- help_outline help

iRubric: Contemporary Artist Research Project rubric

- Arts and Design

- Communication

- Engineering

- Foreign Languages

- Physical Ed., Fitness

- Political Science

- Social Sciences

- Presentation

Rubrics for the Art Teacher

Because art teachers measure student skills using independent judgment, they need another method to grade student work. Performance-based assessment has been shown to be much more effective in evaluating student performance. Art teachers have always been ahead of the game with performance-based assessments by using portfolios.

Creating and Scoring Rubrics

Pertinent links.

Students and Teachers Alike Can Benefit from Rubrics Creating Rubrics by Teachervision Kathy Schrock's Guide For Educators - Rubric information. Kathy has retired the site so this is the archive. Rubrics - a page of resources by Shambles.net Sample Rubrics by Rubistar Scoring Rubrics - [Archive] A Harvard article Teacher Created Rubrics - [Archive] This page includes cooperative learning rubrics, writing rubrics, art rubrics, and more. Understanding Rubrics

Rubric Templates & Generators

IAD's Lesson Plan Rubric Templates

Generic Rubric Template [Archive] General Rubric Generator iRubric from Rcampus Rubistar - the most used rubric creator on the web teAchnology - A page of links to rubric makers

Art Rubric Samples

IAD's Rubrics

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | ADVERTISE | NEWSLETTER | © Incredible Art Department

Popular Pages

- Sample Art Rubric - Middle School/High School

- Basic Elementary Art Rubric

- Art Rubrics - Files - Lesson Plans - Year Plan

- Art Education - Files for Art Teachers

- Art Teacher Assessments

- Art Toolkit Home

- Art Activitites

- Art Assessment

- Art Community

- Best Practices

- Brain Research

- Common Core Art

- Art Contests

- Art Curriculum

- Classroom Discipline

- Flipped Classroom

- Free Art Things

- Art Instruction

- NCLB & the Arts

- PBIS & the Arts

- Art Rubrics

- Special Education

Stay In Touch

- Art Lessons

- Art Jobs & Careers

- Art Departments

- Art Resources

- Art Teacher Toolkit

- Privacy Policy

- Skip to main content

- Skip to quick search

- Skip to global navigation

- Return Home

- Recent Issues (2021-)

- Back Issues (1982-2020)

- Search Back Issues

Don’t Box Me In: Rubrics for ártists and Designers

Permissions : This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy .

Two faculty developers at a professional art and design university were met with uneasy faculty attitudes toward grading when they opened their CTL 13 years ago. Conversations revealed that the faculty artists and designers suspected that grading would somehow shatter the fragile muse of creativity, which is so central to the processes of producing art and design. The developers’ quest for transparent, consistent grading, and assessment practices resulted in an approach to rubric creation that taps into artists’ reverence for the critique. This narrative account reveals how the approach allowed an interactive introduction of rubrics as teaching tools, ensured their use was rooted in the familiar pedagogy of art critique, and treated rubric assessment as an integral component of the teaching and learning process. The narrative culminates in the presentation of data that confirms the value of high quality rubrics to the teaching and learning of art and design, and it specifically confirms that such rubrics rarely squelch creativity. The approach and research can inform assessment—and teaching—practice for teaching artists or educators in other creativity driven fields.

Keywords : assessment, faculty development, teaching and learning, accountability

Introduction

“You can’t really grade art.” In 2003, when we opened the Office of Faculty Development, this was instructors’ most common response to our prompt, “Tell us about how you grade your students.” Follow up conversations revealed faculty members’ deep skepticism that grading could ever foster creative work rather than smother it. Grading was perceived as a necessary evil, not an integrated part of the art and design teaching and learning process. We both had entered faculty development from student academic support and ESL teaching and had witnessed from the students’ perspective the confusion that could arise from unpredictable grading practices. We had also witnessed our art faculty engaged in the rigorous assessment and feedback practices that are always part of their critiques, the signature pedagogy of art instruction. Our experiences told us that this declaration, “You can’t really grade art!” could not be fully true, but there was clearly a disconnect in the faculty artists’ perception of critique and grading practices. We knew that instructors owed it to their students to be transparent in their grading and feedback, but we did not want to be the ones responsible for “breaking creativity” at a dedicated art and design school by convincing our instructors to grade in ways they were not used to.

Today, after 13 years of conversation, investigation, and research about assessing art and design, grading rubrics have become integral to teaching and learning at The Academy of Art University (AAU), and they are highly formalized in many core courses. We have found that students and instructors perceive that high quality grading rubrics (introduced as teaching tools, rooted in the critique, and treated as part of the teaching learning process) support teaching and learning in art and design and that they do not destroy creativity, as once feared.

The quantitative results of our study are compelling, but they cannot be understood out of context. Rubrics in higher education vary so tremendously in format and application that our data about their effectiveness makes little sense without an account of the 13 year process that resulted in our institution’s current definition and approach to rubrics. In fact, this process itself—the story from our dual perspectives as on the ground educational developers responding to campus initiatives and as researchers maintaining some objective perspective on our situation—is as important as the final data. While we present the narrative overview of our CTL’s rubrics journey as the “preliminary methodology,” which leads to our quantitative research, the process is itself a result of this work.

It is our hope that this paper will help faculty developers and others working with instructors in creative fields to be able to productively discuss the potential role for rubrics in teaching and learning. We also hope that the framework we offer might guide others’ efforts toward creating quality grading tools and processes that are rooted in strong art and design pedagogy.

Literature Review

We have drawn upon the literature of several fields to contextualize this work. The varied disciplinary perspectives of arts assessment, creativity studies, art and design pedagogy, assessment, motivation, SoTL in higher education, and primary education (since rubrics and arts education are both more prevalent in K 12 education) have all helped us articulate and understand the challenges and benefits of rubric implementation.

The relationship between creative pursuits, such as visual arts and formal academic assessment practices, is an uneasy one. Elkins (2001) concluded that “it does not make sense to try to understand how art is taught” (p. 90). He describes teaching art as a massive cave that is “best left as is—nearly inaccessible, unlit, dangerous, and utterly seductive” (p. 91). The mysterious, unknowable quality he evokes is similar to several of the persistent societal beliefs about creativity described (and largely debunked) by Sawyer (2012), e.g., that creative ideas emerge mysteriously from the unconscious and that creativity is more likely when you reject convention. Chase et al. (2014) note that faculty in arts disciplines are “hesitant to translate their native evaluative techniques into the language of assessment and engage in systematic analysis of student learning” (p. 2). Applying analytical tools (assessment) to creative pursuits might, the reasoning seems, sap or even destroy art of its joy or beauty.

While the terms assessment and grading are anathema to some teaching artists, the concept of assessment is and always has been an integral part of an arts education. It is inherent in the critique, the time honored backbone of studio pedagogy (Klebesadel & Kornetsky, 2009; Shulman, 2005). Critiques require of students and faculty an iterative process of observation, reflection, and verbal articulation in a group setting (Motley, 2015). Contrary to examples of harsh critiques in pop culture (see any number of reality television programs on subjects ranging from cooking to singing), the goal of the critique is not a verbal thrashing but rather a conversation about the quality of the work to foster to deeper learning. In a typical critique, students share the latest version of their work with the whole class, often accompanied by evidence of process and research in the form of thumbnails, mood boards, or reference images. Instructors facilitate the critical discussion about each individual piece of work. Students’ research, thought, or work processes may surface as a part of the critique in a manner described well by Rockman (2000): “…[A] critique is not simply a forum for praise and admiration, but more importantly an opportunity to learn about how to make their work the best that it can be” (p. 222). The tone can be quite collegial, even when the feedback is tough. Critiques are used both formatively and summatively to identify both positive and negative traits of a piece (or its underlying thought and production), with the chief goal of understanding the work better or improving upon it.

In practice, the critique sometimes fails to meet the ideal described above, and it can be damaging to students’ perceived progress, especially when the feedback is grounded in the instructor’s personal stylistic preferences (Smith, 2013) or when the “the professor functions as the almighty one, damning some works while glorifying others as though he or she is God, and this word is on high” (Barrett, 2000, p. 33). Assessment perceived to be unrelated to the quality or quantity of their work, and evaluative of students’ personal worth and potential, can also be damaging (Smith, 2013).

Many useful frameworks for creativity have been applied to assessment in academic settings. De la Harpe and Peterson (2008) provided a scheme for holistic creative assessment, which includes an explanation of 11 indicators that frequently come up in creative disciplines (person, product, process, content knowledge, hard and soft skills, technology, learning approach, reflection, professional practice, and collaboration). Chase et al. (2014) described a number of frameworks for program level assessment in creative disciplines, mostly based on either Rhodes’ (1961) 4Ps Model of Creativity, which defined creativity as comprised of person, product, process, and “press” or environment, or Eisner’s (1976) Connoisseurship Model, which relied on the evaluator’s expertise and ability to offer clear criticism. These models provide valuable organizational schemes for program assessment, but they are abstract and inaccessible to individual teaching artists and designers in their daily struggles with grading assignments.

