfaction in both surveys. Nevertheless, students’ responses revealed their satisfaction with using mind maps. Moreover, students believed that they gained skills like organizing and planning, decision making, and critical thinking from the mind map assignments. The chi-squares test (Chi-square = 4.29 < x 0.05 , 4 2 = 9.48 and p -value = 0.36 > 0.05) showed no differences in students’ grade distribution between the two terms of 2020 (pre- and post-COVID-19 pandemic) despite the change in assessment style post-pandemic commencement.

Conclusions

Mind mapping can be adapted as an online teaching and assessment method. Additionally, student support and education institution-level effective communication can reduce stress during challenging times.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12909-022-03211-2.

On January 7, 2020, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) was identified as the cause of a cluster of pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China [ 1 ]. Since then, millions of people globally have been infected with COVID-19, and many families have been affected. To protect against the rapid spread of the virus, the World Health Organization recommends that people should maintain social distancing, wear masks, and practice good hygiene at all times. On March 8, 2020, following these recommendations, the government of Saudi Arabia closed educational institutions, including universities and schools at all levels, to control the spread of COVID-19 and protect the population. Hence, to maintain the safety of students and school staff while continuing to provide education, the Saudi Ministry of Education [ 2 ] made a sudden switch from conventional in-person education to virtual online education via different platforms. For instance, King Abdulaziz University began using the Blackboard platform. Support including workshops, necessary learning materials, and helplines were provided to ensure a smooth transition. However, many exams and quizzes were cancelled, and lecturers were directed to assess students' progress using other methods.

In the education field, and specifically in medical education, many learning strategies and tools have been designed to enhance students’ learning experiences, such as case-based teaching [ 3 ], role playing [ 4 ], problem-based learning, discussion groups [ 5 ], didactic learning [ 6 ], concept maps [ 7 ], and mind maps [ 8 ]. Both concept maps and mind maps are excellent learning tools to enhance students’ abilities to formulate concepts, analyze data, as well as connect ideas and understand the relationships between them. They both involve visual knowledge reconstruction, are easier to follow and engage with than verbal and written scripts, and provide an interactive learning method for students. However, they have certain differences. Concept mapping has a top-down structure that begins with the main concept/idea and branches out into sub-concepts/ideas, which are enclosed in circles or boxes. Association phrases and arrows are used to demonstrate the relationship between them. The structure could be hierarchical, non-hierarchical or data-driven. Some of the drawbacks of using concept maps are their limited extensibility, low memorability due to the level complexity of certain concepts, and the medium to high level of difficulty, as it requires expertise and training to master concept maps [ 9 , 10 ].However, mind maps are easier to grasp, encourage creativity, enhance engagement, promote ownership of ideas, and involve both brain hemisphere [ 9 ]. While Eppler’s study [ 9 ] shows that combining more than one visual mapping method can be of more benefit than using individual techniques, Martin Davies [ 10 ], who studied both concept maps and mind maps, claims that the choice of mapping technique depends predominantly on the aim and purpose of its use. Therefore, in the present study, mind mapping was chosen as an online learning and group assessment tool in two medical physics courses during the sudden changes brought about by the pandemic. This occurred approximately during the mid-second term, Spring 2020.

Literature Review

The mind mapping technique was developed by Buzan [ 11 ], based on a theory inspired by da Vinci’s notes, and by scientists such as Galileo, Feynman, and Einstein. A mind map starts with the main topic represented as an image at the center of the page, then the subtopics branch out and are placed onto curved lines. A keyword or image is included on each branch to represent ideas. These ideas continue to branch out as far as is required by the subject. Furthermore, connection lines, codes, and symbols are used to connect ideas, highlight important concepts, and stimulate creative thinking [ 11 , 12 ]. Many studies have explored the benefits of Buzan’s technique for teaching and learning, such as retaining information, organizing thoughts, and developing critical-thinking skills (e.g., reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving) [ 11 , 12 ]. In a study conducted with elementary school teachers [ 13 ], teachers agreed that using mind maps in education would stimulate students’ creativity, enhance learning and memorization, and serve as a tool to assess students’ degree of comprehension for the topics being taught. Moreover, Ellozy and Mostafa [ 14 ] studied the feasibility of using a hybrid concept comprising mind mapping strategies among first-year students at the American University in Cairo and found that their technique enhanced students’ critical-thinking and reading comprehension skills, ability to engage in visualization, and imagination during learning and communicating ideas. Further, it was useful as an assessment tool for teachers to evaluate students’ systematic thinking [ 14 ]. Wu and Wu [ 15 ] showed that using mind mapping in medical education improved nursing students’ critical-thinking abilities and stimulated their eagerness to learn during their internship. This supported the findings of a previous study [ 8 ] that investigated the effectiveness of mind mapping as an active educational tool in a Nursing Management course to enhance students’ critical-thinking skills; the students’ scores were found to have improved. Mind maps were named as a factor contributing to the high-achieving medical students’ educational success [ 16 ]. Mind maps have also been used to enhance health education of patients and improve psychological well-being in cancer patients [ 17 ]. Chen [ 17 ] developed a mind map-based life review program (MBLRP), which is conducted through several sessions for the life review aspect (from childhood to adulthood, their cancer experience, and then a summary session of the life experience). Sessions use mind maps, videos and photos. Results show that the MBLRP is a promising intervention to promote psychological wellbeing among patients, while being enjoyable, feasible, and easily accepted. Another study done by Tan et al. [ 18 ] concluded that mind mapping can improve the effectiveness of health education and guidance for patients with lung cancer who were undergoing chemotherapy, where the level of perceived control improved symptom distress; the longer the period of health education, the better the effect. Yang et al. [ 19 ] investigated the effectiveness of using mind mapping as a health education tool for children with cavities who were in extended care, as well as their parents. The results show an increase in child and parent compliance with health education, which is evident from an increase in cavity knowledge and more follow-up visits to the dentist. Mind map have also proven effective as a language learning material for students; for example, Petrova and Kazarova [ 20 ] discussed the feasibility of using mind maps as a teaching and learning tool in foreign language acquisition, as it helps students to be independent learners and solve diverse problems. Kalizhanova et al. [ 21 ] created a trilingual e-dictionary using a mind map program for high school students, to teach them biological terms in Kazakhstan. Furthermore, Alahmadi’s [ 22 ] study showed a significant improvement in vocabulary acquisition by students who used mind maps as a learning strategy for English language vocabulary as a second language. Mind maps were also used in science and engineering as educational material, learning exercises, and a critical thinking tool for collaborative and independent learning. Gagic et al. [ 23 ] used mind maps to teach physics to primary school students; results showed an increase in student achievement and a decrease in the mental effort necessary to study physics, when compared to conventional teaching and learning methods. In the teacher education program for mathematics, Araujo and Gadanidis [ 24 ] have developed a theory to promote mathematical and pedological knowledge construction by applying an online collaborative mind mapping exercise to two educational courses: computational thinking in mathematics education and mathematics teaching methods. In a study conducted by Allen et al. [ 25 ], mind maps were used in flipped learning activities in a chemistry lab, which included students with special needs. Students were reflective on their learning, collaborative with their peers, and engaged with each other during the activity. This enhanced their critical thinking, deepened their knowledge, and strengthened their interpersonal skills. In the field of engineering, Lai and Lee [ 26 ] show that mathematical engineering students’ achievement levels increased by using mind maps, while their cognitive load reduced. Hence, using effective learning and teaching techniques like mind maps reduces students' cognitive load. Chen et al. [ 27 ] have studied the collaborative behavior of engineering students while doing brainstorming activities using mind maps. Their study analyzed the change in students’ behavior during mind map tasks and issues that arose to implement in the design of digital mind map tools. Selvi and Chandramohan [ 28 ] have used mind mapping technique in collaborative tasks for a mechanical engineering course, which increased students' academic achievement and motivation to learn. Here, using mind maps in collaborative and interactive learning settings enhanced students’ ability to recall technical terms. To the author’s knowledge, mind maps have not yet been investigated in a medical physics course. However, previous studies done on mind maps for medical, science, and engineering courses showed that they are on the same level as medical physics courses in terms of their cognitive load. Hence, it should be a suitable learning and assessment tool during the pandemic. Therefore, this study aims to assess the effectiveness of mind mapping as a learning and assessment tool for medical physics students, while under stress from the COVID-19 pandemic and while experiencing the related educational mode changes. Accordingly, the following were assessed:

- Student satisfaction with the provided information on mind mapping and associated course assignments.

- Effects of changing the assessment style due to switching from on campus to online classes in relation to students’ satisfaction.

- Student satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool and student perceptions of the skills gained from the assignment.

To evaluate these objectives, this study developed two online surveys (Surveys 1 and 2) It hypothesized that students could improve satisfaction by practicing mind maps and that academic achievement would be unaffected by the pandemic compared to previous pre-pandemic commencement results. This study could set the basis for future studies when adapting mind maps as an online learning and assessment method and presenting a measure for students’ satisfaction and perception on the technique.