Rubrics hold potential for helping faculty artists translate their existing critique pedagogy into transparent assessment tools. Stevens and Levi (2005) framed rubrics as “part of a major shift, a major redistribution of power, in how academe defines and controls education” (p. 187), giving students the power of access.” Furthermore, they asserted that “rubrics are a guide to the culture and language of academe” (ibid). Similarly, Connelly and Wolf (2007) described “a responsibility to make explicit the various assumptions and expectations in art school or the academic art department” (p. 288). Borgioli’s (2011) guidelines on quality rubrics emphasized that rubrics should be about the work (rather than the person), and she emphasized that the work should consist of authentic tasks that have value outside of the school context rather than academic tasks whose purpose is pleasing the teacher.

Some artist educators championed the benefits of having introduced rubrics into their teaching (Connelly & Wolf, 2007; McCollister, 2002; Popovich, 2006). These benefits include promoting consistency and clarity, providing language for assessing process and product, and revealing internalized knowledge and habits (which may not yet be present among learners, despite faculty assumptions). While these practitioners all describe rubrics’ potential and benefits, the actual sample rubrics they provide vary greatly in how (or whether) they address process versus product. Lindström (provided separate process and product rubrics in his study, which analyzed the progression of visual skills and creativity in Swedish pre K to secondary students. The clarity of the wording, levels of achievement described, and the specificity of the products being assessed diverge among all of these examples.

Chase et al. (2014) noted that improved teaching and learning should be the ultimate goal of arts assessment, but other scholars cautioned about detrimental effects that rubrics can have on teaching, learning, and creativity. These warnings stem from imposing “one size fits all” rubrics on instructors (Kohn, 2006; Mabry, 1999) or from striving to create completely objective rubrics. Gibbs and Simpson (2004) observed that “[t]he most reliable, rigorous and cheat proof assessment systems are often accompanied by dull and lifeless learning that has short lasting outcomes—indeed they often lead to such learning” (p. 3). Wiggins (2012) cautioned that if students perceive rubrics to hamper creativity, “[t]hat can only come from a failure on the part of teachers to use the right criteria and multiple and varied exemplars. If rubrics are sending the message that a formulaic response on an uninteresting task is what performance assessment is all about, then we are subverting our mission as teachers” (para 11).

In visually oriented disciplines, in addition to rubrics, multiple and varied exemplars are key to student learning. McCollister (2002) stated that students need to view and contextualize their peers’ work before they can make sense of their own possibilities, choices, and solutions. Providing a range of (visual) exemplars that demonstrate a variety of approaches to a given task can help students explore untapped possibilities and shed new light on their own efforts.

While a general cultural resistance among faculty artists toward codified assessment exists, research and published experiences in the literature make a plausible case for the thoughtful integration of rubrics in a visual arts higher education classroom.

Preliminary Methodology

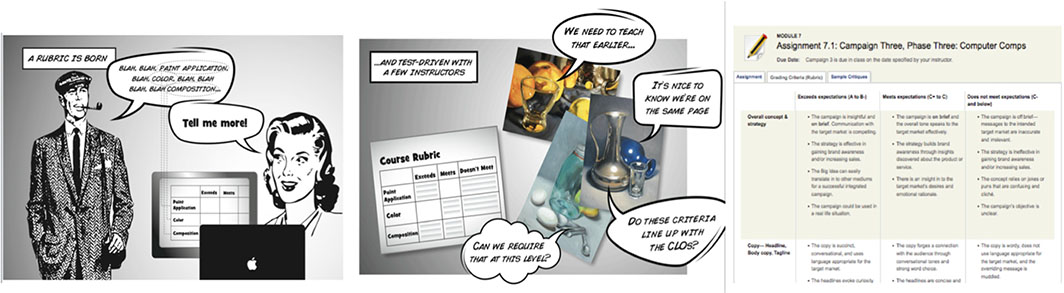

The rubrics journey begins: 2003.

We had witnessed hundreds of critiques by the time we opened our CTL in 2003. So, when an instructor who had just delivered a detailed critique would say “you can’t grade art,” we were perplexed that they perceived the practices of grading and critique as so separate. In our appeal to bridge this gap between critique and grading practices, we, as educational developers, began to prompt faculty to tell us about their students’ work. Instructors would then identify the criteria that they valued, as well as common pitfalls, in student work that ranged from the two dimensional and traditional (such as painting and posters) to three dimensional or digital (package design, auto modeling, animation rigging, and web design). As we strove to articulate and transcribe the feedback patterns that emerged in critiques, we found ourselves creating more and more assessment tools that looked like rubrics. Soon, we began to offer explicit guidance on rubric development through consultations with individual faculty and in sessions at in house biannual conferences. We also consulted with the Foundations director, who sought to reduce grade complaints in her department by introducing rubrics at the course level.

The number of instructors who embraced rubrics grew slowly but steadily over the first five years of our CTL’s existence. However, there were still many instructors who voiced trepidation that grids of evaluative language would extinguish any creative spirit in their classrooms. Wanting to quell their misgivings and assure ourselves that we were not doing harm by imposing rubrics into disciplines as varied as fine art and industrial design, we applied our researcher lenses and embarked on a series of our own internal studies.

Early Research

In 2006, informal interviews with instructors who reported using rubrics confirmed that they perceived rubrics to be helpful but mostly for focusing their own teaching. We were surprised that some of the greatest faculty proponents of rubrics at that time did not even share them with their students. While we recognized the value of the rubric creation process in helping instructors feel more confident and focused in their teaching, we also felt strongly that we needed to keep students in mind as the ultimate audience for, and beneficiaries of, rubrics.

In 2008, we conducted a Student Perceptions of Rubric Effectiveness (SPORE) survey at our institution, which confirmed that the majority of students found rubrics to be helpful to their learning (see Results and Appendix A). With the 2008 survey, we realized there were more rubrics than we had known of at the university. While we were heartened that instructors were embracing rubrics and making them their own, we suspected that some “rubrics” might not appear as such to an outside eye. We began to wonder just how diverse this tool had become and whether we could begin to identify some best practices for rubrics in our context.

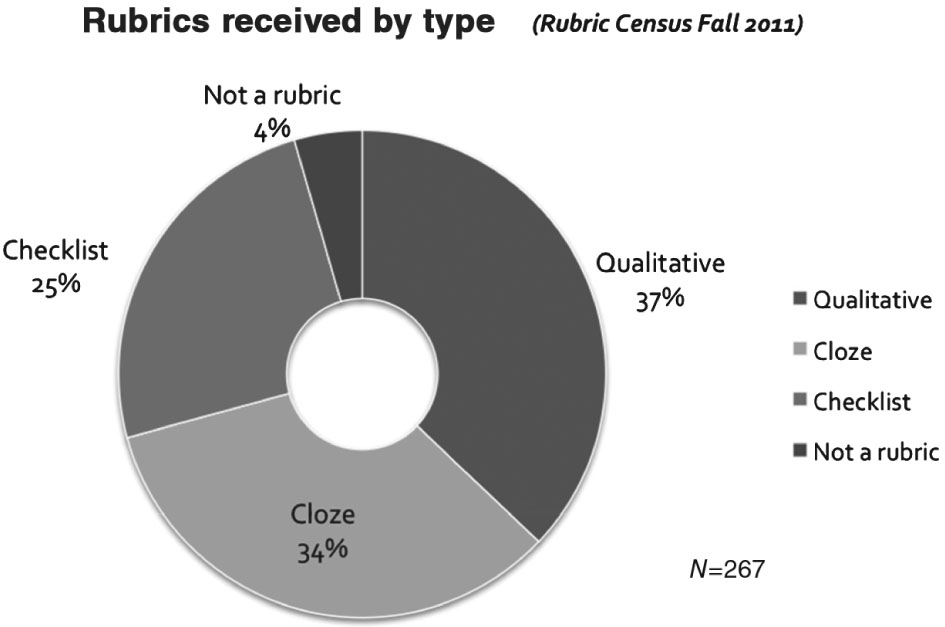

To answer this question, we conducted a campus wide “rubric census” in 2011 to examine the range of artifacts that traveled under the moniker “rubric.” In response to our simple appeal (“ Send us your rubrics !”), we received 267 submissions from approximately 190 of the 1,000 faculty at that time. We then analyzed the rubrics for their features, including language, length, inclusion of points and/or visual exemplars, and number of levels and criteria. Our analysis yielded four main categories: qualitative, cloze, checklist, and “not a rubric” (Figure 1).

Approximately 20 rubrics were accompanied by visual samples of student work.

Rubrics had an average length of 333 words and five criteria.