During the online teaching period from March through the end of April 2020, three mind map assignments, one set of critique questions, and two surveys were given to students in two different courses as an alternative teaching and assessment method. These three assignments covered important topics in both courses, as the grading system was changed by the Ministry of Education due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, mind mapping assignments were chosen as an alternative, to enhance students’ learning and memorizing and for use as an assessment tool. Performing this assignment as part of a group in such sudden and stressful circumstances could help students acquire soft skills, such as conflict resolution and time management. Moreover, results of total students’ achievement in these courses in the second term were compared with students’ achievement level in the first term of 2020, prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, using hypothesis testing.

The sample chosen for the study was the cluster sampling from the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Jeddah City, King Abdulaziz University, Department of Physics, Female Campus. Participants were medical physics students. The sample includes only female students, as the female and male campuses are separated at Saudi Arabian Universities. The study was conducted with female students enrolled in two separate medical physics courses taught by the author of the study: 1) health physics, a second-level introductory course, and 2) magnetic resonance and medical imaging (MRI), taught to fourth-year students. The sample of the study was 55 students in total, from both courses. Students were verbally informed that 1) survey participation would be voluntary, 2) responses would be anonymous, and 3) non-participation would not affect their course grades, as no identifying information would be collected. Thus, participation was considered to imply consent.

Assignments

To perform the mind mapping assignments, students were first assigned randomly to groups of 3–6 students using the Blackboard system. There were 11 students in the MRI course; thus, students were divided into 3 groups. There were two classes for the health physics course, one with 14 students and one with 30 students, who were divided into 3 and 5 groups, respectively. Thus, 55 students in total were given three mind map assignments that covered the most important course topics. Each mind map covered a section of the course that students had already completed.

All mind mapping assignments were posted on Blackboard with instructions for guidance. Students also participated in a short session in which the assignments were explained, with an emphasis on the resources provided to assist them and the grading style (rubric). Students were directed to engage in self-learning on the Blackboard platform by using the different posted YouTube video instructions and resources in Arabic and English on how to create a mind map. Students were also given the freedom to choose and download one of the three online mind mapping software apps: MindMaster [ 29 ], MindMeister [ 30 ], and XMind [ 31 ]. Online materials on how to use each tool were also posted for students on Blackboard.

Based on concept map assessment criteria published online, the author designed a mind map rubric to assess students’ accomplishments (see Appendix A in Additional File 1 ; [ 32 , 33 ]). After each mind mapping assignment, students received feedback on their work on Blackboard based on the rubric.

After these assignments were completed, a fourth assignment was posted for students on Blackboard. This assignment included mind maps that the students had worked on in each course: 23 for the health physics course, 8 for the MRI course, and a set of 3 questions. The mind maps with the highest scores were excluded from this assignment. Students were directed to choose a mind map that they did not work on and answer the three critique questions. The questions were as follows: “Does this mind map include all ideas and concepts related to the subject? If not, state what is missing? State only one aspect that is missing;” “What are the aspects that you like most about the mind map (e.g., in terms of ideas, links and connections used, supporting evidence, information used);” and “Provide at least one suggestion to improve this mind map.” The motivation behind this assignment was to encourage students to constructively critique their peers’ work. Therefore, there were no wrong answers to 2 out of the 3 questions, unless students failed to spot their peers’ mistakes regarding missing information on the mind map. The results of this assignment are not shown in this paper.

To address study objectives, a survey was distributed online to students in both courses after the first assignment (Survey 1), Appendix B in Additional File 1 . It was divided into three main sections: student satisfaction with the information regarding mind mapping and associated assignments; effects on students regarding the change in assessment style due to COVID-19 control measures and the transition to online education; and student satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool and the skills gained from the assignment. Responses to the questions in each section were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree.” Additionally, an extra question on the skills students believed they acquired when working on their assignments was included.

After submitting the last assignment, the same survey was posted for students again with an extra open-ended question: “After finishing all three mind mapping assignments, what do you think are the positive and negative aspects of the assignments?” “Do you have any suggestions about them?” (Survey 2). This was done to compare students’ responses from both surveys and measure changes in their perceptions regarding mind mapping through their openly shared views on the assignments.

Statistical analysis

To address the research questions, students were asked to complete a survey after the first assignment and again after the last. The data collected from students for first survey S1 is available in Additional file 2 while the data collected from the second survey S2 is available in Additional file 3 . Students’ responses to the two surveys were then compared, as were their achievement levels in the first term before the COVID-19 pandemic and the second term after the pandemic began. The data for students’ academic achievement in first and second term can be found in Additional file 4 . Both Survey 1 (S1; N = 53 students) and Survey 2 (S2; N = 45 students) had one independent variable—medical physics students (health physics and MRI). However, the dependent variable for S1 represented students’ answers related to the survey’s objectives, while for S2, they represented students’ answers related to the survey’s objectives and to an open-ended question. To measure the internal consistency of the survey items, Cronbach’s Alpha was used. It creates a measure of reliability for the survey items and how closely related a set of items within a group are. Factor analysis was used to test the validity between the survey questions in subsites. If the value is less than the absolute value of 0.4, it is inconsistent and saturated. This analyses the relationships between the set of survey questions that are grouped per survey aim (subset), to determine whether the participant’s responses on different questions per survey aim (subsets) relate more closely to one another than to other survey questions [ 34 ].

Responses to positively worded questions were collected and coded as follows: strongly agree = 5, agree = 4, neutral = 3, disagree = 2, and strongly disagree = 1. However, to maintain consistency, for Questions 1 and 2 in the second section of the survey (Appendix B in Additional File 1 ), the negatively worded questions were taken into consideration, and responses to these were reverse coded. The survey data were analyzed using the SPSS software package. Frequencies (N), percentages (%), means (M), and standard deviations (SD) were used to analyze the response. Responses to the open-ended question from S2 were low (only 19 response) and hence not statistically significant. Therefore, the coding technique was used, and similar answers were added into the same category. Answers were categorized as positive, negative, and in the form of suggestions for mind mapping assignments.

The means of both surveys' first and second objectives were tested for their significance of difference using a paired samples t-test. Finally, a chi-squared test was used to determine any statistically significant differences between student achievement levels in the first term (pre-COVID-19 pandemic) and the second term (post-COVID-19 pandemic commencement).

Responses from the questionnaires of S1 and S2—which were provided prior to the final exams after students submitted all assignments and were given feedback on their work and scores based on the rubric—were analyzed. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.829 and 0.775 for S1 and S2, respectively, indicating a relatively high internal consistency for both surveys. Table Table1 1 show the result of factor analysis for both surveys S1 and S2. Results show good internal validity values, except for Question 6 in S1, while showing good internal validity for S2. This could be due to the sample size, as the larger the sample size, the better the statistical power, which reflects on factor analysis values [ 34 ]. As shown in Table Table2, 2 , the highest responses for S1 and S2 were from the health physics course, which made up 81% and 80% of the responses, respectively. The remaining 19% and 20% responses in S1 and S2, respectively, were from the MRI course students. This similarity in results was expected, as more students were registered for the health physics course.

Factor analysis with principle component analysis for Survey 1 and 2

Number of responses in survey 1 and 2

S1: Survey 1, S2: Survey 2, MRI – JAR: Magnetic Resonance and Medical imaging course, course code: JAR, HP: Health Physics Course, course’s codes: GAR and IAR

Table Table3 3 provides detailed information on the mean, standard deviation, and trend for responses to each question regarding student satisfaction with the information provided to them about mind mapping and the associated course assignments in S1 and S2. The overall mean frequency for responses in S1 and S2 was 3.38 and 3.53, with a trend of “neutral” and “agree” responses, respectively. Thus, students indicated overall satisfaction with the information provided about mind mapping and the associated course assignments in S2. Additionally, S2 results showed that 60% of students had not been previously trained on mind mapping (Q1), while 26.7% of students had used mind maps in their studies before. Regarding the usefulness of the supporting information provided (Q2) and recommended instructional videos (Q3), 66.7% and 57.8% of students found this to be useful, respectively, while only approximately 4% and 18% did not, respectively. Most students (73.4%) agreed that the assessment method (rubric) the instructor provided was clear (Q4), while 13.4% did not understand the assessment method.

Student satisfaction with information provided about mind mapping and assignments

S1: Survey 1; S2: Survey 2

Table Table4 4 provides detailed information on the responses to each question regarding the effects of changing the assessment style due to COVID-19 control measures and switching from on-campus classes to online virtual classes and students’ satisfaction levels. S1 and S2 results show a mean score of 3.06 and 2.98, respectively, indicating a generally neutral response.