The “not a rubric” category included assignment sheets, scoring records, or other tools that helped organize a class but did not articulate expectations at more than one level. Checklists generally had two levels (often yes/no) but failed to differentiate between “passing” and “exceptional” work. Educational consultant Borgioli (2011) notes that checklists can be useful for assessing qualities that are important but essentially binary, for example, in our context, whether technical specs were followed or if the work was labeled, saved, or mounted correctly. However, we suspected that checklists alone might not capture the scope of skills assessed in iterative, high stakes projects requiring skills integration or creative thinking. [1]

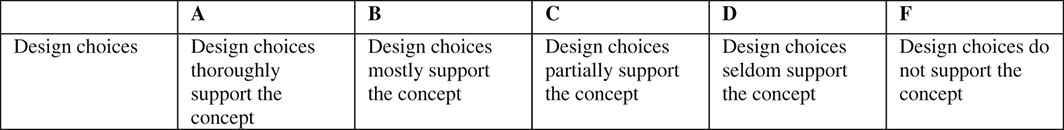

What we came to call “cloze” rubrics (after the language exercises that require students to fill in a blank to complete a sentence) were perhaps most troubling. Cloze rubrics often reused similar language across the board and resulted in very long rubrics with five or more levels of achievement. Even shorter cloze rubrics came across as very wordy due to repeated blocks of language in each column (e.g., Figure 2). Descriptors relied on subjective words (such as excellent and thoroughly at the A level or adequate and acceptable at the C level) for differentiation. This subjective language echoed but did not explain the reasoning behind the letter grade at the column heading. Descriptions of how students fell short, or where they needed to improve, remained locked behind subjective wording. We wondered how helpful cloze rubrics might be to students’ internalizing the key concepts of a course.

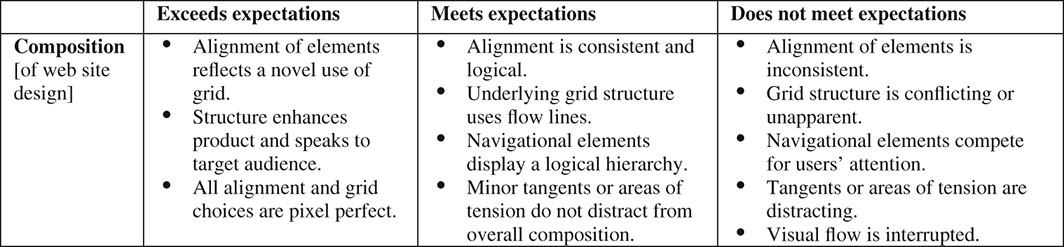

In contrast, qualitative rubrics were characterized by carefully worded, more objective explanations of how criteria manifest themselves at various levels. These explanations “unpacked” opaque concepts (e.g., balance in typography, anticipation in animation, or usability in web design) into concrete descriptions, and they usually described only three levels of achievement. The three column rubric appeared to steer the instructor’s attention to the qualities of the work, more like a critique does. By comparison, rubrics with five columns seemed to offer instructors phrases to justify predetermined grades, or they communicated an implicit expectation that selecting descriptors under a given level automatically “calculated” the grade in the column header. Qualitative three column rubrics stood out in our analysis as teaching tools that had possibilities for many applications (including self and peer assessment) in the art and design classroom (Figure 3).

In light of these categories and the questions they engendered, we made plans to investigate the effectiveness of the various types of rubrics in particular contexts. However, our efforts to systematically determine the most effective characteristics of rubrics were curtailed when, in 2012, a major turning point occurred that dramatically altered our role in rubric development. Our office was summoned to support the development of a rubric tool and an accompanying rubric building process in our institution’s online education department. We had to trade our researcher lens for our pragmatic educational developer lens, responding to campus initiatives.

Formal, Shared Rubrics: 2012

The online education department had decided to develop a “rubric tool” for our institution’s proprietary learning management system (LMS) in response to instructors’ increasing demands for rubrics in online courses. The initial prototype for the rubric tool (developed prior to our involvement) exemplified the over generalized use of the term “rubric” that had prompted our rubric census research: It consisted of samples of visual student work with accompanying uniquely written critiques and grades. The tool was visually appealing and organized in its presentation, but consistent criteria and descriptors—the actual rubrics—were missing.

We proposed including a qualitative rubric grid in the rubric tool, and we also voiced concern about instructors’ willingness to use rubrics that they themselves had not developed (core online course content is consistent across sections at our institution, not specific to individual instructors). Rubrics, if they were to be integrated at the course level, could not be extensions of instructors’ individual teaching methods and standards. They would need to be transparent to anyone teaching the course. It became clear that incorporating rubrics into online courses would entail more than a publication tool; it needed accompanying processes to ensure quality rubrics and instructor investment.

A vibrant discussion with a variety of stakeholders ensued. Faculty developers wanted meaningful rubric formats and processes that encouraged faculty buy in. Administrators, who witnessed a decrease in grade disputes after shared rubrics were implemented in the Foundations department, called for more consistent standards across sections. We concluded that visual displays of student work and consistent, transparently communicated standards could benefit multiple audiences: online and onsite students at all levels, faculty teaching multiple sections of a course, and even accreditation teams. However, if rubrics were going to fulfill their potential, they needed to be good. The plan we drafted to usher the university into consistent transparent classroom assessment included a revised format for the online rubrics tool, a campus wide rubric initiative, rubric development process, and rubric quality standards.

The rubrics tool

The online tool that was ultimately born of these discussions took the form of two “tabs” behind the assignment in the LMS. The first tab is the rubric, a three column grid with levels of exceeds , meets , and does not meet expectations and bulleted phrases for the descriptors. Our experience in looking at sample rubrics in the 2011 rubric census told us that limiting the levels to three helped the levels stay distinct and be less prone to cloze like phrasings. Due to instructors’ varying comfort levels with assigning numbers to aspects of student work, we left points off the templates. The second tab is titled “sample critiques.” It includes visual samples of student work at the same three levels as the rubric, with an accompanying “critique” for each sample. The critique is composed only of applicable verbiage taken verbatim from the rubric. Samples had to be three semesters old to protect current and recent students’ identities.

The rubrics initiative

The accompanying rubrics initiative called for creating and publishing formal shared rubrics—with sample critiques whenever possible for work that exceeded, met, or did not meet the standards— into all first year core courses for all major assignments, in both online and onsite sections. The university president announced the initiative and placed someone in charge of tracking the process to ensure participation and accountability.

The rubric development process and rubric quality guidelines

The development process and publishing standards became the purview of the CTL. Faculty developers were charged with shepherding each rubric through the creation and norming process, and for the first time, they became gatekeepers for rubric quality. Rubrics that had not been vetted by a faculty developer (in addition to the appropriate academic director) were not publishable in the LMS.

A faculty developer works with a designated, contracted instructor to build a three column rubric for one major assignment according to the set of standards below.

The faculty developer facilitates a norming session with core instructors and the department director (or representative). The rubric is normed against samples of authentic student work at three levels, and edits to the wording of the rubric are negotiated.

The designated instructor completes the sample critiques for publication, using the normed rubric, and submits the entire packet to the director for approval.

The approved, normed rubrics (including sample critiques when possible) are published in the LMS in all sections of a course, where both instructors and students can refer to them.

More often than not, the process above proceeds in a predictable manner, especially now that the rubric initiative has been in place for two years. However, engaging a department in the rubric development process sometimes unearths curricular or teaching issues that need to be remedied, for example, vast differences in long term faculty members’ approaches to the same course or differing high stakes projects in sections of the same course.

The formal rubric standards (see Figure 5) we developed emerged from our previous work on rubrics. Guidelines to limit length and the number of columns came directly out of our rubrics census. We had always encouraged clear language that described observable qualities of work, but this clarity became even more important with the shared nature of the formal rubrics. The norming meeting that is part of the formal rubric development process also builds in natural accountability for clarity. The negotiation that results from several instructors assessing a specific piece of student work and comparing the phrases that they highlighted often leads to a revised rubric that is more meaningful and in which instructors are invested.

We insist that the “meets expectations” statements describe how the work does meet expectations, not how it falls short. This requirement flows from our institution’s guideline that work that meets all minimum expectations receives a “C” grade. [2] Descriptions of how a piece falls short of expectations are included in the “does not meet” column. Having instructors articulate the “meets expectations” column in a positive way seems to help them distinguish between work that meets minimum expectations and work that truly goes beyond the basic expectations.

We examine the language in the “does not meet” column, in particular, for objectivity. We frame this column as a place to note “common pitfalls” in students’ work and encourage rubric writers to word the descriptors assuming that the student has made a sincere effort and will improve after receiving the feedback. This frame keeps the feedback focused on the work, not on a student’s personal, creative, or procedural shortcomings in approaching the task.

Increasingly, rubric writers want to include a criterion for “creative process” or “revisions” in a rubric. While descriptors of the finished work help guide students’ creative process by describing its end point, descriptions of how students are expected to engage in the process are also helpful. In these cases, we continue to ask rubric writers to focus on the evidence of process—what student work looks like when a student is engaging the way they should. These process descriptors often refer to process work, such as thumbnails and evidence of research, but they also refer to the student’s responses to critique or how they incorporate feedback into project iterations.

SPORE 2 and IPORE Research

With the new formal rubric process and standards, we strove to stay true to the principles that had guided our work since our center’s inception. However, in our new gatekeeping role, we faced many questions (often from one another) about formalizing rubrics: How detailed should they be? How much agreement among instructors is necessary for a rubric to be “normed?” Will faculty resist using rubrics that they are not allowed to write and edit themselves? Faculty regularly raised concerns about the wisdom of including exemplars of student work with the rubrics, reasoning that “Students will simply copy what we show!” Amidst the questions and discussions, we forged ahead and ushered 47 rubrics (covering approximately 50% of all first year core courses) through development and publication within the program’s first year.

After the Fall 2013 semester, we again applied our researcher lenses to this changing rubric environment, readministering the SPORE survey (known as SPORE 2) to students, and we created an instructor version of the survey as well (IPORE). While the new official, formal rubrics comprised a minority of existing rubrics at our institution, we anticipated that if we were clearly on the wrong path, the survey data would show that effect. The quantitative report of that body of research follows.

Research Methodology

In collaboration with our institutional researchers, we examined faculty and student perceptions of rubrics. The Instructor Perceptions of Rubric Effectiveness (IPORE) questionnaire was emailed to all faculty in December 2013. From the list of sections taught by instructors who self reported using rubrics in the Fall 2013 term, we pulled student ID numbers to build the recipient list for the SPORE 2 survey (see Table 1). The SPORE 2 survey was completed in January 2014 before the spring semester started so as to not have experiences of the new semester color the old.

With the help of our institutional researchers, we developed two overall “rubric usefulness variables” (with 1 = Not Useful and 5 = Useful) based on faculty and student responses to separate 9 item sets of questions. These 5 point Likert scale response options ranged from 1 “Strongly Disagree” to 5 “Strongly Agree” (see Appendices for survey instruments). Both perceptions of rubric usefulness scales showed strong internal consistency (α = .88), demonstrating reliability of the instruments. In other words, the items used in the survey accurately assessed the usefulness of rubrics.

The favorability of the rubrics scale was further analyzed in terms of the nine individual level items by year. There was an insignificant difference [ t (542) = .150, p > .05, d = .01, less than small effect] between 2008 ( x̄ = 3.74, SD = .73) and 2014 ( x̄ = 3.75, SD = .68) student responses on the favorability of rubrics scale.

While each SPORE survey yielded its own interesting results, the comparison of the two student surveys—especially with the instructor voice added in the second round—yielded clearer trends and findings. We highlight the most potentially relevant ones below.

1. A strong majority of students and instructors perceived rubrics to have a positive effect on student learning

We posed the question about usefulness of rubrics in multiple ways to both students and instructors, trying for both a general impression (Table 2) and specific impacts (Tables 3 and 4). Favorable attitudes toward rubrics emerged for both students and instructors.

In the question exploring the specifics of a rubric’s impact on students’ perceptions of rubric usefulness, there was a slight but statistically insignificant rise in most categories between 2008 and 2014. The most common answer, I do a more complete job on my assignments , remained constant for 2008 and 2014. I am more organized also remained in the top three answers in both surveys. Two of these top three answers for both surveys address students’ work habits, while second place I am less surprised by my grade and its replacement in 2014 I have fewer questions about the assignment reflected students’ reactions to the assignment and assessment process.

It is important to note that the item I feel confused was a negatively worded item, and student disagreement with this item actually reflected higher favorability toward rubrics (this inversion of the scale for this item is accounted for in the “rubric usefulness variable” described earlier in this section).

Unlike in the student survey, there was no single “rubric usefulness” question posed to instructors. However, the responses from Item 19 How useful in general are rubrics ? Rate the usefulness of rubrics for each statement . (Table 4) led to an overall “instructor usefulness variable” (see Methodology) of 3.84 of 5. Instructors’ most common positive uses of rubrics were that they (a) clarified the assignments for students, (b) saved the instructor time while grading, and (c) focused teaching.

2. Faculty and students both rated “assignment clarification” most frequently as a useful aspect of rubrics

Eighty five percent of instructors who used rubrics said that the rubrics clarified the assignments for students (see Table 4) Similarly, over 70% of students responded that with rubrics, they did a more complete job and had fewer questions about assignments (see Table 3) The role of rubrics in clarifying assignments was further supported by students’ responses to the question, When and why do you refer to rubrics ? In 2008, and even more so in 2014, students’ most common answer was Before starting an assignment to clarify the assignment and / or plan out my work (Table 5).

3. Most instructors and students perceive rubrics to have a neutral or positive effect on student creativity

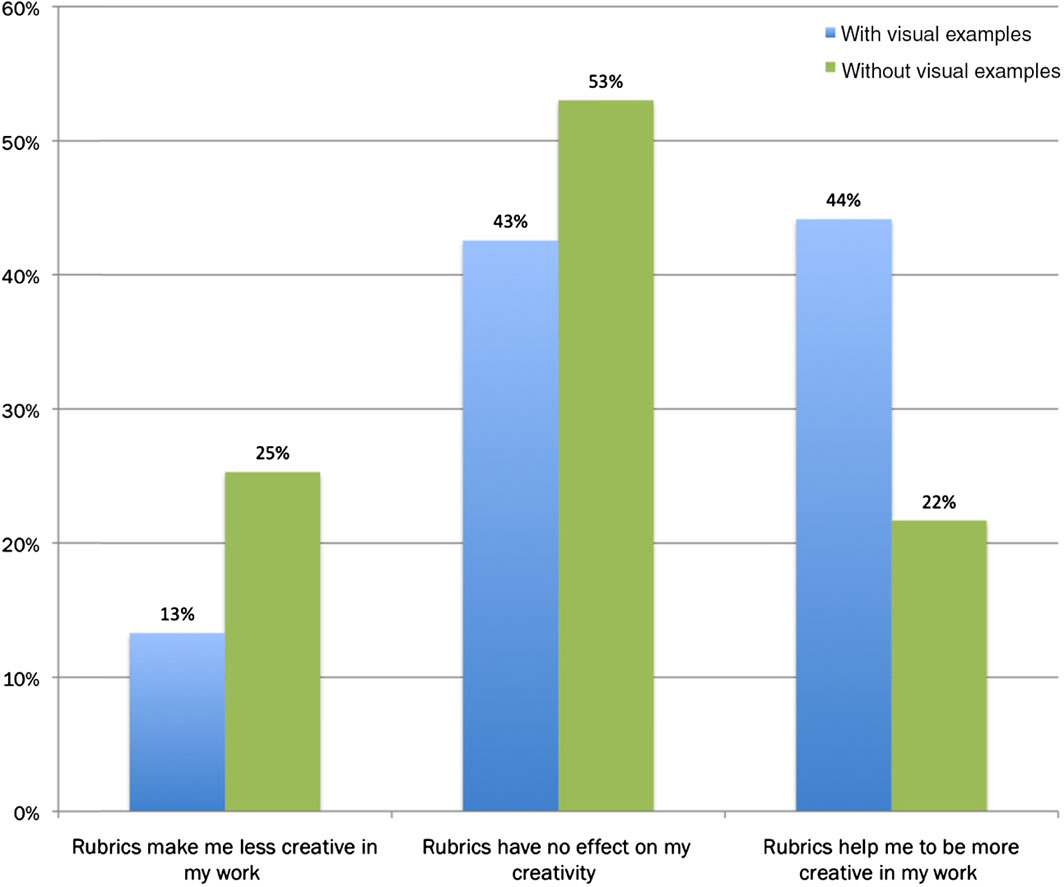

A minority of students and instructors reported that rubrics interfere with creativity. The most common perception of rubrics’ impact on creativity was one of neutrality or no effect. The 2014 results actually showed a marked increase in the number of students reporting that rubrics enhance their creativity (Table 6).

It gives you some parameters to work within which, to me, encourages me to think of ways to push the limits of those parameters and think more creatively.

I think I am still learning skills not so much creativity.

I think my original creativity is not being affected by using them. But in terms of academic success, the use of rubrics is essential for me.

4. Students who received rubrics accompanied by exemplars or “sample critiques” perceived rubrics to enhance their creativity at a significantly higher rate (44%) than students who received only written rubrics (22%)

This finding directly contradicted many of our instructors’ fear that students would simply copy what had already been done if sample critiques were included with written rubrics (Figure 6).

Seeing what others have done loosens restrictions. It is nice seeing that there is so many options for development of the project and content becomes less focused on what I cannot do.

I see what great work others have turned out and it inspires a sense of competition in me. Then I work harder to keep up. It’s also comforting to see where I stand at the moment.

5. No significant difference emerged in instructors’ usefulness ratings of formal and informal rubrics

faculty who chose to use rubrics ( n = 78). Rubric usefulness score: 3.87, SD = .65

faculty strongly encouraged to use rubrics but were not required to do so ( n = 68). Rubric usefulness score: 3.85, SD = .54

faculty who were required to use rubrics ( n = 63). Rubric usefulness score: 3.76, SD = .81.

Results showed that there were no significant differences between these three faculty groups: F (2, 206) = .574, p > .05, η 2 = .005 (less than small effect).

We also asked the faculty about the kinds of courses and assignments where they deemed the use of formal (called “standardized” in the survey) rubrics (i.e., shared in all sections of a course) to be effective (Table 7):

While faculty developers find themselves questioning the larger implications of formalizing rubrics, the majority of participating instructors find formal, or required, rubrics to be as useful as the ones they write themselves.

Rubrics provide students with clarity regarding the learning outcomes that they must demonstrate, and how to do so. Properly written, they help the student focus without stifling creativity.

I feel each class can accomplish the same course learning outcomes, but the way in which to get there should be flexible. It depends on the teacher’s strengths, and their view of what is the most important takeaways from the material. This also involves the student’s own particular strengths. Standardizing rubrics can defeat the purpose of individualizing the education to best help any particular student.