The effect of changing assessment styles due to COVID-19 spread control measures and the transition to online education on students’ satisfaction

* To maintain consistency with analysis as reverse coding in Likert scale for Q1, Q2 was used with negative wording ("not stressful" here). S1: Survey 1; S2: Survey 2

As shown in Table Table5, 5 , student satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool and the skills they gained from the assignments had a mean frequency of 3.75 and 3.56 in S1 and S2, respectively, with a general trend of “agree” responses; this reflects a consensus among students regarding their satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool. In S1 and S2, approximately 64% and 53.4% of the students agreed that using mind maps was beneficial to their learning in and understanding, while only 15% and 9% believed it was not, respectively (Q1). Furthermore, 69% of students agreed that working on the mind maps helped them recognize and identify themes in the lectures, while 9% did not in both S1 and S2 (Q2). In addition, when students were asked if using mind maps helped them gain a deeper understanding of the subject they were studying, 59% in S1 and 58% in S2 agreed that it was beneficial to them, while 21% in S1 and 18% in S2 did not find it useful (Q3). Regarding working on the mind mapping assignment in groups, 51% and 42% of students agreed they had gained new skills, compared to 26% and 31% who were not satisfied with their group in S1 and S2, respectively (Q4). However, when students were asked if they would continue using mind maps in their studies in S1 and S2, 68% and 60% stated they would, while only 19% and 16% reported they would not, respectively (Q5).

Students’ satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool

Figure 1 summarize students’ responses in S1 and S2, regarding the skills they perceived themselves as gaining by participating in the mind mapping assignments. Student responses in both surveys suggested that the top skill gained was organizing and planning (S1: 30%; S2: 27%), followed by decision-making skills (S1: 18%; S2: 22%). However, in S1, the proportions of students who gained problem-solving (13%) and persuasion and influencing skills (12%) were almost equal, followed by 11% of students gaining critical thinking skills. Conversely, in S2, nearly an equal proportion of students perceived gaining critical-thinking (14%) and problem-solving (13%), followed by 9% of students gaining persuasion and influencing skills. Finally, student responses in both surveys reported that conflict-resolution (S1: 9%; S2: 8%) and feedback (S1: 7%; S2: 7%) skills were gained the least.

Bar chart representing students’ perceptions in Survey 1 and 2 regarding each skill gained during their group work on the mind mapping assignment

In the open-ended question added to S2, students reported the following responses regarding the assignments: 1) positive aspects: they learned new skills, better understood the course, learned in groups, and gained independent learning skills while studying; 2) negatives aspects: shorter submission deadlines, difficulty in group-work for some students, and challenges in identifying key concepts; 3) improvements suggested: allowing students to choose their group members and providing a practice session for students before the first assignment is posted on Blackboard. Figure 2 shows the improvements in students’ results across all three mind maps.

Improvements in students’ average scores out of 12 in both courses with each assignment

Students’ satisfaction with mind map assignments and comparison of students’ academic achievement in the current (after COVID-19 pandemic started) and previous term (before COVID-19 pandemic)

The paired samples t-test showed no significant difference between students’ mean satisfaction in S1 and S2. This indicated a lack of post-S2 improvement in students’ satisfaction. For the first objective, a paired samples t-test was performed on students’ average satisfaction in S1 (M = 3.38, SD = 0.85) and S2 (M = 3.53, SD = 0.81), with information regarding mind mapping and associated course assignments. However, no significant differences were found in students’ satisfaction. For the second objective, students’ average responses regarding the effect of changing assessment styles and the transition to online education on students’ satisfaction were compared between S1 ( M = 3.06 , SD = 0.92) and S2 (M = 2.98 , SD = 0.95 ) S2, and the results indicated no significant differences in students’ satisfaction for this objective. Similarly, no significant differences were found for the third objective, between students’ responses regarding satisfaction with using mind maps in S1 ( M = 3.74 , SD = 0.95) and S2 ( M = 3.56 , SD = 0.77 ) .

Figure 3 shows a normal distribution for students’ grades in the first and second semesters in both the health physics and MRI courses. The result of a chi-squares test shows that there are no differences in students’ grade distribution between the two term of year 2020, before and after COVID-19 pandemic started. Hence, chi-square = 4.29 < x 0.05 , 4 2 = 9.48 and p-value = 0.36 > 0.05 support hypothesis H 0 , where H 0 means no relationship between students’ academic achievement and term, where grades are independent of the term, while H 1 posits there is a relationship between student academic achievement and term, where grades are dependent on the term.

Grade distribution for students in the two courses during the first and second terms in the academic year 2019–2020

This study investigated the use of mind maps as a learning and assessment tool for medical physics students at KAU under the stress of the COVID-19 pandemic and a sudden switch in teaching mode from on-campus to online classes. Two surveys, one directly after the first mind map assignment and the other just before the final exam, were distributed to students, to assess student satisfaction with the information provided on mind mapping and the associated course assignments, effects of changing assessment styles due to COVID-19 control measures, switching from on-campus classes to online classes, student satisfaction levels, student satisfaction with using mind maps as a learning tool, and the skills gained from the assignments.