6. Personalized comments are in decline, yet their presence influences students’ views of rubrics

In both SPORE 1 and 2, we asked students whether they received additional comments written by their instructor. In 2014, we witnessed a significant (15%) drop in the percentage of students reporting that they received comments from the 2008 level (from 36% to 21%). Students who received personalized comments on their rubrics indicated, on average, significantly higher rubric favorability (4.02 of 5) than students who reported sometimes (3.70) or never (3.51) receiving extra personalized comments (significant differences at the p < .05 level).

When we embarked on the SPORE and IPORE research, we anticipated favorable responses to rubrics, but we had no idea how positive the responses would be. The results encouraged us as both on the ground educational developers, striving to improve teaching and learning processes at our own institution, and as researchers, wanting to contribute to a larger scholarly dialogue about teaching and assessment in art and design.

In our exuberance over the widespread appeal of rubrics, however, we should bear in mind the limitations to our data so as not to over generalize the findings. First of all, the data is self reported on perceptions of rubric effectiveness; measuring the true impact of rubrics would entail analyzing actual student work on a large scale. Second, some respondents may still be confused about what a rubric actually is in spite of the CTL’s efforts to define quality formal rubrics since the Rubric Census of 2011. The survey did not ask respondents for any particular confirmation of their understanding of “rubric.” A third limitation to our data is that we were not able to specifically compare student perceptions of formal rubrics (developed in close partnership with a faculty developer and carefully vetted) with instructor created rubrics (which may or may not have been developed with a faculty developer). Although we asked students to name the courses in which they had received rubrics the previous semester, many students named several courses, and their responses addressed rubric use in general. Our data on student perceptions, therefore, measure the whole complex mosaic of attitudes around a broad variety of rubrics at a given point in time.

Despite these limitations, the research has given us and our fellow faculty developers at AAU confidence in our overall approach to rubric development with artists and designers. Objective numbers help us keep the attitudes of individual AAU faculty about the unpredictable, fragile nature of creativity and art in perspective. The tremendous amount of research that has been done on creativity, especially in the past 15 years, shows that creative thinking actually consists of fairly well defined stages, habits of mind, and a lot of hard work (Sawyer 2012). Over time, most of our teaching artists’ and designers’ attitudes, while emerging more from practical than scientific exploration, have come to reflect a similar understanding. How and why did instructors evolve from “you can’t grade art” to their present attitudes? We think that they changed as they interacted with rubrics and engaged in discussion with us. However, we have to also acknowledge that we likely changed as well. Perhaps we came to listen more carefully as we worked to make rubrics reflective of their classroom practices. Many instructors welcome the clarity and structure of rubrics to strengthen and focus their teaching, and they no longer fear that assessment efforts or grids of language will damage the fragile muse of creativity. Training new instructors on implementing the rubric tools and constructively introducing them to their students will remain a perennial task for our CTL to maintain instructors’ awareness of rubrics’ potential and applications.

Rubrics’ usefulness appears to stem largely from their role in “assignment clarification,” and an examination of why this is so reveals an unsurprising connection: Understanding the assessment is key to students’ identifying the most important aspects of a course. Gibbs and Simpson (2004–5) summarize a body of research that shows students’ study habits—what course content they attend to and the importance they attach to it—is determined more by the assessment system than by any other facet of a course. Almost 80% of our students reported using rubrics to help them plan their work, so it seems that rubrics, when present, are indeed a—if not the —dominant factor guiding students’ attention and work habits.

The finding that the vast majority of instructors and students do not perceive rubrics as impairing creativity leads us to believe that we can continue our current approach—encouraging instructors to use the “right criteria and multiple and varied exemplars” (Wiggins 2012)—without fear of destroying students’ creativity. However, this finding, along with the accompanying student comments that frame creativity as something separate from what the rubric addresses, raises the question of how students are defining creativity. Creativity is often equated with divergent thinking—generating lots of ideas. As Sir Ken Robinson (2010) notes, while divergent thinking is a critical and often overlooked piece of creativity, “[i]t’s not the same thing as creativity.” Sawyer (2012) defines Eight Stages of the Creative Process, only one of which is generating ideas. A second question that this finding raises is whether instructors are assessing creativity at all. Anecdotally, we are seeing more instructors who are defining and assessing creative skills and process work. However, other instructors find it difficult to separate creativity from the raw work of creating art and design—the problem finding, research, prototyping, skill building, brainstorming, critiquing, and refining that goes into producing a creative work. So while our research to date assures us that rubrics do no harm to creativity, the question of how to assess creativity directly, or whether indeed it is prudent to do so, bears further exploration.

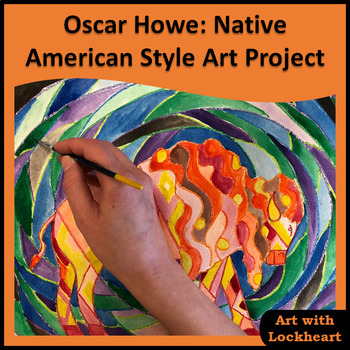

The role of exemplars in enhancing students’ perceived creativity is a provocative one. Student comments imply that being able to view previous student work helps them understand assignment parameters better and encourages them to go further. This finding echoes McCollister’s (2002) observations about the importance of visual exemplars, “not to imply copying, but rather the insight and leaps of faith that bolster confidence” (p. 48). However, it is also possible that the assignments with exemplars were preselected to invite more creative thinking. Closed ended or “auditive” assignments (e.g., Compare and contrast DaVinci ’ s Mona Lisa and Michelangelo ’ s Pieta in a short essay ) do not include exemplars as posting previous student work would reveal the answers.

One caveat that the data bring to light is that with more formal rubrics in the institution, instructors are now less likely to write personalized feedback on rubrics than they were before. This lack of personalized feedback may indicate that instructors perceive formal rubrics as a replacement for individual comments. We need to continue to remind instructors that, as Connelly and Wolf (2007) found upon introducing rubrics into an advanced painting course, “a rubric cannot replace the personal touch of a hand written comment” (p. 286). Our own data also revealed that students who get personalized feedback tend to view rubrics as significantly more useful all around (see point 6 under Results). An alternate reason for the decrease in personal feedback on rubrics may be the limitations of our particular institution’s electronic delivery method. In 2008, rubrics were largely printed on paper and used as feedback sheets. Today, they are increasingly becoming static reference objects in the LMS. To actually fill one out as a grade sheet in an online course is laborious, and not all instructors take this added step. Proposed electronic rubric tools that streamline the highlighting and commenting process may mitigate this effect. Whatever the delivery tool, rubrics should decrease and streamline, but not altogether replace, instructor comments on student work.

Student perceptions of rubrics became more positive across almost all categories between 2008 and 2014. Students also refer to rubrics more now in all aspects of their work than they did in 2008. While the limitations to our data (explained earlier in this section) prevent us from attributing this trend to the introduction of formal rubrics, we can at least conclude that formal rubrics are doing no widespread harm to student perceptions of their effectiveness.

We plan to readminister these surveys again in 2018. If current trends continue, we will be able to draw a more conclusive picture of the effect of introducing formal rubrics at an art and design university.

Perceptions of rubric effectiveness research conducted at AAU reveals that the majority of both instructors and students deem rubrics to be supportive of learning in a dedicated art and design setting, where rubrics are treated as not just grading tools but extensions of the critique. Keeping the rubric development process firmly rooted in the critique, as faculty developers’ roles expanded from coach into gatekeeper, seems to have helped faculty and students maintain a positive disposition toward rubrics. Even the introduction of institutionally required formal rubrics in 2012 has not dampened students’ enthusiasm for rubrics.

Most art and design faculty welcome formalized, normed, shared rubrics for major projects in first year courses. The heavy involvement of faculty developers in the rubric creation process ensures their usability by multiple instructors. The norming process then includes multiple instructors who become invested in the tool and trained in its use so that they see the rubrics as extensions of their own teaching. However, even high quality rubrics do not replace personal comments, which are crucial to forging the relationship between students and faculty. Moving forward, the trick will be to retain the sense of faculty ownership and engagement with the existing rubrics. Once a rubric is embedded into a course’s online assets, it risks becoming part of the infrastructure. As more formal rubrics are developed, both faculty developers and department chairs will need to find outlets for revisiting, refreshing, and reviving the important conversations about performance and standards that these tools spark.

The encouragement we offer for faculty and their CTLs considering rubrics in creative disciplines: Go for it! Your rubrics, if offered in a spirit of communication, access, and transparency, will not destroy students’ creativity. Done right, they may even enhance it.

Just as strong rubrics grow out of conversations about actual student work, not out of abstract thinking about “good art and design,” we believe that strong educational development practices grow out of conversations with instructors about actual teaching and less out of abstract thinking about rubrics and assessment. While we hope that other institutions are able to find inspiration in our story and data, we also encourage educational developers who are working with artists and designers to engage in meaningful conversations about assessment and create their own rubric story to advance research and practice on their own campuses.

Acknowledgments

Our fellow faculty developers, other teaching colleagues, and online education team have been as much a part of the AAU approach to rubrics as the authors have been. Similarly, AAU’s institutional researchers provided invaluable help in understanding the data that our surveys generated.

Appendix A: SPORE Survey Questions (Student Perceptions of Rubric Effectiveness)

Grad student

3. What is your major?

[Students selected from a drop down list].

NOTE: [In 2014, we added two questions that pushed all subsequent items down two slots. Those were:

4. In which classes did you have rubric last semester? and

5. Did any of the rubrics include visual examples of (past) student work?

So as to prevent redundancy, the rest of the questions herein will keep the 2008 numbering, but in examining results, please note that item numbers for 6 and up correlate to the same items two numbers lower on the 2008 survey (e.g., Item 12 in 2014 matches Item 10 in 2008).

About rubrics:

Before starting an assignment to clarify the assignment and/or plan out my work

While working on an assignment to make sure I am on track

During critiques or peer reviews to focus my comments

Before turning in a final draft of an assignment to assess my own work.

After I have received a grade—to help me understand why I got the grade I did.

When giving the assignment, or before

While I am working on the assignment

When returning the assignment to me along with the grade and/or feedback.

During the critique

I’m not sure

I read only the descriptions of the grade(s) I’m hoping for

I never look at the rubric at all before turning work in

I usually read only the parts that my teacher has circled for me

I never look at the rubric at all after I’ve gotten my grade

My individual teacher

My department at XXX

My chosen professional field

I learn much more if I have rubrics in a class.

I learn a little more if I have rubrics in a class

Rubrics don’t make a difference.

I learn a little more without rubrics

Rubrics get in the way of my learning

12. In which classes and/or departments would you like to see more rubrics?

More creative

Less creative

14. Please comment about how rubrics affect your creativity:

15. What can teachers do differently to make rubrics more useful to your learning?

16. Please share any other comments you have about rubrics in the space below:

Appendix B: IPORE Questions

1. Do you use a rubric in any of your courses this semester?

I don’t know what they are

They take too much time to develop

They will interfere with my teaching style

They will impair student learning

They will impair student creativity

3. Comments:

4. If you would you like a Faculty Developer to contact you about creating rubrics, please enter your contact information and name below:

2. Please list the course name, department, course number and section in which you use rubrics.

Rubrics are serious business in the high-accountability culture of education. However, they often come across as dry and uninteresting, and language used in them can be vague and unclear. The goal of a rubric should be to provide a student with support and feedback about their work. But how many rubrics are actually student-friendly? Not enough!

Here are 4 tips to create crystal-clear rubrics that are easy for your students to understand and enjoyable for them to fill out.

1. Be clear when it comes to your learning objectives!

Understanding by Design , also known as backward design, is an extremely useful approach to developing rubrics and curriculum. Developed by Grant Wiggins and Jay McTighe, the framework focuses on designing curriculum “backward” by starting with the ends or outcomes you hope to achieve.

Here’s how it works with rubric development.

- Start by identifying what you want students to know, understand, and do before developing the activities. Are you trying to build an understanding of value scales with your students? Working on technical drawing skills? Clarity of objectives is key!

- Decide what kind of performance spread you are assessing. Predicting the range of student outcomes can help determine if the objectives are too broad or too narrow. For example, trying to assess the “quality” of photographs taken by a student might encompass too many factors as a single objective. However, breaking it up into 1) Clarity of subject, 2) Ability to properly focus, and 3) Composition of images is much easier to identify and assess.

- List your specific objectives before coming up with the activities. Often, teachers will come up with the idea for a project and then figure out how to assess it afterward. This can lead to a disconnect between the work and assessment. Working backward provides a clearer connection between the two.

Looking for even more information about assessment in the art room? Don’t miss the AOE Course Assessment in Art Education ! You’ll leave the course with a comprehensive toolkit that has many different types of authentic assessments ready for direct application in your classroom!

2. Choose the appropriate assessment tool.

What exactly are you trying to measure? Knowing and understanding what and how you’d like to assess things is really important. This article by Karen Erickson, a theatre artist and educator, is a great primer on whether a rubric is even necessary for the task you’re assessing. According to Erickson:

A rubric is a tool that has a list of criteria, similar to a checklist, but also contains descriptors in a performance scale which inform the student what different levels of accomplishment look like.

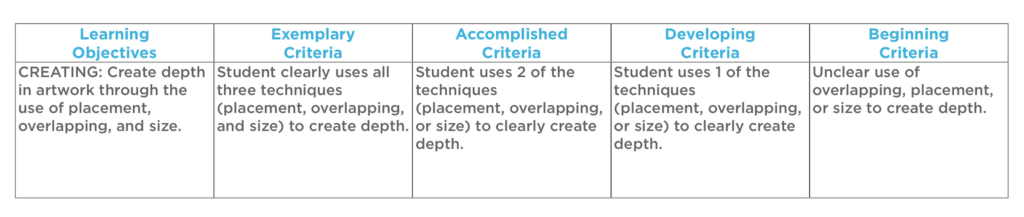

So, if you’re just trying to check off lists of actions, maybe you don’t need to create an entire rubric. Additionally, creating descriptors that only measure the frequency of accomplishment of a task can overly simplify things. If a student needs to achieve five points in a descriptor, does it matter which points are mastered? The example below shows how specific descriptors can differentiate a hierarchy of skills while also being checked off as a number of outcomes are being measured.

3. Be mindful of the language you use.

When creating rubrics, avoid subjective language. “Mostly,” ‘Excellent,” and “Somewhat” are all examples of terms that could be interpreted differently depending on the educator. In addition, make sure the descriptors make sense to students. A student should be able to use a rubric to figure out how they could improve next time.

Keeping these things in mind, I believe it’s ok to be a bit wordy in the rubric description. Using a descriptor like “ Quality of line is rough and sketchy. Cleaner lines and attention to detail would improve the overall appearance of work” is much more helpful than “ Line quality was poor.”

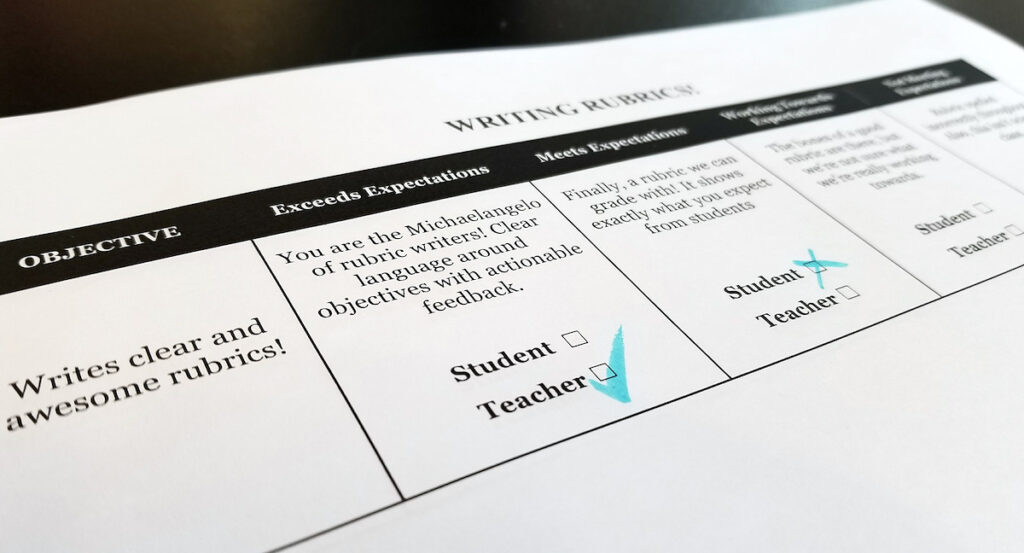

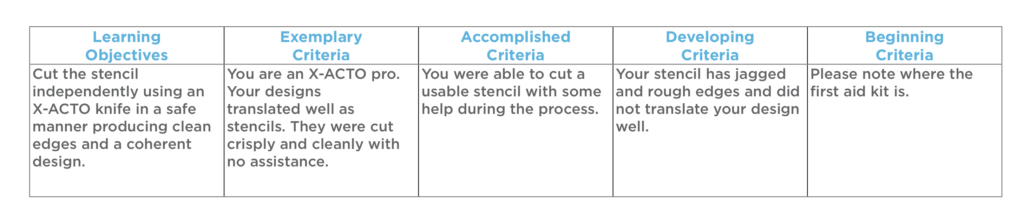

4. Now, find some space for humor!

I have yet to come across a student who expresses enthusiasm in reading through most rubrics and expectations. But I know I want them to give it their attention and understand what we’re trying to accomplish with the project. So, I try to give the descriptors a bit of personality. I’m not advocating you crack a joke in every box, but picking your spots while still giving some feedback makes a difference.

Choosing either the upper or lower extremes of descriptors will often be the most appropriate moments for levity. The ends of the scale lend themselves to hyperbole, and some humor brings the feedback into focus. In the example below, I am looking for technical proficiency with X-ACTO knives. Yes, students know to be careful with a sharp tool, but most of them don’t pay attention to appropriate cutting techniques. Cracking a joke here reminds them to take care, that there is, in fact, a first aid kit in the room, and that we don’t really want things to get gory in art class.

You need to do what works for you, but trying to keep things light in the descriptors helps to get students to read them. It might be that you bring some humor in when talking through the descriptors with your students. How you approach it matters, and it should always feel authentic. Don’t force the jokes.

Clear and engaging rubrics provide an important reflection tool for students. When we complete a project, the assessment provides information not just for teachers, but for students as well. It’s an important opportunity you don’t want to miss.

How do you review rubrics with your students?

Are there other creative and fun ways you engage students in assessment?

Magazine articles and podcasts are opinions of professional education contributors and do not necessarily represent the position of the Art of Education University (AOEU) or its academic offerings. Contributors use terms in the way they are most often talked about in the scope of their educational experiences.

Raymond Yang

Ray Yang is the Director of Equity, Diversity and Inclusion of NAEA and a former AOEU Writer. They believe the arts can change the world.

How to Teach Self-Reflection, Critiques, Artist Statements, and Curatorial Rationales Like a Pro

5 Points of Discovery to Unpack When You Teach IB Visual Arts

9 Ways to Plan for and Support Students Through the AP Art and Design Portfolio

How to Easily Break Down AP Art and Design Portfolios

- Survey 1: Prehistory to Gothic

- Survey 2: Renaissance to Modern & Contemporary

- Thematic Lesson Plans

- AP Art History

- Books We Love

- CAA Conversations Podcasts

- SoTL Resources

- Teaching Writing About Art

- VISITING THE MUSEUM Learning Resource

- AHTR Weekly

- Digital Art History/Humanities

- Open Educational Resources (OERs)

Survey 1 See all→

- Prehistory and Prehistoric Art in Europe

- Art of the Ancient Near East

- Art of Ancient Egypt

- Jewish and Early Christian Art

- Byzantine Art and Architecture

- Islamic Art

- Buddhist Art and Architecture Before 1200

- Hindu Art and Architecture Before 1300

- Chinese Art Before 1300

- Japanese Art Before 1392

- Art of the Americas Before 1300

- Early Medieval Art

Survey 2 See all→

- Rapa Nui: Thematic and Narrative Shifts in Curriculum

- Proto-Renaissance in Italy (1200–1400)

- Northern Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Sixteenth-Century Northern Europe and Iberia

- Italian Renaissance Art (1400–1600)

- Southern Baroque: Italy and Spain

- Buddhist Art and Architecture in Southeast Asia After 1200

- Chinese Art After 1279

- Japanese Art After 1392

- Art of the Americas After 1300

- Art of the South Pacific: Polynesia

- African Art

- West African Art: Liberia and Sierra Leone

- European and American Architecture (1750–1900)

- Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth-Century Art in Europe and North America

- Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Sculpture

- Realism to Post-Impressionism

- Nineteenth-Century Photography

- Architecture Since 1900

- Twentieth-Century Photography

- Modern Art (1900–50)

- Mexican Muralism

- Art Since 1950 (Part I)

- Art Since 1950 (Part II)

Thematic Lesson Plans See all→

- Art and Cultural Heritage Looting and Destruction

- Art and Labor in the Nineteenth Century

- Art and Political Commitment

- Art History as Civic Engagement

- Comics: Newspaper Comics in the United States

- Comics: Underground and Alternative Comics in the United States

- Disability in Art History

- Educating Artists

- Feminism & Art

- Gender in Nineteenth-Century Art

- Globalism and Transnationalism

- Playing “Indian”: Manifest Destiny, Whiteness, and the Depiction of Native Americans

- Queer Art: 1960s to the Present

- Race and Identity

- Race-ing Art History: Contemporary Reflections on the Art Historical Canon

- Sacred Spaces

- Sexuality in Art

Assignments & Rubrics

Written Assignments

The Museum Response Paper template can be used as an assignment once or twice during the semester as a way to a) have your students undertake a concise written exercise that b) asks them to look closely at one object (or two if you’d like them to compare and contrast) and c) also asks them to engage with the museum or gallery space to make them aware of the cultural context in which they encounter objects in institutions. This template can be “set up” in class using the museum visit videos and Museum Observation Prompts handout.

This Formal Analysis Assignment provides some great ideas on how to guide students through formal analysis reminding them that the exercise is about looking and analysis and not research and analysis. Students are reluctant to trust their own eyes and their own opinions. For formal analysis papers they often automatically go to an outside source in order to further bolster the assertions they make in their papers. Kimberly Overdevest at the Grand Rapids Community College in Grand Rapids, Michigan has had great success with these prompts.

To research or not to research? Asking your students to undertake a research paper as part of the art history survey can be a tricky beast as the range of student experience with elements such as library research and bibliographic citations can be large and crippling. For most mixed-ability or required-credit survey classes, focusing on short papers with limited research allows you and the students to focus on finessing writing skills first. Always consider reaching out to the Writing Center on your campus – a staff member can usually make an in-class visit to tell your students about the range of services on offer which should include workshops and one-to-one appointments.

Presentations – either singly or in groups – can be a good way to have your students think about a class theme from a new angle. See the handout “ How to give a great oral presentation ,” which also contains a sample grading rubric so students understand instructor expectations as they prepare.

Writing Guides and Exercises

The “ How To Write A Thesis ” template is a useful handout for a class exercise post-museum visit , once students have picked their object and can think about what a thesis is and how to construct their own. As part of this in-class exercise, it might be useful to look at examples of previous students’ thesis statements on the Writing Examples PPT which includes anonymous examples of past museum response paper excerpts so students understand what a thesis statement, formal analysis paragraph, museum environment analysis, and concluding paragraph might look like (you can, of course, point out the merits and/or pitfalls of each example per your own teaching preferences).

Paper Style Guide handouts

Grading Rubrics

The Grading Rubric handouts can be given out in class and/or uploaded to your Bboard, and retooled to fit your objectives for the written assignment.

Grading student papers can be done the old fashioned way (your students hand you a paper copy) or through anti-plagiarism software such as SafeAssign (part of the Blackboard suite) or Turnitin.com (your school may have a license – find out who the Turnitin campus coordinator is for more details). There are ethical considerations to using anti-plagiarism software.

Formal Analysis Rubric Grid

Research Rubric Grid

Comments are closed.

- Free Resources

- Register for Free

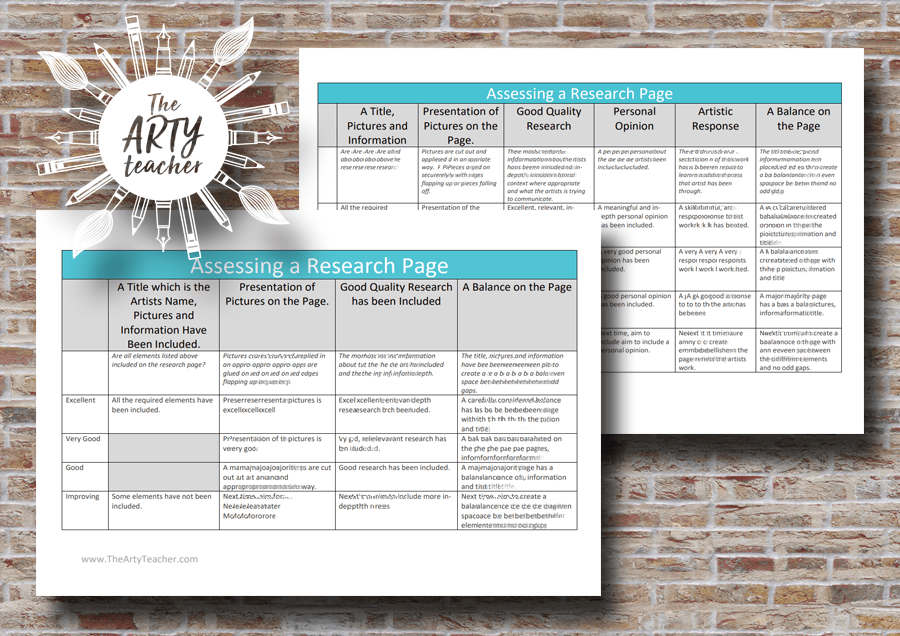

Assessing An Art Research Page

I want to pay in australian dollars ($) canadian dollars ($) euros (€) pound sterling (£) new zealand dollar ($) us dollars ($) south african rand change currency, description.

We all look for different things when assessing an art research page. That is why this download includes two different, editable versions of an assessment rubric. A basic version and a comprehensive version.

The basic version includes a ‘what to include’ column, presentation of pictures, good quality research and creating a balance on the page.

The comprehensive version includes all of the above and also personal opinion and artistic response. Some of the descriptors are more comprehensive too.

This is one of many assessment rubrics on The Arty Teacher website.

The Arty Teacher

Sarah Crowther is The Arty Teacher. She is a high school art teacher in the North West of England. She strives to share her enthusiasm for art by providing art teachers around the globe with high-quality resources and by sharing her expertise through this blog.

You must log in and be a buyer of this download to submit a review.

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

More art lessons that you'll love...

Subscribe & save in any currency! I WANT TO PAY IN Australian Dollars ($) Canadian Dollars ($) Euros (€) Pound Sterling (£) New Zealand Dollar ($) US Dollars ($) South African rand Change Currency

Basic subscription free.

Register and you can download 3 of the Free Resources Every Month!

Premium Subscription $9.99 Per month $99 Per year

Save money and get 10 resources of your choice every month, and save even more with a yearly subscription.

School Subscription Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year Free Per year

For departments with 2 or more members. Subscribe for a total of 2 teachers to download 10 resources each month.

Sarah Crowther – The Arty Teacher

I set up The Arty Teacher because I have a passion for my subject that I want to share with other art teachers around the world.

I have been a high school art teacher for over 20 years, so I understand what it’s like to be in front of a class of students, often with very different abilities and attitudes.

I wanted to develop resources that would help teachers to bring out the best in every student in every class. I also wanted to free-up staff from time-consuming lesson preparation to let them focus instead on delivering exciting, motivating, dynamic lessons, supported by excellent resources.

Privacy Overview

Username or Email

Lost Password?

Artist Research - 6th Grade English: Artist Research Spring 2022-23

- Artist Research Spring 2022-23

- Spring 2021 Artist Research

- 2018-19 Research

Research Task

“If art is to nourish the roots of our culture, society must set the artist free to follow his vision wherever it takes him.” ~ John F. Kennedy

Essential Question: Why does art matter?

As a scholarly researcher, you will be exploring the world of art through the work on one artist of your choosing. You will explore the artist, their work, and and its influence or impact. You will need to cite evidence from published sources. You will gather notes in a graphic organizer (citing your sources). Then, you will create a "Zen PowerPoint" to share what you have learned with your peers.

Pro Tip! Choose an artist that interests you and is well-established with a recognized body of work. This will ensure that you enjoy reading about the artist and that you will have success locating credible, published information.

Citation Lesson Videos - Enrichment

Video 1 - Why Do We Cite

Encyclopedia Britannica Citation Video

Book Source Citation Worksheet Lesson

Gale Database Citation Lesson

Website Source Citation Lesson

This section includes PDFs of the handouts provided in class.

Library Research Lesson Handouts

- Day 1 Inquiry Handout

- Day 1.2 Annotation Guide

- Day 2.2 Dot Jot-Paraphase Notes Page

- Well-Known Work Notes and Questions

Enrichment Citation Lesson Handouts

- Citation Worksheet

- Encyclopedia Britannica Example Citation Worksheet

- Book Citation Worksheet Example

- Gale Database Citation Worksheet Example

- Website Example Citation Worksheet

Library Catalog

Google custom search engine.

If the library does not have a book on your artist, use the custom Google search box below to search for a credible website with information on your artist. The first 4 results will be ads, scroll beyond those results to find credible website results.

Zen PowerPoint

Example Presentation - Ansel Adams

Zen Design Lesson Video

- Zen Guided Notes Handout

- PowerPoint Planner

- PowerPoint Template

- Next: Spring 2021 Artist Research >>

- Last Updated: Mar 27, 2023 3:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.monroe.edu/artistresearch

- Username or Email

- CREATE AN ACCOUNT!

- FACEBOOK LOGIN

- Keep me logged in!

Your email*

By checking this box, you confirm that you agree to the terms & conditions & privacy policy of thesmartteacher.com., after you click submit, we’ll send an email to the address you’ve provided. the email will contain a link that will send you to the next steps.

BROWSE ALL

High [9th-12th] Unit Plan

Ceramic artist research project, created on march 07, 2013 by mrsimpey.

Students in Studio Art will research a famous ceramic artist and then create his or her own representation of that artist's work out of clay.

13 Keeps, 3 Likes, 0 Comments

Visual arts standard 1: understanding and applying media, techniques, and processes, visual arts standard 2: using knowledge of structures and functions, visual arts standard 3: choosing and evaluating a range of subject matter, symbols, and ideas, visual arts standard 5: reflecting upon and assessing the characteristics and merits of their work and the work of others.

famous artist project rubric

All Formats

Resource types, all resource types.

- Rating Count

- Price (Ascending)

- Price (Descending)

- Most Recent

Famous artist project rubric

FAMOUS ARTISTS Biography (ART - HISTORY) RESEARCH PROJECT + RUBRIC

Visual Artists Research Paper Project — Art History Secondary ELA — CCSS Rubric

- Easel Activity

Famous Artist Cards & Projects - Outlines, Worksheets, Rubrics , 100 Art Cards

Modern Black Artists Art Projects , Artist Study, Rubrics for Black History Month

Famous Artist Research Project

Famous Artist Research Project - Research Paper Assignment

Famous Artist Research Project ( Google Drive )

- Google Slides™

- Word Document File

Oscar Howe: Native American Style Art Project

Culture: Famous Spanish Artists Project (English Version)

- Google Docs™

- Internet Activities

Famous Artists Research Project - 12 People, Vocab Cards, Packet, Book + More!

Painting Project with Artist Research in Artist 's Style

PBL: Optical Illusions Neighborhood Project | Science | Impact | Rubrics

Fashion Design: Katy Perry-Inspired Project

Motown Research Paper Project — Secondary Music ELA — CCSS Rubric

Realidades 3 Chapter 2 - Artista Famoso Project Rubrics

Culture: Famous Spanish Artists Project (Spanish Version) | Artistas Famosas

Famous Hispanic musical artist Project

Andy Warhol Artist Study - Self Portrait - Slideshow, Project and Rubric

- Google Drive™ folder

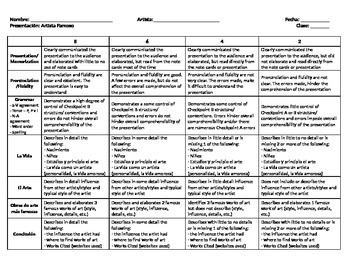

SPANISH Interview with an Artist Project & Research Graphic Organizer Bundle

Interview with a Famous Artist Project & Research Graphic Organizer Bundle

If Famous Artists Were Chefs Drawing Project

Spanish Art Creation Project

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

New Project: Utilizing Arts & Culture to Mitigate Construction Impacts

Can placemaking, temporary art, community or cultural events support quality of life and help offset the negative impacts of road construction?

MnDOT, with the University of Minnesota Humphrey School of Public Affairs, is conducting a research implementation project that will help answer that question while potentially offsetting the impacts of highway construction on downtown Lanesboro when Highway 250 is rebuilt.

Project goals

Primary goal : To test, document, and evaluate the premise that arts and culture can help overcome the disruption of highway construction and mitigate negative impacts on businesses, residents, and visitors.

Secondary goal : To identify and test potential partnerships and funding strategies to support place-making, temporary art, community, or cultural events to complement traditional mitigation strategies and tactics used to help offset the negative impacts of highway construction.

This project will not only help address construction impacts in Lanesboro, but also will inform improvements in the larger process of engaging community members impacted by highway construction and ensuring that the strategies conducted are relevant for the community.

Project tasks

- Identifying and documenting economic strengths in the community

- Identifying and documenting impacted stakeholders

- Developing and implementing a plan for mitigating economic and community construction impacts

- Documenting successful practices and identifying tools to assess the impacts after construction

- Sharing findings with local governments, transportation agencies and arts/cultural groups

“This research is looking into leveraging community assets as a new and innovative way to help mitigate the negative impacts of roadway construction. It will also inform improvements in the process of engaging community members and complement the existing mitigation guidance and tools currently available to MnDOT project managers,” said Jeanne Aamodt, technical liaison.

Project Details

- Estimated Start Date: 06/29/2023

- Estimated Completion Date: 06/30/2027

- Funding: MnDOT

- Principal Investigator: Frank Douma

- Co-Principal Investigators: Camila Fonseca-Sarmiento

- Technical Liaison: Jeanne Aamodt

Details of the research study work plan and timeline are subject to change.

To receive email updates about this project, visit MnDOT’s Office of Research & Innovation to subscribe .

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply, minnesota's transportation research blog.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Do more with rubrics than ever imagined possible. Only with iRubric tm . iRubric MX6X7AA: Rubric title Contemporary Artist Research Project. <!---. Rubric possible points is 1. --->Built by giannamorek using iRubric.com. Free rubric builder and assessment tools.

Artist Research Rubric . This project is worth 200 points of Total Semester Grade. 1. Paper (35%) ... typed, double spaced, with a font no larger than 12 pt. Rubric: The following is the information and other requirements for your paper. INCLUDE WORKS CITED PAGE! 1. Biographical info on your artist (dates, time period, family , residence ...

IMAGES (find a portrait or photograph and five works) Portrait or Photograph of artist (find one online or scanned from book) Artist or photographer: Date: Location of image: URL (or print material source): As you are doing your research SAVE FIVE (5) images of the artist's work to your disk (or folder on server).

Art teachers have always been ahead of the game with performance-based assessments by using portfolios. To make their judgment more consistent and fair, art teachers need to create rubrics for grading. To make a rubric, a teacher first needs to know exactly what constitutes "A" work. Rubrics can improve student work by letting students know ...

RubiStar is a tool to help the teacher who wants to use rubrics, but does not have the time to develop them from scratch. ... Create Rubrics for your Project-Based Learning Activities Rubric ID: 2340063. Find out how to make this rubric interactive Research Report : Artist Research. CATEGORY 4 3 2 1 Artist Description Student summarizes the ...